Abstract

Atmospheric moisture transport is pivotal in regulating water resources over the Tibetan Plateau (TP). With the growing concerns about climate change, understanding the evolution of atmospheric moisture transport over the TP has become increasingly critical. however, the spatiotemporal distinctions of this transport remain poorly understood in the CMIP6 models. Here, we conducted a comprehensive evaluation of simulated historical atmospheric moisture transport from 33 CMIP6 models, utilizing a novel methodology that assesses the accuracy of model simulations in replicating regional atmospheric moisture transport over the TP. Our results indicate that the CMIP6 models generally succeed in reproducing the broad spatial patterns of atmospheric moisture transport. Nonetheless, substantial errors occur during the monsoon period, primarily attributable to inaccuracies in the location, movement, and intensity of the simulated Indian summer monsoon. The coarser resolution and poor representation of physical processes are potential reasons for errors in atmospheric moisture transport simulation over the TP. The Failure to simulate the terrain blocking on atmospheric moisture transport exacerbates these deficiencies, leading to significant discrepancies. Of the 33 CMIP6 models we investigated, over one-third displayed serious deficiencies in this regard. While coarser resolution and orographic gravity waves are plausible factors, they do not fully account for all the results obtained in this study. Insufficiently detailed or inaccurate topographic data used in the models may also contribute to this deficiency. This study highlights the necessity of using rigorously evaluated models to develop effective regional adaptation strategies over the Tibetan Plateau.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Tibetan Plateau (TP), also known as the Asian Water Tower1,2, has an average altitude exceeding 4000 m and is the source of Asia’s major rivers, including the Yellow, Yangtze, Brahmaputra, and Indus Rivers. It supports the livelihoods, agricultural, and industrial water needs of nearly 40% of the world’s population3,4. Its unique geography triggers atmospheric moisture pumping from as far away as the Indian Ocean and Western Pacific Ocean5. Atmospheric moisture transport is then integrated into the local water cycle through precipitation and contributes to recharging water resources over the TP6,7,8. Changes in atmospheric moisture transport are primarily driven by alterations in atmospheric circulation9. Over the TP, Atmospheric moisture transport is predominantly influenced by mid-latitude westerlies and the Indian summer monsoon10,11. Furthermore, variations in atmospheric moisture transport are associated with heterogeneous changes in the cryosphere12,13. Yao et al. (2012) found that from 1979–2010, the weakening of the Indian monsoon and the strengthening of westerlies led to differing patterns of change in glaciers and precipitation over the TP. Gao et al. 13 have demonstrated that three factors are responsible for the general wetting trend over the TP, namely the poleward shift of the East Asian westerly jet stream, poleward moisture transport, and the intensification of the summer monsoon. Additionally, changes in atmospheric moisture transport have been linked to the spatial expansion of inland lakes on the TP14,15.

TP has been experiencing more intensive warming than the global average over the past decades. Understanding the spatiotemporal variability of atmospheric moisture transport along with the warming around the TP is therefore essential for understanding changes in the regional water cycle, which is crucial for developing regional adaptation strategies for future climate change. Simulations from reliable climate models are necessary to investigate future spatiotemporal variations of atmospheric moisture transport. Previous studies suggested that some models can capture the spatial and seasonal variability of atmospheric moisture transport under the westerlies and the Indian summer monsoon, and they also find that the simulated sea surface temperatures in the Arabian Sea and model resolutions are two crucial factors affecting the simulation16,17,18,19. The Coupled Model Intercomparison Project 6 (CMIP6), implement increased spatial resolutions (both horizontal and vertical) and more sophisticated physics in the new generation of GCMs20,21. Studies have confirmed that the multi-model ensemble (MME) from CMIP6 shows superior skills in simulating mean Indian summer monsoon rainfall compared to previous generations of CMIP models22. To date, however, no comprehensive evaluation in the historical simulation of atmospheric moisture transport over the TP from CMIP6 models has been conducted, it will introduce large uncertainty for investigating future regional water cycle.

In-situ observations are crucial but insufficient for evaluating model performance, particularly in TP where observational data is sparse. Consequently, high-resolution re-analysis data and remote sensing data are frequently utilized as references. Maussion et al.23 and Mölg et al.24 demonstrated that the High Asia Refined analysis data (HAR) reliably represents historical climates over the TP when compared with the Tropical Rainfall Measuring Mission (TRMM) data set23,24. The HAR data has since been updated to version 2 (HAR v2), which incorporates forcing data from ERA5 instead of FNL, extends temporal coverage, expands the domain by 10 km, and enhances the accuracy of seasonal mean precipitation25.

In this study, HAR v2 data is employed to evaluate the performance of CMIP6 models in simulating atmospheric moisture transport over the TP. We examine the monthly spatial variations of atmospheric moisture transport and identify six representative spatial characteristics. These characteristics serve as benchmarks to assess deficiencies in 33 CMIP6 models. The TP border is subdivided into 13 transects (details provided in the Methods section), and we investigate the profile of atmospheric moisture received by each transect, along with their statistical characteristics.

Our analysis evaluates the simulation performance of the 33 CMIP6 models and explores the reasons behind significant discrepancies among these models. We apply a novel evaluation methodology that accounts for the complexity of the TP border and the non-uniformity of inflow, enables us to rank the 33 CMIP6 models based on their performance during monsoon and non-monsoon periods. This comprehensive assessment aims to enhance our understanding of atmospheric moisture transport over the TP and improve the accuracy of climate simulations.

Results

Spatial patterns of atmospheric moisture transport

Two principal atmospheric circulations (the mid-latitude westerlies and the Indian summer monsoon) exert significant influence over the TP, as illustrated by monthly variations in atmospheric moisture transport derived from HAR v2 (Fig. 1). The Karakoram Mountains induce bifurcation of the mid-latitude westerlies into northern and southern branches along the borders of the TP. From June to September, the Indian summer monsoon affect the TP, transporting atmospheric moisture along southwestern and southeastern pathways, marking the monsoon period over the TP. The remaining months are categorized as the non-monsoon period. The spatial patterns of atmospheric moisture transport around the TP exhibit marked seasonal shifts influenced by the transition between the mid-latitude westerlies and the Indian summer monsoon. From October to April, the TP is predominantly affected by mid-latitude westerlies, resulting in a relatively stable spatial pattern (Fig. 1j–l, a–d). The southern branch of mid-latitude westerlies (hereafter referred to as the southern branch) primarily transports atmospheric moisture to the southwestern and southeastern TP. The atmospheric moisture carried by the southern branch increased by 86.6% (from 116.6 \({\rm{kg}}\,{{\rm{m}}}^{-1}\,{{\rm{s}}}^{-1}\) to 217.6 \({\rm{kg}}\, {{\rm{m}}}^{-1}\, {{\rm{s}}}^{-1}\) on average), when arriving at the Yarlung Tsangpo Grand Canyon (transect 6) during this period. In contrast, the northern branch carries significantly less atmospheric moisture to Qaidam Basin (transect 9). In May, the TP remains under the dominance of the mid-latitude westerlies, although the southern branch exhibits increasing meridionality (Fig. 1e). In June, the onset of the Indian summer monsoon introduces a distinct northward component, altering the direction of atmospheric moisture transport towards the Yarlung Tsangpo Grand Canyon from the west to the southwest, with directional angles increasing from 30 degrees to nearly 60 degrees relative to the east within a month (Supplementary Fig. 1). With the development of Indian summer monsoon, the southern branch retreats westward to near 85oE (near transect 3). The interaction between southern branch and Indian summer monsoon leads to the formation of a slight cyclone near 85–90°E (Fig. 1f). In July, the Indian summer monsoon is divided into two flows along southwestern and southeastern paths, creating a pronounced moisture gradient (Fig. 1g). The boundaries of two flows can be defined in terms of moisture gradient. The southeastern flow strengthens by an average of 146.7 \({\rm{kg}}\, {{\rm{m}}}^{-1}\, {{\rm{s}}}^{-1}\) and expands to around 80°E, associated with a sharp decrease in the southern branch’s influence. In August, the very moist southeastern flow extends further to around 78°E, while the atmospheric moisture carried by the southwestern flow decreases by 49.6 \({\rm{kg}}\, {{\rm{m}}}^{-1}\, {{\rm{s}}}^{-1}\). In September, the southeastern flow begins to retreat to east of 80oE, while the southern branch regains some of its strength.

Considering the seasonal shifts of the mid-latitude westerlies and Indian summer monsoon, six representative spatial characteristics of atmospheric moisture transport (Table 1) are established as criteria for evaluating deficiencies in simulating atmospheric moisture transport from 33 CMIP6 models.

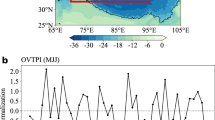

Inflow profiles of atmospheric moisture transport

Map of atmospheric moisture transport is intuitive to reflect the spatial pattern, but it is hard to clarify the amount received on different transect. Inflow profiles of atmospheric moisture transport (hereafter to referred as inflow profiles, see the Methods section for details) provides a clearer quantification of moisture received across various transects, addressing the limitations of spatial pattern representations by maps alone. We calculate the annual inflow (Fig. 2a) and monthly contributions (Fig. 2b) through all 13 transects using data from HAR v2. the combined annual inflow during the non-monsoon period is approximately 1.2 times higher than that during the monsoon period (\(11.09\times {10}^{8}{\rm{kg}}\, {{\rm{s}}}^{-1}\) and \(9.32\times {10}^{8}{\rm{kg}}\, {{\rm{s}}}^{-1}\), respectively), possibly due to the longer duration of the non-monsoon period. Transects 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, and 9 are the top six transects received inflow, which account for 87% of the total inflow into the TP. The highest inflow (\(6.1\times {10}^{8}{\rm{kg}}\, {{\rm{s}}}^{-1}\)) occurs through transect 6, while the remaining five key transects each (transects 1, 2, 3, 4, and 9) exceed \(1.5\times {10}^{8}{\rm{kg}}\, {{\rm{s}}}^{-1}\). The transects 1, 2, and 6 receive higher inflows during the non-monsoon period compared to the monsoon period, a phenomenon linked to the prevailing seasonal patterns, which will be elaborated upon later in this section. Regarding relative contributions, transects other than 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, and 9 do not surpass the 8% threshold throughout the year (Fig. 2b), reinforcing their significance as the main transects to receives inflow. Consequently, these six transects are designated for focused analysis in subsequent studies. It is noteworthy that transect 9, situated on the northern border of the TP, receives 56% of the inflow into the northern border, significantly surpassing the adjacent transect 10, which only accounts for 26% of the inflow. This disparity highlights the pivotal role of transect 9 in northern TP atmospheric moisture transport.

Figure 2c presents the seasonal patterns of inflow on main transects. Overall, we can divide these seasonal patterns into three types. The first type is unimodal with an inflow that is mainly concentrated in the monsoon period, transects 3, 4, and 9 are of this type. The second type has stable inflow with no evident temporal fluctuation, transect 1 matches this type, which has considerable inflow during non-monsoon period with higher values than those in monsoon period. The third type we have labeled “M” pattern, and it has at least one peak outside the monsoon period, transects 2 and 6 are of this type. For “M” pattern, low inflow occurs in monsoon period, it would also lead to higher inflow in non-monsoon period. All these seasonal patterns are a result of the prevailing atmospheric circulations. Transects 3 and 4 that characterized by unimodal patterns implying that these transects are mainly affected by the Indian summer monsoon. In addition, transect 3 exhibits a slight difference. The inflow fluctuates during the monsoon period, indicating that transect 3 lies within the transition area between mid-latitude westerlies and Indian summer monsoon. The alternation of prevailing atmospheric circulation results in fluctuation of inflow. Transect 1, which is influenced solely by mid-latitude westerlies, exhibits a stable pattern, indicating that the impact of the mid-latitude westerlies on this transect remains consistent throughout the year. In contrast, transects 2 and 6 present a more complex scenario. Despite sharing the same “M” pattern, the factors influencing these transects are not as straightforward. For transect 2, the first peak occurs in March due to the southern branch gradually aligning parallel to this transect from April onwards. This will continue until July, associated with a continuous decline of inflow from March to June. The second peak occurs in August when the expansion of the southeastern flow reaches its maximum, leading to convergence with the southern branch at transect 2. For transect 6, the first peak occurs in June, which coincides with the westward expansion and movement of Indian summer monsoon. This results in a continuous reduction in inflow from June to August. The second peak for transect 6 occurs when the Indian summer monsoon shrinks back to this transect. There is a clear temporal correspondence between the peaks and troughs of transects 2 and 6 and the southeastern flow, indicating that the southeastern flow is the primary mechanism modulating the changes in inflow on these transects. Further analysis is required to understand the varying contributions of different atmospheric processes to these transects across different seasons. This understanding is crucial for improving the accuracy of regional climate models and predicting future changes in atmospheric moisture transport over the Tibetan Plateau. The vertical boundaries of inflow profiles typically range between 800-300 hPa (Fig. 3). Pronounced and efficient inflow channels (hereafter referred to as channels) on transects 2, 3, 4, 6 and 9 are more prominent during the monsoon period. Inflow rates into these channels generally exceed \(2\times {10}^{-2}{\rm{kg}}\, {{\rm{m}}}^{-2}\, {{\rm{s}}}^{-1}\). These channels predominantly align with canyons along the TP border, typically at altitudes below 600 hPa. However, at least three channels are observed above mountaintops of the Himalayas (transect 4) during the monsoon period, reaching altitudes of nearly 500 hPa (Fig. 3h). This phenomenon indicates that moisture climbing-transport process significantly contributes to the recharge of water resources. The inflow profiles on transect 1, primarily influenced by mid-latitude westerlies, display relatively consistent characteristics during the monsoon and non-monsoon periods. In contrast, no distinct inflow profiles are observed on transects 3 and 4 during the non-monsoon period, as these transects are predominantly affected by the Indian summer monsoon. The inflow profiles on transects 2 and 6 corroborate their alignment with the southeastern flow. We provide the inflow profiles of these two transects from January to December (Supplementary Figs. 2, 3). For transect 6, inflow decreases dramatically from July to August due to the westward extension of the southeastern flow, particularly on the eastern side of the transect 6. Correspondingly, channels are observed on the transect 2 exclusively during these two months.

The performances of simulation from 33 models in atmospheric moisture transport

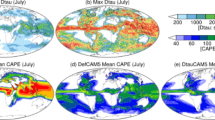

Here we provided the results of simulated atmospheric moisture transport over the TP from 33 CMIP6 models for the months of April, June, July, and September (Supplementary Figs. 4-7). These months were selected based on their representation of the TP being influenced by mid-latitude westerlies and the Indian summer monsoon (Fig. 1). 33 CMIP6 models successfully reproduce the general spatial patterns of atmospheric moisture transport, with better performance during the non-monsoon period. For details, however, significant deficiencies persist, particularly during the monsoon period. In non-monsoon period, the simulations typically underestimate the atmospheric moisture transport when arriving at Yarlung Tsangpo Grand Canyon (Supplementary Fig. 8). This underestimation is primarily due to an excessively flat simulated southern branch, which results in a significant amount of atmospheric moisture being transported eastward rather than towards the southeastern TP. Notable models displaying this behavior include FGOALS-g3, MCM-UA-1-0, E3SM-1-0, and E3SM-1-1.

During the monsoon period, there are considerable errors in simulating the spatial details of moisture transport. These inaccuracies are primarily attributed to errors in the location, movement, and intensity of the simulated Indian summer monsoon. Specifically, in June, the models fail to adequately capture the rapid transition from non-monsoon to monsoon conditions. The angles of the simulated Indian summer monsoon toward the Yarlung Tsangpo Grand Canyon are generally obvious less than 60 degrees relative to the east in most CMIP6 models (Supplementary Fig. 9). This misalignment hinders the accurate representation of spatial characteristics, such as the slight cyclone near 85-90°E and the retreat of the southern branch. From July to September, the models exhibit substantial errors in simulating the characteristics, extent, and intensity of the southeastern flow. For instance, from July to August, models such as CESM2, CESM2-WACCM, E3SM-1-0, E3SM-1-1, EC-Earth3, INM-CM5-0, and MIROC6 depict the southeastern flow with an inaccurate deflection, thereby failing to transport moisture along the designated transect 3 (Supplementary Fig. 6). Another fatal deficiency is that like ACCESS-CM2, ACCESS-ESM1-5, BCC-ESM1, CanESM5, CIESM, KACE-1-0-G, MCM-UA-1-0, MRI-ESM2-0, NorCMP1, NorESM2-LM, SAM0-UNICON, and TaiESM1 even fail to simulate the expansion of the southeastern flow. In September, the retreat of the southeastern flow to east of 80oE did not occur in time in BCC-CSM2, CESM2, CESM2-FV2, CESM2-WACCM, CIESM, E3SM-1-0, E3SM-1-1, IPSL-CM6A-LR, MPI-ESM1-2-HR, MPI-ESM1-2-LR, NESM3, NorESM2-MM, SAM0-UNICON, and TaiESM1 (Supplementary Fig. 7). Some models simulate the Indian summer monsoon retreating south too quickly, causing unreal eastward transport of the southern branch along transects 3 and 4. Examples include CIESM, E3SM-1-0, E3SM-1-1, FGOALS-f3-L, FGOALS-g3. These findings underscore the necessity for further refinement in model simulations to improve the accuracy of atmospheric moisture transport predictions over the TP, particularly during monsoon period.

Due to the elevation of the TP, which far exceeds the surroundings, no atmospheric moisture is transported into the TP below 800 hPa (Fig. 3). Among the 33 CMIP6 models we investigated, however, 14 models erroneously simulated atmospheric moisture transport below this level, including BCC-CSM2-MR, BCC-ESM1, CanESM5, EC-Earth3, EC-Earth3-Veg, FIO-ESM-2-0, MPI-ESM-1-2-HAM, MPI-ESM1-2-HR, MPI-ESM1-2-LR, NESM3, NorCPM1, NorESM2-LM, NorESM2-MM, and TaiESM1 (Supplementary Fig. 10). Although the other models can account for the terrain blocking, they still fail to capture the specific inflow features due to limited spatial resolution (Supplementary Fig. 11). The inability to accurately simulate the terrain blocking on atmospheric moisture transport over the TP exacerbates existing deficiencies. During non-monsoon period, very minimal atmospheric moisture is transported into the TP. If a model fails to simulate the terrain blocking, the mid-latitude westerlies will transport excessive moisture into the TP through transects 2 and 3, leading to a serious overestimation of atmospheric moisture (Fig. 4, top row). During the monsoon period, models that do not capture the terrain blocking produce significantly distorted results over the TP (Fig. 4, second to bottom row). Instead of being blocked and redirected near the southwestern TP border (transects 2 and 3), atmospheric moisture is incorrectly transported directly into the TP interior. This erroneous transport combines with the unobstructed atmospheric moisture transport through transects 4, 5, 6, and 9, resulting in a widespread and inaccurate moisture convergence over the TP.

Ranking of 33 CMIP6 models

Due to the complexity of the TP border and the presence of channels in the inflow profiles, previous methodologies for evaluating simulations of the atmospheric moisture transport are inadequate26,27. Those methods oversimplify the situation and fail to account for the non-uniformity in the inflow profiles. We therefore propose a novel evaluation methodology that accounts for the intricate TP border and the variability in the inflow profiles. This methodology encompasses three primary steps: 1) Delimitation of Assessing Profiles: For each main transect, we delineate one or more sub-inflow profiles (referred to as assessing profiles) to capture the characteristics of the inflow profiles (Fig. 5). We identified a total of 17 assessing profiles for the monsoon period and 16 for the non-monsoon period. The delimitation of assessing profiles differs between the monsoon and non-monsoon periods on transects 2 and 4 due to significant variations in inflow characteristics during these times. 2) Annual Inflow Calculation: In one assessing profile, we calculated the annual totals of inflow, generating a 30-year time series (1985-2014) for all 33 CMIP6 models. 3) Error Analysis: We then computed the root-mean-squared errors (RMSE) of these time series against the HAR v2. By sorting the models based on their RMSE, we identified and recorded the top third of models in one assessing profile. Repeating the steps 2 and step 3 for all 17 assessing profiles during the monsoon period and 16 during the non-monsoon period, we derived the evaluation results (Fig. 6). Notably, only 19 out of 33 CMIP6 models appeared in the top third at least once during the monsoon period, and 16 models during the non-monsoon period. The top-performing models during the monsoon period were CESM2, CIESM, E3SM-1-0, CESM2-WACCM, and FGOALS-f3-L. During the non-monsoon period, the best-performing models were CIESM, E3SM-1-0, INM-CM4-8, INM-CM5-0, and FGOALS-f3-L. This refined methodology offers a more nuanced and accurate assessment of atmospheric moisture transport simulations over the Tibetan Plateau, ensuring that the complex topographical and climatic features are adequately represented. The implications of these findings are significant for improving predictive models and understanding regional climate dynamics.

Sub-inflow profiles (assessing profiles) [\({10}^{-2}\,{\rm{kg}}\,{{\rm{m}}}^{{{-}}{2}}\,{{\rm{s}}}^{{{-}}{1}}\)] on the (a) Transect 1. b Transect 2 in non-monsoon period. c Transect 2 in monsoon period. d Transect 3. e Transect 4 in non-monsoon period. f Transect 4 in monsoon period. g Transect 6. h Transect 9. Besides the transects 2 and 4, the delimitation of assessing profiles is identical in monsoon and non-monsoon periods.

Discussion

This study provides the comprehensive evaluation of atmospheric moisture transport over the TP through a novel methodology with simulations from 33 CMIP6 models. Previous studies have indicated the minimal improvement in modeling atmospheric moisture transport around the TP over the last two decades of the CMIP, particularly concerning the Indian summer monsoon and its spatiotemporal features28,29. our findings confirm significant discrepancies and substantial errors in simulating spatial patterns of atmospheric moisture transport during the monsoon period over the TP among the 33 CMIP6 models. These inaccuracies are primarily due to the errors of the location, movement, and intensity of the simulated Indian summer monsoon. Sperber et al.28 noted that a late onset of Indian summer monsoon is common to both sets of CMIP3 and CMIP5 models. This deficiency persists in CMIP6 models, such as ACCESS-CM2, ACCESS-ESM1-5, CIESM, FGOALS-g3, IPSL-CM6A-LR, KACE-1-0-G, MRI-ESM2-0, and several CESM2 and INM-CM models. Saha and Singh (2023) evaluated the performance of 12 CMIP6 models to simulate the properties of Indian summer monsoon. They find that the ACCESS-CM2 and IPSL-CM6A-LR fail to simulate the climatological parameters of Indian summer monsoon, consistent with our results. In general, these deficiencies can be attributed to the coarser resolution, poor representation of physical processes, and inadequate boundary and initial conditions30,31. Bi et al. demonstrated that the coarser resolution could lead to a large SST bias over the Indian Ocean, affecting the simulations of Indian summer monsoon32. Similarly, a coarser resolution can also result in a dry bias over the Indian subcontinent and thus leading to failure in simulating Indian summer monsoon33,34. In addition, Yang et al. found that the black carbon aerosols can enhances the vertical convection and cloud condensation over the Indian subcontinent, the primary moisture source for the southern TP, resulting in reduced atmospheric moisture transport to the southern TP35,36. Singh et al. (2018) suggested that there are significant inter-model differences in the simulation of aerosols in CMIP537. Jaisanker et al. (2024) found that the CMIP5 and CMIP6 models underestimated the mean annual aerosol optical depth (AOD) of the Indian region as a whole, which can be attributed to the accuracy of emission datasets38. This is a potential reason for errors in atmospheric moisture transport simulation over the TP.

The failure to simulate the terrain blocking on atmospheric moisture transport over the TP further amplifies these deficiencies and results in significant discrepancies. Of the 33 CMIP6 models we investigated, over one third of the models displayed this serious deficiency. One possible reason is that the model spatial resolution is too coarse to represent high mountains39,40, and thus the terrain blocking. However, this explanation is insufficient. Even the models with the highest horizontal resolution of 100 km in this study (e.g., BCC-CSM2-MR, EC-Earth3, EC-Earth3-Veg, FIO-ESM-2-0, MPI-ESM1-2-HR, NorESM2-MM and TaiESM1), still fail to avoid this deficiency. In contrast, some model with lower spatial resolution (e.g., MIROC6 with 250 km) can better simulate the terrain blocking.

Another potential reason is the Orographic gravity waves (OGWs). OGWs are an important mechanism for coupling of the free atmosphere with the surface, influencing the dynamics and circulation41. Hájková and Šácha (2024) reviewed 7 OGW parameterization schemes used in 9 CMIP6 models. They reported pronounced differences in the vertical distribution and magnitude of the parameterized OGW drag42. Nevertheless, OGWs do not fully elucidate this deficiency. Both CanESM5 and CESM2 are equipped with the OGW parameterization scheme developed by Scinocca and McFarlene (2000)43, yet only CanESM5 presents this serious deficiency. In addition, vertical coordinate may also contribute to this serious deficiency. The hybrid terrain-following coordinate, commonly used in models, shows the terrain influences on coordinate surfaces decrease more rapidly with height compared to the linear decrease in the basic sigma coordinate44,45. The calculations below the terrain are eliminated. However, this process depending on detailed and accurate topographic data.

Enhancing the accuracy of models is crucial for better understanding and predicting climate dynamics over the TP. The 33 CMIP6 models demonstrated significant discrepancies in simulating historical atmospheric moisture transport over the TP. Failure to account for the terrain blocking not only distorts moisture transport simulations but also impacts the reliability of climate projections in this region. Besides the terrain blocking, the selection of different dynamics schemes, physical processes, initial and boundary conditions, and forcing data can also lead to great discrepancies. This highlights the necessity of using rigorously evaluated models for future climate projections to provide more accurate representations of atmospheric processes over the TP for the development of effective regional adaptation strategies.

Methods

Data

We retrieved monthly northward and eastward wind, as well as water vapor mixing ratios during the period of 1985-2014 from HAR v2 (www.klima.tu-berlin.de/HARv2). HAR v2 is a regional high resolution atmospheric data set generated via dynamical downscaling of global ERA5 reanalysis data using the Weather Research and Forecasting (WRF) model25. HAR v2 has a spatial resolution of 10 km with different time aggregation levels: hourly, daily, monthly, and yearly. Compared to its predecessor, HAR v2 has an extended 10 km domain covering the TP and surrounding mountains.

Historical (1985–2014) simulations using 33 CMIP6 models were retrieved from the Earth System Grid Federation database (https://esgf-node.llnl.gov/search/cmip6). Basic information about 33 models is listed in Table 2. We used the monthly northward and eastward wind, as well as specific humidity.

Division for 13 transects

Given the extremely complex boundaries and variable winds around the TP, it will introduce great uncertainty if only focusing atmospheric moisture transport in four directions. Therefore, it’s imperative to demarcate the border based on the potential pathways for atmospheric moisture transport. Previous studies by Curio et al. (2014)46 and Zhao et al. (2021)47 defined 14 transects attempting to follow the highest elevations in the mountain ranges. However, the main principle for determining the boundary of the TP is the mountain top above 4000 m a. s. l48. In this study, we adjusted the position of transect 6 and combined the transect 10 and transect 11 due to the similar orientations, resulting in a total of 13 transects attempting to follow the 4000 m a. s. l. in the mountain range and to cut cross the mountain valleys (Fig. 7). Each transect was given a suitable length to avoid smaller than the horizontal resolution of the CMIP6 models. The distribution of 13 transects in model grid cells were provided in supplementary information (supplementary Fig. 12).

The black contours are the elevation of 4000 m a. s. l. over the TP. Length of each transect: transect 1: 389.18 km; transect 2: 1092.30 km; transect 3: 826.52 km; transect 4: 611.57 km; transect 5: 370.30 km; transect 6: 637.22 km; transect 7: 1200.90 km; transect 8: 475.02 km; transect 9: 1025.20 km; transect 10: 587.23 km; transect 11: 561.40 km; transect 12: 471.76 km; transect 13: 222.39 km.

Atmospheric moisture transport

Atmospheric moisture transport is commonly expressed by the water vapor flux in an atmospheric column, which can be calculated as

ρ is the air density (\({\rm{kg}}\,{{\rm{m}}}^{-3}\)), q denotes the specific humidity (\({\rm{kg}}\,{{\rm{kg}}}^{-1}\)), and v is the horizonal wind vector (\({\rm{m}}\,{{\rm{s}}}^{-1}\)). Since HAR v2 only provides the mixing ratio r \(({\rm{kg}}\,{{\rm{kg}}}^{-1})\), we first calculate the specific humidity by:

Total air column water vapor flux is calculated by integrating the water vapor fluxes over the whole air column:

where Q is the vertically integrated water vapor flux (\({\rm{kg}}\, {{\rm{m}}}^{-1}\, {{\rm{s}}}^{-1}\)), \({{\rm{p}}}_{{\rm{top}}}\) and \({{\rm{p}}}_{{\rm{surf}}}\) represent the pressure at the top atmosphere and surface, respectively, while g is acceleration by gravity (\(9.8{\rm{Pa}}\, {{\rm{m}}}^{2}\, {{\rm{kg}}}^{-1}\)).

Inflow profile

We calculate perpendicular vector values of atmospheric moisture transport relative to the transect as the inflow. Thus:

where \({{\rm{q}}}_{{\rm{flux}},{\rm{input}}}\) is the inflow and θ is the angle between the atmospheric moisture transport and the transect.

Inflow profiles can be obtained by calculating the inflow at each atmosphere level along a transect. Ideally, this involves identifying the grid cells that intersect with the transect to derive the inflow profile. However, due to the mismatches between the grid cells and the transect locations, we first identify grid cells within 30 km of the transect. The transect is then discretized into n equally spaced points. For each point, the nearest grid cells are used to calculate the mean inflow. At the junction of the two transects, the overlapping grid cells are used only for the subsequent transect to prevent double counting. This procedure is repeated for each atmosphere level and transect to obtain the inflow profiles on 13 transects.

Data availability

HAR v2 was downloaded from: https://www.klima.tu-berlin.de/HARv2. The 33 CMIP6 historical simulations used in this study are available at https://esgf-node.llnl.gov/projects/cmip6/.

Code availability

The source codes for the analysis of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Immerzeel, W. W. et al. Climate change will affect the Asian water towers. Science 328, 1382–1385 (2010).

Gao, J. et al. Collapsing glaciers threaten Asia’s water supplies. Nature 565, 19–21 (2019).

Xu, X. et al. World water tower: an atmospheric perspective. Geophys. Res. Lett. 35, L20815 (2008).

Yao, T. et al. Reflections and future strategies for third pole environment. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 3, 608–610 (2022).

Wu, G. & Zhang, Y. Tibetan Plateau forcing and the timing of the monsoon onset over South Asia and the South China Sea. Mon. Wea. Rev. 126, 913–927 (1998).

Xu, X. et al. The relationship between water vapor transport features of Tibetan Plateau-Monsoon “LArge Triangle” Affecting Region and Drought-flood Abnormality of China. Acta Meteorol. Sin. 60, 257–266 (2002).

Zhang, Y. et al. Spatial distributions and seasonal variations of tropospheric water vapor content over the Tibetan Plateau. J. Clim. 26, 5637–5654 (2013).

Sun, L. et al. Summertime atmospheric water vapor transport between Tibetan Plateau and its surrounding regions during 1990–2019: Boundary discrepancy and interannual variation. Atmos. Res. 275, 106237 (2022).

Gimeno, L. et al. On the origin of continental precipitation. Geophys. Res. Lett. 37, L13804 (2010).

Zhou, T. & Yu, R. Atmospheric water vapor transport associated with typical anomalous summer rainfall patterns in China. J. Geophys. Res. 110, D08104 (2005).

Rangwala, I. et al. Warming in the Tibetan Plateau: Possible influences of the changes in surface water vapor. Geophys. Res. Lett. 36, L06703 (2009).

Yao, T. et al. Different glacier status with atmospheric circulations in Tibetan Plateau and surroundings. Nat. Clim. Change 2, 663–667 (2012).

Gao, Y. et al. Changes in Moisture Flux over the Tibetan Plateau during 1979–2011 and Possible Mechanisms. J. Clim. 27, 1876–1893 (2014).

Yang, K. et al. Recent climate changes over the Tibetan Plateau and their impacts on energy and water cycle: A review. Glob. Planet. Change 112, 79–91 (2014).

Zhang, G. et al. A robust but variable lake expansion on the Tibetan Plateau. Sci. Bull. 64, 1306–1309 (2019).

Lin, C. et al. Impact of model resolution on simulating the water vapor transport through the central Himalayas: implication for models’ wet bias over the Tibetan Plateau. Clim. Dyn. 51, 3195–3207 (2018).

Jain, S. et al. Performance of CMIP5 models in the simulation of Indian summer monsoon. Theor. Appl Climatol. 137, 1429–1447 (2019).

Yamagami, Y. et al. Impacts of oceanic mesoscale structures on sea surface temperature in the Arabian Sea and Indian summer monsoon revealed by climate model simulations. J. Clim. 36, 5477–5490 (2023).

Yao, T. et al. A review of climatic controls on δ18O in precipitation over the Tibetan Plateau: observations and simulations. Rev. Geophys. 51, 525–548 (2013).

Stouffer, R. J. et al. CMIP5 Scientific Gaps and Recommendations for CMIP6. Bull. Am. Meteorological Soc. 98, 95–105 (2017).

Jiang, J. et al. Improvements in cloud and water vapor simulations over the tropical oceans in CMIP6 compared to CMIP5. Earth Space Sci. 8, e2020EA001520 (2021).

Rajendran, K. et al. Simulation of Indian summer monsoon rainfall, interannual variability and teleconnections: evaluation of CMIP6 models. Clim. Dyn. 58, 2693–2723 (2022).

Maussion, F. et al. WRF simulation of a precipitation event over the Tibetan Plateau, China – an assessment using remote sensing and ground observations. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 15, 1795–1817 (2011).

Mölg, T. et al. Mid-latitude westerlies as a driver of glacier variability in monsoonal High Asia. Nat. Clim. Change 4, 68–73 (2014).

Wang, X. et al. WRF-based dynamical downscaling of ERA5 reanalysis data for High Mountain Asia: Towards a new version of the High Asia Refined analysis. Int. J. Climatol. 41, 743–762 (2021).

Yu, J. et al. Long-term trend of water vapor over the Tibetan Plateau in boreal summer under global warming. Sci. China Earth Sci. 65, 662–674 (2022).

Xu, K. et al. A study on the water vapor transport trend and water vapor source of the Tibetan Plateau. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 140, 1031–1042 (2020).

Sperber, K. R. et al. The Asian summer monsoon: an inter- comparison of CMIP5 vs. CMIP3 simulations of the late 20th century. Clim. Dyn. 41, 2711–2744 (2013).

Wang, Z. et al. Origin of Indian summer monsoon rainfall biases in CMIP5 multimodel ensemble. Clim. Dyn. 51, 755–768 (2018).

Gusain, A. et al. Added value of CMIP6 over CMIP5 models in simulating Indian summer monsoon rainfall. Atmos. Res. 232, 104680 (2020).

Singh, C. Intra-seasonal oscillations of South Asian summer monsoon in coupled climate model cohort CMIP6. Clim. Dyn. 60, 179–199 (2023).

Bi, D. et al. Configuration and spin-up of ACCESS-CM2, the new generation Australian community climate and earth system simulator coupled model. J. South. Hemisph. Earth Syst. Sci. 70, 225–251 (2020).

Sooraj, K. P. et al. Global warming and the weakening of the Asian summer monsoon circulation: assessments from the CMIP5 models. Clim. Dyn. 45, 233–252 (2015).

Swapna, P. et al. The IITM earth system model: transformation of a seasonal prediction model to a long-term climate model. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 96, 1351–1367 (2015). 13-00276.1.

Yang, J. et al. South Asian black carbon is threatening the water sustainability of the Asian Water Tower. Nat. Commun. 13, 1–13 (2022).

Yang, J. et al. Monsoon precipitation decrease due to black carbon also causes glacier mass decline over the southeastern Tibetan Plateau. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 120, e2301016120 (2023).

Singh, C. et al. On the dust load and rainfall relationship in South Asia: An analysis from CMIP5. Clim. Dyn. 50, 403–422 (2018).

Jaisankar, B. et al. Spatio-temporal correspondence of aerosol optical depth between CMIP6 simulations and MODIS retrievals over India. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 31, 16899–16914 (2024).

Tang, Q. et al. Simulation of ENSO teleconnections to precipitation extremes over the US in the high resolution version of E3SM. J. Clim. 35, 1–62 (2021).

Bresson, H. et al. Case study of a moisture intrusion over the Arctic with the ICOsahedral Non-hydrostatic (ICON) model: resolution dependence of its representation. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 22, 173–196 (2022).

Holton, J. R. The role of gravity wave induced drag and diffusion in the momentum budget of the mesosphere. J. Atmos. Sci. 39, 791–799 (1982).

Hájková, D. et al. Parameterized orographic gravity wave drag and dynamical effects in CMIP6 models. Clim. Dyn. 62, 2259–2284 (2024).

Scinocca, J. et al. The parameterization of drag induced by stratified flow over anisotropic orography. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 126, 2353–2393 (2000).

Simmons, A. et al. An energy and angular-momentum conserving finite-difference scheme and hybrid vertical coordinates. Mon. Wea. Rev. 109, 758–766 (1981).

Choi, S. et al. A New Hybrid Sigma-Pressure Vertical Coordinate with Smoothed Coordinate Surfaces. Mon. Wea. Rev. 149, 4077–4089 (2021).

Curio, J. et al. A 12-year high-resolution climatology of atmospheric water transport over the Tibetan Plateau. Earth Syst. Dyn. 6, 109–124 (2015).

Zhao, Y. & Zhou, T. Interannual variability of precipitation recycle ratio over the Tibetan Plateau. J. Geophys. Res.: Atmos. 126, e2020JD033733 (2021).

Yili, Z. et al. Redetermine the region and boundaries of Tibetan Plateau. Geographical Res. 40, 1543–1553 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by ‘The Second Tibetan Plateau Scientific Expedition and Research’ project (Grant No. 2019QZKK0208) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grants 41988101-03 and 41922002). We thank Yutong Zhao for supporting the processing of 33 CMIP6 historical simulations and Mathieu Casado and Cécile Agosta for improving paper quality.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.G.L.: Wrote original draft, Data processing, Visualization, Analysis. J.G.: Supervision, Reviewing, Editing, Analysis. Y.L.W.: Reviewing, Editing, Analysis.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, Y., Gao, J. & Wang, Y. Evaluation of atmospheric moisture transport to the Tibetan Plateau from 33 CMIP6 models. npj Clim Atmos Sci 7, 231 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-024-00785-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-024-00785-0