Abstract

The extreme cooling of the Tibetan Plateau (TP) during the boreal winter typically poses threats to the local environment and people’s safety, and it is usually attributed to internal climate variability. Here we demonstrate that the five recent large tropical volcanic eruptions since 1880 have caused an average extreme cooling of up to −0.80 K on the TP in observations during the first boreal winter following the eruptions. This cooling effect is much larger than the global average terrestrial cooling of −0.30 K after the eruptions. The multi-model ensemble mean (MME) of the Atmospheric Model Intercomparison Project (AMIP) runs from Phase 6 of the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project (CMIP6), in which realistic sea surface temperatures (SST) were specified, can simulate an extreme TP cooling response of up to −0.79 K, which is much larger than the direct aerosol cooling of −0.36 K simulated by the historical runs. The positive North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO) anomaly during the post-eruption winter after the eruptions plays a key role in amplifying the TP cooling through atmospheric teleconnection, which overwhelms the warming response associated with the frequently occurring El Niños. The results from this study provide a perspective on the potential contribution of volcanic activity or stratospheric sulfur injection scenarios to specific TP cooling.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Despite experiencing a significant warming trend1,2,3, the TP, known as the “Third Pole” and serving as an “Asian water tower”, is still frequently affected by extreme winter cooling. For instance, the record-breaking low-temperature disaster combined with heavy snow in January-February 2019 in Yushu, northeastern TP caused the deaths of 53,000 livestock, resulting in a total loss of more than 12 million over the whole TP in the last 60 years4.

The change in surface air temperature (SAT) over the TP has typically been attributed to internal climate variability. Factors such as central-Pacific El Niño warming5, positive Arctic Oscillation6, and positive Indian Ocean dipole7,8 have been shown to induce increased snowfall and lower SAT over the TP. The SAT over the TP has also been influenced by external forcing. Anthropogenic forcing has caused a much larger increasing trend in TP SAT than the global warming trend6,9. The presence of black aerosols is also believed to contribute to TP warming by reducing albedo10,11.

Volcanic eruption is one of the major natural forcing in Earth’s climate variability, which can erupt sulfur gas into the stratosphere to form sulfur aerosol12. The stratospheric volcanic aerosol can last for about 2 years, and result in signiciant global cooling 2-3 years after the eruption by reflecting solar inrradiance12,13,14,15. It has been argued that the global cooling caused by the 1991 Pinatubo eruption reached approximately 0.5 K16.

In response to the direct cooling induced by volcanic activity, the climate typically exhibits delayed processes across different time scales. The volcanic eruption can trigger intraseasonal variability17, increase the likelihood of El Niño18,19,20, force the negative phase of Atlantic multi-decadal variability21,22,23, and initiate cold phases, such as the Little Ice Age on a centennial time scale24. On the interannual time scale, tropical eruptions can also induce the positive phase of the NAO or Arctic Oscillation25,26. It is not clear whether volcanoes can affect TP SAT through these delayed processes.

This study aims to explore the changes in TP SAT induced by tropical volcanic eruptions through both observational and simulation analyses (see Methods). The primary focus will be on the direct and delayed responses of TP SAT to these eruptions. This research is beneficial for gaining a comprehensive understanding of TP SAT variability and, more importantly, for enhancing the prediction of the potential response of TP SAT to volcanic eruptions, which could have implications for the safety of local environment and property.

Results

Observed TP cooling in the first winter after eruptions

During the last century (Fig. 1a), the TP has experienced a significant warming trend of 0.13 K/decade during the boreal winter, which is consistent with previous observations9. A drop in TP SAT, however, is observed after each of the five recent large tropical eruptions, which calls for further investigation into the volcanic cooling effect on the TP.

a Boreal-winter (DJF) TP SAT (K) from 1880 to 2020 in the observation of GISTEMP. Red dots mark the eruption years of five recent large tropical eruptions, i.e., 1883 Krakatau, 1902 Santa Maria, 1963 Agung, 1982 El Chichón, and 1991 Pinatubo. b Composite monthly TP SAT anomaly (dashed blue line, K) and global-mean land SAT anomaly (dashed dark line, K) with respect to the five years preceding the five eruptions in GISTEMP. 3-month moving average is shown. Solid lines denote anomalies significant at the 95% confidence level. “0” denote the eruption year, and “−1/ + 1” one year before/after the eruption. The blue and gray horizontal dashed lines denote standart deviation of winter TP SAT anomaly and global land SAT anomaly, respectively. c Composite SAT anomaly (contour, K) in the first winter after the five tropical eruptions in GISTEMP. Slash denotes SAT anomaly significant at the 95% confidence level. Contour interval is 0.1 K. Aslo shown is the composite SAT anomaly (dots with color, K) for 1982 and 1991 eruptions in Chinese Meteorology Administration (CMA) stationary observation. The biggest dot denote Qinhai-Henan station with a maximum cooling of −3.8 K. The areas of the TP with altitude above 2500 m are outlined by purple lines.

Figure 1b compares the composite responses in global mean and TP SAT for the five most recent large tropical eruptions. Substantial global cooling is observed from spring in the second year after tropical eruptions, persisting until the end of the third year. This is consistent with previous studies that have shown large volcanic eruptions causing significant global surface cooling, which typically lasts for three years27,28,29,30,31. The composite global-mean land SAT drops by a peak of −0.30 K in the second winter. Significant cooling in the TP, however, is observed in the first winter after eruptions, with the composite TP SAT anomaly dropping by about −0.80 K. The TP SAT returns to align with the global average after this winter. This TP cooling is much larger than the global-mean land cooling of −0.30 K, and it also exceeds the interannual variability of TP SAT, represented by one standard deviation of winter TP SAT, demonstrating an extreme regional response to tropical eruptions.

No significant global-mean cooling is observed in the eruption year, and even a small positive, albeit not significant, global-mean SAT anomaly is observed in the first winter after eruptions. This finding is consistent with previous observations32, which suggests that the occurrence of an El Niño event may have counteracted the aerosol-induced global cooling.

During the first winter after eruptions (Fig. 1c), the entire TP displays a significant negative SAT anomaly, with its cooling center reaching below −1.20 K over the eastern TP. The cooling in the eastern TP is much more pronounced for the 1982 El Chichón and 1991 Pinatubo eruptions, especially when Chinese Meteorology Administration (CMA) stationary observations are available. For these two eruptions, the cooling can reach as low as −2 K at 16 out of the 62 available stations, with the maximum cooling occurring at the Qinhai-Henan station reaching −3.80 K. There are only seven stations located west of 90oE. The cooling observed at these stations is much weaker compared to that over the eastern TP. In fact, the westernmost station, Shiquan River station, even experiences a slight warming response, although it is not statistically significant. This extreme cooling is also observed in the high-quality gridded datasets (Fig. 2), i.e., the CN05.1 dataset33 and the China Meteorological Forcing Dataset (CMFD) dataset34 (see Methods). Both the grid and station datasets consistently demonstrate that extreme cooling occurs over the eastern TP during the first boreal winter following the 1982 and 1991 volcanic eruptions.

Aerosol and circulation-induced cooling

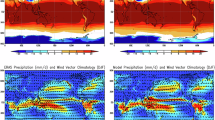

To separate the role of direct aerosol forcing and delayed climate response in the TP cooling after tropical eruptions, historical runs with free air-sea coupling and AMIP runs using observed SST forcing from CMIP6 are studied. In the MME of the historical run (Fig. 3a), a global cooling pattern is simulated during the winter following the two recent tropical eruptions, with the exception of warming observed from the North Atlantic to the Arctic region. Most continents exhibit a consistent cooling response, and the TP does not show a significantly larger response compared to other regions. The circulation change, as represented by the anomaly in 500 hPa geopotential height, is relatively weak, and the Eurasian continent is influenced by a uniform low-pressure anomaly. The composite analysis of all five recent tropical eruptions also reveals similar results (not shown).

a Composite SAT anomaly (shading; K) and 200 hPa geopotential height anomaly (contour; m) with respect to the five preceding years during the first boreal winter after 1982 and 1991 eruptions for the MME of historical runs. Stippling indicates temperature anomalies significant at the 95% confidence level. Solid and dashed contours denote positive and negative anomalies, respectively, and contour interval is 10 m. Purple lines corver the TP with altitude above 2500 m. The averaged SAT anomalies over the TP are listed in the upper right corner. b Same as (a) except for the AMIP runs.

In the AMIP run where the observed SSTs were used as the boundary condition (Fig. 3b), both the Aleutian low and Siberian high are strengthened, leading to the occurrence of northeasterly wind anomalies over the TP. This results in a greater cooling effect on the TP compared to the historical run, demonstrating the delayed response of TP SAT to tropical eruptions.

An El Niño-like teleconnection pattern in tropical SAT is observed in the AMIP run. This pattern is associated with warming in the equatorial eastern Pacific and leads to the activation of a strong Pacific-North American teleconnection in the upper troposphere. As a result, North America experiences significant warming, while Mexico undergoes cooling. However, in the historical run, no El Niño is simulated (Fig. 3a). Observationally, four El Niños were recorded in the first boreal winter following these five volcanic eruptions32,35, while the CMIP6 historical run fails to reproduce this El Niño response after eruptions36.

The comparison between the historical run and the AMIP run seems to suggest that the occurrence of El Niño leads to the intensified cooling of the TP after tropical eruptions, with temperatures dropping from −0.36 K to −0.79 K (Fig. 3). However, the winter cooling of the TP is statistically associated with a La Niña event rather than an El Niño event in the observations (Fig. 4a). This implies that El Niño is not the reason for the different TP cooling in AMIP and historical runs, and there are other boundary forcings that contribute to the extreme TP cooling following volcanic eruptions.

a Regressed boreal-winter SST anomaly (shading, K) onto the negative TP winter SAT anomaly from 1880-2020. Stippling indicates anomalies significant at the 95% confidence level. b Difference of composite SAT (K) in the MME between AMIP and historical runs for boreal winters of 1982 and 1991. Dark boxes denote the Niño3.4 and North Atlantic regions. The NAO index is defined by the SAT difference between the lower and upper boxes over the North Atlantic regions.

Role of NAO on extreme TP cooling

Another notable distinction in the boundary conditions between the AMIP and historical runs for the 1982 and 1991 events is the SST pattern over the North Atlantic region (Fig. 4b). Compared to the historical run, a dipole structure in North Atlantic SST is observed in the AMIP run, characterized by a positive anomaly over the North Atlantic around 40°-50°N and negative anomalies over the Davis Strait, resembling the positive NAO anomaly.

The NAO index can be measured by this dipole SST structure, specifically, the difference in SST between the Davis Strait regions and the North Atlantic region. A positive NAO index indicates colder temperatures in the Davis Strait region. The positive NAO index or Davis Strait cooling is quite significant in the AMIP run (Fig. 3b), while it is relatively weak in the historical run (Fig. 3a). In the observations (Fig. 4a), the positive NAO index is also observed in association with TP cooling, indicating that it is the positive NAO response that triggers the extreme TP cooling after tropical volcanic eruptions.

In observations, the NAO is typically negatively correlated with El Niño events. This negative correlation is also evident in Fig. 5a, where the North Atlantic region shows a negative NAO index when Davis Strait is warm during an El Niño winter. However, this relationship is reversed in the presence of tropical eruptions37, and the El Niño and positive NAO anomaly will occur simultaneously (Fig. 3b).

a Composite SAT anomaly (shading; K) and 500 hPa geopotential height anomaly (contour; m), with respect to the five preceding years, for the winters with Niño3.4 index above one standard deviation in the MME of AMIP run from 1979-2014. Purple lines corver the TP with altitude above 2500 m. Stippling indicates temperature anomalies significant at the 95% confidence level. b Same as in a except for the winters with NAO index above one standard deviation.

To confirm the role of the positive NAO response in cooling the TP, we compare the impacts of El Niño and NAO on the Northern Hemispheric climate (Fig. 5). In the AMIP run, an El Niño event displays a strong Pacific-North American teleconnection, resulting in positive SAT anomalies over most Northern Hemispheric land areas, except for the southern part of the United States and northern Eurasia (Fig. 5a). This suggests that the cooling effect on the TP after tropical eruptions cannot be attributable to the El Niño phenomenon. During a positive NAO winter (Fig. 5b), however, the AMIP run is able to simulate a NAO-like high-latitude teleconnection, in which high and low-pressure anomalies control North and South Eurasia, respectively38. A significant negative SAT anomaly is simulated over the TP, accompanied by a positive SAT anomaly over North Eurasia. These results indicate that although El Niño and positive NAO occur simultaneously during the post-eruption winter, the mid-to-high latitude teleconnection is predominantly influenced by the positive NAO.

Relative roles of direct aerosol forcing and delayed climate forcing

The contribution of direct aerosol forcing and delayed climate forcing to the extreme winter cooling over the TP can be linearly quantified by comparing the historical and AMIP runs. For the 1982 and 1991 eruptions, the total extreme TP cooling, including both direct and delayed forcing in the AMIP runs, is approximately −0.79 K (Fig. 3b). The cooling induced by direct aerosol forcing, represented by the MME of historical runs (Fig. 3a), is −0.36 K, which accounts for 46% of the total cooling.

The cooling over the TP induced by the NAO can be estimated by compositing the SAT anomaly with respect to the large positive NAO anomalies in the AMIP runs from 1979-2005 (Fig. 5b). Then, it can be multiplied by the ratio of the average NAO values in 1982 and 1991 (Fig. 3b) to the average of all these large NAO anomalies from Fig. 5b. The cooling induced by the NAO after the eruptions is approximately −0.57 K, accounting for about 72% of the total cooling. The nonlinear feedback between NAO and El Niño, as well as other unidentified delayed processes, may contribute to −18% of the extreme TP cooling after tropical eruptions.

Discussion

As of now, the question of whether tropical eruptions can trigger positive NAO and El Niño anomalies remains open. In observations, four out of the five recent tropical eruptions were followed by a positive NAO and an El Niño in the first winter, with the exception being no positive NAO after the 1963 Mt Agung eruption and no El Niño after the 1883 Krakatau eruption. Paleoclimate analysis, including more tropical eruptions during last millennium, has also revealed that tropical volcanic eruptions could induce positive NAO anomalies and associated European warming39, as well as increase the likelihood of El Niño18,19,20. A tropical volcanic eruption tends to warm the lower tropical stratosphere through the absorption of incoming near-infrared and upwelling longwave radiation, while cooling the polar stratosphere through the depletion of ozone. This results in an increased meridional temperature gradient and a strengthening of the polar vortex, leading to a positive NAO12,39. The tropical eruption also triggers an El Niño by cooling the African continent and suppressing the African monsoon and equaotiral westerly anomalies35,39,40,41. Both proxy data and simulation also indicate that the positive NAO and El Niño following tropical eruptin are indistinguishable from internal variability42,43,44.

In conclusion, this study reveals a significant cooling response over the TP following large tropical volcanic eruptions during the first winter after the eruption. The average decrease in SAT over the TP can reach -0.80 K for the five most recent tropical eruptions, and −1.30 K for the last two eruptions in 1982 and 1991 when stationary observation is available. Based on the MME analysis from CMIP6, the extreme cooling observed over the eastern TP can be mainly attributed to two factors: the direct aerosol cooling effect and the delayed processes, particularly the presence of positive NAO anomalies rather than the El Niño response. The direct cooling effect and the influence of the NAO contribute to 46% and 72% of the cooling, respectively, while the remaining nonlinear or other unidentified delayed processes exhibit negative feedback.

The results obtained from this study highlight the significant role and intricate nature of delayed processes, such as NAO and El Niño, providing valuable insights into the potential impact of volcanic eruptions on the climate and environment of the TP. Accurate simulation of these delayed processes is crucial for predicting regional climate change in the event of potential future volcanic eruptions45, nuclear war scenarios32,46 or stratospheric sulfur injection scenarios47.

Methods

Observation data

The daily mean temperature data used in this study were derived from gauge observations spanning the period of 1951-2020. These observations were obtained from 824 national ground meteorological stations in China and underwent rigorous quality control48. These gauge observations were utilized to investigate the SAT response over the TP to volcanic eruptions. Additionally, we incorporated long-term monthly global temperature data from the NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies Surface Temperature Analysis (GISTEMP v4), which employed a spatial smoothing technique with a scale of 1200 km and covers the time period from 1880 to 202049. Two high-quality gridded SAT datasets were also used. The monthly SAT of CN05.1 with a horizontal resolution of 0.25°×0.25° was based on the observations of more than 2416 Chinese surface meteorological stations and was gridded by interpolation using the anomaly approximation method33. The CMFD, the first high spatial-temporal resolution gridded near-surface meteorological dataset developed specifically for studies of land surface processes in China, was created through the fusion of remote sensing products, reanalysis datasets, and in-situ station data34. For the analysis of SSTs, we used monthly data from the Extended Reconstructed Sea Surface Temperature dataset version 550, which cover the period from 1854 to 2017 and has a spatial resolution of 2° × 2°.

Model simulations

The month mean SAT and 200 hPa geopotential height data from 32 earth system models participating in CMIP6 were utilized in this study51. These models include results from both historical and AMIP experiments. The historical experiment focuses on simulations under historical climate forcing, specifically covering the period from 1850 to 2014 in CMIP6. It aims to capture the response of the Earth’s climate system to natural and anthropogenic forcings during this time period. On the other hand, the AMIP experiment is one of the four baseline Diagnostic, Evaluation, and Characterization of Klima (DECK) experiments in CMIP6. In AMIP, SST and sea ice conditions are prescribed from observations, allowing for the evaluation of the atmospheric and land components of each model under the constraint of observed ocean conditions.

The 32 models used in the AMIP cover the period from 1979 to 2014 and incorporate observed SSTs and sea ice data for the AMIP runs. Both the historical and AMIP runs include simulations forced by both anthropogenic and natural forcings, including the five major tropical eruptions in the historical runs and the more recent eruptions of El Chichón in 1982 and Pinatubo in 1991 in the AMIP runs. For this study, a total of 126 available ensemble members from the historical runs and 120 available ensemble members from the AMIP runs were considered for the 32 models. Table 1 presents the detailed information of the models used in this study. The temporal resolution of the model output is monthly.

The cooling cased by five tropical volcanic eruptions

Five large tropical volcanic eruptions occurred during 1880–2020. This paper chooses these five volcanic eruptions with a significant injection of sulfuric aerosol in the tropical stratosphere: Pinatubo in June 1991, El Chichón in April 1982, Mt Agung in March 1963, Santa María in October 1902 and Krakatau in August 1883. Details of these five eruption are listed in Table 2.

In this study, we adopted the methodology previously used in a similar research article exploring the impact of volcanic eruptions on global temperature35. First, we eliminated the long-term linear trend from the data. Superposed epoch analysis (SEA) was employed to analyze the SAT responses to the selected tropical volcanic eruptions52. To isolate the climate responses specifically attributed to the eruptions from the background noise, we removed the climatological annual cycle of the five years preceding each eruption to obtain the anomalies. An 11-year window, spanning 5 years before and after each eruption, was used for the SEA analysis. A significant test at the 95% confidence level was conducted using the bootstrapped resampling method with 10,000 random draws from the entire studied period, assuming no correlation between volcanic eruptions and other climate variations18.

Since the AMIP runs began in 1979, we utilized the average of climatology from the three years preceding the 1982 El Chichón eruption for analysis. When calculating the MME, we first computed the average among the ensemble members within each model to ensure that all models were given equal weight in the analysis. Alternatively, we also obtained similar results by directly averaging across ensemble members of all models without considering model bias.

Data availability

All data used in this study were obtained from publicly available sources. The volcanic forcing data are available from Gao et al. (2008) at http://climate.envsci.rutgers.edu/IVI2/. The Global Precipitation Climatology Centre’s (GPCC) monthly land precipitation dataset for defining the monsoon region is available from Schneider et al. (2016) at https://rda.ucar.edu/datasets/ds496.0/. The CN05.1 data can be download at https://ccrc.iap.ac.cn/resource/detail?id=228/. The CMED data can be download at https://poles.tpdc.ac.cn/en/data/8028b944-daaa-4511-8769-965612652c49/. All the model data utilized in this research can be downloaded from the CMIP website: http://esgf-node.llnl.gov/.

Code availability

Codes for creating the figures and analysis were written in NCAR Command Language Version 6.6.2. and are available from the corresponding author upon a reasonable request.

References

Immerzeel, W. W. et al. Importance and vulnerability of the world’s water towers. Nature 577, 364–369 (2020).

Huang, J. et al. Global climate impacts of land‐surface and atmospheric processes over the Tibetan Plateau. Rev. Geophys. 61, e2022RG000771 (2023).

Yao, T. et al. The imbalance of the Asian water tower. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 3, 618–632 (2022).

Wen, J. H. et al. The Cryospheric Disaster 19–35 (Science Press, 2020).

Shaman, J. & Tziperman, E. The effect of enso on Tibetan Plateau snow depth: a stationary wave teleconnection mechanism and implications for the South Asian Monsoons. J. Clim. 18, 2067–2079 (2005).

You, Q. et al. Warming amplification over the arctic pole and third pole: trends, mechanisms and consequences. Earth Sci. Rev. 217, 103625 (2021).

Yuan, C. X., Tozuka, T., Miyasaka, T. & Yamagata, T. Respective Influences of Iod and Enso on the Tibetan Snow Cover in Early Winter. Clim. Dyn. 33, 509–520 (2009).

Yuan, C. X., Tozuka, T. & Yamagata, T. Iod influence on the early winter Tibetan Plateau snow cover: diagnostic analyses and an Agcm simulation. Clim. Dyn. 39, 1643–1660 (2012).

Duan, A. M. et al. Sea ice loss of the Barents-Kara Sea enhances the winter warming over the Tibetan Plateau. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 5, 1 (2022).

Xu, Y., Ramanathan, V. & Washington, W. M. Observed high-altitude warming and snow cover retreat over Tibet and the Himalayas enhanced by black carbon aerosols. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 16, 1303–1315 (2016).

Jiang, Y. Q. et al. Anthropogenic aerosol effects on east asian winter monsoon: the role of black carbon-induced Tibetan Plateau warming. J. Geophys. Res.: Atmos. 122, 5883–5902 (2017).

Robock, A. Volcanic eruptions and climate. Rev. Geophys. 38, 191–219 (2000).

Timmreck, C. et al. Limited temperature response to the very large AD 1258 volcanic eruption. Geophys. Res. Lett. 36, L21708 (2009).

Schneider, D. P., Ammann, C. M., Otto-Bliesner, B. L. & Kaufman, D. S. Climate response to large, high-latitude and low-latitude volcanic eruptions in the Community Climate System Model. J. Geophys. Res.: Atmos. 114, D15101 (2009).

Trenberth, K. E. & Dai, A. Effects of Mount Pinatubo volcanic eruption on the hydrological cycle as an analog of geoengineering. Geophys. Res. Lett. 34, L15702 (2007).

Douglass, D. H., Knox, R. S., Pearson, B. D. & Clark, A. Thermocline flux exchange during the pinatubo event. Geophys. Res. Lett. 33, L19711 (2006).

Xing, C. & Liu, F. Mount Pinatubo eruption caused the major East China flood in 1991: Impact of volcanic eruptions on intra-seasonal variability. Innov. Geosci. 1, 100032 (2023).

Adams, J. B., Mann, M. E. & Ammann, C. M. Proxy evidence for an El Nino-like response to volcanic forcing. Nature 426, 274–278 (2003).

Liu, F. et al. Divergent El Nio responses to volcanic eruptions at different latitudes over the past millennium. Clim. Dyn. 50, 3799–3812 (2018).

Liu, F. et al. Tropical volcanism enhanced the east Asian summer monsoon during the last millennium. Nat. Commun. 13, 3429 (2022).

Otterå, O. et al. External forcing as a metronome for Atlantic multidecadal variability. Nat. Geosci. 3, 688–694 (2010).

Clement, A. et al. The Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation without a role for ocean circulation. Science 350, 320–324 (2015).

Mann, M. E. et al. Multidecadal climate oscillations during the past millennium driven by volcanic forcing. Science 371, 1014–1019 (2021).

Miller, G. H. et al. Abrupt onset of the Little Ice Age triggered by volcanism and sustained by sea-ice/ocean feedbacks. Geophys. Res. Lett. 39, L02708 (2012).

Graf, H. F., Zanchettin, D., Timmreck, C. & Bittner, M. Observational constraints on the tropospheric and near-surface winter signature of the Northern Hemisphere stratospheric polar vortex. Clim. Dyn. 43, 3245–3266 (2014).

Perlwitz, J. & Graf, H.-F. The statistical connection between tropospheric and stratospheric circulation of the Northern Hemisphere in winter. J. Clim. 8, 2281–2295 (1995).

Crowley, T. J. Causes of climate change over the past 1000 years. Science 289, 270–277 (2000).

Hegerl, G. C., Crowley, T. J., Baum, S. K., Kim, K. Y. & Hyde, W. T. Detection of volcanic, solar and greenhouse gas signals in paleo-reconstructions of Northern Hemispheric temperature. Geophys. Res. Lett. 30, 1242 (2003).

Mann, M., Bradley, R. & Hughes, M. Global-scale temperature patterns and climate forcing over the past six centuries. Nature 392, 779–787 (1998).

Sear, C. et al. Global surface-temperature responses to major volcanic eruptions. Nature 330, 365–367 (1987).

Timmreck, C. Modeling the climatic effects of large explosive volcanic eruptions. Wires Clim. Change 3, 545–564 (2012).

Xing, C. et al. Boreal winter surface air temperature responses to large tropical volcanic eruptions in CMIP5 models. J. Clim. 33, 2407–2426 (2020).

Wu, J. & Gao, X. J. A gridded daily observation dataset over China region and comparison with the other datasets (in Chinese). Chin. J. Geophys. 56, 1102–1111 (2013).

He, J. et al. The first high-resolution meteorological forcing dataset for land process studies over China. Sci. Data 7, 25 (2020).

Khodri, M. et al. Tropical explosive volcanic eruptions can trigger El Nino by cooling tropical Africa. Nat. Commun. 8, 778 (2017).

Liu, F. et al. Could the recent Taal Volcano eruption trigger an El Nino and lead to eurasian warming? Adv. Atmos. Sci. 37, 663–670 (2020).

Brönnimann, S. Impact of El Niño–Southern Oscillation on European climate. Rev. Geophys. 43, RG3003 (2007).

Fischer, E. M. et al. European climate response to tropical volcanic eruptions over the last half millennium. Geophys. Res. Lett. 34, L05707 (2007).

Stenchikov, G. et al. Arctic Oscillation response to the 1991 Mount Pinatubo eruption: effects of volcanic aerosols and ozone depletion. J. Geophys. Res.: Atmospheres 107, 21–28 (2002).

Liu, F. et al. Relative roles of land and ocean cooling in triggering an El Niño following tropical volcanic eruptions. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2022GL100609 (2022).

Pausata, F. S. R., Zhao, Y., Zanchettin, D., Caballero, R. & Battisti, D. S. Revisiting the mechanisms of ENSO response to tropical volcanic eruptions. Geophys. Res. Lett. 50, e2022GL102183 (2023).

Polvani, L. M. & Camargo, S. J. Scant evidence for a volcanically forced winter warming over Eurasia following the Krakatau eruption of August 1883. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 20, 13687–13700 (2020).

DallaSanta, Kevin & Polvani, L. M. Volcanic stratospheric injections up to 160 Tg (S) yield a Eurasian winter warming indistinguishable from internal variability. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 22, 8843–8862 (2022).

Dee, S. et al. No consistent ENSO response to volcanic forcing over the last millennium. Science 367, 1477–1481 (2020).

Zanchettin, D. et al. The Model Intercomparison Project on the climatic response to Volcanic forcing (VolMIP): Experimental design and forcing input data for CMIP6. Geosci. Model Dev. 9, 2701–2719 (2016).

Coupe, J. et al. Nuclear Niño response observed in simulations of nuclear war scenarios. Commun. Earth Environ. 2, 18 (2021).

Niemeier, U. & Tilmes, S. Sulfur injections for a cooler planet. Science 357, 246–248 (2017).

Cao, L., Zhu, Y. N., Tang, G. L., Yuan, F. & Yan, Z. Climatic warming in China according to a homogenized data set from 2419 stations. Int. J. Climatol. 36, 4384–4392 (2016).

Lenssen, N. J. L. et al. Improvements in the Gistemp uncertainty model. J. Geophys. Res.: Atmos. 124, 6307–6326 (2019).

Huang, B. et al. Extended reconstructed sea surface temperature, version 5 (ERSSTv5): upgrades, validations, and intercomparisons. J. Clim. 30, 8179–8205 (2017).

Eyring, V. et al. Overview of the coupled model intercomparison project phase 6 (CMIP6) experimental design and organization. Geosci. Model Dev. 9, 1937–1958 (2016).

Haurwitz, M. W. & Brier, G. W. A critique of the superposed epoch analysis method: its application to solar–weather relations. Mon. Wea. Rev. 109, 2074–2079 (1981).

Acknowledgements

The work was supported by the Second Tibetan Plateau Scientific Expedition and Research Program (2019QZKK0103), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (U21A6001, 41875092, 42175173, 42175061), and Project supported by Innovation Group Project of Southern Marine Science and Engineering Guangdong Laboratory (Zhuhai) (No. SML2022006).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.Z., F.L., and W.D. conceived, drafted the papter, and supervised the study. All co-authors contributed to computation and figure plotting, drafting and revising the manuscrtipt, or discussion of results.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhu, X., Ji, Z., Liu, F. et al. Extreme Tibetan Plateau cooling caused by tropical volcanism. npj Clim Atmos Sci 7, 122 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-024-00672-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-024-00672-8

This article is cited by

-

Volcanic eruptions disrupt ENSO teleconnections with land summer temperature

Nature Communications (2025)

-

Response of Decadal Droughts on the Mongolian Plateau to External Forcings and Internal Variability over the Last Millennium

Advances in Atmospheric Sciences (2025)

-

Impact of major tropical volcanic eruptions on air temperatures in the Middle East

Earth Science Informatics (2025)