Abstract

While global welfare debates prioritize recipient empowerment, existing studies have stated controversial opinions regarding whether and how could social assistance shape recipients’ prosocial behaviors—a critical gap given rising inequality. From the theoretical perspective of institutional logics, this study examines how different forms of social assistance impact recipients’ philanthropic behaviors, and examines China’s unique state-society dynamics to reveal how authoritarian governance impacts institutional logics. Using nationally representative data, the results of analyses show that state assistance strengthens the constraints of economic conditions on individual giving, and charitable assistance has no effect overall, while mixed assistance weakens the positive effect of self-efficacy and perceived reciprocity. The findings redefine empowerment debates by highlighting institutional hierarchy’s role considering unbalanced state-society relation. These insights advance comparative welfare literature and offer actionable pathways for coordinating state-NGO efforts of social assistance in authoritarian contexts in order to promote the full development of recipients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The World Bank’s shared prosperity agenda links economic development to the elevation of the poorest and the reduction of multidimensional inequalities. Social assistance is fundamental to this aim, functioning both as a safety net that protects vulnerable groups and as a catalyst for empowerment and long-term self-sufficiency, which helps narrow income gaps (Villamil et al. 2021). Therefore, realizing this vision requires looking beyond material support to address the very fabric of society. Ultimately, advancing shared prosperity depends not only on the level of assistance provided but also on empowering recipients to become agents of philanthropic spirit and action.

However, existing research has predominantly focused on tapping the potential of existing donors and aid providers, such as corporations and high-status groups including celebrities, while largely overlooking the philanthropic behaviors of recipients (e.g., Bekkers and Wiepking 2011). Although targeting affluent donors is often justified by resource scarcity, neglecting the prosociality of recipients perpetuates exclusion and undermines social cohesion. Empirical evidence indicates that participation in giving by marginalized groups enhances community trust and reduces stigma (Flynn and Brockner 2003), suggesting that empowering recipients is both ethically imperative and pragmatically efficient. Theoretically, studies have elucidated how welfare systems may suppress this potential (Guo and Peck 2009; Peck et al. 2012; Peck and Guo, 2015). By interrogating this paradox, this study argues for a shift in focus from “whether recipients can give” to “how institutions enable or constrain their agency” in assuming social responsibilities—offering a novel perspective for rethinking welfare design globally. Moreover, from a practical standpoint, understanding how different forms of social assistance influence recipients’ philanthropic behaviors is critical for policy design and NGO strategy. In contexts where state resources are limited and NGOs are increasingly involved in service delivery, empowering recipients to contribute philanthropically can strengthen social cohesion, reduce dependency, and promote inclusive growth (Brooks 2002). This research not only addresses a theoretical gap regarding institutional logics in authoritarian settings but also provides actionable insights for policymakers and NGOs seeking to optimize social assistance systems for both material and moral empowerment.

There are controversial opinions regarding the impact of social assistance on recipients’ philanthropic behaviors due to the unclear mechanisms of the impact (i.e., Gustavo 2013; Yang et al. 2021). Distinguishing forms of social assistance could clarify the mechanism. The global system of modern social assistance has two main forms: state assistance and charitable assistance. State assistance is a benefit in cash or in-kind, financed by the government (national or local) and usually provided based on a means or income test (Howell 2001). Charitable assistance refers to NGOs and social forces providing gratis support to vulnerable groups in the form of materials or services for wellbeing (Gao and Wu 2022). The former is based on the principle of fairness and civil rights, while the latter is based on the principle of social responsibility, which could lead to differential influence on recipients’ philanthropic behaviors. In addition, for recipients of multiple forms of social assistance, the impact of aid experiences on their philanthropic behaviors could be even more complicated. The government continuously encourages NGOs to supplement the assistance due to its heavy public financial burden (Gao 2017), and NGOs could influence the government’s delivery of public services (Cheng 2019). The theoretical perspective of institutional logics indicates that the state-society relationship could profoundly affect the performance of mixed forms of social assistance.

Under the above background, this study explores the interaction between social assistance experiences and prosocial behaviors of aid recipients from the theoretical perspective of institutional logics, aiming to answer the following research questions: firstly, how do philanthropic behaviors of aid recipients occurre and do the diverse forms of social assistance have different effects? Secondly, what are these differences? Thirdly, what are the implications for policy design regarding optimizing the system of social assistance in order to motivate recipients’ prosocial behaviors? China’s case offers a theoretically strategic context that its authoritarian governance would amplify institutional logic conflicts in terms of state control and NGO autonomy, providing a “critical case” to examine how political structures shape welfare outcomes (Heurlin 2010). While prior studies focus on Western democracies, this study will reveal how state dominance reconfigures prosociality—a contribution vital to global scholarship on welfare regimes and civic participation under authoritarianism. Therefore, this empirical study employs data from the China Family Panel Studies (CFPS), a national representative data, offering implications for other authoritarian regimes with hybrid governance seeking to balance social innovation with political control, and optimizing the policy design of state assistance and charitable assistance to empower recipients regarding philanthropic engagement.

Literature review

Several studies suggest that aid experiences, including receiving social assistance, can empower recipients by promoting their philanthropic behaviors, such as charitable giving and volunteering (Gustavo 2013). On the one hand, from the perspective of individual emotion-behaviors, receiving aid stimulates individual’s prosocial attitudes, such as gratitude and empathy (Batson and Ahmad 2001). Gratitude, in particular, arises from the relationship between the giver and the recipient, leading to altruistic behavior, such as charitable giving (Flynn and Brockner 2003). Aid experience also enhances recipients’ empathy, thus increasing the likelihood of charitable giving (Andorfer and Otte 2013). On the other hand, from the perspective of reciprocity, recipients of aid or social assistance are often motivated to cultivate a sense of returning the generosity and benefits they have received to society (Moody 2008), thus promoting prosocial behavior (Shumaker and Brownell 1984).

Nevertheless, some studies argue that aid experiences, especially receiving social assistance, have negative impacts on recipients’ philanthropic behaviors. Yang et al.’s (2021) study based on a U.S. sample reveals an inverse relationship between the amount of social assistance received and the amount of donations. This phenomenon may be attributed to long-standing U.S. welfare policies that foster recipients’ reliance on social welfare. In line with Titmuss’s view (1968), recipients of social assistance still frequently encounter stigma even in low-income countries (Roelen 2020; Nadler and Chernyak-Hai 2014), being branded as lazy and morally undervalued (Swartz et al. 2009) and perceived as unwilling to improve their economic status (Petersen et al. 2012). Consequently, this leads to reduced motivation and ability to help others. Studies conclude that receiving social assistance reduces recipients’ charitable giving (Brooks 2002; Peck et al. 2012). Even when recipients are capable of charitable engagement, they tend to donate time through voluntary work rather than contributing financially (Guo and Peck 2009). Moreover, some scholars argue that aid experiences have no significant effect on recipients’ voluntary behaviors (Swartz et al. 2009).

In China, most research has focused on the recipients of Dibao, known as the “Minimum Living Standard Guarantee System” (MLSGS), which constitutes the central program of social assistance (Xiao et al. 2023). However, the impact of social assistance on recipients’ prosocial behaviors is still controversial. Some scholars suggest a positive impact of social assistance on recipients’ prosocial attitudes, stating that social assistance identity increases the social participation of recipients’ families and bolsters their positive attitudes towards engagement in community activities (Guo and Zhang 2018). However, some scholars hold the opposite view, arguing that benefiting from social assistance carries a stigma that hinders recipients’ prosocial behaviors (Leung 2006). Other studies also found no statistically significant relationship between charitable giving and the use of social assistance (Yang et al. 2021).

The disputed impact of social assistance on recipients’ philanthropic behaviors is indeed linked to the unclear mechanism of the impact. Distinguishing the forms of social assistance would help to clarify the effect of social assistance on recipients’ philanthropic behaviors and address previous controversies. Moreover, The complex state–society relationship within China’s authoritarian framework brings to light multiple institutional logics through which social assistance influences such behaviors (Kang and Han 2007; Heurlin 2010). Critically, China’s authoritarian environment shapes distinctive social norms that permeate both policy implementation and individual behavior. Unlike Western democracies, where civil society often enjoys relative autonomy, China’s state-dominated context necessitates that NGOs and other social organizations align with state ideologies and operational controls (Wang and Song 2013; Huang and Ji 2016). This pervasive influence reconfigures the mechanisms linking social assistance to recipients’ philanthropic actions, embedding them within broader socio-political expectations, such as those captured by the concepts of “administrative absorption of society” (Kang and Han 2007) and “dependent autonomy” (Wang and Song 2013). As a result, philanthropic logic often becomes subordinate to national logic, thereby influencing how recipients perceive and engage in charitable behaviors (Yang and Wang 2023). By explicitly situating the analysis within these normative and structural conditions, this study offers a refined understanding of how institutional logics function under strong state influence, thereby contributing a nuanced comparative perspective to the literature.

Theoretical perspective and hypotheses

Key factors influencing individual philanthropic behaviors

In general, individuals’ philanthropic behaviors are influenced by external and internal factors (Bekkers and Wiepking 2011; Sargeant and Woodliffe 2007). The external factors include policy, institutional systems, organizational factors, and economic factors (Parsons 2007; Brooks 2004; Light 2008). While the internal factors include self-efficacy and motivations for charitable giving, such as altruistic, self-interested and reciprocal motivations (Andreoni 1990; Lilley and Slonim 2014). Furthermore, demographic factors, such as gender, age, marriage, family, faith, household or individual income, education, and occupation, were also discussed (i.e., Casale and Baumann 2015; Van Slyke and Brooks 2005). In order to better examine the interactions of incentives of giving and the forms of social assistance, the following three factors are considered.

Firstly, economic conditions significantly influence individual philanthropic behaviors. Existing studies show that increased income effectively stimulates charitable giving, while limited economic resources hinder philanthropic engagement (Gittell and Tebaldi 2006). For aid recipients, their disadvantages are primarily influenced by economic conditions. When there is a low economic capacity, it results in high costs and limited investments in philanthropy. This ultimately hinders philanthropic behaviors significantly for both aid recipients and non-recipients.

Secondly, self-efficacy plays a crucial role among internal drivers of giving. Self-efficacy refers to an individual’s belief in their own capacity to execute behaviors necessary to produce specific performance attainments. Rooted in social cognitive theory, it emphasizes the role of personal agency—those with higher self-efficacy are more likely to feel confident in their abilities and anticipate successful outcomes. People give more along with the increase of self-efficacy (Sharma and Morwitz 2016). However, when donors perceive the needs for help as overwhelming, low self-efficacy may deter them from providing assistance (Bendapudi et al. 1996). With increasing perception of self-efficacy, aid recipients would also have the confidence and positive anticipation to engage in philanthropic activities.

Lastly, perceived reciprocity embedded in the interaction between members of society has an important impact on individual philanthropic behaviors. The theory of gift exchange indicates that interactions between groups would trigger a cyclical process of receiving and giving, resembling a model of exchange in pre-modern or ancient societies (Mauss 2000). According to previous research, reciprocity motivates charitable giving in three situations: firstly, when people previously helped expect to give back to society; secondly, when people expect assistance if get into trouble in the future; and thirdly, when people expect to establish a social rule of mutual help (Dolnicar and Randle 2007). It is particularly true for aid recipients. When recipients benefit from others, especially from strangers or non-stakeholders, they could feel obliged to return the favor by giving back or helping another person (Grant and Dutton 2012). Thus, perceived reciprocity, especially when it stems from past aid experiences, effectively drives prosocial behaviors of both aid recipients and non-recipients.

Accordingly, the following hypotheses are proposed.

H1. Economic conditions have a significantly positive effect on individual philanthropic behaviors.

H2. Self-efficacy has a significantly positive effect on individual philanthropic behaviors.

H3. Perceived reciprocity has a significantly positive effect on individual philanthropic behaviors.

The effect of the forms of social assistance on the occurrence mechanisms of individual philanthropic behaviors

Theoretical perspective

As mentioned previously, there are two main forms of social assistance, namely state assistance and charitable assistance. Individual philanthropic behaviors may vary under the influence of the multiple forms of social assistance according to specific institutional logics. The theory of institutional logics is derived from Neo-institutionalism theory assuming that the mission, nature and values of individuals and organizations are embedded in institutional logic. This logic represents a socially-constructed historical model of culture, practices, values, beliefs and rules that shape actors’ perceptions and behaviors (Thornton et al. 2012). In this model, individuals produce and reproduce their material lives, organize time and space, and interpret or assign meaning to the social reality (Thornton and Ocasio 1999).

Actors are embedded in multiple institutional logics, which can be competing and conflicting, compatible and complementary, coexisting and transformable within the field (Haveman and Rao 1997; McPherson and Sauder 2013). Thus, actors adapt their strategies based on the multiple institutional logics they encounter (Kraatz and Block 2008). For example, in the field of philanthropy, Xu and Zhang (2021) introduce the multiple institutional logic of the practice of charitable trust. As such practice involves four actors, namely the central government, the local government, enterprises and NGOs, the multiple institutional logics are national logic, bureaucratic logic, social-responsibility logic and philanthropic logic, respectively.

The effect of state assistance on individual philanthropic behaviors following national logic

State assistance is an institutionalized program funded by public finance. It is designed to support individuals at risks like unemployment and poverty, functioning as a right-based program embodied national logic (Leung 2006). The effect of state assistance on individual philanthropic behaviors is policy-driven.

First of all, according to the policy of social assistance in China, Dibao is the bottom line of state assistance aiming for the survival purpose of recipients. State assistance policy strictly targets recipients based on their economic conditions. The recipients of Dibao are often social groups with no or extremely low labor capacity, and they rely on state assistance for maintaining a minimum standard of living. Thus state assistance can hardly empower recipients with the capacity to engage in charitable activities. Moreover, previous research has revealed that the recipients of state assistance are less likely to donate money (Peck and Guo 2015). In other words, state assistance may reinforce the impact of economic constraints on hindering recipient’ charitable giving.

Additionally, previous research has pointed out that recipients of state assistance are often perceived as idle and lacking initiative (Petersen et al. 2012). The continuous societal bias regarding the perceived low morality of the recipient intensifies the recipients’ tendency to internalize the unfair judgment, amplifying self-stigmatization and potentially fostering a dependence on welfare systems that “if you benefit from social welfare, you should always be benefited” (Lei and Chan 2019). It indicates that the recipients of state assistance could generally undervalue self-efficacy, thus diminishing the beneficial impacts of self-efficacy on philanthropic contributions. Consequently, compared to non-recipients, self-efficacy is less powerful in stimulating philanthropic behaviors of recipients of state assistance.

Finally, recipients of “rights-based” state assistance usually perceive the aid as an entitlement or a welfare endowed by civil rights, leading to a reduced awareness of their social responsibility to repay (Leung 2006). This perspective is exemplified by the traditional notion of “a fool refuses money from the government ” (zhengfu de qian buyao bai buyao), where state assistance is viewed as the government’s obligation to help the poor and even as a means to influence village cadres (Li and Walker 2018). As recipients can hardly perceive benevolence during the process of state assistance, it hampers the power of perceived reciprocity in promoting reward through charitable engagement. In other words, compared to non-recipients, perceived reciprocity is less important in stimulating philanthropic behaviors of recipients of state assistance.

Therefore, the following hypotheses are proposed accordingly.

H4a. Only receiving state assistance enhances the effect of economic conditions on individual philanthropic behaviors.

H4b. Only receiving state assistance weakens the effect of self-efficacy on individual philanthropic behaviors.

H4c. Only receiving state assistance weakens the effect of perceived reciprocity on individual philanthropic behaviors.

The effect of charitable assistance on individual philanthropic behaviors following philanthropic logic

Charitable assistance is mainly provided by NGOs focusing on material support and capacity building for the vulnerable. It embodies philanthropic logic focusing on the development of beneficiaries following the spirit of “helping people to help themselves” (Gao and Wu 2022). Thus, charitable assistance could pose different effects on individual philanthropic behaviors compared to state assistance.

Firstly, the targeting mechanism of the recipients of charitable assistance is not based exclusively on economic conditions. Charitable assistance extends beyond helping those in low economic circumstances to include individuals facing emergencies or unexpected disasters (Graziano et al. 2007). People receiving charitable assistance may not just be for survival needs, but could also be for developmental purposes such as getting better education, indicating their philanthropic capacity is not necessarily tied to improvement of economic conditions. Consequently, charitable assistance may weaken the effect of economic conditions on recipients’ philanthropic behaviors.

Furthermore, charitable assistance helps to prevent recipients’ self-stigmatizing by instilling philanthropic values, thereby increasing the power of self-efficacy in stimulating their charitable behaviors. Charitable assistance is based on the principle of responsibility and the long-term value of “helping people to help themselves”. During the aid process, NGOs strive to empower recipients both materially and spiritually (Gao and Wu 2022), thus enhancing the effect of self-efficacy in promoting charitable activities to help others. Therefore, philanthropic behaviors of recipients of charitable assistance is more likely to be connected with self-efficacy than that of non-recipients.

Last of all, differing from the state assistance ideology of “citizenship” and “welfare justice”, charitable assistance incorporates a reciprocal mechanism that empowers recipients’ philanthropic behaviors. Charitable assistance is often provided by NGOs, businesses, and the general public, and recipients usually do not take such aid for granted. This motivates them to give back to society through philanthropic participation (Kalenkoski 2014). From the perspective of stakeholders, donors and beneficiaries, identified as key stakeholders, foster a mutual and trusting “collaborative” framework, with donors sometimes sacrificing their own interests to champion the causes and needs of beneficiaries (Connolly and Hyndman 2017). Therefore, compared to non-recipients, the recipients of charitable assistance would be more likely to donate effected by perceived reciprocity.

Accordingly, the following hypotheses are proposed.

H5a. Only receiving charitable assistance weakens the effect of economic conditions on individual philanthropic behaviors.

H5b. Only receiving charitable assistance enhances the effect of self-efficacy on individual philanthropic behaviors.

H5c. Only receiving charitable assistance enhances the effect of perceived reciprocity on individual philanthropic behaviors.

The effect of mixed assistance on individual philanthropic behaviors

There are mixed forms of social assistance in which national logic and philanthropic logic intersect. It requires a response to the state-society relationship. Taking China as an example, the government has traditionally dominated the development of philanthropy since the founding of the People’s Republic of China. Regarding the most influential theory explaining the state-society relationship grounded in China, Kang and Han (2005) illustrate the core of “the system of differential controls” (fenlei kongzhi tixi), which is the government adopting different strategies and policy tools of controlling NGOs based on their capacities of challenging the government and providing public services. They then proposed the concept of “administrative absorption of society” (xingzheng xina shehui), emphasizing “control”, “functional substitution” and “prioritizing the interests of the powerful”, which is more in line with the contemporary dominance of the government in China (Kang and Han 2007). This is similar to the concept of Omnipotent Government in Western studies. Although it emphasizes democracy and social participation, the government has absolute control over NGOs, especially at the ideological and activity levels (Heurlin 2010).

Based on the above theories, scholars further explained the government’s dominant role in China’s state-society relationship, and successively put forward the concepts including “administrative absorption of services” (xingzheng xina fuwu) (Tang 2010), and “floating control and multi-level embeddedness” (fudong kongzhi yu fenceng qianru) (Xu and Li 2018). NGOs in China are also featured by “dependent autonomy” (yifushi zizhu), with high dependency on the government but low autonomy (Wang and Song 2013). Under the logic of “micromanagement” (jishu zhili), the “administrative subcontract” (xingzheng fabaozhi) promotes NGOs to focus on administrative duties while becoming increasingly detached from social values, and puts themselves into a subsidiary position in social service (Huang and Ji 2016).

Consequently, philanthropic logic would be subordinate to national logic, aligned with the state-society relationship in modern China. In the process of social assistance, although NGOs prioritize philanthropic values and the cultivation of recipients’ initiative, they operate within the framework defined by the government. When the government purchases service from NGOs, it typically regards them as instruments to solve social problems, often underutilizing their functions such as protesting for public interests and demands. In their pursuit of legitimacy and financial support, NGOs align their services with local government priorities, following governmental standards in targeting recipients and providing services. NGOs may even allow local governments to intervene in specific charitable projects. Therefore, such subordination hinders the recipients’ perception of philanthropy, potentially leading them to equate charitable assistance with state assistance in China (Yang and Wang 2023).

Hence, following the national logic of state assistance, the hypotheses are proposed as follows.

H6a. Receiving mixed assistance enhances the effect of economic conditions on individual philanthropic behaviors.

H6b. Receiving mixed assistance weakens the effect of self-efficacy on individual philanthropic behaviors.

H6c. Receiving mixed assistance weakens the effect of perceived reciprocity on individual philanthropic behaviors.

Methods

Data

This study employed data from the China Family Panel Studies (CFPS), a national interdisciplinary survey available at http://isss.pku.edu.cn/cfps/index.htm. The survey collects data from 31 provinces in China across individual, household and community levels. In order to investigate relationship between social assistance and philanthropic behaviors, this study used two rounds of tracking samples of CFPS in 2016 and 2018, and combined the individual questionnaire and the household questionnaire. Respondents across the two waves were matched using the unique ID in CFPS, which ensured that the final sample tracked the same individuals at both time points. A total of 22,707 samples matched by the two rounds of surveys were finally retained for analyses.

Variables

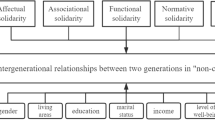

Variables in this study are listed in Table 1. The dependent variable is the respondent’s charitable giving in 2018, which was measured by “Have you ever donated to any organization or individual in the past 12 months?” The independent variables influencing individual philanthropic behaviors include (1) economic conditions measured by the logarithm of annual household income (yuan), (2) self-efficacy identified with the item “the confidence in the future life of my own”, (3) perceived reciprocity identified with the item “Do you think most people are ready to help others?”.

The moderating variable is the forms of social assistance received in 2016. State assistance was measured with the item “In the past 12 months, has your family received various subsidies from the government in cash or in kind (such as Dibao, five-guarantee subsidy, special hardship subsidy, and disaster relief funds)?” Charitable assistance was measured with the item “In the past 12 months, has your family received any charitable donations in cash or in kind (such as food, clothing, etc.)?”.On the basis of the above variables, four forms of social assistance were generated, namely, only received state assistance, only received charitable assistance, mixed assistance, and non-recipients.

The factors that are widely recognized as being correlated with charitable giving were also considered as control variables as follows. (1) education level; (2) gender; (3) age; (4) religious belief; (5) employment status; (6) Party status; (7) whether the family has underage children; (8) Marital status; (9) social trust; (10) social interaction. The descriptive statistics are summarized in Table 2.

Analytic strategy

The main effect model

Since the dependent variable of charitable giving is dichotomous, this study employed logit regression model. Besides, as some independent variables and control variables were at the household level, random effects were examined using multi-level analysis. Stata MP17.0 was used for data analysis. As displayed as below, pi is the incidence of charitable giving; \(\frac{{pi}}{1-{pi}}\) denotes the occurrence ratio of charitable giving; β0 denotes the constant term; i denotes the individual level, f denotes the household level; μi denotes random error term; εif denotes unobserved effects. In order to assess the robustness, we add model (4) to further verify the main effect. In model (1) to model (4), X1, X2 X3 are independent variables, representing economic conditions, self-efficacy, and perceived reciprocity respectively; Zif denotes control variables.

The moderating effect model

In order to test whether the forms of social assistance moderate the effect of economic conditions, self-efficacy and perceived reciprocity on philanthropic behaviors, this study conducted a two-stage test. Similar to the main effect model, we adopted binary logit regression model, and random effects were examined using multi-level analysis. The moderating effect model including interaction terms as follows. Based on the main effect mode, in model (5) to model (7), W is the moderating variable, denoting the forms of social assistance namely only received state assistance, only received charitable assistance, received mixed assistance, and non-recipients; X1W, X2W and X3W are the interactions between independent variables and the forms of social assistance. If they are significant, there are significant moderating effects of the forms of social assistance.

Robustness test model

In order to test the robustness of the main effects, the instrumental variable (IV) approach was adopted. Estimation is conducted using a two-stage procedure. Given that the dependent variable—whether the recipient donates—is binary, this study apply IV-Probit models estimated via maximum likelihood. The two-stage specification is as follows from model (8) to model (13). Where \({\hat{X}}_{1}\),\({\hat{X}}_{2}\),\({\hat{X}}_{3}\) are the first-stage predicted value for X1, X2, and X3, respectively; Givingif is charitable giving for individual i in household f; εif, ϵif denote unobserved effects.

In order to test the robustness of the moderating effects, this study divided sub samples according to the forms of social assistance, and conducted logit regression analysis, respectively. The models are as follows. In model (14), X1, X2, X3 are independent variables, denoting economic conditions, self-efficacy, and perceived reciprocity, respectively, which were put together in the same model. Due to the small amount of sub samples corresponding to specific forms of social assistance, it was not possible to fit a model including random effects.

Results

The factors influencing individual philanthropic behaviors

In Table 3, Model 1 revealed a significantly positive correlation between economic conditions and the occurrence of individual charitable giving (p = 0.000), confirming H1. Similarly, Model 2 demonstrated a significantly positive correlation between self-efficacy and the occurrence of individual charitable giving (p = 0.012), validating H2. Nevertheless, Model 3 showed perceived reciprocity has no significant effect on individual charitable giving (p = 0.348). Thus, H3 was not substantiated. Model 4 also verified the above findings, with no multicollinearity for all independent variables (VIF < 2).

The moderating effect of forms of social assistance

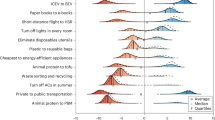

In Table 4, Model 5 indicated a significantly positive effect between economic conditions and individual giving (p = 0.000), and the interaction item “Only received state assistance × Economic conditions” had a significantly positive effect on individual giving (p = 0.088). Figure 1 showed synergistic interaction effects, indicating that receiving only state assistance enhanced the relation between economic conditions and individual giving. However, the interactions of economic conditions with other forms of social assistance were not significant. Therefore, H4a was valid while H5a and H6a were not.

Model 6 revealed that self-efficacy had a significantly positive effect on individual giving (p = 0.089), and the interaction item “Mixed assistance × Self-efficacy” had a significantly negative effect on individual giving (p = 0.001). Figure 1 showed disordinal interaction effects, denoting that receiving mixed assistance weakened the influence of self-efficacy on individual giving. However, the interactions of self-efficacy with other forms of social assistance were not significant. Therefore, H6b was supported while H4b and H5b were not.

In Model 7, the regression results indicated no significant effect between the perceived reciprocity and individual giving, while the interaction term “Mixed assistance × Perceived reciprocity” had a significantly negative effect on individual giving (p = 0.083). Figure 1 showed disordinal interaction effects, revealing that receiving mixed assistance weakened the influence of perceived reciprocity on individual giving. However, interactions of perceived reciprocity with other forms of social assistance were not significant. Consequently, while H6c was supported, H4c and H5c were not.

Robustness test

To mitigate endogeneity concerns, an instrumental variable (IV) approach was adopted to estimate the effects of key drivers on recipients’ charitable giving. First, the average economic condition of other households in the same community (excluding the recipient’s own) serves as the IV for household economic status. This variable captures the local socioeconomic environment influencing behavior through contextual effects, satisfying the relevance criterion (Glaeser et al. 2003), while being exogenous to an individual’s donation decision. Second, this study employs self-assessed work efficiency as the IV for self-efficacy, as it correlates strongly with self-efficacy (Stajkovic and Luthans 1998) but is unlikely to directly affect giving (Cherian and Jacob 2013). Finally, an individual’s evaluation of government performance is used as the IV for perceived reciprocity. Such evaluations, shaped by street-level interactions, generalize into broader societal judgments (Brown 2007; Lipsky 2010) and foster beliefs in social support central to reciprocity (Esaiasson 2010; Hansen 2023), yet remain exogenous to a specific donation act.

Models 8 to 10 in Table 5 report the results of the IV-Probit estimation. After correcting for endogeneity, the coefficients for economic condition, self-efficacy, and perceived reciprocity each exhibit a statistically significant positive influence on recipients’ charitable giving, thus confirming hypotheses H1 through H3. The IVs demonstrate strong relevance, as indicated by Wald test p-values below 0.001 for all models. In summary, these findings reinforce the robustness of the main effects estimated in the study.

To further analyze the moderating effect of different forms of social assistance, this study categorized the sample into four subgroups based on the forms of social assistance and conducted regression analyses, with no multicollinearity for all independent variables (VIF < 2). As the sample size of the recipients of charitable assistance is relatively smallFootnote 1, bootstrap with 1500 replicates was used for Fisher’ s Permutation test. In Table 6, models 11 showed the coefficients of economic conditions’ impact on individual giving among recipients who “Only received state assistance” and “Non-recipients”. The result of Fisher’s Permutation test showed the coefficient of between-group variation was significant (β0-β1 = -0.057, p = 0.069), indicating that state assistance strengthened the impact of economic conditions on individual giving, thus confirming H4a. However, models 12 showed charitable assistance strengthened the positive impact of economic conditions on individual giving (β0-β1 = -1.143, p = 0.023), against H5a. Additionally, models 13 showed that mixed assistance weakened the impact of self-efficacy and perceived reciprocity on individual giving with the coefficient of between-group variation of 0.434 (p = 0.008) and 0.493 (p = 0.088) respectively, providing support for H6b and H6c.

Discussion

Drawing on the tracking data from CFPS, this study reveals that different forms of social assistance differentially moderate the mechanisms driving philanthropic behavior among recipients in China. Firstly, state assistance strengthened the effect of economic conditions on individual philanthropic behaviors. In China, means-tested government subsidies are the primary form of social assistance. The national logic magnifies the impact of economic status on charitable giving of the recipients of state assistance. Secondly, mixed assistance weakened the effect of self-efficacy and perceived reciprocity on individual philanthropic behaviors. As the philanthropic logic is subordinate to the national logic in China, charitable assistance does not offset the negative effects of self-stigma and a low sense of reciprocity embedded in state assistance.

However, against the hypotheses, charitable assistance did not enhance the effect of self-efficacy nor perceived reciprocity on recipients’ philanthropic behaviors. Further, robustness test results showed charitable assistance strengthened the effect of economic conditions on recipients’ philanthropic behaviors. It revealed the dilemma of developing modern philanthropy in China that is constrained by a self-reinforcing triad of state dominance, NGO fragility, and public distrust, which collectively undermine charitable assistance’s capacity to inspire recipients’ prosocial behaviors. The government’s dual role as promoter and regulator prioritizes stability over innovation, exemplified by the 2016 Charity Law’s stringent NGO controls that reduce civil society to bureaucratic implementers of state agendas, fostering paternalistic aid models focused on material provision rather than empowerment. Concurrently, there is still a large proportion of NGOs depend on state-linked funding, stifling grassroots innovation and perpetuating a fragmented ecosystem where recipients remain passive beneficiaries. Public trust in NGOs is further eroded by scandals like the 2011 Red Cross case, with only 35% of Chinese citizens trusting NGOs—half the U.S. rate—as aid is perceived as politically performative rather than altruistic.

These findings suggest that in China’s authoritarian context, where state logic often subordinates philanthropic logic, the empowering potential of charitable aid may be diluted when combined with state-led assistance. This aligns with the concept of “administrative absorption” (Kang and Han, 2007), where NGO initiatives are often co-opted by state agendas, reducing their capacity to foster autonomous prosocial motivation among recipients. These findings underscore the hierarchical interplay between state and philanthropic logics in authoritarian settings and highlight the need for policy designs that better integrate empowerment-oriented approaches into social assistance programs.

Conclusion

To conclude, contrary to initial expectations, charitable assistance alone did not significantly enhance the effects of self-efficacy or perceived reciprocity on philanthropic behavior. Instead, state assistance reinforced the role of economic conditions, while mixed assistance weakened the influences of both self-efficacy and perceived reciprocity. Regarding theoretical contributions, building on Thornton et al. (2012), this study extends institutional logics scholarship, which typically examines competing or complementary logics in democratic settings (McPherson and Sauder 2013), by demonstrating how authoritarian states enforce logic subordination. The findings reveal that mixed assistance weakens the positive effects of self-efficacy and perceived reciprocity precisely because NGOs, operating under state micromanagement (Huang and Ji 2016), cannot fully enact philanthropic principles like empowerment. This challenges assumptions about NGO autonomy in public service delivery and refines institutional logics theory to account for state-imposed hierarchy in hybrid governance systems.

For practical implications, the findings call for optimizing policy design of social assistance to empower recipients in terms of stimulating their philanthropic behaviors. It involves improving and integrating the logic of different forms of aid to strengthen self-efficacy and recipients’ sense of reciprocity while mitigating the fatal influence of economic conditions on recipients’ philanthropic behaviors. To transform state assistance from survival to developmental support, incentive-based policies should eradicate welfare stigma and enhance recipients’ social reputation by promoting positive examples and self-worth. Addressing multi-level needs beyond economics can also mitigate barriers to charitable participation. Moreover, governments must provide platforms for recipients to engage in philanthropy, fostering responsibility and intrinsic motivations for shared prosperity. Meanwhile, collaborative tools should strengthen philanthropic logic’s influence on state logic. Leveraging existing mechanisms such as government-purchased services, NGOs can manage programs where recipients participate in community volunteering. Models such as Shanghai’s Social Organization Incubator integrate philanthropic approaches into state-led poverty alleviation by training recipients to lead projects, maintaining central oversight while building reciprocity, thus addressing philanthropic logic’s subordination.

Limitations and future research

This exploratory study has limitations based on which points directions for future research. Firstly, this study examined recipients’ philanthropic behaviors in terms of charitable giving. Future studies are suggested to further examine recipients’ participation in voluntary work, so as to depict the occurrence mechanism of recipients’ philanthropic behaviors comprehensively. Additionally, the group of aid recipients tends to be heterogeneous, so is the effect of the forms of social assistance on the occurrence mechanisms of their philanthropic behaviors. Therefore, future research could consider more features of recipients and more independent variables to deepen the exploration of occurrence mechanisms of recipients’ philanthropic behaviors. Finally, despite the temporal ordering and IV strategy, unobserved confounders may still exist, and that future research with longer panel data or experimental designs would be needed to firmly establish causality.

Data availability

The data supporting this study have been deposited in China Family Panel Studies (CFPS) and is accessible via http://isss.pku.edu.cn/cfps/sjzx/gksj/index.htm after registration on the CFPS data platform. The raw data of CFPS 2016 and CFPS 2018 used in this study can also be downloaded from the platform of Beijing University Open Research Data via https://opendata.pku.edu.cn/file.xhtml?fileId=9998&version=45.1 and https://opendata.pku.edu.cn/file.xhtml?fileId=10714&version=45.1 respectively after user registration.

Notes

In CFPS, the sample size of the recipients of charitable assistance is relatively small, which accounts for 0.66%, 0.71%, 0.78% of the total sample of the recipients of social assistance in the year of 2014, 2016 and 2018 respectively. It is in line with the fact that the total amount of the recipients of charitable assistance in China is small, especially in comparison with those received state assistance. Since CFPS employed valid sampling methods, the sample size and structure of the recipients of social assistance is representative, based on which the estimates and analysis results are reliable.

References

Andreoni J (1990) Impure altruism and donations to public goods: a theory of warm-glow giving. Econ J 100(401):464–477

Andorfer VA, Otte G (2013) Do contexts matter for willingness to donate to natural disaster relief? An application of the factorial survey. Nonprofit Volunt Sect Q 42(4):657–688

Batson CD, Ahmad N (2001) Empathy-induced altruism in a prisoner’s dilemma II: what if the target of empathy has defected? Eur J Soc Psychol 31(1):25–36

Bekkers R, Wiepking P (2011) A literature review of empirical studies of philanthropy: eight mechanisms that drive charitable giving. Nonprofit Volunt Sect Q 40(5):924–973

Bendapudi N, Singh SN, Bendapudi V (1996) Enhancing helping behavior: an integrative framework for promotion planning. J Mark 60(3):33–49

Brooks AC (2002) Welfare receipt and private charity. Public Budg Financ 22(3):101–114

Brooks AC (2004) The effects of public policy on private charity. Adm Soc 36(2):166–185

Brown T (2007) Coercion versus choice: Citizen evaluation of public service quality across methods of consumption. Public Adm Rev 67(3):559–572

Casale D, Baumann A (2015) Who gives to international causes? A demographics analysis of U.S. donors. Nonprofit Volunt Sect Q 44(1):98–122

Cheng Y (2019) Nonprofit spending and government provision of public services: testing theories of government-nonprofit relationships. J Public Adm Res Theory 29(2):238–254

Cherian J, Jacob J (2013) Impact of self efficacy on motivation and performance of employees. Int J Bus Manag 8(14):80–88

Connolly C, Hyndman N (2017) The donor-beneficiary charity accountability paradox: a tale of two stakeholders. Public Money Manag 37(3):157–164

Dolnicar S, Randle M (2007) The international volunteering market: market segments and competitive relations. Int J Nonprofit Volunt Sect Mark 12(4):350–370

Esaiasson P (2010) Will citizens take no for an answer? What government officials can do to enhance decision acceptance. Eur Polit Sci Rev 2(3):351–371

Flynn FJ, Brockner J (2003) It’s different to give than to receive: predictors of givers’ and receivers’ reactions to favor exchange. J Appl Psychol 88(6):1034–1045

Gao J, Wu Y (2022) Modes of providing charitable assistance and innovations. In: Gao J (ed) Mechanisms of charitable donations in China. Springer, p 259-296

Gao Q (2017) Welfare, work, and poverty: social assistance in China. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Gittell R, Tebaldi E (2006) Charitable giving: factors influencing giving in U.S. states. Nonprofit Volunt Sect Q 35(4):721–736

Glaeser EL, Sacerdote BI, Scheinkman JA (2003) The social multiplier. J Eur Econ Assoc 1(2):345–353

Grant A, Dutton J (2012) Beneficiary or benefactor: are people more prosocial when they reflect on receiving or giving? Psychol Sci 23(9):1033–1039

Graziano WG, Habashi MM, Sheese BE, Tobin RM (2007) Agreeableness, empathy, and helping: a person x situation perspective. J Pers Soc Psychol 93(4):583–599

Guo C, Peck LR (2009) Giving and getting: charitable activity and public assistance. Adm Soc 41(5):600–627

Guo Y, Zhang Y (2018) Social participation, network and trust: the impact of social assistance on social capital [in Chinese]. Soc Secur Stud 2:54–62

Gustavo C (2013) The development and correlates of prosocial moral behaviors. Psychology Press, London

Hansen FG (2023) Can warm behavior mitigate the negative effect of unfavorable governmental decisions on citizens’ trust? J Exp Polit Sci 10(1):62–75

Haveman HA, Rao H (1997) Structuring a theory of moral sentiments: institutional and organizational coevolution in the early thrift industry. Am J Socio 102(6):1606–1651

Heurlin C (2010) Governing civil society: the political logic of NGO-state relations under dictatorship. Voluntas 21(2):220–239

Howell F (eds) (2001) Social assistance: Theoretical background. In: Ortiz I (ed) Social Protection in the Asia and Pacific. Asian Development Bank, Manila

Huang X, Ji X (2016) Limits to micromanagement and logic of the reform [in Chinese]. J Soc Sci 11:72–79

Kalenkoski CM (2014) Does generosity beget generosity? The relationships between transfer receipt and formal and informal volunteering. Rev Econ House 12(3):547–563

Kang X, Han H (2005) Graduated controls: the state-society relationship in contemporary China [in Chinese]. Socio Res 6:73–89

Kang X, Han H (2007) Administrative absorption of society: a further probe into the state–society relationship in Chinese mainland [in Chinese]. Soc Sci China 28(2):116–128

Kraatz MS, Block ES (2008) Organizational implications of institutional pluralism. In: Greenwood R, Oliver C, Suddaby R, Sahlin-Andersson K (eds) The sage handbook of organizational institutionalism. Sage, p 243–275

Lei J, Chan CK (2019) Does China’s public assistance scheme create welfare dependency? An assessment of the welfare of the urban minimum living standard guarantee. Int Soc Work 62(2):487–501

Leung JCB (2006) The emergence of social assistance in China. Int J Soc Welf 15(3):188–198

Li M, Walker R (2018) On the origins of welfare stigma: comparing two social assistance schemes in rural China. Crit Soc Policy 38(4):667–687

Light PC (2008) How Americans view charities: a report on charitable confidence. Brookings Institution, Washington

Lilley A, Slonim R (2014) The price of warm glow. J Public Econ 114:58–74

Lipsky M (eds) (2010) Street-Level Bureaucracy, 30th Ann. Ed.: dilemmas of the Individual in Public Service. Russell Sage Foundation, New York

Mauss M (2000) The Gift: the Form and Reason for Exchange in Archaic Societies. WW Norton & Company, New York

McPherson CM, Sauder M (2013) Logics in action: managing institutional complexity in a drug court. Adm Sci Q 58(2):165–196

Moody M (2008) Serial reciprocity: a preliminary statement. Soc Theory 26(2):130–151

Nadler A, Chernyak-Hai L (2014) Helping them stay where they are: status effects on dependency/autonomy-oriented helping. J Pers Soc Psychol 106(1):58–72

Parsons LM (2007) The impact of financial information and voluntary disclosures on contributions to not-for-profit organizations. Behav Res Acc 19(1):179–196

Peck LR, D’Attoma I, Camillo F, Guo C (2012) A new strategy for reducing selection bias in nonexperimental evaluations, and the case of how public assistance receipt affects charitable giving. Policy Stud J 40(4):601–625

Peck LR, Guo C (2015) How does public assistance use affect charitable activity? A tale of two methods. Nonprofit Volunt Sect Q 44(4):665–685

Petersen MB, Sznycer D, Cosmides L, Tooby J (2012) Who deserves help? Evolutionary psychology, social emotions, and public opinion about welfare. Polit Psychol 33(3):395–418

Roelen K (2020) Receiving social assistance in low- and middle-income countries: negating shame or producing stigma? J Soc Policy 49(4):705–723

Sargeant A, Woodliffe L (2007) Gift giving: an interdisciplinary review. Int J Nonprofit Volunt Sect Mark 12(4):275–307

Sharma E, Morwitz VG (2016) Saving the masses: the impact of perceived efficacy on charitable giving to single vs. multiple beneficiaries. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process 135:45–54

Shumaker SA, Brownell A (1984) Toward a theory of social support: closing conceptual gaps. J Soc Issues 40(4):11–36

Stajkovic AD, Luthans F (1998) Self-efficacy and work-related performance: a meta-analysis. Psychol Bull 124(2):240–261

Swartz TT, Blackstone A, Uggen C, McLaughlin H (2009) Welfare and citizenship: the effects of government assistance on young adults’ civic participation. Soc Q 50(4):633–665

Tang W (2010) Administrative absorption of service: a new interpretation of the state-society relationship in Chinese mainland [in Chinese]. J Public Manag 7(1):13–19

Thornton PH, Ocasio W (1999) Institutional logics and the historical contingency of power in organizations: executive succession in the higher education publishing industry, 1958- 1990. Am J Socio 105(3):801–843

Thornton PH, Ocasio W, Lounsbury M (2012) The institutional logics perspective: a new approach to culture, structure and process. Oxford University Press

Titmuss RM (1968) Commitment to Welfare. Allen & Unwin

Van Slyke DM, Brooks AC (2005) Why do people give? New evidence and strategies for nonprofit managers. Am Rev Public Adm 35(3):199–222

Villamil A, Wang X, Xue N (2021) A political foundation of public investment and welfare spending. J Public Econ Theory 23(4):660–690

Wang S, Song C (2013) Independence or autonomy: a reflection on the characteristics of Chinese social organizations [in Chinese]. Soc Sci China 5:50–66

Xiao M, Chen H, Li F, Guo Y (2023) The dynamics of social assistance in the informal economy: empirical evidence from urban China. J Soc Policy 52(4):840–863

Xu J, Zhang S (2021) Contact, conflict and adjustment: multiple institutional logic in the practice of charitable trust [in Chinese]. Chin Public Adm 1:59–65

Xu Y, Li X (2018) Floating control and multi-level embeddedness: adjustment mechanisms of the state-society relationship in the context of contracting-out social services [in Chinese]. Socio Stud 33(2):115–139

Yang Y, Wang T (2023) How philanthropic behaviors is transmitted? The multiple institutional logics of beneficiaries’ philanthropic behaviors [in Chinese]. J Public Adm 6:148–166

Yang Y, Zhang J, Liu P (2021) The impact of public assistance use on charitable giving: evidence from the USA and China. Voluntas 32:401–413

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities [2022CDJSKJC25], Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities [2024CDJSKXYGG06], and Chongqing Municipal Social Science Planning Fund [2024NDYB108].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, Yongjiao Yang; methodology, Tong Wang, Yichu Xu and Yongjiao Yang; writing—original draft preparation, Yongjiao Yang and Tong Wang; writing—review and editing, Yongjiao Yang and Yichu Xu.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was not required as the study did not involve human participants.

Informed consent

This study does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, and provide a link to the Creative Commons license. You do not have permission under this license to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, Y., Wang, T. & Xu, Y. How could social assistance empower recipients? The impact of different forms of social assistance on recipients’ philanthropic behaviors. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 13, 116 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-06437-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-06437-9