Abstract

Understanding the impacts of the Indonesian Throughflow (ITF) on the eastward propagation of the Madden-Julian Oscillation (MJO) is crucial for accurately simulating the MJO and achieving high-skill sub-seasonal predictions. Our analyses demonstrate a significant enhancement of MJO eastward propagation due to the strong ITF. Blocking the ITF decreases the eastward sea surface temperature (SST) gradient over the tropical Indian Ocean, hindering MJO propagation across the Maritime Continent (MC). Removing the MJO circulation-induced intraseasonal variability of the ITF transport also weakens the eastward propagation of the MJO, as the MJO easterly winds enhance the ITF transport and warm the eastern tropical Indian Ocean. These experiments reveal that mean and intraseasonal variability of the ITF transport contribute to 73% and 42% of the eastward propagation of the MJO over the MC, respectively. The findings presented in this study highlight the significant role of the ITF in shaping the propagation of the MJO.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The MJO, the most dominant intraseasonal variability in the tropical atmosphere, is characterized by a planetary-scale, eastward-moving tropospheric circulation that propagates around the equator at approximately 5 m s–1. Originating in the western Indian Ocean, the MJO strengthens as it moves across the Indian Ocean and continues its eastward propagation over the ITF1. The impacts of the MJO on the intraseasonal variability of the ITF have been well observed2,3,4. Clarifying the feedback of the ITF on MJO propagation is also crucial for accurately simulating the MJO, as air-sea interaction plays a vital role in regulating the MJO5,6,7,8,9.

The ITF, with an annual transport of 10-15 Sv (1 Sv = 106 m3 s–1)10 and heat flux of 0.5–1.0 PW (1 PW = 1015 W)11,12, connects the Pacific Ocean and the Indian Ocean and exerts a significant influence on local and global climate13,14. Previous studies have demonstrated that the ITF has a significant impact on the hydrographic features of the surrounding seawater, as the Pacific and Indonesian sea waters cross the ITF and enter the Indian Ocean thermocline10,15. Therefore, variations in ITF volume transport lead to changes in subsurface temperature, which, in turn, induce significant SST changes in certain regions13,16,17,18. The specific mechanisms and extent to which the ITF influences the eastward propagation of the MJO are still open questions.

Closing the ITF could result in changes in the ocean and atmosphere mean states across the tropical Indo-Pacific region, leading to cooling in the eastern tropical Indian Ocean and a shift of precipitation towards the east over the warm pool region19. The vital role of SST mean state in shaping the MJO’s eastward propagation, by modulating the MJO-related deep convection20 and moisture static energy budget21, has been thoroughly investigated. Simulations consistently indicate that the closure of the ITF can induce SST cooling in the eastern tropical Indian Ocean, thereby weakening the intraseasonal variability of precipitation there16,17,18,22,23,24. This is attributed to the westward moisture static energy gradient, which has been found to impede the eastward propagation of the MJO25,26.

It is also important to investigate the impact of intraseasonal variability of the ITF transport on the eastward propagation of the MJO, as the MJO has the potential to significantly influence the former27,28. Both observations and model results have provided evidence that variations in ITF transport can lead to changes in the intraseasonal variability of SST in the Indo-Pacific region during boreal winter2,29. These intraseasonal SST variations, in turn, should have the potential to alter the magnitude and timing of surface fluxes associated with the MJO8,30,31,32. However, this feedback of intraseasonal variability of ITF transport on the eastward propagation of the MJO has not been investigated.

The extent to which the ITF can impact the eastward propagation of the MJO by altering the mean state and intraseasonal variability remains unclear. To investigate this issue, we conducted one control experiment with an opened ITF (NESM_OITF) and two additional sensitivity experiments, namely NESM_CITF and NESM_OITF_NISV (see Methods). The NESM_CITF experiment focuses on the mean state changes resulting from the closure of the ITF, whereas the NESM_OITF_NISV experiment examines the impact of the intraseasonal variability of ITF transport. Our objective is to quantify the relative contributions of these two processes in modifying the eastward propagation of the MJO.

Results

Observed and simulated influence of ITF transport

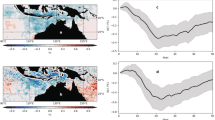

The observed depth-integrated ITF volume transport displays notable variations (Fig. S1A). We categorize the monthly ITF transport into two groups. If the transport anomalies exceed one positive (negative) standard deviation, we designate them as strong (weak) ITF (see Methods). During the boreal winters of 1998-2017, there were 11 MJO events linked with strong ITF and four MJO events associated with weak ITF (Fig. S1A). The composite MJO linked with strong ITF exhibits well-organized eastward propagation (Fig. 1A), while a discontinuity in MJO propagation occurs over the MC for weak ITF (Fig. 1B). The MJO composites for strong and weak ITF resemble the so-called “slow” and “jump” MJO types, respectively33, suggesting that strong ITF transport can bolster the eastward propagation of the boreal-winter MJO, particularly over the MC.

Lead-lag composite of 20–70 day-filtered precipitation anomalies (mm day–1) with respect to (A) 11 and (B) four MJOs associated with strong and weak ITF transports events, respectively, in observations. Day 0 is the central day of the MJO. Bottom panels are the differences of (C) background SST (°C) and (D) intraseasonal SST (°C, 20–70 day-filtered SST) between the MJOs associated with strong and weak ITF events. E–H Same as in (A–D) except for 68 MJOs with strong ITF and 22 MJOs with weak ITF in NESM_OITF. Stippled points represent significant signals at 95% confidence level.

Variations in ITF transport contribute to SST alternation in the Indo-Pacific warm pool region. The composite background SST difference between MJO events correspondingly linked with strong and weak ITF (see “Methods”) indicates warming in the equatorial Indian Ocean, southern MC, and Indonesian seas, alongside cooling in the equatorial Pacific (Fig. 1C). Moreover, intraseasonal SST during MJO events associated with strong ITF events demonstrates enhancement in the southern MC compared to events with weak ITF (Fig. 1D).

The simulation with full ITF coupling, denoted NESM_OITF, successfully replicates the significant variability of ITF transport as shown in the observation (Fig. S1B). We identified 68 MJO events associated with strong ITF and 22 events with weak ITF during the 100 simulated boreal winters. Model results confirm the observation that strong ITF favors MJO events more than weak ITF. The composite of the 68 MJO events associated with strong ITF depicts a continuous eastward propagation of the MJO, albeit at a slower speed than observed (Fig. 1E). However, the composite for weak ITF transport shows a degraded MJO eastward propagation, with its propagation disturbed over the MC (Fig. 1F).

NESM_OITF also demonstrates a remarkable contrast in both mean and intraseasonal SST between MJO events associated with strong and weak ITF (Fig. 1G, H), similar to the observed differences. In comparison to weak ITF, composite of background SST for MJO events linked with strong ITF indicates warming in the southern tropical Indian Ocean, Indonesian seas, northwestern tropical Pacific, and the northeastern region of Australia, as well as cooling in the western tropical Indian Ocean, Bay of Bengal, and the central equatorial Pacific (Fig. 1G), consistent with previous simulations22. Additionally, the simulation with strong ITF also presents enhanced intraseasonal SST in the southeastern tropical Indian Ocean and the southern MC (Fig. 1H).

Due to the barrier effect of the MC, the MJO often weakens, detours, or even dissipates as it propagates eastward over this region34,35. However, the warmer SSTs in the MC increase the temperature gradient between the ocean and the atmosphere, enhancing latent heat release and promoting greater atmospheric instability. This convective instability creates favorable conditions for moisture accumulation and enhances moisture convergence, thereby supporting the maintenance of MJO convection as it moves eastward over the MC, facilitating the completion of a full MJO life cycle.

Both observational and simulation analyses suggest that a strong ITF benefits the maintenance and strengthening of the MJO events and favors the eastward propagation of the MJO over the MC. A strong ITF induces warmer winter SST in the eastern Indian Ocean and enhances the eastward SST gradient (Fig. 1C, G), a factor known to enhance MJO eastward propagation20. Furthermore, a strong ITF markedly intensifies intraseasonal SST in the southern MC during boreal winter (Fig. 1D, H). This indicates that the ITF can influence the mean and intraseasonal SST in the Indo-Pacific region. Therefore, we conducted two additional sensitivity experiments to delve deeper into how the ITF impacts the eastward propagation of the MJO.

Effects of ITF closure and intraseasonal ITF transport

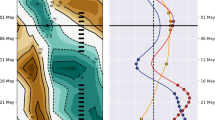

In comparison with observations and NESM_OITF (Fig. 2A, B), the closure of the ITF significantly dampens the eastward propagation of the MJO (Fig. 2C). Based on the continuous eastward propagation of the MJO in observations (Fig. 2A), we computed a metric termed the “MC propagation index” to quantify the MJO’s eastward propagation over the MC (see Methods). This MC propagation index registers at 0.27 in NESM_CITF, much weaker than 0.79 in NESM_OITF (Fig. 2B). Such a result demonstrates that in NESM, the closure of the ITF substantially inhibits the eastward propagation of the MJO by approximately 73% over the MC.

Eastward propagation of MJO precipitation in (A) observation, (B) NESM_OITF, (C) NESM_CITF, and (D) NESM_OITF_NISV during boreal winter. Day 0 is the central day of the MJO. Number in the upper-right corner denotes the MC propagation index calculated in the blue box (105°–150°E, 0–20 day). Stippled points represent significant signals at 95% confidence level. Contours (interval value is 0.1 omitting zero isolines) in (B, C) represent biases. Solid and dashed contours represent positive and negative values, respectively.

With the ITF open, while eliminating intraseasonal ITF transport by nudging the 3-month running-mean ITF transport, NESM_OITF_NISV can simulate the eastward propagation of the MJO, but with weaker propagation over the MC (Fig. 2D). The MC propagation index measures 0.58 in NESM_OITF_NISV. This indicates that the removal of intraseasonal ITF transport leads to a 42% reduction in MJO’s eastward propagation over the MC compared to NESM_OITF.

Impact of ITF closure

It has been firmly established that the ITF closure can cool the tropical Indo-Pacific by modulating Kelvin and Rossby waves36,37,38,39. Blocking the ITF effectively impedes the southward transport of Rossby waves from the equatorial western Pacific to the southeastern Indian Ocean37,40 and also obstructs the leakage of coastal Kelvin waves into the western Pacific through the Lombok Strait41,42,43. Additionally, the ITF closure amplifies sea-level pressure over the western tropical Pacific while decreasing it over the tropical Indian Ocean44. This process stimulates and intensifies the upwelling of Kelvin waves, transporting cold water to the eastern equatorial Indian Ocean16,19.

Experiments with ocean and coupled general circulation models have consistently shown a robust SST response to the closure of the ITF, resulting in a significant reduction in SST in the tropical Indian Ocean16,17,18,22. Similarly, the closure of the ITF in NESM_CITF showcases a notable decrease in winter-mean SST in the equatorial and southern tropical Indian Ocean, as well as the southern MC (Fig. 3A). Consequently, the vertical-integrated specific humidity from the surface to the upper atmosphere exhibits a similar pattern, with significant reductions observed over areas where SST decreases due to the ITF closure (Fig. 3A).

A Mean SST (shading) and vertical-integrated specific humidity (contour; contour interval is 1.0 with zero-isolines omitted) between NESM_CITF and NESM_OITF. B Height-longitude plot of MJO-associated specific humidity; thick blue and yellow contours represent the results in NESM_OITF and NESM_CITF, respectively (starting from 0.0, contour interval is 0.1 (0.5) for value below (above) 0.5 with negative values omitted), shadings represent the difference between NESM_CITF and NESM_OITF. Stippled points in (A) represent significant test of SST difference at 95% confidence level, while in (B) represent the significant test of specific humidity in NESM_OITF at 95% confidence level.

SST variations are commonly understood to modulate low-level convergence and boundary-layer moisture convergence (BLMC)24,45. NESM_OITF accurately reproduces observed features where BLMC, in relation to MJO precipitation, shows zonal asymmetry relative to the MJO convective center (Fig. S4A). The MJO-associated BLMC expands eastward, extending across the northern MC and the western tropical Pacific from the central Indian Ocean. However, without the influence of the ITF, the MJO-associated BLMC is reduced to the east of the MJO convective center (Fig. S4B). Additionally, NESM_CITF shows a discontinuity of BLMC over the MC, inhibiting the vertical moisture convection to the east of the MJO convective center. In line with the MC cooling due to ITF closure, the mean Walker Circulation is also weakened, and its ascending motion over the MC region is suppressed (Fig. S5A, S5B), posing a negative impact on the development of MJO convection there. The propagation of BLMC further illustrates that closing the ITF induces the BLMC propagates westward (Fig. S4D), contrasting with the eastward propagation of BLMC in NESM_OITF (Fig. S4C).

Closing the ITF also diminishes the intraseasonal variability associated with the MJO in the Indo-Pacific region during boreal winter. In comparison to NESM_OITF, NESM_CITF reduces the variability of MJO–scale (20–70-day) precipitation approximately by 16.8% in the Indo-Pacific warm pool region (90°E–180° and 15°S–0°) due to the ITF closure (Fig. S3A). Moreover, there is a reduction of approximately 5.4% in MJO–scale zonal wind at 850 hPa (Fig. S3B) and 11.7% in MJO–scale vertical velocity at 500 hPa (Fig. S3C). Thus, closing the ITF in NESM_CITF fails to generate the asymmetric structures of moisture, especially in the low troposphere, which is a key factor in the MJO’s eastward propagation46,47, compared to NESM_OITF (Fig. 3B). The suppressed deep convection leads to a reduction in low-troposphere moisture to the east of the MJO convective center, which ultimately disrupts the MJO’s eastward propagation. As a result, the resulting SST response to this ITF closure hinders the MJO’s eastward propagation due to air-sea interaction8,24,48. This result demonstrates that in NESM, the ITF closure heavily suppresses the eastward propagation of the MJO by about 73% over the MC. The cold equatorial Indian Ocean is a key factor20.

Feedback of intraseasonal ITF transport

When the intraseasonal variability of ITF transport is removed, NESM_OITF_NISV reduces the intensities of intraseasonal precipitation, zonal wind at 850 hPa, and vertical velocity at 500 hPa by 6.1%, 10.9%, and 6.4% over the southern MC (95°-120°E and 15°-7.5°S), respectively, compared to NESM_OITF (Fig. S3D–S3F). Furthermore, the removal of intraseasonal ITF transport weakens the ascending of the mean Walker Circulation over the MC (Fig. S5C). Consequently, NESM_OITF_NISV exhibits a 42% reduction in the MJO’s eastward propagation over the MC compared to NESM_OITF.

It is intriguing to observe how the intraseasonal ITF transport feedbacks to the MJO propagation by altering SST. When the ITF is fully active, a portion of the warm water, conveyed by the MJO-changed ITF, flows northwestward into the western South China Sea through the Karimata Strait (Fig. 4A). Simultaneously, the remaining warm water is directed toward the coastal areas west of the Java and Sumatra Islands through the Sunda and Lombok Straits. Additionally, warm water from the Banda Sea is transported southward to the southeastern Indian Ocean via the Ombai Strait and the Timor Passage. Eliminating intraseasonal ITF transport leads to a cooling effect on the seawater east of the MJO convective center, particularly in the southeastern Indian Ocean and the coastal region west of the Sumatra and Java Islands (Fig. 4B). Warm seawater in these southeastern Indian Ocean and Sumatra regions has been evidenced to play a vital role in promoting the MJO’s eastward propagation over the MC49. Specifically, the reduction in MJO-associated SST decreases evaporation over the MC region (Fig. S6), which weakens latent heat release into the atmosphere, suppresses convection, and increases atmospheric stability. This creates unfavorable conditions that inhibit the eastward propagation of the MJO over the MC.

MJO-associated seawater temperature (shadings; °C) and ocean currents (vectors; cm s–1) averaged over the upper 20 m during boreal winter for (A) NESM_OITF, (B) differences between NESM_OITF_NISV and NESM_OITF. C, D Same as in (A, B) except for profiles of seawater temperature (shadings; °C) and ocean currents (vectors; cm s–1) along the transection (labeled as the purple lines and solid circles in (A)). Stippled points in (A) and (C) represent significant signals of seawater temperature at 95% confidence level.

The role of intraseasonal ITF transport can be illustrated by analyzing the transection of seawater temperature and ocean currents along a critical path, involving the MJO detouring route around the MC in the Indian Ocean and the ITF pathway (Fig. 4A). With the full operation of the ITF, warm water is transported by the MJO-changed ITF to the southeastern IO and the southwestern coast of Sumatra and Java Islands in the upper ocean (Fig. 4C, E). However, the removal of intraseasonal ITF transport generally results in reduced ocean currents throughout the upper ocean, leading to less transport of warm water to the southeastern Indian Ocean (Fig. 4D) and the southwestern coast of Sumatra and Java Islands (Fig. 4F).

We conducted further statistical analysis to examine the impact of intraseasonal SST variability in the southern MC and ITF outflow regions on the eastward propagation of the MJO. In this regard, we utilized results from NESM_OITF. Initially, we calculated the time series of MJO-scale SST by averaging over the area 105°–130°E and 15°–5°S during boreal winter. Subsequently, we eliminated the signal associated with MJO-scale SST from the 20–70–day filtered precipitation. Following this, we assessed MJO’s eastward propagation using the lead-lag correlation based on the resulting precipitation (refer to Methods). The MC propagation index of the resulting MJO eastward propagation is 0.48, which is smaller than that of NESM_OITF (Fig. S7). Moreover, significant biases are observed in the longitudinal range of the MC when the precipitation associated with the MJO-scale SST variability in the southern MC is removed. These statistical results suggest that intraseasonal SST variability in the southern MC region, induced by intraseasonal ITF transport, plays a role in shaping the MJO’s eastward propagation over the MC.

Discussion

Our observational and modeled results both demonstrate that strong ITF favors the eastward propagation of the MJO, particularly over the MC, during boreal winter. Sensitivity experiments show that the closure of the ITF and the removal of intraseasonal ITF transport will reduce the MJO’s eastward propagation over the MC by 73% and 42%, respectively. The closure of the ITF cools the Indo-Pacific region, reducing the eastward SST gradient over the tropical Indian Ocean, and ultimately weakening the eastward propagation of the MJO. Feedback from the intraseasonal variability of ITF transport also affects the MJO’s propagation, as the MJO easterly wind-enhanced ITF transport warms the tropical Indo-Pacific, promoting the eastward propagation of the MJO.

This finding highlights the importance of accurately simulating the ITF transport in improving the simulation of MJO propagation, especially the feedback from MJO easterly wind-enhanced ITF transport. The intraseasonal variability of ITF is influenced by remote equatorial Indian Ocean wind-forced coastally trapped Kelvin waves, as well as local wind stress over the MC4,28,50. The local wind stress directly impacts the surface layer of the ITF, while the wind forced Kelvin waves affect the ITF transport at subsurface depths of 100–450 m50. Both of them are associated with the propagation of MJO events over the eastern Indian Ocean and the MC.

MJO events crossing the MC tend to occur more frequently during negative Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD) and La Niña years51. The SST gradient and low-level wind anomalies associated with positive IOD inhibit low-level convergence over the eastern Indian Ocean and as result suppresses MJO. In addition, strong ITF transports warm water to the eastern Indian Ocean and deepens the thermocline during La Niña and negative IOD42,52,53. This enables warmer subsurface water under the MJO forcing to maintain high SST that then strengthens eastward propagation of the MJO. The combined influences of the IOD and El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) related ITF variability on MJO propagation over the MC also warrant further investigation.

Methods

Model description and experimental designs

The coupled model used in this study is the Nanjing University of Information Science and Technology Earth System Model version 3.0 (NESM3)54, which includes the atmosphere component ECHAM6.3.0255, ocean component NEMO3.456, and sea-ice component CICE4.157 through the coupler OASIS3-MCT3.058. The standard resolution is utilized in this study. The atmosphere component has T63 resolution with 47 vertical levels, while the ocean component has a horizontal resolution of 1°×1° with the meridional refinement up to 1/3° in the tropical regions and 46 vertical levels. The sea-ice component has a resolution of 1° × 0.5° in the zonal and meridional directions, respectively. Further details of the model can be found in the reference54.

Three sensitivity experiments are conducted. The first involves an opened ITF (referred to as NESM_OITF). The second involves a closed ITF, achieved by creating a land bridge across the Indonesian passages (Fig. S2; referred to as NESM_CITF), following the approach used by previous studies22,23. The third experiment uses the same model configuration as NESM_OITF but involves nudging the monthly three-dimensional ocean currents, which are the 3-month running mean, from NESM_OITF in the Indonesian Seas (20°S-15°N, 100°-160°E) (referred to as NESM_OITF_NISV). This third experiment aims to investigate whether the intraseasonal SST variability induced by the ITF variations influences the MJO eastward propagation.

Observed and modeled data

We utilized daily precipitation data from the Tropical Rainfall Measuring Mission (TRMM) 3B4259 for the period of 1998-2017 to analyze the MJO’s eastward propagation. Daily wind and specific humidity data for the same period as precipitation were obtained from the European Center for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) Interim reanalysis60. Additionally, we used daily Optimum Interpolation sea surface temperature (OISST) version 2 data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration61 to assess the influence of the ITF. To estimate the ITF transport, we utilized monthly ocean current data from the ECMWF ocean reanalysis system 4 (ORAS4)62.

Both NESM_OITF and NESM_CITF were integrated for 500 years using the 1990s forcing. NESM_OITF_NISV, initialized by the 400th-year restart files from NESM_OITF, was run for an additional 100 years. We conducted a comparative analysis using the data from the last 50 years of the three numerical experiments.

In our analysis, the background SST for each MJO event was derived from the 30 days before and after the event’s reference date (day 0). Additionally, we applied a 20–70-day bandpass filter to the SST to obtain the intraseasonal component. This allows us to discuss the intraseasonal SST associated with each MJO event, calculated within ±1 day of the reference date (day 0) when the MJO peak in the Indian Ocean.

ITF transport

The ITF transport is estimated by the depth-integrated meridional ocean current \(v\) along the section at 8.5°S, defined as follows63:

Here, \(H\) is the water depth (with downward as positive), while \({x}_{w}\) and \({x}_{e}\) correspond to the western and eastern boundaries respectively, with values of 115°E and 145°E. Following the removal of the monthly climatology, if the ITF transport exceeds (falls below) one positive (negative) standard deviation, it is categorized as a strong (weak) ITF event.

MJO events associated with the strong and weak ITF events

We initially identify individual MJO event by focusing on the 20–70–day filtered precipitation over the equatorial Indian Ocean (EIO; 80°-100°E, 10°S-10°N) region. Following a similar approach to a previous study33, we consider an MJO event to be presented when area-averaged precipitation anomalies exceed one positive standard deviation for five consecutive days. Furthermore, we select the day when the area-averaged precipitation anomalies reach their maximum as the reference date for a given MJO event (referred to as day 0).

Following these criteria, we subsequently determined the MJO events associated with strong and weak ITF events during boreal winter. An MJO event related to a strong (weak) ITF event is considered only if its reference date falls within the period of strong (weak) ITF events. In the observational data from 1998 to 2017, based on this criterion, we identified 11 MJO events for strong ITF events and 4 MJO events for weak ITF events (Fig. S1A). Meanwhile, in the 100-year results from NESM_OITF, there were 68 MJO events associated with strong ITF events and 22 MJO events related to weak ITF events (Fig. S1B).

Statistical MJO evaluation

To statistically diagnose the MJO, we initially applied a 20–70–day bandpass filter to circulation and thermodynamic fields. We discussed the resulting intraseasonal anomalies during the boreal winter period, spanning from November 1st to April 30th. Evaluation of the MJO’s eastward propagation is conducted using a lead-lag map of anomalous precipitation along the equator relative to precipitation anomalies over the EIO region45,64,65,66. Unless otherwise specified, the regressed maps discussed in this study are obtained against the 20–70–day filtered precipitation area-averaged over the EIO region. To specifically evaluate MJO propagation over the MC, we further calculate a metric termed the “MC propagation index”, similar to a previous study67. This metric involves the summation of positive correlation coefficients over the MC area (105°–150°E) and over the 0–20 lag days normalized by the observed value.

Data availability

The daily TRMM 3B42 data can be accessed at http://apdrc.soest.hawaii.edu. The daily OISST data was obtained from https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/data/sea-surface-temperature-optimum-interpolation/v2.1. The daily ERA-Interim data is available at http://apdrc.soest.hawaii.edu. The data used to plot figures in this study can be downloaded from https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.25513993.

Code availability

The scripts used to create Figures in this study were written in NCAR Command Language (NCL; http://www.ncl.ucar.edu/) and are available on https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.25513993.

References

Madden, R. & Julian, P. Description of global scale circulation cells in the tropics with a 40-50 day period. J. Atmos. Sci. 29, 1109–1123 (1972).

Qiu, B., Mao, M. & Kashino, Y. Intraseasonal variability in the Indo-Pacific throughflow and the regions surrounding the Indonesian seas. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 29, 1599–1618 (1999).

Pujiana, K., Gordon, A. L. & Sprintall, J. Intraseasonal Kelvin wave in Makassar Strait. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 118, 2023–2034 (2013).

Tamasiunas, M. C. N., Shinoda, T., Susanto, R. D., Zamudio, L. & Metzger, E. J. Intraseasonal variability of the Indonesian throughflow associated with the Madden-Julian Oscillation. Deep-Sea Res. II 193, 10495 (2021).

Fu, X. H., Wang, B., Waliser, D. E. & Li, T. Impact of atmosphere-ocean coupling on the predictability of monsoon intraseasonal oscillations. J. Atmos. Sci. 64, 157–174 (2007).

Woolnough, S. J., Vitart, F. & Balmaseda, M. A. The role of the ocean in the Madden-Julian oscillation: Implications for MJO prediction. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 133, 117–128 (2007).

Seo, H., Subramanian, A. C., Miller, A. J. & Cavanaugh, N. R. Coupled impacts of the diurnal cycle of sea surface temperature on the Madden-Julian oscillation. J. Clim. 27, 8422–8443 (2014).

DeMott, C. A., Klingaman, N. P. & Woolnough, S. J. Atmosphere-ocean coupled processes in the Madden-Julian oscillation. Rev. Geophys. 53, 1099–1154 (2015).

Ma, L. B. & Jiang, Z. J. Reevaluating the impacts of oceanic vertical resolution on the simulation of Madden-Julian Oscillation eastward propagation. Clim. Dyn. 56, 2259–2278 (2021).

Gordon, A. L. Oceanography of the indonesian seas and their throughflow. Oceanogr 18, 14–27 (2005).

Gordon, A. L. Interocean Exchange. In: Ocean circulation and climate. In: International Geophysics Series, Academic Press 77, pp. 303-314 (2001).

Vranes, K., Gordon, A. L., & Ffield, A. The heat transport of the Indonesian throughflow and implications for the Indian Ocean Heat Budget. In: Physical Oceanography of the Indian Ocean during the WOCE period, F. Schott, ed. Deep-Sea Res. 49, 1391–1410 (2002).

Sprintall, J. & Révelard, A. The Indonesian Throughflow response to Indo-Pacifc climate variability. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 119, 1161–1175 (2014).

Li, M., Cao, Z., Gordon, A. L., Zheng, F. & Wang, D. Roles of the Indo-Pacific subsurface Kelvin waves and volume transport in prolonging the triple-dip 2020–2023 La Niña. Environ. Res. Lett. 18, 104043 (2023).

Hu, S. et al. Interannual to decadal variability of upper-ocean salinity in the southern indian ocean and the role of the Indonesian throughflow. J. Clim. 32, 6403–6421 (2019).

Hirst, A. C. & Godfrey, J. S. The role of Indonesian throughflow in a global ocean GCM. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 23, 1057–1086 (1993).

Hirst, A. C. & Godfrey, J. S. The response to a sudden change in Indonesian throughflow in a global ocean GCM. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 24, 1895–1910 (1994).

Wajsowicz, R. C. & Schneider, E. K. The Indonesian throughflow’s effect on global climate determined from the COLA coupled climate system. J. Clim. 14, 3029–3042 (2001).

Song, Q., Vecchi, G. A. & Rosati, A. J. The role of the Indonesian throughflow in the Indo-Pacific climate variability in the GFDL coupled climate model. J. Clim. 20, 2434–2451 (2007).

Arnold, N. P., Kuang, Z. M. & Tziperman, E. Enhanced MJO-like variability at high SST. J. Clim. 26, 988–1001 (2013).

Shamekh, S., Muller, C., Duvei, J.-P. & D’Andrea, F. How do ocean warm anomalies favor the aggregation of deep convective cloud? J. Atmos. Sci. 77, 3733–3745 (2020).

Santoso, A., Cai, W. J., England, M. H. & Phipps, S. J. The role of the Indonesian throughflow on ENSO dynamics in a coupled climate model. J. Clim. 24, 585–601 (2011).

Kajtar, J. B., Santoso, A., England, M. H. & Cai, W. J. Indo-pacific climate interactions in the absence of an indonesian throughflow. J. Clim. 28, 5017–5029 (2015).

Tseng, W.-L. et al. Resolving the upper-ocean warm layer improves the simulation of the Madden-Julian oscillation. Clim. Dyn. 44, 1487–1503 (2015).

Gonzales, A. O. & Jiang, X. Winter mean lower-tropospheric moisture over the MC as a climate model diagnostic metric for the propagating of the Madden-Julian oscillation. Geophys. Res. Lett. 44, 2588–2596 (2017).

DeMott, C. A., Wolding, B. O., Maloney, E. D. & Randall, D. A. Atmospheric mechanisms for MJO decay over the MC. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 123, 5188–5024 (2018).

Napitu, A. M., Gordon, A. L. & Pujiana, K. Intraseasonal sea surface temperature variability across the Indonesian seas. J. Clim. 28, 8710–8727 (2015).

Napitu, A. M., Pujiana, K. & Gordon, A. L. The Madden-Julian oscillation’s impact on the Makassar Strait surface layer transport. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 124, 3538–3550 (2019).

Napita, A. M. Response of the Indonesian Seas and its potential feedback to the Madden-Julian oscillation. PhD dissertation, Dept. of Earth & Environmental Science, Columbia University, https://doi.org/10.7916/D8086HSK (2017).

Shinoda, T., Hendon, H. H. & Glick, J. Intraseasonal variability of surface fluxes and sea surface temperature in the tropical western Pacific and Indian Oceans. J. Clim. 11, 1685–1702 (1998).

Wang, B. & Xie, X. Coupled modes of the warm pool climate system. Part I: The role of air-sea interaction in maintain Madden-Julian oscillation. J. Clim. 8, 2116–2135 (1998).

Liu, F. & Wang, B. An air-sea coupled skeleton model for the Madden-Julian oscillation. J. Atmos. Sci. 70, 3147–3156 (2013).

Wang, B., Chen, G. S. & Liu, F. Diversity of the Madden-Julian oscillation. Sci. Adv. 5, eaax0220 (2019).

Kim, D., Kug, J. S. & Sobel, A. H. Propagation versus nonpropagation Madden-Julian Oscillation events. J. Clim. 27, 111–125 (2014).

Li, K. P. et al. Spring barrier to the MJO eastward propagation. Geophys. Res. Lett. 46, e2020GL087788 (2020).

Godfrey, J. S. The effect of the Indonesian throughflow on ocean circulation and heat exchange with the atmosphere: A review. J. Geophys. Res. 101, 12217–12237 (1996).

Wijffels, S. & Meyers, G. An intersection of oceanic waveguides: Variability in the Indonesian throughflow region. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 34, 1232–1253 (2004).

McCreary, J. P. et al. Interactions between the Indonesian throughflow and circulations in the Indian and Pacific Oceans. Prog. Oceanogr. 75, 70–114 (2007).

Sprintall, J. et al. Detecting change in the Indonesian seas. Front. Mar. Sci. 6, 257 (2019).

Susanto, R. D., Gordon, A. L., Sprintall, J. & Herunadi, B. Intraseasonal variability and tides in Makassar Strait. Geophys. Res. Lett. 27, 1499–1502 (2000).

Sprintall, J., Gordon, A. L., Murtugudde, R. & Susanto, R. D. A semiannual Indian Ocean forced Kelvin wave observed in the Indonesian seas in May 1997. J. Geophys. Res. 105, 17217–17230 (2000).

Yuan, D., Zhou, H. & Zhao, X. Interannual climate variability over the tropical Pacific Ocean induced by the Indian Ocean Dipole through the Indonesian Throughflow. J. Clim. 26, 2845–2861 (2013).

Wang, J., Yuan, D. L. & Zhao, X. Impacts of Indonesian throughflow on seasonal circulation in the equatorial Indian Ocean. Chin. J. Oceanol. Limnol. 35, 1261–1274 (2017).

Schneider, N. The Indonesian throughflow and the global climate system. J. Clim. 11, 676–689 (1998).

Wang, B. et al. Dynamics-oriented diagnostics for the Madden-Julian oscillation. J. Clim. 31, 3117–3135 (2018).

Hsu, P.-C. & Li, T. Role of boundary layer moisture asymmetry in causing the eastward propagation of the Madden-Julian oscillation. J. Clim. 25, 4914–4931 (2012).

Hsu, P.-C., Li, T. & Murakami, H. Moisture asymmetry and MJO eastward propagation in an aquaplanet general circulation model. J. Clim. 27, 8748–8760 (2014).

DeMott, C. A., et al. The convection connection: How ocean feedbacks affect tropical mean moisture and MJO propagation. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 124, https://doi.org/10.1029/2019JD031015 (2019).

Zhou, L. & Murtugudde, R. Oceanic impacts on MJOs detouring near the MC. J. Clim. 33, 2371–2388 (2020).

Pujiana, K., Gordon, A. L., Metzger, E. J. & Ffield, A. L. The Makassar Strait pycnocline variability at 20-40 days. Dyn. Atmos. Oceans 53, 17–35 (2012).

Wilson, E. A., Gordon, A. L. & Kim, D. Observations of the Madden Julian oscillation during indian ocean dipole events. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 118, 2588–2599 (2013).

Yuan, D. et al. Forcing of the Indian Ocean Dipole on the interannual variations of the tropical Pacific Ocean: roles of the Indonesian Throughflow. J. Clim. 24, 3593–3608 (2011).

Gordon, A. L. et al. Makassar strait throughflow seasonal and interannual variability: An overview. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 124, 1–13 (2019).

Cao, J. et al. The NUIST Earth System Model (NESM) version 3: Description and preliminary evaluation. Geosci. Model. Dev. 11, 2975–2993 (2018).

Stevens, B. et al. Atmospheric component of the MPI-M earth system model: ECHAM6. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 5, 146–172 (2013).

Madec, G. NEMO ocean engine. IPSL Tech. Note, p 332 (2008).

Hunke, E. C. & Lipscomb, W. H. CICE: the Los Alamos Sea Ice Model documentation and software user’s manual version 4.1. LA-CC-06-012 p 76 (2010).

Valcke, S. & Coquart, L. OASIS-MCT user guide: OASIS-MCT 3.0. CERFACS TR/CMGC/15/38, p 58 (2015).

Huffman, G. J. et al. The TRMM multi-satellite precipitation analysis: Quasi-global, multi-year, combined-sensor precipitation estimates at fine scale. J. Hydrometeorol. 8, 38–55 (2007).

Dee, D. P. et al. The ERA-Interim reanalysis: Configuration and performance of the data assimilation system. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 137, 553–597 (2001).

Huang, B. et al. Improvements of the daily optimal interpolation sea surface temperature (DOISST) version 2.1. J. Clim. 34, 2923–2939 (2021).

Balmaseda, M. A., Mogensen, K. & Weaver, A. T. Evaluation of the ECMWF ocean reanalysis system ORAS4. Q. J. R. Meteor. Soc. 139, 1132–1161 (2013).

England, M. H. & Huang, F. On the interannual variability of the Indonesian throughflow and its linkage with ENSO. J. Clim. 18, 1435–1444 (2005).

Jiang, X. A. et al. Vertical structure and physical processes of the Madden-Julian oscillation: Exploring key model physics in climate simulations. J. Geophys. Res. 120, 4718–4748 (2015).

Ma, L. B., Perters, K., Wang, B. & Li, J. Revisiting the impact of stochastic multicloud model on the MJO using low-resolution ECHAM6.3 atmosphere model. J. Meteorol. Soc. Jpn. 97, 977–993 (2019).

Li, J., Yang, Y. & Zhu, Z. W. Application of MJO dynamics-oriented diagnostics to CMIP5 Models. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 141, 673–684 (2020).

Ahn, M.-S. et al. MJO propagation across the MC: Are CMIP6 models better than CMIP5 models? Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e2020GL087250 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2022YFC3004203 and 2021YFC3000805), the Guangdong Major Project of Basic and Applied Basic Research (2020B0301030004), the National Science Foundation of China (42175061 and 42276005), and the S&T Development Fund of the Chinese Academy of Meteorological Sciences (2024KJ013).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.M. and F.L. conceptualized and led the work. L.M. and L.F. contributed to data analysis including validation and interpretation of the results. L.M., F.L., and M.L. wrote the manuscript, and all authors reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ma, L., Li, M., Liu, F. et al. Indonesian Throughflow promoted eastward propagation of the Madden-Julian Oscillation. npj Clim Atmos Sci 7, 247 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-024-00787-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-024-00787-y