Abstract

Linguistic complexity can be analyzed from two perspectives: group complexity and clause complexity. Complex nominal groups (NGs) are widely recognized as a defining characteristic of English academic writing. This study investigates the relationship between NG complexity and clause complexity across three disciplinary groups— Social Sciences (SS), Humanities and Natural Sciences (NS)—through the lens of dependency distance (DD). The results show that participant NGs are most complex in NS texts, whereas clauses exhibit the greatest complexity in Humanities texts. In general, there is a tendency to minimize the insertion of other clausal constituents between the verbal group and its object NG. Among the few inserted constituents, those with shorter DDs from the head verbs (HVs) to the object NGs are more frequent in Humanities texts, while those with longer DDs are more common in NS texts. Shorter in-between constituents typically form phrasal verbs with the HVs, while longer ones are mostly prepositional phrases functioning as circumstantial adjuncts. These findings suggest that NG complexity and clause complexity are not necessarily negatively correlated, both contributing to the overall linguistic complexity of English academic writing, and that adverbial groups functioning as comment adjuncts or intensifiers are not encouraged in English academic writing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Halliday (1994) identified two types of linguistic complexity: grammatical intricacy and lexical density. See example (1) quoted from Halliday and Matthiessen (1999: 343):

-

(1)

a. They shredded the documents before they departed for the airport.

b. Their shredding of the documents preceded their departure for the airport.

The hypotactic clause complex in (1a) is more complex in terms of grammatical intricacy, whereas the simple clause in (1b) is more complex in terms of lexical density. Lexical density in the Hallidayan sense (Halliday, 1994) can be measured by the number of lexical items per ranking clause in a sentence. For instance, the lexical density in (1a) is 2, whereas that in (1b) is 5. According to Halliday (1994: 351), “the nominal group is the primary resource used by the grammar for packing in lexical items at high density”. The simple clause in (1b) is arrived at through the nominalization of the two simple clauses in (1a) and the verbalization of the conjunction group before. The nominalization results in the complex NGs, and the verbalization results in the simple clause. From this perspective, the simplification of syntactic structures is negatively correlated with the complication of NGs.

Previous research indicates that clausal features are often characteristic of spoken texts (e.g., Halliday, 1987, 2004; de Haan, 1989; Bardovi-Harlig, 1992; Fang et al., 2006; Rimmer, 2006; Biber and Gray, 2016), while complex NGs are more typical of English academic writing (Atkinson, 1999; Biber and Finegan, 2001; Biber and Clark, 2002; Biber and Conrad, 2009; Biber and Gray, 2010). However, it is important to note that the complexity of NGs does not necessarily correlate with NG complexes. For example, in (2), a wonderful piece of property in Connecticut is complex, but it is still a simple NG, whereas my brother and I and snakes and birds are both NG complexes.

-

(2)

We had a wonderful piece of property in Connecticut, back up in the hills, and my brother and I were both very interested in snakes and birds. (Halliday and Matthiessen, 2014: 557)

Similarly, clause complexes are not equivalent to the complexity of clauses. Clause complexity can be measured by the number of clausal constituents in a clause, while NG complexity can be measured by the number of group constituents in an NG. According to the rank-scale hypothesis proposed by Halliday (1961), a clause may consist of one or several clausal constituents, with the central constituent being the verbal group that realizes the process. This verbal group may have one or more NGs realizing participants, as well as adverbial groups or prepositional phrases realizing circumstances. The more participants or circumstances are associated with a verbal group, the more complex the clause is. Similarly, an NG consists of one or more group constituents, with the head noun (HN) as the central constituent and the remaining constituents functioning as modifiers. The more modifiers an HN has, the more complex the NG is.

Both clause complexity and NG complexity can increase lexical density. In other words, lexical density may increase with either the expansion of group constituents or the addition of clausal constituents. For example:

-

(3)

a. They fly too quickly. (Halliday and Hasan, 1976: 4)

b. I only took the regular course. (Halliday and Hasan, 1976: 61)

The lexical density of (3a) is 3, but the only NG they consists of only one single word. In contrast, the lexical density of (3b) is 4, with the NG the regular course consisting of three words. Both too in (3a) and regular in (3b) function within groups, thereby increasing the complexity of the groups. However, only in (3b) functions within the clause, thereby contributing to increasing the complexity of the clause. On the one hand, there are 3 clausal constituents in (3a) and 4 in (3b), and hence (3b) is more complex than (3a) in terms of clause complexity. On the other hand, the average number of words per group is 1.33 in (3a) and 1.5 in (3b), indicating that (3b) is also more complex than (3a) in terms of group complexity.

Similarly, although the clause complex in (1a) is more complex than the single clause in (1b) in terms of grammatical intricacy, the two clauses in (1a) and the single clause in (1b) are all simple clauses, each consisting of three clausal constituents. Therefore, they have equivalent clause complexity but differ in lexical density. The average number of words per group is 1.43 in (1a) and 3.67 in (1b), indicating that (1b) is more complex than (1a) in terms of group complexity.

According to Biber et al. (2011: 22), “the complexity of conversation is clausal, whereas the complexity of academic writing is phrasal”. They suggested that English as a Foreign Language (EFL) writers undergo a shift from clause complexity to phrase complexity in academic writing. However, they defined clause complexity as the number of clauses within a sentence, rather than the number of groups or phrases within a clause. Phrase complexity, on the other hand, was defined as the number of phrases within a sentence. Halliday (2004) found a negative correlation between clause complexity and NG complexity across different types of text.

In the present study, we further explored the relationship between clause complexity, measured by the number of clausal constituents, and NG complexity, measured by the number of group constituents in the NG, based on Halliday’s (1961) rank-scale hypothesis. According to He and Zhang (2024), a clause always construes an event, which can be realized either by the verbal group or a participant NG of the verbal group. This perspective emphasizes the nominalization of verbal groups that shifts clauses to nominal groups. For example:

-

(4)

a. The end of the debate on “Schema 13” was followed by two days of discussion on that on religious life. (He and Zhang, 2024)

b. They ended the debate on “Schema 13” and then discussed on that on religious life for two days.

The relational verbal group of time was followed in (4a) does not construe an event. It links two events construed by the two nominalizations end and discussion. There are 3 clausal constituents in the simple clause in (4a), with an average of 6.67 words per constituent. This clause can be unpacked as the paratactic clause complex in (4b), which consists of 7 clausal constituentsFootnote 1 in total, with an average of 2.86 words per constituent. Thus, (4a) is more complex in terms of group complexity, while (4b) is more complex in terms of clause complexity. There are 2 participant NGs in (4a) and 3 in (4b). The average number of words per NG is 8.5 in (4a) and 3.33 in (4b). According to Halliday and Matthiessen (1999), nominalization shifts clausal constituents to group constituents, thereby increasing the complexity of the NGs.

Two types of rank-shifts can be identified. The first involves the adjectivalization of participant NGs and circumstance adverbial groups to function as premodifiers within the NGs. The second type pertains to the transformation of circumstance prepositional phrases functioning within clauses into post-modifier prepositional phrases functioning within NGs. From the perspective of dependency grammar, modifiers are governed by the HN within the NG, while participants and circumstances are governed by the head verb (HV) within the clause. The linear distance between the governor and its dependent is referred to as the dependency distance (DD) (Heringer et al., 1980). The complexity of an NG or a clause can be measured by the DD between the governor and the dependent.

Language functions as a self-organizing, self-regulating dynamic system (Köhler, 1986, 2012). According to the Menzerath–Altmann Law (Altmann, 1980), there is an inverse relationship between the size of a linguistic construct and the size of its components. It is hereby expected that an increase in NG complexity in English academic writing will result in a decrease in clause complexity. This study aims to investigate the relationship between clause complexity and NG complexity across various disciplinary groups in English academic writing. To achieve this, we conducted a corpus-based study of the DD between the HN and the first premodifier within the NG as an indicator of NG complexity, and the DD between the participant NG and the HV as an indicator of clause complexity.

“Syntactic complexity based on dependency grammar” reviews relevant studies on linguistic complexity in academic writing. “Methodology” outlines the methodology employed to examine the discipline sensitivity of clause complexity and NG complexity. The research findings are presented in “Clause complexities across disciplinary groups” and “Discussion”, starting with an exploration of the DD between the HN and the first premodifier across different disciplinary groups, followed by an analysis of the DD between the subject HN and the HV, and between the first premodifier of the object HN and the HV. “Conclusion” is dedicated to the discussion of the research findings.

Syntactic complexity based on dependency grammar

According to Biber et al. (2011), phrasal features are a more effective indicator of syntactic complexity than clausal features in academic writing. In a subsequent study, Biber et al. (2016) examined the writing of native English-speaking university students and observed a decrease in clausal features alongside an increase in phrasal features (such as the use of nouns and phrasal modifiers) as students progressed through their academic levels. This finding is supported by other studies, such as Varantola (1984), de Haan (1989), Halliday and Martin (1993), and Fang et al. (2006), which also highlight the heavy reliance on complex NGs in academic writing.

Linguistic complexity can be operationalized through four main parameters: length, ratio, index, and frequency, with length being the most commonly employed measure (Norris and Ortega, 2009). This includes metrics such as “mean length of T-unit, mean length of clause, clauses per T-units, and dependent clauses per clause” (Ortega, 2003: 493). Since these measures are typically applied at the clause level, it is essential to consider the mean length of NGs as a metric for assessing NG complexity.

Noun modification is significantly more prevalent in academic writing compared to conversation (Biber et al., 1999). According to Biber et al. (1999: 578), nearly 60% of the NGs in academic writing contain at least one modifier, whereas only approximately 15% of the NGs in conversation contain modifiers. Noun modifiers (i.e., attributive adjectives, nouns as nominal premodifiers, and prepositional phrases as nominal postmodifiers) within NGs represent the most commonly favored type of syntactic complexity in academic writing (Biber et al., 2011).

Syntactic complexity in dependency grammar can be measured by the mean DD, which reflects the cognitive effort involved in speech production and comprehension (Ferrer-i-Cancho, 2004). Dependency grammar centers on the asymmetrical pairwise relationship between two individual words (Tesnière, 1959), namely, the governor and the dependent. This framework is useful for uncovering linguistic features that may not be identifiable through traditional analyses of syntactic complexity (Kyle, 2016; Kyle and Crossley, 2018). Therefore, it is crucial to introduce dependency grammar and its application in measuring syntactic complexity.

Dependency analysis has gained considerable popularity in the field of natural language processing (Feng, 2013). Hudson (1995, 2010) considered dependency analysis as a cognitive framework that can be quantified through DD. The dependency structures of the two sentences in example (1) can be visualized as Fig. 1.

As shown in Fig. 1, the predicative verbal groups shredded and departed in (1a) each govern two dependents. The linear distances between the HV shredded and the subject pronoun they and the object HN documents are 1 and 2, respectively, while those between the HV departed and the subject pronoun they and the circumstance prepositional phrase for the airport are also 1 and 2, respectively. The predicative verbal group preceded in (1b) also governs two dependents. The linear distances between the HV preceded and the subject HN shredding and the object HN departure are 4 and 2, respectively.

A greater linear distance between the governor and the dependent indicates increased cognitive effort for the writer to establish their syntactic relationship. Since this binding operation is affected by the distance between the two words, DD is considered closely related to syntactic complexity (Liu, 2008). According to Gibson (1998, 2000), syntactic complexity is proportional to DD. Oya (2011) argued that the average DD of a sentence could be applied to calculate the complexity of the sentence. DD can also serve as a measure of syntactic difficulty and writing proficiency (Hudson, 1995; Jiang and Ouyang, 2018; Liu et al., 2017; Ouyang et al., 2022). The longer the DD, the more difficult the syntactic analysis of a sentence (Liu et al., 2009; Jiang and Liu, 2015).

Previous research (e.g., Hiranuma, 1999; Oya, 2013; Wang and Liu, 2017) also concerned the genre sensitivity of DD. According to Hiranuma (1999), more formal texts have longer DDs than less formal texts. Oya (2013), in a study of the mean DD across ten genres within a sub-corpus of the American National Corpus (ANC), found that Journal articles typically exhibited the longest mean DD, and Fiction, Ficlets and Jokes were the top-three sub-sections with the shortest mean DDs. However, a study based on the British National Corpus (BNC) by Wang and Liu (2017) found that genre affected the mean DD, but the effect was small: The mean DD was longer in the imaginative genre for sentence lengths ranging from 5 to 10, but it was longer in scientific texts for sentence lengths more than 10.

Halliday’s (2004) study on scientific English within the academic genre indicates that clausal features are more prevalent in soft science texts, whereas nominal features dominate in hard science texts. Clausal features align with the general narrative style, which tends to simplify phrasal components within the clause due to the constraints of working memory. In contrast, nominal features are associated with the strictly modified concepts and technical terms typical of research articles. A study by Gao and He (2023) found that the mean DD of the linguistics texts was longer than that of the physics and chemistry texts, reflecting the higher syntactic complexity of the language of linguistics.

It is commonly held that articles in hard sciences are denser in information and more difficult to understand (Gray, 2013, 2021), whereas soft sciences value stylistic variation and rhetorical sophistication (Becher and Trowler, 2001) and tend to use longer sentences with more detailed descriptions, qualifications and elaborations (Hyland, 2000). We can hereby expect longer mean DD in soft science texts than in hard science texts, as sentences in soft science texts are generally more complex than those in hard science texts (Gao and He, 2023). However, our study does not focus on comparing the mean DDs of soft and hard science texts. Rather, we aim to use the DD between the first premodifier and the HN of NGs as an indicator of NG complexity, and the DD between the HV of the verbal group and the participant NG as an indicator of clause complexity. The hypotheses underlying the research reported in this paper are as follows:

-

(1)

The DD from the HN to the first premodifier of the NG is longer in hard science texts than in soft science texts.

-

(2)

The DD from the HV to the participant NG is shorter in hard science texts than in soft science texts.

Methodology

Corpus

A typical research article usually consists of five sections: introduction, methodology, results, discussion, and conclusion. The abstract is the summarization of the research, including such key rhetorical moves as introduction, purpose, method, results and conclusion (Hyland, 2000). To summarize the whole article in a limited space, the article writer is impelled to compose a text with “maximum efficiency, clarity and economy” (Swales and Feak, 2009). As noted by Biber and Gray (2011), NGs contribute significantly to the compressed style of writing commonly observed in abstracts. Gray (2015) pointed out that abstracts showed the densest use of phrasal features, which serve as a strong indicator of NG complexity (Gray, 2013). Furthermore, full sentences are used in abstracts with no inserted non-linguistic information such as figures and tables. This is reliable for calculating clause constituents.

Abstracts exhibit distinct linguistic characteristics across disciplines (Hyland, 2000). In natural sciences (e.g., medicine, physics, and computer science), abstracts tend to use passive voice, emphasizing research methods and results while minimizing subjectivity (Pho, 2008). In contrast, abstracts in social sciences (e.g., linguistics, education, and management) often employ active voice, highlighting the research background and significance (Lores, 2004). Humanities abstracts, on the other hand, often incorporate more evaluative language, emphasizing the theoretical contributions of the research (Hyland and Tse, 2005). Given the varying organizational patterns, the linguistic resources influencing the DD in academic writing may similarly vary across disciplines, shaped by disciplinary norms.

This study is based on a self-built corpus of 1,050 research article abstracts, collected from research articles published between 2017 and 2022 in the Web of Science database. In selecting abstracts for this study, we adhered to the fundamental classification of disciplines into hard and soft sciences as outlined by Biglan (1973). Recognizing that this broad categorization may overlook the unique linguistic features of individual disciplines, we further subdivided soft sciences into Humanities and Social Sciences (SS). This approach resulted in three major disciplinary groups: Humanities (e.g., Literature and History), Social Sciences (e.g., Business and Politics), and Natural Sciences (e.g., Physics and Biology).

To enhance the representativeness of the self-built corpus, we also considered the Journal Citation Indicator (JCI), a metric that evaluates journal performance in Web of Science. Due to the variation of JCI values across disciplines, we balanced the JCI values by restricting the JCI range within each discipline. See Table 1 for a detailed breakdown.

Data collection

The corpus was converted into dependency-annotated treebanks for each sentence using SpaCy (Honnibal and Montani, 2019) in Python. A custom Python script was written to analyze the dependency relations within each sentence in the corpus. The corpus texts were first segmented into sentences. Within each sentence, the root HVs and their governed HVs correspond to the number of clauses. Furthermore, in any given clause, the number of HNs governed by an HV directly reflects the number of participant NGs. Example (5) demonstrates the calculation of the DD between the HV and the subject HN, as well as between the HV and the object NG.

-

(5)

This article discusses the largely forgotten antiwhaling protests in Norway and Japan at the beginning of the twentieth century. (Humanities)

The DD between the HV discusses and the subject HN article is 1, and that between the HV discusses and the first premodifier of the object NG the largely forgotten anti-whaling protests is also 1. Within the NG, the DD between the subject HN article and the determiner this is 1, and the DD between the object HN protests and the determiner the is 4.

In total, we collected 21,246 participant NGs, including 8497 in SS texts, 6111 in Humanities texts, and 6638 in NS texts. See Table 2.

However, the DD between the HV and the subject HN does not necessarily reflect clause complexity, as it may be influenced by the presence of post-modifiers of the HN. For example:

-

(6)

a. Impending abolition of slavery in Brazil during the late nineteenth century meant the potential shortage of labor for Southeast coffee planters. (Humanities)

b. A sharp and statistically significant increase in SRB appears with the war. (Humanities)

Both (6a) and (6b) consist of three clause constituents, and hence they exhibit the same clause complexity. The DD between the HV meant and the subject HN abolition is 10 in (6a), whereas the DD between the HV appears and the subject HN increase is 3 in (6b). However, the three prepositional phrases of slavery, in Brazil and during the late nineteenth century in (6a) and the one prepositional phrase in SRB in (6b) are the rank-shifted use of phrases within NGs, functioning as post-modifiers of the HNs in the NGs. These phrases have their own syntactic structures, and so it would be inappropriate to include them in the calculation of the lengths of the NGs.

In the present study, we considered only the premodifiers of the HN as contributing to the complexity of the NG. From this perspective, the DD between the first premodifier impending and the subject HN abolition is 1 in (6a), whereas the DD between the first premodifier a and the subject HN increase is 5 in (6b), indicating that the subject NG in (6b) is more complex than that in (6a).

Data analysis

In our analysis, we employed the independent t-test in SPSS 29 to compare the mean DDs between different disciplinary groups and to determine whether the differences were statistically significant. When the variances of the two groups were unequal, we utilized Welch’s t-test. The formula for the t-test statistic is as follows:

where \({\bar{X}}_{1}\) and \({\bar{X}}_{2}\) represent the means of the two groups, \({s}_{1}^{2}\) and \({s}_{2}^{2}\) are the sample variances of the two groups, and \({n}_{1}\) and \({n}_{2}\) are the sample sizes of the two groups. We set the significance level at 0.05 for the critical t-value. A significant difference between the two groups is indicated if the t-value exceeds the critical t-value or if p < 0.05. It should be noted that we used the independent t-test to compare the mean differences between the data groups. The result, however, might be affected by the extreme values, and so boxplots were employed to identify and address the potential outliers in the dataset.

Additionally, we investigated the relationship between the DD and its frequency using the Menzerath–Altmann Law (Altmann, 1980), which is mathematically modeled by the following formula:

where the variable x represents the size of the whole unit, and y represents the average size of the subunits. In this study, x denotes the DD, and y represents the corresponding frequency.

This function integrates a power law and an exponential decay. When x is small, the power law \(y=a{x}^{b}\) predominates, which controls the initial growth or decay rate of the function. As x increases, the exponential decay takes over, which causes the function to decay rapidly and approach zero. Parameter a in the function is a scaling constant that sets the initial value or height of the curve on the y-axis. Parameter b influences the initial rate of growth or decay. If b > 0, the curve initially stretches upward rapidly as x increases. A larger b results in a faster increase in y as x grows. Conversely, if b < 0, the curve decreases rapidly as x grows. If b = 0, the function behaves as a pure exponential decay. Parameter c controls the rate of exponential decay. A larger c indicates a faster decay, while a smaller c results in a slower decay.

We also employed Pearson’s Chi-squared test in SPSS to analyze the distribution of the data across disciplinary groups and determine whether the differences were statistically significant. The formulas for conducting Pearson’s Chi-squared test are as follows:

where \({O}_{{ij}}\) represents the observed frequency in each category, and \({E}_{{ij}}\) is the expected frequency for each category. The indices i and j correspond to the rows and columns, respectively, in the contingency table, while n is the total number of observations. A significant difference between the two variables is indicated if the \({\chi }^{2}\) value exceeds the critical value or if p < 0.05.

NG complexities across disciplinary groups

In this section, we compared the average NG lengths across the three disciplinary groups. The DD between the HN and its first premodifier is used as an indicator of NG complexity. The collected data are presented in Table 3.

The data in Table 3 reveal that the number of HNs without premodifiers is significantly larger in SS texts compared to Humanities texts (χ² = 15.593, p = 0.000 < 0.05) and NS texts (χ² = 39.881, p = 0.000 < 0.05). Additionally, the number of HNs without premodifiers in Humanities is also significantly different from that in NS texts (χ² = 4.443, p = 0.035 < 0.05), further indicating that HNs without premodifiers are less common in NS texts. Furthermore, subject HNs without premodifiers are significantly more frequent than object HNs without premodifiers across all three disciplinary groups. However, the proportion of object HNs without premodifiers relative to all object HNs is the smallest in NS texts (13.79%), compared to SS texts (21.84%) and Humanities texts (19.75%). This further supports the finding that object HNs are less likely to occur without premodifiers in NS texts.

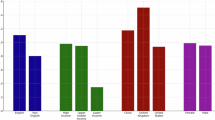

An independent t-test reveals that the mean DD between the HNs and the first premodifiers in SS texts (1.577) is not significantly different from that in Humanities texts (1.610) (t = −1.599, df = 8493.361; p = 0.110 > 0.05). However, both SS and Humanities texts show significantly different mean DDs compared to NS texts (1.781). Specifically, the mean DD in SS texts is significantly smaller than in NS texts (t = –9.521, df = 8954.937; p < 0.001), and the mean DD in Humanities texts is also significantly smaller than in NS texts (t = –7.400, df = 8484.807; p < 0.001). This suggests that the mean DD between the first premodifier and the HN is longest in NS texts. The boxplots illustrating these data are shown in Fig. 2.

Figure 2 illustrates that the majority of DDs fall within the range of 1 to 3 across all the three disciplinary groups. The outliers extend from 4 to 15 in SS texts, from 4 to 9 in Humanities texts, and from 4 to 17 in NS texts. Example (7) displays the extreme outliers in each of the three disciplinary groups. The DD in (7a) is 15, as the brackets are counted as words in the dependency treebank. Similarly, the possessive case in (7b) is also counted as a word.

-

(7)

a. Findings demonstrate that passive (receiving political information), but not active (producing political information) connection increases dyadic representation perceptions. Collective representation perceptions, by contrast, were not affected by either type of connection. (SocialSci.)

b. Using political discourse analysis, this study compares the South Korean Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s Final Report to the 2016 national history textbook. (Humanities)

c. In this work, we experimentally observe for the first time nanoscale plasmonic enhanced Electromagnetically Induced Transparency (EIT) and Velocity Selective Optical Pumping (VSOP) effects in miniaturized Integrated Quantum Plasmonic Device (IQPD) for D-2 transitions in rubidium (Rb). (NaturalSci.)

The data further indicate that the DD 1 accounts for a large proportion in all the three disciplinary groups: 62.77% in SS texts, 61.91% in Humanities texts, and 51.26% in NS texts. Consequently, the median DD is 1 for SS and Humanities texts, while it is 2 for NS texts. The Chi-squared test shows significant differences in the frequency of DD 1, as well as in the total frequency of HNs with premodifiers between NS texts and both SS texts (χ² = 35.786, p < 0.001) and Humanities texts (χ² = 27.207, p < 0.001). However, no significant difference is observed between SS and Humanities texts (χ² = 0.166, p = 0.684 > 0.05). These results further support the presence of longer NGs in NS texts.

We then compared the frequency distributions of different DDs between the HNs and the first premodifiers across the three disciplinary groups. Based on the data shown in Table 3, we expected that the distributions for all the three groups of data would adhere to the Menzerath–Altmann Law. This relationship is illustrated in Fig. 3 and summarized in Table 4. The results of the non-linear regression analysis are shown in Table 5.

The highest value of parameter a in SS texts indicates that, for a given NG length, the overall frequency of NGs is greatest in SS texts. The highest value of parameter b in Humanities texts suggests that, for shorter NGs, the frequency increases most rapidly in Humanities texts. Meanwhile, the highest value of parameter c indicates that, for longer NGs, the frequency decays most quickly. In contrast, the lowest values of both b and c in NS texts imply that, for shorter NGs, the frequency increases most slowly, and for longer NGs, the frequency decays most slowly. The values of parameters b and c in SS texts lie between those in Humanities and NS texts.

This analysis supports our expectation that the distributions of NG lengths across the three disciplinary groups conform to the Menzerath–Altmann Law, and our first hypothesis that NGs in NS texts exhibit the highest complexity in terms of length.

Clause complexities across disciplinary groups

In this section, we analyzed the DDs between the HVs of the verbal groups and the subject HNs, as well as the DDs between the HVs of the verbal groups and the first premodifiers of the object HNs. A longer DD indicates greater syntactic complexity, as it reflects the presence of additional clausal constituents between the verbal group and the participant NG.

DD between HV and subject HN

As shown in Table 2, we collected a total of 11,912 subject HNs governed by the HVs from the corpus. The DDs between the HVs and the subject HNs are shown in Table 6.

Table 6 reveals that SS texts contain a greater number of subject HNs compared to the other two disciplinary groups. The independent t-test indicates that the mean DD between the subject HNs and their governing HVs in SS texts is significantly shorter than in Humanities texts (t = –6.231, df = 6339.07, p < 0.001) and in NS texts (t = –8.384, df = 7269.031, p < 0.001). However, the mean DD between the HVs and the subject HNs in Humanities texts and NS texts is not significantly different (t = –1.229, df = 7173, p = 0.219 > 0.05). This result contradicts our hypothesis that the DD from the HV to the participant NG is shorter in hard science texts than in soft science texts. The boxplots for these data are illustrated in Fig. 4.

Figure 4 shows that in SS texts, most DDs are clustered within the range of 1 to 3, with outliers extending from 4 to 29 and from −1 to −13. In Humanities texts, the majority of DDs fall between −3 and 5, with outliers ranging from 6 to 43 and from −4 to −8. In NS texts, most DDs are found within the range of −2 to 6, with outliers ranging from 7 to 41 and −4. Example (8) displays the extreme outliers in each of the three disciplinary groups:

-

(8)

a. Impostorism, a phenomenon whereby a person perceives that the role they occupy is beyond their capabilities and puts them at risk of exposure as a fake, has attracted plentiful attention in the empirical literature and popular media. (SocialSci.)

b. The success of Zamenga Batukezanga (1933–2000), still the most widely read and recognized writer in the DRC, as well as the recent rise of comic book writer Jeremie Nsingi, the author of many fanzines and small-run comic strips, reflect how these genres reconstruct canons and illustrate the emergence of a popular social imaginary. (Humanities)

c. The links between temporal activation-induced changes in the metabolism of such macrophages and the influence this has on their functional states, along with the realization that metabolites play both intrinsic and extrinsic roles in the cells that produce them, have focused attention on the metabolism of wound healing. (NaturalSci.)

It should be noted that all negative DDs arose from the reversal of the subject-verb structure. The extreme outlier in SS texts is (9a), in which the DD between the subject HN role to the HV overlooked is −13. Other examples of negative DDs are provided in (9b) and (9c).

-

(9)

a. Overlooked in analyses of why the public often rejects expert consensus is the role of the news media. (SocialSci.)

b. How strong is the current Western hegemonic order, and what is the likelihood that China can or will lead a successful counterhegemonic challenge? (SocialSci.)

c. Central to our theorizing is a multifaceted framework that yields four quadrants of target response: reciprocation, retreat, relationship repair, and recruitment of support. (SocialSci.).

It can also be seen that the DD 1 between the HV and the subject HN accounts for a large proportion in all the three disciplinary groups: 59.89% in SS texts, 56.05% in Humanities texts, and 48.95% in NS texts. The Chi-squared test reveals no significant difference between SS texts and Humanities texts in terms of the frequency of DD 1 and the total frequency of subject HNs (χ² = 3.234, p = 0.072 > 0.05). However, significant differences are found between SS and NS texts (χ² = 29.203, p < 0.001) and between Humanities and NS texts (χ² = 11.329, p < 0.001). This indicates that the frequency of DD 1 is notably lower in NS texts compared to the other two disciplinary groups. This could be due to the generally higher number of inserted constituents between the subject HNs and the HVs in NS texts, or the presence of more post-modifiers in the subject HNs within NS texts, further confirming the greater clause complexity in NS texts.

We then compared the distributions of the frequencies of different DDs between the HVs of the verbal groups and the HNs of the subject NGs across the three disciplinary groups. Based on the data shown in Table 6, we expected that the distributions of the three groups of data would abide by the Menzerath–Altmann Law. Table 7 and Fig. 5 illustrate the distribution patterns, and the results of the non-linear regression analysis are shown in Table 8.

The highest value of parameter a observed in SS texts suggests that, for a given DD, its overall frequency is highest in SS texts. It is important to note that all the three b values are negative. A larger absolute value of b corresponds to a more rapid decline of the curve for smaller DDs. The highest absolute b value in SS texts indicates that the DD frequencies decrease most rapidly when the DDs are small. Conversely, the c value with the larger negative magnitude in Humanities texts signifies the higher rate of increase for larger DDs, with SS texts following in that order. The highest c value in NS texts implies that, for larger DDs, the frequency continues to decline in NS texts. These findings suggest that, while the mean DD is slightly longer in NS texts compared to Humanities texts, the DDs are generally more extensive in Humanities texts than in NS texts.

This analysis supports our expectation that the distributions of the three groups of data conform to the Menzerath-Altmann Law. Specifically, the frequency curve continuously declines in NS texts, while it turns upward in the other two disciplinary groups as the DDs increase. We can hereby conclude that, although the research finding contradicts our hypothesis that the DD from the HV to the participant NG is shorter in hard science texts than in soft science texts, extremely long DDs are relatively more prevalent in soft science texts than in hard science texts.

DD between HV and object NG

This section analyzed the DDs between the HVs and the bare object HNs or the first premodifiers of the object HNs. See Table 9 for the relevant data.

As shown in Table 9, the number of object HNs is larger in SS texts compared to the other two disciplinary groups. The longest DD between the HV and the object NG, measuring 18, occurs in Humanities texts. An independent t-test reveals that the mean DD between the object NG and the HV in Humanities texts is significantly longer than in SS texts (t = −5.385, df = 3507.862, p < 0.001) and in NS texts (t = −5.493, df = 3895.911, p < 0.001). However, there is no significant difference in the mean DD between SS texts and NS texts. (t = 0.507, df = 6745, p = 0.612 > 0.05). The corresponding boxplots are displayed in Fig. 6.

Figure 6 shows that the majority of DDs in SS and NS texts are DD 1, while in Humanities texts, they range from 1 to 2. The outliers vary across disciplines, spanning from 2 to 7 and −2 to −10 in SS texts, from 3 to 18 and −2 to −10 in Humanities texts, and from 2 to 10 and −2 to −9 in NS texts. The extreme outlier DD 18 appears in Humanities texts because of the inserted prepositional phrase functioning as circumstantial adjunct in the Hallidayan sense (Halliday, 1994). See example (10):

-

(10)

They aimed to break on the world stage, reclaimed an India that included what was non-Indian, and put forward, through translation and a cut-and-paste collation of the world and world literature, an idea of internationalism and interconnectedness where provincialism was the enemy. (Humanities)

It should be noted that those negative DDs are the result of the reversed verb-object structure, where interrogative pronouns or relative pronouns function as objects. For example:

-

(11)

a. What type of trade agreement is the public willing to accept? (SocialSci.)

b. Our estimates imply that the average abnormal returns that CEOs earn from their purchases increase from 3% to 58%. (SocialSci.)

It is also evident that the proportion of DD 1 between the HV and the object NG is significantly larger in all the three disciplinary groups compared to that between the HV and the subject HN. Specifically, it accounts for 97.37% in SS texts, 94.22% in Humanities texts, and 98.02% in NS texts. The Chi-squared test reveals no significant differences in the frequency of DD 1 and the total frequency of object NGs between SS texts and Humanities texts (χ² = 0.813, p = 0.367 > 0.05), between SS texts and NS texts (χ² = 0.037, p = 0.847 > 0.05), and between NS texts and Humanities texts (χ² = 1.067, p = 0.302 > 0.05). This suggests that most HVs are directly followed by their object NGs in all the three disciplinary groups.

We then compared the distribution of DD frequencies between the HVs of the verbal groups and the object NGs (see Table 10 and Fig. 7). The results of the non-linear regression analysis are shown in Table 11.

It can be seen from Table 11 that all the b values and c values are negative. The highest value of parameter a in Humanities texts indicates a relatively higher baseline for this disciplinary group. The lowest absolute b value indicates the slowest rate of decrease for shorter DDs, and the c value with the smallest negative magnitude indicates the slowest rate of increase for longer DDs in Humanities texts. This implies that Humanities texts tend to have relatively more inserted constituents between the HVs and the object NGs. In contrast, the lowest value of parameter a in NS texts reveals a relatively lower baseline. The highest absolute b value and the largest negative magnitude of the c value indicate that the frequency of DDs decreases most rapidly for shorter DDs in NS texts. However, as the DD increases, this decrease slows down and eventually turns upward, leading to the fastest rate of increase. This suggests that shorter inserted constituents between the HV and the object NG are least frequent in NS texts, while longer constituents tend to occur more frequently in NS texts than in the other two disciplinary groups.

This analysis confirms our expectation that the distributions of the three groups of data conform to the Menzerath–Altmann Law. However, it is still too early to conclude, based on these findings, that clauses in Humanities texts exhibit the greatest complexity among the three disciplinary groups, while those in NS texts demonstrate the least complexity.

Discussion

The corpus-based analysis of NG complexity across disciplinary groups found that SS texts contain the largest number of participant NGs without premodifiers, compared to the other two disciplinary groups. Additionally, these texts exhibit the shortest mean DD between the first premodifiers and the HNs of the NGs that have premodifiers. NGs in SS texts are the least complex, whereas those in NS texts are generally the most complex, in terms of the DD between the first premodifier and the HN of the NG. This supports our first hypothesis that the DD from the HN to the first premodifier of the HN is longer in hard science texts than in soft science texts. However, the analysis of clause complexity reveals that the mean DD between the HVs and the subject HNs is longest in NS texts and shortest in SS texts. This contradicts our second hypothesis that the DD between the HVs and subject HNs would be longer in soft science texts than in hard science texts. The frequency of DD 1 between the HVs and subject HNs is notably lower in NS texts compared to the other two disciplinary groups, with many short constituents inserted in between. This suggests that, although the mean DD between the HVs and the subject HNs is longest in NS texts, longer DDs are not necessarily more likely to occur in NS texts.

The constituents between the HVs and the subject HNs may include post-modifiers of the subject HNs, adverbial groups modifying the VGs, or the auxiliary verbs of the HVs. The relatively higher frequency of shorter DDs and fewer longer DDs in NS texts indicates that there may be a greater presence of adverbial groups modifying the verbal groups, or that the post-modifiers of the subject HNs are predominantly phrases rather than full clauses. For example:

-

(12)

a. For unbounded operators, after suitable discretization, the norm of the Hamiltonian can be very large, which significantly increases the simulation cost. (NaturalSci.)

b. Several quantum algorithms have been proposed to determine the singular values and their associated singular vectors of a given matrix. (NaturalSci.)

On the other hand, the relatively fewer shorter DDs and more longer DDs in Humanities texts indicate that the post-modifiers of the subject HNs are more likely to be clauses rather than phrases. This aligns with Hyland (2009), who argues that writing in Humanities often features a greater use of nested clauses. For example:

-

(13)

The way that the process of decolonization unfolded in Malaya did, furthermore, not lead to any major nationalization of foreign-held assets. (Humanities)

However, the verb-object structure remains relatively clear. The corpus-based analysis shows that the number of inserted constituents between the HVs and the object NGs is very small in all the three disciplinary groups, and the mean DD between the HVs and the object NGs is shortest in NS texts and longest in Humanities texts. It can be concluded that adjuncts are not encouraged to be inserted between the HVs and object NGs in any of the three disciplinary groups. The inserted constituents between the HVs and the object NGs are typically clausal constituents, the shorter ones being adverbial groups functioning as comment adjuncts, and the longer ones being prepositional phrases functioning as circumstantial adjuncts. For example:

-

(14)

a. In this work, we experimentally observe for the first time nanoscale plasmonic enhanced Electromagnetically Induced Transparency (EIT). (NaturalSci.)

b. Here, we determine experimentally and theoretically the second harmonic generation (SHG) efficiency in ultrahigh-Q photonic crystal nanocavities. (NaturalSci.)

c. We study experimentally the third harmonic generation from metasurfaces composed of symmetry broken silicon metaatoms and reveal that the harmonic generation intensity depends critically on the asymmetry parameter. (NaturalSci.)

As expected, in (14a), the DD between the HV observe and the first premodifier nanoscale of the object NG is 5, and the inserted constituent is a prepositional phrase for the first time. In (14b), however, the DD between the HV determine, and the first premodifier the of the object NG is 4, and the inserted constituent is a paratactic adverbial group complex experimentally and theoretically. In (14c), the DD between the HV study and the first premodifier the of the object NG is 2, but the inserted clausal constituent experimentally is a circumstantial adjunct. The examples were all collected from the NS texts. In the other two disciplinary groups, we might expect to find comment adjuncts. For example:

-

(15)

a. Fogel realized more and more the salience of ethics in the economy, and even taught (philosophically unsophisticated) courses on business ethics. (Humanities)

b. The special tragic sense generated carries along the inferences of two equally impossible situations. (Humanities)

c. The authors also rule out several alternative explanations. (SocialSci.)

However, we retrieved only a very small number of adverbial groups functioning as comment adjuncts, as in (15a). Instead, the inserted constituents between the HVs carries in (15a) and rule in (15b), and the first premodifiers the and several both form phrasal verbs with the HVs. For verification, we collected all the inserted single-word constituents between the HVs and the object NGs to test the relationship between the HVs and the inserted constituents. In total, we collected 22 adverb types, totaling 91 tokens from the three disciplinary groups. See Table 12.

It can be seen from Table 12 that the frequency of inserted adverbs between the HVs and the object NGs is the highest in Humanities texts. The most frequently occurring adverbs, such as out, together, up and forward, combine with the preceding verbs to form phrasal verbs (e.g., carry out, bring together, open up, and put forward). There are only a small number of adverbs that do not form phrasal verbs with the preceding verbal groups. For example, take largely and translate locally in Humanities texts, as well as study experimentally and demonstrate here in NS texts, function as circumstances within the clauses. Circumstantial adverbial groups are clausal constituents, whereas adverbs in phrasal verbs are not.

Conclusion

This study investigated the dynamic relationship between NG complexity and clause complexity across different disciplinary groups of academic writing. DD was used as a metric, with NG complexity measured by the DD between the HN and its first premodifier, and clause complexity measured by the DD between the HV and the participant NG. The corpus-based study of the NG complexity across disciplinary groups shows that NGs are most complex in NS texts with respect to DD, confirming our first hypothesis that hard science texts exhibit longer DDs within NGs compared to soft science texts. The corpus-based study of the clause complexity across disciplinary groups shows that the DD between the HV and the subject HN is longest in NS texts and shortest in SS texts, while the DD between the HV and the object NG is longest in Humanities texts and shortest in NS texts. This does not support our second hypothesis that soft science texts exhibit longer DDs within clauses compared to hard science texts. It can, therefore, be concluded that NG complexity and clause complexity are not necessarily negatively correlated across disciplinary groups; instead, both contribute to the overall linguistic complexity of English academic writing.

The longest mean DD between the HVs and the subject HNs in NS texts can be attributed to the presence of post-modifiers in the NGs and inserted clausal constituents. The shorter inserted constituents between the HVs and the object NGs in Humanities texts tend to form verb phrases with the HVs, while the longer inserted constituents in NS texts result from the inserted prepositional phrases that function as circumstantial adjuncts. Moreover, adverbial groups functioning as comment adjuncts or intensifiers are not encouraged in academic writing, reflecting the preference for clarity and precision in scholarly discourse.

The findings of this study have important implications for discipline-specific English academic writing instruction. They emphasize the need to prioritize NG compression in NS writing and clausal elaboration in SS writing. In NS writing, students should be trained to construct compact, yet precise, NGs that avoid ambiguity while maintaining clarity. In contrast, SS and Humanities writing benefit from strategically incorporating post-modifiers and nested clauses to enhance grammatical complexity without sacrificing readability. However, across all disciplines, the use of intensifier adverbs—especially those placed between the verbal group and object NG—should be avoided, as they can diminish the precision and clarity expected in academic writing. In practical terms, instructors should establish a discipline-specific balance between linguistic complexity and readability. A phased approach is recommended to gradually enhance syntactic complexity. Instruction can begin with exercises focused on adding clausal constituents, followed by the inclusion of noun modifiers, and eventually progressing to the shift of clauses into NGs through nominalization. This step-by-step strategy supports a smooth transition from clause complexity to NG complexity, helping students refine their writing style and meet the syntactic demands of academic writing.

The study does have some limitations. First, the corpus used is relatively small, which may not fully capture the nuanced differences in syntactic complexity across disciplines. Future research should expand the dataset to include full-length articles for a more comprehensive analysis. Second, the study focuses on a synchronic analysis, which may not fully address the interaction between clause-based and NG-based complexities. Future research should prioritize longitudinal studies to examine how academic writing evolves in its balance between these two types of complexity, particularly through processes like nominalization, a powerful strategy for shifting clauses into NGs (Halliday, 1994). Additionally, a comparative analysis between novice English academic writers or writers of English as a foreign language and expert English academic writers is needed to explore how language proficiency influences syntactic choices. Finally, this study focused solely on the grammatical dimension. Future complexity analyses should consider incorporating semantic, pragmatic, and cognitive dimensions. Metrics such as lexical diversity and logical connective density would offer a more holistic understanding of linguistic complexity in English academic writing.

Data availability

The datasets are available from the corresponding author on request.

Notes

The conjunction group and then operates outside the rank-scale (He and Yang 2015: 344) to function as the Relator between two clauses and, as such, is not considered a clausal constituent.

References

Altmann G (1980) Prolegomena to Menzerath’s law. Glottometrika 2(2):1–10

Atkinson D (1999) Scientific Discourse in Sociohistorical Context: The philosophical transactions of the royal society of London, 1675–1975. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Mahwah, New Jersey

Bardovi-Harlig K (1992) A second look at T-unit analysis: Reconsidering the sentence. TESOL Q 26:390–395

Becher T, Trowler PR (2001) Academic Tribes and Territories: Intellectual enquiry and the cultures of disciplines (2nd edn). The Society for Research into Higher Education & Open University Press, Buckingham

Biber D, Clark V (2002) Historical shifts in modification patterns with complex noun phrase structures. In: Fanego T, Pérez-Guerra J, López-Couso MJ (eds.) English historical syntax and morphology. John Benjamins, Amsterdam, pp 43–66

Biber D, Conrad S (2009) Register, genre, and style. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Biber D, Finegan E (2001) Diachronic relations among speech-based and written registers in English. In: Conrad S, Biber D (eds.) Variation in English: Multi-dimensional Studies. Longman, London, pp 66–83

Biber D, Gray B (2010) Challenging stereotypes about academic writing: Complexity, elaboration, explicitness. J Engl Acad Purp 9:2–20

Biber D, Gray B (2011) Grammatical change in the noun phrase: The influence of written language use. Engl Lang Linguist 15(2):223–250

Biber D, Gray B (2016) Grammatical complexity in academic writing: Linguistic change in writing. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Biber D, Gray B, Poonpon K (2011) Should we use characteristics of conversation to measure grammatical complexity in L2 writing development?. TESOL Q 45(1):5–35

Biber D, Gray B, Staples S (2016) Predicting patterns of grammatical complexity across textual task types and proficiency levels. Appl Linguist 37:639–668

Biber D, Johansson S, Leech G, Conrad S, Finegan E (1999) Longman Grammar of Spoken and Written English. Pearson Education, Harlow

Biglan A (1973) The characteristics of subject matter in different academic areas. J Appl Psychol 57:195–203

de Haan P (1989) Postmodifying clauses in the English noun phrase: a corpus-based study. Rodopi, Amsterdam

Fang Z, Schleppergrell M, Cox B (2006) Understanding the language demands of schooling: Nouns in academic registers. J Lit Res 38:247–273

Feng Z (2013) School of modern linguistics. The Commercial Press, Beijing

Ferrer-i-Cancho R (2004) Euclidean distance between syntactically linked words. Phys Rev E 70: 056135

Gao N, He Q (2023) A corpus-based study of the dependency distance differences in English academic writing. Sage Open 13(3):1–12

Gibson E (1998) Linguistic complexity: locality of syntactic dependencies. Cognition 68:1–76

Gibson E (2000) The dependency locality theory: A distance-based theory of linguistic complexity. In: Marantz A, Miyashita Y, O’Neil W (eds.) Image, language, brain. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, pp 95–126

Gray B (2013) More than discipline: uncovering multi-dimensional patterns of variation in academic research articles. Corpora 8(2):153–181

Gray B (2015) On the complexity of academic writing: Disciplinary variation and structural complexity. In: Cortes V, Csomay E (eds.) Corpus-based research in applied linguistics: studies in honor of Doug Biber [Studies in Corpus Linguistics]. John Benjamins, Amsterdam, pp 49–78

Gray B (2021) The register-functional approach to grammatical complexity. Theoretical foundation, descriptive research findings, application. Routledge, New York

Halliday MAK (1961) Categories of the theory of grammar. Word 17(2):241–292

Halliday MAK (1987) Spoken and written modes of meaning. In: Horowitz R, Samuels SJ (eds.) Comprehending oral and written language. Academic Press, New York, pp 55–82

Halliday MAK (1994) An introduction to functional grammar (2nd edn). Edward Arnold, London

Halliday MAK (2004) Writing science: Literacy and discursive power. In: Webster J (ed.) The language of science. Continuum, New York, pp 199–225

Halliday MAK, Hasan R (1976) Cohesion in english. Longman, London

Halliday MAK, Martin JR (1993) Writing science: literacy and discursive power. Falmer Press, London

Halliday MAK, Matthiessen CMIM (1999) Construing experience through meaning: a language-based approach to cognition. Continuum, London

Halliday MAK, Matthiessen CMIM (2014) An introduction to functional grammar (4th edn). Routledge, London/New York

He Q, Zhang Q (2024) A corpus-based study of live grammatical metaphor in English academic writing. Stud Neophilol 96:1–20

Heringer HJ, Strecker B, Wimmer R (1980) Syntax: Fragen, Lösungen, Alternativen. Fink, München

Hiranuma S (1999) Syntactic difficulty in English and Japanese: a textual study. UCL Working Pap Linguist 11:309–322

Honnibal M, Montani I (2019) SpaCy 2: natural language understanding with bloom embeddings, convolutional neural networks and incremental parsing. Version 2.0.18. https://spacy.io

Hudson R (1995) Measuring syntactic difficulty. Manuscript, University College, London

Hudson R (2010) An introduction to word grammar. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Hyland K (2000) Disciplinary discourses: social interactions in academic writing. Longman, London

Hyland K (2009) Academic discourse: english in a global context. Continuum, London/New York

Hyland K, Tse P (2005) Hooking the reader: a corpus study of evaluative that in abstracts. Engl Specif Purp 24(2):123–139

Jiang J, Liu H (2015) The effects of sentence length on dependency distance, dependency direction and the implications-based on a parallel English–Chinese dependency Treebank. Lang Sci 50:93–104

Jiang J, Ouyang J (2018) Minimization and probability distribution of dependency distance in the process of second language acquisition. In: Jiang J, Liu H (eds.) Quantitative analysis of dependency structures. de Gruyter, Berlin/New York, pp 167–190

Köhler R (1986) Zur linguistischen Synergetik. struktur und Dynamik der Lexik. Brockmeyer, Bochum

Köhler R (2012) Quantitative syntax analysis. de Gruyter, Berlin/New York

Kyle K (2016) Measuring syntactic development in L2 writing: fine grained indices of syntactic complexity and usage-based indices of syntactic sophistication. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. Georgia State University, Atlanta, GA

Kyle K, Crossley SA (2018) Measuring syntactic complexity in L2 writing using fine-grained clausal and phrasal indices. Mod Lang J 102:333–349

Liu H (2008) DD as a metric of language comprehension difficulty. J Cogn Sci 9(2):159–191

Liu H, Hudson R, Feng Z (2009) Using a Chinese Treebank to measure dependency distance. Corpus Linguist Linguistic Theory 5(2):161–174

Liu H, Xu C, Liang J (2017) Dependency distance: a new perspective on syntactic patterns in natural languages. Phys Life Rev 21:171–193

Lores R (2004) On RA abstracts: from rhetorical structure to thematic organization. Engl Specif Purp 23(3):280–302

Norris JM, Ortega L (2009) Towards an organic approach to investigating CAF in instructed SLA: the case of complexity. Appl Linguist 30:555–578

Ortega L (2003) Syntactic complexity measures and their relationship to L2 proficiency: a research synthesis of college level L2 writing. Appl Linguist 24:492–518

Ouyang J, Jiang J, Liu H (2022) Dependency distance measures in assessing L2 writing proficiency. Assess Writ 51:1–14

Oya M (2011) Syntactic dependency distance as sentence complexity measure. Proceedings of the 16th international conference of pan-Pacific association of applied linguistics, 313–316. http://paaljapan.org/conference2011/ProcNewest2011/pdf/poster/P-13.pdf

Oya M (2013) Degree centralities, closeness centralities, and dependency distances of different genres of texts. Selected papers of the 17th conference of Pan-Pacific Association of Applied Linguistics, 42–53. http://www.paaljapan.org/conference2012/pdf/006oya.pdf

Pho PD (2008) Research article abstracts in applied linguistics and educational technology: a study of linguistic realizations of rhetorical structure and authorial stance. Discourse Stud 10(2):231–250

Rimmer W (2006) Measuring grammatical complexity: the Gordian knot. Lang Test 23:497–519

Swales JM, Feak CB (2009) Abstracts and the writing of abstracts. University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor

Tesnière L (1959) Elèments de syntaxe structural.: Klincksieek, Librairie C

Varantola K (1984) On noun phrase structures in engineering English. University of Turku, Turku

Wang Y, Liu H (2017) The effects of genre on DD and dependency direction. Lang Sci 59:135–147

Acknowledgements

The work was supported by the Major Program of National Fund of Philosophy and Social Science of China [24&ZD250].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Rui Wang conceptualized the study, performed the data analyses, and drafted the original manuscript. Qingshun He contributed to the revision and refinement of the manuscript. Both authors approved the final version of the paper and agreed to its publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was not required as the study did not involve human participants.

Informed consent

Ethical approval was not required as the study did not involve human participants.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, R., He, Q. A corpus-based dependency study of the correlation between nominal group complexity and clause complexity in English academic writing. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 13, 62 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-06360-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-06360-z