Abstract

The high occurrence of compound drought and heatwave events (CDHWs), driven by global climate change, poses a serious threat to humanity. However, their impacts on rural and urban populations remain unclear. This study analyzed CDHWs exposure in both rural and urban populations and found that the number of people chronically exposed to CDHWs has shown a clear upward trend over time. From 1901 to 2021, rural populations experienced 2.5 times the total exposure to CDHWs compared to urban populations. Over the past three decades, however, urban populations have experienced significantly higher exposure and a faster rate of increase than rural populations. Regionally, rural populations in Asia, North America, and Africa accounted for 41.06, 16.51, and 13.69% of the total global rural population exposure, respectively, while urban populations in Asia, North America, and Europe accounted for 32.31, 18.70, and 16.85% of global urban exposure, respectively. The climate-population interactive effects have been the dominant factors driving recent changes in population exposure. Our findings contribute to the risk assessment of CDHWs at both global and regional levels and provide reliable information for disaster prevention and mitigation strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Since the Industrial Revolution, global temperatures have risen significantly compared to pre-industrial levels, resulting in a high occurrence of extreme weather events1,2. Heatwave and extreme precipitation events have been increasingly prominent with droughts becoming more severe in arid regions and precipitation increasing in already wet areas, leading to an increase in population deaths, ecological damage, reduced agricultural yields, and socio-economic losses3,4. While a single event can have severe consequences, the simultaneous occurrence of any two or more extreme events in the same moment and place greatly increases the risk of extreme compound events (CEs)5. It has been shown that climate change-induced compound drought and heatwave events (CDHWs) are one of the most serious CEs currently causing population deaths and economic losses due to their long duration, high destructiveness, and wide range of impacts6. Therefore, studying the spatial and temporal evolution and climatic drivers of CDHWs over historical periods is crucial for risk assessment, adaptation, and mitigation strategies for such CEs.

The increasing intensity, duration, and frequency of CDHWs pose significant threats to human health and mortality, particularly during summer months. These events can have impacts up to twice as severe as individual heatwaves (HWs) or droughts due to their compounding effects7,8. Studies of CDHWs based on different metrics have found a significant increase in the frequency of such combined events in densely populated regions, such as China, Australia, India, Europe, and Africa9,10,11. Thus, it is crucial to illuminate global population exposure to CDHWs. However, given the differences in the timescales of droughts and HWs, as well as the variations in their feedback mechanisms across different regions and climates, relative threshold definitions may be more appropriate than absolute thresholds to characterize both HWs and droughts12,13. Temperature is not only used to quantify HWs, but it also plays a key role in drought formation mechanisms. Therefore, it is more effective to define drought using a drought index incorporating temperature when identifying CDHWs. Additionally, most global-scale analyses employ spatial resolutions coarser than 1° or 2°, which does not accurately capture changes in population exposure in different subregions14,15. Studying changes in population exposure to CDHWs at high resolution is critical for understanding how to mitigate the impacts of anthropogenic climate change and thereby improve regional capacity to adapt to CDHWs.

Although previous studies have provided insights into CDHWs including identifying CDHWs16, characterizing changes17, and projecting the future18, they have largely overlooked the health impacts of CDHWs on rural and urban populations. Although the global population is urbanizing at an unprecedented rate, rural populations continue to account for half of the global population. Rural poverty accounts for 79% of global poverty, and the poverty rate in rural areas is more than three times that in urban areas19. Of the two billion people worldwide without access to basic health services, 70% live in rural areas; energy access in rural areas is limited to about 75%. Only 20% of rural populations have access to basic social security, with wages that are usually low, paid late, and not subject to regular increases20. Additionally, more than two-thirds of the rural population resides in low and middle income countries, which are hotspots for CDHWs, exacerbating the impacts on rural populations. Warm summer periods are the busy season for agriculture, requiring long hours of outdoor work, which, coupled with poor economic conditions, underdeveloped infrastructure, and significant gaps in healthcare services, makes rural areas highly vulnerable to CDHWs21,22. With the development of urbanization, the urban population has surpassed that of rural areas, drawing more attention to cities. Studies have shown that urbanization and the urban heat island effect significantly exacerbate CDHWs23,24. There is an urgent need for a comparative assessment of the impacts of CDHWs on rural and urban populations, since it yet thoroughly understood which population is more exposed.

We utilized long time series monthly standardized precipitation evapotranspiration index (SPEI) and self-calibrating palmer drought severity index (scPDSI) data at a spatial resolution of 0.5° × 0.5°, combined with monthly maximum temperature data from Climatic Research Unit gridded Time Series Version 4.07 (CRU TS-4.07), to study the evolutionary trend of global terrestrial CDHWs for rural and urban populations over the past 121 years and analyze the differences in the exposure of rural and urban populations to CDHWs. We assessed the relative contributions of climate change and population change to changes in exposure. The specific objectives of this study as follows: a) to assess the spatiotemporal evolution of global CDHWs based on multiple indicators, b) to compare the exposure differences between rural and urban populations under CDHWs, and c) to quantify the role of climate change, population change, and their interactions on exposure changes.

Results

Characterization of changes in CDHWs

Figure 1 illustrates the spatiotemporal variation characteristics of CDHWs identified based on the SPEI (CDHWs-SPEI) and scPDSI (CDHWs-scPDSI) over the global land area from 1901 to 2021. In terms of the overall characteristics of spatio-temporal changes, the CDHWs identified by the two indices show highly consistent trends. All results show a significant upward trend in global CDHWs, with an increase rate of about 200% (from 0.01 to 0.03 months) in CDHWs-SPEI, and an increase rate of about 300% (from 0.005 to 0.02 months) in CDHWs- scPDSI. Arid regions, including central Asia, central North America, central Australia, and southeastern South America, exhibit a pronounced rise in CDHWs-SPEI, with annual increases exceeding 0.05 months. While the spatial distribution of CDHWs-scPDSI aligns closely with that of CDHWs-SPEI, the magnitude of CDHWs-scPDSI is slightly lower (Supplementary Figs. 2, 3). Notably, Northern Africa, the Amazon Basin of South America, and central Australia are the regions with the highest occurrence of CDHWs, reaching 0.08 months per year. The CDHWs-scPDSI and CDHWs-SPEI are highly correlated in time and space. The difference is that the occurrence range of CDHWs-SPEI is significantly larger than CDHWs-scPDSI. In the last three decades (1991–2021), the occurrence of CDHWs-SPEI was twice as high as that identified by CDHWs-scPDSI. From a spatial perspective, the incidence of CDHWs-SPEI was significantly higher than that of CDHWs-scPDSI in Central Asia, eastern Europe, northern Africa, central and southern Australia, and southwestern China (Supplementary Fig. 4). The average annual occurrence rate of CDHWs higher than 0.02 months is 24.8% for CDHWs-SPEI and 17.74% for CDHWs-scPDSI. Notably, the annual occurrence rate of CDHWs higher than 0.06 months is 0.68% for CDHWs-SPEI, whereas it is only 0.07% for CDHWs-scPDSI. This also indicates that the occurrence of CDHWs-SPEI is much higher than that CDHWs-scPDSI.

Given the heterogeneity of CDHWs in different regions of the globe, we explored the variation in their occurrence across 44 terrestrial subregions as proposed by the IPCC-AR6 (Supplementary Fig. 1). As shown in Fig. 2, the spatial trend of CDHWs-SPEI is consistent with that of CDHWs-scPDSI, but in almost all regions of the globe, the occurrence of CDHWs identified by SPEI is significantly higher than those identified by scPDSI. The NZ region in Oceania, the CAR region in North America, and the GIC region have almost no CDHWs. The CDHWs in the three subregions of Europe are more evenly distributed. In Asia, the ESB, EAS, SAS, and Russian-Arctic (RAR) regions have significantly higher occurrences of CDHWs, with the largest difference in the Sahara (SAH) region in Africa, consistent with the scPDSI data masking effects in this region. The NSA and SES regions of South America have the highest occurrence of CDHWs, exceeding 300 months. Among the six continents, Asia has the highest occurrence of CDHWs (CDHWs-SPEI: 4492.19 months, CDHWs-scPDSI: 2664.12 months), followed by North America (CDHWs-SPEI: 2671.32 months, CDHWs-scPDSI: 1645.64 months), with the smallest occurrence in the GIC region, which has almost no CDHWs. The CDHWs in Asia are mainly concentrated in arid regions, while in North America they are concentrated in the central United States and northern regions. Notably, the occurrence of CDHWs identified by SPEI is almost twice that identified by scPDSI. This indicates significant spatial heterogeneity in the occurrence of CDHWs globally, particularly in arid regions, highlighting the need for in-depth analysis targeting small regions with high occurrence rates.

Changes in rural and urban population

The global population has exhibited a significant upward trend, although its spatial distribution remains notably uneven. Asia, in particular, stands out as the most populous continent, with its population primarily concentrated in three countries: India, China, and Japan, which together account for over 50% of the continent’s total (Fig. 3). Africa, on the other hand, contributes 17% of the global population. In both Asia and Africa, rural populations still constitute more than 60% of the respective regional totals. In India, rural areas dominate demographically, with 71% of the population residing in these regions, compared to 29% in urban areas. China, too, displayed similar rural dominance during the 20th century, where rural residents accounted for over 60% of the population, and urban residents comprised only 30%. Conversely, Europe is characterized by a predominantly urban population, with ≈75% of the population residing in urban areas and only 25% in rural areas. This high degree of urbanization contrasts with the rural dominance observed in Asia and Africa. In North America, the majority of the population is concentrated in the east-central United States, with urban residents comprising 80% and rural residents 20% of the total. While both rural and urban global populations are increasing, urban population growth is outpacing rural growth at a remarkable rate. Over the past two decades, the urban population has grown ≈six times faster than the rural population. By 2020, global population projections indicated ≈3.5 billion rural residents and 4.5 billion urban residents. This trend is underscored by a milestone reported by the United Nations in 2008, when the global urban population surpassed the rural population for the first time in recorded history. Looking beyond 2020, while rural population growth is expected to slow significantly, urban population growth is projected to continue its exponential trajectory, driven by increasing urbanization and demographic shifts.

Population exposure to CDHWs

The analysis reveals significant temporal trends in global rural and urban populations exposed to CDHWs-SPEI from 1901 to 2021, with a pronounced increase over time (Fig. 4). Both rural and urban populations experienced relatively stable exposure levels before the 1970s, but a marked upward trend emerged thereafter. This growth accelerated in the 1990s, with urban populations showing a significantly faster rate of increase compared to rural populations. Between 1991 and 2021, urban exposure to CDHWs-SPEI grew at an average rate of ≈7.9 × 10⁷ person-months per decade, surpassing the rural exposure growth rate of 3 × 10⁷ person-months per decade. Spatially, India and China, being large agricultural countries, have a consistently higher percentage of agricultural population compared to urban population. Consequently, the rural population in these countries is significantly more exposed to CDHWs compared to the urban population, with exposures the highest in the southern and northern regions of India, and the northern region of China. These regions, being the main food-producing bases, face more intense CDHWs, which may threaten future food security. By 1990s, urban population exposure exceeded rural population exposure by about 3 × 108 person-months, and by 2020, this difference grew to about 4 × 108 person-months. The proportion of the rural population with exposures of 0.4 × 104 person-months and above is significantly higher at 7.89% compared to the urban population at 5.93%. Similarly, the proportions of the rural and urban populations with exposures of 1.6 × 104 person-months and above are 1.78% and 1.43%, respectively. Despite the urban population’s exposure gradually surpassing the rural population’s exposure over the last 30 years, the rural population still requires attention due to its high vulnerability. Under the CDHWs-SPEI, exposure for rural populations is mainly concentrated in developing countries, while urban population exposure is primarily found in developed countries, such as those in Europe and the United States (Supplementary Fig. 5). This distribution correlates with the spatial distribution of rural and urban populations. With the development of global urbanization, it is expected that the surge of urban population in the future will lead to higher exposure of urban populations.

The red and green dotted lines represent linear trends for 1901–2021 and 1991–2021, respectively, with asterisks indicating statistically significant trends (95% confidence level). The spatial map depicts the multi-year average distribution of rural and urban population exposure to CDHWs-SPEI (in ×104 person-months) from 1901 to 2021.

Globally, the exposure of rural and urban populations to CDHWs-SPEI is highly correlated with the occurrence of CDHWs-SPEI in 44 subregions. In terms of total exposure, the global exposure of the rural population is about 2.47 times higher than that of the urban population. Regionally, the highest population exposure remains in Asia at 4012.42 × 104 person-months, accounting for 38.66% of the global total rural population exposure. This is followed by North America with 16.07% of the total global rural exposure, Africa with 15.75% of the total global rural exposure, and the lowest, again in the GIC region (Fig. 5). In Asia and Oceania, there is a significant disparity in exposure between rural and urban populations. In Asia, the exposure of the rural population is about three times higher than that of the urban population, and in Oceania, the exposure of the rural population is about 4.5 times higher than that of the urban population (Supplementary Table. 1). This disparity may be related to the wider distribution of the rural population in these regions and the relative concentration of the urban population. In Europe, the difference in exposure between rural and urban populations is minimal. In North America, the difference in exposure between rural and urban populations is also not too great, except in the W. North-America, N.W. North-America, and N.E. North-America regions, where rural population exposure is significantly higher. This higher exposure in northern regions may be related to the predominantly northern distribution of rural populations in North America. In Africa, the lowest exposed region is Madagascar, and the difference in exposure between the rural and urban populations in the SAH region is significant, with the rural population exposed ≈six times more (448 × 104 person-months) than the urban population (74 × 104 person-months).

The radar plots display the mean annual exposure (in units of 104 person-months) for rural and urban populations under CDHWs-SPEI across the studied regions. Exposure values are calculated by overlaying CDHWs-SPEI occurrence data with population distributions for each region. Each radar plot shows the combined exposure from rural and urban populations, with red colors representing rural population exposure and green colors representing urban population exposure to CDHWs-SPEI. The exposure trends are derived as the average of regional exposure values computed for the period 1901–2021. Differences between rural and urban exposures reflect spatial variations in population density and regional susceptibility to CDHWs-SPEI.

Similar to CDHWs-SPEI, the exposure of rural and urban populations to CDHWs-scPDSI exhibited a clear increasing trend over time, with a highly similar spatial distribution. High-exposure regions were primarily concentrated in Asia, North America, and Europe (Fig. 6). Prior to the 1970s, there was little discernible trend in rural and urban population exposure to CDHWs-scPDSI. However, starting in the 1970s, exposure began to rise significantly. From the 1970s to the 1990s, rural populations experienced greater exposure to CDHWs-scPDSI compared to urban populations. After the 1990s, the urban population exposure rate increased sharply, averaging 6.3 × 10⁷ person-months per decade, far exceeding the rural population exposure rate of 1.3 × 10⁷ person-months per decade. Unlike the patterns observed for CDHWs-SPEI, the disparity between rural and urban population exposures under CDHWs-scPDSI was relatively smaller. The proportion of rural populations experiencing exposures of 0.4 × 10⁴ person-months and above was 5.82%, compared to 4.43% for urban populations. For exposures exceeding 1.6 × 10⁴ person-months, these proportions were 1.17% for rural populations and 1.01% for urban populations. Despite these differences, the global correlation between urban and rural populations exposed to CDHWs-scPDSI and CDHWs-SPEI is high, with similar temporal and spatial change characteristics. High-exposure areas for urban populations were mainly in East Asia, parts of South Asia, most of Europe, and the eastern part of North America (Supplementary Fig. 6). Overall, exposure levels under CDHWs-scPDSI were lower than those under CDHWs-SPEI for both rural and urban populations. These findings highlight consistent trends in population exposure to compound drought-heatwave events across metrics, while also revealing subtle differences in the magnitude of impacts between CDHWs-scPDSI and CDHWs-SPEI.

The red and green dotted lines represent linear trends for 1901–2021 and 1991–2021, respectively, with asterisks indicating statistically significant trends (95% confidence level). The spatial map depicts the multi-year average distribution of rural and urban population exposure to CDHWs-scPDSI (in ×104 person-months) from 1901 to 2021.

On a global scale, across 44 small regions, the total rural population exposure under CDHWs-scPDSI was about 2.51 times higher than the total urban population exposure. Rural and urban exposures under CDHWs-scPDSI were also highly consistent with CDHWs-SPEI at small regional scales (Fig. 7). Differences were notable only in Africa, where rural population exposure was highest in the SAH region under CDHWs-SPEI (448 × 104 person-months), while ESAF had the highest exposure under CDHWs-scPDSI (120.17 × 104 person-months). Population exposures in other regions under CDHWs-scPDSI were almost the same as those under CDHWs-SPEI, though the magnitudes were lower than those of CDHWs-SPEI. In terms of total population exposures across the six continents, Asia had the highest exposure under CDHWs-scPDSI (2239.2 × 104 person-months), accounting for 43.46% of the global rural population exposure, followed by North America with 932.68 × 104 person-months, accounting for 16.95% of the global rural population exposure. The lowest exposure was in GIC, consistent with CDHWs-SPEI, but the magnitude of CDHWs-SPEI was 1.68 times that of CDHWs-scPDSI (Supplementary Table. 2). The gap between rural and urban population exposure under CDHWs-scPDSI was significantly higher in Asia, Oceania, North America, and Africa than in South America and Europe. For small regions, the same was true for the South-American-monsoon region, the N.Eastern-Africa and SAH regions, the C.Australia (CAU) region, and the RAR region. In almost every region where rural population exposure is high, urban population exposure is also high, showing a consistent trend. Therefore, when choosing different drought indicators to identify CDHWs, although there is no significant difference in trend and spatial differentiation, there is a significant difference in the magnitude of population exposure in small regions. Ignoring the influence of drought indicators on identified CDHWs could lead to overestimations and underestimations conclusions.

The radar plots display the mean annual exposure (in units of 104 person-months) for rural and urban populations under CDHWs-scPDSI across the studied regions. Exposure values are calculated by overlaying CDHWs-scPDSI occurrence data with population distributions for each region. Each radar plot shows the combined exposure from rural and urban populations, with red colors representing rural population exposure and green colors representing urban population exposure to CDHWs-scPDSI. The exposure trends are derived as the average of regional exposure values computed for the period 1901–2021. Differences between rural and urban exposures reflect spatial variations in population density and regional susceptibility to CDHWs-scPDSI.

Relative contributions of population exposure changes

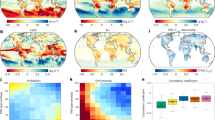

Globally, changes in rural population exposure to CDHWs were initially dominated by climate effects, with its contribution exceeding 80% before the 1970s. However, this dominance has declined steadily over time, dropping to ≈30% by the 2020s. From the 1970s to the 1980s, population effects and climate-population interaction effects began to play increasingly significant roles. By the late 20th century, climate-population interaction effects had become the dominant factor, with their contribution rising from 5% in the 1970s to 50% by 2021. Population effects alone contributed between 10% and 20% throughout the study period, showing relatively minor fluctuations (Fig. 8). For urban populations, the trends are highly consistent with those of rural populations, with some notable differences. Climate effects dominated urban exposure trends until the 1940s, after which climate-population interaction effects began to dominate, shifting earlier than in rural contexts. The contribution of urban population effects showed greater variability, fluctuating between 10% and 50%, and was the dominant factor during the 1960s and 1970s. This suggests that urban areas experienced more dynamic demographic shifts during these decades, likely driven by rapid urbanization and economic growth. The dominant factor for changes in rural population exposure was climate effects, while for urban populations, the climate-population interaction effects played a more significant role. The increasing influence of climate-population interactions effects the compounding effects of demographic shifts and climatic extremes, which have become the primary drivers of exposure in the mid- to late-20th century. These findings emphasize the need for integrated climate and population models to better understand and predict exposure trends, particularly as climate-population interactions continue to grow in significance.

Discussion

In this study, we employed two widely used drought indices, the SPEI and the scPDSI, to identify CDHWs. Our findings reveal a significant upward trend in global terrestrial CDHWs, accompanied by consistent spatiotemporal patterns. However, the occurrence of CDHWs identified using SPEI is notably higher than that identified using scPDSI, highlighting differences arising from the indices’ formulations and sensitivities to climatic variables. The SPEI incorporates both precipitation and potential evapotranspiration (PET), rendering it more responsive to temperature fluctuations, especially in warmer climates25. In contrast, the scPDSI emphasizes soil moisture dynamics, leading to a slower and more attenuated response to temperature-driven changes in evapotranspiration26. Consequently, events characterized by extreme heat are more readily identified by SPEI, particularly in arid and transitional regions (Supplementary Fig. 3). These differences underscore the importance of selecting appropriate indices for specific research objectives and climate regimes.

The temporal evolution of CDHWs aligns closely with global mean temperature trends over the past century. The occurrence of CDHWs increased significantly between 1901 and 1940, stabilized from 1941 to 1980, and rose sharply from 1981 to 2021. This pattern mirrors historical global temperature trajectories, reflecting the dominant role of temperature in driving CDHW occurrences26,27. The mid-century stabilization likely corresponds to aerosol-induced cooling, while the post-1980 surge aligns with accelerated greenhouse gas-induced warming28. These results reaffirm the critical role of anthropogenic warming in amplifying CEs and emphasize the urgency of implementing effective mitigation and adaptation strategies29.

Spatially, the regions with the highest historical occurrence of CDHWs include northern South America, southern and northern Africa, Central Asia, and CAU. These findings are consistent with previous studies30,31,32, reinforcing the role of arid and semi-arid zones as hotspots for CDHWs. However, the regions with the highest rates of CDHWs do not necessarily exhibit the highest levels of population exposure, which is also influenced by demographic distribution33,34. The most affected rural populations are concentrated in northern and southern India, as well as eastern and southern China, while urban populations most exposed to CDHWs are located in the eastern United States, European countries, and urban agglomerations in the Pearl River Delta and Yangtze River Delta in China35. These densely populated areas are particularly vulnerable to the cascading impacts of CDHWs, emphasizing the need for targeted disaster prevention and mitigation policies tailored to regional contexts.

Another noteworthy finding of this study is the shifting exposure of rural and urban populations to CDHWs over time. Starting in the 1970s, a clear increase in exposure to CDHWs began for both rural and urban populations, driven by the growing influence of population effects and climate–population interaction effects. Before the 1990s, rural populations experienced greater exposure to CDHWs. However, the rapid urbanization observed over the past three decades has led to a marked increase in urban exposure, which now surpasses that of rural populations. This transition is closely linked to the expansion of urban areas and population migration driven by global economic development. Furthermore, the primary drivers of population exposure have evolved. Climate effects were dominant before the 1980s, while the climate–population interaction effects has become increasingly significant in recent decades. These findings highlight the importance of integrating climate projections with demographic changes to improve future exposure assessments.

This study also tested the sensitivity of our results to threshold definitions for CDHWs. By applying alternative thresholds (20th percentile for drought indices and 80th percentile for temperature), we demonstrated that the spatial patterns and temporal trends of CDHWs remained robust (Supplementary Figs. 7–9). This robustness strengthens confidence in the conclusions and provides a solid foundation for developing evidence-based risk management strategies. However, it is critical to acknowledge that the impacts of CDHWs are not determined solely by exposure. Vulnerability and adaptive capacity are equally important factors that were not explicitly estimated in this study36,37. For instance, urban heat islands (UHIs) can amplify heatwave intensity, exacerbating risks for urban populations. While this study identified key urban areas affected by CDHWs, the direct effects of UHIs were not quantified37,38. Future studies should incorporate urban surface models and high-resolution climate projections to explicitly account for UHI effects and refine urban risk assessments

In addition to climatic drivers, socioeconomic factors, such as age structures, income levels, and access to healthcare or cooling infrastructure significantly influence vulnerability and resilience to CDHWs39, These factors were not explicitly analyzed but warrant attention in future research. Recent studies have highlighted that urban populations may benefit from stronger economies, better healthcare systems, and more resilient infrastructure, potentially offsetting some of the risks posed by CDHWs40,41,42. However, rural populations, particularly those reliant on agriculture, remain highly vulnerable due to their dual exposure to drought and heat, which directly threaten health and food security43. Given the critical role of rural populations in global food production, greater attention must be directed toward enhancing their resilience to climate change impacts.

This study advances the understanding of historical CDHW trends and their implications for global rural and urban populations by providing a high-resolution analysis of spatial and temporal patterns of exposure43. However, the findings also underscore the need for integrating vulnerability and adaptive capacity into future assessments to comprehensively evaluate CDHW risks44,45. Additionally, regions such as West Africa, Central Europe, South America, East Asia and South Asia, which experience significant impacts from CDHWs, merit further investigation with higher-resolution datasets46,47. Incorporating socioeconomic and infrastructural data will be essential for developing targeted adaptation strategies that address the needs of both rural and urban populations.

In conclusion, while this study provides critical insights into the spatiotemporal dynamics of CDHWs and their impacts on rural and urban populations, it also highlights key areas for future research. Addressing the limitations identified, such as the incorporation of UHI effects, vulnerability assessments, and socioeconomic factors, will be crucial for improving risk assessments and informing effective mitigation and adaptation strategies. These efforts are vital for enhancing resilience to the escalating risks posed by CDHWs in a rapidly changing climate.

Methods

Data

Climate data

This study used one-month SPEI and scPDSI data to identify drought events. SPEI data were obtained from the most recent version of the global SPEI database (SPEIbase v2.9), which was generated based on the Climate Research Unit Time Series version 4.07 (CRU TS-4.07) dataset and provides monthly values from 1901 to 2021. SPEI values are available on a time scale from 1901 to 202148. In addition, scPDSI data, also from the CRUTS-4.07, are available at a spatial resolution of 0.5° × 0.5°. The scPDSI is calculated on a monthly scale and uses dynamic computation of constants to automatically calibrate the exponential behavior at any location, making it widely used for drought event identification26,49. To ensure consistency in temperature data sources during HWs and droughts and to avoid CDHW errors from data inconsistencies, monthly temperature data from CRU TS-4.07 were selected for heat wave event identification. Furthermore, this study classified global regions into drought, transition, and humid zones based on the aridity index (AI)50. The AI was calculated as the ratio of mean annual PET (Ep) to precipitation (P) using data from CRU TS-4.07, effectively capturing the aridity and desertification characteristics of each region51. Using data for the 1981–2021 climatological period, a global zoning map delineating drought (AI > 2.25), transition (0.9 < AI ≤ 2.25), and humid (AI ≤ 0.9) areas was produced, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 10. All datasets in this study were obtained at a spatial resolution of 0.5° × 0.5° and a monthly temporal scale, avoiding errors associated with downscaling and ensuring the robustness of the results.

Population data

The rural and urban population data come from the third round of the Intersectoral Model Intercomparison Project, which provides yearly global population data from 1901 to 2021 at a spatial resolution of 0.5°. This data has been widely used in the study of the impact of climate change on humans because of its high data quality, precision, and extensive time series52,53.

Definition of CDHWs

The definition of CDHWs has generally been based on thresholds derived from drought index and temperature data54,55. In this study, because two drought indices (SPEI and scPDSI) were chosen, to avoid errors associated with the use of equal absolute thresholds, we defined the occurrences of CDHW as the monthly drought index falling below the 10th percentile calculated over the entire study period and the monthly temperature exceeding the 90th percentile calculated over the entire study period8,56,57. The 10th percentile of the drought indices and the 90th percentile of the temperature were calculated from the drought indices and temperature data for each grid during the extended summer season (May through October in the Northern Hemisphere and November through April in the southern hemisphere) for the entire study period (1901–2021). Next, a binary variable was generated to indicate whether a CDHW occurs (1 for occurrence, 0 for non-occurrence) when a drought event (\({D}_{i}\)) and a heatwave event (\({{HW}}_{i}\)) occur simultaneously, i.e., \(\left({{HW}}_{i}=1\,\cap \,{D}_{i}=1\right)\), as shown in Eq. 17. The annual occurrence (in months) of CDHWs per grid per period was calculated by accumulating the binary variables and dividing by the total number of years in the calculation period53.

Population exposure to CDHWs

The exposure of rural and urban population was defined as the product of the occurrence of CDHWs and the number of people exposed to CDHWs in each grid58,59. Population exposure to CDHWs was calculated on a year-by-year basis using the following equation:

Where \({E}_{{pop}}\) represents rural and urban population exposure (person-months), \({j}\) denotes the year, \({{CDHWs}}_{j}\) represents the annual number of CDHWs (month), \({POP}\) represents rural and urban population.

Relative contributions of population exposure changes

Exposure changes associated with climate, population, and their interactions (\(\triangle {E}_{{pop}}\)) are decomposed into three main components: climate effects, population effects, and interaction effects. This approach has been widely used in attribution analysis of changes in exposure to extreme climate events60,61. Thus, to assess the effects of climate change, demographic change, and climate-demographic interactions on the exposure of rural and urban populations, climate effects were detected by holding rural and urban populations constant at the baseline level (i.e., 1900s) but allowing CDHWs to vary over time. Population effects were detected by holding CDHWs constant at the baseline level (i.e., 1900s) but allowing population size to vary over time. The interaction effect, which represents simultaneous climate and population changes, is defined as the difference between the change in total exposure and the sum of the climate and population effects. To better estimate the contribution, we used the change in exposure from 1901–2020 by averaging the results for each decade. The calculations are as follows:

Where \({P}_{1}\) represents the population from 1901 to 1910 (1900s); and \({{CDHWs}}_{1}\) is the number of CDHWs from 1901 to 1910 (1900s); The terms \(\triangle P\) and \(\triangle {CDHWs}\) denote population change and the number of CDHWs occurrences, respectively. The contribution rate of each factor can be computed as follows:

where \({{CR}}_{{cli}}\) \({{CR}}_{{pop}}\) and represent the contribution rates of climate effects and population effects, respectively.\(\,{{CR}}_{\mathrm{int}}\) shows the contribution rate of climate-population interaction effects.

Statistical analysis

In this study, trends in CDHWs characteristics were calculated based on Kendall’s tau and the Sen slope estimator, while the statistical significance of the trends was tested using the Mann–Kendall trend test at a 95% confidence level62.

Data availability

The data supporting the results of this study are publicly available from the following sources: The rural and urban population data can be downloaded from the Inter-Sectoral Impact Model Intercomparison Project (https://data.isimip.org/10.48364/ISIMIP.822480.2). The SPEI data are available at https://digital.csic.es/handle/10261/332007. The scPDSI data can be accessed at https://crudata.uea.ac.uk/cru/data/drought/#global. Monthly temperature, precipitation and evapotranspiration data from CRU Ts-4.07 are available at https://crudata.uea.ac.uk/cru/data/hrg/cru_ts_4.07/cruts.2304141047.v4.07/.

Code availability

The codes used in this study are available on request from the corresponding author (baoam@ms.xjb.ac.cn).

References

Wang, X., Jiang, D. & Lang, X. Future extreme climate changes linked to global warming intensity. Sci. Bull. 62, 1673–1680 (2017).

Hoegh-Guldberg, O. et al. The human imperative of stabilizing global climate change at 1.5°C. Science. 365, eaaw6974 (2019).

Yin, J. et al. Future socio-ecosystem productivity threatened by compound drought–heatwave events. Nat. Sustain. 6, 259–272 (2023).

Zaitchik, B. F., Rodell, M., Biasutti, M. & Seneviratne, S. I. Wetting and drying trends under climate change. Nat. Water 1, 502–513 (2023).

Zscheischler, J. et al. A typology of compound weather and climate events. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 1, 333–347 (2020).

Mukherjee, S. & Mishra, A. K. Increase in compound drought and heatwaves in a warming world. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48, e2020GL090617 (2021).

Tripathy, K. P., Mukherjee, S., Mishra, A. K., Mann, M. E. & Williams, A. P. Climate change will accelerate the high-end risk of compound drought and heatwave events. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 120, e2219825120 (2023).

Li, W. et al. Anthropogenic impact on the severity of compound extreme high temperature and drought/rain events in China. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 6, 13–79 (2023).

Mukherjee, S., Mishra, A. K., Zscheischler, J. & Entekhabi, D. Interaction between dry and hot extremes at a global scale using a cascade modeling framework. Nat. Commun. 14, 277 (2023).

Fan, X., Miao, C., Wu, Y., Mishra, V. & Chai, Y. Comparative assessment of dry- and humid-heat extremes in a warming climate: frequency, intensity, and seasonal timing. Weather Clim. Extremes 45, 100698 (2024).

Hassan, W. U., Nayak, M. A. & Azam, M. F. Intensifying spatially compound heatwaves: global implications to crop production and human population. Sci. Total Environ. 932, 172914 (2024).

Hao, Z. et al. Compound droughts and hot extremes: characteristics, drivers, changes, and impacts. Earth-Sci. Rev. 235, 104241 (2022).

Vogel, M. M., Zscheischler, J., Fischer, E. M. & Seneviratne, S. I. Development of future heatwaves for different hazard thresholds. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 125, e2019JD032070 (2020).

Zhang, Y., Hao, Z., Zhang, X. & Hao, F. Anthropogenically forced increases in compound dry and hot events at the global and continental scales. Environ. Res. Lett. 17, 24018 (2022).

Feng, S., Hao, Z., Zhang, Y., Zhang, X. & Hao, F. Amplified future risk of compound droughts and hot events from a hydrological perspective. J. Hydrol. 617, 129143 (2023).

Wu, X., Hao, Z., Zhang, X., Li, C. & Hao, F. Evaluation of severity changes of compound dry and hot events in China based on a multivariate multi-index approach. J. Hydrol. 583, 124580 (2020).

Abella, D. J. & Ahn, K. Investigating the spatial and temporal characteristics of compound dry hazard occurrences across the pan-Asian region. Weather Clim. Extremes 44, 100669 (2024).

Zhang, Q. et al. High sensitivity of compound drought and heatwave events to global warming in the future. Earth’s Future 10, e2022EF002833 (2022).

Zhou, Y., Guo, Y. & Liu, Y. Health, income and poverty: evidence from China’s rural household survey. Int. J. Equity Health 19, 36 (2020).

Igawa, M. & Managi, S. Energy poverty and income inequality: an economic analysis of 37 countries. Appl. Energ. 306, 118076 (2022).

Libonati, R. et al. Drought–heatwave nexus in Brazil and related impacts on health and fires: a comprehensive review. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1517, 44–62 (2022).

Yao, P. et al. Assessment of the combined vulnerability to droughts and heatwaves in Shandong Province in summer from 2000 to 2018. Environ. Monit. Assess. 196, 464 (2024).

Ghanbari, M., Arabi, M., Georgescu, M. & Broadbent, A. M. The role of climate change and urban development on compound dry-hot extremes across USA cities. Nat. Commun. 14, 3509 (2023).

Zhang, K. et al. Increased heat risk in wet climate induced by urban humid heat. Nature 617, 738–742 (2023).

Beguería, S., Vicente-Serrano, S. M., Reig, F. & Latorre, B. Standardized precipitation evapotranspiration index (SPEI) revisited: parameter fitting, evapotranspiration models, tools, datasets and drought monitoring. Int. J. Climatol. 34, 3001–3023 (2014).

Wang, C. et al. Drought-heatwave compound events are stronger in drylands. Weather Clim. Extremes 42, 100632 (2023).

Wu, H., Su, X., Singh, V. P. & Zhang, T. Compound climate extremes over the globe during 1951–2021: changes in risk and driving factors. J. Hydrol. 627, 130387 (2023).

Bauer, S. E. et al. Historical (1850–2014) Aerosol evolution and role on climate forcing using the GISS ModelE2.1 contribution to CMIP6. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 12, e2019MS001978 (2020).

Zscheischler, J. & Lehner, F. Attributing compound events to anthropogenic climate change. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 103, E936–E953 (2022).

Tabari, H. & Willems, P. Global risk assessment of compound hot-dry events in the context of future climate change and socioeconomic factors. NPJ Clim. Atmos. Sci. 6, 10–74 (2023).

Ridder, N. N. et al. Global hotspots for the occurrence of compound events. Nat. Commun. 11, 5956 (2020).

Pan, R., Li, W., Wang, Q. & Ailiyaer, A. Detectable anthropogenic intensification of the summer compound hot and dry events over global land areas. Earth’s Future. 11, e2022EF003254 (2023).

Massaro, E. et al. Spatially-optimized urban greening for reduction of population exposure to land surface temperature extremes. Nat. Commun. 14, 5786 (2023).

Shi, X. et al. Impacts and socioeconomic exposures of global extreme precipitation events in 1.5 and 2.0 °C warmer climates. Sci. Total Environ. 766, 142665 (2021).

Tuholske, C. et al. Global urban population exposure to extreme heat. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 118, e2024792118 (2021).

Chen, M. et al. Rising vulnerability of compound risk inequality to ageing and extreme heatwave exposure in global cities. npj Urban Sustain. 3, 11–38 (2023).

Russo, S. et al. Half a degree and rapid socioeconomic development matter for heatwave risk. Nat. Commun. 10, 136 (2019).

He, K., Chen, X., Zhou, J., Zhao, D. & Yu, X. Compound successive dry-hot and wet extremes in China with global warming and urbanization. J. Hydrol. 636, 131332 (2024).

Gao, S. et al. Urbanization-induced warming amplifies population exposure to compound heatwaves but narrows exposure inequality between global North and South cities. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 7, 154 (2024).

Mazdiyasni, O. & AghaKouchak, A. Substantial increase in concurrent droughts and heatwaves in the United States. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 112, 11484–11489 (2015).

Feng, A. et al. Will the 2022 compound heatwave–drought extreme over the Yangtze river basin become grey Rhino in the future? Adv. Clim. Change Res. 15, 547–556 (2024).

Markonis, Y. et al. The rise of compound warm-season droughts in Europe. Sci. Adv. 7, eabb9668 (2021).

Zhao, Y., Zhong, L., Zhou, K., Liu, B. & Shu, W. Responses of the urban atmospheric thermal environment to two distinct heat waves and their changes with future urban expansion in a chinese megacity. Geophys. Res. Lett. 51, e2024GL109018 (2024).

Wang, A. et al. Global cropland exposure to extreme compound drought heatwave events under future climate change. Weather Clim. Extremes 40, 100559 (2023).

Li, E., Zhao, J., Pullens, J. W. M. & Yang, X. The compound effects of drought and high temperature stresses will be the main constraints on maize yield in Northeast China. Sci. Total Environ. 812, 152461 (2022).

Guardaro, M., Hondula, D. M., Ortiz, J. & Redman, C. L. Adaptive capacity to extreme urban heat: the dynamics of differing narratives. Clim. Risk Manag. 35, 100415 (2022).

Satterthwaite, D. et al. Building resilience to climate change in informal settlements. One Earth 2, 143–156 (2020).

Sun, C., Zhu, L., Liu, Y., Hao, Z. & Zhang, J. Changes in the drought condition over northern East Asia and the connections with extreme temperature and precipitation indices. Glob. Planet. Chang. 207, 103645 (2021).

Wells, N., Steve, G. & And, M. J. H. A self-calibrating palmer drought severity index. J. Clim. 17, 2335–2351 (2004).

Qing, Y., Wang, S., Ancell, B. C. & Yang, Z. Accelerating flash droughts induced by the joint influence of soil moisture depletion and atmospheric aridity. Nat. Commun. 13, 1139 (2022).

Greve, P., Roderick, M. L., Ukkola, A. M. & Wada, Y. The aridity Index under global warming. Environ. Res. Lett. 14, 124006 (2019).

Sreeparvathy, V. & Srinivas, V. V. Meteorological flash droughts risk projections based on CMIP6 climate change scenarios. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 5, 1–17 (2022).

Zhang, G. et al. Climate change determines future population exposure to summertime compound dry and hot events. Earth’s Future 10, e2022EF003015 (2022).

Hu, Y., Wang, W., Wang, P., Teuling, A. J. & Zhu, Y. Spatial-temporal variations and drivers of the compound dry-hot event in China. Atmos. Res. 299, 107160 (2024).

Bevacqua, E., Zappa, G., Lehner, F. & Zscheischler, J. Precipitation trends determine future occurrences of compound hot–dry events. Nat. Clim. Change 12, 350–355 (2022).

Wang, J. et al. Association of western USA compound hydrometeorological extremes with Madden–Julian oscillation and ENSO interaction. Commun. Earth Environ. 5, 314 (2024).

Zhou, M. & Wang, S. The risk of concurrent heatwaves and extreme sea levels along the global coastline is increasing. Commun. Earth Environ. 5, 144 (2024).

Ban, J., Lu, K., Wang, Q. & Li, T. Climate change will amplify the inequitable exposure to compound heatwave and ozone pollution. One Earth 5, 677–686 (2022).

Jones, B. et al. Future population exposure to USA heat extremes. Nat. Clim. Change 5, 652–655 (2015).

Chen, J. et al. Global socioeconomic exposure of heat extremes under climate change. J. Clean. Prod. 277, 123275 (2020).

Li, Y. et al. Sorely reducing emissions of non-methane short-lived climate forcers will worsen compound flood-heatwave extremes in the Northern Hemisphere. Adv. Clim. Change Res., 15, 737–750 (2024).

Ullah, I. et al. Future amplification of multivariate risk of compound drought and heatwave events on south asian population. Earth’s Future. 11, e2023EF003688 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This work is co-funded by the Key R&D Program of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region (Grant no. 2022B03021), the Tianshan Talent Training Program of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous region (Grant no. 2022TSYCLJ0011), the 2020 Qinghai Kunlun talents -Leading scientists project (Grant no. 2020-LCJ-02), and Key program of International Cooperation, Bureau of International Cooperation, Chinese Academy of Sciences (Grant no. 131551KYSB20210030) and T.L. was supported by a grant from the program of China Scholarship Council (ICPIT–International Cooperative Program for Innovative Talents, Grant No. 202310630003) during his study in Ghent University, Ghent, Belgium.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.L. and F.J.S. contributed to the conception of the study. T.L. and J.Y.B. analyzed and interpreted the data. T.L., F.J.S., A.D.C., and P.G. wrote the manuscript. A.D.C., A.M.B., L.T.H., P.D.M., and P.G. helped to edit the manuscript. L.T.H., P.G., Y.Y., A.M.B., and S.L.N.B. offered suggestions for revision. All authors reviewed and edited the manuscript before submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, T., Song, F., De Cock, A. et al. Global disparities in rural and urban population exposure to compound drought and heatwave events. npj Clim Atmos Sci 8, 207 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-01025-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-01025-9

This article is cited by

-

How do dental professionals perceive sustainable dentistry? A qualitative study

BMC Medical Education (2025)

-

Food security under climatic extremes in the Asia-Pacific region

npj Climate Action (2025)

-

Spatiotemporal evolution and driving mechanisms of compound dry and hot events in the Yellow River Basin under climate warming

Theoretical and Applied Climatology (2025)