Abstract

This study investigates typhoon-induced mesoscale cyclonic eddies (TIME) in the western North Pacific. A total of 69 potential TIME candidates (1995–2018) were identified using global mesoscale eddy trajectory atlas and JTWC typhoon data. Subsequently, systematic analysis procedures were applied to those candidates. Analysis revealed that three cyclonic ocean eddies (COEs) were likely triggered by typhoons Rosie (1997), Nida (2009), and Ma-on (2011). Numerical modeling with a regional ocean modeling system (ROMS) reconstructed the ocean environment during these events. Semi-idealized experiments confirmed that typical TIME events arise from the energy transfer between kinetic and potential energy, with vertical diffusion and horizontal advection contributing significantly to COE spin-up. Divergence and vertical advection terms suppress excessive COE growth. Given the increasing intensity and slower movement of typhoons due to global warming, more TIMEs are expected in the future. Stronger, longer-lasting TIMEs may have significant climate impacts and should be a focus of future research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Mesoscale oceanic eddies are well documented for their influence on air–sea interactions during tropical cyclone (TC) passage, either hindering or sustaining air–sea fluxes into the TC core (e.g.1,2,3,4,5,). Previous studies have also highlighted the potential impact of mesoscale eddies on regional ocean dynamics and short-term climate system6,7,8,9,10,11,12. However, in the field of TC–eddy interaction, most of the attention has been directed to the effect of preexisting eddies on the TC-induced upper thermal response and the resulting changes in TC intensity1,2,3,4,5,13,14. Specifically, very little is known about how TCs alter the dynamical structure of underlying eddies during their passages12,15.

A limited number of studies that have reported the perturbation of underlying eddies by TC passages have mainly relied on either remote sensing or sparse in-situ measurements7,16,17,18,19. For example, Lu et al. 15 used satellite sea surface height (SSH) data to reflect the nature of the barotropic and geostrophic response, characterized by a broad SSH trough20,21. Sun et al. 18 examined the effects of super typhoons on the pre-typhoon cyclonic ocean eddies (COEs) in the western North Pacific using satellite data and Argo floats. Cheng et al. 22 investigated mesoscale COEs induced or strengthened by slow-moving super typhoons using satellite SSH data. They reported that these TC-induced COEs exhibited stronger intensity and longer lifespans compared to the average characteristics of regular eddies generated in open oceans.

The studies discussed above focused on describing kinematic change, such as eddy strength, size, and kinetic energy, in relation to modifications in SSH signals. However, none of these studies provided direct evidence that confirms and describes the linkage between TCs and the subsequent generation or perturbation of COEs, because using remote sensing data or in-situ observations often suffers from insufficient temporal or spatial coverage. For instance, Sun et al. 7 explored the impacts of typhoon Namtheun (2004) on the ocean using limited Argo salinity and temperature profiles. The low temporal resolution (approximately a 5-days repeat cycle) of their observations not only failed to capture the inertial oscillation signals (as discussed in Sun et al. 7) but also raises questions about the reliability of their descriptions of the two-stage processes of the oceanic response to typhoon Namtheun (2004).

Lu et al. 15 investigated the strength and spatial structure of isopycnal undulations and potential vorticity changes linked to the typhoon-induced geostrophic response using a linear, two-layer theory and an ocean general circulation model. Rudzin and Chen12 further described the dynamic process of the eradication of a warm core mesoscale eddy following the passage of Hurricane Irma. These studies primarily focused on either the disappearance of an eddy or the impact of TC on preexisting COEs, rather than addressing the generation of new COEs induced purely by TC passages. In addition, the ability of TCs to induce or strengthen COEs remains controversial. On the one hand, Lu et al. 15 suggested that the strength and cross‐track length scale of the geostrophic response closely match those of background eddies, highlighting the potential for a TC to perturb underlying eddies in the ocean. On the other hand, Sun et al. 18 found that the effect of typhoons on COE strength is relatively weak, as only about 10% of COEs were significantly influenced by super typhoons in their study. In conclusion, the capability of TCs to induce or strengthen COEs remains an unresolved issue and requires further direct research.

This study focuses on the process of typhoon-induced mesoscale cyclonic eddy (TIME) in the western North Pacific. As a first step, a new generation global mesoscale eddy trajectory atlas and TC data were analyzed to preliminarily identify possible TIME events. Subsequently, numerical modeling using a regional ocean modeling system (ROMS) was conducted to reconstruct the background oceanic environment during representative TIME candidates. Following this, the causal relationship between TCs and the resulting COEs, a key target of this study, was systematically examined through a series of semi-idealized experiments. Afterward, the dynamic linkage between the velocity and density fields during the generation of a typical TIME event was unveiled by energy budget analysis through the examination of time-varying kinetic energy (KE) and available potential energy (APE). Vorticity budget analysis was also carried out to identify the different processes that contribute to the changes in the time-varying vorticity field during the generation of COEs triggered by TC passages. These detailed numerical modeling experiments and analyses help to uncover the key mechanisms governing the generation of TIME.

Results

Simulations of Three Possible TIME Events

In this section, the background environments of three TIME candidates (see Methods section) corresponding to typhoons Rosie (1997), Nida (2009), and Ma-On (2011) were reconstructed using the ROMS through standard experiments RosieSTD, NidaSTD, and Ma-OnSTD, respectively. Typhoon Rosie initially formed as a tropical storm near 10°N on July 18, 1997. It traveled northward and was officially upgraded to a typhoon on July 22 (Fig. S1 in the SOM). The typhoon moved slowly near 18°N and 132°E, where a COE subsequently formed nearby. Fig. S2a illustrates the model-simulated evolution of a COE generated during the passage of typhoon Rosie.

Figure S2b shows the time-varying SSHAs and AGCs obtained from satellite altimeters for the same period. The SSHAs and AGCs retrieved from satellite altimeter observations do not immediately reflect the changes observed in the model-simulated SSHAs and currents. This discrepancy in the SSHAs arises because daily satellite altimeter observations are essentially reprocessed product from repeat satellite cycles with a period of approximately 10 days, rather than actual daily measurements, and the geostrophic adjustment process might cause the actual velocity to deviate from the AGCs. However, the model-simulated characteristics and strengths of the negative SSHAs and current responses show considerable consistency with satellite observations once the COE reaches its mature stage in the geostrophic balance status, providing preliminary independent validation of the model results.

Figure S3a shows the model-simulated evolution of the COE potentially generated by the passage of typhoon Nida, the strongest typhoon of 2009. Typhoon Nida formed near 6°N on November 21, 2009, and headed northwest. On November 25, it rapidly intensified into a Category 5 typhoon, then slightly weakened to Category 4. By November 27, Nida re-intensified to Category 5 and moved slowly around 19°N and 138°E (see Fig. S1 in the SOM). Subsequently, Nida lingered for nearly 2 days, and a strong COE formed beneath its path.

The model-simulated evolution of upper-layer currents for typhoon Nida was compared with simultaneous satellite observations of SSHAs and AGCs (Fig. S3b). The comparison shows good agreement between the model simulations and satellite observations regarding the evolution of SSHAs and currents during Nida’s passage. The consistency in the evolution of SSHA and currents during the passage of Ma-On in 2011 between the model simulations and the satellite observations is shown in Fig. S4 in the SOM. These results suggest that the background environments corresponding to the three representative TIME candidate events during the passage of typhoons Rosie (1997), Nida (2009), and Ma-On (2011) were realistically reconstructed using ROMS through experiments RosieSTD, NidaSTD, and Ma-OnSTD, respectively.

A Pure TIME Event

As previously mentioned, three TIME candidates associated with typhoons Rosie (1997), Nida (2009), and Ma-On (2011) offer a rare opportunity to gain a deeper understanding of the real process of TIME in these cases. To achieve this, a pure TIME event must first be identified. A dynamic approach based on numerical modeling makes this possible. Firstly, the background environments associated with the three TIME candidate events, reconstructed in the standard experiments, were illustrated in column B of Fig. 1. The characteristics, including variabilities of SSHAs and currents, corresponding to the COEs at their mature stages (approximately one week after their generation), were highlighted to facilitate a systematic comparison (Fig. 1). These characteristics were collected on July 31, 1997, December 10, 2009, and July 31, 2011, corresponding to typhoons Rosie, Nida, and Ma-on, respectively. For more detailed experimental information, see Table S2 in the SOM. Due to the planetary (beta) effect, eddies move westward23. Consequently, in Fig. 1, the eddies are predominantly located on the west side of the typhoon trajectories.

Comparison of satellite-observed SSHAs (m) and AGCs (ms-1) (column A) with outputs from standard runs (column B) and idealized experiments, EXPNOTC (column C) and EXPTCONLY (columns D), during the mature stage of COEs corresponding to typhoons Rosie (upper row), Nida (middle row), and Ma-On (bottom row). The color shadings represent the SSHAs, while black contours indicate the possible COE centers with negative SSHAs. The black lines with hollow circles show the typhoon trajectories. The red rectangle in column B for typhoon Nida marks the region for vorticity budget calculation, and the green line indicates the transect location for energy analysis.

Subsequently, the simultaneous satellite-derived SSHAs and AGCs were shown in column A of Fig. 1 to aid the comparison. Moreover, in addition to standard experiments, two more semi-idealized experiments were designed and conducted to systematically examine the causal relationship between TCs and the resulting COEs. For the semi-idealized experiment settings, please refer to Methods section and Table 1. The results from these semi-idealized experiments were shown in columns C (for EXPNOTC) and D (for EXPTCONLY) of Fig. 1, respectively.

A realistic TC-induced COE process can be obtained for consequential detailed analysis by cross-comparing COEs from all experiments (see Fig. 1). First, the comparison reveals that the COEs during typhoons Rosie and Ma-On were primarily triggered by oceanic conditions. This is evident from the fact that the characteristics of COEs for these two events were reproduced even without the contribution of TC momentum wind forcing (column C in Fig. 1). During typhoon Rosie, wind forcing (as shown in column D of the Rosie) contributed to some variations in SSHA, but the marine environment also played a significant role. Therefore, this example is not suitable for subsequent analyses. Consequently, these cases do not represent ideal TIME events. In contrast, typhoon wind forcing plays a dominant role in the generation of COE during Nida (see the middle panel in Fig. 1). Additionally, NidaTCONLY exhibits a pattern similar to NidaSTD (Fig. 1), indicating that oceanic forcing contributes less to COE generation compared to TC momentum wind forcing. This suggests that the wind forcing associated with typhoon Nida serves as a primary trigger for a realistic TIME, with minimal additional influence from oceanic conditions such as preexisting eddies, currents, jets, upwelling, and stratification.

Progression of TIME by Typhoon Nida

Compared to the other two TC cases, Nida provides a more favorable environment for an in-depth exploration of the dynamic process of TIME. Fig. 2 illustrates the evolution of the model-simulated horizontal velocity and temperature fields from EXPSTD at selected depths of 0 (top-level), 40 (mid-level), and 80 m (bottom-level) during the passage of typhoon Nida. These depths are chosen to represent the characteristics of the mixed layer (ML), the ML-thermocline interface, and the upper thermocline (see Fig. S5 in the SOM). As time progress, a complete COE structure forms and extends throughout the water column gradually, driven by the influence of TC Nida (Fig. 2c).

The oceanic current response in the upper layer can be categorized into three major components. 1) Flow Divergence: The momentum response primarily involves current divergence in the ML around the TC’s footprint, resulting in net water transport outward from the storm center (top-level of Fig. 2a and c). At these times, the structure of a cyclonic eddy is not evident in the current field. Additionally, the current divergence in the ML decreases and reverses direction, generating significant vertical shear across the ML base and the top of the seasonal thermocline. This vertical current shear drives the vertical mixing process4,24, inducing substantial cooling (bottom-level Fig. 2a). 2) Ekman Pumping: The spatial variability of the wind at the sea surface results in varying Ekman transports. To conserve mass, this spatial variability generates vertical velocities at the top of the Ekman layer. Consequently, the current divergence in the ML tied to positive wind stress curl (WSC) leads to upwelling of cooler water from the lower layer. 3) Geostrophic Balance: On November 29, a cyclonic current pattern associated with geostrophical balance began to develop. Concurrently, the SSH amplitude tended to decrease drastically (Fig. 3), indicating a stable barotropic response due to surface divergence in the ML combined with a baroclinic response resulting from the uplift of colder, higher-density subsurface water20,25. With the difference in SSH, a pressure gradient force was generated to establish a geostrophic flow. This is evident as the surface currents transition from being divergent (as shown in top-level of Fig. 2a) to exhibiting a circular rotation (top-level of Fig. 2c).

In addition to the geostrophic current that was being developed during the geostrophic adjustment process, caused by the SSH anomaly, the horizontal differences in the seawater density also create a pressure gradient force below the sea surface26. The complete geostrophic equations, which account for both barotropic and baroclinic components, were summarized in Equation S6 in the SOM. Fig. 4 shows the continuous progression of the calculated geostrophic current as derived from Equation S6. It is evident that although the SSH began to decrease on the 28th (Fig. 3), there was not much difference relative to the surrounding area at that time. The Ekman pumping had not yet reached the surface, and geostrophic balance had not been well established. By the 29th, the SSH continued to drop and started to differ noticeably from the surrounding SSH (Fig. 3). The cold water brought by the upwelling approached the surface. Concurrently, the geostrophic current began to form around the negative SSH anomaly. This current became stabilized on and after the 30th through the geostrophic adjustment, gradually moving westward due to the planetary (beta) effect23, indicating that the structure of the COE was tending towards stability.

The wave phase speed of the first baroclinic mode due to oceanic density changes between the ML and the thermocline was considered an important parameter governing the upper-layer current response to a storm passage20,21,27. Nida was a Category 4 typhoon strolling around 19°N, 139°E with an average translation speed of approximately 1 m/s. Meanwhile, the first baroclinic wave speed (Equation S7 in the SOM) in the region was calculated as approximately 2.9 m/s. In the case of TC moving slower than the first baroclinic mode phase speed, geostrophically balanced currents would be generated by the positive WSC causing an upwelling of the cooler water and outward upper ocean transport away from the storm track (see the schematic plot - Fig. 1 in Shay21). Our results based on realistic TIME events show agreement with upper ocean circulation patterns obtained by previous studies based on theoretical models20,21.

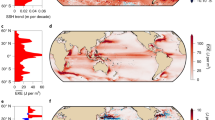

Energy analysis of TIME

To better understand the dynamic linkage between TC-induced currents and baroclinicity during the generation of consequential COE, kinetic energy (KE, Eq. 1) and available potential energy (APE, Eq. 2) quantities are estimated. APE in the ocean is defined as the difference between the potential energy in the current state and that in the reference state12,28,29,30. For instance, the formation of a COE due to TC passage will result in an increase in APE because it represents an anomaly relative to the long-term climatological reference state. Additionally, the input of KE into the ocean from TC stirring causes isopycnals to tilt, increasing APE relative to the stable reference state (indicating conversion of KE to APE). KE and APE are computed at each grid point and averaged along the zonal transect through the center of the COE (green line in Fig. 1) for the time-varying outputs, following the methods of Rudzin and Chen12:

where u is the current velocity in the zonal direction, positive towards the east; v is the current velocity in the meridional direction, positive towards the north (m/s); APE is computed as the difference between the potential energy in the current state and that in the climatological reference state; g is the acceleration due to gravity; ρ0 is the reference density of seawater; ρinsitu is the instantaneous density calculated from the modeled temperature and salinity at each grid point; and \(\bar{\rho }\) is the average density calculated from the temperature and salinity at each grid point using the monthly climatology from the Global Ocean Physics Reanalysis provided by CMEMS.

Figure 5 shows the time series of KE and APE across the COE at depths of 20, 40, 60, 80, 100, and 200 meters. These depth levels were selected based on the velocity fields, where the largest velocity gradients occurred. KE and APE are near zero before the TC passage at all depths. As typhoon Nida approaches the location where the COE forms, the currents start to respond, and KE rapidly increases at all depths, peaking as the TC center passes through (with KE peaking at noon on November 28). This increase in KE is attributed to the TC wind forcing, which imparts momentum into the ML and creates uniform ML currents. The near-synchronous KE peaks (occurring on November 28, as shown in Fig. 5) at different depths confirm this inferred process.

In the earlier Progression of TIME by Typhoon Nida section, the Ekman pumping was triggered by a positive WSC induced by Nida. Later, the upwelling of deeper cold and denser waters due to Ekman pumping resulted in the inclination of the thermocline and an increase in baroclinity. According to Eq. 2, this process eventually causes an increase in APE. In Fig. 5, KE at different depths rapidly and nearly synchronously increases from November 27 to November 29. Subsequently, KE begins to decrease and is partially converted into APE. This process aligns with the described TC wind forcing, which drives upwelling, inclines the thermocline, and increases APE through enhanced baroclinicity. In addition, these observations are consistent with the initial stage of COE generation discussed in Progression of TIME by Typhoon Nida section.

After the KE–APE transitions, APE reaches its maximum on November 30, just before the TC center departs (Fig. S1 in the SOM). During this time, KE is converted into APE, leading to a decrease in KE, which reaches its lowest value. However, the APE peaks at slightly different times at various depths. APE at shallower depths shows a more pronounced peak compared to deeper regions. This difference is attributed to the temperature gradient created by cold-water upwelling, which is strongest near the sea surface and decreases with depth. By November 30, KE has minimized, and turbulent mixing from wind forcing also diminishes with the departure of the TC center. Concurrently, APE at all depths reaches a maximum, indicating the mature stage of the COE with the strongest baroclinicity. The period from November 28 to 30 can be defined as the spin-up stage of the TIME event. After the TC center leaves on December 1, APE at all depths gradually decreases and stabilizes as wind-induced currents subside. Additionally, the peaks of APE propagate from the surface to deeper layers, reflecting the fact that wind forcing is concentrated in the upper ocean layers. During the geostrophic adjustment, the internal inertial waves appeared apparently, might dissipated the kinetic energy of the TIME (Fig. 5).

Here, we summarize the mechanisms leading to the generation and destruction of the COE. During the TC passage, momentum induced by TC stirring within the ML gradually increases the KE. Ekman pumping was triggered by the positive WSC associated with typhoon Nida. An input of KE into the ocean via Ekman pumping would cause an inclination of isotherms (isopycnals) and an increase in baroclinity, which in turn raises APE. This continuous conversion of KE into APE occurs during the initial stage of COE development from November 28 to November 30 (Fig. 2). As the COE matures, it reaches a geostrophically balanced state, characterized by currents generated by positive WSC. Meanwhile, the upwelling of the cooler and denser subsurface water and upper ocean transport directed away from the storm track all contribute to the establishment of geostrophic balance (Fig. 2 and Shay21). Finally, once the storm leaves the COE location, APE gradually decreases back to zero at all depths, and the COE circulation weakens and eventually disappears12.

Vorticity budget analysis

In practice, the generation of COE by the TC passage requires a sufficient supply of positive vorticity in the background. Processes that create a positive vorticity tendency promote the formation of COE circulation. In addition to energy analysis, the vorticity budget diagnoses were applied to delineate the processes contributing to COE formation during the passage of TC Nida. Fig. 6 shows time series of (a) vertical diffusion term (ζvdif), (b) the stretching term (ζdiv), (c) horizontal advection of absolute vorticity (ζhadv), (d) vertical advection of relative vorticity (ζvadv), (e) the tilting term (ζtilt), (f) summation of (a)–(e), and (g) vorticity tendency, with respect to depth from the vorticity budget analysis. These terms were calculated and averaged within a 3° × 3° area centered on the COE (19.12°N, 138.5°E; marked by red rectangle in Fig. 1). A dashed gray line indicates the time of the passage of TC center over the COE.

Time series of (a) vertical diffusion term, (b) stretching term, (c) horizontal advection, (d) vertical advection, (e) tilting term, (f) the summation of terms (a–e), and (g) vorticity tendency with respect to depth from the vorticity budget analysis, averaged within a 3° × 3° area centered on the COE (19.12°N, 138.5°E, units: s-2). The dashed gray line indicates the time of the passage of TC center over the COE. Green line in Fig. 6a and Fig. 6b denoted time series of depth-averaged (20-140 m) relative vorticity and divergence, respectively.

The contributions of the individual terms in the vorticity budget are shown in Fig. 6a–e. Vertical diffusion term is the primary contributor to the positive vorticity needed for the spin-up of COE during the generation of TIME. The sharp increase in depth-averaged relative vorticity (green line in Fig. 6a), showing a great agreement with the appearance of strong positive vorticity anomaly contributed by vertical diffusion term (ζvdif, color shading in Fig. 6a), suggest a consistent result. Previous studies have shown that during the forced period (ranging from the onset of TC passage to about half an inertial period post-forcing) intense wind stress generates strong upper ocean currents, leading to turbulent and shear-induced mixing12,20. This process provides the source of positive relative vorticity around and within the red rectangular region for vorticity budget analysis, and is transported to the center through horizontal advection (see Fig. S6). In contrast, the divergence and vertical advection terms provide negative vorticities, mainly affecting the upper layer (0–50 m) and the subsurface layer (70–100 m), which may partially inhibit COE circulation development. In addition, the calculated sum of the five terms (Fig. 6f) not only reconstructs the two main positive vorticities increase events (11/27 and 11/29) but also maintains the same order of magnitude as the vorticity tendency term (Fig. 6g) during the reanalysis period. Furthermore, it accurately captures the alternating distribution characteristics of positive and negative signals. The alternative positive and negative signals resulted from a typical near-inertial oscillation behind a TC passage tied to coupling between TC wind-forcing, the surface mixed layer, and the thermocline31,32.

Generally speaking, the decomposition of the upper ocean vorticity budget highlights the key components that cause differences during the process of TIME and provides context as to the individual contribution of different mechanisms. By contrast, direct vorticity tendency output from model simulation helps to describe the complete responses of relative vorticity variation to TC. According to Glenn et al. 33 and Lin et al. 11, the discrepancy between Fig. 6f and could be attributed mainly to factors such as the time intervals used for integration and time-varying vertical coordinates in the ROMS, as well as the partial influence of friction. On the other hand, Fig. 6f demonstrated a typical near-inertial oscillation behind a TC passage, resulting from coupling between wind-forcing, the surface mixed layer, and the thermocline31,32.

Referring to the dynamic processes of the appearance of TIME, the leading positive vorticity due to vertical diffusion term and horizontal advection (Fig. 6a, c), which favored the generation of COE in the upper ocean, primary results from the positive WSC and the subsequent formation of cyclonic currents due to geostrophic balance. Meanwhile, vertical vorticity advection (Fig. 6d), which contributed to the negative vorticity in the subsurface layer, is associated with the vertical current shear across the ML base and the top of the seasonal thermocline, driven by TC stirring of the ML current, as noted in Price24 and Shay21. The negative vorticity from the stretching term (ζdiv, Fig. 6b) arises from the process where the TC drives surface seawater to diverge outward (see Fig. 2b, c and Shay21). Time series of depth-averaged (20-140 m) divergence (green line in Fig. 6b) shows consistent pattern. From the comparison of divergence and stretching term (ζdiv), it shows that the variation of stretching term (color shading) is closely related to the background current divergence (green line in Fig. 6b). Because, as seawater diverges, vorticity spreads outward with the water flow, leading to a decrease in vorticity due to the conservation of angular momentum. Both vertical advection and divergence terms act as natural dampers, counteracting the development of positive vorticity and stronger COEs. Although the tilting term reflects positive vorticity created by the tilting of horizontal vorticity due to vertical current shear, it plays a minor role in promoting COE generation. A schematic summarizing the different processes leading to the generation of TIME is presented in Fig. 7.

Overall, the process of TIME is a continuous progression of energy conversion from KE to APE that is responsible for maintaining the COE for a longer lifespan. Based on Eqs. 1 and 2 for calculating KE and APE, and the theory reported by Geisler20, it is suggested that the strength and spatial scale of TIME, primarily influenced by the translation speed and intensity of the TC, play crucial roles in determining the amount of energy conversion from KE to APE and the lifespan of a typical TIME event. Generally, a stronger typhoon with a slower translation speed results in a more intense COE with a longer lifespan. The sensitivity of COE to varying TC intensities and translation speeds, based on a suite of idealized experiments, is illustrated in Fig. S7 in the SOM. The method of conducting the translation speed experiments is straightforward. The scenario of a typhoon moving 2 times faster relative to the original wind forcing distribution and progression can be retrieved by using the same typhoon wind forcing and moving progression but modifying their temporal intervals from 6 h to 3 h.

Discussion

In this study, we investigated the dynamic process of TIME in the western North Pacific by systematically analyzing a 24-year period of typhoon and eddy trajectory data from 1995 to 2018. We identified three representative TIME candidates potentially generated by typhoons Rosie (1997), Nida (2009), and Ma-on (2011). Through comparisons of standard and semi-idealized model simulations with observations, we confirmed that a realistic TIME event was triggered by the passage of typhoon Nida. These simulations provided valuable insights into the dynamic air-sea interaction processes responsible for the formation of TIME and COE.

The energy analysis demonstrates that the COE triggered by typhoon Nida follows a typical progression of energy transition from KE to APE, which sustains the COE for an extended period. Initially, KE increases as the TC wind forcing imparts momentum into the ML, leading to uniform ML currents. Subsequently, Ekman pumping, driven by a positive WSC associated with Nida, induces upwelling of colder, denser deep waters. This upwelling causes the isotherms to uplift, resulting in the inclination of the thermocline and a rapid increase in baroclinity. This process ultimately leads to an increase in APE. Additionally, the timing and patterns of energy rise, fall, and exchange align well with the evolution of TIME observed in the current and SSH fields.

In practice, the initial generation (spin-up) of COE during a TC passage requires a sufficient supply of positive vorticity. The analysis of vorticity budget terms helps identify the processes contributing to the formation of the COE associated with typhoon Nida. Vertical diffusion and horizontal advection primarily provide the positive vorticity necessary for the spin-up of the COE. In contrast, divergence and vertical advection contribute negative vorticity in the upper layer (0–50 m) and the subsurface layer (70–100 m), respectively. These negative contributions partially inhibit the development of COE circulation. As natural dampers, divergence and vertical advection offset the continued accumulation of positive vorticity, thereby moderating the development of stronger COEs.

Recently, Patricola34 observed a global slowdown in the speed at which TCs travel over the past seven decades. Wang et al. 35 reported an increasing trend in TC strength, with a rise of 1.8 m/s per decade across the global intensity distribution, based on global surface drifter data. On the one hand, these changes may amplify TC-related threats through increased regional rainfall and wind impacts. On the other hand, the combination of more intense and sluggish TCs could lead to a higher frequency of TIME events and the formation of stronger and more prolonged TIMEs according to the results demonstrated in this study. This implies that, under the current trend of global warming, we may see more frequent and intense TIMEs in the near future. Nevertheless, as noted in Chu et al. 36, changes in CO2 concentrations may reduce the overall frequency of TCs. The overall impact of TIMEs depends on various factors, including TC occurrence, translation speed, intensity, and the regions impacted by TCs37,38. Therefore, closer monitoring of the evolving trends in these potential factors will be essential in the future.

In addition, mesoscale eddies significantly influence short-term climate across various pathways and timescales7,8,12,39. For instance, Agulhas eddies transport water with Indian Ocean properties into the South Atlantic, while eddies contribute substantially to oceanic poleward heat transport across the Antarctic Circumpolar Current in the Southern Ocean40. On the other hand, Chen and Yu41 indicated that mesoscale eddies are dynamically important features because they transport nutrients and displace heat within the Earth’s climate system. They estimate that the zonal integration of meridional heat transport (MHT) associated with mesoscale features, primarily mesoscale eddies, reaches approximately 10-20 terawatts between 20-40°N latitude, although the total mesoscale contribution to MHT is significantly smaller ( ~ 2 order) compared to the MHT contributed by the large-scale component such as western boundary current system (see Figs. 2 and 4 in Chen and Yu41). Nevertheless, coupled with the more direct impact of COEs on ocean environments, air-sea interactions12,13,15,42, and the advection and supply of heat, moisture, energy, and nutrients10,11,43, TIMEs with stronger intensity and longer lifespans compared to typical COEs deserves definitely more attention.

On the other hand, geoengineering and disaster management related to TIME represent another promising avenue worth exploring44,45. For instance, as marine heatwaves (MHWs) increasingly threaten marine ecosystems and coastal economies46,47, a deeper understanding of TIME mechanisms could provide innovative mitigation strategies. It is conceivable that artificially inducing cyclones over oceans (anthropogenic cyclones) might generate COEs that dissipate excess heat48, potentially mitigating MHWs. While this concept remains theoretical and presents significant ethical and practical challenges, it highlights the potential value of this study in addressing pressing climate-related issues.

This study discusses the potential role of COE in influencing remote large-scale climate patterns, particularly in light of the findings indicating an increasing frequency and intensity of TIME by combing the results demonstrated in this study and related studies that indicate a trend of sluggish and more intense TCs in a warming world. Previous studies have clearly established that COE contributes to poleward mass and heat transports10,41, underscoring the significance of both COE and TIME in shaping remote climate impacts. This research sheds new light on the processes associated with the generation of TIME; however, aspects such as seasonal characteristics and interannual variability remain inadequately defined in terms of their influence on the process of TIME. Further investigations are needed to clarify these processes, highlighting the necessity for additional studies in this area.

Methods

Typhoons

Typhoon data in the western North Pacific from 1995 to 2018 were used to correlate with the global mesoscale eddy trajectory atlas for identifying possible TIME events in the first stage. These data were obtained from the Joint Typhoon Warning Center best track dataset (https://www.metoc.navy.mil/). The information contained in individual best-track data includes the time-varying TC center position, wind radius, central pressure, and maximum sustained wind speed in 6 h temporal intervals.

Mesoscale eddy product and sea surface height data

A new generation global mesoscale eddy trajectory atlas was applied in this study to detect the appearance and eradication of mesoscale eddies during individual TC passages in the western North Pacific. This atlas contains related information including eddy position, amplitude, speed, effective radius, associated SSH contours, and speed profile. It was developed based on the algorithm proposed by Mason et al. 49 using altimetry data and is distributed by the Archiving, Validation, and Interpretation of Satellite Oceanographic (AVISO). Further details on the application and validation of this product can be found in Pegliasco et al. 50. Several versions of the mesoscale eddy trajectory atlas are available. The version used here was the product that merges delayed-time model data from multi-satellite missions with better accuracy50. Multiple satellites merged sea surface height anomaly (SSHA) and absolute geostrophic current (AGC) at a spatial resolution of 0.25° × 0.25° were obtained from the AVISO. The daily AVISO SSHA was used to systematically characterize the instantaneous state of the upper ocean under the influence of TC passages, including the evolution of eddies, their strengths, sizes, and kinetic energies.

Candidates of TIMEs

In this study, TCs with intensities stronger than Category 1 on the Saffir-Simpson hurricane wind scale were matched with the global mesoscale eddy trajectory atlas to initially identify potential TIME events from 1995 to 2018. The preliminary analysis revealed a total of 69 COE cases that were potentially generated or amplified from neutral conditions (no SSHA over ±5 cm18) following typhoon passages. Subsequently, to find the most representative candidates for dynamic reconstruction, a series of analysis steps were further applied: 1. The initiation of the COE must strictly coincide with TC passage within a 1° square area. 2. The sea surface characteristic in neutral condition must last for more than 5 consecutive days before a COE is generated. 3. The spin-up COEs must have an amplitude greater than 7.5 cm51. 4. The negative SSH anomaly (stronger than 7.5 cm) must last for more than 14 consecutive days following the TC passage. 5. The COEs must appear in the open ocean rather than in shelf or coastal regions.

Only events meeting all these criteria simultaneously were considered representative TIME candidates for further analysis. During the study period, five events corresponding to typhoons Rosie (1997), Haitang (2005), Nida (2009), Ma-On (2011), and Nuri (2014) were identified as possible TIME events (Table S1 in the SOM). Among them, events associated with typhoons Rosie, Nida, and Ma-On exhibited the largest COE amplitude differences and were therefore selected for detailed dynamic reconstruction and systematic analysis.

ROMS model configurations and experiments design

Relative to sparse and intermittent observations, model simulation typically plays a key role in providing a more continuous and comprehensive understanding of ocean processes5,42,52. In this study, numerical modeling based on ROMS was carried out to reconstruct the background environment during the generation of representative TIME candidates (EXPSTD) and clarify the possible dynamic linkage between TC and underlying current response (e.g., generation of COE). The ROMS is a free-surface, three-dimensional primitive equation ocean model with curvilinear coordinates. A non-local, K-profile planetary boundary layer scheme was applied to parameterize subgrid-scale mixing processes. The model domain covered the region of 18° longitude by 18° latitude and centered at individual TC centers with a horizontal resolution of approximately 6 km. In the vertical direction, 20 s-coordinate levels were unevenly distributed to better resolve the upper ocean. Initial and lateral boundary conditions were derived from the Hybrid Coordinate Ocean Model (HYCOM)/Navy Coupled Ocean Data Assimilation (NCODA) outputs. Momentum wind forcing and atmospheric parameters were provided by the hourly Modern-Era Retrospective analysis for Research and Applications, version 2 (MERRA-2) product, which has a grid resolution of 0.5° latitude × 0.625° longitude and is available at https://disc.gsfc.nasa.gov/. The model bathymetry was created using ETOPO-2 global ocean bottom topography.

Semi-idealized experiments were conducted to systematically examine the causal relationship between TCs and the resulting COEs for representative events. The first set of experiments focused on the influences of factors other than TC direct wind forcing (EXPNOTC). This was achieved by setting momentum forcing to zero at the TC center within a 4° × 4° area. Given that TCs in the western North Pacific have an average size of 203 km53, this adjustment ensures that the direct effects of the TC’s wind forcing are excluded. Another set of experiments investigated the effects of removing oceanic mesoscale influences while keeping other forcing factors constant by replacing the underlying 3D oceanic conditions with climatological fields (EXPTCONLY). For EXPTCONLY, the climatological 3D fields for temperature, salinity, and currents fields were obtained from the Copernicus Marine Environment Monitoring Service (CMEMS) Global Ocean Physics Reanalysis. Detail semi-idealized experiments can see in Table 1.

Relative vorticity equation

Relative vorticity (ζ = ∂v/∂x − ∂u/∂y) and the specific components of the vorticity budget were calculated to elucidate the processes driving changes in the relative vorticity field during the generation of TIME, as described by Eq. 3. It is worth noting that Eq. 3 is a simplified version derived from the full vorticity equation under the viscid condition (Equation S1 in the Supplementary Online Material, SOM). For the specific simplification process, please refer to Equations S1 to S5 in SOM or Katopodes54.

where \(f\) is the Coriolis parameter, τy = ρKm∂v/∂z, τx = ρKm∂u/∂z, and Km denotes the vertical viscosity coefficient. Equation 3 comprised the (A) horizontal advection of absolute vorticity (ζhadv), (B) vertical advection of relative vorticity (ζvadv), (C) the stretching term (ζdiv), (D) the tilting term (ζtilt), and the (E) vertical diffusion term (ζvdif). The stretching term represents the weakening (or strengthening) of relative vorticity due to horizontal velocity divergence (or convergence), while the tilting term represents relative vorticity generated by the tilting of horizontal vorticity due to vertical shear in the current, and the diffusion term represents vorticity generated by the vertical viscosity effect. Finally, these terms were estimated at each grid point and averaged over the cross-section through the COE, as indicated by the red rectangle in Fig. 1.

Data Availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Jaimes, B. & Shay, L. K. Mixed Layer Cooling in Mesoscale Oceanic Eddies during Hurricanes Katrina and Rita. Mon. Weather Rev. 137, 4188–4207 (2009).

Jaimes, B. & Shay, L. K. Enhanced Wind-Driven Downwelling Flow in Warm Oceanic Eddy Features during the Intensification of Tropical Cyclone Isaac (2012): Observations and Theory. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 45, 1667–1689 (2015).

Lin, I.-I. et al. The Interaction of Supertyphoon Maemi (2003) with a Warm Ocean Eddy. Mon. Weather Rev. 133, 2635–2649 (2005).

Shay, L. K., Goni, G. J. & Black, P. G. Effects of a Warm Oceanic Feature on Hurricane Opal. Mon. Weather Rev. 128, 1366–1383 (2000).

Zheng, Z.-W. et al. Effects of preexisting cyclonic eddies on upper ocean responses to Category 5 typhoons in the western North Pacific. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 115, (2010).

Chelton, D. B., Schlax, M. G. & Samelson, R. M. Global observations of nonlinear mesoscale eddies. Prog. Oceanogr. 91, 167–216 (2011).

Sun, L., Yang, Y.-J., Xian, T., Wang, Y. & Fu, Y.-F. Ocean Responses to Typhoon Namtheun Explored with Argo Floats and Multiplatform Satellites. Atmos. Ocean 50, 15–26 (2012).

Frenger, I., Gruber, N., Knutti, R. & Münnich, M. Imprint of Southern Ocean eddies on winds, clouds and rainfall. Nat. Geosci. 6, 608–612 (2013).

Dong, D. et al. Mesoscale Eddies in the Northwestern Pacific Ocean: Three-Dimensional Eddy Structures and Heat/Salt Transports. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 122, 9795–9813 (2017).

Zhang, Z., Wang, W. & Qiu, B. Oceanic mass transport by mesoscale eddies. Science 345, 322–324 (2014).

Lin, J.-Y. et al. Satellite observed new mechanism of Kuroshio intrusion into the northern South China Sea. Int. J. Appl. Earth Observation Geoinf. 115, 103119 (2022).

Rudzin, J. E. & Chen, S. On the dynamics of the eradication of a warm core mesoscale eddy after the passage of Hurricane Irma (2017). Dyn. At. Oceans 100, 101334 (2022).

Wu, C.-C., Lee, C.-Y. & Lin, I.-I. The Effect of the Ocean Eddy on Tropical Cyclone Intensity. J. Atmos. Sci. 64, 3562–3578 (2007).

Zheng, Z.-W., Ho, C.-R. & Kuo, N.-J. Importance of pre-existing oceanic conditions to upper ocean response induced by Super Typhoon Hai-Tang. Geophys. Res. Lett. 35, (2008).

Lu, Z., Wang, G. & Shang, X. Strength and Spatial Structure of the Perturbation Induced by a Tropical Cyclone to the Underlying Eddies. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 125, e2020JC016097 (2020).

Yang, Y.-J. et al. Impacts of the binary typhoons on upper ocean environments in November 2007. J. Appl. Remote Sens. 6, 063583 (2012).

Shang, X., Zhu, H., Chen, G., Xu, C. & Yang, Q. Research on Cold Core Eddy Change and Phytoplankton Bloom Induced by Typhoons: Case Studies in the South China Sea. Adv. Meteorol. 2015, e340432 (2015).

Sun, L. et al. Effects of super typhoons on cyclonic ocean eddies in the western North Pacific: A satellite data-based evaluation between 2000 and 2008. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 119, 5585–5598 (2014).

Walker, N. D. et al. Slow translation speed causes rapid collapse of northeast Pacific Hurricane Kenneth over cold core eddy. Geophys. Res. Lett. 41, 7595–7601 (2014).

Geisler, J. E. Linear theory of the response of a two layer ocean to a moving hurricane. ‡. Geophys. Astrophys. Fluid Dyn. 1, 249–272 (1970).

Shay, L. K. Upper Ocean Structure: Responses to Strong Atmospheric Forcing Events. in Encyclopedia of Ocean Sciences (Second Edition) (ed. Steele, J. H.) 192–210 (Academic Press, Oxford, 2009). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-012374473-9.00628-7.

Cheng, Y.-T., Tseng, R.-S., Chang, Y.-C. & Chen, J.-M. Detecting Cyclonic Eddies Induced by Global Super Typhoons by Using Satellite Altimetry. J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 23, 15–24 (2018).

Cushman-Roisin, B., Tang, B. & Chassignet, E. P. Westward Motion of Mesoscale Eddies. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 20, 758–768 (1990).

Price, J. F. Upper Ocean Response to a Hurricane. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 11, 153–175 (1981).

Ginis, I. & Sutyrin, G. Hurricane-Generated Depth-Averaged Currents and Sea Surface Elevation. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 25, 1218–1242 (1995).

Stewart, R. H. Introduction to Physical Oceanography. (University Press of Florida, 2009).

Price, J. F., Sanford, T. B. & Forristall, G. Z. Forced Stage Response to a Moving Hurricane. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 24, 233–260 (1994).

Lorenz, E. N. Available Potential Energy and the Maintenance of the General Circulation. Tellus 7, 157–167 (1955).

Huang, R. X. Mixing and Available Potential Energy in a Boussinesq Ocean. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 28, 669–678 (1998).

Luecke, C. A. et al. The Global Mesoscale Eddy Available Potential Energy Field in Models and Observations. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 122, 9126–9143 (2017).

Price, J. F. Internal Wave Wake of a Moving Storm. Part I. Scales, Energy Budget and Observations. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 13, 949–965 (1983).

Sanford, T. B., Price, J. F. & Girton, J. B. Upper-Ocean Response to Hurricane Frances (2004) Observed by Profiling EM-APEX Floats. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 41, 1041–1056 (2011).

Glenn, S. M. et al. Stratified coastal ocean interactions with tropical cyclones. Nat. Commun. 7, 10887 (2016).

Patricola, C. M. Tropical cyclones are becoming sluggish. Nature 558, 36–37 (2018).

Wang, G., Wu, L., Mei, W. & Xie, S.-P. Ocean currents show global intensification of weak tropical cyclones. Nature 611, 496–500 (2022).

Chu, J.-E. et al. Reduced tropical cyclone densities and ocean effects due to anthropogenic greenhouse warming. Sci. Adv. 6, eabd5109 (2020).

Feng, X., Klingaman, N. P. & Hodges, K. I. Poleward migration of western North Pacific tropical cyclones related to changes in cyclone seasonality. Nat. Commun. 12, 6210 (2021).

Wang, S. & Toumi, R. Recent migration of tropical cyclones toward coasts. Science 371, 514–517 (2021).

Seo, H. et al. Ocean Mesoscale and Frontal-Scale Ocean–Atmosphere Interactions and Influence on Large-Scale Climate: A Review. J. Clim. 36, 1981–2013 (2023).

Beal, L. M., De Ruijter, W. P. M., Biastoch, A. & Zahn, R. On the role of the Agulhas system in ocean circulation and climate. Nature 472, 429–436 (2011).

Chen, Y. & Yu, L. Mesoscale Meridional Heat Transport Inferred From Sea Surface Observations. Geophys. Res. Lett. 51, e2023GL106376 (2024).

Kuo, Y.-C., Zheng, Z.-W., Zheng, Q., Gopalakrishnan, G. & Lee, H.-Y. Typhoon–Kuroshio interaction in an air–sea coupled system: Case study of typhoon nanmadol (2011). Ocean Model. 132, 130–138 (2018).

Frenger, I., Münnich, M. & Gruber, N. Imprint of Southern Ocean mesoscale eddies on chlorophyll. Biogeosciences 15, 4781–4798 (2018).

Ainsworth, T. D., Hurd, C. L., Gates, R. D. & Boyd, P. W. How do we overcome abrupt degradation of marine ecosystems and meet the challenge of heat waves and climate extremes? Glob. Change Biol. 26, 343–354 (2020).

Miller, J., Tang, A., Tran, T. L., Prinsley, R. & Howden, M. The Feasibility and Governance of Cyclone Interventions. Clim. Risk Manag. 41, 100535 (2023).

Smale, D. A. et al. Marine heatwaves threaten global biodiversity and the provision of ecosystem services. Nat. Clim. Chang. 9, 306–312 (2019).

Capotondi, A. et al. A global overview of marine heatwaves in a changing climate. Commun. Earth Environ. 5, 1–17 (2024).

Guo, Y., Bachman, S., Bryan, F. & Bishop, S. Increasing Trends in Oceanic Surface Poleward Eddy Heat Flux Observed Over the Past Three Decades. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2022GL099362 (2022).

Mason, E., Pascual, A. & McWilliams, J. C. A New Sea Surface Height–Based Code for Oceanic Mesoscale Eddy Tracking. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 31, 1181–1188 (2014).

Pegliasco, C. et al. META3.1exp: a new global mesoscale eddy trajectory atlas derived from altimetry. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 14, 1087–1107 (2022).

Wang, G., Su, J. & Chu, P. C. Mesoscale eddies in the South China Sea observed with altimeter data. Geophys. Res. Lett. 30, (2003).

Zheng, Z.-W. & Chen, Y.-R. Influences of Tidal Effect on Upper Ocean Responses to Typhoon Passages Surrounding Shore Region off Northeast Taiwan. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 10, 1419 (2022).

Lu, X., Yu, H. & Lei, X. Statistics for size and radial wind profile of tropical cyclones in the western North Pacific. Acta Meteorol. Sin. 25, 104–112 (2011).

Katopodes, N. D. Free-Surface Flow: Environmental Fluid Mechanics. (Butterworth-Heinemann, 2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-815489-2.00007-1.

Gill, A. E. & Niller, P. P. The theory of the seasonal variability in the ocean. Deep Sea Res. Oceanographic Abstr. 20, 141–177 (1973).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by National Science and Technology Council of Taiwan through grants of 111-2611-M-003-003-MY3.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.H. and Z.Z. proposed the project, Conceptualization, Methodology. J.L. and H.H. data curation, data processing, conducted numerical experiments. J.L., H.H. and Z.Z. Writing–original draft, Visualization. G.G., R.T. and J.P. worked on the manuscript’s editing and revision. All authors contributed to discussions of the results and the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lin, JY., Ho, H., Gopalakrishnan, G. et al. Typhoon induced mesoscale cyclonic eddy a long neglected linkage between atmosphere ocean and climate. npj Clim Atmos Sci 8, 64 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-00946-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-00946-9