Abstract

China’s rapid aging has boosted demand for elderly care facilities (ECFs), yet their spatial equity is understudied. This study evaluates and optimizes ECFs accessibility in Dalian using an improved Gaussian two-step floating catchment area (G2SFCA) method, incorporating real-time road distances (via Gaode API) and elderly-specific travel thresholds. Compared to traditional 2SFCA, it addresses limitations like oversimplified Euclidean distance and homogeneous travel assumptions by accounting for distance decay and actual mobility patterns. The Maximum Accessibility Equality (MAE) model, optimized via Coefficient of Variation (CV) and Mean Absolute Deviation (MAD), minimizes spatial inequity through bed reallocation. The research findings are as follow: pre-optimization, 31% of sub-districts had low accessibility, which dropped to 14% post-optimization, with medium-accessibility areas rising to 76%. MAD-MAE achieved a 48.2% lower standard deviation (3.93 vs. CV-MAE’s 7.59). Strategies include reallocating 150 beds from oversupplied urban cores (Zhoushuizi District) to underserved peripheries (Ganjingzi District). This framework offers a scalable solution for equitable public facility allocation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Population ageing is a defining global trend. United Nations data indicates the number of people aged 65 and over is expected to more than double by mid-century, underscoring the critical need to prioritize older persons’ rights and well-being for a sustainable future. By 2030, one-sixth of the world’s population will be over 60, rising to 2.1 billion by 2050, with two-thirds residing in low- and middle-income countries. This global commitment is reflected in the United Nations Decade of Healthy Ageing (2021–2030) and the 2030 Agenda’s pledge to leave no one behind (World Health Organization, 2021; World Health Organization, 2022). China exemplifies this trend with unprecedented speed and scale. Entering deep aging in 2021, its population aged 65 and above reached 15.4% in 2023 and is projected to exceed 20% (super-aging) around 2030 (National Bureau of Statistics, 2021). China’s large base, rapid growth, and “aging before wealth” characteristics make it a critical case study for examining ageing’s impacts. The national strategy Healthy China 2030 (HC2030) (Central People's Government of the People's Republic of China, 2016; Zhao, 2023), a localization of UN Sustainable Development Goals, promotes building an integrated elderly medical and healthcare service system, emphasizing health management and combined health-old age care (Tan et al., 2019; Dai & Menhas, 2020; Ning et al., 2024).

This study focuses on ECFs, defined as facilities providing senior living services, specifically institutional senior living facilities and community aged care centers. Intensified ageing and HC2030 drive increasing societal demand for ECFs (S. Wang & Ma, 2018). Their configuration critically impacts urban quality and elderly living standards, with institutional care often offering higher service/medical quality and scale (Cai et al., 2017). Equitable allocation of such public services, essential for meeting needs and improving quality of life, is a key planning and policy concern (F. Wang & Tang, 2013; Dadashpoor et al., 2016).

The main objective of this study is to improve the realism and precision of the spatial accessibility assessment through an improved 2SFCA model that incorporates a Gaussian distance decay function and utilizes actual road network distances. Appropriate travel thresholds are set, stratified based on the travel habits of the elderly and the service tiers of different levels of ECFs. Furthermore, two optimized MAE formulations are proposed for capacity optimization specifically of ECFs, aiming to minimize the spatial accessibility differences across the study area. This study demonstrates an approach that can also be applied to optimize the allocation of other public facilities such as education and healthcare, and provide insights for policy formulation and urban planning.

Literature review

The fairness of public service facilities distribution is a controversial classic proposition in geography (Talen, 1997). Equity is recognized as an important policy goal in health care. Governments and scholars are focusing on social equity and environmental justice issues, yet this topic is particularly important in China, a developing country with growing urban-rural and regional inequality (Xiao et al., 2017). Current research on inequality by Chinese scholars focuses on housing and urban poverty which inherently involve significant spatial dimensions (Logan et al., 2009; Wu et al., 2010). Research on spatial equity in public facilities is scarcer. There is no uniform definition of spatial equity, but it has rich connotations. Social equity mainly focuses on the differences between different groups, and spatial equity mainly focuses on the differences between different regions (Culyer & Wagstaff, 1993). The connotation of equity includes four dimensions: equalization of resource utilization, equal distribution according to needs, equal accessibility of services and equal health outcomes (Ogryczak, 2009). Equity in public services can be categorized into equity of access and equity of outcome. The equity of accessibility can reflect the equity of opportunity of public services in a region (Culyer & Wagstaff, 1993). Accessibility is mainly used to measure the potential opportunity of a specific group of people in a region to obtain services, determined by the spatial distribution of regional public services and the spatial relationship of the point of demand.

In general, accessibility measures the spatial distribution of activity at a point and adjusts for the ability and desire of people or businesses to overcome spatial separation (Hansen, 1959). Spatial accessibility emphasizes the importance of spatial separation between service providers and populations and how they are spatially interconnected, so location analysis is a classic geographic thesis that lends itself to the application of GIS methodologies for analysis (Joseph & Phillips, 1984). Spatial access depends on the location of the demander, and a simple way to measure spatial accessibility is by the matching ratio of supply and demand in an area (F. Wang, 2012). Spatial accessibility is often used to evaluate how easy it is for people to access public services in a particular location (Sharma & Patil, 2021). Currently, some scholars’ research on spatial accessibility focuses on healthcare facilities (F. Wang, 2012; F. Wang & Tang, 2013), and elderly care facilities (Cheng et al., 2012; He et al., 2023). The main methods for evaluating the spatial accessibility of public service facilities include gravity modeling method (Talen & Anselin, 1998), 2SFCA method (W. Luo & Wang, 2003; Ngui & Apparicio, 2011; Ma et al., 2023), Huff model(J. Luo, 2014), in-depth semi-structured interviews (Cheng et al., 2012), a methodology based in geographical information systems (Iraegui et al., 2020) and so on. Compared with other methods, the 2SFCA method has been found to be particularly suitable or widely adopted in certain contexts for measuring facility accessibility, and therefore is more widely used in studies requiring consideration of both supply and demand within catchment areas. However, the traditional 2SFCA approach has still some deficiencies, and previous literature has improved the 2SFCA model mainly in four aspects: first, incorporating spatial decay functions, for example, using distance-decay functions instead of the dichotomous method (Liu et al., 2022). Second, varying the search radius based on facility type or population characteristics; for instance, elderly facilities in Shanghai are categorized into two types according to their service size, with different search radius applied (Huang et al., 2022). Additionally, considering the unique travel characteristics of the elderly, specific travel thresholds are set to improve the accuracy of the accessibility results (Liu et al., 2022). The third is enhancing the supply-demand interaction within the catchment, such as proposing an Enhanced Variable Two-Step Floating Catchment Area method (EV2SFCA), which aims to minimize potential error caused by mismatch between supply and demand catchments (Ni et al., 2015). Fourth, Luo proposes combining the Huff model with the 2SFCA model, which accounts for choice behavior and enhances the measure (J. Luo, 2014). However, critical gaps persist in addressing multimodal dynamics and temporal congestion effects. Studies like Kunming’s Park accessibility analysis reveal that traditional G2SFCA fails to capture travel mode disparities, where suburban communities face 42% lower walking/cycling access within 15-min thresholds despite adequate driving access (Wu et al., 2025). Similarly, Bratislava’s public transport study demonstrates how fixed schedules ignore real-time congestion impacts, causing 58% accessibility drops for seniors during nighttime service reductions (Hluško et al., 2024). Large-scale analyses further confirm systemic inequities, as seen in U.S. environmental education programs where rural Republican-leaning districts exhibit 73% lower access than urban Democratic areas (Hemby et al., 2024). Previous studies using 2SFCA approaches often have limitations. First, most rely on census data aggregated to areal units to estimate demand, which may not reflect precise locations or population heterogeneity within zones. Second, they may not fully capture differences in travel modes and travel characteristics of specific populations, leading to generalizations that reduce accuracy. Finally, distance calculations in many 2SFCA applications utilize straight-line or Euclidean distances, which are less reflective of actual travel conditions compared to network distances. Therefore, in this paper, an improved Gaussian two-step floating catchment area (G2SFCA) method is used to measure the spatial accessibility between demand and supply points. Specifically, actual road network distances obtained from the Gaode Map API are utilized instead of simplified geometric distances, and travel distance thresholds are set considering the unique travel modes of the elderly to enhance realism. To address these limitations, we advance the Gaussian 2SFCA framework through three innovations: Congestion-integrated multimodal distances using Gaode API’s real-time walking ( ≤ 1.5 km) and driving speeds, overcoming Kunming’s static TB-G2SFCA approach. Considering the time-varying threshold of peak/non-peak impedance, the fixed schedule limitation was solved by using the real-time traffic condition time data based on Gaode API. Different accessibility calculation distance thresholds are adopted according to the scale of elderly care facilities.

The optimal allocation of public facilities is a classic proposition in geography (F. Wang, 2012). Classical models of optimal allocation are usually goal-oriented in terms of efficiency, such as the Location Set Covering Problem (LSCP) that tries to find the minimum number of service supply points to cover all demand nodes within a distance or time criterion(Shavandi & Mahlooji, 2008), and the Maximum Covering Location Problem (MCLP) that aims to maximize the population covered within a specified service distance or time threshold by locating a fixed number of facilities (Murray, 2016). Efficiency and equity are two ends of a scale, two sides of the same coin, and need to be considered together when optimizing facility location. The MAE model (F. Wang & Tang, 2013) represents an approach focused on equity, with minimizing the differences in accessibility to healthcare services across different areas as the optimization goal. (Tao et al., 2014) applied the MAE model to optimize the allocation of elderly facilities in Beijing. Their solution of the spatial equity problem involved a nonlinear programming formulation; they transformed this optimization problem into a quadratic programming problem and introduced the particle swarm optimization method (PSO) to improve computational efficiency. (Wang, 2016) further advanced the work on solving the accessibility equality problem and applied the method to the planning of cancer centers. (Li et al., 2017) also adopted minimizing the accessibility difference as the primary objective. Their research was divided into two phases: facility location optimization and subsequent capacity optimization. Genetic algorithms were used to find the location of new facilities, and then planning methods were used to determine the optimal capacity of facilities within the study area. (J. Luo et al., 2017) further proposed “Two-Step Optimization for Spatial Accessibility Improvement (2SO4SAI)” based on (Li et al., 2017). Stage 1 focuses on the siting of new facilities and mainly addresses efficiency issues; stage 2 focuses on achieving maximum equality of accessibility by adjusting the capacity allocation between existing and new hospitals. The two phases work in sequence to collectively address the planning goals of efficiency and equity. (Liao et al., 2020) proposed a stochastic mechanism incorporating the likelihood of increasing commuting distance to schools and considerations of affected beneficiaries to develop a multi-objective spatial optimization model for improving educational equity. (Tao et al., 2021) developed a hierarchical maximal accessibility equality (HMAE) model designed to maximize equity in healthcare accessibility simultaneously at multiple service levels. Indicators for spatial accessibility measurement are key to the application of MAE models. This study undertakes optimizations of the measurement approach within the MAE framework, drawing insights from the cross-sectional comparative study by (Tao et al., 2023) as well as the actual characteristics of the research object.

Study area

The study area is located in the central urban area of Dalian, Liaoning Province, in northeastern China (Fig. 1). Dalian is an important port, trade and tourist city as it is the maritime gateway to Northeast, North, and East China as well as to the rest of the world. China has entered an “aged society”, Dalian has a unique geographic and social environment that makes it a typical case where aging issues can be studied. As of 2021, the aging rate of Dalian has reached 24.71%, entering the late aging stage. Moreover, Dalian city area is composed of hills and mountains, and transportation and travel modes of residents are mostly by walking, driving and public transportation. In the later section, the actual road network distance of the G2SFCA method uses both walking and driving. Therefore, Dalian can be used as a typical case for the study of actual road network distances based on walking and driving based on the Gaode Map API, and it can provide reference suggestions for cities that are currently in the early stage of aging. The scope of the study is the main urban area of Dalian (Zhongshan District, Xigang District, Shahekou District and Ganjingzi District), including 33 streets.

Data and method

Data acquisition

The data used in this study mainly includes four categories:

Population data: Derived from the street-scale resident population data in the data bulletin of the Sixth and Seventh Population Census of Dalian City. Community-level data was obtained by crawling POI (Point of Interest) data from Lianjia and Anjuke at the end of 2022, including community names, addresses, total buildings, total households, and latitude/longitude coordinates. Using the seventh census average of 2.29 persons per household, the elderly population for each community point was estimated. These estimates were then aggregated to the street level and compared with official bulletin data, showing a high degree of accuracy.

ECFs data: Information on facility category, location, number of beds, service content, and business nature was obtained through Python crawling of the Dalian Civil Affairs Bureau official website and relevant elderly care networks.

Travel time data: Measured using the Gaode Map route planning API. To reflect travel mode diversity, walking and driving times were measured separately using the respective APIs. The process involved:

-

a.

Identifying catchment areas: Based on existing research and Dalian’s road conditions, extreme travel thresholds for the elderly (1500 m, 3000 m, 4500 m for small, medium, large facilities respectively (F. Han & Luo, 2020) were used to find communities within range of each ECF.

-

b.

Measuring point-to-point times: The shortest travel time from each community (origin) to each ECF (destination) was measured for both walking and driving modes.

-

c.

Aggregating to street level: The community-level travel times were averaged (see explanation below) to obtain representative travel times from each street to the nearest or relevant elderly care facilities.

Road network & administrative boundary data: Underlying Road network data and administrative boundaries (e.g., street polygons) were essential for spatial analysis and network distance calculations. These were sourced from the Gaode Map API and official Dalian geographic information resources.

Explanation of “Summary Average”: The phrase “summary average” referred to the process of calculating the mean travel time from communities within a street to ECFs. Specifically, for each street unit, the travel times (either walking or driving) from all constituent communities to their nearest or relevant ECFs were averaged to derive a single representative travel time value for that street. This aggregation step was necessary to align the accessibility analysis with the street-level scale used for population data and policy implementation.

Accessibility calculation

Spatial accessibility refers to the potential opportunity and ease of access to resources (Hansen, 1959), for residents in various regions, and the measurement methods are very diverse, such as the gravity modeling method, 2SFCA method and so on. In response to the shortcomings of the traditional 2SFCA method that ignores the differences in accessibility within the search area, many studies have proposed to improve the method by adding different forms of the distance decay function (Liu et al., 2022; Huang et al., 2022; Ma et al., 2023). Gaussian-2SFCA is adopted, that is, the improved 2SFCA method by adding Gaussian distance decay function, which has the advantage of moderate intensity of distance decay effect and only one parameter (Huang et al., 2022). The Gaussian-2SFCA method consists of two steps: Firstly, the resources of each facility are allocated to the demand points in the search area according to the demand point size and distance attenuation function. Secondly, the accessibility value of each demand point can be obtained by summating the resources that can be obtained by the accessible facilities within the scope of its search area, which means the average amount of potential service resources available to each demander, and the factor of facility scale level is included in the model. The specific process is divided into two steps:

Step 1

For every elderly care facility location \({\rm{j}}\), search all aging population locations (\({\rm{k}}\)) that are within a threshold travel distance \({{\rm{d}}}_{0}\) from\(\,{\rm{j}}\), thus formulating the catchment for elderly care facility location \({\rm{j}}\). Aging populations at k will be weighted using a Gaussian function (\({\rm{G}}\)). Sum up the weighted populations within the catchment for \({\rm{j}}\) as the demanders for the elderly care facility \({\rm{j}}\). \({{\rm{R}}}_{{\rm{j}}}^{{\rm{m}}}\) is the supply and demand ratio of the elderly care facility within the search threshold range which can be written as:

Where: \({\rm{m}}\) is the type of ECF, which are divided into three categories: large, medium and small;\({{\rm{S}}}_{{\rm{j}}}^{{\rm{m}}}\) is the service scale (number of beds) of elderly care facility \({\rm{j}}\) of type \({\rm{m}}\);\({{\rm{D}}}_{{\rm{k}}}\) is the demand (number of elderly population) at the community location \({\rm{k}}\);\({{\rm{d}}}_{{\rm{kj}}}\) is the transportation cost (travel distance) between community location \({\rm{k}}\) and ECF location \({\rm{j}}\) ;\({{\rm{d}}}_{0}^{{\rm{m}}}\) indicates the facility search threshold for ECF type \({\rm{m}}\);\({\rm{G}}\left({{\rm{d}}}_{{\rm{kj}}},{{\rm{d}}}_{0}^{{\rm{m}}}\right)\) is the Gaussian decay function (defined in Eq. 2).

The Gaussian decay function can be expressed as below:

Step 2

For each community (demand) location \({\rm{i}}\), search all ECFs \({\rm{j}}\) within the threshold distance \({{\rm{d}}}_{0}^{{\rm{m}}}\) from \({\rm{i}}\), thus formulating the catchment for the demand location \({\rm{i}}\). Discount each \({{\rm{R}}}_{{\rm{j}}}^{{\rm{m}}}\) within this catchment using the Gaussian function \({\rm{G}}\left({{\rm{d}}}_{{\rm{kj}}},{{\rm{d}}}_{0}^{{\rm{m}}}\right)\) based on the distance from \({\rm{i}}\) to \({\rm{j}}\). Sum up the discounted \({{\rm{R}}}_{{\rm{j}}}^{{\rm{m}}}\) values within the catchment area of \({\rm{i}}\) to obtain the spatial accessibility at population location \({\rm{i}}\) as follows:

Where: \({{\rm{A}}}_{{\rm{i}}}^{{\rm{m}}}\) denotes the accessibility of the population location \({\rm{i}}\) to the type-m ECFs;\({{\rm{A}}}_{{\rm{i}}}\) is the overall accessibility of ECFs for population location \({\rm{i}}\), which is the sum of the accessibility scores to different types (\({\rm{m}}\)) of ECFs;\({{\rm{d}}}_{{\rm{ij}}}\) is the transportation cost (travel distance) between community location \({\rm{i}}\) and ECF location \({\rm{j}}\). This replaces the incorrect \({{\rm{d}}}_{{\rm{kj}}}\) in the original Eq. 3.

The Maximal Accessibility Equality (MAE) model

Wang and Tang proposed a new location-allocation model called the Maximum Accessibility Equality (MAE) model. The spatial equity of the MAE model facility allocation is quantified as the minimization of the sum of squares of the facility variances (Wang & Tang, 2013). The MAE model represents and solves the nonlinear planning problem as a quadratic programming problem. The objective function of the MAE model is to minimize the accessibility variance, which can be expressed as:

Where \({{\rm{A}}}_{{\rm{i}}}\) denotes accessibility, calculated by Gaussian-2SFCA; \({{\rm{P}}}_{{\rm{i}}}\) is the scale of demand; \({\rm{n}}\) is the number of demand points; The decision variable to be solved is the supply variable \({{\rm{S}}}_{{\rm{j}}}\) in the accessibility calculation.

Spatial equity measurement index research is abundant. Tao’s research on the connotation of indicators shows that coefficient of variation, Gini coefficient, mean absolute deviation and Parma ratio are more suitable for the research on spatial justice optimization of public services. Therefore, two improved MAE models, coefficient of variation and mean absolute deviation, are adopted in this study. The objective optimization function of the improved CV-MAE model and MAD-MAE model can be expressed as

CV:

MAD:

Framework

Spatial equity serves as our foundational perspective, evaluating the distributive justice of elderly care resources across urban space. Within this framework, accessibility (measured via our congestion-enhanced G2SFCA method) operates as the diagnostic metric quantifying current facility equity—revealing disparities between privileged and underserved neighborhoods. The spatial optimization model (MAD-MAE) then functions as the corrective mechanism, strategically reallocating beds from over-supplied zones (e.g., Zhoushuizi Street) to high-demand areas (e.g., Ganjingzi Street) to actively improve equity outcomes. The research framework of this paper is shown in Fig. 2. Firstly, the international and domestic severe aging situation was comprehensively considered as the background of this study, and the city of Dalian, China was taken as the study area. Secondly, the research perspective of this paper is centered on “spatial equity”, which is investigated according to the logic of equity assessment and optimization. From the equity assessment phase, it can be concluded that there is currently an unbalanced status quo of elderly care resources in Dalian. Subsequently, capacity optimization of elderly care facilities (addressing the size or service capacity of facilities) based on the findings of the assessment improves the spatial equity of elderly care resources. The main innovations of this paper include the construction of a new multi-scale (community and street levels) optimization framework for the assessment of elderly care resources, a more refined research unit (community point), and an optimized research methodology.

Results and conclusion

Evaluation of supply-demand matching of ECFs

According to data from the Seventh National Population Census, Dalian has a total population of 7.45 million. The population aged 60 years and above is 1.84 million, accounting for 24.71%, while the population aged 65 years and above is 1.257 million, accounting for 16.87%. Figure 3a–c presents aging indicators at the sub-district (street) level, derived directly from the street-level data of the Seventh National Population Census. The figure indicates that the overall aging level in Dalian is high. High-value areas for aging rate are predominantly concentrated in the southern part of Dalian, with relatively small differences observed across sub-districts. Conversely, high-value areas for both the size and density (calculated based on sub-district administrative area and elderly population count) of the elderly population are primarily concentrated within Dalian’s main urban area. Consequently, the following section will focus on the main urban area of Dalian for further research and analysis.

As shown in Fig. 3d, e, the distribution trend of the supply points of ECFs and the demand points of the elderly in Dalian is basically consistent with each other, showing the structure of “dense in the east and sparse in the west”, and the coverage rate of small-scale elderly facilities in the city is higher, which is the result of the government’s attention to the elderly's demand for elderly facilities and its active promotion of the construction of ECFs in Dalian, but overall there are still problems such as unbalanced number of facilities and regional heterogeneity in the configuration level of the ECFs. This is the result of the government’s attention to the needs of the elderly and its active promotion of the construction of elderly facilities, but on the whole, there are still problems such as an imbalance in the number of facilities and regional heterogeneity in the level of ECFs.

The central city has a total elderly population of 727,445, with a concentrated and relatively even spatial distribution, and is the region with the largest elderly population in Dalian, as well as the region with the largest demand for elderly care, with 23 large-scale ECFs, 67 medium-sized ECFs, and 272 small-scale ECFs within its boundaries. Overall, the trend of matching the supply and demand of facilities at the regional level is basically the same in terms of quantity and spatial distribution, but the conditions of facility configuration need to be improved. There is a shortage of large and medium-sized ECFs in the main urban areas of Dalian, and small ECFs are mostly configured in combination with community activity centers, with poor environmental conditions and few available beds.

Comprehensive evaluation of accessibility based on 2SFCA method

The spatial accessibility of ECFs in Dalian at the community level is calculated based on the Gaussian 2SFCA method. A high score of accessibility means that the elderly in the area have a strong ability to enjoy elderly care services; on the contrary, they have a weak ability to enjoy elderly care services. Considering the travel habits and travel ability of the elderly, the distance to elderly facilities becomes an important factor for the elderly to choose elderly facilities. Therefore, combined with existing literature research, this paper divides the service radius of each level of facilities based on the limit distance of elderly people’s travel, and the service radius of small, medium and large senior care facilities are 1500 m, 3000 m and 4500 m.

To enhance the realism of the results, two distance metrics were employed in the G2SFCA calculations: 1) network-based travel distances derived using the OD Cost Matrix analysis within ArcGIS Network Analyst (representing the “traditional” supply-demand distances based on the road network), and 2) actual travel distances obtained via the Gaode Map API. The calculated accessibility results were then interpolated using the inverse-distance-weighting method to visualize spatial heterogeneity more intuitively. The accessibility scores computed for each community point were summed (aggregated) to obtain the overall accessibility value for each sub-district (street) level unit, representing the overall accessibility of ECFs at the street level (Fig. 4). Additionally, accessibility scores for different types of ECFs were calculated separately and visualized (Fig. 5).

Accessibility scores at street level

As shown in Fig. 4, the accessibility calculated using the Gaode API-derived travel distances exhibits a spatial pattern that aligns more closely with the distribution of facilities and population compared to the results based on traditional network distances. Notably, it identifies additional high-accessibility areas. Therefore, the analysis below focuses on the accessibility results derived from Gaode travel distances. Areas within sub-districts lacking ECFs are indicated as blank or 0 values in the visualization (same as below).

The spatial distribution of ECF accessibility in the study area, classified using the Natural Breaks (Jenks) method into five categories (very low, low, medium, high, very high), reveals distinct patterns:

-

1.

The most extensive very high accessibility area is distributed in the northern part of Dalian’s main urban area. While the elderly population density here is relatively low, the presence of several large-scale ECFs ensures the supply of facilities adequately meets the needs of the local elderly population, resulting in higher overall accessibility.

-

2.

Another distinct high/very high accessibility area is located in the western part of the main urban area, near the city core. This area benefits from three medium-sized ECFs, providing 575 beds, which translates to approximately 1.25 beds per elderly person in the vicinity.

-

3.

Areas classified as low/very low accessibility are predominantly distributed in the central and eastern parts of the region, encompassing Zhongshan District, Xigang District, Shahekou District, and parts of Ganjingzi District. Despite an overall ratio exceeding 2.5 beds per 100 elderly people in these districts, the distribution of facilities is dispersed, and the elderly population density is highly concentrated in specific areas. This spatial mismatch leads to lower accessibility scores when calculated using the G2SFCA method.

Accessibility measurement of different levels of ECFs

According to the Chinese national standard “Classification and evaluation of aged care institution”, ECFs in Dalian are divided into three categories according to the number of beds: large ( > 300 beds), medium (100-300 beds), and small ( < 100 beds). The number and spatial distribution of different classes of ECFs varies greatly, with some small-sized ECFs having only 4 beds, while some large-sized ECFs have as many as 1000 beds. Therefore, evaluating the accessibility of different classes of ECFs in the urban area can help to analyze the regional heterogeneity of the ECFs and to clarify the optimization of the allocation of different types of facilities in the future. Figure 5 shows the comparison of the accessibility of different classes of ECFs based on the Gaode traffic data.

As shown in Fig. 5, a quantitative comparison of the accessibility scores derived from the G2SFCA method reveals that the spatial accessibility of small ECFs is slightly higher than that of medium-sized ECFs, and significantly higher than that of large ECFs. This pattern can be attributed to several key factors related to small ECFs:

-

1.

Numerical superiority and balanced distribution: Small ECFs are far more numerous than medium and large facilities across the sub-districts (Fig. 5a), and their distribution within the region is more balanced.

-

2.

Advantages in supply and coverage: This prevalence and spatial distribution grant small ECFs an advantage in terms of bed supply accessibility and the geographic coverage (radiation scope) for the elderly population.

-

3.

Resource efficiency and flexibility: Small ECFs require less land area and capital investment compared to large facilities. Their moderate size also offers greater flexibility for future optimization of facility allocation.

-

4.

Alignment with elderly preferences: Considering the special consumption habits and traditional preferences of the elderly, the occupancy fees and staffing levels of small-scale facilities may align better with their expectations.

Regarding medium and large ECFs: While the number of medium and large facilities varies little by street (Fig. 5b, c), the accessibility of medium-sized facilities is slightly higher overall than that of large facilities. However, the variation in accessibility between streets is larger for medium-sized facilities than for large ones. Figure 6 further illustrates that the overall accessibility of ECFs (aggregated across all types) was higher in specific streets within Zhongshan District, Xigang District, and Ganjingzi District.

In the future, the Dalian government should optimize the allocation of different types of ECFs according to the current situation of the elderly population in each sub-district and the accessibility of different types of ECFs; for areas with a stable elderly population and a better economic foundation and mature development, new medium-sized and large-scale ECFs can be built appropriately to satisfy the demand for elderly care in the area; on the other hand, it is possible to improve the connectivity of transportation in some areas in order to enlarge the radiation range of the ECFs, and promote balanced development of the regional elderly care industry by improving the rationality of the layout of different levels of ECFs.

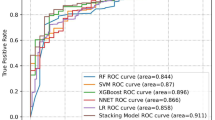

Results of layout optimization of ECFs

The PSO algorithm is used to solve the MAE model (Tao et al., 2021). PSO specifies a function to evaluate the performance of each possible solution, which is expressed as the optimal result calculated in Eq. 5. It provides an efficient method for solving optimization problems by simultaneously considering a wide range of possible solutions and moving towards the optimal solution in an evolutionary manner. Each solution is referred to as a particle, which consists of the facility size of all candidate locations. At each iteration, the performance of the current solution is evaluated by a fitness function and compared with the previous iteration. If the current solution produces better performance, the particle will be retained and the solutions in the next iteration will be determined based on the trend, which converge to the global optimal solution after a certain number of iterations. The optimized reachability distributions of the MAE-based models of CV and MAD fit well with the weighted average reachability, and the reachability of most of the cells is closer to the weighted average reachability. Among them, the optimized reachability of the MAD model has the highest fit with the weighted average reachability in the mid-value region, while the CV and MAD models are better optimized in the high-value region and low-value region (Tao et al., 2023).

Optimization results based on CV-MAE model

The optimized ratio of beds per 1000 elderly persons was classified into four tiers using the Natural Breaks method: Low, Lower-Medium, Higher-Medium, and High. Lower-Medium and Higher-Medium tiers are collectively termed “Medium” tiers (applies throughout).

Spatial allocation principle: The G2SFCA method inherently allows demand (elderly population) and supply (ECF beds) to interact across administrative boundaries, provided they fall within the facility’s service radius. Thus, a community in one sub-district may be assigned to an ECF located in another sub-district based solely on travel distance.

Pre- vs. post-optimization comparison: Before optimization, significant regional heterogeneity exists (Fig. 8a): High-tier areas are confined to Chunliu district and Xianglujiao district in the city center, while Low-tier areas dominate the northwest and south. After optimization, facility distribution becomes more balanced (Fig. 7): High-tier areas increase slightly, and some Low-tier areas shift to Higher-Medium tier.

Pre-optimization tier weights: low: 31%, medium: 62%, high: 7%. Only 18 sub-districts achieved moderately balanced (Medium) distribution.

Post-optimization tier weights: low: 21%, medium: 69%, high: 10%. Sub-districts with balanced distribution increased to 20.

Implications for spatial equity: The calculated difference between optimized and existing bed distribution (Fig. 7) reveals significant adjustments required to achieve street-scale equity:

-

1.

Areas needing facility enlargement: Bayi Road, Baiyun, Chunliu, Dalianwan, and Ganjingzi Streets.

-

2.

Areas needing downsizing: Zhoushuizi, Zhonghua Road, and Yingchengzi Streets.

Cost-Efficient adjustment strategy: Table 1 indicates geographical proximity between downsized (“downsized”) and enlarged (“enlarged”) facilities. Proximity enables cost-saving bed reallocation:

-

Surplus beds in Zhoushuizi Street → Reallocate to adjacent Chunliu Street

-

Surplus beds in Zhonghua Road Street → Reallocate to surrounding Paoya Street & Ganjingzi Street

This spatial coordination reduces relocation costs while enhancing accessibility equity.

Optimization results based on MAD-MAE model

The spatial outcomes of the MAD-MAE optimization are shown in Fig. 8 (a: before optimization; b: after optimization).

Pre- vs. post-optimization comparison

-

Before optimization:

Tier weights: low-value: 31%, medium: 62%, high-value: 7%

Sub-districts with balanced (Medium) distribution: 18

-

After MAD-MAE optimization:

Tier weights: low-value: 14%, medium: 76%, high-value: 10%

Sub-districts with balanced distribution: 22

Implications for spatial equity

The MAD-MAE model further reduces regional variability compared to CV-MAE results:

-

1.

Statistical superiority:

-

CV-MAE standard deviation: 7.5918

-

MAD-MAE standard deviation: 3.9323 (48.2% reduction)

-

2.

Theoretical rationale:

“MAD minimizes sensitivity to extreme values and better fits weighted accessibility averages” (Tao et al., 2023).

Cost-Efficient adjustment strategy

Geographical proximity enables optimal bed reallocation (Table 1):

-

Surplus beds in Zhoushuizi Street → Transfer to adjacent Chunliu Street

-

Surplus beds in Zhonghua Road Street → Transfer to Paoya Street & Ganjingzi Street

Optimization methods and strategies

The spatial distribution of ECFs in the main urban area of Dalian City is characterized by uneven distribution and low allocation of relevant supporting facilities. Combined with the requirements of the “14th Five-Year Plan” and other policy documents such as the National Plan for the Development of the Elderly Care Facility and Elderly Care System, in order to realize the fairness of the spatial distribution of ECFs, and based on the actual situation of the service capacity of different grades of ECFs, the scope of service of facilities, and the density of the elderly population, we propose various methods of optimization for the merger of the facilities that need to be optimized and retained and adjusted, and the suitable sites for the new construction.

Optimize and consolidate ECFs. Figure 9 shows different types of ECFs with overlapping service scope and low service capacity values. These ECFs not only have low service capacity but also have overlapping service scope, which is easy to cause waste of elderly beds and personnel resources, so resource reorganization can be used to merge ECFs with the same low service capacity in the overlapping area of elderly service scope, and if there is no low service capacity ECF with the same overlapping area of service scope, it can be optimized and merged with the nearby ECFs with general service capacity or high service capacity. If there are no low-capacity ECFs with the same service scope overlap area, they can be optimized and merged with nearby general-capacity ECFs or high-service-capacity ECFs, so as to avoid wasting elderly care resources.

Retention or adjustment of ECFs. ECFs located in areas with low values of accessibility and service capacity of ECFs. These facilities are located in areas with a high density of elderly population yet with low service capacity of the facilities, which cannot meet the demand for beds and staffing of the elderly population within their service area, resulting in a low level of accessibility of the facilities in the area, and the floor area, number of beds and staffing of the ECFs failing to meet the relevant standards. For such ECFs, if there is reserved land in the vicinity, the size of the facility’s footprint can be appropriately expanded to increase the number of beds; if there is no suitable land in the vicinity, the internal layout can be appropriately adapted to create a digitized elderly care home and improve the level of elderly care provision.

New construction of ECFs. In order to improve the accessibility of ECFs and promote spatial equity in the elderly care industry, new facilities should be built in accordance with local conditions, making full use of unutilized land in the area or land reserved for public facilities to build new ECFs, as is the case in areas with a high density of elderly people and low accessibility.

In view of the existing problems in the layout of ECFs in Dalian, in order to achieve spatial equity of ECFs, the optimization plan is: optimization and merger of ECFs with overlapping service scope and low service capacity value; retention and adjustment of ECFs with low accessibility to the area they are located in and low service capacity value of the facilities, and internal upgrading; and construction of new facilities in the area with high density of the elderly population and the service scope of the ECFs is not covered. At the same time, in order to achieve spatial equity and promote the rational allocation of elderly resources, the layout of ECFs should be optimized with full consideration of the consumption habits of the elderly population, their needs and the support of public service facilities related to elderly care, and attention should be paid to the connection between the elderly care industry and the urban planning of the relevant regions and the silver-hair economy, so as to make an effort to improve the level of elderly care in the region and to fully satisfy the needs of the elderly population.

Discussion

This study developed and applied two optimized MAE model, incorporating CV-MAE and MAD-MAE model, to enhance the ECFs accessibility in Dalian. Leveraging fine-grained data from the National Bureau of Statistics (2021) at the street and community level, alongside ECFs locations and capacities, the analysis employed the G2SFCA method with distance thresholds reflecting elderly travel behavior: walking distance for short trips ( ≤ 1500 m) and driving distance for medium/long trips ( > 1500 m). The optimization was solved using the PSO algorithm.Key findings are:

-

1.

Significant supply-demand mismatch: A pronounced spatial mismatch exists between the current distribution of ECF beds and the elderly population in Dalian’s main urban area, characterized by regional heterogeneity and disparities in facility size and configuration levels.

-

2.

Model effectiveness: Both CV-MAE and MAD-MAE models demonstrably improve spatial equity compared to the existing layout. The MAD-MAE model yielded slightly better results in balancing supply-demand distribution across sub-districts. Optimization led to a decrease in Low-tier areas (31% → 21%) and an increase in both Medium-tier (62% → 69%) and High-tier (7% → 10%) areas.

-

3.

Optimization strategy: Achieving maximal spatial equity requires a dual strategy:

-

1.

Decentralization & resizing: Downsizing over-supplied facilities (e.g., Zhoushuizi, Zhonghua Road, Yingchengzi Streets) and enlarging under-supplied facilities (e.g., Bayi Road, Baiyun, Chunliu, Dalianwan, Ganjingzi Streets).

-

2.

Strategic new development: Supplementing the optimized resizing with targeted construction of new ECFs in currently underserved areas, especially given Dalian’s urban space constraints and future aging trends.

-

1.

-

4.

Practical pathway: Cost-efficient adjustments can be achieved by leveraging geographical proximity. Surplus beds from downsized facilities can be strategically reallocated to nearby enlarged facilities (e.g., Zhoushuizi → Chunliu; Zhonghua Road → Paoya & Ganjingzi), reducing relocation costs while enhancing equity.

The results provide actionable policy insights for Dalian to modernize its ECF system and maximize spatial equity. The proposed optimization model and methodology, grounded in realistic travel metrics (Gaode API network distances) and tailored to facility types (service radii: 1500 m/3000 m/4500 m), demonstrate significant potential for application to other public facilities (e.g., education, healthcare) facing similar spatial equity challenges.

Limitations and Future Research:

-

Temporal scope: Reliance on 2020 census data; future demand changes (e.g., per Dalian Population Development Plan 2021–2030) were not incorporated.

-

Travel mode data: Used walking (short dist) and driving (med/long dist) distances only; public transport (bus/subway) data was not integrated. Future studies should incorporate multi-modal travel data better reflecting elderly mobility patterns.

-

Analysis unit granularity: While communities represent the finest available unit, their varying sizes and irregular shapes may introduce minor inaccuracies in very short-distance network calculations.

-

Facility siting: Optimization focused solely on resizing existing facilities within a fixed total capacity. Future work should integrate optimal siting of new facilities prior to or alongside capacity optimization.

-

G2SFCA functional attributes: Only “facility beds” served as the functional attribute in the 2SFCA for accessibility calculation. Future studies should collaborate with local health departments to obtain granular data (e.g., facility-level physician staffing, standardized service fees) to expand G2SFCA’s functional attributes, enhancing accessibility evaluation robustness.

Data availability

The processed datasets supporting the findings of this study are provided as Supplementary Materials. Raw data sources and their corresponding data types are as follows: 1. Population census data (Sixth and Seventh National Population Census of Dalian) from Dalian Municipal Bureau of Statistics (https://tjj.dl.gov.cn/); 2. ECF data (category, location, number of beds, etc.) from Dalian Civil Affairs Bureau (http://mzj.dl.gov.cn/) and relevant elderly care networks(https://www.yanglao.com.cn/); 3. Community POI data (household numbers, coordinates, etc.) from Lianjia official data service channels(https://yibin.lianjia.com/) and Anjuke official data service channels(https://anjuke.brand.anjuke.com/); 4. Administrative boundary data and road network data from Gaode Map Developer Platform(https://lbs.amap.com/) and Geospatial Data Cloud Platform(http://www.gscloud.cn/); 5. Administrative boundary data from official Dalian geographic information resource portals. 6. Dalian vector maps are sourced from Tianditu (https://www.tianditu.gov.cn/?4).

References

Cai E, Liu Y, Jing Y, Zhang L, Li J, Yin C (2017) Assessing Spatial Accessibility of Public and Private Residential Aged Care Facilities: A Case Study in Wuhan, Central China. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information 6(10):304. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi6100304

Central People’s Government of the People’s Republic of China. (2016). The Outline of the Healthy China 2030 Plan. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2016-10/25/content_5124174.htm (accessed on 21 January 2024)

Cheng Y, Rosenberg MW, Wang W, Yang L, Li H (2012) Access to residential care in Beijing, China: Making the decision to relocate to a residential care facility. Ageing and Society 32(8):1277–1299. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X11000870

Culyer AJ, Wagstaff A (1993) Equity and equality in health and health care. Journal of Health Economics 12(4):431–457. https://doi.org/10.1016/0167-6296(93)90004-X

Dadashpoor H, Rostami F, Alizadeh B (2016) Is inequality in the distribution of urban facilities inequitable? Exploring a method for identifying spatial inequity in an Iranian city. Cities 52:159–172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2015.12.007

Dai J, Menhas R (2020) Sustainable Development Goals, Sports and Physical Activity: The Localization of Health-Related Sustainable Development Goals Through Sports in China: A Narrative Review. Risk Management and Healthcare Policy ume 13:1419–1430. https://doi.org/10.2147/RMHP.S257844

Han F, Luo R (2020) Matching of Supply and Demand for Community Service-Oriented Home Care Facilities Based on Accessibility Measurement: A Case Study of Nanjing. Economic Geography 40(9):91–101. https://doi.org/10.15957/j.cnki.jjdl.2020.09.010

Hansen WG (1959) How Accessibility Shapes Land Use. Journal of the American Institute of Planners 25(2):73–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944365908978307

He H, Chen Y, Liu Y, Gu Y, Gu Y (2023) Equity of Elderly Care Facility Allocation in a Multi-Ethnic City under the Aging Background. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20(4):3291. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043291

Hemby Tyler L, Powell Robert B, Stern Marc J (2024) Availability and distribution of environmental education field trip programs for adolescent students in the U.S.: a national study of spatial accessibility. Environmental Education Research 30(2):214–234

Hluško R, Stanek R, Ďurček P (2024) Urban public transport system accessibility for different groups of residents: Case of Bratislava city. Case Studies on Transport Policy 16:101200

Huang X, Gong P, White M (2022) Study on Spatial Distribution Equilibrium of Elderly Care Facilities in Downtown Shanghai. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19(13):7929. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19137929

Iraegui E, Augusto G, Cabral P (2020) Assessing Equity in the Accessibility to Urban Green Spaces According to Different Functional Levels. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information 9(5):308. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi9050308

Joseph, AE, & Phillips, DR (1984) Accessibility and utilization: geographical perspectives on health care delivery

Li X, Wang F, Yi H (2017) A two-step approach to planning new facilities towards equal accessibility. Environment and Planning B: Urban Analytics and City Science 44(6):994–1011. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265813516657083

Liao C, Scheuer B, Dai T, Tian Y (2020) Optimizing the spatial assignment of schools to reduce both inequality of educational opportunity and potential opposition rate through introducing random mechanism into proximity-based system. Socio-Economic Planning Sciences 72: 100893. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seps.2020.100893

Liu L, Lyu H, Zhao Y, Zhou D (2022) An Improved Two-Step Floating Catchment Area (2SFCA) Method for Measuring Spatial Accessibility to Elderly Care Facilities in Xi’an, China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19(18):11465. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811465

Logan JR, Fang Y, Zhang Z (2009) Access to Housing in Urban China. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 33(4):914–935. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2427.2009.00848.x

Luo J (2014) Integrating the Huff Model and Floating Catchment Area Methods to Analyze Spatial Access to Healthcare Services. Transactions in GIS 18(3):436–448. https://doi.org/10.1111/tgis.12096

Luo J, Tian L, Luo L, Yi H, Wang F (2017) Two-Step Optimization for Spatial Accessibility Improvement: A Case Study of Health Care Planning in Rural China. BioMed Research International 2017:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/2094654

Luo W, Wang F (2003) Measures of Spatial Accessibility to Health Care in a GIS Environment: Synthesis and a Case Study in the Chicago Region. Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design 30(6):865–884. https://doi.org/10.1068/b29120

Ma J, Huang H, Liu D (2023) Influences of Spatial Accessibility and Service Capacity on the Utilization of Elderly-Care Facilities: A Case Study of the Main Urban Area of Chongqing. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20(6):4730. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20064730

Murray AT (2016) Maximal Coverage Location Problem: Impacts, Significance, and Evolution. International Regional Science Review 39(1):5–27. https://doi.org/10.1177/0160017615600222

National Bureau of Statistics (2021) The Seventh Population Census. Available online: https://www.stats.gov.cn/sj/pcsj/rkpc/d7c/ (accessed on 20 January 2024)

Ngui AN, Apparicio P (2011) Optimizing the two-step floating catchment area method for measuring spatial accessibility to medical clinics in Montreal. BMC Health Services Research 11(1):166. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-11-166

Ni J, Wang J, Rui Y, Qian T, Wang J (2015) An Enhanced Variable Two-Step Floating Catchment Area Method for Measuring Spatial Accessibility to Residential Care Facilities in Nanjing. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 12(11):14490–14504. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph121114490

Ning C, Pei H, Huang Y, Li S, Shao Y (2024) Does the Healthy China 2030 Policy Improve People’s Health? Empirical Evidence Based on the Difference-in-Differences Approach. Risk Management and Healthcare Policy ume 17:65–77. https://doi.org/10.2147/RMHP.S439581

Ogryczak W (2009) Inequality measures and equitable locations. Annals of Operations Research 167(1):61–86. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10479-007-0234-9

Sharma G, Patil GR (2021) Public transit accessibility approach to understand the equity for public healthcare services: A case study of Greater Mumbai. Journal of Transport Geography 94: 103123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2021.103123

Shavandi, H, & Mahlooji, H (2008) Fuzzy hierarchical queueing models for the location set covering problem in congested systems. Scientia Iranica, 15(3)

Talen E (1997) The Social Equity Of Urban Service Distribution: An Exploration Of Park Access In Pueblo, Colorado, And Macon, Georgia. Urban Geography 18(6):521–541. https://doi.org/10.2747/0272-3638.18.6.521

Talen E, Anselin L (1998) Assessing Spatial Equity: An Evaluation of Measures of Accessibility to Public Playgrounds. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 30(4):595–613. https://doi.org/10.1068/a300595

Tan X, Zhang Y, Shao H (2019) Healthy China 2030, a breakthrough for improving health. Global Health Promotion 26(4):96–99. https://doi.org/10.1177/1757975917743533

Tao Z, Cheng Y, Dai T, Rosenberg MW (2014) Spatial optimization of residential care facility locations in Beijing, China: Maximum equity in accessibility. International Journal of Health Geographics 13(1):33. https://doi.org/10.1186/1476-072X-13-33

Tao Z, Dai T, Song C (2023) Improving spatial equity-oriented location-allocation models of urban medical facilities. ACTA GEOGRAPHICA SINICA 78(2):474–489. https://doi.org/10.11821/dlxb202302013

Tao Z, Wang Q, Han W (2021) Towards Health Equality: Optimizing Hierarchical Healthcare Facilities towards Maximal Accessibility Equality in Shenzhen, China. Applied Sciences 11(21):10282. https://doi.org/10.3390/app112110282

Wang F (2012) Measurement, Optimization, and Impact of Health Care Accessibility: A Methodological Review. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 102(5):1104–1112. https://doi.org/10.1080/00045608.2012.657146

Wang F, Fu C, Shi X (2016) Planning towards maximum equality in accessibility of NCI Cancer Centers in the US. In Spatial Analysis in Health Geography (pp. 261–274). Routledge

Wang F, Tang Q (2013) Planning toward Equal Accessibility to Services: A Quadratic Programming Approach. Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design 40(2):195–212. https://doi.org/10.1068/b37096

Wang S, Ma S (2018) Efficient methods for a bi-objective nursing home location and allocation problem: A case study. Applied Soft Computing 65:280–291. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asoc.2018.01.014

World Health Organization (2022) Aging and Health. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageingand-health (accessed on 1 January 2024)

World Health Organization (2021) WHO’s work on the UN Decade of Healthy Ageing (2021–2030). Available online: https://www.who.int/zh/initiatives/decade-of-healthy-ageing (accessed on 1 January 2024)

Wu F, He S, Webster C (2010) Path Dependency and the Neighbourhood Effect: Urban Poverty in Impoverished Neighbourhoods in Chinese Cities. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 42(1):134–152. https://doi.org/10.1068/a4264

Wu P, Xu D, Cui N, Li X, Liu Y (2025) Study on the Accessibility of Urban Parks Within the Framework of Kunming’s 15-Min Living Circle. Land 14(5):933–933

Xiao Y, Wang Z, Li Z, Tang Z (2017) An assessment of urban park access in Shanghai – Implications for the social equity in urban China. Landscape and Urban Planning 157:383–393. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2016.08.007

Zhao L (2023) China’s aging population: A review of living arrangement, intergenerational support, and wellbeing. Health Care Science 2(5):317–327. https://doi.org/10.1002/hcs2.64

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge funding from the Young Scientists Fund of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (41701123) and the Special Fund for Basic Scientific Research Business Expenses of Liaoning Provincial Universities (LJ112410165047).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, GL and PD; methodology, GL; software, GL; validation, LW and PD; formal analysis, GL; investigation, GL; resources, GL; data curation, GL and YJ; writing—original draft preparation, GL; writing—review & editing, GL, LW, PD and YJ ; visualization, GL; supervision, LW and PD; funding acquisition, PD. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical statements

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

The informed consent was irrelevant as the research did not include any human participants.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lu, G., Wang, L., Jiao, Y. et al. Evaluation and optimization of spatial equity in elderly care facilities: a case study of Dalian, China. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 13, 168 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-06468-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-06468-2