Abstract

The goal of academic medical postgraduate education in China is to train physician-scientists to meet increasing global health needs. However, a current lack of guidance on the competence on which these students should focus hinders their growth and offers them little confidence in the future, leading to shortages and losses of the health workforce. This study aims to construct a maturity competence model for medical academic postgraduate students. On the one hand, this study presents important competence-related structural aspects of academic medical postgraduates as well as their connotations. On the other hand, this study seeks to provide a new measurement tool in this context. This model was developed and validated on the basis of a mixed-methods study that included both qualitative and quantitative methods. The initial items used to measure competence were generated on the basis of behavioral event interviews. Exploratory factor analysis was conducted to develop a new theoretical framework and measurement tool on the basis of a cross-sectional survey, after which the results were verified by conducting confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). Subsequently, on the basis of the results of paired-sample t tests, further improvements were made to the model. Additionally, data regarding the initial reliability and validity of the tool were collected. This research was conducted in China in 2024 over a period of 9 months. Nine mentors and 3 postgraduates participated in the interviews, 15 mentors were consulted, and 662 respondents recruited from 5 Chinese universities completed the survey. A 5-factor competence iceberg model for academic medical postgraduates was developed. The five factors were labeled cooperation and communication ability (F1), experimental/research ability (F2), academic performance (F3), learning ability and moral adherence (F4) and practical ability (F5). These factors explained 69.13% of the total variance in the 26 items on which this research focused. The overall Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.943. The content validities of the overall scale and each item were good (UA-CVI = 0.83, Ave-CVI = 0.98, I-CVI ≥ 0.78). The model fit indices, which were obtained via CFA, were acceptable (χ2/df = 2.969, NNFI = 0.901, RMSEA = 0.077, CFI = 0.912, TLI = 0.901, SRMR = 0.057). The average variance extraction (AVE) values pertaining to the five factors on which this research focused were 0.656, 0.644, 0.670, 0.572 and 0.640 ( > 0.5), and the corresponding composite reliability (CR) values were 0.930, 0.915, 0.889, 0.870, and 0.877 ( ≥ 0.8), respectively. The results exhibited good reliability and validity as well as a good fit to the data. The competence iceberg model can help identify the competence needs of academic medical postgraduates that should be prioritized in the future, and the measurement tool, which exhibits strong reliability and validity, supports the future application of competence status and composition tests among medical students.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In line with the requirements of the “Health China 2030” blueprint, improving the competence of postgraduate students is an important component of efforts to reform medical education (Wang, 2021). In 1997, China established a medical postgraduate education program that combines both professional degrees and academic degrees, with the goal of training physician-scientists who engage in medical research as their main professional activity (Wu et al., 2014). As a bridge between science and medicine, physician-scientists are uniquely capable of innovating medical technology and improving global health care (Ganesh, 2021). However, shortages and attrition among trainees in this career path are becoming increasingly severe, an issue which may be explained by inadequate guidance during study, a lack of role models, and reduced interest in research (Garrison & Ley, 2022). One possible solution to this problem is to help these students identify their competence to become physician-scientists and provide them with relevant guidance.

Competence is a multidimensional concept that includes knowledge, skills, and attitudes and helps individuals successfully complete their professional tasks and achieve their job goals (Deist & Winterton, 2005). Core competence, which is the most important competence, can help individuals or organizations identify and develop advantages as soon as possible and win amid fierce competition (Holmes & Hooper, 2000). The evaluation of education plays an important role in the development of postgraduate medical education (Gibbs et al., 2006), but evaluations of academic postgraduate students often consider only their academic performance, thus overlooking other competencies. This is because competence is usually regarded as an intrinsic quality, whereas performance is the observable and concrete external manifestation or realization of competence (Cowan et al., 2005; Pikkarainen, 2014). Performance may involve quantifiable behaviors or short-term outcomes for the actor or a small group of people. However, these outcomes often have long-term impacts on a broader population, society, or field. Therefore, evaluation of the outcomes is complex and usually relies on a series of performances for reference (McLellan et al., 2007). Although competence itself is intangible and can be reflected only in performance, it is a necessary condition and foundation for individuals to achieve certain performance in professional tasks and, to a certain extent, determines the degree of successful performance; thus, there is no need to assess them separately (McMullan et al., 2003; Pikkarainen, 2014). Incorporating competence into education provides educators with a more multidimensional perspective on student development and equips them with useful tools to improve educational practice. Thus, in 2023, the World Federation for Medical Education proposed the establishment of an assessment system that includes postgraduates’ competence and performance with the aims of providing continuous feedback that can support their learning and helping identify low-performing students with the goal of providing them with strategies for improvement as early as possible (WFME, 2023). To achieve this goal, this study refers to the holistic conceptualization of competence, which includes knowledge, skills, attitudes, and performance in a competence model, to better understand the structure of competence and the relationship between competence and performance (McMullan et al., 2003).

A model is a simplified representation of a complex system in the real world. Its core function is to reduce the difficulty of understanding and to guide decision-making and practice (Becker et al., 2007; NATO, 2010). Models are usually classified into two categories: reference models and maturity models. A reference model is also referred to as a framework, which specifies the general elements needed to achieve organizational goals. A maturity model includes two subfunctional modules. The domain module contains a variety of criteria for dividing concepts into relatively independent domains (Pentek, 2020). The other assessment module can measure the organization’s status by scoring maturity stages for a set of constructs that outline a specific area of application (Merkus et al., 2020). With regard to the competence model in medical education, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) proposed the Milestones system, which provides a framework that can be used to evaluate residency training by reference to the following six core competencies: patient care, medical knowledge, professionalism, interpersonal and communication skills, practice-based learning and improvement, and systems-based practice (Edgar et al., 2020). All residents are regularly assessed for progress in these core competencies by the Clinical Competency Committee (CCC) (Andolsek et al., 2020). Other models that can be used to measure competence have also focused on healthcare workers, such as nurses and surgeons (Nilsson et al., 2020; Rekman et al., 2016). These competence models are used mainly to accelerate the development of clinical personnel and may not be suitable for the evaluation of postgraduate education for physician-scientists. Vanderbilt University proposed nine core competencies for physician-scientists. However, the development of such a competence framework is based on researchers’ experience, and assessment tools that can effectively track the development of postgraduates’ competence are lacking (L Estrada et al., 2022).

China has become a major player in postgraduate education; namely, in 2022, the number of graduate students on campus reached 3.65 million, which ranked second worldwide (Du, 2023). Although China’s Ministry of Education has issued comprehensive guidelines for postgraduates to obtain degrees, universities focus only on students’ research performance during the implementation process. Nearly all graduate students are required to publish one or more papers in indexed journals as first author before they graduate; thus, these students face great academic pressure, and guidance and help for medical postgraduates with regard to their development of core competence remain lacking at the organizational level (Cargill et al., 2018; Garrison & Ley, 2022). In this research field, a professional competence framework, including the domains of clinical practice, collaboration and communication, research, education, administration, professional development, and professional attitude, was developed for the Master of Nursing Specialist (MNS), which is a clinically oriented master’s degree program in China (Xu et al., 2022). Another recent study proposed a competence framework consisting of 23 competences integrated into seven roles to guide Chinese postgraduates in anesthesia training on the competencies they should possess with the aim of training anesthesiologists who are capable of providing high-quality health services (Zhang et al., 2025). Other competence models have been developed to present the clinical competencies needed by Chinese doctors (Wei et al., 2021; Zhao et al., 2015). Overall, previous literature on the competence model of medical postgraduates has focused primarily on the reference model (i.e., the competence framework of postgraduates), and on medical postgraduates who will engage in clinical work in the future. In contrast, research on medical academic postgraduates is insufficient. Thus, this study focus on what competencies medical academic postgraduates should possess, the proportion of and relationships among these competences, and ways of measuring the state of a given postgraduate’s competence. This study aims to develop an empirical model of core competence maturity, incorporating an evaluation function, for academic medical postgraduates. The model is designed to help postgraduates worldwide become the medical scientists of the future.

Methods

Design & setting

A mixed-methods study was conducted in three stages. First, we obtained competence items through face-to-face, semistructured interviews and revised them on the basis of expert consultation, as recommended by Lynn (Lynn, 1986). The quantitative method of exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was adopted to develop a new competence model with an evaluation function on the basis of a cross-sectional survey with a self-designed questionnaire. Finally, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was employed to verify the results, and the theoretical model was improved in combination with paired sample t tests.

This research was conducted in China in 2024 over a period of 9 months. During the qualitative phase, 9 mentors and 3 postgraduates participated in the interviews, and 15 mentors were consulted. During the quantitative phase, a cross-sectional survey was conducted, comprising both online and offline surveys completed by 662 respondents recruited from five Chinese universities.

Participants and sampling in the qualitative phase

Interview

The purposive sampling method was employed, and the accessibility of samples was considered to recruit medical mentors and postgraduates from Army Medical University and its affiliated hospitals in Chongqing, China, to participate in in-depth interviews. The selection criteria for mentors were as follows: 1) be a medical mentor for postgraduates with research degrees; 2) have 10 years or more of mentoring experience; 3) have mentored at least one student who has received a provincial-level excellent dissertation; 4) be in-service staff; and 5) willingness to participate in the survey. The exclusion criteria were as follows: 1) status as a medical mentor only for postgraduates with professional degrees; 2) fewer than 10 years of mentoring experience; 3) did not instruct students or who were mentored never received a provincial-level excellent dissertation; 4) retired or absent personnel; and 5) refusal to be interviewed. The inclusion criteria for postgraduates were as follows: 1) status as a medical academic postgraduate student; 2) be a postgraduate studying at the university with 6 months or more of study experience; and 3) willingness to participate in the survey. The corresponding exclusion criteria were as follows: 1) status as a professional postgraduate student; 2) status as a postgraduate at the university with less than 6 months of study experience; and 3) refusal to be interviewed. The number of interviewees was determined by the researcher according to the theoretical saturation of results that had been reached. The interviewees included 9 mentors and 3 postgraduates, which constituted a representative sample. All of the mentors were excellent graduate thesis supervisors who had exhibited outstanding academic performance, and their fields included basic medicine, preventive medicine, clinical medicine, pharmacy, nursing, and management.

Expert consultations

The sampling techniques, recruitment, and inclusion and exclusion criteria for the expert consultations were consistent with those used in the interviews with mentors, as described above. Additionally, we minimized potential bias in expert opinions by including female specialists, selecting experts with diverse professional backgrounds and departments, and recruiting experts from two major training institutions for medical academic postgraduates, namely hospitals and universities. Accordingly, no two experts were recruited from the same department, and repeated sampling of respondents was avoided. In each round, 3-10 more mentors were needed to evaluate the quality of the items obtained in the interviews and to make the necessary revisions until the experts reached a consensus on all of the items (Lynn, 1986). Ultimately, 15 mentors, including 12 males and 3 females, were involved in this process.

Participants and sampling in the quantitative phase

Both postgraduates and mentors participated in this phase. This study primarily employed the stratified convenience sampling method. Postgraduates and mentors were recruited separately to maintain a ratio of approximately 2:1. The postgraduate participants were further divided according to grade, degree type and gender, and the number of participants at each sublevel was balanced to the greatest extent possible. Postgraduates were required to meet the following criteria: 1) status as doctoral or master’s degree students in medicine or medical-related fields and 2) voluntary participation and provision of a signed informed consent form. Mentors were required to meet the following criteria: 1) current status as postgraduate mentors in medicine or medical-related fields and 2) voluntary participation and provision of a signed informed consent forms. The exclusion criteria used in this context were as follows: 1) students and mentors not affiliated with medicine or medical-related fields; and 2) failure to provide a signed informed consent form. A total of 934 people were recruited to participate in this survey, and 860 medical postgraduates and mentors ultimately participated, for a response rate of 92%.

Data collection in the qualitative phase

Interview

Behavioral event interviews (BEIs) are used mainly to develop competency models and to determine the core competencies that are needed to complete a job successfully; thus, this approach was used in this study to generate initial competency items (Dias & Aylmer, 2019). Additionally, the STAR technique (Situation, Task, Action, Result) was systematically applied to design the interview outline (see supplementary file 2) for mentors and postgraduates, respectively (Mulder, 2019). Specifically, the interview questions were organized into four sequential dimensions: 1) “Situation” (e.g., contextual factors like departmental resources and team collaboration), 2) “Task” (the postgraduate’s assigned responsibilities and challenges), 3) “Action” (concrete strategies adopted by the postgraduate interventions), and 4) “Result” (measurable outcomes and developmental trajectories). The interviews started with an overview of the respondents’ experience in postgraduate education and then focused on 1–2 events that impressed them deeply during the mentoring process; in this context, the STAR framework was used to elicit detailed behavioral examples. The details included the following. “Situation”: Describe the department, team, funds and platform during the postgraduate training period. “Task”: What was the main task or job that the postgraduate undertook? “Action”: What events, abilities, behaviors, or performances have impressed you about the postgraduate in completing these tasks? What specific actions did you take to guide them? What were you thinking or feeling at the time? “Result”: Developmental status or other results of the student. The interviews with the postgraduates were also based on the above STAR process to explore their views.

In total, 9 mentors and 3 postgraduates were interviewed 12 times in this study in January 2024, which lasted 563 minutes (see Table S1). Each person was interviewed once, and each interview lasted no less than 30 minutes. Two researchers conducted and audio-recorded each interview, using dual devices to ensure the integrity of the data. After the interviews were conducted, the interviewees’ personal information was collected through a structured paper questionnaire. The interviews continued until the researcher judged that the theory had reached saturation (Glaser & Strauss, 1967).

Expert consultations

Two rounds of consultations were held from March 29 to April 8 and April 18 to May 11, 2024, for a total of 15 consultations. One researcher was present at each counseling session, and a structured paper questionnaire was used to collect information. The questionnaire included a four-point Likert scale to measure the correlations between each item and the postgraduates’ competence, open questions pertaining to the revision comments for each item, and demographic information. All the information was supplied by the experts themselves. After the process was completed, a researcher recalled the questionnaire face-to-face and communicated with the experts regarding potential modifications to some items to ensure that the experts’ opinions were fully understood.

Data collection in the quantitative phase

A questionnaire, written in Chinese and consisting of 29 items, along with background information, was subsequently developed. All the items were based on the qualitative results and were scored on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = very unimportant, 2= unimportant, 3 = not sure, 4 = important, and 5 = very important). First, pilot testing was conducted at Army Medical University in May 2024; 150 questionnaires were distributed to postgraduates, and 70 questionnaires were distributed to mentors, for a completion rate of 83.6%. The overall Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.951, which indicated that the reliability of the questionnaire was good. The questionnaires were distributed on site with the assistance of administrators. During the questionnaire distribution process, respondents were informed in advance that if they had any questions about the items in the questionnaire, or if the survey required excessive time or caused any discomfort, they were asked to provide feedback to the administrators in time. After the survey, we obtained positive feedback from the respondents via the administrators; this information indicated that respondents could complete the questionnaire in between three and five minutes, that no resistance was encountered, that the questionnaire contained no incomprehensible or ambiguous indicators, and that no additional suggestions were provided. Therefore, we made no changes to the questionnaire.

A cross-sectional survey was subsequently conducted at universities throughout China from May 2024 to July 2024. Data were collected through onsite and online surveys and online electronic surveys via the online questionnaire platform Wenjuanxing. To recruit a larger target population to participate in the survey and obtain high-quality responses, we contacted the administrators of postgraduate education at these universities in advance and introduced the aim, content, confidentiality, and recruitment criteria and the number of participants we wanted to obtain for this study via WeChat, telephone, face-to-face settings or email. These administrators helped us distribute the questionnaires and ensure that enough responses were retrieved.

Finally, 860 questionnaires were obtained. The inclusion criteria for valid questionnaires were as follows: 1) demographic information met the predefined requirements; 2) all the items included in the questionnaires were completed in full, and the score values were different; and 3) signed informed consent was provided. Questionnaires that failed to meet one of the above criteria were excluded. Ultimately, 123 unqualified questionnaires were eliminated; of these, 121 were considered invalid because all of the answers were identical, 1 questionnaire did not include informed consent, and 1 questionnaire did not include personal information. Additionally, to ensure data quality, 75 questionnaires from 8 universities were deleted because the percentage of the sample size from these units was less than 5%. Thus, we obtained 662 valid responses for an effective recovery rate of 77%.

Data analysis in the qualitative phase

Within 24 hours after each interview, the interview recordings were converted into text. The text was then reviewed and revised by the two researchers who conducted the interviews until agreement was reached. The text was subsequently input into the SPSSAU program (2023) (SPSSAU (Version 23.0) [Online Application Software], retrieved from https://www.spssau.com) to conduct a content analysis of the interview documents and to extract keywords. Following a grounded theory approach (Corbin & Strauss, 2015), the keywords were merged independently by the two researchers using open coding, and cluster terms were obtained through axial coding. The next interview text was processed in the same way as described above, and the terms were combined with the previous research results through selective coding. Discrepancies were resolved through consensus discussions by the research team. Cohen’s Kappa coefficient (κ) was calculated to quantify the consistency between the two researchers (Landis & Koch, 1977). No new concepts emerged from the coding results of the last two interviews. After a team discussion, it was concluded that the theory had reached a state of saturation.

Data analysis in the quantitative phase

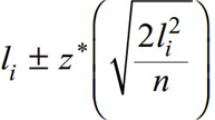

The SPSSAU program (2023) was used to conduct statistical analysis. Statistical methods of skewness and kurtosis were employed to check the normality of the data. EFA and CFA were used to develop and verify the tool. The 662 respondents were randomly divided into 2 groups, controlling for population category to obtain equivalent subsamples and to provide evidence of cross validity (Del Rey et al., 2021). The first group of data (n = 331) was used in the EFA, and the second set of sample data (n = 331) was employed in the CFA. The split sample size fully met the methodological requirements; i.e., the ratio of subjects to items was at least 5:1, and the total number of observations was not <100 (Gorsuch, 1983). In this study, the subsample size was increased to more than ten times the number of items (n > 290) with the aim of increasing the stability of the results. Additionally, multiple indicators were used to verify the reliability and validity of the evaluation tool, and paired sample t tests were performed to analyze the relationships among the factors extracted from the previous studies. A two-tailed p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant, which helped us develop the theoretical model.

Ethical consideration

The study was deemed exempt by the institutional review board of Army Medical University, as it falls under the exemption criteria specified in Article 32 of the regulation outlined in People’s Republic of China’s “Ethical Review Measures for Life Sciences and Medical Research Involving Humans”. The procedures used in this study adhere to the tents of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Results

Qualitative results

BEI results

The average age of the nine mentors was 52.2 ± 5.1 years, and their average tenure was 19.6 ± 7.0 years. The 3 postgraduates were all excellent students; their average age was 25.7 ± 2.3 years, and they covered three educational systems, including one eight-year program student, one master’s degree student and one doctoral student (see Table S2). In total, 127 keywords with word frequencies of 2 or more were extracted from the interview text (see Table S3). Ultimately, 31 items were formed and categorized into learning competence, practical competence, academic competence, or cooperation and communication competence on the basis of grounded theory.

Expert consultation results

In the first round of consultation, the average age of the 6 experts was 53.0 ± 10.4 years, and the average mentoring experience was 18.5 ± 9.4 years. In the second round, 9 experts (8 males and 1 female), with an average age of 53.9 ± 6.8 years and an average mentoring experience of 21.6 ± 10.2 years, were recruited (see Table S4).

After the 31 items obtained from the interview, the data were sent to six experts for the first round of review. We removed two indicators, namely, “Interdisciplinary collaboration to publish papers” and “Cross-unit collaboration to publish papers”, which these experts claimed were more suitable for describing the ability of mentors than that of postgraduate students. Additionally, Item 4, “Master the professional knowledge systematically”, and Item 17, “Obtained the achievements or awards”, were revised to “Master medical basic theory and professional knowledge systematically” and “Obtained academic awards or honors (such as scholarships, excellent dissertates, etc.)”, respectively, on the basis of the experts’ suggestions. These 29 items were subsequently sent to another nine experts for review, and the results revealed good content validity for the overall scale (UA-CVI = 0.83 and Ave-CVI = 0.98) and each item (I-CVI ≥ 0.78) (see Table S5) (Polit et al., 2007).

Quantitative results

Descriptive results and normality tests

The 662 respondents were from 5 Chinese universities. The respondents included 446 postgraduate students and 216 mentors, with a male-to-female ratio of approximately 2:1. The ratio of postgraduate students with professional and research degrees was approximately 1:1, covering all grades. Master’s students (n = 387) accounted for 86.8% of the sample, and doctoral students (n = 59) accounted for 13.2%. The mentors included 109 doctoral mentors and 107 master mentors, and 96.3% of them had associate senior academic titles or above (see Table 1). The majority of the participants were in clinical medicine (n = 355), which accounted for 53.6% of the sample, while the other participants were pursuing basic medicine, preventive medicine, pharmacy, medical technology, nursing and medical-related majors. All the data met the normality assumptions, as the skewness value of the 29 items did not exceed 3, and the kurtosis value did not exceed 10 (Avinç & Doğan, 2024), with the exception of Item 5.

EFA results

The Kaiser‒Meyer–Olkin (KMO) test and Bartlett’s test of sphericity were conducted first; the KMO value was 0.93, and Bartlett’s test was significant (p < 0.001), which indicates that the data were suitable for EFA. Common factors were extracted via varimax rotation. Item 5 was eliminated first because its communality was less than 0.4, indicating a very weak relationship between this factor and the study item. Items 6 and 14 were then eliminated for their cross-loading on two factors. Five factors were retained on the basis of the criterion of factor eigenvalues greater than 1 (Howard, 2016), and these factors explained 69.13% of the total variance in 26 items. Factors 1 to 5 accounted for 18.28%, 14.01%, 13.45%, 12.91% and 10.49% of this variance, respectively. The rotated component matrix is presented in Table 2. The five factors were defined according to the interpretation of the items that were primarily loaded on them: cooperation and communication ability (F1), experimental/research ability (F2), academic performance (F3), learning ability and moral adherence (F4) and practical ability (F5). The methods used to calculate these five factor scores and the total competence score are presented in Table 3.

CFA results and the relationships among the five factors

The CFA results revealed that all the factor loadings ranged from 0.650 to 0.900 ( > 0.6), indicating strong correlations between the items and the corresponding factors. The intercorrelation coefficients among the five factors ranged from 0.447 to 0.830 ( < 0.85), indicating little factor redundancy (Bynum et al., 2024). The fit of the five-factor model was good, which was evaluated by the following common fit indices (Hooper et al., 2008; Liu et al., 2020): the chi-square degrees of freedom ratio less than 3 (χ2/df=2.969), the nonnormed fit index (NNFI = 0.901), the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA = 0.077), the comparative fit index (CFI = 0.912), the Tucker‒Lewis index (TLI = 0.901), and the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR = 0.057). The CFA results and correlation coefficients among the factors are shown in Fig. 1.

Among the factors examined, the highest mean was observed for F4. Learning ability and morality (m = 4.62, sd = 0.47) followed by F2. Experimental/research ability (m = 4.56, sd = 0.52), F1. Cooperation and communication ability (m = 4.32, sd = 0.63), F5. Practical ability (m = 4.29, sd = 0.69), and F3. Academic performance (m = 4.08, sd = 0.78). The factors also met the normality assumption since the skewness values did not exceed 3 and the kurtosis values did not exceed 10 (Avinç & Doğan, 2024). The results of the paired-sample t tests (Table 4) revealed that there were significant differences among all pairs, with the exception of F1 and F5 (p = 0.208). Based on the above results, the classic competency iceberg model was adopted to visualize the competence of academic medical postgraduate students, with the importance of each competency increasing from the top to the bottom of the iceberg (see Fig. 2).

Reliability and validity examination

The overall Cronbach’s alpha was 0.943, and the values of the five factors were 0.923, 0.870, 0.891, 0.857 and 0.849 ( ≥ 0.70), indicating good reliability and internal consistency of the instrument (Taber, 2018). Additionally, the kappa coefficient (κ = 0.82, p < 0.001) indicates the interrater reliability of the interview data collection (McHugh, 2012). A modified kappa (k* > 0.74) reflects good interrater reliability for each item among the judges (see Table S5) (Polit et al., 2007).

According to the results of the expert consultation, the overall scale (UA-CVI = 0.83 and Ave-CVI = 0.98) and 26 items (I-CVI ≥ 0.78) exhibited good content validity (Polit et al., 2007). For structural validity, the five-factor average variance extraction (AVE) test results were 0.656, 0.644, 0.670, 0.572 and 0.640 ( > 0.5), and the composite reliability (CR) test results were 0.930, 0.915, 0.889, 0.870, and 0.877 ( ≥ 0.8), indicating good convergent validity (Sharka, 2024). The square root of the AVE values was greater than the Pearson correlation coefficient matrix among the variables, thus indicating good discriminant validity of each factor (see Table 5) and that the internal structure of the instrument was good (Sharka, 2024).

Discussion

In this study, we used a mixed approach combining qualitative and quantitative methods to design and develop a new core competence theoretical framework and scale and collected the main psychological characteristics of the scale to support its future use in postgraduate medical students.

Although CBME has attracted much attention in the field of medical education worldwide, its focus has always been on the performance of medical students in the clinical environment, whereas medical postgraduates in the academic environment have been overlooked (Acai et al., 2021; Premila D. Leiphrakpam & Chandrakanth Are, 2023). Moreover, the complexity of competence assessment and the lack of tools present serious challenges to the implementation of CBME (Sulaiman Alharbi, 2024). However, our research presents a maturity model with two submodules: the domain module, which identifies the core competence dimensions, relationships and standards necessary for academic medical postgraduates to perform effectively, and the evaluation module, which offers a tool to quantitatively measure competencies to facilitate the evaluation, detection, and exploration of their constructive effects.

The competence iceberg model includes five factors and explains 69.13% of the total variance. Values ranging 40% to 60% are considered to be sufficient with respect to the total variance explained for multifactorial structures in the social sciences (KARATEPE & AKAY, 2023). The total variance explained by this model is greater than the corresponding figures that have been reported in other competence studies in the field of medicine (61 ~ 68%) (Gong et al., 2024; Tuomikoski et al., 2018), thus indicating that the five factors included in this model effectively capture the latent structure among the 26 items and that the model can be used to measure core competence among academic medical postgraduates. The five factors thus identified are cooperation and communication ability (F1), experimental/research ability (F2), academic performance (F3), learning ability and moral adherence (F4) and practical ability (F5), which cover all of the competencies included in the competence framework proposed by the ACGME and Vanderbilt University, with the exception of patient care and mentoring/teaching (Edgar et al., 2020; L Estrada et al., 2022). Medical professionals working in the clinical or teaching fields should have the competence to care for patients and instruct them in teaching, but Chinese medical academic postgraduates may not have this ability, and their careers tend to focus mainly on medical research. Furthermore, the four domains of F1, F2, F4 and F5 in the iceberg competence model are consistent with other studies from China (Xu et al., 2022), while academic performance (F3) is unique. Specifically, unlike other studies that focus on clinical practice and doctor‒patient relationships in medical services and healthcare, the iceberg model reflects the practical ability of research to target medical needs, has transformative application value, and focuses more on academic collaboration and the relationship between mentors and postgraduates. Additionally, both of these studies place clinical competence at the top of the list based on expert opinions without data verification (Xu et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2025). However, in the iceberg model, learning ability and moral adherence occupy the most significant position among all abilities. The iceberg model can also be used for competence measurement and evaluation, although these studies do not address this aspect.

Additionally, the competency iceberg offers several unique advantages, including the ability to visualize both visible performance and hidden competence of medical postgraduates, in addition to the proportions and relationships among the five components. Performance is considered to be an external manifestation of competence that is easily seen and measured. The relationship of competence and performance is like that of an iceberg and its visible peak, but it is worth noting that what kind of peak is visible at any time depends on the changing educational environment (Pikkarainen, 2014). The current evaluation of academic medical postgraduates focuses mainly on academic performance, and several objective indicators have been developed to measure this factor (Chen et al., 2024). This aspect resembles the visible part of an iceberg that lies above the sea. However, other important abilities are overlooked, just as we cannot see the part of the iceberg that lies below the surface of the sea; accordingly, we situate these abilities in the hidden part of the iceberg to attract more attention. This finding suggests that, in addition to focusing on performance, we should focus on the competence associated with the hidden part of the iceberg and develop more indicators and methods that can be used in such evaluations, so that the hidden part can float more to the surface and become visible.

What might this research entail? First, the competency iceberg may lead to the development of a CBME curriculum targeting medical academic postgraduate training, although this reform has already been implemented in many residency programs (Railer et al., 2020). Specifically, with respect to cooperation and communication ability in the hidden part of the iceberg, we did not find any courses matching this ability in the previous literature (Xue Jia et al., 2023), which should be considered a supplement to the new curriculum system (e.g., cooperative spirit, norms and skills-related courses (Chen et al., 2024).

Second, the competency iceberg suggests that the evaluation of the academic performance of medical postgraduates may be more diverse, including not only papers but also awards, patents and funds. This can provide insights into the reform of postgraduate education in countries that pay excessive attention to publications or even use such publications as the main standard of graduation (Zhu et al., 2014). Moreover, the ability located at the bottom of the iceberg is the foundation of academic performance, which also provides novel ways of improving academic performance.

Third, our scale provides information about the competence level of academic medical postgraduates and how this level differs across groups (e.g., according to gender, grade, educational background, major and university) and the relevant competency composition. Such information is likely to inspire further research questions (e.g., “Why do certain demographic groups have higher competence than others?”), highlight targets for differentiated training methods for academic medical postgraduates, and suggest the prioritization of resource deployment (e.g., to the regions with the lowest reported competency). Environments in which competency is high may serve as examples from which useful information could be obtained from follow-up assessments.

Fourth, the scale may be used to measure the impact of interventions that are intentionally designed to improve competence among academic medical postgraduates. For example, capacity status is used as a baseline, similarly assessed via a scale after a certain intervention (e.g., a CBME course program), whereas competency status can be assessed multiple times at intervals to track changes over time, thus providing more conclusive evidence for these medical education reform outcomes.

Finally, this research has practical application value for medical educators. For example, it can help mentors reflect on the rationality of the content and method of education for postgraduates, the relationships among them, and the ability status of postgraduates; furthermore, it can even promote active and highly participatory dialog between them. Such interactions may enhance postgraduates’ perceptions of their own abilities, support productive learning and help them when they encounter difficulties (Hennessy et al., 2023).

Limitations of this study

The study focused only on medical postgraduates in China, and some items in this model were influenced by the postgraduate education system that characterizes this country, including in terms of the requirements for publications and the traditional culture associated with mentorship, which resembles a “father and son” relationship (Chen et al. 2025). Therefore, verification is needed to support the use of this tool in other countries. Our study is limited by the inclusion of only medical students, predominantly at the master’s level, which may undermine its generalizability and bias the results. The results of this study were based on a cross-sectional survey, and longitudinal analyses may be conducted in the future to help researchers explore relevant trends in the development of competence and the corresponding requirements (Škrinjarić, 2022). Additionally, scales are usually used to survey target attitudes and perceptions at the surface level (Kirkpatrick & Kirkpatrick, 2016), and the results can deviate because people generally respond in a way that enables them to present themselves in a more favorable light (Paulhus & Vazire, 2007). Thus, interviews, focus groups and other methods can be combined, and information can be collected both directly from postgraduates and from their mentors in practice, thus strengthening the multidimensional evaluation of competence and reducing bias in estimating their effects on individual development outcomes (Kirkpatrick & Kirkpatrick, 2016). Finally, it is necessary to consider the application of the competence model in reality, which requires support from managers and a series of top-down reforms, including with regard to systems, platforms, curricula, and cultures. Without a supportive environment, this approach may be difficult to implement in practice, and its effect may be limited or even ineffective.

Conclusion

Competence is the foundation of individual performance, and the performance orientation of management may contribute to the realization of the organization’s expected outcome. Given the influential role of competence in the performance and outcomes of medical postgraduates, we must understand which competences are key and how to measure them. In this study, a competence iceberg model consisting of five factors—cooperation and communication ability (F1), experimental/research ability (F2), academic performance (F3), learning ability and moral adherence (F4) and practical ability (F5)—from 26 items was developed and validated. We hope that these findings can provide a deeper understanding of the content and structure of the core competencies of academic medical postgraduates and that the collection and analysis of quantitative information concerning these competencies described in this context can provide teaching, learning and management strategies that can improve the development of medical postgraduates and medical education as a whole.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Acai A, Cupido N, Weavers A, Saperson K, Ladhani M, Cameron S, Sonnadara RR (2021) Competence committees: The steep climb from concept to implementation. Med Educ 55(9):1067–1077

Andolsek K, Padmore J, Hauer KE, Ekpenyong A, Edgar L, & Holmboe E (2020) Clinical competency committees: a guidebook for programs. ACGME Retrieved from https://www.acgme.org/globalassets/ACGMEClinicalCompetencyCommitteeGuidebook.pdf

Avinç E, Doğan F (2024) Digital literacy scale: Validity and reliability study with the Rasch model. Educ Inf Technol 29(17):22895–22941

Becker J, Delfmann P, & Knackstedt R (2007) Adaptive Reference Modeling: Integrating Configurative and Generic Adaptation Techniques for Information Models. In J. Becker & P. Delfmann (Eds.), Reference Modeling: Efficient Information Systems Design Through Reuse of Information Models (pp. 27-58). Physica-Verlag HD. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-7908-1966-3_2

Bynum WE, Dong T, Uijtdehaage S, Belz F (2024) Development and initial validation of the shame frequency questionnaire in medical students. Acad Med 99(7):756–763

Cargill M, Gao X, Wang X, O’Connor P (2018) Preparing Chinese graduate students of science facing an international publication requirement for graduation: adapting an intensive workshop approach for early-candidature use. Engl Specif Purp 52:13–26

Chen G, Yan W-W, Wang X-Y, Lu X, Yu H, Ni Q, & Yue J-J (2025) The influence of mentorship on medical postgraduates’ academic impact: evidence from China. Studies in Higher Education, 1-18. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2025.2464159

Chen G, Yan W-W, Wang X-Y, Ni Q, Xiang Y, Mao X, Yue J-J (2024) The relationship between coauthorship and the research impact of medical doctoral students: a social capital perspective. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11:1256

Corbin JM, & Strauss AL (2015).Basics of qualitative research: techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (Fourth edition. ed.). SAGE

Cowan DT, Norman I, Coopamah VP (2005) Competence in nursing practice: a controversial concept – A focused review of literature. Nurse Educ Today 25(5):355–362

Deist FDL, Winterton J (2005) What is competence? Hum Resour Dev Int 8(1):27–46

Del Rey R, Ojeda M, Casas JA (2021) Validation of the sexting behavior and motives questionnaire. Psicothema 2(33):287–295

MdO Dias, Aylmer R (2019) Behavioral event interview: sound method for in-depth interviews. Oman Chap Arab J Bus Manag Rev 8(1):1–6

Du Q. (2023). China had 3.65 million graduate students on campus in 2022, ranking second in world. Global Times. https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202312/1303931.shtml

Edgar L, McLean S, Hogan SO, Hamstra S, & Holmboe ES (2020) The milestones guidebook. Version 2020. ACGME Retrieved from https://www.acgme.org/globalassets/MilestonesGuidebook.pdf

Ganesh K (2021) The joys and challenges of being a physician–scientist. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 18:365

Garrison HH, Ley TJ (2022) Physician-scientists in the United States at 2020: Trends and concerns. FASEB J 36(5):e22253

Gibbs T, Brigden D, Hellenberg D (2006) Assessment and evaluation in medical education. South Afr Fam Pract 48(1):5–7

Glaser BG, & Strauss AL (1967) The discovery of grounded theory: strategies for qualitative research. Aldine, Chicago. Taylor and Francis

Gong X, Zhang X, Zhang X, Li Y, Zhang Y, Yu X (2024) Developing a competency model for Chinese general practitioners: a mixed-methods study. Hum Resour Health 22(1):31

Gorsuch RL (1983).Factor Analysis (2nd ed.). Psychology Press. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203781098

Hennessy S, Calcagni E, Leung A, Mercer N (2023) An analysis of the forms of teacher-student dialogue that are most productive for learning. Lang Educ 37(2):186–211

Holmes G, Hooper N (2000) Core competence and education. High Educ 40:247–258

Hooper D, Coughlan J, Mullen MR (2008) Structural equation modelling: guidelines for determining model fit. Electron J Bus Res Methods 6(1):53–60

Howard MC (2016) A review of exploratory factor analysis decisions and overview of current practices: what we are doing and how can we improve? Int J Hum-Comp Interact 32:51–62

KARATEPE R, AKAY C (2023) Key competencies inventory development study for high school students. J Kesit Acad 9(34):1–37

Kirkpatrick JD, & Kirkpatrick WK (2016). Kirkpatrick’s four levels of training evaluation. Association for Talent Development. https://books.google.com.sa/books?id=mo--DAAAQBAJ

Estrada L, Williams MA, Williams CS (2022) A competency‑guided approach to optimizing a physician‑scientist curriculum. Med Sci Educ 32(2):523–528

Landis JR, Koch GG (1977) The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 33(1):159–174

Liu Y, Yin Y, Wu R (2020) Measuring graduate students’ global competence: Instrument development and an empirical study with a Chinese sample. Stud Educ Eval 67:100915

Lynn MR (1986) Determination and quantification of content validity. Nurs Res 35(6):382–385

McHugh ML (2012) Interrater reliability: the kappa statistic. Biochem Med (Zagreb) 22(3):276–282

McLellan AT, Chalk M, Bartlett J (2007) Outcomes, performance, and quality—What’s the difference? J Subst Abus Treat 32(4):331–340

McMullan M, Endacott R, Gray MA, Jasper M, Miller CML, Scholes J, Webb C (2003) Portfolios and assessment of competence: a review of the literature. J Adv Nurs 41(3):283–294

Merkus J, Helms R, & Kusters R (2020) Reference Model for Generic Capabilities in Maturity Models Proceedings of the 2020 12th International Conference on Information Management and Engineering, Amsterdam, Netherlands. https://doi.org/10.1145/3430279.3430282

Mulder P (2019) Behavioral Event Interview (BEI). Toolshero. https://www.toolshero.com/human-resources/behavioral-event-interview-bei/

NATO. (2010). Guide to Modelling & Simulation (M&S) for NATO Network-Enabled Capability (‘M&S for NNEC’). N. RTO. https://www.sto.nato.int/publications/STO%20Technical%20Reports/RTO-TR-MSG-062/$$TR-MSG-062-ALL.pdf

Nilsson J, Johansson S, Nordström G, Wilde-Larsson B (2020) Development and validation of the ambulance nurse competence scale. J Emerg Nurs 46(1):34–43

Paulhus DL, & Vazire S (2007) The self-report method. In R. W. Robins, R. C. Fraley, & R. F. Krueger (Eds.), Handbook of Research Methods in Personality Psychology (pp. 224–239). Guilford Press

Pentek T (2020). A Capability Reference Model for Strategic Data Management University of St. Gallen]. St. Gallen, Switzerland. https://svn.alexandria.unisg.ch/EDIS/Dis5009.pdf

Pikkarainen E (2014) Competence as a key concept of educational theory: a semiotic point of view. J Philos Educ 48(4):621–636

Polit DF, Beck CT, V.Owen S (2007) Is the CVI an acceptable indicator of content validity? Appraisal and recommendations. Res Nurs Health 30(4):459–467

Premila D. Leiphrakpam, & Chandrakanth Are (2023) Competency‑Based Medical Education (CBME): an Overview and Relevance to the Education of Future Surgical Oncologists. Indian J Surg Oncol, 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13193-023-01716-w

Railer J, Stockley D, Flynn L, Hastings-Truelove A, Hussain A (2020) Using outcome harvesting: assessing the efficacy of CBME implementation. J Eval Clin Pr 26(4):1132–1152

Rekman J, Hamstra SJ, Dudek N, Wood T, Seabrook C, Gofton W (2016) A new instrument for assessing resident competence in surgical clinic: the Ottawa clinic assessment tool. J Surgical Educ 73(4):575–582

Sharka R (2024) Psychometric properties of the Arabic version of the perceived prosthodontic treatment need scale: exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses. PLoS One 19(2):e0298145

Škrinjarić B (2022) Competence-based approaches in organizational and individual context. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 9:28

Sulaiman Alharbi N (2024) Evaluating competency-based medical education: a systematized review of current practices. BMC Med Educ 24:612

Taber KS (2018) The use of Cronbach’s Alpha when developing and reporting research instruments in science education. Res Sci Educ 48:1273–1296

Tuomikoski A-M, Ruotsalainen H, Mikkonen K, Miettunen J, Kääriäinen M (2018) Development and psychometric testing of the nursing student mentors’ competence instrument (MCI): a cross-sectional study. Nurse Educ Today 68:93–99

Wang W (2021) Medical education in China: progress in the past 70 years and a vision for the future. BMC Med Educ 21:453

Wei Y, Wang F, Pan Z, Wang M, Jin G, Liu Y, Lu X (2021) Development of a competency model for general practitioners after standardized residency training in China by a modified Delphi method. BMC Fam Pract 22(1):171

WFME (2023) WFME global standards for quality improvement of medical education. The 2023 revision. WFME Retrieved from https://wfme.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/WFME-STANDARDS-FOR-POSTGRADUATE-MEDICAL-EDUCATION_2023.pdf

Wu L, Wang Y, Peng X, Song M, Guo X, Nelson H, Wang W (2014) Development of a medical academic degree system in China. Med Educ Online 19(1):23141

Xu H, Dong C, Yang Y, Sun H (2022) Developing a professional competence framework for the master of nursing specialist degree program in China: a modified Delphi study. Nurse Educ Today 118:105524

Jia Xue, Zhu Yuyi, Zhong Xuelian, Wen Qiao, Wang Deren, Xu Mangmang (2023) The attitudes of postgraduate medical students towards the curriculum by degree type: a large-scale questionnaire survey. BMC Med Educ 23:869

Zhang X, Meng K, Cao J, Chen Y (2025) Development of competency framework for postgraduate anesthesia training in China: a Delphi study. BMC Med Educ 25(1):9

Zhao L, Sun T, Sun B-Z, Zhao Y-H, Norcini J, Chen L (2015) Identifying the competencies of doctors in China. BMC Med Educ 15(1):207

Zhu Y, Zhang C-J, Hu C-L (2014) China’s postgraduate education practices and its academic impact on publishing: is it proportional? J Zhejiang Univ Sci B 15:1088–1092

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank all the participants involved in this study. This work was supported by the National Social Science Foundation of China [grant numbers 25BKX016], the Postgraduate Education Reform Foundation of Chongqing [grant numbers YJG233151], the Research Project of Graduate Education and Teaching Reform in Army Medical University [grant numbers Y2025B01], and the Social Science Planning Project of Chongqing [grant numbers 2023PY59].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J-J Y: conceptualization, investigation, data curation, formal analysis, project administration, funding acquisition, writing - original draft, writing - review & editing. R H: investigation, data curation, formal analysis. J Y: data curation, formal analysis, funding acquisition. B X: investigation, data curation. L L: investigation, data curation. L C: investigation, data curation. G C: conceptualization, investigation,formal analysis, funding acquisition, writing - original draft, writing - review & editing. Y-C W: conceptualization, project administration, writing - review & editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. As per the regulations outlined in “Ethical Review Measures for Life Sciences and Medical Research Involving Humans” (National Health Commission, Ministry of Education, Ministry of Science and Technology, and National Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine of People’s Republic of China, No. 4 [2023]), this study falls under the exemption criteria specified in Article 32 of the regulation. Therefore, this study was deemed exempt by the Institutional Review Board of Army Medical University as it met the following conditions: 1) The study did not cause harm to participants and did not involve commercial interests; 2) The data used in this study is completely anonymous and does not involve any personal identifiers or sensitive information (exemption approval date: March 3, 2023). The full text of the regulation is available at [https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/2023-02/28/content_5743658.htm?ivk_sa=1023197a].

Informed consent

Written or onlined informed consent was obtained from all participants between January and July 2024. Before any data collection commenced, participants were required to read and confirm the informed consent form. This form explicitly stated that participation in the study was entirely voluntary, participants’ information and responses would be confidential and anonymous, and the research findings would be used solely for academic purposes.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yue, JJ., Huang, R., Yang, J. et al. Academic medical postgraduates: a competence iceberg model and measurement development. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 13, 25 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-06371-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-06371-w