Abstract

Focusing on the anthropogenic aerosols effects on the East Asian Summer Monsoon (EASM) progression, we found that aerosols delay the northward progression of EASM by one pentad in the south of the middle-lower reaches of the Yangtze River (PD1: pentads 25-35) and the North-Northeast China (PD3: pentads 38-42). However, aerosols have minimal impact on the seasonal march of EASM over the Yangtze-Huai River basin (PD2: pentads 36-37). In PD1 and PD3, aerosols reduce sea-land temperature differences. Also, a southward shift in the westerly jet causing lower-level north winds, which weakens the EASM in PD3. The delayed EASM progress shows its weakness in PD1 and PD3. While in PD2, EASM intensity weakens without affecting its northward progression. Aerosols, though affecting the position and intensity of Western Pacific Subtropical High, minimally influence its northward movement speed, hence no effect on the seasonal march of EASM in PD2.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

East Asia is widely recognized for its distinct monsoon climate, characterized by significant seasonal differences between the East Asian continent and the western Pacific Ocean1,2. Positioned on the East Asian continent with its eastern border adjacent to the western Pacific Ocean, China experiences substantial influence from the East Asian summer monsoon (EASM). Precipitation patterns across the region generally align with the direction of the EASM, progressing from south to north. EASM-induced precipitation accounts for approximately 40% of the annual precipitation in South China and contributes to 60-70% of the annual precipitation in North China3. The variability of the EASM holds direct implications for various societal sectors, such as regional agriculture, flood and drought occurrences, and water resource management4,5.

Numerous investigations have highlighted that during the latter half of the 20th century, the EASM circulation exhibited a discernible weakening, featured by a reduction in the sea-land thermal difference, a weakening in surface southwesterly wind, and southward shift of Asian subtropical westerly jet stream (ASWJ)6,7,8. The observed weakening of the EASM circulation results from combination of internal variabilities and external forcings. Among them, the shift of Pacific Decadal Oscillation and El Niño-Southern Oscillation on interannual and interdecadal timescales are recognized as crucial internal variability models within the climate system, serving as influential forcing mechanisms9.

It has been observed that aerosols play a role in diminishing the strength of the EASM10,11. Anthropogenic aerosol emissions represent a significant category of pollutants in Asia12,13. The interactions of anthropogenic aerosols with clouds and radiation have profound implications for both the Asian monsoon and the global climate system. These interactions play a crucial role in modifying the energy balance of the Earth-atmosphere system14,15,16. Aerosols exhibit distinct characteristics, with scattering aerosols like sulphates diminishing ground-reaching solar radiation through scattering, resulting in a surface temperature decrease17,18,19. As most anthropogenic aerosols accumulate over land, the cooling effect on land surfaces is more significant than in marine regions, resulting in a reduction in the summer temperature difference between land and sea. On the other hand, absorbing aerosols not only scatter but also absorb solar radiation, contributing to tropospheric atmospheric warming20,21. The direct radiative impact of aerosols alters circulation characteristics by influencing energy exchange between the Earth’s surface and the atmosphere22,23,24. Consequently, aerosols reduce incoming solar radiation at the surface and increase atmospheric stability, ultimately leading to a weakening of monsoon circulation25,26.

Many previous studies have predominantly approached the EASM as a holistic system when investigating the impact of aerosol-cloud-radiation interactions on the overall strength of the monsoon within the context of climate change. However, the EASM system is inherently characterized by seasonal processes27. The outbreak, advancement, and retreat of EASM contribute to distinct seasonal characteristics in precipitation within the monsoon region28,29,30,31. While existing research has indicated that the climatic effects of aerosols contribute to the weakening of the EASM and a reduction in overall summer precipitation, the specific role of aerosols in the seasonal progression of the EASM has not been adequately discerned. Some studies have suggested approximately a one-pentad delay in the onset time of the EASM over East China due to aerosol effects, yet the underlying physical mechanisms behind these observations remain insufficiently explained32,33. In this investigation, we delve into the influence of anthropogenic aerosol emissions on the seasonal progression of the EASM, and aim to uncover the underlying physical mechanisms through both qualitative and quantitative analyses.

Results

Seasonal march of EASM

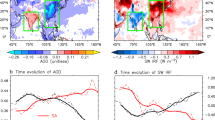

Figure 1 illustrates the spatial distribution of the onset time of the EASM based on the W_EASM index for the period from 1979 to 2014. The seasonal progression of the EASM from southwest to northeast, as depicted in the ERA5 reanalysis data (Fig. 1a), is effectively captured by the Historical experiment. In the Historical experiment (Fig. 1b), the EASM initiates its inland penetration into South China by the 25th pentad (early May). Subsequently, it steadily advances northeastward during pentads 28 to 31. By the 33rd pentad (mid-June), the EASM extends into the middle and lower Yangtze River Basin of East China, remaining stationary until pentad 35 (late June). Notably, during pentads 36-37 (late June to early July), the EASM experiences a notable northward jump, covering a considerable distance from the Yangtze River to the Huaihe River Basin. This sudden shift indicates a marked northward progression in a short time frame. By the 38th pentad, the northern edge of the EASM reaches the North China and Northeast China region, exhibiting a pronounced southwest-to-northeast pattern. From the 38th to the 42nd pentad, the EASM continues its northward trajectory in Northeast China, ultimately reaching its northernmost point at 47°N by the 42nd pentad. In Fig. 1c, the depiction of the EASM seasonal progression based on the Hist-GHG simulations reveals noteworthy differences. The Hist-GHG EASM exhibits an overall swifter advancement, covering a more northerly expanse compared to the Historical experiment. It reaches South China by the 23rd pentad and the middle and lower Yangtze River Basin by the 32nd pentad. Moreover, the EASM in the Hist-GHG simulation attains its northernmost extent of 50°N by the 41st pentad, in contrast to the 47°N reached in the Historical simulation by the 42nd pentad.

EASM onset times based on (a) ERA5 reanalysis, (b) Historical simulations and (c) Hist-GHG simulations, (d) differences in mean onset times between Historical and Hist-GHG simulations using the W_EASM index. The numbers in (a–c) represent the specific onset time. The numbers in the subgraph (d) indicate the specific lag time of the outbreak time due to aerosols.

Figure 1d displays the distribution of differences between the two simulation experiments (i.e., Fig. 1b, c), offering insights into the impact of anthropogenic aerosols on the seasonal march of EASM. The analysis reveals that anthropogenic aerosols induce a lag of about 1 to 2 pentads in the onset time over the southern portions of the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze River, North China, and Northeast China. Notably, no discernible aerosol-induced signal is observed in the onset time over the Yangtze-Huaihe River basin, where an abrupt northward jump occurs at pentads 36-37 in both Historical and Hist-GHG simulations.

To validate the outcomes derived from the W_EASM index, the H_EASM index, which incorporates zonal wind, θse, and precipitation information, is employed to assess the seasonal progression from the perspective of the northern edge of the EASM. As illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 1, negligible differences are observed in the seasonal march of the EASM between the Historical and Hist-GHG experiments during pentads 36-37. This suggests that aerosols exert minimal influence on the monsoon onset time during this specific period. However, both before and after this interval, the north edge of the EASM in the Hist-GHG simulation precedes that in the Historical runs by one pentad. Additionally, consistent with the W_EASM distribution, the Hist-GHG experiment exhibits a more northerly extension of the EASM’s northern edge. In summary, both the W_EASM and H_EASM indices display a nearly consistent pattern regarding the aerosols effect on the seasonal march of the EASM. Consequently, subsequent analyses will primarily focus on the results obtained from the W_EASM index.

Considering the impact of aerosols forcing on the EASM onset time depicted in Fig. 1d, the seasonal progression of the EASM has been segmented into three distinct phases: Pentads 25-35 (PD1), Pentads 36-37 (PD2), and Pentads 38-42 (PD3). These phases correspond to the onset time of EASM over the southern portions of the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze River (PD1), the Yangtze-Huaihe River basin (PD2), and North China and Northeast China (PD3), respectively.

Aerosols effects on the atmospheric circulation

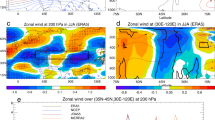

In the identified phases (PD1, PD2, and PD3), we explore the distinct aerosol-induced mechanisms influencing the seasonal progression of the EASM. Figure 2 illustrates the atmospheric circulation disparities between the Historical and Hist-GHG experiments across the lower to upper troposphere, providing insights into aerosol-induced influences on circulation.

Differences in atmospheric circulation between Historical and Hist-GHG simulations on 850 hPa (a–c), 500 hPa (d–f) and 200 hPa (g–i) for three time periods (the PD1, PD2, and PD3) are listed from left to right in each row. a–c Near-surface temperature (shading; K), mean sea level pressure (contour; hPa) and horizontal wind on 850 hPa (vectors; m·s−1). d–f Eddy geopotential height (He; shading; 10 m) and horizontal wind (vectors; m·s−1) on 500 hPa, the solid lines are contours of He = 0 m on 500 hPa from Historical (red) and Hist-GHG (blue) simulations to indicate boundaries of the West Pacific subtropical high (WPSH). g–i Zonal wind (u; shading; m·s−1) and horizontal wind (vectors; m·s-1) on 200 hPa. The dotted area indicates that the specific shading field has passed the significance test at the 95% confidence level based on a two-tailed Student’s t-test.

During the PD1 phase (Fig. 2a, d, g), a conspicuous negative surface temperature anomaly over land is observed compared to the east ocean region (Fig. 2a), resulting in a weakened northerly wind anomaly at 850 hPa over southern China. Analyzing the temperature difference time series between land and its eastern maritime region in Supplementary Fig. 2d reveals a reduction in the land-sea temperature difference primarily concentrated before the 35th pentad. In the mid-troposphere (Fig. 2d), anthropogenic aerosols lead to a reduction in the He corresponding to cyclonic anomalies in northern China at 500 hPa, bringing westerly winds to the East China region. A significant anomalous southwest wind is observed in eastern China at 200 hPa in Fig. 2g, opposing the climatological northward winds during the summer monsoon season. The southwest flow, combined with eastward winds at high latitudes, forms a closed cyclonic circulation at Shaanxi province (centered at 110°E and 35°N). Examining the distribution of vertical circulation in Supplementary Fig. 3a, the horizontal convergence at 200 hPa leads to pronounced subsidence in the mid-to-upper troposphere averaged at 25°–30°N. The downward airflow diminishes at around 850 hPa, resulting in weak northerly winds at the surface over South China. Overall, aerosols contribute to a decrease in the thermal contrast between land and sea, with anomalous northerly winds in the lower layers accompanied by anomalous southerly winds in the upper layers, contrary to the normal situation of the EASM, which leads to the weakening of the EASM and, consequently, a delay in the onset time. The results concerning the impact of aerosols on the variation of EASM intensity are presented in Supplementary Fig. 4, the influence of aerosols represented by the difference between the Historical and Hist-GHG experiments, with referring to the three monsoon intensity indices: EASM_V850, EASM_SLP, and EASM_U200. The intensity index of the EASM reveals that aerosols generally weaken the EASM across different monsoon indices.

In the context of PD2 (Fig. 2b, e, h), the reduction in the surface sea-land temperature difference is marginal, yet stronger northerly wind anomalies and southerly wind anomalies are evident at 850 hPa and 200 hPa compared to PD1. Anthropogenic aerosols induce a reinforcement of zonal westerly winds at 40°N and southwesterly winds south of 40°N. This shift from southwest winds to westerly winds results in the accumulation of air masses in the upper levels, instigating notable vertical subsidence motion at approximately 25°–30°N, as illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 3b. As these descending air currents reach the surface, they manifest as northerly winds in areas south of 30°N. The vertical circulation pattern, characterized by low-level northerly winds and upper-level southerly winds, is precisely contrary to the climatological conditions of the EASM, signifying a reduction in the summer monsoon intensity due to aerosols. At 500 hPa (Fig. 2e), aerosols lead to weak cyclonic anomalies over the northwest Pacific, indicating a weakening of the Northwest Pacific Subtropical High (WPSH). Consequently, this induces northward wind flow on the western side of the subtropical high, resulting in a reduction in the strength of the EASM. Simultaneously, aerosols cause the subtropical high to shift westward, which, according to previous research findings, can also result in the weakening of EASM34,35,36. Overall, aerosols weaken the monsoon by altering the strength and position of the subtropical high37,38. Despite aerosols causing a weakening of EASM intensity, their impact on the seasonal progression of the monsoon is not particularly pronounced in this phase. Thus, this matter warrants exploration from alternative perspectives, beyond the sole focus on monsoon intensity.

Examining the aerosols effects on surface temperature presented in Fig. 2c and Supplementary Fig. 2d, a reduction in the temperature contrast between land and ocean is evident in PD3. However, this decline is not as pronounced as observed in PD1. Concurrent with the decrease in the sea-land temperature difference, there is a noticeable emergence of northerly winds in southern China. In the analysis of the He at 500 hPa (Fig. 2f), aerosols cause the subtropical high over the western Pacific to shift eastward, which differs from previous studies on the aerosol impact on the overall position of the subtropical high throughout the summer. In this case, as the high-pressure system moves eastward, the southwest airflow around its periphery also shifts eastward, resulting in a reduced extent of southwest winds penetrating inland, thereby delaying the onset of the monsoon. The climatological ASWJ is located near 40°N at 200 hPa, with the southern and northern flanks of the ASWJ outlet region corresponding to anticyclonic divergence and cyclonic convergence, respectively. In the southern/northern parts at the corresponding positions in the lower levels, convergence/divergence motion is observed. In the upper troposphere (Fig. 2i), widespread abnormal westward winds are observed south of 40°N, indicating the southward shift of the ASWJ caused by anthropogenic aerosols. Thus, the corresponding entire-layer convergence and divergence zones have also moved southward. Firstly, the southward shift of the vertical field characterized by high-level convergence and low-level divergence on the northern flank of the jet stream axis results in abnormal subsidence movements near 40°N (Supplementary Fig. 3c), with air mass accumulation at low levels between 20° and 35°N, leads to anomalous northerly winds. Secondly, the southward migration of the low-level convergence zone on the southern flank of the jet stream axis, leads to the formation of an anomalous cyclonic center at the lower level of 850 hPa, at 20°–30°N, 130°E (as shown in Fig. 2c). Anomalous subsidence at 40°N and cyclonic anomalies at the lower levels both lead to the development of strong anomalous northerly winds in eastern China, causing a weakening of the EASM. Song et al. have noted that changes in the ASWJ align with variations in the meridional temperature gradient39. Supplementary Fig. 3c reveals an aerosol-induced cooling center in the upper troposphere, conducive to the occurrence of downward motion anomalies. Existing research has also demonstrated that the southward shift of the ASWJ contributes to the weakening of the summer monsoon18,40. The aerosol-induced abnormal northerly winds in the lower levels, southerly winds at 200 hPa, ASWJ moving south and the eastward movement of the WPSH collectively contribute to the attenuation of EASM intensity, consequently influencing its seasonal progression speed.

The comprehensive analysis indicates that the delayed seasonal advancement of EASM attributed to anthropogenic aerosols aligns with the weakened strength of the monsoon. The delayed seasonal advancement of EASM can be interpreted as a manifestation of monsoon attenuation. However, while the alteration in atmospheric circulation signals a noticeable weakening of EASM in PD2, there is almost no disparity in the onset time between Historical and Hist-GHG simulations during this period. Therefore, it can be inferred that other physical mechanisms may underlie the forward progress observed in PD2.

Physical mechanism of aerosol impact on monsoon advancement

To unravel the reason for the onset time in PD2, the dynamical and thermal factors involved in the W_EASM index are separated to discern their individual effects on the calculation of the monsoon index. Figure 3 presents the temporal distribution of EASM onset time based on the individual thresholds of θse or Vsw (W_EASM_θse or W_EASM_Vsw for short). W_EASM_θse and W_EASM_Vsw are used to indicate the effect of dynamical and thermal factors on the seasonal march of the monsoon, respectively. When the result of W_EASM_θse or W_EASM_Vsw at a specific grid point match the result of W_EASM, then the dominant factor at that point is identified as either thermal (θse) or dynamical (Vsw) factor. If the results of all three coincide, the corresponding grid point is considered to be influenced by both dynamical and thermal factors. Figure 3a, b, d, e illustrates the seasonal progression of EASM based on θse or Vsw in the Historical and Hist-GHG experiments, respectively. Among them, the magnitude of Vsw in the south of the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze River and the northern part east of 120°E meets the 2 m·s−1 criterion throughout the year, which cannot reflect the progress of EASM and is not discussed here. It reveals a larger region of W_EASM_θse (Fig. 3a, d) than W_EASM_Vsw (Fig. 3b, e), indicating that the north and west edge of the monsoon progresses mainly depend on the strength of the southwest winds.

a–c Historical simulations, (d–f) Hist-GHG simulations, (g–i) differences between Historical and Hist-GHG simulations. (a, d, g) W_EASM_θse, (b, e, h) W_EASM_Vsw, (c, f, i) Dominant factors in W_EASM index (blue, yellow, and green indicate θse, Vsw and both together play a dominant role in the monsoon onset, respectively) for Historical, Hist-GHG and differences between two simulations, respectively.

The primary factors influencing W_EASM are depicted in Fig. 3c, f. Both the Historical and Hist-GHG experiments exhibit the same pattern of dominant factors. It reveals that, in the region corresponding to the PD1 phase, the advancement of EASM aligns with the seasonal march of θse. The impact of dynamical factors can be disregarded in this phase, explaining the weak northerly wind anomaly in Fig. 2a. The EASM onset time over the region corresponding to PD3 is mainly dominated by θse, while the north edge of EASM is controlled by the farthest north position of Vsw. For the PD2 period, the onset time of EASM is dominated by the pentad when the grid Vsw reaches the threshold of 2 m·s−1. Figure 3g, h illustrates the lag time of the EASM seasonal progress due to the effect of aerosols. The entire domain consistently exhibits a lag of 1-2 pentads according to the W_EASM_θse index. In contrast, there is no apparent delay characteristic shown in the W_EASM_Vsw pattern over the Yangtze-Huaihe River basin, with one pentad delay in Shandong province and around Bohai Sea. The aerosol-induced difference in thermal conditions dominates the lag of EASM onset time in the PD1 and PD3 phases, while the dynamical factor is the main reason for the PD2 period. Therefore, the negligible effect of aerosols on the dynamical conditions in PD2 leads to the synchronous seasonal progress of EASM in the Historical and Hist-GHG experiments.

During the PD2 period, corresponding to the second northward jump of EASM, it becomes evident that the monsoon spans the entire Yangtze-Huaihe River basin in just two pentads (36-37 pentads), as illustrated in Fig. 1a–c. The occurrence of the second northward jump of EASM is intricately linked to the movement of the WPSH. Figure 4a, b showcase the position and centerline of WPSH during the 35-40 pentad period. It is observed that the meridional range of WPSH is relatively similar in the Historical and Hist-GHG experiments. However, there are differences in the zonal coverage and westward ridge point of WPSH between the two simulations, indicating that anthropogenic aerosols influence the strength and position of WPSH. Nevertheless, it is the northward movement of WPSH that impacts the seasonal progress of EASM in PD2. Various metrics measuring the ridge line and centerline of WPSH are employed to assess its movement (Fig. 4c, d). Thus, the western (110°–130°E), eastern (130°–150°E) and whole region (110°–150°E) ridge index and centerline index are calculated separately, with 130°E serving as the dividing line (Index_West, Index_East, Index). As depicted in Fig. 4c, d, both the eastern ridge and centerline indexes indicate almost synchronous northward movement of WPSH in the Historical and Hist-GHG runs. The western and whole region indexes show coordinated advancement before pentad 37, with differences emerging after this period due to variations in east-west coverage between the two experiments. After pentad 37, the indexes in Historical experiment are more southerly than the Hist-GHG experiment, resulting in less precipitation in northern China, this corresponds to the lag in monsoon onset in northern China seen in Fig. 1d. Overall, during the PD2 phase, aerosols exhibit negligible effects on the northward movement of WPSH, leading to a consistent southwest wind over the Yangtze-Huaihe River basin and, consequently, a consistent onset time of EASM between the two experiments.

a, b Coverage of the WPSH according to He (WPSH_He) and the center lines of the WPSH (WPSH_center) in pentads 25–40 (late June to mid-July). c, d Variation of the WPSH ridge index and WPSH centerline index (latitudinal position) over time (pentad). With green, blue, and black indicating the average of the two indices for the western region (110°–130°E), the eastern region (130°–150°E), and the entire region (110°–150°E), respectively. The WPSH_center is calculated as the latitude mean of the maximum value of the geopotential height at the corresponding longitude and its eight surrounding meridians in area of the WPSH. The WPSH_ridge is calculated as the latitudinal position where the zonal wind shear is greater than 0 (u = 0, ∂u ⁄ ∂y > 0) in the region of H = 5840 m. The WPSH_center/ridge_index is the average of the latitude position of the WPSH_center/ridge lines for the corresponding region.

Figure 2 qualitatively depicts the aerosol-induced attenuation of EASM, yet lacks a quantitative explanation of the delayed effect of aerosols. To address this gap and considering the distinct impacts of dynamical and thermal factors on the three periods of EASM seasonal progress, this section evaluates the time-lag relationship of various meteorological variables between the Historical and Hist-GHG experiments. The time lags, based on spatial correlations between variables in the two experiments, are summarized in Table 1, while those based on the minimum absolute errors are presented in Supplementary Table 2. The absolute errors in Supplementary Table 2 reveal an overall delay in the magnitudes of meteorological fields in the Historical runs, indicative of the weakening of EASM intensity due to aerosols.

Examining spatial correlations in Table 1, it becomes evident that most thermal factors (e.g., solar radiation, θse, temperature at 850 hPa, specific humidity at 850 hPa) exhibit a time lag of 1-2 pentads in the Historical experiment throughout the entire northward progress of EASM. Some dynamical conditions (e.g., meridional wind at 850 and 500 hPa, zonal wind at 200 hPa) experience a 1-2 pentad delay in PD1 and PD3 periods, with almost no lag in the corresponding PD2 period. Additionally, Z and He at 500 hPa over the region of WPSH show no lag in the PD2 phase, aligning with the findings from Fig. 4. At 200 hPa in the upper layer, there is a periodic lag in the zonal wind in the Historical experiment, and the lag of the ASWJ mainly occur in the middle and late stages, confirming that aerosol-induced weakening and lagging of the ASWJ primarily occurs in PD3. In summary, during the PD1 and PD3 phases, aerosols induce a 1-2 pentad delay in thermal factors, subsequently leading to a delayed onset of the monsoon. In the PD2 phase, aerosol-induced changes in the movement of the WPSH and atmospheric dynamical conditions are not significant, exerting no discernible effect on the progression of the monsoon.

Discussion

Anthropogenic aerosols induced a lag of about 1 to 2 pentads in the EASM onset time during PD1 and PD3, while their impact was notably absent in PD2. The delayed seasonal advancement of EASM in PD1 and PD3 attributed to anthropogenic aerosols aligns with the weakened strength of the monsoon. The diminished intensity of EASM in PD1 is primarily because of the reduction in the thermal contrast between land and sea surfaces and the anomaly of southerly winds in the upper atmospheric layers. Regarding PD3, the southward shift of ASWJ induces significant vertical subsidence motion, resulting in a robust northerly wind anomaly in the lower layer south of 40°N, which impedes the northward progression of the EASM system. The specific time lag of the EASM seasonal march in PD1 and PD3 is dominated by the aerosols effect on the atmospheric thermal conditions.

Although it also shows noticeable weakening of EASM in PD2, there is almost no disparity in the seasonal progress between Historical and Hist-GHG simulations during this period. Exploring the connection between PD2 and the second northward jump of the WPSH, it showcases differences arise in the intensity and position of WPSH, however, its ridge line and center line underscore the synchronous northward shift during 25–37 pentads in the two simulations. That is to say, aerosols do impact the intensity of the WPSH. However, they do not affect the timing of its two northward jumps. Therefore, the seasonal progression of the monsoon has not been affected. The seasonal movement speed of the EASM is primarily governed by dynamical factors during PD2.

Previous studies on the influence of aerosols on the summer monsoon have also highlighted how aerosols alter the land-sea thermal contrast, subtropical high intensity, and jet stream position, thus affecting the strength of monsoon. However, these studies viewed the entire summer as a unified entity, examining changes in monsoon intensity. In contrast, this study focuses on different stages of the northward progression of the EASM, investigating how aerosols affect EASM advancement at each phase. Aerosols lead to a weakening of the land-sea thermal contrast, resulting in a weakening of the monsoon intensity and a delay in its progression. This study emphasizes that this factor has a more significant impact on the monsoon in the areas south of the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze River and northeast China. The southward shift of the westerly jet stream mainly affects the monsoon in northeast China. Additionally, from the perspective of the WPSH, aerosols cause changes in the intensity of the subtropical high, leading to a weakening of the summer monsoon. However, aerosols do not affect the north-south movement speed of the WPSH, and thus do not influence the progress of EASM. These findings indicate that a weakening of monsoon intensity does not necessarily lead to a slower monsoon progression. Different dominant factors exist for each stage of monsoon progression.

Based on existing research indicating a minimal influence of natural forcings on monsoon rainfall, this paper roughly representing the climate effects of aerosols by the difference between Historical and Hist-GHG experiments. Neglecting the impact of natural forcings on monsoon systems may introduce some uncertainties into the findings of this paper. Furthermore, the climate effects of absorbing and scattering aerosols exhibit differences, which could lead to varying impacts on monsoon advancement. The current findings are based on the overall anthropogenic aerosols without distinguishing the impacts of different types of aerosols and their physical and chemical properties on monsoon progression, necessitating further research through aerosol sensitivity experiments for differentiation.

Methods

Dataset

This paper uses ECMWF Reanalysis v5 (ERA5) hourly data as a ref.41. The daily mean outputs from the Historical and Hist-GHG simulations of six global climate models in Coupled Model Intercomparison Program phase 6 (CMIP6) are used to investigate the anthropogenic aerosols effects on the seasonal march of EASM. The first ensemble member outputs in the simulations are involved. Supplementary Table 1 shows the detailed information of the six models. The variables used in this study include the precipitation (Precip), specific humidity (q), relative humidity (Rh), sea level pressure (SLP), net surface solar radiation (SSR), temperature (T), atmospheric potential pseudo-equivalent temperature at 850 hPa (θse42), wind (u, v) and geopotential height (Z) throughout the layers. Referring to the existing researches43,44, the effect of natural forcing on the EASM is insignificant relative to the anthropogenic aerosols and greenhouse gases forcing. And the sum of precipitation anomalies in Hist-aer and Hist-GHG experiments is almost identical to those in Historical experiment45. Thus, we calculate the difference between Historical and Hist-GHG experiments to estimate the role of anthropogenic aerosol-dominated forcing. The daily average meteorological fields from CMIP6 are aggregated into climatological annual cycle as a multi-model ensemble mean (MME). The pentad scale MME meteorological fields are further used to study the impact of anthropogenic aerosols on the monsoon progression. The eddy geopotential height at 500 hPa (abbreviated as He hereafter) is used in this study to measure the area of Northwest Pacific Subtropical High (WPSH)46.

EASM index measuring its seasonal march progress

The corresponding monsoon indices are calculated to study the effect of anthropogenic aerosols forcing on the seasonal march of EASM. Note that we only focus on the monsoon onset and northward migration process, without the retreat phase. This analysis mainly used the index characterizing the seasonal march of the EASM proposed by Wang et al. (W_EASM index hereafter)47, which considers the dynamical factor in combination with thermal and moisture factors. Under the premise that the southwest wind (Vsw) at 850 hPa is greater than 2 m·s−1, and at the same time, the pentad average atmospheric potential pseudo-equivalent temperature (θse) at 850 hPa is greater than 340/335 K in the region south/north of 30°N. For the specific grid, the first pentad that both the Vsw and θse meet the above criteria is defined as the onset time of EASM (i.e., the W_EASM index).

In order to ensure the accuracy of W_EASM index, another EASM index indicating the northern edge of the EASM is used48, which is defined as the H_EASM index. H_EASM index combines the information of θse, wind field and precipitation. Firstly, the pentad average horizontal wind at 850 hPa is southwesterly (i.e., u > 0 and v > 0), and then, pentad average θse at 850 hPa is not less than 335 K and the pentad-mean precipitation ≥ 4 mm·d−1. When all the above three variables meet their thresholds, it is considered that the northernmost edge of the monsoon has reached that grid point.

In terms of the intensity of EASM, three EASM index have been involved in this study, i.e., EASM_V85049, EASM_SLP50, and EASM_U20051. EASM_V850 is defined as the average of the 850 hPa meridional wind (V850) in the region of 110°–125°E, 20°–40°N. EASM_SLP is defined as the sum of values for which the difference in SLP between 110°E and 160°E, calculated at every 10 degrees of latitude within the 10°-50°N region, where the difference is less than or equal to -5. EASM_U200 is defined as the difference of 200 hPa zonal JJA wind between the regions of 110°–150°E, 40°–50°N and 110°–150°E, 25°–35°N.

Data availability

The daily meteorological variables from the six CMIP6 models can be available at https://aims2.llnl.gov/search?project=CMIP6&activeFacets=%7B%22variant_label%22%3A%22r1i1p1f1%22%2C%22frequency%22%3A%22day%22%2C%22variable_id%22%3A%5B%22hur%22%2C%22hus%22%2C%22pr%22%2C%22psl%22%2C%22rlds%22%2C%22rlus%22%2C%22rsds%22%2C%22rsus%22%2C%22ta%22%2C%22tas%22%2C%22ua%22%2C%22va%22%2C%22wap%22%2C%22zg%22%5D%2C%22experiment_id%22%3A%5B%22historical%22%2C%22hist-GHG%22%5D%2C%22source_id%22%3A%5B%22ACCESS-ESM1-5%22%2C%22CanESM5%22%2C%22FGOALS-g3%22%2C%22IPSL-CM6A-LR%22%2C%22MIROC6%22%2C%22MRI-ESM2-0%22%5D%2C%22table_id%22%3A%5B%22Eday%22%2C%22day%22%5D%7D The ERA5 hourly data from 1979 to 2014 can be downloaded at https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/cdsapp#!/dataset/reanalysis-era5-single-levels?tab=form.

References

Zhang, R. H., Sumi, A. & Kimoto, M. Impact of El Nino on the East Asian monsoon: A diagnostic study of the ‘86/87 and ‘91/92 events. J. Meteorol. Soc. Jpn. 74, 49–62 (1996).

Qi, L., He, J. H., Zhang, Z. Q. & Song, J. N. Seasonal cycle of the zonal land-sea thermal contrast and East Asian subtropical monsoon circulation. Chin. Sci. Bull. 53, 131–136 (2008).

Lei, Y. H., Hoskins, B. & Slingo, J. Exploring the Interplay between Natural Decadal Variability and Anthropogenic Climate Change in Summer Rainfall over China. Part I: Observational Evidence. J. Clim. 24, 4584–4599 (2011).

Wu, G. et al. Advances in studying interactions between aerosols and monsoon in China. Sci. China-Earth Sci. 59, 1–16 (2015).

Zhang, R. H., Min, Q. Y. & Su, J. Z. Impact of El Nino on atmospheric circulations over East Asia and rainfall in China: Role of the anomalous western North Pacific anticyclone. Sci. China-Earth Sci. 60, 1124–1132 (2017).

Yu, R. C., Wang, B. & Zhou, T. J. Tropospheric cooling and summer monsoon weakening trend over East Asia. Geophys. Res. Lett. 31, L22212 (2004).

Xu, M. et al. Steady decline of east Asian monsoon winds, 1969-2000: Evidence from direct ground measurements of wind speed. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 111, D24111 (2006).

You, Q. L. et al. Changes in daily climate extremes in China and their connection to the large scale atmospheric circulation during 1961-2003. Clim. Dyn. 36, 2399–2417 (2011).

Lei, Y. H., Hoskins, B. & Slingo, J. Natural variability of summer rainfall over China in HadCM3. Clim. Dyn. 42, 417–432 (2014).

Wang, H. J. The weakening of the Asian monsoon circulation after the end of 1970’s. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 18, 376–386 (2001).

Li, Z. Q. et al. Aerosol and monsoon climate interactions over Asia. Rev. Geophys. 54, 866–929 (2016).

Zhang, X. Y. et al. Atmospheric aerosol compositions in China: spatial/temporal variability, chemical signature, regional haze distribution and comparisons with global aerosols. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 12, 779–799 (2012).

Wang, K. & Dickinson, R. E. Contribution of solar radiation to decadal temperature variability over land. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 110, 14877–14882 (2013).

Wang, T. J. et al. The interactions between anthropogenic aerosols and the East Asian summer monsoon using RegCCMS. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 120, 5602–5621 (2015).

Wang, X. Y., Zhang, R. H. & Yu, W. The Effects of PM2.5 Concentrations and Relative Humidity on Atmospheric Visibility in Beijing. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 124, 2235–2259 (2019).

Lin, Z. X., Dong, B. W. & Wen, Z. P. The effects of anthropogenic greenhouse gases and aerosols on the inter-decadal change of the South China Sea summer monsoon in the late twentieth century. Clim. Dyn. 54, 3339–3354 (2020).

Wang, K. C., Dickinson, R. E. & Liang, S. L. Clear Sky Visibility Has Decreased over Land Globally from 1973 to 2007. Science 323, 1468–1470 (2009).

Wang, Z. L., Lin, L., Yang, M. L., Xu, Y. Y. & Li, J. N. Disentangling fast and slow responses of the East Asian summer monsoon to reflecting and absorbing aerosol forcings. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 17, 11075–11088 (2017).

Wang, X. Y. & Zhang, R. H. How Did Air Pollution Change during the COVID-19 Outbreak in China. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 101, E1645–E1652 (2020).

Ding, A. J. et al. Enhanced haze pollution by black carbon in megacities in China. Geophys. Res. Lett. 43, 2873–2879 (2016).

Wang, X. Y. & Zhang, R. H. Effects of atmospheric circulations on the interannual variation in PM2.5 concentrations over the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region in 2013-2018. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 20, 7667–7682 (2020).

Wang, K. C. & Dickinson, R. E. Global atmospheric downward longwave radiation at the surface from ground-based observations, satellite retrievals, and reanalyses. Rev. Geophys. 51, 150–185 (2013).

Wang, X. Y., Dickinson, R. E., Su, L. Y., Zhou, C. L. E. & Wang, K. C. PM2.5 Pollution in China and How It Has Been Exacerbated by Terrain and Meteorological Conditions. B. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 99, 105–120 (2018).

Ayantika, D. C. et al. Understanding the combined effects of global warming and anthropogenic aerosol forcing on the South Asian monsoon. Clim. Dyn. 56, 1643–1662 (2021).

Zhang, H. et al. Simulation of direct radiative forcing of aerosols and their effects on East Asian climate using an interactive AGCM-aerosol coupled system. Clim. Dyn. 38, 1675–1693 (2012).

Guo, L., Highwood, E. J., Shaffrey, L. C. & Turner, A. G. The effect of regional changes in anthropogenic aerosols on rainfall of the East Asian Summer Monsoon. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 13, 1521–1534 (2013).

Ha, K. J., Heo, K. Y., Lee, S. S., Yun, K. S. & Jhun, J. G. Variability in the East Asian Monsoon: a review. Meteorol. Appl. 19, 200–215 (2012).

Ding, Y. H. Seasonal march of the East-Asian summer monsoon. East Asian Monsoon 2, 3–53 (2004).

Ding, Y. H. & Chan, J. C. L. The East Asian summer monsoon: an overview. Meteor. Atmos. Phys. 89, 117–142 (2005).

Wu, Z. W., Wang, B., Li, J. P. & Jin, F. F. An empirical seasonal prediction model of the east Asian summer monsoon using ENSO and NAO. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 114, D18120 (2009).

Zhu, C., Liu, B., Zuo, Z., Yuan, N. & Liu, G. Recent Advances on Sub-seasonal Variability of East Asian Summer Monsoon. J. Appl. Meteor. Sci. (China) 30, 401–415 (2019).

Wang, D. D., Zhu, B., Jiang, Z. H., Yang, X. Q. & Zhu, T. The impact of the direct effects of sulfate and black carbon aerosols on the subseasonal march of the East Asian subtropical summer monsoon. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 121, 2610–2625 (2016).

Shen, X. Y., Huang, W. Y. & Chen, H. B. The Analysis of Mechanism of Impact of Aerosols on East Asian Summer Monsoon Index and Onset. J. Trop. Meteorol. 23, 357–367 (2017).

Zhang, Q. Y. & Tao, S. Y. The Anomalous Subtropical Anticyclone in Western Pacific and Their Association with Circulation over East Asia during Summer. Chin. J. Atmos. Sci. 27, 369–380 (2003).

Ding, Y. H. & Liu, Y. Y. A Study of the Teleconnections in the Asian-Pacific Monsoon Region. Acta Meteor. Sin. 22, 404–418 (2008).

Yan, H. M., Xiao, Z. N. & Xue, J. J. The influence of east-west displacement of Northwestern Pacific subtropical high on east-west difference of precipitation in southern China in early summer. Chin. J. Geophys-Ch. 64, 765–781 (2021).

Wang, B., Xiang, B. & Lee, J. Y. Subtropical high predictability establishes a promising way for monsoon and tropical storm predictions. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 110, 2718–2722 (2013).

Chen, G. X., Wang, W. C. & Chen, J. P. Circulation responses to regional aerosol climate forcing in summer over East Asia. Clim. Dyn. 51, 3973–3984 (2018).

Song, F. F., Zhou, T. J. & Qian, Y. Responses of East Asian summer monsoon to natural and anthropogenic forcings in the 17 latest CMIP5 models. Geophys. Res. Lett. 41, 596–603 (2014).

Mu, J. & Wang, Z. Responses of the East Asian summer monsoon to aerosol forcing in CMIP5 models: The role of upper‐tropospheric temperature change. Int. J. Climatol. 41, 1555–1570 (2020).

Hersbach, H. et al. ERA5 hourly data on pressure levels from 1940 to present. Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) Climate Data Store (CDS). https://doi.org/10.24381/cds.bd0915c6 (Accessed on 20-06-2024) (2023).

Bolton, D. The Computation of Equivalent Potential Temperature. Mon. Weather Rev. 108, 1046–1053 (1980).

Zhou, T. J., Ren, L. W. & Zhang, W. X. Anthropogenic influence on extreme Meiyu rainfall in 2020 and its future risk. Sci. China-Earth Sci. 64, 1633–1644 (2021).

Dong, T. Y., Zhu, X., Deng, R., Ma, Y. L. & Dong, W. J. Detection and attribution of extreme precipitation events over the Asian monsoon region. Weather Clim. Extrem. 38, 100497 (2022).

Cao, J. et al. Higher Sensitivity of Northern Hemisphere Monsoon to Anthropogenic Aerosol Than Greenhouse Gases. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2022GL100270 (2022).

He, C. et al. Using eddy geopotential height to measure the western North Pacific subtropical high in a warming climate. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 131, 681–691 (2018).

Wang, A. Y. et al. The definition of the advance and retreat of the summer monsoon in China (in Chinese). Plateau Meteor 18, 400–408 (1999).

Hu, H. R. & Qian, W. H. Identifying the northernmost summer monsoon location in East Asia. Prog. Nat. Sci. 17, 812–820 (2007).

Wang, H. J. The instability of the East Asian summer monsoon - ENSO relations. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 19, 1–11 (2002).

Guo, Q. Y. The summer monsoon intensity index in East Asia and its variation (China). Acta Geogr. Sin. (Chin.) 38, 207–217 (1983).

Lau, K. M., Kim, K. M. & Yang, S. Dynamical and boundary forcing characteristics of regional components of the Asian summer monsoon. J. Clim. 13, 2461–2482 (2000).

Acknowledgements

We thank the support of MAP-AQ Asian Office, and FDU-IRDR-ICoE-RIG-WECEIPHE. This research has been funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 42075058, 42288101, and 42375183).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.G. and X.W. designed research. S.G., X.G., and Y.T. performed the analyses and wrote the paper. All authors contributed to the final version of the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Guo, S., Wang, X., Gui, X. et al. Influence of aerosol forcing on the seasonal march of East Asia summer monsoon. npj Clim Atmos Sci 7, 143 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-024-00699-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-024-00699-x