Abstract

Warmer sea surface temperatures (SSTs) increase evaporation, convection, and latent heat release in the atmosphere, which favors tropical cyclone (TC) intensification and ultimately leads to stronger storms. However, in this study, we find that the intensity of TCs in the western North Pacific, called typhoons, is on average higher in the colder autumn season than during the warmer summer season. The primary reason for this is that despite the decrease in SSTs during autumn, the deepening of the ocean mixed layer increase the TC heat potential and reduces storm-induced SST cooling. Atmospheric thermodynamic conditions also become more favorable to TC intensification in autumn than in summer due to higher heat and sensible heat fluxes in autumn resulting from the increased air-sea temperature/moist differences at the interface. Lastly, during autumn, the TC’s track shifts towards the equator as a result the TCs in this season travel over more favourable ocean condition which also contribute in the TC intensification. This finding will enhance the understanding of the mechanisms causing seasonal differences in TC intensity, which will aid in TC seasonal forecasting and risk assessment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Globally, tropical cyclones (TCs) rank among the most devastating natural hazards. They are associated with extreme winds, very heavy rainfall and massive storm surge leading to significant economic losses and casualties1,2. Among the tropical ocean basins, the western North Pacific (WNP) basin experiences the highest annual TC frequency3, and within this basin, the most intense TCs are found. Super Typhoon Haiyan, with a wind speed of 170 knots is one of the strongest TCs in the history of the WNP basin4. Understanding the intensity of a TC remains a major challenge for both the research and forecasting communities5,6.

TC intensity is influenced by a complex interaction between external factors, which are controlled by large-scale ocean-atmospheric background conditions, and internal processes of the TC itself6. The main external factors affecting the intensity of TC are the interaction of the TC with the underlying surface and sub-surface ocean conditions, vertical wind shear, trough interactions and the impact of dry air in the mid to upper levels of the atmospheric column. One critical factor that enhances TC intensification is high sea surface temperature (SST), which provides a substantial amount of moisture through heat fluxes7. Several case studies have highlighted the significance of these heat fluxes, encompassing latent and sensible heat flux, in driving TC intensification8,9,10. In addition to high SST, warm sub-surface ocean temperature and high ocean heat content also play crucial roles in intensifying TCs11,12,13. The presence of warm sub-surface ocean conditions reduces the TC-induced SST cooling, thus minimizing the negative feedback to the system and supplying more energy to the TC, thereby favoring its intensification13,14,15,16,17,18.

Among the atmospheric dynamic conditions, vertical wind shear plays a significant role in determining the intensity of TCs. Low to moderate wind shear generally favours more intense TCs19,20. Additionally, the atmospheric thermodynamic conditions also influence the intensity of a TC. Factors such as the amount of moisture present in the lower to upper atmosphere and the presence of dry air entrainment in the core of the system play key roles. Along with it, convective available potential energy (CAPE), a measure of the atmospheric instability, also affects the TC intensity21. Greater CAPE leads to more active convective processes, releasing more latent heat to fuel the system, and promoting TC intensification. Furthermore, the interactions between TCs and atmospheric troughs can modulate the upper level divergence which plays a significant role in modulating the TC intensity22,23.

In the WNP, there exists a pronounced seasonal variation in the frequency and tracks of TCs. During summer, cyclogenesis occurs more northward compared to autumn24,25 and the tracks of TCs tend to be more poleward26. This seasonal migration of TC track indicates that the environmental conditions, including ocean and atmospheric conditions encountered by TCs during their lifetime, vary from one season to another. These seasonal differences may also influence the maximum potential intensity (MPI) of TCs27,28. It is observed that there is a positive correlation between the interannual variation in the lifetime maximum intensity (LMI) of TCs and the MPI in the WNP29. Along the TC tracks, the MPI exhibit a marked seasonal variability30,31. However, the seasonal variations in the MPI in this basin is less as compared to other basins31. These seasonal variation in MPI is primarily attributed to the seasonal changes in the outflow temperature near the tropopause31.

As mentioned earlier, the WNP experiences significant seasonal variations in TC genesis and tracks. Moreover, various ocean-atmosphere parameters, including ocean surface and sub-surface temperatures, mixed layer depth, relative vorticity and wind shear, exhibit marked seasonal variations32,33,34,35,36. Recent study shows that that the intensification of TCs in this basin is primarily influenced by dynamic factors rather than thermodynamic factors37. However, there is currently a lack of in-depth analysis on how these seasonal differences in the background conditions may modulate the intensity of TCs in different seasons. In this study we investigate the seasonal differences in the intensity of TCs in the WNP and explore the mechanisms that drive these differences, with particular emphasis on the summer and autumn seasons.

Results

Seasonal variations of TC characteristics in the WNP

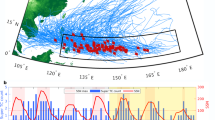

During the period 2005–2020, 140 TCs formed in the summer season, and 152 TCs formed in the autumn season, indicating that there is no significant difference in the frequency of TCs between these two seasons. Out of the total number of TCs in the two seasons, 75.7% and 80.9% of TCs in the summer and autumn seasons, respectively, formed in the MDR. Despite the similarity in TC frequency between the two seasons, a closer examination of TC track density reveals noteworthy seasonal variations in their tracks (Fig. 1). TC track density considers the combined influence of TC genesis locations and the subsequent track taken by TCs after genesis38,39. During summer, 72.9% of the total TC track points are situated within the MDR and the TCs generally exhibit a more poleward trajectory (Fig. 1). In contrast, during autumn, 78.9% of the total TC track points are within the MDR, but the TCs demonstrate a decrease in the poleward track (Fig. 1). On average, the latitude of the TC track (from genesis till LMI) in summer is 20.7°N, while during autumn, it is 18.2°N (Table 1). Also, the latitude where TC attains its LMI is 2.5° poleward in summer than in autumn. This shows that in autumn, TC travels in a more equatorward direction than in summer.

Similar to the contrasting tracks of TCs observed in the two seasons, there exists a notable dissimilarity in the intensity of TCs within the basin. We analyzed the average maximum wind speeds of TCs (averaged from the genesis of TC till LMI). Our findings indicate a substantial variance in TC intensity between the summer and autumn seasons. Specifically, the average intensity during autumn is significantly higher, with an average of 32.4 m s−1, compared to the summer, with an average of 27.9 m s−1, reflecting a notable 14.9% disparity (Table 1). Similarly, the average LMI of TCs during the autumn season is 49.4 m s−1 which is ~9 m s−1 higher than in the summer season (Table 1). These differences in the intensity of TC between the two seasons are statistically significant (p < 0.01). In line with the intensity analysis based on the wind speed of TC, we also found that at the LMI, the TCs in the autumn on average, have ~13 hPa lower minimum mean sea level pressure (MSLP) than the TCs in summer. Similarly, the TC center pressure averaged from the genesis till LMI is 5 hPa lower in autumn than in summer (Table 1). This is in agreement with Tu et al. (2011) which shows that the maximum number of intense TCs occur in September and October. In autumn, a greater proportion of TCs intensify to at least a category 1 TC, with wind speeds of 65 knots or more, compared to the summer season. The rate of intensification from a tropical storm to at least a category 1 TC is 57.9% and 73.0% during the summer and autumn seasons, respectively.

As mentioned earlier, TCs travel more equatorward in autumn than in summer. Changes in TC tracks can impact the basin-wide mean intensity of TCs due to the non-uniform spatial distribution of environmental parameters27,40. These variations in tracks can lead to TCs encountering distinct environmental conditions, such as a poleward decrease in ocean heat content and atmospheric humidity. In order to remove the influence of the role of the TC track on TC intensity, we have estimated the TC mean wind speed only in the MDR region (Table 2). In line with the findings mentioned above, we find that in the MDR region, the average maximum windspeed of TC in summer is 32.4 m s−1 and in autumn is 36.6 m s−1 and the difference between the two seasons is statistically significant (p < 0.01). Therefore, we conclude that, on average, TCs during autumn are more intense than summer.

Background oceanic conditions

As previously discussed, TCs are sustained by warm ocean temperatures and the exchange of heat flux between the ocean and the atmosphere. In the WNP, SST exhibits distinct seasonal fluctuations (Fig. 2a), with the peak SST occurring in August and September and the lowest SST observed in February41. During the summer and autumn seasons, the mean SST within the MDR is 29.2 °C and 28.8 °C, respectively, with a statistically significant difference between the two seasons (p < 0.01) (Table 2). Notably, the highest SST is observed near the equator in both seasons, gradually decreasing toward higher latitudes (Fig. 3a–c). It is well known that higher SST contributes to the intensification of TCs. Nevertheless, even though the MDR experiences higher SSTs in the summer, TCs exhibit greater intensity during the autumn. This indicates that factors beyond background SST alone are at play in explaining the higher TC intensity during autumn compared to summer.

Monthly variations in (a) sea surface temperature (SST, °C), b mixed-layer depth (MLD, m), c ocean thermal structure (Tssc, °C), d tropical cyclone heat potential (kJ cm−2), e maximum potential intensity (MPI, s−1), f outflow temperature (Tout, °C), g near-surface temperature (Ta, °C) (h) near-surface specific humidity (qa, g kg−1) (i) vertical wind shear (m s−1) in the western North Pacific main development region (120°E–170°E, 7.5°N–27.5°N). The red and blue circles denote the summer (June–August) and autumn (September–November) season months, respectively. The vertical bars denote the standard deviation for each month.

Climatology of (a, b) SST (°C), d, e Tropical cyclone heat potential (TCHP, kJ/cm2) (g, h) mixed layer depth (MLD, m) and (j, k) Ocean thermal structure (Tssc calculated as SST minus average T100, °C) during the summer (left column) and autumn (central column) seasons, for the period 2005–2020. Differences in (c) SST (°C), f TCHP (kJ cm−2) (i) MLD (m) and (l) Tssc (°C) between the two seasons (autumn minus summer, right column).

Shifts in prevailing TC tracks may be linked to the differences in TC intensity. In order to gain insight into the oceanic conditions encountered by TCs during the summer and autumn, we computed the along-track SST before TC’s arrival called as SSTpre and during TC called as SSTduring (Table 3). The details of the computation of SSTpre and SSTduring are mentioned earlier in the methodology section. Our analysis reveals that along-track SSTpre in summer is 0.2 °C higher than in autumn, which is statistically significant ( < 0.01). However, on the day of TC, SSTduring in autumn is 0.2 °C higher than in summer (Table 3). This highlights that in autumn, the SST underneath the TC do not decrease much due to the TC-induced forcing, which will be discussed later. Additionally, as shown earlier, TCs travel more equatorward in autumn than in summer. It is shown in previous study that a synoptic system takes longer to intensify into a stronger TC at higher latitudes than at lower latitudes42. This is attributed to the amplified Coriolis parameter with increasing latitude, resulting in an increase in inertial stability that weakens the intensification rate of TCs43. In addition, the low-level inflow in TCs at higher latitudes may not reach the inner core region as quickly as it does for low-latitude TCs, leading to lower intensity of TCs at higher latitudes43,44. Given that TCs during autumn travel more equatorward than in summer (Fig. 1), and the SST is higher near the lower latitudes as compared to higher latitudes, the autumn season furnishes more conducive conditions for TC intensification compared to the summer season.

It is documented that not only SST but also TCHP plays a pivotal role in influencing TC intensity45. Regions of high TCHP indicate warmer ocean sub-surface conditions, which reduces TC-induced SST cooling. This increases the enthalpy flux from the ocean to the atmosphere, thereby favoring TC intensification10,16,46. In the WNP, although the climatological SST is higher during summer than autumn, TCHP is slightly higher in attumn than in summer across a large part of the basin (Fig. 3d–f). Monthly variation in TCHP averaged over MDR also reveals that the peak in TCHP is in the autumn season (Fig. 2d), with the average TCHP in this season being 6.3 kJ cm−2 higher than in summer (Table 2), and the difference in TCHP between the two seasons is statistically significant (p < 0.01). We further carried out an along-track analysis for the MDR and find that along-track TCHP before TC (TCHPpre) in the autumn is 19.1% more than in summer (Table 3) and the difference is statistically significant (p < 0.01).

Along with TCHP, variations in MLD also impact TC intensity. In general, a deeper MLD leads to weakened TC-induced cooling at the sea surface, resulting in a suppressed negative feedback loop of SST cooling on TC intensity16,47,48,49. A monthly analysis using the GLORYS and EN4 dataset (Fig. 2b and Figure S1) shows that in the MDR, the most shallow MLD is observed in June, and as the year progresses towards autumn, the MLD depth increases. The spatial distribution also shows that deeper MLD is prevalent over most parts of the basin during autumn compared to summer (Fig. 3g–i). On average, MLD in the MDR is 10.9 m deeper in autumn compared to summer (Table 2) and the difference is statistically significant (p < 0.01). Using the density based criteria of defining MLD too we found that in the MDR on an average the MDR is significantly deeper in autumn than in summer (Figure S2). Thus our results are independent of the definition of MLD used in the study and we stick with the temperature based MLD criteria for further analysis. A deeper MLD in autumn also contributes to higher TCHP in this season compared to summer.

Further, to study in detail the ocean thermal structure, a new parameter called as Tssc is proposed in previous studies50 which is the difference between the SST and the average of the top 100 m ocean sub-surface temperature called T100. The smaller difference between SST and T100 indicates that the ocean sub-surface is thermally uniform, inhibiting the TC-induced SST cooling. This TC-induced SST cooling plays a significant role in suppressing the TC intensity14,51. From Fig. 2c, it can be seen that there is a marked monthly variation in the ocean thermal structure, with the most uniform thermal structure (lowest Tssc) seen in February, whereas the highest Tssc is seen in July. A spatial distribution of Tssc shows that in the autumn, over most of the areas in the basin, Tssc is less than in summer (Fig. 3j–l) and the difference between the two seasons in the MDR is 0.4 °C which is statistically significant (p < 0.01) (Table 2). The sharp thermal contrast between the surface and sub-surface in summer is due to high SSTs and weak near-surface background winds (Table 2, Fig. 4a). On the other hand, in autumn, the weakening of the thermal gradient between the surface and the sub-surface is due to the reduced solar gradient and higher near-surface wind speeds (Table 2)52,53. A more uniform ocean thermal structure in autumn than in summer indicates that in the former season, the ocean thermal structure is less favorable for TC-induced SST cooling54.

Climatology of (a, b) winds at 1000 hPa (Windsfc, m s−1), d, e near surface specific humidity computed at 1000 hPa (qa, g kg−1). g, h Near surface Air temperature computed at 1000 hPa (Ta, °C) during the summer (left column) and autumn (central column) seasons, for the period 2005–2020. Differences in (c) Windsfc (m s−1), f qa (m s−1) (i) Ta (°C) and (l) Tssc (°C) between the two seasons (autumn minus summer, right column).

In order to quantify the impact of TC-induced SST cooling and its imapct on the TC intensity in the two seasons, we have carried out the along-track analysis in the MDR for all the TC points from the genesis till LMI. To extract the TC-induced SST cooling, we have subtracted the average SST anomaly averged from day −7 to day −3 with the average SST anomaly averaged from day 0 to day +1 (see methodology section for details). On an average, the TC-induced SST cooling in the MDR in autumn is 0.07 °C less than in the summer (Table 4), which is statistically significant (p < 0.01). It is well known that TC-induced SST cooling is also a function of the intensity of TC55,56. Intense TCs cause more TC-induced SST cooling compared to weak TCs55. So, to remove the influence of TC intensity on TC-induced SST cooling, we have analyzed TC-induced cooling as a function of the TC category. We divided the various TC categories into tropical storm (wind speed < 65 knots), typhoon (Category 1 + 2, wind speed between 65 and 95 knots) and intense typhoons (Category 3 and higher, wind speed ≥ 100 knots). From Table 4, it can be seen that for the weak TCs (tropical storm category), the TC-induced SST cooling in the autumn and the summer season is −0.26 °C and −0.32 °C, respectively. This TC-induced SST cooling increases for typhoon and intense typhoon category TCs. However, even within these categories, for each individual TC category, the TC-induced cooling remains significantly less in autumn than in summer (Table 4). Weak TC-induced SST cooling observed during autumn is mainly because the TC wind-driven turbulent vertical mixing occurs over a nearly homogeneous water column with higher TCHP and deeper MLD (Fig. 3). Changing the number of days used for calulating the pre-TC average SST anomalies will not change the results (Table S1, Table S2). Thus, the reduced negative feedback from the ocean on the intensity of TC owing to the weak TC-induced SST cooling in this season, along with warm ocean surface (SSTduring) and sub-surface conditions, supports more intensification of TC than the summer season. Our findings align with prior studies that underscore the greater influences of TCHP on TC intensification in the WNP57.

It should be noted that the translational speed of a TC also has the potential to impact the TC-induced cooling. Faster-moving TCs generate weaker SST cooling and have shorter exposure to this cooling, thereby reducing the negative feedback effect on TC intensity58. Our analysis indicates that the translation speeds of TCs during the summer and autumn seasons are 5.1 m s−1 and 5.3 m s−1, respectively (Table 1). However, the difference in translation speed between the two seasons is not statistically significant at a 95% confidence level. Thus, it can be concluded that translation speed does not significantly contribute to the observed differences in the TC-induced SST cooling and has no role in the observed differences in TC intensity between these two seasons.

Air-sea interface conditions

In the preceding section, we observed that the background and the along-track ocean sub-surface conditions are more conducive for TC intensification in autumn than in summer. Alongside oceanic factors, atmospheric conditions during TCs also play an equally significant role in determining TC intensity. The warm ocean fuels TCs by providing heat flux from the ocean to the atmosphere. Increased latent heat flux from the ocean to the atmosphere induces the moistening of the boundary layer, thereby aiding TC intensification59. From Eqs. 2 and 3, it is seen that the transfer of enthalpy flux from the ocean to TC is governed by two distinct mechanisms. The first mechanism involves mechanically driven heat uptake, arising from wind-driven evaporation. The second mechanism is thermodynamically driven heat uptake, which is dependent on the air-sea thermal and moisture disequilibrium8,9. From the spatial analysis, it can be seen that except very close to the equator, the climatological near-surface atmospheric conditions are drier and cooler in autumn than in summer (Fig. 4d–i). In the MDR region, the near-surface temperature is warmer in summer than in autumn, with a peak in August (Fig. 2g). Overall, there is a difference of 0.6 °C between the two seasons (Table 2). Also, similar to the near-surface air-temperature, the near-surface humidity in the MDR is highest in August (Fig. 2h) with a difference of 0.7 g kg−1 (Table 2). In addition, from Fig. 4a–c, we can see that the background near-surface winds (1000 hPa) in the MDR are higher in autumn than in summer. The difference between the two seasons is 1.2 m s−1, which is statistically significant (p < 0.01) (Table 2). The higher wind speed in summer will facilitate the mechanically driven heat uptake due to higher wind-driven evaporation from the ocean surface. As a result, the along-track analysis shows that in autumn, the moisture disequilibrium and the thermal disequilibrium between the air-sea interface are 0.7 g kg−1 and 0.6 °C higher than in summer, respectively (Table 3) and the differences between the two seasons are statistically significant (p < 0.01). Thus, in autumn, high winds along with drier and cooler near-surface conditions facilitate higher enthalpy flux transfer from the ocean to the atmosphere, which supports more intensification of TC in this season. Our study has not explicitly quantified which process is more important in driving the heat flux from the ocean to TC. However, observations of intense TCs in the Atlantic basin highlight the more substantial role played by thermal and moisture disequilibrium compared to the latent heat flux in enchancing fluxes and TC intensification9,60,61. This phenomenon is supported by the fact that over regions with deeper warm oceans, the moisture disequilibrium increases and becomes more effective in sustaining intense enthalpy fluxes without a pronounced reliance on wind-driven evaporation62.

Background atmospheric conditions

In the preceding section, we observed that ocean sub-surface conditions, reduced TC-induced SST cooling along with the moisture and thermal disequilibrium between the ocean and near-surface, partially explaining the higher intensity of TC in autumn than in summer. Alongside oceanic factors, atmospheric conditions during TCs also play an equally significant role in determining TC intensity. The intensity of TC is directly dependent on MPI, which is a function of the SST and the outflow temperature at the top of the atmosphere63. Recent studies have shown that the MPI of TC is significantly affected by the outflow temperatures found near the tropopause63,64,65,66,67,68,69 which affects the thermodynamic efficiency. Warm SSTs lead to deep penetration of TC convection in the atmosphere and its outflow reaches the tropopause level; therefore, temperatures at that level can significantly affect the MPI. In general, higher SST and lower outflow temperature support higher MPI in a region. The outflow temperatures exhibit a marked monthly variations, with the highest temperatures are observed in summer season, and as the year progresses the outflow temperatures starts declining (Fig. 2f). The SST in the WNP is warm throughout the TC season with little seasonality, which permits TC outflow in the WNP to reach the tropopause level every month of the season. As a result, in this basin, the TC outflow temperatures and the thermodynamic efficiency follow the seasonality in the tropopause/outflow temperature70. These changes in the tropopause temperature in this basin is driven primarily by planetary wave forcing from the troposphere70,71,72. Overall, between the autumn and the summer season there is a difference of −2.4 °C in the outflow temperature which is statistically significant (p < 0.01) (Table 2). Due to the crucial role of MPI in impacting the intensity of TC, we have analyzed its role in the seasonal differences in TC intensity between the two seasons.

The seasonal cycle of TC MPI within the WNP MDR region exhibits less seasonal variability (Fig. 2e) compared to the TC MPI seasonal variations in other basins31. Earlier, we have seen that along the track of TC, SST underneath a TC, SSTduring, is on average higher in autumn than in summer (Table 3). A comparison of MPIduring as a function of SSTduring shows that for SSTs (above 27 °C), the MPIduring in autumn is greater than in the summer (Fig. 5a). This shows that autumn TC has more favorable atmospheric conditions under the same ocean conditions for intensification. To see what is contributing a higher MPIduring in autumn than in summer along the track of TC, we first analyzed the disequilibrium term which impacts the MPI. Our analysis shows that the along-track disequilibrium for all SSTs is greater in autumn than summer (Fig. 5b). The higher disequilibrium in autumn than summer is mainly due to a colder troposphere and drier boundary layer (Fig. 4f, i). Secondly, the thermodynamic efficiency also contributes in the MPI. The along-track analysis shows for all the SSTs the thermodynamic efficiency of TC is more in autumn than in summer (Fig. 5c) due to higher SSTduring and lower outflow temperatures in the former season. This is in agreement with the previous studies, which show that in the WNP, both the thermodynamic efficiency and the disequilibrium term contribute to the MPI31. Whereas, in the Atlantic, the MPI is mainly driven by the disequilibrium term due to large seasonal variation in the SST. It is well known that observed maximum intensities of TC and the along-track MPI are strongly correlated and the observed TC intensity increases with the increase in MPI29. Thus, higher MPI in the autumn season contributes to higher TC intensities in this season.

a TC maximum potential intensity (MPIduring) and its components. b thermodynamic disequilibrium term and (c) thermodynamic efficiency term against SST underneath a TC (SSTduring) in the summer (red line) and autumn (blue line) seasons. The means of value are calculated at each 0.5 °C bin for SSTduring between 27 °C and 30 °C, similar to the methodology adopted in previous study126. The filled circle denotes that the differences in the summer and the autumn seasons are statistically significant at 95% confidence level.

The favourable atmospheric conditions also support an increase in TC size73,74. An idealized numerical experiment showed that smaller TC intensify more rapidly compared to a bigger TC75. This is because in smaller TC, the deep convective clouds remain concentrated closer to the vortex center, resulting in their faster spinup. Also, the pressure gradient near the eyewall for smaller TCs is larger than for bigger TC76. Since, in a smaller TC, the pressure gradient is distributed over a smaller radial distance than a bigger TC, thus for the same central pressure, they have a higher maximum wind speed than the latter case77. We find that the TC size (R34, averaged from the genesis till LMI) is ~13 km larger in autumn than summer (Table 1) and the difference between the two seasons is statistically significant (p < 0.01). A bigger TC size generally diminishes TC intensification efficiency44. Despite a bigger TC size in autumn, the TC intensity in this season is higher than summer. This can be due to the fact that the mean ambient pressure in autumn is 2.2 hPa higher than in summer (Table 1). Thus, despite a bigger TC, the pressure gradient between the TC center and surrounding is steeper in autumn than in summer. A steeper pressure gradient is generally more conducive for the TC to intensify, resulting in a higher intensification rate44.

Another dynamic factor, the vertical wind shear, significantly influences the TC frequency and its intensity78, with high wind shear inhibiting its intensification79. A monthly variation in the vertical wind shear shows that in the MDR, the lowest vertical wind shear is observed in June, and as the year progresses, the vertical wind shear remains nearly the same from June–October and it increases sharply only from November (Fig. 2i). Overall, in autumn, the vertical wind shear is 1.1 m s−1 greater than in summer, and the difference between the two seasons is statistically significant (p < 0.01). This shows that despite slightly higher background vertical wind shear in autumn, the TCs intensify more in this season as the atmosphere is thermodynamically more favorable for the TC intensification, coupled with an equatorward shift in the TC track and favorable ocean surface and sub-surface conditions.

Discussion

Globally, the WNP basin is the most active TC basin and hosts the strongest TCs. The main TC season in this basin spans from June–November which is divided into two sub-seasons: June to August (summer season) and September to November (autumn season). Although the frequency of TCs remains almost the same between the two sub-seasons, the ocean-atmosphere characteristics change significantly32,33,34,36,80. These changes in the background conditions have the potential to significantly impact the intensity of TCs in different seasons. To investigate the seasonal differences in TC intensity between summer and autumn, we conducted an analysis for the period 2005–2020. Our findings show that the average LMI of TCs and the average wind speed of TCs in this basin are 19.8% and 14.9% higher in autumn than in summer respectively, despite the lower background SST in the MDR during the former season. Hsu et al. 81 show that in recent decades, the frequency of TCs in the autumn has been declining due to unfavorable background dynamic conditions. Also, the vertical wind shear, which plays a significant role in the intensification of TC, exhibits higher value in autumn than summer in the MDR (Table 2). Despite the decreasing frequency of TCs in the autumn and higher background wind shear, our results indicate that the TCs are stronger in this season than in the summer. A recent study by Feng et al. 82 show that that the frequency of super typhoons (TC with maximum wind speed ≥100 knots) is higher in autumn than summer and attributed it with mainly with the difference in the atmospheric conditions and SST between the two seasons. Our study has highlighted that it is not just the super typhoons frequency but also on an average the intensity of TCs (including all TCs) is higher in autumn than summer. The higher intensity of TCs in the autumn season than the summer is due to a combination of multiple factors.

Firstly, in autumn, TCs travel more equatorward and thus encounter more favorable ocean sub-surface conditions for intensification. Secondly, for the same MDR, the TC-induced SST cooling is less due to high TCHP, deeper MLD, and more uniform ocean sub-surface thermal structure during this season. The reduced TC-induced SST cooling suppresses the negative TC-induced cooling impact on the TC, which partially aids higher intensification in autumn compared to summer. Additionally, in autumn, the thermodynamic disequilibrium between the ocean surface and the lower atmosphere ensures a higher supply of enthalpy fluxes from the ocean to the atmosphere. Lastly, for the same SSTs, the MPI along the track of TC in autumn is higher than in the summer season. The difference in MPI between the two seasons is due to the differences in the thermodynamic efficiency (dominated by the outflow temperature) and the disequilibrium between the air-sea interface. The MPI is directly proportional to the intensity of TC and increases the upper limit of a TC’s observed maximum intensity. Therefore, all the factors mentioned above jointly lead to higher intensity of TC in autumn than in summer and are illustrated in Fig. 6

The subsurface temperature profile is indicated by the black line. Ocean surface cooling is indicated by the wavy lines. TCs are represented by the TC symbol (a filled TC center represents a weak TC, while a white TC center represents a strong TC). In autumn, TC intensity is more due to favorable ocean sub-surface conditions, reduced impact of SST cooling from higher TCHP and deeper MLD, and increased enthalpy flux from the ocean to the atmosphere. The higher MPI for the same SSTs also contributes to stronger TC intensity compared to summer.

This study is limited to recent period (2005–2020) due to limited availability of TC size data, however the main conclusion of the study i.e. higher intensity of TCs in autumn compared to summer is also valid for longer satellite era (1982–2020) too. For the entire satellite era, the average LMI of TC is 6.7 m s−1 more in autumn than summer. Similarly, the average maximum wind speed of TC (averaged from genesis till LMI) is 2.9 m s−1 higher in autumn than summer (Table S3). Thus, our conclusions will not change by changing the analysis period. To determine whether the higher intensity of TCs observed in the WNP during autumn compared to summer is also present in other ocean basins, we extended our analysis to the North Atlantic. We found that the average LMI in the North Atlantic in the summer and autumn season is 33.3 m s−1 and 41.1 m s−1, respectively and the difference in LMI between the two seasons is statistically significant (p < 0.01). This shows that similar to the WNP, TCs in the North Atlantic also exhibit higher intensity in autumn than in summer. An analysis of other basins and the detailed mechanisms on the difference in intensity between the two seasons for other basins will be taken up in the future.

It is observed that globally, the latitude of the LMI is shifting poleward in recent decades83,84, with the most pronounced poleward shift occurring within the WNP compared to other basins85,86,87. This poleward shift in the WNP is primarily attributed to the increasing SST, consequently increasing the MPI and expanding the region favorable for TC intensification poleward87. Such shifts in LMI location are also dependent on the changes in TC seasonality88 and are driven by evolving climatic conditions, which can significantly influence TC intensity across the two seasons and require an in-depth analysis. The intensity of TCs as well as the intensity of landfalling TCs is increasing in this basin89,90, increasing the risk of TC-induced disasters for WNP rim countries. Our study, though highlighted that TC intensity is higher in autumn than summer, as the global warming rates vary by seasons, the response of TC intensity to changing climate will also differ accordingly. This is supported by a recent study highlighting that ocean subsurface warming has led to a seasonal advancement in the occurrence of intense TCs in this basin91, potentially altering the mean TC intensity across both seasons. Therefore, a modeling study is required to understand how TC intensity will vary in the two seasons under a global warming scenario, which will be the focus of future research.

Methods

Data

In this study the TC data is obtained from Joint Typhoon Warning Center (JTWC) as archived in the International Best Track archive (IBTrACS) dataset92. While TC intensity and position data are available from the 1950s onwards, we have restricted our analysis to the period 2005–2020 due to the limited availability of TC size data. To investigate the influence of SSTs on TC intensity during the two seasons, we acquired daily SST data for the aforementioned period, from the Optimum Interpolation Sea Surface Temperature (OISST) dataset provided by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) at a spatial resolution of 0.25° × 0.25°93. The sub-surface ocean temperature and salinity data is obtained from the GLORYS12V1 provided by the Copernicus Marine Environment Monitoring Service at a spatial resolution of 1/12° with 50 vertical layers94. For the calculation of heat fluxes and maximum potential intensity (MPI), the near surface air temperature and specific humidity at pressure level 1000 hPa and atmospheric temperature from near surface to 1 hPa are obtained from the European Center for Medium Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) fifth-generation global atmospheric reanalysis (ERA5) dataset95.

The months for which TC intensity analysis is carried out are June–November and is called as the main TC season. This choice is based on the fact that the majority of TC genesis occurs in these months96,97 accounting for approximately 85% of the total annual number of TCs98. To investigate the seasonal variations in TC intensity, the main TC season is further divided into the summer season (June–August) and the autumn season (September–November)99,100,101,102,103,104,105. These two season classification further aligns with the seasonal variations in the WNP environment, including the weakening of the WNP summer monsoon, the onset of the boreal winter monsoon, and the seasonal shift associated with El Niño Southern Oscillation phase transitions105,106.

TCs are classified into different categories based on the Saffir-Simpson scale107, which defines the thresholds for each TC category as follows: tropical storm (34 knots < Vmax < 65 knots), Category 1 (65 knots ≤ Vmax < 85 knots), Category 2 (85 knots ≤ Vmax < 100 knots), Category 3 (100 knots ≤ Vmax < 115 knots), Category 4 (115 knots ≤ Vmax < 140 knots) and Category 5 (Vmax ≥ 140 knots). Here, Vmax represents the maximum wind speed of the TC, obtained from the JTWC dataset that employs a 1 min averaging period.

Methodology

In our study, cyclogenesis is defined as the first instance and position at which the system attains a wind speed of at least 35 knots. We exclude tropical depressions (with wind speeds less than 35 knots) from our analysis. We have considered the main development region (MDR) of TC cyclogenesis as 120°E-170°E, 7.5°N-27.5°N108. Changing the MDR region to a smaller region for computing the mean ocean-atmospheric conditions in the two seasons will not significantly alter the results. The LMI of a TC is defined as the first instance in its lifespan when it achieves its highest wind speed (note that some TCs may have multiple occurrences of the same maximum wind speed value109). For our analysis, we focus on the period from the genesis of the TC to its LMI, as the main objective of the study is to understand the differences in the maximum intensity of TCs between two seasons. Consequently, we do not analyze the dissipation stage of the TCs. To classify the TCs in two seasons, we use the LMI day as the dividing point. This means that if the cyclogenesis occurs in one season and the LMI occurs in another season, we assign the TC to the season corresponding to the LMI date. To calculate the TC translation speed, we employ the centered time differencing method based on changes in TC position at 6-hour intervals. For the starting position of the TC, we determine the translation speed using the forward differencing method.

To understand the impact of TC-induced SST cooling on the intensity of TC, the daily SST data at each location for the period 2005–2020 is subtracted from the daily climatology of SST to obtain the daily SST anomalies. A composite approach is employed by averaging the time series of SST anomalies before and after the passage of individual TCs at six-hour intervals along their respective tracks110. The analysis considered the evolution of composite SST anomalies averaged over a 2° × 2° gird area which is approximately a 200 km radius around each TC center position, for every 6-hourly TC location from cyclogenesis to the LMI. This coverage spanned a period starting 7 days before the TC’s passage and concluding 10 days after the TC’s passage. Day 0 corresponds to the day of TC passage, while Days −7 to −1 represent the 7 days to 1 day prior to TC passage and Days +1 to +10 denote 1 to 10 days after TC passage. The timesteps when the TC center is over land is excluded from the analysis. Finally, to compute the TC-induced SST anomaly, the initial SST anomalies averaged from Day −7 to Day −3 are subtracted from the SST anomalies averaged from Day 0 to Day +1, following the recent study111.

The SST underneath the TC henceforth, called as SSTduring, is calculated using the variable mixing depth approach and it considers TC-induced SST cooling effect, as described by Price (2009). The variable mixing depth (d) is parameterized to take into account for the TC-induced vertical turbulent mixing in the upper ocean. The parameterization assumes that the bulk Richardson number of the surface mixed layer should be at least ≥ 0.6112.

where g is the acceleration due to gravity, ρ(z) is the water density profile, z denotes the depth of the water column, τ represents the wind stress, Rh is the TC size, defined as the radius of the maximum wind speed of TC and Vh is the TC translation speed. The term Rh /Vh is defined as the TC residence time, where a longer residence time implies that a TC will impact a given area of the ocean for a longer time. S is a constant with a value of 1.2 and is similar to previous study50. To calculate SSTpre, we average the pre-TC (3 days before the TC’s arrival) ocean temperature profile from the surface down to the estimated variable depth. Similar to the SSTpre, in other variables computation too “pre” is defined as 3 days before the TC arrival.

The enthalpy flux exchange between the ocean and atmosphere plays a crucial role as the major energy source for TC genesis and intensification7,113,114. In the absence of direct in situ measurements, the two components of enthalpy fluxes, namely latent and sensible heat fluxes, are computed using the bulk aerodynamic formulas that utilize near-surface atmospheric and upper-ocean temperature data14,115,116 (Eqs. 2 and 3).

where, QS represent the sensible heat flux, CH is the sensible heat flux coefficient with a constant value of 1.1 × 10−3, ρa is the density of air, Cpa is the heat capacity of air (1005 J kg−1 K−1), Ts is the SST, Ta is the near surface air temperature, and the term Ts-Ta is called as thermal disequilibrium. W is the near surface wind speed (1-minute sustained wind speed from JTWC). QL is latent heat flux, and CE is the latent heat flux coefficient with constant value 1.2 × 10−3. Lva is the latent heat of vaporization (2.5 × 106 J kg−1), qs is the saturation specific humidity as a function of SST, and qa is the near surface air specific humidity. The difference qs-qa is known as the moisture disequilibrium62. The total enthalpy flux is obtained by summing the sensible and latent heat fluxes.

To estimate the upper ocean heat content we have calculated the Tropical Cyclone Heat Potential (TCHP), which represents the integrated ocean heat content per unit area relative to the 26 °C isotherm (Eq. 4)117. This parameter provides an estimate of the amount of energy available in the upper ocean for TC intensification.

where Cp (4178 J kg−1 °C−1) denotes the heat capacity of ocean water at constant pressure and ρ (1026 kg m−3) is the average density of the upper ocean up to the 26 °C isotherm. D26 represents the depth of 26 °C isotherm in the ocean and T is the temperature at various sub-surface levels up to D26.

We also analyzed MLD variations in the two seasons. There are several methods of determining MLD based on temperature, salinity and density criteria118,119,120. In our analysis, we have defined MLD as the depth where the temperature is 0.5 °C different from the surface-layer temperature119. Also, we have computed MLD using density-based criteria and is defined as the depth where the difference in density is 0.125 g kg−1 from the surface. We also computed the MLD using the same temperature criteria as applied to the GLORYS data, but with the EN4 analysis dataset. The EN4 analysis uses an optimal interpolation method for the reconstruction at each ocean layer, and has a spatial resolution of 1° × 1° with 42 vertical levels121.

TC extracts its energy from the underlying warm SST. Conceptually, a TC can be visualised as a heat engine, with the warm ocean acting as the reservoir of heat and the cold outflow temperature at the top of the TC serving as the other reservoir. Based on this concept, MPI estimates the maximum intensity a TC can attain under given ocean-atmosphere conditions and is calculated using Eq. 5 as shown in previous studies7,122,123.

where Ck is the surface enthalpy exchange coefficient and CD is the drag coefficient. The ratio Ck/CD is uncertain and ongoing research aims to determine this ratio but it is generally assumed to be constant124. For this study, we set Ck/CD to 0.9 based on previous studies69,125. Ts is the SST underneath the TC (SSTduring), which is calculated using the variable mixing depth (Eq. 1). To is the outflow temperature, defined as the air temperature at the level of neutral buoyancy of a parcel lifted from saturation at the SST. The efficiency of a TC represented by \(\frac{{{\rm{T}}}_{{\rm{S}}}-{{\rm{T}}}_{{\rm{o}}}}{{{\rm{T}}}_{{\rm{o}}}}\) is inversely related to the outflow temperature, where lower outflow temperatures indicate higher thermodynamic efficiency. Additionally, \({{\rm{h}}}_{{\rm{o}}}^{* }\) denotes the saturation moist static energy of the sea surface, and \({{\rm{h}}}^{* }\) is the saturation moist static energy of the free troposphere. \({{\rm{h}}}_{{\rm{o}}}^{* }-{{\rm{h}}}^{* }\) represents the disequilibrium term, which depends on the SST and any variation in this disequilibrium significantly affects the potential intensity of a TC7.

Data availability

All data used in this study are available online. The cyclone data are obtained from JTWC as archived in the IBTrACS dataset and are available at https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/ibtracs/. GLORYS reanalysis data is obtained from https://resources.marine.copernicus.eu/products. EN4 analysis data is obtained from https://www.metoffice.gov.uk/hadobs/en4/. Daily SST data are obtained from OISST available at https://psl.noaa.gov/data/gridded/data.noaa.oisst.v2.highres.html. The data of various atmospheric parameters is obtained from European Center for Medium Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) fifth-generation global atmospheric reanalysis (ERA5) dataset and is available at https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/datasets/.

Code availability

The underlying code for this study can be available on reasonable request from the corresponding author.

References

Peduzzi, P. et al. Global trends in tropical cyclone risk. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2, 289–294 (2012).

Pielke, RA. et al. Normalized Hurricane Damage in the United States: 1900-2005. Nat. Hazards Rev 9, 29–42 (2008).

Singh, V. K. & Roxy, M. K. A review of ocean-atmosphere interactions during tropical cyclones in the north Indian Ocean. Earth-Sci. Rev. 226, 103967 (2022).

Lin, I-I., Pun, I-F. & Lien, C-C. 'Category-6' supertyphoon Haiyan in global warming hiatus: Contribution from subsurface ocean warming. Geophys. Res. Lett. 41, 8547–8553 (2014).

Courtney, J. B. et al. Operational Perspectives on Tropical Cyclone Intensity Change Part 1: recent advances in intensity guidance. Trop. Cyclone Res. Rev. 8, 123–133 (2019).

Hendricks, E. A., Braun, S. A., Vigh, J. L. & Courtney, J. B. A summary of research advances on tropical cyclone intensity change from 2014-2018. Trop. Cyclone Res. Rev. 8, 219–225 (2019).

Emanuel, K. A. An Air-sea intercation theory for tropical cyclones. Part 1: Steady-State Maintenance. J. Atmos. Sci. 43, 585–604 (1986).

Gautam, R., Cervone, G., Singh, R. P. & Kafatos, M. Characteristics of meteorological parameters associated with Hurricane Isabel. Geophys. Res. Lett. 32, (2005).

Jaimes, B., Shay, L. K. & Uhlhorn, E. W. Enthalpy and momentum fluxes during hurricane earl relative to underlying ocean features. Mon. Weather Rev. 143, 111–131 (2015).

Lin, I. I., Pun, I. F. & Wu, C. C. Upper-ocean thermal structure and the western north pacific category 5 typhoons. Part II: Dependence on translation speed. Mon. Weather Rev. 137, 3744–3757 (2009).

Seo, H. & Xie, S.-P. Impact of ocean warm layer thickness on the intensity of hurricane Katrina in a regional coupled model. Meteorol. Atmos. Phys. 122, 19–32 (2013).

Pun, I.-F., Lin, I.-I. & Ko, D. S. New generation of satellite-derived ocean thermal structure for the western north pacific typhoon intensity forecasting. Prog. Oceanogr. 121, 109–124 (2014).

Shay, L. K., Goni, G. J. & Black, P. G. Effects of a Warm Oceanic Feature on Hurricane Opal. Mon. Weather Rev. 128, 1366–1383 (2000).

Cione, J. J. & Uhlhorn, E. W. Sea surface temperature variability in hurricanes: Implications with respect to intensity change. Mon. Weather Rev. 131, 1783–1796 (2003).

Hong, X., Chang, S. W., Raman, S., Shay, L. K. & Hodur, R. The Interaction between Hurricane Opal (1995) and a Warm Core Ring in the Gulf of Mexico. Mon. Weather Rev. 128, 1347–1365 (2000).

Lin, I. I., Wu, C. C., Pun, I. F. & Ko, D. S. Upper-ocean thermal structure and the Western North Pacific category 5 typhoons. Part I: Ocean features and the category 5 typhoons’ intensification. Mon. Weather Rev. 136, 3288–3306 (2008).

Wada, A. Verification of tropical cyclone heat potential for tropical cyclone intensity forecasting in the western North Pacific. J. Ocean. 71, 373–387 (2015).

Wu, C. C., Lee, C. Y. & Lin, I.-I. The effect of the ocean eddy on tropical cyclone intensity. J. Atmos. Sci. 64, 3562–3578 (2007).

DeMaria, M. & Kaplan, J. A Statistical Hurricane Intensity Prediction Scheme (SHIPS) for the Atlantic basin. Wea. Forecast. 9, 209–220 (1994).

DeMaria, M. The effect of vertical shear on tropical cyclone intensity change. J. Atmos. Sci. 53, 2076–2087 (American Meteorological Society, 1996).

Cheung, K. K. W. & Elsberry, R. L. Tropical Cyclone Formations over the Western North Pacific in the Navy Operational Global Atmospheric Prediction System Forecasts. Weather Forecast 17, 800–820 (2002).

Komaromi, W. A. & Doyle, J. D. On the Dynamics of Tropical Cyclone and Trough Interactions. J. Atmos. Sci. 75, 2687–2709 (2018).

Leroux, M.-D., Plu, M. & Roux, F. On the Sensitivity of Tropical Cyclone Intensification under Upper-Level Trough Forcing. Mon. Weather Rev. 144, 1179–1202 (2016).

Hu, C., Zhang, C., Yang, S., Chen, D. & He, S. Perspective on the northwestward shift of autumn tropical cyclogenesis locations over the western North Pacific from shifting ENSO. Clim. Dyn. 51, 2455–2465 (2018).

Huangfu, J., Huang, R., Chen, W., Feng, T. & Wu, L. Interdecadal variation of tropical cyclone genesis and its relationship to the monsoon trough over the western North Pacific. Int. J. Climatol. 37, 3587–3596 (2017).

Wang, Y., Rao, Y., Tan, Z.-M. & Schönemann, D. A statistical analysis of the effects of vertical wind shear on tropical cyclone intensity change over the western North Pacific. Mon. Wea. Rev. 143, 3434–3453 (2015).

Kossin, J. P. & Camargo, S. J. Hurricane track variability and secular potential intensity trends. Clim. Change 97, 329–337 (2009).

Kossin, J. P. & Vimont, D. J. A more general framework for understanding Atlantic hurricane variability and trends. Bull. Am. Meteor. Soc. 88, 1767–1781 (2007).

Wing, A. A., Sobel, A. H. & Camargo, S. J. Relationship between the potential and actual intensities of tropical cyclones on interannual time scales. Geophys. Res. Lett. 34, 1–5 (2007).

Gilford, D. M., Solomon, S. & Emanuel, K. A. Seasonal Cycles of Along-Track Tropical Cyclone Maximum Intensity. Mon. Weather Rev. 147, 2417–2432 (2019).

Gilford, D. M., Solomon, S. & Emanuel, K. A. On the Seasonal Cycles of Tropical Cyclone Potential Intensity. J. Clim. 30, 6085–6096 (2017).

Chu, P. C., Fan, C., Lozano, C. J. & Kerling, J. L. An airborne expendable bathythermograph survey of the South China Sea, May 1995. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 103, 21637–21652 (1998).

Chu, P. C., Edmons, N. L. & Fan, C. Dynamical Mechanisms for the South China Sea Seasonal Circulation and Thermohaline Variabilities. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 29, 2971–2989 (1999).

Liu, Q., Jia, Y., Liu, P., Wang, Q. & Chu, P. C. Seasonal and intraseasonal thermocline variability in the central south China Sea. Geophys. Res. Lett. 28, 4467–4470 (2001).

Wu, Y. et al. Effects of Environmental Relative Vorticity and Seasonal Variation on Tropical Cyclones over the Western North Pacific. Atmosphere (Basel) 13, 795 (2022).

Zhang, H., Wu, L., Huang, R. & Chen, J.-M. Intensified impact of the central Pacific warming on the monsoon trough over the western North Pacific since 1984. Atmos. Sci. Lett. 19, e828 (2018).

Wu, Y., Chen, S., Li, W., Fang, R. & Liu, H. Relative vorticity is the major environmental factor controlling tropical cyclone intensification over the Western North Pacific. Atmos. Res. 237, 104874 (2020).

Mei, W., Xie, S.-P., Zhao, M. & Wang, Y. Forced and Internal Variability of Tropical Cyclone Track Density in the Western North Pacific. J. Clim. 28, 143–167 (2015).

Tu, J.-Y., Chou, C., Huang, P. & Huang, R. An abrupt increase of intense typhoons over the western North Pacific in early summer. Environ. Res. Lett. 6, 34013 (2011).

Wu, L. & Wang, B. What Has Changed the Proportion of Intense Hurricanes in the Last 30 Years? J. Clim. 21, 1432–1439 (2008).

Ueda, H., Ohba, M. & Xie, S.-P. Important Factors for the Development of the Asian–Northwest Pacific Summer Monsoon. J. Clim. 22, 649–669 (2009).

Bister, M. Effect of Peripheral Convection on Tropical Cyclone Formation. J. Atmos. Sci. 58, 3463–3476 (2001).

DeMaria, M. & Pickle, J. D. A Simplified System of Equations for Simulation of Tropical Cyclones. J. Atmos. Sci. 45, 1542–1554 (1988).

Moon, I.-J., Knutson, T. R., Kim, H.-J., Babanin, A. V. & Jeong, J.-Y. Why Do Eastern North Pacific Hurricanes Intensify More and Faster than Their Western-Counterpart Typhoons with Less Ocean Energy? Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 103, E2604–E2627 (2022).

Wang, G., Zhao, B., Qiao, F. & Zhao, C. Rapid intensification of Super Typhoon Haiyan: the important role of a warm-core ocean eddy. Ocean Dyn. 3, 1649–1661 (2018).

Lin, I.-I. et al. The Interaction of Supertyphoon Maemi (2003) with a Warm Ocean Eddy. Mon. Weather Rev. 133, 2635–2649 (2005).

Bender, M. A. & Ginis, I. Real-case simulations of hurricane-ocean interaction using a high-resolution coupled model: Effects on hurricane intensity. Mon. Weather Rev. 128, 917–946 (2000).

Pun, I.-F., Lin, I.-I. & Lo, M.-H. Recent increase in high tropical cyclone heat potential area in the Western North Pacific Ocean. Geophys. Res. Lett. 40, 4680–4684 (2013).

Wu, L., Wang, B. & Braun, S. A. Impacts of Air–Sea Interaction on Tropical Cyclone Track and Intensity. Mon. Weather Rev. 133, 3299–3314 (2005).

Price, J. F. Metrics of hurricane-ocean interaction: vertically-integrated or vertically-averaged ocean temperature? Ocean Sci. 5, 351–368 (2009).

Lloyd, I. D. & Vecchi, G. A. Observational evidence for oceanic controls on hurricane intensity. J. Clim. 24, 1138–1153 (2011).

Guan, S. et al. Tropical cyclone-induced sea surface cooling over the Yellow Sea and Bohai Sea in the 2019 Pacific typhoon season. J. Mar. Syst. 217, 103509 (2021).

D’Asaro, E. A. et al. Impact of Typhoons on the Ocean in the Pacific. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 95, 1405–1418 (2014).

Singh, V. K., Kim, H.-J. & Moon, I.-J. Seasonal differences in tropical cyclone—induced sea surface cooling in the western North Pacific. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 150, 447–461 (2024).

Mei, W., Lien, C. C., Lin, I. I. & Xie, S. P. Tropical cyclone-induced ocean response: A comparative study of the south China sea and tropical northwest Pacific. J. Clim. 28, 5952–5968 (2015).

Mei, W. & Pasquero, C. Spatial and temporal characterization of sea surface temperature response to tropical cyclones. J. Clim. 26, 3745–3765 (2013).

Wada, A. & Usui, N. Importance of tropical cyclone heat potential for tropical cyclone intensity and intensification in the Western North Pacific. J. Oceanogr. 63, 427–447 (2007).

Mei, W., Pasquero, C. & Primeau, F. The effect of translation speed upon the intensity of tropical cyclones over the tropical ocean. Geophys. Res. Lett. 39, 1–6 (2012).

Gao, S. & Chiu, L. S. Surface latent heat flux and rainfall associated with rapidly intensifying tropical cyclones over the western North Pacific. Int. J. Remote Sens. 31, 4699–4710 (2010).

Jaimes, B., Shay, L. K. & Brewster, J. K. Observed air-sea interactions in tropical cyclone Isaac over loop current mesoscale eddy features. Dyn. Atmos. Ocean. 76, 306–324 (2016).

Rudzin, J. E., Shay, L. K. & de la Cruz, B. J. The impact of the Amazon–Orinoco River plume on enthalpy flux and air–sea interaction within Caribbean Sea tropical cyclones. Mon. Wea. Rev. 147, 931–950 (2019).

Jaimes de la Cruz, B., Shay, L. K., Wadler, J. B. & Rudzin, J. E. On the Hyperbolicity of the Bulk Air–Sea Heat Flux Functions: Insights into the Efficiency of Air–Sea Moisture Disequilibrium for Tropical Cyclone Intensification. Mon. Weather Rev. 149, 1517–1534 (2021).

Emanuel, K., Solomon, S., Folini, D., Davis, S. & Cagnazzo, C. Influence of Tropical Tropopause Layer Cooling on Atlantic Hurricane Activity. J. Clim. 26, 2288–2301 (2013).

Ge, X., Shi, D. & Guan, L. Monthly variations of tropical cyclone rapid intensification ratio in the western North Pacific. Atmos. Sci. Lett. 19, e814 (2018).

Polvani, L. M., Camargo, S. J. & Garcia, R. R. The importance of the Montreal Protocol in mitigating the potential intensity of tropical cyclones. J. Clim. 29, 2275–2289 (2016).

Ramsay, H. A. The Effects of Imposed Stratospheric Cooling on the Maximum Intensity of Tropical Cyclones in Axisymmetric Radiative–Convective Equilibrium. J. Clim. 26, 9977–9985 (2013).

Sobel, A. H. et al. Human influence on tropical cyclone intensity. Science. 353, 242–246 (2016).

Vecchi, G. A. On the seasonal forecasting of regional tropical cyclone activity. J. Clim. 27, 7994–8016 (2014).

Wang, S., Camargo, S. J., Sobel, A. H. & Polvani, L. M. Impact of the Tropopause Temperature on the Intensity of Tropical Cyclones: An Idealized Study Using a Mesoscale Model. J. Atmos. Sci. 71, 4333–4348 (2014).

Yulaeva, E., Holton, J. R. & Wallace, J. M. On the cause of the annual cycle in tropical lower-stratospheric temperatures. J. Atmos. Sci. 51, 169–174 (1994).

Reid, G. C. Seasonal and interannual temperature variations in the tropical stratosphere. J. Geophys. Res. 99, 18 923–18 932 (1994).

Fueglistaler, S. et al. Tropical tropopause layer. Rev. Geophys. 47, RG1004 (2009).

Chan, K. T. F. & Chan, J. C. L. Impacts of initial vortex size and planetary vorticity on tropical cyclone size. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 140, 2235–2248 (2014).

Hill, K. A. & Lackmann, G. M. Influence of Environmental Humidity on Tropical Cyclone Size. Mon. Weather Rev. 137, 3294–3315 (2009).

Kilroy, G. & Smith, R. K. The effects of initial vortex size on tropical cyclogenesis and intensification. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 143, 2832–2845 (2017).

Hoarau, K., Lander, M., De Guzman, R., Guard, C. & Barba, R. Did Typhoon Haiyan have a new record-minimum pressure? Weather 72, 291–295 (2017).

Knaff, J. A. & Zehr, R. M. Reexamination of Tropical Cyclone Wind–Pressure Relationships. Weather Forecast 22, 71–88 (2007).

Shan, K. et al. How does globally accumulated tropical cyclone energy vary in response to a changing climate? Sci. Bull. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scib.2024.12.036 (2024).

Kaplan, J. & DeMaria, M. Large-scale characteristics of rapidly intensifying tropical cyclones in the North Atlantic basin. Weather Forecast 18, 1093–1108 (2003).

Hao, J., Chen, Y., Wang, F. & Lin, P. Seasonal thermocline in the China Seas and northwestern Pacific Ocean. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean 117, 1–14 (2012).

Hsu, P.-C., Chu, P.-S., Murakami, H. & Zhao, X. An Abrupt Decrease in the Late-Season Typhoon Activity over the Western North Pacific. J. Clim. 27, 4296–4312 (2014).

Feng, Z. et al. Why Super Typhoon Occurrence Over the Western North Pacific Ocean Tends to be More in Autumn Than Summer. Int. J. Climatol. 45, e8694 (2024).

Kossin, J. P., Emanuel, K. A. & Vecchi, G. A. The poleward migration of the location of tropical cyclone maximum intensity. Nature 509, 349–352 (2014).

Kossin, J. P., Emanuel, K. A. & Camargo, S. J. Past and Projected Changes in Western North Pacific Tropical Cyclone Exposure. J. Clim. 29, 5725–5739 (2016).

Moon, I.-J., Kim, S.-H., Klotzbach, P. & Chan, J. C. L. Roles of interbasin frequency changes in the poleward shifts of the maximum intensity location of tropical cyclones. Environ. Res. Lett. 10, 104004 (2015).

Sun, J., Wang, D., Hu, X., Ling, Z. & Wang, L. Ongoing Poleward Migration of Tropical Cyclone Occurrence Over the Western North Pacific Ocean. Geophys. Res. Lett. 46, 9110–9117 (2019).

Song, J. & Klotzbach, P. J. What Has Controlled the Poleward Migration of Annual Averaged Location of Tropical Cyclone Lifetime Maximum Intensity Over the Western North Pacific Since 1961? Geophys. Res. Lett. 45, 1148–1156 (2018).

Feng, X., Klingaman, N. P. & Hodges, K. I. Poleward migration of western North Pacific tropical cyclones related to changes in cyclone seasonality. Nat. Commun. 12, 6210 (2021).

Elsner, J. B. Continued Increases in the Intensity of Strong Tropical Cyclones. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 101, E1301–E1303 (2020).

Mei, W. & Xie, S. P. Intensification of landfalling typhoons over the northwest Pacific since the late 1970s. Nat. Geosci. 9, 753–757 (2016).

Shan, K., Lin, Y., Chu, P.-S., Yu, X. & Song, F. Seasonal advance of intense tropical cyclones in a warming climate. Nature 623, 83–89 (2023).

Knapp, K. R. et al. The International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS). Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 91, 363–376 (2010).

Reynolds, R. W. et al. Daily High-Resolution-Blended Analyses for Sea Surface Temperature. J. Clim. 20, 5473–5496 (2007).

Jean-Michel, L. et al. The Copernicus Global 1/12° Oceanic and Sea Ice GLORYS12 Reanalysis. Front. Earth Sci 9, 698876 (2021).

Hersbach, H. et al. The ERA5 global reanalysis. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 146, 1–51 (2020).

Balaguru, K., Taraphdar, S., Leung, L. R., Foltz, G. R. & Knaff, J. A. Cyclone-cyclone interactions through the ocean pathway. Geophys. Res. Lett. 41, 6855–6862 (2014).

Chan, J. C. L. Interannual and interdecadal variations of tropical cyclone activity over the western North Pacific. Meteorol. Atmos. Phys. 89, 143–152 (2005).

Song, J. & Klotzbach, P. J. Relationship Between the Pacific-North American Pattern and the Frequency of Tropical Cyclones Over the Western North Pacific. Geophys. Res. Lett. 46, 6118–6127 (2019).

Chen, T.-C., Weng, S.-P., Yamazaki, N. & Kiehne, S. Interannual Variation in the Tropical Cyclone Formation over the Western North Pacific. Mon. Weather Rev. 126, 1080–1090 (1998).

Yao, X., Zhao, D. & Li, Y. Autumn Tropical Cyclones over the Western North Pacific during 1949–2016: A Statistical Study. J. Meteorol. Res. 34, 150–162 (2020).

Ma, X., Xie, F., Chen, X., Liu, N. & Liang, R. The frequency of autumn western North Pacific tropical cyclone linking to spring western Pacific SST anomalies. Environ. Res. Lett. 19, 84019 (2024).

Zhang, W., Leung, Y. & Fraedrich, K. Different El Niño types and intense typhoons in the Western North Pacific. Clim. Dyn. 44, 2965–2977 (2015).

Ling, S. & Lu, R. Tropical Cyclones over the Western North Pacific Strengthen the East Asia—Pacific Pattern during Summer. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 39, 249–259 (2022).

Hsu, P.-C. et al. Role of scale interactions in the abrupt change of tropical cyclone in autumn over the Western North Pacific. Clim. Dyn. 49, 3175–3192 (2017).

Basconcillo, J., Cha, E.-J. & Moon, I.-J. Characterizing the highest tropical cyclone frequency in the Western North Pacific since 1984. Sci. Rep. 11, 14350 (2021).

Lyon, B., Cristi, H., Verceles, E. R., Hilario, F. D. & Abastillas, R. Seasonal reversal of the ENSO rainfall signal in the Philippines. Geophys. Res. Lett. 33, L24710 (2006).

Webster, P. J., Holland, G. J., Curry, J. A. & Chang, H. R. Atmospheric science: Changes in tropical cyclone number, duration, and intensity in a warming environment. Science. 309, 1844–1846 (2005).

Wu, L., Wang, R. & Feng, X. Dominant Role of the Ocean Mixed Layer Depth in the Increased Proportion of Intense Typhoons During 1980–2015. Earth’s Futur. 6, 1518–1527 (2018).

Emanuel, K. A Statistical Analysis of Tropical Cyclone Intensity. Mon. Weather Rev. 128, 1139–1152 (2000).

Hart, R. E., Maue, R. N. & Watson, M. C. Estimating local memory of tropical cyclones through MPI anomaly evolution. Mon. Weather Rev. 135, 3990–4005 (2007).

Ling, Z., Chen, Z., Wang, G., He, H. & Chen, C. Recovery of Tropical Cyclone Induced SST Cooling Observed by Satellite in the Northwestern Pacific Ocean. Remote Sensing 13, 1–15 (2021).

Price, J. F. Upper Ocean Response to a Hurricane. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 11, 153–175 (1981).

Craig, G. C. & Gray, S. L. CISK or WISHE as the Mechanism for Tropical Cyclone Intensification. J. Atmos. Sci. 53, 3528–3540 (1996).

Ooyama, K. K. V. Numerical simulation of the life cycle of tropical cyclones. J. Atmos. Sci. 26, 3–40 (1969).

Jacob, S. D. & Shay, L. K. The Role of Oceanic Mesoscale Features on the Tropical Cyclone–Induced Mixed Layer Response: A Case Study. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 33, 649–676 (2003).

Lin, I.-I., Goni, G. J., Knaff, J. A., Forbes, C. & Ali, M. M. Ocean heat content for tropical cyclone intensity forecasting and its impact on storm surge. Nat. Hazards 66, 1481–1500 (2013).

Leipper, D. F., Volgenau, D. & Volgenau, L. D. Hurricane heat potential of the Gulf of Mexico. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 2, 218–224 (1972).

de Boyer Montégut, C. Mixed layer depth over the global ocean: An examination of profile data and a profile-based climatology. J. Geophys. Res. 109, C12003 (2004).

Monterey, G. & Levitus, S. Seasonal Variability of Mixed Layer Depth for the World Ocean. vol. 14 (1997).

Weller, R. A. & Plueddemann, A. J. Observations of the vertical structure of the oceanic boundary layer. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 101, 8789–8806 (1996).

Good, S. A., Martin, M. J. & Rayner, N. A. EN4: Quality controlled ocean temperature and salinity profiles and monthly objective analyses with uncertainty estimates. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 118, 6704–6716 (2013).

Holland, G. J. The Maximum Potential Intensity of Tropical Cyclones. J. Atmos. Sci. 54, 2519–2541 (1997).

Emanuel, K. A. Some Aspects of Hurricane Inner-Core Dynamics and Energetics. J. Atmos. Sci. 54, 1014–1026 (1997).

Emanuel, K. Tropical Cyclones. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 31, 75–104 (2003).

Wing, A. A., Emanuel, K. & Solomon, S. On the factors affecting trends and variability in tropical cyclone potential intensity. Geophys. Res. Lett. 42, 8669–8677 (2015).

Xu, J., Wang, Y. & Yang, C. Factors Affecting the Variability of Maximum Potential Intensity (MPI) of Tropical Cyclones Over the North Atlantic. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 124, 6654–6668 (2019).

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the Korea Meteorological Administration Research and Development Program under Grant (RS-2023-00239702) and supported by “Study on Northwestern Pacific Warming and Genesis and Rapid Intensification of Typhoon” funded by the Korean Ministry of Oceans and Fisheries (RS-2022-KS221667). The authors are grateful to HeyYun from Jeju National University, South Korea and Varsha Saini from Regional Centre for Biotechnology, India for assisting in plotting some of the figures.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

V.K.S.: Conceptualization; investigation; software; visualization; writing–original draft. H.J.K.: Methodology; data curation; formal analysis; software; writing–review and editing. I.J.M.: Project administration; funding acquisition; resources; supervision; conceptualization; methodology; writing–review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Singh, V.K., Kim, HJ. & Moon, IJ. Mechanism driving stronger tropical cyclones in cooler autumn than the hottest summer. npj Clim Atmos Sci 8, 132 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-01008-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-01008-w

This article is cited by

-

Unusual role of positive Indian Ocean Dipole in the record-low tropical cyclone genesis over the Western North Pacific in 2023

npj Climate and Atmospheric Science (2025)