Abstract

The northeast (NE) Pacific has experienced significant marine heatwaves (MHWs) in recent years, commonly known as “warm blobs.” This study examines the impact of Arctic warming, particularly in the Eastern Siberian-Chukchi Sea (ES-CS) region, on the occurrence of these warm blobs during boreal winters. We found that Arctic warming triggers a positive phase of the Tropical/Northern Hemisphere-like (TNH-like) atmospheric circulation, creating a pronounced high-pressure system over the Alaskan region. This system leads to easterly wind anomalies that weaken prevailing westerlies, reducing heat loss from the ocean to the atmosphere and cold advection in the upper ocean. Consequently, sea surface temperatures rise, favoring the development of warm blobs. A numerical experiment confirmed that the projected changes in the ES-CS region impact warm blobs occurrences by inducing this high-pressure system, linking Arctic warming to MHWs in the NE Pacific.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the winter of 2013/14, the northeast Pacific (NE) experienced a significant rise in ocean temperatures, leading to the formation of a marine heatwave (MHW), known as “warm blob”, which peaked at approximately 2.5°C above the average winter temperature1. This anomaly was particularly pronounced in the Gulf of Alaska, and by the winter of 2014/15, warm waters had formed an arc-shaped pattern along the North American coasts and extended to coastal regions2,3,4. The warm blob had profound effects, such as reduced primary productivity5, with consequent fishery closures6, delayed upwelling off the California coast7,8, and broader climatic impacts, including warmer winters in Alaska9, cold winter10 and warm spring1 across North America, and severe drought conditions in California6.

Extensive research has pointed out that the formation of the warm blob is closely associated with the presence of an anomalous atmospheric ridge over the NE Pacific1,2,3,10,11,12,13,14,15. This ridge was often accompanied by a weakened Aleutian Low16, which significantly reduced the westerlies1,10. As a result, these weakened winds led to reduced heat loss from the ocean to the atmosphere and weakened cold advection in the upper ocean, contributing to the formation of the warm blob1,17. Research suggests that atmospheric teleconnections, originating from both the tropics and extratropics, may induce this unusual atmospheric ridge over the NE Pacific10,12,15,18. For instance, positive sea surface temperature (SST) anomalies in the tropical Pacific play an important role in generating such unusual atmospheric ridge by triggering Rossby wave10,12. Lee et al.18 have further revealed that SST anomalies in the tropics and extratropical North Pacific play a critical role in establishing the high-pressure system. In a recent study, Shi et al.19 identified 13 times of cold-season warm blobs in the NE Pacific and revealed the role of extratropical forcing, including contributions from the Atlantic and Mediterranean, on the development of the anomalous atmospheric ridge over the NE Pacific. However, previous studies have mainly focused on the role of atmospheric circulation and oceanic processes in tropical and extratropical regions, much less attention has been focused on the influence of the Arctic region. In fact, the reduction in sea ice concentration (SIC) in the Arctic did contribute to the strengthening of anomalous ridge during the winter of 2013/1418, indicating the significant role of Arctic in shaping such atmospheric patterns.

Since the 1970s, the Arctic air temperature has risen at a rate twice that of the global average, a phenomenon commonly referred to as Arctic amplification (AA)20,21. This rapid increase in surface air temperature (SAT), along with a decline in SIC, has significantly influenced mid-latitude weather and climate by modifying large-scale atmospheric circulation patterns18,22,23,24,25,26. In particular, abnormal warmth in the Barents-Kara Sea (BKS) region and the East Siberian-Chukchi Sea (ES-CS) has been associated with severe cold winter in East Asia and North America, respectively, a phenomenon referred to as the warm Arctic cold continents (WACC)24. This phenomenon occurs as a result of anomalous anticyclones forming over the BKS and ES-CS, leading to an intensified Siberian High and a weakened Aleutian Low, which in turn influences continental air temperatures24. The winter of 2013/14 witnessed a significant warm air temperature anomaly in the Chukchi Sea, which partly contributed to the formation of the unusual atmospheric ridge and subsequently led to the formation of the warm blob18. Through a comparison of “low-ice” and “high-ice” model scenarios, Cvijanovic et al. 27 demonstrated that Arctic sea-ice loss can impact the Aleutian Low via teleconnection, triggering an anticyclonic circulation over the NE Pacific. This circulation induced the severe drought in California experienced from 2012 to 201628. These results add to the case that the observed changes in Arctic are significantly influencing mid-latitude climate through such atmospheric systems.

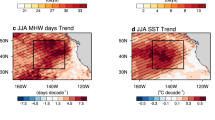

Prior research has largely focused on the effects of Arctic warming on SAT and precipitation patterns24,27,28, while the impact on oceanic extreme events, such as MHWs, desires further investigation. A recent study found that Arctic warming induced a positive phase of the North Pacific Oscillation-like (NPO)29 atmospheric circulation pattern over the NE Pacific, resulting in a decrease in low-level cloud fraction from late spring to early summer. These changes led to an increase in solar radiation and a decrease in latent heat loss, which in turn contributed to an increase in SST and MHW days30. This mechanism is likely applicable to explain the formation of the 2019 summer North Pacific MHW31, but different from that of the warm blob in the winter of 2013/141,17. Song et al. 30 highlighted the substantial effects of summer Arctic warming on the occurrence of MHWs in the NE Pacific. Notably, Arctic warming displays significant seasonal variations that are most pronounced in the boreal autumn and winter22. Given the prominent effect of winter Arctic warming, this study employed a comprehensive dataset and model simulations over the past four decades, aiming to examine whether such warming similarly impacts the occurrence of MHWs in the NE Pacific.

Results

Observed warm blobs in the northeast Pacific

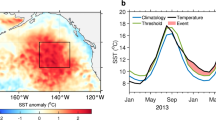

Based on monthly SST data, we identified five significant warm blob events occurring in the winters of 1990/91, 2004/05, 2010/11, 2013/14, and 2021/22 in the NE Pacific region of interest (140°–170°W, 30°–50°N) during the period from 1979 to 2021 (Fig. 1a). The composition of these warm blobs revealed a distinct winter SST anomaly in the NE Pacific, with temperature anomalies exceeding 1°C. This anomaly persisted for at least two months and was centered around 40°N in the NE Pacific (Fig. 1b). Simultaneously, a composite analysis of the atmospheric circulation anomalies during these five warm blob occurrences showed a notable anomalous high-pressure system above the NE Pacific, extending from the upper atmosphere to the sea surface in a quasi-barotropic structure (Fig. 1c). This anomaly structure was accompanied by a significant anticyclonic wind field that transported Arctic cold air towards North America24. Meanwhile, the notably weakened background westerly winds provided favorable and crucial atmospheric circulation conditions for the formation of the warm blobs.

a Time series of normalized winter (DJF) SST anomalies from 1979 to 2021 based on ERSST v5 dataset. The gray bars represent the monthly SST anomalies, while the dotted red line signifies the winter SST anomalies averaged in NE Pacific (black box; 140°–170°W, 30°–50°N). The pink shadings indicate the warm blobs. Composite anomalies of b SST and c 500-hPa geopotential height (Z500) along with winds associated with the identified warm blobs in the NE Pacific.

Trends in SAT in the Northern Hemisphere during 1979–2021 winter

The warming in the Arctic has significantly influenced mid-latitude weather and climate by modifying atmospheric circulation patterns18,22,23,24,25,26. During the winters from 1979 to 2021 (December-January-February, DJF), the Arctic region has shown an overall warming trend, notably in the ES-CS, which has been identified as a hotspot for Arctic warming20,22,23,24 (Fig. 2a, b). To explore the variability of the winter SAT anomalies averaged over the ES-CS region (160°E−160°W, 70°−80°N), we divided the period from 1979 to 2021 into two sub-periods: 1979–1994 and 1995–2021. The analysis revealed a substantial warming trend in the latter period, with SAT anomalies increasing by an average rate of 0.03°C/year (p < 0.01), contrasted by a slight cooling trend of −0.01°C/year (p > 0.05) from 1979 to 1994. Additionally, there was also an increase in mean SAT anomalies, from 0.11°C (1979–1994) to 0.44°C (1995–2021), accompanied by an increase in the standard deviation of SAT anomalies in the ES-CS region from 0.20°C to 0.39°C (Fig. 2c). These shifts coincide with the notable change in 1995 where marked reductions in sea-ice concentration have occurred22. The heightened interannual variability after mid-1990s is evidenced by the occurrence of extreme warm and cold SAT anomalies in the ES-CS region, including the highest (2017) and the lowest (1997) recorded temperatures (Fig. 2c). ERA5 reanalysis data similarly indicate a significant increase in SAT variability (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Trends in winter (DJF) SAT from a 1979 to 2021 and b 1995 to 2021 based on observed data. The black boxes indicate the ES-CS (160°E−160°W, 70°−80°N) and NE Pacific regions (140°–170°W, 30°–50°N). c Time series of DJF-mean ES-CS SAT anomalies during winter from 1979 to 2021 (black line), with linear trends shown in red lines. Mean values and standard deviations of ES-CS SAT anomalies were calculated for the periods before and after mid-1990s. GOA: Gulf of Alaska; NA: North America. Spatial patterns of winter d Z500 and wind anomalies, e 850-hPa geopotential height (Z850) and wind anomalies regressed onto the ES-CS SAT from 1979 to 2021. Dotted regions indicate areas that satisfy the 95% confidence levels.

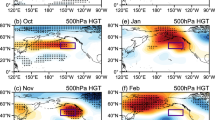

Teleconnection between Arctic warming and NE Pacific warm blob

To investigate the influence of Arctic warming on the NE Pacific warm blobs, we conducted a regression analysis of ES-CS SAT against 500-hPa geopotential height (Z500) anomalies. The results revealed a significant positive Z500 anomaly in the NE Pacific and a relatively weak positive Z500 anomaly over the tropical Atlantic, while a negative Z500 anomaly was observed in the middle and high latitudes of North America (Fig. 2d). Interestingly, we found that the regression results exhibit similarities to the Z500 fields associated with the positive phase of the Tropical/Northern Hemisphere (TNH; Supplementary Fig. 2a), characterized by a tripole structure across the Northern Hemisphere32,33,34. The spatial correlation coefficient between the observed response to ES-CS warming and the TNH-induced pattern is 0.91, which exceeds 99% confidence level. For clarity, we have coined the term “TNH-like” features to describe this atmospheric circulation pattern induced by Arctic warming. This pattern notably includes an unusual equivalent barotropic anticyclone across the NE Pacific (Fig. 2d, e), crucial for the warm blob formation1 (Fig. 1c), leading to easterly wind anomalies around 40°–60°N in the Gulf of Alaska and a significant decrease in prevailing westerly winds over the NE Pacific (Fig. 2d, e).

Additionally, the regression analysis between ES-CS SAT and winter SST anomalies indicated a significant warm blob-like SST anomaly in the NE Pacific region coinciding with an increase in winter ES-CS SAT anomalies (Fig. 3b, Supplementary Fig. 3a, b). From 1979 to 2021, significant correlations were found between ES-CS SAT anomalies and NE Pacific SST anomalies from the ERSST v5 dataset, with a correlation coefficient of 0.42 that is significant at the 95% confidence level (Supplementary Fig. 3c). Notably, while the correlation was not significant from 1979 to 1994, it strengthened from 1995 to 2021, with a correlation coefficient of 0.47, which indicates a significant correlation that exceeds 95% confidence level. These results suggest a possible strengthening correlation in the context of intensified Arctic warming. Furthermore, the SST anomalies related to ES-CS SAT were found to mirror the regressed SST anomaly fields associated with the positive phase of TNH, displaying a high spatial correlation coefficient of 0.93, which exceeds 99% confidence level (Supplementary Fig. 2b). These findings imply that Arctic warming could contribute to NE Pacific warm blob formation through atmospheric circulation patterns resembling the TNH pattern.

a Regression maps of winter 10 m wind fields (arrows), wind speed anomalies (shading), and SLP anomalies (contours) obtained from the ERA5 reanalysis dataset regressed onto the SAT over the ES-CS region for the period of 1979–2021. Regression maps of anomalous winter b SST from ERSST v5 and ML heat budget terms (°C/sea) regressed onto the SAT over the ES-CS region from 1979 to 2021: c ML ocean temperature tendency; d net surface air-sea heat flux; e horizontal heat advection; and f residual term. The three-dimensional ocean temperature and current data were obtained from the GODAS dataset, while the air-sea heat flux data were from the ERA5 reanalysis.

Physical processes drive NE Pacific warm events in winter

To understand the driving mechanism for the NE Pacific winter warm blobs due to Arctic warming in the ES-CS region, we further examined the ocean mixed layer (ML) heat budget. Our analysis identified two primary processes influencing the winter warming tendency in the NE Pacific (Fig. 3). Initially, the easterly winds of the southern branch of the anticyclone weakened the surface background wind intensity (Fig. 3a). This weakening of wind fields resulted in a positive anomaly in the net surface air-sea heat flux (Fig. 3d), indicating a decrease in ocean-to-atmosphere heat loss during winter, particularly in terms of latent heat flux, which is closely linked to wind speed. Furthermore, the decrease in strength of the prevailing westerlies also impacts the warming tendency by affecting heat advection (Fig. 3e). With the weakened westward winds, the wind-induced Ekman transport of cold water from high-latitude regions significantly decreased, leading to positive anomalies in horizontal ocean heat advection. This change indicates that heat within the study region is not being lost as efficiently as in the past, leading to rising ocean temperatures. Additionally, our analysis reveals slightly negative anomalies in vertical heat exchange at the bottom of the ML in the NE Pacific, known as entrainment (Fig. 3f), contributing to a cooling effect in the ML in that region; however, its impact is comparatively less significant in comparison to the aforementioned processes. In summary, the reduction in wintertime cooling allows for heat accumulation in the ML, contributing to the formation of warm blobs in the NE Pacific (Fig. 3c).

Validation by CAM5 experiment

To further verify the potential causality between ES-CS warming and the formation of the NE Pacific warm blobs, an atmospheric simulation experiment on Arctic warming by using CAM5 (the Community Atmosphere Model version 5) was conducted (“Methods”). The interdecadal relationship between Arctic warming and the North Pacific, as revealed by CAM5 outputs, indicates a significant weakening of the Aleutian Low during winter in periods of Arctic warming35,36 (Supplementary Fig. 4). In terms of interannual variability, the model results confirm that the increase in winter SAT in the ES-CS region indeed triggers a substantial high-pressure system over the Gulf of Alaska (Fig. 4). The spatial correlation coefficient between the simulated Z500 responses to ES-CS SAT warming and the observed responses is 0.63, which exceeds 99% confidence level, indicating a significant similarity in their spatial distributions. It is noteworthy that, despite the slight northward displacement of the center of the simulated high-pressure system in comparison to the observed structure, the downstream teleconnection patterns remain identifiable (Fig. 4). The simulated response of 500-hPa and 850-hPa winds to the ES-CS SAT forcing both exhibit easterly anomalies over the NE Pacific (Fig. 4a, b). This is supported by a correlation coefficient of −0.47 between observed ES-CS SAT and 850-hPa zonal wind speed anomalies, which exceeds 99% confidence level, and closely matches the model’s results of −0.42, which also exceeds 99% confidence level, thus being in good agreement with the observed results (Fig. 4c). Although the model simulation tends to underestimate the responses relative to the observations, these findings robustly support the hypothesis that Arctic warming induces atmospheric conditions that are conducive to the formation of warm blobs in the NE Pacific during winter.

Simulated winter a Z500 (shading) and 500-hPa wind fields (arrows), b Z850 and 850-hPa wind fields (arrows), regressed against the SAT anomalies in the ES-CS region from 1979 to 2020. Dotted regions represent areas that satisfy the 95% confidence levels. c Scatterplot of observed (ERA5) and modeled ES-CS (160°E−160°W, 70°−80°N) SAT and 850-hPa zonal winds anomalies over the NE Pacific (140°–170°W, 30°–50°N) from 1979 to 2020. Blue dots represent observation data, while red dots represent model data.

Discussion

The NE Pacific is one of the hotspot regions in terms of MHWs, which is characterized by the presence of warm blobs (Fig. 1). The formation of these warm blobs in this region is influenced by the tropical Pacific Ocean10,12,18, the North Pacific18, and the Atlantic and Mediterranean19. In comparison to previous studies, this study places emphasis on the potential role of the Arctic region and provides further insight into the mechanisms that drive the formation of warm blobs in the NE Pacific (Fig. 5). The analysis indicates that warming in the Arctic, particularly in the ES-CS region (Fig. 2), is likely to affect the formation of winter warm blob-like SST anomaly in the NE Pacific (Fig. 3b) by triggering the prevailing atmospheric circulation patterns (Figs. 1 and 2). Both observational data and model simulation indicate that the crucial connection between the two phenomena is an anomalous high-pressure system over the NE Pacific, which is a consequence of Arctic warming (Figs. 2 and 4). This anomalous anticyclone suggests a weakening of the Aleutian Low and an increase in blocking events24,37,38, which subsequently reduces the intensity of mid-latitude westerlies. The reduction in westerly winds leads to a decrease in horizontal ocean advection and ocean-to-atmosphere heat loss during winter in the study region (Fig. 3). Consequently, more heat accumulates in the ML, creating conditions conducive to the occurrence of the warm blobs in the NE Pacific.

The anomalous high-pressure system, characterized by robust anticyclonic winds induced by Arctic warming, plays a significant role in generating warm blobs and SST anomalies in the NE Pacific (Figs. 2 and 3). This system results in the weakening of the Aleutian Low, which in turn leads to a weakening of the prevailing westerlies through the southern branch of the clockwise wind anomalies. The diminished winds have the potential to modify ocean-atmosphere thermal coupling by influencing wind speed in the bulk formula for turbulent heat flux and impacting the advection of heat through ocean circulation. These results align with our findings that these two processes predominantly drive the warming in the NE Pacific region (Fig. 3). The mechanism of the formation of winter SST anomalies in the NE Pacific during the warm ES-CS period resembles the Pacific blob associated with the TNH-like pattern33. The high-pressure system resulting from Arctic warming exhibits similarities to the TNH pattern (Fig. 2d and Supplementary Fig. 2). Additionally, the formation of the warm blob in 2013/14 was influenced by weakened horizontal wind speeds and air temperature anomalies related to meridional winds. This is due to the anomalous southeast wind field generated by the abnormal high-pressure system, which transfers warm and moist air masses from lower latitudes to the study region17. However, the high-pressure system induced by Arctic warming mainly leads to anomalous easterly winds, resulting in changes dominated by zonal winds (Fig. 2). This mechanism differs slightly from the blob formation observed in 2013/14. Furthermore, the northerly winds associated with the specific formation of the anomalous anticyclone bring Arctic air into northern North America, leading to severe cold winters24.

The CAM5 model of the Arctic warming experiment confirms that warming in the ES-CS region has produced a robust high-pressure system over Alaska, along with two weaker pressure systems, i.e. negative over Hudson Bay and positive over central North America (Fig. 4a, b). This pattern bears resemblances to the observational regression results (Fig. 2d, e); however, the simulated high-pressure system’s center is notably displaced further north than observed. This discrepancy might be attributed to the absence of tropical forcing, which typically acts to weaken the Aleutian Low and warm SST in the NE Pacific39. We also observed that this pattern aligns with the positive phase of the TNH pattern32,34. The spatial correlation coefficient between the modeled and observed response to ES-CS warming and the TNH-induced pattern is significant at 0.46 and 0.91, respectively, which exceeds 99% confidence level. The pattern of SST anomalies in the NE Pacific also exhibits significant similarities to the TNH-induced SST pattern, with a spatial correlation coefficient of 0.93 that exceeds 99% confidence level (Supplementary Fig. 2), further supporting the influence of ES-CS warming and TNH-like atmospheric circulation on the NE Pacific SST pattern. During the winter of 2013/14, the TNH index reached its second-highest value since 197940, and the presence of the TNH pattern contributed to the formation of the warm blob in the NE Pacific1,17,41. A previous study has underscored the influence of Arctic warming in the ES-CS region in the expansion of TNH patterns and resultant SST anomalies in the NE Pacific42. Nevertheless, our investigation indicates that an increase in ES-CS SAT can trigger TNH-like patterns and exert an impact on the SST pattern in the NE Pacific (Fig. 3b). These findings are supported by an extensive multi-model analysis, where simulations from 34 CMIP6 (Coupled Model Intercomparison Project phase 6) models partially reproduced the observed anticyclonic circulation anomalies associated with ES-CS SAT anomalies (Supplementary Fig. 5 and Table S1), though the results were weaker compared to observations and CAM5 results. Possible reasons for the discrepancy between the model and observations include the fact that CMIP6 historical data only extend to 2014 and the time range does not fully match the observations. Additionally, the model may have underestimated the weakening of the Aleutian Low intensity in the study region compared to observations43. The Arctic region has experienced much stronger warming than the global average in the past several decades and is also expected to continue the warming amplification in the future44. And Arctic warming may act alone or in conjunction with other regions such as the tropical Pacific10,45, the Atlantic and Mediterranean19, which leads to more frequent warm blob events in the NE Pacific and further impacts on marine ecosystems.

Arctic warming has been identified as a driver of changes in the mid-latitude atmospheric circulation, specifically by influencing the behavior of the polar jet stream22,23. Specifically, Arctic warming leads to an increase in geopotential height thickness and a decrease in the meridional gradient, which in turn can slow the polar jet stream46. Furthermore, the resulting weakened zonal winds can enhance the occurrence of slower and more amplified Rossby waves, thereby increasing the likelihood of atmospheric blocking events22,23. This phenomenon can potentially result in a TNH-like atmospheric circulation pattern characterized by above-average heights over the Gulf of Alaska32,34. Regression analysis of wave activity flux47 onto the ES-CS SAT time series (Supplementary Fig. 6) suggests that the anticyclone pattern partly originates from the Arctic region, which reflects the energy propagation of wave trains. This anomalous high-pressure system has the effect of weakening the winter cooling in the upper ocean and influencing the SST pattern in the NE Pacific. It is important to note that, in addition to the Arctic-midlatitude connection, other factors such as El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO)32,34,48,49, wave activity propagation from the western tropical Pacific11,15,18,45, and internal dynamics in the atmosphere12,50 are associated with TNH-like patterns48,49, which can further influence SST changes in the NE Pacific40. Moreover, the SST variability in the NE Pacific Ocean is significantly influenced by tropical Pacific51,52. Consequently, it is crucial to consider the contribution from the tropical Pacific, as it has the potential to weaken the Aleutian Low39 and induce anomalous atmospheric circulation pattern that closely resembles that regressed with SST warming in the NE Pacific (Supplementary Fig. 7). Here, the winter warm blob event of 2013/14 was selected as a case study to attempt to evaluate the extent to which Arctic warming accounts for SST variability in the NE Pacific compared to tropical forcing. The results indicate that both tropical forcing and Arctic warming can induce easterly wind anomalies, which are critical for the development of the warm blob in the NE Pacific. Notably, Arctic warming contributes to approximately half of the wind speed anomalies associated with tropical forcing during this event. Therefore, further detailed research using a coupled atmosphere-ocean model is necessary to quantify the relative contributions of tropical forcing and Arctic warming to SST variability in the NE Pacific.

In summary, our study highlights the potential role of Arctic warming in the ES-CS region for the occurrence of warm blobs in the NE Pacific through Arctic-midlatitude interactions. Using observational data and CAM5 model, we demonstrate that warming in the ES-CS region generates a remarkably warm blob-like pattern in the NE Pacific, contributing to the development of MHWs by inducing a TNH-like pattern. Over recent decades, the prevalence of the MHWs in the NE Pacific has shown an upward trend, which is projected to persist as Arctic warming continues. Further investigation into the intricate dynamics underlying the formation of these extreme oceanic events is essential for understanding the additional risks posed to marine ecosystems.

Methods

Reanalysis data

SAT trends were derived from HadCRUT5 data spanning from 1979 to 202253. Monthly data on SAT, SST, air-sea heat flux, wind fields, sea level pressure (SLP), and geopotential height were obtained from the fifth generation (ERA5) European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) covering the period from 1979 to 2022 with a spatial resolution of 0.25° × 0.25°54. SST data from the Hadley Centre Sea Ice and Sea Surface Temperature data set (HadISST) with 1° spatial resolution55, and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Extended Reconstructed SST v5 (ERSST v5) with 2° spatial resolution56 were also used. Three-dimensional monthly data on ocean subsurface temperature, velocity, and mixed layer (ML) depth from 1980 to 2022 were obtained from the National Centers for Environmental Prediction (NCEP) Global Ocean Data Assimilation System (GODAS) gridded product, featuring a horizontal resolution of 1/3° latitude × 1° longitude and 40 vertical levels57. The depth of the ML refers to the depth at which the buoyancy difference equals 0.03 cm/s2 relative to the surface level. This study primarily focuses on interannual variations, and a 7-year high-pass Lanczos filter was applied to all the variables to remove variability with frequencies lower than 1/7 per year58. Linear regression and correlation analysis were employed to evaluate the relationship between Arctic warming, atmospheric circulation, and SST anomalies. The boreal winter season in this study is defined as December, and the following January and February.

NE Pacific warm blob definition

To identify warm blob events, monthly SST data from the ERSST v5 dataset was utilized. Warm blob events were defined when the normalized SST values exceeding the 90th percentile threshold derived from long-term climatology for a duration of at least 2 months, as adapted from Hobday et al. 59. The 90th percentile threshold was calculated monthly using SST data spanning from 1979 to 2022.

Model simulation

In this study, we employed the CAM5, developed by the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR), to investigate the teleconnection among winter SAT in the Arctic region, geopotential height and wind fields. CAM5 utilized a finite-volume dynamical core with a global horizontal resolution of approximately 2° (F19). The lower boundary heat and moisture fluxes were determined using the thermodynamic module of the Community Land Model and the Community Sea-Ice Model. To capture the variability, we conducted a transient experiment using CAM5 driven by observed monthly-averaged SST and SIC variability in the Arctic region (north of 65°N) during the period 1979–2021. Twelve ensembles with different perturbed initial conditions were conducted, and each ensemble was driven by the observed SST and SIC variability over the Arctic region, with a buffer zone of 10° set at the southern boundary. SST and SIC values outside the Arctic region were set to the climatological average for the period 1981–2010. Greenhouse gas concentrations, aerosols, and solar radiation remained fixed throughout the study period. To evaluate the influence of Arctic warming on the atmospheric circulation, the ensemble mean was calculated from 1979 to 2021. To evaluate the role of the tropical forcing (Supplementary Fig. 7b), another experiment was conducted with monthly-averaged SST variability in the tropical Pacific region. However, CAM5, being an atmospheric model, lacks global coupling with other components such as the ocean and land, potentially limiting its ability to simulate the complex interactions within the global climate system.

Additionally, we also used monthly data outputs from 34 CMIP6 models in the historical run (1979–2014) in the present study, as outlined in Supplementary Table 1. For each CMIP6 model, we used only one ensemble member, namely the “r1i1p1f1” ensemble member. It’s worth noting that the data coverage of CMIP6 historical simulations spanned from 1979 to 2014, which doesn’t completely align with the observational period (1979–2022), potentially impacting the consistency and reliability of the simulation results.

Ocean mixed layer heat budget

To investigate the mechanisms underlying the formation of the warm SST anomalies, an analysis of the heat budget within the ocean ML was employed1,17,60. This approach examines the average temperature changes within the ML by considering various physical processes, including horizontal advection, air-sea surface heat fluxes, and the entrainment of water that transfers heat into the ML. The temperature tendency within the ML can be described using the following equation61:

Here, T represents the mean temperature within the ML and \(\frac{\partial T}{\partial t}\) indicates the rate of change of SST anomalies over time. Q denotes the net surface heat flux, while ρ and Cp represent the reference density and specific heat of seawater, respectively (\({\rho }{C}_{p}=4.088\times {10}^{6}{\rm{J}}\,\cdot\,\) °C−1 · m−3). The parameter \({h}\) denotes the depth of ML, \({u}_{a}\) represents the ocean current velocity, \({w}_{h}\) is the vertical velocity, \({T}_{h}\) represents the temperature at the bottom of the ML, \(\kappa\) denotes the diffusivity constant, and z represents the depth. The second term on the right-hand side of the equation accounts for horizontal advection. The third and fourth terms, collectively referred to as the residuals, which are obtained by subtracting the first and second terms on the right-hand side from the ML temperature tendency.

Data availability

All data are available in the main text or the supplementary materials are available from publicly accessible depositories. The ERA5 reanalysis data obtained from the ECMWF are available at cds.climate.copernicus.eu. The SAT from HadCRUT5 and SST from HadISST are available at https://www.metoffice.gov.uk/hadobs/hadcrut5/ and https://www.metoffice.gov.uk/hadobs/hadisst2/, respectively. The SST data obtained from ERSST v5 is available at https://psl.noaa.gov/data/gridded/data.noaa.ersst.v5.html. The GODAS ocean reanalysis data provided by the NOAA PSL is available at: psl.noaa.gov/data/gridded/data.godas.html. CMIP6 simulations from 34 Earth System Models for historical (1979–2014) run shown in Supplementary Table 1 are obtained from https://esgf-node.llnl.gov/projects/cmip6/.

Code availability

The codes used in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Bond, N. A., Cronin, M. F., Freeland, H. & Mantua, N. Causes and impacts of the 2014 warm anomaly in the NE Pacific. Geophys. Res. Lett. 42, 3414–3420 (2015).

Amaya, D. J., Bond, N. E., Miller, A. J. & Deflorio, M. J. The evolution and known atmospheric forcing mechanisms behind the 2013–2015 North Pacific warm anomalies. US CLIVAR Var. 14, 1–6 (2016).

Di Lorenzo, E. & Mantua, N. Multi-year persistence of the 2014/15 North Pacific marine heatwave. Nat. Clim. Change 6, 1042–1047 (2016).

Gentemann, C. L., Fewings, M. R. & García-Reyes, M. Satellite sea surface temperatures along the West Coast of the United States during the 2014–2016 northeast Pacific marine heat wave. Geophys. Res. Lett. 44, 312–319 (2017).

Whitney, F. A. Anomalous winter winds decrease 2014 transition zone productivity in the NE Pacific. Geophys. Res. Lett. 42, 428–431 (2015).

McCabe, R. M. et al. An unprecedented coastwide toxic algal bloom linked to anomalous ocean conditions. Geophys. Res. Lett. 43, 10366–10376 (2016).

Peterson, W., Robert M., & Bond N. The warm blob-Conditions in the northeastern Pacific Ocean. PICES Press, 23, 36–38 (2015).

Zaba, K. D. & Rudnick, D. L. The 2014–2015 warming anomaly in the Southern California current system observed by underwater gliders. Geophys. Res. Lett. 43, 1241–1248 (2016).

Walsh, J. E. et al. The exceptionally warm winter of 2015/16 in Alaska. J. Clim. 30, 2069–2088 (2017).

Hartmann, D. L. Pacific sea surface temperature and the winter of 2014. Geophys. Res. Lett. 42, 1894–1902 (2015).

Hu, Z. Z., Kumar, A., Jha, B., Zhu, J. & Huang, B. Persistence and predictions of the remarkable warm anomaly in the northeastern Pacific Ocean during 2014–16. J. Clim. 30, 689–702 (2017).

Seager, R. et al. Causes of the 2011–14 California drought. J. Clim. 28, 6997–7024 (2015).

Swain, D. L. et al. Remote linkages to anomalous winter atmospheric ridging over the northeastern Pacific. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 122, 12194–12209 (2017).

Swain, D. L. et al. The extraordinary California drought of 2013/2014: Character, context, and the role of climate change. Bull. Am. Meterol. Soc. 95, S3–S7 (2014).

Wang, S. Y., Hipps, L., Gillies, R. R. & Yoon, J. H. Probable causes of the abnormal ridge accompanying the 2013–2014 California drought: ENSO precursor and anthropogenic warming footprint. Geophys. Res. Lett. 41, 3220–3226 (2014).

Trenberth, K. E. & Hurrell, J. W. Decadal atmosphere-ocean variations in the Pacific. Clim. Dyn. 9, 303–319 (1994).

Chen, H. H. et al. Combined oceanic and atmospheric forcing of the 2013/14 marine heatwave in the northeast Pacific. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 6, 3 (2023).

Lee, M. Y., Hong, C. C. & Hsu, H. H. Compounding effects of warm sea surface temperature and reduced sea ice on the extreme circulation over the extratropical North Pacific and North America during the 2013–2014 boreal winter. Geophys. Res. Lett. 42, 1612–1618 (2015).

Shi, J. et al. Northeast Pacific warm blobs sustained via extratropical atmospheric teleconnections. Nat. Commun. 15, 2832 (2024).

Screen, J. & Simmonds, I. The central role of diminishing sea ice in recent Arctic temperature amplification. Nature 464, 1334–1337 (2010).

Serreze, M. & Barry, R. Processes and impacts of Arctic amplification: a research synthesis. Glob. Planet. Change 77, 85–96 (2011).

Cohen, J. et al. Recent Arctic amplification and extreme mid-latitude weather. Nat. Geosci. 7, 627–637 (2014).

Cohen, J. et al. Divergent consensuses on Arctic amplification influence on midlatitude severe winter weather. Nat. Clim. Change 10, 20–29 (2020).

Kug, J. S. et al. Two distinct influences of Arctic warming on cold winters over North America and East Asia. Nat. Geosci. 8, 759–762 (2015).

Overland, J. et al. The melting Arctic and midlatitude weather patterns: are they connected? J. Clim. 28, 7917–7932 (2015).

Overland, J. E. et al. Nonlinear response of mid-latitude weather to the changing Arctic. Nat. Clim. Change 6, 992–999 (2016).

Cvijanovic, I. et al. Future loss of Arctic sea-ice cover could drive a substantial decrease in California’s rainfall. Nat. Commun. 8, 1947 (2017).

Lund, J., Medellin-Azuara, J., Durand, J. & Stone, K. Lessons from California’s 2012–2016 drought. J. Water Resour. Plan. Manag. 144, 04018067 (2018).

Rogers, J. C. The North Pacific Oscillation. J. Clim. 1, 39–57 (1981).

Song, S. Y., Yeh, S. W., Kim, H. & Holbrook, N. J. Arctic warming contributes to increase in Northeast Pacific marine heatwave days over the past decades. Commun. Earth Environ. 4, 25 (2023).

Amaya, D. J., Miller, A. J., Xie, S. P. & Kosaka, Y. Physical drivers of the summer 2019 North Pacific marine heatwave. Nat. Commun. 11, 1903 (2020).

Barnston, A. G. & Livezey, R. E. Classification, seasonality, and persistence of low-frequency atmospheric circulation patterns. Mon. Weather Rev. 115, 1083–1126 (1987).

Liang, Y. C., Yu, J. Y., Saltzman, E. S. & Wang, F. Linking the tropical Northern Hemisphere pattern to the Pacific warm blob and Atlantic cold blob. J. Clim. 30, 9041–9057 (2017).

Mo, K. C. & Livezey, R. E. Tropical-extratropical geopotential height teleconnections during the Northern Hemisphere winter. Mon. Weather Rev. 114, 2488–2515 (1986).

Frankignoul, C., Sennéchael, N. & Cauchy, P. Observed atmospheric response to cold season sea ice variability in the Arctic. J. Clim. 27, 1243–1254 (2014).

Kennel, C. F. & Yulaeva, E. Influence of Arctic sea-ice variability on Pacific trade winds. P. Natl Acad. Sci. Usa. 117, 2824–2834 (2020).

McLeod, J. T., Ballinger, T. J. & Mote, T. L. Assessing the climatic and environmental impacts of mid-tropospheric anticyclones over Alaska. Int. J. Climatol. 38, 351–364 (2018).

Renwick, J. A. & Wallace, J. M. Relationships between North Pacific wintertime blocking, El Niño, and the PNA pattern. Mon. Weather Rev. 124, 2071–2076 (1996).

Kosaka, Y. & Xie, S. P. Recent global-warming hiatus tied to equatorial Pacific surface cooling. Nature 501, 403–407 (2013).

Ogi, M., Rysgaard, S. & Barber, D. G. Cold winter over North America: the influence of the East Atlantic (EA) and the tropical/Northern Hemisphere (TNH) teleconnection patterns. Open Atmos. Sci. J. 10, 6–13 (2016).

Baxter, S. & Nigam, S. Key role of the North Pacific Oscillation-West Pacific pattern in generating the extreme 2013/14 North American winter. J. Clim. 28, 8109–8117 (2015).

Liang, Y. C. The Changing Impacts of El Niño and Arctic Warming on Mid-latitude Climate Variability. University of California, Irvine (2018).

Wills, R. C. J., Dong, Y., Proistosecu, C., Armour, K. C. & Battisti, D. S. Systematic climate model biases in the large-scale patterns of recent sea-surface temperature and sea-level pressure change. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2022GL100011 (2022).

Hu, X. M., Ma, J. R., Ying, J., Cai, M. & Kong, Y. Q. Inferring future warming in the Arctic from the observed global warming trend and CMIP6 simulations. Adv. Clim. Chang. Res. 12, 499–507 (2021).

Seager, R. & Henderson, N. On the role of tropical ocean forcing of the persistent North American west coast ridge of winter 2013/14. J. Clim. 29, 8027–8049 (2016).

Holton, J. R. An introduction to dynamic meteorology. Am. J. Phys. 41, 752–754 (1973).

Takaya, K. & Nakamura, H. A formulation of a phase-independent wave-activity flux for stationary and migratory quasigeostrophic eddies on a zonally varying basic flow. J. Atmos. Sci. 58, 608–627 (2001).

Yu, J., Zou, Y., Kim, S. T. & Lee, T. The changing impact of El Niño on us winter temperatures. Geophys. Res. Lett. 39, L15702 (2012).

Yu, J. & Zou, Y. The enhanced drying effect of Central-Pacific El Niño on US winter. Environ. Res. Lett. 8, 014019 (2013).

Xie, J. & Zhang, M. Role of internal atmospheric variability in the 2015 extreme winter climate over the North American continent. Geophys. Res. Lett. 44, 2464–2471 (2017).

Deser, C. & Phillips, A. S. Simulation of the 1976/77 climate transition over the North Pacific: sensitivity to tropical forcing. J. Clim. 19, 6170–6180 (2006).

Lyon, B., Barnston, A. G. & DeWitt, D. G. Tropical pacific forcing of a 1998–1999 climate shift: observational analysis and climate model results for the boreal spring season. Clim. Dyn. 43, 893–909 (2013).

Morice, C. et al. An updated assessment of near-surface temperature change from 1850: the HadCRUT5 dataset. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 126, e2019JD032361 (2021).

Hersbach, H. et al. ERA5 monthly averaged data on pressure levels from 1940 to present. Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) Climate Data Store (CDS), (2023) (Accessed on 06-12-2023).

Rayner, N. A. et al. Global analyses of sea surface temperature, sea ice, and night marine air temperature since the late nineteenth century. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 108, 4407 (2003).

Huang, B. et al. Extended reconstructed Sea surface temperature, Version 5 (ERSSTv5): Upgrades, validations, and intercomparisons. J. Clim. 30, 8179–8205 (2017).

Behringer, D. W., & Xue, Y. Evaluation of the global ocean data assimilation system at NCEP: The Pacific Ocean. Eighth symposium on integrated observing and assimilation systems for atmosphere, Oceans, and Land Surface, AMS 84th Annual Meeting, Washington State Convention and Trade Center, Seattle, Washington, 11–15 (2004).

Duchon, C. E. Lanczos filtering in one and two dimensions. J. Appl. Meteorol. 18, 1016–1022 (1979).

Hobday, A. J. et al. A hierarchical approach to defining marine heatwaves. Prog. Oceanogr. 141, 227–238 (2016).

Benthuysen, J., Feng, M. & Zhong, L. Spatial patterns of warming off Western Australia during the 2011 Ningaloo Niño: Quantifying impacts of remote and local forcing. Cont. Shelf Res. 91, 232–246 (2014).

Cronin, M. F., Pelland, N. A., Emerson, S. R. & Crawford, W. R. Estimating diffusivity from the mixed layer heat and salt balances in the North Pacific. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 120, 7346–7362 (2015).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant No. 2023YFC2811800), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 42176013) and the Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation for Distinguished Young Scholar (Grant No. R25D060010).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.W. and F.C. led the scientific questions and designed the study. H.H.C. made the analysis and wrote the initial manuscript. X.L. conducted the numerical model and sensitivity experiments. L.W., Y.Y, Y.Y and C.H. reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, HH., Wang, Y., Li, X. et al. Arctic warming as a potential trigger for the warm blob in the northeast Pacific. npj Clim Atmos Sci 8, 111 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-00900-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-00900-9