Abstract

This study investigates global extreme precipitation events (EPEs) during warm seasons, with a particular focus on EPEs preceded by extreme heat stress (EPE-Hs) and a comparative analysis with those not (EPE-NHs). Using reanalysis product and Earth System Model data, the spatiotemporal characteristics and temperature sensitivities of EPEs are analyzed. Results show that EPE-Hs, while less frequent, have longer duration and greater magnitude compared to EPE-NHs, particularly in high latitude regions. In the future, a significant increase is projected in the characteristics of EPE-Hs, in contrast to the stable duration and magnitude of EPE-NHs. EPE-Hs demonstrate substantially higher temperature sensitivity than EPE-NHs, especially in low latitudes. The precipitation-temperature scaling relationships diverge markedly between EPE-Hs and EPE-NHs, with notable regional variations. These insights are pivotal for crafting region-specific early warning and adaptation strategies to mitigate the risks associated with extreme precipitation under the backdrop of global warming.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Extreme precipitation events (EPEs), one of the most destructive natural disasters, pose significant threats to the human society, economy, and environment worldwide1,2,3. The World Meteorological Organization reports that, from 1970 to 2021, heavy precipitation-flood related disasters were the most prevalent and contributed the most to economic losses among weather-related disasters4. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Sixth Assessment Report notes that over 700 million people are experiencing significantly more intense EPEs than in the 1950s5. Recently, there has been a growing focus on understanding the complex interplay between climate extremes, particularly those involving both heat and precipitation6,7,8,9. Compound heat stress and heavy precipitation events (CHPEs), characterized by extreme precipitation tightly preceded by heat stress, are among the most common and impactful compound extremes10,11. Accumulating evidence indicates that CHPEs have caused even more huge damage to life and the economy than single EPEs12,13. This underscores the importance of examining not only the occurrence of EPEs but also the specific conditions, such as preceding heat stress, that may exacerbate their effects. Research efforts have been devoted towards the occurrence and characterization of CHPEs at global14,15 and regional scales16,17,18,19. However, comparative studies on EPEs in CHPEs (i.e., EPEs with preceding heat stress, EPE-Hs) versus other single EPEs (i.e., EPEs without preceding heat stress, EPE-NHs) are not found. Understanding such differences is crucial for climate change adaptation strategies in regions where a significant portion of extreme precipitation is preceded by heat stress events.

Global warming has altered the intrinsic variability of climate variables, leading to significant changes in the frequency, intensity and impact range of extreme precipitation at regional and global scales20,21,22. Most regions are projected to suffer from an increase in heavy precipitation and pluvial flood with high confidence23. Earth System Models (ESMs) from the newest Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6), which employ the new combined Shared Socioeconomic Pathway (SSP)—Representative Concentration Pathway (RCP) based emission scenarios, have been regarded as a valuable tool to project the future climate conditions under different developing pathways24,25,26. Using the CMIP6 multi-model ensemble (MME), previous studies have investigated future changes in EPEs across various regions and timescales27,28,29,30. For instance, Feng et al. 31 employed 23 CMIP6 ESMs and reported significant increases in future extreme precipitation globally, particularly under high greenhouse gas emission scenarios. Recent studies show that the frequency of CHPEs has increased since the 1960s and is projected to continue increasing under high emission scenarios12,14,15. These findings underscore the importance of understanding future spatiotemporal variations of EPEs under various scenarios.

The increase in extreme precipitation worldwide is associated with an increased temperature32,33. According to the Clausius–Clapeyron (C–C) relation, the atmospheric moisture holding capacity should increase with warming temperatures at a rate of ~7%/°C, and thereby fueling comparable rises in EPEs driven by moisture convergence34,35,36,37. Much literature have explored the precipitation-temperature (P–T) scaling relationships considering various regions, time scales, and rainfall types38,39,40. Observations and ESM simulations report diverse scaling rates, from strong super C–C scaling in mid-latitude and dry regions to weak sub-C–C or negative rates in the tropics and wet regions41,42. For example, Yin et al. 42 observed a P–T hook structure across global mid-latitudes during 1979–2017, whereby extreme precipitation increases with temperature up to a threshold point, and then decreases as temperature increases above that. Furthermore, the future scaling rate may increase under global warming with regional disparities43,44. By employing a high-resolution ESM, Varghese et al.45 checked the relationships between extreme precipitation and temperature for both present-day and future RCP8.5 scenario in India, and reported that variation of P–T hook structure is sharper in future scenario, along with an increase in the peak intensity of extreme precipitation. Besides regional discrepancies, different types of EPEs can result in different P–T relationships. A recent study found that the extreme P–T scaling rates for atmospheric river-induced precipitation are markedly higher than those for non-atmospheric river-induced events in California46. Given the complexity of these P–T relationships and their significant implications for climate change adaptation, understanding the differences between EPE-Hs and EPE-NHs in response to temperature changes is of paramount importance.

In this study, we aim to investigate the spatiotemporal variations in global extreme precipitation based on the reanalysis data and the latest ESMs from CMIP6, focusing on the differences in EPE-Hs and EPE-NHs. We consider only the local hottest five months, as EPE–Hs predominantly occur in the summer season. Both the reanalysis dataset and model simulations from six CMIP6 ESMs are utilized. We first check the observed differences in the characteristics of EPE-Hs and EPE-NHs. Then we project the future variations in EPE-Hs and EPE-NHs under four combined SSP–RCP scenarios from CMIP6. We further disentangle the sensitivity of extreme precipitation to global warming. Finally the global and regional P–T relationship of EPE-Hs and EPE-NHs are explored. Our objectives are to address: (1) Where and how do the spatiotemporal variations in extreme precipitation differ between the EPE-Hs and EPE-NHs in both the historical and future periods? (2) How do these EPEs respond to temperature under various future scenarios, respectively?

Results

Observed differences in EPE characteristics

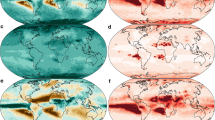

We first identify global EPEs using reanalysis product during the warm season (Supplementary Fig. 1) for the historical period (1979–2014). The 90th percentile of the historical warm season is used as the threshold for identifying single extreme events. The 3-day time interval between the preceding heat stress event and following EPE is used to identify EPE-Hs and EPE-NHs (see “Methods”). Fig. 1 displays the variations in the spatiotemporal characteristics of the identified EPEs. In the historical period, the global averaged frequency of EPE-Hs is observed significantly lower than that of EPE-NHs (Fig. 1b). However, EPE-Hs show greater magnitude and longer duration than EPE-NHs on a global average (Fig. 1c, d). Specifically, EPE-NHs occur more frequently in the southeast Asia, Amazon, northeastern America, and northeastern Asia. EPE-Hs are more frequent in the region north of 45°N latitude, central United States, and the southern Tibetan Plateau (Fig. 1a). Due to the low occurrence of EPE-Hs worldwide, the multiyear averaged duration and magnitude of all EPEs and EPE-NHs exhibit similar spatial distribution (Fig. 1a). EPEs with relative long duration occur in the western United States, northeastern Brazil, southern Africa, southern Asia, and Australia. The difference between the durations of EPE-Hs and EPE-NHs are mainly observed in the high latitudes in Northern Hemisphere, Tibetan Plateau, and southern Australia, where EPE-Hs present longer duration than EPE-NHs. Similarly, the magnitude of EPE-Hs are notably larger than that of EPE-NHs in high latitudes, especially in northern Asia above 45°N latitude. High-magnitude EPE-NHs are found in central North America, northeastern Brazil, southern Argentina, the Middle East, northwestern India, southern Africa, and southern Australia.

a Spatial distribution of multi-year averaged characteristics of all EPEs (the first row), EPE-Hs (the second row), and EPE-NHs (the third row) during 1979–2014. The first column is frequency (times), the second column is duration (days), and the third column is magnitude. b–d Temporal changes in global area-weighted averaged EPE characteristics. The dotted lines indicate a linear fit. The symbol * indicates significant trend at 0.05 significance level. e 22 climate regions in global landmass. f Heat maps of linear fitting trend in EPE characteristics for the 22 regions and the global landmass. ALA Alaska, GRL Greenland and Northern Territories, WNA Western North America, CNA Central North America, ENA Eastern North America, CAM Central America, AMZ Amazon Basin, NEB Northeastern Brazil, SSA Southern South America, NEU Northern Europe, NAS North Asia, MED Mediterranean Basin, CAS Central Asia, TIB Tibet, EAS East Asia, SAS South Asia, SEA Southeast Asia, WAF Western Africa, EAF Eastern Africa, SAF Southern Africa, NAU North Australia, SAU South Australia, GB Global landmass.

The trends depicted in the time series of global average EPE characteristics (Fig. 1b–d) are estimated by the simple linear regression based on the least squares method12, and the significance is assessed using the nonparametric Mann-Kendall trend test at the 0.05 significance level47. The increase in the global average frequency of EPEs consists mainly of the increase in EPE-Hs, which are accompanied by preceding heat stress (Fig. 1b). We also investigate the temporal variations in the regional average EPE characteristics for the 22 climate regions (Fig. 1e). The frequency of EPE-Hs show increasing trends in all 22 regions, most of which are significant. While the EPE-NHs are becoming less frequent in WNA, AMZ, WAF, and EAF. Comparing to the EPE-NHs, the frequency trends of EPE-NHs are larger in most regions except in NAS, TIB, SAS, SEA, NAU, and SAU. There is no discernible trend in the global average duration of EPEs during the historical period, nor in the majority of the regions examined. However, a significant increase in the duration of EPE-Hs is observed in ALA, CAM, SAF, and NAU and a significant decreases is noted in WAF. As for EPE-NHs, a significant increase in duration is seen in SAF, while a significant decrease is observed in EAF. The global average magnitude of EPEs exhibit slight increase from 1979 to 2014. Regionally, the magnitude of EPE-Hs increases significantly in ALA, GRL, NEB, NAS, MED, EAF, and NAU, while decreasing in CAM, TIB, and SAS. For the magnitude of EPE-NHs, significant increase is found in ALA, CAM, NEB, SSA, and EAF. We also use the 95th threshold to identify single EPEs and use 1-day and 7-day time interval to identify EPE-Hs and EPE-NHs (Supplementary Figs. 2–4). The conclusion that the EPE-Hs are less frequent but more intense than EPE-NHs, especially in high latitudes of the Northern Hemisphere, is robust. Collectively, our analysis reveals the divergent spatiotemporal patterns of EPE-NHs and EPE-Hs. The increasing prevalence and intensity of EPE-Hs, especially in high latitude regions, signal a need for heightened awareness and adaptive measures to address the evolving impacts of climate change on precipitation patterns.

Projected spatiotemporal variations of EPE characteristics

We employ the MME of six CMIP6 ESMs to explore the future spatiotemporal variations in the characteristics of EPEs. The EPEs in the ESMs are identified using the same threshold as in the observation. Fig. 2 and Supplementary Figs. 5–7 display the temporal variations of the global average characteristics of all EPEs, EPE-Hs, and EPE-NHs for the baseline (1979–2014) and future (2015–2100) periods. The terminal years of the baseline and future period, 2014 and 2100, respectively, are excluded because the warm season in the Southern Hemisphere extends into the subsequent year. On a global average, all EPEs show a slightly increasing trend in frequency, duration, and magnitude for the whole 1979–2099 period. Interestingly, the global average characteristics of EPE-Hs and EPE-NHs show significantly distinct trends. Specifically, the global average frequency of EPE-Hs exhibits a notable uptick from the baseline period to the 2060s, whereas the frequency of EPE-NHs continues to decline. The duration of EPE-Hs demonstrates a substantial and sustained increase in the future period, while the duration of EPE-NHs remains relatively unchanged. Regarding magnitude, EPE-Hs initially experience a modest increase, followed by a significant surge post-2050 under high emission scenarios (i.e., SSP3-7.0 and SSP5-8.5), while the magnitude of EPE-NHs maintains relatively stable throughout the study period. Comparing different SSP–RCP scenarios, the frequency and duration of all EPEs show minor variations among four scenarios, with higher values projected under higher emission scenarios by the late 2100 s (Fig. 2a, b). The magnitude of all EPEs varies significantly across the four scenarios in the second half century (Fig. 2c). For EPE-Hs, the variations among different scenarios are more remarkable for frequency and magnitude than duration, with higher values under higher emission scenarios (Fig. 2d–f). These distinctions become noticeable after 2050. For EPE-NHs, there are minimal differences in duration and magnitude among different scenarios. However, as opposed to EPEs, higher values of EPE-NH frequency are projected under lower emission scenarios (Fig. 2g–i).

To clarify the spatial variation of EPE characteristics during different time periods, we divided the future period into three sub-periods, i.e., near term (2015–2040), midterm (2041–2070), and long term (2071–2099). The spatial patterns of projected EPE characteristics for the three sub-periods relative to the baseline period are shown in Fig. 3 and Supplementary Figs. 8–30. Taking the magnitude change in the long-term future as an example (Fig. 3), the magnitude of all EPEs are larger in the long-term than the baseline period in most parts of the world except the Mediterranean region and southern Australia under SSP1-2.6. The largest increase is predicted in Tibetan plateau, northwestern North America, western South America, and eastern Africa under SSP5-8.5. The increase in magnitude of EPE-Hs is larger than that of EPE-NHs worldwide, and is more significant in the northwestern North America, northern South America, eastern and western Africa, Tibetan plateau, northeastern Asia, southeastern China, and southeastern Asia. For the EPE-NHs, decreases in magnitude are found in Mexico, southern Brazil, central and south Africa, central Asia, Pakistan, and Australia. There are high model agreements in regions where a significant increase or decrease is projected in EPE magnitude (Supplementary Fig. 8). Comparing the four scenarios, the changes under higher emission scenarios are larger than that under lower emission scenarios, which is consistent with Fig. 2. Differences among scenarios are more pronounced in the long-term and mid-term than the near-term future. Specific information of future changes in EPE characteristics for the 22 climate regions under four scenarios are provided in Supplementary Text 1 and Supplementary Figs. 31–33.

Sensitivity of extreme precipitation to temperature

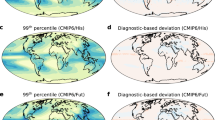

Increased precipitation worldwide is associated with global warming through thermodynamic and dynamical processes with regional variations23. To identify where and how strongly climate warming impacts the extreme precipitation, we checked the temperature sensitivity of precipitation in EPEs for each grid-point under different SSP–RCP scenarios. The temperature sensitivity of extreme precipitation is defined as the linear change in extreme precipitation with global surface air temperature (GSAT)41. This metric is quantified by dividing the relative change in the total amount of precipitation in EPEs (unit: %) by the change in GSAT (unit: °C) from the baseline period to future terms. Fig. 4 and Supplementary Figs. 34–45 depict the temperature sensitivity of all EPEs, EPE-Hs, and EPE-NHs for the near-term, mid-term, and long-term future. EPE-Hs exhibit a significantly higher temperature sensitivity compared to all EPEs and EPE-NHs under all scenarios (Fig. 4g–i). The global average temperature sensitivity of EPE-Hs (ηH) reaches over 200%/°C, implying a intense growth in the total amount of extreme precipitation following heat stress under global warming. From the near-term to the long-term, the global average temperature sensitivity of all EPEs (ηE) decreases, suggesting that the impact of global warming on EPEs may be more pronounced in the coming decades than the long-term future. However, the global average ηH is the highest in the mid-term, while the global average temperature sensitivity of EPE-Hs (ηN) is the lowest. The distinction among different scenarios intensifies from the near-term to the long-term. In the last 30 years of this century, ηN values are lower while ηH values are higher under scenarios with reduced emissions.

Spatial distribution of the temperature sensitivity under SSP5-8.5 in the long-term future for (a) all EPEs, (b) EPE-Hs, (c) EPE-NHs. d–f latitude average of (a–c). Global average temperature sensitivity of (g) all EPEs, (h) EPE-Hs, (i) EPE-NHs. The temperature sensitivity is the ratio of the relative change in the total amount of precipitation in EPEs (%) to the change in global surface air temperature (°C), where both changes are from the baseline to the future period.

The spatial distribution patterns of temperature sensitivity are generally consistent across all four scenarios (Supplementary Figs. 34–45). For all EPEs, positive ηE is evident across most global land areas, with the most substantial values noted in western India, western China, Southeast Asia, northeastern Asia, northern North America, and in northern, eastern, and western Africa, as well as along the northwestern coastline of South America. Negative ηE is projected in central America, northeastern South America, the Mediterranean, southern Africa, and southeastern Australia. Regions of significant ηH (>200%/°C) are projected in South China, Southeast Asia, northern and central Africa, western and southern North America, and northeastern South America. In contrast, ηN values are predominantly negative (<−10%/°C) in mid-latitude regions, particularly in Australia, southern Africa, eastern South America, the Mediterranean, and southern North America. Positive ηN values are predominantly found in the Southeast Asia, eastern Africa, the northwestern coastline of South America, and regions north of 60°N. On latitude average (Fig. 4d–f), ηH values are significantly higher in the low latitudes, specifically between 20°N and 20°S. Shifting focus to the high latitudes above 60°N, both ηE values and ηN values demonstrate relative substantial, implying that EPE-NHs in the high latitudes are particularly sensitive to temperature changes. Our analysis shows that EPE-Hs have a significantly higher temperature sensitivity than EPE-NHs, with EPE-Hs being more sensitive in low-latitude areas and EPE-NHs in areas north of 60°N. This insight suggests that climate adaptation strategies should consider the varying responses to warming across different types of EPEs.

We then compare the temperature sensitivity of EPEs among the four scenarios for the 22 climate regions (Fig. 5). For all EPEs, the temperature sensitivity is found to be more pronounced under low emission scenarios (i.e., SSP1-2.6 and SSP2-4.5) than high emission scenarios (i.e., SSP3-7.0 and SSP5-8.5) for most regions, aligning with the global average. However, for SSA, WAF, EAF, SAF, and NAU, the sensitivity is notably higher under high emission scenarios, indicating that these areas may experience a more significant increase in EPEs under greater greenhouse gas emissions. Comparing ηH and ηN across different scenarios, the 22 climate regions can be categorized into two groups. For regions with high ηH including ENA, CAM, AMZ, NEB, EAS, SEA, WAF, EAF, SAF, and NAU, ηH increases to mid-term and then declines under high emission scenarios, while ηN decreases first and then increases. In these regions, ηH are notably higher under lower emission scenarios in the long term, while ηN are higher under higher emission scenarios. In contrast, in other regions, ηH continues to increase from the near term to the long term under high emission scenarios, where ηN continues to decrease. The ηH are higher under SSP3-7.0 and SSP5-8.5 in these regions while ηN are higher under SSP1-2.6 and SSP2-4.5. These findings indicate that the response of extreme precipitation to global warming vary considerably across different regions.

a temperature sensitivity of all EPEs, b temperature sensitivity of EPE-Hs, c temperature sensitivity of EPE-NHs. Near near-term future, Mid mid-term future, Long long-term future. S1 SSP1-2.6, S2 SSP2-4.5, S3 SSP3-7.0, S5 SSP5-8.5. The symbol * indicates low model agreement (<80%) on projected change signals.

Global and regional precipitation scaling structure

To gain further insight into the response of extreme precipitation in EPEs to temperature, we examine the P–T scaling structure of EPEs across both baseline and future periods. Fig. 6 illustrates the scaling structure of global average EPEs with GSAT, where the y-axis is the logarithm of global averaged annual extreme precipitation. Notably, the scaling curves for all EPEs, EPE-Hs, and EPE-NHs are significantly different (Fig. 6 and Supplementary Figs. 46–48). The scaling curves of the baseline period and the future four emission scenarios show consistency (Fig. 6f), with the temperature scale expanding from low to high emission scenarios. The behavior of global average EPEs in response to GSAT is categorized into three distinct types: a monotonic linear increase with GSAT, an initial increase to a peak at a certain threshold temperature (peak point temperature, Tp) followed by a decrease, and a decrease followed by an increase after reaching Tp. Globally, the P–T relationship of all EPEs is characterized by the first module, with a scaling rate of 9.07%/°C. For EPE-Hs, the P–T relationship follows the second module, peaking at a Tp of 17.19 °C. In contrast to EPE-Hs, EPE-NHs first diminish with rising GSAT and subsequently amplify, exemplifying the third module. In summary, our study reveals that the response of EPEs to climate warming exhibits significant divergence with and without preceding heat stress. These nuanced dynamics underscore the complexity of the relationship between climate change and EPEs.

a Baseline period. b–f Future period. b SSP1-2.6. c SSP2-4.5. d SSP3-7.0. e SSP5-8.5. f Combination of a-e. The y-axis is the logarithmic coordinate. The solid lines show the respective non-parametric fitting using LOWESS smoothing method. Gray dotted lines illustrate the C–C scaling (7%/°C) for reference. Tp, the peak point temperature. Pp, the precipitation at Tp.

We further explore the P–T relationship between regional EPEs and regional surface air temperature (RSAT, Fig. 7) for the 22 climate regions. For regions except MED and CAM, the annual amount of all EPEs exhibits a monotonic increase with RSAT, following a super C–C scaling rate in ALA, SSA, TIB, EAS, SAS, SEA, and EAF and a sub C–C scaling rate in other regions. The scaling behavior of EPE-Hs across the 22 regions can be broadly categorized into two distinct patterns. For low latitude regions including CAM, AMZ, NEB, SEA, WAF, EAF, SAF, and NAU, the scaling curve of EPE-Hs mirrors that of the global landmass, Here, the precipitation intensity increases with RSAT at a super C–C scaling rate first, reaching Tp beyond which it declines. Among these regions, Tp are the highest in WAF (30.38 °C) and the lowest in SAF (25.18 °C). The annual EPE-Hs at Tp (Pp) are the largest in SEA (270 mm) and the smallest in EAF (105 mm). In contrast, for the remaining regions, the precipitation intensity of EPE-Hs continues to rise throughout the study period with RSAT. For EPE-NHs, corresponding to the two groups in EPE-Hs, the annual extreme precipitation initially decreases and then ascends with RSAT for the aforementioned low latitude regions. In other regions, however, the annual EPE-NHs keeps a monotonic decrease, reflecting a different dynamic in response to temperature anomalies. Comparing the annual amount of extreme precipitation, EPE-Hs are projected to exceed EPE-NHs in ENA, CAM, SSA, TIB, EAS, SEA, EAF, SAF, NAU, and SAU, while remaining smaller than EPE-NHs in other regions. Furthermore, we find that the Tp increase with the extremity of EPEs and with time proximity of the preceding heat stress to the EPE-Hs (Supplementary Figs. 46–48). These regional disparities in the P–T relationship of EPE-Hs and EPE-NHs, especially between low and high latitudes, underscore the heterogeneity of climate responses to global warming and emphasize the importance of region-specific climate models and adaptation strategies.

The solid lines for each region is the same as Fig. 6f, which contains the baseline period and future period under four SSP–RCP scenarios. Tp, the peak point temperature. Pp, the annual amount of extreme precipitation at Tp.

Discussion

In this study, we first investigate the difference in the characteristics of global EPE-Hs and EPE-NHs during local warm seasons. The global average frequency and magnitude of EPEs in warm seasons are found to be incrementally increasing for both historical and future periods, consistent with the findings of Tabari22. Spatially, the magnitude of EPEs is projected to increase in most regions across the global landmass except Mediterranean under low emission scenarios, aligning with previous studies48,49,50. Based on the identification of CHPE, we categorize the EPEs into EPE-Hs and EPE-NHs, and investigate the spatiotemporal variations of their characteristics respectively. Using reanalysis product, we have identified that, despite occurring less frequently, EPE-Hs exhibit both greater duration and magnitude on the global average compared to EPE-NHs during the historical period. In the future, projections indicate significant differences in the global average characteristics of EPE-Hs and EPE-NHs. EPE-Hs are anticipated to become more frequent, with events that are longer in duration and more intense. Conversely, EPE-NHs are expected to decrease in frequency, while their duration and intensity are projected to remain relatively stable. This distinction may be attributed to the fact that EPE-Hs are predominantly induced by atmospheric rivers, which, according to Najibi and Steinschneider46, increase more significantly with climate warming than non-atmospheric river-induced precipitations. Furthermore, a notable escalation in the frequency, duration, and magnitude of EPE-Hs is projected for low latitude regions in the long-term future, including South Asia, Southeast Asia, Western and Central Africa, southern North America, and northern South America. These findings suggest a potential for heightened rainfall and flood risk in these regions following heat stress events under changing climatic conditions.

Subsequently, we explore the temperature sensitivity of the identified EPEs to discern where and how the responses to global warming differ between EPE-Hs and EPE-NHs across the global landmass. The MME reveals positive temperature sensitivity for most regions for all EPEs, with the exception of the Mediterranean, central America, certain coastlines of South America, Africa, and Australia, which corroborates with ref. 41. Moreover, a decline in future sensitivity for EPEs from the near-term to the long-term is projected, possibly due to precipitation increases at a slower rate than temperature43,51. When comparing EPE-Hs and EPE-NHs, the sensitivity of extreme precipitation for EPE-Hs exceeds 100%/°C in most land areas, particularly in low latitudes, contrasting with negative values for EPE-NHs in majority of the global lands. These findings indicate significant differences of EPE-Hs and EPE-NHs in their temperature sensitivity under global warming. Furthermore, the historical and future P–T scaling structures of the identified EPEs are examined for the global landmass and each climate region. For all EPEs in warm seasons, extreme precipitation intensity is found to increase monotonically and linearly with temperature. The scaling rate for the global average annual extreme precipitation is super C–C scaling under the 90th and 95th percentile threshold, which is less than the scaling rate in previous studies42,45,52. The discrepancy is because we only considered local summer season, in which the scaling rate has been proved to be lower than other seasons53,54. A new finding in this study is the distinct scaling structures of EPE-Hs and EPE-NHs, characterized by convex and concave P–T relationship curves, respectively. Regionally, the P–T relationship of EPE-Hs and EPE-NHs across 22 climate regions reveals two patterns: EPE-Hs show a peak precipitation intensity at a specific temperature in low latitudes and a continuous rise elsewhere, while EPE-NHs initially decrease then increase in low latitudes and monotonically decrease in others, indicating the importance of region-specific climate responses to global warming.

Having revealed the difference in the characteristics and temperature response of extreme precipitation in EPE-Hs and EPE-NHs, we further analyze the large-scale atmosphere conditions prior to the EPE-Hs and EPE-NHs in an attempt to explain the physical mechanism behind the differences. Considering both thermal and dynamical drivers of EPEs, we diagnose convective available potential energy (CAPE), specific humidity (SH), surface sensible heat flux (SSHF), vertically integrated moisture convergence (VIMC), and total column water vapor (TCWV). Given the insensitivity of large-scale environmental condition anomalies to the choice of 1, 2, or 3 days prior to EPEs, we opt for a composite analysis of atmospheric factors precisely one day before the onset of EPEs, as depicted in Fig. 8. The CAPE, SH, SSHF, and TCWV in the day before EPE-Hs are larger than that before EPE-NHs in the high latitudes of the Northern Hemisphere, coinciding with the greater duration and magnitude of EPE-Hs relative to EPE-NHs there (Fig. 1a). Preceding heat stress is linked to increased relative humidity (RH) and atmospheric instability before EPE-Hs, priming the environment for EPE-Hs. Previous studies have concluded that the convective precipitation responds much more sensitively to temperature increases than stratiform precipitation and increasingly dominates events of extreme precipitation in previous studies35,37. RH remains consistent and high as GSAT rises due to the monotonic increase in SH with warming. During EPE-Hs, warming is linked to a direct increase in atmospheric water content in an already near-saturated environment46. Conversely, as GSAT increases, the scaling rate in EPE-NHs surpasses that of EPE-Hs, potentially due to reduced RH at very warm temperatures42,55. This divergence may also be related to thermodynamic mechanisms, as atmospheric thermodynamics predominantly govern extreme precipitation, with atmospheric dynamics playing a modulating role36.

In summary, our study provides clear insights into the different characteristics of extreme precipitation within EPE-Hs and EPE-NHs, as observed and simulated. The findings underscore that EPEs with preceding heat stress exhibit heightened sensitivity to global warming compared to other heavy precipitation events. Notably, we emphasize the distinction in their P–T scaling structure of these EPEs, offering valuable reference and insight into warning and anticipation strategies across different regions. While detecting and presenting a global assessment of EPE-Hs and EPE-NHs is the priority and focus of this study, identifying the underlying mechanisms from a physical standpoint is an important and challenging task. Future studies should be undertaken to further investigate these mechanisms and help advance our understanding of extreme precipitation hazards.

Methods

Datasets

Our analysis covers global land areas, excluding desert regions where annual precipitation is less than 200 mm, as depicted in Supplementary Fig. 1. We utilize hourly 0.25° × 0.25° 2 m air temperature, 2 m dew point temperature, CAPE, SSHF, VIMC, and TCWV from global reanalysis product ERA5 and daily 0.5° × 0.5° precipitation from Climate Prediction Center (CPC) as observation for the 1979–2014 period. The ERA5 and CPC data are transformed into a daily scale and 1° × 1° resolution before implementing data analysis. We download daily precipitation, 2 m air temperature, and relative humidity from a MME including six CMIP6 ESMs (i.e., CNRM-CM6-1, EC-Earth3-Veg, KACE-1-0-G, MPI-ESM1-2-HR, MRI-ESM2-0, NorESM2-MM) for both the baseline (1979–2014) and future (2015-2099) period. Information of the six ESMs is presented in Supplementary Table 1. The mean equilibrium climate sensitivity is 3.71, falling within the always maintained range of 1.5–4.5 °C15,56. Projections under four future combined SSP–RCP scenarios are employed, i.e., SSP1-2.6 (+2.6 Wm−2; low forcing sustainability pathway), SSP2-4.5 (+4.5 Wm−2; medium forcing middle of the road pathway), SSP3-7.0 (+7.0 Wm−2; medium to high forcing regional rivalry pathway), and SSP5-8.5 (+8.5 Wm−2; high forcing fossil-fueled development pathway). A bilinear interpolation scheme is applied to interpolate the ESM data to a common 1° × 1° grid.

Identification and characterization of extreme precipitation events

For each grid-point, we use the 90th percentile of the daily observed precipitation in the warm season over 1979–2014 as the threshold. EPEs are identified where the daily precipitation is higher than the threshold for at least one day. Similarly, a heat stress event is defined when the daily lethal heat stress temperature (Th) exceeds its 90th percentile in the warm season over 1979–2014 for at least three consecutive days. Th is a widely used index to identify heat stress events57,58,59, which is calculated based on the widely used formula of wet bulb temperature (Tw)59,60.

where atan is the arc tangent, T is the dry air temperature (°C), \({T}_{w}\) is the wet bulb temperature (°C),\(\,{T}_{h}\) is the lethal heat stress temperature (°C), \({T}_{d}\) is the dewpoint temperature in Kelvin, \({RH}\) is the relative humidity (%), L is the enthalpy of vaporization (2.472\(\times\)106 J kg−1), \({R}_{w}\) is the gas constant for water vapor (461.5 J K−1 kg−1).

Subsequently, a CHPE is defined as a heat stress event followed by an EPE within a time interval (i.e., the period before the onset of the precipitation event and after the cessation of the heat stress event). In this study, we set the time interval to 3 days. Then the EPE in CHPEs are regarded as EPE-Hs and other EPEs are EPE-NHs. The schema of the identification above is displayed in Fig. 9. To ensure robustness, we conduct additional experiments with the percentile threshold set to the 95th, and the time interval varied to one and 7 days.

The EPEs are characterized by three metrics: frequency, defined as the number of events in a year; duration, defined as the average number of days in each event; and magnitude, defined as the average normalized daily anomalies in each event (Eq. 4).

where M and D are the magnitude and duration of an EPE, respectively. \({\Pr }_{d}\) is the precipitation on day d, \({\Pr }_{25{th}}\) and \({\Pr }_{75{th}}\) are the 25th and 75th percentile of daily precipitation on wet days over historical periods, respectively.

Quantile delta Mapping method

We apply the widely used Quantile delta Mapping (QDM) method61 to bias correct the simulated ESM daily variables based on observation data. The calibration results are provided in Supplementary Fig. 49. The QDM method preserves model-projected relative changes in quantiles, while at the same time correcting systematic biases in quantiles of a modeled series with respect to observed values. The algorithm combines two steps in sequence: first, future model outputs are detrended by quantile and bias corrected to observations by quantile mapping; second, model-projected relative changes in quantiles are superimposed on the bias-corrected model outputs.

where \({x}_{{bc}}(t)\) is the bias-corrected value, \({x}_{m,f}\left(t\right)\) is the model output in the future period at time \(t\), \({F}_{o,h}\), \({F}_{m,h}\), and \({F}_{m,f}\) mean the CDF for observation, simulated historical and future series, respectively.

Sensitivity of extreme precipitation to temperature

The sensitivity of extreme precipitation to temperature is quantified by dividing the relative change in the total amount of extreme precipitation in EPEs (unit: %) by the change in GSAT (unit: °C) from the baseline to future period. Specifically, we first calculate the total precipitation volume of the EPEs over the baseline and three future (near-term, mid-term, and long-term) periods. Then the multi-year averages for the precipitation volume and a difference between baseline and future periods are calculated. The relative change in extreme precipitation is ascertained by dividing the difference by the baseline precipitation volume. The change in GSAT is defined as the difference of multi-year average GSAT between the future and baseline periods.

Precipitation-temperature scaling relationships

We utilize the widely used quantile regression method to investigate the P–T scaling relationships for the EPEs32,46,62. After calculating the annual precipitation amount of EPEs for each grid-point, the area-weighted global and regional mean for each year is taken. The P–T relation structure is smoothed by LOWESS method63. Subsequently, a linear regression is fitted on the logarithm of running averaged precipitation intensity and GSAT (Eq. 6). The P–T scaling rate (α, unit: %/°C) is estimated using an exponential transformation of the regression coefficient (Eq. 7). When detecting the P–T relationship for climate regions, we perform the analysis using RSAT instead of GSAT.

where P and T are the smoothed precipitation and GSAT, respectively. \({\rm{\alpha }}\) is the P–T scaling rate, b is the linear regression coefficient.

Data availability

The daily ESM outputs are from the CMIP6 archive (see Supplementary Table 1, https://esgf-node.ipsl.upmc.fr/search/cmip6-ipsl/). The ERA5 data are from the Copernicus Climate Change Service, Climate Data Store (https://doi.org/10.24381/cds.adbb2d47). The CPC precipitation data can be download from the NOAA Physical Sciences Laboratory (https://psl.noaa.gov/data/gridded/data.cpc.globalprecip.html).

Code availability

The source codes for the analyses of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Kirchmeier-Young, M. C. & Zhang, X. Human influence has intensified extreme precipitation in North America. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117, 13308–13313 (2020).

Palmer, T. N. & Räisänen, J. Quantifying the risk of extreme seasonal precipitation events in a changing climate. Nature 415, 512–514 (2002).

Winter, S. C. et al. Extreme weather should be defined according to impacts on climate-vulnerable communities. Nat. Clim. Chang. 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-024-01983-7 (2024).

WMO. Atlas of Mortality and Economic Losses from Weather, Climate and Water-related Hazards. https://public.wmo.int/en/resources/atlas-of-mortality (2023).

IPCC. Climate Change 2022—Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability: Working Group II Contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. (Cambridge University Press, 2023). https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009325844.

AghaKouchak, A. et al. Climate extremes and compound hazards in a warming world. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 48, 519–548 (2020).

Bevacqua, E. et al. Guidelines for studying diverse types of compound weather and climate events. Earths Future 9, e2021EF002340 (2021).

Zscheischler, J. et al. Future climate risk from compound events. Nat. Clim. Chang. 8, 469–477 (2018).

Zscheischler, J. et al. A typology of compound weather and climate events. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 1, 333–347 (2020).

Sauter, C., Catto, J. L., Fowler, H. J., Westra, S. & White, C. J. Compounding heatwave-extreme rainfall events driven by fronts, high moisture, and atmospheric instability. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 128, e2023JD038761 (2023).

Speizer, S., Raymond, C., Ivanovich, C. & Horton, R. M. Concentrated and intensifying humid heat extremes in the IPCC AR6 regions. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2021GL097261 (2022).

Ning, G. et al. Rising risks of compound extreme heat-precipitation events in China. Int. J. Climatol. 42, 5785–5795 (2022).

Zhang, W. & Villarini, G. Deadly compound heat stress‐flooding hazard across the Central United States. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e2020GL089185 (2020).

You, J., Wang, S., Zhang, B., Raymond, C. & Matthews, T. Growing threats from swings between hot and wet extremes in a warmer world. Geophys. Res. Lett. 50, e2023GL104075 (2023).

Zhou, Z. et al. Global increase in future compound heat stress-heavy precipitation hazards and associated socio-ecosystem risks. Npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 7, 1–14 (2024).

Aihaiti, A., Jiang, Z., Zhu, L., Li, W. & You, Q. Risk changes of compound temperature and precipitation extremes in China under 1.5 °C and 2 °C global warming. Atmos. Res. 264, 105838 (2021).

Khan, M., Bhattarai, R. & Chen, L. Elevated risk of compound extreme precipitation preceded by extreme heat events in the upper Midwestern United States. Atmosphere 14, 1440 (2023).

Wu, S. et al. Increasing compound heat and precipitation extremes elevated by urbanization in South China. Front. Earth Sci. 9, 636777 (2021).

You, J. & Wang, S. Higher probability of occurrence of hotter and shorter heat waves followed by heavy rainfall. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48, e2021GL094831 (2021).

Myhre, G. et al. Frequency of extreme precipitation increases extensively with event rareness under global warming. Sci. Rep. 9, 16063 (2019).

Papalexiou, S. M. & Montanari, A. Global and regional increase of precipitation extremes under global warming. Water Resour. Res. 55, 4901–4914 (2019).

Tabari, H. Climate change impact on flood and extreme precipitation increases with water availability. Sci. Rep. 10, 13768 (2020).

IPCC. Climate Change 2021—The Physical Science Basis: Working Group I Contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (Cambridge University Press, 2021). https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009157896.

O’Neill, B. C. et al. The Scenario Model Intercomparison Project (ScenarioMIP) for CMIP6. Geosci. Model Dev. 9, 3461–3482 (2016).

Zhang, Q. et al. High sensitivity of compound drought and heatwave events to global warming in the future. Earths Future 10, e2022EF002833 (2022).

Zhou, Z. et al. Projecting global drought risk under various SSP‐RCP scenarios. Earths Future 11, e2022EF003420 (2023).

Donat, M. G. et al. How credibly do CMIP6 simulations capture historical mean and extreme precipitation changes? Geophys. Res. Lett. 50, e2022GL102466 (2023).

Lei, X. et al. Evaluation of CMIP6 models and multi-model ensemble for extreme precipitation over arid Central Asia. Remote Sens. 15, 2376 (2023).

McCrystall, M. R., Stroeve, J., Serreze, M., Forbes, B. C. & Screen, J. A. New climate models reveal faster and larger increases in Arctic precipitation than previously projected. Nat. Commun. 12, 6765 (2021).

Srivastava, A., Grotjahn, R. & Ullrich, P. A. Evaluation of historical CMIP6 model simulations of extreme precipitation over contiguous US regions. Weather Clim. Extrem. 29, 100268 (2020).

Feng, T., Zhu, X. & Dong, W. Historical assessment and future projection of extreme precipitation in CMIP6 models: global and continental. Int. J. Climatol. 43, 4119–4135 (2023).

Ali, H. et al. Towards quantifying the uncertainty in estimating observed scaling rates. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2022GL099138 (2022).

Screen, J. A. & Simmonds, I. Amplified mid-latitude planetary waves favour particular regional weather extremes. Nat. Clim. Chang. 4, 704–709 (2014).

Allen, M. R. & Ingram, W. J. Constraints on future changes in climate and the hydrologic cycle. Nature 419, 224–232 (2002).

Berg, P., Moseley, C. & Haerter, J. O. Strong increase in convective precipitation in response to higher temperatures. Nat. Geosci. 6, 181–185 (2013).

John, A., Douville, H., Ribes, A. & Yiou, P. Quantifying CMIP6 model uncertainties in extreme precipitation projections. Weather Clim. Extrem. 36, 100435 (2022).

Prein, A. F. et al. The future intensification of hourly precipitation extremes. Nat. Clim. Chang. 7, 48–52 (2017).

Ghausi, S. A., Ghosh, S. & Kleidon, A. Breakdown in precipitation–temperature scaling over India predominantly explained by cloud-driven cooling. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 26, 4431–4446 (2022).

Hosseini-Moghari, S.-M., Sun, S., Tang, Q. & Groisman, P. Y. Scaling of precipitation extremes with temperature in China’s mainland: Evaluation of satellite precipitation data. J. Hydrol. 606, 127391 (2022).

Visser, J. B., Wasko, C., Sharma, A. & Nathan, R. Eliminating the “Hook” in precipitation–temperature scaling. J. Clim. 34, 9535–9549 (2021).

Liang, J., Liu, X., AghaKouchak, A., Ciais, P. & Fu, B. Asymmetrical precipitation sensitivity to temperature across global dry and wet regions. Earths Future 11, e2023EF003617 (2023).

Yin, J. et al. Large increase in global storm runoff extremes driven by climate and anthropogenic changes. Nat. Commun. 9, 4389 (2018).

Fowler, H. J. et al. Anthropogenic intensification of short-duration rainfall extremes. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2, 107–122 (2021).

Knist, S., Goergen, K. & Simmer, C. Evaluation and projected changes of precipitation statistics in convection-permitting WRF climate simulations over Central Europe. Clim. Dyn. 55, 325–341 (2020).

Varghese, S. J. et al. Precipitation scaling in extreme rainfall events and the implications for future indian monsoon: analysis of high-resolution global climate model simulations. Geophys. Res. Lett. 51, e2023GL105680 (2024).

Najibi, N. & Steinschneider, S. Extreme precipitation-temperature scaling in California: the role of atmospheric rivers. Geophys. Res. Lett. 50, e2023GL104606 (2023).

Kendall, M. G. Rank Correlation Methods (Griffin, 1948).

Sun, Q., Zhang, X., Zwiers, F., Westra, S. & Alexander, L. V. A global, continental, and regional analysis of changes in extreme precipitation. J. Clim. 34, 243–258 (2021).

Thackeray, C. W., Hall, A., Norris, J. & Chen, D. Constraining the increased frequency of global precipitation extremes under warming. Nat. Clim. Chang. 12, 441–448 (2022).

Zittis, G., Bruggeman, A. & Lelieveld, J. Revisiting future extreme precipitation trends in the Mediterranean. Weather Clim. Extrem. 34, 100380 (2021).

Zhang, W. et al. Increasing precipitation variability on daily-to-multiyear time scales in a warmer world. Sci. Adv. 7, eabf8021 (2021).

Bao, J., Sherwood, S. C., Alexander, L. V. & Evans, J. P. Future increases in extreme precipitation exceed observed scaling rates. Nat. Clim. Chang. 7, 128–132 (2017).

Tabari, H. Extreme value analysis dilemma for climate change impact assessment on global flood and extreme precipitation. J. Hydrol. 593, 125932 (2021).

Zeder, J. & Fischer, E. M. Observed extreme precipitation trends and scaling in Central Europe. Weather Clim. Extrem. 29, 100266 (2020).

Byrne, M. P. & O’Gorman, P. A. Trends in continental temperature and humidity directly linked to ocean warming. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 115, 4863–4868 (2018).

Schlund, M., Lauer, A., Gentine, P., Sherwood, S. C. & Eyring, V. Emergent constraints on equilibrium climate sensitivity in CMIP5: do they hold for CMIP6? Earth Syst. Dyn. 11, 1233–1258 (2020).

Schwingshackl, C., Sillmann, J., Vicedo‐Cabrera, A. M., Sandstad, M. & Aunan, K. Heat stress indicators in CMIP6: estimating future trends and exceedances of impact‐relevant thresholds. Earths Future 9, e2020EF001885 (2021).

Wang, P., Yang, Y., Tang, J., Leung, L. R. & Liao, H. Intensified humid heat events under global warming. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48, e2020GL091462 (2021).

Yin, J. et al. Global increases in lethal compound heat stress: hydrological drought hazards under climate change. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2022GL100880 (2022).

Stull, R. Wet-bulb temperature from relative humidity and air temperature. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 50, 2267–2269 (2011).

Cannon, A. J., Sobie, S. R. & Murdock, T. Q. Bias correction of GCM precipitation by quantile mapping: how well do methods preserve changes in quantiles and extremes? J. Clim. 28, 6938–6959 (2015).

Pendergrass, A. G., Lehner, F., Sanderson, B. M. & Xu, Y. Does extreme precipitation intensity depend on the emissions scenario? Geophys. Res. Lett. 42, 8767–8774 (2015).

Utsumi, N., Seto, S., Kanae, S., Maeda, E. E. & Oki, T. Does higher surface temperature intensify extreme precipitation? Geophys. Res. Lett. 38, L16078 (2011).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Third Xinjiang Comprehensive Scientific Expedition Project (No.2022xjkk0105) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (52279023). We also acknowledge support from Wuhan Natural Science Foundation Special Zone Project (No.2024040701010035) and the China Yangtze Power Co., Ltd. (CYPC) Foundation (No.Z242302022).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.Z. and Z.Z designed the research. Z.Z. defined details of the framework for this study, conducted all analyses, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors worked together on the interpretation of the results and writing of the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, Z., Zhang, L., Zhang, Q. et al. Amplified temperature sensitivity of extreme precipitation events following heat stress. npj Clim Atmos Sci 7, 243 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-024-00796-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-024-00796-x

This article is cited by

-

Risk of successive hot-pluvial extremes on crop yield loss over global breadbasket regions

Communications Earth & Environment (2025)

-

Substantial increases in compound climate extremes and associated socio-economic exposure across China under future climate change

npj Climate and Atmospheric Science (2025)

-

Confronting the dual climate challenge: a spatiotemporal assessment of extreme precipitation-high temperature events in China, 1981–2100

International Journal of Environmental Science and Technology (2025)