Abstract

Marine heatwaves (MHWs) and tropical cyclones (TCs) are prominent extreme events in the Bay of Bengal (BoB), whose co-occurrence can amplify their impacts. This study explores the mechanisms behind compound MHW-TC events and their influence on the onset of the BoB summer monsoon (BoBSM). Our findings indicate that compound MHW-TC events initiate with increased downward shortwave radiation and Ekman downwelling during MHW formation, followed by latent heat flux release and Ekman upwelling during the TC lifecycle. The interaction between increased maximum potential intensity and steering flow during compound events results in a westward shift in TC tracks, delaying precipitation and atmospheric latent heat release in the eastern BoB. These factors, as well as the warmer sea surface temperatures in the BoB, hinder the reversal of the mid-to-upper tropospheric meridional temperature gradient, ultimately postponing BoBSM onset. These insights enhance the understanding of MHW-TC interactions and their implications for predicting BoBSM onset.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Marine heatwaves (MHWs) are prolonged periods of extreme warm water events lasting five days or more and spanning spatial scales ranging from hundreds to thousands of kilometers1. These events have substantial and enduring effects on marine habitats, species, fisheries, and aquaculture ecosystems2,3,4. The underlying mechanisms of numerous record-breaking MHW events have been documented globally4; these events vary considerably across different regions and are influenced by local air-sea internal variability, including wind stress5, heat fluxes6, ocean stratification7, and turbulent mixing8, as well as large-scale ocean climate modes such as El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO)9, Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO)10, and Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD)11,12. Furthermore, the global annual MHW days increased by approximately 54% from 1925 to 2016, and this trend is projected to persist in a warmer future climate13.

As global warming intensifies, extreme events such as floods, heatwaves, and droughts increasingly compound across multiple spatiotemporal scales14,15. When such extreme events occur concurrently or in succession, their combined effects can lead to far more severe consequences than individual events alone14. In particular, MHWs frequently interact with other extreme marine events, including low-chlorophyll extreme events16, leading to anomalously low net primary production events17, ocean acidification extreme events2, low sea surface salinity extreme events18, and low-oxygen extreme events19. These compound events not only amplify their individual impacts but also exacerbate oceanic environmental stress20. Moreover, MHWs are also associated with extreme atmospheric events, such as atmospheric heatwaves21 and tropical cyclones (TCs7). For example, Tropical Storm Gordon’s strong mixing weakened ocean stratification in the northern Gulf of Mexico by redistributing thermal properties vertically, and when combined with subsequent atmospheric heating due to an atmospheric heatwave, they triggered a MHW that directly contributed to the rapid intensification of Hurricane Michael, which later made devastating landfall as an extreme hurricane7.

Previous studies have shown that MHWs and TCs can either co-occur or follow each other, leading to complex compound events. Mawren et al.22 reported that pre-existing MHWs along the southeastern coast of Africa enhanced ocean heat content, contributing to the intensification of TCs as they passed through these regions, but the TCs subsequently suppressed or terminated the MHWs due to increased surface wind friction velocity, intense heat loss to the atmosphere, and entrainment-driven cooling. Choi et al.23 revealed that TCs associated with MHWs in the western North Pacific and Atlantic Oceans are significantly more intense and produce more precipitation than their non-MHW counterparts, driven by heightened latent heat release from high oceanic heat content and stronger wind speeds during the different phases of TC development. Pun et al.24 also reported that in the East China Sea in 2020, MHW-induced warm ocean conditions, combined with shallow water depth and strong salinity stratification, reduced the cooling effect on Typhoon Bavi, allowing it to become the strongest typhoon recorded in this region.

The Bay of Bengal (BoB) is a crucial part of the Indo-Pacific warm pool in boreal spring and plays a pivotal role in the Asian summer monsoon system25. Owing to its unique geographical location, the summer monsoon over the BoB (hereafter referred to as BoBSM) marks the initial phase of the broader Asian summer monsoon onset process. This process begins over the southeastern BoB, advances to the South China Sea summer monsoon, and ultimately culminates with the onset over India26,27,28. The BoB warm pool significantly influences the timing of the BoBSM, making it a vital region for understanding the evolution and dynamics of the Asian summer monsoon system29,30. Over the past two decades, the frequency of MHWs in the BoB has increased significantly, with their intensity peaking during the pre-monsoon (April-May) and post-monsoon (October-November) periods31,32. Similarly, TCs in the BoB follow a bimodal seasonal pattern, with peak activity also occurring during these pre- and post-monsoon seasons33,34,35,36. More TCs occur in October-November due to higher relative humidity, whereas super TCs are more frequent in April-May, driven by high ocean heat content and strong northward-propagating intraseasonal oscillation34. The temporal overlap between peak MHW and TC intensities in the pre-monsoon period, particularly in April-May, suggests potential interactions between these phenomena. Extreme MHWs, which often precede the BoBSM37, can significantly intensify TCs through their “supercharger” effect24,38. These TCs, similar to spring monsoon onset vortices39,40,41,42, move northward and merge with the Indo-Burma trough, splitting the subtropical high ridgeline and triggering the BoBSM onset43,44. Both observational data29,30,45 and model simulations46 have confirmed this process, highlighting the dynamical link between TCs and the BoBSM onset. Consequently, extreme MHWs and super TCs in the BoB may compound during the pre-monsoon period, potentially affecting the timing of the BoBSM onset. However, the specific mechanisms through which compound MHW-TC events impact the BoBSM onset remain unclear and warrant further investigation.

Recent studies have examined various compound MHW-TC events in the BoB. For example, Rathore et al.38 demonstrated that an MHW enhanced the upper ocean stratification and subsurface warming, leading to the rapid intensification of Super TC Amphan in 2022. However, much of the existing research has focused on individual compound MHW-TC events, without comprehensively examining the common physical mechanisms and broader climate impacts of such compound events. Although the BoB warm pool during spring is recognized for facilitating TC genesis and promoting the BoBSM onset43, the role of MHWs operating on shorter timescales during this onset process has not been well investigated. As a result, the influence mechanism of compound MHW-TC events on the timing of the BoBSM onset remains unclear. To address these gaps, this study analyzes the observational data from 1982 to 2022 to characterize compound MHW-TC events in the BoB prior to the BoBSM onset. Our objective is to explore the underlying physical mechanisms and improve understanding of how these events impact the timing of the BoBSM onset through air-sea interactions.

Results

Characteristics of compound MHW-TC events in the BoB

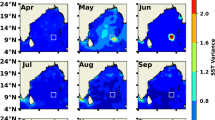

Climatologically, during late spring (April-May, AM), the highest frequency of MHWs in the BoB is predominantly observed in the central-western BoB, with the maximum frequency exceeding 0.55 events per year, while the eastern BoB exhibits significantly lower MHW frequency (Fig. 1a). In contrast, the mean intensity of MHWs is concentrated in the central-eastern region of the BoB, with a maximum mean intensity surpassing +1.6 °C (Fig. 1b). Hence, we focus on the study region (8-23°N, 84-92°E), which is marked by black boxes in Fig. 1a, b and experiences high MHW frequency and intensity. We identify fifteen MHW events in this region during the AM from 1982 to 2022 (see Supplementary Table 1), with approximately 67% occurring after 2000, indicating a significant decadal increase. This rising trend is likely driven by global warming, which has led to higher SST, significantly increasing both MHW frequency and TC intensity in the BoB37,47,48. These changes have created increasingly favorable conditions for their co-occurrence. Among these events, nine are compound MHW-TC events, where MHWs occurred first, with TCs forming during or shortly after the peak of MHWs.

Panels show BoB MHWs for (a) frequency (unit: times) and (b) mean intensity (unit: °C) during the AM of 1982-2022. The black rectangle represents the defined study region (8-23°N, 84-92°E) in the central-western BoB. Composite daily SSTAs (unit: °C) during (c) compound MHW-TC events and (d) MHW events without TCs (non-TC events) for the entire MHW duration, defined as the MHW period from onset to end. Composite daily SSTAs (unit: °C) during (e) compound MHW-TC events and (f) TC events without MHW (non-MHW events) for the entire TC lifetime, defined as the period from the formation to the dissipation of the TC. The blue contours indicate the MHW coverage areas where the SSTAs exceed the 90th percentile threshold of the daily SSTAs, and the white oblique lines represent the SSTAs above the 0.05 significance level based on the bootstrap hypothesis testing.

A comparative analysis of sea surface temperature (SST) anomalies (SSTAs) in the BoB for compound MHW-TC events (Fig. 1c) and individual MHW events without TCs (referred to as non-TC events, Fig. 1d) is conducted to highlight the distinct characteristics that distinguish compound events from individual MHWs. During the MHW duration, the compound MHW-TC events present significantly warmer SSTs throughout the entire BoB than during the non-TC events. The peak SSTAs in the eastern BoB during the compound MHW-TC events exceed +1.2 °C. Moreover, compound events display a broader spatial extent, with the MHWs extending westward all the way to 82°E (marked by the blue bold contours in Fig. 1c), whereas non-TC events remain confined to the central BoB (Fig. 1d). We also compare the BoB SSTAs during the TC lifetime for compound MHW-TC events (Fig. 1e) and individual TC events without MHWs (referred to as non-MHW events; Fig. 1f). In compound MHW-TC events, MHWs contract to the northeastern coastal BoB due to the cooling effects of TCs (Fig. 1e), in contrast to the wider spatial coverage observed during the MHW lifetime (Fig. 1c). Despite a significant reduction in the extent of positive SSTAs west of 90°E during the TC lifetime, positive SSTAs persist across the BoB (Fig. 1e). In contrast, non-MHW events show significantly negative SSTAs during the TC lifetime (Fig. 1f). This striking difference indicates that MHWs are associated with warmer SSTAs across the BoB during the TC lifetime, reinforcing the distinct dynamics and impacts of compound MHW-TC events. In addition, the comparison of upper ocean heat content (UOHC) anomalies among compound MHW-TC events, non-MHW events, and non-TC events reveals a striking contrast, consistent with the SSTAs patterns (Fig. 1c–f). Notably, compound MHW-TC events exhibit elevated UOHC in the western BoB compared to the individual events, indicating deeper heat storage during these compound events.

Underlying mechanisms of compound MHW-TC events in the BoB

To gain a deeper understanding of the interaction between MHWs and TCs, we conduct composite daily lag-lead analyses for the identified compound MHW-TC events averaged within the study region (8-23°N, 84-92°E as black boxes in Fig. 1; Fig. 2). A similar composite analysis for the mixed-layer heat budget and its individual terms is also carried out. Figure 2a shows that the SST increases before the formation of a TC and peaks at +30.7 °C five days before the peak of the TC (henceforth referred to as Day -5). This SST increase is critically associated with the occurrence of MHWs 15 days prior to the peak TC intensity (that is, Day -15). The mixed layer depth (MLD) anomaly reaches its shallowest value of -6.4 m on Day -5 in conjunction with the peak of the SST (Fig. 2b). Meanwhile, the UOHC anomaly peaks at 7.51 kJ/cm² on Day -10 (Fig. 2a), and the 26 °C isotherm depth (D26) anomaly reaches its deepest value of +0.95 m on the same day (figure not shown). The deepened thermocline and shallower MLD enhance ocean stratification, reducing vertical mixing, promoting surface heat accumulation, and sustaining high SST. The phase on Day -5 is also characterized by anomalously high mean sea level pressure and lower-than-normal wind speeds (figure not shown). However, starting on Day -5, the strong winds associated with the TC intensify mixing, thereby rapidly deepening the MLD and bringing colder water from deeper layers to the surface. This process leads to a sharp SST decline, a reduction in UOHC, and the dissipation of the MHW. By five days after the TC peak (that is, Day 5), the TC dissipates, and the SST begins to stabilize (Fig. 2a).

The horizontal axis spans from Day -30 to Day 20 relative to the peak TC intensity, with Day 0 marking the time for the peak TC intensity. The light yellow and blue shading represent the MHW and TC phases, respectively. a Composite SST (black solid curve; left column; unit: °C pentad−1) and UOHC anomalies (purple dashed curve; right column; unit: kJ cm−²). The blue solid curve represents the SST climatology, the green solid curve represents the 90th percentile threshold for MHW, and the red-filled area highlights the period associated with the identified MHW. b MLD anomalies (gray dashed curve; right column; unit: m) and mixed-layer temperature heat budget terms (unit: °C pentad−1), with yellow bars representing the mixed-layer temperature tendency (Tend). The blue, red, purple, and green solid curves denote the net surface heat flux term (Qnet) and the individual zonal advection (ZA), meridional advection (MA), and vertical advection (VA) terms, respectively. c Qnet and four anomalous heat flux terms (unit: °C pentad−1), including the net downward shortwave radiation (SWR), net upward longwave radiation (LWR), sensible heat flux (SHF), and latent heat flux (LHF). d VA and its related three anomalous terms (unit: °C pentad−1; see the Methods section for more details).

Based on the aforementioned observed changes in the SST and MLD, we divide the compound MHW-TC events into two phases: (i) the MHW phase (Day -15 to Day -5, which captures the development and intensification of MHWs), and (ii) the TC phase (Day -5 to Day 5), when the TC forms on Day -5, peaks in intensity on Day 0, and dissipates by Day 5. The mixed-layer heat budget analysis reveals that both the net surface heat flux (Qnet) and vertical advection (VA) terms are critical in determining the mixed-layer temperature tendency (Tend) during compound MHW-TC events (Fig. 2b). Their impacts vary significantly between the MHW and TC phases, whereas the zonal and meridional advection terms have relatively minor effects on mixed-layer temperature changes.

During the MHW phase, the positive Qnet term apparently plays a major role in warming the SST (Fig. 2b), largely driven by an increase in downward shortwave radiation (SWR; Fig. 2c). The positive VA term is mostly associated with the vertical advection of the mean temperature by the anomalous velocity (VAdva; Fig. 2d), which also contributes to SST warming, although its effect is roughly half that of Qnet (Fig. 2b). Specifically, the western North Pacific subtropical high (WNPSH) extends farther west than usual, inducing an anomalous low-level anticyclonic circulation over the BoB. This circulation suppresses local convection and decreases the total cloud cover (Supplementary Fig. 1a), resulting in a substantial positive SWR anomaly (Fig. 2c and Supplementary Fig. 1d). The increase in SWR enhances the positive Qnet into the ocean (Supplementary Fig. 1c). Furthermore, the enhanced SWR strengthens surface ocean heating and stratification, leading to a shallower mixed layer in the BoB (Fig. 2a, b). In addition, the large-scale anticyclonic circulation induces surface water convergence through Ekman transport in the central-western BoB, causing anomalous downwelling. This downwelling produces a significant positive VAdva (Supplementary Fig. 1e), which facilitates heat transport to deeper layers, deepening the thermocline and increasing UOHC. This process not only elevates SST but also stores heat in the subsurface, strengthening the ocean’s heat reservoir for subsequent TC development. The combined effects of radiative heating and downwelling processes contribute to a positive Tend in the BoB (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Fig. 1b).

During the TC phase, on the other hand, Tend is actually negative, reaching −0.22 °C/pentad on Day 0. The primary driver of this negative Tend is the negative Qnet (Fig. 2b), which can be largely attributed to the negative latent heat flux (LHF; Fig. 2c). This suggests heat loss from the ocean to the atmosphere. The negative VA terms, particularly the component related to VAdva (Fig. 2d), also play a significant role by contributing approximately one-third of the magnitude of Qnet (Fig. 2b). This combined cooling effect due to the Qnet and VA terms leads to a sharp decline in the SST and UOHC during the TC phase, as shown in Fig. 2a. Specifically, a cyclonic circulation develops in the western BoB, generating strong southwesterly winds that force the WNPSH to retreat from the central BoB to the eastern BoB (Supplementary Fig. 2a). This cyclonic circulation induces significant low-level convergence, promoting strong upward motion. Concurrently, intensified wind speeds increase sea surface evaporation, injecting more water vapor into the atmosphere49,50. As this water vapor condenses in robust updrafts, latent heat is released, contributing to a negative LHF in the BoB (Fig. 2c and Supplementary Fig. 2d) and increasing the total cloud cover (Supplementary Fig. 2a). In addition, the “wind-pumping” effect associated with TCs induces surface water divergence in the central BoB. This divergence drives Ekman upwelling51,52,53, resulting in a significant negative VAdva (Supplementary Fig. 2e). Hence, these processes cool the surface ocean and contribute to the negative Tend observed in the central BoB (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Fig. 2b).

Effects of compound MHW-TC events on TC activity over the BoB

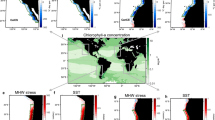

Compound MHW-TC events are usually associated with warmer SSTs and UOHC in the BoB during the TC phase (Fig. 1e). To further investigate how these compound events affect TC activity, we analyze TC tracks for both compound MHW-TC events and non-MHW events from 1982 to 2022. In compound MHW-TC events, TC tracks tend to shift westward, with a median longitude of approximately 86.8°E (Fig. 3a), compared with non-MHW events, which cluster at approximately 89.4°E in the central-eastern BoB (Fig. 3b). The westward displacement in longitude is statistically significant, as determined by both the two-tailed Welch’s t-test and the bootstrap hypothesis testing. In addition, compound events are associated with stronger TCs, with a median TC intensity of 45 knots, compared to 36 knots for non-MHW events. In these events, TCs follow a more westward trajectory and spend more time passing through ocean regions influenced by MHWs, which are characterized by warmer SSTs, increased UOHC, and a deeper mixed-layer depth (Fig. 2a, b). These favorable oceanic conditions supply additional thermal energy, further enhancing TC development and intensification, consistent with the finding of Wu et al.54. Moreover, the broader westward extension of warm SSTs and the westward concentration of elevated UOHC in the western BoB create a favorable environment that guides TCs to move westward during MHW phase. As a result, compound MHW-TC events are more likely to generate stronger TCs with westward-shifted tracks.

BoB TC tracks for (a) compound MHW-TC events and (b) non-MHW events during the AM of 1982-2022. Different categories of TCs are indicated by lines with color-filled circles along each track, and the respective years of each TC (listed in Supplementary Table 1) are marked by numbers along the tracks. The green and red boxplots show the maximum westward longitudinal positions of the TC tracks and the average intensity (unit: kts) of the TCs, respectively. c Differences in large-scale steering flows (vectors; unit: m s−1) with the pressure-weighted mean flow from 850 to 300 hPa and composite daily SSTAs (shading; unit: °C) during the AM, contrasting compound MHW-TC and non-MHW events. The blue contour denotes the coverage area of MHWs. The green and red contours indicate the WNPSH location on the basis of climatology and compound event conditions, respectively. The purple vectors highlight statistically significant zonal or meridional steering flow components at the 0.05 significance level, while the white oblique lines represent the SSTAs exceeding the 0.05 significance level, as determined by bootstrap hypothesis testing.

To further investigate the air-sea interactions in these compound events, Fig. 3c displays the differences in large-scale steering flows during the AM, using the mass-weighted mean flow from 850 hPa to 300 hPa. A comparison between compound MHW-TC events and non-MHW events reveals anomalous cyclonic circulation over the South Asian subcontinent and western BoB (Fig. 3c), indicating that during compound events, TC tracks tend to shift further west. The associated low-pressure system favors the westward movement of TCs. An anomalous anticyclone over the South China Sea and Indo-China Peninsula during compound MHW-TC events reflects a stronger WNPSH, which extends westward up to 90°E, than the climatological mean (Fig. 3c). The circulation on the southwestern flank of this westward-extending WNPSH acts as a persistent steering flow, guiding TCs along its periphery and contributing to the observed westward shift in TC tracks over the BoB. Further analysis of the lower-level atmospheric circulation (figure not shown) confirms that this westward extension of the WNPSH is the primary driver of the TC track shift, as it adjusts the steering flow and directly influences TC trajectories. Moreover, during the early stages of compound MHW-TC events, MHWs enhance upper ocean stratification and subsurface warming in the BoB, increasing the TC heat potential38. This process intensifies TCs (Fig. 3a), highlighting the vital role of MHWs in TC intensification.

During compound MHW-TC events, the strong WNPSH profoundly influences both atmospheric and oceanic conditions through a positive feedback mechanism. Initially, the enhanced WNPSH intensifies the Qnet over the BoB by reducing cloud cover (Supplementary Fig. 1a) and enhancing downward SWR (Supplementary Fig. 1d). The negative total cloud cover anomalies allow greater solar radiation penetration, further intensifying the downward SWR, which in turn raises the SST and triggers the MHWs development (Fig. 3c). The resulting warming in the northern IO, particularly in the BoB, further bolsters the WNPSH through large-scale atmospheric circulation changes55. This positive feedback contributes to the westward steering of TCs in the BoB (Fig. 3a).

In addition to the westward shift in TC tracks, TC genesis frequently occurs in the central-western BoB during compound MHW-TC events. To investigate the influence of large-scale environmental variables on TC genesis, we analyze the Genesis Potential Index (GPI)56 over the BoB and compare compound MHW-TC events with non-MHW events (Fig. 4). The GPI exhibits significant positive anomalies in the western BoB and negative anomalies in the eastern BoB (Fig. 4a). This distinct west-east contrast strongly favors TC genesis in the western BoB, directly supporting the observed westward shift in TC tracks during compound events. Among the GPI components, the maximum potential intensity (\({V}_{{pot}}\)) shows the most pronounced positive anomalies across the central and western BoB (Fig. 4b), indicating its dominant role in enhancing TC genesis potential. However, within the study region (8-23°N, 84–92°E), the spatial patterns of absolute vorticity (η) at 850 hPa, vertical wind shear (Vshear) between 200 hPa and 850 hPa, relative humidity (Rhum) at 700 hPa, and vertical pressure velocity (ω) at 500 hPa show weaker and less significant effects compared to \({V}_{{pot}}\) (Fig. 4c–f). Notably, η, Rhum, and ω exhibit negative anomalies in the eastern BoB (Fig. 4c, e, f), suggesting the presence of an anticyclonic circulation that may be associated with a strengthened WNPSH. This intensification of the WNPSH is likely contributed to the westward shift in TC tracks by modifying the steering flow and directing TCs toward the western BoB.

Spatial patterns of differences in (a) GPI, (b) Maximum potential intensity (\({V}_{{pot}}\)), (c) Absolute vorticity (η), (d) Vertical wind shear (\({V}_{{shear}}\)), (e) Relative humidity (Rhum), and (f) Vertical pressure velocity (ω). White oblique lines indicate areas where the differences are statistically significant at the 0.05 level based on the bootstrap hypothesis testing. g Differences in contributions from the total GPI term (purple left axis) and its associated components (black right axis), along with contributions from three anomalous \({V}_{{pot}}\) terms (black right axis), averaged over the defined study region (8-23°N, 84-92°E). White asterisks in the bars indicate signals exceeding the 0.05 significance level.

To further quantify the contributions of each component, we examine the regional mean differences in GPI and its components over the study region. The GPI differences show a significant positive anomaly, indicating favorable large-scale environmental conditions for TC genesis during the compound MHW-TC events. Among the GPI components, \({V}_{{pot}}\) term is the largest positive contributor. Other variables, including the \({V}_{{shear}}\) and ω also contribute positively, whereas η and Rhum contribute negatively. However, these four terms have relatively weaker effects on the GPI (Fig. 4g), which is consistent with the spatial distributions observed in Fig. 4a–f. Further analysis reveals that the \({V}_{{pot}}\) term is driven primarily by the SST, which is the most significant factor (Fig. 4g). This result is consistent with those of previous study57, suggesting that variations in maximum potential intensity are closely tied to SST perturbations. The exceptionally warm SST in the target region, associated with MHWs, significantly increases \({V}_{{pot}}\), increasing the likelihood of TC genesis and supporting the intensification of TCs in this region.

Delayed BoBSM onset due to compound MHW-TC events

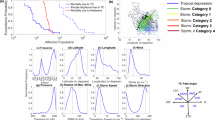

Compound MHW-TC events frequently occur just before the onset of the BoBSM, with the exception of 2017 (see Supplementary Table 1). To assess their impact on the BoBSM, we conduct a detailed analysis of the BoBSM onset dates during the study period. Figure 5a compares the onset dates of the BoBSM among the climatological events, non-MHW events, and compound MHW-TC events. For both climatological and non-MHW events, the BoBSM typically begins around pentad 26. However, during compound MHW-TC events, the onset is delayed until pentad 28 (Fig. 5a), with two pentads later than the climatological average. We further analyze the contributions of these three key factors to the BoBSM onset timing during compound MHW-TC events (Fig. 5b). In the BoBSM region (5-15°N, 85-100°E), an increase in precipitation occurs first, followed by a reversal in the wind direction, and finally, the MTG satisfies the criteria. This sequence suggests that the delayed transition of the MTG is the primary factor responsible for postponing the BoBSM onset during compound MHW-TC events.

a Boxplots showing the BoB summer monsoon (BoBSM) onset dates (unit: pentad). The purple, orange, and blue boxplots represent the onset dates in climatology, non-MHW events, and compound MHW-TC events, respectively. b Boxplots showing three criteria for the BoBSM onset dates for compound MHW-TC events. The gray, green, and red boxplots represent the 10 m wind direction, precipitation, and MTG indices, respectively. c-f Pentad composite evolution of the 700 hPa wind (streamline; unit: m s−1) and precipitation (shading; unit: mm d−1) anomalies from pentads 25–28 for compound MHW-TC events. The purple wind vectors and white oblique lines indicate signals that are statistically significant at the 0.1 level, as determined by bootstrap hypothesis testing. The blue dashed line represents the subtropical high ridgeline at 700 hPa, and the red contours represent the positive MTG, signifying a south-low-north-high pattern. The black rectangle highlights the key region (5-15°N, 85-100°E) for BoBSM onset. The black solid circles indicate the westernmost locations of each TC in the compound MHW-TC events.

During compound MHW-TC events in pentad 25, a weak low-level anticyclonic circulation anomaly is evident over the Indochina Peninsula, which suppresses local convection and leads to negative precipitation anomalies in this region (Fig. 5c). By pentad 26, the strengthening of the WNPSH further enhances the anticyclonic circulation anomaly over the Indochina Peninsula, leading to a continued reduction in precipitation (Fig. 5d). The Hovmöller diagram of MTG anomalies confirms that during pentads 25-26, negative MTG anomalies dominate the entire region (60°E-130°E; see Supplementary Fig. 3), indicating unfavorable conditions for monsoon onset. Furthermore, positive precipitation anomalies from the equatorial region migrate northward, extending into the western BoB (Fig. 5d). By pentad 27, the anticyclonic circulation anomaly intensifies and extends westward to approximately 80°E, exacerbating negative precipitation anomalies over the eastern BoB (Fig. 5e). Simultaneously, an anomalous cyclonic circulation develops south of the Indian Peninsula, producing pronounced positive precipitation anomalies in the equatorial and western BoB. During this stage, TCs begin to form, and their associated intense upward motion enhances precipitation. The increase in precipitation releases substantial latent heat, which further intensifies the upward motion, extending this motion to the tropopause and increasing atmospheric temperatures58,59. These processes cause large-scale positive mid-to-upper tropospheric MTG values, which are initially concentrated south of the Indian Peninsula (Fig. 5e). Moreover, this pattern is closely linked to the westward movement of TCs during these compound events. As the TCs mature in pentad 28, the weakened anticyclonic circulation anomaly retreats eastward, and the strengthening of the TC results in substantial precipitation across the BoB region. The latent heat released from this precipitation increases the atmospheric temperature, leading to largely positive MTG values spreading from west to east across the BoBSM region. This shift from negative to positive MTG in the BoBSM region signals the onset of monsoon-favorable conditions (Supplementary Fig. 3). Furthermore, the northward movement of the TC into the Indo-Burma trough in the northern BoB led to the splitting of the subtropical high ridgeline43. This process marks the onset of the BoBSM at approximately pentad 28 (Fig. 5f).

In non-MHW events, BoBSM onset occurs at approximately pentad 26 (see Supplementary Fig. 4). The eastward TC tracks cause a low-level cyclonic circulation and low-pressure trough over the eastern BoB, increasing atmospheric convection and precipitation as well as latent heat release. Convection inverts the mid-to-upper tropospheric MTG from negative to positive, causing the subtropical high ridgeline to split by pentad 26, thus triggering the BoBSM onset (Supplementary Fig. 4b). In pentads 27-28, the complete splitting of the subtropical high ridgeline and MTG inversion signify the full onset of BoBSM (Supplementary Fig. 4c, d).

During compound MHW-TC events, the SSTAs in the northern Indian Ocean are significantly greater than those during non-MHW events, indicating an overall increase in SST across the entire BoB (Supplementary Fig. 5). The elevated SSTs related to MHWs increase tropospheric temperatures, stabilizing the south-high-north-low-temperature configuration and delaying its reversal60. Only when the TC matures by pentad 28 (Fig. 5f), with substantial precipitation and latent heat release, do conditions favor large-scale MTG reversal over the BoBSM region, resulting in a delayed BoBSM onset compared with non-MHW events.

Conclusions and discussion

MHWs and TCs can significantly impact marine ecosystems, weather and climate changes, and human activities. However, understanding the dynamics of these compound extreme events remains challenging. Moreover, the combined effects of compound MHW-TC events on the onset of monsoons in the BoB have yet to be explored. This study defines compound MHW-TC events as cases in which TCs occur concurrently with or immediately following MHWs in a few days. We investigate the spatiotemporal variations in these compound events in the BoB during the AM from 1982–2022 and elucidate their potential interactions and influences on the onset of the BoBSM.

During the MHW phase, an anomalous low-level anticyclonic circulation over the western BoB, caused by the westward extension of the WNPSH, increases the net downward shortwave radiation over the BoB by reducing the total cloud cover. This anomalous low-level anticyclone also induces Ekman transport convergence and enhances Ekman downwelling in the central-western BoB. As a result, the combined effects of enhanced downward shortwave radiation and positive advection of the mean temperature by the vertical advection, driven by the low-level anticyclonic circulation, play a fundamental role in warming the mixed-layer ocean temperature of the BoB (Fig. 6a). This process not only increases SST but also facilitates vertical heat redistribution, significantly enhancing UOHC and creating a reservoir of thermal energy in the subsurface ocean. In contrast, during the TC phase, an anomalous low-level cyclonic circulation over the western BoB, along with a slight eastward retreat of the WNPSH, leads to a decrease in mixed-layer ocean temperature and UOHC. This cooling is primarily due to the sharp release of latent heat flux caused by the intensified wind speed and the negative ocean vertical advection associated with TCs within the central-western BoB, where the MLD is deeper than the climatological value (Fig. 6b).

Our findings also reveal that compound MHW events in the BoB during the spring season result in a westward shift in the co-occurring (or immediately following) TC tracks (Figs. 3a and 6b) and, critically, strengthen these TCs (Fig. 3a, b). This westward shift is associated with the anomalous cyclonic circulation of the steering flow driven by the westward-extended WNPSH. MHWs bolster the WNPSH through large-scale atmospheric circulation modulations. They also amplify the maximum potential intensity in the defined study region, supporting the genesis and persistence of TCs in the BoB. As a result, the combined influence of the robust WNPSH and MHWs leads to westward TC tracks and increased TC intensities during compound MHW-TC events.

Typically, the onset of TCs results in significant precipitation and latent heat release, which fosters atmospheric convection and initiates the reversal of the MTG, thereby marking the onset of the summer monsoon in the eastern BoB. However, during compound MHW-TC events, the westward trajectory of TCs and the strengthening of the WNPSH induce negative precipitation anomalies in the BoBSM region and positive anomalies in the western BoB. This causes the MTG reversal to start in the west and gradually spread to the BoBSM region, leading to a delay in BoBSM onset. Moreover, the elevated SSTs associated with MHWs increase the tropospheric temperatures over the BoB, stabilizing the MTG and making it less prone to reversal. In pentad 28, as the TC matures and causes widespread precipitation, significant latent heat release facilitates broad MTG reversal, leading to the splitting of the subtropical high ridgeline and the late onset of the BoBSM (Fig. 6c).

This study highlights the interactions and mechanisms of compound MHW-TC events and their impact on delaying the onset of BoBSM. However, the onset of the BoBSM is usually influenced by several factors, including the annual SST cycle61, thermal effects from the Tibetan Plateau27,62, decadal-scale variability such as the PDO63,64, interannual-scale SST variations linked to the ENSO, IOD, and Indian Ocean Basin Mode (IOBM)65,66,67,68, as well as intraseasonal oscillations69,70. While previous studies have examined the individual impacts of these factors on BoBSM onset, our analysis reveals that compound MHW-TC events occur across diverse climate mode states, with no single mode driving these events. Consequently, the comprehensive effects of MHW and TC, particularly in compound MHW-TC events, remain less understood. Our findings, derived from observational data, underscore the necessity for further research employing high-resolution numerical simulations, which are crucial for validating the identified mechanisms and investigating the wider implications of these compound events.

Numerous compound events have been documented globally in recent years15. These events, where multiple extreme oceanic and climatic phenomena occur simultaneously, present a greater threat to marine ecosystems than individual extreme events do2,7,8,15,16,17. The increasing frequency and severity of such compound events underscore the urgent need for focused and comprehensive scientific research. A deeper understanding of their interactions and underlying mechanisms is critical for improving predictions and mitigating the extreme impacts they cause. This study provides a detailed assessment of compound MHW-TC events, emphasizing their significant role in delaying BoBSM onset. Such assessments are essential for enhancing predictive capabilities and developing effective strategies to protect the marine environment from the compounded risks of multiple extreme events.

Methods

Atmospheric and oceanic datasets

Daily SST data are obtained from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Optimum Interpolation Sea Surface Temperature (OISST; Version 2) product, which is characterized by a horizontal resolution of 0.25° × 0.25°71. Daily atmospheric reanalysis products are sourced from the National Centers for Environmental Prediction-Department of Energy Reanalysis 2 (NCEP-DOE R2). The surface variables are represented on a global T62 Gaussian grid, while the isobaric variables at 17 standard pressure levels from 1000 to 10 hPa are available at a horizontal resolution of 2.5° × 2.5°72. Pentad subsurface ocean data are provided by the NCEP Global Ocean Data Assimilation System (GODAS), featuring a horizontal resolution of 1/3° latitude × 1° longitude and encompassing 40 vertical levels ranging from 5 to 4478 m73. The International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS) data, with a temporal interval of 6 h, serve as the observational reference for tropical cyclones74. All TC cases recorded in the IBTrACS database are included in our analysis to ensure a comprehensive examination of TC activities. All datasets are analyzed over the period spanning from 1982 to 2022, with the anomaly of each variable defined as the deviation from the corresponding climatological value between 1991 and 2020.

Definition of marine heatwaves

A MHW is defined as an anomalously warm event arising when the daily SST exceeds a threshold corresponding to the 90th percentile of the climatological daily mean for a minimum duration of five consecutive days1. For each calendar day, the 90th percentile is determined via historical daily SST data from an 11-day window centered on that day. The outcome is subsequently smoothed via a 31-day moving average. Events occurring successively with a gap of less than two days are combined into a single event.

Upper ocean heat content

The upper ocean heat content (UOHC) is used to examine the roles of vertical heat redistribution, ocean stratification, and thermocline dynamics75,76. It is calculated as follows:

where \(\Delta {T}_{\left(x,y,z\right)}\) represents the temperature difference from 26 °C, meaning only temperatures equal to or greater than 26 °C are considered. \({D}_{26}\) is the depth of the 26 °C isotherm in the ocean. The parameters \(\rho =1025{kg}{m}^{-3}\) and \({C}_{p}=4000J{{Kg}}^{-1}{K}^{-1}\) denote the reference density and specific heat of seawater, respectively.

Mixed-layer heat budget

A mixed-layer heat budget analysis is conducted to investigate the physical processes underlying compound MHW and TC events. The mixed-layer temperature budget equation9,45 is expressed as follows:

where \({T}_{m}\), u, and v represent the ocean temperature and zonal and meridional ocean current velocities averaged over the mixed-layer depth (MLD), respectively. We utilize a spatially and temporally varying hm, defined as the MLD where the ocean temperature is 0.5 °C lower than its surface value77. Td represents the water temperature at a depth of 5 m below the MLD, indicating the presence of cold water entrained within the mixed layer. The entrainment rate (We) in Eq. (2) is calculated as follows:

where \(\frac{\partial {h}_{m}}{\partial t}\), \({w}_{{mb}}\), and \(\mathop{U}\limits^{ \rightharpoonup }\bullet \nabla {T}_{m}\) represent the tendency of the MLD, the velocity of the water parcel at the base of the mixed layer, and the horizontal advection of water parcels below the mixed layer, respectively78,79,80. The net surface heat flux anomaly (Q’) is the sum of the net downward shortwave radiation (SWR), net upward longwave radiation (LWR), sensible heat flux (SHF), and latent heat flux (LHF) at the ocean surface, with positive value indicating downward surface heat flux into the ocean. The terms ρ and Cp denote the reference density and specific heat of seawater, respectively.

In Eq. (2), the left-hand side is the mixed-layer ocean temperature tendency (Tend). On the right-hand side, \({Q}_{{net}}\) denotes the net surface heat flux term, \({ZAdv}\) (MAdv and VAdv) describes the zonal (meridional and vertical) advection of the anomalous temperature by the mean velocity, ZAdva (MAdva and VAdva) denotes the zonal (meridional and vertical) advection of the mean temperature by the anomalous velocity, ZAdv’ (MAdv’ and VAdv’) represents the nonlinear zonal (meridional and vertical) advection of the anomalous temperature by the anomalous velocity, and R represents the residual term.

Tropical cyclone genesis potential index

The genesis potential index (GPI) serves as the principal diagnostic tool for conducting a quantitative analysis of the impacts of large-scale environmental factors on TC genesis. Defined by Emanuel and Nolan56, the GPI is calculated as follows:

where η and RH represent the absolute vorticity at 850 hPa and the relative humidity at 700 hPa, respectively. \({V}_{{pot}}\) denotes the maximum potential intensity, as outlined by Bister and Emanuel81,82. \({V}_{{shear}}\) signifies the magnitude of the vertical wind shear between 200 hPa and 850 hPa, whereas ω represents the vertical pressure velocity at 500 hPa. We conduct five sensitivity tests to assess the individual impact of these parameters on the GPI. Each test focuses on adjusting only one variable (η, RH, Vpot, Vshear, or ω), while maintaining the other variables at their climatological values83.

Criterion for the onset time of the BoBSM

The onset time of the BoBSM is determined via the unified Asian summer monsoon onset criterion proposed by Liu et al.43. This criterion includes multiple indicators: (1) a transition of the 500–200 hPa averaged meridional temperature gradient (MTG, ∂T⁄∂y) from negative to positive, where T represents air temperature. A positive MTG indicates an increase in temperature toward the pole, while a negative MTG represents a decrease; (2) a shift in the seasonal wind direction at 10 m exceeding 100°; and (3) a significant increase in precipitation, exceeding 5 mm/day over the sea and 3 mm/day over the land. The BoBSM onset is identified on days when these conditions are all met and sustained for at least two pentads in the key region (5–15°N, 85–100°E).

Statistical significance tests

The statistical significance for the composites is assessed using two approaches: a two-tailed Welch’s t-test84,85 and a bootstrap hypothesis testing method86,87,88. The Welch’s t-test is applied to the difference between two sample means and performed at both the 95% and 90% confidence levels (p < 0.05 and p < 0.1), assuming that the variables are normally distributed. The formula of Welch’s t-test is as follows:

where \({\bar{x}}_{1}\) and \({\bar{x}}_{2}\) are the sample means, \({s}_{1}^{2}\) and \({s}_{2}^{2}\) are the sample variances, and \({n}_{1}\) and \({n}_{2}\) are the sample sizes. The degrees of freedom (df) is calculated as:

The bootstrap hypothesis testing is a robust statistical method for comparing two independent samples, making it particularly useful for small sample sizes and non-normally distributed data86,87,88,89. In this study, we treat MHW-TC compound events and comparison events (either non-MHW events, non-TC events, or climatological conditions) as two independent samples of sizes n and m, respectively. We calculate the observed mean difference between the two groups. Then, we merge the samples into a combined dataset of (n + m) observations and perform resampling with replacement. For each bootstrap iteration, we randomly select n and m observations from the merged dataset, compute their means, and determine the difference as the test statistic. This process is repeated 3000 times to generate a distribution of bootstrap statistics. The p-value is then estimated as the proportion of bootstrap statistics exceeding the original observed difference. Using significance thresholds of α = 0.05 or α = 0.1, we reject the null hypothesis when \(p < \alpha\), indicating statistically significant differences between the groups. Note that the results from these two statistical significance tests are generally consistent; therefore, only the results from the bootstrap hypothesis testing are presented in this study.

Data availability

All data related to this study are publicly available. The NOAA OISST dataset is available at https://downloads.psl.noaa.gov/Datasets/noaa.oisst.v2.highres. The NCEP2 reanalysis data are available from https://psl.noaa.gov/data/gridded/data.ncep.reanalysis2.html. The pentad GODAS dataset can be obtained from https://ftp.cpc.ncep.noaa.gov/godas/. The IBTrACS dataset is available at https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/products/international-best-track-archive.

Code availability

The MHW definition used in this study is available as software modules in Python, available at https://github.com/ecjoliver/marineHeatWaves. The maximum potential intensity is available as software modules in Python, available through https://github.com/dgilford/tcpyPI.

References

Hobday, A. J. et al. A hierarchical approach to defining marine heatwaves. Prog. Oceanogr. 141, 227–238 (2016).

Burger, F., Terhaar, J. & Frölicher, T. Compound marine heatwaves and ocean acidity extremes. Nat. Commun. 13, 4722 (2022).

Gupta, A. et al. Drivers and impacts of the most extreme marine heatwave events. Sci. Rep. 10, 19359 (2020).

Smith, K. E. et al. Socioeconomic impacts of marine heatwaves: Global issues and opportunities. Science 374, eabj3593 (2021).

Di Lorenzo, E. & Mantua, N. Multi-year persistence of the 2014/15 North Pacific marine heatwave. Nat. Clim. Change 6, 1042–1047 (2016).

Holbrook, N. J. et al. Keeping pace with marine heatwaves. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 1, 482–493 (2020).

Dzwonkowski, B. et al. Compounding impact of severe weather events fuels marine heatwave in the coastal ocean. Nat. Commun. 11, 4623 (2020).

Gruber, N., Boyd, P., Frölicher, T. & Vogt, M. Biogeochemical extremes and compound events in the ocean. Nature 600, 395–407 (2021).

Liu, K., Xu, K., Zhu, C. & Liu, B. Diversity of Marine Heatwaves in the South China Sea regulated by the ENSO phase. J. Clim. 35, 877–893 (2022).

Ren, X., Liu, W., Capotondi, A., Amaya, D. J. & Holbrook, N. J. The Pacific Decadal Oscillation modulated marine heatwaves in the Northeast Pacific during past decades. Commun. Earth Environ. 4, 218 (2023).

Beliyana, E., Ningsih, N. S., Gunawan, S. R. & Tarya, A. Characteristics of Marine Heatwaves in the Indonesian Waters during the PDO, ENSO, and IOD Phases and Their Relationships to Net Surface Heat Flux. Atmosphere 14, 1035 (2023).

Han, W. et al. Sea level extremes and compounding marine heatwaves in coastal Indonesia. Nat. Commun. 13, 6410 (2022).

Oliver, E. C. J. et al. Longer and more frequent marine heatwaves over the past century. Nat. Commun. 9, 1324 (2018).

Zscheischler, J. et al. A typology of compound weather and climate events. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 1, 333–347 (2020).

Zscheischler, J. et al. Future climate risk from compound events. Nat. Clim. Change 8, 469–477 (2018).

Grix, N., Zscheischler, J., Laufkötter, C., Rousseaux, C. & Frölicher, T. Compound high-temperature and low-chlorophyll extremes in the ocean over the satellite period. Biogeosciences 18, 2119–2137 (2021).

Grix, N., Zscheischler, J., Rodgers, K., Yamaguchi, R. & Frölicher, T. Hotspots and Drivers of Compound Marine Heatwave and Low Net Primary Production Extremes. Biogeosciences 19, 5807–5835 (2022).

Liu, H., Xunwei, N., Cui, C. & Wei, Z. Compound marine heatwaves and low sea surface salinity extremes over the tropical Pacific Ocean. Environ. Res. Lett. 18, 064001 (2023).

Li, C. et al. The ocean losing its breath under the heatwaves. Nat. Commun. 15, 6840 (2024).

Ridder, N. N. et al. Global hotspots for the occurrence of compound events. Nat. Commun. 11, 5956 (2020).

Yao, Y., Wang, J. & Zou, X. Rapid changes in heatwaves pose dual challenge in Eastern China and its adjacent seas. Front. Mar. Sci. 9, 979391 (2022).

Mawren, D., Hermes, J. & Reason, C. Marine heat waves and tropical cyclones - Two devastating types of coastal hazard in South-eastern Africa. Estuar., Coast. Shelf Sci. 277, 108056 (2022).

Choi, H.-Y., Park, M.-S., Kim, H.-S. & Lee, S. Marine heatwave events strengthen the intensity of tropical cyclones. Commun. Earth Environ. 5, 69 (2024).

Pun, I., Hsu, H.-H., Moon, I.-J., Lin, I.-I. & Jeong, J.-Y. Marine heatwave as a supercharger for the strongest typhoon in the East China Sea. npj Climate Atm. Sci. 6, 128 (2023).

Vinayachandran, P. N. & Shetye, S. R. The warm pool in the Indian Ocean. Proc. Indian Acad. Sci. (Earth Planet Sci.) 100, 165–175 (1991).

Lau, W. & Yang, S. Climatology and Interannual variability of the Southeast Asian summer monsoon. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 14, 141–162 (1997).

Mao, J. & Wu, G. Interannual variability in the onset of the summer monsoon over the Eastern Bay of Bengal. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 89, 155–170 (2007).

Wu, G. & Zhang, Y. Tibetan Plateau forcing and the timing of the monsoon onset over South Asia and the South China Sea. Mon. Weather Rev. 126, 913–927 (1998).

Wu, G., Guan, Y., Liu, Y., Yan, J. & Mao, J. Air-Sea interaction and formation of the Asian summer monsoon onset vortex over the Bay of Bengal. Clim. Dyn. 38, 261–279 (2011).

Wu, G. et al. Vortex genesis over the Bay of Bengal in spring and its role in the onset of the Asian Summer Monsoon. Sci. China Earth Sci. 54, 1–9 (2011).

Beal, L. M. et al. A road map to IndOOS-2 better observations of the rapidly warming Indian Ocean. Bull. Am. Meteor. Soc. 101, E1891–E1913 (2020).

Lin, X. et al. Seasonal Diversity of El Niño‐Induced Marine Heatwave Increases in the Bay of Bengal. Geophys. Res. Lett. 50, e2022GL100807 (2023).

Subbaramayya, I. & Rao, S. R. M. Frequency of Bay of Bengal Cyclones in the Post-Monsoon Season. Mon. Weather Rev. 112, 1640–1642 (1984).

Li, Z., Yu, W., Li, T., Murty, V. S. N. & Tangang, F. Bimodal Character of Cyclone Climatology in the Bay of Bengal Modulated by Monsoon Seasonal Cycle. J. Clim. 26, 1033–1046 (2013).

Mani, B., Chakraborty, A. & Mandal, M. Changes in tropical cyclone activity in north Indian Ocean during satellite era (1981-2014). Int. J Climatology 38, 2819–2837 (2018).

Akhter, S., Holloway, C., Hodges, K. & Vannière, B. How well do high-resolution Global Climate Models (GCMs) simulate tropical cyclones in the Bay of Bengal? Clim. Dyn. 61, 3581–3604 (2023).

Kumar, S. et al. Analysis of marine heatwaves over the Bay of Bengal during 1982-2021. Sci. Rep. 13, 14235 (2023).

Rathore, S. et al. Interactions Between a Marine Heatwave and Tropical Cyclone Amphan in the Bay of Bengal in 2020. Front. Clim. 4, 861477 (2022).

Mukherjee, A. K. & Paul, D. K. Influence of Arabian Sea cyclonic systems on the onset of monsoon. Results of summer MONEX field phase research part A; FGGE Operations Report. 9, 62–67 (1980).

Krishnamurti, T. N., Ardanuy, P., Ramanathan, Y. & Pasch, R. On the Onset Vortex of the Summer Monsoon. Mon. Weather Rev. 109, 344–363 (1981).

Lau, K.-M., Wu, H.-T. & Yang, S. Hydrologic Processes Associated with the First Transition of the Asian Summer Monsoon: A Pilot Satellite Study. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 79, 1871–1882 (1998).

Vinayachandran, P., Shankar, D., Kurian, J., Durand, F. & Shenoi, S. Arabian Sea mini warm pool and the monsoon onset vortex. Current Sci. 93, 203–214 (2007).

Liu, B. et al. Asian summer monsoon onset barrier and its formation mechanism. Clim. Dyn. 45, 711–726 (2014).

Liu, B., Wu, G., Mao, J. & He, J. Genesis of the South Asian High and Its Impact on the Asian Summer Monsoon Onset. J. Clim. 26, 2976–2991 (2013).

Xu, K., Liu, B., Liu, Y., Wang, W. & HE, Z. Effects of monsoon onset vortex on heat budget in the mixed layer of the Bay of Bengal. J. Oceanol. Limnol. 38, 1616–1631 (2020).

Yang, S. & Ji, Z. Delayed Impact of Biomass Burning in the Indochinese Peninsula on the Bay of Bengal Monsoon. J. Clim. 37, 6769–6780 (2024).

Gao, X., Li, G., Liu, J. & Long, S.-M. The Trend and Interannual Variability of Marine Heatwaves over the Bay of Bengal. Atmosphere 13, 469 (2022).

Deshpande, M. et al. Changing status of tropical cyclones over the north Indian Ocean. Clim. Dyn. 57, 3545–3567 (2021).

DeMott, C. A., Benedict, J. J., Klingaman, N. P., Woolnough, S. J. & Randall, D. A. Diagnosing ocean feedbacks to the MJO: SST-modulated surface fluxes and the moist static energy budget. J. Geophys. Res.: Atm. 121, 8350–8373 (2016).

Wang, C., Wang, W., Wang, D. & Wang, Q. Interannual variability of the South China Sea associated with El Niño. J. Geophys. Res.: Oceans 111, C03023 (2006).

Liu, Y., Tang, D. & Morozov, E. Chlorophyll Concentration Response to the Typhoon Wind-Pump Induced Upper Ocean Processes Considering Air–Sea Heat Exchange. Remote Sens. 11, 1825 (2019).

Xu, H., Tang, D., Liu, Y. & Li, Y. Dissolved oxygen responses to tropical cyclones ‘Wind Pump’ on pre-existing cyclonic and anticyclonic eddies in the Bay of Bengal. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 146, 838–847 (2019).

Ye, H. et al. Examining the Impact of Tropical Cyclones on Air-Sea CO2 Exchanges in the Bay of Bengal Based on Satellite Data and In Situ Observations. J. Geophys. Res.: Oceans 124, 555–576 (2019).

Wu, D., Ju, X., Sun, J., Hu, X. & Xiong, X. Escalation of tropical cyclone impacts on the northwestern Bay of Bengal over the past decade. Clim. Dyn. 62, 5645–5662 (2024).

Wang, B., Xiang, B. & Lee, J.-Y. Subtropical High predictability establishes a promising way for monsoon and tropical storm predictions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110, 2718–2722 (2013).

Emanuel, K. A. & Nolan, D. S. Tropical cyclone activity and the global climate system. In 26th Conference on Hurricanes and Tropical Meteorology, Vol. 10A.2, 240–241 (American Meteorological Society, Miami, Florida, 2004).

Woolnough, S. J., Slingo, J. M. & Hoskins, B. J. The relationship between convection and sea surface temperature on intraseasonal timescales. J. Clim. 13, 2086–2104 (2000).

Fan, X. & Li, Y. A statistical study on promoting effects of tropical cyclones over the Bay of Bengal on the South China Sea summer monsoon onset. Atm. Sci. Lett. 24, e1164. (2023).

Liu, B. & Zhu, C. Boosting Effect of Tropical Cyclone “Fani” on the Onset of the South China Sea Summer Monsoon in 2019. J. Geophys. Res.: Atm. 125, e2019JD031891 (2020).

Dai, A. et al. The relative roles of upper and lower tropospheric thermal contrasts and tropical influences in driving Asian summer monsoons. J. Geophys. Res. 118, 7024–7045 (2013).

Jiang, X. & Li, J. Influence of the annual cycle of sea surface temperature on the monsoon onset. J. Geophys. Res. 116, D10105 (2011).

Ueda, H. & Yasunari, T. Role of Warming over the Tibetan Plateau in Early Onset of the Summer Monsoon over the Bay of Bengal and the South China Sea. J. Meteorological Soc. Jpn. 76, 1–12 (1998).

Wu, X. & Mao, J. Decadal Changes in Interannual Dependence of the Bay of Bengal Summer Monsoon Onset on ENSO Modulated by the Pacific Decadal Oscillation. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 36, 1404–1416 (2019).

Xue, X., Chen, W., Chen, S. & Feng, J. PDO modulation of the ENSO impact on the summer South Asian high. Clim. Dyn. 50, 1393–1411 (2018).

Ashok, K., Guan, Z. & Yamagata, T. Impact of the Indian Ocean dipole on the relationship between the Indian monsoon rainfall and ENSO. Geophys. Res. Lett. 28, 4499–4502 (2001).

Ashok, K., Guan, Z., Saji, N. H. & Yamagata, T. Individual and Combined Influences of ENSO and the Indian Ocean Dipole on the Indian Summer Monsoon. J. Clim. 17, 3141–3155 (2004).

Ashok, K. & Saji, N. H. On the impacts of ENSO and Indian Ocean dipole events on sub-regional Indian summer monsoon rainfall. Nat. Hazards 42, 273–285 (2007).

Xie, S.-P. et al. Indo-western Pacific ocean capacitor and coherent climate anomalies in post-ENSO summer: A review. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 33, 411–432 (2016).

Li, K. et al. Strong modulations on the Bay of Bengal monsoon onset vortex by the first northward-propagating intra-seasonal oscillation. Clim. Dyn. 47, 107–115 (2016).

Li, T. & Ju, J. The impact of tropic Indian MJO activities on Intra-Seasonal Oscillation of Southwest Summer Monsoon over Bay of Bengal. Acta Meteorologica Sinica. 71, 38–49 (2013).

Reynolds, R. W., Smith, T. M., Liu, C., Chelton, D. B. & Casey, K. S. Daily High-Resolution-Blended Analyses for Sea Surface Temperature. J. Clim. 20, 5473–5496 (2007).

Kanamitsu, M. et al. NCEP–DOE AMIP-II Reanalysis (R-2). Bull. Am. Meteorological Soc. 83, 1631–1644 (2002).

Behringer, D. The Global Ocean Data Assimilation System (GODAS) at NCEP. Preprints, 11th Symp. on Integrated Observing and Assimilation Systems for Atmosphere, Oceans, and Land Surface, San Antonio, TX, Amer. Meteor. Soc., 3.3. Available online at http://ams.confex.com/ams/87ANNUAL/techprogram/paper_119541.htm (2007).

Knapp, K. R., Kruk, M. C., Levinson, D. H., Diamond, H. J. & Neumann, C. J. The International Best Track Archive For Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS): Unifying Tropical Cyclone Data. Bull. Am. Meteorological Soc. 91, 363–376 (2010).

Chih, C.-H. & Wu, C.-C. Exploratory Analysis of Upper-Ocean Heat Content and Sea Surface Temperature Underlying Tropical Cyclone Rapid Intensification in the Western North Pacific. J. Clim. 33, 1031–1050 (2020).

Jangir, B., Swain, D. & Ghose, S. K. Influence of eddies and tropical cyclone heat potential on intensity changes of tropical cyclones in the North Indian Ocean. Adv. Space Res. 68, 773–786 (2021).

Monterey G. I. & Levitus, S. Seasonal Variability of Mixed Layer Depth for the World Ocean. (United States. US Department of Commerce, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, National Environmental Satellite, Data, and Information Service, 1997).

Du, Y., Qu, T., Meyers, G., Masumoto, Y. & Sasaki, H. Seasonal heat budget in the mixed layer of the southeastern tropical Indian Ocean in a high resolution general circulation model. J. Geophys. Res. 110, C04012 (2005).

Qiu, B. Interannual Variability of the Kuroshio Extension System and Its Impact on the Wintertime SST Field. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 30, 1486–1502 (2000).

Qu, T. Mixed layer heat balance in the western North Pacific. J. Geophys. Res.: Oceans 108, 3242 (2003).

Bister, M. & Emanuel, K. A. Low frequency variability of tropical cyclone potential intensity 1. Interannual to interdecadal variability. J. Geophys. Res. 107, 4801 (2002).

Gilford, D. pyPI (v1.3): Tropical Cyclone Potential Intensity Calculations in Python. Geoscientific Model Dev. 14, 2351–2369 (2021).

Camargo, S., Emanuel, K. & Sobel, A. Use of a Genesis Potential Index to Diagnose ENSO Effects on Tropical Cyclone Genesis. J. Clim. 20, 4819–4834 (2007).

Welch, B. L. The Generalization of ‘Student’s’ Problem when Several Different Population Variances are Involved. Biometrika 34, 28–35 (1947).

Wilks, D. Statistical Methods in Atmospheric Sciences (Elsevier, 2019).

Efron, B. Bootstrap Methods: Another Look at the Jackknife. Ann. Stat. 7, 1–26 (1979).

Johnson, R. W. An Introduction to the Bootstrap. Teach. Stat. 23, 49–54 (2001).

Kiktev, D., Sexton, D. M. H., Alexander, L. & Folland, C. K. Comparison of Modeled and Observed Trends in Indices of Daily Climate Extremes. J. Clim. 16, 3560–3571 (2003).

Sheng, C., Zhang, S., Liu, Y., Wu, G. & He, B. Interannual impact of tropical southern Atlantic SST on surface air temperature over East Asia during boreal spring. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 6, 186 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This work was jointly supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (2022YFE0203500), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (W2441014, 42275024), the Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (2023B1515020009, 2022B1212050003, 2024B1515040024), the special fund of the South China Sea Institute of Oceanology CAS (SCSIO2023QY01 and SCSIO2023HC07), the International Partnership Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (059GJHZ2023104MI), and the Hainan Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 423RC547). The authors also acknowledge the China‐Sri Lanka Joint Center for Education and Research, Chinese Academy of Sciences.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.X. conceived the idea for the study, K.X., W.W., and H.X. supervised the work, X.Z. conducted the analyses, and X.Z. and K.X. drafted the initial manuscript. K.A., J.S., L.Z., J.Y., B.L., and C.T. contributed to the improvement of the manuscript. All authors provided critical feedback and helped shape the research and analyses.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, X., Xu, K., Ashok, K. et al. Compound marine heatwaves and tropical cyclones delay the onset of the Bay of Bengal summer monsoon. npj Clim Atmos Sci 8, 162 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-01061-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-01061-5