Abstract

Simplification is a feature of translation universals that has been extensively explored in translation studies. In relation to interpreting, however, recent studies have predominantly focused on a single level and on languages from the Indo-European family, which raises the question of whether the simplification hypothesis holds across different language levels and pairs. In this study, we investigate the simplification hypothesis by using the machine learning technique of ensemble learning to perform a classification experiment comparing interpreted and spoken Chinese. Specifically, we calculate the linguistic complexity borrowed from multiple disciplines, evaluate the characteristics of the two language modes, and apply ensemble learning for classification. We find that interpreted Chinese can be distinguished from spoken Chinese at lexical, syntactic, and combined levels, with classification accuracies of 89.39%, 98.94%, and 99.20%, respectively. However, our further finding that interpreted Chinese exhibits lexical simplification and syntactic complexification suggests a dynamic interplay between syntactic and lexical complexity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the field of translation studies (TS), there is extensive ongoing discussion about ontology, which means the status of a text with and without translation (i.e., mediation) (Baker, 1995, 1996; Chesterman, 2017; Xu and Li, 2024). Currently, researchers in translation and interpreting studies are interested in exploring the distinctive characteristics that differentiate translated (Kruger and Van Rooy, 2016; Liu et al., 2021; Wang and Liu, 2024) and interpreted (Liu et al., 2023; Xu and Liu, 2023) texts from native language texts. The distinctive linguistic feature of simplification, which was first examined in corpus-based translation studies, refers to the tendency of translations to be less complex in lexical and syntactic structure than their original texts (Baker, 1993, 1996). In the domain of interpreting, studies of simplification have been inconclusive. In corpus-based interpreting studies, most studies have adopted the method of quantifying lexical (Russo et al., 2006; Xu and Li, 2022) or syntactic (Liu et al., 2023; Xu and Liu, 2023; Wang et al., 2024a) indices to compare interpreted and spoken texts, which raises the issue of whether and how simplification is exhibited when different levels of language interact.

Text classification is a fundamental task in natural language processing (NLP) involving assigning predefined categories or labels to text documents, and it is commonly applied in the computational field. Much research in TS has adopted text classification to differentiate between translated and non-translated texts in Indo-European languages (Baroni and Bernardini, 2006; Ilisei et al., 2010; Volansky et al., 2015; Wang and Liu, 2024). However, there is little similar research on Chinese despite its ascent to a global language. The primary focus is mainly on translated and non-translated Chinese. “Translated Chinese” as Chinese texts that are translated from other languages into Chinese, while “non-translated Chinese” refers to original texts written in Chinese by native speakers. For example, Hu et al. (2018) presented the first quantitative investigation of the classification of translated and non-translated Chinese at the syntactic level. Later, the same authors comprehensively investigated translated Chinese by examining universal features of translation, including explicitation, simplification, normalization, and interference (Hu and Kübler, 2021). Another trend in machine learning is the use of ensemble learning techniques to elevate classification accuracy. In TS, for instance, Wang et al. (2024b) used an ensemble classifier to compare translated and non-translated corporate annual reports through syntactic indices and achieved an accuracy of 97%.

The present work investigates simplification features that distinguish interpreted from non-interpreted Chinese by conducting a classification experiment through ensemble learning. The significance of classifying spoken and interpreted Chinese texts has practical applications in several areas. Language service providers can quickly identify linguistic differences in interpreted texts to assess quality standards (Xu et al., 2023). Educators and students can analyze interpreted texts’ linguistic features (Fan et al., 2025) for targeted feedback and training. This research also contributes to computational linguistics by providing insights into detecting interpretese (Huang et al., 2025). Given these practical applications, the rationale for adopting machine learning, particularly ensemble learning techniques, becomes even more compelling. It offers several advantages over traditional corpus-based approaches. Traditional methods often rely on manual annotation and statistical analysis, which can be time-consuming and may not capture complex patterns in large datasets. Machine learning can automatically identify patterns and association in data, handle large volumes of text efficiently, and provide more nuanced insights into linguistic phenomena. For example, ensemble learning combines multiple algorithms to improve classification accuracy and robustness, which is particularly useful to study the simplicity/complexity spectrum in language (François and Lefer, 2022).

The remainder of the research is organized as follows. Section “Related work” reviews the TIS literature with a focus on the features that have been explored and the machine learning methods underpinning our study. Section “Data and method” presents the corpus compiled for this study and its two sub-corpora. Section “Results and discussion” reports on the machine learning experiments performed to differentiate between interpreted and original texts, with the objective of identifying the discriminative features of interpretation compared with translation. We begin with a set of Chinese-based features, drawing from previous work (Hu and Kübler, 2021; Hao et al., 2024), that have been built mainly from English (Volansky et al., 2015). Then, we compare our findings with related earlier studies and discusses the implications of our results for the simplification hypothesis. Section “Conclusion” provides some concluding remarks.

Related work

In this section, we review the literature from two perspectives. The first is predominantly linguistic, focusing on the simplified features of translated and interpreted texts. These features can manifest across various linguistic levels and are therefore sufficiently robust to stand as a probable interpreting universal (Lv and Liang, 2019). The second is more computational, addressing the methodologies as well as techniques for analyzing or leveraging the linguistic characteristics. Our review includes researches which have leveraged a corpus and applied machine learning techniques, with an emphasis on recent advancements in computational research. It thus forms the foundation of our experimental endeavors and identifies the research gap leading to our research questions.

Studies on simplification

Simplification is a frequently tested candidate among translation universals (TUs) and reflects the intention of translators to use simplified language or message during the translation process. Baker’s (1996) argument that simplification occurs subconsciously sparked a wealth of research dedicated to understanding the phenomenon. Chesterman (2004) distinguished T-Universals, which emphasize distinctions between translations and similar non-translated texts, from S-Universals, which capture differences between translations and their original texts. Among the four TUs proposed by Baker (1996), explicitation is considered as a possible S-Universal, while simplification is regarded as a typical T-Universal. Delaere et al. (2012:237) pointed out that since simplification is a T-Universal, it has been most commonly but not solely examined in relation to non-translated texts.

The phenomenon of translational simplification, especially at the lexical level, has been largely supported by empirical research. Various definitions have been proposed for lexical simplification, such as “using fewer words” (Blum-Kulka and Levenston, 1987), substituting formal words with informal ones (Vanderauwera, 1985), and the observation of a lower type-token ratio in translated texts (Cvrček and Lucie, 2015; Feng et al., 2018). Laviosa (2002) found evidence of lexical simplification in translations compared to non-translated texts using the Translational English Corpus and a similar corpus in the same genre. Lower lexical density and a limited word range are characteristics of this lexical simplification. The ratio of grammatical to content words is used to calculate lexical density. Despite extensive research, however, there is no consistent evidence supporting simplification. Various linguistic features have been identified that contradict the simplification hypothesis. These features include longer mean sentence length (Laviosa, 1998), atypical collocations (Mauranen, 2006), as well as a higher frequency of modifiers (Jantunen, 2004). Xiao and Yue (2009) found that translated Chinese fiction has a significantly higher average sentence length than native Chinese fiction, which suggests that mean sentence length is not a reliable indicator for predicting simplification in translated texts. Xiao (2010) also found that translated Chinese has a lower lexical density than native Chinese, but there is no significant difference in mean sentence length, indicating that mean sentence length might be genre-sensitive. By comparing translated English texts with local texts using the quantitative linguistics metrics of mean dependency distance (MDD) and dependency direction, Fan and Jiang (2019) brought about a change in study approach. Their results suggested that translated writings may be more structurally complicated since the MDD of translated materials is noticeably longer than that of English texts that have not been translated.

In the realm of interpreting, simplification studies have been inconclusive. In order to investigate simplification tendencies, the majority of research has focused on lexical indices, such as lexical density, core vocabulary, and list heads. In order to determine if the simplification phenomena seen in written translation may also be found in interpreted language, Sandrelli and Bendazzoli (2005) used the European Parliament Interpreting Corpus (EPIC). The findings largely confirmed Laviosa’s simplification patterns (1998) in interpreted English, although these patterns varied across different language combinations. Kajzer-Wietrzny (2012) detected simplification only in the metric of list heads, not in other indices, and warned the results could be influenced by the language pair as well as the delivery mode of the source text. Bernardini et al. (2016) compared the translation and interpretation of identical source texts and discovered that the mediation process led to a reduction in lexical complexity, with interpreters simplifying the message to a greater extent than translators. Additionally, they observed that translated Italian showed more lexico-syntactic simplification while translated English showed a higher degree of lexical simplification. According to Ferraresi et al. (2018), who looked at the lexical features of English translations and interpretations from different source languages, the source language may have a greater impact on the degree of simplification than the mediation method. Lv and Liang (2019) analyzed Chinese-to-English interpreting and found that consecutive interpreting (CI) exhibited a more simplified pattern than simultaneous interpreting (SI) across multiple simplification indices, suggesting the cognitive load in CI is the same as or even higher than that in SI.

Syntactic complexity is regarded as a more reliable feature for examining simplification as it offers a more profound recognition of the interpreting process. Xu and Li (2022) proposed that syntactic complexity could serve as a feature of how much interpreted language deviates from other language types, like L2 speaking as well as L1 speaking. Liu et al. (2023) analyzed 14 syntactic parameters to evaluate the degree of syntactic complexity in three types of language: interpretation, L1 spoken text, and L2 spoken text. Their results corroborate the simplification hypothesis, showing that “constrained” language (i.e., interpretation and L2 spoken text) is less syntactically complex than “unconstrained” language (i.e., L1 spoken text), with interpreted text being the simplest of three. Xu and Liu (2024) compared the MDD of English speech from native speakers, non-native speakers, and interpreters and found that interpreted speech has the lowest syntactic complexity, probably because of the high cognitive load of SI. They also found that the word order of interpreted speech is distinct from that of native speech.

Text classification through machine learning

A pioneering study in text classification using machine learning was Baroni and Bernardini’s (2006) exploration of the distinction between translated and original Italian texts. Using word/lemma/parts-of-speech n-grams and mixed representations, they achieved an F-measure of 86% via recall-maximizing combinations of support vector machine (SVM) classifiers. Their findings demonstrated that function word distributions and shallow syntactic patterns without lexical information could effectively characterize translated text. Ilisei et al. (2010) investigated the universals of simplification in translated Spanish by using various ML algorithms to classify translated and non-translated texts. They found that all classifiers became more accurate with the inclusion of simplification features, with SVM showing the greatest improvement in accuracy, from 73.65% to 81.76%. Volansky et al. (2015) carried out an extensive investigation into translationese in English, analyzing both original and translated English from 10 different source languages within a corpus from the European Parliament. Their main objective was to examine translational universals, including simplification and explicitation. The classification accuracy achieved using SVMs with features such as part-of-speech trigrams (98%), function words (96%), and function word n-grams (100%) further demonstrated function words and surface syntactic structures are adequate for identifying translated text. Rubino et al. (2016) addressed the challenge of distinguishing between human translations and original texts, focusing on differentiating outputs of novice and professional translators. They proposed a feature set inspired by quality estimation and information density and used SVM for classification. Their study found that combining surface, surprisal, complexity, and distortion features yielded the highest accuracy, although surprisal features were ineffective in differentiating professional and student translations. Habic, Semenov, and Pasiliao (2020) applied deep-learning techniques to ascertain whether texts were authored by native or non-native speakers. Their specialized deep neural network achieved a peak accuracy of 88.75%, stressing the efficacy of deep learning in language processing. Liu et al. (2022a) investigated the potential of ML techniques to distinguish between original and translated Chinese texts. They used seven entropy-based metrics and four ML models (SVM, linear discriminant analysis, random forests, and multilayer perceptron) to classify a balanced Chinese comparable corpus. Their findings suggest that combining Shannon’s entropy indicators with ML offers an effective method for analyzing translation as a distinct communicative activity, with SVM achieving an accuracy rate of 84.3%. Wang et al. (2024b) used machine learning to classify corporate annual reports as translated or non-translated in Chinese. Syntactic complexity indices and information entropy were adopted as measures of the complexity of syntactic rules. The highest-performing of the eight algorithms used in the study achieved an accuracy of 97%, contributing to text classification and TS by showing that syntactic features can effectively classify translational language.

Among the Chinese studies, Xiao and Hu (2015) built a comparable corpus of 500 original and translated Chinese texts across four genres. They leveraged statistical tests to identify differences in lexical features and found translated texts used significantly more pronouns than original texts. They did not investigate the syntactic contexts of these overused pronouns, but their study highlighted the need for further exploration of syntactic features in Chinese translationese. Hu et al. (2018) applied ML to distinguish between translated and original Chinese texts, focusing on syntactic features. Using SVMs, they achieved accuracy of over 90% without lexical information, highlighting syntactic differences in translated Chinese. Hu and Kübler (2021) examined the unique features of Chinese translationese and its variations based on source languages. They found that Chinese translations can be distinguished from original texts and that each source language leaves distinct traces, such as noun repetition and pronoun use, in translation. Their study highlights the importance of syntactic features in identifying these differences in Chinese translations. Wang et al. (2024a) classified translated and non-translated Chinese texts through analyzing syntactic rule complexity through information entropy and machine learning. They found translated texts exhibit higher syntactic complexity than non-translated ones, shedding light on translation’s effects on language syntax.

Research questions

The above literature review shows that simplification in TIS is a complex, context-dependent feature. Interpreting studies of simplification have produced mixed results, and multi-level linguistic analysis is required beyond the focus on single lexical or syntactic differences. Similarly, the capability of text classification to differentiate translated from non-translated texts has advanced through the use of machine learning with ensemble models and alternative classifiers beyond single traditional algorithms. Building on this review, the specific research questions to delve deeper into the application of these techniques to interpreted Chinese in the present study are as follows:

-

(1)

Do interpreted texts consistently exhibit simplification on the lexical and syntactic levels compared with spoken texts?

-

(2)

Can machine learning techniques classify interpreted Chinese and spoken Chinese through linguistic indices used to test simplification?

-

(3)

What specific linguistic indices contribute significantly to the classification of interpreted and spoken Chinese?

Data and method

In this section, we present the corpus, features (upstream), and classifiers (downstream tasks) used in this work. Similar to Hu and Kübler (2021) and their prior work (Hu et al., 2018) building upon Volansky et al. (2015), we use machine learning for text classification to assess the validity of translation hypotheses through ensemble learning based on the algorithms of Wang et al. (2024b). The pipeline of this experiment is shown in Fig. 1.

Corpora

Our corpus is derived from UN conferences and international forums held between 2014 and 2016, with a primary focus on international relations, human rights, and security issues. The audio files were initially transcribed automatically by iFLYTEK, which has a precision rate exceeding 98%. Subsequently, a manual checking process was implemented to remove any irrelevant elements, such as non-English tokens, pronunciation errors, and instances of code-switching. We segmented the cleaned texts into units of 1000 words without splitting complete paragraphs, resulting in two sub-corpora: (1) the Corpus of Interpreted Chinese and (2) the Corpus of Spoken Chinese. Table 1 presents a summary of the corpus.

Simplified features

We combined a set of Chinese-based features that have been investigated in studies of written translation (Hu and Kübler, 2021) and L2 writing (Hao et al., 2024). Table 2 provides a summary.

Lexical complexity indices

Our eight lexical indices were primarily derived from Hu and Kübler (2021), with the exception of mean tree depth and mean sentence length, which are typically associated with syntactic analysis (Yang, 2019; Choi et al., 2022; Lu and Wu, 2022) and are thus categorized under the syntactic complexity analysis. A brief introduction to the proposed indices follows.

Type-Token Ratio (TTR)

Common in stylometry (Grieve, 2007); includes two variants. A character-based TTR is also introduced to acknowledge the unique challenges of word segmentation in Chinese.

Lexical Density (LD)

The ratio of content words to total tokens, with the expectation that interpreted texts have a lower content word proportion.

Mean Word Length (MWL)

Average word length, with the expectation that interpreted texts are simpler and thus shorter.

Mean Character/Word Rank (MWR/MCR)

Based on frequency lists, with the expectation that interpreted texts make more use of common words and thus return a lower mean rank.

Syntactic complexity indices

Our 14 syntactic indices (see Table 2) were primarily based on four indices from Hu and Kübler (2021) and 10 indices from Hao et al. (2024). In selecting the syntactic indices, we drew from both Hu and Kübler (2021) and Hao et al. (2024). Although Hao et al. (2024) focused on L2 writing, the syntactic indices they used are based on general principles of linguistic complexity that are applicable across different language modalities such as spoken language (Zhao and Lei, 2025). These indices provide a robust measure of syntactic complexity that can be adapted to our study of interpreted Chinese, allowing us to systematically compare the syntactic complexity between interpreted and spoken Chinese.

Mean Constituent Tree Depth (MTD)

The average depth of all constituent trees, representing sentence complexity (Ilisei et al., 2010).

Complex Noun Phrases (NPs) per Clause (NP/CL)

A count of NPs that contain adjectives, quantifiers, classifiers, and other modifiers, with the expectation that original Chinese texts will have more complex NPs (Lu, 2010).

Verb Phrases (VPs) per Clause (VP/CL)

A count of total VPs, excluding those with the copula 是 (shi equals be), to assess the complexity of verb constructions.

Relative Clauses per Clause (RC/CL)

Research has indicated that Chinese written translations exhibit a higher complexity in the use of relative clauses compared with original texts (Lin, 2011; Lin and Hu, 2018); this structural diversity suggests that the usage of relative clauses in interpreted texts and original texts is also likely to differ.

Ten broad syntactic complexity indices informed by Jin (2007), Lu and Wu (2022), and Yu (2021) focusing on length and amount were also measured. Five standard English indices are: (1) mean length of sentence (MLS) calculated by dividing the total number of words in a text by the total number of sentences; (2) mean length of clauses (MLC) calculated by dividing the total number of words in a text by the total number of clauses. Clauses are identified based on syntactic structures such as subject-verb pairs; (3) mean length of t-units (MLTU) calculated by dividing the total number of words in a text by the total number of T-units. A T-unit is a minimal terminable unit of discourse that contains a mandatory subject and predicate; (4) T-units per sentence calculated through dividing the total number of T-units in a text by the total number of sentences; (5) clauses per sentence calculated through dividing the total number of clauses in a text by the total number of sentences. Five Chinese-specific indices related to topic chains, based on their relevance in Mandarin Chinese are: (1) Mean length of topic chains in units (MLTCU) calculated through dividing the total number of words in topic chain units by the total number of topic chain units. A topic chain unit is a sequence of clauses that share a common topic. (2) Mean length of topic chain clauses in units calculated through dividing the total number of words in topic chain clauses by the total number of clauses in topic chain units; (3) clauses per topic chain unit (C/TCU), calculated by dividing the total number of clauses in topic chain units by the total number of topic chain units; (4) number of topic chain units (NTCU) counted by identifying and segmenting the text into distinct topic chain units. (5) number of empty categories in topic chain units (NTCE) counted by identifying and tallying the occurrences of empty categories within each topic chain unit.

Classifiers

We evaluated the effectiveness of a variety of classification algorithms in distinguishing between different types of text. These classifiers form the backbone of our methodology, which is largely inspired by the work of Wang et al. (2024). We selected seven algorithms: logistic regression (LR), naïve Bayes (NB), SVM, k-nearest neighbors (KNN), random forest (RF), gradient boosting classifier (GB), and neural network (NN). To broaden our approach, we incorporated two additional classifiers: the CatBoost Classifier (CB) and Ridge Classifier (RC). The inclusion of CB is strategic because it is a gradient boosting algorithm that excels at handling categorical features, making it highly efficient for our purposes. RC is also valuable because of its foundation in ridge regression, and it is adept at managing multicollinearity and high-dimensional data. Adopting this comprehensive set of classifiers allowed us to explore a diverse range of machine learning strategies to address our research questions.

Experimental setup

Our machine learning experiments were focused on a binary classification task that involved categorizing text segments as either interpreted or spoken Chinese. Nine multiple machine learning classifiers were used separately and as part of an ensemble. Each model was assessed via 10-fold cross-validation to assess its performance on individual features and on all features combined; this aligns with the approach of Hu and Kübler (2021) and Wang et al. (2024). The segmentation, POS tagging, and parsing of Chinese texts were performed in Jieba, which is a popular Chinese word segmentation tool.

Results and discussion

Lexical simplification

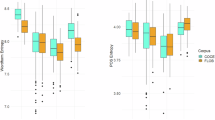

The descriptive results in Table 3 display various indices of the lexical complexity between spoken Chinese (SC) and interpreted Chinese (IC). The simple t-test result indicates significant differences between the two types of Chinese, with all p-values less than 0.05. The visualization in Fig. 2 shows that all of the indices except lexical density are consistent in showing that interpreted Chinese exhibits lower lexical complexity than spoken Chinese.

The TTR, which is a standard measure of lexical diversity, reveals that IC (M TTR1 = 2.60, SD = 0.17; M TTR2 = 5.22, SD = 0.06; M TTR1C = 1.87, SD = 0.11; M TTR2C = 5.00, SD = 0.05) exhibits lower values in both its word-based (TTR1 and TTR2) and character-based (TTR1C and TTR2C) forms than SC (M TTR1 = 2.89, SD = 0.19; M TTR2 = 5.32, SD = 0.06; M TTR1C = 2.02, SD = 0.15; M TTR2C = 5.07, SD = 0.06). This suggests that IC uses a narrower range of vocabulary and characters than IC, which is consistent with the expectation of simplified lexical richness in interpreted language use. This result confirms that of Lv and Liang (2019) that interpreted texts (under the consecutive and simultaneous modes) are less sophisticated than original speech in TTR.

LD, which contrasts content words with function words, shows a higher mean for IC (M = 0.41, SD = 0.04) than for SC (M = 0.35, SD = 0.03). This implies that interpreted Chinese tends to have a higher proportion of content words, potentially indicating denser information than spoken Chinese.

The MWL and MWR/MCR provide further evidence of lexical simplification. IC has a slightly shorter average word length (M = 1.76, SD = 0.06) than SC (M = 1.79, SD = 0.05). IC also shows a considerably lower MWR score (M = 712.13, SD = 106.05) than SC (M = 877.16, SD = 97.20) and a lower MCR (M = 306.02, SD = 40.95) than SC (M = 334.67, SD = 33.07). These findings suggest that interpreted Chinese tends to use more common and higher-frequency words and characters, indicating a simplification in lexical choice.

The descriptive results of the lexical indices suggest that IC demonstrates lower lexical diversity and shorter linguistic units than SC, consistent with the findings of previous researches (Kajzer-Wietrzny, 2012; Bernardini et al., 2016; Lv and Liang, 2019) in supporting the simplification hypothesis by suggesting that interpretations tend to exhibit reduced lexical complexity. Warranting further explanation are the findings of a higher LD in IC, which suggests a richer content word usage and could be a feature characterizing interpreted language (Russo et al., 2006; Dayter, 2018). However, this is counterbalanced by the lower values for IC found in other lexical indices, such as TTR, MWL, MWR, and MCR, which indicate a simplification in lexical choice. The lower TTR values in IC suggest a reduced range of vocabulary and characters, aligning with the need for simplicity and accessibility in interpreted language. The shorter average word length and lower word and character ranks in IC further support the notion of a simplified lexicon, with a preference for more common and high-frequency words and characters. This simplification may be a strategic choice (Yao et al., 2024) to facilitate understanding, reduce cognitive load, and mitigate processing difficulties (Lv and Liang, 2019). The combination of higher lexical density with lower lexical diversity and complexity in IC reflects a tailored approach to language use that prioritizes clarity and efficiency over the richness as well as variety found in spoken language.

Syntactic simplification

The descriptive results for syntactic complexity between SC and IC are presented in Table 4. Simple t-tests indicate statistically significant differences between the two types of Chinese, with all p-values less than 0.05 except that for the mean length of clauses. The visualization in Fig. 3 shows that all of the indices except NTCU and NTCE consistently show that IC exhibits greater syntactic complexity than SC.

MTD, which measures the average depth of all constituent trees to gauge sentence complexity, shows a higher mean for IC (M = 15.05, SD = 2.23) than SC (M = 9.94, SD = 0.82). This suggests that interpreted sentences are structurally more complex, possibly owing to the need to convey more information in a condensed form during interpretation.

The findings for NP/CL and VP/CL further indicate the intricacies of syntactic construction in IC. The count of complex NPs, which contain adjectives, quantifiers, classifiers, and other modifiers, is higher in IC (M = 2.38, SD = 0.81) than in SC (M = 1.08, SD = 0.38), and the count of VPs is also higher in IC (M = 7.06, SD = 1.76) than in SC (M = 4.42, SD = 0.89). These findings suggest that IC adopts more complex noun and verb phrases per clause, adding to the overall syntactic complexity.

The use of relative clauses is significantly higher in IC (M = 2.93, SD = 1.17) than in SC (M = 1.08, SD = 0.40). This aligns with previous research findings that Chinese translation (Lin, 2011; Lin and Hu 2018) have higher complexity in the use of relative clauses. The increased complexity in the use of relative clauses in IC might be attributed to the need for interpreters to convey detailed and precise information, often requiring the use of more complicated sentence structures.

The results for MLS show that IC (M = 67.92, SD = 17.90) has longer sentences and clauses than SC (M = 43.04, SD = 7.79). Similarly, the MLTU is significantly longer in IC (M = 38.55, SD = 10.63) than in SC (M = 23.54, SD = 4.26). These findings suggest sentences in IC are longer and might be more complicated.

The results for the Chinese-specific indices related to topic chains—MLTCU and C/TCU—indicate that IC has longer topic chains and more clauses per unit than SC, with MLTCU (M = 1.38, SD = 0.34) and C/TCU (M = 6.19, SD = 1.55) for IC versus (M = 1.10, SD = 0.08) and (M = 3.42, SD = 0.61), respectively, for SC.

Beyond the above indices where a significant difference was found between IC and SC, the MLC does not reveal a significant difference (p = 0.11), with SC (M = 7.64, SD = 1.02) and IC (M = 7.79, SD = 0.92), but it does suggest a marginal increase in clause length within IC and is thus consistent with the results for the above indices.

However, NTCU reveals a significant contrast, with SC (M = 103.10, SD = 11.95) returning a higher value than IC (M = 84.83, SD = 10.25). NTCE also shows SC (M = 0.47, SD = 0.82) higher than IC (M = 0.32, SD = 0.71), indicating a slightly higher use of empty categories in spoken Chinese. These results imply a more segmented structure in spoken discourse, with speakers perhaps using more distinct topic units to organize their thoughts and make their speech more accessible to the audience. This is consistent with the flexibility and freedom in word order that is characteristic of Chinese, which is a topic-prominent language and allows for indefinite subjects as well as subject/object asymmetry in sentences (Liu et al., 2024). The greater use of empty categories in SC could be related to the frequency in Chinese of topic chain structures involving several clauses sharing a common topic that appears only in the first clause and is then represented by zero pronouns or zero-form nouns in the remaining clauses (Jin, 2007).

IC generally exhibits higher complexity than SC across several syntactic complexity measures. IC demonstrates deeper sentence structures, more complex noun and verb phrases, and longer sentences and T-units. SC does, however, show a greater number of topic chain units, suggesting a more segmented structure in spoken discourse. These results are generally consistent with each other but opposed to the simplification hypothesis that IC tends to exhibit reduced syntactic complexity. These results challenge the syntactic simplification of interpreted language found in English (Sandrelli and Bendazzoli, 2005; Kajzer-Wietrzny, 2015; Bernardini et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2023; Xu and Liu, 2023) but echo those of research findings that translated Chinese is remarkably more complex than the original in mean sentence length (Xiao and Yue, 2009), relative clause usage (Lin, 2011; Lin and Hu, 2018), as well as entropy-based measures (Liu et al., 2022a; Wang et al., 2024a). This difference may be attributed to the unique characteristics of the Chinese language, which allows for more flexible word order and the use of complex syntactic structures such as embedded modifiers (Wang et al., 2017) to convey detailed information. Additionally, the cognitive strategies employed by Chinese interpreters may differ from those used in English interpreting, leading to different patterns of linguistic complexity. Meanwhile, the higher syntactic complexity observed in interpreted Chinese in our study may be attributed to the need to convey complex ideas and detailed information within a limited time frame. Interpreters often face high cognitive load but may strategically use more complex syntactic structures to enhance clarity and precision, even at the cost of increased complexity. This aligns with the findings of Lv and Liang (2019) that suggest a trade-off between lexical and syntactic complexity in interpreted texts. Also, the impact of directionality (Xu and Liu, 2024) cannot be ignored, as producing a translation in one’s native language is expected to be more instinctive and demand less cognitive load, allowing the interpreter to more effectively utilize complex structures (Donovan, 2004).

Classification

Measured by TTRs (TTR1, TTR2, TTR1C, TTR2C) and LD, the classification accuracy performance is consistent across algorithms, with accuracy rates ranging from 50% to 81% (See Table 5). The SVM and NN models exhibit a lower accuracy for TTR2, suggesting challenges for these models in character-based measures of lexical diversity. LD shows high accuracy across most algorithms, indicating a robust ability to classify the proportion of content words in the text. The MWR and MCR indices demonstrate generally high accuracy (>65%) but with a slight dip for the NN, indicating that some models may have difficulties with rank-based complexity measures.

The syntactic indices MTD, NP/CL, VP/CL, and RC/CL show high classification accuracy (>85%), with the highest accuracy rates achieved for MTD (97.88%). This suggests that these indices are strong indicators of syntactic complexity and are well-captured by the algorithms. MLS and MLTU also demonstrate high accuracy (>85%), indicating the algorithms’ effectiveness in distinguishing length-based syntactic complexity. However, MLC and NTCE (<60%) show lower accuracy, which suggests that they may be less reliable indicators for some models.

The LR, NB, and RF algorithms generally perform well across most indices, indicating their robustness in classifying both lexical and syntactic complexity. In contrast, NN shows lower accuracy on certain indices, such as TTR2 and MWL, suggesting a potential overfitting or sensitivity to specific types of complexity measures. The consistency of SVM and CB across indices suggests that these models offer reliable classification across different syntactic features.

The interaction between algorithm choice and index type is also noteworthy. The algorithms show different sensitivities to lexical versus syntactic indices, indicating that the selection of an appropriate algorithm for the focal feature type is crucial for accurate classification. The strong performance of certain algorithms on length-based indices and the challenges they face on character-based measures highlight the importance of algorithm–index interaction in classification tasks.

Table 6 presents the classification accuracy of a voting classifier applied to combined lexical and syntactic indices, showcasing an impressive overall accuracy of 99.2%, which outperforms the classification of any single algorithm. This high figure indicates that the ensemble method effectively capitalizes on the strengths of individual classifiers to improve the predictive performance. The voting classifier’s accuracy on syntactic indices (98.9%) is notably higher than that on lexical indices (89.4%), suggesting that syntactic complexity is more discriminative for distinguishing between SC and IC. The significant jump in accuracy from the lexical to the syntactic indices underscores the importance of syntactic features in classification tasks, providing further evidence that interpreted texts are characterized by syntactic information (Baroni and Bernardini, 2005). The overall accuracy of 99.2% when the lexical and syntactic indices are combined reinforces the notion that an integrated approach yields results that are superior to the accuracy of 97% (Wang et al., 2024b) achieved by using an ensemble model only for syntactic complexity measures. The use of a voting classifier with this ensemble approach demonstrates its ability to improve classification accuracy by combining the predictions of multiple models and thus represents a methodological advancement. This method mitigates the risk of overfitting associated with a single model and captures a more comprehensive representation of the data. The high accuracy indicates that the combined model is highly reliable in distinguishing SC from IC and has profound implications for linguistic analysis, particularly in the fields of TS and computational linguistics. It suggests that a data-driven approach leveraging lexical and syntactic features can provide valuable insights into language use and variation. Furthermore, the robust performance of the voting classifier on syntactic indices highlights the utility of syntactic complexity as a discriminator between different language modalities.

Conclusion

This study investigates the simplification features of Chinese interpreted texts with spoken texts in Chinese at the lexical and syntactic levels. A machine learning approach with an ensemble model was adopted for classification. The accuracy of classifiers reveals the discriminative feature(s) within and beyond each level. The high achieved accuracy indicates a significant difference between interpreted Chinese and spoken Chinese and sheds light on the classification of interpreted versus spoken language and the complexity of interpretation.

Our findings consistently demonstrate that IC exhibits a distinct linguistic profile that is characterized by lower lexical complexity and higher syntactic complexity compared with SC. This pattern contradicts the widely held simplification hypothesis in Indo-European languages, which posits that interpreted texts should display reduced complexity across the board. Instead, our results suggest a dual dynamic in Chinese interpreted texts, which corroborates findings of lexical simplification and syntactic complexification in Chinese translated texts (Liu et al., 2022b).

The machine learning classification experiments validate these observations, with high accuracy rates achieved in distinguishing between SC and IC. The 99.2% overall accuracy of the voting classifier, which leverages an ensemble of algorithms, underscores the potential of integrated lexical and syntactic features for accurately classifying language modalities. These findings not only contribute to methodological advancements in language classification but also offer a robust framework for research in computational linguistics and TIS that requires accurate discrimination between spoken and interpreted languages.

The syntactic complexity indices, particularly MTD, NP/CL, and VP/CL, emerged as strong indicators of syntactic complexity, with classification accuracies exceeding 85%. The findings highlight the importance of syntactic features in differentiating between SC and IC, supporting the notion that syntactic complexity is a more discriminative factor than lexical complexity in this context.

In conclusion, the research offers a data-driven perspective on the linguistic characteristics of interpreted and spoken Chinese, challenging prevailing hypotheses and presenting a new lens through which to view language simplification and complexity. However, the relatively small sample size may limit the generalizability and comprehensiveness of our findings, and also restricted the effective application of large language models for classification and simplification tasks. Future research should address these limitations through collecting larger and more diverse datasets, systematically evaluating the performance of state-of-the-art large language models (like GPT, Baichuan2, and Llama2) on classification and simplification, and exploring the impact of using LLMs for text simplification followed by classification. Further studies could also extend this analytical framework to other languages and modalities, and investigate the underlying cognitive and communicative processes.

Data availability

Our code is available at GitHub (https://github.com/LINGXIFANINTERPRETER/Simplification-in-Interpreting).

References

Baker M (1993) Corpus linguistics and translation studies: Implications and applications. In: Baker M, Francis G, Tognini-Bonelli E (eds) Text and Technology: In Honour of John Sinclair. John Benjamins, Amsterdam, pp 233–250

Baker M (1995) Corpora in translation studies: an overview and some suggestions for future research. Target Int J Transl Stud 7(2):223–243

Baker M (1996) Corpus-based translation studies: the challenges that lie ahead. In: Somers H (ed), Terminology, LSP and Translation. Studies in Language Engineering in Honour of Juan C. Sager, Vol. 18. Benjamins, Amsterdam and Philadelphia, pp.175–186

Baroni M, Bernardini S (2006) A new approach to the study of translationese: machine-learning the difference between original and translated text. Lit Linguist Comput 21(3):259–274

Bernardini S, Baroni M (2005) Spotting translationese: A corpus-driven approach using support vector machines. In Proceedings of Corpus Linguistics Conference Series 2005 (Vol. 1, pp. 1-12). University of Birmingham

Bernardini S, Ferraresi A, Miličević M (2016) From EPIC to EPTIC — exploring simplification in interpreting and translation from an intermodal perspective. Target Int J Transl Stud 28(1):61–86. https://doi.org/10.1075/target.28.1.03ber

Blum-Kulka S, Levenston EA (1987) Lexical-grammatical pragmatic indicators. Stud Second Lang Acquis 9(2):155–170

Chesterman A (2004) Beyond the particular. In: Mauranen A, Kujamäki P (eds), Translation universals: Do they exist?. John Benjamins, Amsterdam and Philadelphia, pp 33–49

Chesterman A (2017) Reflections on translation theory: selected papers 1993–2014, 1st edn, Vol 132. John Benjamins Publishing Company

Choi Y-S, Park Y-H, Lee KJ (2022) Syntactic factors associated with performance of dependency parsers using stack-pointer network and graph attention networks between English and Korean. IEEE Access 10:95638–95646. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2022.3204997

Cvrček V, Chlumská L (2015) Simplification in translated Czech: a new approach to type-token ratio. Russ Linguist 39(3):309–325. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11185-015-9151-8

Dayter D (2018) Describing lexical patterns in simultaneously interpreted discourse in a parallel aligned corpus of Russian-English interpreting (SIREN). Forum Rev Int d’Interprét Trad/Int J Interpretation Transl 16(2):241–264. https://doi.org/10.1075/forum.17004.day

Delaere I, Sutter GD, Plevoets K (2012) Is translated language more standardized than non-translated language?: Using profile-based correspondence analysis for measuring linguistic distances between language varieties. Target: Int J Transl Stud 24(2):203–223. https://doi.org/10.1075/target.24.2.01del

Donovan C (2004) European masters project group: teaching simultaneous interpretation into a B language. Preliminary Find Interpret 6(2):205–216

Fan L, Jiang Y (2019) Can dependency distance and direction be used to differentiate translational language from native language?. Lingua 224:51–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lingua.2019.03.004

Fan L, Cheung AKF, Xu H (2025) Rethinking interpreting training: the impact of interpreting mode on learner performance through entropy-based measures. Int J Appl Linguist https://doi.org/10.1111/ijal.12729

Feng H, Crezee I, Grant L (2018) Form and meaning in collocations: a corpus-driven study on translation universals in Chinese-to-English business translation. Perspect Stud Translatol 26(5):677–690. https://doi.org/10.1080/0907676X.2018.1424222

François T, Lefer M-A (2022) Revisiting simplification in corpus-based translation studies: Insights from readability research. Meta (Montréal) 67(1):50–70. https://doi.org/10.7202/1092190ar

Ferraresi A, Bernardini S, Petrović MM, Lefer M-A (2018) Simplified or not Simplified? The different guises of mediated English at the European Parliament. Meta (Montréal) 63(3):717–738. https://doi.org/10.7202/1060170ar

Grieve J (2007) Quantitative authorship attribution: an evaluation of techniques. Lit Linguist Comput 22(3):251–270. https://doi.org/10.1093/llc/fqm020

Habic V, Semenov A, Pasiliao EL (2020) Multitask deep learning for native language identification. Knowledge-Based Syst 209:106440

Hao Y, Wang X, Bin S, Yang Q, Liu H (2024) How syntactic complexity indices predict Chinese L2 writing quality: an analysis of unified dependency syntactically-annotated corpus. Assess Writ 61: 100847. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asw.2024.100847

Hu H, Li W, Kübler S (2018) Detecting Syntactic Features of Translated Chinese. https://doi.org/10.48550/arxiv.1804.08756

Hu H, Kübler S (2021) Investigating translated Chinese and its variants using machine learning. Nat Lang Eng 27(3):339–372. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1351324920000182

Huang DF, Tay D, Cheung AKF (2025) Text classification to detect interpretese in bidirectional simultaneous interpreting: improved TF-IDF and stacking. IEEE Access 13:70640–70649. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2025.3563148

Ilisei I, Inkpen D, Pastor GC, Mitkov R (2010) Identification of translationese: a machine learning approach. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Intelligent Text Processing and Computational Linguistics, pp 503–511

Jantunen J (2004) Untypical patterns in translations: issues on corpus methodology and synonymity. In: Mauranen A, Kujamäki P (eds), Translation Universals: Do They Exist? Amsterdam and Philadelphia, John Benjamins. pp 33–49

Jin HG (2007) Syntactic maturity in second language writings: a case of Chinese as a foreign language (CFL). J Chin Lang Teach Assoc 42(1):27–54

Kajzer-Wietrzny M (2012) Interpreting universals and interpreting style [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Adam Mickiewicz University, Poznań, Poland

Kajzer-Wietrzny M (2015) Simplification in interpreting and translation. Across Lang Cult 16(2):233–255. https://doi.org/10.1556/084.2015.16.2.5

Kruger H, van Rooy B (2016) Constrained language: a multidimensional analysis of translated English and a non-native indigenised variety of English. Engl World-Wide 37(1):26–57. https://doi.org/10.1075/eww.37.1.02kru

Laviosa S (1998) Core patterns of lexical use in a comparable corpus of English narrative prose. Meta (Montréal) 43(4):557–570. https://doi.org/10.7202/003425ar

Laviosa S (2002) Corpus-based translation studies: theory, findings, applications. Amsterdam, Rodopi

Lin C-JC (2011) Chinese and English relative clauses: processing constraints and typological consequences. In Proceedings of the 23rd North American Conference on Chinese Linguistics (NACCL-23). Eugene, OR

Lin C-JC, Hu H (2018) Syntactic complexity as a measure of linguistic authenticity in modern Chinese. In Proceedings of the 26th Annual Conference of International Association of Chinese Linguistics and the 20th International Conference on Chinese Language and Culture. Madison, WI

Liu K, Afzaal M, Amancio DR (2021) Syntactic complexity in translated and non-translated texts: a corpus-based study of simplification. PloS One 16(6):e0253454–e0253454. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0253454

Liu K, Ye R, Zhongzhu L, Ye R, Mumtaz W (2022a) Entropy-based discrimination between translated Chinese and original Chinese using data mining techniques. PloS One 17(3):e0265633–e0265633. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0265633

Liu K, Liu Z, Lei L (2022b) Simplification in translated Chinese: an entropy-based approach. Lingua 275: 103364. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lingua.2022.103364

Liu Y, Cheung AKF, Liu K (2023) Syntactic complexity of interpreted, L2 and L1 speech: a constrained language perspective. Lingua 286: 103509. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lingua.2023.103509

Liu X, Li F, Xiao W (2024) Measuring linguistic complexity in Chinese: an information-theoretic approach. Hum Soc Sci Commun 11(1):980–12. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03510-7

Lu X (2010) Automatic analysis of syntactic complexity in second language writing. Int J Corpus Linguist 15(4):474–496. https://doi.org/10.1075/ijcl.15.4.02lu

Lu X, Wu J (2022) Noun-phrase complexity measures in Chinese and their relationship to L2 Chinese writing quality: a comparison with topic–commentunit-based measures. Mod Lang J 106(1):267–283. https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12766

Lv Q, Liang J (2019) Is consecutive interpreting easier than simultaneous interpreting? - a corpus-based study of lexical simplification in interpretation. Perspect Stud Translatol 27(1):91–106. https://doi.org/10.1080/0907676X.2018.1498531

Mauranen A (2006) Translation universals. In: Brown K (ed), Encyclopedia of language and linguistics, 2nd edn. Elsevier, pp 93–100

Russo M, Bendazzoli C, Sandrelli A (2006) Looking for lexical patterns in a trilingual corpus of source and interpreted speeches: Extended analysis of EPIC (European Parliament Interpreting Corpus). Forum 4(1):221–254

Rubino R, Lapshinova-Koltunski E, Van Genabith J (2016) Information density and quality estimation features as translationese indicators for human translation classification. In Proceedings of the 2016 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies. San Diego, CA, USA, pp 960–970

Sandrelli A, Bendazzoli C (2005) Lexical patterns in simultaneous interpreting: A preliminary investigation of EPIC (European Parliament Interpreting Corpus). In Proceedings from the Corpus Linguistics Conference Series 1. University of Birmingham, Birmingham

Vanderauwera R (1985) Dutch novels translated into English: the transformation of a ‘minority’ literature. Amsterdam, Rodopi

Volansky V, Ordan N, Wintner S (2015) On the features of translationese. Digit Scholarsh Hum 30(1):98–118. https://doi.org/10.1093/llc/fqt031

Wang B, Zou B, Defrancq B, Russo M, Bendazzoli C (2017) Exploring language specificity as a variable in Chinese-English interpreting. a corpus-based investigation. In Making Way in Corpus-Based Interpreting Studies. Springer Singapore Pte. Limited, pp 65–82. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-6199-8_4

Wang Z, Liu K (2024) Linguistic variations between translated and non-translated English Chairman’s statements in corporate annual reports: a multidimensional analysis. SAGE Open, 14(2). https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440241249349

Wang Z, Cheung AKF, Liu K (2024a) Entropy-based syntactic tree analysis for text classification: a novel approach to distinguishing between original and translated Chinese texts. Digit Scholarsh Hum 39(3):984–1000. https://doi.org/10.1093/llc/fqae030

Wang Z, Liu M, Liu K (2024b) Utilizing machine learning techniques for classifying translated and non-translated corporate annual reports. Appl Artif Intell 38(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/08839514.2024.2340393

Xiao R, Yue M (2009) Using corpora in translation studies: the state-of-the-art. In: Baker P (ed), Contemporary corpus linguistics. Continuum, London, pp 237–262

Xiao R (2010) How different is translated Chinese from native Chinese?: A corpus-based study of translation universals. Int J Corpus Linguist 15(1):5–35. https://doi.org/10.1075/ijcl.15.1.01xia

Xiao R, Hu X (2015) Corpus-Based Studies of Translational Chinese in English-Chinese Translation, 2015th edn. Springer Berlin, Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-41363-6

Xu C, Li D (2022) Exploring genre variation and simplification in interpreted language from comparable and intermodal perspectives. Babel 68(5):742–770

Xu C, Li D (2024) More spoken or more translated? Exploring the known unknowns of simultaneous interpreting from a multidimensional analysis perspective. Target 36(3):445–480

Xu H, Liu K (2023) Syntactic simplification in interpreted English: Dependency distance and direction measures. Lingua 294: 103607. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lingua.2023.103607

Xu H, Liu K (2024) The impact of directionality on interpreters’ syntactic processing: Insights from syntactic dependency relation measures. Lingua 308:103778

Xu X, Chang Y, An J, Du Y (2023) Chinese text classification by combining Chinese-BERTology-wwm and GCN. PeerJ Comput Sci 9: e1544. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj-cs.1544

Yang J (2019) Syntactic hierarchy depth: distribution, interrelation and cross-linguistic properties. J Quant Linguist 26(2):129–145. https://doi.org/10.1080/09296174.2018.1453962

Yao Y, Li D, Huang Y, Sang Z (2024) Linguistic variation in mediated diplomatic communication: a full multi-dimensional analysis of interpreted language in Chinese Regular Press Conferences. Hum Soc Sci Commun 11(1):1409–1412. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03967-6

Yu Q (2021) An organic syntactic complexity measure for the Chinese language: the TC-unit. Appl Linguist 42(1):60–92. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amz064

Zhao N, Lei L (2025) Chipola: a Chinese Podcast Lexical Database for capturing spoken language nuances and predicting behavioral data. Behav Res Methods 57(6):1–19

Acknowledgements

This article is funded by The Hong Kong Polytechnic University (Number: P0050978).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LXF: data cleaning and processing; statistical analysis; writing—original draft; writing—review & editing. AKFC: conceptualization; data collection; funding; supervision; writing—review & editing. YY: conceptualization; methodology; writing—review & editing. RX: conceptualization; methodology. CS: conceptualization; methodology.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was not required as the study did not involve human and animal participants.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fan, L., Yao, Y., Xie, R. et al. Simplification in interpreting: the text classification of spoken and interpreted Chinese through ensemble learning techniques. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 13, 83 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-06382-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-06382-7