Abstract

Work with interviews has become widespread in recent decades, and modern technologies provide the choice between using only the transcript for further evaluation or additionally taking advantage of the audio track. Given that voice can carry extra information not contained in the text, this might lead to differences in judging the content of the text elements. We experimentally compared the evaluation of statements made by contemporary witnesses from the postwar period about the development of psychology in Germany. Fifty-four subjects rated whether the 26 quotations expressed either continuity in psychology after the war or rather a new beginning on a Likert scale. We experimentally varied whether or not the witnesses’ voices were added to the transcripts. On average, quotes with vs. without voice led to similar judgments. However, individual ratings in the condition with voice added tended to be more extreme. These results are relevant for future projects combining written and audio material.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Research on the history of psychology has often relied on interviews with witnesses (e.g., Dutt & Grabe, 2014; Nyman, 2010). For instance, an oral history approach has been used in work on the history of feminist psychology (cf. Johnston & Johnson, 2008; Ruck, 2015) and developmental psychology (cf. Cameron & Hagen, 2005; Johnson & Johnston, 2015). Given past and developing research practice, it seems important to scrutinize an often neglected aspect of this material: the potential impact of voice properties. While interviews are often transcribed before being analyzed, the aspects of the spoken word might still have an impact on the analysis of the material, as, for instance, Gibson (2017) indicated regarding the Milgram Experiment. Often, the person providing the transcript also participates in the analyses of the written text (e.g., Nyman, 2010; Corcoran et al., 2019). The voice of a speaker can carry cues regarding their metacognitive status (being sure/unsure), (lack) of sympathy for a subject or person that is the object of the elaboration, and many other aspects that might not be apparent in the transcription (e.g., Nicolai et al., 2010). Analyzing text with vs. without hearing the voice might influence judgments and categorizations of the researcher. The invention and widespread use of emoticons in digital text messages suggests that additional information about emotions helps to address the semantic part of the message and prevent misunderstandings. Meanwhile, speech emotion recognition systems exist that process and classify speech signals to recognize implicit emotions (e.g., Akcay & Oguz, 2020).

In order to explore the extent to which experiencing the voice of a speaker alters the categorization of content relevant to the history of psychology, a subject should be used where witnesses and persons analyzing their statements are both likely to feel strongly involved. We chose to confront participants with interview material from witnesses being interviewed on the reconstruction of psychology in Germany after World War II. The audio material on which this study is based had been collected between 2000 and 2003 as part of the project Psychology in Reconstruction by Prof. Dr. Helmut E. Lück and Dr. Hermann Feuerhelm, funded by the German Research Foundation. Interviews aimed to explore the extent to which networks and content from Nazi-era psychology in Germany were re-established after World War II (continuity) and the extent to which a new orientation and cohort of academics could be established (new beginning).

In our prior work (author, 2020), the transcribed form of interview statements was presented to test persons who evaluated them with regard to whether they expressed continuity vs. a new beginning. In the 2020 study, however, only the transcribed quotes from contemporary witnesses were used. In the current study, we experimentally varied whether statements were provided as text plus audio vs. as text only. It is conceivable that linguistic features, emotions or emphasis could lead to a different evaluation of the interview statements. Work on the potential surplus of spoken over written language dates back at least to the Organon model by Bühler (1934), underlining that physical sound is not identical to the linguistic sign. Someone can say more than is relevant to the specific situation (i.e., the receiver abstracts the essential meaning from the perceived sound waves). In contrast, the opposite is possible as well, as the receiver might independently add additional information that has not been explicitly communicated (Bühler, 1934). The added benefit of spoken language has also been discussed while using automated speech as a test case (Shankweiler & Fowler, 2015). Research has long been underway on the properties of language that are not contained in text form. Besides the semantic content, additional information such as the workload and the psychological and physiological stress of a person can be inferred from spoken language on the basis of acoustic variations (e.g., Ruiz et al., 1990).

Aspects of spoken language proved to be meaningful indicators of the human emotional state, such as spectral and spectral-temporal characteristics of fast and slow speech components, as well as temporal qualities and intensity of speech. Based on these properties, it is possible to recognize emotions and their manifestations and even to distinguish between emotional and physical stress (Simonov & Frolov, 1977). It seems that a person’s predominant emotions can be heard in their voice, but sexual orientation, for example, cannot (Sulpizio et al., 2020). Suires, Tognettis and Durands (2020) studied qualities that distinguish female from male voices: the fundamental frequency, modulation, overtone to noise ratio (a proxy for vocal breathing) and jitter (a proxy for vocal roughness).

Seminal work has targeted possible differences in content extraction from written vs. spoken text. Kintsch and Kozminsky (1977) suggested that the comprehension processes of reading and listening possess a common core. The test participants listened to or read three stories recorded on tape. Then a summary was written. The comparison of the results showed only slight differences between the listening and reading conditions. The only difference was that after listening to the story, more idiosyncratic details were reproduced while the actual content of the summaries was remarkably similar. Following up on this, it has been investigated whether there are also differences in the depth of processing depending on the presentation of auditory vs. written material and whether this also leads to differences in mental representations (Kim & Petscher, 2016; Kim et al., 2019; Kürschner et al., 2006). The monistic position states that the processing and representation in reading and listening are the same. It is therefore assumed that the same mental lexicon is used and that the same syntactic processing processes are present, leading to comparable mental representation (Gilbert et al., 2018; Kürschner et al., 2006). This is justified by the fact that hearing is a valid predictor for learning to read (Kürschner & Schnotz, 2008). In contrast, the dualistic position claims that there are differences between hearing and reading at the lower and higher levels of cognitive processing (Kürschner et al., 2006). Specific memory processes during hearing and reading are assumed (Kürschner & Schnotz, 2008).

Overall, it can be said that voice and spoken language contain some information that is absent in writing. Some of which can potentially influence judgments about the text content.

Purpose of the present study

The literature suggests that multimodal presentation (text + audio) can differ from text-only presentation in many aspects. Yet, there is a lack of testing whether (and how) this leads to different research outcomes when working with eye-witness material on questions relevant to the history of psychology. In the current work, we explored the potential impact of experiencing the voice in addition to text. First, we checked whether ratings on different statements from eye-witnesses would lead to mean level differences in ratings concerning the extent to which the statements signaled continuity vs. a new beginning. After securing that statements could be consistently categorized, we explored whether mean ratings as well as variability in ratings would be affected by whether voice was made available in addition to text.

Method

Research design

The experiment was programmed using lab.js (Henninger et al. 2020), a free experiment creation tool for online experiments. The study design was a within-subjects design with four different balancing conditions (see Table 1). This ensured that each participant rated each interview excerpt only once, avoiding repeated exposure to the same material and potential carryover effects. Yet, each participant rated half of the material based on the text form and half based on the text-plus-spoken form. Across participants, each interview excerpt was evaluated in either of the two variants equally often.

The participants were randomly assigned to one of the four different test variants. 26 statements were used and can be found in the digital appendix on the platform OSF.io in the original language and in English translation. All participants were presented with 13 statements as audio recordings with the transcription and 13 statements in text form for evaluation. Within the sections of the conditions, the citations were presented in random order.

The independent variable was multi-modality, i.e., whether only the transcription or the sound recording with transcription was presented, or the audio was additionally available. The rating on the eyewitness’s statement was the dependent variable. The test subjects answered the question of whether a presented quote expressed continuity in psychology or a new beginning and rated their evaluation on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (continuity) to 5 (new beginning).

Sample

For the procedure of the current study, a positive vote was obtained from the institutional review board of the Faculty of Psychology, and participants provided informed consent. A total of 54 volunteers took part in the study. The participants were tested individually as part of BSc.-thesis projects (see Acknowledgment). Due to incomplete data, two participants were excluded from the analysis. The final sample consisted of 52 participants, of whom 26 were female. Post-hoc power analyses with G*Power (Faul et al. 2009) showed that with this approach, we could reach a power of 0.89 to detect a difference of d = 0.4 in a two-tailed comparison (within-subjects t test) with alpha = 0.05. The age range of the subjects was 21 years to 75 years (M = 42.52, SD = 14.76). There were 12 people in the balancing condition A. In variant B, there were 11 persons, 18 persons in condition C and 11 in condition D (see Table 1).

The test materials

The study was based on interviews with contemporary witnesses from the (anonymized). The interviews used originate from two research projects of the author and (anonymized) funded by the German Research Foundation, carried out in 2000 and 2003 (Bettenhausen, 2020). The eyewitnesses had participated after obtaining informed consent and being informed of the procedure, data storage and usage. Since the interviews were available as sound recordings, the selected excerpts were transcribed. Annotations were not used in the transcription to make reading easier for the participants.

Relevant passages from the interviews were selected, which cover the post-war period from 1945 to 1950 and contain a reference to continuity or new beginnings in German psychology. The quotes were selected based on referring to continuity or new beginnings in terms of content (rather than simply containing general statements) and based on referring to the time span from 1945 to 1950. In a previous study (author, 2020), it was possible to identify contemporary witnesses whose statements expressed more of a continuity or a new beginning in psychology. Quotes from these witnesses were selected with priority for this study. The quotes used in the current study are documented online: https://osf.io/emybp/.

Since the selected interview passages address specific historical or psychological aspects that could make them difficult to understand, short explanatory texts were composed and amended to the original statements. These set the quote into context by explaining terms such as “psychotechnology” or “denazification” and gave details of individual personalities. Care was taken not to include too many explanations, as this could have overwhelmed the participants or led to floor or ceiling effects in the categorizations. Importantly, the explanations were added identically in both of the experimental conditions (written text vs. written text plus voice). Examples for excerpts are “(…) in the first days after the collapse, people came and were clearly often Americans and were clearly instructed to look through the libraries for Nazi literature and eliminate this literature.” or “That was really a time of awakening, because you were really, if you like, with this inadequate training, this one-sided training, with this short training, you actually had a tremendous need to catch up, because the wave was gradually sweeping over from abroad.” The audio files of the quotes were 4 to 35 seconds long.

The test procedure

After welcoming the participants, explanations were given regarding data protection guidelines and anonymization. Then, the participants read the instructions of the study explaining the purpose of the investigation, the procedure and giving an example of the evaluation, as well as the approximate duration of about 30 minutes. The experimenter ensured that the sound level was set adequately so that the audio material could be heard and took care that all participants understood the instructions. As described above, we counterbalanced the experimental conditions and their order for the different statements. Within a condition, the statements were presented in an individually randomized order.

At the beginning of each trial, a new written statement was presented on the screen. Written context information was presented together with the statement. In the text-plus-voice condition, the audio was played while the written statement was on the screen. If necessary, it was possible for the subject to listen to the statement again. There was no time limit for submitting the rating. Rather, the subject could independently move to the next statement by turning in the rating.

Independent ratings of emotionality and arousal

Based on feedback to an earlier version of this manuscript we had four independent raters judge on a rating scale (1 = not at all; 7 = very strong) (a) the level of emotionality of the voice of the interviewed person and (b) the level of arousal of the interviewed person for each of the audio files in order to explore one possible basis of differences between the voice-plus-text and the text-only variant.

Results

Figure 1 shows the profile of the average ratings for the text vs. the text-plus-voice condition across the statements. For Set 1 (Statements 1 to 13), there was a Pearson correlation of r = 0.991 between the mean values of the experimental conditions (text + voice vs. text-only). For Set 2, the profile correlation was very high as well (r = 0.976). These values imply that the profiles were highly similar for the two experimental conditions. In both conditions, participants were capable of differentiating among the statements and did so in a consistent manner.

Furthermore, Fig. 1 (and also Fig. 2a) suggests that there was hardly any mean difference between the text (M = 3.04, SD = 0.47) and the text-plus-voice condition (M = 3.01, SD = 0.51; t(51) = 0.92, p = 0.362, dav = 0.061, for the paired t test). Thus, adding the voice to the text did not systematically bias the ratings overall.

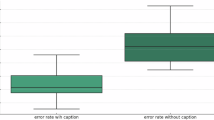

Ratings averaged across participants might hide differences in variability. Conceivably, adding voice to the text might lead to more extreme ratings (in either direction). Indeed, the average within-subjects standard deviation (i.e., across quotes) in the text-plus-voice condition (M = 1.33, SD = 0.48) was higher than in the text condition (M = 1.22, SD = 0.48; t(51) = 2.77, p = 0.008, dav = 0.229, for the paired-measures t test; Fig. 2b). Thus, participants in the text-plus-voice condition differentiated more strongly among the sentences. Further explorations suggest that this higher variability was specifically driven by a higher proportion of extreme ratings. There were M = 44.53% (SD = 25.14%) ratings either with the lowest (1) or highest (5) category of the scale in the text-plus-voice condition, while this proportion was lower in the text condition by 8.88% (M = 35.65%, SD = 26.6%; t(51) = 2.73, p = 0.009, paired t test, dav = 0.343; Fig. 2c).

To explore potential bases for the differences between the text vs. the text-plus-voice ratings, we analyzed the judgments of the four independent raters concerning emotionality and arousal in the voices of the interviewed persons. Both aspects were on average rated as rather low (M = 3.12 and M = 2.95, respectively; mid-point of the scale = 4). The agreement amongst the four raters was substantial (Cronbach's Alpha across the items = 0.69 and 0.73, respectively), so we averaged across the four raters. Yet, checking the correlation between, on the other hand, the emotionality rating and, on the other hand, the judgments concerning new beginning vs. continuity for text and voice, text or the difference of the media conditions did not reveal a significant correlation. The same was true when using the arousal rating instead (ps > 0.05).

Discussion

Working with witness statements in research on the history of psychology might involve emotional topics for which the presence vs. absence of voice might tip the balance between different interpretations of historical developments. Using statements from interviewed witnesses on the issue of continuity vs. new beginning in rebuilding psychology in Germany after World War II as a test case, we tested whether including voice to transcribed statements might affect content judgments. Underlining the validity of our procedure, we found that participants – despite not being markedly knowledgeable of the history of psychology – were consistent in rating different citations (see Fig. 1). While the overall average judgment across raters processing the statements was not affected by whether voice was combined with the transcribed text, subjects’ ratings were more polarized in the conditions in which the voice recording was played with the text presentation. Potentially, people strive for coherence and produce more extreme judgments by selectively attending to the aspects and interpretations of the statement that fit the emotions transmitted and judgments inferred from the audio (cf., Engel et al., 2020).

These results are relevant for methodological aspects of research. While in the current study, polarized ratings averaged out given the high number of raters, the current results suggest that adding voice to transcripts can lead to a more extreme average rating when using a small number of raters. The finding that average ratings are similar while voice seems to make single ratings more extreme suggests a nuanced interpretation concerning the debate (Gilbert et al., 2018; Kürschner et al., 2006), whether reading and listening are similar (monistic position) or cognitive processes differ across modalities (dualistic position). On the one hand, it is plausible that processes are qualitatively the same, yet adding voice implies adding arousal and/or noise. On the other hand, adding voice might lead to text processing that differs qualitatively.

While the current study suggests that adding voice to transcripts can lead to polarized evaluation of the content, further work is needed to understand which aspects of voice are relevant for such an effect. Aspects such as irony might be very hard to deduce from text alone, while they are effectively communicated by paraverbal auditory cues (Aguert, 2022). Furthermore, it is currently not clear whether the effects of paraverbal auditory cues would be larger if raters were confronted with even shorter quotes (cf. Wang et al. 2021). On the one hand, presenting raters with an audio statement of, for instance, only two seconds might increase reliance on paraverbal cues, as time would not allow for substantial amounts of text to be conveyed. Yet, on the other hand, in long interview snippets, participants might derive an overall impression and attentional filters from paraverbal auditory cues. Hence, paraverbal auditory cues might be influential in very short as well as in rather long sections of material.

While rated emotionality and rated arousal of the voice did not seem to account for the effect, further studies might systematically test for larger arrays of voice properties. Additionally, it might be fruitful to test the impact of added voice on content ratings in domains with a clear ground truth. While ratings on continuity vs. new beginning in post-war German psychology were consistent across raters, the benchmark for what should be considered as a correct answer might differ across domains relevant to this issue. A further issue for future studies concerns the different directions of influence between written text and picture, when working with interviews. The current results and evidence for that spoken text can contain more information than written text (e.g., Nicolai et al., 2010), suggesting that adding voice can alter the interpretation of written text. Yet, visually presented text might also influence the reception of spoken text. In three studies, Moreno and Mayer (2002) investigated whether and under which conditions the addition of written text can improve the understanding of a spoken scientific multimedia explanation. The subjects received an explanation of the process of flash formation in two modalities: auditory only (non-redundant) or auditory and visual (redundant). The subjects understood the explanation best when the words were presented not only auditorily but also visually, provided that there was no other simultaneous visual material. The overall pattern of the results can be explained by a dual-processing model of working memory. Further studies might investigate how presenting the written text can support tasks for which spoken text has to be analyzed in working with interview material.

Data availability

Material and data are made available online: https://osf.io/emybp/.

References

Akcay MB, Oguz K (2020) Speech emotion recognition: emotional models, databases, features, preprocessing methods, supporting modalities, and classifiers. Speech Commun 116:56–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.specom.2019.12.001

Aguert M (2022) Paraverbal expression of verbal irony: vocal cues matter and facial cues even more. J Nonverbal Behav 46:45–70. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10919-021-00385-z

Bettenhausen M (2020) Psychologie im Nachkriegsdeutschland: Kontinuität oder Neuanfang? Eine psychologiegeschichtliche Untersuchung anhand von Zeitzeuginnen‑ und Zeitzeugeninterviews. In: Wieser M (ed) Psychologie im Nationalsozialismus. In: Lück HE, Stock A (eds) Beiträge zur Geschichte der Psychologie, 32. Peter Lang, Berlin, pp 223–247

Bühler K (1934) Sprachtheorie: Die Darstellungsfunktion der Sprache. Fischer, Jena

Cameron CE, Hagen JW (2005) Women in child development: themes from the SRCD Oral History Project. Hist Psychol 8(3):289–316. https://doi.org/10.1037/1093-4510.8.3.289

Corcoran K, Häfner M, Kauff M et al. (2019) A reflection on crucial periods in 50 years of social psychology (in Germany). Soc Psychol 50(1):1–6. https://doi.org/10.1027/1864-9335/a000372

Dutt A, Grabe S (2014) Lifetime activism, marginality, and psychology: narratives of lifelong feminist activists committed to social change. Qual Psychol 1(2):107–122. https://doi.org/10.1037/qup0000010

Engel C, Timme S, Glöckner A (2020) Coherence-based reasoning and order effects in legal judgments. Psychol Public Policy Law 26(3):333–352. https://doi.org/10.1037/law0000257

Faul F, Erdfelder E, Buchner A et al. (2009) Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav Res Methods 41:1149–1160. https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.41.4.1149

Gibson S (2017) Developing psychology’s archival sensibilities: revisiting Milgram’s ‘obedience’ experiments. Qual Psychol 4(1):73–89. https://doi.org/10.1037/qup0000040

Gilbert RA, Davis MH, Gaskell MG et al. (2018) Listeners and readers generalize their experience with word meanings across modalities. J Exp Psychol Learn Mem Cogn 44(10):1533–1561. https://doi.org/10.1037/xlm0000532

Henninger F, Shevchenko Y, Mertens U et al. (2020) lab.js: a free, open, online experiment builder. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3767907

Johnson A, Johnston E (2015) Up the years with the Bettersons: gender and parent education in interwar America. Hist Psychol 18(3):252–269. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0039521

Johnston E, Johnson A (2008) Searching for the second generation of American women psychologists. Hist Psychol 11(1):40–72. https://doi.org/10.1037/1093-4510.11.1.40

Kim Y‑S G, Petscher Y, Uccelli P et al. (2019) Academic language and listening comprehension—Two sides of the same coin? An empirical examination of their dimensionality, relations to reading comprehension, and assessment modality. J Educ Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000430

Kim Y‑SG, Petscher Y (2016) Prosodic sensitivity and reading: an investigation of pathways of relations using a latent variable approach. J Educ Psychol 108(5):630–645. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000078

Kintsch W, Kozminsky E (1977) Summarizing stories after reading and listening. J Educ Psychol 69:491–499

Kürschner C, Schnotz W (2008) Das Verhältnis gesprochener und geschriebener Sprache bei der Konstruktion mentaler Repräsentationen. Psychol Rundsch 59(3):139–149

Kürschner C, Seufert T, Hauck G et al. (2006) Konstruktion visuell‑räumlicher Repräsentationen beim Hör‑ und Leseverstehen. Z Psychol 214(3):117–132

Nicolai J, Demmel R, Farsch K (2010) Effects of mode of presentation on ratings of empathic communication in medical interviews. Patient Educ Couns 80(1):76–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2009.10.014

Moreno R, Mayer RE (2002) Verbal redundancy in multimedia learning: When reading helps listening. Journal of Educational Psychology 94(1):156–163. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.94.1.156

Nyman L (2010) Documenting history: an interview with Kenneth Bancroft Clark. Hist Psychol 13(1):74–88. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018550

Ruck N (2015) Liberating minds: consciousness-raising as a bridge between feminism and psychology in 1970s Canada. Hist Psychol 18(3):297–311. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0039522

Ruiz R, Legros C, Guell A (1990) Voice analysis to predict the psychological or physical state of a speaker. Aviat Space Environ Med 61(3):266–271

Shankweiler D, Fowler CA (2015) Seeking a reading machine for the blind and discovering the speech code. Hist Psychol 18(1):78–99. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038299

Simonov PV, Frolov MV (1977) Analysis of the human voice as a method of controlling emotional state: achievements and goals. Aviat Space Environ Med 48(1):23–25

Sulpizio S, Fasoli F, Antonio R et al. (2020) Auditory Gaydar: perception of sexual orientation based on female voice. Lang Speech 63(1):184–206. https://doi.org/10.1177/0023830919828201

Suire A, Tognetti A, Durand V et al. (2020) Speech acoustic features: a comparison of gay men, heterosexual men, and heterosexual women. Arch Sex Behav 49:2575–2583. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-020-01665-3

Wang MZ, Chen K, Hall JA (2021) Predictive validity of thin slices of verbal and nonverbal behaviors: comparison of slice lengths and rating methodologies. J Nonverbal Behav 45:53–66. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10919-020-00343-1

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Hermann Feuerhelm for the extensive data collection of the eyewitness interviews. Furthermore, we would like to thank (1) Michael Poller for help with setting up the computerized testing, (2) Lena Heimannsberg, Gülsah Keskin, Bianca Klering, and Anne Steiner for help with data acquisition, (3) Rebecca Junginger, Isabelle Malinowski, Panagiota Papadopoulou, and Stefanie Sievers-Reiker for rating emotionality and arousal of audios, and (4) Monica Mary Heil for language checking of the manuscript.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MB, RG and HL planned the study. HL provided interview material and background information and gave feedback on the research plan and the results. MB conducted the study and analyzed the data. RG helped with data analysis and edited the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards and in line with the local regulations. The national and local regulations for this type of study do not require soliciting an institutional review board. At the local level (Faculty of Psychology), the “Regulations of the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Psychology at the FernUniversität in Hagen” (https://www.fernuni-hagen.de/psychologie/docs/ordnung_der_lokalen_ethikkommission_18_10.pdf) state that researchers are responsible to sensitively plan and conduct research with human participants. If researchers choose to solicit advice from the local institutional review board, this should be done before conducting the study. Yet, there is no obligation to obtain such advice from the review board prior to running a study. Researchers can run a study with or without submitting beforehand to the local ethics review board. In either case, they are responsible for sensitively planning and conducting research with human participants. Also, at the university level, the “Regulations on the Ethical Conduct of Research involving Human Subjects” (https://www.fernuni-hagen.de/forschung/docs/ordnung_ethik.pdf) specify that researchers are to sensitively plan and conduct research with human participants and how colleagues and participants could deal with potential misconduct. Again, there is no obligation to submit the study before running it. Given that the study presented here had been conducted within research-oriented teaching and had to strictly follow the teaching-related deadlines that were incompatible with the reviewing times of the institutional review board, obtaining feedback from the institutional review board before running the study within the semester would not have been possible (and was not required—see above). Yet, to take advantage of the advice to further improve the procedure and with the perspective of running follow-up studies, the study protocol was submitted after data collection had taken place (for a potential future study that would follow up on the current one). As a result, for the procedure of the current study, a positive voting was obtained from the institutional review board of the Faculty of Psychology (IRB Name: Ethikkommission der Fakultät für Psychologie der FernUniversität in Hagen, Approval Number: EA_811_2024, March 25th, 2024, scope of approval: treatment of research participants and data and usage for the research aims in form of publication). All research was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed consent

All participants (adults) provided written informed consent before participating in the study. Participants were provided with written information prior to the start of the study, outlining the voluntary nature of participation, data protection, and the study’s objectives. All participants have been fully informed that their anonymity is assured, why the research is being conducted, how their data will be utilized, and that there are no specific risks to them of participating. Participants provided informed consent individually, directly before participating in the study. Data collection took place between March 18, 2019, and April 15, 2019. Informed consent was obtained at the beginning of the survey. The scope of the consent involved participation, data use, and publication of the results. The study did not recruit individuals who are vulnerable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bettenhausen, M., Gaschler, R. & Lück, H.E. Adding voice to transcripts leads to more extreme judgments of eye-witness statements on rebuilding psychology in Germany after World War II. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 13, 86 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-06387-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-06387-2