Abstract

Polarisation is a widespread societal issue, dividing populations into opposing groups whose beliefs may span multiple, seemingly unrelated, topics. This phenomenon creates distinct cultural groups with internally consistent yet mutually opposing beliefs, strengthening group identities and deepening societal divides. We develop a mathematical model to investigate how polarisation and emergent associations between unrelated beliefs occur. Unlike prior models assuming irrationality, informational segregation, or similarity biases, our model employs an epistemic distinction between two filtering mechanisms: content and source filtering. In content filtering, agents evaluate beliefs based on intrinsic coherence, rejecting information opposing their current beliefs. Source filtering, in contrast, involves adopting beliefs based on the perceived credibility of information sources, where credibility corresponds to mutual consistency between individuals’ belief systems. We further incorporate external signals through varying innovation and loss rates to reflect empirical biases from real-world data. Simulations show that source filtering rapidly clusters beliefs into two dominant, highly polarised groups. Within each group, beliefs become tightly correlated, creating strong opposition between the groups across all cultural traits. Thus, new associations emerge spontaneously between previously unrelated beliefs. Arbitrary and initially independent beliefs transform into ideological bundles serving as clear group signals. External signals further reinforce these associations, allowing advantages of particular beliefs (e.g. empirical evidence) to transfer to associated beliefs. Content filtering can also produce polarised groups, but beliefs remain aligned with preexisting logical or factual structures. Source filtering mirrors algorithmic biases such as collaborative filtering prevalent on digital platforms, where content exposure depends heavily on shared user preferences rather than intrinsic coherence. Our findings illustrate how these biases amplify polarisation by reinforcing homogeneous belief packages, intensifying ideological divides within cultural systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Societies around the world often exhibit deep ideological divides that run across numerous, seemingly unrelated issues, from climate change to economic policy to public health interventions. Such beliefs frequently cluster into factions with opposing views across multiple topics, reinforcing group identities. Multi-dimensional polarisation is especially evident in digital societies, where social media platforms, powered by machine learning, can amplify these divisions through information biases.

We will here explore how such multi-dimensional polarisation emerges and is maintained, by drawing on cultural evolution theory, and applying a systems approach (Buskell et al., 2019), where cultural traits and beliefs are related and interdependent. We have developed mathematical models to investigate how mechanisms for transmitting and filtering beliefs in social interactions give rise to belief systems. Our main question is why positions on unrelated topics—such as beliefs about anthropogenic climate change, the safety of genetically modified foods, the risks posed by advanced artificial intelligence, or views about energy sources or gun control—become correlated, and how social interactions can create group boundaries even when opinions start out as intrinsically unconnected.

Our primary focus here is on how people filter information (e.g. Jansson et al., 2021), exercising epistemic vigilance (Sperber et al., 2010), which is comparable to direct and model-based transmission biases (e.g. Boyd and Richerson, 1985), though with an emphasis on beliefs. To build an evidentially sound and logically consistent worldview, it would be rational for individuals to employ content filtering: to assess new information on the basis of its content and coherence with existing beliefs. However, there are many reasons why such a strategy is not tractable, for example that it is cognitively demanding and requires access to sufficient or first-hand information, which may be unavailable. A common proxy is source filtering, assessing information by source credibility rather than content. Source credibility will here be operationalised as having beliefs consistent with those of the receiver. We will investigate the role of source filtering in the ways in which beliefs can form bundles, creating polarised camps that transcend single-issue disagreements, generating cultural differentiation.

Understanding the dynamics of multi-dimensional polarisation is of foundational importance to the study of cultural evolution, since it concerns how cultural diversity is generated and maintained, how information is transmitted within and between cultures, and how subcultures emerge. The present study makes a two-fold contribution to these foundational issues. First, while there are models investigating how divergent behaviour emerges between given groups (e.g. Axelrod, 1997; Boyd and Centola et al., 2007; Jansson, 2015; McElreath et al., 2003; Richerson, 2005; Tarnita et al., 2009), there is less work on how clearly defined cultural groups emerge in the first place. We build on this work by investigating the emergence of multi-dimensional polarisation within a society, how this affects the flow of information, and how it may lead to cultural fragmentation. Second, work on cultural systems (see Jansson et al., 2023) has focused on how intrinsic relations between cultural traits influence cultural transmission, mostly through content filtering. We will expand on this work by studying the emergence of cultural associations between beliefs whose contents are unrelated to one another.

Multi-dimensional polarisation is also a matter of urgent practical significance, since it has the potential to undermine democracy, increase voter dissatisfaction, and make bipartisan decision-making intractable. Of particular concern is the rise in factual belief polarisation (Rekker, 2022), since disagreements over the ‘basic facts’ undercut the common ground needed to resolve ideological disagreements. Yet, multi-dimensional polarisation has been observed in a wide variety of contexts, and there is substantial evidence that it is increasing globally (see e.g. Brugidou and Bouillet, 2023; Holmberg and Hedberg, 2011; Isaksson and Gren, 2024; Kahan, 2016), perhaps as a result of our increasing reliance on social media as a source of information (e.g. Ojea Quintana et al., 2022; Sullivan et al., 2020).

Recent empirical studies illustrate how unrelated beliefs align in real time. For instance, during the Covid pandemic, beliefs about the efficacy of public health measures correlated strongly with political views, with global trends showing left-leaning support for measures like masking (e.g. Allcott et al., 2020; Kerr et al., 2021; Ruisch et al., 2021), whereas in Sweden, the association was reversed (Carlander and Andersson, 2020), a partisan divide that increased over the first year (Jönsson and Oscarsson, 2021). Similar partisan development can be seen in opinions on energy sources, with left-wing support for wind turbines and right-wing opposition (Isaksson and Gren, 2024), while the case for nuclear power is reversed (e.g. Brugidou and Bouillet, 2023; Holmberg and Hedberg, 2011). Such partisan polarisation also extends to views on whether climate change is anthropogenic, whether violent crime has decreased, whether corporal punishment is an effective deterrent, and more (Kahan, 2016).

By exploring the role of source filtering, our results connect closely to the function of the collaborative filters widely used in recommender algorithms on social media platforms. Collaborative filters predict a user’s preferences or beliefs not by examining content directly, but rather by selecting and recommending items or opinions held by similar users. Previous modelling work has shown that collaborative filtering can itself drive polarisation by reinforcing existing preferences and reducing exposure to diverse viewpoints (e.g. Bellina et al., 2023; Santos et al., 2021). Much like source filtering, collaborative filtering acts as a similarity gate that promotes interactions primarily among like-minded users. Our analysis of the role of source filtering can shed new light on this process by explicitly modelling the formation of multidimensional belief packages and identifying the underlying dynamics by which similarity-based filtering gives rise to ideological clustering and polarisation.

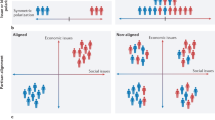

Given its theoretical and practical relevance, we thus focus on multi-dimensional polarisation, defined here as a society divided into groups whose beliefs are internally correlated and externally opposed. This leads to beliefs becoming subcultural markers indicating group membership and predicting positions on unrelated issues. We represent beliefs as binary propositions (P and its opposite \(\overline{P}\)). A society is maximally polarised on multiple dimensions when membership in one group strongly predicts multiple correlated beliefs, such that agents’ beliefs are highly correlated with those of their ingroup, and highly anti-correlated with those of the outgroup, regardless of their specific content. At the extreme, there are two dominant groups, where one group believes P1, P2, …, Pn, while the other believes \({\overline{P}}_{1},{\overline{P}}_{2},\ldots ,{\overline{P}}_{n}\). Though there are many ways to measure polarisation (Bramson et al. 2017), our focus here is on the correlation of beliefs and the frequency of extreme outcomes.

Background

We begin with an overview of previous empirical work on the psychological basis of individual belief updating, and how this can inform the emergence of polarisation. After that, we summarise the main findings from several different theoretical approaches which have used mathematical modelling to explore the effects of individual drivers on the emergence of associations between beliefs and polarised groups. First, we will consider the issue of group formation and cultural transmission contingent on groups. This will then be connected to trait relations in cultural systems, before we move on to their interplay with social and complex systems. Finally, we will consider work where polarisation emerges even when beliefs are based on arguments and agents are epistemically rational.

Individual belief change

There are several psychological dispositions that may lead to the emergence of polarisation when combined with biased social interaction. Festinger’s (1957) theory of cognitive dissonance posits that individuals experience discomfort when confronted with information that contradicts their beliefs. To resolve this discomfort, they may reject the conflicting information or modify their beliefs. Over time, this can lead to entrenched views and reluctance to engage with opposing perspectives (Festinger, 1957). This consequence may be exacerbated by a confirmation bias (Lord et al., 1979), where individuals have a propensity to seek out, interpret, and remember information in a manner that confirms their pre-existing beliefs. Such a bias not only strengthens people’s convictions but also reinforces them by filtering the type of information people engage with. As a result, opposing views are either disregarded or undervalued, widening the gap between different belief systems (Nickerson, 1998).

Apart from filtering information, theories of cognitive consistency, confirmation bias and social balance theory (Heider, 1958) suggest that people will seek out other people with similar views. Indeed, it has been widely observed that interaction occurs more frequently between similar people, a principle known as homophily (McPherson et al., 2001). As people update their beliefs in interaction with similar peers, the beliefs of group associates become increasingly aligned. Eventually, when exposed to a new belief within a group context, individuals may adopt other associated beliefs—even if they are unrelated—to avoid the discomfort of holding beliefs that are inconsistent with those of the group. In some cases, biased responses to new information may be produced by a need to protect social group identity (Kahan, 2016, 2017). Thus, social identities emerge, where groups become associated with sets of beliefs that are not necessarily interrelated, a process that is exacerbated if people foster a sense of belonging and differentiation from other groups (Tajfel and Turner, 1979). This collective belief adoption further entrenches the group’s shared identity, creating a feedback loop where identity influences belief acceptance and vice versa. Over time, these bundled beliefs become emblematic of the group’s identity, even if the contents of the individual beliefs in the set have no logical, evidential, or other inherent connection with one another. This intertwining of belief systems and identity underscores the powerful role of group dynamics in shaping individual cognition and behaviour, and may play an important role in cultural evolution.

These individual and social drivers of belief change may contribute to the emergence of polarisation online, since geographical, economic, and other traditional barriers to group formation are absent, thus making greater room for group formation on the basis of similarity of belief. Indeed, it has been noticed that this leads to the formation of filter bubbles, in which people are insulated from counter-evidence, or echo chambers, in which they are additionally distrustful of those with opposing views. This, along with the collaborative filters in use in various recommender algorithms, can serve to further reinforce polarisation (Nguyen, 2020).

Groups and cultural transmission

The emergence of polarised groups seems to be an understudied phenomenon in the literature on cultural evolution, especially concerning the formation of groups that share logically or probabilistically unrelated beliefs. There are a few notable exceptions, which we review below, along with some related work on modelling group formation and, separately, similarity biases in social transmission.

Group formation

Studies of group formation can be instructive for understanding polarisation and identity by elucidating the mechanisms, such as conformist transmission and homophily, that drive the emergence and entrenchment of distinct cultural groups with differing norms and values. These studies reveal how social learning and adaptation to group norms can intensify intra-group cohesion and inter-group differentiation, for example through conformist transmission (Henrich and Boyd, 1998) if individuals disproportionately adopt prevalent traits within their group; through imitation and group pressure (Richerson and Boyd, 2008); and through cultural group selection based on cooperation and coordination (Boyd and Henrich, 2004; Richerson, 2005). These studies, however, pertain to group-based prosocial behaviour rather than beliefs and attitudes, which are the focus of the present study.

Similarity-biased transmission

It has been suggested that people are more likely to adopt cultural traits from people who are similar to them in terms of their age, gender, social status, or other cultural characteristics (e.g Henrich and McElreath, 2003), a phenomenon that is related to homophily, and is observed already among infants (Mahajan and Wood et al., 2013; Wynn, 2012). This has been thought to be an adaptive strategy, since similar people are more likely to live in similar contexts and share similar challenges (Henrich, 2016), and it can facilitate coordination (Henrich and Henrich, 2007; Jansson, 2015; McElreath et al., 2003). Supporting this, formal modelling (Smaldino and Velilla, 2025) has shown that learning strategies biased towards socially similar others can evolve and outperform less selective strategies in heterogeneous environments.

A similarity bias plays a central role in Axelrod’s seminal model on polarisation (1997). Each agents is assumed to have variants of a number of traits, and may replace a trait variant by copying that of their neighbour, depending on the similarity between the agents: the probability that a variant will be transmitted from one agent to another is proportionate to the number of variants they already have in common. In the long term, all agents will adopt the same set of trait variants, but in the midterm, simulations result in disparate local clusters of agents with identical sets of variants within the clusters, that is, polarisation. Though seminal, this model has some limitations for the study of polarisation, in that it assumes that agents live on a lattice and interact only with their immediate neighbours, that it is always the same set of four agents who interact, and that all trait varieties are nominal, and thus incomparable. This means that the model cannot be generalised to well-mixed populations or other, especially small-world, topologies (c.f. Jansson, 2013) and that it is restricted to counting the number of differing varieties to measure distances between trait clusters. Moreover, multi-dimensional polarisation does not emerge at the population level in this model: even if some neighbouring clusters are maximally contrarian, they are typically overlapping in some variants, and at the global level, the correlation between traits is close to zero. This is not measured in the original manuscript, but in our own simulations of Axelrod’s model with two or more traits and two variants, we get a ϕ coefficient typically below 0.03.Footnote 1

Relations between beliefs

In this paper, as in that of Axelrod, we are interested in the clustering of variants of several beliefs. In general, we allow for cultural traits to be interrelated, directly or indirectly influencing the transmission of each other, thus taking a systemic approach to cultural evolution (Buskell et al., 2019). Such relations can exist for example because of logical or physical constraints, or emerge culturally (Jansson et al., 2023) and form what we could call trait associations. We will build further on a modelling framework (Jansson et al., 2021) where cultural traits are compatible to various degrees. When agents are exposed to a new trait, such as a belief, either through individual discovery or, more often, through social transmission, they evaluate it in terms of its compatibility to their current knowledge (i.e. set of previously acquired traits) and accept it with a higher probability the more it fits. If traits are already clustered in terms of their intrinsic relations, such content filtering produces path-dependent processes where the acquisition of one trait over another early on can have vast effects on what kind of traits agents can acquire later. At the population level, we see polarisation between groups with internally coherent traits based on exogenously given restrictions.

In this terminology, we are interested in (i) the emergence of cultural associations between beliefs with unrelated content, and (ii) the processes by which the population splits into factions adopting contrarian belief systems. While clusters of trait packages do emerge culturally in Axelrod’s model, as we noted above, traits are not associated at the population level, in the sense that possessing a trait A predicts the possession of some other trait B.

One way for trait relations to emerge is if not only the traits themselves are transmitted, but also information about how they are related, that is, if traits are transmitted in packages (with copying errors, such that links can form and break) (Yeh et al., 2019). However, this process does not lead to polarisation, but typically convergence towards low diversity between individuals. Another approach is to equip agents with subjective preferences for traits and individual associations between them that they learn and transmit (Goldberg and Stein, 2018). Senders display a random pair of their preferred traits. Receivers increase their association between the observed pair of traits and strengthen or weaken their preferences for one of these traits, such that associated traits have similar subjective valence. Eventually, agents converge on how traits are associated in clusters, at which point they will also develop consistent preferences for or against all traits in each cluster. Polarisation and population-level associations can thus emerge through associative diffusion. The mechanisms at play are similar to those of content filtering, with the addition that first agents need to agree on how traits are related, but then they adopt preferences for them based on these relations. Another indirect addition is that this model includes repulsive influence, in that exposure to traits an agent values negatively leads to negative updating. This is a common driver of polarisation in theoretical models, but as we will discuss below, there are reasons to avoid including such assumptions, and a remaining challenge is to explain polarisation without it. In this paper, we will investigate the possibility for trait associations to emerge at the population level without agents representing or transmitting them, and without negative updating, that is through filtering dynamics alone. Can source filtering itself lead to polarisation?

Social and complex systems

Polarisation is a central research issue in the study of social systems, since it directly impacts social cohesion, potentially leading to increased conflict and reduced trust in institutions, and has implications for group identity, political dynamics, and societal stability. Understanding the process of polarisation has been listed as one of the important unresolved problems of sociology (Bonacich and Lu, 2012), and the question was posed by Abelson as a modelling challenge already in 1964 as ‘what on earth one must assume in order to generate the bimodal outcome of community cleavage studies’. Three main lines were suggested: First, networks can be disconnected, from which the potential for bimodal outcomes follows trivially. Second, there can be negative updating, that is, repulsive influence in some form, as mentioned above, and which we will discuss more below. Third, there can be some sort of evolving networks, where influence rates between individuals vary and potentially change over time, which is what the source filtering achieves. We are thus most interested in following this third line.

A relatively recent review of models on polarisation (Flache et al., 2017) has identified three major types based on their assumptions and outcomes (partially overlapping the three explanations above): social influence is either assimilative, similarity-based or repulsive.

Assimilative and repulsive influence

The take-home message from the first type of models is straightforward: with assimilative social influence, that is, when agents try to reduce opinion differences with everyone they encounter, a cluster of connected agents will come to a consensus (see e.g. Hegselmann and Krause, 2002). These models can serve as a baseline from which we need to add an assumption on either structural properties of the beliefs (e.g. Buskell et al., 2019) (or of the population, in assorted networks) or heterogeneous social influence.

Adding repulsive influence, where agents update in the opposite direction from dissimilar others, can generate extreme bipolarisation (Flache et al., 2017). Some basis for such psychological reaction may partly be found in the backfire effect (e.g. Nyhan and Reifler, 2010), but in general, evidence for the significance of such processes is scarce (Flache et al., 2017; Takács et al., 2016), and existing studies may have methodological weaknesses (see e.g. Mäs and Flache, 2013, for references). Another potential issue when trying to explain the coevolution of polarisation and identity is that repulsive influence often presupposes an existing group mentality. However, in strategic, payoff-based contexts, individuals who observe a dissimilar majority may profit by deliberately choosing the opposite action, allowing repulsive influence to emerge without prior group identities (Efferson et al., 2016). Some earlier work has combined attraction and repulsion systematically, quantifying the effects of homophily versus distancing (Macy et al. 2003; Mark, 2003).

Similarity-biased influence

The remaining assumption is that agents are differentially influenced by other agents depending on their (typically epistemic) similarity to themselves. We have discussed the basis for this assumption above within the field of cultural evolution and it is related to Abelson’s third line presented above. As with Axelrod’s model, models within this category typically give rise to clustering, but not the type of extreme clustering that is associated with bipolarisation and identity formation generated by repulsive influence (Flache et al., 2017). There are many variants of Axelrod’s model and similar approaches (see Castellano et al., 2009, for a review). In a common and related type of models, there is a continuous opinion space over one issue, and agents end up in clusters that have converged on an opinion that is the average of their own and those of their most similar peers (e.g. Deffuant et al., 2000; Hegselmann and Krause, 2002). The clusters emerge due to self-reinforcing feedback between influencing and agreeing with similar agents, but they do not end up at the extreme ends of the opinion space.

There have been several attempts to generate more extreme polarisation. One way is to add external signals, such as from prominent leaders or interactions with reality, similar to epistemic factionalisation (Hegselmann and Krause, 2015; Weatherall and O’Connor, 2021). Another way is to make interaction networks coevolve with similarity (Centola et al., 2007). Some recent work has aimed directly at addressing the issue of generating bipolarisation without repulsive influence. One approach implements reinforcement learning, where even agents who share an opinion can become more extreme by the reinforcement that the coordination entails. Though this often leads to consensus (c.f. Jansson et al., 2015), bipolarisation is possible with a network topology (Banisch and Olbrich, 2018). Reinforcement can also work by separating opinions from arguments, so that like-minded agents can provide each other with new arguments that strengthen their opinion. With a limited memory for old arguments and a sufficient extent of assorted homophilous interaction, bipolarisation ensues (Mäs and Flache, 2013). Polarisation can also be a transient phase when groups move in the same direction, arising when one groups updates views on single issues more slowly than the other (Eriksson et al., 2024). Partisan influence can also be grounded in economic risk: when risk-averse agents face unequal pay-offs from cross-group interaction, a similarity bias can lock populations into affectively polarised states (Stewart et al., 2021). Our approach contrasts from these models in that we aim to study groups in terms of multidimensional polarisation and emergent relations between beliefs, and that we do not assume assorted interactions.

In their review, Flache et al. (2017) identify two perspectives in the flora of models that take similarity into account: either the similarity emphasises the cognitive process of how the message itself fits the mindset of the recipient, or it emphasises the relation of the recipient to the messenger, though there are models where the two approaches are combined (Galesic et al., 2021). We will here formalise these two perspectives, corresponding to content versus source filtering, and show that the latter can produce polarisation without intrinsic connections between beliefs.

Epistemic filters

In the context of belief systems, the cognitive processing of information in the light of relations between beliefs (Jansson et al., 2021) could be referred to as epistemic filtering, in which the two perspectives (Flache et al., 2017) are analogous to the cognitive mechanisms that comprise epistemic vigilance, by which people evaluate the credibility of communicated information, on the basis of both the coherence of new information with prior beliefs (akin to content filtering), and the trustworthiness of their sources (akin to source filtering), primarily as protection against deception or misinformation (Sperber et al., 2010). However, while mechanisms of epistemic vigilance are sometimes thought to be innate, our models explore the minimal conditions for epistemic filters to emerge culturally, in contexts where agents lack the information to assess the credibility of informants, beyond their belief systems.

There are some models that investigate the effects of processes resembling epistemic filtering on polarisation, involving either boundedly rational or Bayesian agents, and focusing on processes related to either content or source filtering. Polarisation may result from rational processes of belief formation and updating. For instance, agents who employ a rational strategy of maximising coherence in their beliefs may nonetheless polarise, as a result of cognitive limitations, and insufficient evidence (Singer et al., 2019). In line with content filtering, a recent model assumes biased processing (Banisch and Shamon, 2023), in which agents accept an argument depending on how well it fits with their present opinion. Opinions are based on the net number of currently endorsed arguments for versus against an issue, and bipolarisation emerges if the processing bias is strong. This is analogous to having two clusters of arguments that are interrelated, by their support of a stance, which together with content filtering can result in polarisation. These results are in line with previous findings that content filtering can regenerate underlying belief clustering (Buskell et al., 2019).

Similarly, agents who follow a rational strategy of Bayesian conditionalisation can nonetheless polarise for a variety of reasons: because they update their beliefs on conflicting interpretations of ambiguous evidence (Dorst, 2023); because they start out with different priors, reflecting opposing views on what bearing the evidence has on a hypothesis (Jern et al., 2009; Ojea Quintana et al., 2022); or because they start out with a different space of hypotheses to consider (Kelly, 2008). In fact, it has been shown that ideally rational Bayesian agents, receiving an infinite stream of identical evidence, tend to polarise at the limit, unless they satisfy strong constraints that have no rational basis (Nielsen and Stewart, 2021).

In social network epistemology, there are a number of models which explore the emergence of polarisation in populations of rational Bayesian agents in which beliefs are represented as probability assignments to propositions, or credences (O’Connor and Olsson, 2013, 2020; Pallavicini et al., 2021; Weatherall, 2018). Of particular relevance here is a model in which polarisation can emerge in populations of Bayesian agents who have access to non-testimonial, empirical evidence, in addition to evidence on the basis of testimony (Weatherall and O’Connor, 2021). The agents handle testimony in a way that is akin to source filtering, since the likelihood that an agent will update her credences in light of an informant’s testimony depends on how much she trusts the informant, which in turn depends on how similar the informant’s credences are to the agent’s own prior credences. Importantly, and differently from our approach, the evaluation of trustworthiness includes the credence in the belief to be updated. Depending on the level of mistrust in dissimilar agents, the most typical outcomes are either true consensus, or polarisation into all combinations of beliefs when the level of mistrust is so high that agents disregard any agent with contrasting priors. When including repulsive influence, or anti-updating, there is a level of mistrust in between the two typical outcomes where beliefs sometimes come to correlate in the way that we are interested in here. It is also demonstrated in the specific case when agents either update towards true consensus or mistrust agents if and only if they disagree on all issues, in which case the correlation between beliefs is built into the assumptions.

In our models, we aim to find more general conditions and to gain a fuller understanding of this kind of processes by introducing an arguably simpler model with binary beliefs, without empirical grounding, in which agents rely purely on source filtering (where the belief to be added is not included in the evaluation of similarity) and without repulsive influence.

Model

We base our models on an existing framework developed for studying the dynamics of cultural systems and trait filtering (Jansson et al., 2021). This framework assumes that there is a universe of traits and relations between them. The relations can in principle be represented on a scale, representing the degree of consistency (for positive values) or inconsistency (for negative values). This structure can thus be represented as a weighted network. There are links only between beliefs that have an intrinsic relation.

Consider, for example, the following set of beliefs:

-

(A)

Unregulated development of advanced AI can lead to existential risks for humanity.

-

(B)

It is imperative to halt certain AI advancements until proper safety measures are in place.

-

(C)

AI, regardless of its advancement, will always be a tool and remain under reliably safe human control.

-

(D)

Accelerating AI advancement is crucial for addressing humanity’s pressing challenges and should not be delayed.

The beliefs A and B are consistent, and so are C and D. However, A and B are each largely incompatible with each of C and D. In this case, we have a complete network of beliefs.

Now consider instead the following set of beliefs:

-

(P)

Climate change is primarily driven by human activities.

-

(Q)

Climate change is not primarily driven by human activities.

-

(R)

Vaccines are safe and effective for the majority of people.

-

(S)

Vaccines are not safe and may cause more harm than good.

The beliefs P and \(\overline{\rm{P}}\) are inconsistent, and so are Q and \(\overline{\rm{Q}}\). However, P and \(\overline{\rm{P}}\) are wholly unrelated to Q and \(\overline{\rm{Q}}\).

The question is how people will process the beliefs from these two sets. We assume epistemically rational agents who process new information in light of their prior beliefs. In a social interaction, receivers have two main ways to filter incoming information: either on the basis of the content of the belief, and how it coheres with their current beliefs, or on the basis of the reliability or trustworthiness of the source of information. We operationalise these strategies, respectively, as content filtering, where receivers reject information that is too inconsistent, on average, with their current beliefs, and source filtering, where receivers rejects traits presented by a sender, the source, whose belief system is too inconsistent with their own (Jansson et al., 2021). Source filtering is related to the similarity bias, as discussed in the Background section.

In the first example set of beliefs, there is already clustering with respect to coherence, so we expect each agent to end up with either {A, B} or {C, D} with both types of filtering, since acquiring one belief from either of these sets allows for acquisition also of the other belief, but the beliefs from the other set are both inconsistent with the agent’s set of beliefs, making also any other agent that carries them incompatible. Indeed, previous work (Buskell et al., 2019) has shown that not only will the two clusters be the dominating sets, but they will also tend to be equally common with a small innovation rate, that is, if agents on rare occasions come up with consistent beliefs themselves. Thus, structural constraints of beliefs are mirrored in polarisation of opinion.

In the second example set of beliefs, agents are also logically restricted to holding a maximum of two beliefs. However, for each belief, there are two beliefs with which it is equally consistent. There are four consistent maximal sets of beliefs: PQ = {P, Q}, \(P\overline{Q}=\{P,\overline{Q}\}\), \(\overline{P}Q=\{\overline{P},Q\}\) and \(\overline{P}\overline{Q}=\{\overline{P},\overline{Q}\}\), which are equally favoured at the outset. Following the first example, we would expect a factionalisation, where the population is distributed over these four sets. We are interested in those cases in which the population is primarily composed of two groups, with maximally opposing sets of beliefs, that is, either PQ and \(\overline{P}\overline{Q}\) or \(P\overline{Q}\) and \(\overline{P}Q\). A related topic of interest is when believing P correlates with believing either Q or \(\overline{Q}\). In this case, a relation between two beliefs has emerged culturally and led to bipolarisation along multiple dimensions. If you live in such a society, if you adopt one belief, then you are likely to adopt a full package of beliefs, and any of the beliefs in the package functions as a signal for membership of a cultural subgroup.

We are here mainly interested in the second kind of example. We thus assume that there is a universe of propositions, closed under negation, constituting the possible objects of agents’ beliefs. Thus, for each proposition, P, that is a possible object of belief, its negation, \(\overline{P}\), is also a possible object of belief. We will generalise this case beyond two pairs of contrarian beliefs. For three such pairs, there are 23 = 8 maximal sets of beliefs, forming \(\left(\begin{array}{l}8\\ 2\end{array}\right)=28\) combinations of two sets, only four of which are maximally opposing (such as, e.g., \(\{P,\overline{Q},R\}\) and \(\{\overline{P},Q,\overline{R}\}\)), making it less likely that the two largest factions are maximally opposing by chance.

For equations and further technical details on the following models, see Sections S1–S3 in the supplementary material.

One inconsistent pair

In our simplest case, there is only one pair P and \(\overline{P}\) of inconsistent beliefs. Let x0, xP and \({x}_{\overline{P}}\) be the proportions having no belief, P and \(\overline{P}\), respectively, where P and \(\overline{P}\) are in contradiction, and cannot be held at the same time. In this model, there is no difference between a content and a source filter. Agents with no beliefs acquire a given belief at rate α when encountering an agent with the belief in question. Agents with a belief cannot acquire the other belief. Agents are replaced by naïve agents at rate β and those without beliefs invent one randomly at rate μ. Let \(i\in \{P,\overline{P}\}\) be a belief (and \(\bar{i}\) the other belief – note that by convention \(\overline{\overline{P}}=P\)). Then

where x0xi is the probabity that a naïve agent encounters one with belief i and μ/2 is the probability that a naïve agent invents (or discovers by individual exploration) i (and the same probability that they instead invent \(\overline{i}\)).

Two inconsistent pairs

Apart from the notation above, let xQ and \({x}_{\overline{Q}}\) be the proportions of beliefs Q and \(\overline{Q}\), respectively, where Q and \(\overline{Q}\) are in contradiction, and cannot be held at the same time. Let xij (=xji) be the proportion of agents holding both belief i and j, for any \(i,j\in \{P,\overline{P},Q,\overline{Q}\}\), where \(j\,\notin\, \{i,\overline{i}\}\). Since agents can now have more than one belief, the source filter will have an effect. We assume that agents do not acquire any beliefs from other agents who hold any contradictory belief to themselves. If no beliefs are in contradiction, then receivers with no beliefs in common to the source acquire one of the source’s beliefs at rate α0, and receivers with one belief in common acquire the other belief at rate α1. We can incorporate a similarity bias by assuming that α1 > α0. The change rates of frequencies are

The explanation for the first equation is as follows: only a naïve agent can acquire belief i as its single belief, by interacting with an agent who has the belief. If the other agent also has another belief, then the probability it will transmit i is halved. An agent who has i can acquire another belief by interacting with an agent who has j or \(\overline{j}\). If the other agent also has i, then the probability of transmission is α1. Agents are replaced at rate β and an innovating agent who is naïve has probability \(\frac{1}{4}\) to innovate i, while one who has i has probability \(\frac{2}{4}=\frac{1}{2}\) to innovate another consistent belief (assuming that agents arrive independently at any of the four beliefs with equal probability and discard it if the agent already has it or if it is inconsistent with the present belief).

For the second equation, only those who already have one of the beliefs i and j can gain ij. An i agent can interact with a j agent, or vice versa, with transmission probability α0, or any of them can interact with an ij agent, with transmission probability α1, since they share a belief. Agents are replaced at rate β and an innovating i or j agent has probability \(\frac{1}{4}\) to choose the other belief.

External signals

We have so far assumed no intrinsic properties of the beliefs that could bias their acquisition or transmission. Such properties could, however, influence the belief dynamics. For example, if one of the beliefs in an inconsistent pair corresponds to physical reality and can be verified empirically, it might be expected to have an advantage over its negation. We can model this by (i) allowing for different innovation rates μi for each belief i, representing for example the fact that it should be easier to come up with a new belief on your own for a state of affairs that you can observe yourself, and by (ii) introducing a loss rate γi for each belief i, representing for example the fact that it can be disproven by empirical observation. If we replace the ellipsis (…) below by the terms in the corresponding equation in Eq. (2) (where μ and β can be set to zero if they are to be replaced by the new variables), then the equations become

Here we assume that agents with two beliefs can lose only one of them at a time, and the belief that is at risk of loss is chosen uniformly at random (with probability \(\frac{1}{2}\)).

Agent-based model

The number of equations in the population dynamics models increases exponentially with the number of beliefs, so to study larger belief systems we need to abandon the equation-based approach and run simulations. A simulation-based approach also allows us to study the effects of stochastic events. We utilise an existing modelling framework (Jansson et al., 2021) where cultural traits are represented as nodes in networks with links between them representing compatibilities. We adapted the framework for the case of contradicting propositions that are unrelated to other propositions along with source filtering. This model does not include external signals.

In the simulations, there are n contradicting pairs of propositions available to be discovered. There are N agents, each with an individual belief system. At the outset, agents are naïve, but acquire beliefs through innovation (by sampling from the universe of belief pairs) and copying from other agents.

The agents meet in random interactions. One round of interactions, or a time step, includes copying, innovation and a replacement process. The simulation runs for T time steps.

First, each agent, the receiver R, samples one other agent as an information source S. If S has no beliefs that are inconsistent with those of R (i.e. \(\overline{X}\) if R believes X), then one belief b will be sampled from the beliefs of S. If the receiver does not already possess b, then they will copy it with probability α0 if S and R have no beliefs in common, and otherwise with probability α1 > α0, if they already share some belief.

Each agent then invents a new belief with probability μ and adds it to their own sets of beliefs if it does not contradict any of their current beliefs. Finally, each agent is replaced by a new naïve agent with probability β.

See Algorithm S1 in Section S5 of the supplementary material for pseudocode and Additional information for a link to the program code.

Results

We will present the major findings from analytical treatments and simulations, and some illustrative examples of the models, in the same order as in the previous section, starting with the simplest case and adding belief pairs and external signals. We refer to the Supplementary Material for a further exposition.

One inconsistent pair

With only one pair P and \(\overline{P}\) of inconsistent beliefs, due to innovation, the population does not fixate at either belief, but instead they are equally common at equilibrium. Thus, polarisation emerges with rather minimal assumptions. The larger the value of the learning rate α or the innovation rate μ, the larger the fraction of agents with a belief, while the replacement rate β has the opposite effect. For example, for α = 0.01 and β = μ = 0.001, each belief is possessed by 45% of the population at equilibrium. See Section S1 in the supplementary material for an algebraic expression.

Two inconsistent pairs

With two pairs P versus \(\overline{P}\) and Q versus \(\overline{Q}\) of inconsistent beliefs, the equilibrium frequencies are typically much larger for having two beliefs than for having only one if the transmission rate α1, when agents have a belief in common, is much larger than the rate α0, when they do not. At equilibrium, the population is divided evenly between the four groups PQ, \(P\overline{Q}\), \(\overline{P}Q\) and \(\overline{P}\overline{Q}\). This is expected, given that we have unbiased diffusion with innovations in a well-mixed population. For example, for α0 = 0.01, α1 = 1 and β = μ = 0.001, the four groups each collect 23% of the population, while a bare 0.5‰ have only one belief at equilibrium.

However, while this shows the frequencies to which the population will tend, it can take a long time before they are reached, if there is an imbalance in frequencies at the beginning. For a wide range of parameter values, for a long period, two opposite pairs will dominate, as long as two non-contradictory beliefs are present at the outset. In the following examples, we start with 10% of the population holding a belief in P and another 10% in Q, with the remaining 80% being naïve. With the configuration above, the belief package PQ quickly starts to dominate (reaching 90% within 100 time steps), then it takes about 200,000 time steps until the opposite package \(\overline{P}\overline{Q}\) catches up to become almost equally common (differing at most ten percent from PQ), while it takes more than two million time steps until the other packages reach similar levels (differing at most ten percent from \(\overline{P}\overline{Q}\)). By decreasing the innovation rate, the convergence to the equilibrium becomes even slower and the beliefs remain highly correlated for a long time. See Fig. 1 for an example of the frequencies of and correlations between beliefs over time, and the maximum correlation between beliefs P and Q for different values of α0 and μ. The fractionalised division into maximally opposing groups, such as PQ versus \(\overline{P}\overline{Q}\), is relatively more stationary than one into only partly opposing groups, such as PQ versus \(P\overline{Q}\). Starting at a maximally polarised state, with \({x}_{PQ}={x}_{\overline{P}\overline{Q}}=\frac{1}{2}\), for example, with the parameter values of the top panel of Fig. 1, it takes 17 times longer to reach equilibrium than from a partly polarised state. With a larger μ = .0001, it takes 40 times longer.

The dynamics are studied in more detail in Section S2 and Fig. S1 in the supplementary material, but in brief, PQ rapidly takes the lead if P and Q are the initially present beliefs and α1 is large. The innovation rate μ regulates the dominance of PQ versus the convergence towards a uniform distribution of belief combinations. With a dominance of PQ, the single beliefs P and Q are rare, if α1/α0 is large. Agents who believe in one of the more common \(\overline{P}\) or \(\overline{Q}\) can always be influenced either by agents believing \(\overline{P}Q\) or those believing \(P\overline{Q}\), respectively, while agents who believe \(\overline{P}\overline{Q}\) can influence agents with either of the single beliefs, and thus have an advantage, until they become so common that the four beliefs P, \(\overline{P}\), Q and \(\overline{Q}\) are equally common in the population. Put simply, source filtering turns shared beliefs into strong pathways for convergence: once a two-belief bundle is widespread, agents holding only one of its component beliefs are more likely to be drawn into the full bundle, while those with an incompatible belief tend to be absorbed by the opposing bundle. Whichever incompatible belief this is, the opposing bundle can recruit, while only one of the mixed bundles can, further inhibiting growth by a negative feedback from the small group size.

In Section S4 and Tables S1 and S2 in the supplementary material, we also present outcomes from systematically varying the parameter values (on a 10-logarithmic scale). When β ≥ α0, there is not enough time for beliefs to spread unless also μ ≥ α0, but in that case beliefs do not correlate. Apart from those cases, the two largest groups tend to be the maximally opposing PQ and \(\overline{P}\overline{Q}\), with beliefs correlating at various degrees. This outcome is especially common, with highly correlated beliefs, when α1 ≫ α0 ≫ β, μ, where ≫ does not mean asymptotically larger, but about 10–100 times larger. In those cases, almost the full time to equilibrium is spent with the opposing groups being roughly equally common, with maximal correlations typically well above 0.3, reaching 0.9 in some cases.

External signals

Some beliefs may be easier to invent or more easily lost, for example, because they correspond better or worse with the state of the world, supported or counteracted by readily available evidence that individuals can experience themselves. We modelled this by allowing different innovation rates μi for each belief i and by introducing a variable γi for the loss rate of the same variable. Two key differences from the original model are: (i) PQ can become the majority group even when the only existing initial beliefs in the population are \(\overline{P}\) and \(\overline{Q}\). The advantage of P is thus carried over to the unrelated Q. (ii) It is possible for only one of the beliefs to become associated with another, that is, \(\overline{P}\) can become associated with \(\overline{Q}\), while P occurs equally often with Q and \(\overline{Q}\), or vice versa. See Fig. 2.

a P and Q become associated, with μP = 0.0002 and \({\mu }_{\overline{P}}={\mu }_{Q}={\mu }_{\overline{Q}}=.0001\). b \(\overline{P}\) becomes associated with \(\overline{Q}\), while P is not strongly associated to either, with \({\gamma }_{\overline{P}}=.0001\) and μ = 0.001. In both panels, α0 = 0.01, α1 = 1 and β = 0.001, with initial frequencies \({x}_{\overline{P}}=.1\), \({x}_{\overline{Q}}=.1\) and x0 = 0.8.

These additional possible outcomes capture further observed phenomena. As an example of (ii), consider P from earlier, that climate change is driven by human activities, but let Q instead denote the belief that redistribution through taxation can stimulate economic growth. A hundred years ago, people typically did not believe in P, but given evidence, it is now dominating, and believing P is not a strong predictor of a belief in Q. Meanwhile, the minority that still believe \(\overline{P}\) is disproportionately represented on the right wing, who typically also believe Q. See Section S3 and Fig. S2 in the supplementary material for more examples.

Agent-based model

We varied the parameter space on a logarithmic scale, with α0 ∈ {0, 0.001, 0.01, 0.1}, β ∈ {0.0001, 0.001}, μ ∈ {0.0001, 0.001, 0.01} and N ∈ {100, 1000}. We fix α1 = 1.Footnote 2 We included α0 = 0 to study the limit tendency for small α0 as, in contrast to the equation-based model, we found that the lack of nonbiased transmission did not exclude the possibility of emergent belief associations. Varying β had little effect, and the runtime of the simulations grows polynomially with N, so increasing N further would severely increase the runtime.

We set T = 105 and ran 100 simulations for each combination of parameter values. We made measurements every 100 time steps, providing 1000 measurements. We calculated the average from the last 100 measurements, that is, they include only those made after 90,000 time steps, to safely exclude the initialisation period. We first ran the simulations for sets of two belief pairs, and then for three. With random processes, we do not need to fix the initial distribution of beliefs, but all agents start out naïve and beliefs will enter the population when someone invents (discovers) them.

Figure 3 shows the full simulation runs for two sets of parameter values, the left panels with β > μ and two belief pairs, and right panels with β < μ and three belief pairs. The top panels show the first run, as an example, while the bottom panels include all 100, with the mean value of all of them in thick lines. We renamed the beliefs after each run, so that the most common belief set is always PQ. Even if most agents have no beliefs when μ is small, for these parameter values, among the agents with beliefs there is a clear dominance of groups with two opposite sets of beliefs, at roughly equal frequencies, even when there are three belief pairs, while the other groups lag far behind at low frequencies. The correlation between the two beliefs in that scenario is as high as ϕ = 0.93 and the opposing groups are always the two leading ones. In the case with three beliefs, ϕ = 0.79 and opposing beliefs are leading 84% of the time. These parameter values thus exhibit strong bipolarisation with highly correlated beliefs.

The top panels show the first of the runs. The bottom panels show all 100 runs along with the mean in a thick line. In all panels, α0 = 0.001, α1 = 1. The other parameter values to the left are β = 0.001, μ = 0.0001 and there are 1000 agents. The parameter values to the right are β = 0.0001, μ = 0.001 and there are 100 agents.

Results for all combinations of parameter values are presented for two outcome measures in Fig. 4. The top two rows show the average values of the correlation coefficient ϕ, a proxy for the association between beliefs. The bottom two rows show the average values of q, which measures how close in frequency the opposing group is to the leading group compared to how close it is to a partly overlapping group, assuming that the largest two groups are opposing (otherwise q is undefined or can be set to 0). This value serves as a proxy of bipolarisation. If q > 0, then the largest groups on average are opposing. If q > 1, then there is strong bipolarisation where not only the two leading groups are opposing, but the frequency gap to any mixed group is larger than the gap between the opposing ones. The figure shows that q > 0 in most cases where α0 < 0.1 and that in these cases, typically also q > 1, with large ϕ, except when α0 is large and for large μ in large populations. This thus suggests that there is strong association of beliefs and strong bipolarisation for a wide range of parameter values, except when unbiased and individual learning is common.

The two columns to the left are for two belief pairs and the two columns to the right for three. The top two rows show the average correlation coefficient ϕ and the bottom two rows the dual dominance q, for different values of N, β, α0 and μ. Diagonal stripes indicate that ϕ was undefined at least 10% of the time (with the colours indicating the average value for the remaining time) or that q is undefined since partly overlapping groups were on average larger than the group opposing the leading group.

For a fuller picture, we report other measures as well in Tables S4 and S5 in the supplementary material (see Section S5 and Table S3 for a description of the measures). Among these measures, we are interested in how often the two most common groups of beliefs still tend to contradict each other completely, that is, either of the pairs PQ and \(\overline{P}\overline{Q}\), or \(P\overline{Q}\) and \(\overline{P}Q\). If there is no tendency for pairs of groups to co-occur as the largest ones, then the expected frequency for this to happen for two belief pairs is \(\frac{1}{3}\approx 33 \%\) and for three it is \(\frac{1}{{2}^{3}-1}=\frac{1}{7}\approx 14 \%\). In the simulations, it happened in almost all cases where α0 < 0.1 (in the case of two belief pairs, it happened also then, if N = 100, or α, β > 0.0001). The median proportion across all simulations is 85% with two belief pairs and 46% with three, well above chance. The median correlations are ϕ = 0.57 versus ϕ = 0.36. When α0 > 0, correlations range from ϕ = 0.11 to ϕ = 0.86 with two belief pairs and ϕ = 0.95 with three.

Polarisation and association of beliefs is strongest for small parameter values, including α0. In the equation-based model, there has to be also unbiased transmission (α0 > 0), but in the agent-based model, we get the overall strongest results when α0 = 0. These findings are in line with the analytical findings from the equation-based model that the group opposing the leading one benefits from a small ratio of α0/α1, but further shows that discrete stochastic events can replace unbiased transmission.

To give a sense of the evolution of beliefs beyond summary measures, in Fig. 5 we present the first 10,000 steps for eight combinations of parameter values, equally divided between α0 ∈ {0.001, 0.01}, β ∈ {0.0001, 0.001}, μ ∈ {0.0001, 0.001} and N ∈ {100, 1000}, and with two belief pairs in the left panels and three in the right panels. In the bottom panels, where α0 > β > μ and N is large, while the second group tends to be the opposing one, one group dominates rather than two. In the other cases, we see more bipolarisation.

Each panel shows 100 simulations runs, with the means of all frequencies in bold, along with a shaded area showing the standard error of the means. In the left panels, there are two belief pairs and in the right panels there are three. In all panels, α1 = 1. The parameter values are: a α0 = 0.001, β = 0.0001, μ = 0.001 and N = 100; b α0 = 0.01, β = 0.001, μ = 0.001 and N = 100; c α0 = 0.001, β = 0.0001, μ = 0.0001 and N = 1000; d α0 = 0.01, β = 0.001, μ = 0.0001 and N = 1000; e α0 = 0.001, β = 0.0001, μ = 0.0001 and N = 100; f α0 = 0.01, β = 0.001, μ = 0.001 and N = 100; g α0 = 0.001, β = 0.0001, μ = 0.001 and N = 1000; h α0 = 0.01, β = 0.001, μ = 0.0001 and N = 1000.

We present the results more in depth in Section S5 in the supplementary material, but in conclusion, the model robustly produces dominance of opposing clusters of highly correlated beliefs across almost all parameter values, especially when learning from agents with shared beliefs dominates over unbiased and individual learning. Even though the agent-based simulations are not initialised with a head start for any beliefs, it produces mostly stronger associations between beliefs than does the equation-based model.

Conclusions

We have here illustrated how source filtering in cultural evolution can give rise to bipolarisation and form packages of beliefs that are associated only in that they function as signals for belonging to the same culturally emerged group. Our mathematical model fits in the realm of similarity-biased influence, though in an epistemic way rather than assuming and being driven by homophily. Agents are influenced by those whom they have reasons to trust epistemically, that is, those that do not possess beliefs inconsistent with their own, and more so if there is already an overlap in beliefs. We investigated the dynamics through equation-based modelling with up to two sets of opposite belief pairs, and through simulations for more beliefs pairs and to include random events.

As discussed in the sections on related models, similarity-biased influence typically generates consensus or, with some limited updating, a diversity, but not bipolarisation, of beliefs. There are exceptions, assuming negative updating, network topologies that cluster agents, or beliefs that are themselves structurally related in clusters (in virtue of their contents or by social construction). Our model contrasts from those models by assuming no repulsive influence, no inherent structural relations between beliefs (except for their opposites), nor do agents have internal representations of belief relations, and interactions are non-assorted. Instead, the model builds on a modelling framework for cultural systems in which agents filter information based on its consistency with previously acquired information. Such a filter can take aim at, for example, how new information coheres with current beliefs, or whether the source of the message, the sender, is reliable or trustworthy (Flache et al., 2017; Jansson et al., 2021). If beliefs are clustered in virtue of the relations between their contents, then the former type of filtering can regenerate a similar clustering of agents and their belief systems, while the latter type of filtering, as we have demonstrated here, can also result in agents clustering in sets of beliefs without the need for preexisting clusters of relations between the contents of those beliefs.

Our main result is that source filtering can lead to the emergence of strongly connected belief packages that are distributed over the population in clusters. Initially unrelated beliefs can come to correlate strongly and the two largest factions in the population will typically be polarised at the extremes, such that if one of the groups believes P, Q and R, then the other believes \(\overline{P}\), \(\overline{Q}\) and \(\overline{R}\). All beliefs thus become identity signals of group membership, in that someone who believes P is likely to believe also Q and R, and someone who has one opposite belief typically opposes also the other beliefs.

In the deterministic population-based model, this is a long transient phase in a slow convergence towards a completely factionalised state without belief correlations. Since interactions are non-assorted, beliefs eventually disperse in the population, such that they are uniformly distributed at equilibrium. However, this convergence is slow relative to how fast polarisation emerges. This seems to reflect common evolutionary trajectories in the real world. Many issues stop being polarised because the population comes to a consensus, especially if there is empirical evidence for one of the beliefs, for example, a heliocentric worldview. In other cases, beliefs disperse and dissolve belief packages, as in our models. Some examples are religious factions with strong divides that have loosened up and allowed for individualised cross-fertilised varieties, connections between being a proponent of specific democratic forms of governance (such as monarchy and republicanism) and religious beliefs, and convictions of capitalist versus communistic ideologies during the cold war that have softened and allow for a mix of capitalist and socialist policies. A recent example is the connection between advocating Covid restrictions early during the pandemic and political ideology, where the groups have eventually come to start converging (Dochow-Sondershaus, 2022).

In the stochastic agent-based model, however, polarisation with correlated beliefs is not only a transient phase, but it appears to be a persistent state, with no signs of decline over the simulated time intervals. In both models, results are fairly robust across a wide range of parameter values, assuming most of the belief acquisition takes place through social transmission between individuals with compatible sets of beliefs with some overlap. In exceptional cases with a large amount of general social learning combined very few innovations, that is, where individual learning is rare, variation is drowned out and populations sometimes converge on a small set of beliefs, leading to consensus. In almost all other cases investigated, there is at least some association of beliefs and bipolarisation. In most of these cases, these patterns are also strong. These cases coincide with the parameter values of interest here: strong bipolarisation with tightly connected beliefs emerges when similarity-biased learning is large compared to unbiased social learning and individual learning. This reflects the fact that bipolarisation is more likely to occur on topics about which individuals have little or no direct, first-hand access to evidence, and hence where social learning greatly outpaces individual belief formation, and where topics are too complex for individual evaluation, creating a need for choosing which sources to trust. This situation may obtain for example for foreign policy or scientific topics like the safety of vaccines or the severity of anthropogenic global warming.

We also suggested ways to operationalise empirical feedback by introducing an innovation bias for beliefs for which it is easier to find evidence or a loss of beliefs for which there is counterevidence. With such asymmetries, it is possible to also generate population outcomes where only one of the beliefs in a pair of opposites is indicative of other beliefs, while the other is not. This thus captures the phenomenon where there is not a strong divide between two equally large camps, but asymmetric polarisation, where mainstream ideas are commonplace irrespective of other beliefs, while fringe ideas become associated with particular belief packages. Believing in anthropogenic global warming may say little about people’s political leanings, but not believing in it does (e.g. Gregersen et al., 2020; McCright and Dunlap, 2011).

We have so far discussed the process of source filtering as taking place when the receiving individual itself sorts incoming information. There are, however, other instances of source filtering in cultural transmission. One is that senders might preferentially approach people with similar belief systems or communicate in a way that is most available to receivers with consistent sets of beliefs (Jansson et al., 2021). Another is that it is machine-mediated, through artificial intelligence and algorithms such as collaborative filtering (even when humans do not themselves actively engage in source filtering).

Taking collaborative filtering as an example, it is an automated process that is common in online environments such as social media and some news platforms, where an algorithm selectively presents information to a user based on the preferences and behaviours of other similar users. It assumes that if user A has similar preferences to user B, then what appeals to user B is likely to appeal to user A as well, so, based on this similarity, the system filters and recommends content that aligns with the user’s established ideas and preferences. The information that reaches the receiver has thus already been selected in a process that parallels source filtering. We have here seen how source filtering is a potent force in polarisation and the creation of mutually exclusive belief packages, forming identities. Present digital information technologies can potentially exacerbate this process by reinforcing source filtering. In our models, polarisation effects are most pronounced when individuals predominantly learn from others with overlapping beliefs, rather than from those with orthogonal views or through individual innovation. These dynamics may plausibly align with certain types of content on social media platforms that emphasise content sharing, where collaborative filtering tends to prioritise material already endorsed by similar users. In such settings, exposure to orthogonal perspectives is restricted by the recommendation system itself, while opportunities for genuine innovation can also be limited by the nature of the content, for example, in scientific domains. Under these conditions, collaborative filtering reinforces belief clusters in ways that resemble the processes captured in our models of source filtering. By contrast, there are recommender algorithms building on content-based filtering, where recommendations are derived from similarities in the attributes of the material itself. This process bears a closer resemblance to our operationalisation of content filtering in humans, where information is evaluated against prior beliefs regardless of its source. Collaborative filtering took the lead over content-based filtering on many platforms a couple of decades ago because of its effectiveness, but our results suggest it has societal side effects.

Data availability

There is no empirical data. All information about the equation-based models is included in the manuscript and supplementary material. Python code for the agent-based model and data from the simulations are available at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/XGSOJM.

Notes

We implemented the model as described in the original paper (Axelrod, 1997). Similar to that paper, simulations were run such that each agent had on average ten attempts at copying a neighbour (the number of events was ten times the lattice size). We ran 100 simulations for each set of parameters. When there were more than two traits, we computed the pairwise ϕ coefficients between all pairs of traits and took the average. The correlations decreased with the lattice size and the number of traits. For a lattice size of 50 ⋅ 50 patches, the average maximum correlations across runs was < 0.05 with two traits and 0.03 with three traits, while the average of the mean correlations and those halfway through the simulations was about 0.02. For a lattice size of 100 ⋅ 100 these measures were around 0.01.

Since αi, β and μ are all implemented as probabilities and α1 is always largest, setting α1 < 1 just results in rescaling. If, for example, α1 = 0.1, then dividing also α0, β and μ by ten produces identical results but on a ten times longer timescale.

References

Abelson, RP (1964) Mathematical models of the distribution of attitudes under controversy. In: Frederiksen N and Gulliksen H (eds.) Contributions to mathematical psychology, chap. 6. Holt, Rinehart & Winston, New York, New York, pp. 141–160

Allcott H, Boxell L, Conway J (2020) Polarization and public health: partisan differences in social distancing during the coronavirus pandemic. J Public Econ 191:104254

Axelrod R (1997) The dissemination of culture: a model with local convergence and global polarization. J Confl Resolut 41(2):203–226

Banisch S, Olbrich E (2018) Opinion polarization by learning from social feedback. J Math Sociol 43(2):76–103

Banisch S, Shamon H (2023) Biased processing and opinion polarization: experimental refinement of argument communicationtheory in the context of the energy debate. Sociol Methods Res 54:00491241231186658

Bellina A, Castellano C, Pineau P et al. (2023) The effect of collaborative-filtering based recommendation algorithms on opinion polarization. arXiv

Bonacich P, Lu P (2012) Introduction to mathematical sociology. Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey

Boyd R, Richerson PJ (19895) Culture and the evolutionary process. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, Illinois

Boyd R, Richerson PJ (2025) The origin and evolution of cultures. Oxford University Press, New York, New York

Bramson A, Grim P, Singer DJ (2017) Understanding polarization: meaning, measures, and model evaluation. Philos Sci 84(1):115–159

Brugidou M, Bouillet J (2023) A return to grace for nuclear power in European public opinion? Some elements of a rapid paradigm shift. Tech. Rep. 662, Foundation Robert Schumann

Buskell A, Enquist M, Jansson F (2019) A systems approach to cultural evolution. Palgrave Commun 5(131):1–15

Carlander A, Andersson U (2020) Oro, vaccinationsintention samt bedömningar av den svenska coronastrategin. Tech. rep., University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden

Castellano C, Fortunato S, Loreto V (2009) Statistical physics of social dynamics. Rev Mod Phys 81:591–646

Centola D, González-Avella JC, Eguíluz VM (2007) Homophily, cultural drift, and the co-evolution of cultural groups. J Confl Resolut 51(6):905–929

Deffuant G, Neau D, Amblard F (2000) Mixing beliefs among interacting agents. Adv Complex Syst 03(01n04):87–98

Dochow-Sondershaus S (2022) Ideological polarization during a pandemic: Tracking the alignment of attitudes toward COVID containment policies and left-right self-identification. Front Sociol 7:958672

Dorst K (2023) Rational polarization. Philos Rev 132(3):355–458

Efferson C, Lalive R, Cacault MP et al. (2016) The evolution of facultative conformity based on similarity. PLOS ONE 11(12):e0168551

Eriksson K, Vartanova I, Strimling P (2024) A cultural evolution theory for contemporary polarization trends in moral opinions. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11(1):1652

Festinger LA (1957) Theory of cognitive dissonance. Stanford University Press, Redwood City, California

Flache A, Mäs M, Feliciani T (2017) Models of social influence: towards the next frontiers. JASSS 20(4):2

Galesic M, Olsson H, Dalege J (2021) Integrating social and cognitive aspects of belief dynamics: towards a unifying framework. J R Soc Interface 18(176):20200857

Goldberg A, Stein SK (2018) Beyond social contagion: associative diffusion and the emergence of cultural variation. Am Sociol Rev 83(5):897–932

Gregersen T, Doran R, Böhm G et al. (2020) Political orientation moderates the relationship between climate change beliefs and worry about climate change. Front Psychol 11:1573

Hegselmann R, Krause U (2002) Opinion dynamics and bounded confidence: Models, analysis and simulation. JASSS 5(3):2

Hegselmann R, Krause U (2015) Opinion dynamics under the influence of radical groups, charismatic leaders, and other constant signals: a simple unifying model. Netw Heterog Media 10(3):477–509

Heider F (1958) The psychology of interpersonal relations. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., New York, New York

Henrich J (2004) Cultural group selection, coevolutionary processes and large-scale cooperation. J Econ Behav Organ 53(1):3–35

Henrich J (2016) The secret of our success: how culture is driving human evolution, domesticating our species, and making us smarter. Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey

Henrich J, Boyd R (1998) The evolution of conformist transmission and the emergence of between-group differences. Evol Hum Behav 19(4):215–241

Henrich N, Henrich J (2007) Why humans cooperate: a cultural and evolutionary explanation. Oxford University Press, New York

Henrich J, McElreath R (2003) The evolution of cultural evolution. Evolut Anthropol 12(3):123–135

Holmberg S, Hedberg P (2011) Party influence on nuclear power opinion in Sweden. Tech. Rep. 2011:5, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden

Isaksson Z, Gren S (2024) Political expectations and electoral responses to wind farm development in Sweden. Energy Policy 186:113984

Jansson F (2013) Pitfalls in spatial modelling of ethnocentrism: a simulation analysis of the model of hammond and axelrod. J Artif Soc Soc Simul 16(3):2

Jansson F (2015) What games support the evolution of an ingroup bias? J Theor Biol 373:100–110

Jansson F, Aguilar E, Acerbi A (2021) Modelling cultural systems and selective filters. Philos Trans R Soc B 376:20200045

Jansson F, Buskell A, Enquist M (2023) Cultural systems. In: Tehrani, J, Kendal, J and Kendal, R (eds.) Oxford handbook of cultural evolution. Oxford University Press, Oxford, United Kingdom, pp. C9S1–C9S17

Jansson F, Parkvall M, Strimling P (2015) Modeling the evolution of creoles. Lang Dyn Change 5(1):1–51

Jern A, Chang Km, Kemp C (2009) Bayesian belief polarization. In: Bengio, Y, Schuurmans, D, Lafferty, J et al. (eds.) Advances in neural information processing systems, vol. 22. p. 853–861

Jönsson E, Oscarsson H (2021) Den svenska coronastrategin. Tech. rep., University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden

Kahan DM (2016) The politically motivated reasoning paradigm, Part 1: what politically motivated reasoning is and how to measure it. In: Emerging trends in the social and behavioral sciences. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, pp. 1–16

Kahan DM (2017) Misconceptions, misinformation, and the logic of identity-protective cognition. Tech. Rep. 164, Cultural Cognition Project Working Paper Series. Yale Law School, Public Law Research Paper No. 605; Yale Law & Economics Research Paper No. 575

Kelly T (2008) Disagreement, dogmatism, and belief polarization. J Philos 105(10):611–633

Kerr J, Panagopoulos C, van der Linden S (2021) Political polarization on COVID-19 pandemic response in the United States. Personal Individ Differ 179:110892

Lord CG, Ross L, Lepper MR (1979) Biased assimilation and attitude polarization: the effects of prior theories on subsequently considered evidence. J Pers Soc Psychol 37:2098–2109

Macy MW, Kitts JA, Flache A et al. (2003) Polarization in dynamic networks: a hopfield model of emergent structure. In: Breiger, R, Carley, K and Pattison, P (eds.) Dynamic social network modeling and analysis: workshop summary and papers. The National Academies Press, Washington, D.C., pp. 162–173

Mahajan N, Wynn K (2012) Origins of “Us” versus “Them”: Prelinguistic infants prefer similar others. Cognition 124(2):227–233

Mark NP (2003) Culture and competition: Homophily and distancing explanations for cultural niches. Am Sociol Rev 68(3):319–345

Mäs M, Flache A (2013) Differentiation without distancing. Explaining bi-polarization of opinions without negative influence. PLOS ONE 8(11):e74516

McCright AM, Dunlap RE (2011) Cool dudes: the denial of climate change among conservative white males in the United States. Glob Environ Change 21(4):1163–1172

McElreath R, Boyd R, Richerson PJ (2003) Shared norms and the evolution of ethnic markers. Curr Anthropol 44(1):122–130

McPherson M, Smith-Lovin L, Cook JM (2001) Birds of a feather: homophily in social networks. Annu Rev Sociol 27(2001):415–444

Nguyen CT (2020) Echo chambers and epistemic bubbles. Episteme 17(2):141–161