Abstract

Research on organizational attractiveness (OA) has largely focused on potential employees, with limited attention to how current employees perceive their organization’s appeal, especially in developing country contexts. This study examines how ethical leadership (EL) shapes OA through the mediating roles of green human resource management (GHRM) practices and job satisfaction (JS). A survey of 215 employees from Qatari public sector organizations was analyzed using structural equation modeling with SmartPLS. The results reveal that EL positively influences OA, both directly and indirectly, through GHRM and JS, with evidence of sequential mediation. By integrating social exchange theory and supply-value fit theory, the study highlights the mechanisms through which leadership enhances employees’ perceptions of OA. The results provide actionable insights for managers and policymakers seeking to strengthen employer branding, foster JS, and implement sustainable human resource practices to retain talent.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In today’s competitive business environment, organizational attractiveness (OA) has become a critical factor in the recruitment and retention of top talent. As organizations increasingly focus on sustainability and social responsibility, organizational values such as ethical leadership (EL) are playing a pivotal role in shaping their attractiveness (Möbert et al., 2025). EL, which involves demonstrating normatively appropriate conduct through personal actions and fostering trust and transparency in relationships (Brown et al., 2005), has been shown to influence employee behaviors and perceptions. In particular, ethical leaders create an inclusive and responsible work environment, which not only enhances employee satisfaction but also aligns organizational values with those of the employees, strengthening the organization’s appeal as a desirable place to work (Benevene et al., 2018). EL helps organizations build a positive reputation, especially when it comes to attracting employees who value ethical conduct in the workplace (Dey et al., 2022; Ogunfowora, 2014). However, despite the well-documented benefits of EL, its impact on OA remains unexplained, especially from the perspective of current employees (Strobel et al., 2015). This gap is particularly significant given the increasing competition for talent, particularly in regions like the Gulf, where organizational values such as sustainability are becoming central to the employee value proposition.

In the Gulf region, Qatar stands at the forefront of these changes, driven by its Vision 2030 reform agenda, which emphasizes sustainability, environmental responsibility, and the development of EL across sectors (ElGammal et al., 2018). The public sector in Qatar, in particular, has been a key player in this transformation, with the government actively encouraging organizations to adopt greener practices and integrate CSR initiatives into their operations (Al-Swidi et al., 2021). These efforts are not only aimed at improving environmental outcomes but also at positioning public sector organizations as ethical and socially responsible employers, enhancing their OA.

While EL plays a critical role in enhancing OA, the influence of green HRM (GHRM) practices adds a unique dimension to this relationship. GHRM practices encompass HR initiatives aimed at promoting environmentally responsible behaviors among employees, such as green hiring, training, and incorporating environmental performance into appraisals and rewards (Renwick et al., 2013). These practices not only contribute to an organization’s sustainability goals but also serve as a signal of the organization’s ethical and environmental commitment, contributing to higher job satisfaction (JS), which is often linked to increased loyalty and enhanced OA (Sypniewska et al., 2023). By integrating GHRM practices, organizations can further enhance their attractiveness by aligning their green initiatives with employee values, particularly for those who prioritize sustainability in their professional environment (Sypniewska et al., 2023). In the context of Qatar, where CSR and sustainability are increasingly becoming core values, GHRM practices can serve as a critical mechanism through which EL can enhance OA. When such practices are combined with EL, employees are more likely to experience JS, since they perceive their organization as trustworthy, fair, and aligned with their own ecological and ethical values (Aftab et al., 2023; Yasir and Javed, 2024).

In this regard, a growing body of research has examined the role of EL in shaping employees’ pro-environmental behaviors and outcomes. For example, Ahmad et al. (2021) demonstrated how EL promotes green behavior through green HRM and environmental knowledge, while Islam et al. (2021a) showed that EL promotes environment-specific discretionary behavior via GHRM as a mediator and individual green values as a moderator. While these studies have focused on the mechanisms by which EL promotes sustainable behaviors among employees, highlighting the importance of integrating leadership with HRM practices to encourage pro-environmental outcomes, they have largely overlooked OA as an important outcome. This gap is particularly significant to address, given the positive organizational outcomes associated with EL, such as enhancing OA to potential employees (Strobel et al., 2015), and its negative correlation with current employees’ intentions to leave the organization (Lin and Liu, 2017). Furthermore, most existing work has concentrated on the perceptions of potential employees (Huang, 2022; Younis and Hammad, 2021), neglecting the perceptions of current employees, whose retention is critical to organizational success (Pandita and Ray, 2018). Evidence indicates, however, that the attributes valued by current employees may differ significantly from those prioritized by job applicants (Dassler et al., 2022; Reis et al., 2017). Therefore, addressing this gap is crucial, as OA not only determines the ability of organizations to recruit talent but also plays a decisive role in retaining skilled employees. In all, while EL has been linked to JS and organizational outcomes, the mechanisms through which it influences OA, particularly via GHRM and JS, remain insufficiently understood.

To address these gaps, this study examines whether EL influence OA in the context of Qatari public sector organizations. Specifically, it examines how GHRM practices and JS act as mediating mechanisms linking EL to employees’ perceptions of their organization as an attractive workplace. This focus is especially relevant in Qatar, where public sector organizations are under growing pressure to meet sustainability targets and retain highly skilled employees in a competitive labor market. Accordingly, this study is guided by the following research questions:

RQ1. How does EL influence OA from the perspective of current employees in Qatari public sector organizations?

RQ2. How do GHRM practices and JS mediate the relationship between EL and OA in the context of Qatari public sector organizations?

By addressing these questions, the contribution of this study is threefold. First, it extends the literature on OA by examining its determinants from the perspective of current employees, an area often overlooked in studies that focus primarily on prospective employees, despite its importance for employee retention. Second, it integrates social exchange theory (SET) and supply-value fit theory (SVFT) to explain how EL, GHRM, and JS interact to enhance OA, as well as the mediating role of GHRM and JS. Third, it responds to the call for more research in underexplored contexts by situating the study within Qatari public sector organizations, where sustainability and ethics are increasingly central to organizational strategy. While prior research has examined the outcomes of ethical or unethical leadership (Ahmad et al., 2019; Blair et al., 2017; Hosseini and Ferreira, 2023; Rahaman et al., 2021; Ullah et al., 2022), little is known about how it influences perceptions of OA internally, especially within developing country contexts such as Qatar.

Literature review

Theoretical foundation

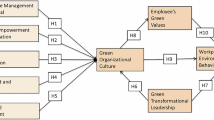

Drawing on the SET and SVFT, this study provides a thorough understanding of the mechanisms through which EL shapes OA via GHRM and JS, from the perspective of current employees in Qatari public sector organizations, as shown in the research model presented in Fig. 1.

SET posits that relationships within organizations are governed by the principle of reciprocity, where favorable treatment by leaders fosters positive attitudes and behaviors among employees (Cropanzano and Mitchell, 2005; Zhou and Zhang, 2025). It contends that EL enhances JS and OA by creating a fair, transparent, and supportive work climate (Ahmad and Umrani, 2019). Indeed, ethical leaders, through genuine concern and fair practices, elicit reciprocal commitment, loyalty, and satisfaction among employees, which ultimately improves their perception of the organization as an attractive workplace (Benevene et al., 2018).

Along with SET, SVFT emphasizes the alignment between employees’ personal values and the values embedded within organizational practices (Edwards, 1996). This theory is particularly relevant for understanding the role of GHRM in this study, as employees who hold strong green values are more inclined to perceive their work as meaningful in organizations that adopt green HRM practices (Zhou and Zhang, 2025). When companies implement GHRM practices, such as green recruitment, training, and appraisal, they signal alignment with employees’ ecological and ethical values, enhancing their sense of belonging and satisfaction, where employees prefer to work for companies with values that align with their own (Ahmad and Umrani, 2019). By integrating SET and SVFT, this study provides a comprehensive framework that links leadership behaviors and human resource practices to employee outcomes, explaining how EL indirectly enhances OA through mechanisms rooted in reciprocity and value congruence. Table 1 highlights the connections between EL, GHRM, JS, and OA, supported by SET and SVFT that guide the development of hypotheses.

Organizational attractiveness

OA is defined as “an attitude or expressed general positive affect toward an organization, more specifically toward viewing the organization as a desirable entity to be associated with” (Smith et al., 1999). According to Berthon et al. (2005), OA reflects an employee’s perception of the advantages of working for a specific company. From the viewpoint of current employees, OA revolves around the inner and outer factors that make a company a desirable workplace and retain talent (Kalińska-Kula and Staniec, 2021). This perspective emphasizes the importance of employee satisfaction, engagement, and alignment with the company’s values and culture (Staniec and Kalińska-Kula, 2021). Key drivers include equitable compensation, opportunities for professional growth, a supportive work climate, recognition of contributions, and work-life balance. Employees are also drawn to organizations that foster inclusivity, demonstrate EL, and provide a clear sense of purpose (Staniec and Kalińska-Kula, 2021). When these elements are present, employees perceive their workplace as more attractive, leading to enhanced loyalty, advocacy, and overall organizational commitment. This dynamic is critical for sustaining a motivated and high-performing workforce, as well as reducing turnover. According to Vokić et al. (2022), there are many factors that enhance OA, which include functional or instrumental attributes, which are rational and tangible aspects like “salary, benefits, job security, working conditions, and opportunities for promotion”, as well as symbolic attributes, which encompass emotional and intangible elements such as “organizational culture, social approval, and ethical or social responsibility”.

While prior research has highlighted the importance of EL (Brown et al., 2005; Benevene et al., 2018) and its link to positive employee outcomes, several gaps remain. First, most studies on OA have primarily focused on potential job applicants (Huang, 2022; Younis and Hammad, 2021), while the perceptions of current employees, who are critical for retention, remain underexplored (Pandita and Ray, 2018). Second, while EL has been shown to influence JS and related outcomes (Neubert et al., 2009; Benevene et al., 2018), the mechanisms through which it shapes OA are still insufficiently understood, particularly with respect to the sequential roles of GHRM and JS (Ahmad and Umrani, 2019; Abdelhamied et al., 2023). Third, much of the existing evidence has been generated in the private sector or Western contexts, leaving public sector organizations in developing countries relatively overlooked (Nguyen et al., 2023). Finally, there is limited integration of multiple theoretical perspectives to explain these dynamics, with few studies combining SET (Cropanzano and Mitchell, 2005) and SVFT (Edwards, 1996) to uncover the pathways linking leadership behaviors, HRM practices, and employee perceptions of attractiveness. Addressing these gaps, this study examines how EL influences OA through GHRM and JS within Qatari public sector organizations, thereby extending the literature to an underexplored context.

Ethical leadership and organizational attractiveness

EL is defined as “the demonstration of normatively appropriate conduct through personal actions and interpersonal relationships, and the promotion of such conduct to followers through two-way communication, reinforcement, and decision-making (Brown et al., 2005, p.120).” Brown and Treviño (2006) describe ethical leaders as individuals who demonstrate honesty, trustworthiness, and fairness, consistently upholding ethical behavior in both their personal and professional lives. What sets ethical leaders apart is their focus on managing with a strong ethical perspective (Joplin et al., 2021). Additionally, they emphasize their subordinates’ development, empower them through delegation, establish ethical guidelines, clarify roles, ensure fairness, and provide appropriate rewards and recognition (Islam et al., 2021b). In this sense, an ethical leader serves as a compassionate, just, and morally motivated role model who sets an example, upholds behaviors aligned with ethical norms that employees adopt and follow, and fosters open communication, encouraging employees to express their concerns and opinions (Dua et al., 2023). By promoting fairness and open communication, EL helps create a workplace culture that minimizes the risk of scandals, fraud, and misconduct (Dua et al., 2023; Pletz et al., 2024).

EL behavior has been studied and empirically proven to contribute to positive outcomes for subordinates, including increased JS (Neubert et al., 2009) and enhanced organizational creativity and innovation (Shafique et al., 2020). According to Möbert et al. (2025), EL signals influence employer attractiveness through trust in the leader. This is because EL provides immediate insights into an organization’s internal ethical climate, as it is both shaped by and reflective of this environment (Brown and Treviño, 2006). Employees frequently interact with leaders and are directly impacted by their ethical or unethical decisions and actions. Additionally, the public is becoming more aware of how executives behave within a business, and ethical lapses by leaders often receive widespread media attention, potentially damaging the corporate reputation (Strobel et al., 2015). In line with this, we assume that:

H1. EL is positively related to OA.

Ethical leadership, green HRM, and organizational attractiveness

While the literature suggests that organizations should reassess their practices due to their potential environmental harm (Ahmad et al., 2022; Islam et al., 2021b), it does not clarify how EL influences GHRM practices. On the one hand, several studies highlight the significance of aligning leadership with HRM to convey a clearer message to employees (Leroy et al., 2018; Vermeeren et al., 2014). However, many organizations struggle to align leadership with HRM practices and policies, often due to hesitance from either leaders or HR personnel regarding similar approaches (Leroy et al., 2018). On the other hand, some argue against the inconsistency between leadership and HR practices, suggesting that both play a role in promoting environmental sustainability, as EL and GHRM are both rooted in ethics (e.g., Islam et al., 2021a, b).

Although GHRM practices encourage environmentally friendly behaviors among employees, contributing to a workplace that is socially responsible, efficient with resources, and ecologically aware (Al-Swidi et al., 2022; Saeed et al., 2019), achieving these goals requires genuine leadership. Ethical leaders prioritize the environment and are therefore more effective in implementing GHRM practices to protect it (Islam et al., 2021a). Haddock-Millar et al. (2016) emphasize the importance of ethical leaders who are genuinely committed to ecological sustainability. Indeed, leaders with ethical values foster a climate of the highest ethical standards and are expected to promote practices that are fair and grounded in strong ethical principles, such as GHRM practices, when they prioritize sustainable development goals. According to Ahmad and Umrani (2019), ethical leaders typically design HRM practices that align with the goals of the company, environment, and employees. Ethical leaders invest in employee development, enhancing the business environment and welfare (Walumbwa et al., 2017). They also adopt GHRM practices linked with appointment, training, and evaluation (Ahmad and Umrani, 2019). In this regard, Ahmad et al. (2021) and Islam et al. (2021a) support the notion that EL positively influences GHRM practices. Thus, we argue that organizations can more effectively implement GHRM practices through EL. Hence, we postulate:

H2a. EL is positively related to GHRM.

On the other hand, there is a growing demand for GHRM practices that focus on environmental objectives, as these practices assist organizations in aligning their HR strategies with broader organizational goals (Islam et al., 2021b). GHRM is defined as those “HRM activities which enhance positive environmental outcomes” (Kramer, 2014, p. 1075). GHRM practices involve incorporating green values when recruiting and selecting candidates, providing environmental training and raising awareness about ecological sustainability, evaluating employees’ eco-friendly behaviors during performance appraisals, and incorporating these behaviors into rewards management (Al-Swidi et al., 2024; Renwick et al., 2013). GHRM enables the development of ecological skills and encourages employees to participate in the company’s green initiatives (Saeed et al., 2019).

While many studies have emphasized the importance of green work behaviors such as GHRM practices in achieving organizational outcomes like ecological performance (Al-Swidi et al., 2024), few have explored how pro-environmental work behaviors, like GHRM, contribute to enhancing an organization’s attractiveness (Umrani et al., 2022). Based on SVFT assumptions, employees prefer to work for companies with values that align with their own (Ahmad and Umrani, 2019). As such, employees are more likely to remain loyal to companies that adopt GHRM practices, as it reinforces their belief that they are part of an organization making a positive impact. Thus, we suggest that:

H2b. GHRM is positively related to OA.

Furthermore, this positive association may be influenced directly by EL. Specifically, ethical leaders play a pivotal role in driving GHRM initiatives by embedding principles of fairness, transparency, and sustainability into HR policies, including green recruitment, training, and performance appraisal (Ahmad and Umrani, 2019; Renwick et al., 2013). Such practices serve as strong signals of the organization’s ethical and environmental responsibility, fostering greater alignment between employee and organizational values and thereby enhancing perceptions of OA (Merlin and Chen, 2022; Guillot-Soulez et al., 2022). Therefore, we propose that:

H2c. GHRM mediates between EL and OA.

Ethical leadership, job satisfaction, and organizational attractiveness

SET contends that fair treatment of employees by ethical leaders influences their appraisals of their jobs more positively, in accordance with the principle of reciprocity (Ahmad and Umrani, 2019). Indeed, ethical leaders who show genuine concern and fairness toward their employees tend to become appealing role models, a quality further enhanced by status and authority typically associated with leadership (Benevene et al., 2018). Importantly, employees who perceive their ethical leader as a role model tend to experience enhanced JS, driven by the trust and respect they hold for their leader (Ogunfowora, 2014). Existing evidence reveals that EL influences JS (Freire and Bettencourt, 2020). In a similar vein, Neubert et al. (2009) observed that employees exhibit higher JS and organizational commitment when operating within an environment marked by ethical behavior, honesty, care for others, and fairness. This suggests that organizations perceived as virtuous are inherently regarded as ethical (Benevene et al., 2018). According to Aftab et al. (2023) and Yasir and Javed (2024), EL enhances a sense of spirituality and improves JS. Hence, we postulate that:

H3a. EL is positively related to JS.

On the other hand, the relationship between JS and OA has attracted little attention. According to Kalińska-Kula and Staniec (2021), JS is used as one of the measures of OA. JS for current employees plays a pivotal role in enhancing OA, as it serves as both a reflection of the work climate and a signal to potential employees. Furthermore, the JS of current employees acts as an indirect measurement of OA by providing insight into factors such as work culture, management quality, and career development opportunities (Najm et al., 2023). High levels of JS are often seen as a sign that the organization prioritizes and supports its employees, enhancing its appeal in a competitive job market. Satisfied employees are likely to demonstrate higher levels of loyalty, which enhances the organization’s reputation as a desirable place to work (Najm et al., 2023). This positive perception is communicated through word-of-mouth, social media, and employer reviews, influencing how potential employees evaluate the organization. Keeping in view these arguments, the following assumption is made:

H3b. JS is positively related to OA.

However, there is a justification that this positive association can be directly influenced by EL. By promoting fairness, respect, and trust, ethical leaders cultivate a supportive and constructive work environment, which enhances employees’ JS (Aftab et al., 2023; Benevene et al., 2018). Higher JS, in turn, strengthens employees’ attachment to the organization and improves their perceptions of it as an attractive place to work (Najm et al., 2023). Accordingly, we assume that:

H3c. JS mediates between EL and OA.

The mediating role of green HRM and job satisfaction

JS is defined as “a pleasurable or positive emotional state resulting from the appraisal of one’s job or job experience (Locke, 1976, p. 1300)”. As per Al-Sabi et al. (2024), employee JS is a key outcome of green practices within the organization. Previous research indicates that HRM practices possess the capacity to influence and assess employees’ pro-environmental behaviors (Pinzone et al., 2019). This notion stems from the understanding that employees spend approximately one-third of their daily time in organizational settings. Consequently, implementing policies and practices that encourage eco-friendly behaviors among employees can yield enduring impacts (Blok et al., 2015). Therefore, GHRM plays a pivotal role in driving behavioral change at the individual level. Drawing on the SVFT (Edwards, 1996), the alignment between organizational values and employees’ values fosters positive attitudes and a strong sense of attachment to the organization’s purpose. Ahmed et al. (2025a) supported this view, as they found that supply-value fit is a predictor of work outcomes, such as JS.

Indeed, socially responsible organizational practices, or GHRM practices, are positively perceived by employees (Vadithe et al., 2025). Therefore, when these HRM practices align with employee values, they foster favorable employee attitudes within the organization (Cohen and Liu, 2011; Moin et al., 2021), as employees feel more satisfied with being a member of a responsible organization, which will consequently enhance their JS. Past research supports the GHRM-JS relationship (Abdelhamied et al., 2023; Vadithe et al., 2025; Xie et al., 2023). Hence, we propose:

H4. GHRM is positively related to JS.

In addition to their mediating roles, GHRM and JS also operate as sequential mechanisms linking EL to OA. From the perspective of SET, ethical leaders foster a climate of reciprocity and trust by modeling fairness, integrity, and transparency. These behaviors encourage employees to reciprocate by engaging with and supporting organizational initiatives, including GHRM practices. Once implemented, GHRM policies embed ecological and ethical values into the organization’s HR framework (Ahmad and Umrani, 2019). When employees perceive that organizational values (sustainability, fairness, ethical responsibility) align with their personal values, they experience stronger identification with the organization. This alignment translates into higher JS, as employees feel their work has meaning and is congruent with their beliefs, which is consistent with SVFT. In other words, JS emerges as a critical link, as it reflects the employees’ emotional and cognitive responses to the alignment of organizational practices with their personal values. Employees who perceive their leaders as ethical and their organization as environmentally responsible feel higher JS (Neubert et al., 2009), which translates into a more positive perception of OA. Additionally, this research indicates a substantial association between GHRM and JS, which is consistent with Hypothesis 4, showing that they may play a role as sequential mediators in the EL-OA link. Together, these mechanisms delineate a pathway wherein EL indirectly enhances OA through the sequential mediating roles of GHRM and JS. Therefore, it makes sense to suggest that the relationship between EL and OA is mediated by the sequential effects of GHRM and JS. Considering the above, the following theory is put forth.

H5. GHRM and JS Sequentially mediate between EL and OA.

Methods

Participants and procedures

To assess the proposed model, a survey-based research approach was employed. The questionnaire was distributed on a cross-sectional basis to employees in various public sector organizations in Qatar. Given the absence of a predefined sampling frame of all public sector employees in Qatar, an issue common in organizational studies, a convenience sampling technique was employed, consistent with the approach used in similar studies (e.g., Apolinario et al., 2023; Gelaidan et al., 2024). According to Teddlie and Yu (2007), convenience sampling is “a form of non-probability sampling where participants are selected from the target population based on how easily they can be accessed, contacted, and their readiness to take part in the study”. This method is frequently used in business research to address problems, such as low participation rates and non-response bias (Watson et al., 2013). More importantly, convenience sampling is often considered a practical alternative to random sampling with ethical considerations, as it prioritizes respondents’ accessibility and reduces their potential discomfort (Ahmad et al., 2025b; Landers and Behrend, 2015).

While this approach facilitated timely and cost-effective data collection (Hair et al., 2003), it may limit the generalizability of the findings to broader populations, as the sample may not fully represent all employees in the Qatari public sector or in other contexts. Nonetheless, Mehta et al. (2019) argued that this concern can be mitigated by selecting participants from a wide range of organizations and locations. Consistent with this guidance, the present study included employees from multiple Qatari public sector organizations. After coordination with the respective HR departments to distribute surveys, the employees who were available and willing to participate were invited to complete the questionnaire.

Although the absence of a formal sampling frame may restrict the generalizability of the results, several steps were taken to reduce potential bias and ensure the validity and reliability of the measures. The questionnaire was first reviewed by four academic experts, who provided feedback to improve its clarity and relevance. Following this, a pilot test with five participants from the target population was carried out to verify that the items were interpreted as intended.

A total of 400 participants were invited to participate in the survey, and 230 responses were received over a 3-month period (January–March 2024). Of these, 215 were complete and usable, resulting in a response rate of 54%. This sample size is considered adequate for SEM. According to Hair et al. (2019), a sample size greater than 200 is sufficient for models of moderate complexity. To further validate the adequacy of the sample size, a power analysis was performed using G*Power software (Faul et al., 2007), assuming “a statistical power of 80%, a significance level of 5%, and a medium effect size of 0.15” (Cohen, 2013). This analysis indicated that a minimum of 77 cases was required, confirming that the obtained sample of 215 responses was more than sufficient. The participants’ characteristics are summarized in Table 2.

Measures

As previously noted, this study employed a survey as the primary data collection instrument. The survey items were adapted from prior research. Participants’ answers were measured on a 5-point Likert scale, where 1 denoted “strongly disagree” and 5 denoted “strongly agree”, for each variable.

Ethical leadership

A scale with 10 items was used to evaluate the six components of an EL measure developed by Brown et al. (2005), which include “treating employees fairly, listening, concern, trust, modeling conduct, and communication response”. A sample of the items is, “My leader listens to what employees have to say.”

Green HRM

The six-item GHRM scale developed by Dumont et al. (2017) and Al-Swidi et al. (2024) was used. Items that were redundant, unclear, or not relevant to the Qatari context were excluded, leaving questions such as “My organization sets green goals for its employees”.

Organizational attractiveness

It was measured with 5-items used by Guillot-Soulez et al. (2022), with questions such as “For me, this company is a good place to work”. Since this study seeks to measure OA based on the perspective of current employees, the scale was suitably modified to reflect the study’s content while retaining the scale’s meaning.

Job satisfaction

The 4-items scale developed by Ahmad and Umrani (2019) was used to measure JS, with questions such as “All in all, I am very satisfied with my current job”.

Common method bias

To evaluate the potential for common method bias (CMB), Harman’s single-factor test was employed. Following the Podsakoff et al. (2012) threshold of 50%, CMB was not an issue in the data, as the variance explained by a single factor was 47%. Furthermore, Fuller et al. (2016) proposed assessing CMB by examining collinearity through the variance inflation factor (VIF) in SmartPLS. In line with their recommendation, the analysis showed that all VIF values were below the threshold of 3, indicating that CMB is not an issue in this dataset.

Data analysis technique

After collecting the data through the questionnaire, it was processed with SPSS version 25 and Smart PLS version 4. Since the main goal of the study was to anticipate the correlations, the data were essentially analyzed using “the partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM)” approach (Ringle et al., 2015). This method was chosen over covariance-based alternatives such as AMOS or MPLUS because it is particularly suitable for predictive and exploratory research, performs well with relatively small sample sizes, and does not require data normality assumptions (Chin et al., 2003). Moreover, PLS-SEM provides greater statistical power and flexibility for testing complex models with multiple mediators, aligning with the study’s objectives (Al-Swidi et al., 2025; Hair et al., 2014; Henseler, 2018).

To ensure the robustness of the model, several criteria were applied, including assessments of model fit using “the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR), explanatory power (R²), effect sizes (f²), predictive relevance (Q²), and the stability of path coefficients through bootstrapping”.

Results

Prior to conducting the analysis, the dataset was prepared through outlier detection and missing value imputation. Normality was then assessed using SPSS, and the data met all required assumptions. Following this, we applied the recommended PLS-SEM approach to evaluate the data and test our hypotheses in two stages. First, the measurement model was examined, after which the structural model was analyzed to validate the proposed theories and assess their predictive ability.

Measurement model analysis

To evaluate the measurement model, we examined internal consistency, convergent and discriminant validity. In line with Hair et al. (2019), a reliability threshold of 0.70 was used for indicator loadings. The results in Table 3 confirm convergent validity, as evidenced by factor loadings and composite reliability above 0.70, and an AVE greater than 0.50.

Moreover, the discriminant validity was evaluated utilizing “the Heterotrait-Monotrait (HTMT) ratio”, following the recommendations of Henseler et al. (2015). HTMT values below 0.85 indicate that the constructs are empirically distinct, ensuring that every construct measures a unique concept (Kline, 2011). As shown in Table 4, all HTMT values less than the threshold of 0.85, demonstrating sufficient discriminant validity.

Structural model analysis

Before looking into the proposed links in the structural model, the SRMR in SEM-PLS was calculated to assess overall model fit. To guarantee an accurate model fit, the SRMR value should be less than 0.08, as advised by Henseler et al. (2015). As per the findings, the SRMR value was 0.051, indicating a good degree of fit (Hu and Bentler, 1999).

Next, we examined the proposed links and assessed the model’s explanatory strength (R²), which accounted for 23.9% of the variance in GHRM, 38.8% in JS, and 61.1% of the variance in OA, aligning with Chin’s (1998) prediction standards “0.10 = weak; 0.33 = moderate; 0.67 = strong”. Furthermore, the effect size (f2) of every predictor was determined according to Cohen (2013), with three levels “0.02= small, 0.15=medium, and 0.35= large”. For instance, the effect sizes of EL were high for GHRM 0.313 and JS 0.362, while the effect size of EL was small for OA 0.042 (see Table 5). Additionally, predictive relevance (Q²) was assessed using Stone-Geisser’s test. The Q2 values for the endogenous constructs were 0.202 for GHRM, 0.324 for JS, and 0.451 for OA, all of which exceed zero, indicating adequate predictive power (Hair et al., 2019).

A bootstrapping analysis with 5000 resamples was used to validate the path estimates, confirming the statistical significance of the hypothesized correlations. As per Table 6, the path from EL to OA was positive and significant (β = 0.21, 95% confidence intervals [0.08, 0.34]), indicating that higher EL is associated with greater OA. EL also had a positive and significant effect on GHRM (β = 0.56, 95% confidence intervals [0.44, 0.68]) and a positive and significant effect on JS (β = 0.47, 95% confidence intervals [0.33, 0.61]). GHRM was significantly associated with OA (β = 0.29, 95% confidence intervals [0.15, 0.42]) and with JS (β = 0.35, 95% CI [0.20, 0.49]). Furthermore, JS demonstrated a positive relationship with OA (β = 0.38, 95% confidence intervals [0.25, 0.51]). Therefore, hypotheses H1, H2a, H2b, H3a, H3b, and H4 are supported.

Mediation analysis

Using the bootstrapping method, the indirect effects were calculated, as per Preacher and Hayes’s (2008) approach. Hair et al. (2014) suggest employing PLS-SEM bootstrapping processes for mediation analysis as a more reliable method than the traditional “causal procedure” advocated by Baron and Kenny (1986). In order to examine the mediation, they recommend that researchers bootstrap the sampling distribution of the indirect influence, as recommended by Preacher and Hayes (2008). Indeed, SEM makes it possible to evaluate the effects of several factors simultaneously (Preacher and Hayes, 2008).

The results of mediation tests in Table 7 further confirmed that GHRM partially mediated the EL–OA link (indirect effect: β = 0.16, 95% confidence intervals [0.08, 0.25]) and that JS also partially mediated this relationship (indirect effect: β = 0.18, 95% confidence intervals [0.09, 0.27]). Therefore, H2c and H3c are supported. Notably, the sequential mediation of GHRM and JS between EL and OA was significant (indirect effect: β = 0.11, 95% confidence intervals [0.05, 0.19]). Therefore, H2c and H3c are supported. Moreover, there is sequential mediation of GHRM and JS between EL and OA. Thus, H5 is supported.

Discussion

Based on SET and SVFT, this work examines the link between EL, GHRM, JS, and OA. By employing an empirical approach, the current findings add to the body of knowledge while also generating theoretical and practical consequences and opening up new avenues for future research. The findings are explained in more detail below.

According to the results, EL has a significant positive impact on OA for current employees. This result is consistent with Brown and Treviño (2006) and Benevene et al. (2018), who indicated that EL plays a crucial role in shaping positive organizational values and enhancing OA to potential and current employees. Ethical leaders model behaviors such as fairness, integrity, and transparency, which contribute to a work environment perceived as morally sound and trustworthy. This, in turn, enhances the organization’s attractiveness to its employees.

The findings also demonstrate that EL drives the implementation of GHRM practices. This finding aligns with prior studies, such as those by Islam et al. (2021a, b), which linked EL to sustainability-driven HR practices. Ethical leaders prioritize sustainability goals and influence HR policies to encourage eco-friendly behaviors among employees. In addition, the positive link between GHRM and OA was confirmed. These findings support earlier research, such as Renwick et al. (2013), which highlighted the role of GHRM initiatives in fostering positive employee attitudes. Consistent with previous studies (Aboramadan, 2022; Ababneh, 2021; Merlin and Chen, 2022), the results suggest that GHRM practices, such as providing training, adequate compensation, awareness, and suggestions regarding green behavior, assist organizations in cultivating a green workforce while motivating employees to adopt and advocate environmentally sustainable practices. When organizations prioritize green initiatives, they not only attract talent that values sustainability but also foster a more committed workforce that actively participates in ecological efforts, leading to a more sustainable and attractive organizational environment for their current workforce (Umrani et al., 2022). More importantly, GHRM partially mediates EL’s effect on OA. Specifically, GHRM practices serve as a positive channel through which EL fosters OA, indicating that environmentally focused HR policies and initiatives create a positive image of employees toward their organization. GHRM practices help create a sense of alignment between employee values and organizational goals, which enhances loyalty and OA.

Additionally, EL was shown to positively influence JS. Ethical leaders create a supportive and fair work environment, leading to higher levels of JS (Aftab et al., 2023). This finding corroborates earlier studies by Freire and Bettencourt (2020) and Yasir and Javed (2024), which linked EL to JS. Moreover, this result highlights the crucial role of JS in shaping how employees perceive their organization. When employees feel satisfied with their roles, work environment, and overall experience within the company, they are more likely to see the company as an attractive place to work. Satisfied employees are more likely to view their organization positively and advocate for its attractiveness. This result can be seen in consonance with the studies (Najm et al., 2023), which showed a significant link between employee satisfaction and the organization’s reputation as a desirable place to work. As such, the results show that there is an indirect effect of EL on OA via JS. Specifically, JS serves as a partial mediator in the EL-OA link.

Furthermore, a correlation was found between GHRM and JS. This is consistent with the findings of Abdelhamied et al. (2023) and Vadithe et al. (2025), who found a significant relationship between GHRM practices and JS. This finding implies that GHRM not only contributes to environmental goals or corporate social responsibility efforts, it also directly influences how employees perceive their work environment or overall JS. Finally, and more importantly, the study confirms the sequential mediation effect of GHRM and JS in the EL-OA relationship. This sequential pathway can be theoretically explained by integrating SET and SVFT. Ethical leaders, by treating employees fairly and transparently, cultivate reciprocal trust (SET), which motivates employees to engage with green initiatives. When such GHRM practices are adopted, they signal alignment between organizational and individual values (SVFT), thereby enhancing employees’ sense of purpose and satisfaction with their jobs. In turn, satisfied employees are more likely to view their organization as attractive, both as a place to work and as an employer brand. Thus, the sequential mediation result underscores that EL does not influence OA in isolation, but rather through a process in which green practices and satisfaction mutually reinforce one another, ultimately shaping employees’ perceptions of OA. Overall, these results not only align with existing literature but also extend our understanding by focusing on current employees in the public sector of Qatar, a relatively underexplored context

Theoretical implications

This work contributes to the literature on EL, GHRM, JS, and OA in many ways. First, by focusing on the perceptions of current employees, this study addresses a notable gap in prior research on OA, which has largely focused on potential employees (e.g., Huang, 2022; Younis and Hammad, 2021). Understanding how current employees perceive OA provides critical insights into retention strategies and internal branding (Bayraktaroglu et al., 2023), enriching the existing body of knowledge (Benevene et al., 2018). Our findings highlight the importance of examining OA from the perspective of current employees, emphasizing that theories designed for potential employees may not fully align with internal organizational contexts, and vice versa. For instance, previous studies on external hiring indicate that potential employees often face challenges in assessing implicit organizational characteristics, such as leadership, organizational climate, or culture, before being hired (Cable et al., 2000). This assumption is at odds with our results, as current employees are likely to possess specific and often more accurate information about job and workplace environments. Consequently, they may assess the same opportunities in a manner that differs significantly from potential employees (McCarthy and Keller, 2022).

Second, while the leadership-OA relationship has garnered scholarly attention (Atalay et al., 2019), no study, to our knowledge, has specifically examined the link between EL and OA from the perspective of current employees. Meanwhile, the study reveals that GHRM and JS are crucial mediating variables in the EL-OA relationship, highlighting the interconnected pathways through which EL indirectly influences OA and emphasizing the complex interplay between leadership behaviors and HR practices. Third, this study contributes to EL and HRM literature by demonstrating how EL drives the implementation of GHRM to enhance OA. It bridges the gap between leadership behaviors and sustainability-focused HR practices, emphasizing the mediating role of GHRM as a mechanism through which EL creates positive employee perceptions of their organization as an attractive workplace. Fourth, this study contributes to theoretical understanding by integrating multiple theoretical perspectives, including SET and SVFT, providing a robust framework for understanding the dynamics between leadership, HR practices, and employee perceptions. Finally, the study’s contextual focus on the public sector in Qatar expands the scope of EL and OA research to a developing country setting, shedding light on how cultural and institutional factors shape these dynamics and addressing gaps highlighted by Nguyen et al. (2023).

Practical implications

The findings of this study offer valuable insights for organizations aiming to enhance environmental responsibility, JS, and overall OA. First, the significant effect of EL underscores the need for organizations to prioritize the development of ethical leaders by implementing training programs that emphasize trust, transparency, and fairness. These qualities are pivotal in shaping employee perceptions of attractiveness and fostering a positive organizational culture (Neubert et al., 2009). For instance, organizations can design structured leadership development workshops that train managers in ethical decision-making and sustainable leadership behaviors, thereby embedding ethical values in day-to-day operations. Leaders can also initiate transparent communication forums and feedback mechanisms, ensuring fairness and inclusivity in decision-making, which directly fosters employees’ trust and satisfaction. To achieve this, organizational leaders and HR managers must work hand in hand with policymakers, professional bodies, and training providers to create enabling environments for such programs. Policymakers can incentivize organizations by linking recognition or funding opportunities to demonstrated progress in sustainable HRM practices. Meanwhile, cross-sector partnerships with universities or NGOs can strengthen training content and provide external benchmarking. This multi-stakeholder collaboration ensures that initiatives are not only designed but also sustained over time.

Second, since JS significantly influences OA, organizations must focus on designing meaningful work environments, providing growth opportunities, and addressing employee concerns to retain talent and enhance their OA. Practically, this can be achieved by linking employee performance appraisals with sustainability outcomes, introducing reward systems for eco-friendly behaviors, and offering professional development programs tailored to employees’ career goals. By making work purposeful and aligned with employee values, organizations strengthen their attractiveness and ability to retain talent.

Third, the findings highlight that public institutions in Qatar, in particular, can benefit from embedding EL and GHRM practices into policy frameworks, aligning with the Qatar National Vision 2030. For example, civil service codes of conduct could include EL standards emphasizing fairness, integrity, and sustainability, while HR policies could integrate mandatory sustainability-focused performance indicators. Policymakers may also introduce national-level incentives for public sector organizations that actively implement GHRM initiatives, such as green recruitment, training, and employee participation in environmental projects. These procedures not only reinforce Qatar’s national sustainability agenda but also strengthen the role of public organizations as ethical and socially responsible employers, enhancing their OA in a highly competitive labor market.

Finally, recognizing workforce diversity is crucial. Employees’ values and expectations may vary across demographic, cultural, and generational groups. Tailored HR strategies that respect these differences, such as offering flexible green initiatives or role-specific sustainability training, can maximize engagement and satisfaction, ultimately strengthening the organization’s internal culture and attractiveness.

While broad recommendations are valuable, certain aspects require particular attention. For instance, leadership behaviors must be directly aligned with organizational sustainability goals to avoid symbolic implementation. Additionally, inclusivity should remain central, ensuring that all employees, not only those in managerial roles, are engaged in sustainability and ethical initiatives. Lastly, organizations should adopt transparent monitoring mechanisms to track progress and adjust initiatives as needed.

Limitations and future research

While this study offers promising results and addresses significant gaps, it also presents certain limitations that future researchers should consider. First, the reliance on a convenience sampling strategy constitutes a limitation, as it may restrict the generalizability of the findings across all Qatari public sector employees or other contexts. Although some procedures were taken to mitigate this limitation partially, such as seeking expert validation of the questionnaire, conducting pilot testing, and securing a sufficiently large sample size to ensure acceptable reliability and validity of the measures, future research, however, should employ probability-based sampling approaches to enhance representativeness and robustness. Second, the cultural context of Qatar, which is characterized by relatively high power distance, should be acknowledged as a factor shaping the dynamics of EL and JS. In hierarchical environments, employees may rely more heavily on leaders’ behaviors to interpret organizational values and fairness, which could amplify the influence of EL on OA. Therefore, future research can explore how cultural dimensions such as power distance, collectivism, or uncertainty avoidance interact with leadership and HRM practices in shaping employees’ perceptions. Third, while this study focused on GHRM and JS as mediators, future research could benefit from exploring other explanatory mechanisms. Constructs such as organizational justice, employee empowerment, or voice behavior may serve as mediators or moderators that enrich understanding of how EL affects OA. These variables could provide deeper insights into the psychological and behavioral processes through which leadership and sustainability practices translate into positive organizational outcomes. Finally, although measures like Harman’s single-factor test were used, reliance on self-reported data may still raise the risk of CMB. Future research may address this by combining surveys with objective performance indicators or longitudinal designs to validate causal pathways. Extending research to include private sector organizations and diverse cultural contexts would also allow for broader generalization of the findings, providing a more comprehensive understanding of the interplay between EL, GHRM, and OA. This approach will contribute to generating robust and comprehensive findings, as management practices and their associated outcomes differ significantly across companies, sectors, and geographic regions (Bloom and Van Reenen, 2010).

Data availability

The data used in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

References

Ababneh OMA (2021) How do green HRM practices affect employees’ green behaviors? The role of employee engagement and personality attributes. J Environ Plan Manag 64(7):1204–1226. https://doi.org/10.1080/09640568.2020.1814708

Abdelhamied HH, Elbaz AM, Al-Romeedy BS, Amer TM (2023) Linking green human resource practices and sustainable performance: the mediating role of job satisfaction and green motivation. Sustainability 15(6):4835. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15064835

Aboramadan M (2022) The effect of green HRM on employee green behaviors in higher education: the mediating mechanism of green work engagement. Int J Organ Anal 30(1):7–23. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOA-05-2020-2190

Aftab J, Sarwar H, Kiran A, Qureshi MI, Ishaq MI, Ambreen S, Kayani AJ (2023) Ethical leadership, workplace spirituality, and job satisfaction: moderating role of self-efficacy. Int J Emerg Mark 18(12):5880–5899. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOEM-07-2021-1121

Ahmad I, Umrani WA (2019) The impact of ethical leadership style on job satisfaction: mediating role of perception of Green HRM and psychological safety. Leadersh Organ Dev J 40(5):534–547. https://doi.org/10.1108/LODJ-12-2018-0461

Ahmad I, Ullah K, Khan A (2022) The impact of green HRM on green creativity: mediating role of pro-environmental behaviors and moderating role of ethical leadership style. Int J Hum Resour Manag 33(19):3789–3821. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2021.1931938

Ahmad I, Donia MB, Khan A, Waris M (2019) Do as I say and do as I do? The mediating role of psychological contract fulfillment in the relationship between ethical leadership and employee extra-role performance. Pers Rev 48(1):98–117. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-12-2016-0325

Ahmad KZ, Tabche I, Behery M (2025a) The interplay between person-environment fit, empowerment and job satisfaction: a moderation effect of leader-member-exchange. Int J Organ Anal 33(4):807–828. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOA-10-2023-4011

Ahmad S, Islam T, Kaleem A (2025b) The power of playful work design in the hospitality industry: mapping the implications for employee engagement, taking charge and the moderation of contrived fun. Int J Hosp Manag 128: 104154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2025.104154

Ahmad S, Islam T, Sadiq M, Kaleem A (2021) Promoting green behavior through ethical leadership: a model of green human resource management and environmental knowledge. Leadersh Organ Dev J 42(4):531–547. https://doi.org/10.1108/LODJ-01-2020-0024

Al-Sabi SM, Al-Ababneh MM, Al Qsssem AH, Afaneh JAA, Elshaer IA (2024) Green human resource management practices and environmental performance: the mediating role of job satisfaction and pro-environmental behavior. Cogent Bus Manag 11(1):2328316. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2024.2328316

Al-Swidi AK, Gelaidan HM, Saleh RM (2021) The joint impact of green human resource management, leadership and organizational culture on employees’ green behaviour and organisational environmental performance. J Clean Prod 316: 128112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.128112

Al-Swidi AK, Al-Hakimi MA, Al-Hattami HM (2024) Fostering environmental preservation: exploring the synergy of green human resource management and corporate environmental ethics. Bottom Line 37(1):1–26. https://doi.org/10.1108/BL-06-2023-0191

Al-Swidi AK, Al-Hakimi MA, Gelaidan HM, Al-Temimi SKA (2022) How does consumer pressure affect green innovation of manufacturing SMEs in the presence of green human resource management and green values? A moderated mediation analysis. Bus Ethics, Environ Responsib 31(4):1157–1173. https://doi.org/10.1111/beer.12459

Al-Swidi AK, Al-Hakimi MA, Gelaidan HM, Al-Haifi MM, Ahmed AA (2025) Harnessing digital technologies in circular supply chains: the role of technological opportunism capability and technological turbulence. Sustain Futures 9: 100492. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sftr.2025.100492

Apolinario S, Yoshikuni AC, Larieira CLC (2023) Resistance to information security due to users’ information safety behaviors: empirical research on the emerging markets. Comput Hum Behav 145: 107772. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2023.107772

Atalay D, Akçıl U, Özkul AE (2019) Effects of transformational and instructional leadership on organizational silence and attractiveness and their importance for the sustainability of educational institutions. Sustainability 11(20):5618. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11205618

Baron RM, Kenny DA (1986) The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Personal Soc Psychol 51(6):1173–1182

Bayraktaroglu S, Chew YTE, Atay E, Aras M (2023) A moderated moderation effects of employer branding and religiosity on the relationship of affective commitment and quit intention. Empl Responsib Rights J 35(4):519–539. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10672-022-09426-1

Benevene P, Dal Corso L, De-Carlo A, Falco A, Carluccio F, Vecina ML (2018) Ethical leadership as antecedent of job satisfaction, affective organizational commitment and intention to stay among volunteers of non-profit organizations. Front Psychol 9:1–17. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02069

Berthon P, Ewing M, Hah LL (2005) Captivating company: dimensions of attractiveness in employer branding. Int J Advert 24(2):151–172. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2005.11072912

Blair CA, Helland K, Walton B (2017) Leaders behaving badly: the relationship between narcissism and unethical leadership. Leadersh Organ Dev J 38(2):333–346. https://doi.org/10.1108/LODJ-09-2015-0209

Blok V, Wesselink R, Studynka O, Kemp R (2015) Encouraging sustainability in the workplace: a survey on the pro-environmental behaviour of university employees. J Clean Prod 106:55–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2014.07.063

Bloom N, Van Reenen J (2010) Why do management practices differ across firms and countries?. J Econ Perspect 24(1):203–224. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.24.1.203

Brown ME, Treviño LK (2006) Ethical leadership: a review and future directions. Leadersh Q 17(6):595–616. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2006.10.004

Brown ME, Treviño LK, Harrison DA (2005) Ethical leadership: a social learning perspective for construct development and testing. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process 97:117–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2005.03.002

Cable DM, Aiman-Smith L, Mulvey PW, Edwards JR (2000) The sources and accuracy of job applicants’ beliefs about organizational culture. Acad Manag J 43(6):1076–1085. https://doi.org/10.5465/1556336

Chin WW (1998) The partial least squares approach to structural equation modeling. Mod methods Bus Res 295(2):295–336

Chin WW, Marcolin BL, Newsted PR (2003) A partial least squares latent variable modeling approach for measuring interaction effects: results from a Monte Carlo simulation study and an electronic-mail emotion/adoption study. Inf Syst Res 14(2):189–217. https://doi.org/10.1287/isre.14.2.189.16018

Cohen A, Liu Y (2011) Relationships between in-role performance and individual values, commitment, and organizational citizenship behavior among Israeli teachers. Int J Psychol 46(4):271–287. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207594.2010.539613

Cohen J (2013) Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Routledge

Cropanzano R, Mitchell MS (2005) Social exchange theory: an interdisciplinary review. J Manag 31(6):874–900. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206305279602

Dassler A, Khapova SN, Lysova EI, Korotov K (2022) Employer attractiveness from an employee perspective: a systematic literature review. Front Psychol 13:1–16. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.858217

Dey M, Bhattacharjee S, Mahmood M, Uddin MA, Biswas SR (2022) Ethical leadership for better sustainable performance: role of employee values, behavior and ethical climate. J Clean Prod 337:130527. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.130527

Dua AK, Farooq A, Rai S (2023) Ethical leadership and its influence on employee voice behavior: role of demographic variables. Int J Ethics Syst 39(2):213–235. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOES-10-2021-0200

Dumont J, Shen J, Deng X (2017) Effects of green HRM practices on employee workplace green behavior: the role of psychological green climate and employee green values. Hum Resour Manag 56(4):613–627. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.21792

Edwards JR (1996) An examination of competing versions of the person-environment fit approach to stress. Acad Manag J 39(2):292–339. https://doi.org/10.5465/256782

ElGammal W, El-Kassar AN, Canaan Messarra L (2018) Corporate ethics, governance and social responsibility in MENA countries. Manag Decis 56(1):273–291. https://doi.org/10.1108/MD-03-2017-0287

Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang AG, Buchner A (2007) G* Power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res methods 39(2):175–191

Freire C, Bettencourt C (2020) Impact of ethical leadership on job satisfaction: the mediating effect of work–family conflict. Leadersh Organ Dev J 41(2):319–330. https://doi.org/10.1108/LODJ-07-2019-0338

Fuller CM, Simmering MJ, Atinc G, Atinc Y, Babin BJ (2016) Common methods variance detection in business research. J Bus Res 69:3192–3198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.12.008

Gelaidan HM, Al-Swidi AK, Al-Hakimi MA (2024) Servant and authentic leadership as drivers of innovative work behaviour: the moderating role of creative self-efficacy. Eur J Innov Manag 27(6):1938–1966. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJIM-07-2022-0382

Guillot-Soulez C, Saint-Onge S, Soulez S (2022) Green certification and organizational attractiveness: the moderating role of firm ownership. Corp Soc Responsib Environ Manag 29(1):189–199. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.2194

Haddock-Millar J, Sanyal C, Müller-Camen M (2016) Green human resource management: a comparative qualitative case study of a United States multinational corporation. Int J Hum Resour Manag 27(2):192–211. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2015.1052087

Hair JF, Sarstedt M, Hopkins L, Kuppelwieser VG (2014) Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM): an emerging tool in business research. Eur Bus Rev 26(2):106–121. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-10-2013-0128

Hair JF, Risher JJ, Sarstedt M, Ringle CM (2019) When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur Bus Rev 31(1):2–24

Hair, JF, Bush, RP, and Ortinau, DJ (2003). Marketing research: within a changing information environment. McGraw-Hill, Boston

Henseler J (2018) Partial least squares path modeling: Quo vadis?. Qual Quant 52(1):1–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-018-0689-6

Henseler J, Ringle CM, Sarstedt M (2015) A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J Acad Mark Sci 43(1):115–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8

Hosseini E, Ferreira JJ (2023) The impact of ethical leadership on organizational identity in digital startups: does employee voice matter?. Asian J Bus Ethics 12(2):369–393. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13520-023-00178-1

Hu LT, Bentler PM (1999) Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Model A Multidiscip J 6(1):1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

Huang JC (2022) Effects of person-organization fit objective feedback and subjective perception on organizational attractiveness in online recruitment. Pers Rev 51(4):1262–1276. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-06-2020-0449

Islam T, Hussain D, Ahmed I, Sadiq M (2021b) Ethical leadership and environment specific discretionary behaviour: the mediating role of green human resource management and moderating role of individual green values. Can J Adm Sci/Rev Can Sci Adm 38(4):442–459. https://doi.org/10.1002/cjas.1637

Islam T, Khan MM, Ahmed I, Mahmood K (2021a) Promoting in-role and extra-role green behavior through ethical leadership: mediating role of green HRM and moderating role of individual green values. Int J Manpow 42(6):1102–1123. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJM-01-2020-0036

Joplin T, Greenbaum RL, Wallace JC, Edwards BD (2021) Employee entitlement, engagement, and performance: the moderating effect of ethical leadership. J Bus Ethics 168(4):813–826. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-019-04246-0

Kalińska-Kula M, Staniec I (2021) Employer branding and organizational attractiveness: current employees’ perspective. Eur Res Stud J 24(1):583–603. https://www.um.edu.mt/library/oar/handle/123456789/80372

Kline RB (2011) Convergence of structural equation modeling and multilevel modeling. In: The SAGE handbook of innovation in social research methods. SAGE. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446268261.n31

Kramar R (2014) Beyond strategic human resource management: is sustainable human resource management the next approach?. The International Journal of Human Resource Management 25(8):1069–1089. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2013.816863

Landers RN, Behrend TS (2015) An inconvenient truth: arbitrary distinctions between organizational, Mechanical Turk, and other convenience samples. Ind Organ Psychol 8(2):142–164. https://doi.org/10.1017/iop.2015.13

Leroy H, Segers J, Van Dierendonck D, Den-Hartog D (2018) Managing people in organizations: integrating the study of HRM and leadership. Hum Resour Manag Rev 28(3):249–257. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2018.02.002

Lin CP, Liu ML (2017) Examining the effects of corporate social responsibility and ethical leadership on turnover intention. Pers Rev 46(3):526–550. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-11-2015-0293

Locke EA (1976) The nature and causes of job satisfaction. In: Donnette MD (ed) Handbook of industrial and organizational psychology. Rand McNally, Chicago, IL, pp 1297–1343

McCarthy JE, Keller JR (2022) How managerial openness to voice shapes internal attraction: evidence from United States school systems. ILR Rev 75(4):1001–1023. https://doi.org/10.1177/00197939211008877

Mehta R, Rice S, Winter S, Spence T, Edwards M, Candelaria-Oquendo K (2019) Generalizability of effect sizes within aviation research: more samples are needed. Int J Aviat Aeronaut Aerosp 6(5):1–19. https://doi.org/10.15394/ijaaa.2019.1404

Merlin ML, Chen Y (2022) Impact of green human resource management on organizational reputation and attractiveness: the mediated-moderated model. Front Environ Sci 10:1–16. https://doi.org/10.3389/fenvs.2022.962531

Möbert A, Masling A, Kastenmüller A (2025) Why and when ethical leadership signals enhance employer attractiveness: a moderated mediation model. J Pers Psychol 24(3):160–171. https://doi.org/10.1027/1866-5888/a000367

Moin MF, Omar MK, Wei F, Rasheed MI, Hameed Z (2021) Green HRM and psychological safety: How transformational leadership drives follower’s job satisfaction. Curr issues Tour 24(16):2269–2277. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2020.1829569

Najm NA, Alhmeidiyeen MS, Abuyassin NA, Al-Nasour JA (2023) Project management ethics and corporate reputation: the mediating role of employee satisfaction. Int J Prod Qual Manag 39(3):409–429. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJPQM.2023.132267

Neubert MJ, Carlson DS, Kacmar KM, Roberts JA, Chonko LB (2009) The virtuous influence of ethical leadership behavior: evidence from the field. J Bus ethics 90:157–170. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-009-0037-9

Nguyen TD, Nguyen TT, Nguyen PC (2023) Job embeddedness and turnover intention in the public sector: the role of life satisfaction and ethical leadership. Int J Public Sect Manag 36(4/5):463–479. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPSM-03-2023-0070

Ogunfowora B (2014) The impact of ethical leadership within the recruitment context: the roles of organizational reputation, applicant personality, and value congruence. Leadersh Q 25(3):528–543. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2013.11.013

Pandita D, Ray S (2018) Talent management and employee engagement—a meta-analysis of their impact on talent retention. Ind Commer Train 50(4):185–199. https://doi.org/10.1108/ICT-09-2017-0073

Pinzone M, Guerci M, Lettieri E, Huisingh D (2019) Effects of ‘green’training on pro-environmental behaviors and job satisfaction: evidence from the Italian healthcare sector. J Clean Prod 226:221–232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.04.048

Pletz V, Tiberius V, Meyer N (2024) Ethical leadership: a bibliometric review and research framework with methodological implications. Bus Ethics Environ Responsib 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1111/beer.12754

Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Podsakoff NP (2012) Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annu Rev Psychol 63:539–569

Preacher KJ, Hayes AF (2008) Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav Res methods 40(3):879–891

Rahaman HS, Camps J, Decoster S, Stouten J (2021) Ethical leadership in times of change: the role of change commitment and change information for employees’ dysfunctional resistance. Pers Rev 50(2):630–647. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-03-2019-0122

Reis GG, Braga BM, Trullen J (2017) Workplace authenticity as an attribute of employer attractiveness. Pers Rev 46(8):1962–1976. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-07-2016-0156

Renwick DWS, Redman T, Maguire S (2013) Green human resource management: a review and research agenda. Int J Manag Rev 15(1):1–14. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2370.2011.00328.x

Ringle CM, Wende S, Becker JM (2015) SmartPLS 3. SmartPLS GmbH, Boenningstedt. J Serv Sci Manag 10(3):32–49

Saeed BB, Afsar B, Hafeez S, Khan I, Tahir M, Afridi MA (2019) Promoting employee’s proenvironmental behavior through green human resource management practices. Corp Soc Responsib Environ Manag 26(2):424–438. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.1694

Shafique I, Ahmad B, Kalyar MN (2020) How ethical leadership influences creativity and organizational innovation: Examining the underlying mechanisms. Eur J Innov Manag 23(1):114–133. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJIM-12-2018-0269

Smith AK, Bolton RN, Wagner J (1999) A model of customer satisfaction with service encounters involving failure and recovery. J Mark Res 36(3):356–372. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224379903600305

Staniec I, Kalińska-Kula M (2021) Internal employer branding as a way to improve employee engagement. Probl Perspect Manag 19(3):33–45. https://doi.org/10.21511/ppm.19(3).2021.04

Strobel M, Tumasjan A, Welpe I (2015) Do business ethics pay off?. J Psychol 218(4):213–224. https://doi.org/10.1027/0044-3409/a000031

Sypniewska B, Baran M, Kłos M (2023) Work engagement and employee satisfaction in the practice of sustainable human resource management–based on the study of Polish employees. Int Entrep Manag J 19(3):1069–1100. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-023-00834-9

Teddlie C, Yu F (2007) Mixed methods sampling: a typology with examples. J Mixed Methods Res 1(1):77–100. https://doi.org/10.1177/1558689806292430

Ullah I, Mirza B, Hameed RM (2022) Understanding the dynamic nexus between ethical leadership and employees’ innovative performance: the intermediating mechanism of social capital. Asian J Bus Ethics 11(1):45–65. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13520-022-00141-6

Umrani WA, Channa NA, Ahmed U, Syed J, Pahi MH, Ramayah T (2022) The laws of attraction: role of green human resources, culture and environmental performance in the hospitality sector. Int J Hosp Manag 103:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2022.103222

Vadithe RN, Rajput RC, Kesari B (2025) Impact of green HRM implementation on organizational sustainability in IT sector: a mediation analysis. Sustain Futures 9: 100507. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sftr.2025.100507

Vermeeren B, Kuipers B, Steijn B (2014) Does leadership style make a difference? Linking HRM, job satisfaction, and organizational performance. Rev Public Pers Adm 34(2):174–195. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734371X13510853

Vokić NP, Verčič AT, Ćorić DS (2022) Strategic internal communication for effective internal employer branding. Balt J Manag 18(1):19–33. https://doi.org/10.1108/BJM-02-2022-0070

Walumbwa FO, Hartnell CA, Misati E (2017) Does ethical leadership enhance group learning behavior? Examining the mediating influence of group ethical conduct, justice climate, and peer justice. J Bus Res 72:14–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.11.013

Watson C, McCarthy J, Rowley J (2013) Consumer attitudes towards mobile marketing in the smart phone era. Int J Inf Manag 33(5):840–849. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2013.06.004

Xie J, Bhutta ZM, Li D, Andleeb N (2023) Green HRM practices for encouraging pro-environmental behavior among employees: the mediating influence of job satisfaction. Environ Sci Pollut Res 30(47):103620–103639. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-023-29362-3

Yasir M, Javed A (2024) Ethical leadership, employees’ job satisfaction and job stress in the restaurant industry. foresight 26(5):886–901. https://doi.org/10.1108/FS-03-2023-0038

Younis RAA, Hammad R (2021) Employer image, corporate image and organizational attractiveness: the moderating role of social identity consciousness. Pers Rev 50(1):244–263. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-02-2019-0058

Zhou B, Zhang S (2025) How does green psychological climate improve voluntary workplace green behavior? A moderated mediation model centered on green satisfaction. J Environ Manag 373: 123925. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2024.123925

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AMA and AKA conceptualized. AMA collected data. AKA and MAA analyzed data. All authors wrote and reviewed the main manuscript. ISA provided the resources. ISA and MAA revised the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study received ethical approval from the Ethics Committee of the School of Economics, Administration and Public Policy, Doha Institute for Graduate Studies, Doha, Qatar, at its meeting held on December 1, 2023 (Approval number: SEAPP/DI1892023), following a thorough review of the research proposal and questionnaire items, ensuring that ethical guidelines are followed for research involving human subjects.

Informed consent

Participants received written informed consent forms explaining the purpose of the study, along with their rights and responsibilities. As the data was gathered via a survey between January and March 2024, this process functioned as written consent. They were clearly informed about the anonymity of their responses, how their data would be used, and any potential risks involved. It was also made clear that their participation was completely voluntary and that they could withdraw at any point without facing any consequences.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Al-Swidi, A.K., Al-Hakimi, M.A., Almaweri, A.M. et al. Ethical leadership and organizational attractiveness: the sequential role of green HRM and job satisfaction among public sector employees. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 13, 121 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-06429-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-06429-9