Abstract

Slovakia, like several other countries, has a highly fragmented system of local self-government. According to theoretical expectations, small municipalities with only a few hundred inhabitants often lack sufficient internal capacity to deliver local public services within their responsibilities (in-house production), especially when the services are complex and require specialised expertise. In cases when externalising service delivery (contracting out) fails, intermunicipal cooperation becomes a logical solution. Existing data suggest that intermunicipal cooperation may represent the lowest-cost delivery method for certain local public services. The goal of this paper is to identify the drivers and barriers of IMC in local public service delivery in Slovakia. Data were collected through a questionnaire survey and are used to document the extent to which intermunicipal cooperation is utilised, to compare associated costs, and to identify the drivers, barriers, and key benefits of intermunicipal cooperation in service delivery. Our findings suggest that economic and political-administrative barriers have a more substantial influence on intermunicipal cooperation decisions than legal-institutional constraints. While municipalities operate under similar external legal and administrative frameworks, it is their internal capacity, local political culture, and transaction cost-related considerations that most significantly distinguish cooperating from non-cooperating municipalities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Current research in the field of local public service delivery (Petersen, Hjelmar & Vrangbæk, 2018; Schoute, Budding & Gradus, 2018; Mikušová Meričková and Jakuš Muthová, 2021) shows contracting out (externalisation) as a frequent solution for delivering local services; however, it also points to the risks associated with contracting out. These risks are considerable, and in response to contracting-out failures, re-municipalisation is evident in many countries (Bel & Rosell, 2016; Soukopová & Klimovský, 2016; Albalate, Bel, & Reeves, 2019; Clifton, Warner, Gradus, & Bel, 2019). However, IMC and contracting out can be combined into a single “hybrid” form. For example, two or more municipalities may collaborate to contract out services to a private provider jointly, thereby combining elements of both IMC and privatisation. (Clifton, Warner, Gradus & Bel, 2019).

Intermunicipal cooperation (IMC) is one form of providing local public services.

Two or more local governments may jointly deliver one or more public services across their respective jurisdictions. It is typically used, mainly by small municipalities (Warner, 2006), because of its capacity to reduce local public unit production costs (Tavares & Feiock, 2018; Bel and Sebő, 2021). IMC may help to achieve economies of scale (Agranoff, 2004; Bel et al., 2013; Raudla & Tavares, 2018; Hefetz, Warner & Vigoda-Gadot, 2012) and improve the credit rating of municipalities (De Sousa, 2013).

The existence of economies of scale (U-curve) related to the delivery of many local public services in territorially fragmented countries has been confirmed, for example, by Soukopová and Vaceková (2018) in the Czech Republic, by Kaczyńska (2020) in Poland, by Blåka, Jacobsen, and Morken (2021) in Norway, Ferraresi et al. (2018) in Italy, Bel and Warner (2015) in Spain, and Wolfschütz (2020) in Germany.

Although most studies confirm the efficiency gains of IMC in terms of economies of scale, the described impacts of IMC on service quality are not entirely clear-cut. Bel and Warner (Bel and Warner, 2015) demonstrate in their study that IMC may improve the coordination of processes or increase the quality of services through risk sharing and expertise pooling (Bel & Warner, 2015). The results of Bel and Fageda’s studies are mixed and do not consistently show improved service quality from IMC (Bel & Fageda et al., 2013). Multi-principal governance in institutionalised IMC frequently leads to steering and monitoring breakdowns, reduced efficiency, and weakened accountability, thereby undermining IMC’s presumed service quality benefits (Spicer, 2017; Aldag, Warner & Bel, 2020). In cases where multiple municipalities share governance, a principal-agent problem arises, which can dilute accountability and monitoring and decrease service quality (Blåka, 2023, Elston, Bel, &Wang, 2025). Other challenges of IMC include diminishing returns (Giacomini, 2023) and perceived implementation deficits (Hilarión et al., 2024; Elston, Bel, & Wang, 2023).

Overcoming these IMC challenges depends on internal capacity and local political culture, which can act as political-administrative barriers to IMC. The ambiguity in the impact of IMC on service delivery efficiency may therefore be due to the existence of barriers to IMC. Exploring IMC barriers and drivers, therefore, makes an important contribution to explaining this ambiguity.

Regarding the country’s background, Slovakia was established in 1993 after the amicable split of the former Czechoslovakia. From the perspective of local democracy, Slovakia adheres to all the principles of the European Charter of Local Self-Government (see, for example, Plaček et al., 2020). The country’s population is approximately 5.5 million inhabitants, but it has nearly 2900 municipalities, meaning the territorial structure of Slovakia is highly fragmented, and many municipalities have fewer than 200 inhabitants. Despite the high level of fragmentation, the level of functional decentralisation is very high—Slovak municipalities independently manage a comprehensive set of their responsibilities and a large set of delegated responsibilities, executed on behalf of the state administration.

The academic literature (see above) suggests that IMC should be a frequent form of service delivery at the local level in fragmented countries, provided that the IMC challenges described above are effectively managed. However, data from Slovakia do not show such a pattern—IMC is rarely used, despite the fact that many small municipalities cannot deliver local public services via in house production, and that IMC seems to be cost-effective solution (the existing research suggests that IMC is the lowest costs option in Slovakia, as explained in the previous text). Therefore, the comprehensive explanation of the factors and determinants of IMC use is the core focus of our research, as well as the value added by it.

Are the IMC challenges connected with principal-agent problems, diminishing returns, and perceived implementation deficits the reason? Can these IMC challenges be explained by exploring IMC barriers and drivers? Exploring IMC barriers and drivers in Slovakia presents a challenge for academic research, as it aims to explain the ambiguity of IMC’s impact on the efficiency of service delivery, which is influenced by IMC challenges. This paper attempts to fill the research gap in this area.

The goal of this paper is to identify the drivers and barriers of IMC in local public service delivery in Slovakia. We focus on selected local services, including the collection and disposal of municipal solid waste, maintenance of local roads, upkeep of public green spaces, maintenance of public lighting, and cemetery services.

Our primary research question is: What are the drivers and barriers of IMC? Before answering this question, we provide the necessary background data related to the scale and efficiency of IMC. The main research method is the analysis of primary data gathered through our questionnaire.

The research builds on our previously published results related to intermunicipal cooperation in Slovakia (Nemec et al., 2023), using a new research sample and aiming to provide a more comprehensive picture.

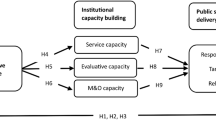

Our article is important both for the theory and real public policy. In terms of theory, it contextualises knowledge in the field of public policy related to IMC, which has not yet been sufficiently investigated in the Central and Eastern European (CEE) context. We also develop an institutional collective action framework (Tavares and Feiock, 2018) that emphasises the importance of different institutional contexts influencing the adoption and outcomes of intermunicipal cooperation. From a practical public policy perspective, we map the current state of intermunicipal cooperation in Slovakia and identify the main drivers and barriers to cooperation arising from the country’s institutional context.

Theoretical background and conceptualisation of research questions

IMC is a flexible model that allows municipalities to efficiently provide various public services. Instead of a full merger, municipalities agree on the joint provision of selected services to achieve economies of scale and streamline processes. Municipalities retain their independence and jointly manage only those areas where it’s beneficial (for example, waste collection, public transport, or water supply systems). This form of cooperation serves as a partial amalgamation, where selected responsibilities from several municipalities are merged into a single joint venture. This allows both small and large local governments to provide high-quality services that would be too costly or logistically challenging for them to provide on their own (Elston, Bel, &Wang, 2025).

IMC can be broadly defined as a relationship based on mutual understanding and partnership (see, for example, Hulst & Van Montfort, 2007; or Koolma, Hulst & Van Montfort, 2017). IMC has the potential to contribute to territorial development and improve both the cost-efficiency and quality of public services provided (Jetmar, 2015). It is expected that smaller municipalities will show a greater inclination toward intermunicipal cooperation due to their limited human and administrative capacities. Moreover, voluntary intermunicipal cooperation represents a viable alternative to the top-down mergers of municipalities (Hertzog, 2010).

IMC aims to enhance expertise while simultaneously increasing the efficiency of the performance of both original and delegated competences within local self-government (Silvestre et al., 2020). The types of IMC agreements may differ significantly, particularly in terms of content and level of institutionalisation, depending on the specific conditions of each country. It is possible to distinguish different types of IMC based on the type of collaboration, form of commitment, management complexity, representation, and the degree of institutionalisation (Ferreira, Dijkstra, Aniche & Scholten, 2020). Swianiewicz and Teles (2019) define several levels of IMC, as shown in Table 1.

As already indicated, IMC is expected to bring about improvements in both the cost-efficiency and quality of the delivery of local public services (as well as administrative services provided as delegated responsibilities), primarily due to economies of scale. Alongside other forms of externalisation, IMC serves as a solution to the limited human and administrative capacities of small municipalities. Territorial units with a smaller population generally serve fewer residents and therefore have fewer opportunities to scale service delivery effectively.

The main economic argument related to IMC—the existence or non-existence of economies of scale in the delivery of local public services—has been investigated by dozens, if not hundreds, of academic articles. Under region-specific conditions, for example, Matějová et al. (2017) found that cost curves have different shapes for different local services and functions, each with different minimum points, and that not all local public services and functions are associated with economies of scale. Another study by Soukopová & Klimovský (2016) found that, in the case of waste management services, IMC and population density are significant independent variables influencing municipal waste disposal costs (with more than 99% confidence), which suggests that, in their sample, IMC contributed to reducing overall waste disposal costs. Similar results for a broader scope of services were reported by Swianiewicz & Teles (2019). At the global level, related findings are presented in the studies by Niaounakis & Blank (2017), Bel et al. (2013), and Agrawal, Breuillé & Le Gallo (2021).

Many studies also investigate the reasons municipalities choose to cooperate. West (2007) analysed French municipalities (in a fragmented system with potential scale limitations at the municipal level). In France, collaborative arrangements are frequently established voluntarily to deliver public services. Fedele & Moini (2007) examined the situation in Italy and described various forms of IMC, including both voluntary agreements and mandatory cooperation arrangements. Haveri & Airaksinen (2007) evaluated IMC arrangements in Finland.

Numerous authors have explicitly focused on the factors that influence intermunicipal cooperation, both its drivers and barriers. Bel & Sebő (2021), Lowery (2000), and Warner & Hefetz (2002) similarly categorise these factors into two main groups: cost and fiscal factors and willingness to cooperate. Feiock (2007) concludes that homogeneity in services (e.g., quality, availability, and range), availability of resources, and institutional arrangements create favourable conditions for the emergence of IMC. Brown, Potoski & Slyke (2016) identify additional factors, such as the professionalism of municipal management and the quality of risk management. According to Goodman (2015), the main determinants for establishing IMC between municipalities are territorial, financial, personnel, and development-related factors.

We begin our conceptualisation with the approach of, who use historical, cultural, and institutional differences to explain variations in IMC between Eastern and Western Europe, as well as between Northern and Southern European countries. Conclude that Europe is characterised by a more formal, contract-based, and hierarchical approach to IMC compared to, for example, the United States. Additionally, a high degree of heterogeneity in preferences is considered typical for Europe.

Nemec et al. (2024) argue that a more nuanced approach is needed when analysing countries in Central and Eastern Europe. They identify specific differences in the cases of the Czech Republic, Slovakia, and Poland, evaluating all three countries in terms of their institutional environment, collaborative regime, and collaborative action. The authors conclude that Poland is more open to collaboration due to its institutional context and legislative framework, while Slovakia’s institutional environment is described as unfriendly, unstable, and corrupt. The collaborative regimes in Slovakia are characterised as formal, rigid, and non-transparent, and collaborative action is described as constrained, ineffective, and dependent.

Among other barriers to potential collaboration, Nemec et al. (2024) mention a zero-tolerance-for-error condition, in which the public administration system is primarily focused on identifying and punishing mistakes rather than incentivising creative problem-solving. The authors also underline the importance of trust between actors in cooperation processes, noting that such trust is significantly lacking in the Slovak context.

At this point, we begin to conceptualise our assumptions, which we aim to test within the framework of our paper.

Based on the current state of knowledge, we divide the drivers and barriers of IMC as follows:

-

Economic drivers

-

Non-economic drivers

-

Political-administrative barriers: differing political orientations of municipalities; bureaucratic systems resistant to change (Feiock, 2007; Tavares & Feiock, 2018; Brown, Potoski & Slyke, 2016; Goodman, 2015).

-

Legal-institutional barriers: restrictive legislative frameworks; state policies that (do not) support IMC (Goodman, 2015; Feiock, 2007).

-

Economic barriers: high transaction costs of cooperation; unequal availability of capital and human resources (Bel & Sebő, 2021; Lowery, 2000; Warner & Hefetz, 2002; Feiock, 2007; Goodman, 2015).

We also formulate the following research questions:

RQ1: What is the scale of the IMC in local public service delivery in Slovakia?

RQ2: What are the main drivers and barriers to the IMC in delivering local public services in Slovakia?

The first research question is answered in the “background” part. The second research question is the core one, and it is answered in the core analytical part of the paper.

Materials and methods

The goal of this paper is to identify the drivers and barriers of IMC in local public service delivery in Slovakia. In our research, we focused on selected local services—specifically, the collection and disposal of municipal solid waste, maintenance of local roads, upkeep of public green spaces, maintenance of public lighting, and cemetery management services. The selection of services was based on two main criteria: first, we aimed to include classic communal services; second, we wanted to cover services with varying cost intensities, ranging from waste management, which is typically the most expensive local service, to cemetery management, which is considered a low-cost service.

To answer our research questions (regarding the scale, drivers, and barriers of IMC in local public service delivery in Slovakia), we used the method of primary data analysis based on our original questionnaire.

The design of the questionnaire was informed by previous surveys and research, particularly those conducted by the Association of Towns and Municipalities of Slovakia (Beresecká et al., 2020), Mikušová Meričková et al. (2021), Nemec et al. (2023), as well as other studies by Bel & Sebő (2021), Lowery (2000), Warner & Hefetz (2002), Feiock (2007), Brown, Potoski & Slyke (2016), and Goodman (2015).

The questionnaire was distributed electronically to all local governments and municipal districts in Slovakia between March and April 2024. In total, 2,927 local authorities from all regions of the Slovak Republic were contacted, and 183 local authorities participated in the survey (see Table 2).

We tested the representativeness of our sample using a Chi-square test (see Table 2). In our case, the sample is not representative, as the structure of the population—i.e. all municipalities in Slovakia—in terms of population size, administrative status, and regional distribution, does not fully correspond to the structure of our sample. However, the results are broadly representative of small municipalities and can therefore be applied analytically only within this segment. In the wider context of IMC, they should be regarded as illustrative rather than as a basis for broader generalization.

In examining the scale of IMC, we use a simple measure, the percentage of local public services delivered through IMC.

To assess the differences between cooperating and non-cooperating municipalities, we applied the Mann–Whitney U test because the Shapiro-Wilk test indicated that not all variables were normally distributed (p-values for some variables were smaller than 0.05, indicating that these variables do not meet the assumption of normality). The Mann-Whitney U test does not require the assumption of normality. It is therefore suitable for comparing two independent groups when the data are unevenly distributed or not normally distributed (Table 3).

The research design employs a comparative cross-sectional approach, contrasting municipalities engaged in IMC with those that are not. The underlying logic of inference is that systematic differences in how these groups perceive specific drivers and barriers can reveal the enabling or constraining factors that influence the adoption of IMC. By statistically assessing these differences, we aim to identify which factors truly distinguish cooperative behaviour, thereby providing explanatory leverage over the uneven uptake of IMC reform.

Results and discussion

Background: the scale of IMC in Slovakia

The first research question addressed the scale of IMC in the delivery of local public services in Slovakia. Table 4 presents the findings related to the scale of IMC.

The data show that the IMC option for service delivery is not frequently utilised. Considering the near non-existence of IMC in the delivery of most local services, we decided to conduct efficiency comparisons only for waste management services. Waste management is one of the most commonly managed services within IMC, as confirmed by several studies (Beresecká et al., 2020; Aldag, Warner, & Bel, 2020; Bel & Sebő, 2021; Soukopová & Klimovský, 2016) (Table 5).

Drivers and barriers to IMC in delivering local public services in Slovakia

The level of IMC among the surveyed municipalities is relatively low. In the questionnaire on barriers and drivers, municipalities assessed each driver on a five-point scale, where 1 represented a very strong driver of IMC and 5 represented a very weak one. In the questionnaire, the drivers and barriers were not pre-categorised in order to avoid guiding the respondents’ answers. In the following tables, the drivers are categorised—based on the findings of the literature review—into economic drivers (Table 6) and non-economic drivers (Table 7). The results were processed only for the service of municipal solid waste collection and disposal, where the number of responses was sufficient to allow further analysis.

Overall, the results indicate that while non-economic factors may not be the primary motivators for engaging in IMC, they are non-negligible supporting elements that can reinforce or enable cooperation, particularly in services such as waste management. Tables 6–8 present the opinions of municipalities regarding the main barriers limiting the use of IMC in the delivery of local public services. To assess the differences between cooperating and non-cooperating municipalities, we applied the Mann–Whitney U test.

The results of the Mann-Whitney U test indicate that several economic barriers to IMC are perceived significantly differently by cooperating and non-cooperating municipalities in the area of municipal waste collection and disposal. Municipalities that do not engage in cooperation reported higher perceived severity for most economic barriers. In particular:

-

Lack of finance (transaction costs related to IMC management) was rated significantly higher by non-cooperating municipalities (Mean Rank = 53.83) than by cooperating ones (Mean Rank = 89.97), U = 285.500, p < 0.001.

-

Similarly, Lack of willingness to cooperate with smaller municipalities (U = 339.500, p = 0.003) and management and coordination costs (U = 423.500, p = 0.026) were perceived as more limiting by the non-cooperating group.

Significant differences were also observed for barriers, including decreased flexibility in service delivery (p < 0.001), Information asymmetry (p = 0.030), Difficulty in sharing responsibilities (p < 0.001), Difficulty in coordination (p < 0.001), and Losing control over services (p = 0.002).

On the contrary, Lack of personnel was not perceived significantly differently between the two groups (p = 0.207), suggesting that human resource limitations may be a universal issue. Although decreased transparency showed a significant p-value (p < 0.001), the mean ranks were very close between the two groups (54.21 vs. 56.46), indicating a minimal practical difference.

The Mann-Whitney U test revealed statistically significant differences in how legal-administrative barriers are perceived by cooperating and non-cooperating municipalities. Given the response scale, where lower values indicate stronger agreement that a factor is a barrier, lower mean ranks correspond to a higher perceived severity. Non-cooperating municipalities consistently assigned lower ranks to several political barriers, suggesting they view these factors as more significant obstacles to cooperation. Specifically:

-

General lack of willingness to cooperate—linked to bureaucratic functioning was perceived more strongly by non-cooperating municipalities (Mean Rank = 51.56) than by cooperating ones (Mean Rank = 80.43), U = 338.500, p = 0.001.

-

Efforts to protect municipal autonomy also differed significantly (U = 290.000, p < 0.001).

Significant differences were also found for Different political orientations among neighbouring municipalities (p < 0.001), Personal aversion of the mayor (p < 0.001), General political reasons (p = 0.006), Low level of social capital of the mayor (p < 0.001), Diverging stakeholder values (p = 0.021).

One barrier, resistance from employees, approached significance (p = 0.052) and may warrant further investigation.

These results suggest that political leadership, ideological alignment, and personal or stakeholder-level dynamics play a substantial role in shaping the willingness or ability of municipalities to engage in IMC.

Compared to the two previous tables, no statistically significant differences were found between cooperating and non-cooperating municipalities in their perception of legal-institutional barriers: Limited state support (p = 0.794) and Political instability (p = 0.673) were rated similarly by both groups, with very close mean ranks. The above suggests that these systemic issues are perceived uniformly, regardless of whether a municipality is engaged in cooperation or not. It may indicate that administrative and legal conditions are considered external and equally limiting for all municipalities, without necessarily affecting the decision to cooperate.

Discussion and conclusions

Our results indicate that IMC is rarely used as the form of delivery of local public services in Slovakia; it is somehow visible in the service collection and disposal of MSW in Slovakia in the area of waste management (all existing studies, like Bel et al., 2013 or Soukopová and Klimovský, 2016 on the regional level delivered similar results). Bel et al. (2013) also found that IMC is most often adopted in high-cost, high-volume services, such as solid waste collection.

The primary focus of our paper was to identify the factors and barriers associated with the IMC. The comparative analysis reveals distinct patterns in how municipalities perceive various categories of factors that influence IMC. Our research identified key economic drivers, including economies of scale, technical efficiency, and lower production costs for services. These findings are also consistent with Ferraresi et al. (2018) and Struk and Bakoš (2021). Additionally, non-economic factors, including social aspects such as job creation and shared municipal values, were identified, like those in the research of Arntsen, Torjesen, and Karlsen (2018).

Economic factors are considered the most advantageous. However, they simultaneously emerge as the primary obstacles for non-cooperating municipalities, revealing a notable paradox: what serves as a strong motivator for some is perceived as a limitation by others, particularly in terms of transaction costs, coordination difficulties, and disparities in available resources. The above aligns directly with Bel & Warner (2015), who argue that while economies of scale are attractive, transaction costs, asymmetric capacities, and governance complexity often negate efficiency gains. These results suggest that municipalities, in their responses (barriers), focused on direct, immediate IMC costs and did not take into account future savings.

Our research outcomes, which address IMC barriers, particularly economic constraints such as a lack of finance and coordination costs, align with the analysis by Bel and Warner (2015). They emphasised that fiscal stress and organisational factors are significant barriers to IMC. The paradoxical role of economic factors as both drivers and barriers also reflects fragmented trust and asymmetric resource capacity, which hinders the collaborative cycle.

Non-economic factors, such as social capital, shared values, and trust, are generally seen as beneficial, as emphasised by Ansell and Gash (2008), albeit to a slightly lesser extent than economic factors, as confirmed by our outcomes. Nevertheless, certain non-economic elements—particularly those involving unwillingness to cooperate, local leadership, and value alignment—also appear as barriers, especially in contexts marked by political tensions or interpersonal conflicts. This reluctance to cooperate is a barrier that aligns with Bel’s broader European findings, especially in contexts where local leadership and trust are fragmented (Clifton et al., 2019).

Legal-institutional barriers, including the current legal framework and decentralisation arrangements, are perceived as neutral to moderately positive. Notably, no statistically significant differences were found between cooperating and non-cooperating municipalities in their assessment of these factors, suggesting they are not decisive in shaping the choice to pursue IMC.

Political-administrative challenges were identified as hindering cooperation in our research, including efforts to safeguard municipal autonomy and the varying political orientations of municipal officials. The above aligns with Allers and de Greef (2018), who noted that while IMC is often pursued for efficiency gains, it does not always result in reduced public spending, suggesting that political dynamics and governance structures play a crucial role. Our results suggest that the most significant barrier to IMC is the reluctance to cooperate, stemming from various institutional and subjective reasons. Our study illustrates a breakdown in the collaborative dynamics outlined by Emerson, Nabatchi & Balogh (2012). Even though drivers exist, the capacity for joint action is constrained by poor engagement and low shared motivation. Moreover, political-administrative fragmentation undermines the emergence of sustainable collaborative governance. This opinion aligns with the findings of similar research in Slovakia, as presented by Solej (2023). Bel et al. (2024) explicitly discuss how IMC effectiveness depends on structural incentives and shared motivation, trust, and leadership.

A potentially positive fact is that we have noted the expressed interest in initiating inter-municipal cooperation on the part of the municipalities. In response to one of our questions, 64.3% of municipalities expressed interest in initiating inter-municipal cooperation, particularly in areas such as road maintenance, waste collection, removal, and disposal, as well as joint public procurement and public utility activities. Based on this, we may argue that there is an interest in inter-municipal cooperation in the field of waste management in the Slovak Republic, at least in a formal sense, reflecting the advantages of this approach.

Research limitations

The policy lesson is obvious—both top-down (from the central level) and horizontal interests for the IMC should be promoted by any means. On the state’s side, continuous and orderly assistance to local governments in inter-municipal cooperation, coordination, legal support, and technical support is needed. The systemic solution is to enhance the quality of democracy, specifically local democracy, which should lead to a significantly higher level of accountability and responsibility (Veselý, 2013). The institutional structures and economic incentives are necessary, but they are not sufficient. The key enablers of successful IMC—trust, shared leadership, political alignment, and joint capacity—are often absent or fragmented (Emerson, Nabatchi & Balogh, 2012; Ansell & Gash, 2008). The above underscores the centrality of collaborative readiness and normative alignment in making IMC viable.

The study reveals that while IMC in Slovakia is rarely used, it is usually implemented in the case of waste management, as confirmed by previous international findings. Economic drivers, such as economies of scale and technical efficiency, are strong motivators; yet paradoxically, they also emerge as key barriers due to concerns over coordination, transaction costs, and unequal resource allocation. Political-administrative challenges, including reluctance to cooperate and political misalignment, further hinder collaboration. These findings support collaborative governance theories, highlighting that trust, shared motivation, and leadership are critical for successful IMC—factors currently lacking in the Slovak context.

Future research should broaden its scope beyond waste services to assess IMC effectiveness across various service areas and adopt longitudinal or case study methods to understand cooperation dynamics over time better. There is also a need to explore the role of facilitative leadership, social capital, and behavioural factors in shaping IMC outcomes. Comparative studies across Central and Eastern Europe could reveal institutional best practices. At the same time, closer examination of legal frameworks and targeted policy tools could help activate the expressed interest in cooperation among municipalities.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Agranoff R (2004) Collaborative public management: New strategies for local governments. 1st ed. Georgetown: University Press

Agrawal RD, Breuillé M–L, Le Gallo J (2021) ‘Tax competition with intermunicipal cooperation‘. SSRN 45(3):p454–p485. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3560611

Albalate D, Bel G, Reeves E (2019) ‘Easier said than done: Understanding the implementation of re-municipalization decisions and associated delays.‘ Institut de Recerca en Economia Aplicada Regional i Pública, Working Papers, 2019, IR19/17, p1-31

Aldag RJ, Warner ME, Bel G (2020) It depends on what you share: the elusive cost savings from service sharing. J Public Adm Res Theory 30(2):275–289

Allers MA, de Greef JA (2018) Intermunicipal cooperation, public spending and service levels. Local Gov. Stud. 44(1):127–150. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2017.1380630

Ansell C, Gash A (2008) Collaborative governance in theory and practice. J Public Adm Res Theory 18(4):543–571. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/mum032

Arntsen B, Torjesen DO, Karlsen T-I (2018) Drivers and barriers of inter-municipal cooperation in health services—The Norwegian case. Local Gov Stud 44(3):371–390. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2018.1427071

Bel G, Warner ME (2015) Inter-municipal cooperation and costs: expectations and evidence. Public Adm 93(1):52–67. https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12104

Bel G, Rosell J (2016) Public and private production in a mixed delivery system: regulation, competition and costs. J Policy Anal Manag 35(3):p533–p558. https://doi.org/10.1002/pam.21906

Bel G, Sebő M (2021) Does inter-municipal cooperation really reduce delivery costs? An empirical evaluation of the role of scale economies, transaction costs, and governance arrangements. Urban Aff Rev 57(1):153–188. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078087419839492

Bel G, Fageda X, Mur M (2013) Why do municipalities cooperate to provide local public services? An empirical analysis. Local Gov Stud 39(3):435–454. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2013.781024

Bel G, Elston T, Esteve M, Petersen OH (2024) Local government reform beyond privatization and amalgamation: Advances in the analysis of inter-municipal cooperation. J Economic Policy Reform 27(2):125–139. https://doi.org/10.1080/17487870.2022.2041416

Beresecká J, Hronec Š, Ikrényiová K, Kárpáty P, Mihályi G, Škrdlová K, Slavík V (2020) Efektivita a výkonnosť súčasného stavu medziobecnej spolupráce na úrovni vnútroštátnych a prihraničných regiónov. Bratislava. https://npmodmus.zmos.sk/download_file_f.php?id=1274479

Blåka S (2023) Service quality and the optimum number of members in intermunicipal cooperation: The case of emergency primary care services in Norway. Public Administration. https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12785

Blåka S, Jacobsen DI, Morken T (2021) Service quality and the optimum number of members in intermunicipal cooperation: The case of emergency primary care services in Norway. Public Administration, 1 (16). https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12785

Brown TL, Potoski M, Slyke D (2016) Managing complex contracts: a theoretical approach. J Public Adm Res Theory 26(2):p294–p308. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/muv004

Clifton J, Warner EM, Gradus R, Bel G (2019) Re-municipalization of public services: trend or hype. J Econ Policy Reform 24(3):p293–p304. https://doi.org/10.1080/17487870.2019.1691344

Elston T, Bel G, Wang H (2025) The effect of inter-municipal cooperation on social assistance programs: Evidence from housing allowances in England. J Policy Anal Manag 44(3):1060–1088. https://doi.org/10.1002/pam.22664

Elston T, Bel G, Wang H (2023) If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it: When collaborative public management becomes collaborative excess. Public Adm. Rev 83(6):1737–1760. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.13708

Emerson K, Nabatchi T, Balogh S (2012) An integrative framework for collaborative governance. J Public Adm Res Theory 22(1):1–29. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/mur011

Fedele M, Moini G (2007) Italy: the changing boundaries of inter-municipal cooperation. In Hulst, R and Montfort, A (eds). Inter-Municipal Cooperation in Europe. Dordrecht: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/1-4020-5379-7_6

Feiock RC (2007) Rational choice and regional governance. J Urban Aff 29(1):47–63

Ferraresi M, Migali G, Rizzo L (2018) Does intermunicipal cooperation promote efficiency gains? Evidence from Italian Municipal Unions. J Reg Sci 58(5):1017–1044. https://doi.org/10.1111/jors.12388

Ferreira MEV, Dijkstra AE, Aniche LQ, Scholten P (2020) Towards a typology of inter-municipal cooperation in emerging metropolitan regions. A case study in the solid waste management sector in Ecuador. Cogent Soc Sci 6(1):p1–p20. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2020.1757185

Giacomini D (2023) Factors explaining inter-municipal cooperation in service delivery: a meta-regression analysis. [Research report]. ResearchGate. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/283850854

Goodman CHB (2015) Local government fragmentation and the local public sector. Public Financ Rev 43(1):p82–p107

Haveri A, Airaksinen J (2007) Inter-Municipal Cooperation in Finland: Old Traditions and New Promises. In Hulst, R and Montfort, A (eds). Inter-Municipal Cooperation in Europe. Dordrecht: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/1-4020-5379-7_3

Hefetz A, Warner ME, Vigoda-Gadot E (2012) Privatization and intermunicipal contracting: The US local government experience 1992–2007. Environ Plan C: Gov Policy 30(4):p675–p692. https://doi.org/10.1068/c11166

Hertzog R (2010) Intermunicipal Cooperation: A Viable Alternative to Territorial Amalgamation? In Swianiewicz, P (ed.). Territorial Consolidation Reforms in Europe. Budapest: LGI—Open Society Institute, 289—312

Hilarión P, Vila A, Contel JC, Ferré-Grau C, López J, Farré J (2024) Integrated health and social home care services in Catalonia: Professionals’ perception of implementation and main barriers. Int J Integr Care 24(1):1–11. https://doi.org/10.5334/ijic.7530

Hulst R, Van Montfort A (2007) Inter-Municipal Cooperation in Europe. Dordrecht: Springer Dordrecht

Jetmar J (2015) Meziobecní spolupráce, inspirativní cesta, jak zlepšit služby veřejnosti. Praha: Svaz měst a obcí České republiky

Kaczyńska A (2020) Inter-municipal cooperation in education as a possible remedy for current difficulties of local government in Poland. Acta Universitatis Lodziensis Folia Oeconomica 5(350):101–125. https://doi.org/10.18778/0208-6018.350.06

Koolma HM, Hulst RJ, Van Montfort AJGM (2017) Are larger organizations more efficient and strategically stronger? A crosssectional and longitudinal research into Dutch housing corporations. Archives Business Res 5(12):p126–p147. https://doi.org/10.14738/abr.512.3988

Lowery D (2000) A transactions costs model of metropolitan governance: allocation versus redistribution in urban America. J Public Adm Res Theory 10(1):p49–p78

Matějová L et al. (2017) Economies of scale on the municipal level: fact or fiction in the Czech Republic?. NISPAcee J Public Adm Policy 10(1):p39–p59. https://doi.org/10.1515/nispa-2017-0002

Mikušová Meričková B, Jakuš Muthová N (2021) Innovative Concept of Providing Local Public Services Based on ICT. NISPAcee J Public Adm Policy 14(1):p135–p167. https://doi.org/10.2478/nispa-2021-0006

Nemec J, Jakuš Muthová N, Mikušová Meričková B (2023) Barriers to inter-municipal cooperation. Administratie si Manag Public 41:125–144. https://doi.org/10.24818/amp/2023.41-07

Nemec J, Reddy P, Plaček M (2024) Conflict and public administration performance: CEE Countries. J Comp Policy Anal: Res Pract 26(2):196–214. UT-WOS link

Niaounakis T, Blank J (2017) Inter-municipal cooperation, economies of scale and cost efficiency: an application of stochastic frontier analysis to Dutch municipal tax departments. Local Gov Stud 43(4):p533–p554. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2017.1322958

Petersen OH, Hjelmar U, Vrangbæk K (2018) Is Contracting out of Public Services still the Great Panacea? A Systematic Review of Studies on Economic and Quality Effects from 2000 to 2014. Soc Policy Adm 52(1):p130–p157. https://doi.org/10.1111/spol.12297

Plaček M, Ochrana F, Puček MJ, Nemec J (2020) Fiscal Decentralization reforms: the impact on the efficiency of local governments in Central and Eastern Europe. Springer: Cham

Raudla R, Tavares AF (2018) Inter-municipal Cooperation and Austerity Policies: Obstacles or Opportunities? In Teles, F, Swianiewicz, P (ed.) Inter-Municipal Cooperation in Europe, Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 17—41

Schoute M, Budding T, Gradus R (2018) ‘Municipalities’ Choices of Service Delivery Modes: The Influence of Service, Political, Governance, and Financial Characteristics.‘ International Public Managment. Journal 21(4):p502–p532. https://doi.org/10.1080/10967494.2017.1297337

Silvestre CH (2020) Is cooperation cost reducing? An analysis of public–public partnerships and inter-municipal cooperation in Brazilian local government. Local Gov Stud 46(1):p68–p90. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2019.1615462

Solej R (2023) Fragmentation and consolidation reform in Slovakia. Acta Academica Karviniensia 23(1):94–105. ISSN 1212-415X

Soukopová J, Klimovský D (2016) Intermunicipal cooperation and local cost efficiency: the case of waste management services in the Czech Republic. 20th Int Conf Curr Trends Public Sect Res 2016(1):1–8

Soukopová J, Vaceková G (2018) Internal Factors of Intermunicipal Cooperation: What Matters Most and Why?. Local Gov Stud 44(1):105–126. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2017.1395739

De Sousa L (2013) Understanding European cross-border cooperation: a framework for analysis. J Eur Integr 35(6):p669–p687. https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2012.711827

Spicer Z (2017) Bridging the accountability and transparency gap in inter-municipal collaboration. Local Gov Stud 43(5):681–701. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2017.1356723

Struk M, Bakoš E (2021) Long-term benefits of intermunicipal cooperation for small municipalities in waste management provision. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18(4):1449. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18041449

Swianiewicz P, Teles F (2019) Inter-municipal cooperation in Europe, 1st edn. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan

Tavares A, Feiock R (2018) ‘Applying an Institutional Collective Action Framework to Investigate Intermunicipal Cooperation in Europe. Perspect Public Manag Gov Forthcom ‘ Perspect Public Manag Gov 1(4):p299–p316. https://doi.org/10.1093/ppmgov/gvx014

Veselý A (2013) Accountability in Central and Eastern Europe: concept and reality. Int Rev Adm Sci 79:310–330

Warner ME (2006) Inter-municipal Cooperation in the U.S.A. Regional Governance Solution?. Urban Public Econ Rev 6(1):p221–p239

Warner ME, Hefetz A (2002) Applying market solutions to public services: an assessment of efficiency, Equity and Voice. Urban Aff Rev 38(1):p70–p89

West K (2007) Inter-Municipal Cooperation in France: Incentives, Instrumentality and Empty Shells. In: Hulst, R, Montfort, AV (eds) Inter-Municipal Cooperation in Europe. Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/1-4020-5379-7_4

Wolfschütz E (2020) The Effect of Inter-Municipal Cooperation on Local Business Development in German Municipalities. MAGKS Joint Discussion Paper Series in Economics No 05-2020. https://www.uni-marburg.de/fb02/makro/forschung/magkspapers/paper_2020/05-2020_wolfschuetz.pdf

Acknowledgements

The work was supported by research project VEGA 1/0003/24 Inter-municipal cooperation in providing local public services.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Beata Mikusova Merickova: Writing—review & editing, Writing—original draft, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Resources, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Nikoleta Jakus Muthova: Writing—review & editing, Writing—original draft, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Resources, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Juraj Nemec: Writing—review & editing, Writing—original draft, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Resources, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Michal Placek: Writing—review & editing, Writing—original draft, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Resources, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study received retrospective ethical approval from the Ethics Committee of Matej Bel University (ID number: 314/2025; approved in April 2025). At the time when the original research was conducted, and still today, there has been no national legal requirement in Slovakia for ethical approval of anonymous, voluntary, and non-sensitive surveys in the social sciences that do not involve medical or psychological interventions. According to Act No. 576/2004 Coll. on Health Care, ethical approval is required only for clinical trials and biomedical research on humans. Nevertheless, the study adhered to the ethical standards outlined in the Ethical Code of Matej Bel University (revised in 2023) and complied with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (2013 revision) and the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). Retrospective ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of Matej Bel University (ID number: 314/2025; approved in April 2025).

Informed consent

All participants provided informed consent prior to taking part in the study. Participation was entirely voluntary, anonymous, and could be withdrawn at any time without any consequences. The informed consent statement was included as part of the questionnaire completed by respondents. Informed consent was obtained from the respondents at the time of completing the questionnaire, between March and April 2024. By submitting the questionnaire, participants confirmed their consent to participate in the study and to the processing of their data for scientific and academic research purposes only. Respondents were informed about the purpose of the research, the expected duration of participation, and the intended use of the data. No personal or identifying information was collected, and all responses were treated confidentially in accordance with the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and applicable national data protection legislation. As the research involved a non-interventional, non-sensitive organizational survey with adult participants, no additional consent from legal guardians or proxies was required.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mikušová Meričková, B., Jakuš Muthová, N., Nemec, J. et al. Drivers and barriers of intermunicipal cooperation in local service delivery. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 13, 75 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-06367-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-06367-6