Abstract

The heat storage capacity of Southern Ocean (SO) buffers future atmospheric warming but differs vastly across climate models. Reducing its projection uncertainty is vital for understanding and evaluating future global sustainability. Using Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6, we show that the present-day SO high-latitude easterly wind anomalies induced by El Niño is an effective constraint for the projected increase in SO heat content. Models simulating weaker El Niño-induced easterlies generate more equatorward atmospheric teleconnection in the present day. Under global warming, these models have greater capacity in the poleward shift of atmospheric circulation, thus generate stronger future increase in El Niño-induced high-latitude easterlies, slowing the SO heat storage by weakening the northward Ekman transport that underpins the dynamical process for SO heat storage. However, most models overestimate the present-day El Niño-induced easterlies, implying that alleviating this bias would reduce future SO heat storage, thus exacerbating atmospheric warming.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Southern Ocean (SO) is an important part of the global ocean conveyor belt linking major water masses with different temperature, salinity, and density across the Atlantic, Indian, and Pacific Oceans1. It is also a complex system with many unique features, e.g., the Antarctic Circumpolar Current, the supergyre circulation, and the prevailing westerly winds which induce strong circumpolar upwelling and equatorward Ekman transport north of the Antarctica2,3. The high-latitude upwelled water uptakes heat through air-sea heat flux while being advected northward via Ekman transport. It then subducts along isopycnals to the deep ocean centered around 45°S4,5,6,7,8. This physical process underpins the observed SO warming which accounts for 60%–90% of global ocean heat content change since 20063,9. The heat stored by the SO does not only directly impact global sea level and marine ecosystems10,11, but also significantly modulates global surface warming12. The projected increase in SO heat content or heat storage (SOHS) is large with a strong inter-model spread13, impeding ongoing effort in estimating Earth’s energy imbalance and posing a challenge to frame reliable climate adaptation plans.

One way to reduce projection uncertainties is through the framework of emergent constraints, which has often been used to examine the impact of an observable present-day simulation on a projected change of interest through an inter-model relationship that can be dynamically explained14,15. The present-day SO stratification is found to be a possible constraint to the future heat uptake as represented using air-sea heat flux over 30°S–55°S16. As it does not reflect the net heat content change associated with heat subduction processes induced by the high-latitude northward Ekman transports4,5,6,7,8, processes that dynamically constrain future SOHS remain a major roadblock for faithful projection in global surface warming.

A two-way interaction between SO warming and tropical Pacific climate has been previously suggested13,17,18,19,20,21. Utilizing coupled climate models, future Antarctic sea-ice loss corresponding with SO warming can induce an El Niño-like warming pattern over the tropical Pacific Ocean which is conducive to enhance El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) variability19. On the other hand, models with a stronger increase in ENSO variability under global warming project a slower SO warming by forcing stronger cumulative easterly wind anomalies over Southern Hemisphere high latitudes through ENSO teleconnection13. Such tropical-extratropical interaction may shed light on the ongoing efforts to address the large uncertainty in future projection of SOHS. Below we show that the inter-model variations in increased SOHS under different emission scenarios are affected by the simulated present-day ENSO teleconnection.

Results

Observed response to ENSO rectification

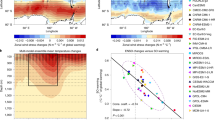

ENSO is the Earth’s strongest interannual climate variability exerting consequential influences worldwide through its teleconnection22,23. Compared to its interannual variation, ENSO nonlinear rectification due to El Niño and La Niña asymmetry13,24,25,26,27,28 could modulate long-term climate over decadal to interdecadal timescales, providing a pathway for interannual ENSO SST variability to constrain future SOHS. In particular, the tendency for El Niño to be larger in amplitude than La Niña, contributed by a nonlinear wind response to further warming after convection establishment during El Niño events27,28,29, manifests as positive skewness in sea surface temperature (SST) anomalies over central-to-eastern equatorial Pacific Ocean27,28,29. By adding El Niño and La Niña SST composites, the residual can represent ENSO’s rectification onto the mean state30,31,32,33; e.g., cumulating SST anomalies over all ENSO years since 1948 leads to an El Niño-like residual SST pattern (Fig. 1a). To investigate the impacts from the time-varying ENSO residuals, we first calculate the cumulative ENSO index as the summation of Niño3.4 over past ENSO years up to and including each increment year30,31,32,33. Cumulating Niño3.4 index of ENSO years based on different ENSO thresholds produce similar results to the index cumulated using all years (curves in Fig. 1b), emphasizing the effect of ENSO nonlinear rectification onto the mean state. Compared to the Niño3.4 index, there is distinct decadal to interdecadal variability in the cumulative Niño3.4 index (bars vs curves in Fig. 1b) which is an important source of tropical Pacific decadal variability24,34.

a The difference in SST anomalies between El Niño and La Niña since 1948. The El Niño and La Niña events are defined using the Niño3.4 index (5˚S-5˚N, 170˚W-120˚W) averaged over the ENSO peak season (December, January, February, DJF) when it is greater than 0.75 standard deviation (s.d.). b A comparison between Niño3.4 index and its cumulative index as indicated by bars and curves, respectively. The cumulative Niño3.4 index is calculated only using ENSO events defined as when magnitude of Niño3.4 is greater than 0.75 s.d. (purple), 0.5 s.d. (red), and using all events (blue). c Regression pattern (in units of N m−2 s.d.−1) of zonal averaged zonal wind anomalies onto Niño3.4 index as interannual teleconnection (black line), and regression pattern (in units of N m−2 s.d.−1) of cumulative zonal wind anomalies onto cumulative Niño3.4 index (dashed lines) when Niño3.4 magnitude is greater than 0.75 s.d. (purple), 0.5 s.d. (red), and using all events (blue). d The climatological zonal averaged zonal wind (N m−2). The orange shade indicates the region of climatological westerly wind belt. The SST and zonal wind anomalies are both quadratically detrended before analysis. The ENSO residual induced teleconnection which could rectify on the decadal-to-interdecadal long-term mean climate is similar to interannual ENSO teleconnection pattern in observation.

ENSO influences global climate via its atmospheric teleconnection22, including a meridional shift in the Southern Hemisphere atmospheric circulation as a result of ENSO-induced convective heating over the equatorial Pacific Ocean35,36. During El Niño events, the Hadley cell, that is, the low latitude segment of the Earth’s large-scale meridional wind circulation, strengthens and contracts towards the equator. In association, the Ferrel cell and Polar cell, which are the mid- and high-latitude segments respectively, also shift equatorward. This induces easterly wind anomalies over the climatological westerly wind belt through Coriolis effect (black curve in Fig. 1c vs. Fig. 1d) (refs. 13,35,36).

Cumulating zonal wind anomalies and calculating its response to cumulative Niño3.4 index (dashed curves in Fig. 1c), shows mid-latitude easterlies within the climatological westerly belt, analogous to that of the interannual ENSO teleconnection (dashed curves vs black in Fig. 1c). This indicates that the ENSO nonlinearity induced rectification over the tropical Pacific Ocean could force a teleconnection pattern over decadal to interdecadal timescales similar as the interannual ENSO teleconnection. Below we show that such ENSO rectification-related teleconnection is proportional to ENSO interannual teleconnection based on an inter-model relationship.

Simulated response to ENSO rectification

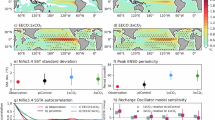

The first available realization for 26 models participating in the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6) (ref. 37) are utilized (see model selection criteria in Methods and Supplementary Table 1). As ENSO SST skewness is an important metric to evaluate ENSO nonlinearity, we first compare Niño3.4 SST skewness between observations and models over the same period (1948–2020). More than half of the models simulate positive skewness over central-to-eastern equatorial Pacific Ocean, but most models underestimate it (Fig. 2a). Such underestimation influences ENSO rectification-related teleconnection, which will be discussed below.

a Skewness of the Niño3.4 index simulated by CMIP6 models during 1948–2020. The horizontal black line indicates the observed Niño3.4 skewness index. b The multi-model ensemble mean of regression pattern (in units of N m−2 s.d.−1) of zonal averaged zonal wind anomalies onto Niño3.4 index as interannual teleconnection (black line). The range associated with one standard deviation is indicated by the grey shades. The multi-model ensemble mean of regression pattern (in units of N m−2 s.d.−1) of cumulative zonal wind anomalies onto the cumulative Niño3.4 index when Niño3.4 index is greater than 0.75 s.d. (purple), 0.5 s.d. (red), and using all events (blue) are also shown. c The regression pattern of cumulative zonal wind anomalies onto the cumulative Niño3.4 index averaged over the top-5 models with largest ENSO skewness (red curve) and the bottom-5 models with smallest ENSO skewness (blue curve). The inter-model ranges associated with one standard deviation for the top-5 and bottom-5 models are also indicated by orange and light blue shades, respectively. The difference between the two groups is indicated by the black curve. Models can simulate ENSO residual induced teleconnection similar as observed but influenced by simulated ENSO skewness.

Similar to analysis applied to observation, we calculated the response of zonal wind anomalies to Niño3.4 index. Most models simulate easterly wind anomalies over southern mid-to-high latitudes during El Niño events (black line with shade in Fig. 2b). We also calculated the cumulative zonal wind anomalies associated with the time-varying ENSO residuals for each model based on the different ENSO thresholds. Similar to the observed (Fig. 1c), the ensemble mean of residual ENSO-teleconnection pattern resembles the ensemble mean interannual ENSO teleconnection (dashed curves vs black in Fig. 2b). An inter-model relationship shows that models with greater easterly anomalies in response to El Niño interannually simulate greater cumulative easterly anomalies in response to ENSO rectification (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Unlike the El Niño interannual-teleconnection pattern which features easterly wind anomalies for all models (x-axis in Supplementary Fig. 1), the spread in cumulative wind response is much larger (y-axis in Supplementary Fig. 1). This large spread in cumulative wind response is in part linked to the bias in the simulation of Niño3.4 skewness. A comparison in the cumulative ENSO impact between a group of five models that simulate the weakest Niño3.4 skewness (bottom-5) and another group of five models with the strongest Niño3.4 skewness (top-5) shows that the cumulative easterly anomalies over the southern high latitudes are substantially greater in the top-5, compared to the bottom-5 which simulates cumulative westerly anomalies (Fig. 2c). The purpose of this grouping is to highlight the associated effect of ENSO rectification, rather than evaluating ENSO performance in models, as ENSO skewness can vary substantially across ensemble members of a single model38. Given that the response of cumulative zonal wind anomalies to cumulative ENSO is proportional to ENSO interannual teleconnection (Supplementary Fig. 1), hereafter we simply use interannual ENSO teleconnection to represent the ENSO residual-related teleconnection.

Present-day ENSO teleconnection as a constraint

The SO has been observed to feature a strong warming trend centered around 45°S that extends to over 1000 m depth below the surface13,39. The warming pattern is captured by climate models and is projected to intensify under global warming (Supplementary Fig. 2a). Given its immediate impacts on global sea level rise and marine ecosystems10,11, the extent to which the SO may warm further has been a subject of intense research. The projected changes in SO heat content are highly uncertain with a strong inter-model spread ranging from 53 to 104 ZJ per degree C of global warming (zetta Joules which is equal to 1021 Joules) (Supplementary Fig. 2b, c). Here the projected SOHS change is defined as the difference in the heat content mean state between the present-day climate (1948–2020) and the equivalent time length of the future climate (2027–2099) over the domain of (0°–360°E, 40°S–60°S, upper 1000 m) where the projected SO warming is most prominent13,40,41,42,43, and then scaled by the respectively global mean temperature change to remove the influences from model sensitivity (see Methods). We use 1948–2020 to represent the present-day climate as to include long enough observations which is further explained in the Discussion. As the model drift on the deep ocean heat storage is large (Supplementary Fig. 3), its influence on the projected changes in SOHS has also been removed (see Methods).

We found that the simulated present-day El Niño teleconnection provides a dynamical constraint for the projected SOHS change. The inter-model regression pattern of SOHS changes onto the present-day El Niño teleconnection (Fig. 3a) indicates that models simulating weaker El Niño-induced easterly wind anomalies (stronger westerly) over southern high latitudes tend to project smaller SOHS increase. The projected increase in SOHS is dominated by two processes44, one is by passive advection of the anomalous warming by the climatological ocean flows6,7,42,45 and the other by changes in ocean circulation45. The passive advection of warming by the mean flows is proportional to the increase in atmosphere heating, which increases with climate sensitivity (Supplementary Fig. 4a). As climate sensitivity is strongly correlated with the projected changes in global mean temperature13, we used global mean surface temperature change as a surrogate for climate sensitivity. The increase in SOHS through the passive advection by the mean flows is via the increase in net air-sea heat flux, which increases with climate sensitivity as expected13. As such, inter-model differences in SOHS increase due to this process are by and large removed in our scaling by global mean temperature change, and no longer related to inter-model differences in climate sensitivity (Supplementary Fig. 4b, c) or in climatological winds which represent the mean circulation (Supplementary Fig. 4d). The remaining inter-model differences are therefore dominated by the component driven by the changed circulation, which includes the modulation by ENSO-induced zonal wind anomalies. The inter-model differences in the regional average of present-day zonal wind anomalies over 55°S–65°S induced by El Niño teleconnection (black box in Fig. 3a) explains around 50% (square of the correlation coefficient in Fig. 3b) of the inter-model spread in the projected SOHS changes, implying a potential emergent constraint for the SOHS projection.

a An inter-model regression pattern of projected changes in SOHS onto present-day El Niño teleconnection pattern (ZJ per degree C of global warming per (N m−2 s.d.−1)). The dotted area indicates where the correlation coefficient is significant above the 95% confidence level based on a Student’s t-test. The black box indicates the region where we calculated the regional average of present-day El Niño induced easterlies to constrain the SO heat content changes. b An inter-model relationship between present-day El Niño teleconnection averaged over 0°–360°E, 55°S–65°S and projected SOHS changes. The vertical red line indicates the observed El Niño teleconnection from 1948 to 2020 with dotted lines indicating one standard deviation range (see Methods). The solid black line shows the linear regression across the CMIP6 ensemble, and the dashed black lines show the prediction errors for the linear fit (one standard deviation range). The correlation coefficient, slope and p-value are all indicated. The projected SOHS could be constrained by the present-day ENSO teleconnection.

The mechanism involves projected changes in El Niño-induced high latitude wind anomalies (Fig. 4a). A greater projected increase in El Niño induced high-latitude easterly anomalies corresponds to slower SO warming by weakening the westerly poleward intensification and the associated equatorward Ekman transports13. The projected changes in El Niño-induced high-latitude wind anomalies are not only associated with projected changes in ENSO amplitude13, but also influenced by properties of the present-day ENSO teleconnection, such as the present-day latitudinal location of El Niño-induced easterlies, which is calculated as the latitude of the poleward boundary of the easterly wind anomalies. For example, in models in which the present-day teleconnection is located further equatorward, the projected increase in El Niño-induced high-latitude easterlies is systematically greater (Fig. 4b).

a An inter-model regression pattern of projected SOHS changes onto projected changes in ENSO teleconnection pattern (ZJ per (N m−2 s.d.−1)). The black box indicates the region where we calculated the regional average of present-day El Niño induced easterlies to constrain the SO heat content changes. b An inter-model regression pattern of projected changes in ENSO teleconnection pattern onto present-day latitudinal location of El Niño-induced easterlies (N m−2 s.d.−1 per degree C of global warming per degree of latitude). c An inter-model relationship between present-day El Niño teleconnection averaged over 0°–360°E, 55°S–65°S and its latitudinal location. The correlation coefficient, slope and p value are all indicated. d The same as c, but for projected changes. Such constraint is through El Niño-induced zonal wind anomalies over the SO which modulates Ekman transport for SO heat subduction.

In the present-day, the magnitude of El Niño-induced high-latitude easterlies is related to the latitudinal location of ENSO teleconnection (Fig. 4c). In models that simulate ENSO-induced easterlies further equatorward, a greater poleward shift in ENSO teleconnection, as part of the global warming-induced change in the Southern Hemisphere atmospheric circulations46,47,48, leads to a greater increase in El Niño-induced high-latitude easterlies (Fig. 4d), because there is more capacity for a greater poleward shift39,49,50.

For example, MIROC6, in which the simulated present-day ENSO teleconnection is located further north than other models, projects a greater increase in high-latitude easterly anomalies (Fig. 4b), slowing the projected SO warming by weakening the mean westerly poleward intensification and the associated equatorward Ekman transports (Fig. 4a). In this way, the present-day ENSO teleconnections over Southern Hemisphere high latitudes influence the projected SO warming (Fig. 3).

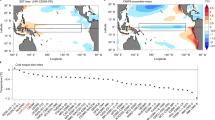

To examine the robustness of this emergent constraint relationship (see Robustness section in Methods), we used outputs from the same CMIP6 models but forced under abrupt quadrupling of atmospheric CO2 (abrupt-4xCO2)37. The projected SOHS changes are calculated as the difference between the abrupt-4xCO2 experiment and the corresponding time periods in preindustrial control simulation (see Supplementary Table 2). The ENSO teleconnections in free-running preindustrial simulations constrain the projected SOHS under the abrupt-4xCO2 scenario (Supplementary Fig. 5). In addition, evaluating the projected SOHS changes forced under the CMIP6 SSP3–7.0, SSP2–4.5, and SSP1–2.6 lower emission scenarios suggests that the present-day El Niño-induced high-latitude easterlies are also an efficient emergent constraint for future SO warming under various emission scenarios (Fig. 5a–c).

a–c The same as Fig. 3b but the projected change in SO heat content is calculated using data forced under SSP3–7.0, SSP2–4.5, and SSP1–2.6, respectively. The vertical red line indicates the observed El Niño teleconnection from 1948 to 2020 with dotted red lines indicating one standard deviation range (see Methods). d Boxplots corresponding to the range in the original projected SOHS changes (ZJ per degree C of global warming) for all the four emission scenarios. Red line indicates median value; the bottom and top edges of the box indicating the 25th and 75th percentiles, respectively; the lines that extend below and above the box indicate the minimum and maximum values; the “plus” indicates outliers. Black dots are constrained future SOHS changes (ZJ per degree C of global warming) by observed El Niño teleconnection. The error bars are based on both the uncertainty in the emergent relationship and the uncertainty in observed teleconnection induced uncertainty in SOHS (see Methods). The constraint which is also valid under other emission scenarios leads to reduction of SOHS projection uncertainty.

Discussion

Our finding that uncertainty in projected future SOHS change can be constrained by present-day ENSO teleconnection properties, suggests that uncertainty in projected SOHS change is linked to realism of simulated present-day ENSO teleconnections. Comparing the multi-model ensemble mean with the observed easterly wind anomalies (star vs red vertical line in Fig. 3b), most models overestimate the El Niño-induced high-latitude easterlies in the present-day climate. Using different observations produces similar results (Supplementary Fig. 6). Thus, the inter-model relationship (Fig. 3b) suggests that should models simulate the observed ENSO teleconnection, the projected Southern Ocean warming in the multi-model ensemble mean would be smaller. The slower SOHS would lead to more heat retained in the atmosphere, which would in turn exacerbate the projected atmospheric warming and its associated impacts. This has an important implication for sustainability of our planet in a warmer future.

Using the associated sensitivity in Fig. 3b, we estimate the potential implications based on the observed ENSO teleconnection. Note that the observed sensitivity value may vary with new observations and an increase in data length and quality. Reducing this uncertainty requires long sustained observation into the future. The emergent relationship between simulated ENSO teleconnection and projected changes in SO heat content leads to an increase of 72.0 ± 10.6 ZJ per degree C of global warming over the next 70 years in future SOHS (see Methods for significance test), instead of 78.4 ± 25.5 ZJ per degree C of global warming (Fig. 5d). This 10% reduction in the constrained SOHS may translate to a substantial increase in global atmospheric warming. The constrained SOHS is similar across different emission scenarios (Fig. 5d), suggesting a consistent mechanism governing the projected SOHS uncertainty in response to different levels of greenhouse gas emissions. This is derived through a systematic inter-model relationship, in which the spread is dominated by differences in model structures rather than internal variability. The impact of internal variability is also expected to be relatively minor, given the projected change is based on an average over a long period which tends to obscure internal variability. This present study focuses on the large inter-model spread in the future SOHS changes based on the framework of emergent constraint in which ENSO teleconnection rectifying to the mean state systematically modulates the projected changes in SO heat content.

The associated uncertainty in the constrained relationship is determined by the strength of the link between the present-day simulations and projections, which strengthens with longer time window as influence from internal variability weakens (Supplementary Fig. 7). It also depends on the reliability of the observational records. The quality of observations has improved only after 1979 when satellite instruments were deployed, thus calling for sustained reliable records from global observing systems to reduce the projection error in the emergent constraint relationship associated with observational uncertainty.

Methods

CMIP6 data and processing

To calculate Southern Ocean heat content and associated influences from ENSO teleconnections in the Southern Hemisphere, we use outputs from 26 CMIP6 models (Supplementary Table 1) (ref. 37). The selection of 26 models depends on the availability of ocean temperature, sea surface temperature, surface temperature, and surface zonal wind stress for historical forcing (1850–2014), the Shared Socioeconomic Pathway (SSP) 5–8.5 (2015–2100) emission scenario, and pre-industrial control simulations (to remove model drift in Southern Ocean heat content). Before data analysis, the horizontal grids of each model are regridded to 1°x1°; the vertical levels in ocean temperature are interpolated to follow [10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 110 120 130 140 150 160 170 180 190 200 210 220 250 280 300 340 400 500 600 700 800 900 1000 1300 1500 1800 2000 2300 2500 2800 3000 3300 3500 3800 4000 4300 4500 4800 5000] in unit of m. To include all the possible lead-lag influences from ENSO, ENSO impacts are calculated by regressing annual averaged zonal wind anomalies from June (0) to May (1) onto December (0)-January (1)-February (1) averaged Niño3.4 index, with ‘(1)’ indicating the year that follows the previous year ‘(0)’. The monthly anomalies are calculated with reference to the monthly climatology over the 20th century and then quadratically detrended.

Observations

We used the observed monthly SSTs from Hadley Centre Sea Ice and Sea Surface Temperature dataset (HadISST) (ref. 51) and surface zonal wind stress from the National Centre for Environmental Prediction (NCEP)/National Centre for Atmospheric Research (NCAR) reanalysis 1 (ref. 52) to assess the observed ENSO teleconnection focusing on 1948–2020. To test the sensitivity of our main result shown in Fig. 3b to different datasets, we also used zonal wind stress from Twentieth Century Reanalysis Version 2 (20CRv2) (ref. 53) (Supplementary Fig. 6). The monthly anomalies are quadratically detrended.

Projected changes in Southern Ocean heat content

Before calculating the projected changes, we first estimated the model drift induced trend in pre-industrial control simulations by fitting a quadratic polynomial to the full time series of the SO heat content for each model, and then subtract a parallel trend evaluated in the piControl from the SO heat content timeseries (1850–2099) forced under historical and SSP emission scenarios54. The starting year of the parallel piControl run used to begin the historical simulation is listed in Supplementary Table 1. The projected changes in SO heat content, i.e., the projected SOHS changes, are measured by the difference between averages over future climate (2027–2099) and the present-day climate (1948–2020). It is then scaled by the corresponding increase in global mean surface temperature between the two time periods, i.e., changes per degree C of global warming. This is to unify the sensitivity of projected changes to global warming among CMIP6 models13. Removing model drift or not does not influence the inter-model relationship as shown in Fig. 3.

Robustness of the emergent constraint

To test the significance and robustness of the emergent constraint relationship (Fig. 3), the emergent constraint should be confirmed in different model sets55. As such, we also used data forced under other CMIP6 emission scenarios (Supplementary Table 1) including the SSP3–7.0, SSP2–4.5, and SSP1–2.6 which show consistent results (Fig. 5).

Similar results apply to analysis using data from CMIP6 abrupt-4xCO2 experiment (Supplementary Fig. 5). For abrupt-4xCO2, the projected SOHS are calculated as the difference in the SO heat content between the first 75 years in the abrupt-4xCO2 experiment and the corresponding time periods in preindustrial control simulation (see corresponding time periods shown in Supplementary Table 2). 4 out of the 26 CMIP6 models are not used as either the information of corresponding time periods from piControl is missing or data are not available in one of the related fields. The ENSO teleconnections in the free-running preindustrial simulation can constrain the projected SOHS under the abrupt-4xCO2 scenario, indicating that different initial conditions associated with different initial ENSO teleconnection can influence the projected changes in SO heat content under the instantaneous quadrupling of atmospheric CO2 concentration scenario.

Significance test and uncertainty

The slope shown in the emergent constraint is calculated based on a least square fit and its prediction interval is based on one standard deviation range. A student’s t-test is applied to assess the statistical significance of correlations between two variables. The σ used in error bars in Fig. 5d has considered both the uncertainty in the emergent relationship (σ1 = 9.30, the least square regression uncertainty) and the uncertainty in observed teleconnection induced uncertainty in SOHS (σ2 = 5.12, the least square regression uncertainty), following σ = \(\surd ({\sigma 1}^{2}+{\sigma 2}^{2})\) (ref. 54).

Data availability

Data related to this paper can be download from the following: HadISST from https://www.metoffice.gov.uk/hadobs/hadisst/data/download.html; NCEP/NCAR Reanalysis 1 from https://psl.noaa.gov/data/gridded/data.ncep.reanalysis.html; 20CRv2 from https://psl.noaa.gov/data/gridded/data.20thC_ReanV2.html. CMIP6 from https://pcmdi.llnl.gov/CMIP6/

Code availability

All codes for the analysis are available upon request to the corresponding author in this paper.

References

Broeker, W. S. The great ocean conveyor. Oceanography 4, 79–89 (1991).

Cai, W. et al. Southern Ocean warming and its climatic impacts. Sci. Bull. 68, 946–960 (2023).

Sallée, J.-B. Southern Ocean warming. Oceanography 31, 52–62 (2018).

Fyfe, J., Saenko, O., Zickfeld, K., Eby, M. & Weaver, A. The Role of Poleward-Intensifying Winds on Southern Ocean Warming. J. Clim. 20, 5391–5400 (2007).

Exarchou, E., Kuhlbrodt, T., Gregory, J. & Smith, R. Ocean Heat Uptake Processes: A Model Intercomparison. J. Clim. 28, 887–908 (2014).

Armour, K. C., Marshall, J., Scott, J. R., Donohoe, A. & Newsom, E. R. Southern Ocean warming delayed by circumpolar upwelling and equatorward transport. Nat. Geosci. 9, 549–554 (2016).

Morrison, A., Griffies, S., Winton, M., Anderson, W. & Sarmiento, J. Mechanisms of Southern Ocean Heat Uptake and Transport in a Global Eddying Climate Model. J. Clim. 29, 2059–2075 (2016).

Swart, N. C., Gille, S. T., Fyfe, J. C. & Gillett, N. P. Recent Southern Ocean warming and freshening driven by greenhouse gas emissions and ozone depletion. Nat. Geosci. 11, 836–841 (2018).

Durack, P. J., Gleckler, P. J., Landerer, F. W. & Taylor, K. E. Quantifying underestimates of long-term upper-ocean warming. Nat. Clim. Chang. 4, 999–1005 (2014).

Church, J. A. et al. In Understanding Sea Level Rise and Variability, eds Church, J. A. et al. Blackwell 143–176 (2010).

Cavanagh, R. D. et al. Future Risk for Southern Ocean Ecosystem Services Under Climate Change. Front. Mar. Sci. 7, 615214 (2021).

Liu, W., Xie, S.-P. & Lu, J. Tracking ocean heat uptake during the surface warming hiatus. Nat. Commun. 7, 10926 (2016).

Wang, G. et al. Future Southern Ocean warming linked to projected ENSO variability. Nat. Clim. Chang. 12, 649–654 (2022).

Allen, M. R. & Ingram, W. J. Constraints on future changes in climate and the hydrologic cycle. Nature 419, 228–232 (2002).

Wang, G., Cai, W. & Santoso, A. Simulated thermocline tilt over the tropical Indian Ocean and its influence on future sea surface temperature variability. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48, e2020GL091902 (2021).

Bourgeois, T. et al. Stratification constrains future heat and carbon uptake in the Southern Ocean between 30°S and 55°S. Nat. Commun. 13, 340 (2022).

Frierson, D. et al. Contribution of ocean overturning circulation to tropical rainfall peak in the Northern Hemisphere. Nat. Geosci. 6, 940–944 (2013).

Hwang, Y.-T., Xie, S.-P., Deser, C. & Kang, S. M. Connecting tropical climate change with Southern Ocean heat uptake. Geophys. Res. Lett. 44, 9449–9457 (2017).

England, M. R. et al. Tropical climate responses to projected Arctic and Antarctic sea-ice loss. Nat. Geosci. 13, 275–281 (2020).

Kang, S. M. et al. Walker Circulation response to extratropical radiative forcing. Sci. Adv. 6, eabd3021 (2020).

Liu, F. et al. The Role of Ocean Dynamics in the Cross-equatorial Energy Transport under a Thermal Forcing in the Southern Ocean. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 38, 1737–1749 (2021).

Yeh, S.-W. et al. ENSO atmospheric teleconnections and their response to greenhouse gas forcing. Rev. Geophys. 56, 185–206 (2018).

Cai, W. et al. Changing El Niño-Southern Oscillation in a warming climate. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2, 628–644 (2021).

Kim, G.-I. & Kug, J.-S. Tropical Pacific Decadal Variability Induced by Nonlinear Rectification of El Niño-Southern Oscillation. J. Clim. 33, 7289–7302 (2020).

Power, S. et al. Decadal climate variability in the tropical Pacific: Characteristics, causes, predictability, and prospects. Science 374, eaay9165 (2021).

Kang, I.-S. & Kug, J.-S. El Niño and La Niña sea surface temperature anomalies: Asymmetry characteristics associated with their wind stress anomalies. J. Geophys. Res. 107, 4372 (2002).

Dommenget, D., Bayr, T. & Frauen, C. Analysis of the non-linearity in the pattern and time evolution of El Niño southern oscillation. Clim. Dyn. 40, 2825–2847 (2013).

Takahashi, K. & Dewitte, B. Strong and moderate nonlinear El Niño regimes. Clim. Dyn. 46, 1627–1645 (2016).

Cai, W. et al. Increased variability of eastern Pacific El Niño under greenhouse warming. Nature 564, 201–206 (2018).

Rodgers, K. B., Friederichs, P. & Latif, M. Tropical Pacific Decadal Variability and Its Relation to Decadal Modulations of ENSO. J. Clim. 17, 3761–3774 (2004).

Choi, J., An, S.-I., Dewitte, B. & Hsieh, W. W. Interactive Feedback between the Tropical Pacific Decadal Oscillation and ENSO in a Coupled General Circulation Model. J. Clim. 22, 6597–6611 (2009).

Sun, D.-Z., Zhang, T., Sun, Y. & Yu, Y. Rectification of El Niño-Southern Oscillation into Climate Anomalies of Decadal and Longer Time Scales: Results from Forced Ocean GCM Experiments. J. Clim. 27, 2545–2561 (2014).

Ham, Y.-G. A reduction in the asymmetry of ENSO amplitude due to global warming: The role of atmospheric feedback. Geophys. Res. Lett. 44, 8576–8584 (2017).

Choi, J., An, S.-I., Yeh, S.-W. & Yu, J.-Y. ENSO-like and ENSO-induced tropical Pacific decadal variability in CGCMs. J. Clim. 26, 1485–1501 (2013).

L’Heureux, M. & Thompson, D. Observed Relationships between the El Niño Southern Oscillation and the Extratropical Zonal-Mean Circulation. J. Clim. 19, 276–287 (2006).

Lu, J., Chen, G. & Frierson, D. Response of the Zonal Mean Atmospheric Circulation to El Niño versus Global Warming. J. Clim. 21, 5835–5851 (2008).

Eyring, V. et al. Overview of the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6) experimental design and organization. Geosci. Model Dev. 9, 1937–1958 (2016).

Lee, J. et al. Robust Evaluation of ENSO in Climate Models: How Many Ensemble Members Are Needed? Geophys. Res. Lett. 48, e2021GL095041 (2021).

Lyu, K., Zhang, X., Church, J. A. & Wu, Q. Processes Responsible for the Southern Hemisphere Ocean Heat Uptake and Redistribution under Anthropogenic Warming. J. Clim. 33, 3787–3807 (2020).

Lyu, K. et al. Roles of Surface Forcing in the Southern Ocean Temperature and Salinity Changes under Increasing CO2: Perspectives from Model Perturbation Experiments and a Theoretical Framework. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 53, 19–36 (2023).

Gille, S. Decadal-Scale Temperature Trends in the Southern Hemisphere Ocean. J. Clim. 21, 4749–4765 (2008).

Cai, W., Cowan, T., Godfrey, S. & Wijffels, S. Simulations of Processes Associated with the Fast Warming Rate of the Southern Midlatitude Ocean. J. Clim. 23, 197–206 (2010).

Roemmich, D. et al. Unabated planetary warming and its ocean structure since 2006. Nat. Clim. Chang. 5, 240–245 (2015).

Rintoul, S. R. The global influence of localized dynamics in the Southern Ocean. Nature 558, 209–218 (2018).

Liu, W. et al. Southern Ocean heat uptake, redistribution, and storage in a warming climate: The role of meridional overturning circulation. J. Clim. 31, 4727–4743 (2018).

Fyfe, J. C., Boer, G. J. & Flato, G. M. The Arctic and Antarctic oscillations and their projected changes under global warming. Geophys. Res. Lett. 26, 1601–1604 (1999).

Cai, W., Shi, G., Cowan, T., Bi, D. & Ribbe, J. The response of the Southern Annular Mode, the East Australian Current, and the southern mid-latitude ocean circulation to global warming. Geophys. Res. Lett. 32, L23706 (2005).

Russell, J., Dixon, K., Gnanadesikan, A., Ronald, S. & Toggweiler, J. R. The Southern Hemisphere Westerlies in a Warming World: Propping Open the Door to the Deep Ocean. J. Clim. 19, 6382–6390 (2006).

Kidston, J. & Gerber, E. P. Intermodel variability of the poleward shift of the austral jet stream in the CMIP3 integrations linked to biases in 20th century climatology. Geophys. Res. Lett. 37, L09708 (2010).

Bracegirdle, T. J. et al. Assessment of surface winds over the Atlantic, Indian, and Pacific Ocean sectors of the Southern Ocean in CMIP5 models: Historical bias, forcing response, and state dependence. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 118, 547–562 (2013).

Rayner, N. A. et al. Global analyses of sea surface temperature, sea ice, and night marine air temperature since the late nineteenth century. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 108, 4407 (2003).

Kalnay, E. et al. The NCEP/NCAR 40-year reanalysis project. Bull. Am. Meteor. Soc. 77, 437–472 (1996).

Compo, G. P. et al. The Twentieth Century Reanalysis Project. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 137, 1–28 (2011).

Lyu, K., Zhang, X. & Church, J. A. Projected ocean warming constrained by the ocean observational record. Nat. Clim. Chang. 11, 834–839 (2021).

Hall, A. et al. Progressing emergent constraints on future climate change. Nat. Clim. Chang. 9, 269–278 (2019).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the World Climate Research Programme’s Working Group on Coupled Modelling, which led the design of CMIP6 and coordinated the work, and we also thank individual climate modeling group (listed in Supplementary Table 1) for their effort in model simulations and projections. GW and AS are supported by the Earth Systems and Climate Change Hub of the Australian Government’s National Environmental Science Program. We also acknowledge the helpful discussions with Dr. Kewei Lyu from Xiamen University about the CMIP6 de-drift, and discussions about the manuscript with Drs. Xuebin Zhang and Benjamin Ng from CSIRO, Prof. Sang-Wook Yeh from Hanyang University, and Prof. Michael McPhaden from NOAA.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.W. conceived the study and wrote the initial manuscript. G.W. performed data analysis and generated final figures. W.C., A.S., and K. Y. contributed to interpreting results, discussion of the associated dynamics, and improvement of this paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, G., Cai, W., Santoso, A. et al. Southern Ocean heat buffer constrained by present-day ENSO teleconnection. npj Clim Atmos Sci 7, 181 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-024-00731-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-024-00731-0