Abstract

A national-level afforestation plan has been announced by the Chinese government to combat global warming through carbon sequestration. However, the biophysical feedback of afforestation under future climate scenarios has not yet been assessed. Here, using the Weather Research and Forecast model (WRF) nested by the bias-corrected MPI-ESM1-2-HR model, we simulated how future afforestation regulated the land surface temperature (LST) in China. The results show that afforestation induces a significant cooling effect over the period 2041–2060 under the SSP2-4.5 scenario, in particular in the cold season. The additional cooling effect offsets about 3.69% of the projected LST increase due to global warming and even overcompensates the LST increase in southwestern China. On the diurnal cycles, afforestation induces daytime cooling effects of −0.21 °C caused by increased latent heat fluxes, while nighttime warming effects of 0.05 °C induced mainly by cloud feedback. Our findings highlight the importance of the scientific identification of afforestation areas when developing land-management strategies and biophysical feedback for climate change mitigation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Forests play a critical role in global terrestrial ecosystems by taking up atmospheric carbon dioxide1,2,3,4 and thereby afforestation has been recognized as a reasonable and effective nature-based solution to mitigate global warming5,6,7. Afforestation is thought to have numerous ecological benefits, including promoting biodiversity8, providing invaluable ecosystem services9, improving human well-being10 and cooling surface temperature7. These co-benefits motivate some international organizations and local communities to embark on ongoing widespread afforestation in the future. To achieve the Paris Climate Change Agreement target, the Bonn Challenge, the New York Declaration on Forests, and the UN Decade on Ecosystem Restoration, urgently call for the forest restoration of 350 million hectares by 2030 over the global degraded and deforested lands11.

At the national level, China has implemented considerable afforestation engineering programs (e.g., Grain for Green Program12) over the recent three decades and has been the most afforested country in the world13,14,15,16. Accordingly, these programs have increased China’s forest cover by about 24.02% up to 2022, making a significant contribution to global greening17,18,19. Recently, to address climate warming, the Chinese government has announced a target to achieve carbon neutrality before 206020,21. To this end, some new national projects for future large-scale afforestation have been proposed in succession. For example, the Action Plan for Carbon Dioxide Peaking Before 2030 attempts to increase forest cover to 25% by 203022 and the National Forest Management Planning (2016–2050) sets an afforestation target of 73.78 × 104 km2 by 2050 in China23. Such large areas of afforestation could lead to huge ecological benefits from increased carbon storage. Meanwhile, it could also modulate local and regional climate through land-atmospheric feedback.

Afforestation can alter climate by modulating the land surface energy balance and water vapour exchange, namely the biogeophysical (BGP) effect, and by modulating atmospheric CO2 concentration, namely the biogeochemical (BGC) effect24,25,26,27. The BGC effect of afforestation exerts a temperature decrease, while the globally averaged BGP effect is relatively small28. For large-scale afforestation or deforestation, the BGP effect can be as large as or even outweighs that of BGC effect28,29,30,31. The BGP effect, particularly on the land surface temperature (LST), varies in sign and magnitude between regions24. In boreal regions, afforestation can cause a warming effect through darkening the surface and absorbing more solar radiation; however, in tropical regions, the cooling effect dominates because afforestation may lead to more evapotranspiration, i.e. latent heat, and less sensible heat24,32. In temperate regions, the warming effects due to darkening surface and the cooling effects due to more evapotranspiration are comparable in strength with each other. As a result, the net effects of afforestation on LST are complex and subject to large uncertainties24. Moreover, the net effects have obvious seasonal differences. For instance, afforestation in China tends to increase the winter LST, but decrease it in other seasons33. The diurnal asymmetry induced by afforestation, cooling daytime LST but warming nighttime LST, has also been reported33,34,35. Additionally, the local BGP effects of afforestation are highly dependent on the background climate as well36. It is reported that BGP effects may be modulated by the level of global climate warming induced by CO237,38,39. It suggests that the knowledge of the BGP effects of present-day afforestation would not be appropriate under future warmer background climate. Importantly, future climate change projections mainly consider the effects of increased greenhouse gas (GHG) concentrations, but have turned a blind eye to the future afforestation-induced BGP climate feedbacks40,41. Such shortcomings limit the development of mitigation initiatives for global efforts on climate change.

The BGP effects of historical afforestation on local LST have been extensively studied through three main approaches, i.e. site observation analysis42,43, remote sensing analysis7,33,34,44, and numerical modelling45,46,47. Given the lack of observations, modelling has been an effective approach to explore the BGP effects of future afforestation on LST. The development of the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project (CMIP) provides an opportunity to project future climate change based on global climate models (GCMs)48,49,50,51,52. GCMs outputs can provide regional climate models (RCMs) with initial and lateral boundary conditions (LBCs) for the future. Such a reasonable approach has been used to study the response of future afforestation or deforestation to regional mean and extreme climate, such as in West Africa53,54,55,56, Britain57, Southern Africa58, Europe59 and Australia60. However, the main challenges of existing studies remain: climate model, LBCs quality, and forestation scenarios uncertainties. Multi-model comparisons reveal a large spread in temperature and precipitation responses to afforestation in RCMs61, deforestation62,63 and land cover change64 in GCMs. The raw GCM outputs with systematic biases are employed in the LBCs of RCMs. These GCM biases can propagate into the RCMs65, inducing incorrect future background climate. In addition, the land cover scenarios are idealistic56 and hypothetical53, and neglect the national afforestation policy constraint. The future afforestation area and extent in the real world are unlikely to be so ideally large. These limitations make it difficult to quantify future afforestation-induced land-atmospheric feedback progress.

It still remains unclear to what extent the effects and possible mechanisms of afforestation on LST in China under a future warmer background climate, oriented towards national planned afforestation policies. To address this knowledge gap, based on a recently developed future potential afforestation distribution dataset66, we conducted multi-group numerical experiments using a state-of-the-art regional climate model nested within the bias-corrected GCM. We estimated the differences between two 20-year (2041–2060) simulations (including or excluding afforestation) under the SSP2-4.5 scenario. From the viewpoint of energy balance decomposition, we analysed the dominant biophysical drivers of afforestation-induced LST changes. The comparison of LST changes including and excluding future afforestation relative to historical terms (1995–2014) was also conducted, which supported us to re-estimate projected LST changes. This study attempts to improve the in-depth understanding of the trade-offs between afforestation and temperature changes.

Results

Effects of future afforestation on land surface temperature

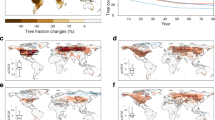

The spatial distribution of the future potential afforestation during the period 2041–2060 in China is shown in Fig. 1. Compared to the current land cover, the main changes would include grasslands (GRA) to deciduous broadleaf forests (DBF) in northern China (NC) region, woody savannas (WSA) and savannas (SAV) to evergreen broadleaf forests (EBF) in the southern China (SC) and southwestern China (SW) regions, and WSA to deciduous needleleaf forests (DNF) in the northeastern China (NE) region. Due to land cover type conversions, the land surface albedo and the leaf area index (LAI) change (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. 1). The multi-annual average LAI increased consistently by 0.394 m2 m-2 due to the conversion from GRA to DBF and by 3.159 m2 m−2 due to the conversion from WSA/SAV to EBF. However, a conversion from WSA to DNF resulted in a decrease by 0.590 m2 m−2. The impact of afforestation on albedo varies according to the specific conversion types. Following the prescribed tabular albedo values in the Noah-MP model (Supplementary Table 1), the annual albedo in the NC region is estimated to decrease by 0.132 as a result of the conversion from GRA to DBF, while the conversion from WSA/SAV to EBF induces an increase of 0.041 to 0.051.

Panels a and b describe the spatial distribution of the land use and land cover in the historical period (2020 year) and future periods (2041-2060) over the afforested areas in China, respectively. Flow diagram (c) indicates the vegetation type conversions from the historical period to future periods. The percentage is the ratio of the vegetation type area to the total afforested area (73.64 × 104 km2). Panels d and e describe the annual mean changes in leaf area index (unit: m2 m−2) and albedo (unitless) induced by afforestation, respectively. Only afforested grid cells are shown. Panel f indicates the model domain with topography (unit: m). The black box represents the five subregions: northwestern China (NW), northeastern China (NE), northern China (NC), southern China (SC), and southwestern China (SW).

Figure 2 shows that afforestation leads to a decrease in daily mean LST of 0.028 ± 0.060 °C (mean ± 1 SD, where SD is the temporal variability) over China based on the Weather Research and Forecasting (WRF) model. In terms of the diurnal effects, future afforestation would lead to a nighttime warming of 0.051 ± 0.051°C, but a daytime cooling of −0.209 ± 0.105 °C. Furthermore, the surface temperature change induced by afforestation also exhibits noticeable seasonal differences (Supplementary Figs. 2 and 3). There are slight warming effects of 0.012 ± 0.113 °C in the warm season (May–September) and significant cooling effects of −0.067 ± 0.028 °C in the cold season (October–April) over China. This result explains that the abovementioned annual mean LST decrease is dominantly derived from the cooling effect in the cold season.

It is measured by the differences between FUT_AFF and FUT_2020 experiments. Spatial pattern (a–c) indicates the annual mean values and black dots indicate the Student’s test significance at levels of 0.05. Panel d indicates the national mean LST changes induced by afforestation, and the cyan asterisks, circles, and crosses below the bar indicate the Student’s test significance at levels of 0.01, 0.05, and 0.1, respectively. The error bars represent the mean ± 1 S.D. Daytime indicates UTC06, nighttime is UTC18, and the daily is the average mean of four times (UTC00, UTC06, UTC12 and UTC18).

For each region, we find that the potential causes of daily mean temperature changes are divergent across China. In the NW region, warming effects exist in both the cold season and warm season; Meanwhile, daytime warming and nighttime warming effects exist in both seasons. Compared with each other, the nighttime warming effects in the warm season (0.125 ± 0.163 °C) are stronger than others and play a dominant role in the regional warming effects. In the NE region, significant changes induced by afforestation are found only in the annual and cold season average daytime LST, with a value of −0.096 ± 0.218 °C and −0.036 ± 0.063 °C, respectively. However, changes in the warm season and at nighttime show statistical insignificance. In the NC region, afforestation induces a net daily warming effect (less than 0.03 °C). This is attributed to afforestation-induced diurnal asymmetry changes, with decreasing daytime while increasing nighttime temperature. The obvious changes are found in the warm season, with a daytime cooling effect of −0.281 ± 0.640 °C and a nighttime warming effect of 0.164 ± 0.172 °C. Compared to other regions, the SC and SW regions feature a larger cooling effect in both cold and warm seasons. The daytime cooling effect is dominant, while the changes in nighttime mainly show a statistically insignificant weak cooling effect. Thus, the effects of future afforestation are complex and vary by region and season.

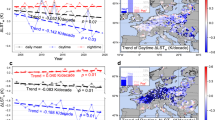

Biophysical drivers from land surface energy balance

We employed the decomposed temperature metric (DTM) approach (see Methods) to investigate the dominant biophysical factors causing the effects of afforestation on LST under future climate conditions. The effects of future afforestation can be attributed to the changes in the downward shortwave radiation (SWDN), upward shortwave radiation (SWUP), downward longwave radiation (LWDN), sensible heat (SH), latent heat (LH), and ground heat flux (G). Here, the DTM approach is applied to the four typical afforested regions (e.g., NE, NC, SC, and SW). An overview of the five main factors contributing to the LST is shown in Fig. 3. We can find that \(\Delta {{LST}}_{s}\) is comparable to \(\Delta {{LST}}_{a}\) in terms of sign and magnitude. However, the relative importance of the main factors varies between regions.

The contributions from the downward shortwave radiation (SWDN; \(\Delta {SWDN}/4\varepsilon \sigma {{LST}}_{s}^{3}\)), upward shortwave radiation (SWUP; \(-\Delta {SWUP}/4\varepsilon \sigma {{LST}}_{s}^{3}\)), downward longwave radiation (LWDN; \(\Delta {LWDN}/4\varepsilon \sigma {{LST}}_{s}^{3}\)), sensible heat (SH; \(-\Delta {SH}/4\varepsilon \sigma {{LST}}_{s}^{3}\)), latent heat (LH; \(-\Delta {LH}/4\varepsilon \sigma {{LST}}_{s}^{3}\)), and ground heat flux (G; \(-\Delta G/4\varepsilon \sigma {{LST}}_{s}^{3}\)) according to the Eq. (6). The \(\Delta {{LST}}_{s}\) indicates the sum of the five components. The \(\Delta {{LST}}_{a}\) indicates the actual temperature changes induced by afforestation (experiment FUT_AFF minus FUT_2020). Note that cyan asterisks, circles, and crosses below the bar indicate a significance level of 0.01, 0.05, and 0.1, respectively, based on the Student’s test.

In the NC region, the afforestation causes a cooling effect (−0.48 °C) in the daytime and a warming effect (0.377 °C) in the nighttime, resulting in a significant net warming effect (0.187 °C) for the annual daily mean LST. For the daytime, the SWUP effect caused by the decreased albedo due to the transition from GRA to DBF tends to increase the LST. While the SWDN, LH and SH cause a comparable cooling. The SWDN effect is related to the fact that afforestation induces an increase in low cloud cover (Supplementary Figs. 4–6), which is also supported by other researches67,68. This causes less solar radiation to reach the surface and induces a cooling effect. In addition, the LH and SH effects can be attributed to the increase in LAI and surface roughness induced by afforestation. These cooling effects are partly offset by SWUP warming effects. For the nighttime, the G effect can be explained by the increased heat release to the land surface. The LWDN effect is related to atmospheric feedback. Afforestation-induced increased nighttime low and middle cloud cover can increase the downward longwave radiation (Supplementary Figs. 4–6). Thus, the LWDN effect can additionally warm the land surface. Interestingly, the G dominates by the warming effect in the cold season, while the LWDN dominates in the warm season (Supplementary Figs. 7 and 8). The warming effect of the G and LWDN counteracts the cooling effects induced by SH.

In the SC and SW regions, both of which are located in the southern part of China, the effects of surface energy fluxes on LST are similar. The conversions from WSA/SAV to EBF lead to consistent cooling effects both during the daytime and nighttime. Taking the SW region as an example, the significant daytime cooling effect is mainly caused primarily by increases in the LH and SWUP effect, resulting from increased LAI and albedo. These cooling effects are also partly offset by the warming effects of SH and G. Compared to other terms, the effects of atmospheric feedback are slight. Although afforestation in the SW region decreases the middle and high cloud cover (Supplementary Figs. 4–6), the warming effect of SWDN is compared to the cooling effect of LWDN. As a result, afforestation leads to a net cooling effect in the daytime. In the nighttime, less G is released from the soil to the surface, and the net effect is also cooling.

In the NE region, the dominant conversion is from WSA to DNF, leading to an increase in the surface albedo. Thereby, the SWUP effect is negative and, hence, causes a cooling effect in the daytime. However, the increased SWDN causes a warming effect due to reduced low and middle cloud cover. Meanwhile, the LH and SH fluxes also decrease, and the warming effects offset the cooling effect of SWUP. As a result, afforestation causes a net cooling effect of −0.183 °C. In the nighttime, keeping similar to the NC region, G releases the stored heat in the daytime to the land surface, dominating the nighttime net warming effect of 0.07 °C. The warming effect dominated by G is mostly in the warm season. In contrast, in the cold season, afforestation induces the nighttime net cooling effect, which is dominated by the SH effect due to the low G.

Implications for land surface temperature projection

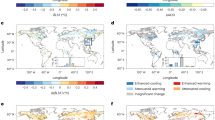

To highlight the importance of afforestation-induced effects, we re-estimated the changes in the projected LST (Fig. 4, Supplementary Figs. 9 and 10). We compared the regional LST changes caused by global warming due to increased GHG concentration (hereafter \({\Delta {LST}}_{{ssp}245}\)) with the regional LST changes induced by the BGP effects of afforestation (hereafter \({\Delta {LST}}_{{aff}}\)). The \({\Delta {LST}}_{{ssp}245}\) is defined as the differences between LST in 2041−2060 and the historical period (1995−2014) under the SSP2-4.5 scenario. The sum of \({\Delta {LST}}_{{ssp}245}\) and \({\Delta {LST}}_{{aff}}\) could be treated as net LST changes (hereafter \({\Delta {LST}}_{{ssp}245+{aff}}\)) since there will be not only changes in GHG concentration but also changes in land cover in the future.

Panels a–c indicate the changes in the projected LST under the SSP2-4.5 scenario relative to the historical periods (1995–2014). It is measured by the differences between the FUT_2001 and HIS_MPI experiments. Panels d–f indicate the changes in the projected LST after considering afforestation during 2041–2060 under the SSP2-4.5 scenario relative to the historical periods. The black dots of panels a–f indicate the Student’s test significance at levels of 0.05. Comparison of panels a–c and d–f reveals the relative magnitude of the impact of future afforestation in relation to future global warming. Panel g indicates the comparison of regionally averaged LST changes due to future global warming, future afforestation, and net effects. Note that the cyan asterisks, circles, and crosses below the bar indicate the Student’s test significance at levels of 0.01, 0.05, and 0.1, respectively.

As shown in Fig. 4, afforestation-induced regional \({\Delta {LST}}_{{aff}}\) could be comparable to the \({\Delta {LST}}_{{ssp}245}\) caused by global warming. The annual daily mean \({\Delta {LST}}_{{ssp}245}\) is 0.756 °C and \({\Delta {LST}}_{{aff}}\) is −0.028 °C; thus, combining the effects of global warming and afforestation, the net \({\Delta {LST}}_{{ssp}245+{aff}}\) is 0.728 °C in China. The afforestation-induced cooling effect offsets about 3.69% (\({\Delta {LST}}_{{aff}}\)/\({\Delta {LST}}_{{ssp}245}\)) of the regional response to GHG-induced global warming. Thereby, future afforestation weakens the regional warming. For the annual daytime, the offsetting increases up to 17.61%. However, for the annual nighttime, warming effects induced by afforestation enhance the projected LST warming effect of 6.07%.

Furthermore, the contribution of afforestation to regional warming varies with regions. In the NW region, the warming effect induced by afforestation is 0.069 °C, which is equivalent to 7.63% of \({\Delta {LST}}_{{ssp}245}\). In the NC region, the nighttime \({\Delta {LST}}_{{aff}}\) in the warm season is also positive, keeping the same sign with \({\Delta {LST}}_{{ssp}245}\), accounting for 20.38% of \({\Delta {LST}}_{{ssp}245}\). The regional warming of \({\Delta {LST}}_{{ssp}245+{aff}}\) would be larger than \({\Delta {LST}}_{{ssp}245}\). Therefore, future afforestation leads to additional and much stronger regional warming effects.

However, afforestation-induced LST changes are estimated to compensate the global warming signal. In the SW and SC regions, the effects of afforestation are cooling effects, thereby alleviating the projected regional warming under the SSP2-4.5 scenario. For example, during the warm season, the \({\Delta {LST}}_{{aff}}\) offsets the daily mean \({\Delta {LST}}_{{ssp}245}\) by 20.71% for SC and 44.55% for SW, respectively. It is noteworthy that the cooling effect of daytime \({\Delta {LST}}_{{aff}}\) is stronger than the warming effect of \({\Delta {LST}}_{{ssp}245}\) in the SW region. For example, the annual daytime \({\Delta {LST}}_{{ssp}245}\) is 0.496 °C, and the \({\Delta {LST}}_{{aff}}\) reaches up to −1.263 °C; thus, the net effect of \({\Delta {LST}}_{{ssp}245+{aff}}\) is a cooling effect of −0.767 °C. Therefore, future afforestation can mitigate the regional warming due to global warming and even overcompensate the LST increase, inducing a reversal LST projection. It reminds us that biophysical feedback from future afforestation related to national land management policies should be considered when projecting climate change.

Discussion

This study investigated the responses of LST to afforestation and possible biophysical drivers under a warmer background climate and re-estimated the changes in the projected LST through climate modelling. In comparison to existing studies on future land use and land cover change on temperature in China (e.g., refs. 69,70), inconsistent temperature response exists in southern China. The possible reason mainly sources from future land use scenarios. The present studies used a land-use harmonization (LUH) dataset recommended by the CMIP, which ignored the land use change induced by national policies. The afforestation scenario in this study was produced by considering both national afforestation plans and the future climatological forest suitability (see Methods for more details). Thereby, it represents a more realistic afforestation scenario, thus the climate feedback is more reliable for developing climate mitigation strategies.

Our findings highlighted the importance that projected temperature changes should take into account future land use/cover changes (LUCC) induced by national climate policy frameworks and their feedback on local climate. Current projected future climate change mainly employs the Representative Concentration Pathways (RCP) and Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSP) scenarios related to GHG concentrations based on GCMs (e.g., CMIP6), but has turned a blind eye to the national and regional policies related to LUCC-induced BGP climate feedbacks so far40. However, the response of the future LUCC can alter regional projected climate change signal and magnitude. Previous studies have found that the projected local temperature over Australia and China can induce a reduction of more than 20% in the rate of warming under GHG concentration increase as a result of LUCC60,70. In addition to these similar results in this study, we additionally found that future LUCC, referring to the afforestation, could even overcompensate the temperature increase, and induce an opposite projected temperature change signal. Such reversal phenomenon has also been investigated in studies on the effects of future afforestation on precipitation in Europe59,71. Thus, future LUCC feedbacks are complicated and divergent. These results emphasise that it is essential to consider the interaction between LUCC and regional climate in the land management planning program. Otherwise, it may be difficult to develop mitigation strategies to combat global warming and assess potential risks related to climate change.

Afforestation can affect not only the afforested-region LST but also the surrounding areas in this study. It is well-known that afforestation can affect temperature through local and nonlocal BGP effects62. The local effects arise mainly through a redistribution of heat between the land surface and the atmosphere, while the nonlocal effects arise mainly through temperature and moisture advection as well as changes in atmospheric circulation and cloud feedbacks72. Historical afforestation or deforestation-induced nonlocal effects can be comparable to even greater than local effects to some extent73,74,75,76. In this study, we only examined the total effects (local plus nonlocal effects), and did not separate them. Winckler et al.75 used a “checkerboard” approach to isolate the local and nonlocal effects of deforestation based on a global climate model. Following this approach, we further analysed the local and nonlocal effects of future afforestation on LST (Supplementary Fig. 11). We find that nonlocal effects induced by afforestation cool Northeast China in the warm season. This could be explained by the increase in the precipitation, which favours the cooling effects of latent heat (Supplementary Fig. 12). We also find that the non-local effects dominate the regional warming, especially in arid northwest China where almost no afforestation has been implemented in this region. To explore quantitatively the nonlocal effects of afforestation on LST in the NW region, we used the DTM approach to analyse the attribution (Supplementary Fig. 13). We find that the cloud feedback dominated the daytime and nighttime warming effect. The main reason is that afforestation-induced increased middle and high cloud cover can increase the downward longwave radiation (Supplementary Figs. 4–6). Thus, the LWDN effect can additionally warm the land surface. The warming effect is greater at nighttime than daytime. At daytime, afforestation induces an increase in low cloud cover, which causes less solar radiation to reach the surface. Thus, the SWDN effects induce a cooling effect, which partly offsets the LWDN warming effects. The warming extent is less than nighttime. It calls for a consideration of non-local effects when it comes to overall assessments of the climate impacts of land-based mitigation.

Notwithstanding the critical implications, there are a few limitations and caveats to this study. First, we used only one set of GCM to nest the WRF model due to the limited computational cost. The optimal GCM selection and correction are expected to be better for reducing WRF simulation uncertainties. Meanwhile, this study focuses on climatology mean value of 2041–2060 rather than individual yearly climate. The analysis methodology is also better for reducing results uncertainties. However, previous multi-model comparison studies reveal a large spread in BGP responses to historical land cover change in climate model61,62,63,64. The possible sources of model uncertainty mainly focus on the differences in the land surface process representation, cloud cover feedbacks, model physical processes and parameterizations, and the response of atmospheric circulation61,77,78. It is valuable to use multiple GCM nested with the RCM to force the WRF model to pursue more robust results56,70. Therefore, there is a need for more studies on ensemble simulation to make the results more robust for policymakers. Second, the WRF model generally underestimates the LST in China, as in previous studies79,80,81. The inherent simulated cold bias in models has been widely discussed for a long time. To date, the cold bias could be partly attributed to the poor performance of the climate model in simulating the cloud-radiation and snow-albedo feedback79, atmospheric pollutants progress deficient82, observation sites mostly over flat terrain or in valleys, which leads to higher temperature83. For example, cloud cover is underestimated in the models, leading to less incoming longwave radiation79. Simulated more snow cover also contributes to the cold biases due to the overestimated surface albedo80. These can cause uncertainties in the effects of future afforestation on LST in this study, especially in the cold season. Thus, improving the parameterizations of cloud and snow albedo can reduce the simulated cold biases81, which is beneficial for obtaining a more robust afforestation-climate feedback. Third, due to the high computational cost, we used the horizontal resolution of 25 km in the WRF model, which hardly reflected finer land-atmosphere feedback progresses, such as complex terrain regions. Kilometre-scale convection-permitting models (CPM) (below 4 km grid-spacing) don’t depend on convection parameterisation schemes and thereby can reproduce the deep convection well84,85,86. The following research can apply the regional climate modelling using CPM to land-atmospheric feedback to reduce model uncertainties. Finally, the BGC process of afforestation is not considered in this study. Climate change mitigation policy-making needs to consider net effects (including BGP and BGC). The afforestation-induced net mitigation benefits are still controversial due to uncertainties in the responses of the global carbon cycle to anthropogenic land-use change87,88,89. The cooling effects induced by afforestation may be amplified under the lower aerosol pollution90. Therefore, further research on the afforestation feedback needs to comprehensively consider the condition of air pollution and carbon sequestration in the meantime.

In summary, we found that the biophysical feedback induced by future afforestation could cool the LST in China. In the comparison of the projected changes in LST from climate change and afforestation, the combined effect considerably altered the magnitude and signal of the projected LST from climate change by referring to 1995–2014. Hence, this study highlights the importance of biophysical feedback from land-cover changes induced by national land-management policies in the climate projection. Its potential implication is of the greatest significance for policymakers to develop more reasonable climate change adaptation and mitigation strategies. In addition to affecting climate mean states, afforestation-induced biophysical feedback can also influence extreme weather and climate events, such as enhancing extreme precipitation in West Africa56, reducing Europe’s cyclone intensity91, and increasing drought frequencies in Southern Africa58. Further work should focus on the trade-offs between future afforestation and associated climate risks.

Methods

Satellite-based LST data

This study used a monthly land surface temperature (LST) dataset92, which has a spatial resolution of 5600 m and covers a period from 2003 to 2014. It was reconstructed by establishing a regression analysis model combining Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) data and ground meteorological station measurements. There were no missing values, and the influence of cloud coverage was reduced. In comparison to the raw MODIS LST data, the combined dataset had higher accuracy. The datasets have been widely applied as a reference to evaluate climate models93,94. Here, we also used it to evaluate the performance of WRF modelling.

Land cover scenarios

Three land cover datasets were used in this study: the default land cover in WRF, the MCD12Q1 land cover dataset for the year 2020, and the future afforestation scenario land cover dataset. The default land cover in WRF was derived from the MODIS land cover type products for the year 2001. However, it has failed to portray the accurate land surface characteristics in China95,96. Therefore, the latest MODIS land cover type dataset (MCD12Q1) for the year 2020, with a spatial resolution of 500 m and temporal resolution of the annual interval, was updated and used in this study97,98. This product provided a 17-class International Geosphere-Biosphere Programme (IGBP) classification scheme99 and could match the first 17 land use types with the WRF default well. The MCD12Q1 products had high quality, with an overall accuracy of about 75% globally100, and were widely used in climate modelling studies as lower boundary conditions101,102,103,104.

The future afforestation scenario data was derived from Song et al.66, which mapped the distribution of future potential afforestation areas in China. Compared to the previous idealistic and hypothetical afforestation scenarios (e.g., refs. 53,54,55,56), the land cover dataset under the afforestation scenarios was characterised by plausible afforestation scenarios due to considering the effects of national afforestation policy and climate change effects. Specifically, the national afforestation policy from the National Forest Management Planning (2016–2050) (NFMP) released by the State Forestry Administration of China23 provided the future afforestation area of each province in China. The Holdridge life zone model was applied to investigate the impact of future climate change on the potential forest distribution. In the dataset, the total afforestation area in China is 73.64 × 104 km2 during the period 2041–2060 under the SSP2-4.5 scenario, which meets the requirements of the NFMP (73.78 × 104 km2). The spatial resolution is 25 km and can be matched with the WRF model well. The dataset ensures that the afforestation area of each province is consistent with the NFMP, and the afforestation extent matches the climatic suitability of the forest. Therefore, the future afforestation scenario is closer to the real world.

Initial and lateral boundary conditions

We used two initial and lateral boundary conditions (LBCs) datasets (ERA5 reanalysis and MPI-ESM1-2-HR model) to force the WRF model. The ERA5 reanalysis dataset, developed by the European Centre for Medium-range Weather Forecast (ECMWF)105, has been widely applied in the historical WRF simulation. The required variables include five atmospheric fields (temperature, geopotential height, specific humidity, zonal and meridional wind) from 1000hPa to 50hPa, a total 28 vertical levels, and eleven surface fields (surface temperature, sea-surface temperature, surface pressure, sea ice cover, sea-level pressure, soil temperature, soil moisture, near-surface temperature, relative humidity, zonal and meridional wind), with a spatial resolution of 1.0° × 1.0° and 6-hourly intervals.

The 6-hourly MPI-ESM1-2-HR model output data from the Max Planck Institute, provided by the CMIP6 model, was used to drive the WRF model as LBCs for future numerical simulations. The introduction and configuration of the MPI-ESM1-2-HR model in detail can be found in reference106. Compared to other CMIP6 models, the MPI-ESM1-2-HR model shows a better performance in simulating the five WRF-required atmospheric fields and has been recommended for dynamical downscaling in China107. For single variable simulations (i.e., temperature and precipitation) and large-scale circulation fields, the MPI-ESM1-2-HR model also represents higher skill as well108,109,110. Thus, the MPI-ESM1-2-HR model and its latest version (MPI-ESM-MR) have been widely applied to future regional climate modelling as the LBCs111,112,113,114,115,116. The atmospheric and surface fields associated with the MPI-ESM1-2-HR model are consistent with the ERA5 reanalysis. We interpolated the raw MPI-ESM1-2-HR model with a spatial resolution of 0.9375° × 0.9375° to 1.0° × 1.0° to match ERA5 based on the bilinear interpolation approach.

For the two LBCs, historical simulation focused on the period 1994−2014, and the period 2040−2060 was considered the future projection simulation period. The SSP2-4.5 scenario in this study is chosen because it reflects a moderate socioeconomic development path, combined with the radiative forcing peaking at 4.5 W m−2 by 2100117. In this scenario, countries maintain the current development trend, consistent with a future with relatively ambitious emissions reductions but where social, economic, and technological trends don’t deviate significantly from historical patterns118. Thus, the SSP2-4.5 scenario is close to the national current pledges and a relatively realistic global climate scenario. Although the MPI-ESM1-2-HR model performs relatively better than other GCMs, it still exists biases. Therefore, we corrected the MPI-ESM1-2-HR data considering climate mean and variance by applying the bias correction method from Song et al.66. The ERA5 data as a reference was used to correct the MPI-ESM1-2-HR model. The brief descriptions of bias correction are as follows:

Where, \({H}_{{cor}}\) and \({F}_{{cor}}\) are bias-corrected 6-hourly MPI-ESM1-2-HR models over the historical baseline (1994−2014) and the future period (2040−2060), respectively. \({D}_{{GCM\_H}}\) and \({D}_{{GCM\_F}}\) indicate anomaly. \({{SD}}_{{ERA}}\) and \({{SD}}_{{GCM}}\) indicate the standard deviation of the ERA5 and MPI-ESM1-2-HR simulations during the historical period, respectively. \(\frac{{{SD}}_{{ERA}}}{{{SD}}_{{GCM}}}\) indicates the variance-adjusted term. \({M}_{{ERA}}\) represent the climatological mean of ERA5 data and \({(M}_{{GCM\_F}}-{M}_{{GCM\_H}})\) indicates the mean future climate change based on MPI-ESM1-2-HR simulations. Thus, the 6-hourly means and variances of the bias-corrected MPI-ESM1-2-HR model are consistent with the ERA5 reanalysis. This bias-corrected approach was applied to all atmospheric and surface fields.

Model description

The Weather Research and Forecasting (WRF) model (version 4.2)119, a coupled land-atmosphere regional climate model, was used to investigate the effects of afforestation on LST. The WRF model was developed jointly by multiple institutions (e.g., the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration) and universities (e.g., the University of Oklahoma). As a state-of-the-art, non-hydrostatic, and open-source model, the WRF model has been widely used to study regional climate simulations120,121,122,123 and land-atmosphere interactions124,125, such as studies related to the climate effects of historical afforestation45. Specifically, the WRF model can show better performance in simulating the historical climatology of LST over China compared to the observation45.

The model domain covered the entire China and its surrounding area (Fig. 1f). The simulation configuration included a horizontal resolution of 25 km, 40 levels in the vertical direction, 289 and 212 grids in the east-west and south-north directions, respectively. The physics parameterisation scheme included the WSM 3-class simple ice microphysics scheme126, the CAM longwave and shortwave radiation scheme127, the Grell-Devenyi cumulus convective scheme128, the Noah-MP Land surface scheme129, and the YSU boundary layer scheme130. The simulation configuration and parameterisation scheme of the WRF model showed a better performance in China131. This study investigated the performance of the WRF model in simulating the land surface temperature during the historical period (1995−2014) in China (Supplementary Text 1). The result showed that the WRF model nested with the bias-corrected MPI-ESM1-2-HR model could reasonably reproduce the spatial pattern of climatology relative to the reference observations (Supplementary Fig. 14). We also corrected the future precipitation in the FUT_2020 and FUT_AFF experiment based on the quantile mapping (QM) method (Supplemental Text 2). The results show that the QM bias-corrected precipitation (WRF-QM) can obviously reduce the historical simulation bias (Supplementary Figs. 15, 16), and the changes in the future afforestation-induced precipitation are compared by the WRF-raw and WRF-QM (Supplementary Fig. 12).

Experimental design

We designed five 21-year numerical experiments to investigate the biophysical effects of future afforestation using the WRF model (Supplementary Table 2). The historical simulation ran from 1994 to 2014 for two groups of historical experiments (HIS_ERA and HIS_MPI). The HIS_ERA experiments applied the default land cover maps in 2001 and the EAR5 analysis dataset as LBCs. The HIS_MPI experiments kept the same configuration as the HIS_ERA experiments, but the LBCs were set to the bias-corrected MPI-ESM1-2-HR model. The future simulation ran from 2040 to 2060 for three groups of future experiments (FUT_2001, FUT_2020 and FUT_AFF). The FUT_2001 and FUT_2020 experiments used the default and 2020 MCD12Q1 land cover, respectively. In the future afforestation (FUT_AFF) experiment, the land cover was the future afforestation scenario, and other settings were consistent with the FUT_2020. For each simulation, the first year was discarded due to a spin-up time. The remaining 20-year simulations (1995−2014 and 2041−2060) were analysed further.

We analysed the HIS_MPI and HIS_ERA experiments to the performance of the simulations relative to the observations. The difference between HIS_MPI and HIS_ERA experiments represents the bias derived from LBCs because the WRF inherent bias is the same. The difference between FUT_AFF and FUT_2020 (FUT_AFF minus FUT_2020) could be attributed to changes in LST due to future afforestation (\({\Delta {LST}}_{{aff}}\)). The difference between FUT_2001 and HIS_MPI (FUT_2001 minus HIS_MPI) could project the future change in LST under the SSP2-4.5 scenario relative to the historical period (\({\Delta {LST}}_{{ssp}245}\)), which represents the effects of global warming due to increased GHG concentration. Meanwhile, we also re-estimated the projected LST when considering future afforestation (\({\Delta {LST}}_{{ssp}245+{aff}}\), the sum of \({\Delta {LST}}_{{ssp}245}\) and \({\Delta {LST}}_{{aff}}\)). The Student’s t-test was used to test the statistical significance of the differences at a level of 0.01, 0.05, and 0.1.

Decomposition of the biophysical land surface temperature

Afforestation can change the surface energy balance and thus affect regional temperature. To investigate the mechanisms, we used the decomposed temperature metric (DTM) approach to quantify which term of the surface energy flux mainly accounts for the changes in the surface temperature. The DTM approach, proposed by Juang42, has been successfully applied to the attribution analysis of the temperature response to the surface energy budget62,132,133,134. Here, the surface energy balance is theoretically expressed as:

Where, \({SWDN}\) and \({SWUP}\) represent the downward shortwave radiation and upward shortwave radiation, respectively. \({LWDN}\) and \({LWUP}\) indicate the downward longwave radiation and upward longwave radiation, respectively. \({SH}\), \({LH}\), and \(G\) present the sensible heat, latent heat, and ground heat fluxes, respectively. \({LWUP}\) can also be obtained by the Stefan–Boltzmann law:

Where, \({{LST}}_{s}\) stands for the reference surface temperature. \(\varepsilon\) is the surface emissivity. \(\sigma\), the Stefan–Boltzmann constant, is equal to \(5.67\times {10}^{-8}W{m}^{-2}{K}^{-4}\). Here, we can combine Eq. (3) and Eq. (4) as:

Then, by applying the Taylor series expansion, we obtain the surface temperature changes induced by afforestation as follows:

Here, the \(\Delta\) indicates the changes between the sensitivity and control experiments (FUT_AFF minus FUT_2020). Thus, \(\Delta {{LST}}_{s}\) can be obtained by calculating the sum of five terms of Eq. (6), and the actual surface temperature change (\(\Delta {LS}{T}_{a}\)) induced by afforestation can be simulated between these two experiments. Note that \(\Delta {{LST}}_{s}\) and \(\Delta {LS}{T}_{a}\) have slight differences, which have also found in previous studies132,133,135. It indicates the errors of the DTM approach136. These errors from high-order derivatives137, and anthropogenic heat fluxes138 are difficult to quantify. Despite the errors, this DTM approach is mainly applied to quantify the relative contribution of individual surface energy budget component changes induced by afforestation45. In addition, this approach is closely related to surface energy changes; thus, it can only reflect the local effects of afforestation signals74.

Data availability

All data used in this study are publicly available. The MPI-ESM1-2-HR model data from CMIP6 can be accessed at https://esgf.nci.org.au/search/cmip6-nci/. The ERA5 reanalysis data can be accessed from https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/cdsapp#!/search?type=dataset. The MCD12Q1 land use data is freely available via https://e4ftl01.cr.usgs.gov/MOTA/MCD12Q1.061/. The future afforestation scenario and land surface temperature data in China are available through Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10900150 and https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3528024, respectively.

Code availability

All code is available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Dixon, R. K. et al. Carbon Pools and Flux of Global Forest Ecosystems. Science 263, 185–190 (1994).

Goodale, C. L. et al. Forest Carbon Sinks in the Northern Hemisphere. Ecol. Appl. 12, 891–899 (2002).

Erb, K.-H. et al. Bias in the attribution of forest carbon sinks. Nat. Clim. Chang. 3, 854–856 (2013).

Gundersen, P. et al. Old-growth forest carbon sinks overestimated. Nature 591, E21–E23 (2021).

Fawzy, S., Osman, A. I., Doran, J. & Rooney, D. W. Strategies for mitigation of climate change: a review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 18, 2069–2094 (2020).

Yue, X., Zhang, T. & Shao, C. Afforestation increases ecosystem productivity and carbon storage in China during the 2000s. Agric. For. Meteorol. 296, 108227 (2021).

Peng, S.-S. et al. Afforestation in China cools local land surface temperature. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 111, 2915–2919 (2014).

Wang, C., Zhang, W., Li, X. & Wu, J. A global meta-analysis of the impacts of tree plantations on biodiversity. Global. Ecol. Biogeogr. 31, 576–587 (2022).

Brockerhoff, E. G. et al. Forest biodiversity, ecosystem functioning and the provision of ecosystem services. Biodivers. Conserv. 26, 3005–3035 (2017).

Jones, B. A. Planting urban trees to improve quality of life? The life satisfaction impacts of urban afforestation. Forest Policy Econ. 125, 102408 (2021).

Stanturf, J. A. & Mansourian, S. Forest landscape restoration: state of play. R. Soc. Open Sci. 7, 201218 (2020).

Xiao, J. Satellite evidence for significant biophysical consequences of the “Grain for Green” Program on the Loess Plateau in China. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 119, 2261–2275 (2014).

Zheng, L., Lu, J., Liu, H., Chen, X. & Yesou, H. Evidence of vegetation greening benefitting from the afforestation initiatives in China. Geo Spat. Inf. Sci. 0, 1–20 (2023).

Zhang, P. et al. China’s forest policy for the 21st century. Science 288, 2135–2136 (2000).

Cao, S., Chen, L. & Yu, X. Impact of China’s Grain for Green Project on the landscape of vulnerable arid and semi-arid agricultural regions: a case study in northern Shaanxi Province. J. Appl. Ecol. 46, 536–543 (2009).

Zhang, X., Zhang, Z. & Song, S. Modulation of vegetation restoration on outdoor thermal comfort over the Loess Plateau, China from 1982 to 2015. Environ. Res. Commun. 3, 015002 (2021).

Zhang, Y. et al. Multiple afforestation programs accelerate the greenness in the ‘Three North’ region of China from 1982 to 2013. Ecol. Indic. 61, 404–412 (2016).

Piao, S. et al. Characteristics, drivers and feedbacks of global greening. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 1, 14–27 (2020).

Chen, C. et al. China and India lead in greening of the world through land-use management. Nat. Sustain. 2, 122–129 (2019).

Liu, Z. et al. Challenges and opportunities for carbon neutrality in China. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 3, 141–155 (2022).

Zhao, X., Ma, X., Chen, B., Shang, Y. & Song, M. Challenges toward carbon neutrality in China: Strategies and countermeasures. Resour. Conserv. Recy. 176, 105959 (2022).

State Council of China. Action Plan for Carbon Dioxide Peaking Before 2030, https://www.gov.cn/gongbao/content/2021/content_5649731.htm?eqid=e82790c90001dc23000000036459fff2 (2021).

State Forestry Administration of China.: National Forest Management Planning (2016–2050), https://www.gov.cn/xinwen/201607/28/content_5095504.htm?eqid=f495541b0003bd9a00000002648fc315 (2016).

Bonan, G. B. Forests and Climate Change: Forcings, Feedbacks, and the Climate Benefits of Forests. Science 320, 1444–1449 (2008).

Rohatyn, S., Yakir, D., Rotenberg, E. & Carmel, Y. Limited climate change mitigation potential through forestation of the vast dryland regions. Science 377, 1436–1439 (2022).

Rohatyn, S., Rotenberg, E., Tatarinov, F., Carmel, Y. & Yakir, D. Large variations in afforestation-related climate cooling and warming effects across short distances. Commun. Earth Environ. 4, 1–10 (2023).

Devaraju, N., Bala, G. & Nemani, R. Modelling the influence of land-use changes on biophysical and biochemical interactions at regional and global scales: Biophysical and biochemical interactions. Plant Cell Environ 38, 1931–1946 (2015).

Arora, V. K. & Montenegro, A. Small temperature benefits provided by realistic afforestation efforts. Nat. Geosci. 4, 514–518 (2011).

Claussen, M., Brovkin, V. & Ganopolski, A. Biogeophysical versus biogeochemical feedbacks of large‐scale land cover change. Geophys. Res. Lett. 28, 1011–1014 (2001).

Georgescu, M., Lobell, D. B. & Field, C. B. Direct climate effects of perennial bioenergy crops in the United States. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 108, 4307–4312 (2011).

Loarie, S. R., Lobell, D. B., Asner, G. P., Mu, Q. & Field, C. B. Direct impacts on local climate of sugar-cane expansion in Brazil. Nat. Clim. Change 1, 105–109 (2011).

Alkama, R. & Cescatti, A. Biophysical climate impacts of recent changes in global forest cover. Science 351, 600–604 (2016).

Ma, W., Jia, G. & Zhang, A. Multiple satellite-based analysis reveals complex climate effects of temperate forests and related energy budget. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 122, 3806–3820 (2017).

Yuan, G. et al. Impacts of afforestation on land surface temperature in different regions of China. Agric. For. Meteorol. 318, 108901 (2022).

Wang, L. et al. Response of Surface Temperature to Afforestation in the Kubuqi Desert, Inner Mongolia. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 123, 948–964 (2018).

Pitman, A. J. et al. Importance of background climate in determining impact of land-cover change on regional climate. Nat. Clim. Change 1, 472–475 (2011).

Hua, W. & Chen, H. Recognition of climatic effects of land use/land cover change under global warming. Chin. Sci. Bull. 58, 3852–3858 (2013).

Li, Y. et al. The role of spatial scale and background climate in the latitudinal temperature response to deforestation. Earth Syst. Dynam. 7, 167–181 (2016).

Zhang, X., Chen, J. & Song, S. Divergent impacts of land use/cover change on summer precipitation in eastern China from 1980 to 2000. Int. J. Climatol. 41, 2360–2374 (2021).

Mahmood, R., Pielke, R. A. & McAlpine, C. A. Climate-Relevant Land Use and Land Cover Change Policies. B. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 97, 195–202 (2016).

O’Neill, B. C. et al. Achievements and needs for the climate change scenario framework. Nat. Clim. Chang. 10, 1074–1084 (2020).

Juang, J.-Y., Katul, G., Siqueira, M., Stoy, P. & Novick, K. Separating the effects of albedo from eco-physiological changes on surface temperature along a successional chronosequence in the southeastern United States. Geophys. Res. Lett. 34, L21408 (2007).

Lee, X. et al. Observed increase in local cooling effect of deforestation at higher latitudes. Nature 479, 384–387 (2011).

Shen, W. et al. Biophysical Effects of Afforestation on Land Surface Temperature in Guangdong Province, Southern China. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 127, e2022JG006913 (2022).

Chen, C. et al. The Biophysical Impacts of Idealized Afforestation on Surface Temperature in China: Local and Nonlocal Effects. J. Climate 35, 4233–4252 (2022).

Ge, J. et al. Deforestation intensifies daily temperature variability in the northern extratropics. Nat. Commun. 13, 5955 (2022).

Li, Y., Piao, S., Chen, A., Ciais, P. & Li, L. Z. X. Local and teleconnected temperature effects of afforestation and vegetation greening in China. Nat. Sci. Rev. 7, 897–912 (2020).

Smith, D. M. et al. Improved Surface Temperature Prediction for the Coming Decade from a Global Climate Model. Science 317, 796–799 (2007).

Chen, Z. et al. Global Land Monsoon Precipitation Changes in CMIP6 Projections. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e2019GL086902 (2020).

Xie, W., Wang, S. & Yan, X. Evaluation and Projection of Diurnal Temperature Range in Maize Cultivation Areas in China Based on CMIP6 Models. Sustainability 14, 1660 (2022).

Song, S. & Yan, X. Projected changes and uncertainty in cold surges over northern China using the CMIP6 weighted multi-model ensemble. Atmos. Res. 278, 106334 (2022).

Hosseinzadehtalaei, P., Termonia, P. & Tabari, H. Projected changes in compound hot-dry events depend on the dry indicator considered. Commun. Earth Environ. 5, 1–10 (2024).

Abiodun, B. J., Adeyewa, Z. D., Oguntunde, P. G., Salami, A. T. & Ajayi, V. O. Modeling the impacts of reforestation on future climate in West Africa. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 110, 77–96 (2012).

Diasso, U. & Abiodun, B. J. Future impacts of global warming and reforestation on drought patterns over West Africa. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 133, 647–662 (2018).

Odoulami, R. C., Abiodun, B. J., Ajayi, A. E., Diasso, U. J. & Mounkaila Saley, M. Potential impacts of forestation on heatwaves over West Africa in the future. Ecol. Eng. 102, 546–556 (2017).

Odoulami, R. C., Abiodun, B. J. & Ajayi, A. E. Modelling the potential impacts of afforestation on extreme precipitation over West Africa. Clim. Dyn. 52, 2185–2198 (2019).

Buechel, M. E. H., Slater, L. & Dadson, S. Afforestation impacts on terrestrial hydrology insignificant compared to climate change in Great Britain. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 28, 2081–2105 (2024).

Naik, M. & Abiodun, B. J. Potential impacts of forestation on future climate change in Southern Africa. Int. J. Climatol. 36, 4560–4576 (2016).

Meier, R. et al. Empirical estimate of forestation-induced precipitation changes in Europe. Nat. Geosci. 14, 473–478 (2021).

Syktus, J. I. & McAlpine, C. A. More than carbon sequestration: Biophysical climate benefits of restored savanna woodlands. Sci. Rep. 6, 29194 (2016).

Davin, E. L. et al. Biogeophysical impacts of forestation in Europe: first results from the LUCAS (Land Use and Climate Across Scales) regional climate model intercomparison. Earth Syst. Dynam. 11, 183–200 (2020).

Boysen, L. R. et al. Global climate response to idealized deforestation in CMIP6 models. Biogeosciences 17, 5615–5638 (2020).

Liu, S. et al. Local and non‐local biophysical impacts of deforestation on global temperature during boreal summer: CMIP6‐lumip multimodel analysis. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 128, e2022JD038229 (2023).

Pitman, A. J. et al. Uncertainties in climate responses to past land cover change: First results from the LUCID intercomparison study. Geophys. Res. Lett. 36, L14814 (2009).

Kebe, I. et al. Impact of GCM boundary forcing on regional climate modeling of West African summer monsoon precipitation and circulation features. Clim. Dyn. 48, 1503–1516 (2017).

Song, S., Zhang, X. & Yan, X. Mapping the future afforestation distribution of China constrained by a national afforestation plan and climate change. Biogeosciences 21, 2839–2858 (2024).

Duveiller, G. et al. Revealing the widespread potential of forests to increase low level cloud cover. Nat. Commun. 12, 4337 (2021).

Xu, R. et al. Contrasting impacts of forests on cloud cover based on satellite observations. Nat. Commun. 13, 670 (2022).

Hua, W., Chen, H. & Li, X. Effects of future land use change on the regional climate in China. Sci. China Earth Sci 58, 1840–1848 (2015).

Niu, X., Tang, J., Wang, S. & Fu, C. Impact of future land use and land cover change on temperature projections over East Asia. Clim. Dyn. 52, 6475–6490 (2019).

Gálos, B. et al. Case study for the assessment of the biogeophysical effects of a potential afforestation in Europe. Carbon Bal. Manage 8, 3 (2013).

Hua, W., Zhou, L., Dai, A., Chen, H. & Liu, Y. Important non-local effects of deforestation on cloud cover changes in CMIP6 models. Environ. Res. Lett. 18, 094047 (2023).

Devaraju, N., Bala, G. & Modak, A. Effects of large-scale deforestation on precipitation in the monsoon regions: Remote versus local effects. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 112, 3257–3262 (2015).

Winckler, J., Reick, C. H. & Pongratz, J. Why does the locally induced temperature response to land cover change differ across scenarios? Geophys. Res. Lett. 44, 3833–3840 (2017).

Winckler, J., Reick, C. H. & Pongratz, J. Robust Identification of Local Biogeophysical Effects of Land-Cover Change in a Global Climate Model. J. Climate 30, 1159–1176 (2017).

Butt, E. W. et al. Amazon deforestation causes strong regional warming. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 120, e2309123120 (2023).

Brovkin, V. et al. Effect of anthropogenic land-use and land-cover changes on climate and land carbon storage in CMIP5 projections for the twenty-first century. J. Climate 26, 6859–6881 (2013).

Zhang, M. et al. Impacts of anthropogenic land use and land cover change on climate extremes based on CMIP6-LUMIP experiments: part II. Future period. Clim. Dyn. 62, 3669–3688 (2024).

Li, Y., Gao, Y., Chen, G., Wang, G. & Zhang, M. Decomposition and reduction of WRF-modeled wintertime cold biases over the Tibetan Plateau. Clim. Dyn. 62, 4189–4203 (2024).

Wang, L., Liu, Z., Lang, X. & Jiang, D. Understanding Surface Air Temperature Cold Bias Over China in CMIP6 Models. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 128, e2023JD039515 (2023).

Zhou, X. et al. Reducing the Cold Bias of the WRF Model Over the Tibetan Plateau by Implementing a Snow Coverage-Topography Relationship and a Fresh Snow Albedo Scheme. J. Adv. Model. Earth. Sy. 15, e2023MS003626 (2023).

Kang, S. et al. Linking atmospheric pollution to cryospheric change in the Third Pole region: current progress and future prospects. Nat. Sci. Rev. 6, 796–809 (2019).

Yang, H., Jiang, Z. & Li, L. Biases and improvements in three dynamical downscaling climate simulations over China. Clim. Dyn. 47, 3235–3251 (2016).

Prein, A. F. et al. A review on regional convection-permitting climate modeling: Demonstrations, prospects, and challenges. Rev. Geophys. 53, 323–361 (2015).

Fosser, G. et al. Convection-permitting climate models offer more certain extreme rainfall projections. npj. Clim. Atmos. Sci. 7, 1–10 (2024).

Kendon, E. J. et al. Enhanced future changes in wet and dry extremes over Africa at convection-permitting scale. Nat. Commun. 10, 1794 (2019).

Bastin, J.-F. et al. The global tree restoration potential. Science 365, 76–79 (2019).

Veldman, J. W. et al. Comment on “The global tree restoration potential”. Science 366, eaay7976 (2019).

Lewis, S. L., Mitchard, E. T. A., Prentice, C., Maslin, M. & Poulter, B. Comment on “The global tree restoration potential”. Science 365, 76–79 (2019).

Ge, J. et al. Local surface cooling from afforestation amplified by lower aerosol pollution. Nat. Geosci. 16, 781–788 (2023).

Belušić, D., Fuentes-Franco, R., Strandberg, G. & Jukimenko, A. Afforestation reduces cyclone intensity and precipitation extremes over Europe. Environ. Res. Lett. 14, 074009 (2019).

Zhao, B. et al. A combined Terra and Aqua MODIS land surface temperature and meteorological station data product for China from 2003 to 2017. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 12, 2555–2577 (2020).

Ma, M., Hui, P., Liu, D., Zhou, P. & Tang, J. Convection-permitting regional climate simulations over Tibetan Plateau: re-initialization versus spectral nudging. Clim. Dyn. 58, 1719–1735 (2022).

Tian, L., Zhang, B., Wang, X., Chen, S. & Pan, B. Large-Scale Afforestation Over the Loess Plateau in China Contributes to the Local Warming Trend. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 127, e2021JD035730 (2022).

He, Y., Lee, E. & Warner, T. A. A time series of annual land use and land cover maps of China from 1982 to 2013 generated using AVHRR GIMMS NDVI3g data. Remote Sens. Environ. 199, 201–217 (2017).

Li, X., Messina, J. P., Moore, N. J., Fan, P. & Shortridge, A. M. MODIS land cover uncertainty in regional climate simulations. Clim. Dyn. 49, 4047–4059 (2017).

Friedl, M. A. et al. Global land cover mapping from MODIS: algorithms and early results. Remote Sens. Environ. 83, 287–302 (2002).

Friedl, M. A. et al. MODIS Collection 5 global land cover: Algorithm refinements and characterization of new datasets. Remote Sens. Environ. 114, 168–182 (2010).

Loveland, T. R. et al. Development of a global land cover characteristics database and IGBP DISCover from 1 km AVHRR data. Int. J. Remote. Sens. 21, 1303–1330 (2000).

Sulla-Menashe, D., Gray, J. M., Abercrombie, S. P. & Friedl, M. A. Hierarchical mapping of annual global land cover 2001 to present: The MODIS Collection 6 Land Cover product. Remote Sens. Environ. 222, 183–194 (2019).

Zhao, Y. et al. WRF/UCM simulations of the impacts of urban expansion and future climate change on atmospheric thermal environment in a Chinese megacity. Clim. Change 169, 38 (2021).

Ge, J., Pitman, A. J., Guo, W., Zan, B. & Fu, C. Impact of revegetation of the Loess Plateau of China on the regional growing season water balance. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 24, 515–533 (2020).

Gao, H. & Jia, G. Assessing disagreement and tolerance of misclassification of satellite-derived land cover products used in WRF model applications. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 30, 125–141 (2013).

Yu, L. et al. Influence of snow cover changes on surface radiation and heat balance based on the WRF model. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 130, 205–215 (2017).

Hersbach, H. et al. The ERA5 global reanalysis. Q. J. Roy. Meteor. Soc. 146, 1999–2049 (2020).

Müller, W. A. et al. A Higher-resolution Version of the Max Planck Institute Earth System Model (MPI-ESM1.2-HR). J. Adv. Model. Earth. Sy. 10, 1383–1413 (2018).

Song, S., Zhang, X., Gao, Z. & Yan, X. Evaluation of atmospheric circulations for dynamic downscaling in CMIP6 models over East Asia. Clim. Dyn. 60, 2437–2458 (2023)

Karim, R., Tan, G., Ayugi, B., Babaousmail, H. & Liu, F. Evaluation of Historical CMIP6 Model Simulations of Seasonal Mean Temperature over Pakistan during 1970–2014. Atmosphere 11, 1005 (2020).

Kamruzzaman, M. et al. Assessment of CMIP6 global climate models in reconstructing rainfall climatology of Bangladesh. Int. J. Climatol. 42, 3928–3953 (2022).

Han, Y., Zhang, M.-Z., Xu, Z. & Guo, W. Assessing the performance of 33 CMIP6 models in simulating the large-scale environmental fields of tropical cyclones. Clim. Dyn. 58, 1683–1698 (2022).

Zhang, H. et al. Improved simulation of compound drought and heat extremes in Eastern China through CWRF downscaling. Environ. Res. Lett. 19, 124037 (2024).

Zhang, M. Z., Han, Y., Xu, Z. & Guo, W. Assessing climate extremes in dynamical downscaling simulations driven by a novel bias-corrected CMIP6 data. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 129, e2024JD041253 (2024).

Xu, Z., Han, Y., Tam, C.-Y., Yang, Z.-L. & Fu, C. Bias-corrected CMIP6 global dataset for dynamical downscaling of the historical and future climate (1979–2100). Sci. Data 8, 293 (2021).

Liu, S., Zeman, C. & Schär, C. Dynamical Downscaling of Climate Simulations in the Tropics. Geophys. Res. Lett. 51, e2023GL105733 (2024).

Zuo, Z. et al. Projection of Future Heatwaves in the Pearl River Delta through CMIP6-WRF Dynamical Downscaling. J. Appl. Meteorol. Clim. 62, 1297–1314 (2023).

Xu, Z. et al. Assessing the Performance of a Dynamical Downscaling Simulation Driven by a Bias-Corrected CMIP6 Dataset for Asian Climate. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 41, 974–988 (2024).

O’Neill, B. C. et al. The Scenario Model Intercomparison Project (ScenarioMIP) for CMIP6. Geosci. Model Dev. 9, 3461–3482 (2016).

Fricko, O. et al. The marker quantification of the Shared Socioeconomic Pathway 2: A middle-of-the-road scenario for the 21st century. Global Environ. Change 42, 251–267 (2017).

Skamarock, W. C. et al. A description of the advanced research WRF model version 4, 145. Boulder, CO, USA: National Center for Atmospheric Research; 2019.

Cardoso, R. M., Soares, P. M. M., Lima, D. C. A. & Miranda, P. M. A. Mean and extreme temperatures in a warming climate: EURO CORDEX and WRF regional climate high-resolution projections for Portugal. Clim. Dyn. 52, 129–157 (2019).

Soares, P. M. M. et al. WRF high resolution dynamical downscaling of ERA-Interim for Portugal. Clim. Dyn. 39, 2497–2522 (2012).

Gao, Z., Yan, X., Dong, S., Luo, N. & Song, S. Object-based evaluation of rainfall forecasts over eastern China by eight cumulus parameterization schemes in the WRF model. Atmos. Res. 284, 106618 (2023).

Cowherd, M. et al. Climate change-resilient snowpack estimation in the Western United States. Commun. Earth Environ. 5, 1–10 (2024).

Zhang, X., Ding, N., Han, S. & Tang, Q. Irrigation‐induced potential evapotranspiration decrease in the Heihe River Basin, Northwest China, as simulated by the WRF model. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 125, e2019JD031058 (2020).

Song, S., Zhang, X. & Liu, J. Effects of irrigation-induced surface thermodynamics changes on wind speed in the Heihe River basin, Northwest China. Int. J. Climatol. 44, 3445–3463 (2024).

Hong, S.-Y., Dudhia, J. & Chen, S.-H. A Revised Approach to Ice Microphysical Processes for the Bulk Parameterization of Clouds and Precipitation. Mon. Weather Rev. 132, 103–120 (2004).

Collins, W. D. et al. Description of the NCAR community atmosphere model (CAM 3.0). NCAR Tech. Note NCAR/TN-464+ STR 226, 1326–1334 (2004).

Grell, G. A. & Dévényi, D. A generalized approach to parameterizing convection combining ensemble and data assimilation techniques. Geophys. Res. Lett. 29, 38-1–38–4 (2002).

Niu, G.-Y. et al. The community Noah land surface model with multiparameterization options (Noah-MP): 1. Model description and evaluation with local-scale measurements. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 116, D12110 (2011).

Noh, Y., Cheon, W. G., Hong, S. Y. & Raasch, S. Improvement of the K-profile Model for the Planetary Boundary Layer based on Large Eddy Simulation Data. Bound Lay. Meteorol. 107, 401–427 (2003).

Hu, Y. et al. Modeled responses of summer climate to realistic land use/cover changes from the 1980s to the 2000s over eastern China. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 120, 167–179 (2015).

Hirsch, A. L. et al. Biogeophysical Impacts of Land-Use Change on Climate Extremes in Low-Emission Scenarios: Results From HAPPI-Land. Earths Future 6, 396–409 (2018).

Mooney, P. A., Lee, H. & Sobolowski, S. Impact of Quasi-Idealized Future Land Cover Scenarios at High Latitudes in Complex Terrain. Earths Future 9, e2020EF001838 (2021).

Gao, Z. et al. Effects of cumulus and radiation parameterization on summer surface air temperature over eastern China. Clim. Dyn. 61, 559–577 (2023).

Li, X. et al. Inconsistent Responses of Hot Extremes to Historical Land Use and Cover Change Among the Selected CMIP5 Models. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 123, 3497–3512 (2018).

Li, X. et al. Modeling the effects of realistic land cover changes on land surface temperatures over China. Clim. Dyn. 61, 1451–1474 (2022).

Huang, H. et al. Assessing Global and Regional Effects of Reconstructed Land-Use and Land-Cover Change on Climate since 1950 Using a Coupled Land–Atmosphere–Ocean Model. J. Climate 33, 8997–9013 (2020).

Thiery, W. et al. Present-day irrigation mitigates heat extremes. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 122, 1403–1422 (2017).

Acknowledgements

We gratefully thank the support of the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2019YFA0606600).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.Z. and X.Y. designed the research; S.S. and X.Z. ran the simulations. S.S. and X.Y. carried out analysis of the modelling results. Z.G. discussed the results throughout the whole process. W.X. revised and modified the draft. All authors contributed to writing the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

41612_2025_915_MOESM1_ESM.pdf

Supplementary information for Weakened Future Surface Warming in China due to National Planned Afforestation through Biophysical Feedback

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Song, S., Yan, X., Zhang, X. et al. Weakened future surface warming in China due to national planned afforestation through biophysical feedback. npj Clim Atmos Sci 8, 42 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-00915-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-00915-2