Abstract

The present study focuses on the comprehensive role of the affective and cognitive consequences of ostracism and, in turn, on antisocial behavioral response toward the sources of ostracism. One hundred and sixty-eight participants were ostracized or included in Cyberball. Participants subsequently reported their own need satisfaction, mood, global impression of sources, and how they wanted to allocate money towards them. Results revealed that ostracized people (vs included) tend to allocate less money toward the sources as a form of coping strategy with the negative impact of ostracism. This behavior stems from the threat to the satisfaction of one’s needs and the negative mood that drives the formation of a negative impression towards the sources. Consistent with the “Temporal Need-Threat Model”, these findings advance knowledge about the cognitive and affective processes underlying the negative behavior of ostracized people.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ostracism, excluding or ignoring an individual or group, is rooted in human and social dynamics. Its impact on individuals’ social and psychological well-being has been the target of extensive research in contemporary psychology. Socrates, a key figure in ancient thought, stressed the importance of social connection for personal well-being, prefiguring modern concepts of ostracism. While he did not use the term “need for belonging,” his ideas laid the groundwork.

Psychological research has corroborated Socrates’ insights, demonstrating that ostracism can have negative effects on individuals’ mental health. In this regard, studies have shown that being ostracized activates similar neural pathways as physical pain, underscoring the severe emotional distress caused by ostracism (Eisenberger et al. 2003). It can lead to a cascade of adverse outcomes, including depression, anxiety, and decreased self-esteem (Williams 2009; Paolini 2019; for a meta-analysis, see Hartgerink et al. 2015). Furthermore, ostracism can disrupt psychological needs according to Self-Determination Theory (Deci and Ryan 2000). The threat to these needs can impair cognitive functioning, diminish motivation, and reduce overall life satisfaction (Baumeister and Leary 1995). In addition to the psychological impact, ostracism has significant social consequences. People respond to ostracism with behaviors that can be classified as prosocial, antisocial, or withdrawal (for a review, see Kip et al. 2025). Ostracized people cognitively evaluate the event, which leads them to undertake behaviors aimed at fortifying the basic needs threatened during ostracism (Needs Fortification Hypothesis, Williams 2009). Therefore, they may increase aggression and antisocial behavior (i.e., punishing the sources) as individuals attempt to regain a sense of control and significance (Carter-Sowell et al. 2008; Lakin et al. 2008; Riva et al. 2014; Twenge et al. 2001). At the same time, to enhance their self-image and promote social acceptance, ostracized individuals may also display prosocial behaviors such as compliance, conformity, and obedience (Chow et al. 2008; Lelieveld et al. 2013; Ren et al. 2018; Tedeschi 2001). Finally, the experience of ostracism can initiate a self-perpetuating cycle, whereby ostracized individuals become more likely to withdraw socially, further reinforcing their isolation (i.e., solitude-seeking; Ren et al. 2016).

Most of the studies mentioned above—particularly those employing physiological or neural measures—support the existence of a “primitive” system for detecting ostracism (Haselton and Buss 2000; Kerr and Levine 2008; Spoor and Williams 2007; Williams and Zadro 2005), characterized by immediate negative effects. This system corresponds to the Reflexive Stage of the Temporal Need-Threat Model (TNTM; Williams 2009), which is driven by threats to the satisfaction of basic needs—namely, belongingness, self-esteem, control, and meaningful existence (Williams 2009; Zadro et al. 2004). This initial reaction reverberates at the neurophysiological level, activating pain-related neural pathways such as the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex, the anterior insula, and the right ventral prefrontal cortex (Eisenberger et al. 2003). It also involves autonomic nervous system (ANS) activity (Ijzerman and Semin 2009; Ijzerman et al. 2012; Paolini et al. 2016; Sleegers et al. 2015), further confirming a state of intense distress. According to Williams (2009), responses at this stage are automatic and universal, unaffected by moderating variables or individual differences such as gender or social categorization (van Beest and Williams 2006). However, more recent findings challenge this assumption. A meta-analysis by Hartgerink et al. (2015) suggests that certain moderators may, in fact, influence individuals’ reflexive reactions to ostracism. For instance, individuals less prone to experiencing social pain—such as those with schizotypal personality traits—or participants under the influence of particular medications may show reduced susceptibility to ostracism, thereby attenuating its initial impact. Nonetheless, Hartgerink and colleagues caution that this conclusion is limited by methodological considerations: many measures classified as “first reactions” in the meta-analysis may not fully capture reflexive responses as defined by Williams (i.e., physiological, online, or immediate reports). Moreover, Williams’s assumption specifically concerns fundamental needs, and indeed, analyses restricted to immediate and delayed fundamental need satisfaction were consistent with the model’s predictions.

According to TNTM, after the immediate reflexive response, individuals quickly begin to interpret the experience of ostracism. They consider whether the episode warrants attention and the investment of cognitive resources (e.g., Paolini et al. 2020; Xu et al. 2017, 2020) and reflect on how to act to restore threatened needs. This phase, termed the Reflective Stage, can be modulated by stable individual differences that shape the selection of coping strategies (Williams 2009). For instance, Oaten et al. (2008) examined the role of social anxiety in moderating self-regulatory abilities following inclusion or ostracism. They found that while ostracism initially impaired self-regulation for all participants, only those high in social anxiety continued to show deficits over time. Beyond individual differences, situational contexts also play a role in recovery from ostracism. Evidence suggests, for example, that recovery is quicker and more complete when exclusion comes from out-group rather than in-group members (Goodwin et al. 2010; Wirth and Williams 2009). Taken together, these findings indicate that during the Reflective Stage, individuals actively appraise the motives, meaning, and relevance of the ostracism experience. Within this evaluative process, impression formation may also emerge as a way of making sense of the initial affective reaction. Indeed, ostracized individuals may cope by attributing intentionally negative traits to the source, which can lead them to devalue it and thereby mitigate the emotional impact of the experience (Williams 2007; Wesselmann et al. 2010). Supporting this reasoning, Zadro and colleagues (2006) found that ostracized people, compared to included ones, evaluated the sources as less physically attractive and possessing more negative personality traits. Similarly, Sloan and colleagues (2011) reported that the sources of ostracism are perceived as less trustworthy, more prejudiced, and more arrogant than the sources of inclusion. Importantly, Paolini and colleagues (2016) also showed that bystanders to ostracism hold a negative impression of the sources of ostracism.

To sum up, scientific evidence highlights that the immediate response to ostracism is mainly affective and linked to the threat of basic needs. In addition, some research also shows that victims form an impression of the sources, trying to mentalize their psychological state to understand whether they can be a resource or a threat (e.g., Fiske and Neuberg 1990). This suggests that cognitive processes follow the initial affective reaction. Neuroscientific literature supports this view, showing that impression formation involves cortical regions associated with complex high-level cognitive functions, such as the dorsomedial prefrontal cortex, the superior temporal sulcus, and the orbitofrontal cortex (Mitchell et al. 2006).

In the present contribution, we aimed to verify the comprehensive role of affective and cognitive responses as antecedents of antisocial behaviors toward the sources of ostracism, relying upon the TNTM. As a preliminary step, we sought to confirm previous findings on the differences between ostracism and inclusion in terms of need, mood, impression, and antisocial behaviors. First, we predicted that ostracized people (vs included) would report a decrease in both need satisfaction (i.e., belongingness, self-esteem, control, and meaningful existence) and mood as an immediate affective reaction to ostracism (HP1). Furthermore, consistent with cognitive findings (i.e., Zadro et al. 2006), we hypothesized that ostracized people (vs included) would form a negative (vs positive) impression of the sources of ostracism (HP2).

In terms of behavior, Lelieveld and colleagues (2013, experiment 3) investigated whether contextual factors (i.e., financial compensation) influenced the behavioral responses of ostracized participants. During the Cyberball game, ostracized participants either achieved money for each ball pass they did not receive (financial compensation condition) or did not (neutral condition). Afterward, they were invited to play Dictator Games (Forsythe et al. 1994) in which they had to divide €10 between themselves and the sources of Cyberball. The authors revealed that ostracized (vs included) participants allocated less money to the sources. Furthermore, participants allocated more money to sources that had ostracized them when they were in the financial compensation condition than when they were in the neutral condition. Thus, it seems that the valence of ostracism’s experience guides the implementation of prosocial or antisocial behavior. Since ostracism is a negative social phenomenon that undermines individuals’ psychological well-being, it is reasonable to expect that being ostracized leads to antisocial behaviors. Using the Dictator Game, we therefore anticipated that ostracized participants (vs included) would allocate less money toward the sources of ostracism (HP3a). At the same time, we acknowledge that prior research has shown that ostracism can sometimes elicit displaced aggression toward neutral or unrelated targets (Twenge et al. 2001; Ren et al. 2016). However, we expected that participants in our study would still allocate less money to the sources than to unrelated others (HP3b). This expectation is grounded in the idea that the primary target of negative responses is typically the source of ostracism, as these individuals are most directly responsible for the exclusion experience (Lelieveld et al. 2013; Williams 2007). Finally, we predicted that ostracism would not significantly affect allocations to unrelated others (HP3c). This expectation reflects the methodological context of our study: in the Dictator Game, the ostracizing sources were salient and directly linked to the exclusion episode, whereas unrelated others are neutral and not implicated in the episode. Under these circumstances, antisocial responses were expected to be concentrated on the ostracizers as the most salient norm violators, reducing the likelihood of displaced aggression toward neutral targets (cf. Twenge et al. 2001; Ren et al. 2016).

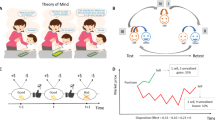

The lines of work described above, on first impressions, imply that impression formation can play a crucial role in reactions to ostracism. In the present study, we aimed to deepen this line of inquiry by integrating, for the first time, impression formation into the TNTM. Although both ostracism and impression formation concern interpersonal responses, they have not yet been integrated into a comprehensive model. Different hypotheses can be formulated regarding the interplay of ostracism, need satisfaction, mood, and impression formation. We reasoned that, when facing ostracism, people require time to mentalize their experience (Williams 2009) and understand why a stranger is excluding them. In this sequence, we expected that impression formation would intervene immediately after need satisfaction as a cognitive reaction to ostracism. Empirical evidence indicates that targets of ostracism tend to form negative impressions of ostracizers. Such evaluations may arise both as a direct response to the ostracizers’ norm-violating behavior (i.e., exclusion) and as a coping strategy to protect self-esteem and restore control after a socially threatening experience (Bastian et al. 2013; Williams and Nida 2011). Importantly, these two processes are not mutually exclusive but may operate simultaneously. In our study, participants evaluated ostracizers whom they did not personally know, suggesting that negative impressions may reflect both recognition of unfair behavior and psychological regulation to cope with ostracism. Consistently, recent work on first impressions has shown that even when targets are expected to elicit strong negativity, average evaluations remain moderate (Aquino et al. 2024). Thus, negative evaluations in ostracism may reflect a combination of social judgment and psychological regulation. Based on this reasoning, we hypothesized that ostracism would exert a direct effect on need satisfaction and mood, which in turn would mediate its impact on impressions of the sources. Finally, these impressions were expected to predict antisocial behavior, namely, the allocation of money toward the sources (see Fig. 1, HP4a).

Considering the complex interplay between affect and cognition in predicting behavior (e.g., Rocklage and Luttrell 2021), an alternative temporal hypothesis suggests that impression formation occurs with mood shifts, rather than as a subsequent, independent step. To determine whether impression formation occurs in a distinct second phase—as opposed to simultaneously with the initial affective response—we employed structural equation modeling. This method allows for the comparison of alternative models to identify the best fit to the data. Accordingly, we also tested an alternative model (HP4b) in which need satisfaction, mood, and impression formation operate simultaneously rather than sequentially.

Method

Participants and design

Hair and colleagues (2010) suggested that the sample size should be five times the number of items in the questionnaire. As applied to our research, a sample size of minimum 130 participants was required. However, considering potential drop-out, questionnaires were administered to a sample of 168 respondents (83 females and 85 males; mean age = 22.75; SD = 3.41). Participants were randomly assigned to the conditions (Cyberball experience: inclusion vs ostracism) in a between-subjects design.

Procedure

Participants were individually escorted to the social psychology laboratory. Before starting the research, according to the ethical standards Declaration of Helsinki (2001), participants were informed about all relevant aspects of the study (e.g., methods, institutional affiliations of the researcher). They were apprised of their right to anonymity, to refuse to participate in the study, or to withdraw their consent to participate at any time during the study without fear of reprisal. Participants then confirmed that they had understood the instructions correctly, agreed to participate in the study, and provided their demographic information. In the first section, participants were introduced to a three-player online virtual ball-tossing game—namely Cyberball (Williams et al. 2000). After the manipulation of ostracism, participants completed the Need-Satisfaction and the mood Scale (Zadro et al. 2004, 2006). Subsequently, participants rated the Cyberball manipulation check, and then, they completed the measure about their impression of the source. Finally, we assessed the behavior towards the source through a set of dictator games. At the end, participants were thanked and fully debriefed.

Measures

Ostracism manipulation

Participants were informed that they would take part in a three-player online virtual ball-tossing game—namely Cyberball (Williams et al. 2000). They were told that they were participating in research about their mental visualization ability and were led to believe they would play with two other players connected via the campus intranet. Actually, the other two players were pre-programmed avatars. Participants were asked to exercise mental visualization skills while playing the game; they were asked to imagine the context of the game and what the other players were like. The two fictitious players were labeled as Player A and Player B. These players were the sources and placed at the top of the screen on the right and on the left, respectively. Half of the participants were ostracized during the Cyberball game (i.e., they received one toss at the beginning and then never received another toss), and the other half of the participants were equally included by other players (i.e., they received one-third of the tosses). The game proceeded for 3 min, for a total amount of 30 throws (Williams and Jarvis 2006).

Need satisfaction and mood scale

Participants completed 20-items of the Need-Satisfaction Scale (Zadro et al. 2004; see also Williams et al. 2000) assessing the impact of Cyberball on belongness (e.g., ‘I felt excluded’; ‘I felt disconnected’), self-esteem (e.g., ‘I felt liked’; ‘I felt satisfied’), control (e.g., ‘I felt I had control’; ‘I felt to able to significantly modify the events’), meaningful existence (e.g., ‘I felt invisible’; ‘I felt useful’) and they also completed an 8-items scale about the mood they felt during the game on positive and negative level (on a Likert-type scale from 1 (Not at all) to 7 (Extremely). Considering that the four needs had sometimes impacted in different ways on the expected outcome (e.g., Williams 2009), we tested our model by considering both the separated and the combined scores of needs. Given that no differences emerged in the hypothesized pattern, we decided to compute a total score of need satisfaction, following previous literature (van Beest and Williams 2006; Williams et al. 2000; Zadro et al. 2006). After reverse-coding negative items, we averaged responses to the “Need Satisfaction Scale” into a need satisfaction index (α = 0.93) and the questions about emotions into a mood index (α = 0.81). Lower ratings signaled more need threat and negative mood, higher ratings indicated more need satisfaction and positive mood.

The differential analyses for each need are available at: https://osf.io/zmgt5/?view_only=9a49c6547c9e43f79beaafc4e2c28f9e

Manipulation check

Participants responded to two items, “I was ignored” and “I was excluded” on a scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 7 (extremely). They also responded to the following open-ended question: “Assuming the ball should be thrown to each person equally (33%), what percentage of the throws did you receive?”.

Impression formation

Participants were asked to report their overall impression of each of the two players they had interacted with during the Cyberball game. They reported their response to the question “What is your general impression of Player [A; B]?” on a scale ranging from 1 (= extremely negative) to 7 (= extremely positive). Responses were averaged to create a single index of impression toward the sources (r = 0.65; p < 0.001). Lower ratings signaled a more negative impression, while higher ratings signaled a more positive impression.

Antisocial behavioral responses

Participants randomly played three different Dictator Games (Forsythe et al. 1994), in which they had to allocate ten euros between themselves and another individual. In the first two Dictator Game participants had to decide to share money between themselves and Player A and Player B, respectively. In the last one, they had to allocate money between themselves and new people with whom they did not have any contacts before (unrelated others). In each game, participants could choose between 6 combinations: 1 (8 euros for themselves, 2 for the others), 2 (7 euros for themselves, 3 for the others), 3 (6 euros for themselves, 4 for the others), 4 (5 euros for themselves, 5 for the others), 5 (4 euros for themselves, 6 for the others) and 6 (3 euros for themselves, 7 euros for the others). We averaged responses related to players A and B into a single index (r = 0.78; p < 0.001). In this way, lower ratings signaled less money allocation to the sources and more to themselves, higher ratings indicated more money allocation to the sources and less to themselves.

Results

Data analysis

Unless otherwise specified, we performed a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for each dependent variable, with the Cyberball experience (ostracism vs inclusion) as a between-subjects factor. Path analysis was performed through the regression approach and the bootstrap estimation in AMOS 21 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL 60606, USA). We further run a 1000-simulation Power Analysis for Significant Parameter Estimation (Wang and Rhemtulla 2021).

Manipulation check

Firstly, we evaluated the effectiveness of the Cyberball manipulation. Ostracized participants felt more ignored (M = 5.92, SD = 1.12) and excluded (M = 5.69, SD = 1.32) than included participants (M = 2.12, SD = 1.45; M = 2.06, SD = 1.59, respectively), F (1, 152) = 331.66, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.69; F (1, 152) = 236.25, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.61, respectively. Moreover, participants assigned to the ostracism condition reported that they received fewer throws out of the total (M = 9.97, SD = 7.71) compared to participants assigned to the inclusion condition (M = 32.82, SD = 14.18, F (1, 152) = 108.40, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.41. Taken together, these findings confirmed the effectiveness of our manipulation.

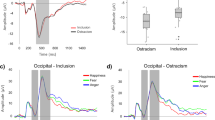

Need satisfaction, mood, and impressions toward the sources

The ANOVA on need satisfaction showed that ostracized participants reported a lower level of need satisfaction (M = 2.93, SD = 0.72) than included participants (M = 4.77, SD = 0.79), F (1, 166) = 275.39, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.62. The ANOVA on mood showed that ostracized participants reported lower scores of mood (M = 4.41, SD = 0.87) than included participants (M = 5.49, SD = 0.85), F (1, 166) = 64.78, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.28. Finally, the ANOVA on impression towards the sources of ostracism showed that ostracized participants reported a more negative impression (M = 2.75, SD = 0.94) than the included participants (M = 4.61, SD = 0.98), F (1, 166) = 156.87, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.49.

Results confirmed our first two hypotheses, indicating that ostracized (vs included) participants felt more threatened (i.e., less need satisfaction and more negative mood; Hp1) and reported a more negative impression toward the sources (Hp2).

Anti-social behavioral responses

A 2 (Cyberball experience: inclusion vs ostracism) × 2 (Dictator game: sources vs unrelated others) R mixed-model ANOVA was conducted with dictator game varying within participants. The ANOVA showed a significant two-way interaction (F (1, 165) = 13.62, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.08).

A simple effects analysis confirmed our hypotheses regarding the impact of ostracism on monetary allocations in the Dictator Game. Supporting Hp3a, ostracized participants allocated significantly less money to the sources of ostracism (M = 3.57, SD = 1.26) than included participants (M = 4.19, SD = 1.15), F (1, 165) = 11.24, p = 0.001, η² = 0.06. Consistent with Hp3b, in the ostracism condition, participants allocated less money to the sources compared to the unrelated other person, F(1, 165) = 17.06, p = 0.001, η² = 0.09, indicating that the negative response was specifically directed toward the ostracizers rather than neutral recipients. In contrast, in the inclusion condition, no significant difference emerged between sources and unrelated others, F(1, 165) = 1.20, p = 0.27, η² = 0.01. Finally, in line with Hp3c, allocations to the unrelated other did not differ between ostracized (M = 4.19, SD = 1.25) and included participants (M = 4.02, SD = 1.36), F(1, 165) = 0.68, p = 0.41, η² = 0.004.Footnote 1

Structural equation modeling

Table 1 shows the mean, standard deviation, and correlation coefficients among all measures.

In line with our HP4a, we drew a predictive model where ostracism had a direct effect on the impression towards the sources as well as an indirect effect mediated by both need satisfaction and mood. Given that need satisfaction and mood have been shown to be related to each other in previous literature (Zadro et al. 2004), we included a correlation between the error terms of these endogenous variables. We further expected that the impression towards the sources would predict the allocation of money toward the sources. To assess the fit of the proposed model, we report the chi-square goodness of fit test, the non-normed fit index (NNFI), the comparative fit index (CFI), and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). A chi-square value of zero indicates optimal fit, whereas a higher chi-square value indicates worse fit. More specifically, a non-significant chi-square indicates that the difference between the observed and estimated variance/covariance matrices is not significantly different from zero. The NNFI and CFI indicated the extent to which the tested model improves upon the null model, which assumes no covariance among the measured variables.

The value of these indices can vary between 0 and 1, with higher values indicating a better fit between the observed and estimated covariance matrices. The RMSEA indicated how well the model, with unknown but optimally estimated parameters, would fit the population’s covariance matrix. SRMR is an absolute measure of fit, defined as the standardized difference between the observed correlation and the predicted correlation. Because the SRMR is an absolute measure of fit, a value of zero indicates a perfect fit. SRMR and RMSEA values < 0.08, suggest an acceptable model fit, while values < 0.05 indicate excellent model fit. CFI and TLI > 0.90 indicate good model fit, while values > 0.95 reflects an excellent model fit. To test the indirect effects, we used bootstrapping (with 1000 resamples) to compute 95% confidence intervals (CI). CIs that do not include 0 denote statistically significant effects. Since our focus was on the ostracism condition, we included it in the SEM model as a dummy variable, assigning a value of 1 to ostracism and 0 to inclusion. We assumed that the variances/covariances of the endogenous variables were equivalent between the conditions.

Our hypothesized model (Fig. 2, HP4a) fits the data extremely well (HP3a), as indicated by a non-significant chi value = 1,93, p = 0.588, high NFI and CFI values (1 and 0.99, respectively), a RMSEA of 0.01 (CIs = 0.00; 0.10), and SRMR of 0.02.

As expected, the ostracism predicted both the level of both need satisfaction (β = −0.79; p < 0.001, 95% CIs: −0.88; −0.69, Power: 0.99) and the mood (β = −0.53.; p < 0.001, 95% CIs: −0.66; −0.39, Power: 0.98), which in turn predicted the impression towards the source of ostracism (β = 0.46; p < 0.001 for need; Power: 0.99; 95% CIs: 0.52; 0.81; β = 0.16; p = 0.023; 95% CIs: 0.01; 0.27 for mood, Power: 0.42). Need satisfaction and mood partially mediated the effect of ostracism on the impression towards the source of ostracism. Alongside a significant indirect effect (I.E. = −0.44; p = 0.001; 95% CIs: −0.54; −0.35), the direct effect remained significant (β = −0.25; p = 0.002; 95% CIs: −0.36; −0.14, Power: 0.43). As expected, impression towards the source of ostracism predicted the amount of money allocated to the source (and consequently to themselves), β = 0.38; p = 0.001; 95% CIs: 0.26; 0.49, Power: 0.99). The impression towards the source of ostracism fully mediated the effect of both need satisfaction and mood on the money allocation toward the sources. Neither the direct effect of participants’ level of need satisfaction (β = −0.10; p = 0.396; 95% CIs: −0.31; 0.10) nor that of mood (β = 0.14; p = 0.20; 95% CIs: −0.04; 0.33) on money allocation toward the sources was significant. Consistent with our hypothesis, we observed a significant indirect effect of both need satisfaction and mood on money allocation (I.E. = 0.17; p = 0.001; 95% CIs: 0.08; 0.28; I.E. = 0.06; p = 0.014; 95% CIs: 0.01; 0.12, respectively).

Of relevance for our purpose, the ostracism did not exert a direct effect on money allocation (β = 0.03; p = 0.747; 95% CIs: −0.14; 0.20), but only an indirect effect (I.E. = −0.28; p = 0.001; 95% CIs: −0.40; −0.16), giving support to our predictive model.

As a control process, we tested the same model considering the allocation toward the unrelated other person. In this case, no variables predicted the allocation toward the unrelated other, either directly or indirectly, including the impression (β = −0.04; p = 0.786; 95% CIs: −0.24; 0.65), supporting our hypotheses.

Finally, we also tested an alternative model in which impression, need satisfaction, and mood simultaneously predicted the money allocation toward the sources (HP4b). However, this model did not show good fit indices: χ2 (3): 52.75, p = 0.000; RMSEA: 0.31; SRMR: 09; CFI:.89; TLI: 0.65.

Taken together, the results confirmed our hypothesized model (HP4a), showing that the ostracism had a direct effect on the impression towards the sources, as well as an indirect effect mediated by both need satisfaction and mood. In turn, the impression predicted the allocation of money toward the sources. Our findings clearly demonstrated that impression toward the source fully mediated the impact of ostracism, need satisfaction, and mood on behavior (i.e., the allocation of money to the source of ostracism).

Discussion

The present study aimed to verify the comprehensive role of affective and cognitive consequences as antecedents of antisocial behavioral response toward the sources of ostracism, relying upon the TNTM. Notably, we introduced, for the first time, the concept of impression formation into the TNTM. To this end, we tested a sequential model that incorporated both need satisfaction and impression formation. Various hypotheses can be formulated regarding the interplay between need satisfaction, mood, and impression formation. We reasoned that in front of an ostracism experience, people need time to mentalize their experience (as suggested by Williams 2009) and to understand the motives behind a stranger’s exclusionary behavior. In this sequence, we expected that impression formation would intervene immediately after need satisfaction as a cognitive response to ostracism. At the same time, it is important to acknowledge that negative impressions of ostracizers may not only serve as a coping mechanism, but may also arise as a direct response to their norm-violating behavior. Excluding someone from a social interaction represents a violation of fundamental relational expectations, and such violations are often met with moral condemnation and negative evaluations (e.g., Lelieveld et al. 2013). Taken together, these considerations suggest that impression formation following ostracism may serve a dual role: it can help individuals cope with the immediate psychological threat of exclusion, while also functioning as a social evaluation of the norm-violating behavior of the ostracizers.

Crucially, in line with our hypothesis, we successfully tested a comprehensive temporal model, showing that ostracism exerted a direct effect on the impression towards the sources and an indirect effect through the mediation of both need satisfaction and mood. Then, in turn, the impression predicted the allocation of money toward the sources. These findings significantly contribute to research on both ostracism and the evaluation field. From the ostracism perspective, the present study represents one of the first empirical confirmations of a processual model about the consequences of ostracism. In line with the temporal model hypothesized by Williams (2009), after a reflexive reaction (e.g., threat of basic need and lowering level of mood as a proxy of an affective reaction) people shape a negative impression towards the source of ostracism as a proxy of a socio-cognitive process in which they try to explain the ostracism experience (i.e., reflective stage). In other words, the first impression of the source intervenes immediately after the instinctive affective reaction (i.e., reflexive stage), representing the first step towards the second temporal stage (reflective stage), in which cognition sits alongside affectivity, gradually assuming an increasingly important role in the coping process. In line with the impression formation configurational model (Asch 1957), ostracized individuals use ostracism as a central diagnostic cue around which they build their global evaluation of the source. In terms of cue diagnosis, person-perception research provides evidence for a negativity bias (Skowronski and Carlston 1987), meaning that a person’s negative behavior (i.e., ostracizing the victim) acts as a central cue in impression formation (Baumeister et al. 2001; Rozin and Royzman 2001). Our findings confirm that impression formation is a high-level cognitive activity (Mitchell et al. 2006), which requires people to mentalize the other's psychological state to understand if the other person can be a resource or a threat for the perceiver (Fiske and Neuberg 1990).

It is important to note that the alternative model with a parallel (and not temporal) sequence of mediators did not fit the data well, as well as the model with behavioral response towards unrelated others. From both methodological and theoretical points of view, these control analyses increase the confidence that we have identified the process underlying the behavioral response to ostracism.

Moreover, the present study confirmed the relevant role of both cognitive and affective reactions in determining the behavioral responses (e.g., Di Plinio et al. 2023; Haddock and Maio 2019). Recently, Kiviniemi and colleagues (2017) argued that it is important not to focus on models that treat thoughts and feelings as distinct phenomena, but to consider the interplay of affect and cognition. Accordingly, the ostracism experience impact on need satisfaction and mood that serves an affective informational role, guiding the content and valence of subsequent formation of the impression towards the source of ostracism as cognitive processing of the negative affective experience of ostracism. The interplay of affect and cognition in ostracism leads to the behavioral reaction of ostracized people, punishing the source of ostracism by giving them less money. This behavior reaction leads to a spiral of negative action, which can have important consequences on long-term for both the ostracized and the ostracizing people (Paolini 2019; Riva et al. 2016). Furthermore, our findings underlined the importance of considering the first signals of ostracism, in order to avoid the above-mentioned negativity spiral. Ad hoc program intervention would address to envelop or enhance a group-based resilience to face and prevent the negative consequences of ostracism (Pagliaro et al. 2013).

It is worth noting that the observed pattern holds across different threatened needs, thereby strengthening the robustness of our findings. Although this consistency is not unexpected in the ostracism literature (e.g., van Beest and Williams 2006), TNTM suggests that distinct types of need threat may elicit different coping responses. A plausible explanation for the consistency of our results may lie in the relatively limited variance of the outcome measures—specifically, the reliance on a unidimensional valence measure and a single antisocial behavioral outcome—which could have constrained the emergence of differential effects. Future research employing multidimensional mediators or a broader range of outcomes may reveal distinct patterns for each threatened need (e.g., Sacino et al. 2024).

Our results also confirmed previous literature about the affective, cognitive, and behavioral consequences of ostracism. Indeed, we confirmed that ostracized people (vs included) reported a decrease in need satisfaction (i.e., belongingness, self-esteem, control, and meaningful existence) and negative mood, as an immediate affective reaction to ostracism (Williams 2009). Moreover, our findings confirmed that ostracized people (vs included) shaped a more negative impression towards the sources of ostracism (Zadro et al. 2006; Paolini et al. 2017; Twenge et al. 2001). Finally, moving to the behavioral consequences, our findings confirmed that ostracized participants allocated less money to the sources compared with included participants (Lelieveld et al. 2013).

Limitations and future directions

Our results do present limitations worth noting and raise questions for future investigation. First, we used an allocation game with money choice by considering only anti-social behaviors. Although this measure has an established tradition in ostracism studies (see Paolini et al. 2019, for a review), research revealed that people vary greatly in their responses to being ostracized, showing not only antisocial behavior but also prosocial and withdrawal behavior (Salvati et al. 2019; for a review, see Kip et al. 2025). Future research could be directed at understanding what factors can lead ostracized people to behave in different, as well as in opposite ways. From a methodological point of view, we did not randomize the order in which the various dependent variables were assessed. Participants first completed the need satisfaction and the impression formation, which were followed by the allocation game. We chose this order because we were interested in understanding the role of mood, need satisfaction, and impression formation on behavioral response, thus, the choice was guided by our theoretical model. Another limitation of the present study was the use of a single item to assess the impression of others. Although such measures are common within psychology (Allen et al. 2022), a multiple-dimensional measure of the impression could give interesting and innovative insight. In this regard, extensive research has shown that our first impressions of others are centered around two global social dimensions. While these dimensions have been referred to under varying names and have been defined somewhat differently, they share much common content (see Abele and Wojciszke 2007; Abele et al. 2021 for a review). Communion comprises characteristics that are related to forming and maintaining social connections (also referred to as warmth or nurturance, e.g., Abele and Wojciszke 2007; Fiske, Cuddy and Glick 2007), whereas agency comprises characteristics aimed at pursuing personal goals and manifesting skills and accomplishments (also referred to as competence or dominance). According to a functional interpretation of these classes of information, when an individual meets a new person, they want to know the person’s intentions—that is, whether they represent an opportunity or a threat (communion) and their capability—that is, whether they are able to put their intentions into action (agency). More recently, research has jettisoned the warmth dimension, distinguishing instead between sociability (e.g., friendliness and likeability) and morality (e.g., honesty and trustworthiness) and showing that morality plays a far greater role than sociability (and competence) in shaping evaluations of individuals and groups (see Brambilla et al. 2021 for a review). Considering the predominant role of morality in predicting behavioral responses (Brambilla et al. 2013), future studies could assess impression across multiple traits and examine potential differences among them in the ostracism reaction. Furthermore, in the present study, we reasoned that impression formation may serve a dual role, functioning both as a coping mechanism and as an evaluative response to norm-violating behavior. Future studies could help to disentangle these processes more clearly, for example, by directly assessing coping responses to exclusion in order to determine the extent to which negative impressions reflect psychological regulation vs immediate evaluative reactions.

Another promising direction for future research concerns the investigation of dehumanization, broadly defined as the denial of full humanness to others, often through the attribution of fewer uniquely human traits (Haslam 2006). Regarding ostracism, dehumanization has been hypothesized to serve a self-protective function, allowing individuals to reduce the emotional impact of negative social experiences (Bastian et al. 2013). In this sense, these findings align with our interpretation of impression formation as a functional coping strategy. At the same time, dehumanization may serve additional functions, such as legitimizing retaliatory behaviors against the source of exclusion (Bastian et al. 2013). Importantly, research on ostracism suggests that these processes are not limited to other-perceptions: victims may also engage in self-dehumanization, experiencing themselves as less human following exclusion (Bastian and Haslam 2010). Considering both self- and other-directed dehumanization could therefore provide a more comprehensive understanding of the divergent behavioral responses observed after ostracism. Future studies would benefit from integrating measures of self- and other-perceptions to clarify how these processes interact in shaping reactions to social exclusion.

Finally, it remains an open question whether antisocial responses generalize beyond the direct sources of exclusion. In our study, unrelated others were unaffected in the Dictator Game (Hp3c), consistent with the idea that participants targeted their reactions toward identifiable ostracizers. Yet prior work has documented displaced aggression against neutral targets (Twenge et al. 2001; Ren et al. 2016). This discrepancy suggests that contextual and individual factors—such as anonymity, salience of alternative targets, or opportunities for retaliation—may determine whether antisocial responses extend more broadly. Future investigations could explicitly manipulate these factors to clarify the conditions under which aggression spreads beyond the immediate perpetrators of exclusion.

Conclusion

To sum up, the present research revealed how ostracized people react to this unexpected negative experience and provided further evidence on an individual’s behavioral response to ostracism. We therefore provide initial evidence that the negative behavioral intention toward the sources are driven by a pattern of affective and cognitive consequences, thereby opening new and intriguing avenues for future research—for instance, on the interplay of affective and cognitive consequences to ostracism.

Data availability

Dataset and supplementary analyses are available at the following link: https://osf.io/zmgt5/?view_only=9a49c6547c9e43f79beaafc4e2c28f9e.

Notes

As control analyses, in an explorative way, we looked at the interaction between ostracism and gender for need satisfaction, mood, impression, and behavior. ANOVA did not show a significant gender effect for any of the dependent variables, Fneed (1, 162) = 1.24, p = 0.266; Fmood (1, 162) = 0.31, p = 0.581; Fimpression (1, 162) = 1.04, p = 0.311, Fbehavior (1, 162) = 1.24, p = 0.661.

References

Abele AE, Wojciszke B (2007) Agency and communion from the perspective of self versus others. J Personal Soc Psychol 93(5):751–763. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.93.5.751

Abele AE, Ellemers N, Fiske ST, Koch A, Yzerbyt V (2021) Navigating the social world: toward an integrated framework for evaluating self, individuals, and groups. Psychol Rev 128(2):290–314. https://doi.org/10.1037/rev0000262

Allen MS, Iliescu D, Greiff S (2022) Single item measures in psychological science. Eur J Psychol Assess 38(1):1–5. https://doi.org/10.1027/1015-5759/a000699

Aquino A, Fontanella L, Walker M, Haddock G, Alparone FR (2024) What your face says: how signals of communion and agency inform first impressions and behavioural intentions. Eur J Soc Psychol 55(1):54–69. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.3117

Asch SE (1957) An experimental investigation of group influence. In: Symp&&osium on preventive and social psychiatry. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC. https://doi.org/10.1177/002076405900500216

Bastian B, Haslam N (2010) Excluded from humanity: the dehumanizing effects of social ostracism. J Exp Soc Psychol 46(1):107–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2009.06.022

Bastian B, Jetten J, Chen H, Radke HR, Harding JF, Fasoli F (2013) Losing our humanity: the self-dehumanizing consequences of social ostracism. Personal Soc Psychol Bull 39(2):156–169. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167212471205

Baumeister RF, Leary MR (1995) The need to belong: desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychol Bull 117(3):497–529. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.497

Baumeister RF, Bratslavsky E, Finkenauer C, Vohs KD (2001) Bad is stronger than good. Rev Gen Psychol 5(4):323–370. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.5.4.323

Brambilla M, Sacchi S, Pagliaro S, Ellemers N (2013) Morality and intergroup relations: threats to safety and group image predict the desire to interact with outgroup and ingroup members. J Exp Soc Psychol 49:811–821. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2013.04.005

Brambilla M, Sacchi S, Rusconi P, Goodwin GP (2021) The primacy of morality in impression development: theory, research, and future directions. In: Advances in experimental social psychology, vol 64. Academic Press, pp 187–262

Carter-Sowell AR, Chen Z, Williams KD (2008) Ostracism increases social susceptibility. Soc Influence 3(3):143–153. https://doi.org/10.1080/15534510802204868

Chow RM, Tiedens LZ, Govan CL (2008) Excluded emotions: the role of anger in antisocial responses to ostracism. J Exp Soc Psychol 44(3):896–903. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2007.09.004

Deci EL, Ryan RM (2000) The” what” and” why” of goal pursuits: human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychol Inq 11(4):227–268. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01

Di Plinio S, Aquino A, Haddock G, Alparone FR, Ebisch SJH (2023) Brain and behavioral contributions to individual choices in response to affective–cognitive persuasion. Cereb Cortex 33:2361–2374. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhac213

Eisenberger NI, Lieberman MD, Williams KD (2003) Does rejection hurt? An fMRI study of social exclusion. Science 302:290–292. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1089134

Fiske ST, Neuberg SL (1990) A continuum of impression formation, from category-based to individuating processes: influences of information and motivation on attention and interpretation. Adv Exp Social Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0065-2601(08)60317-2

Fiske ST, Cuddy AJC, Glick P (2007) Universal dimensions of social cognition: warmth and competence. Trends Cogn Sci 11(2):77–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2006.11.005

Forsythe R, Horowitz JL, Savin NE, Sefton M (1994) Fairness in simple bargaining experiments. Games Econ Behav 6(3):347–369. https://doi.org/10.1006/game.1994.1021

Goodwin SA, Williams KD, Carter-Sowell AR (2010) The psychological sting of stigma: the costs of attributing ostracism to racism. J Exp Soc Psychol 46(4):612–618. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2010.02.002

Haddock G, Maio GR (2019) Inter-individual differences in attitude content: cognition, affect, and attitudes. Adv Exp Soc Psychol 59:53–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.aesp.2018.10.002

Hair JF, Anderson RE, Babin BJ, Black WC (2010) Multivariate data analysis: a global perspective, vol 7. Pearson Upper Saddle River

Hartgerink CHJ, Van Beest I, Wicherts JM, Williams KD (2015) The ordinal effects of ostracism: a meta-analysis of 120 cyberball studies. PLoS One 10:e0127002. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0127002

Haselton MG, Buss DM (2000) Error management theory: a new perspective on biases cross-sex mind reading. J Personal Soc Psychol 78:81–91. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.78.1.81

Haslam N (2006) Dehumanization: an integrative review. Personal Soc Psychol Rev 10(3):252–264. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327957pspr1003_4

Ijzerman H, Semin GR (2009) The thermometer of social relations: mapping social proximity on temperature. Psychol Sci 20(10):1214–1220. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.024

Ijzerman H, Gallucci M, Pouw WTJL, Weibgerber C, Van Doesum NJ, Williams KD (2012) Cold-blooded loneliness: social exclusion leads to lower skin temperature. Acta Psychol 140:283–288. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actpsy.2012.05.002

Kerr NL, Levine JM (2008) The detection of social exclusion: evolution and beyond. Group Dyn Theory, Res, Pract 12(1):39–52. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2699.12.1.39

Kip A, Erle TM, Sleegers WW, van Beest I (2025) Choice availability and incentive structure determine how people cope with ostracism. J Exp Soc Psychol 117:104707. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2024.104707

Kiviniemi MT, Ellis EM, Hall MG, Moss JL, Lillie SE, Brewer NT, Klein WMP (2017) Mediation, moderation, and context: Understanding complex relations among cognition, affect, and health behaviour. Psychol Health 33(1):98–116. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2017.1324973

Lakin JL, Chartrand TL, Arkin RM (2008) I am too just like you: Nonconscious mimicry as an automatic behavioral response to social exclusion. Psychol Sci 19(8):816–822. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02162.x

Lelieveld GJ, Moor BG, Crone EA, Karremans JC, van Beest I (2013) A penny for your pain? The financial compensation of social pain after exclusion. Soc Psychol Personal Sci 4:206–214. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550612446661

Mitchell JP, Macrae CN, Banaji MR (2006) Dissociable medial prefrontal contributions to judgments of similar and dissimilar others. Neuron 50(4):655–663. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2006.03.040

Oaten M, Williams KD, Jones A, Zadro L (2008) The effects of ostracism on self-regulation in the socially anxious. J Soc Clin Psychol 27(5):471–504. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2008.27.5.471

Pagliaro S, Alparone FR, Picconi L, Paolini D, Aquino A (2013) Group based resiliency: contrasting the negative effects of threat to the ingroup. Curr Res Soc Psychol 21:35–41

Paolini D (2019) L’ostracismo e le sue conseguenze: una rassegna della letteratura [The ostracism and its consequences: a review of literature]. Psicologia Soc 3:317–342. https://doi.org/10.1482/94938

Paolini D, Alparone FR, Cardone D, van Beest I, Merla A (2016) The face of ostracism»: the impact of the social categorization on the thermal facial responses of the target and the observer. Acta Psychol 163:65–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actpsy.2015.11.001

Paolini D, Giacomantonio M, van Beest I, Baiocco R (2020) Social exclusion lowers working memory capacity in gay-men but not in heterosexual-men. Appl Cogn Psychol 34:761–767. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.3661

Paolini D, Pagliaro S, Alparone FR, Marotta F, van Beest I (2017) On vicarious ostracism. Examining the mediators of observers’ reactions towards the target and the sources of ostracism. Soc Influence 12(4):117–127. https://doi.org/10.1080/15534510.2017.1377107

Ren D, Wesselmann E, Williams KD (2016) Evidence for another response to ostracism: Solitude seeking. Soc Psychol Personal Sci 7(3):204–212. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550615616169

Ren D, Wesselmann ED, Williams KD (2018) Hurt people hurt people: ostracism and aggression. Curr Opin Psychol 19:34–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.03.026

Riva P, Montali L, Wirth JH, Curioni S, Williams KD (2016) Chronic social exclusion and evidence for the resignation stage: an empirical investigation. J Soc Personal Relatsh 34(4):541–564. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407516644348

Riva P, Williams KD, Torstrick AM, Montali L (2014) Orders to shoot (a camera): effects of ostracism on obedience. J Soc Psychol 154(3):208–216. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224545.2014.883354

Rocklage MD, Luttrell A (2021) Attitudes based on feelings: Fixed or fleeting?. Psychol Sci 32(3):364–380. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797620965532

Rozin P, Royzman EB (2001) Negativity bias, negativity dominance, and contagion. Personal Soc Psychol Rev 5(4):296–320. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327957pspr0504_2

Sacino A, Aquino A, Paolini D, Andrighetto L (2024) The weight of a like on social networks: how self-monitoring moderates the effect of cyber-ostracism. Int Rev Social Psychol. https://doi.org/10.5334/irsp.855

Salvati M, Paolini D, Giacomantonio M (2019) Vicarious ostracism: behavioral responses of women observing an ostracized gay man. Rass di Psicol 36(2):53–60. https://doi.org/10.13133/1974-4854/16710

Schuklenk U (2001) Helsinki declaration revisions. Issues Med Ethics 9(1):29. https://doi.org/10.1001/virtualmentor.2001.3.2.mhst1-0102

Skowronski JJ, Carlston DE (1987) Social judgment and social memory: the role of cue diagnosticity in negativity, positivity, and extremity biases. J Personal Soc Psychol 52:689–699. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.52.4.689

Sleegers WW, Proulx T, van Beest I (2015) Extremism reduces conflict arousal and increases values affirmation in response to meaning violations. Biol Psychol 108:126–131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsycho.2015.03.012

Sloan LR, Wallace CM, Dingwall AA, Hubbard D (2011) Ostracism produces strong damage to African-American participants’ sense of belonging which in turn accounts for dramatically increased negative perceptions of their ostracizers. In NAAAS conference proceedings. National Association of African American Studies, p 1334

Spoor J, Williams KD (2007) The evolution of an ostracism detection system. In: Forgas JP, Haselton M, von Hippel W (eds) The evolution of the social mind: evolutionary psychology and social cognition. Psychology Press, New York, pp 279–292

Tedeschi JT (2001) Social power, influence, and aggression. In: Forgas JP, Williams KD (eds) The Sydney Symposium of Social Psychology. Social influence: direct and indirect processes. Psychology Press, New York, pp 109–126

Twenge JM, Baumeister RF, Tice DM, Stucke TS (2001) If you can’t join them, beat them: effects of social exclusion on aggressive behaviour. J Personal Soc Psychol 81:1058–1069. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.81.6.1058

Van Beest I, Williams KD (2006) When inclusion costs and ostracism pays, ostracism still hurts. J Personal Soc Psychol 91(5):918–928. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.91.5.918

Wang YA, Rhemtulla M (2021) Power analysis for parameter estimation in structural equation modeling: a discussion and tutorial. Adv Methods Practices Psychol Sci 4, 2515245920918253. https://doi.org/10.1177/2515245920918253

Wesselmann ED, Ren D, Williams KD (2010) Motivations for responses to ostracism. In: Forgas JP, Kruglanski AW, Williams KD (eds) The psychology of social conflict and aggression. Frontiers, pp 223–240. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203803813

Williams KD (2007) Ostracism. Annu Rev Psychol 58:425–452. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085641

Williams KD (2009) Ostracism: a temporal need-threat model. Adv Exp Soc Psychol 41:275–314. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0065-2601(08)00406-1

Williams KD, Jarvis B (2006) Cyberball: a program for use in research on ostracism and interpersonal acceptance. Behav Res Methods Instrum Comput 38:174–180. https://doi.org/10.3758/bf03192765

Williams KD, Nida SA (2011) Ostracism: consequences and coping. Curr Dir Psychol Sci 20(2):71–75. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721411402480

Williams KD, Zadro L (2005) Ostracism: the indiscriminate early detection system. In: Williams KD, Forgas JP, von Hippel W (eds) The social outcast: Ostracism, social exclusion, rejection, and bullying. Psychology Press, pp 19–34

Williams KD, Cheung CK, Choi W (2000) Cyberostracism: effects of being ignored over the Internet. J Personal Soc Psychol 79:748–762. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.79.5.748

Wirth J, Williams KD (2009) “They don’t like our kind”: consequences of being ostracized while possessing a group membership. Group Process Intergroup Relat 12(1):111–127. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430208098780

Xu E, Huang X, Robinson SL (2017) When self-view is at stake: responses to ostracism through the lens of self-verification theory. J Manag 43(7):2281–2302. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206314567779

Xu X, Kwan HK, Li M (2020) Experiencing workplace ostracism with loss of engagement. J Manag Psychol 35(8):617–630. https://doi.org/10.1108/jmp-03-2020-0144

Zadro L, Boland C, Richardson R (2006) How long does it last? The persistence of the effects of ostracism in the socially anxious. J Exp Soc Psychol 42(5):692–697. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2005.10.007

Zadro L, Williams KD, Richardson R (2004) How low can you go? Ostracism by a computer is sufficient to lower self-reported levels of belonging, control, self-esteem, and meaningful existence. J Exp Soc Psychol 40(4):560–567. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2005.10.007

Acknowledgements

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Dipartimento di Scienze della Salute, Università degliStudiMagna Graecia di Catanzaro.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AA and DP contributed equally to the study. FRA and MN conceived the research idea and collected data. AA and DP analyzed and interpreted data. All the authors contribute to developing the research and writing the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, the ethical standards of the APA Code of Conduct, and the ethical principles outlined by the Italian Association of Psychology (AIP; https://aipass.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/Codice-Etico_luglio-2022.pdf). Ethical approval body: Ethics Committee of the “G. d’Annunzio” University of Chieti-Pescara and the Provinces of Chieti and Pescara, Department of Neuroscience, Imaging and Clinical Science. Type of approval: exemption from ethical approval (waiver). Exemption number/ID: not applicable (no formal ID issued for exemptions under local regulations). Date when exemption was granted: 30 June 2022 Reason for exemption: at the time of data collection, Ethics Committee of the “G. d’Annunzio” University of Chieti-Pescara and the Provinces of Chieti and Pescara, Department of Neuroscience, Imaging and Clinical Science was responsible for research involving (a) medical data, (b) neuroimaging data, (c) pharmacological treatments, (d) animal research, or (e) studies entailing potential physical or psychological risks to participants. Our study did not fall within these categories; therefore, ethical approval was not required. Additional information: In line with the AIP ethical code (comma 11), researchers are encouraged to establish an ethics committee when one is not available. Such a committee has since been created at the Department of Neuroscience, Imaging and Clinical Science (Human Research Review Board).

Informed consent

All participants were informed about the aims and procedures of the study, and written informed consent was obtained individually from each participant prior to every data collection session. Informed consent was collected between 30 September 2022 and 30 November 2022 (the end of data collection). Participation was voluntary, and respondents were assured of the anonymity and confidentiality of their data, in compliance with the European Regulation (EU) no. 679/2016 (GDPR). The scope of the consent covered both participation in the study and the use of the collected data.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Aquino, A., Paolini, D., Nieli, M. et al. Being ostracized: the impact of emotional and cognitive responses on the antisocial behavior toward the sources of ostracism. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 13, 74 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-06370-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-06370-x