Abstract

The global flood risk urges an improved understanding of flood magnitude and its mechanism, which needs insights from pre-instrumental flood investigations. Due to data scarcity, reconstructing pre-instrumental flood magnitudes relies on statistical downscaling, failing to capture nonlinear and dynamic characteristics. We developed a dynamical approach, NorESM-WRF-SWAT, integrating a global climate, a regional, and a hydrologic model to investigate the 1931 Yangtze River flood (the deadliest in the world) and compared it with the 1998’s. Through validation, our method outperforms the statistical method in simulating precipitations and river discharges. For the first time, we presented detailed insights into the intensity and duration of the 1931 flood, revealing a smaller magnitude but associated with an amplified loss, likely due to social vulnerability and reduced societal resilience compared to the 1998’s. While successful simulation can be interfered with by model variability, our dynamical method shows promise for simulating pre-instrumental flood and building a long-term pre-instrumental-hydrology database.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Flooding, one of the most recurrent and devastating natural hazards1,2, exerts profound damage to human society. From 2000 to 2019, floods caused a $651 billion loss and killed 0.53 million people3. The deadliest flood happened in China in 1931, causing over 2 million casualties4,5. Another China devastating flood in 1998 caused 4150 fatalities and ~255 billion RMB in damage6. Unfortunately, ongoing global warming and escalating anthropogenic activities have globally amplified flood damages in recent decades7. Such risk will likely intensify in the coming centuries2,7, thus necessitating a better comprehension of flood magnitude and its mechanism for effective flood management and loss reduction.

Enhancing the comprehension of flood magnitude (encompassing flood frequency, flood intensity, and flood-affected areas) and mechanism needs valuable insights from pre-instrumental flood investigations. Most flood studies8,9,10,11,12 have primarily focused on the instrumental period, neglecting the exceptional and extreme floods in the pre-instrumental periods (before extensive continuous and systematic instrumental records). These pre-instrumental floods offer substantial samples of extreme flood events, thereby aiding in better constraining uncertainties in flood magnitude estimation13,14,15,16 and understanding the mechanism behind them.

However, pre-instrumental flood investigations present an inherent challenge in reconstructing the flood magnitude, such as intensity, duration, and spatial distribution. Paleoflood indicators17, including documental, geological, and biological records, can indicate pre-instrumental flood occurrence at a single or a few sites, but might not reveal spatial information and details on the duration and intensity of a flood in the pre-instrumental period. Consequently, the estimation of pre-instrumental flood magnitudes heavily relies on model simulations. Previous studies on pre-instrumental flood simulations primarily employed statistical methods, using statistical downscaling connecting global and hydrological model simulations16,18,19,20 (almost exclusively utilizing bias-correction downscaling). These statistical methods involve establishing relationships between the interpolated global climate model output and the regional observation at refined specific grids (or meteorological stations) during the historical instrument period. The empirical relationship was assumed to be robust when applied to different periods (such as the pre-instrumental time or specific years), which, however, may not be temporally stable or strong due to the nonlinear and dynamic processes in the climate system21,22,23,24,25. As a result, the statistical approach introduces uncertainties for flood simulation in the pre-instrumental past or specific years. As an alternative, the dynamical method (employing dynamical downscaling to connect global climate and hydrology modeling) is commonly used in modern flood investigations26,27,28 but remains absent in pre-instrumental flood studies despite its potential to improve the simulations. While climate models in the current generation may have limited skills in simulating specific paleoclimate (the climate prior to the instrumental period) extreme events in specific years, successfully simulating such events relies on chance. Nevertheless, dynamically simulating paleoclimate extreme events, such as floods during the pre-instrumental period, offers valuable case studies to investigate the flood magnitude and the underlying dynamic, holding the potential to improve our understanding of these events.

Herein, we present an innovative method supported by dynamical simulations to investigate the catastrophic Yangtze River flood in 1931 and compare it with the flood in 1998. To achieve this, we utilize the fast version of the Norwegian Earth System Model (NorESM1-F) to conduct last millennium (1001–2000) simulations. From these simulations, we select the simulations specifically for the years 1931 and 1998, representing an extreme flood in the pre-instrumental period and a flood in the instrumental period. Subsequently, we employ the Weather Research and Forecasting (WRF) model to perform dynamical downscaling in the Yangtze River watershed along with its surrounding region. Finally, we use the Soil and Water Assessment Tool (SWAT) model to simulate the floods in the Yangtze River watershed. These two floods are selected based on data availability to validate our flood simulations. Despite the inherent uncertainties associated with simulating extreme events, the reasonably well-simulated representation of precipitation in the Yangtze River watershed for 1931 and 1998 provides a solid foundation for our case study and the establishment of our modeling method. To depict flood features, we simulated daily discharges during 1982–2000 and calculated flood intensity and duration based on them. In the analyses of flood spatial variability, we divided the Yangtze River watershed (presented by 279 spatial units in the SWAT model) into eleven sub-catchments (see Methods), with six in the upstream and five in the mid-downstream areas of the watershed. To evaluate the dynamical approach, we also conduct an experiment with the statistical method (NorESM-BC-SWAT), employing a quantile-mapping-based bias-correction technique (a commonly used statistical downscaling) to downscale NorESM-output, and subsequently using the downscaled data to drive the SWAT.

Results

Evaluation of flood simulations

The NorESM effectively captures the extreme precipitation in the Yangtze River watershed in 1931 and 1998 (Fig. S1), aligning reasonably well with the 20CRv3 reanalysis data29. Within the primary precipitation area (i.e., the mid-downstream) of the Yangtze River watershed, the simulated precipitation during the main rainy season (June–July) is 236.3 and 253.5 mm/mon for 1931 and 1998, exceeding one standard deviation range (169.5 ± 41.6 mm/mon) simulated over the last millennium. In the 20CRv3 data, the precipitation is 314.4 and 317.4 mm/mon in 1931 and 1998, surpassing the average (246.7 mm/mon) by one standard deviation (43.6 mm/mon) from 1845 to 2000. Note that the precipitation in 1931 is lower compared to 1998, both in our simulation and the reanalysis.

Furthermore, the evaluation of the simulated discharge in the Yangtze River during the 1998 flood demonstrates the skillfulness of our dynamical approach (Fig. 1b, d, f, h). Thanks to the well-simulated precipitation by NorESM, the refined precipitation from WRF (Fig. S2), and the well-constrained parameters in SWAT (Table S4), the dynamical approach (NorESM-WRF-SWAT) exhibits a remarkable improvement in the discharge simulation, compared to the statistical simulation (NorESM-BC-SWAT) or the simulation directly forced with global model outputs (NorESM-SWAT). Although accurately simulating daily precipitation is quite challenging, with our dynamic method, the simulated daily discharge to some extent is comparable to observations at Yichang, Hankou, Jiujiang, and Datong stations (Fig. 1b, d, f, h), generally aligning with the discharge observations or the precipitation-observation-forced simulation (ClimObs-SWAT) despite some discrepancies in discharge peaks. The RMSE of daily discharge at Datong station (reflecting the bias of the whole watershed, Fig. 1h), is reduced by 38% or 51% in the NorESM-WRF-SWAT simulation, indicating reductions in the model-observation mismatch compared to the NorESM-BC-SWAT or NorESM-SWAT simulations. The largest peak (max daily discharge) in the NorESM-WRF-SWAT simulation aligns more closely with the observation, showing a smaller model-data bias of 14%, compared to 19% for NorESM-BC-SWAT and 113% for NorESM-SWAT.

They are Yichang (a, b), Hankou (c, d), Jiujiang (e, f), and Datong (g, h) stations. The left and right columns show the results of 1931 and 1998, respectively. The red, orange, gray, and blue lines display the simulated discharge in the NorESM-WRF-SWAT, the NorESM-BC-SWAT, the NorESM-SWAT, and the ClimObs-SWAT experiments, respectively. The solid black line illustrates the observed discharge and the dashed black line is the discharge digitized from the “river level-time curve” in the book “The Great Floods in Chinese History.” R2 (determinate coefficient), NSE (Nash-Sutcliffe efficiency coefficient), and RMSE (root mean square error, %) are calculated based on the daily simulations against the observations.

Again, our dynamical approach (NorESM-WRF-SWAT) generally well simulates the discharge in 1931, particularly on a monthly scale, matching the observed-like data generated from “river level-time curves” (Fig. 1a, c, e, g; see details about the data in Methods). Due to the inherent uncertainties in simulating daily precipitation with climate models, the simulated daily discharge fluctuations are much larger than the observed-like data. However, it is important to note that the discharge records for the 1931 flood also include uncertainties when floods break dams and invade plains (Note S1). Even so, the NorESM-WRF-SWAT simulation exhibits a substantial improvement compared to the NorESM-SWAT and NorESM-BC-SWAT results, with the bias (indicated by the RMSE of daily discharge at Datong station; Fig. 1g) reduced by 62% and 11%, respectively. Furthermore, NorESM-WRF-SWAT’s largest peak discharge matches the observed-like better, with a bias of 25%, compared to 29% for NorESM-BC-SWAT and 134% for NorESM-SWAT.

Smaller flood magnitude in 1931 compared to 1998

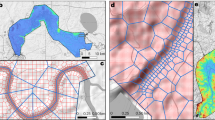

The NorESM-WRF-SWAT simulated annual runoff for the Yangtze River watershed in 1931 is approximately 981 billion m3, notably smaller than the amount of 1064 billion m3 in 1998 (Fig. 2c). In 1931, a reduction in discharge volume appears in six sub-catchments (out of eleven) in the Yangtze River watershed (Fig. 2c). The discharge decreases pronouncedly in the Jialingjiang (J) and Min-Tuo (M) sub-catchments, with 62 and 82 billion m3 in 1931 compared with 129 and 124 billion m3 in 1998. During the flooding months (usually April-October)30, multiplying the eleven zones of the Yangtze River watershed (in total 77 months*zones), more than half (40) of them show smaller runoff in 1931 compared with 1998 (Fig. S3). Particularly, in the peak flooding season (July–August), 16 (in total 22 months*zones) exhibit smaller runoff (Fig. S3).

a and b show the spatial distribution of annual runoff (unit: mm) in 1931 and 1998, respectively. The red polygons divide the Yangtze River Watershed into 11 sub-catchments (Mu, Mm, Ml, Jsu, Jsl, M, J, W, H, D, P), each composed of a subset of the 279 spatial units (color blocks). The mean (m) and standard deviation (std) were calculated based on the annual runoff of all the units over 1982–2000. c displays the regional annual runoff (unit: 109 m3) averaged over the spatial units within each of these sub-catchments, blue for 1931 and orange for 1998. The red number indicates the change in percentage in 1931 relative to 1998. Yup, Ymd, and All indicate the upstream, mid-downstream, and entire watershed.

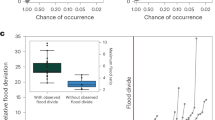

Consistent with the lower runoff in 1931, the NorESM-WRF-SWAT flood intensity index (average of the standardized daily discharge exceeding the 90% quantile, detailed in Methods) is smaller averaged over all the spatial units of the entire Yangtze River watershed compared to 1998 (Fig. 3). The averaged flood intensity is 1.62 (unit:1, detailed in the Methods) in 1931, while it is 1.79 in 1998. Among the eleven sub-catchments, nine exhibited smaller intensity in 1931. Within these nine sub-catchments, the upper mainstream (Mu) and Min-Tuo (M) sub-catchments show decreased intensity pronouncedly (1.44 and 1.57 in 1931 whereas 1.85 and 1.79 in 1998). Meanwhile, the flood in 1931 shows a smaller area (75,265 km2) with the intensity exceeding the average by one standard deviation (calculated based on the flood intensity over all the units during 1982–2000), relative to 1998 (205,818 km2). Such area reduction from 1931 to 1998, is more pronounced in the mid-downstream with a reduction of 88.5%, compared to 32.2% in the upstream.

Flood intensity (unit: 1) in a year of each spatial unit (in total 279, color blocks in a, b) is calculated as the average of standardized discharges above 1.28 (90% quantile of daily discharges over 1982–2000). a and b show the spatial distribution of flood intensity in 1931 and 1998, respectively. The gray polygons divide the Yangtze River Watershed into 11 sub-catchments (Mu, Mm, Ml, Jsu, Jsl, M, J, W, H, D, P), each composed of a subset of the 279 units. The mean (m) and standard deviation (std) were calculated based on the flood intensity of all 279 units over 1982–2000. c displays the regional flood intensity in 1931 (the blue) and 1998 (the orange) in the 11 sub-catchments of the Yangtze River Watershed. Yup, Ymd, and All indicate the upstream, mid-downstream, and entire watershed. The horizontal black lines (whiskers) show flood intensity start and end. The left and right bounds of the boxes are the first and third quartiles. The red bar in the middle shows the average.

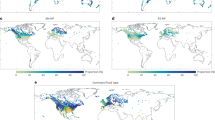

Also, the simulated flood duration (days of daily discharge above the 90% quantile, detailed in Methods) is shorter in 1931, averaged over all the spatial units of the entire Yangtze River watershed, in comparison to 1998 (Fig. 4). The averaged duration is 25 days in 1931 compared to 39 in 1998. This shorter duration in 1931 remains in the mid-downstream sector (31 days in 1931 versus 32 days in 1998), although not significantly.

Flood duration (unit: days) in a year of each spatial unit (color blocks in a, b) is identified as the number of days with the standardized discharge index (Sdi) above 1.28 (90% quantile of daily discharges over 1982–2000). a and b show the spatial distribution of flood duration in 1931 and 1998, respectively. The red polygons divide the Yangtze River Watershed into 11 sub-catchments (Mu, Mm, Ml, Jsu, Jsl, M, J, W, H, D, P), each composed of a subset of the 279 units. The mean (m) and standard deviation (std) were calculated based on the flood duration of all 279 units over 1982–2000. c displays the flood duration in 1931 (the blue) and 1998 (the orange) in the 11 sub-catchments of the Yangtze River Watershed. Yup, Ymd, and All indicate the upstream, mid-downstream, and entire watershed. The horizontal black lines (whiskers) show the flood duration start and end. The left and right bounds of the boxes are the first and third quartiles. The red bar in the middle shows the average.

The NorESM-WRF-SWAT simulation clearly reveals that the flood in the Yangtze River watershed in 1931 had a smaller magnitude than in 1998, characterized by smaller intensity and shorter duration. This conclusion is substantiated by precipitation reanalysis data, which shows reduced precipitation in 1931 compared to 1998 (see Fig. S1 and the first paragraph in Section “Evaluation of flood simulations”). Also, it is supported by discharge observations, exhibiting less discharge volume in 1931 than in 1998. Specifically, the observation data reveals that the discharge at Datong station during the flooding months reached 851 billion m3 in 1931, but 941 billion m3 in 1998. The smaller flood magnitude in 1931 is further evidenced by the inundated farmlands and victims. The relative number of inundated farmlands is 4.6% in 1931 compared to 5.9% in 1998, while the relative number of victims was 7.3% in 1931 compared to 7.5% in 1998 (Table S1).

Amplified flood-induced damage in 1931 compared to 1998

Although our simulations suggest a smaller magnitude of the Yangtze River flood in 1931, the loss of life induced by the flood was markedly higher than 1998 (Table S1). According to “The Great Floods in Chinese History”6, in the mid-downstream sector alone, the death toll in 1931 reached ~163,500. In contrast, the reported death toll in the mid-downstream from “China Meteorological Disaster Dictionary”31 was 1145 in 1998. The relative number of casualties (see Methods and Table S1) was ~0.5% in 1931, significantly larger than the value recorded in 1998 (less than 0.001%).

Furthermore, other socioeconomic damages (direct economic losses and damaged houses in the mid-downstream area, Table S1) were more prominent in 1931 than 1998. The relative number of direct economic losses was ~5.5% in 1931, more extensive than the value of ~1.4% in 1998. The relative number of damaged houses was 0.75% in 1931 and 0.7% in 1998. (see details about the damage definition and values in Methods and Tables S1–3)

The more substantial socioeconomic impacts of the 1931 flood could be attributed to the enhanced social vulnerability in 1931, which was caused by civil and ethnic war, foreign exploitation, and domestic corruption and incompetence32,33,34. Both flood intensity (a natural factor) and societal resilience (an anthropogenic factor) can influence socioeconomic damage. In a vulnerable society with weakened societal resilience, anthropogenic factors could substantially amplify nature-hazard-induced harms, thus contributing to catastrophic consequences.

Discussions

The method captures a positive precipitation anomaly in 1931 and 1998, as well as the associated mechanisms, which we cannot deny even though the successful capture is by chance. Our recent study has demonstrated that to simulate a single year remains possible, when the model can simulate some mechanism-related features that once happened in the past. For example, the last millennium experiment successfully captured the extreme heat event in 1743 due to the accurate simulation of cooling in Northeast China and East Siberia35. Notably, the simulated West Pacific Subtropical High (WPSH) exhibits a westward extension in both 1931 and 1998 relative to the climate mean state, despite some weakening (Fig. S4a, b). Such kind of extension makes the study region closer to the northwestern periphery of the WPSH (Fig. S4a, b), which is typically the location of large-scale quasi-stationary frontal zones and usually brings large precipitation to its underlying ground5,36,37. Therefore, the western extension here possibly causes extreme precipitation in the study area. Consistently, a similar shift of the WPSH was also noted in the observation of both 1931 and 1998 (using 20CRv3, Fig. S4c, d). In addition to the two successful cases in 1931 and 1998, NorESM captured five other flood events identified in the reanalysis during 1845–2000, along with the associated WPSH westward shift (see the calculation in Note S2). Including the successfully simulated seven floods, the reanalysis totally identified 48 floods linked to the WPSH westward shift. This provides strong evidence that the climate model is capable of capturing both the extreme event and its underlying mechanism, although the likelihood remains low at just 14.6% (7 out of 48 years).

Although the motivation of the study is to establish a method for pre-instrumental flood simulation, uncertainties in simulating precipitation with a global climate model should not be ignored. The global climate model could reasonably simulate the precipitation to a certain degree. Our simulation demonstrated that the first Empirical Orthogonal Function (EOF1) mode, of NorESM-simulated annual precipitation (accumulated over the main rainy season, i.e., June–July) anomaly field during 1001–2000, shows a similar spatial pattern to the EOF2 of the reanalysis during 1951–2000 (Fig. S5a, d). However, precipitation simulations for specific years are inevitably not accurate, especially for spatial distribution (encompassing the spatial pattern and the related intensity). Consequently, in our study, the simulated precipitation anomalies show remarkable differences from the reanalysis data. The simulated precipitation anomaly exhibits a wet patch south Yangtze River in 1931 (Fig. S6a), and a wide northeast-southwest wet strip across the Yangtze River in 1998 (Fig. S6b). In contrast, the reanalysis data displays the typical pattern of tripole or dipole with a narrow east-west wet strip along the Yangtze River in 1931 (Fig. S6c) or 1998 (Fig. S6d). Our failure to display precipitation distribution could result in difficulty in diagnosing flood intensity differences between these two floods. The precipitation anomaly difference between 1931 and 1998 from the NorESM simulation is 17.2 mm/mon, nearly half of its standard deviation (41.6 mm/mon calculated over 1001–2000), while the difference from the reanalysis is 3 mm/mon, far less than half of its standard deviation (43.6 mm/mon calculated over 1845–2000) (Fig. S1). Consequently, the discharge results from the hydrological model driven by the NorESM for the 1931 flood, even with the WRF downscaling, poorly reproduce the peak flows and their timing of multiple peaks during the hydrograph (Fig. 1a). The above failures are largely attributed to the internal variability (e.g., ENSO and PDO) in the simulated or real climate system. While the reanalysis data (Fig. S7c, d) and the previous studies5,38 show that the higher precipitation in 1998 is driven by a strong El Niño and suggests a similar situation in 1931, there is no significant El Niño in our simulation of 1931 (Fig. S7a) or 1998 (Fig. S7b). Our simulation failed to capture such internal variability of El Niño in both 1931 and 1998. Additionally, uncertainties could also arise from the parameterization schemes in the regional climate model, which may not accurately simulate the actual physical processes, as well as the limited spatial resolution, which leads to difficulties in representing fine-scale terrain and features.

To be more cautious, we further need paleoclimate data assimilation39 and ensemble simulations to constrain the uncertainties associated with internal variability. Using the ensemble method, we can select the model with a similar precipitation distribution in 1931 (or 1998) to the observation from the large ensemble. Additionally, paleoclimate data assimilation, combining paleoclimate simulations with empirical precipitation information from proxy indicators, is designed with the endeavor to capture real internal climate variability. Using paleoclimate assimilated outputs from multiple models or ensembles to drive dynamical downscaling models and hydrological models can further constrain the uncertainty in reproducing precipitation patterns and intensity, thereby producing more reliable flood simulations during the pre-instrumental period.

Despite the uncertainties in precipitation simulation, our method still shows better skills in simulating precipitation and discharge compared to the statistical method, which could be attributed to the dynamical downscaling. Dynamical downscaling, with a refined topography, has been demonstrated to allow for a reasonable representation of the nonlinear dynamic precipitation process40,41,42,43. In our WRF simulations, the topography field exhibits a refinement in the upstream area of the Yangtze River watershed compared to the NorESM (the red box in Fig. S8a, b). The refined topography tends to enhance the representation of fine-scale convections and nonlinear interactions between local (or micro/mesoscale) and large-scale processes driven by the refined topography40,41,42, thus potentially contributing to added value in precipitation simulation (Fig. S2). In contrast, the performance of statistical downscaling usually depends on a strong correlation between the global model output and regional climate observation, which, however, seems typically weak23,24. Accordingly, in our results, the correlations at specific grids between the simulated daily precipitations during 1982–2000 from the interpolated NorESM output and the observation appear not strong, with the correlation coefficient (R) ranging from zero to 0.29. Based on such weak correlations, statistical downscaling often struggles to capture the patterns or trends from the observations, probably resulting in limited added value to the global downscaled data. Therefore, our WRF simulation appears to be more effective in capturing the precipitation spatial pattern of the first leading Empirical Orthogonal Function (EOF1) mode, extracted over daily precipitation fields during the main rainy season from 1982 to 2000 compared to the quantile-mapping-based bias-correction downscaling (BC, a commonly used statistical downscaling). The spatial R of this precipitation mode between the simulation and observation is 0.89 from WRF simulation, contrasting with 0.81 and 0.68 from BC and NorESM. Also, the WRF simulation is more skillful at presenting the temporal fluctuation of the 366-day daily precipitations (averaged spatially over the Yangtze River watershed and then temporally over daily precipitation during 1982–2000), compared to BC and NorESM. The temporal R between the simulated 366-day daily precipitations from WRF simulation and the observation is 0.87, compared to 0.80 and 0.85 from BC and NorESM results. Such better performance of precipitation simulation with dynamical downscaling compared to the statistical method was also indicated in previous studies44,45. Due to the better skill in precipitation simulation, our dynamical method (NorESM-WRF-SWAT) exhibits better proficiency in discharge simulation, compared to both NorESM-BC-SWAT and NorESM-SWAT (Fig. 1).

In the article, we presented a first case study using an innovative and dynamical method to simulate the pre-instrumental flood, despite the uncertainty of internal variability from climate simulations. The results demonstrated that our dynamical method outperformed the statistical method in simulating precipitation and discharge, and decreased the simulation error to a certain degree. The dynamical method, integrating dynamical downscaling with global climate and hydrological models, demonstrates the potential to simulate floods during the pre-instrumental period, enabling the investigation into flood magnitudes and the driving dynamics related to atmospheric circulations. The further development of this method seems to open a window for the opportunity to establish a comprehensive long-term paleo-hydrological database, which may help to promote innovative insights into flood variabilities and the potential mechanisms behind them.

Methods

For pre-instrumental flood simulation with the dynamical method (NorESM-WRF-SWAT) in the Yangtze River watershed, we developed a practical frame involves five steps: data collection and processing, global climate simulation, regional climate simulation, hydrological simulation, and flood index calculation.

Besides the NorESM-WRF-SWAT experiment, we conducted three others for model evaluation, including NorESM-BC-SWAT, NorESM-SWAT, and ClimObs-SWAT, using statistical downscaled NorESM-output, NorESM outputs, and climate observations to force SWAT, respectively. To evaluate flood simulation skills respectively in the instrumental and non-instrumental period, we extracted daily discharges in 1998 (from the four experiments) and 1931 (from the four, excluding ClimObs-SWAT due to lacking climate observations). Daily precipitations during 1982–2000 were also acquired from the four experiments to assess the performance of precipitation simulation with the dynamical downscaling. The ClimObs-SWAT simulation covering 1982–2018 was also conducted for the SWAT calibration. To calculate flood (usually exceeding a threshold calculated based on a baseline) intensity and duration in 1998 and 1931 from the NorESM-WRF-SWAT experiment, we also obtained the daily discharges during 1982–2000 as the baseline.

Models

The Norwegian Earth System Model (NorESM) is built under the structure of the Community Earth System Model (CESM; see the CESM website at http://www2.cesm.ucar.edu/). A fast version of the model, NorESM1-F46 (Guo et al. 2019), was used to simulate the global climate. Compared to earlier versions of the model47, the NorESM1-F suits particularly well for long simulations with moderately high resolution and contains improved process representations and climate performance. The atmospheric component of the NorESM1-F uses a resolution of 1.9° (latitude) by 2.5° (longitude) in the horizontal and 26 levels in the vertical. The ocean component employs a tripolar grid, with a horizontal resolution of nominal 1° and a vertical resolution of 53 layers.

The Weather Research and Forecasting (WRF) Model is a mesoscale numerical model, consisting of a model solver of fully compressible Eulerian and non-hydrostatic equations with a run-time hydrostatic option48. This model employs a terrain-following coordinate, using the third-order Runge-Kutta time integration scheme and the Arakawa-C grid. The WRF model has been extensively utilized in regional climate simulations over China and has demonstrated its capability to capture key regional climate features49,50,51. Here, we apply version 3.9.1.1 of the WRF model to dynamically downscale the global climate (NorESM-output) to a high horizontal resolution.

The Soil and Water Assessment Tool (SWAT)52 is a semi-distributed, physically-based, and time-continuous hydrological modal designed for basin-scale assessments. In SWAT, the watershed is discretized into sub-basins (spatial units) based on river nets and DEM. The model governs the hydrological cycle through the water balance, encompassing two main components: runoff generation over the land and flow routing through channels. SWAT incorporates essential hydrological processes, such as surface runoff, evapotranspiration, soil moisture, lateral flow, base flow, and flow routing. Widely recognized for its effectiveness, SWAT has been successfully applied in watersheds globally, demonstrating its proficiency in simulating discharge dynamics53. Here, we use SWAT2012-rev.627 (see the SWAT website at https://swat.tamu.edu) to simulate daily discharges in the Yangtze River watershed.

Experimental design for NorESM-WRF-SWAT

We conducted the global climate simulation over the past millennium with the NorESM1-F model. This experiment starts from the last hundred years of the pre-industrial experiment, and integrates consecutively from 1001 to 2000, including both the pre-industrial (1001–1850) and historical (1851–2000) periods. In our experiment, the solar radiative forcing data from Vieira54, volcanic forcing data from Gao55, and the greenhouse gas data from Ammann56 are incorporated. The boundary conditions, such as land cover, are consistent with the pre-industrial experiments. The model has exhibited commendable skill in reproducing precipitation variability in China, successfully capturing extreme wet (such as 1931) and dry (such as 1485 and 1875–1876) conditions in the historical period in China57. The NorESM outputs, including precipitation and minimum/maximum surface air temperature at a 6-hour time frequency, were used to drive the regional climate model WRF.

WRF (Weather Research & Forecasting Model) conducted the regional climate simulation over 1931 and 1982–2000, with spin-up times of at least one year and 0.5 year, respectively. Six-hourly NorESM outputs drove the WRF simulation, covering the Yangtze River watershed and its surrounding regions with a spatial grid spacing of 24 km (Fig. S8a). In the WRF simulations, the microphysics scheme used is Single-Moment 6-class Microphysics (WSM6)58, which includes graupel, ice, and the associated processes. The radiation scheme was set as RRTMG long-wave and shortwave radiation transfer59 which can process a number of trace gases and interact with resolved clouds and cloud fractions. The surface layer is depicted by the revised Fifth-Generation Penn State/NCAR Mesoscale Model (MM5) Monin-Obukhov scheme48. The land surface process is modeled by the Noah land surface model with multi-parameterization options (Noah-MP)60,61. The cumulus convective precipitation is parameterized by the Kain-Fritsch scheme62, and the planetary boundary layer is depicted by the Yonsei University scheme (YSU)63. Additional configuration details can be referred to Yu et al.64 Six climate outputs from WRF, including precipitation, downward shortwave radiation, surface wind speed, relative humidity, and minimum and maximum surface air temperature at a daily scale, were used to drive the hydrological model. WRF demonstrated its capability to reproduce spatial patterns and inner-annual features of precipitation in the Yangtze River watershed (Fig. S2c–e).

The SWAT model was used to conduct the hydrological simulation, and it simulated the daily discharges of 1931 and 1982-200. SCS (Soil Conservation Service method)65 and Penman–Monteith method66 were used to calculate surface runoff and evapotranspiration, respectively. Flow routing through the channel was calculated by the variable storage coefficient method67. Using ArcSWAT (an ArcGIS-ArcView extension and interface for SWAT, see the tool at https://swat.tamu.edu/software/arcswat/), 279 river segments and their corresponding sub-basins were generated.

Each of the six climate variables at a daily scale from the WRF, underwent pre-processing before being used to drive the SWAT. The processing involves interpolating the climate to pre-defined finer grids (with a resolution of 0.25° by 0.25°, the size of the smallest sub-basin) and subsequently averaging the interpolated value of grids within each given sub-basin. Conservative and bilinear interpolation were used for precipitation and the other five, respectively. Compared to the traditional method, which sets the climate of a given sub-basin as the climate of only one station (or grid) within or near this sub-basin, our pre-processing makes better use of climate data.

In the ClimObs-SWAT experiment covering 1982–2018 (refer to “Experimental designs for NorESM-BC-SWAT, NorESM-BC-SWAT and ClimObs-SWAT” section), we conduct SWAT calibration using the SUFI-2 algorithm by the SWAT-CUP software package68. In the calibration, 29 parameters (7 global and 22 distributed ones, Table S5) were selected and 31 discharge stations (Fig. S8c and Table S6) were utilized.

We first calibrated the global parameters one by one, and then the distributed ones. For a given global parameter, parameter optimization is guided by maximizing the alignment between the simulated and observed discharge at the Datong station (Fig. S8c), using Nash-Sutcliffe efficiency (NSE) as the optimization index. To calibrate the distributed parameters, we grouped the 279 sub-basins based on the corresponding nearest downstream stations. For a given discharge station, we collected all the sub-basins within its upstream area, excluding those draining to the upstream stations; the remaining sub-basins were then allocated into the same group and underwent parameter calibration based on this station. Subsequently, we sequentially optimized the distributed parameters group by group from upstream to downstream. For each optimizer, at least 200 simulations are expected to be conducted before a good skill (NSE > 0.5) was obtained or the skill didn’t increase. For each simulation run, the calibration (or validation) time is listed in Table S6, with a spin-up time of at least one year. Given the limited availability of observations, we maximize the inclusion of all available data to achieve a well-constrained SWAT model. Therefore, calibration (or validation) data may involve different time ranges between stations, despite the theoretical expectation that the time ranges should be identical.

The calibration result demonstrates that the SWAT generally exhibited good skill in simulating discharge in the Yangtze River watershed (Table S4). Among the 31 stations, 29 show a satisfactory performance, with NSE, absolute-PBIAS (percent bias), and R2 (coefficient of determination) of daily discharges in the range of 0.61–0.88, 22–31%, and 0.64–0.93, respectively.

Experimental designs for NorESM-BC-SWAT, NorESM-BC-SWAT and ClimObs-SWAT

In the NorESM-BC-SWAT experiment (statistical simulation), we employed quantile-mapping-based69 bias-correction (a commonly used statistical downscaling technique), to downscale the NorESM precipitation, and used the downscaled data to drive the SWAT. The NorESM precipitation and the observation were up-sampled to a resolution of 0.25° by 0.25° grids, and then quantile mapping was used to adjust the cumulative distribution function of interpolated NorESM precipitation to align with the observed grid by grid. For the SWAT simulation, the bias-corrected precipitation, along with WRF outputs of temperature, radiation, wind, and humidity, was utilized as climate forcings. The simulation covers 1931 and 1982–2000, with at least 1 year and 0.5 year as spin-up times of the SWAT (or WRF), respectively.

In the NorESM-SWAT experiment, precipitation and minimum/maximum surface air temperature from NorESM with a resolution of 2.5° by 1.9°, along with radiation, wind, and humidity from WRF, were utilized to drive SWAT in 1998 and 1931 with spin-up times of at least one year, respectively.

Lastly, the ClimObs-SWAT experiment incorporated climate observations, including precipitation and temperature data at a resolution of 0.5°, downward shortwave radiation with a resolution of 0.25° by 0.25°, and surface wind speed and relative humidity at the station scale. The simulation covers 1931 and 1982–2018 (for SWAT calibration) with spin-up times of at least 1 year, respectively. For these three experiments, each climate variable underwent pre-processing (mentioned above) before being used to drive the SWAT.

Flood indexes

To depict the flood characteristics in 1931 and 1998, we standardized the daily discharges from the NorESM-WRF-SWAT experiment, and based on these we calculated flood intensity and duration.

To facilitate a better comparison of discharges across different scales, we calculate Standardized Discharge Index (Sdi) for each of the 279 sub-basins based on the daily discharge from 1982–2000. For discharges of each sub-basin, the standardization involves two steps: 1) constructing a specific density function that best fits the daily discharge sequences during 1982–2000 from the NorESM-WRF-SWAT experiment; 2) translating the density function into a standard normal distribution (a mean of zero and standard deviation of unity). The transformed discharge from the second step was the Standardized Discharge Index (Sdi). In the processing of fitting, a total of 14 types of probability distributions were separately used to fit daily discharge sequences, including gamma, exponential, pareto, tri-gamma, inverse gamma, norm, log-norm, beta, log-logistic, uniform, logistic, cauchy, inverted weibull, and burr. Parameters of the function were optimized by maximum likelihood estimation in the R-package VineCopula (using function fitdist)70. From the 14 fits, gamma was chosen with the minimum Bayesian information criterion (BIC)71.

Compared to other standardized indices widely used for measuring wet conditions, exampled by Standardized Runoff Index (SRI)72, the algorithm idea of the above standardization keeps the inner-annual variability signal of the discharge. This standardization is performed once over the entire period and thus can be used for analyzing inner-annual variability and extracting extreme daily discharge. In contrast, the standardization of SRI is performed separately by seasons (or months), which removes the inner-annual variability signal of the discharge, thus difficult to detect extreme daily discharge.

To evaluate flood magnitude in different years, flood intensity and duration are calculated on a yearly scale and are used to depict the average amount and the frequency of the large flow. Flood intensity of a specific year is defined as the average of Sdi values exceeding 1.28 (corresponding to 90% quantile of daily discharge during 1982–2000) in this year. Flood duration is identified as the number of daily discharges with Sdi above 1.28. The index (intensity or duration) was calculated individually for each sub-basin in each year. We also calculated flood50 intensity (Fig. S10 and Note S3) and duration (Fig. S11 and Note S3), where the Sdi is above zero (50% quantile).

Flood-induced socioeconomic damages

We use the relative numbers of socioeconomic damages to measure flood-induced socioeconomic impact. A relative number of the socioeconomic damage was calculated as the absolute number of the damage divided by the total. The damages of five elements were calculated, including inundated farmland, damaged houses, victims, direct economic losses, and death tolls, for which the absolute numbers and the corresponding totals were available. For inundated farmland, victims, and direct economic losses, the total losses are the total farmland area, population, and GDP of China, respectively, while for death tolls, the total is the victim. In the case of damaged houses, the total houses were substituted by the total population, as statistics on total houses in 1931 are difficult to obtain and the number of houses is highly correlated with population.

We calculated the relative number of damages in the mid-downstream of the Yangtze River watershed (Table S1), an area with a dense population, developed economy, and susceptibility to flooding, where data on damages (Tables S2, 3) is accessible. The area mainly covers four provinces (Fig. S8), including Hubei, Hunan, Jiangxi, and Anhui. For each of the four provinces, we obtained the damage-related data and calculated the absolute and relative numbers of damages based on the data.

Data collection and processing

Data to build the SWAT model includes soil data, land use, DEM, river network, and hydrological observations. The soil data originates from the Harmonized World Soil Database73 (FAO, 1998). Land use data from the 1990s was provided by National Tibetan Plateau Data Center74. DEM (digital-elevation model) was derived from Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM) in 2000 with 90 m spatial resolution and sampled to 600 m. Hydrological observations, derived from Bureau of Hydrology, are daily discharge over 1987–2002 (calibration) and 2008–2018 (validation) from 31 stations (Fig. S8c and Table S6). The river network used for SWAT modeling was derived from National Basic Geographic Databases at a scale of 1:4 million and includes five levels of Class I, II, III, IV, and V. Water level (of Yichang, Hankou, and Jiujiang), used for extracting discharge observations in 1931, was digitized from “river level-time curve” in “The Great Floods in Chinese History”6 (Hu et al., 1992).

Climate data during 1982–2018 to force SWAT in the ClimObs-SWAT experiment, include precipitation (from Zhao75) and temperature (from National Meteorological Information Centre; see http://data.cma.cn) with a spatial resolution of 0.5° by 0.5°, mean wind and relative humidity at surface meteorological station scale (699 stations, from National Meteorological Information Centre), and surface solar radiation downwards with a 0.25°×0.25° resolution (from ERA576). The precipitation reanalysis, used to evaluate the extreme precipitation simulation skill of NorESM, was obtained from the newest version of the Twentieth Century Reanalysis at 1.0° × 1.0° horizontal resolution and 28 vertical levels provided by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (20CRv3)29. The surface solar radiation observation of 130 stations over China from 1990 to 2014 was also obtained from National Meteorological Information Centre, to bias-correct the solar radiation data from ERA5.

The DEMs to drive the NorESM and WRF are Global 30 Arc-Second Elevation (GTOPO30)77 and Global Multi-resolution Terrain Elevation Data (GMTED2010)78, respectively. The data on socioeconomic damages (inundated farmland, damaged houses, victims, direct economic losses, and death tolls) were obtained from “The Great Flood of Chinese History”6 and “China Meteorological Disaster Dictionary”31, shown in Tables S1–3.

Daily discharges in 1931 were calculated based on the water level. For discharges at Yichang, Hankou, and Jiujiang, we first construct a relationship (presented as a transformation model) between the water level and discharge during 2009–2018, 1987–2001, and 1988–2001 (Fig. S9a–c). Secondly, we calculate the discharges in 1931 by substituting the water level into the relationship model. For discharges at Datong, which had no water level observations in 1931, we construct a relationship between the discharges of Datong and Jiujiang (the nearest station to Datong) over 1987–2001 (Fig. S9d). By substituting the estimated discharges of Jiujiang in 1931 into the best relationship model, discharges at Datong were calculated. Given the limited availability of observations, we maximize the inclusion of all available data to establish a robust relationship, despite potentially differing time ranges between stations. Solar radiation from ERA5 was bias-corrected based on the observed solar radiation through a linear model79. It involves interpolating both data into 0.25° by 0.25° grids, subsequently fitting the linear models with the two interpolated data from 1990–2014 for the specific grids, and then employing the fitted model to adjust interpolated data from ERA5 during 1982–2018 grid by grid.

Data availability

Temperature, mean wind, and relative humidity (as climate observations) are available from the National Meteorological Information Centre (http://data.cma.cn). Precipitation (from Zhao, as climate observations) is obtained from the National Tibetan Plateau Data Center at https://data.tpdc.ac.cn/. ERA5 is obtained from https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/cdsapp#!/dataset/reanalysis-era5-single-levels?tab=overview. 20CRv3 is available at https://psl.noaa.gov/data/gridded/data.20thC_ReanV3.html. Land use data from the National Tibetan Plateau Data Center can be obtained at https://data.tpdc.ac.cn/. Harmonized World Soil Database is available at https://iiasa.ac.at/models-tools-data/hwsd. SRTM is downloaded from https://csidotinfo.wordpress.com/data/srtm-90m-digital-elevation-database-v4-1/. GTOPO30 is available at https://www.usgs.gov/centers/eros/science/usgs-eros-archive-digital-elevation-global-30-arc-second-elevation-gtopo30. GMTED2010 is obtained from https://www.usgs.gov/coastal-changes-and-impacts/gmted2010. Flood simulation results (e.g., flood intensity and duration) are available at Zhang80. More model outputs can be provided upon request at lingzhang@cug.edu.cn.

Code availability

NorESM is available from https://github.com/NorESMhub/NorESM/. WRF is available from https://github.com/wrf-model/WRF. The bias-correction code is from https://github.com/btschwertfeger/BiasAdjustCXX.

References

Bertola, M. et al. Megafloods in Europe can be anticipated from observations in hydrologically similar catchments. Nat. Geosci. 16, 982–988 (2023).

Tellman, B. et al. Satellite imaging reveals increased proportion of population exposed to floods. Nature 596, 80–86 (2021).

CRED & UNDRR. Human cost of disasters. an overview of the last 20 years: 2000–2019. (UNDRR, 2020).

Courtney, C. The nature of disaster in China: the 1931 Yangzi river flood. The nature of disaster in China: the 1931 Yangzi River Flood 1–296 https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108278362 (2018).

Zhou, Y. et al. Understanding the forcing mechanisms of the 1931 summer flood along the Yangtze River, the world’s deadliest flood on record. J. Clim. 1–50 https://doi.org/10.1175/jcli-d-22-0771.1 (2023).

Mingsi, H. & Chengzheng, L. The great floods in Chinese History. (China Bookstore, Beijing, 1992).

IPCC. Climate change 2022: impacts, adaptation and vulnerability. Summary for policymakers. Contribution of working group ii to the sixth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change. In: United Nations Environment Programme UNEP (eds. H.-O. Pörtner, D.C. Roberts, M. Tignor, E.S. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, A. Alegría, M. Craig, S. Langsdorf, S. L. & V. Möller, A. Okem, B. R.) vol. AR6 551–712 (Cambridge University Press, UK and New York, 2022).

Kreibich, H. et al. The challenge of unprecedented floods and droughts in risk management. Nature 608, 80–86 (2022).

Yang, L. et al. Climate more important for chinese flood changes than reservoirs and land use. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48, e2021GL093061 (2021).

Yin, J. et al. Large increase in global storm runoff extremes driven by climate and anthropogenic changes. Nat. Commun. 9, 4389 (2018).

Blöschl et al. Changing climate both increases and decreases European river floods. Nature 573, 108–111 (2019).

Jongman, B. et al. Declining vulnerability to river floods and the global benefits of adaptation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, E2271–E2280 (2015).

Reinders, J. B. & Muñoz, S. E. Improvements to flood frequency analysis on alluvial rivers using paleoflood data. Water Resour. Res. 57, e2020WR028631 (2021).

Hosking, J. R. M. & Wallis, J. R. Paleoflood hydrology and flood frequency analysis. Water Resour. Res. 22, 543–550 (1986).

Benito, G., Brázdil, R., Herget, J. & Machado, M. J. Quantitative historical hydrology in Europe. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 19, 3517–3539 (2015).

Huo, R. et al. Flood variability in the upper Yangtze River over the last millennium—Insights from a comparison of climate-hydrological model simulated and reconstruction. Science China Earth Sciences https://doi.org/10.1007/s11430-022-1008-5 (2023).

Benito, G. & O’Connor, J. E. Quantitative Paleoflood Hydrology. Treatise Geomorphol. 9, 459–474 (2013).

Huo, R. et al. Changing flood dynamics in Norway since the last millennium and to the end of the 21st century. J. Hydrology 613, (2022).

Sheng, H. et al. Frequency and magnitude variability of Yalu River flooding: numerical analyses for the last 1000 years. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 24, 4743–4761 (2020).

Scussolini, P. et al. Global river discharge and floods in the warmer climate of the last interglacial. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e2020GL089375 (2020).

Beyer, R., Krapp, M. & Manica, A. An empirical evaluation of bias correction methods for palaeoclimate simulations. Climate 16, 1493–1508 (2020).

Lanzante, J. R., Dixon, K. W., Adams-Smith, D., Nath, M. J. & Whitlock, C. E. Evaluation of some distributional downscaling methods as applied to daily precipitation with an eye towards extremes. Int. J. Climatol. 41, 3186–3202 (2021).

Chen, J., Brissette, F. P. & Leconte, R. Coupling statistical and dynamical methods for spatial downscaling of precipitation. Clim. Change 114, 509–526 (2012).

Maraun, D. et al. Precipitation downscaling under climate change: recent developments to bridge the gap between dynamical models and the end user. Rev. Geophys. 48, 1–38 (2010).

Chen, J., Brissette, F. P. & Lucas-Picher, P. Assessing the limits of bias-correcting climate model outputs for climate change impact studies. J. Geophys. Res. 120, 1123–1136 (2015).

Zhang, B., Wang, S. & Wang, Y. Probabilistic projections of multidimensional flood risks at a convection-permitting scale. Water Resour. Res. 57, (2021).

Chen, H., Wang, S., Wang, Y. & Zhu, J. Probabilistic projections of hydrological droughts through convection-permitting climate simulations and multimodel hydrological predictions. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 125 (2020).

Li, L., Pontoppidan, M., Sobolowski, S. & Senatore, A. The impact of initial conditions on convection-permitting simulations of a flood event over complex mountainous terrain. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 24, 771–791 (2020).

Slivinski, L. C. et al. Towards a more reliable historical reanalysis: improvements for version 3 of the twentieth century reanalysis system. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 145, 2876–2908 (2019).

Ministry, C. W. R. C. of. Flood and drought disasters in the Yangtze River Basin. (China Water & Power Press, Beijing, 2002).

Kegang, W. & Yihui, D. China meteorological disaster dictionary. Comprehensive Volume. (Meteorological Publishing House, Beijing, 2008).

Qun, T. A study on relief efforts during the 1931 Anhui floods. Anhui University of Finance and Economics (2018).

Shenghong, J. J. July 1931: floods striking Nanjing City. Jiangsu Local Chron. 5, 73–74 (2016).

Zhixian, Z. A discussion on the 1931 Hankou floods-an examination based on republican era newspapers and magazines. J. Wuhan. Univ. Sci. Technol.: Soc. Sci. Ed. 16, 104–111 (2014).

Wang, X. et al. Warm advection as a cause for extreme heat event in North China. Geophys. Res. Lett. 51, e2024GL108995 (2024).

Gong, D. Y. & He, X. Z. Interdecadal change in Western Pacific Subtropical High and climatic effects. Acta Geogr. Sin. 57, 185–193 (2002).

Huang, Y., Wang, B., Li, X. & Wang, H. Changes in the influence of the western Pacific subtropical high on Asian summer monsoon rainfall in the late 1990s. Clim. Dyn. 51, 443–455 (2018).

Shen, H., He, S. & Wang, H. Effect of summer Arctic sea ice on the reverse August precipitation anomaly in Eastern China between 1998 and 2016. J. Clim. 32, 3389–3407 (2019).

Fang, M. & Li, X. Paleoclimate data assimilation: Its motivation, progress and prospects. Sci. China Earth Sci. 59, 1817–1826 (2016).

Schmidli, J., Frei, C. & Vidale, P. L. Downscaling from GCM precipitation: a benchmark for dynamical and statistical downscaling methods. Int. J. Climatol. 26, 679–689 (2006).

Yu, E., Ma, J. & Sun, J. Developing a climate prediction system over Southwest China using the 8-km weather research and forecasting (WRF) model: system design, model calibration, and performance evaluation. Weather Forecast. 37, 1703–1719 (2022).

Guevara Luna, M. A., Casallas, A., Belalcázar Cerón, L. C. & Clappier, A. Implementation and evaluation of WRF simulation over a city with complex terrain using Alos-Palsar 0.4 s topography. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 27, 37818–37838 (2020).

Schumacher, V., Fernández, A., Justino, F. & Comin, A. WRF high resolution dynamical downscaling of precipitation for the central Andes of Chile and Argentina. Front. Earth Sci. 8, 328 (2020).

Vaittinada Ayar, P. et al. Intercomparison of statistical and dynamical downscaling models under the EURO- and MED-CORDEX initiative framework: present climate evaluations. Clim. Dyn. 46, 1301–1329 (2016).

Chen, J., Brissette, F. P. & Leconte, R. Assessing regression-based statistical approaches for downscaling precipitation over North America. Hydrol. Process. 28, 3482–3504 (2014).

Guo, C. et al. Description and evaluation of NorESM1-F: a fast version of the Norwegian Earth System Model (NorESM). Geosci. Model Dev. 12, 343–362 (2019).

Li, X., Guo, C., Zhang, Z., Helge Otterä, O. & Zhang, R. PlioMIP2 simulations with NorESM-L and NorESM1-F. Climate 16, 183–197 (2020).

Skamarock, W. C. et al. A description of the advanced research WRF version 3. Tech. Rep. https://doi.org/10.5065/D6DZ069T (2008).

Ge, Q., Zhang, X. & Zheng, J. Simulated effects of vegetation increase/decrease on temperature changes from 1982 to 2000 across the Eastern China. Int. J. Climatol. 34, 187–196 (2014).

Yang, B., Zhang, Y., Qian, Y., Huang, A. & Yan, H. Calibration of a convective parameterization scheme in the WRF model and its impact on the simulation of East Asian summer monsoon precipitation. Clim. Dyn. 44, 1661–1684 (2015).

Yu, E. T. High-resolution seasonal snowfall simulation over Northeast China. Chin. Sci. Bull. 58, 1412–1419 (2013).

Arnold, J. G., Allen, P. M. & Bernhardt, G. A comprehensive surface-groundwater flow model. J. Hydrol. 142, 47–69 (1993).

Douglas-Mankin, K. R., Srinivasan, R. & Arnold, J. G. Soil and Water Assessment Tool (SWAT) model: current developments and applications. Trans. ASABE 53, 1423–1431 (2010).

Vieira, L. E. A., Solanki, S. K., Krivova, N. A. & Usoskin, I. Evolution of the solar irradiance during the Holocene. Astron. Astrophys. 531, 20 (2011).

Gao, C., Robock, A. & Ammann, C. Volcanic forcing of climate over the past 1500 years: an improved ice core-based index for climate models. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 113 (2008).

Ammann, C. M., Joos, F., Schimel, D. S., Otto-Bliesner, B. L. & Tomas, R. A. Solar influence on climate during the past millennium: Results from transient simulations with the NCAR climate system model. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 104, 3713–3718 (2007).

Li, Y., Zhang, Z. & Xu, T. Severe drought in Eastern China From 1928 To 1929. Quat. Sci. 43, 131–143 (2023).

Hong, S. & Lim, J. The WRF single-moment 6-class microphysics scheme (WSM6). J. Korean Meteorol. Soc. 42, 129–151 (2006).

Iacono, M. J. et al. Radiative forcing by long-lived greenhouse gases: calculations with the AER radiative transfer models. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 113 (2008).

Niu, G. Y. et al. The community Noah land surface model with multiparameterization options (Noah-MP): 1. Model description and evaluation with local-scale measurements. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 116 (2011).

Yang, Z. L. et al. The community Noah land surface model with multiparameterization options (Noah-MP): 2. evaluation over global river basins. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 116 (2011).

Kain, J. S. The Kain-Fritsch convective parameterization: an update. J. Appl. Meteorol. 43, 170–181 (2003).

Hong, S. Y., Noh, Y. & Dudhia, J. A new vertical diffusion package with an explicit treatment of entrainment processes. Mon. Weather Rev. 134, 2318–2341 (2006).

Yu, E., Sun, J., Chen, H. & Xiang, W. Evaluation of a high-resolution historical simulation over China: climatology and extremes. Clim. Dyn. 45, 2013–2031 (2015).

USDA, S. National engineering handbook, section 4: hydrology. In: Washington, DC 127 (U.S. Dept. of Agriculture, Soil Conservation Service, 1972).

Monteith, J. L. Evaporation and environment. The state and movement of water in living organisms. Symp. Soc. Exp. Biol. 19, 205–234 (1965).

Williams, J. R. Flood routing with variable travel time or variable storage coefficients. Trans. ASAE 12, 0100–0103 (1969).

Abbaspour, K. C. et al. Modelling hydrology and water quality in the pre-alpine/alpine Thur watershed using SWAT. J. Hydrol. 333, 413–430 (2007).

Tong, Y. et al. Bias correction of temperature and precipitation over China for RCM simulations using the QM and QDM methods. Clim. Dyn. 57, 1425–1443 (2021).

Schepsmeier, U. et al. VineCopula: statistical inference of vine copulas. R package version 1.2. (2017).

Schwarz, G. Estimating thedimension of a model. Ann. Stat. 6, 461–464 (1978).

Shukla, S. & Wood, A. W. Use of a standardized runoff index for characterizing hydrologic drought. Geophys. Res. Lett. 35, (2008).

Fao. Digital soil map of the world and derived soil properites (CD-ROM). Land and Water Digital Media Series, No 1 (1998).

Chinese Academy of Sciences Resource and Environmental Science Data Center (http://www.resdc.cn/), 111. Landuse dataset in China (1980-2015). National Tibetan Plateau Data Center (2020).

Zhao, Y., Zhu, J. & Xu, Y. Establishment and assessment of the grid precipitation datasets in China for recent 50 years. J. Meteorol. Sci. 34, 4–10 (2014).

Hersbach, H. et al. The ERA5 global reanalysis. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 146, 1999–2049. (2020).

Global 30 Arc-Second Elevation (GTOPO30). Open-File Report https://www.usgs.gov/centers/eros/science/usgs-eros-archive-digital-elevation-global-30-arc-second-elevation-gtopo30 (2018).

Danielson, J. J. & Gesch, D. B. Global multi-resolution terrain elevation data 2010 (GMTED2010). Open-File Report https://pubs.usgs.gov/publication/ofr20111073 (2011).

Zhang, L. et al. Precipitation projections using a spatiotemporally distributed method: a case study in the Poyang Lake watershed based on the MRI-CGCM3. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 23, 1649–1666 (2019).

Ling, Z. Datasets for paper “Flood modeling prior to the instrumental era reveals limited magnitude of 1931 Yangtze flood” [Data set]. Zenodo https://zenodo.org/records/14591069 (2025).

Acknowledgements

This study was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grants 42125502 and 42205057), the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (Grant 1232192), the Research Council of Norway (Hordaflom project, grant no. 269682), and the Bjerknes Centre for Climate Research (CHEX project).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.Z. developed the idea of paleoflood simulation, conceived the methodology, conducted NorESM simulation, and contributed to the editing and revision of both the paper and the responses to reviewers’ comments. L.Z. conducted SWAT simulation, performed data processing, analysis, and visualization, wrote a first draft of the paper, updated the manuscripts, and responded to reviewers’ comments. E.Y. conducted the WRF downscaling. X.C. and J.L. contributed to discharge observations on the Yangtze River. X.W. and P.K. contributed some technological help with the mechanism analysis, as well as comments and reviews. L.L. contributed to the editing and revising of the paper. The other co-authors provided comments and reviewed the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, L., Zhang, Z., Li, L. et al. Flood modeling prior to the instrumental era reveals limited magnitude of 1931 Yangtze flood. npj Clim Atmos Sci 8, 25 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-00908-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-00908-1