Abstract

Climate anxiety is emerging as a significant social problem, as highlighted by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)’s warnings about its adverse effects on mental health. While climate anxiety has been predominantly studied in Western contexts using quantitative methods, there is a paucity of research that employs qualitative approaches to explore this phenomenon in different sociocultural settings. This study aims to fill this contextual and methodological gap. This study explores the lived experiences of climate anxiety among young adults in South Korea, a country with limited systematic climate response measures, considering their unique sociocultural context. Utilizing the qualitative photovoice method, the research involved in-depth interviews with six young adult participants and two rounds of focus group discussions centered around 24 participant-generated photographs. The findings reveal that participants experienced climate anxiety not only through direct physical threats, such as natural disasters, but also through introspective realizations of their contributions to climate change amidst perceived societal indifference toward climate and environmental issues. Additionally, participants grappled with the tension between neoliberal lifestyles and environmental challenges. This study concludes that climate anxiety may be exacerbated in rapidly growing economies like South Korea, where neoliberal individualization undermines collective values. These findings suggest a need for interventions that address both the psychological and the unique structural pressures faced by young adults in this context. Educational initiatives should aim to go beyond mere information provision to foster critical consciousness about systemic drivers, such as neoliberalism, and cultivate skills for collective organizing and advocacy, thereby countering the depoliticizing effects of individualized responsibility.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In 2022, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) acknowledged the adverse impacts of the climate crisis on mental health (IPCC, 2022). Individual experiences of these psychological effects are influenced by perceptions of the environmental crisis. Reactions such as anxiety, sadness, loss, and anger are considered understandable responses to significant environmental problems, rather than pathological conditions (Pihkala, 2019). Albrecht (2011) conceptualizes the psychological reactions to environmental degradation and change as a form of existential syndrome, reflecting perceptions of environmental change rather than direct sensory experiences. Consequently, negative psychological reactions and mental health problems related to climate change can occur without direct exposure to climate-related damage and can manifest as various types of anxiety (Pihkala, 2019).

The emotional impact of climate change has been extensively studied. An international survey of 16–25-year-olds in 10 countries found that ~84% had moderate or high concerns about climate change, with over 50% reporting negative emotions such as anxiety and anger (Hickman et al., 2021). Climate or eco-anxiety is particularly prevalent among children, adolescents, and young adults (Boluda-Verdu et al., 2022; Coffey, 2021; Hickman et al., 2021). A 2020 survey in the UK indicated that younger individuals exhibited higher levels of climate anxiety, with age being the sole demographic factor influencing it (Whitmarsh, 2022). Similarly, a 2020 report from the American Psychological Association found that 48% of young adults aged 18-34 reported feeling stressed by climate change in their daily lives (APA, 2020).

While climate anxiety has been recognized as a mental health concern, most prior studies have been conducted in Western societies, particularly in Europe, North America, and Australia, and have predominantly employed quantitative research methodologies (Coffey et al., 2021; Ojala et al., 2021). This approach often neglects the significant influence of unique climate change experiences and sociocultural contexts on emotional responses.

In South Korea, the 2021 Public Survey on Awareness towards the Environment revealed that 88.3% of respondents rated the social impact of climate change as serious, yet only 54.5% perceived the personal impact as serious (Ahn et al., 2021). The younger generation in South Korea exhibits a passive attitude towards climate change action (Kwon et al., 2019; Oh and Yun, 2022). These findings suggest a high awareness of climate change risks among Koreans but a disconnect between this awareness and personal engagement in climate action. However, preliminary evidence on climate anxiety in South Korea shows that young people demonstrate higher prevalence rates of climate anxiety (Chae et al., 2024; Jang et al., 2023). There is a notable absence of explanations regarding why young Koreans develop climate anxiety within their specific sociocultural context and how this anxiety relates to their climate change awareness and behavioral responses. Additionally, there is insufficient analysis of the reported increase in climate anxiety among young people lately, which contrasts with observed passivity in responding to climate change. Therefore, this study aims to analyze the climate anxiety experienced by the young generation in South Korea, considering their unique sociocultural context and the specific challenges they face.

Studies on climate anxiety

Climate anxiety is a broader concept of environmental anxiety, intense emotions predominantly due to environmental problems and the threats they pose (Pihkala, 2019). While diverse psychological responses to climate change have been explored, a common underlying factor is a sense of worry. This concern is justified because climate change presents a real, and uncertain risk that is challenging to adapt to. Anxiety, as a more typical response to uncertainty than fear, becomes a prevalent reaction to climate change as a source of environmental stress (Clayton, 2020).

Further, climate anxiety should be perceived not merely as a straightforward emotional response but as a complex reaction involving the interplay between cognitive awareness that humans are causing the climate crisis and an emotional response to the perceived failure in addressing it (Hickman, 2020).

Age significantly influences the expression of climate anxiety (Crandon et al., 2022; Hickman et al., 2021; Whitmarsh et al., 2022), particularly among young people, who often harbor concerns about a bleak future, despair for humanity, dissatisfaction with government responses to climate change, and feelings of betrayal (Hickman et al., 2021). The experience of climate anxiety in youth is influenced by various ecological systems, including micro-, meso-, exo-, and macro-systems (Bronfenbrenner, 1979; Crandon et al., 2022). Societies play a pivotal role in shaping the concept of anxiety, which varies across cultures, necessitating a comprehensive analysis. As Steverson noted, “Anxiety is a fecund source for sociological analysis as it provokes general assumptions about social life (Steverson, 2022)”, underscoring the importance of sociocultural context in understanding climate anxiety among young individuals.

Considering the intertwining of emotions, culture, and the varying impacts of climate change across regions, the experience of climate anxiety may differ by location. For instance, while correlations between climate anxiety and demographic variables were identified, patterns varied across countries, indicating that the mechanisms of climate anxiety may differ based on a country’s experience with the climate crisis (Tam, 2023). However, it is noteworthy that few studies have explored non-Western countries or their sociocultural context.

Climate crisis awareness among Korean young generation

Koreans exhibit a relatively high level of awareness regarding the climate crisis. According to a 2023 Ipsos survey, 85% of respondents in Korea agreed with the statement, “We are heading for environmental disaster unless we change our habits quickly,” surpassing the global average of 80% (Ipsos, 2023). However, in the Climate Change Performance Index, an assessment of 63 countries’ climate responses, Korea consistently ranked a very low 60th position in both 2021 and 2022 (Germanwatch, 2022). While a gap exists between governmental climate crisis awareness and that of Koreans, a WIN survey conducted across 35 countries revealed that 59% of Koreans believe their government is taking the necessary steps, exceeding the global average of 39%. Furthermore, pessimism about the timing of climate change action decreased from 66% in 2019 to 39% in 2022 (WIN, 2021).

In essence, there is an optimistic outlook among Koreans regarding climate change and their government’s response. This optimism can be attributed to two main factors. Firstly, there is a high level of trust in science, leading Koreans to believe that science and technology can effectively address climate challenges (Bak and Huh, 2012). Secondly, despite their awareness of climate change, many Koreans perceive themselves as psychologically distant from the associated risks, resulting in more abstract rather than concrete actions (Kim et al., 2018).

Analyzing the younger generation from the early 1980s to the present, they are reported to be less willing to act on climate change than other generations (Lee and Kim, 2019). While the differences in climate change risk perception among generations may not be statistically significant, a noticeable trend of diminishing willingness to address climate change is observed with decreasing age (Oh and Yun, 2022).

A potential explanation for this generational gap is the significant socioeconomic challenges facing young people in Korea today, making them less inclined to take proactive measures (Lee and Kim, 2019). They tend to prioritize concerns such as job shortages over climate change, displaying the lowest agreement with sacrificing economic growth to tackle environmental issues (Oh and Yun, 2022). Consequently, while young adults are cognizant of climate change, they may not view it as an urgent matter but rather as a concern that does not take precedence in their priorities.

However, concerning climate anxiety, a national statistics survey revealed that the under-19 (41%) and 19–28 (43%) age groups reported an increase in individuals responding “very anxious” or “somewhat anxious” about climate change issues such as heat waves and floods in 2022 compared to 2020 (KOSIS, 2022). Additionally, individuals in their 20 s and 30 s exhibited higher average climate anxiety scores than other age groups (Chae et al., 2024), according to the Korean Climate Change Anxiety Scale (K-CCAS) (Jang et al., 2023). This highlights the potential for an academic gap on the causes of climate anxiety and its experiences among young people in Korea.

The question then arises is: how does the young generation in Korea experience climate anxiety? Currently, there is a dearth of explanations for climate anxiety among them. An exploration of their climate anxiety within the context of Korea’s sociocultural specificities may offer novel insights into emotional responses to climate change.

Methods

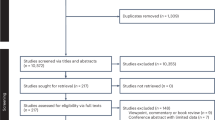

Research design

The purpose of this study is to have young Koreans in their 20s who experience climate anxiety due to the climate crisis participate in the study and reveal their experiences through photos, explore personal and community problems in detail with researchers, and strengthen their capacity to respond to climate anxiety, which leads to specific actions. To this end, the research team decided that the photovoice method, which captures problems perceived by research participants through photography, derives solutions to individual and community problems through group discussions, and conveys these to the public and policymakers, was appropriate for this study (Wang, 1999). Photovoice is a form of participatory action research methodology proposed by Wang and Burris (1997) to develop a program for women’s health in Yunnan Province, China. The process is based on feminist theory and community-based approaches, with a focus on educating participants’ critical consciousness. Photovoice helps participants to engage in direct discussion of community problems and identify ways to effectively communicate with policymakers (Wang, 2006). Participants also determine the research topic and express their experiences and perceptions through photography (Park and Kim, 2019).

Previous studies on photovoice about climate change have also used this method to actively engage residents (Bennett and Dearden, 2013), children (Herrick et al., 2022), and young adults (Grant and Case, 2022) to form a public discourse to help them have a voice in climate change. This study also chose the photovoice method so that those who lack a public space to express their climate anxiety can take the initiative to reveal their experiences in Korea.

Additionally, although the sample size of this study was extremely small (N = 6), photovoice analysis allowed for an in-depth case study analysis focusing on the narratives of each research participant.

Study area

This study was conducted throughout November and December 2022, in Seoul, South Korea. As the nation’s capital and largest urban center, Seoul represents a significant context for examining climate anxiety, given its high population density, rapid urbanization, and exposure to various environmental challenges, including air pollution, urban heat islands, and extreme weather events. The focus group interviews (FGI) were executed in the conference room of Yonsei University, a neutral and accessible location chosen to facilitate participation. Individual interviews were performed at locations and times convenient to the participants and dispersed throughout Seoul to ensure the participants’ comfort and convenience for in-depth personal interviews.

Sampling

This study began recruiting participants on November 15, 2022. Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of participants. Participants were young adults (n = 6) who had been concerned about the climate crisis for more than a year and had experienced climate anxiety due to thoughts about the climate crisis in the past month. In addition, participants were individuals capable of taking and articulating their experiences through photographs for the study. As an exploratory investigation of climate anxiety, specific diagnostic criteria for climate anxiety were not established. However, researchers defined climate anxiety as “the feelings of loss, helplessness, frustration, and anxiety brought on by the climate crisis” in the recruitment materials and inclusion criteria. During the recruitment process, researchers verified that participants met these inclusion criteria and demonstrated understanding of the climate anxiety concept. Three participants (C, D, and F) were recruited through purposive sampling from the researchers’ networks, while two participants (A and E) were recruited via social media promotion on X (formerly Twitter). The final participant (B) was recruited through snowball sampling as an acquaintance of participant A. The mean age of participants was 24 years (SD = 2.58).

Data collection and analysis

This study was conducted over six structured sessions. Meeting times were prearranged via messenger to accommodate the research teams and participants’ schedules. In the initial session, the research team introduced the photovoice methodology and facilitated a discussion of potential photographic themes via Zoom. Participants independently selected the topic for the first FGI, which addressed perceptions, lived experiences, and responses to climate anxiety. Based on participants’ perspectives regarding the role of community and systemic factors in shaping climate anxiety, the second FGI focused on climate anxiety at the community and institutional levels.

The second session involved preliminary individual interviews to elicit participants’ understandings of climate change, their everyday encounters with its effects, and the emotional and experiential consequences. During the third and fourth sessions, participants presented their photographs during FGIs and engaged in collective discussions. Each participant contributed two photographs per session, four images per individual, each accompanied by a title.

To support in-depth dialog and critical reflection, the SHOWeD method (Wang, 1999) was employed. This method involves five guiding questions: What do you See here? (S) What is really Happening here? (H) How does this relate to Our lives? (O) Why does this situation, concern, or strength exist? (e) What can we Do about it? (D). Wang (1999) posits that this structured approach enables participants to engage with their photographic narratives analytically and collectively explore potential responses to the identified issues.

In the fifth session, participants reviewed emerging findings from the FGIs and collaboratively developed action-oriented strategies. The final session was dedicated to creating a web-based exhibition showcasing participants’ photo narratives (https://forever1165.wixsite.com/climate-anxiety). In appreciation of their contribution, each participant received a 50,000 won (USD$37) gift card.

Data analysis was based on 24 photos taken by the participants, individual interviews, group discussion of findings, and transcribed texts from the FGIs. Interview data were analyzed using a three-step coding procedure referring to Emerson’s research methodology (Emerson et al., 2011). In the first stage, open coding was used to read each transcript and identify emerging themes. In the second stage, the codes derived from stage one were clustered to derive subthemes. In the third stage, the themes derived from stage two were analyzed and categorized at a larger level. The researchers held several rounds of discussions to ensure consistency of themes. Atlas.ti 22, a qualitative data analysis software, was used.

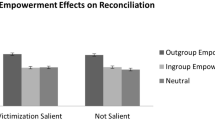

Results

Two main themes emerged from the photovoice study with six young South Korean adults concerning their experiences of climate anxiety: “threat perception” and “reflection and insights.” As anticipated, both direct and indirect impacts of climate change contributed to participants’ perceptions of threat, thereby shaping their climate anxiety. The theme of threat perception encompasses the perceived unsustainability of the future, an absence of community and care, and the characterization of the climate crisis by uncertainty and ignorance. The theme of reflection and insights is composed of personal introspection and voluntary self-negation, structural reflection and powerlessness, ongoing practices in daily life despite challenges, connections between life and systems, and calls for structural transformation. This theme illustrates participants’ interpretations of and reflections on these direct and indirect threats, as well as their attempts to cope with their climate anxiety. Overall, consistent with prior research, participants’ awareness of the lack of governmental and systemic responses to climate change provoked feelings of betrayal and frustration; however, their introspection also opened pathways towards potential social change and personal growth.

Threat perception

This theme details how participants perceive climate change as both a direct and indirect threat, which significantly contributes to their feelings of anxiety.

Direct and indirect experiences of climate impacts

Participants in the study reported having directly and indirectly experienced the impacts of the climate crisis, which manifested in observable weather changes and natural disasters affecting their daily lives. Figures 1 and 2 show how participants have encountered with climate-related events such as dense fog and heavy rainfall disrupted their daily routines, including activities like jogging, and instilled a sense of insecurity. The psychological impact of these physical climate events was vividly portrayed by Participant D, who described climate change evolving into climate anxiety through such experiences: “It’s late at night, and I’m alone in my room, and I feel like someone is knocking on my door, I don’t know who it is, (…) but it just keeps going and I feel like at some point they’re going to invade my space.” This narrative illustrates that direct sensory experiences of climate change are not mere inconveniences but are translated into profound feelings of vulnerability and personal threat, indicating that for these individuals, climate anxiety is an embodied and visceral experience. The feeling of an invasive presence suggests a breach of personal security, underscoring the psychological immediacy of climate change.

Unsustainability of the future and pessimism

In their lived experiences, participants noted an increase in both the frequency and severity of disasters. The prevailing sentiment among them was that climate change was not expected to improve but was instead perceived as deteriorating irreversibly. This fostered a “vague and pessimistic outlook on the sustainability of future generations and their futures.” The perception of an unalterably negative future trajectory can be a significant driver of anxiety. Such a loss of hope and control are key components of anxiety, as individuals anticipate future threats with a feeling of powerlessness to prevent them.

Feeling overwhelmed from lack of reliable information and societal indifference

Upon hearing news of damage caused by natural disasters, participants felt that the enormity of climate change was beyond their capacity to address. They expressed feelings of being overwhelmed by the lack of reliable information and concrete guidance on how to respond effectively. Furthermore, participants identified instances in their everyday lives that revealed what they perceived as society’s indifference to climate change. Participant A articulated this frustration, stating, “They keep telling us that we need a global response, that it’s a global problem, but nobody really knows what’s going on. Nobody’s giving me the right information, specific information.” Consequently, they invested significant effort and time in attempting to sift through inaccurate climate change-related information, which led to considerable fatigue.

To be specific, in Fig. 3, Participant E articulated a contradiction he felt upon encountering the phrase “using public transportation contributes to a 1.5 ∘C reduction in global temperature” at a train station. E commented, “I mean, 1.5 ∘C is a really powerful slogan, but it’s amusing how they phrase it as ‘1.5 ∘C reduction.’ If we lowered the temperature by 1.5 ∘C, we’d all be dead”. Participant E suggested the irony that such slogans may provide inaccurate information and ultimately lose their effectiveness in addressing climate change, reducing them to mere slogans. This critique highlights how poorly framed or inaccurate information can contribute to fatigue and cynicism, undermining genuine efforts. The combination of a perceived immense threat, a lack of actionable and trustworthy information, and societal apathy creates a significant cognitive and emotional dissonance for these individuals. This dissonance is likely a key mechanism exacerbating their climate anxiety, as they feel the urgency of the crisis but lack clear pathways for effective personal or collective response, leading to frustration and a sense of isolation in their concern. The societal indifference adds a layer of social invalidation to their anxieties.

Reflection and insights

This theme explores participants’ deeper reflections on the causes of climate change, their perceived role in it, societal structures, and their attempts to cope with the ensuing anxiety.

Insufficient governmental response and critique of urban lifestyles

While climate disasters persistently occur, participants believed that the government’s response is insufficient. Participant B stated, “It feels like the government is not doing anything.” Participant C’s remark also depicted a government that is hasty and focused only on erasing incidents at the time of a disaster, lacking interest in disaster prevention and the long-term impacts of disasters. She elaborated:

“It’s not just about ending with regrettable disasters. (…) It seems like there’s a need for a gradual process of fixing things, like sewing a torn garment bit by bit. But lately, it feels like the government is minimizing and looking at that process as if it’s nothing. That’s why I feel quite upset.” (Participant C)

Their criticism, however, did not end with governmental inaction. The fast-paced and environmentally unfriendly lifestyles prevalent in the city were also identified as sources of climate anxiety. Figures 4 and 5 depict Participants D and F expressing a sense of disconnection from nature and the loss of community attachment due to the homogenized appearance of the city. They described the difficulty of feeling alive in an urban space dominated by uniform apartments and buildings, which they perceived as lacking unique features and feeling excessively “organized” and “composed.” This critique extends beyond mere policy failure to a fundamental questioning of dominant urban lifestyles and development models, suggesting an awareness of systemic issues rather than just isolated incidents of mismanagement. This indicates a sophisticated level of structural critique, where the problem is seen not just in specific government actions but in the broader societal and environmental context they inhabit.

Photograph taken by a participant, showing a cityscape densely packed with buildings, where the horizon is entirely obscured. This figure is not covered by the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Reproduced with permission of participant D; copyright © participant D, all rights reserved.

Neoliberal pressures, loss of autonomy, and disconnection

In Fig. 6, Participant F portrayed a life devoid of autonomy, where aspirations for communal living outside Seoul are overshadowed by the relentless pursuit of capitalistic values within the city. The bleak urban landscape of South Korea, which emerged during a period of rapid development, left participants feeling disconnected from nature and deprived of a sense of belonging to a local community. Following industrialization, the mass construction of apartment complexes led to the homogenization of urban landscapes, eroding local emotional ties and homogenizing the lives of their residents.

Photograph taken by a participant, showing the road to Seoul as seen from a bus window, capturing the sense of transition and movement. This figure is not covered by the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Reproduced with permission of participant F; copyright © participant F, all rights reserved.

Participant A expressed difficulty in forming communities to address the climate crisis. She engaged in self-blame, asking, “Why can’t I engage more actively (in those alternative communities)?” The younger generation, born after widespread urbanization, has seldom experienced environmentally friendly communities throughout their lives. Moreover, young adults frequently leave their hometowns for educational and economic opportunities, resulting in a disconnection between their living spaces and social activities. Consequently, they often lack a stable base to settle and a community to which they feel connected. Participant F articulated this struggle:

“Do I always end up heading there (Seoul), towards a life centered around urban living? Even though (life like this) might not allow us to live a life that mitigates climate crisis?” (Participant F)

“Because there are so many cases of people in their 20 s and 30 s who don’t have a community, they’re usually wandering around, so how is community possible for people like that? I’ve been thinking about this for a long time, and it’s still very difficult.” (Participant F)

Climate anxiety for these young adults appears to be profoundly entangled with the precariousness and individualism fostered by the neoliberal socio-economic system. The societal emphasis on individual competition and success, often at the expense of collective well-being, creates a deep internal and societal tension. The struggle for personal security and career development in a competitive environment directly conflicts with the need for collective, long-term environmental action, and this fundamental conflict manifests as anxiety.

Desire for community and the role of supportive networks

Unable to share their feelings of anxiety and threat adequately, participants expressed a desire for a community where they could discuss the climate crisis and address their climate anxiety. The importance of having a supportive community was evident in participants’ remarks. Some participants frequently mentioned peaceful moments spent with vegetarian friends or engaging in sustainable practices. Those with established community resources were not always pessimistic about the climate crisis. For instance, Participant E, involved in the Korean Green Party, and Participant C, part of a network of vegans, expressed hope for the future. They differed from other participants due to the reliable and supportive networks they possessed. These experiences illustrate how participants could alleviate some of their climate anxiety by sharing empathy with others, highlighting the need for supportive communities. This suggests that individual resilience is deeply intertwined with social connectedness and shared values, and that climate anxiety is not solely an individual psychological phenomenon but is mediated by the social context and the availability of collective spaces for empathy and action.

Ontological security, self-blame, and lifestyle changes

For participants, urban life often represents a production-oriented and unsustainable lifestyle. They experienced climate anxiety upon realizing that humans are primary contributors to climate change, which prompted them to reflect on their environmental impact and question their very existence. For Participant D, experiencing climate anxiety was a matter of ontological security, striking at the core of her being and making her feel that every aspect of her life had been wrong. She stated:

“My very existence, the fact that I breathe, engaging in organic living as a living being - all of these actions incur costs, result in consumption, produce waste, lead to pollution. This very idea makes me think that my existence is truly malevolent. So, I’m constantly censoring myself, thinking that, just by living, it could be harmful.” (Participant D)

This “ontological insecurity” represents a profound crisis of being, where one’s existence is perceived as inherently harmful. Recognizing their role in the climate crisis led participants to take action to reduce their impact. They adopted practices like veganism and zero-waste in their daily lives, and some became involved in environmental activism. Their behavior was also consistent with their self-censorship. Participants’ environmental self-discipline is depicted in Figs. 7 and 8. Participant A questioned whether her use of a powerful computer and her background as a graduate student studying chemistry would increase the likelihood of resource depletion. She considered her lifestyle and asked herself, “How many resources are being used by the places I spend time in on a daily basis?” Participant C also expressed regret for having taken a taxi in a rush rather than trying to “manage” her efforts to walk a small distance to avoid carbon emissions from transportation. The adoption of rigorous self-discipline can be seen as an attempt to regain a sense of moral integrity and control in the face of overwhelming systemic problems. However, this intense individual focus, while empowering to some extent, can also become a source of further anxiety if perceived as insufficient, reflecting the neoliberal tendency to frame systemic problems as requiring individual solutions.

Photograph taken by a participant, showing a high-powered computing system that consumes substantial energy to operate complex software. This figure is not covered by the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Reproduced with permission of participant A; copyright © participant A, all rights reserved.

Photograph taken by a participant, showing a hurried moment of catching a taxi due to lateness, inviting reflection on daily routines and time use. This figure is not covered by the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Reproduced with permission of participant C; copyright © participant C, all rights reserved.

Social Friction and Apathy from Others

Although these behaviors and reflections are self-conducted, relationships with others also have an influence. For example, participants encountered people who labeled their actions as “eccentric” or responded with hostility. Some heard dismissive comments like “Being vegan is just a preference. Don’t claim you’re protecting the environment.” Participant B remarked, “I don’t bring up discussions about the climate crisis with those who seem unlikely to empathize.” She noted that some consider climate change fake news or a non-issue, which dampened her spirit of climate justice.

Participants believed that society did not embrace the idea of the common good in the face of climate disaster. “In Korea, the term ‘Generation MZ’ is often linked to consumerism. However, I’ve heard that in the US, it represents a new generation of socially conscious individuals,” said participant E. He compared Korea’s climate change apathy to that of other nations and expressed dismay at the absence of coordinated action. The participants, who opposed mainstream neoliberal mentalities, felt like outliers due to the indifference of Korean youth. This social invalidation can significantly compound climate anxiety, undermining their efforts, isolating them, and reinforcing feelings of being an outlier, potentially leading to disengagement or increased distress.

Conflict with Ingrained Neoliberal Values and Commodification of Alternatives

“I’m human too,” said participant A, “Like all of us, I was born and raised in the capitalist era, living this way. A lot of people in their 20 s and 30 s nowadays believe that they should receive as much as they give.” They grew up believing that pursuing neoliberal capitalist lifestyles was the goal, and such values were deeply ingrained in their lives. An additional cause of climate anxiety was the obligation to adopt lives they had never envisioned or embodied. Participant F voiced this conflict:

“Is this… not possible? Should I not have lived like this? Should I have more actively… made choices to survive well within this system, regardless of the overall structure?” (Participant F).

Reflecting on his pursuit of an alternative life, Participant F confessed that he sometimes thought he should have just pursued a standardized life like everyone else. By taking an interest in and speaking out about the climate crisis rather than engaging in productive practices to achieve personal gain, participants came to see themselves as nonconformists who resist normative neoliberal mentalities. Despite their desire to resist the system exacerbating the climate crisis, they struggled to escape it.

This struggle went along with keen criticism towards a structure that renders capital accumulation and commodification as the standard way of life. They noted that trends like veganism and zero waste, while intended as alternative practices to address climate change and environmental crises, often become forms of greenwashing in South Korea, losing their original meaning. Participants felt a sense of helplessness as they observed the commodification of these alternative practices, realizing their existence was deeply enmeshed within the capitalist structure. Participant E observed:

“There’s actually a lot of vegan products coming out from big companies lately. (…) I think there’s always a worry that people will just end up with a sense of efficacy that they’ve participated by consuming it, even though it doesn’t really… it doesn’t really mean anything. It’s like, “Oh, I’m eco-friendly, I’m eco-certified, I’ve contributed,” and then they stop.” (Participant E)

The participants internalize environmental norms and engage in self-regulation, yet they simultaneously recognize that these individual actions are often co-opted and commodified by the very capitalist system they critique. This creates a cycle of frustration and powerlessness, where attempts to enact change at an individual level are reabsorbed by the system, potentially intensifying anxiety rather than alleviating it. Their awareness of this co-optation is a critical element of their experience.

Tension between individual agency and structural powerlessness

Participants in the study tried to transform their lifestyles to be eco-friendlier and more self-regulating, while perceiving themselves as perpetrators and contributors to the climate crisis. However, they did not merely reflect on this self-regulation; they also experienced tensions that heightened their climate anxiety. While they had the capacity to make their lifestyles more sustainable—an aspect of self-regulation—they also recognized the structures governing their lives and their own powerlessness against them. This power imbalance impedes macro-level actions and drives individuals toward micro-level practices, which are primarily focused on consumerism and self-regulation and thus burden them further. In this sense, the norms and values they adhere to remain rooted in neoliberal capitalism. They reflected on this dynamic, seeking to disrupt a system which ironically perpetuates the same systemic issues they aim to challenge. Participant D noted:

“I actually think that in a way, this climate crisis awareness, consciousness, and action is also an eliteness, so that I should be given a certain space in life to recognize this. (…) Is it possible to talk to them (people with vulnerabilities) about veganism or zero waste or things like that, in their lives, because, you know, anything that they can consume within their wage is, you know, pricewise, you know, low-cost anyway.” (Participant D)

Participant C added:

“It’s possible that there’s anxiety about the future of the climate crisis, but the anxiety from the present reality seems much more overwhelming, and I think that might be what’s intensifying the climate anxiety. Personally, my greatest source of anxiety is that if the current capitalist system continues, it will inevitably lead to the progression of the climate crisis. The (progression) slope will become even steeper. So, how do we deal with this capitalism? The anxiety and helplessness stemming from that issue feel enormous.” (Participant C)

And Participant F expressed:

“I think the kind of anxiety that I have is that I think a lot of times it’s just a race to survive. The doors are going to get narrower, so whether it’s rising water levels or rising temperatures, I think that people who are going to die are going to die, and only people who can fend for themselves are going to survive.” (Participant F)

These observations demonstrate that participants encountered a strong association between neoliberalism and the pressure for self-improvement, prompting them to question the power structure. Their anxiety is thus not just about climate impacts, but about the perceived injustice and power imbalances inherent in the current system’s response, or lack thereof. This awareness of structural constraints, coupled with the pressure to act individually, is a potent source of anxiety and frustration.

Cynicism, hope, and relationality as coping mechanisms

Participants were often generous towards individuals because they understood the tension between the individual and the structure. Participant B, who criticized the high prices of eco-friendly and vegan products, employed a paradoxical strategy by addressing greenwashing while actively leveraging the norms of capitalism :

“I tend to turn it into a fashion. It’s a trend, you know. (…) When someone doesn’t follow it, you make them follow it unconsciously. You tell people, “Wow, this is the trend. It’s amazing, right?” and so on. Over time, and as you continue, people in South Korea, being sensitive to trends, will follow.” (Participant B)

Ironically, the overall somber tone of the FGI took a cynically humorous turn with B’s statement. Participant E concurred by saying, “This seems really good idea,” to which B responded, “Wow, you’re quite the strategist.” Participant D also agreed, stating, “I believe that one advantage of the environmental movement is that it establishes a rather low baseline where humanity can, to some extent, share a sense of crisis and reach consensus.” This moment captured how individuals sharing similar anxieties could still harbor slight hope despite their disappointment with their immediate surroundings and the broader world. Participants did not deny that the so-called “trends” have beneficial aspects, such as raising awareness of climate change and increasing the consumption of green products. Maintaining a critical attitude and cynicism towards phenomena while also practicing tolerance was seen as a defense mechanism to alleviate climate anxiety. Moreover, actively engaging stakeholders through trends was considered a valid strategy for climate adaptation, aligning with their desire to build alternative communities for support. In other words, the relational orientation observed among participants was a crucial factor for those grappling with climate anxiety. It served as a strategy to understand others not only as individuals embodying major social norms but also as individuals struggling under a structure that can change, potentially as collaborators.

Forced to navigate survival alone in the era of neoliberalism, participants deeply concerned about the climate crisis were frustrated by public indifference. The recurring failure to manage “the self” within a rigid neoliberal power structure, which participants believed contributed to the climate crisis, further intensified their climate anxiety. The entrenched social norms of neoliberal capitalism posed a significant challenge to be overcome, leading participants to place their hope in empathic relationality that continues to motivate them.

In Fig. 9, Participant D shared a photograph of an unexpected sign discovered in a flower bed while walking, which read, “Wait, the fruit is pretty. Love you.” She reflected:

Photograph taken by a participant, showing a quirky street-side sign that reads “Wait, the fruit is pretty. Love you.” prompting reflection on unexpected moments in the everyday environment. This figure is not covered by the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Reproduced with permission of participant D; copyright © participant D, all rights reserved.

“When I saw (the sign), I suddenly felt immense joy. It was heartening and I thought, the fruit is pretty, but would someone love me too? Though I don’t know who put it there… It may seem like an insignificant message on a trivial sign, but when it appeared unexpectedly in my daily life, it brought genuine happiness. Somehow, I wish that someday… in various corners of the world I inhabit, my writings or, for instance, if I were to make a film, could have that same power to catch passersby and make them notice something. From my perspective, this constitutes a movement for systemic change; such minor elements allow us to share so much. And perhaps these small things could even progress toward transforming the larger system.” (Participant D)

The group erupted in pleasant laughter at the appearance of this unexpected sign. Participant F, who had been contemplating the photograph, remarked:

“What we choose to see seems very important. How we receive and process external stimuli matters significantly. Climate change is one type of stimulus, but there are other stimuli we encounter daily. I was thinking about how we might reconfigure these experiences.” (Participant F)

In the face of overwhelming structural issues and internalized anxieties, participants develop sophisticated coping mechanisms that blend cynicism with strategic action and a deep yearning for relational connection. The “cynical humor” around leveraging capitalist norms (like fashion trends) for environmental ends is not just resignation, but a pragmatic, albeit somewhat disillusioned, attempt to find agency. The profound impact of a small, unexpected message of love in Fig. 9 underscores the critical role of hope, empathy, and human connection as powerful antidotes to despair. This suggests that even micro-level positive relational experiences can fuel a belief in the possibility of larger systemic change, pointing to a resilience rooted in shared humanity rather than individual stoicism. Coping, for these participants, is not just about individual sustainable practices but also about finding shared meaning, hope, and strategic ways to navigate a flawed system, often through humor, pragmatism, and an emphasis on human connection.

Climate anxiety is a systemic issue. Nevertheless, participants believed in the power of solidarity and empathy. They understood the moments of joy and happiness in everyday life. The FGI concluded with participants collectively considering difficult but potential answers to how daily life might be restructured with small connections and care, and how we might process the negative stimuli we face.

The findings from this photovoice study reveal that climate anxiety among young South Koreans is characterized by perceptions of threat stemming from experienced environmental changes and a pessimistic view of the future. Furthermore, it involves complex reflections on personal responsibility within the context of societal indifference, perceived governmental inaction, and the pervasive influence of neoliberal capitalism. These reflections lead to a range of emotional and behavioral responses, including self-blame, ontological insecurity, adoption of individual sustainable practices, and a profound desire for community and systemic change, alongside sophisticated coping mechanisms blending cynicism with hope rooted in relationality.

Discussion

This study aimed to explore the climate anxiety experienced by the young generation in South Korea, utilizing the photovoice method to understand their experiences within their unique sociocultural context. The findings indicate that participants experience climate anxiety not only through direct physical threats, such as natural disasters, but also through introspective realizations of their contributions to climate change amidst a perceived societal indifference and the tension between neoliberal lifestyles and environmental challenges. The emergence of climate anxiety in South Korea, as revealed by this research, is deeply rooted in the country’s sociocultural context, particularly concerning the government’s inadequate response and the pervasive influence of neoliberal individualization. This discussion will interpret these findings, connect them to existing literature, and consider their implications.

Interpretation of climate anxiety in the South Korean sociocultural context

Government inadequacy and neoliberal individualization

A key finding is the participants’ expressed frustration with the perceived inadequacy of the government’s response to the climate crisis and the apparent indifference of society at large. This frustration was often compounded by their acknowledgment of their own pursuit of individual lives without sufficient reflection on the environmental consequences, frequently leading to self-blame. This self-blame is intertwined with a perception of the climate crisis as a significant societal issue, exacerbated by the lack of communal support and the dominance of neoliberal lifestyles that prioritize individual achievement and consumption.

The participants’ descriptions of the “bleak urban landscape” and the “homogenization of urban landscapes, eroding local emotional ties” find resonance in the work of Moon (2018), who discusses how the mass construction of apartment complexes during South Korea’s rapid development led to such homogenization and the erosion of local community ties. This erosion of local emotional ties and community, as experienced by participants and documented by Moon (2018), removes a crucial buffer against anxiety. In a society that increasingly prioritizes individual achievement—a hallmark of neoliberalism—the lack of communal spaces for processing shared anxieties, such as those related to climate change, can intensify individual distress and the tendency towards self-blame. The urban development model, aligned with or driven by neoliberal values, thus contributes to a social environment where individuals may feel more isolated and consequently more vulnerable to anxieties like climate anxiety, with fewer communal resources available for coping.

Internalization of emotions and self-blame

In contrast to feelings of anger, resentment (Elliott, 2022), or a sense of betrayal towards the older generation (Hickman et al., 2021) observed in other, often Western, contexts, participants in this study tended to internalize their emotions. This internalization led to self-exploration rather than outward-directed negative emotions. The absence of a strong sense of community and perceived lack of political support appeared to intensify this inward focus.

This pattern of internalization and self-blame, potentially influenced by cultural norms in South Korea that may emphasize collective harmony and indirect forms of expression, could represent a culturally specific manifestation of climate anxiety. Furthermore, it might also reflect the pervasive influence of neoliberal individualization, which tends to frame responsibility for systemic problems at the personal level. This focus on individual culpability can divert energy from collective political action towards individual moral accounting, thereby potentially perpetuating the very societal status quo that fuels the anxiety. The combination of cultural tendencies and neoliberal ideology may create a powerful dynamic that stifles collective dissent and channels distress inward.

Neoliberal environmentalism, subjectification, and “Environmentality”

The “Production of the Self” and inner transition

Our study offers a distinctive contribution by demonstrating the link between those who experience climate anxiety and an apathetic society that tends to depoliticize climate issues. Through what can be termed neoliberal environmentalism, the climate problem indeed contributes to the “production of the self” (Carvalho and Ferreira, 2024). Certain personal technologies and lifestyle modifications are working to reshape citizens in a way that is more environmentally conscious and sensitive to climatic problems. This process of subjectification is associated with a sort of “inner transition” (Carvalho and Ferreira, 2024), much like our participants’ fixation on their own sustainable behaviors. The “technologies of the self,” as discussed by Foucault (1988), are pertinent here; participants’ self-monitoring, self-censorship, and adoption of practices such as veganism can be understood as such technologies, through which individuals actively work on themselves to align with certain environmental and moral norms.

While this “inner transition” and the adoption of sustainable behaviors can be empowering on an individual level, within a neoliberal framework, it risks becoming another form of self-optimization and consumer choice rather than a fundamental challenge to the underlying system. The “self” that is produced might be an “eco-conscious consumer” who expresses environmentalism primarily through purchasing “green” products—a behavior critiqued by Participant E —rather than a “political agent of systemic change.” This mode of engagement can fit neatly within, and even reinforce, the neoliberal order.

Depoliticization, individual responsibility, and “Environmentality”

Although prior research on the individualization that results from neoliberal power and its connection to climate adaptation has highlighted how this power can lead to the depoliticization of climate issues and individual responsibilities following the disintegration of social cohesion (Carvalho and Ferreira 2024; Fieldman, 2011), it has not extensively addressed how people perceive and engage with this subjectification. The concept of “environmentality,” as described by Fletcher (2017) and Agrawal (2005), explains how various processes shape and modify thoughts and behaviors, particularly concerning environmental politics, leading individuals to become “environmental subjects” who internalize particular norms and values, accompanied by self-regulating skills. This study’s participants can be seen as embodying this “environmentality.”

Participants attempted to leave their comfort zones and engage with the social landscape. They encountered conflicts between the individual and the social system, shaping them into representatives of “environmentality.” They criticized the state’s inaction, highlighting how environmental and climate issues are being co-opted by capitalist interests. As a result, individuals sought alternative practices and communities to foster collective cohesion. Importantly, the participants are not passive subjects of this environmentality. Their critical awareness of how environmental issues are “co-opted by capitalist interests” and their attempts to find “alternative practices and communities” represent a form of resistance, or at least a deep unease, with the disciplinary aspects of neoliberal environmentality. Their climate anxiety, initially focused inward, shows the potential to expand outward positively as they understand the importance of social cohesion. This suggests that the very tensions created by neoliberal environmentality—the contradiction between internalized norms and observed systemic failures or co-optation—can, paradoxically, fuel a desire for more authentic, collective forms of engagement, potentially moving beyond the depoliticized “inner transition.”

The role of neoliberalism in shaping youth experiences in South Korea

The discussion of neoliberalism’s impact is significantly informed by literature detailing its effects on South Korean youth. Song et al. (2009) described how, in the aftermath of the 1997 Asian financial crisis, youth were recognized as a key labor force poised to drive future industries, prioritizing technological development and the formation of an entrepreneurial self within a system of global capitalism. Lee (2015) further elaborated on this, discussing the emergence of a new labor underclass and the significant barriers young job seekers face in achieving economic and social security in neoliberal Korea. This precarity has intensified the concentration of youth into Seoul, as noted by Kim (2020), in their quest for ‘self-determination of life’ to enhance their security. Concurrently, as Han (2012) pointed out, families are increasingly forced into consumption-oriented roles, and local communities are disintegrating, losing their traditional functions under this neoliberal capitalist system where individuals are compelled to focus on career development based on standardized criteria to maintain market competitiveness.

These authors collectively depict a highly competitive, insecure, and individualized environment for South Korean youth. This socio-economic context is crucial for understanding why climate anxiety might manifest as observed in this study. The immense pressure to succeed individually in a precarious job market, often necessitating migration to Seoul and participation in a consumerist society, leaves little room or energy for collective environmental action. This can exacerbate feelings of powerlessness against large-scale problems like climate change, rooting the specific form of climate anxiety (internalized, tied to individual lifestyle choices, and frustrated by a lack of collective options) deeply within the documented socio-economic reality of these young adults.

Broader implications and comparative perspectives

Ogunbode et al. (2022) highlighted that in countries where climate anxiety translates into environmental activism, these nations are typically democratic and relatively affluent, mostly within Europe. While South Korea is a democratic and developed nation with a high level of awareness about climate change, the political and public responses have been insufficient. As previous studies on climate anxiety in South Korea noted, though overall agreement that climate change is happening is high, this knowledge might not lead to broader collective action or alternative practices.

In rapidly growing economies like South Korea, where neoliberal individualization is deeply embedded in societal norms, individuals who are acutely aware of climate change might experience a unique form of climate anxiety. This anxiety is not only a reflection of environmental concerns but also a symptom of broader sociocultural dynamics. The “unique form of climate anxiety” in such contexts may be characterized by a particularly sharp conflict between high awareness and concern on one hand, and low perceived collective efficacy or political will for change on the other, a conflict exacerbated by intense individual pressures. This differs from contexts where pathways to activism are more established or culturally resonant. The individualizing pressures of neoliberalism in South Korea may channel anxiety primarily into personal lifestyle changes and self-blame rather than collective activism, creating a distinct manifestation of climate anxiety.

Strengths and limitations of the study

Despite the limitations, the use of the photovoice method as a form of participatory action research proved valuable. Participants reported feeling comfortable sharing their experiences and felt empowered throughout the study. During the time allocated for sharing final impressions, participants offered feedback such as, “This was my first experience conversing with individuals from such diverse life positions, which provided fresh stimulus,” and “It was personally a growth opportunity to engage in discussions with these excellent people from various perspectives”. Notably, one participant decided to initiate a climate crisis club at his school and planned to use the photovoice method as a program to discuss climate anxiety, indicating the potential for this approach to foster community engagement and activism. The ethical management of the photovoice process, including participant control over images and narratives, and the institutional review board approval, were crucial in facilitating this positive experience, particularly given the sensitive nature of anxiety.

However, this study concentrated on young adults who are students residing in metropolitan areas. It is important to recognize that young adults in non-metropolitan areas may experience climate anxiety differently due to the societal divide between urban and rural regions in South Korea. Furthermore, the small sample size of six participants limits the generalizability of the findings. We also note that the photovoice method, while empowering, may have introduced a degree of selection bias toward participants who are already more reflective or environmentally conscious.

Recommendations for future research and interventions

Future research should include a larger and more diverse sample to provide a more comprehensive depiction of climate anxiety across different demographics in Korea. Specifically, research could investigate the mechanisms by which neoliberal ideology translates into internalized climate anxiety and potentially inhibits collective action within the South Korean context.

Overall, this study underscores the need for targeted interventions that address the specific sociocultural factors contributing to climate anxiety in South Korea. Enhanced political commitment, greater community support, and educational initiatives that foster collective action could mitigate the psychological burden of climate anxiety among young adults. Interventions could focus on creating and supporting “third spaces” or communities of practice—as desired by the participants—that are somewhat insulated from overwhelming market logics, allowing for genuine dialog, emotional processing, and the co-creation of collective responses to climate change. Educational initiatives should aim to go beyond mere information provision to foster critical consciousness about systemic drivers, such as neoliberalism, and cultivate skills for collective organizing and advocacy, thereby countering the depoliticizing effects of individualized responsibility. Future research should continue to explore these dimensions, aiming to develop strategies that resonate with the unique sociocultural landscape of South Korea.

Conclusions

This study utilized the photovoice method to discuss the climate anxiety of Korean young generations. Series of in person interviews and FGI with pictures taken by participants have deepened an understanding of participants’ climate anxiety.

In this study, Korean young adults with climate anxiety tended to experience heightened anxiety when directly confronted with climate disasters and perceived public and state apathy towards climate crises. A significant finding of our study is that recognizing human contributions to the climate crisis exacerbates climate anxiety. This is intensified by introspection on their lifestyle choices and feelings of helplessness in the face of a rigid and indifferent society. Participants identified the neoliberal capitalist lifestyle, which compels them to seek success as entrepreneurs and valid consumers, as implicating them in environmental harm. However, there is insufficient social security to address or adapt to climate change, and it is often framed as an individual issue affecting only sensitive individuals. Consequently, participants have lost the power to raise collective voices and have instead turned to individual practices, worsening their anxiety. Our study highlights the importance of the structural factors that produce climate anxiety, a specific form of anxiety already presents in society but heightened by the climate crisis. The sociocultural context in Korean society, characterized by highly individualized young people embodying neoliberal mentalities, offers valuable insights for mental health professionals and social workers in addressing climate anxiety through understanding the individual’s sociocultural context and advocacy.

However, experiencing climate anxiety does not necessarily culminate in frustration. As this study revealed, engaging in deep conversations and fostering empathy about the climate crisis with others enabled participants to recognize the systemic factors underlying climate change and environmental degradation. This process not only mitigated their climate anxiety but also enhanced their capacity to envision collective care and alternative practices in response to the crisis.

Therefore, it is crucial to address climate anxiety by understanding the client’s unique sociocultural context, particularly the pressures of neoliberal individualism that can intensify feelings of isolation and self-blame. Interventions should therefore go beyond individual coping mechanisms to include advocacy and support for community-based connection. Based on this understanding, civic organizations can provide spaces for communities to collectively envision their local environmental future and climate change responses, regardless of their initial level of concern about climate change. When community-specific voices emerge through bottom-up processes, policymakers will be better positioned to develop more appropriate climate mitigation plans that bridge structural social problems with contextual community needs. Policymakers should recognize the organic interconnection between climate-environmental issues and social systems and be equipped to articulate these logical connections rather than framing climate change as an issue for “sensitive individuals.”

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the Dataverse repository, https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/D48JPL.

References

Agrawal A (2005) Environmentality: community, intimate government, and the making of environmental subjects in Kumaon, India. Curr Anthropol 46(2):161–190. https://doi.org/10.1086/427122

Ahn SE, Yum JY, Lee HL (2021) Integrated Assessment to Environmental Valuation via Impact Pathway Analysis: Public Attitudes towards the Environment: 2021 Survey. Korea Environment Institute

Albrecht G (2011) Chronic environmental change: emerging ‘psychoterratic’ syndromes. In: Weissbecker, I (eds) Climate change and human well-being. International and Cultural Psychology. Springer, New York, p 43–56. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-9742-5_3

APA (2020) Majority of US adults believe climate change is most important issue today. APA Website. https://www.apa.org/news/press/releases/2020/02/climate-change. Last accessed April 2024

Bak HJ, Huh JY (2012) Who are the skeptics of climate change?: The effects of information seeking, confidence in science, and political orientations on public perceptions of climate change. ECO 16(1):71–100

Bennett NJ, Dearden P (2013) A picture of change: using photovoice to explore social and environmental change in coastal communities on the Andaman Coast of Thailand. Local Environ 18(9):983–1001. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2012.748733

Boluda-Verdu I, Senent-Valero M, Casas-Escolano M et al (2022) Fear for the future: Eco-anxiety and health implications, a systematic review. J Environ Psychol 84: 101904. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2022.101904

Bronfenbrenner U (1979) The ecology of human development: experiments by nature and design. Harvard University Press. Cambridge

Carvalho A, Ferreira V (2024) Climate crisis, neoliberal environmentalism and the self: the case of ‘inner transition. Soc Mov Stud 23(1):1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/14742837.2022.2070740

Chae SM, Lee SB, Kim HY (2024) Characteristics of climate anxiety in South Korea. Health Soc Welf Rev 44(1):245–267. https://doi.org/10.15709/HSWR.2024.44.1.245

Clayton S (2020) Climate anxiety: Psychological responses to climate change. J Anxiety Disord 74: 102263. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2020.102263

Climate Change 2022: Impacts. Adaptation and vulnerability (2022) IPCC. https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg2/ Accessed 21 Apr 2024

Climate Change Performance Index (CCPI) 2023 Germanwatch. https://www.germanwatch.org/en/87632 (2022) Accessed 21 Apr 2024

Coffey Y, Bhullar N, Durkin J et al (2021) Understanding eco-anxiety: A systematic scoping review of current literature and identified knowledge gaps. J Clim Change Health 3: 100047. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joclim.2021.100047

Crandon TJ, Scott JG, Charlson FJ et al (2022) A social–ecological perspective on climate anxiety in children and adolescents. Nat Clim Change 12(2):123–131. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-021-01251-y

Elliott R (2022) The ‘Boomer remover’: Intergenerational discounting, the coronavirus and climate change. Sociol Rev 70(1):74–91. https://doi.org/10.1177/00380261211049023

Emerson RM, Fretz RI, Shaw LL (2011) Writing ethnographic fieldnotes. University of Chicago Press

Fieldman G (2011) Neoliberalism, the production of vulnerability and the hobbled state: systemic barriers to climate adaptation. Clim Dev 3(2):159–174. https://doi.org/10.1080/17565529.2011.582278

Fletcher R (2017) Environmentality unbound: Multiple governmentalities in environmental politics. Geoforum 85:311–315. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2017.06.009

Foucault M (1988) Technologies of the self: a seminar with Michel Foucault. University of Massachusetts Press

Grant B, Case R (2022) Picture this: investigating mental health impacts of climate change on youth using a photovoice intervention. Educção, Soc Cult 62:1–22. https://doi.org/10.24840/esc.vi62.264

Han DW (2012) Welfare state and civil society: beyond the institution dependence. Korean J Soc Welf Res 30(0):57–77

Herrick IR, Lawson MA, Matewos AM (2022) Through the eyes of a child: exploring and engaging elementary students’ climate conceptions through photovoice. Educ Dev Psychol 39(1):100–115. https://doi.org/10.1080/20590776.2021.2004862

Hickman C (2020) We need to (find a way to) talk about… eco-anxiety. J Soc Work Pract 34(4):411–424. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650533.2020.1844166

Hickman C, Marks E, Pihkala P et al (2021) Climate anxiety in children and young people and their beliefs about government responses to climate change: a global survey. Lancet Planet Health 5(12):e863–e873. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2542-5196(21)00278-3

Ipsos (2023) A New World Disorder—Navigating a polycrisis: https://www.ipsos.com/sites/default/files/ct/news/documents/2023-06/Ipsos%20Global%20Trends%202023%20-%20Nicotine.pdf

Jang SJ, Chung SJ, Lee H (2023) Validation of the Climate Change Anxiety Scale for Korean Adults. Perspect Psychiatr Care 2023(1):e9718834. https://doi.org/10.1155/2023/9718834

Kim HW (2020) Reconcentration of millennials into Seoul Capital Region. J Korean Real Estate Anal Assoc 26(4):143–143

Kim YW, Park DN, Min HM (2018) The impact of psychological distance on risk-mitigative behaviors toward climate change among Koreans—a focus on the mediating effects of risk perception and the moderating effects of efficacy. Advert Res 118:127–170

Kwon SA, Kim S, Lee JE (2019) Analyzing the determinants of individual action on climate change by specifying the roles of six values in South Korea. Sustainability 11(7):1834

Lee SJ, Kim YW (2019) Communication strategies corresponding to the typology of Koreans’ perception on climate change risk. Korean J Public Adm 28(1):1–31

Lee YK (2015) Labor after neoliberalism: the birth of the insecure class in South Korea. Globalizations 12(2):184–202

Moon JP (2018) Spatial time and space that should be added to the Republic of Apartment Houses. J Soc Thoughts Cult 21(2):251–280

Ogunbode CA, Doran R, Hanss D et al (2022) Climate anxiety, wellbeing and pro-environmental action: correlates of negative emotional responses to climate change in 32 countries. J Environ Psychol 84: 101887. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2022.101887

Oh SB, Yun SJ (2022) A comparative study on the climate change perception and responding behaviors between generations: with a focus on the residents of the Seoul Metropolitan Area. Korean J Environ Educ 35(4):341–362

Ojala M, Cunsolo A, Ogunbode CA et al (2021) Anxiety, worry, and grief in a time of environmental and climate crisis: a narrative review. Annu Rev Environ Resour 46:35–58. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-environ-012220-022716

Park MY, Kim MA (2019) A photovoice study on the challenges and desires of married migrant women with school-aged children. Korean J Fam Soc Work 64(0):61–100

Pihkala P (2019) Climate anxiety. MIESL Mental Health Finland Polity Press, Helsinki

Social Survey (2022) KOSIS, https://kostat.go.kr/board.es?mid=a20111050000&bid=11761&act=view&list_no=428433. Accessed 21 Apr 2024

Song J, Chow R, Harootunian H et al. (2009) South Koreans in the debt crisis: the creation of a neoliberal welfare society. Duke University Press, New York

Steverson LA (2022) Eco-anxiety in a risk society. In: Mickey S, Vakoch D (ed) Eco-anxiety and pandemic distress: psychological perspectives on resilience and interconnectedness, OUP USA, New York, p 99–108

Tam KP, Chan HW, Clayton S (2023) Climate change anxiety in China, India, Japan, and the United States. J Environ Psychol 87: 101991. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2023.101991

Wang CC (1999) Photovoice: a participatory action research strategy applied to women’s health. J Women’s Health 8(2):185–192. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.1999.8.185

Wang CC (2006) Youth participation in photovoice as a strategy for community change. J Community Pract 14(1–2):147–161. https://doi.org/10.1300/J125v14n01_09

Wang CC, Burris MA (1997) Photovoice: concept, methodology, and use for participatory needs assessment. Health Educ Behav 24(3):369–387. https://doi.org/10.1177/109019819702400309

Whitmarsh L, Player L, Jiongco A et al (2022) Climate anxiety: What predicts it and how is it related to climate action?. J Environ Psychol 83: 101866. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2022.101866

WIN (2021) Climate change & sustainability. WIN. https://winmr.com/climate-change-and-sustainability-responsibility-and/. Last accessed April 2024

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yoonjung Chung contributed to the conception of the study, study design, data analysis, and writing the manuscript. Mi Seong Kim contributed to the data analysis and manuscript writing. In Han SONG supervised the study, wrote and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Yonsei University Institutional Review Board(7001988-202211-HR-1740-02) on November 15, 2022, through expedited review. It was conducted in accordance with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed consent

Participants were fully informed about the research procedures before enrollment and completed an informed consent form. Digital signatures were obtained by the researcher (Yoonjung Chung) between November 15 and 18, 2022, and the signed forms are securely retained. The consent covers participation, audio recording, data use, and publication.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chung, Y., Kim, M.S. & Song, I.H. Climate anxiety in the age of neoliberal individualization—a photovoice analysis among South Korean young generation. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 13, 61 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-06359-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-06359-6