Abstract

We assessed the seasonal prediction skill of tropical cyclone (TC) frequency over the western North Pacific by the large-ensemble SINTEX-F dynamical system. Although the prediction skills were limited, the correlation skill for the June–August prediction issued in early May was statistically significant around Okinawa and Taiwan. Particularly, the high TC activity in summer 2018 was well predicted. We found that the 2018 positive Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD) contributed to the predictability by the dynamical prediction system: suppressed convection in the eastern tropical Indian Ocean enhanced divergent wind from the eastern tropical Indian Ocean to the Okinawa and Taiwan areas. This helped to generate low pressure in the target area, which was favorable to the TC activity. The IOD contributions to the predictability were also seen in the correlation analyses in 1982–2022 and some case studies in 1994 and 1998. This could be useful for actionable early warnings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, the Philippines, and other southeast Asian coastal regions, tropical cyclones (TCs) are the most costly and deadly of natural disasters1. A successful prediction of the TC frequency in a season at least a few months ahead could help reduce the socio-economic losses through necessary mitigation measures and can benefit a range of industries, including insurance, agriculture, and tourism. Real-time seasonal forecasts of TC activity are provided by some agencies2. Such a research stream is becoming critically important in the low-latitude northwestern Pacific, where the typhoon intensity is expected to increase due to ongoing global warming3 and the impacts of the natural year-to-year variability are also expected to be more serious.

Previous works identified several potential sources of the seasonal predictability of TC frequency over the western North Pacific. The most famous phenomenon is El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO)1,4,5,6,7. In El Niño years, TC over the western North Pacific tends to be more intense and longer-lived than in La Niña years7. However, TC frequency in the western North Pacific does not change significantly between El Niño and La Niña years8. On the other hand, El Niño events display a diverse range of amplitudes, triggers, spatial patterns, and life cycles9. TC over the western North Pacific may be sensitive to this event-to-event diversity10. Because of the limited events, it is difficult to show high confidence in such assertion. However, some studies tried to show the possibility. For example, El Niño Modoki11 or Central Pacific (CP)-type El Niño12 can induce substantial increases in TC duration, intensity, and frequency over the western North Pacific13,14,15. In the positive Pacific Meridional Mode (PMM)16 phase, although which cannot be interpreted as an independent phenomenon from CP-type El Niño17, more TCs tend to occur over the western North Pacific18,19. Contributions from the Indian Ocean were also shown. TC activity over the western North Pacific could be suppressed by the tropical Indian Ocean warming20,21. The warm/cold eastern Indian Ocean could suppress/promote the TC genesis over the western North Pacific22. Also, the warm (cold) northern Indian Ocean could cause fewer (more) TCs forming north of 10°N and more (fewer) TCs forming south of 10°N over the western North Pacific in boreal summer23. In the summer following the spring subtropical Indian Ocean Dipole24, more TCs tend to form over the western North Pacific25. The TC activity could be remarkably enhanced near South China coastal areas during negative IOD autumns26. The extremely low TC activity during September–October 2018 may be attributed to a positive Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD)27. A combination of an El Niño Modoki and a positive IOD28, as in 1994, can enhance seasonal TC activity over the South China Sea29. A dipole SST anomaly in the Indo-Pacific warm pool can influence the total TC genesis number over the western North Pacific30.

Although the current status of the different models used to predict seasonal TC activity shows good levels of skill before the start of the climatological periods of peak typhoon activity2, there remains room for improvement. To the best of our knowledge, an exploration of how to reduce the large uncertainty of seasonal prediction of TC activity by a large-ensemble climate model has not yet been presented, thus it is the focus of this study. In this study, we have analyzed the reforecast outputs by the 108-ensemble-member SINTEX-F2 seasonal prediction system from the nine initialized dates (1st–9th) May and August of 1982–202231,32 to find predictable events, explore the origin of the success, and, hopefully, find potential room for improvement in the seasonal predictions by analyzing the co-variability of the inter-ensemble member anomalies. Although the spatial resolution of our system (T106) is relatively coarser than that of the other operational systems2, the 108-member system has an advantage in finding a predictable signal against unpredictable atmospheric noise on a seasonal timescale and possible co-variability patterns influencing predictions of TC frequency. Besides, the reforecast period in this study (1982–2022) is much longer than the 16-year period 2003–2018 in the previous work2.

Results

Skill assessment

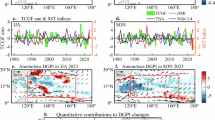

First, we checked the climatological fields of TC frequency in the prediction model. We tuned some parameters to detect TC in the model because its horizontal resolution (T106) was not enough to resolve TC realistically (see TC detection in Methods). We also used the Okubo–Weiss–Zeta (OWZ) scheme, which is an innovative direct TC detection and tracking scheme (see TC detection in Methods). The averaged TC frequency in June–August (JJA) was overestimated in the ensemble mean prediction relative to the JRA55 reanalysis data (Fig. 1a–c), although the model underestimated the TC frequency before the tuning. We also found that the positive bias in the OZW detection (Supplementary Fig. 1a–c and TC detection in Methods). To understand the cause of this bias, we have analyzed the Genesis Potential Index (GPI) defined by Emanuel and Nolan33. The GPI in JJA was also overestimated in the ensemble mean prediction relative to the JRA55 reanalysis data (Supplementary Fig. 2a–c). We estimated the relative contributions of the four components; the absolute vorticity at 850 hPa, the relative humidity at 700 hPa, the maximum potential intensity, and the vertical wind shear between 850 and 200 hPa, to the bias by recalculating the GPI in the model by replacing the model outputs one by one with the reanalysis data for the 4 components (Supplementary Fig. 2d–g). We found that the maximum potential intensity was critical. Murakami et al. 34 showed that maximum potential intensity is a major factor of GPI in the western North Pacific, and convective available potential energy (CAPE) plays a major role in the change of maximum potential intensity. Considering that CAPE is approximately controlled by sea surface temperature (SST), it is suggested that the positive TC frequency bias is due to SST to some extent. Since the model has the positive SST bias around Okinawa and Taiwan (Supplementary Fig. 3), it could cause the positive TC frequency bias there.

a Climatological tropical cyclone (TC) frequency in June–August (JJA) from the JRA55 reanalysis data (numbers in 5°×5° grid.). The target region (120°E–130°E and 20°N–30°N) is shown by a black box. (b) Same as (a), but for the prediction issued in early May by the SINTEX-F2 (108-ensemble mean). c (b) minus (a). (d, e, f) Same as (a, b, f), but for the standard deviation of year-to-year variations of TC frequency. g–l Same as (a–d), but for September–November (SON), with the prediction issued in early August.

The ensemble mean of standard deviations of year-to-year variations of TC frequency by an individual ensemble member was also larger than the standard deviation of the reanalysis data in some areas (Fig. 1e–g and Supplementary Fig. 1d–f for the OWZ detection), although the standard deviation of year-to-year variations of ensemble mean TC frequency in the ensemble mean was much smaller than the standard deviation of the reanalysis data (figure not shown). The standard deviation divided by the climatological TC frequency showed that the model slightly underestimated the TC variability relative to the mean (Supplementary Fig. 4a–c).

Next, we assessed the prediction skills for the JJA prediction issued in early May: the correlation skill of the ensemble-mean prediction, the signal-to-noise ratio (which indicates potential predictability, see the definition in Methods), and the Symmetric extremal dependence index35 (SEDI) (see the definition in Methods) skill for probabilistic prediction of the extreme positive tail with more than one standard deviation (approximately 16%). The probability threshold is 20%. Although the skills were limited (Fig. 2a–c), the correlation skill was statistically significant above the 95% significance level around Okinawa and Taiwan (Fig. 2a), which includes the Japanese Exclusive Economic Zone. Therefore, we would like to focus on that region (120°E–130°E and 20°N–30°N). The similar feature was also seen even if we used the OWZ detection (see Supplementary Fig. 5).

a Correlation skill for prediction of TC frequency anomalies in JJA issued in early May by the 1982–2022 reforecast experiments by the SINTEX-F2 system (108-ensemble mean). Areas where the values are statistically significant above the 95% significance level are shaded. The target region (120°E–130°E and 20°N–30°N) is shown by a red box. b Same as a, but for signal-to-noise ratio (standard deviation of ensemble mean divided by ensemble spread for 1982–2022). c Same as a, but for symmetric extremal dependence index (SEDI) skill for the extreme positive tail with more than one standard deviation (approximately 16%). The probability threshold is 20%. Areas where the values are statistically significant beyond the standard errors above the 95% significance level are dotted. d–f Same as (a-c), but for SON issued in early August.

There is not a large bias in the target region in the September–November (SON) mean TC frequency (Fig. 1g–i) and its variability (Fig. 1j–l). The SON prediction issued in early August was further challenging relative to JJA (Fig. 2d–f) and could not find the predictable area. The seasonality is consistent with Ogata et al.13, who used a 50-km atmospheric model, and Takaya et al.20,21, who used a dynamical seasonal prediction system (a 110-km atmospheric component).

As shown in the time series of TC frequency anomalies in JJA over the target area (Fig. 3), the TC active (quiescent) summers in 2018 and 1994 (1983 and 1998) were well predicted. As discussed above, there is a positive bias in the TC frequency (absolute values) and the variability (Supplementary Fig. 6).

Time series of TC frequency anomalies in JJA averaged over 120°E-130°E and 20°N-30°N; shown by a red box in Fig. 2a from the JRA55 reanalysis data (gray bar), the prediction issued on early May of each year by the SINTEX-F2 system (red cross: 108-ensemble mean; orange dot: each ensemble member). The unit of the y-axis is tropical cyclone frequency, i.e. counted TCs. We have highlighted the ensemble mean of 2018, 1994, 1983 and 1998 by blue boxes.

TC active summer in 2018

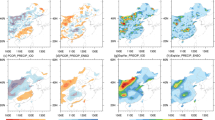

Eighteen TCs were observed over the western North Pacific in JJA 2018, which was ranked the second most active summer since 197927. Although the model could not capture the landfalling TC frequency anomalies around Japan in JJA 2018, it successfully predicted the positive anomalies in the target area (Fig. 4a, b). The model correctly predicted the evolution of a positive IOD, a CP El Niño, and a positive PMM at the time (Fig. 4d, e). The suppressed convection in the eastern tropical Indian Ocean (Fig. 4g) could excite the northward branch of the meridional circulation and then lead the low-level cyclonic flow over the target region (Fig. 4j) with the associated divergent flow from the eastern pole of the positive IOD into the south of the target region, the exit region of the monsoonal westerly jet around 10°–20°N (Fig. 4m). This pattern was similar to the Pacific-Japan (PJ) teleconnection pattern36, but the location was a little shifted westward37. The target region was also located in the exit region of the Trades and showed zonal asymmetries in the climatological mean field, which could enhance barotropic energy conversion from the mean flow to the PJ-associated anomalies in the lower troposphere38. The low-level cyclonic circulation could favor a TC frequency increase in the target region. Those patterns were mostly predicted by the ensemble mean prediction, although it showed some errors: the location of the negative OLR anomalies in the low-latitude northwestern Pacific was about 10° shifted southward (Fig. 4h), the low-level cyclonic flow over the target region further extended eastward (Fig. 4k), and the large-scale low-level convergence in the North Pacific was overestimated (Fig. 4n).

a TC frequency anomalies in JJA 2018 from the JRA55 reanalysis data in 5°×5° grid. (b) Same as (a), but for the prediction issued in early May 2018 by the SINTEX-F2 system (108-ensemble mean). c Inter-ensemble member correlation in the 108-member prediction between the TC frequency anomalies in the target area (120°E-130°E and 20°N-30°N) and the TC frequency anomalies for JJA of 2018 issued in early May 2018 by the SINTEX-F2. Values above 0.25, which are statistically significant above the 99% significance level, are shaded. d, e, f Same as (a, b, c), but for SST (°C). Dotted in e are area where the signal-to-noise ratio is above 1. (g, h, i) Same as (a, b, c), but for OLR (W m-2). (j, k, l) Same as (a, b, c), but for GH (m) and wind speed (m s-1) at 850 hPa. (m, n, o) Same as (a, b, c), but for velocity potential (10-6 m2 s-1) and divergent wind speed (m s-1) at 850 hPa. In all panels, the target area, the Dipole Mode Index (DMI, the SST anomaly difference between the western pole off East Africa (50°E–70°E, 10°S–10°N) and the eastern pole off Sumatra (90°E–110°E, 10°S–Equator), introduced by Saji et al.28, and the Niño3.4 (170°W–120°W, 5°S–5°N) regions are shown by black boxes, respectively.

The inter-ensemble correlation between the TC frequency anomalies in the target region and them in the other areas could indicate the TC frequency anomalies in the target region had no linear relationship with the TC frequency anomalies in the other regions (Fig. 4c). Interestingly, the prediction of the TC frequency anomalies in the target region was significantly linked with the prediction of the positive IOD, particularly the eastern pole (Fig. 4f): ensemble members that predicted stronger positive IOD tend to predict higher TC frequency in the target region. Although the differences among ensemble members due to large atmospheric internal variability have been considered to be unpredictable noise, the inter-ensemble correlation analyses could support that the teleconnection from the positive IOD commonly appears in ensemble members to some extent, as mentioned above for the observed/reanalysis data and the ensemble mean (Fig. 4i, l), although the inter-ensemble correlations with the associated velocity potential anomalies were not statistically significant (Fig. 4o). Our finding of the IOD contribution can add a new insight to the previous work by Qian et al.39, who showed that the 2018 TC active season in the North Pacific was primarily caused by warming in the subtropical Pacific (PMM) and secondarily by warming in the tropical Pacific (CP El Nino).

We also investigated the TC active (quiescent) summers in 1994 (1983 and 1998). The 1994 (1998) summer could suggest the positive (negative) IOD contribution, although the inter-ensemble correlations were too small to support it. The 1983 summer could suggest the negative PMM contribution. The details are shown in Supplementary Figs. 7-9a-o.

Statistical analysis

The correlation between the eastern pole of the DMI and the TC frequency anomalies around Okinawa and Taiwan for JJA of 1982–2022 was positive in the observational and reanalysis datasets, which was statistically significant above the 90% significance level (Fig. 5a). This is in agreement with a previous work22. The relationships were also well captured by the seasonal prediction system (Fig. 5b). The feature was also seen when we used the OWZ detection (Supplementary Fig. 10a, b). The correlations between the eastern pole of the DMI and the circulation anomalies also support the IOD teleconnection patterns discussed in the 2018 case study (Fig. 6): suppressed convection in the eastern tropical Indian Ocean enhanced divergent wind from the eastern tropical Indian Ocean to the Okinawa and Taiwan areas. That helped to generate low pressure in the target area, which was favorable for the TC frequency. This is also consistent with the previous study40, which showed that the positive IOD composite analysis also exhibits a low-level cyclonic circulation anomaly in the target region, although it is not statistically significant.

a Correlation map between the eastern pole of DMI from the observation and the TC frequency anomalies in JJA of 1982–2022 from the JRA55 reanalysis data in 5°×5° grid. b Same as (a), but for the prediction issued in early May by the SINTEX-F2 system (108-ensemble mean). In all panels, the target area is shown by a black box. Values above 0.25, which are statistically significant above the 90% significance level, are shaded.

a Correlation map between the eastern pole of the DMI and the SST anomalies in JJA of 1982–2022 from the observational data. b Same as (a), but for the prediction issued in early May by the SINTEX-F2 system (108-ensemble mean). c, d Same as (a, b), but for OLR. (e, f) Same as (a, b), but for GH and wind speed at 850 hPa. g, h Same as (a, b), but for velocity potential and divergent wind speed at 850 hPa. Values above 0.25, which are statistically significant above the 90% significance level, are shaded. In all panels, the target area, the DMI, and the Niño3.4 regions are shown by black boxes, respectively.

Discussions

We found that a positive IOD played a key role in the seasonal predictability of the 2018 summer TC frequency around Okinawa and Taiwan by the dynamical prediction system. The 108-member system had an advantage in finding the predictable signal against the large unpredictable noise and the possible IOD teleconnection via the inter-member co-variability analyses. By reducing the uncertainty of the IOD prediction, we could reduce the uncertainty of the TC frequency prediction around Okinawa and Taiwan and increase the signal. The IOD contributions to the predictability were also seen in the correlation analyses in 1982–2022 and some case studies in 1994 and 1998.

Interestingly, the signals, the ensemble-mean predictions, were relatively strong for the four well-predicted summers in 1983, 1994, 1998, and 2018. When the signal is relatively strong for the coming TC season, we could add information that the prediction is relatively reliable41 although the sample size was limited to discuss the statistical skill scores. For the four summers, the IOD and/or PMM could provide a window of opportunity to issue a much more confident forecast than average skill estimates would suggest. Further careful assessments of extreme climate events and their drivers are necessary to utilize windows of opportunity for stakeholders to issue a range of plausible predictions, trustworthy and actionable early warnings with real-time forecasts42.

The PJ pattern was clear for the summer of 1994 and 1983 (Supplementary Figs. 7 and 8), so we have calculated inter-ensemble member correlation in the 108-member prediction between the sea level pressure at Hengchun of Taiwan and the OLR anomalies (Supplementary Fig. 11a, c). The sea level pressure at Hengchun of Taiwan was used to the PJ index43. Supplementary Fig. 6a and c suggested the PJ pattern in 1994 and 1983. However, we could not find the co-variability between the PJ pattern and the tropical climate variations such as ENSO and IOD (Supplementary Fig. 11b, d). For the summer of 1983, we could find the co-variability between the PJ pattern and the local SST over the western North Pacific (Supplementary Fig. 11d). This is partly consistent with the previous study44, which showed that the PJ pattern can self-aggregate over the Taiwan region, which could be less related to IOD or ENSO. Note that the correlation between the sea level pressure at Hengchun of Taiwan and the SST anomalies for JJA of 1982–2022 in the observations suggested that the weak contribution of the eastern pole of IOD to the PJ pattern (Supplementary Fig. 11e), although the correlation with the OLD anomalies did not suggest it (Supplementary Fig. 11g). The ensemble mean predictions overestimated the statistical relationship with ENSO and IOD (Supplementary Fig. 11f, h), which may be due to the fact that the ensemble mean did not include the noise. Further studies are needed to investigate possible contributions of the self-sustained PJ pattern to the seasonal predictability of the TC frequency anomalies over the western North Pacific.

The presented results are based only on a single system. In the next step, the robustness should be investigated further by including the results of multi-model systems. Particularly, further studies with high-resolution models45,46,47,48 are necessary because the horizontal resolution of the SINTEX-F (T106) was not enough to realistically resolve TC. Such research streams are underway49,50,51.

There could be differences between the detected TC from the reanalysis data and the observed TC. We have calculated the correlation between the detected TC frequency anomalies and the Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA) Best Track Data for JJA and SON of 1982–2022 (Supplementary Fig. 12). Since the correlations were statistically significant above the 95% significance level in the target area (Supplementary Fig. 12a, c), we did the comparison with the detected tropical cyclones from the JRA55 reanalysis data. Note that the correlations in JJA are slightly higher in the target area relatively to the OWZ detection (Supplementary Fig. 12a, b), while the correlations in SON by the OWZ detection are slightly higher in the target area (Supplementary Fig. 12c, d). Although the results might be sensitive to the TC detection methods, the robustness of the IOD contribution to the predictability of the summer TC frequency around Okinawa and Taiwan could be ensured to some extent. Further fine-tuning of the TC detection method might be helpful to improve the prediction skill of the SINTEX-F. However, manually tuning is typically a time-consuming. Machine learning techniques may help addressing it. We would like to challenge it as a future research topic.

The 5°grid interpolation in this study might be weak for constructing relationship between TC frequency and tropical climate modes. Some previous studies52,53 induced some new interpolation methods, which could enhance the stability of the statistical analysis. We would like to study the sensitivity of the interpolation methods as a future research topic.

Methods

Reforecast experiments

The SINTEX-F2 seasonal prediction system is based on a global ocean-atmosphere-land-sea ice coupled model54,55 with a surface and subsurface oceanic initialization scheme56,57 developed under the EU-Japan collaborative framework. This system adopts a relatively simple initialization scheme based only on the nudging of the SST data56 and a three-dimensional variational ocean data assimilation (3DVAR) method by taking three-dimensional observed ocean temperature and salinity data into account57. The atmospheric component of the SINTEX-F2 has a horizontal resolution of 1.125° (T106) with 31 vertical levels, while the oceanic component has a horizontal resolution of about 0.5° × 0.5° with 31 vertical levels. To determine the anomalies, we have removed the model monthly climatology for the period 1991–2020 at each lead time.

Observational and reanalysis datasets

To evaluate the prediction results, we used the JRA55 reanalysis data58,59 for TC detection, the NOAA OISSTv2 high-resolution version60 for SST, the NOAA Interpolated Outgoing Longwave Radiation (OLR)61 for OLR, and the NCEP/NCAR reanalysis data62 for other atmospheric fields. The monthly anomalies were derived through deviations from the monthly climatology calculated by averaging the monthly data from 1991 to 2020.

TC detection

We used TempestExtremes63,64,65 to detect TC from the six hourly reanalysis data: 1) search for candidates as minima in the sea level pressure field; 2) eliminate if a more intense minimum exists within a great-circle-distance of 10.0°; 3) enforce a closed contour, requiring an increase at least 50 Pa within 5° of the candidate node, and a decrease in 300 hPa air temperature of 0.1 K within 5° of the node within 1.0° of the candidate with maximum air temperature; 4) candidates are then stitched in time to form paths, 4a) with a maximum distance between candidates of 6.0° (great-circle-distance), 4b) consisting of at least 8 candidates per path (48 hours), 4c) with a maximum gap size of 2 (12 hours, most consecutive timesteps with no associated candidate), and 4 d) with a minimum distance between endpoints of 20 degrees. Once the complete set of TC paths has been computed, total TC is counted over each 5° grid cell in JJA and SON for each year. We tuned some parameters to detect TC in the model because the horizontal resolution ( ~ T106) was not enough to resolve it realistically (too weak and too short lifespan) in the procedures 3) and 4 d) as follows: 3) enforce a closed contour requiring an increase of 50 Pa within 10 degrees of the candidate and a decrease of 0.1 K within 10° of the node within 2.0° of the candidate with maximum air temperature; in 4 d) with a minimum distance between endpoints of 10 degrees. To ensure the robustness of the results, we also used the OWZ detection66 by adapting DetectNodes code and StitchNodes code67 into TempestExtremes63,64,65. The OWZ scheme is an innovative direct TC detection and tracking scheme that utilizes only tropospheric variables. It is based on evaluating the OWZ, defined as

where f is the Coriolis parameter, η is the absolute vorticity, ζ is relative vorticity, E =∂u/∂x + ∂υ/∂y is the stretching deformation, and F = ∂υ/∂x + ∂u/∂y is the shearing deformation. We first identified local maxima of OWZ at 850hPa. Candidates for which a stronger OWZ maximum exists within 5° great-circle-distance are eliminated. Next, only those candidates that satisfy the following six conditions within a distance of 2° great-circle-distance of that maximum are retained (OWZ at 850 hPa ≥ 5 ×10−5 s−1; OWZ at 500 hPa ≥ 4 ×10−5 s−1; relative humidity at 950 hPa ≥ 70%; relative humidity at 700 hPa ≥ 50%; specific humidity at 950 hPa ≥ 10 g kg−1; vws (vertical wind shear between 200 and 850 hPa) ≤ 25 m s−1). Consecutive TC points are stitched together when they lie within a maximum distance of 5° great-circle-distance from one another, allowing for a maximum 24-hour gap. Additional core thresholds must be reached for at least 48 hours (OWZ at 850 hPa ≥ 6 ×10−5 s−1; OWZ at 500 hPa ≥ 5 ×10−5 s−1; relative humidity at 950 hPa ≥ 85%; relative humidity at 700 hPa ≥ 70%; specific humidity at 950 hPa ≥ 14 g kg−1; vws ≤ 12.5 m s−1). Finally, tracks that do not reach tropical storm intensity (10-m zonal wind speed = 16 m s−1) for at least one time step are filtered out (see the details in Bourdin et al.67).

Inter-ensemble correlation analysis

The inter-ensemble correlation (i.e., correlation in the ensemble phase space) can measure how two predictions co-vary over the ensemble phase space and indicate the linear relationship as a number between -1 and 1. It provides useful insights into possible precursors and teleconnection patterns related to a climate event32,68,69,70,71,72. Here, we calculate inter-ensemble correlation coefficients between the target anomalies and horizontal maps of anomalous fields for each grid point among the 108 ensemble members with the SINTEX-F2 system for the target season as

Here \({ne}\) is the ensemble size: 108, \(X(e)\) is predictions of the target index as a function of ensemble member (\(e\)), \(\mathop{X}\limits^{\bar{} }\) is the ensemble mean of \(X\left(e\right)\), \(Y(x,y,e)\) is predictions of the other variables and a function of two-dimensional horizontal (\(x,y\)), and ensemble member (\(e\)), \(\mathop{Y(x,y)}\limits^{\bar{} }\) is the ensemble mean of \(Y(x,y,e)\), respectively. In this analysis, the large ensemble size has an advantage in finding significant co-variability patterns when the signal-to-noise ratio of the target is generally low73.

Signal-to-noise ratio

We assessed the potential predictability by dividing the predicted variability into signal (S) and unpredictable noise (N) components. Here, S is estimated as the ensemble mean of the 108 members. N is estimated as the ensemble spread, which provides a measure of the uncertainties among the predictions. By calculating the signal-to-noise (SN) ratio, we measured robustness of the prediction of the signal as well as the potential predictability in a given month32.

Symmetric extremal dependence index

Symmetric extremal dependence index35 (SEDI) is a skill score suitable for extreme events. It provides meaningful results for rare events where the hit rate and false alarm rate approach zero. It is defined for a binary event and therefore requires a threshold to be set. In this study, the extreme positive tail was set by one standard deviation and the probability threshold is 20%.

Data availability

The detected TC frequency data and the GPI analysis data were available from https://zenodo.org/records/14676083. The NOAA OISSTv2, the NOAA OLR, and the NCEP/NCAR reanalysis were provided by the NOAA/OAR/ESRL PSD, Boulder, Colorado, USA, from their web sites at https://psl.noaa.gov/data/gridded/data.noaa.oisst.v2.highres.html, https://psl.noaa.gov/data/gridded/data.olrcdr.interp.html, and, respectively. The JRA55 reanalysis datasets were available from https://jra.kishou.go.jp/JRA-55/index_en.html. The Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA) Best Track Data were available from https://www.jma.go.jp/jma/jma-eng/jma-center/rsmc-hp-pub-eg/besttrack.html. The SINTEX-F2 reforecast outputs were available from https://www.jamstec.go.jp/sintex-f/catalog/catalog.html and the corresponding author upon request.

References

Saunders, M. A., Chandler, R. E., Merchant, C. J. & Roberts, F. P. Atlantic hurricanes and NW Pacific typhoons: ENSO spatial impacts on occurrence and landfall. Geophys Res Lett. 27, 1147–1150 (2000).

Klotzbach, P. et al. Seasonal Tropical Cyclone Forecasting. Trop. Cyclone Res. Rev. 8, 134–149 (2019).

Mei, W., Xie, S.-P., Primeau, F., McWilliams, J. C. & Pasquero, C. Northwestern Pacific typhoon intensity controlled by changes in ocean temperatures. Sci. Adv. 1, 1500014 (2015).

Wang, B. & Chan, J. C. L. How Strong ENSO Events Affect Tropical Storm Activity over the Western North Pacific. J. Clim. 15, 1643–1658 (2002).

Chen, T.-C., Weng, S.-P., Yamazaki, N. & Kiehne, S. Interannual Variation in the Tropical Cyclone Formation over the Western North Pacific. Mon. Weather Rev. 126, 1080–1090 (1998).

Takahashi, H. G., Fujinami, H., Yasunari, T., Matsumoto, J. & Baimoung, S. Role of Tropical Cyclones along the Monsoon Trough in the 2011 Thai Flood and Interannual Variability. J. Clim. 28, 1465–1476 (2015).

Camargo, S. J. & Sobel, A. H. Western North Pacific Tropical Cyclone Intensity and ENSO. J. Clim. 18, 2996–3006 (2005).

Gao, C., Zhou, L., Wang, C., Lin, I.-I. & Murtugudde, R. Unexpected limitation of tropical cyclone genesis by subsurface tropical central-north Pacific during El Niño. Nat. Commun. 13, 7746 (2022).

Capotondi, A. et al. Understanding ENSO diversity. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 96, 921–938 (2015).

Kim, H.-M., Webster, P. J. & Curry, J. A. Modulation of North Pacific Tropical Cyclone Activity by Three Phases of ENSO. J. Clim. 24, 1839–1849 (2011).

Ashok, K., Behera, S. K., Rao, S. A., Weng, H. & Yamagata, T. El Niño Modoki and its possible teleconnection. J. Geophys Res Oceans 112, 1–27 (2007).

Yeh, S.-W. et al. El Niño in a changing climate. Nature 462, 674–674 (2009).

Ogata, T., Taguchi, B., Yamamoto, A. & Nonaka, M. Potential Predictability of the Tropical Cyclone Frequency Over the Western North Pacific With 50-km AGCM Ensemble Experiments. J. Geophys. Res.: Atmosph. 126, 034206 (2021).

Patricola, C. M., Camargo, S. J., Klotzbach, P. J., Saravanan, R. & Chang, P. The Influence of ENSO Flavors on Western North Pacific Tropical Cyclone Activity. J. Clim. 31, 5395–5416 (2018).

Hong, C.-C., Li, Y.-H., Li, T. & Lee, M.-Y. Impacts of central Pacific and eastern Pacific El Niños on tropical cyclone tracks over the western North Pacific. Geophys Res Lett. 38, 048821 (2011).

Chiang, J. C. H. & Vimont, D. J. Analogous Pacific and Atlantic Meridional Modes of Tropical Atmosphere–Ocean Variability. J. Clim. 17, 4143–4158 (2004).

Chang, P. et al. Pacific meridional mode and El Niño—Southern Oscillation. Geophys Res Lett. 34, 030302 (2007).

Zhang, W., Vecchi, G. A., Murakami, H., Villarini, G. & Jia, L. The Pacific Meridional Mode and the Occurrence of Tropical Cyclones in the Western North Pacific. J. Clim. 29, 381–398 (2016).

Murakami, H. et al. Dominant Role of Subtropical Pacific Warming in Extreme Eastern Pacific Hurricane Seasons: 2015 and the Future. J. Clim. 30, 243–264 (2017).

Du, Y., Yang, L. & Xie, S.-P. Tropical Indian Ocean Influence on Northwest Pacific Tropical Cyclones in Summer following Strong El Niño. J. Clim. 24, 315–322 (2011).

Takaya, Y., Kubo, Y., Maeda, S. & Hirahara, S. Prediction and attribution of quiescent tropical cyclone activity in the early summer of 2016: case study of lingering effects by preceding strong El Niño events. Atmos. Sci. Lett. 18, 330–335 (2017).

Zhan, R., Wang, Y. & Lei, X. Contributions of ENSO and East Indian Ocean SSTA to the Interannual Variability of Northwest Pacific Tropical Cyclone Frequency. J. Clim. 24, 509–521 (2011).

Jiayu, Z., Wu, Q., Guo, Y. & Zhao, S. The Impact of Summertime North Indian Ocean SST on Tropical Cyclone Genesis over the Western North Pacific. SOLA 12, 242–246 (2016).

Behera, S. K. & Yamagata, T. Subtropical SST dipole events in the southern Indian Ocean. Geophys Res Lett. 28, 327–330 (2001).

Zhou, Q. & Zhang, R. Possible impacts of spring subtropical Indian Ocean Dipole on the summer tropical cyclone genesis frequency over the western North Pacific. Int. J. Climatol. 42, 5393–5402 (2022).

Zhou, Q., Wei, L. & Zhang, R. Influence of Indian Ocean Dipole on Tropical Cyclone Activity over Western North Pacific in Boreal Autumn. J. Ocean Univ. China 18, 795–802 (2019).

Gao, S., Zhu, L., Zhang, W. & Shen, X. Western North Pacific Tropical Cyclone Activity in 2018: A Season of Extremes. Sci. Rep. 10, 5610 (2020).

Saji, N. H., Goswami, B. N., Vinayachandran, P. N. & Yamagata, T. A dipole mode in the tropical Indian Ocean. Nature 401, 360–363 (1999).

Pradhan, P. K., Preethi, B., Ashok, K., Krishnan, R. & Sahai, A. K. Modoki, Indian Ocean Dipole, and western North Pacific typhoons: Possible implications for extreme events. J. Geophys. Res. Atmosph. 116, 1–12 (2011).

Wang, C. & Wang, B. Tropical cyclone predictability shaped by western Pacific subtropical high: integration of trans-basin sea surface temperature effects. Clim. Dyn. 53, 2697–2714 (2019).

Doi, T., Behera, S. K. & Yamagata, T. Merits of a 108-member ensemble system in ENSO and IOD predictions. J. Clim. 32, 957–972 (2019).

Doi, T., Behera, S. K. & Yamagata, T. Wintertime Impacts of the 2019 Super IOD on East Asia. Geophys Res Lett. 47, 089456 (2020).

Emanuel, K. A. & Nolan, D. N. 2004. Tropical cyclone activity and global climate https://ams.confex.com/ams/26HURR/techprogram/paper_75463.htm (2004).

Murakami, H., Wang, B. & Kitoh, A. Future Change of Western North Pacific Typhoons: Projections by a 20-km-Mesh Global Atmospheric Model. J. Clim. 24, 1154–1169 (2011).

Ferro, C. A. T. & Stephenson, D. B. Extremal Dependence Indices: Improved Verification Measures for Deterministic Forecasts of Rare Binary Events. Weather Forecast 26, 699–713 (2011).

Nitta, T. Convective Activities in the Tropical Western Pacific and Their Impact on the Northern Hemisphere Summer Circulation. J. Meteorol. Soc. Jpn. Ser. II 65, 373–390 (1987).

Guan, Z. & Yamagata The unusual summer of 1994 in East Asia: IOD teleconnections. Geophys Res Lett. 30, 016831 (2003).

Kosaka, Y. & Nakamura, H. Structure and dynamics of the summertime Pacific–Japan teleconnection pattern. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 132, 2009–2030 (2006).

Qian, Y. et al. On the Mechanisms of the Active 2018 Tropical Cyclone Season in the North Pacific. Geophys Res Lett. 46, 12293–12302 (2019).

Takemura, K. & Shimpo, A. Influence of Positive IOD Events on the Northeastward Extension of the Tibetan High and East Asian Climate Condition in Boreal Summer to Early Autumn. SOLA 15, 75–79 (2019).

Doi, T., Nonaka, M. & Behera, S. Can signal-to-noise ratio indicate prediction skill? Based on skill assessment of 1-month lead prediction of monthly temperature anomaly over Japan. Front. Clim. 4, 887782 (2022).

Dunstone, N. et al. Windows of opportunity for predicting seasonal climate extremes highlighted by the Pakistan floods of 2022. Nat. Commun. 14, 6544 (2023).

Kubota, H., Kosaka, Y. & Xie, S. A 117-year long index of the Pacific-Japan pattern with application to interdecadal variability. Int. J. Climatol. 36, 1575–1589 (2016).

Zhao, J. et al. Atmospheric modes fiddling the simulated ENSO impact on tropical cyclone genesis over the Northwest Pacific. NPJ Clim. Atmos. Sci. 6, 213 (2023).

Yamada, Y. et al. High-Resolution Ensemble Simulations of Intense Tropical Cyclones and Their Internal Variability During the El Niños of 1997 and 2015. Geophys Res Lett. 46, 7592–7601 (2019).

Roberts, M. J. et al. Tropical Cyclones in the UPSCALE Ensemble of High-Resolution Global Climate Models. J. Clim. 28, 574–596 (2015).

Yoshida, K., Sugi, M., Mizuta, R., Murakami, H. & Ishii, M. Future Changes in Tropical Cyclone Activity in High-Resolution Large-Ensemble Simulations. Geophys Res Lett. 44, 9910–9917 (2017).

Murakami, H. et al. Simulation and Prediction of Category 4 and 5 Hurricanes in the High-Resolution GFDL HiFLOR Coupled Climate Model. J. Clim. 28, 9058–9079 (2015).

Baba, Y. & Ogata, T. Resolution dependence of tropical cyclones simulated by a spectral cumulus parameterization. Dyn. Atmosph. Oceans 97, 101283 (2022).

Ogata, T., Komori, N., Doi, T., Yamamoto, A. & Nonaka, M. Seasonal prediction system using CFES and comparison with SINTEX-F2. SOLA 20, 92–101 (2024).

Masunaga, R., Miyakawa, T., Kawasaki, T. & Yashiro, H. Flux Adjustment on Seasonal-Scale Sea Surface Temperature Drift in NICOCO. J. Meteorol. Soc. Jpn. Ser. II 101, 175–189 (2023).

Song, K., Zhao, J., Zhan, R., Tao, L. & Chen, L. Confidence and Uncertainty in Simulating Tropical Cyclone Long-Term Variability Using the CMIP6-HighResMIP. J. Clim. 35, 6431–6451 (2022).

Zhao, J., Zhan, R., Wang, Y., Jiang, L. & Huang, X. A Multiscale-Model-Based Near-Term Prediction of Tropical Cyclone Genesis Frequency in the Northern Hemisphere. J. Geophys. Res.: Atmosph. 127, 037267 (2022).

Masson, S. et al. Impact of intra-daily SST variability on ENSO characteristics in a coupled model. Clim. Dyn. 39, 681–707 (2012).

Sasaki, W., Richards, K. J. & Luo, J. J. Impact of vertical mixing induced by small vertical scale structures above and within the equatorial thermocline on the tropical Pacific in a CGCM. Clim. Dyn. 41, 443–453 (2013).

Doi, T., Behera, S. K. & Yamagata, T. Improved seasonal prediction using the SINTEX-F2 coupled model. J. Adv. Model Earth Syst. 8, 1847–1867 (2016).

Doi, T., Storto, A., Behera, S. K., Navarra, A. & Yamagata, T. Improved prediction of the Indian Ocean Dipole Mode by use of subsurface ocean observations. J. Clim. 30, 7953–7970 (2017).

Harada, Y. et al. The JRA-55 Reanalysis: Representation of Atmospheric Circulation and Climate Variability. J. Meteorol. Soc. Jpn. Ser. II 94, 269–302 (2016).

Kobayashi, S. et al. The JRA-55 Reanalysis: General Specifications and Basic Characteristics. J. Meteorol. Soc. Jpn. Ser. II 93, 5–48 (2015).

Huang, B. et al. Improvements of the Daily Optimum Interpolation Sea Surface Temperature (DOISST) Version 2.1. J. Clim. 34, 2923–2939 (2021).

Liebmann, B. & Smith, C. A. Description of a Complete (Interpolated) Outgoing Longwave Radiation Dataset. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 77, 1275–1277 (1996).

Kalnay, E. et al. The NCEP/NCAR 40-year reanalysis project. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 77, 437–471 (1996).

Zarzycki, C. M. & Ullrich, P. A. Assessing sensitivities in algorithmic detection of tropical cyclones in climate data. Geophys Res Lett. 44, 1141–1149 (2017).

Ullrich, P. A. & Zarzycki, C. M. TempestExtremes: a framework for scale-insensitive pointwise feature tracking on unstructured grids. Geosci. Model Dev. 10, 1069–1090 (2017).

Ullrich, P. A. et al. TempestExtremes v2.1: a community framework for feature detection, tracking, and analysis in large datasets. Geosci. Model Dev. 14, 5023–5048 (2021).

Chand, S. S. et al. Declining tropical cyclone frequency under global warming. Nat. Clim. Chang 12, 655–661 (2022).

Bourdin, S., Fromang, S., Dulac, W., Cattiaux, J. & Chauvin, F. Intercomparison of four algorithms for detecting tropical cyclones using ERA5. Geosci. Model Dev. 15, 6759–6786 (2022).

Ma, J., Xie, S. P. & Xu, H. Contributions of the North Pacific meridional mode to ensemble spread of ENSO prediction. J. Clim. 30, 9167–9181 (2017).

Ogata, T., Doi, T., Morioka, Y. & Behera, S. Mid-latitude source of the ENSO-spread in SINTEX-F ensemble predictions. Clim. Dyn. 52, 2613–2630 (2019).

Doi, T., Behera, S. K. & Yamagata, T. Predictability of the Super IOD Event in 2019 and Its Link With El Niño Modoki. Geophys Res Lett. 47, 086713 (2020).

Doi, T., Nonaka, M. & Behera, S. Skill Assessment of Seasonal-to-Interannual Prediction of Sea Level Anomaly in the North Pacific Based on the SINTEX-F Climate Model. Front Mar. Sci. 7, 546587 (2020).

Doi, T., Behera, S. K. & Yamagata, T. Seasonal predictability of the extreme Pakistani rainfall of 2022 possible contributions from the northern coastal Arabian Sea temperature. NPJ Clim. Atmos. Sci. 7, 13 (2024).

Doi, T., Behera, S. K. & Yamagata, T. On the Predictability of the Extreme Drought in East Africa During the Short Rains Season. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, 100905 (2022).

Acknowledgements

The SINTEX-F2 seasonal climate prediction system was run using the Earth Simulator at JAMSTEC (see http://www.jamstec.go.jp/es/en/index.html for the system overview). We are sincerely grateful to Drs. Wataru Sasaki, Jing-Jia Luo, Sebastian Masson, Andrea Storto, Antonio Navarra, Silvio Gualdi, and our European colleagues of INGV/CMCC, L’OCEAN, and MPI for their contributions in developing the prototype prediction system. We also thank Dr. Akira Yamazaki for his helps to use the JRA55 reanalysis data and Drs. Tomoe Nasuno, Masuo Nakano, and Yohei Yamada for their constructive suggestions. The GrADS software was used for creating the figures and the maps. The GPI analysis code is available from https://github.com/wy2136/TCI. This research was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grants 20K04074 and the Tokio Marine Research Institute.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors designed the study. T.D. and T.I. performed the analysis, and T.D. wrote the manuscript with input from the co-authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

All authors declare no completing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Doi, T., Inoue, T., Ogata, T. et al. Seasonal predictability of tropical cyclone frequency over the western North Pacific by a large-ensemble climate model. npj Clim Atmos Sci 8, 112 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-00995-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-00995-0

This article is cited by

-

Seasonal predictability of an indicator of mass coral bleaching between the Pacific ocean and the East China sea with a large ensemble climate model

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Climatological characteristics of tropical cyclones simulated in the global-regional integrated forecasting system (GRIST) model

Climate Dynamics (2025)