Abstract

Anthropogenic aerosols could weaken the East Asian summer monsoon (EASM). This study investigated the regional effects of varying aerosol optical depth (AOD) on the EASM through qualitative and quantitative analyses for three subregions in eastern China. After assessing 38 CMIP6 models, four models (ACCESS-CM2, CanESM5, MIROC6, and MRI-ESM2-0) were selected for detailed analysis. Results showed that the weakening of EASM was predominantly attributed to anthropogenic aerosols. Increased AOD reduced land-sea temperature and pressure differences, weakening the EASM as indicated by the EASMI. Higher aerosol levels decreased surface shortwave radiation, land surface temperature, and evaporation, weakening the land-sea thermal contrast. Enhanced aerosol-induced cooling increased atmospheric stability and downward flow, suppressing upper air water vapor flux and precipitation. These findings underscore the critical role of anthropogenic aerosols in altering regional climate patterns and the importance of emission control to mitigate their effects on the EASM.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The East Asian monsoon is a critical component of both the Asian and global monsoon systems and influences the climate of a vast area covering eastern China, the Korean Peninsula, and Japan1,2,3. Located between the world’s largest continent (Eurasia) and the world’s largest ocean (the Pacific Ocean), East Asia experiences pronounced land‒sea temperature contrasts and seasonal variations4,5. As the most variable climate factor in the monsoon region, precipitation highlights the critical role of the East Asian summer monsoon (EASM) in influencing regional and global climate systems6,7,8,9. Given the significant impact of the EASM on regional climate variability, including its role in driving droughts and floods that severely affect agriculture and economies, investigating the variability and influencing factors of EASM intensity is highly important10,11.

In the latter half of the 20th century, the precipitation patterns across global monsoon regions were observed to have undergone notable changes, with the EASM clearly weakening12,13. This weakening is due to the reduction in low-level southwesterly winds, the southward shift of the subtropical jet stream, and the rise in sea level pressure14,15. Scholars have explored the mechanisms behind this weakening of the EASM. The increase in aerosols is believed to be an important factor in this trend16,17,18,19,20. Other studies have suggested that the weakening of the EASM may be a response to global warming driven by increasing greenhouse gases21,22. In addition, internal variability in the climate system such as multidecadal oscillation, is also considered to be associated with the trends23,24,25. The complex interplay of internal climate dynamics and anthropogenic influences shaped the observed weakening of the EASM26,27. However, distinguishing the contributions of different factors remains a significant challenge due to their interdependent nature28.

Among the above factors, the spatiotemporal variability in aerosols is the greatest. Since the 1950s, East Asia has experienced a substantial increase in aerosol emissions due to rapid industrialization and economic development29,30. Aerosols can alter the radiation budget and further impact precipitation through both direct and indirect climate effects. Directly, aerosols scatter and absorb solar radiation, affecting the Earth’s energy balance31. Indirectly, they act as cloud condensation nuclei and ice nuclei, altering cloud properties and precipitation32,33. Among these, anthropogenic aerosols exert a particularly notable influence34,35,36,37. Recent studies38,39,40,41 have utilized observations or model simulations to investigate the influence of aerosols on the EASM. Observations revealed a correlation between changes in aerosol concentrations in eastern China and variations in precipitation patterns associated with the EASM, suggesting that aerosols contribute to the weakening of the EASM38,40,42. However, the observations could not isolate the specific impact of anthropogenic aerosols from other factors such as greenhouse gases and natural forcings. Numerical model simulations could compensate for this limitation. The GFDL CM3 model was applied to investigate the response of the EASM to various external forcings by comparing their effects on precipitation, with scenarios including greenhouse gases and ozone forcings only, anthropogenic aerosol forcings only, and natural forcings only39. The results indicate that the recent decrease in precipitation was attributed primarily to increased anthropogenic aerosol emissions, which induced an energy imbalance between the northern and southern hemispheres. It is worth noting that their accuracy and reasonability are influenced by uncertainties in parameterizations, resolution, and input data quality. To assess the uncertainties of different models, the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 5 (CMIP5) employed 67 models and a range of simulation scenarios43. The outputs of these models were analyzed using diverse methodologies and provided valuable insights into the impacts of anthropogenic aerosols on the EASM. Comparative analyses of the spatial patterns of precipitation under different external forcing scenarios have qualitatively highlighted the predominant role of anthropogenic aerosols in influencing the EASM41,44,45. Empirical orthogonal function (EOF) analysis was used to assess precipitation modes under various external forcings and confirmed the significant impact of anthropogenic aerosols46. The optimal fingerprint method had also been applied for detection and attribution analyses of the signals of different external forcings on the variability in the EASM47,48 and the results consistently revealed that the signal of anthropogenic aerosol forcing was the most prominent among all external factors.

Compared with CMIP5, CMIP6 offered more scenario experiments and, for the first time, included historical aerosol-only forcing experiments (hist-aer). Moreover, compared with CMIP5, CMIP6 demonstrated improved performance in simulating the precipitation of the EASM49,50. These enhanced features provided more accurate and detailed data for exploring the impact of external forcings on the EASM51. Currently, most studies primarily provided qualitative analyses of the physical mechanism of anthropogenic aerosol influence on the EASM, with little concentration of quantitative assessments. In this work, we utilized model simulation outputs of CMIP6 to conduct analyses of two main aspects: first, to quantify the impact of anthropogenic aerosols on the EASM in comparison to other external forcings; second, to elucidate the underlying physical mechanisms driving this effect and perform a quantitative assessment of its magnitude.

Results

CMIP6 model evaluation

To evaluate the performance of the CMIP6 models in simulating the EASM, we focused on the summer season (June–August) from 1975 to 2014. The precipitation data are sourced from CN05.1, and the study area is \((20^{\circ} {-}42^{\circ} N,105^{\circ} {-}120^{\circ} E)\). The observed values of the wind field are obtained from JRA-55 and the study area is \((20^{\circ} {-}42\,^{\circ} N,105^{\circ} {-}150\,^{\circ} E)\).

Figure 1a presents the Taylor diagram for precipitation, which illustrates the spatial correlation and standard deviation of the 38 CMIP6 models compared with the observation data. Most of the models exhibited correlation coefficients ranging from 0.14 to 0.9, reflecting strong agreement with the observed precipitation patterns. However, NorCPM1 had a low correlation coefficient of approximately 0.14, indicating significant discrepancies in precipitation patterns. Model ACCESS-ESM1-5 showed the highest standard deviation (>1.6), suggesting a significant overestimation of precipitation variability. Figure 1b shows the Taylor diagram for the 850 hPa wind field, where the correlation coefficients for the wind speed varied from 0.16 to 0.9. The correlation coefficient of MCM-UA-1-0 was only 0.16. Overall, most CMIP6 models demonstrated reasonable accuracy in simulating both precipitation and wind fields, although there were considerable variations in performance.

To further quantify the performance of the CMIP6 models, skill scores for both precipitation and wind fields were calculated and presented in Fig. 2. For precipitation, most of the models achieved skill scores greater than 0.7, indicating their ability to capture the essential characteristics of observed precipitation with reasonable accuracy. However, NorCPM1 had the lowest skill score of approximately 0.29 within the study region, suggesting limitations in its ability to simulate precipitation patterns accurately in this specific area. In contrast, MPI-ESM1-2-HR achieved the highest skill score of approximately 0.89 within the study region, indicating its excellent reliability for stimulating precipitation among the evaluated CMIP6 models. With respect to the wind field, 25 of the 38 models presented skill scores above 0.7. MCM-UA-1-0 recorded the lowest skill score at approximately 0.33, reflecting challenges in accurately simulating wind fields. Conversely, IITM-ESM achieved the highest skill score of approximately 0.91, indicating its robustness in simulating both precipitation and wind fields effectively. In conclusion, the skill scores corroborated the findings from the Taylor diagrams, indicating that MPI-ESM1-2-HR, NorESM2-MM and MRI-ESM2-0 are among the most reliable models for simulating the precipitation and wind fields. In contrast, models such as NorCPM1 and MCM-UA-1-0 exhibited lower performance in simulating precipitation and wind fields, and were not used for further analysis in this study.

Sensitivity analysis of the EASM to external forcing

Based on the evaluation performance, models with skill scores greater than 0.7 were considered. Meanwhile, owing to the availability of the relevant variables in output, four models—ACCESS-CM2, CanESM5, MIROC6, and MRI-ESM2-0—were selected for detailed analysis. Here, precipitation data from 1850 to 2014 under historical, hist-aer, hist-nat, and hist-GHG experiments were used, and the study area was \((20^{\circ} {-}42^{\circ} N,105^{\circ} {-}120^{\circ} E)\).

Figure 3 illustrates that all four models consistently showed a gradual decline in precipitation from 1850 to 2014 under ALL forcing, with a decreasing trend of approximately –0.6%/10a. The trend in precipitation under the AER forcing closely agrees with that under ALL forcing, whereas the trends under the NAT and GHG forcings exhibited the opposite behavior. The contribution of AER forcing (160% in the MME) to precipitation changes was significantly greater than those of other external forcings, i.e., -20% for GHG and -15% for NAT. The relative ratio of the contributions of the three forcings is approximately 32: (−4): (−3). These findings indicate that aerosols had a dominant effect on the observed decline in precipitation, whereas the GHG and NAT forcings contributed less significantly or acted to counterbalance the changes induced by anthropogenic aerosols. The reason may be that anthropogenic aerosols have a greater effect on atmospheric radiation52,53,54. This is consistent with previous studies55. Therefore, the mechanism of anthropogenic aerosol forcing on the EASM will be analyzed in detail in the following sections.

Influence mechanism of aerosol forcing on the EASM

Although the calculated AOD differed across the models, the general trend from 1950–2020 was consistent, characterized by an initial slow increase, followed by a period of rapid increase and later oscillation, and ultimately a sharp decline. Based on this feature and the AOD values, the period from 1950 to 2020 for each model was divided into three Levels (I, II, III). Additionally, the period from 1850 to 1949 was assigned as the reference Level (REF). It is worth noting that the MME in this study is represented by the average values corresponding to the four Levels.

Furthermore, the eastern region of China is divided into three subregions for analysis: South \((20^{\circ} {-}28^{\circ} N,\,105^{\circ} {-}120^\circ E)\), Mid \((28^{\circ} {-}33^{\circ} N,\,105^{\circ} {-}120^{\circ} E)\) and North \((33^{\circ} {-}42^{\circ} N,\,105^{\circ} {-}120^{\circ} E)\)24. This study aims to examine the impact of aerosol forcing on the EASM in these subregions.

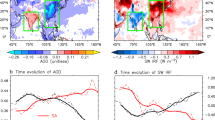

Analysis of the EASMI

The sea–land temperature difference and pressure difference are key causes of the EASM. Fig. 4 illustrates the sea–land thermal contrast and sea–land pressure difference, as well as the EASMI across four Levels across East Asia.

According to Fig. 4, both the west–east and north–south sea–land temperature differences decreased progressively from Level REF to III. Specifically, the west–east sea–land temperature difference decreased by 0.65 °C, while the north-south sea-land temperature difference decreased by 0.31 °C. This reduction in the temperature difference implies a diminished contrast between the thermal properties of the sea and land, leading to a decrease in the driving force behind the monsoon, and thus a weakening EASM.

Similarly, the sea–land pressure differences showed a corresponding decline. The west–east sea–land pressure difference decreased by 0.82 hPa, and the north–south sea–land pressure difference decreased by 0.44 hPa from Level REF to III. This reduction in pressure difference indicates a decrease in the kinetic energy of atmospheric circulation, further contributing to the weakening of the monsoon system.

Moreover, the EASMI showed a gradual decline over the Levels, shifting from a positive value of 0.12 in REF to a negative value of −0.30 in III. This decrease reinforces that the EASM gradually weakens over the Levels, driven by the reduced thermal and pressure contrasts between the sea and land.

The influence of aerosols on the weakening of the EASM is further discussed in the following sections.

Variations of surface climatic variables for four Levels

To investigate the impact of anthropogenic aerosols on the EASM, the spatial distributions of AOD together with surface climatic variables Rsd, Tm, E, P, and Pr for Level REF and their differences between three levels and REF are presented in Fig. 5. The spatial averages for AOD and surface climatic variables are then calculated for the three regions in the four levels and shown in Fig. 6.

a Aerosol Optical Depth (AOD); b Surface solar radiation (Rsd, unit: W/m2); c Maximum surface temperature (Tm, unit: ° C); d Evaporation (E, unit: mm/day); e 850 hPa wind vectors (uv, unit: m/s) and pressure (P, shading, unit: hPa); (f) Precipitation (Pr, unit: mm/day). The first column is REF, and the second to fourth columns show the difference between Level I, II, III and REF, respectively.

The AOD in the three regions increased progressively across the four Levels. Specifically, the AOD in the South increased by 0.38 from Level REF to III, whereas that in the Mid experienced the largest increase of 0.55, and the AOD in the North increased by 0.42 (Figs. 5a, 6a). An increase in AOD enhances the scattering and absorption of the atmosphere, leading to a gradual reduction in the shortwave radiation reaching the surface. The shortwave radiation in the three regions decreased from Level REF to III by 20.4 W/m2, 27.8 W/m2 and 21.1 W /m2 for the South, Mid, and North, respectively, and the shortwave radiation in the Mid region decreased most obviously (Figs. 5b, 6a). The radiative cooling effect of aerosols results in a gradual decrease in the daily maximum surface air temperature. The most significant decrease occurred in the Mid, with a reduction of 1.3 °C, whereas the South and North experienced decreases of 0.9 °C and 1.2 °C, respectively (Figs. 5c, 6b). The radiative cooling effect of aerosols stabilizes the atmosphere, which may inhibit evaporation and precipitation or change the location of precipitation belts56,57.

The temperature decreases in the above three regions significantly suppressed evaporation, leading to a decrease of 0.43 mm/day, 0.51 mm/day, and 0.34 mm/day in the South, Mid, and North regions, respectively (Figs. 5d, 6c). This reduction in evaporation diminished the supply of water vapor, directly impacting precipitation formation. Notably, a decrease in temperature usually leads to an increase in air pressure, which in this paper rise by 0.41 hPa, 0.75 hPa, and 0.66 hPa in the respective regions from Level REF to III. This pressure increase helped the development of an anomalous anticyclone over the eastern Chinese mainland, leading to a weakening of the south wind component in the EASM system (Figs. 5e, 6b).

Another of the most direct manifestations of the weakening EASM is the change in precipitation over East Asia. As shown in Figs. 5f and 6c, the precipitation in the three regions gradually decreased as the Level increased. From Level REF to III, precipitation decreased by 0.88 mm/day, 0.90 mm/day, and 0.43 mm/day in the South, Mid, and North, respectively. The reduction in the North was notably smaller than those in the Mid and South, which is probably associated with the main source of moisture in the North and will be discussed in detail in the next section. Additionally, the increase in AOD from Level II to III was greater than that from Level I to II, whereas the reduction in precipitation was less pronounced in Level II to III compared to Level I to II. This may be caused by the second indirect effect of aerosols on climate, i.e., too many aerosol particles may compete for limited moisture, prolong the cloud lifetime and suppress precipitation, which is called the lifetime effect33. Therefore, both the direct and indirect effects of aerosols on climate play important roles in the EASM.

In summary, the results from Figs. 5 and 6 indicate that the increase in AOD, along with its associated cooling effects, significantly reduced surface shortwave radiation, temperature, evaporation, and ultimately precipitation across all three regions. These changes reflect a weakened monsoon and underscore the substantial influence of anthropogenic aerosols on the EASM.

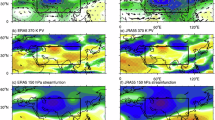

Variations of upper air climatic variables for four Levels

Fig. 7 and Fig. 8 illustrate the spatial distribution of the whole-layer water vapor flux, including the latitudinal and meridional components, as well as the water vapor flux divergence across different Levels.

As shown in Figs. 7 and 8a, for the South, at Level REF the water vapor flux was the largest, and the divergence of the water vapor flux was the strongest convergence. The two variables gradually weakened with the progress of the levels, and the decrease in water vapor flux was 16 kg/(m·s) from Level REF to III, and the meridional water vapor flux played a leading role in the decrease in water vapor flux. This finding indicates that in this region, the inhibition effect of increasing aerosol on water vapor flux gradually increases, thus weakening precipitation. The primary source of water vapor in this region originated from the southwest, driven largely by the monsoon, which transported substantial amounts of moisture from the South China Sea and the western Pacific Ocean. Additionally, due to the proximity of the southern region to the equator, it was also influenced by tropical monsoons and convection58.

In the Mid, the trend of water vapor flux was similar to that in the South, with a reduction of 10 kg/(m·s) from Level REF to III (Figs. 7 and 8b). The water vapor flux divergence also shows an overall weakening trend of convergence, although in the period from Level REF to I the trend of convergence increased by 0.06×10–-5 kg/(m2·s). Aerosols gradually shrank the convergence area in this region, leading to reduced precipitation. The anomaly observed between Level REF and I may be attributed to the influence of clouds following the Meiyu season, as confirmed by Fig. 9. The reduction in water vapor flux results in a decrease in the cloud liquid water content formed from evaporative condensation, and more aerosols imply more cloud condensation nuclei, thus, the cloud droplet radius decreases, thereby the decreasing cloud precipitation efficiency which is consistent with the Twomey effect59,60,61. Consequently, the increased water vapor inflow due to the decrease in water vapor flux divergence from Level REF to I may not translate into effective precipitation. This effect may be particularly pronounced in July and August, when the impact of aerosols on clouds becomes more pronounced after the rainy season has ended. The main sources of water vapor in this region were generally from the southwest, meaning that it was influenced by both the western Pacific subtropical high and southern airflows.

For the North, the water vapor flux also gradually decreased with a trend of −4 kg/(m·s) (Figs. 7 and 8c). Unlike in the South, the change in latitudinal water vapor flux played a leading role in the decrease in water vapor flux in the North. Additionally, in contrast to those in the Mid and South, the water vapor flux in the North exhibited divergence rather than convergence. The divergence from Level REF to II decreased, indicating that increased aerosol concentrations might be related to reduced dispersion of water vapor in the Northern region. This pattern may be attributed to the pronounced atmospheric stability prevalent in the North, where water vapor tends to accumulate in the lower troposphere without resulting in significant precipitation. However, this stability increases the likelihood of extreme strong precipitation events62. The primary source of water vapor in this region was from the northwest, indicating that the North was influenced mainly by the midlatitude westerly jet stream, resulting in relatively limited water vapor sources.

In addition to water vapor flux, the vertical wind field and vertical temperature field are critical upper-air climatic variables influencing the EASM. Variations in these vertical fields are directly linked to atmospheric stability, thereby exerting a significant impact on precipitation.

As shown in Fig. 10, with increasing AOD, the temperature field shows an overall cooling trend. This cooling is particularly pronounced in the middle and lower troposphere (approximately 850 hPa−300 hPa), especially between 35°N and 45°N (Fig. 10a, d). This cooling effect is likely due to the direct radiative influence of aerosols, which reduces surface and near-surface atmospheric temperatures. Furthermore, at lower atmospheric levels, the wind field demonstrated increased subsidence between 20°N and 42°N (Fig. 10e–g). This pattern is consistent with the observed temperature decrease, suggesting that aerosols may enhance atmospheric stability by altering the radiation budget. Consequently, the upward movement of air is inhibited, leading to a reduction in precipitation.

Discussion

This study investigated the impact of anthropogenic aerosols on the EASM using both qualitative and quantitative analyses across three regions in Eastern China (South, Mid, and North). Considering the differences among the models, to increase the reliability of the findings, we first evaluated the ability of 38 CMIP6 models to simulate the EASM. Most models reasonably simulated EASM, and four models—ACCESS-CM2, CanESM5, MIROC6, and MRI-ESM2-0—were selected for further analysis due to their strong performance and availability of relevant output data.

Our investigation focuses on two key aspects. First, we conducted a sensitivity analysis to quantify the impact of anthropogenic aerosols in comparison with other external forcing factors. The results indicate that anthropogenic aerosols had the most significant impact on precipitation, with a contribution of approximately 160%, far exceeding those of greenhouse gases and natural forcings. This highlights the dominant role of anthropogenic aerosols in weakening the EASM.

Second, we tried to elucidate the underlying physical mechanisms for this effect based on quantitative analyses of the surface and upper air climatic variables. The increase in AOD enhanced atmospheric scattering and absorption, reducing surface shortwave radiation and air temperature and leading to decreased evaporation and water vapor flux. This reduction in water vapor supply, along with increased atmospheric stability, suppressed convective activity, ultimately contributing to the decline in precipitation. The overall weakening of the EASM was reflected in the decrease in sea−land temperature and pressure differences. Moreover, the Twomey effect might also play an important role in the low level of AOD in the Mid region. Therefore, the increase in anthropogenic aerosols is a significant factor contributing to the weakening of the EASM and emission control undoubtedly helps enhance the EASM and regional precipitation.

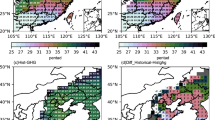

As described above, with increasing AOD, summer precipitation decreased in eastern China. This is based on the simulation results from the hist-aer experiment of CMIP6 in which only anthropogenic aerosol emission variations were considered. Is this true for observations with both natural and anthropogenic forcings? The summer precipitation and AOD data from the reanalysis databases from 1980 − 2020 were analyzed, i.e., using monthly mean data of MERRA-2 AOD and CN05.1 precipitation. Based on the variation trend and the values of AOD, the period from 1980 − 2020 was divided into two phases, low AOD (with a spatial mean of 0.22) and high AOD (with a spatial mean of 0.35). Figure 11 shows the precipitation across three regions in eastern China during the two phases. It is evident that with increasing AOD, the precipitation decreased in all three regions: in the North, the precipitation decreased from 3.43 to 3.23 mm/day; in the Mid, it decreased from 6.26 to 6.01 mm/day; and in the South, it decreased from 7.23 to 7.05 mm/day. The decrease in precipitation in the Mid region was 0.25 mm/day, which was the greatest of the three regions. However, the model simulations from CMIP6 revealed that the AOD for the same period was greater than that from the reanalysis, i.e., 0.27 and 0.46 for low and high AOD phases, respectively. The precipitation variations were calculated as from 2.93 to 2.87 mm/day in the North, from 5.18 to 5.05 mm/day in the Mid, and from 8.69 to 8.66 mm/day in the South, with the largest decrease of 0.13 mm/day occurring in the Mid which was almost half that from the model simulations. This might be caused by other anthropogenic and natural forcings and model uncertainties. The discussion and results represent only the overall trends across precipitation types, and in fact the effects of aerosols may differ significantly depending on specific precipitation types. For instance, Su et al. found that in recent 55 years in China, light precipitation decreased, while heavy precipitation changed differently in different regions20. Similarly, Yang et al. studied the impact of aerosols on tropical cyclone-induced precipitation over the mainland China. They found that aerosols enhanced heavy precipitation events while reduced initial light precipitation63. These studies suggest that the relationship between aerosols and precipitation is complex and different for various types of precipitation.

Aerosols can be categorized as absorbing aerosols or scattering aerosols, with each type exerting different effects on precipitation64. While this study confirms that anthropogenic aerosols generally suppress precipitation in eastern China, the detailed effects differ depending on the types of aerosols and are not analyzed in our work. Absorptive aerosols located below clouds cool the surface but warm the atmosphere, increasing atmospheric instability and, ultimately, enhancing precipitation and convection65,66. In contrast, scattering aerosols typically have the opposite effect67. Additionally, aerosol emissions from other regions may also influence precipitation in the East Asian monsoon region68.

The results of this study illustrate the importance of controlling aerosol emissions for regional climate, especially precipitation patterns. It is important to note that the rankings of the models in terms of their skill scores are based on their performance within the study region and may not necessarily reflect their global performance. Further analysis would be required to assess the models’ capabilities on a global scale. Furthermore, this work focused primarily on historical scenarios and did not explore future changes. In the future, as greenhouse gas emissions rise and aerosol emissions decline, global temperatures are expected to increase, which will likely have a significant impact on global precipitation patterns69,70,71,72. This change will likely lead to more precipitation in East Asia73,74. Predicting future changes of the EASM is very important for the government in the formulation of relevant disaster reduction policies and the sustainable development of society.

Methods

Observation and reanalysis data

Three datasets are taken as reference data to evaluate the ability of the CMIP6 models to simulate the EASM:

(1) JRA-55: Monthly mean wind field data provided by the Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA) with a horizontal resolution of 1.25°×1.25°, covering the period from 1958 to the present75 (https://jra.kishou.go.jp/JRA-55/). JRA-55 represents a significant advancement over JRA-25, addressing key issues such as the cold bias in the lower stratosphere through enhanced radiation schemes and data handling. The wind data from JRA-55 exhibits the highest spatial correlation in China, reaching up to 0.75, compared to the wind data from ERA5 and NCEP76. The wind value of JRA-55 has a negative deviation from the observed value. Despite certain flaws, JRA-55 remains a valuable tool for climate analysis, with ongoing efforts to refine observational datasets and model parameters for future enhancements77.

(2) CN05.1: A monthly precipitation dataset provided by the National Meteorological Information Center of China, covering the period 1961-2020, with a horizontal resolution of 0.25°×0.25°. The dataset was constructed by calculating grid climatology and interpolating station observations from approximately 2400 meteorological stations in China, with daily anomalies integrated78. It exhibits high spatial resolution and temporal continuity, providing consistent time series and spatial distribution. The correlation between the CN05.1 precipitation dataset and the EA05 and APHRO precipitation datasets reached 0.92 and 0.87, respectively. However, precipitation values are generally higher at high altitudes. This is due to the fact that most observation stations are located in plains or river valley zones, necessitating corrections for the interpolated values at high mountain grid points around the edges. The revised system employs a uniform value across the entire application area. In our work, we focus on the eastern China region, with few high-altitude mountains. Therefore, the precipitation in eastern China is hardly influenced.

(3) MERRA-2: The latest reanalysis project by NASA’s Global Modeling and Assimilation Office (GMAO) uses the Goddard Earth Observing System, Version 5 (GEOS-5), integrated with the Goddard Chemistry Aerosol Radiation and Transport (GOCART) aerosol module and aerosol measurements from various sources, with a horizontal resolution of 0.5°×0.625°, covering the period from 1980 to the present79. MERRA-2 represents a significant advancement over MERRA-1, incorporating an upgraded GEOS-5 data assimilation system and advanced satellite observations, which enhance the accuracy of atmospheric variable. In China, the correlation between AOD of MERRA-2 and AOD of AERONET sites is 0.92 in summer. However, in general, the AOD values of MERRA-2 is lower than those of AERONET. This discrepancy may be attributed to potential biases and limitations inherent in the model80,81,82.

CMIP6 model simulations

The monthly mean 850 hPa wind field (u, v) and precipitation (pr) data of 38 CMIP6 models were selected for evaluation before analysis of the effects of anthropogenic aerosols on the EASM83. The basic information of the relevant models is shown in Table S1 (see https://esgf-node.llnl.gov/projects/cmip6/ for more information). The study period is from June to August of 1975 to 2014.

To determine the influence of external forcings on the precipitation of the EASM, data from historical simulations of various forcing scenarios were employed. Specifically, the data include monthly mean precipitation (pr) data from the following simulations: historical all forcing (historical, ALL), historical aerosol only forcing (hist-aer, AER), historical greenhouse gas only forcing (hist-GHG, GHG), and historical natural only forcing (hist-nat, NAT). The time range for these data extends from June–August, covering the years 1850–2014.

To quantify the impact of anthropogenic aerosol forcing on the EASM, outputs from the hist-aer were analyzed. These outputs include aerosol optical depth (AOD), downward shortwave radiation (Rsd), maximum surface temperature (Tm), evaporation (E), sea level pressure (P), wind fields (u, v), precipitation (Pr), specific humidity, vertical velocity, and air temperature. The data period for this analysis is from June to August, spanning from 1850 to 2020.

Taylor diagram

To quantitatively evaluate the performance of the CMIP6 models in simulating the EASM, we employed a Taylor diagram as a key diagnostic tool. The Taylor diagram is particularly effective for summarizing multiple aspects of model performance, including the spatial correlation, root mean square error (RMSE), and standard deviation of the model outputs relative to the observation84. By presenting these metrics within a single plot, the Taylor diagram is used to comprehensively assess the model’s ability to simulate EASM patterns. The corresponding formulae are as follows:

where, \({E}^{{\prime} }\) represents the root-mean-square error, reflecting the degree of discrepancy between the variables \(m\) and \(M\). \({\sigma }_{m}\) and \({\sigma }_{M}\) are the standard deviations of \(m\) and \(M\), respectively, and their ratio constitutes the normalized standard deviation. \(R\) is the correlation coefficient between the observed value and the model, and \(\left|R\right|\) is more correlated as it approaches 1. \(N\) represents the total number of models adopted, \({m}_{n}\) and \({M}_{n}\) represent the model and observed values, respectively, and \(\bar{m}\) and \(\bar{M}\) are their respective means. In short, the closer the values of \(\left|R\right|\) are to 1 and the values of \({E}^{{\prime} }\) are to 0, the better the model’s performance.

The skill score is another important metric derived from these statistics (Eq.4). This score provides a single metric that encapsulates model performance, where a higher score indicates better performance.

Using the Taylor diagram, we can visually and quantitatively compare the performance of 38 CMIP6 models, thereby identifying which models most accurately capture the essential features of the EASM. This analysis is crucial for understanding the strengths and weaknesses of different models and for selecting the most reliable models for further climate studies. It will be used in Section 2.1.

Sensitivity analysis

To qualitatively and quantitatively evaluate the impacts of various external forcings on the EASM, we first examined the annual precipitation anomalies under different scenarios, and the calculation formula is as follows:

In this equation, \({pr}\) is the average precipitation in the study area in a certain year, and \({{pr}}_{{pre}-{industrial}}\) is the average precipitation in the study area before the Industrial Revolution.

To capture the variation trends of precipitation for different scenarios, \({Sen}{\prime} s\,{slope}\) is applied in this study85. It is widely used because of its excellence in nonlinear analysis and sensitivity to outliers. For the time series of annual precipitation anomalies \(X=\left({x}_{1},{x}_{2},\ldots ,{x}_{n}\right)\), the specific calculation method is as follows:

Here, “\({Medium}\)” is the median function, which represents the median of the slopes between different points in a dataset. Specifically, for each pair of points \({x}_{j}\) and \({x}_{i}\), where \({j}\, >\, i\), the slope between these two points is calculated as \(\frac{{x}_{j}-{x}_{i}}{j-i}\). The overall trend is then defined as the median of all such slopes, which provides a robust measure of the general trend in the data, minimizing the influence of outliers.

In CMIP6, the primary external forcings include anthropogenic aerosols, greenhouse gases, and natural forcings86. The historical trend in annual precipitation is understood to result from the cumulative effects of these three key forcings. Therefore, the precipitation trend in the historical forcing scenario is expressed as follows:

where \({{Trend}}_{h{ist}},\,{{Trend}}_{{aer}},\,{{Trend}}_{{GHG}},\,{{Trend}}_{{nat}}\) are the precipitation trends of historical, hist-aer, hist-GHG and hist-nat, respectively. The nonlinear interaction among the three external forcings87 is expressed as \({{Trend}}_{\mathrm{int}}\). The relative contribution of each forcing to the long-term trend in precipitation is as follows:

where \(i={aer},\,{GHG},\,{nat},\,\mathrm{int}\), and \({C}_{i}\) are the relative contributions caused by the specific forcings. A positive (negative) value means that external forcing has a positive (negative) contribution to the overall trend of precipitation88.

This method is applied in Section 2.2 to analyze the contributions of different external forcings to the EASM.

East Asian summer monsoon index

To quantify the intensity of the EASM and investigate the variations in temperature and pressure differences between land and sea, we utilized the East Asian summer monsoon index (EASMI).

Twenty five expressions of the EASMI were scored using multivariate empirical orthogonal function (MV-EOF) analysis89, and the EASMI formula proposed by Li and Zeng90 is selected here in this paper based on its reliability and excellent performance in capturing monsoon dynamics, which is defined for the summer period (June–August, JJA) in the region \((10^{\circ} {-}40^{\circ} N,110^{\circ} {-}140^{\circ} E)\). The index was calculated using the area-averaged vector wind data at 850 hPa:

where \({\bar{V}}_{1}\) represents the climatological mean wind vector for January, which is calculated by averaging the wind fields over multiple years for January at a given location, \({V}_{i}\) represents the actual wind vector for a specific year and month, typically June, July, or August, and \(\bar{V}\) is the mean of the climatological wind vectors for January and July. The norm \({||}V{||}\) is \({||}V{||}={\left({\iint }_{S}{|V|}^{2}dS\right)}^{1/2}\), where S indicates the integral field.

In addition, to calculate the sea–land thermal difference and sea–land pressure difference in the East Asian monsoon region, the definitions proposed by Sun et al. were also adopted in this paper91:

The difference between ground temperature (tas) in the East Asian monsoon \((27 \sim 35^{\circ} N,105 \sim 120^{\circ} E)\) and sea surface temperature (SST) (tos) in the subtropical Northwest Pacific \((15^{\circ} {-}30^{\circ} N,120^{\circ} {-}150^{\circ} E)\) represents the west–east (WE) thermal difference. The difference in ground temperature (tas) in South China \((20^{\circ} {-}27^{\circ} N,105^{\circ} {-}120^{\circ} E)\) and SST (tos) in the South China Sea \((5^{\circ} {-}18^{\circ} N,105^{\circ} {-}120^{\circ} E)\) is used to represent the north-south (NS) sea–land thermal difference. The corresponding sea level pressures between the same regions are used to represent the WE and NS pressure contrasts. These indices provide insights into the dynamic interactions between the atmosphere and ocean, which are crucial for understanding monsoon behavior.

Data availability

The Phase 6 of Coupled Model Intercomparison Project (CMIP6) model simulations can be obtained via the Earth System Grid Federation (ESGF) nodes, https://esgf-node.llnl.gov/search/cmip6/. The Japanese 55-year Reanalysis (JRA-55) are publicly available from https://jra.kishou.go.jp/JRA-55/. The MERRA-2 AOD products were provided by GES-DISC (Goddard Earth Science Data and Information Services Center, https://disc.gsfc.nasa.gov/). The CN05.1 can be obtained by contacting the author according to the corresponding requirements.

Code availability

All codes will be available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Kim, W. et al. Decadal Changes in Climatological Intraseasonal Fluctuation of Subseasonal Evolution of Summer Precipitation over the Korean Peninsula in the mid-1990s. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 28, 591–600 (2011).

Zhang, R. Changes in East Asian summer monsoon and summer rainfall over eastern China during recent decades. Sci. Bull. 60, 1222–1224 (2015).

Kurita, N. et al. East Asian Monsoon controls on the inter-annual variability in precipitation isotope ratio in Japan. Clim. 11, 339–353 (2015).

Zhu, K. Monsoons in Southeast Asia and rainfall amount in China. Acta Geologica Sin. 1, 1–27+197 (1934).

Zhu, B. & Song, Z. A review of the general circulation over eastern Asia in summer. Chin. J. Atmos. Sci. 3, 219–226 (1979).

Prell, W. L. & Kutzbach, J. E. Monsoon variability over the past 150,000 years. J. Geophys. Res. 92, 8411–8425 (1987).

Fu, C. & Wen, G. Variation of Ecosystems over East Asia in Association with Seasonal, Interannual and Decadal Monsoon Climate Variability. Clim. Change 43, 477–494 (1999).

Lei, Y., Hoskins, B. & Slingo, J. Exploring the Interplay between Natural Decadal Variability and Anthropogenic Climate Change in Summer Rainfall over China. Part I: Observational Evidence. J. Clim. 24, 4584–4599 (2011).

Shi, F. et al. Interdecadal to Multidecadal Variability of East Asian Summer Monsoon Over the Past Half Millennium. J. Geophys. Res.: Atmos. 127, 1–21 (2022).

Tao, F. et al. Variability in climatology and agricultural production in China in association with the East Asian summer monsoon and El Niño Southern Oscillation. Clim. Res. 28, 23–30 (2004).

Krishnan, R. et al. Deciphering the desiccation trend of the South Asian monsoon hydroclimate in a warming world. Clim. Dyn. 47, 1007–1027 (2016).

Wang, H. The weakening of the Asian monsoon circulation after the end of 1970’s. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 18, 376–386 (2001).

Wang, B. et al. Recent change of the global monsoon precipitation (1979–2008). Clim. Dyn. 39, 1123–1135 (2012).

Yu, R., Wang, B. & Zhou, T. Tropospheric cooling and summer monsoon weakening trend over East Asia. Geophys. Res. Lett. 31, 2004GL021270 (2004).

Yu, R. & Zhou, T. Seasonality and Three-Dimensional Structure of Interdecadal Change in the East Asian Monsoon. J. Clim. 20, 5344–5355 (2007).

Menon, S. et al. Climate Effects of Black Carbon Aerosols in China and India. Science 297, 2250–2253 (2002).

Qian, Y. et al. Regional climate effects of aerosols over China: modeling and observation. Tellus B: Chem. Phys. Meteorol. 55, 914 (2003).

Qian, Y. et al. Heavy pollution suppresses light rain in China: Observations and modeling. J. Geophys. Res.: Atmos. 114, 2008JD011575 (2009).

He, B. et al. Influences of external forcing changes on the summer cooling trend over East Asia. Clim. Change 117, 829–841 (2013).

Su, Y. et al. Spatiotemporal Variations of Precipitation in China Using Surface Gauge Observations from 1961 to 2016. Atmosphere 11, 303 (2020).

Uppala, S. M. et al. The ERA‐40 re‐analysis. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 131, 2961–3012 (2005).

Zhu, C. et al. Recent weakening of northern East Asian summer monsoon: A possible response to global warming. Geophys. Res. Lett. 39, 2012GL051155 (2012).

Yang, F. & Lau, K. M. Trend and variability of China precipitation in spring and summer: linkage to sea-surface temperatures. Int. J. Climatol. 24, 1625–1644 (2004).

Ding, Y., Wang, Z. & Sun, Y. Inter‐decadal variation of the summer precipitation in East China and its association with decreasing Asian summer monsoon. Part I: Observed evidences. Int. J. Climatol. 28, 1139–1161 (2008).

Li, H. et al. Responses of East Asian summer monsoon to historical SST and atmospheric forcing during 1950–2000. Clim. Dyn. 34, 501–514 (2010).

Zhou, T. et al. Detecting and understanding the multi-decadal variability of the East Asian Summer Monsoon – Recent progress and state of affairs. Meteorologische Z. 18, 455–467 (2009).

Lei, Y., Hoskins, B. & Slingo, J. Natural variability of summer rainfall over China in HadCM3. Clim. Dyn. 42, 417–432 (2014).

Hegerl, G. & Zwiers, F. Use of models in detection and attribution of climate change. WIREs Clim. Change 2, 570–591 (2011).

Streets, D. G. Waldho S T. Present and future emissions of air pollutants in China: SO2, NOx, and CO. Atmos. Environ. 34, 363–374 (2000).

Streets, D. G. et al. Aerosol trends over China, 1980–2000. Atmos. Res. 88, 174–182 (2008).

Hansen, J., Sato, M. & Ruedy, R. Radiative forcing and climate response. J. Geophys. Res. 102, 6831–6864 (1997).

Twomey, S. Pollution and the planetary albedo. Atmos. Environ. 8, 1251–1256 (1974).

Albrecht, B. A. Aerosols, Cloud Microphysics, and Fractional Cloudiness. Science 245, 1227–1230 (1989).

Rotstayn, L. D. & Lohmann, U. Tropical Rainfall Trends and the Indirect Aerosol Effect. J. Clim. 15, 2103–2116 (2002).

Ming, Y. & Ramaswamy, V. Nonlinear Climate and Hydrological Responses to Aerosol Effects. J. Clim. 22, 1329–1339 (2009).

Ramachandran, S. et al. Contribution of natural and anthropogenic aerosols to optical properties and radiative effects over an urban location. Environ. Res. Lett. 7, 034028 (2012).

Li, Z. et al. East Asian Study of Tropospheric Aerosols and their Impact on Regional Clouds, Precipitation, and Climate (EAST‐AIRCPC).J Geophys. Res.: Atmos. 124, 13026–13054 (2019).

Lau, K. M. & Kim, K. M. Observational relationships between aerosol and Asian monsoon rainfall, and circulation. Geophys. Res. Lett. 33, L21810 (2006).

Bollasina, M. A., Ming, Y. & Ramaswamy, V. Anthropogenic Aerosols and the Weakening of the South Asian Summer Monsoon. Science 334, 502–505 (2011).

Ye, J. et al. North drying and south wetting” summer precipitation trend over China and its potential linkage with aerosol loading. Atmos. Res. 125-126, 12–19 (2013).

Li, X. et al. Mechanisms of Asian Summer Monsoon Changes in Response to Anthropogenic Forcing in CMIP5 Models. J. Clim. 28, 4107–4125 (2015).

Yu, S. et al. Anthropogenic aerosols are a potential cause for migration of the summer monsoon rain belt in China. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. Usa. 113, E2209–E2210 (2016).

Taylor, K. E., Stouffer, R. J. & Meehl, G. A. An Overview of CMIP5 and the Experiment Design. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 93, 485–498 (2012).

Lau, W. K. M. & Kim, K. M. Competing influences of greenhouse warming and aerosols on Asian summer monsoon circulation and rainfall. Asia-Pac. J. Atmos. Sci. 53, 181–194 (2017).

Lau, W. K. M., Kim, K. M. & Ruby Leung, L. Changing circulation structure and precipitation characteristics in Asian monsoon regions: greenhouse warming vs. aerosol effects. Geosci. Lett. 4, 28 (2017).

Song, F., Zhou, T. & Qian, Y. Responses of East Asian summer monsoon to natural and anthropogenic forcings in the 17 latest CMIP5 models. Geophys. Res. Lett. 41, 596–603 (2014).

Polson, D. et al. Decreased monsoon precipitation in the Northern Hemisphere due to anthropogenic aerosols. Geophys. Res. Lett. 41, 6023–6029 (2014).

Zhang, Y. et al. What drives the decadal variation of global land monsoon precipitation over the past 50 years? Int. J. Climatol. 38, 4818–4829 (2018).

Xin, X. et al. Comparison of CMIP6 and CMIP5 simulations of precipitation in China and the East Asian summer monsoon. Int. J. Climatol. 40, 6423–6440 (2020).

Yu, T. et al. Comparisons between CMIP5 and CMIP6 models in simulations of the climatology and interannual variability of the east asian summer Monsoon. Clim. Dyn. 60, 2183–2198 (2023).

Khadka, D. et al. An evaluation of CMIP5 and CMIP6 climate models in simulating summer rainfall in the Southeast Asian monsoon domain. Int. J. Climatol. 42, 1181–1202 (2022).

Andrews, T. et al. Precipitation, radiative forcing and global temperature change. Geophys. Res. Lett. 37, L14701 (2010).

Liu, L. et al. A PDRMIP Multimodel Study on the Impacts of Regional Aerosol Forcings on Global and Regional Precipitation. J. Clim. 31, 4429–4447 (2018).

Samset, B. H. et al. Fast and slow precipitation responses to individual climate forcers: A PDRMIP multimodel study. Geophys. Res. Lett. 43, 2782–2791 (2016).

Liu, Y. et al. Anthropogenic Aerosols Cause Recent Pronounced Weakening of Asian Summer Monsoon Relative to Last Four Centuries. Geophys. Res. Lett. 46, 5469–5479 (2019).

Sillmann, J. et al. Extreme wet and dry conditions affected differently by greenhouse gases and aerosols. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 2, 24 (2019).

Rousseau-Rizzi, R. & Emanuel, K. Natural and anthropogenic contributions to the hurricane drought of the 1970s–1980s. Nat. Commun. 13, 5074 (2022).

Huang, R. et al. Characteristics of the Water Vapor Transport in East Asian Monsoon Region and Its Difference from that in South Asian Monsoon Region in Summer. Chin. J. Atmos. Sci. 22, 76–85 (1998).

Rosenfeld, D. et al. Flood or Drought: How Do Aerosols Affect Precipitation? Science 321, 1309–1313 (2008).

Zhao, P. et al. Distinct aerosol effects on cloud-to-ground lightning in the plateau and basin regions of Sichuan, Southwest China. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 20, 13379–13397 (2020).

Zhou, S. et al. An observational study of the effects of aerosols on diurnal variation of heavy rainfall and associated clouds over Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 20, 5211–5229 (2020).

Xu, X. et al. Are precipitation anomalies associated with aerosol variations over eastern China? Atmos. Chem. Phys. 17, 8011–8019 (2017).

Yang, X. et al. Impact of aerosols on tropical cyclone-induced precipitation over the mainland of China. Clim. Change 148, 173–185 (2018).

Prospero, J. M. et al. The atmospheric aerosol system: An overview. Rev. Geophys. 21, 1607–1629 (1983).

Li, Z. et al. Aerosol and monsoon climate interactions over Asia. Rev. Geophys. 54, 866–929 (2016).

Zhao, C. et al. Observational evidence and mechanisms of aerosol effects on precipitation. Sci. Bull. 69, 1569–1580 (2024).

Sun, Y. & Zhao, C. Distinct impacts on precipitation by aerosol radiative effect over three different megacity regions of eastern China. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 21, 16555–16574 (2021).

Shao, Z. et al. East Asian summer monsoon response to anthropogenic aerosols redistribution: contrasting 1950–1980 and 1980–2010 to understand the role of non-Asian forcing. Clim. Dyn. 62, 2187–2205 (2024).

Rotstayn, L. D. et al. Projected effects of declining aerosols in RCP4.5: unmasking global warming? Atmos. Chem. Phys. 13, 10883–10905 (2013).

Levy, H. et al. The roles of aerosol direct and indirect effects in past and future climate change. J. Geophys. Res.: Atmos. 118, 4521–4532 (2013).

Navarro, J. C. A. et al. Amplification of Arctic warming by past air pollution reductions in Europe. Nat. Geosci. 9, 277–281 (2016).

Wang, P. et al. Aerosols overtake greenhouse gases causing a warmer climate and more weather extremes toward carbon neutrality. Nat. Commun. 14, 7257 (2023).

Wilcox, L. J. et al. Accelerated increases in global and Asian summer monsoon precipitation from future aerosol reductions. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 20, 11955–11977 (2020).

Kishore, P. et al. Precipitation variability over India during the 20th and 21st centuries: investigating natural and anthropogenic drivers. Clim. Change 172, 37 (2011).

Kobayashi, S. et al. The JRA-55 Reanalysis: General Specifications and Basic Characteristics. J. Meteorol. Soc. Jpn. 93, 5–48 (2015).

Wu, J. & Shi, Y. Changes in surface wind speed and its different grades over China during 1961–2020 based on a high‐resolution dataset. Int. J. Climatol. 42, 3954–3967 (2022).

Harada, Y. et al. The JRA-55 Reanalysis: Representation of Atmospheric Circulation and Climate Variability. J. Meteorol. Soc. Jpn. Ser. Ii. 94, 269–302 (2016).

Wu, J. & Gao, X. A gridded daily observation dataset over China region and comparison with the other datasets. Chin. J. Geophys. 56, 1102–1111 (2013).

Gelaro, R. et al. The Modern-Era Retrospective Analysis for Research and Applications, Version 2 (MERRA-2). J. Clim. 30, 5419–5454 (1999).

Bosilovich, M. G. et al. Atmospheric Water Balance and Variability in the MERRA-2 Reanalysis. J. Clim. 30, 1177–1196 (2017).

Reichle, R. H. et al. Assessment of MERRA-2 Land Surface Hydrology Estimates. J. Clim. 30, 2937–2960 (2017).

Sun, E. et al. Variation in MERRA-2 aerosol optical depth and absorption aerosol optical depth over China from 1980 to 2017. J. Atmos. Sol.-Terrestrial Phys. 186, 8–19 (2019).

Gillett, N. P. et al. The Detection and Attribution Model Intercomparison Project (DAMIP v1.0)contribution to CMIP6. Geosci. Model Dev. 9, 3685–3697 (2016).

Taylor, K. E. Summarizing multiple aspects of model performance in a single diagram. J. Geophys. Res.: Atmos. 106, 7183–7192 (2001).

Sen, P. K. Estimates of the Regression Coefficient Based on Kendall’s Tau. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 63, 1379–1389 (1968).

Eyring, V. et al. Overview of the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6) experimental design and organization. Geosci. Model Dev. 9, 1937–1958 (2016).

Mitchell, D. M. et al. The vertical profile of recent tropical temperature trends: Persistent model biases in the context of internal variability. Environ. Res. Lett. 15, 1040b4 (2020).

Zhang, X. et al. Greening-induced increase in evapotranspiration over Eurasia offset by CO2 -induced vegetational stomatal closure. Environ. Res. Lett. 16, 124008 (2021).

Wang, B. et al. How to Measure the Strength of the East Asian Summer Monsoon. J. Clim. 21, 4449–4463 (2008).

Li, J. & Zeng, Q. A unified monsoon index. Geophys. Res. Lett. 29, 1274 (2002).

Sun, X., Chen, L. & He, J. Index of land-sea thermal difference and its relation to interannual variation of summer circulation and rainfall over East Asian. Acta Meteorol. Sin. 2, 164–172 (2002).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42375112). It should be noted that major parts of the early-stage visualization and data processing were performed using Python.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors participated the study. J.Z. co-designed the study with Y.W.L. Y.W.L. conducted the analysis and wrote the first draft in discussions with J.Z. J.Z. revised the manuscript. Jin.Z. and Y.H.G. provided ideas in the Data and Methods section. T.H., X.Q.D., and Y.Q.L. contributed to picture improvement and manuscript improvement.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lang, Y., Zhang, J., Zhao, J. et al. Mechanisms and quantification: How anthropogenic aerosols weaken the East Asian summer monsoon. npj Clim Atmos Sci 8, 13 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-00903-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-00903-6

This article is cited by

-

Precipitation pattern changes in Northern China before and after the weakening of the Asian summer monsoon

Climate Dynamics (2025)

-

Modeling the formation of aerosols and their interactions with weather and climate: critical review and future perspectives

Frontiers of Environmental Science & Engineering (2025)