Abstract

The amplified warming on the Tibetan Plateau (TA) is a distinctive characteristic of global climate change, leading to various climate responses with far-reaching implications. This study investigates the influence of interannual variation of TA on summer precipitation over East Asia (Pre_EA) using observational data and a Linear Baroclinic Model (LBM). When TA exceeds the Northern Hemisphere average, summer precipitation in the Yangtze River Valley significantly decreases, while it increases in North China and South China, resulting in a tripole Pre_EA pattern. Notably, the relationship between TA and Pre_EA is independent of the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) and explains more variance in Pre_EA than ENSO. Our analysis reveals that TA enhances the tripole Pre_EA pattern by modulating moisture transport and vertical motion in the East Asia-North Pacific regions. Specifically, positive TA is linked to significant local tropospheric warming, which intensifies and eastward expands the South Asian High, creating a double-gyre meridional circulation over East Asia. Additionally, positive TA induces an eastward-propagating wave, reinforcing a midlatitude anomalous high-pressure belt over East Asia and the western North Pacific regions. These circulation changes weaken the East Asian subtropical jet, form a notable double jet configuration, and promote subsidence over mid-latitude East Asia. Moreover, anomalously warm sea surface temperatures in the Northwestern Pacific reinforce the TA-Pre_EA relationship by contributing to the mid-latitude East Asia-North Pacific high-pressure belt. Our LBM model experiments support these findings. Our study provides an in-depth understanding of the physical processes influencing summer precipitation variability in East Asia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

East Asia, one of the most densely populated and economically significant regions globally, experiences substantial impacts from summer rainfall variations on its ecological environment and people’s livelihoods, drawing extensive research attention1,2,3,4,5,6,7. Under global warming, both mean and extreme precipitation have notably increased in East Asia over the past few decades8,9,10,11. Various factors contribute to the variability of precipitation over East Asia, such as the East Asian summer monsoon (EASM)1,7,12 and the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO)13,14,15. Other influencing factors include the tropical Indo-Pacific sea surface temperature anomalies (SSTAs)16,17,18,19, the western Pacific subtropical high (WPSH)20,21,22,23, and the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO)24,25,26. Previous work revealed that positive winter SSTAs in the central-eastern tropical Pacific and tropical Indian Ocean can lead to the formation of a lower-level anomalous anticyclone over the western North Pacific, which can persist into summer, enhancing northward water vapor transport along its western flank to the continent’s interior and surrounding areas14,19.

Recognized as the world’s highest and most expansive plateau, the Tibetan Plateau has an average elevation exceeding 4000 m27,28,29. This high elevation positions the Tibetan Plateau as the largest cryosphere (including snow and glaciers) outside the polar regions30,31,32,33,34,35. The Tibetan Plateau is the source of many major Asian rivers, such as the Yellow River, the Yangtze River, the Ganges River, and numerous inland rivers, providing water resources to over 1.4 billion people and earning the title “Asian Water Tower”36,37,38,39,40. The thermal effects of the Tibetan Plateau also significantly influence the Asian summer precipitation41,42,43,44,45,46. Wang et al.47 identified that Tibetan Plateau warming enhances frontal precipitation in East Asia via Rossby wave trains. Some studies demonstrate that variations in Tibetan Plateau winter-spring snow cover and spring sensible heat weaken the EASM, altering rainfall distribution over the Yangtze River Valley and prompting shifts in the monsoon rainfall belt48,49.

Similar to the Arctic amplification (AA), a phenomenon that describes the Arctic region experiencing an accelerated warming trend compared to the rest of the globe50,51, the Tibetan Plateau’s surface experienced rapid warming, with a trend that is nearly twice the global average52,53,54,55. This feature is documented as Tibetan Plateau amplified warming (TA) by previous researches29,56,57,58. The TA effect leads to significant climatic changes over the Tibetan Plateau and surrounding regions, including glacier retreat, decreased biodiversity, reduced snow cover, permafrost degradation, and more frequent climate extremes29,35,39,40,59,60,61. It also influences the intensity and location of the South Asian High2,45,62,63. However, the relationship between TA and summer precipitation over East Asia (Pre_EA) and the mechanisms is not clear. This research discovers that variation of TA is closely related to a tripole pattern of summer Pre_EA, accounting for more considerable variance in summer Pre_EA than ENSO. We investigated the physical processes behind the TA-Pre_EA relationship using both observational data and numerical model experiments. These findings provide a new perspective in understanding the complex physical mechanisms of East Asia summer precipitation variations.

Results

The relationship between the TA and summer Pre_EA

Both global and Tibetan Plateau temperatures exhibited significant warming from 1940 to 2022, with annual mean temperature warming rates accelerating markedly post-mid-1970s (Fig. 1a), aligning with previous studies29,58. After the mid-1970s, the Tibetan Plateau experienced enhanced warming (0.35 K per decade, p < 0.01) compared to the global average (0.2 K per decade, p < 0.01), resembling Arctic amplification (AA)64,65,66,67. This Tibetan Plateau amplified warming phenomenon is also evident in the annual mean (Supplementary Fig. 1a) and summer (Supplementary Fig. 1b) 30-year sliding warming trends. Prior research predominantly focused on the amplified warming of the Tibetan Plateau in wintertime68. However, Fig. 1b indicates that the Tibetan Plateau summer warming rate (0.34 K per decade, p < 0.01) also significantly exceeded the global average (0.18 K per decade, p < 0.01). In this work, we concentrate on summer TA and its impact on summer precipitation over East Asia after mid-1970s.

Normalized time series of global-averaged (shading) and Tibetan Plateau-averaged (blue line) (a) annual mean and (b) summer 2 m temperature during 1940–2022. k1 and k2 are the linear trends, ** indicates that the linear trend exceeds the 99% confidence level. Regression of summer 2 m temperature (unit: °C) onto the (c) original and (d) detrended TA index during 1976–2022. The cross lines indicate where the anomalies are significant at the 95% confidence level. The (e) normalized and (f) detrended time series of summer TA during 1976–2022. The dashed gray line in (e) denotes the linear trend.

We constructed the summer TA index as the area-averaged summer surface temperature difference between the Tibetan Plateau and the Northern Hemisphere for 1976–2022. The TA index (Fig. 1e, f) shows that the time series shows both interannual component and long-term trends (0.18 K per decade, p < 0.1), indicating that the amplified TP warming can impact the climate on multiple time scales. TA-associated temperatures indicate extensive warming across the extratropical Northern Hemisphere (Fig. 1c), with the most pronounced warming over three regions, i.e., the Tibetan Plateau-East Asia-North Pacific, eastern Europe and the North America-western Atlantic regions, implying a hemispheric-wide TA related anomalous temperature. To isolate the global warming effect, the summer TA index was detrended (Fig. 1f) and the associated temperature patterns are displayed in Fig. 1d. The most pronounced warming related to detrended TA index appears over the Tibetan Plateau-central North Pacific regions (Fig. 1d). The similarities between Fig. 1c, d suggest that the TA has similar climate impact on the long-term and interannual component. The difference between these two temperature patterns also indicates that the TA’s impact on the climate over the East Asian region is most pronounced for the interannual TA variation. Inspired by the above results, our current study aims to elucidate the distinct influence of TA on East Asian summer precipitation on interannual timescales.

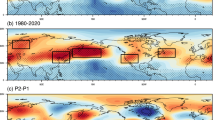

We then examined the potential relationship between the TA and summer precipitation over East Asia. Our results reveal a significant correlation between TA variations and a tripole pattern of precipitation anomalies in East Asia (Pre_EA) on both interannual (Fig. 2a) and interdecadal (Fig. 2b) time scales. Specifically, when warming over the Tibetan Plateau surpasses the average warming of the Northern Hemisphere, significantly decreased rainfall is observed in the Yangtze River Valley and increased rainfall in both North China and South China. By comparing Fig. 2a, b, it can be found that the summer East Asian precipitation anomalies related to the interdecadal component of TA also presents as a tripole pattern, but the magnitudes and significance of the anomalies are far less than those associated with interannual TA (Fig. 2a), suggesting that the interannual variability in TA has a distinct and significant impact on the summer precipitation over East Asia. Previous work focus on examining the long-term characteristics or impact of the amplified TP warming. Here this study focused on the interannual variability of TA. We revealed that the interannual component of the TA is an important indicator for the summer climate variation over East Asia. While long-term trends provide valuable insights into climate change, interannual variability offers a more nuanced understanding of annual climate dynamics, particularly for extreme weather events and seasonal precipitation patterns that have significant societal and environmental implications. Consequently, subsequent analyses focused on the TA-Pre_EA relationship on the interannual time scale.

Regression of summer precipitation (unit: mm/day) onto the (a) interannual and (b) interdecadal component of TA index during 1976–2022. c Composite differences in the summer precipitation (unit: mm/day) between the high and low TA years for the period 1976–2022. The years that were chosen for the composite are denoted in Table 1. d Spatial pattern of EOF1 of the summer precipitation (mm/day) over eastern China during 1976–2022. The numbers in the top right brackets indicate the percentage of the variance explained by EOF1. The red square denotes the area to do the EOF analysis (20°–40°N, 105°–123°E). e The corresponding normalized principle component of EOF1 (PC1; transparent bar) and the interannual component of PC1 (PC1_IA; red and blue bar) and TA index (TA_IA; purple line). ** indicates that the correlation coefficients exceed the 99% confidence level. The spatial pattern of EOF1 is represented by the linear regression of the summer precipitation onto PC1. The cross lines indicate where the anomalies are significant at the 95% confidence level.

In this study, we use the TA index to emphasize the amplified warming of the Tibetan Plateau relative to the Northern Hemisphere. A Tibetan Plateau Temperature Index (TPTI) is constructed by area-averaging the temperature over the Tibetan Plateau. To clarify the differences between the TA and TPTI, we also examined the regressions of summer precipitation against the interannual component of the TPTI index (TPTI_IA) (not shown). Both figures exhibit a tripolar anomaly pattern over East Asia; however, the TPTI_IA-related precipitation shows reduced magnitudes and significance, particularly in southern China and surrounding areas. This indicates that both indices capture the relationship between variations in Tibetan Plateau temperature and East Asian summer precipitation. However, the correlation between TA_IA and summer precipitation is more robust than that of TPTI_IA. Therefore, the TA index serves as a more representative measure of the amplified warming phenomena associated with the Tibetan Plateau. Consequently, our study employs the TA index for further investigations.

We also performed composite analyses of summer rainfall based on the detrended TA index to further validate the TA-Pre_EA relationship. Years with interannual TA index of 0.8 standard deviations were identified as strong anomalous TA years. Ten positive high and ten negative anomalous TA years were selected, with the remainder classified as normal years (Table 1). The composite of summer precipitation (Fig. 2c) illustrates a significant precipitation tripole pattern, closely resembling Fig. 2a. This composite analysis reinforces the statistical robustness of the TA-Pre_EA linkage, indicating consistent observational results regardless of the analytical method used. To understand the importance of the tripole pattern of the Pre_EA, we further conducted an Empirical Orthogonal Function (EOF) analysis of summer Pre_EA from 1976 to 2022. The dominate feature of the leading mode (EOF1) exhibits an out-of-phase variation between precipitation over the Yangtze River Valley and South China. Weak positive precipitation anomalies can also be noticed in North China. The corresponding principal component (PC1) of EOF1 highly correlated with the interannual components of the TA index (r = 0.45, p < 0.01) (Fig. 2e). In sum, the analysis reveals the importance of the Pre_EA tripole pattern and confirms the substantial correlation between the interannual variations in TA and summer Pre_EA.

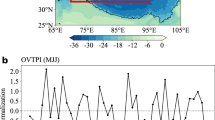

As mentioned before, ENSO significantly affects precipitation in South China13,14,43 and also impacts warming on the Tibetan Plateau69,70. Therefore, it is crucial to examine the role of ENSO in the above TA-Pre_EA relationship. We investigated the tropical sea surface temperature anomalies (SSTAs) associated with TA variations during the preceding spring and winter. Results indicated weak and non-significant SSTAs in winter (Supplementary Fig. 2a). In contrast, spring SSTAs exhibited a distinct “Cold East-Warm West” pattern over the tropical Pacific (Fig. 3e), akin to a La Niña pattern. The correlation coefficient between summer TA and spring Niño3.4 indices was –0.33 (p < 0.05) (Supplementary Fig. 2b), indicating an existing TA-ENSO relationship. The spring Niño3.4 index was associated with a tripole precipitation pattern in East Asia (Fig. 3a). However, the most significant values related to Niño3.4 are the positive precipitation anomalies in the South China Sea. In contrast, the decreased precipitation anomalies over the Yangtze River Valley are much weaker than Fig. 2a, c. The differences suggest that the TA and ENSO impacted regions of the precipitation over East Asia are not totally overlapped.

a Regression of summer precipitation (unit: mm/day) onto the interannual component of spring Niño3.4 index during 1976–2022. b Composite differences in summer precipitation (unit: mm/day) between the high and low TA years for the period 1976–2022 without strong ENSO years. The strong ENSO years are marked with bold fonts in Table 1. The percentage of summer precipitation variance explained by interannual (c) spring Niño34 and (d) summer TA index. e Correlation coefficients between spring sea surface temperature (SST) and summer TA from 1976 to 2022. The black (gray) cross lines indicate where the correlation coefficients or the anomalies are significant at the 95% (90%) confidence level.

We conducted a conditional composite analysis to exclude ENSO’s influence on the TA-Pre_EA. El Niño (La Niña) events were selected if the spring Niño3.4 index was greater (less) than 0.8 (–0.8) of a standard deviation, marked by bold fonts in Table 1. The summer precipitation composites, excluding El Niño and La Niña years, showed significant precipitation anomalies in the Yangtze River Valley and North China. At the same time, South China experienced a weakened excessive precipitation anomaly (Fig. 3b). This confirms that the TA-Pre_EA tripole pattern relationship is generally independent of ENSO, except in South China, where ENSO also plays a significant role. A comparison between Fig. 3c, d further indicates that the dominant regions of summer precipitation associated with ENSO and TA are distinct across East Asia. ENSO primarily affects summer precipitation in the South China Sea, whereas TA accounts for a more significant variance in precipitation in the Yangtze River Valley and North China (Fig. 3d).

The possible physical mechanism

We then examined the TA-related atmospheric circulation anomalies to understand the underlying physical mechanisms responsible for the TA-Pre_EA relationship. When TA intensifies, the heating effect of the Tibetan Plateau on the atmosphere also becomes more pronounced. This enhancement leads to increased vertical motion over the Plateau, resulting in greater atmospheric instability and the establishment of a prominent anticyclonic system over East Asia (Fig. 4b). Along the southern edge of this high-pressure system, moisture is transported from the western Pacific to the Yangtze River Valley (Fig. 4a). This moisture is subsequently carried northward to North China (Fig. 4a), resulting in moisture divergence in the Yangtze River Valley and convergence in North China, which in turn leads to increased precipitation in the former and decreased precipitation in the latter. Concurrently, cyclonic anomalies dominate South China, where moisture is transported northward from the low-latitude Pacific, causing moisture convergence in that region (Fig. 4a) and corresponding increases in precipitation. These circulation anomalies and moisture transport patterns align with the tripole pattern observed in Pre_EA.

Summer (a) moisture flux (vector; unit: 102⋅kg⋅m−1⋅s−1), moisture divergence (shading; unit: kg⋅m−2⋅s−1) and (b) 850-hPa geopotential height (shading; unit: gpm) anomalies regressed by the TA_IA during 1976–2022. Longitude-altitude cross section along 26°–36°N for the regression of summer (c) temperature (unit: °C), (d) relative vorticity (unit: s−1) and (e) geopotential height (shading; unit: gpm) and vertical circulation (vector; unit: m⋅s−1) onto the TA_IA during 1976–2022. f Latitude-altitude cross section along 105°–125°E for the regression of summer geopotential height (shading; unit: gpm) and vertical circulation (vector; unit: m⋅s−1) onto the TA_IA during 1976–2022. The cross lines indicate where the anomalies are significant at the 95% confidence level.

Figure 4c–e provides the longitude–altitude cross-section (26°–36°N) for TA-related climate anomalies. The intensified TA is accompanied by significant local warming extending from the Tibetan Plateau surface to the upper troposphere, further extending eastward and downward to coastal East Asia (Fig. 4c). Unlike the Tibetan Plateau, the most significant warming over coastal East Asia appears in the lower troposphere. The TA-related warming is accompanied by anomalous high-pressure (Fig. 4e) and negative vorticity anomalies (Fig. 4d) in the lower to mid-troposphere over East Asia. These circulation anomalies are accompanied by significant subsidence in the Yangtze River Valley, accounting for reduced precipitation over there. In addition, the significant negative vorticity anomalies may facilitate the strengthening and eastward extension of the South Asian High into the lower levels of East Asia (Fig. 4e)2. In the latitude–altitude direction (105°–125°E), the anomalous circulation forms a double-gyre meridional circulation dominating East Asia, favorable for the tripole Pre_EA pattern. More specific, associated with strong TA, significant anomalous high-pressure dominates 25–50°N East Asia. Pronounced subsidence prevails between 25 and 35°N (Fig. 4f), corresponding to decreased precipitation in the Yangtze River Valley (Fig. 2a). On the southern side of the high-pressure system, strong ascent motion occurs between 15–20°N, corresponding to increased precipitation in South China (Fig. 4f). Another branch of ascent motion is noticed to the north of the high pressure, corresponding to increased precipitation over North China.

Earlier studies have suggested that the double jets, which are characterized by a zonally oriented band of weakened anomalous westerly winds with two belts of stronger westerly winds over southern and northern latitudes, can enhance the waveguide and amplify and maintain planetary waves within the mid-latitudinal belt. Consequently, this phenomenon may contribute to the prolonged persistence of anomalous high pressure as well as extreme events71,72. In the upper levels, the enhanced TA-associated high-pressure belt extends from the Tibetan Plateau to the central North Pacific (Fig. 5a). Under the control of this high-pressure belt, over the continent, easterly winds prevail on the southern side of the Tibetan Plateau between 20° and 30°N. In contrast, westerly wind anomalies dominate on the northern side between 40°–50°N. Over the North Pacific, the high-pressure belt is prevalent between 40° and 60°N, with the maximum-value area located northeast of the Japan Sea. Significant easterly winds dominate along its southern flank between 30°–40°N. These anomalous winds may modulate the upper jet stream over these latitudes. Figure 5b depicts upper-level zonal wind anomalies associated with TA. A significant negative zonal wind band extends from the Tibetan Plateau to the Northwest Pacific, indicating a weakening of the East Asian Subtropical Jet (EASJ). To its south, one prominent band of positive anomalies represents the enhanced subtropical jet stream (centered around 20°N), while the high-latitude band represents the intensified Arctic front jet (centered around 55°N). This forms a notable double jet configuration over the East Asia-west Pacific regions, which not only constrains the meridional displacement of the TA_IA-associated zonal high-pressure system but also enhances its intensity, contributing to the zonal extension and intensification of the subtropical high-pressure anomalies. In addition, the weakening of the EASJ results in reduced upward motions beneath the jet stream (Fig. 5c), leading to negative vorticity anomalies (Fig. 5d) and abnormal convergence aloft (not shown). These circulation anomalies can trigger secondary circulations on both sides of the jet stream axis, ultimately enhancing the double-gyre meridional circulation dominating East Asia and impacting Pre_EA.

Summer (a) 200-hPa geopotential height (shading; unit: gpm) and wind (vector; unit: m⋅s−1), (b) 200-hPa zonal wind (unit: m⋅s−1), (c) 500-hPa vertical velocity (unit: Pa⋅s−1) and (d) 200-hPa relative vorticity (unit: s−1) anomalies regressed by the TA_IA during 1976–2022. The green contours in (a) show the climatological location of the SAH. The red contour in (b) denotes the climatological position of the jet core with a zonal wind greater than 25 m⋅s−1. The cross lines indicate where the anomalies are significant at the 95% confidence level.

As illustrated in Fig. 4, the TA-related high-pressure belt extends significantly eastward into the central North Pacific, potentially intensified by local sea surface temperature anomalies (SSTAs). Figure 6a shows that substantial TA-related SSTAs dominate the East China Sea and the Northwest Pacific. To quantify this effect, we defined a North Pacific Sea Surface Temperature Index (NPSI) (Supplementary Fig. 3a) based on area-averaged SSTAs within the blue rectangle in Fig. 6a. The correlation coefficient between the interannual component of the NPSI and the TA is 0.58 (p < 0.01), indicating that the North Pacific SST anomalies have a close relationship with the TA variations. The NPSI-related apparent heat source (Q1; Supplementary Fig. 3c) analysis indicates that these warm Northwest Pacific SSTAs exert a warming influence on the overlying atmosphere through sea-to-air feedback process. Consequently, a prominent high-pressure anomaly develops in the upper troposphere, extending westward into East Asia and eastward to the central North Pacific (Fig. 6b). Additionally, the wind anomalies associated with this high-pressure belt similar to those observed in Fig. 4b. To assess the influence of the warm SSTAs in the Northwest Pacific on Pre_EA, we calculated the regression of Pre_EA against the NPSI index (Supplementary Fig. 4a). This analysis reveals a precipitation anomaly pattern characterized by a “Dry Yangtze River Valley and Wet North China and South China,” associated with the warm SSTAs in the Northwest Pacific. Considering the significant correlation between NPSI_IA and TA_IA, there may be a link between the interannual variability of TA and the positive SST anomalies over the North Pacific. On one hand, the anomalous warming over the Tibetan Plateau can alter the atmospheric circulation (Figs. 4 and 5), affecting the heat budget and moisture transport over the North Pacific. This might, in turn, modulate the SSTAs in the region. On the other hand, positive SSTAs in the North Pacific may exert a thermal forcing on the atmosphere (Supplementary Fig. 3c), influencing the atmospheric circulation patterns that may extend westward to affect the East Asia and the Tibetan Plateau (Fig. 6b). This two-way interaction suggests a coupled relationship between TA and NPSI_IA, where each can potentially force or be forced by the other. Therefore, we conducted a conditional composite analysis to examine the TA-Pre_EA relationship while excluding the impact of SSTAs. Years in which the NPSI_IA index exceeds 0.8 or falls below -0.8 (Table 1) were excluded from the composite analysis. This left us with six high and five low TA years (Table 1). The composite map of precipitation anomalies for these eleven remaining years still exhibits a significant tripole precipitation pattern (Supplementary Fig. 4b), indicating that the TA-Pre_EA relationship is impacted but mainly independent of the warm SSTAs in the Northwest Pacific.

a Correlation coefficients between summer SST and TA_IA from 1976 to 2022. The blue rectangle indicates the domains used to define the Northwest Pacific SST index (NPSI) (32°–50°N, 153°E–173°W). b Summer 200-hPa geopotential height (shading; unit: gpm) and wind (vector; unit: m⋅s−1) anomalies regressed by the interannual component of the Northwest Pacific SST index (NPSI_IA) during 1976–2022. The green contours in (b) show the climatological location of the SAH. c Spatial distribution and vertical profile of the warming forcing in the second LBM experiment (EXP2). (d) The average of 21–25 days’ model response of 200-hPa geopotential height (shading; unit: m) and wind (vector; unit: m⋅s−1) in EXP2.

LBM experiments

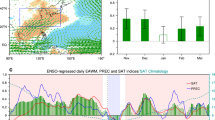

In this section, we employed the Linear Baroclinic Model (LBM) to conduct several numerical experiments to validate the physical processes by which TA influences atmospheric circulation. The averaged effects of TA on the above atmosphere are evident from the Q1 depicted in Fig. 7a, which shows significant positive Q1 values over the central-western Tibetan Plateau. This indicates that the intensification of TA is corresponding to a significant warming effect on the overlying atmosphere. Subsequently, in the numerical experiment (EXP2), we introduced a hypothetical thermal forcing located over Tibetan Plateau centered at 32°N, 90°E, with a long axis of 17° in longitude and a short axis of 9° in latitude to simulate TA-related heating (Fig. 7b). This thermal forcing peaks at a sigma level of 0.4, with a vertically averaged heating rate of 3°C/day (Fig. 7b) and maximum horizontal forcing values of 1°C/day. To ensure the stability of atmospheric responses, we analyzed the model atmospheric response from the 21 to the 25 day of the simulations (Fig. 7c, d).

a Summer Q1 (unit: W·m−2) anomalies regressed by the TA_IA during 1976–2022. The cross lines indicate where the anomalies are significant at the 95% confidence level. Spatial distribution and vertical profile of the warming forcing in the (b) first (EXP1) and (e) third LBM experiment (EXP3), respectively. The average of 21–25 days’ model response of 200-hPa geopotential height (shading; unit: m) and wind (vector; unit: m⋅s−1) in (c) EXP1 and (f) EXP3, respectively. d Longitude-altitude cross section along 26°–36°N of the average of 21–25 days’ model response of geopotential height (shading; unit: m) and temperature (contour; unit: °C) in EXP1.

The model’s atmospheric response to this thermal forcing reveals a strong high-pressure anomaly dominating over the Tibetan Plateau and East Asia (Fig. 7c), accompanied by prevalent easterly anomalies to the south and westerly anomalies to the north, similar to Fig. 5a. Additionally, weak negative and positive geopotential height anomalies are observed over east of Japan and the Northwest Pacific, respectively (Fig. 7c). The zonal cross-section of the model atmosphere (Fig. 7d) shows strong positive geopotential height anomalies dominating the mid-to-upper troposphere over the Tibetan Plateau. These hight anomalies extend eastward and downward, resulting in high pressure over the Yangtze River Valley, consistent with Fig. 4e. Further downstream, alternating negative and positive geopotential height anomalies form a propagating wave train. The barotropic structure observed in the reanalysis data (Fig. 4e) indicates a deeper and more uniform response across pressure levels, whereas the response in the LBM experiment reveals a more baroclinic pattern. This discrepancy is likely attributable to the idealized heating profile employed in the LBM. However, in the current study, we focus on replicating the upper-level atmospheric response to the thermal forcing associated with the TA_IA index, and the main characteristics have been reasonably captured by the LBM. EXP2 demonstrates that the atmospheric circulation response to TA heating replicates the amplification and eastward extension of the South Asian High, influencing prevailing wind patterns and pressure systems over East Asia.

To investigate the impact of Northwest Pacific warm SSTAs on atmosphere, we conducted another LBM experiment (EXP1). In EXP1, we set an idealized thermal forcing at 48°N, 165°E, characterized by a longitudinal axis of 15° and a latitudinal axis of 7°(Fig. 6c). The vertically averaged heating rate (3°C/day) and maximum horizontal values (1°C/day) of this thermal forcing are identical to those in EXP2. As in the previous experiment, we examined the atmospheric responses averaged from the 21 to the 25 day (Fig. 6d). The results confirm that warm SSTAs can induce a robust high-pressure anomaly in the upper troposphere, extending westward into Tibetan Plateau and eastward to central North Pacific. This process involves air-sea interactions. Specifically, the anomalous warming over the Tibetan Plateau induces high-pressure anomalies over East Asia and coastal regions (Figs. 4, 5). This anomalous high pressure is associated with descending motion (Fig. 5c), which promotes elevated SSTs in the western North Pacific. Conversely, positive SST anomalies in this region exert thermal forcing on the overlying atmosphere (LBM EXP1, Supplementary Fig. 3c), strengthening the thermal anomaly-related atmospheric circulation patterns and extending them further westward (Fig. 6b, d). Specially, warm SSTs in the North Pacific act as an atmospheric heat source, forming an anomalous anticyclone in the upper troposphere. Consequently, this high-pressure anomaly extends westward into the Tibetan Plateau and eastward toward the central North Pacific, as illustrated in Fig. 6b of our study.

We then designed a third numerical experiment to validate the atmospheric response to combined forcings from both TA and Northwest Pacific warm SSTAs (EXP3). In EXP3, the positions and shapes of the two thermal forcings are identical to those in EXP1 and EXP2 (Fig. 7e), with the same vertical settings. The mean circulation anomalies from the 21 to the 25 days reveal a large-scale high-pressure anomalies belt extending from the Tibetan Plateau to the North Pacific (Fig. 7f), similar to that depicted in Fig. 5a. This indicates that both TA and warm SSTAs in the Northwest Pacific contribute to the atmospheric circulation anomalies associated with abnormal summer Pre_EA. The positive geopotential heights near the Yangtze River Valley significantly modulate regional climate conditions, leading to altered precipitation patterns.

Discussion

As one of the most significant indicators of global climate change, the amplified warming on the Tibetan Plateau (TA) can trigger a series of climate responses with far-reaching global consequences. This research examines the relationship between interannual variations in TA and summer precipitation over East Asia (Pre_EA), utilizing observational data from 1976 to 2022 and a Linear Baroclinic Model (LBM). Our results revealed that when TA exceeds the average warming for the Northern Hemisphere, there is a notable reduction in precipitation in the Yangtze River Valley, accompanied by an increase in North China and South China. This relationship is mainly independent of ENSO influences and explains more variance in Pre_EA. In the lower troposphere, the TA is related to anomalously eastward winds transporting moisture from the North Pacific toward East China, which further transport northward, resulting in moisture divergence over the Yangtze River Valley and convergence in North China. Meanwhile, South China is affected by moisture transport from the lower-latitude Pacific which related to a cyclonic system. Further investigations reveal that TA-related local warming effect in the overlying atmosphere results in deep high-pressure anomalies. This leads to an enhanced and eastward extended South Asian High. Additionally, positive tropical anomalies (TA) also induce eastward-propagating waves, which strengthen a midlatitude anomalous high-pressure belt over East Asia and the western North Pacific. These changes in circulation reduce the intensification of the East Asian subtropical jet, forming a distinct double jet configuration and promoting subsidence over mid-latitude East Asia. Furthermore, anomalously warm sea surface temperatures in the North Pacific enhance the TA-Pre_EA relationship by reinforcing the high-pressure belt in midlatitude East Asia and the North Pacific. Our LBM model experiments corroborate these findings.

In conclusion, our study provides an in-depth understanding of the physical processes influencing summer precipitation variability in East Asia. The independent and combined effects of TA and Pacific SSTAs on Pre_EA highlight the necessity for a comprehensive understanding of regional and global climatic interactions. The correlation coefficient between PC_IA and TA_IA is 0.45 (Fig. 2e), suggesting that additional factors also influence the tripole pattern of East Asian precipitation. Previous research indicates that during the developing phase of ENSO, SST anomalies in the eastern-central tropical Pacific can cause a tripole pattern of summer precipitation anomalies over East Asia14,15. Furthermore, the East Asian summer monsoon (EASM) can notably affect summer precipitation in East Asia. A weakening monsoon is closely linked to decreased precipitation in North China and increased precipitation in the Yangtze River Valley and South China1,12. Other factors, such as the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO)25,26 and the Western Pacific Subtropical High (WPSH)21,22, also play a role in modulating precipitation patterns in East Asia. Future research should focus on quantifying the relative contributions of these factors under changing climatic conditions to enhance predictive capabilities regarding regional precipitation patterns in a warming world.

Methods

Data and analysis

The monthly mean meteorological variables employed in this work, including 2 m surface temperature (t2m), total precipitation, sea surface temperature (SST), specific humidity, surface pressure, meridional and zonal wind, vertically integrated moisture divergence, geopotential height, relative vorticity, vertical velocity, divergence, net sensible heat flux (SHF), net longwave radiation flux at surface/top and net shortwave radiation flux at surface/top, are all obtained from the ERA5 reanalysis dataset, which is available from the European Center for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts73. In the ERA5 reanalysis dataset, the initial horizontal resolution for the monthly atmospheric variables is 0.25° × 0.25°. For data associated with pressure levels, such as specific humidity, meridional and zonal wind, geopotential height, relative vorticity, vertical velocity, and divergence, we have gridded these variables to a spatial resolution of 1° × 1°. The Niño-3.4 index is obtained from the Earth System Research Laboratory of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

The period of analysis in this study is chosen from 1976 to 2022. To concentrate on interannual variability, we employed a Fourier harmonic highpass filter to extract variations on timescales of less than eight years from all the data. Subsequently, these high-frequency components were utilized for further examination, with the confidence levels for both correlation and linear regression analyses determined by the Student’s t-test. An empirical orthogonal function (EOF) analysis is performed on the precipitation data to identify the dominant mode of the summer Pre_EA variations. A conditional composite analysis is executed to obtain the independent impacts of the TA on the interannual variations in Pre_EA.

To explore the influence of anomalous conditions at the surface on the atmosphere above, we calculated the apparent heat source (Q1) in a total atmospheric column adhering to the methodology outlined by Zhao and Chen74. The formulation of Q1 is expressed as follows:

Where SH represents the sensible heat flux at the surface, RAD denotes the net radiation within an atmospheric column, and COND refers to the latent heat associated with condensation processes. When the value of Q1 is positive, it indicates that the atmosphere functions as a heat source. Conversely, a negative Q1 value signifies that the atmosphere acts as a sink for heat.

Definition of Tibetan plateau amplification index (TA)

Following the approach developed by Wang et al.75 for defining the Arctic amplification index, we define the Tibetan Plateau amplification index (TA) as the difference in area-averaged t2m between the Tibetan Plateau and the Northern Hemisphere72, which can characterize the warming amplification on the Tibetan Plateau more intuitively. The formula is shown as follows:

Where \({\rm{T}}2{\rm{m}}\) is 2m surface temperature, superscript \({\rm{TP}}\) represent the area-averaged meteorological element within the domain of the Tibetan Plateau, and superscript \({\rm{NH}}\) represent the area-averaged meteorological element over the northern hemisphere. When TA is greater than 0, it indicates that the warming on the Tibetan Plateau exceeds the average warming across the Northern Hemisphere, and vice versa.

Linear baroclinic model (LBM)

This research employs a linear baroclinic model (LBM) to analyze the atmospheric reactions to designated idealized thermal forcings. This model simplifies the dynamic processes by eliminating the nonlinearity, allowing for straightforward interpretation of the outcomes. The study utilizes version 2.3 of the LBM, which operates at a T42 horizontal resolution and includes 20 sigma levels for vertical division. For a comprehensive overview of the LBM’s functionalities, one can refer to the work by Watanabe and Kimoto76.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Code availability

The codes were written in NCAR Command Language (NCL) and are available upon request from the corresponding author.

References

Ding, Y., Wang, Z. & Sun, Y. Inter‐decadal variation of the summer precipitation in East China and its association with decreasing Asian summer monsoon.Part I: Observed evidences. Int. J. Climatol. 28, 1139–1161 (2008).

Ge, J., You, Q. & Zhang, Y. Effect of Tibetan Plateau heating on summer extreme precipitation in East Asia. Atmos. Res. 218, 364–371 (2019).

Huang, D. Q., Zhu, J., Zhang, Y. C. & Huang, A. N. Uncertainties on the simulated summer precipitation over Eastern China from the CMIP5 models. J. Geophys. Res.: Atmospheres 118, 9035–9047 (2013).

Tang, Y. et al. Drivers of summer extreme precipitation events over East China. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48, e2021GL093670 (2021).

Wang, L. et al. Observed variability of summer precipitation pattern and extreme events in East China associated with variations of the East Asian summer monsoon. Int. J. Climatol. 36, 2942–2957 (2016).

Zhang, Q., Zheng, Y., Singh, V. P., Luo, M. & Xie, Z. Summer extreme precipitation in East Asia: Mechanisms and impacts. J. Geophys. Res.: Atmos. 122, 2766–2778 (2017).

Zhu, Y., Wang, H., Zhou, W. & Ma, J. Recent changes in the summer precipitation pattern in East China and the background circulation. Clim. Dyn. 36, 1463–1473 (2011).

Li, Z. et al. Changes of daily climate extremes in southwestern China during 1961–2008. Glob. Planet. Change 80-81, 255–272 (2012).

Trenberth, K. E., Dai, A., Rasmussen, R. M. & Parsons, D. B. The Changing Character of Precipitation. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 84, 1205–1218 (2003).

Wang, X., Hou, X. & Wang, Y. Spatiotemporal variations and regional differences of extreme precipitation events in the Coastal area of China from 1961 to 2014. Atmos. Res. 197, 94–104 (2017).

You, Q. et al. Changes in daily climate extremes in China and their connection to the large scale atmospheric circulation during 1961–2003. Clim. Dyn. 36, 2399–2417 (2010).

Wang, B. et al. How to Measure the Strength of the East Asian Summer Monsoon. J. Clim. 21, 4449–4463 (2008).

Feng, J. & Li, J. Influence of El Niño Modoki on spring rainfall over south China. J. Geophys. Res. 116, D13102 (2011).

Wang, B., Wu, R. & Fu, X. Pacific–East Asian Teleconnection: How Does ENSO Affect East Asian Climate? J. Clim. 13, 1517–1536 (2000).

Wu, R., Hu, Z.-Z. & Kirtman, B. P. Evolution of ENSO-Related Rainfall Anomalies in East Asia. J. Clim. 16, 3742–3758 (2003).

Gu, W., Wang, L., Hu, Z.-Z., Hu, K. & Li, Y. Interannual Variations of the First Rainy Season Precipitation over South China. J. Clim. 31, 623–640 (2018).

Jia, X., Zhang, C., Wu, R. & Qian, Q. Changes in the Relationship between Spring Precipitation in Southern China and Tropical Pacific–South Indian Ocean SST. J. Clim. 34, 6267–6279 (2021a).

Wang, B., Wu, R. & Li, T. Atmosphere–Warm Ocean Interaction and Its Impacts on Asian–Australian Monsoon Variation. J. Clim. 16, 1195–1211 (2003).

Xie, S.-P. et al. Indian Ocean Capacitor Effect on Indo–Western Pacific Climate during the Summer following El Niño. J. Clim. 22, 730–747 (2009).

Matsumura, S., Sugimoto, S. & Sato, T. Recent Intensification of the Western Pacific Subtropical High Associated with the East Asian Summer Monsoon. J. Clim. 28, 2873–2883 (2015).

Park, J. Y., Jhun, J. G., Yim, S. Y., & Kim, W. M. Decadal changes in two types of the western North Pacific subtropical high in boreal summer associated with Asian summer monsoon/El Niño–Southern Oscillation connections. J. Geophys. Res.: Atmos. 115. (2010).

Ren, X., Yang, X.-Q. & Sun, X. Zonal oscillation of western Pacific subtropical high and subseasonal SST variations during Yangtze Persistent Heavy Rainfall Events. J. Clim. 26, 8929–8946 (2013).

Yang, H. & Sun, S. Longitudinal displacement of the subtropical high in the western Pacific in summer and its influence. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 20, 921–933 (2003).

Chen, X., Jia, X. & Wu, R. Impacts of autumn-winter Central Asian snow cover on the interannual variation in Northeast Asian winter precipitation. Atmos. Res. 286, 106669 (2023).

Gao, T., Wang, H. J. & Zhou, T. Changes of extreme precipitation and nonlinear influence of climate variables over monsoon region in China. Atmos. Res. 197, 379–389 (2017).

Zhang, Q., Xiao, M., Singh, V. P. & Chen, Y. D. Max-stable based evaluation of impacts of climate indices on extreme precipitation processes across the Poyang Lake basin, China. Glob. Planet. Change 122, 271–281 (2014).

Qiu, J. China: The third pole. Nature 454, 393–396 (2008).

Qiu, J. Trouble in Tibet. Nature 529, 142–145 (2016).

You, Q. et al. Warming amplification over the Arctic Pole and Third Pole: Trends, mechanisms and consequences. Earth-Science Rev. 217, 103625 (2021).

Kang, S. et al. Review of climate and cryospheric change in the Tibetan Plateau. Environ. Res. Lett. 5, 015101 (2010).

Xu, X., Lu, C., Shi, X. & Gao, S. World water tower: An atmospheric perspective. Geophys. Res. Lett. 35, L20815 (2008).

Yao, T. et al. From Tibetan Plateau to third pole and pan-third pole. Bull. Chin. Acad. Sci. 32, 924–931 (2017).

Yao, T. et al. Different glacier status with atmospheric circulations in Tibetan Plateau and surroundings. Nat. Clim. Change 2, 663–667 (2012).

Yao, T. et al. Third Pole Environment (TPE). Environ. Dev. 3, 52–64 (2012).

Yao, T. et al. Recent Third Pole’s Rapid Warming Accompanies Cryospheric Melt and Water Cycle Intensification and Interactions between Monsoon and Environment: Multidisciplinary Approach with Observations, Modeling, and Analysis. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 100, 423–444 (2019).

Duan, A. & Xiao, Z. Does the climate warming hiatus exist over the Tibetan Plateau? Sci. Rep. 5, 13711 (2015).

Immerzeel, W. W. & Bierkens, M. F. P. Asia’s water balance. Nat. Geosci. 5, 841–842 (2012).

Immerzeel, W. W., Van Beek, L. P. H. & Bierkens, M. F. P. Climate change will affect the Asian Water towers. Science 328, 1382–1385 (2010).

You, Q. et al. Elevation dependent warming over the Tibetan Plateau: Patterns, mechanisms and perspectives. Earth-Sci. Rev. 210, 103349 (2020).

You, Q. et al. Review of snow cover variation over the Tibetan Plateau and its influence on the broad climate system. Earth-Sci. Rev. 201, 103043 (2020).

Duan, A. M. & Wu, G. X. Role of the Tibetan Plateau thermal forcing in the summer climate patterns over subtropical Asia. Clim. Dyn. 24, 793–807 (2005).

Hu, J. & Duan, A. Relative contributions of the Tibetan Plateau thermal forcing and the Indian Ocean Sea surface temperature basin mode to the interannual variability of the East Asian summer monsoon. Clim. Dyn. 45, 2697–2711 (2015).

Jia, X., Zhang, C., Wu, R. & Qian, Q. Influence of Tibetan Plateau autumn snow cover on interannual variations in spring precipitation over southern China. Clim. Dyn. 56, 767–782 (2021b).

Wang, Z., Duan, A. & Wu, G. Time-lagged impact of spring sensible heat over the Tibetan Plateau on the summer rainfall anomaly in East China: case studies using the WRF model. Clim. Dyn. 42, 2885–2898 (2013).

Wu, G. et al. The influence of mechanical and thermal forcing by the Tibetan Plateau on Asian Climate. J. Hydrometeorol. 8, 770–789 (2007).

Zhao, P., Zhou, Z. & Liu, J. Variability of Tibetan Spring Snow and its associations with the hemispheric extratropical circulation and East Asian Summer Monsoon Rainfall: An observational investigation. J. Clim. 20, 3942–3955 (2007).

Wang, B., Bao, Q., Hoskins, B., Wu, G. & Liu, Y. Tibetan Plateau warming and precipitation changes in East Asia. Geophys. Res. Lett. 35, L14702 (2008).

Duan, A., Wang, M., Lei, Y. & Cui, Y. Trends in Summer Rainfall over China Associated with the Tibetan Plateau Sensible Heat Source during 1980–2008. J. Clim. 26, 261–275 (2013).

Zhao, P., Yang, S. & Yu, R. Long-Term Changes in Rainfall over Eastern China and Large-Scale Atmospheric Circulation Associated with Recent Global Warming. J. Clim. 23, 1544–1562 (2010).

Screen, J. A. & Simmonds The central role of diminishing sea ice in recent Arctic temperature amplification. Nature 464, 1334–1337 (2010).

Serreze, M. C. & Barry, R. G. Processes and impacts of Arctic amplification: A research synthesis. Glob. Planet. Change 77, 85–96 (2011). (2011).

Liu, X. & Chen, B. Climatic warming in the Tibetan Plateau during recent decades. Int. J. Climatol. 20, 1729–1742 (2000).

Yan, Y., You, Q., Wu, F., Pepin, N. & Kang, S. Surface mean temperature from the observational stations and multiple reanalyses over the Tibetan Plateau. Clim. Dyn. 55, 2405–2419 (2020).

You, Q., Fraedrich, K., Ren, G., Pepin, N. & Kang, S. Variability of temperature in the Tibetan Plateau based on homogenized surface stations and reanalysis data. Int. J. Climatol. 33, 1337–1347 (2013).

You, Q. et al. Revisiting the relationship between observed warming and surface pressure in the Tibetan Plateau. J. Clim. 30, 1721–1737 (2017).

Hu, S. et al. Mechanisms of Tibetan Plateau Warming Amplification in Recent Decades and Future Projections. J. Clim. 36, 5775–5792 (2023).

You, Q. et al. Tibetan Plateau amplification of climate extremes under global warming of 1.5 °C, 2 °C and 3 °C. Global Planet. Change 192, 103261 (2020).

Zhang, C., Qin, D.-H. & Zhai, P.-M. Amplification of warming on the Tibetan Plateau. Adv. Clim. Change Res. 14, 493–501 (2023).

Bibi, S. et al. Climatic and associated cryospheric, biospheric, and hydrological changes on the Tibetan Plateau: A review. Int. J. Climatol. 38, e1–e17 (2018).

Dimri, A. P., Kumar, D., Choudhary, A. & Maharana, P. Future changes over the Himalayas: Mean temperature. Glob. Planet. Change 162, 235–251 (2018).

Yang, M., Wang, X., Pang, G., Wan, G. & Liu, Z. The Tibetan Plateau cryosphere: Observations and model simulations for current status and recent changes. Earth-Sci. Rev. 190, 353–369 (2019).

Wei, W., Zhang, R., Wen, M., Kim, B.-J. & Nam, J.-C. Interannual Variation of the South Asian High and Its Relation with Indian and East Asian Summer Monsoon Rainfall. J. Clim. 28, 2623–2634 (2015).

Zhang, P., Liu, Y. & He, B. Impact of East Asian Summer Monsoon Heating on the Interannual Variation of the South Asian High. J. Clim. 29, 159–173 (2016).

Cohen, J. et al. Recent Arctic amplification and extreme mid-latitude weather. Nat. Geosci. 7, 627–637 (2014).

Cohen, J. et al. Divergent consensuses on Arctic amplification influence on midlatitude severe winter weather. Nat. Clim. Change 10, 20–29 (2020).

Coumou, D., Di Capua, G., Vavrus, S., Wang, L. & Wang, S. The influence of Arctic amplification on mid-latitude summer circulation. Nat. Commun. 9, 2959 (2018).

Francis, J. A. & Vavrus, S. J. Evidence linking Arctic amplification to extreme weather in mid-latitudes. Geophys. Res. Lett. 39, L06801 (2012).

Duan, J., Li, L., Chen, L., & Zhang, H. Time‐dependent warming amplification over the Tibetan Plateau during the past few decades. Atmospheric Science Letters, 21 (2020).

Wang, Y. & Xu, X. Impact of ENSO on the Thermal Condition over the Tibetan Plateau. J. Meteorol. Soc. Jpn. Ser. II 96, 269–281 (2018).

Yong, Z. et al. Variability in temperature extremes across the Tibetan Plateau and its non-uniform responses to different ENSO types. Climatic Change 176, 91 (2023).

Rousi, E., Kornhuber, K., Beobide-Arsuaga, G., Luo, F. & Coumou, D. Accelerated western European heatwave trends linked to more-persistent double jets over Eurasia. Nat. Commun. 13, 3851 (2022).

Dong, W., Jia, X., Li, X. & Wu, R. Synergistic effects of Arctic amplification and Tibetan Plateau amplification on the Yangtze River Basin heatwaves. NPJ Clim. Atmos. Sci. 7, 150 (2024).

Hersbach, H. et al. The ERA5 global reanalysis. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 146, 1999–2049 (2020).

Zhao, P. & Chen, L. Climatic features of atmospheric heat source/sink over the Qinghai-Xizang Plateau in 35 years and its relation to rainfall in China. Sci. China Ser. D: Earth Sci. 44, 858–864 (2001).

Wang, Y., Huang, F. & Fan, T. Spatio-temporal variations of Arctic amplification and their linkage with the Arctic oscillation. Acta Oceanologica Sin. 36, 42–51 (2017).

Watanabe, M. & Kimoto, M. Atmosphere‐ocean thermal coupling in the North Atlantic: A positive feedback. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 126, 3343–3369 (2000).

Acknowledgements

This research is funded by the Joint Funds of the Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. LZJMD24D050002).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.J. contributed to the concept and design of the research. X.C. conducted the analysis and prepared the draft. X.J. acquired the funding. All the authors contributed to the writting and revising of the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jia, X., Chen, X., Dong, W. et al. Impact of Tibetan plateau warming amplification on the interannual variations in East Asia Summer precipitation. npj Clim Atmos Sci 8, 29 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-00920-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-00920-5