Abstract

This article presents an overview of and introduction to philosophical stances often identified in information systems research. The philosophical stances are described regarding their ontology, epistemology and axiology across the philosophical paradigms of post-positivism, interpretivism, critical realism, pragmatism and critical theory. Through a case analysis from the interdisciplinary information systems field, the article illustrates and compares how each philosophical paradigm approaches the research process, highlighting the differences in underlying assumptions and methodologies. The article ends by warning against using the paradigms as templates for research, encouraging further ontological, epistemological and axiological discussions about what information systems research is and should be.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

While science broadly can be defined as the systematic quest for knowledge (Ponterotto, 2005), this pursuit gains its broader significance from its potential to contribute to a better world. There are conflicting views among social scientists as to how the social world is to be understood and how knowledge about it can be generated; that is, they have different ontological, epistemological and axiological assumptions (Guba, 1989). Researchers are influenced by these philosophical assumptions, shaping how they are systematic about it through the formulation of research questions, choice of methodologies and interpretation of findings (Crotty, 1998; Saunders et al., 2009).

In recent decades, the information systems (IS) field has witnessed a philosophical broadening, with researchers drawing upon various philosophical positions (Tarafdar et al., 2025). However, the philosophical literature is full of ‘isms’ and can be notoriously difficult to comprehend as it sometimes is inconsistent and confusing, using a great variety of terms for similar phenomena (synonymy) as well as using the same term while referring to different phenomena (homonymy) (Crotty, 1998). These conceptual inconsistencies also appear in IS literature, leading to unclear applications and misunderstandings of philosophical positions.

Although many papers have been written discussing philosophical aspects of IS research, this article takes a different approach: it presents a philosophical case analysis. Specifically, it offers a coherent and accessible overview of philosophical stances as they are understood in the IS field and then applies these paradigms to analyse a single illustrative case that highlights the interplay between technical and social systems. This comparative case analysis demonstrates how researchers grounded in different paradigms would approach the same research problem differently, highlighting the practical implications of philosophical commitments, including their strengths and weaknesses. This is an ambitious task to accomplish in one article, and as a result, many important questions must be left unexplored. Nevertheless, the article aims to serve as a guide for researchers not so familiar with IS philosophy, in particular Ph.D. students. As the IS field resembles developments within other research fields, such as management and organisation, this article may be useful for students and junior researchers in these fields as well.

The article is organised as follows. First, a brief overview of the modern philosophy of science is introduced before ontological, epistemological and axiological positions in the social sciences are presented. Thereafter, five philosophical paradigms, often applied in IS research, are presented, followed by a detailed philosophical case analysis from the IS field through the lens of each paradigm. Afterwards, the paradigms are compared, before the article concludes by challenging conventional paradigm template thinking in IS, encouraging further ontological, epistemological and axiological discussions of IS research.

A brief introduction to the philosophy of science

Philosophy is understanding the truth about oneself, the world, and how we relate to each other. The philosophy of science is a subfield, focusing on what scientific knowledge is, its development and what we can expect from it (Saunders et al., 2009). Whereas science belongs to the modern era, coined modernism, philosophers have for a long time struggled with how knowledge claims can be justified. Plato and Aristotle, rationalists such as Descartes, Spinoza and Leibniz, empiricists such as Bacon, Locke, and Hume and the more moderate Kant, all discussed whether knowledge mostly arises from intellectual reasoning (deduction, rationalism) or through our senses by observing the world (induction, empiricism). Whereas rationalism claims that natural logical relationships in the world can be discovered through reasoning, empiricism holds that what we see and experience is real.

In the modern philosophy of science, Kant put forth that we should avoid making inferences about some underlying reality. Comte argued further that theorising about unobservable underlying causal mechanisms could lead to mistaken preconceptions to favour dominating theories. He recommended basing science on observation only; an approach he termed positivism. Through observations, predictions about future observations could be made. In logical positivism, the Vienna Circle followed Comte but held that knowledge claims must be verifiable. Other claims, many being in prominent areas such as religion, ethics and metaphysics, were dismissed as meaningless. Popper (1959) criticised logical positivism and rejected empiricism, introducing what he termed ‘critical rationalism’. He put forth that scientific claims could only be falsified and never verified—the latter a practice he characterised as ‘the problem of induction’. Popper observed that scientific theories were seldom refuted but instead defended by proponents to the point where conflicting research was ignored.

This problem was taken up by Lakatos. He said that certain ‘research programs’ had their central hypotheses protected with ‘rescue hypotheses’ developed to address contrary evidence. Building upon Lakatos, Kuhn (1970) argued that knowledge production is not a linear process, but rather goes through three cyclical stages: prescience, normal science and revolutionary science. In prescience, there is no dominating paradigm causing all facts related to a certain phenomenon to be equally relevant. After a while, a need for more precise work occurs as researchers believe they come closer to certain knowledge about a phenomenon, entering normal science. Here, researchers dedicate themselves to the existing dominating paradigm with much confidence, often neglecting results that contradict the dominating views (Kuhn, 1970). When conflicting research piles up, a crisis eventually occurs, entering the stage of revolutionary science (a new paradigm) (Kuhn, 1970). When a new paradigm has been established, adherents of the old paradigm find it hard to provide support for work within that paradigm. Feyerabend (1975) criticised both logical positivism and Popper’s critical rationalism. He rejected the attempt to distinguish between scientific and non-scientific knowledge (the demarcation criterion) since no clear definition of science and assessment criteria exist.

How can we then create reliable knowledge, the very purpose of science? In both the natural and the social sciences, it is generally accepted that claims should be assessed based on principles such as commonality and repeatability. However, the way these principles are operationalized can differ across domains; for example, social sciences often face additional challenges due to the reflexivity and context-dependence of human subjects. Therefore, mystical, clairvoyant, religious and telepathic experiences are not considered scientific. This does not mean they are insignificant; however, these experiences cannot be replicated in research studies. For other experiences, the answer may be that the assessment of reliable knowledge depends on philosophical assumptions—as demonstrated by the various reviewer comments we receive. This is why researchers have different approaches to justifying their research. For example, some researchers may spend several pages in a research article explaining their inductive, interpretive research design to avoid criticism from reviewers. This is a well-known problem in several disciplines, including IS, although alternative philosophical approaches are better acknowledged now.

Ontological, epistemological and axiological assumptions in social sciences

Ontology, epistemology and axiology are used to describe how researchers view and study the social world. The social world often differs from that of the natural world in its reflexivity, context-dependence and the role of human interpretation, influencing how social science researchers describe reality, and what and how we can learn from it.

Ontology

Ontology is concerned with how we view the existence (‘the being’) of empirical phenomena; whether they are created and reproduced without human interference, or merely exist as social constructions (Orlikowski and Baroudi, 1991). For instance, are gender differences in programming interest due to inherent disparities or societal influences? Feminists argue for social construction, where cultural structures (e.g. patriarchy) shape female involvement. Similarly, ontological assumptions influence whether technologies are seen as purely technical systems—material and algorithmic entities with objective properties—or as social systems, enacted and reproduced through human practices. The ontological debate lies between modernist realism and postmodernist relativism. Realists believe in a single reality, while relativists argue for multiple subjective realities. Realists possess different ontological understandings. Whereas naive realists seek to understand reality using appropriate methods, critical realists recognise that social structures shape how humans experience reality, and transcendental realists acknowledge an underlying reality beyond human perception that cannot be understood fully (Guba and Lincoln, 1994; Moon and Blackman, 2014). Relativists also differ, with pure relativists claiming that everyone creates their perception of reality in their mind (Crotty, 1998), and bounded relativists recognising shared realities within cultural groups (Moon and Blackman, 2014).

Epistemology

Epistemology explores how we acquire certain knowledge about the social world, that is, how we as researchers can design and conduct our research studies to make valid claims (Kuhn, 1970; Orlikowski and Baroudi, 1991; Popper, 1959). One important question is whether social phenomena can be observed directly or if they exist without our awareness of them. Naïve realists believe in direct observation and causal relationships, while transcendental realists look for underlying structures beyond direct observation. Relativists focus on understanding individual interpretations of reality (Marsh and Furlong, 2002). Epistemological perspectives can be categorised as objectivism, constructionism and subjectivism. These epistemological stances also influence how we study technical and social systems. Objectivists seek universal truths about objects, intrinsically reflecting reality and their true meaning, through empirical research. Any interests, values, or interpretations of the researcher will not influence this knowledge (Pratt, 1998). Objectivist approaches often focus on measurable properties of technical artefacts, treating technology as an external object of enquiry. Constructionists emphasise that knowledge is constructed through engagement and interpretation (Crotty, 1998). Positing the existence of unobservable structures provides us with an ‘inference to the best explanation’. Subjectivists recognise knowledge to be dependent upon how researchers can interpret meanings and values imposed by people (Crotty, 1998; Pratt, 1998). The aim is to critically examine claims and approach the closest approximation of truth. Constructionist and subjectivist perspectives will emphasise how knowledge about technology emerges through human interpretation, interaction and social practice—highlighting the intertwined co-construction of technical and social realities.

Axiology

Axiology concerns the values and ethics in research (Hassan et al., 2018). For an objectivist, stating and involving any values would make research less credible. Instead, it is possible to produce true answers (‘facts’) reflecting how the world is. They consider any misuse of science a societal issue, not a result of value-laden research (Okasha, 2016). Subjectivists argue that researchers and subjects have inherent values, influencing research choices. By making research choices, researchers say that certain problems, paradigms, theoretical frameworks, data collection techniques, contexts and presentation formats are more important than others. Acknowledging these values increases research credibility (Lincoln and Guba, 2000). Axiology also shapes how scholars approach the distinction between technical and social systems. Treating systems as purely technical may conceal the normative assumptions built into design choices—such as efficiency, control, or neutrality—whereas focusing on social systems foregrounds how values and ethics are embedded in organisational practices, user interactions and governance structures. Axiology is less discussed compared to ontology and epistemology in IS discourses, with ethics receiving more attention than aesthetics (Hassan et al., 2018).

Philosophical paradigms in IS research

Philosophical paradigms are elaborate and heuristic views of the world (Guba, 1989). They take into account ontology, epistemology and axiology, having implications for how research is conducted and presented (Guba and Lincoln, 1994; Ponterotto, 2005). Paradigms are sometimes termed stances, perspectives, worldviews, positions and orientations. Although elaborate, paradigms may not have organised views in every aspect, such as pragmatism, which has a more agnostic approach to ontology (Mingers, 2004). Each paradigm is characterised by pluralism, reflecting the complex evolution of philosophy with a wide variety of contributions from philosophers throughout history (Crotty, 1998), and thus, it is not possible to align paradigms according to a continuum. It is common for researchers to identify themselves with elements from different paradigms and change epistemological and ontological positions over time (Knutsen and Moses, 2012). The link between philosophical stance and empirical practice is often indirect: researchers may adopt methodological tools that do not fully align with their stated paradigm, or combine elements from multiple paradigms in pragmatic ways. Table 1 lists historically salient paradigms in IS research and presents their main characteristics as often described in the IS literature (e.g. Goldkuhl, 2012; Hirschheim and Klein, 2012; Mingers, 2004; Munkvold and Bygstad, 2016; Orlikowski and Baroudi, 1991; Siponen and Tsohou, 2018), while acknowledging that alternative interpretations exist. An illustrative case from the IS field is introduced to demonstrate the differences in the paradigms.

Illustrative case

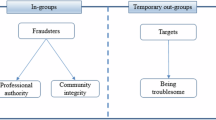

This article discusses philosophical influences through Madsen’s (2016) case study of a mandatory Danish digital service for paying benefits to single parents. Contrary to expectations that citizens would solely use digital services once deployed, Madsen (2016) observed that many single parents also contacted public authorities via phone. Using various research methods, including observations (co-listening to call centre interactions), statistical data analysis (call and website visit statistics), focus groups (five focus groups with a total of 28 single parents), and interviews (nine single parents from the focus groups were interviewed individually), he explored the processes through which these citizens incorporated, negotiated and made the digital channels their own in their daily routines. Reasons included problem complexity, perception of issues, a lack of administrative literacy and a need for information not readily available on the website. Ultimately, the thesis aimed to identify ways to improve e-government services, reduce reliance on traditional channels and better align digital channels with users’ needs and practices. Madsen (2016) identifies himself as a social constructionist.

Post-positivism

While positivism has been widely critiqued and even declared ‘dead’ in some philosophical accounts, it continues to shape scientific and social scientific thinking—often implicitly—under labels such as post-positivism (Bentz and Shapiro, 1998). Post-positivism is a reaction to positivism and has dominated IS research for many years (Hirschheim and Klein, 2012). However, its dominance has been challenged considerably during the last three decades (cf. Hirschheim and Klein, 2012). Whereas the term broadly may be defined as those approaches historically succeeding positivism (Fox, 2008; Petter and Gallivan, 2004), it is presented here as a realist paradigm of its own (Given, 2008), reflecting ideas of critical rationalism. The ontology of post-positivism is critical realist: it assumes that a reality exists independently of human perception, but our understanding of it is inevitably partial, theory-laden and subject to revision. This means reality can be studied and approximated yet never known with absolute certainty (Guba and Lincoln, 1994; Phillips and Burbules, 2000). This assumption underpins much empirical IS research seeking to uncover causal regularities—for instance, studies testing the technology acceptance model across contexts (Davis, 1989) or refining constructs such as perceived usefulness and ease of use in organisational settings (Venkatesh and Davis, 2000). However, IS scholars have used the term with reference to several understandings: it has been understood as the interpretive and critical perspectives (Myers et al., 2004), more broadly as a ‘movement’ reacting to positivism (Hirschheim, 1985); a reference to the successors of positivism (Petter and Gallivan, 2004), and a distinct position (Poole, 2009).

Post-positivism believes that the social world is analogous to the natural world, and thus, can be studied using research methods similar to those of the natural sciences (Phillips and Burbules, 2000). In the context of our illustrative case, this means that citizens’ repeated calls about a self-service benefit application could be approached in much the same way as recurring phenomena in nature: through systematic observation, measurement and explanation. Comparable logic is seen in IS diffusion research, such as DeLone and McLean’s (2003) IS success model, which treats information quality, system quality and user satisfaction as measurable variables whose interrelations can be empirically tested. However, post-positivism does not recapitulate positivism in important respects. Whereas post-positivism, positioned in a modernist realist ontology (Bhaskar, 2013), believes in one reality, it also acknowledges that research is a joint effort among researchers continuously evolving as time passes (Petter and Gallivan, 2004). Thus, a post-positivist works together with other researchers, though intersubjectively and through these efforts achieves a kind of independence that, ‘over time accretes a ‘common-sense’ reality with layers of institutionalisation, tradition and socialisation’ (Fox, 2008, p. 663). As stable relationships among social phenomena are revealed, people’s understanding of the world becomes increasingly limited and according to ‘the received view’ (Poole, 2009).

In our case, this would involve different research teams gradually converging on shared understandings of why citizens persist in calling despite having access to a digital channel. Madsen (2016) acknowledges this limitation in his research. His methodological approach combined observation, focus groups, interviews and supplementary quantitative data, providing a multifaceted and in-depth understanding of citizen–state interactions within that setting. The observations and interviews captured highly situated dynamics, revealing how local routines and informal practices influenced digital service use. Similarly, focus groups reflected the shared understandings and expectations of participants within that particular community, while the supplementary quantitative data offered descriptive support that remained bounded by the same context. While the findings are contextually rich for a specific context, they are shaped by the specific institutional, cultural and service-related context in which the study took place and may therefore not represent behaviours of wider groups of citizens, especially considering the relatively small sample size and the research’s focus on a specific service. As such, the methodological strength of Madsen’s study—its deep contextual engagement—also constitutes a limitation in terms of transferability that does not align well with a post-positivistic stance.

The synthesis of knowledge makes it possible to study social phenomena, describe trends and identify interrelationships between them (Creswell and Creswell, 2017; Guba and Lincoln, 1994). From a post-positivist stance, trend identification and prediction aim to approximate real patterns that exist independently of our observations, while recognising that such forecasts are inherently probabilistic and shaped by the theoretical and contextual lenses through which data are interpreted (Guba and Lincoln, 1994). Large-scale post-positivist IS studies, such as Venkatesh et al.’s (2003) unified theory of acceptance and use of technology, exemplify this aim by modelling user behaviour across multiple contexts to identify stable predictors of system adoption. In the illustrative example, multiple datasets from the Danish self-service case—such as call logs, system usage records and demographic data—could be triangulated to reveal stable patterns in e-government acceptance behaviour. Even though human agency is unpredictable, the sum of human behaviour converges toward a description of the social world that can be accepted (Phillips and Burbules, 2000). Thus, society is not created by individuals, even though it is reproduced and transformed by them (Given, 2008). For example, patriarchy as a structure is an arrangement in which human agency is conditioned. Where it exists, individuals must work within the boundaries of this structure. Observations of individual experiences will thus amount to an independent social reality that can be studied objectively (Crotty, 1998). In our case, this suggests that the behaviour of benefit applicants is shaped not just by their own decisions but by structural features of the welfare system and the service design.

Acknowledging the human role in the construction of knowledge, the post-positivist hopes ‘by continual efforts towards methodological rigour, triangulation from various data sources and meticulous analysis of data that an approximation to truth can be derived, and generalised’ (Fox, 2008, p. 663). As such, what motivates a post-positivist is that rigorous research, theory-building and testing, as well as the accumulation of studies over time, will lead to encompassing knowledge about social phenomena (Fox, 2008). For the Danish case, such rigour might involve combining large-scale survey data on digital service perceptions with longitudinal studies of actual system use, gradually refining theories about what drives citizens to bypass the online system. Instead of verifying a proposition, it promotes Popper’s falsification principle (Crotty, 1998), which in this case might mean systematically testing—and potentially rejecting—different explanations for why calls continue. This principle has guided numerous IS studies that iteratively refine theoretical models, such as repeated empirical testing of the IS success model (DeLone and McLean, 2003) or the refinement of trust constructs in online commerce research (Gefen et al., 2003). Within these efforts, post-positivists would not accept value-laden researcher assumptions (Guba and Lincoln, 1994) but acknowledge that findings may be influenced by the viewpoints and values of our informants (Cecez-Kecmanovic, 2005; Maxwell, 2012).

The previous stronghold of post-positivism in IS created expectations that IS research should identify relationships between variables, be generalisable and use statistical or quantitative methods (Orlikowski and Baroudi, 1991). Post-positivist IS research has been conducted within three main domains: (1) planning, development, diffusion and implementation of IS within and across organisations, (2) operations and management of information and communications technology (ICT) infrastructure, information resources and IS structure and (3) effects of IS on individuals, organisations and society (Cecez-Kecmanovic, 2005). It is nomothetic, where theories consisting of (causal) relationships between phenomena are expressed and tested empirically (Neuman, 2010). For example, researchers could link theoretical constructs such as performance expectancy, perceived ease of use, or prior digital literacy to ICT acceptance to predict call frequency in the Danish benefit case, iteratively testing and refining hypotheses until stable, generalisable patterns emerge.

For example, researchers can predict the likelihood of ICT acceptance with increased performance and efficiency expectancy through UTAUT. Through numerous iterations of hypothesis testing, potential falsification, or refinement, causal statements are developed into more accurate statements about IS phenomena. The more studies that are not able to falsify a theory using empirical data, the stronger the theory is perceived to be (Popper, 1959). Generalisability is important in post-positivist IS research, assuming that the theory will be able to predict phenomena outside the empirical context in which the theory was initially tested (Yin, 2014). However, this assumption must be tested before claiming generalisability. When several studies on similar self-service cases yield comparable results, a post-positivist would seek to develop theories explaining why citizens keep calling, even when a digital alternative exists. While such theories cannot claim universal laws, they can suggest regularities that help policymakers design more effective services (Phillips and Burbules, 2000).

The post-positivist approach has been criticised since it tends to oversimplify complex, socio-technical systems, potentially overlooking the characteristics of people embedded in these systems (Hepworth et al., 2014). ICT may be used by a variety of cultures, organisations and individuals, and the emphasis on generalisation in post-positivism may fail to account for the unique characteristics of these implementations. In our case, factors such as delayed benefit payments, the need to explain individual circumstances, or to negotiate with a caseworker could strongly influence citizens’ acceptance of the service—effects that might be lost in large-N studies. Comparable critiques have been raised in IS by, for example, Walsham (1995), who argued that purely post-positivist models may obscure meaning and context in favour of statistical regularities for directly measurable phenomena. This highlights the value-ladenness of research: choices about what counts as observable, measurable, or generalisable are themselves influenced by assumptions about the nature of reality, knowledge and acceptable evidence. As such, while post-positivism provides a framework for systematically building and testing theories about e-government acceptance, it risks underplaying the very contextual and individual nuances that the Danish case brings to light.

Interpretivism

Interpretive research is postmodern and anti-realist, rejecting that the social world exists independently of our knowledge of it (Marsh and Furlong, 2002). On the contrary, it is produced and reproduced through interactions with humans (Orlikowski and Baroudi, 1991). To understand the social world, we need to ‘understand phenomena through accessing the meaning that participants assign to them’ (Orlikowski and Baroudi, 1991, p. 5). To interpretivists, findings are not facts in the generally understood way, but rather information influenced by the values and beliefs of the informants (Lincoln and Guba, 1985; Schwandt, 1994). Interpretivists do not judge informants’ values, although they acknowledge that values are culturally and socially situated. This emphasis on situated meaning draws on hermeneutic philosophy, which holds that understanding emerges from a dialogue between the researcher’s preconceptions and the participants’ accounts—a process often described as the ‘hermeneutic circle’ (Gadamer, 1975). In this view, meaning is not ‘discovered’ as an objective fact, but co-constructed through an iterative process of engagement with the phenomenon. This has been illustrated empirically in Benjamin et al. (2022), who studied machine learning interpretability using interpretive methods to reveal stakeholders’ situated sense-making. Interpretivists can be seen as passionate participants whose role is to facilitate different views (Cecez-Kecmanovic, 2005; Heron, 1996).

Whereas causal relationships are the goal of positivist research, identifying meaning, as the subjects within discourses or traditions see it, is the aim of interpretivist research (Munkvold and Bygstad, 2016). Interpretivist theory provides detailed descriptions of the meanings, values and norms individuals and groups attribute to their experiences (Cecez-Kecmanovic, 2005; Geertz, 1973). Since interpretivist research is idiographic, it does not specify universal laws aimed for generalisation across different contexts but rather seeks to gradually inform the phenomenon under scrutiny with much detail, making it possible for readers outside the context to understand the social reality described in the interpretive study. This aligns with the relativist ontology of interpretivism, which assumes multiple, context-bound realities (Lincoln and Guba, 1985). In our case, this might mean producing rich accounts of how citizens experience the benefit of self-service applications, including frustrations, misunderstandings and workarounds, so that readers unfamiliar with the Danish welfare context can still grasp the lived reality. Similar thick-description methods have been employed in Avgerou (2000), who explored how IT was interpreted differently across organisational contexts in Greece and the UK. By doing so, interpretivists argue that they also may inform other research settings (Munkvold and Bygstad, 2016) since the validity of knowledge is not dependent on statistical representability, but on ‘the plausibility and cogency of the logical reasoning used in describing the results from the cases, and in drawing conclusions from them’ (Walsham, 1993, p. 15).

Interpretivists believe findings can be generalised to theoretical concepts, often termed ‘generalisation to the phenomenon’ (Klein and Myers, 1999; Yin, 2014). The lack of causality does not mean that regularities cannot be observed related to the studied phenomena, but these regularities are attributed to shared norms and interests of humans within certain social settings (Munkvold and Bygstad, 2016), and which may change over time (Berger and Luckmann, 1967). In the Danish case, for example, some calling behaviour might be linked to a shared local belief that ‘important’ benefit requests require personal contact—a norm that could shift over time with trust in the system. Interpretive studies such as Orlikowski’s (1993) of CASE tool implementation have shown how shared norms and interpretations shaped technology adoption over time. Thus, interpretivist theories are generalisable to a specific context. An IS theory of technology acceptance could specify how the users experienced a newly implemented system related to, for example, any involvement in the design and implementation process, the communication of management, and power struggles in an organisation. An interpretivist study could therefore explain not only that citizens call, but also why the act of calling holds meaning for them—perhaps as reassurance, protest, or habit.

In the field of IS research, the interpretivist approach gained prominence in the late 1980s and early 1990s as researchers began to recognise the limitations of post-positivist approaches. Even though interpretivism was considered somewhat controversial, there were not many written voices arguing against it. According to Walsham (1995), this may be because post-positivist work represented the dominant, inherited paradigm, which did not require much justification to get published in the journals at that time. Whereas our premier journal, MIS Quarterly, seemed not to accept other than post-positivist research at the end of the 1980s, the tone was different in an editorial in 1993. During these years, an interpretivist IS school emerged, investigating issues within areas such as systems design, organisational intervention and management of IS and social implications of IS. Applied to our case, this shift could mean more research into how digital service design intersects with citizen identity, autonomy and trust in government—rather than focusing solely on system efficiency metrics. Since then, IS research has increasingly accepted research based on an interpretivist lens, expanding the areas researched, the journals wherein the research has been published and the methodologies applied to solve IS problems (Walsham, 1995).

While early IS research tended to view IS largely as technical systems, interpretivist researchers see IS as social systems, although technically realised. They should be understood in terms of how they are embedded in organisational and societal contexts, and how they influence and are influenced by these contexts (Cecez-Kecmanovic, 2005). IS research has broadly investigated how users understand IS and their implications for work and private life. In the benefit application case, this could mean examining how citizens’ prior dealings with government shape their interpretations of the system’s messages, or how community networks influence the decision to call rather than self-serve. This perspective has been applied in studies such as Avgerou and McGrath (2007), where interpretive methods revealed how local and organisational contexts shaped perceptions of ICT in development projects. The result is often that the meaning of IS is a result of alternating interpretations and reinterpretations. These interpretations are culturally, socially and historically conditioned, and the task of the interpretivist is to make sense of all the diverse individual accounts of experiences based on the context in which they are situated. For example, a researcher might capture how one citizen frames the application as empowering, while another sees it as alienating—both interpretations being valid within their own contexts. Methodologically, IS interpretivists make use of methods such as interviews, ethnography, and discourse analysis that can capture how the research subjects interpret their context. Hermeneutic approaches in IS research often treat interview transcripts, system documentation and even user interactions as ‘texts’ to be interpreted. Analysis proceeds iteratively, with the researcher’s evolving understanding influencing how further data is interpreted, in line with the hermeneutic tradition. The findings are ‘findings as interpretations’ instead of ‘findings as facts’. Research is validated based on how well the process is laid out, that is, the trustworthiness of the research design (Cecez-Kecmanovic, 2005). Interpretivists believe that the subjective meanings of research subjects have supremacy over a theory ‘imposed’ on them.

Interpretivists adhering to a relativist ontology and subjectivist epistemology would assume that e-government acceptance could be explained by multiple factors such as geographical and cultural differences, gender, age, feelings, values, interests, social norms and experience (Cecez-Kecmanovic, 2005; Marsh and Furlong, 2002). Contrary to post-positivists, they are open to answers showing that e-government acceptance is heavily influenced by contextual factors and nearly impossible to predict. Thus, instead of seeking predictive models, they would aim to narratively reconstruct the ‘story’ of citizens’ interactions with the system—from first encountering the online forms to deciding to make a phone call. To provide answers to why citizens keep calling, they would lay out the context in much detail, identify those who call, their personal preferences and characteristics, what type of technology they own, their relationship to technology and the political and societal context in which the e-government initiative is made. Rather than trying to identify common characteristics of the citizens and the system, interpretivists will embrace the complexity of the data (Moon and Blackman, 2014).

In line with this philosophical stance, Madsen (2016) positions himself close to an understanding of reality as socially constructed. The aim is not to produce universally generalisable explanations but to develop thick descriptions that capture how meaning is created and negotiated between citizens, frontline public service workers and technological systems in specific settings. This involves seeing citizens’ behaviours not merely as responses to system design or policy incentives but as interpretive acts shaped by prior experiences, expectations and the institutional environment. The researcher becomes part of the meaning-making process, seeking to understand the world from the participants’ point of view. This is reflected in Madsen’s methodological design, where observations, interviews and focus groups are used not to test predefined hypotheses, but to explore how individuals make sense of digital encounters and how their interactions reveal underlying assumptions about technology, governance, and service delivery. The IS study by Orlikowski (1993) is comparable, where fieldwork is used to reveal how organisational contexts shaped technology use.

Interpretivism has been criticised. For a post-positivist, interpretivism does not offer anything else than subjective opinions about the world, and thus, cannot be considered ‘science’. As such, its knowledge claims are founded on premises that cannot be validated. The opinions of one person are as good as the opinions of another, and there is no technique to decide the superiority of one interpretation over another. Thus, it struggles with issues of generalisability and usefulness. In the Danish case, this criticism might surface if one researcher’s interpretation of ‘why citizens call’ differs from another’s—without a clear mechanism for deciding which is more accurate. It is difficult for interpretivists to address this criticism since they fundamentally disagree on what science is.

Critical realism

Critical realism is a paradigm assuming a realist ontology and a constructionist epistemology. It was developed by Bhaskar (2013) as a response to the criticism of (post-)positivism and empiricism, aiming to reestablish a realist ontology while acknowledging that knowledge is socially constructed and contextually dependent (Mingers, 2004). Critical realists give priority to ontology; the world exists as it is, regardless of human experience.

Ontologically, critical realism distinguishes between the real, actual and empirical domains. The real domain encompasses the entirety of reality, including mechanisms, structures, events and experiences (Mingers, 2004). Some of these structures give rise to causal regularities known as generative mechanisms (Bhaskar, 2013; Danermark et al., 2019; Mingers, 2004). Identifying or imagining plausible generative mechanisms is central to explaining patterns in events, rather than simply describing them (Sayer, 1999). For example, Volkoff et al. (2007) empirically explored generative mechanisms in organisational adoption of information systems, showing how IT-enabled routines shape outcomes. The actual domain is a subset of the real comprising events that occur because of the enactment and interaction of the mechanisms from the real domain (Wynn and Williams, 2020). Critical realism asserts that there are enduring entities in the world, observable or not, continuously generating a flux of events (Mingers, 2004). These entities may or may not manifest themselves depending on various generative mechanisms and conditions (Mingers, 2004).

While natural sciences often find consistent causal relationships due to fixed mechanisms, IS faces more variability and instability in outcomes due to fluctuating internal and external conditions (Wynn and Williams, 2020). However, regularities can still be identified within limited contexts in IS, serving as a starting point for critical realism studies (Wynn and Williams, 2020). Whereas post-positivism has adopted the Humean conception of causality, in which knowledge entirely arises from experience, critical realism argues that empirical observations are «neither a sufficient nor a necessary condition for a causal law» (Tsang, 2014, p. 176). This is referred to as the ‘epistemic fallacy’ by Bhaskar (2008), who asserts that having a causal effect on the world implies existence regardless of perceptibility (Mingers, 2004).

While critical realism maintains a realist ontological stance (transcendental realism), it acknowledges that knowledge is historically and contextually dependent, accumulated through human work, drawing upon existing theories and results, reflecting constructionist epistemology (Archer et al., 2013; Mingers, 2004). Epistemic relativity is recognised, but critical realism distinguishes it from judgmental relativity and does not consider all knowledge claims to be equally valid (Mingers, 2004). Critical realists believe that there are rational grounds for choosing between different knowledge claims.

In terms of research methodology, critical realism goes beyond merely studying observed events and aims to understand the underlying mechanisms and conditions that produce those events (Bygstad et al., 2016; Easton, 2010). Researchers use abductive reasoning, moving from observations to theorising about underlying structures and mechanisms (Wynn and Williams, 2020). The mechanisms can either be discovered by the researcher (retroduction) or applied based on their identification in another study (retrodiction) (Wynn and Williams, 2020). An empirical example is Bygstad (2010), who used critical realist case studies to uncover mechanisms influencing digital infrastructure evolution. Critical realism is tolerant of multiple methods, although qualitative methods are often favoured for capturing and developing causal explanations of underlying mechanisms (Sayer, 1999; Wynn and Williams, 2020). Critical realism treats knowledge as consisting of probable facts or tendencies rather than absolute laws (Bhaskar, 2013; Sayer, 1999). The aim is understanding rather than prediction, although explanatory frameworks can inform practice (Danermark et al., 2019).

In terms of axiology, critical realism values emancipation and freedom as the ends of research (Bhaskar and Hartwig, 2016). As such, there is a link between the ‘critical’ component of critical realism and critical theory. Research is not separated from values; rather, values guide topic selection and interpretation, particularly where social injustice or structural oppression is present (Sayer, 1999). It addresses the structure-agency debate by recognising that humans can be constrained by social structures and generative mechanisms, providing insights into oppression and informing corrective actions (Wynn and Williams, 2012).

Within the IS field, critical realism has been increasingly adopted during the last decade (Bygstad et al., 2016; Rieder et al., 2021). From its early introduction (Mingers, 2004), more empirical research has been conducted, providing concrete examples of the new insights critical realism offers (e.g. Bygstad, 2010; Smith, 2010; Volkoff et al., 2007). As a result, methodological guidelines have been developed for critical realist case studies (Wynn and Williams, 2012) and the identification of mechanisms through affordances (e.g. Bygstad et al., 2016; Volkoff and Strong, 2013). Empirical studies have mainly identified generative mechanisms. For example, Henfridsson and Bygstad (2013) identified three generative mechanisms explaining how digital infrastructures evolve, Williams and Karahanna (2013) identified two generative mechanisms of coordination processes, and Rieder et al. (2021) identified seven generative mechanisms explaining individual wearable use and its outcomes.

In the illustrative case, following repeated observations of people calling despite the availability of self-service channels, a critical realist would acknowledge that some underlying generative mechanisms and structures cause these events. These mechanisms can reside in both the technical system (e.g. legacy system affordances, limitations of the digital channel) and the social system (e.g. institutional routines, caseworker practices, citizen trust and expectations). The researcher would then attempt to identify such mechanisms—possibly including institutional routines, legacy system affordances, or citizen trust dynamics—and subsequently seek the best possible explanations for why people keep calling. Rather than assuming that hidden causal mechanisms exist independently of human interpretation, Madsen (2016) emphasises meaning, context and subjectivity.

Instead of searching for abstract causal structures, the focus is on how actors themselves understand and construct the situation in which they act. The persistent use of phone calls is therefore not explained by reference to an underlying mechanism but understood as a socially meaningful practice embedded in specific organisational and societal contexts. This highlights a key distinction: technical systems provide stable, observable mechanisms, whereas social systems produce contingent, context-dependent patterns of behaviour shaped by interpretation and interaction. From this standpoint, what matters is not uncovering a ‘real’ cause behind behaviour but exploring how different participants make sense of available communication channels, and how these interpretations shape their actions. This reflects a fundamental ontological and epistemological divergence from critical realism: Madsen’s (2016) methodological approach is directed at capturing the multiplicity of meanings that citizens and service providers ascribe to digital interaction, rather than isolating stable causal relationships.

Critical realism, as a fusion of post-positivist and interpretivist perspectives, accepts the existence of an objective reality, yet concedes that our comprehension of this reality is coloured by our personal experiences. In the context of the case, this means accepting that there is a real set of mechanisms shaping citizen behaviour, while also acknowledging that any understanding of these mechanisms is mediated by the researcher’s and participants’ perspectives. In practice, this means that technical systems have real effects on behaviour, but social systems mediate and modulate these effects, creating behavioural patterns that cannot be fully predicted from the technical system alone. Balancing these divergent perspectives can be challenging, and researchers may face epistemological difficulties operationalizing this paradigm. Whereas critical realism aims at understanding underlying causal mechanisms, critics have argued that it is not possible to know these mechanisms with certainty. Given its emphasis on the concealed structures that underpin observable phenomena, an empirical test and validation of its claims becomes difficult. In our case, while certain mechanisms such as ‘habitual reliance on telephone contact’ could be inferred, proving them definitively would remain challenging. Thus, critical realism’s emphasis on uncovering hidden mechanisms may lead to a kind of determinism that neglects the intricacies and unpredictability inherent in social-technical phenomena.

Pragmatism

Pragmatism is a paradigm that prioritises the practical impact and problem-solving aspects of research (Bernstein, 2010; Goldkuhl, 2012). As Dewey (1938) argued, all necessary means should be sought to produce practically useful outcomes, with the ultimate test of ideas being their capacity to address real-world problems (cf., Biesta and Burbules, 2004). While epistemological aspects are emphasised, its ontology is often neglected, dating back to the classic pragmatists (Pratt, 2016). Since the classical pragmatists did not lay out their ontology, pragmatist ontology has been the subject of many discussions. Several scholars have criticised this ‘anti-ontological’ stance of pragmatism, arguing that its view of reality remains ambiguous and that pragmatism may be both realist and relativist in its orientation, accepting one truth and at the same time, accepting multiple interpretations of reality (Morgan, 2007). This lack of a single, consistent ontology is often regarded as a defining feature of pragmatism (Johnson and Onwuegbuzie, 2004; Kaushik and Walsh, 2019). According to Pratt (2016), Dewey offered a constructivist social ontology, focusing on human agency and action. The capacity for change is, according to Dewey, located within each person and not within overarching structures.

The ontological stance is underemphasised if the practical outcomes of the research efforts are good. The little focus on ontology may be reflected in how pragmatists view theory. The outcome of the research should be practical, and «no theory is absolutely a transcript of reality, but any one of them may from some point of view be useful» (James, 1907, p. 33). Thus, pragmatists have a lower level of ambition relating to finding facts and making truth claims compared to, for example, critical realists. The best theory, according to pragmatism, is the most useful theory. This illustrates the paradigm’s primary research aim: producing knowledge with a clear practical contribution (Kaushik and Walsh, 2019; Morgan, 2014). Sein et al. (2011) adopted a pragmatist stance, emphasising how the research process iteratively refines theory while creating a functioning artefact that solves a real organisational problem.

Pragmatism may be considered as a mid-position between post-positivism and interpretivism since it seeks to reconcile dualisms important to post-positivists and interpretivists (Bernstein, 2010; Farjoun et al., 2015). First, pragmatism relies on abductive reasoning alternating between induction and deduction, where theories are derived from empirical observations and then evaluated. Through a cyclical process, theory becomes increasingly ‘useful’, which is highly appreciated from a pragmatist and practitioner perspective. Epistemologically, this often translates into constructionism—knowledge is actively built in interaction with the world rather than discovered as a fixed reality (Creswell and Clark, 2017; Morgan, 2007). Pragmatists welcome both qualitative and quantitative research methods (Mingers, 2004; Morgan, 2007). This flexibility can be seen in the study by Venkatesh et al. (2013), emphasising what works to understand IS phenomena. Second, pragmatism refuses the subjectivity vs. objectivity dualism. Pragmatism aims at intersubjectivity and holds that any researcher has to work back and forth between subjective stances and the pursuit of mutual understandings with research participants and fellow peers (Morgan, 2007). Third, the final dualism that pragmatism offers a solution for is the distinction between context-dependent and universal knowledge. A pragmatist seeks to expand the usability of a theory—to make the most out of knowledge learned with specific methodologies in specific contexts. There is no point, nor is it possible, to generate knowledge so narrowly focused that it only applies to a particular context. Similarly, social scientists should not hope for knowledge «so generalised that they apply in every possible historical and cultural setting» (Morgan, 2007, p. 72). Instead, pragmatism aims at transferring knowledge from one context to another context. However, this cannot simply be assumed; it must rather be empirically tested and justified (Morgan, 2007). Epistemologically, pragmatism is very liberal, accepting a wide range of methodologies if the purpose is to contribute to something ‘useful’. This orientation toward practical usefulness also explains why action-oriented methods such as action research and design science are commonly used (Baskerville and Myers, 2004; Hevner et al., 2004; Sein et al., 2011).

The IS field has, in various ways, looked to pragmatism for philosophical guidance (Ågerfalk, 2010). The focus on practical outcomes has led to a stronghold of pragmatist philosophy among researchers who conduct design science research (e.g. Hevner, 2007), action research (e.g. Baskerville and Myers, 2004) and action-design research (e.g. Goldkuhl, 2012). Ågerfalk (2010) shows how pragmatic thinking can underpin both interpretive and design-oriented IS research, emphasising the iterative interplay between theory and application. However, IS scholars, drawing upon pragmatism, are not limited to these methodologies nor to an IT artefact as the outcome of the research. It has been promoted by researchers who conduct qualitative (e.g. Goldkuhl, 2012) and mixed-methods research (e.g. Venkatesh et al., 2013). The nature of knowledge in pragmatism is therefore often described as ‘practical’ or ‘instrumental,’ evaluated in terms of whether it works in practice rather than whether it mirrors reality (James, 1907; Morgan, 2014). IS pragmatist researchers have informed policymakers, made practical recommendations and sought to bridge the theory-practice gap. In this context, Gregor and Hevner (2013) frame theory as a pragmatic instrument for guiding real-world innovation rather than as a purely descriptive model

In terms of axiology, pragmatism does not typically prescribe a single, unified role for values and the researcher, leaving this dimension relatively underdeveloped compared to other paradigms (Johnson and Onwuegbuzie, 2004). Values are seen as context-dependent and instrumental, guiding choices insofar as they help to achieve the research aim (Biesta, 2010).

Revisiting our illustrative Danish public sector case, a pragmatist would be attentive to the practical outcomes of the research. They would frame the enquiry around tangible improvements: for example, understanding why citizens keep calling, despite the availability of a self-service application, could reveal problems with the user interface, textual formulations and online forms. A pragmatist would examine both the technical system (e.g. the digital interface, system functionality) and the social system (e.g. organisational routines, citizen expectations and caseworker practices) to identify actionable improvements. Thus, the pragmatist researcher would emphasise generating actionable solutions. For example, by providing practical recommendations for governmental agencies implementing self-service applications. The researcher would use any method he or she deems appropriate for solving the problem, and in some cases, develop new solutions or prototypes that could be used instead of or inspire changes in the existing solutions. The iterative and flexible nature of pragmatist research allows the study of technical and social systems together, capturing how they interact in practice. For instance, a usability change in the technical system may only be effective if organisational routines and user behaviours (social system) are aligned. Whereas a pragmatist would not mind personal experiences of self-services, inquiries that aim to identify patterns in the collected data material are also accepted.

Madsen’s (2016) study does offer several recommendations for practice. However, it does not begin from a problem-solving orientation or the assumption that knowledge is valuable primarily for its practical utility. Therefore, we may say that the primary objective of his research is interpretation rather than intervention. This illustrates a contrast with pragmatism: while a pragmatist would directly act on both technical and social aspects to improve system use, Madsen’s work focuses on understanding socially constructed meanings and practices, emphasising the social system over the technical system. Practical implications, arising from deep understanding, are derivative rather than directive—they emerge as consequences of understanding users’ lived experiences, not as pre-defined goals guiding the research. Even if findings are tied to a specific setting, they can highlight patterns, problems, or considerations that are likely to appear in similar contexts. However, when doing so, limitations must be acknowledged, considering that his implications will not be the same elsewhere.

Pragmatism, finally, emphasises practical outcomes and problem-solving over abstract principles. A key discussion point is that pragmatism’s focus on outcomes makes the research sensitive to technical interventions, but equally attentive to social practices—though this balance depends on the researcher’s priorities and context. Researchers adopting this paradigm focus on what works in a given situation, often using mixed methods to understand and address IS phenomena. The strength of this approach lies in its flexibility and adaptability to various research contexts. Yet, its focus on practical outcomes can sometimes neglect deeper theoretical or philosophical considerations to understand broad conceptual areas. Furthermore, the strong focus on practical impact implies having an end-in-sight as a prerequisite for research, thus encountering criticism that is partly similar to that of critical theory.

Critical theory

Critical theory aims at changing society (Horkheimer, 1972; Kincheloe and McLaren, 1994; Orlikowski and Baroudi, 1991). It emerged as a reaction to post-positivism and, to some extent, interpretivism. Critical theorists criticise post-positivism for reinforcing unhealthy power structures, strengthening managerial control and defending the status quo (Alvesson and Deetz, 2000). Whereas they agree with interpretivists that the social world is (re)created by humans (Berger and Luckmann, 1967), they acknowledge that structures exist in which human agency is limited. These structures may not be directly observable. Critical theorists seek to emancipate the oppressed, challenge the status quo and engage in deep investigations of contexts to uncover hidden forms of domination and oppression (Myers and Klein, 2011). For example, Silva and Backhouse (2003) demonstrated how information systems reinforced hierarchical power relations within a UK organisation, illustrating how invisible structures constrain agency. In the context of the Danish public sector case, this means looking beyond the immediate operational challenge of frequent calls from single parents and instead examining the systemic structures—such as institutional design, service accessibility and embedded gender norms—that shape and constrain their interactions with the agency.

IS research follows the critical tradition in fields such as philosophy, sociology and management (Cecez-Kecmanovic, 2005; Mingers, 2001). IS is mostly influenced by the ‘Frankfurt School’ of philosophers, especially Habermas’ action theory (Habermas, 1984; Oates et al., 2022), but also by Bourdieu and Foucault (Bourdieu, 1986; Foucault, 1977; Myers and Klein, 2011). According to Howcroft and Trauth (2004), IS critical theory has four characteristics:

-

Emancipation: Critical theorists try to emancipate the oppressed by empowering them, having an activist orientation (Fay, 1987; Kincheloe and McLaren, 1994). Myers and Young (1997) revealed how developers’ assumptions marginalised user voices during system implementation. In the Danish case, this perspective might involve enabling single parents to articulate their own service needs and participate in reshaping digital systems.

-

Critique of tradition: Critical theorists do not accept the status quo, challenging taken-for-granted assumptions and practices (Cecez-Kecmanovic, 2005; Horkheimer, 1972). Here, this could mean questioning entrenched bureaucratic routines that assume all clients can navigate complex online forms.

-

Non-managerial perspective: Critical theorists reject research that takes a managerial approach focusing on increased productivity and performance, often at the expense of ordinary workers (‘Critical Management Studies,’ 1992). For example, Stowell and West (1994) highlight how managerial control often co-opts participatory ideals in system design.

-

In our case, rather than simply measuring the efficiency gains from automated responses, the analysis would consider whether these systems marginalise certain citizens.

-

Critical reflection of self-conducted research: Critical theorists do not believe in value-free research, such as positivists and are critical of their research (Lincoln and Guba, 1985; Oates et al., 2022)

Critical research does not separate facts from values, meaning researchers and informants are expected to carry values (Schwandt, 1994). Both the value-free post-positivist researcher and the value-neutral interpretivist researcher are rejected since they reinforce power structures. Any research effort would involve values, and therefore, researchers should state their value positions explicitly (Cecez-Kecmanovic, 2005; N. K. Denzin, 1989). Applied to our case, this would require the researcher to acknowledge their stance on issues such as social inclusion, accessibility and citizens’ rights to equitable service.

Critical IS researchers have investigated a variety of topics and issues (Masiero, 2021; Walsham, 2005). They seek to reveal distorted consciousness and hidden forms of domination and oppression through or assisted by IS. For example, web accessibility for disabled people, unequal power relations in IS development and gender bias in IT work. For example, Kvasny (2006) examined how community IT initiatives reinforced existing racial and gender divides despite emancipatory intentions. In our Danish case, this perspective might highlight that frequent calls are not just ‘user errors’ but potentially the outcome of a digital system designed without adequate consideration of users with lower digital literacy or limited resources. A value-neutral approach to IS is of particular concern for critical theory (Mingers and Walsham, 2010). The over-emphasis on how IS can achieve goals such as increased efficiency, performance and productivity is also of concern, as wider social and political implications are not studied and critically examined (Cecez-Kecmanovic, 2005). More recently, critical IS research has engaged with other issues such as race and gender in addition to economic factors (Adam et al., 2004; Myers and Klein, 2011).

Critical theory is neither nomothetic nor idiographic and takes the form of a map for the scientist to understand a social setting and change it (Fay, 1987). According to Alvesson and Deetz (2000), critical theory has three functions: directing attention, organising experience and enabling useful responses. It directs our attention ‘by providing a conceptual apparatus that makes certain distinctions relevant and certain differences visible’ (Cecez-Kecmanovic, 2005, p. 35). Critical social theory, a set of critical approaches and theories, is the theoretical core of critical IS research (Cecez-Kecmanovic, 2005; Fay, 1987). IS researchers have applied a wide range of theories to IS-specific problems. For example, institutional theory, feminist writings, labour process theory, critical systems theory, critical post-modernism and a postcolonial perspective. Critical theory is validated through its ability to inform research subjects, helping them achieve awareness of situations and bringing forth change (Cecez-Kecmanovic, 2005; Kincheloe and McLaren, 1994). In our case, the measure of validity would not just be whether call volume decreases, but whether single parents gain agency in influencing how digital welfare services are designed and delivered.

Critical IS theorists use several methodologies. Earlier, longitudinal studies were prioritised (Mingers, 2001; Orlikowski and Baroudi, 1991) because of the deep immersion into topics. The lack of clarity has been criticised, claiming it is difficult for critical theorists to justify their findings based on methodological ambiguity (Myers, 1997). One approach put forth by critical theorists is to develop and apply distinct critical methodologies such as critical ethnography and participatory action research (Kemmis and McTaggart, 2005; Madison, 2011). Another approach has been concerned with the choice of methodologies in specific contexts. Myers and Klein (2011) found that case studies, ethnographies, field studies and conceptual studies were common. The change aspect does not favour any particular methodology if it promotes intervention (Mingers, 2003; Reason and Bradbury, 2001). Myers and Klein (2011) suggest that critical research may be useful for action and design science by considering the social and ethical aspects of interventions. For example, in our case, a participatory action research project could involve single parents co-designing service features alongside developers and caseworkers.

Applied to the Danish public sector case, a critical theorist would not only investigate the underlying reasons for single parents’ continuous calls but also actively challenge the institutional and technological arrangements that perpetuate inequality—using a normative lens. This might involve amplifying the voices of marginalised groups, exposing biases in the digital systems and advocating for inclusive redesign. Although Madsen (2016) emphasised the importance of addressing barriers faced by disadvantaged or less ICT-literate individuals, which aligns with a critical theory lens, the primary focus remains on making sense of individuals’ usage patterns and improving the functionality and accessibility of e-government channels. Thus, his philosophical stance separates from the critical theorist, not in terms of methodology, but based on the main objectives of the research.

The emancipatory focus has been criticised. First, research objectives may appear utopian: how should critical theorists be able to emancipate people conditioned by or based on IS? (‘Critical Management Studies,’ 1992). Critical theorists respond that such goals are important even if not achieved fully. Next, the critical project may appear arrogant, seeking to emancipate others (Thomas, 1993). Furthermore, critical research may end up establishing a new dominating power, reflecting critical theory values (Fay, 1987). Finally, critical theorists take an a priori stand, perhaps selecting empirical context based on who they believe needs emancipation (Kincheloe and McLaren, 1994). To this, critical theorists argue that a fundamental part of their tradition is also to question their research and that values play an important role in all research efforts (Lincoln et al., 2011). In our case, this self-reflection could mean recognising that the researcher’s own interpretation of ‘marginalisation’ might differ from how single parents themselves understand their situation.

Comparing the paradigms

Much of the motivation behind the attempt to model IS research on natural science (and other social sciences) lies in the appreciation of its predictive and explanatory power. Because of this, the methodological toolsets of natural science researchers have been identified and applied in our domain, hoping to achieve the same theoretical insights (Rosenberg and McIntyre, 2020). From these early hopes until today, several IS researchers have concluded that this may become a difficult exercise (e.g. Hirschheim and Klein, 2012). While natural sciences often work with controlled experiments and quantifiable regularities, social sciences tend to address meanings, contexts and complex interdependencies—yet the boundary is not absolute, and methods can be shared or adapted across both. Whereas this development has led to alternative explanations of the social world, there is a disagreement as to how far these explanations should stray from the passed-down and well-respected scientific tradition. Importantly, the relationship between philosophical positioning and empirical practice is not one-to-one; researchers may draw on methods from different traditions for pragmatic or problem-driven reasons, rather than out of strict philosophical necessity. When some IS researchers, for example, interpret citizen interaction with a new Danish self-service application in radically different ways depending on their stance, tensions inevitably occur. The five paradigms presented in this article reflect these differences in opinions, as they represent common ways of understanding philosophical ideas in the IS field.

The main tensions concerning these stances revolve around the nature of the social reality, the possibility of knowing that reality and the role of values and power in research. Post-positivism holds that while an objective reality exists, our understanding of it is always fallible and imperfect. Thus, it questions our ability to make absolute and objective truth claims due to the complexity of human experience. Applied to the Danish case, a post-positivist might focus on technical system metrics, such as usage logs or survey responses, to identify statistically reliable patterns, but may underrepresent the social practices shaping these interactions. Critical realism is similar to post-positivism in that it shares the belief in an objective social reality, and our understanding of this reality is mediated by social, cultural and linguistic factors. However, whereas post-positivism places more emphasis on empirical observations, critical realism emphasises underlying structures that might not always be observable. A critical realist would agree that the observable usage patterns matter but would also seek to uncover deeper structural factors—including both technical mechanisms (system affordances, workflow processes) and social structures (bureaucratic routines, socio-economic inequalities, trust dynamics)—that constrain or enable citizens’ ability to use the system.

Diverging from these stances, pragmatism concerns itself less with the nature of reality and more with what works in practice. For pragmatists, truth is what is useful and practical. This means pragmatist research explicitly attends to both technical and social systems: improving the user interface (technical) while also redesigning support workflows or communication channels (social) to achieve better practical outcomes. They argue that concepts and theories should be judged by their practical applicability, sidestepping foundational debates about reality and knowledge. In the Danish case, a pragmatist might focus on testing alternative support mechanisms or interface designs, prioritising whichever leads to the most effective citizen uptake, regardless of theoretical alignment. Pragmatism is a flexible paradigm, bridging the chasm between post-positivist and interpretivist methods. Critical theory can resemble pragmatism in its apparent negligence of ontological questions and its concern for real-life problems. However, rooted in the Marxist tradition, it has a strong socialist focus on power, inequality and social change. Critical theory emphasises the social system, examining how structural inequalities, digital exclusion, or organisational power dynamics shape interactions with technical systems. From a critical theory perspective, the Danish case could be read as a manifestation of digital exclusion, where the system privileges certain groups while marginalising others—calling for political and structural change rather than mere technical fixes. Critical theorists argue that knowledge is always power-dependent, something researchers should be aware of and address. They are deeply sceptical of neutrality claims in research, emphasising the role of ideology and power dynamics in the construction of knowledge.

In stark contrast, interpretivism posits that social reality is socially constructed and can only be understood from the various views of individuals who live and interpret it. Interpretivism primarily emphasises social systems—understanding practices, meanings and interpretations—while engaging with technical systems only as they are experienced and enacted by participants. It challenges the idea of a single, objective reality, suggesting the existence of multiple, subjective realities shaped by human experiences and interpretations. An interpretivist examining the Danish self-service case would prioritise in-depth interviews or ethnographic observations, aiming to understand how different citizens make sense of the system, what meanings they attach to it and how it fits into their everyday life. Interpretivists appreciate the values of informants and an openness about values in research enquiries.

Identifying oneself with any of these philosophical paradigms involves a mixture of personal introspection and professional consideration. Personally, every researcher brings with him or her beliefs about the world based on reasons such as cultural and religious affiliations. Likewise, researchers are influenced professionally by beliefs such as educational background, disciplinary practices, influences from mentors and research ethics. However, philosophical orientation does not wholly dictate empirical choices; mixed-methods research, cross-paradigm borrowing and methodological pluralism are increasingly common in IS. As illustrated in Table 2, our illustrative case provides a concrete anchor for comparing these paradigms, showing how each leads to different research aims, assumptions before a study is conducted and shows their potential strengths and weaknesses.

Studying information systems: looking forward

This article analysed an IS case from the Danish public sector, using different philosophical stances to illustrate how alternative philosophical positions can shape the interpretation of the case without necessarily dictating the empirical investigation or its findings. The problem observed was that a significant number of citizens kept calling despite having access to self-service solutions (Madsen, 2016). Observing this, Madsen (2016) began to investigate why this happened. As illustrated in this article, researchers adhering to different philosophical stances will approach and study this phenomenon with different aims and underlying assumptions. However, these philosophical commitments do not operate in isolation from empirical practice—data, context and methodological constraints can influence or even override the implications of a given stance. How closely, then, are these aims and underlying assumptions related to the different paradigms? Whereas philosophical paradigms have served as anchor points for the IS field, grounding our understanding of existence, knowledge and morality, their potential strength—being foundational and unyielding—can also be a limitation. Several researchers have noted that a tight boxing-in of the paradigms is difficult to see (Hassan et al., 2018; Lystbæk, 2018). Historically, philosophical ideas have transcended paradigms, books, philosophers and time. There is simply no clear and organised definition of philosophical ideas, and considerable areas of overlap between the various paradigms exist (Lincoln and Guba, 2000).

Acknowledging the fundamental assumptions of a specific research paradigm does not suggest that these assumptions are isolated, form a unified and logically consistent pattern, or that they can easily be integrated. Rather, paradigms serve as heuristics of research (Kaushik and Walsh, 2019; Lystbæk, 2018) and are subjected to continuous discourse (Habermas, 1984). While understanding the philosophical underpinnings of IS research is essential—guiding our choices as researchers—it is important to understand that IS investigations are also influenced by more tangible factors than mere philosophical assumptions. Disciplinary ways of conducting research can influence the topic of enquiry, data analysis and interpretation of the findings. Furthermore, a researcher’s preferred theories, personal and professional experiences, contextual dynamics and political considerations can play significant roles in shaping IS research (Kaushik and Walsh, 2019). In this sense, the link between a paradigm and a set of empirical outcomes is often loose, mediated by multiple contingent factors.

Therefore, the paradigms presented in this article can merely be considered overviews of how scientific IS knowledge could be studied and should not serve as authoritative templates for IS research (Hassan et al., 2018). Nevertheless, that is what IS researchers, to a large extent, have done, even relating their preferences for philosophical paradigms to choices of methodology, and therefore, reducing philosophical discussions to methodological debates (Hassan et al., 2018). This tendency illustrates the cautionary point by the Austro-British philosopher Wittgenstein (1953): when philosophical tools are treated as fixed doctrines rather than as aids for conceptual clarification, they risk becoming constraints rather than sources of insight. Instead, the paradigms should be stances from which much more fruitful ontological, epistemological and axiological discussions are sought about what IS knowledge is and should be.

We may claim that the main overarching purpose of conducting IS research (or any other type of research for that matter) is to contribute to a better world (Walsham, 2012). As such, IS research should first and foremost be phenomenon-centric, problem-focused and continuously open and curious about the technological developments in society. A good starting point could be to philosophise about the main properties of the phenomena we study. Such discussions could help us communicate and compare knowledge. As argued by Hassan et al. (2018), how can we be sure of the knowledge we create if we do not agree upon the essence of what we are studying? For example, in our illustrative case, there are many opportunities to philosophise about what e-government fundamentally is and should be, as well as what it means to various groups of citizens to use e-government services and systems.