Abstract

The role of submesoscale processes as the primary energy source for ocean turbulence remains controversial due to observational limitations. Seismic imaging captures multi-scale processes from mesoscale to finescale, allowing us to infer turbulence processes. This study identified hundreds of ~200-m-long high seismic reflection patches, primarily caused by vertical temperature changes, moving at 0.24 ± 0.13 m/s across the deep-reaching front of Bransfield Current, Antarctica. Patch distribution within the main current is uneven, increasing exponentially towards the frontal leading edge. Over 95% of the detected patches are concentrated within 10 km from the frontal leading edge, where elevated Thorpe-scale diffusivity exceeding 10−2 m2/s has been observed hydrographically. These patches may indicate stratified turbulence, including broken internal wave segments, interleaving interfaces, and overturns, which may correspond to wave breaking, frontal instability, and shear instability, respectively. Our findings challenge the recently questioned classical hypothesis that energy cascades directly from internal waves to isotropic turbulence, instead supporting the paradigm of a stratified turbulence stage.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The characteristics of ocean submesoscale dynamics have received considerable attention in the past two decades near the ocean surface1,2. However, it is still controversial whether the surface processes or submesoscale processes serve as the dominant cross-scale energy sources for ocean turbulence3,4. The energy transfer between mesoscale and submesoscale motions has been widely studied5,6. In contrast, the energy cascade from submesoscale or finescale motions to isotropic turbulence scales remains poorly understood, largely due to the limitations in lateral resolution. It has been hypothesized that a transitional subrange of stratified turbulence exists before energy cascades from submesoscales to isotropic turbulence, with internal waves acting as intermediaries, using numerical simulations, parameterization schemes, and statistical spectral analyses7,8,9,10. More observational evidence is needed to support this paradigm, particularly from representative locations characterized by intense turbulence driven by submesoscale dynamics free from surface processes interference.

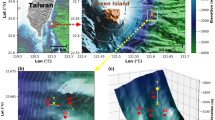

The Bransfield Strait (BS) is an important passage with a variety of water masses, and thus a critical place for Antarctic water mass modification via strong turbulent mixing11,12,13,14,15. The overall circulation consists of (1) three inflows of the Circumpolar Deep Water (CDW), Transitional Bellingshausen Water (TBW), and Transitional Weddell Water (TWW), (2) a strait throughflow of the Bransfield Current (BC), and (3) an outflow of the Bransfield Current Recirculation (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Note 1). Among them, the Bransfield Current baroclinic jet is the most intense, distinctive, and permanently present feature in the Bransfield Strait16. It carries relatively warm/fresh water from CDW and TBW, and flows through the Bransfield Strait along the southern slope of the South Shetland Islands (SSI), with a mean width of 10‒15 km and a typical current velocity of ~0.35 ± 0.10 m/s (Supplementary Table 1)12,14,15,17. The Bransfield Current is in geostrophic balance and is associated with the submesoscale Bransfield Front (BF), which separates the TBW from the TWW12,16,18. The Bransfield Front is a sharp and steep subsurface front extending from 50 to 500 m depth so unlikely influenced by wind forcing substantially12,14. The coarse sampling intervals of typically 10‒50 km (Supplementary Table 2) in previous hydrographic observations did not adequately resolve the Bransfield Current accompanying submesoscale or finescale features.

a The Antarctic Circumpolar Current (ACC) system around the Antarctic and this study region (red box) at the tip of the Antarctic Peninsula. b Close-up of the study region showing the bathymetry, seismic lines, and the Bransfield Current (BC) system in the Bransfield Strait (BS). The numbered gray lines are the seismic sections with blue starting points. The red point is the start of the entire seismic acquisition. The black sub-sections are shown in Fig. 3, and the orange parts are the locations of the seismically constrained Bransfield Current. The numbered curves are the ① Bransfield Current, ② Bransfield Current Recirculation, ③ Circumpolar Deep Water (CDW), ④ Transitional Bellingshausen Water (TBW), ⑤ Transitional Weddell Water (TWW), and ⑥ Peninsula Front (PF). c Latitude as a function of time showing the progression of the seismic acquisition during the cruise in 1991. BLS Bellingshausen Sea, WDS Weddell Sea, ESB eastern sub-basin, CSB central sub-basin, WSB western sub-basin. SAF Sub-Antarctic Front, ACCPF ACC Polar Front, SACCF Southern ACC Front, SB Southern Boundary.

Over the past 20 years, the method of Seismic Oceanography has been widely used to infer multi-scale ocean processes, including currents, eddies, tides, submesoscale turbulence, internal waves, stratification staircases, and turbulence, ranging from mesoscale O(100 km) to finescale O(10 m)19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26. It offers quick (~5 knots) underway observations of continuous water structures from surface to bottom with spatial sampling of 10 m or finer both horizontally and vertically. It has been confirmed to be applicable in the polar region, even though the temperature gradients are much weaker than in the tropical and subtropical regions27,28. In this study, using seismic data acquired in 1991 covering the whole Bransfield Strait (Fig. 1; “Methods”), the Bransfield Strait current system structures are revealed by reflection intensity from basin scale to ~25 m horizontal scale, including the Bransfield Current, Bransfield Front, TBW, TWW, CDW, eddies, and turbulent events. This study mainly focuses on the submesoscale to finescale features occurring within the Bransfield Current, such as the frontal leading edge and the stratified turbulence, and their estimated contributions to turbulent mixing.

Results and discussion

Basin-scale seismic feature of the Bransfield Strait waters

Throughout the Bransfield Strait basin, 17 seismic images were processed to depict detailed water structures, and Line C04 captured the typical processes occurring there (Fig. 2). The most distinct feature is the Bransfield Front with a steep oblique reflection band ~5 km wide above the South Shetland Islands Slope. Above ~400 m, the front is submerged within the TBW, while below ~400 m, it distinctly separates the TWW from the TBW. The widths of the Bransfield Current and TBW surface outflow are over 15 and 30 km, respectively, covering half of the basin surface approximately. The gradual shoaling of the TBW to the deep basin suggests the Peninsula Front at ~45 km between the surface TBW and TWW. This front cannot be well imaged seismically because of the near surface blind zone, but has been hydrographically observed12,17. The newly formed surface cold and dense TWW with weak stratification subducts down to ~800 m, interacting with the pre-existing, deep, well-mixed, acoustically transparent TWW (Fig. 2). Rich submesoscale filaments are generated by processes like convergence, stretching, and entrainment. The subduction of the Weddell Sea water can be tracked on Lines E17, E01, C02, C03, and C04, outlining the entrance of the deep/bottom TWW into the Bransfield Strait (Supplementary Fig. 1)13.

a Reflection of Line C04 (i.e., Line 04 in the central sub-basin in Fig. 1). b A seismic interpretation of the water structure based on the regional hydrographic observations. Two fronts are Bransfield Front (BF) and Peninsula Front (PF). Due to the seismic survey geometry, data are missing at depths shallower than ~100 m. Therefore, the surface PF is inferred based on the distribution of TBW and TWW water masses. The black lines at the bottom right corner show a dip angle reference. The amplitudes of the seismic data in (b) are a factor of 0.5 of those in (a). The topographic names are South Shetland Islands (SSI) Slope on the northwest side and Antarctic Peninsula (Ant. Pen.) Shelf/Slope on the southeast side.

The reflection strengths and corresponding instantaneous amplitudes (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Fig. 2) enable tracking the Bransfield Current/Front. The submesoscale Bransfield Front is characterized by strong, steep, and coherent reflections; the TBW’s reflection is relatively weaker, intermittent, and heterogeneous; and the TWW’s reflection is nearly homogeneous. The widths of the Bransfield Current near the surface are estimated to vary from 6 to 25 km, with an average width of 13 km, consistent with the hydrographic results of ~12‒15 km12,14. Specifically, the Bransfield Front is not a single boundary but a reflection coherent zone ~5 km wide, characterized by clusters of similar reflectors, unresolved by hydrographic observations.

The sub-sections are arranged in order from west to east (black segments in Fig. 1). The color represents the reflection strength, which outlines the water finestructure. The prefix letters W, C, and E indicate the corresponding line in the western, central, and eastern sub-basin. The orange top bars with widths in kilometers are the inferred locations of the Bransfield Current corresponding to the orange segments in Fig. 1.

The Bransfield Current flow pattern can be identified from the seismic images (Fig. 3). Upstream, the warm TBW, carrying the Bellingshausen Sea, Gerlache Strait, and Circumpolar Current waters, converges in the western sub-basin, creating a broad and complex frontal zone (Line W21)15. It quickly converges into a steep, narrow, near barotropic, and full-depth frontal current, forming a distinct and sharp boundary between TBW and TWW (Lines W14 and W12). It deflects to the north close to the South Shetland Islands Slope around Deception Island. In the central sub-basin, the frontal steepness decreases to a stable value (Lines C11‒C02). Starting from Line C09, some of the TBW appears to flow over the front, characterized by strong to moderate reflection coherent patches 5‒10 km wide and 200 m thick between 200 and 400 m depth (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Fig. 2). These could be submesoscale to mesoscale subsurface eddies, where baroclinic instability of the Bransfield Current starts to favor TBW shedding near Lines C10 and C09, marking the initial eddy generation point12,29. Once the current runs out of the central sub-basin over the sill to the shallow shelf, the front becomes narrower, faint, and incoherent (Line E01). Therefore, the strong fronts on Lines E17 and E18 might not be the Bransfield Front anymore. Additional reflection patches on E01 and E17 (Supplementary Fig. 3) suggest a weak branch of the Bransfield Current entering the eastern sub-basin, consistent with previous observations15,30.

The Bransfield Current/Front main properties, including geographic extension, vertical depth, dip angle, geostrophic speed, and Rossby number, are estimated for each section (Fig. 4; “Methods”; Supplementary Note 2). The vertical extent of the current supports the view that it is a coastal gravity current rather than a western boundary current (“Methods”)12,14. The first-order vertical motion \(w\) is estimated from the vertical extent of the Bransfield Current (“Methods”; Supplementary Note 3). These parameters are helpful to constrain the current properties at different stages, and finally deduce its evolution scenarios spatially from source to the end, which is still under debate (Supplementary Notes 2‒4). Seismic and hydrographic data confirm TBW convergence in the western sub-basin, sourcing the Bransfield Current (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Figs. 4 and 5). At the east sill, the flow bifurcates, with one branch turning northwest and the other continuing into the eastern sub-basin (Supplementary Fig. 3)11,15,30.

a Locations of the mapped fronts (orange) in Fig. 3. b Water depth just beneath the frontal leading edge and the vertical extension of the front. c Apparent dip angle (gray, uncorrected) and the corrected dip angle (orange). d Geostrophic velocities estimated using the thermal wind equation with the density differences from WOD18 (\({U}_{g}\), gray) and Sangrà et al.18 (\({U}_{g}\), orange). The green line shows the result from a mass conservation scheme (\({U}_{m}\)). e The estimated Rossby number assuming the geostrophic velocity is 0.35 m/s for the uncorrected (gray) and the corrected (orange) length scales. The green line shows the results using \({U}_{m}\) in (d). Note that the lower x axes in (b–e) indicate the longitudes marked in (e), while the upper x axes show the front locations in (b), corresponding to the seismic lines in (a).

An updated 3D schematic of the basin-scale Bransfield Current system and its accompanying processes is illustrated in Fig. 5. The Bransfield Current transports a buoyant flow of TBW and CDW throughout the Bransfield Strait. The baroclinic pressure gradient forms a distinct Bransfield Front between the TBW and TWW in the central sub-basin balanced by the Coriolis force. Mesoscale to submesoscale vortices shed from the current are prevalent in the central sub-basin above the TWW. The current bifurcates after exiting the central sub-basin, with one branch entering the eastern sub-basin and the other turning northward out of the Bransfield Strait. Another branch of ACC water, probably CDW, flows into the eastern sub-basin through the channel between Elephant Island and South Shetland Islands (Supplementary Note 5).

A 3D schematic of the Bransfield Current system and its bifurcation, eddies, and mixing in the Bransfield Strait. The water mass abbreviations are the CDW Circumpolar Deep Water, BC Bransfield Current, TBW Transitional Bellingshausen Water, TWW Transitional Weddell Water. WSB, CSB, and ESB stand for the western, central, and eastern sub-basin, respectively.

Submesoscale to finescale seismic structures of the Bransfield Current/Front

Detailed interpretations are provided for three representative subsurface frontal structures on Lines W14, C09, and E17 in each sub-basin (Fig. 6). On Line W14, the most significant feature is the sharp and steep Bransfield Front between the Bransfield Current and TWW. The dip angle reaches ~25.2 ± 3.5°. This Bransfield Front comprises multiple fronts with at least four parallel reflection bands, which gradually weaken from the frontal leading edge to the central Bransfield Current (gray arrows in Fig. 6). The bands are spaced apart by low reflection vertical zones, suggesting that strong horizontal shears may exist in the cross-frontal direction by varying Bransfield Current velocities. Such shears tear up the stratification into broken segments and promote surrounding water intrusion and mixing. The narrowing and shoaling sill acts as an inlet constriction which forces a swift flow and a steep front (Figs. 1, 3, and 4 and Supplementary Fig. 2).

Three representative frontal structures (a, c, e) and their corresponding possible interpretation (b, d, f) for Lines W14, C09, and E17 in each sub-basin from Fig. 3. The color palettes are the same as in Fig. 2. Note the multi-front features (gray arrows in (b) and (d)) for the Bransfield Front. AC (AF) Anticyclonic eddy Current/Front, CDW (CF) Circumpolar Deep Water (Front).

On Line C09, the Bransfield Front is still distinct but has been significantly altered. The high reflection segment above ~400 m is submerged within the TBW, and the segment below ~400 m separates the Bransfield Current and TWW. Its dip angle is reduced to ~3.4 ± 0.2°, consistent with other fronts (Lines C10‒C02) in the central sub-basin, indicating that geostrophic balance may have been reached. This front has two distinct reflection bands (gray arrows in Fig. 6) like the fronts upstream in the central sub-basin (e.g., C11 and C10); the fronts downstream are reduced to only one band. On Line E17, the imaged front has a single reflection band and its dip angle is only about 1.5 ± 0.3°, which is much gentler than the Bransfield Front in the central sub-basin. This front might not be the edge of the Bransfield Front, but a current branch intrusion of the CDW (Supplementary Note 5).

In addition, it has been reported that another CDW branch intrudes into the Bransfield Strait through the Boyd Strait between Smith Island and Snow Island at ~350‒550 m deep11,12,31,32. This CDW might have been seismically captured as revealed by the detailed finescale structures (Fig. 6). It may appear in the western and central sub-basins on Lines W14, C15, C11, C10, and C09 at ~400‒700 m deep just beneath the Bransfield Current separated by a moderate reflection boundary (Figs. 3 and 6). After Line 09, the CDW is no longer traceable, presumably due to its similar properties following mixing with the TBW17.

Isolated reflection patches and their estimated motion

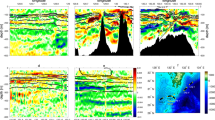

Localized turbulent events including stratified segments (breaking patches), intrusions, and overturns can be developed in the intense flow in the Bransfield Strait, where the instabilities are presumably easily triggered in the weak stratification with \(N\approx\)1.5 × 10−3 s−1 (from historical CTD at 400 m depth, see “Methods”). The T or S gradients in turbulent patches with shear or strain are enhanced by stretching and folding of the isopycnals33. In seismic images, therefore, these events or patches may be illustrated as small, isolated, bright reflections scattered randomly in regions with high vertical temperature or density gradients caused by shear or strain, distinguishing them from homogeneous water or well-stratified thermocline (Figs. 7 and 8). Assuming a typical reflection patch ~30‒40 m thick, its horizontal scale should be shorter than 350‒500 m according to the aspect ratio \(N/f\approx 12\), under which anisotropic turbulence may develop following the loss of the geostrophic balance34. Thanks to the redundancy of the seismic data acquisition, the instantaneous motion of the patches along the section can be detected35,36. An improved scheme is developed to derive this from tracking reflection energy instead of phase, which is more equivocal. After carefully testing with synthetic cases (“Methods”), we applied the method to the seismic data, as shown in the example in Fig. 7. Nine successive shot gathers captured the progression of a reflection patch location over an approximate 3-min window (Fig. 7a, e). The instantaneous amplitudes depict the patch’s location and motion (Fig. 7b, c). An optimal moving velocity of 0.28 ± 0.03 m/s is extracted at the peak of the stacked energy (Fig. 7d).

a Pre-stack seismic reflection data for each shot (sh) along the streamer channels (ch) in a time (depth) window of 0.08 s (60 m). b Instantaneous amplitudes showing the reflection anomaly in (a). c Summation of the instantaneous amplitudes used for tracking the energy peak for each shot. The dashed lines are the alignments of the reference moving velocities. d Spatial vespagram for searching the optimal velocity of the reflection patch by slant stacking. e Seismic image showing the concerned reflection patch (black box) and its moving direction (cyan arrow). The upper left and lower right subsets are close-ups of the seismic reflection patch and its instantaneous amplitude, respectively.

Measured patch velocities and their extrapolated motion fields overlaid on the corresponding seismic images for lines C15 (a), W14 (b), and C03 (c). Line C15 is approximately along the Bransfield Current direction. Line W14 is upstream of the Bransfield Current. Line C03 is downstream of the Bransfield Current with a shed submesoscale eddy. Reference velocities (1 m/s) are displayed on the bottom right of each panel.

Cross-front (along-shiptrack) velocities of the reflection patches are estimated around the Bransfield Front (Supplementary Fig. 6). Roughly, the velocity fields look patchy, suggesting smaller-scale features emerging from the mean flow, but some general patterns can be identified. Most velocities are coherent along the forefront, consistently northward or southward. Frontal patches in the western and eastern sub-basins are moving northward (Lines W14, W12, E17, and E18), and patches in the central sub-basin and the western part of the eastern sub-basin are moving southward (Lines C15‒C02 and E01). Velocity directions are more variable in the middle of the Bransfield Current compared to the frontal leading edge. High velocities are more frequent in the upper water column. Some of the instantaneous cross-front velocities are comparable to or even significantly exceed the mean Bransfield Current velocity of 0.35 m/s, which is consistent with some previous ADCP observations15.

Figure 8 shows three representative cases of patch motions. For Line C15, which runs nearly parallel to the Bransfield Current, the main current may dominate the overall pattern of the patch motion (Fig. 8a). The instantaneous velocities along the main current could reach 0.75 m/s at ~300 m depth. However, there are still many counter-flow events against the Bransfield Current, and their velocities are relatively small (−0.1 ~ −0.3 m/s). For Line W14 at the western sill, most of the patches are moving northward, and most of the velocities are ~0.35 m/s showing a nearly barotropic distribution (Fig. 8b). In contrast, the motion north of the front on Line C03 is baroclinic, with velocities decreasing from ~0.5 m/s to 0.1 m/s between depths of ~250 m to 750 m (Fig. 8c), similar to the pattern on Line C15 (Fig. 8a). The overall velocity direction on Line C03 is to the south, opposite to that on Line W14. There is a coherent reflection anomaly centered at ~4 km south of the Bransfield Front and 450 m depth at a range of 9‒13 km (Fig. 8c). Its size is about 300-m thick and 4-km wide, tilting at ~3.8°, close to the Bransfield Front’s ~4.4° tilt in the same direction. The reflection patches in the upper half of the water column are moving southward, while those on the lower half are moving northward, which is generally consistent with the overall pattern of the nearby Bransfield Current. It could be interpreted as a submesoscale eddy dynamically shed from the Bransfield Current due to frontal instability, since the reflection intensity, inclination, and depth are all comparable to the TBW.

Stratified turbulence and mixing within the Bransfield Front

Although it has been widely proven that turbulent signals can be inferred from seismic reflections via statistical spectrum analysis22,37,38, it remains uncertain whether individual turbulent events can be identified in seismic images. We regard the reflection patches in this study as turbulence-related events, including stratified segments, interleaving interfaces, and overturns (Fig. 9). The high reflection patches occur where frontal dynamics likely lead to turbulence. These high reflection regions are not seismic noise, because they are significantly above the ambient noise level in comparison to the weak response in TWW, and they are repeatedly detectable during the seismic acquisition (Fig. 7). Their average horizontal scale of 189 ± 37 m is close to the horizontal Coriolis scale \({L}_{f}\) of ~402 ± 232 m and is above the Ozmidov scale \({L}_{o}\) of 10 ± 6 m (“Methods”), indicating that these patches may be in a transition scale between internal waves and isotropic turbulence, or in an anisotropic or stratified turbulence regime as a result of a forward energy cascade7,8,39,40,41,42.

a Internal wave breaking. b Submesoscale induced water mass intrusion/interleaving. c Convective overturning. These possible turbulent processes may cause the reflection bright spots (short gray patches) in seismic images. Temperature profiles (T) and their conceptual seismographs (R) on the left correspond to dashed lines on the idealized sections.

We selected several historical CTD profiles from the austral summer and compared them with the detailed seismic structure of the Bransfield Front (Fig. 10). The composite results show that the synthetic seismograms from CTD profiles in specific sub-regions compare well to the seismic reflection (column 5 of Fig. 10). Historic CTD profiles show a variety of fine structures that would be consistent with the enhanced seismic reflections, including temperature/density steps, interleaving interfaces, and overturns (Fig. 9), even though the seismic and hydrographic data do not coincide in time or space.

Examples showing water properties and their comparisons between seismic images on Lines W21 (a), C09 (b), and C04 (c). CTD profiles are shown in Supplementary Fig. 4d (note these CTD profiles are not coincident in time or space with seismic data). Column 1: potential temperature profiles from CTD (gray) and mean temperature profiles for TBW (orange) and TWW (blue). Column 2: potential density from CTD profiles. Column 3: Thorpe scale. Column 4: Diapycnal diffusivity from Thorpe scale. Column 5: Synthetic seismogram from CTD profiles superimposed on the adjacent seismic images. Column 6: Θ-S diagram with contours of potential density (gray) and spiciness (light blue). Note that columns 1‒5 share the same y axis representing depth, while column 6 uses a y axis representing temperature.

The presence of internal waves may generate laterally coherent stratified interfaces or stacked interfaces in seismic images20. However, internal waves may not be well developed in the Bransfield Strait (Supplementary Fig. 10). Only a few reflectors are longer than a few kilometers, as would be expected of internal waves, and are always lack vertical coherence (Figs. 6, 9a, and 10). The weak stratification provides weak restoring force for internal wave oscillation and cannot sustain long-distance internal wave propagation, but favors a wave-breaking regime. The wave breaking causes local homogenization of the stratification and results in intermittent bright reflection patches hundreds of meters long between the local breaking (Figs. 6 and 9a). Wave breaking induced turbulent mixing likely dissipates energy from the Bransfield Current locally12,43. Therefore, these short reflectors are likely remnants of turbulent patches associated with internal wave breaking.

Intrusion or interleaving is another type of finescale process that may develop pervasively near frontal regions by submesoscale stirring44,45,46. Intrusion-induced T/S inversions are ubiquitous especially in the Antarctic frontal regions16,47,48. CTD profiles reveal that T inversions range from 50‒200 m in vertical scale, but with corresponding faint density inversions because of T-S compensation (Fig. 10). In seismic images, the strongest reflections primarily correspond to the intrusive boundaries with large T gradients associated with frontal dynamics (Fig. 10). Spiciness \(\tau\), a quantitative measure of isopycnal water variation in density unit, is used to investigate intrusions (Fig. 10)49. The kinks on the T-S diagrams indicate that the more spicy TBW (−2.9 kg/m3) intrudes into the less spicy TWW (−3.2 kg/m3) with thick (200 m) single intrusions or medium (50 m) alternating intrusions50. These intrusions vary from upstream (Line W21) to downstream (Line C04) showing the water mass modification: the intrusion thicknesses decrease from ~200 m to 50 m, and the spiciness contrasts between TBW and TWW weaken from 0.3 to 0.1 kg/m3.

Internal wave breaking, overturning stratification due to shear instability, and T-S intrusions provide evidence of turbulent mixing45,51. Thorpe scale \({L}_{T}\), a measure of overturn size, is derived from density profiles (“Methods”; column 3 of Fig. 10). Thorpe scales range from ~100 m to ~10 m, a few factors smaller than T intrusions. Typical Thorpe scales decrease along the Bransfield Current: they are 50 m, 20 m, and 10 m on Lines W21, C09, and C04, respectively. Corresponding diapycnal diffusivities \({K}_{\rho }\) estimated from the Thorpe scales show the same declining trend (column 4 of Fig. 10; “Methods”). The average \({K}_{\rho }\) ranges from 10−2 m2/s to 10−1 m2/s. Such observations of elevated mixing are not unique to the ACC system; previous studies have shown that the peak \({K}_{\rho }\) can reach values as high as 10−2 m2/s or 10+1 m2/s34,52.

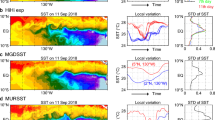

Seismic data are used to estimate diffusivity at the frontal regions based on statistical spectral analysis of the stratified turbulence (Fig. 11; “Methods”)22,38,53. It is evident that (1) elevated mixing is generally distributed at the frontal regions on the TBW side, (2) mixing in the TWW is relatively weak or mostly undetectable, and (3) there is also a systematic decline in mixing along the Bransfield Current from upstream to downstream. The average \({K}_{\rho }\) is 2‒3 × 10−4 m2/s and the peak \({K}_{\rho }\) is over 3 × 10−3 m2/s. These values are 1‒2 orders of magnitude lower than the Thorpe-scale estimates. This discrepancy could be attributed to the use of different parameterization schemes: the Thorpe-scale method measures the extreme mixing caused by overturning, while the seismic method analyzes the isopycnal undulation without overturning. Nevertheless, both results are above the global average diffusivity of 10−4 m2/s54,55, indicating that the Bransfield Current is a region of enhanced mixing in the ocean.

Four diffusivity sections from Lines W21 (a), W14 (b), C09 (c) and C03 (d) show enhanced mixing at the frontal regions, with a gradual decrease in mixing along the Bransfield Current from upstream to downstream. The orange lines indicate the fronts. The orange ellipse on Line C03 in (d) marks a shed submesoscale eddy shown in Fig. 8c.

Figure 12 shows the statistical characteristics of cross-front motion and width for 325 identified high reflection patches (Supplementary Fig. 6). The average horizontal velocity \(v\) is 0.24 ± 0.13 m/s (Fig. 12a), and the average size is 189 ± 37 m (Fig. 12d). Although the trend in mean velocities decreasing from 0.32 to 0.18 m/s with increasing depth is not statistically significant due to large uncertainties (Fig. 12b), this pattern is consistent with the baroclinicity of the Bransfield Current and its associated dynamics. The distribution of the patch sizes with depth is more uniform with only a slight decrease below 600 m depth (Fig. 12e).

Plots of the velocity (a, b, c) and horizontal size (d, e, f) distributions for all reflection patches. Left column: histograms with statistical parameters in the upper-right corners, where <|v | >±σ is the mean velocity and its one standard deviation; N is the population of reflection patches and nσ is the number falling in the ±σ range. The red lines show the mean values (solid) and one standard deviation range (dash). The light blue ranges in (d) show the Ozmidov scale \({L}_{o}\) and the horizontal Coriolis scale \({L}_{f}\), respectively. Middle column: velocity (b) and size (e) distributions with depth. The color represents the distance of each patch to the frontal leading edge. The red dashed curves with error bars are the mean and one standard deviation. Right column: same as the middle column but for the velocity (c) and size (f) distributions with the distance to the frontal leading edge (d2f). The color represents the depth of each patch. The light blue bars and curve in (f) show the histogram and cumulative distribution of the patches with d2f.

The patch velocity and size distributions were investigated with respect to distance from the frontal leading edges (Fig. 12c, f). The highest average velocity (0.27 m/s) occurs at ~5 km from the frontal leading edge, while velocities are relatively smaller at the leading edge ( ~ 0.20 m/s) or ~20 km away (~0.10 m/s) (Fig. 12c), i.e., the maximum cross-front motion is not exactly collocated with the front, consistent with the high-resolution observation of an eddy front in the Southern Ocean56. In contrast, the average size exhibits a gradual decrease with distance from the frontal leading edge. The mean sizes are ~200 m near the leading edge and ~150 m to ~20 km away (Fig. 12f). The stronger stratification near the leading edge may be responsible for this pattern, as it many hinder internal waves breaking. The occurrence of turbulent events follows an exponential decay from the frontal leading edge (Fig. 12f). Over 95% of the patches are located within 10 km of the leading edge, where thermocline variance is higher near the front, and turbulence mixing is enhanced (Fig. 11). The patch velocities and sizes are not correlated (Supplementary Fig. 7). Velocity and size distributions show discrete features with large standard deviations, which may be intrinsic to flow instabilities.

Figure 13a illustrates the horizontal wavenumber spectra of isopycnal slope over the internal waves and stratified turbulence ranges, derived from hydrographic observations at Hawaii Ridge (Fig. 3 of Klymak and Moum9) and seismic observation at Bransfield Strait from this study. Both hydrographic and seismic results confirm spectral characteristics of the transitional stratified turbulence subrange, challenging the classical hypothesis that energy cascades directly from internal wave to isotropic turbulence—a view that has been questioned by recent hydrographic and seismic observations7,8,9,42.

a Isopycnal slope horizontal wavenumber spectrum over the internal wave subrange and anisotropic stratified turbulence subranges (color band). Both the hydrographic results from Fig. 3 of Klymak and Moum (2007) (light blue) and the seismic results from this study (deep blue, a tracked spectrum in the vicinity of the Bransfield Front from Supplementary Fig. 10b) confirm the presence of the stratified turbulence subrange. b Flow dynamics illustrating the prevalence of the stratified turbulence patches towards the frontal leading edge in the Bransfield Strait.

A schematic of the frontal dynamics and observed high reflection patches interpreted as anisotropic stratified turbulence is illustrated in Fig. 13b. The Bransfield Current system consists of a swift main current and shedding mesoscale and submesoscale eddy features. Under such an energetic environment, turbulent patches, including stratified segments, interleaving interfaces, and overturns, are developed by various mechanisms, such as shear instability, internal wave breaking, and interaction with topography. These patches may highly draw kinetic energy from larger scales to obtain instantaneous speeds that may exceed the main current. In the cross-frontal direction, our seismic data revealed: (1) high reflective patches, presumed to be stratified turbulence, are directly imaged; (2) their horizontal scales are between internal waves and isotropic turbulence; (3) they are unevenly distributed, mostly close to the frontal leading edge; (4) the fastest patches occur sporadically not at the leading edge but ~5 km away ; (5) the larger size events are more likely to occur near the leading edge; and (6) the discrete distribution pattern of the velocity magnitude may indicate the intrinsic nature of unstable, turbulent events.

Methods

Legacy seismic data and processing

Reflection seismic data were acquired during the seismic cruise EW9101 in the austral summer in February 1991 aboard the R/V Maurice Ewing57. Among them, 17 sections traversing the Bransfield Strait covering the western, central, and eastern sub-basins are re-analyzed to image the water column finestructure (Fig. 1). Here, the sections are re-labeled as the combination of the first letters of the basin name and the line number, e.g., C04 represents Line 04 in the central basin. The ship steamed at 5 knots and carried a seismic source (airgun array) with a total capacity of 8385 cu. in. (137 L) fired every 20 s for ~50 m shot interval. The receiver cable is comprised of 120 channels with 25-m channel spacing and the nearest-channel offset is 250 m. The data sampling rate is 0.004 s. The parameter settings result in spatial sampling intervals of 12.5 m laterally and 3.0 m vertically, along with a shallow blind zone of ~100 m in seismic images.

Seismic data are processed with an 8-step sequence: geometry definition, trace edit, noise attenuation, common midpoint sorting, acoustic velocity analysis, normal moveout, stacking, and migration23. The trace edit is mandatory because some shots or channels are missing and some shots have extra channels. Stacking velocity is determined using a constant velocity scan scheme based on flattening the reflection hyperbolas at the flat seafloor. The obtained optimal acoustic velocity is 1460 m/s, which is close to the hydrographic measurements ranging 1450–1465 m/s.

Seismic reflections are the result of the convolution of acoustic impedance (the product of acoustic velocity and density) gradients with the source wavelet. These reflections correspond to stratification layers within the ocean58. Because water reflectivities are controlled by T and S, the reflections in seismic images are interpreted as approximations of the vertical T/S changes58. In the study region, using the local T, S, and mean density ratio of \({R}_{\rho } \sim 0.3\) (Supplementary Table 1), the inferred relative T contributions to acoustic speed and reflectivity are ~79% and 66%, respectively58,59. Thus, T is the dominant factor for the seismic reflection and is a suitable water mass tracer in the Bransfield Strait16,17.

Reflection patch motion estimation

An improved scheme is designed to compute the velocity of high reflection patches based on previous works23,34,36. The basic principle is to track the reflection patches captured by each shot repeatedly within a time window of 3‒4 min while the ship is passing over it. Here, the ship’s speed of 5 knots must be removed first23. In this study the instantaneous amplitude or envelope of the reflection, which relates to the reflection energy of a patch, is used to track its motion. The envelope is more stable than the reflection itself and thus it is easier to track its energy center. The estimated velocities are close to the theoretical values. Please refer the synthetic modeling of the seismic imaging for the moving patches (Supplementary Fig. 8) and their velocity estimation (Supplementary Fig. 9) in Supplementary Note 6.

CTD data, water properties, and Thorpe-scale diffusivity

Historical CTD profiles from World Ocean Database 2018 (WOD18; https://www.ncei.noaa.gov) are collected to show the fundamental water properties in the study region. The data from January and April and within the spatial bounds of (54°–64°W, 61°–65°S) were selected to better represent water properties during the seismic survey in austral summer. From CTD profiles, the average T-S for TBW and TWW, potential density \(\sigma\) and spiciness \(\tau\), and synthetic seismographs are derived (Fig. 10 and Supplementary Figs. 4 and 5). Here, synthetic seismographs are computed by convolving impedance contrasts, defined as the vertical differences of the product of acoustic velocity and density, with a Ricker wavelet with a central frequency of 50 Hz. The Thorpe scale \({L}_{T}\) is computed as the RMS vertical isopycnal displacement to characterize overturning scales33. Turbulent diffusivity \({K}_{\rho }\) is derived using the relation:

where \(\varGamma =0.2\) is the mixing efficiency, \(N\) is the local buoyancy frequency60,61. The Thorpe-scale method performs well in Drake Passage where overturns are strongly developed, and it should be applicable in the Bransfield Strait with weak stratification and high mixing61,62.

Two additional scales, the Ozmidov scale \({L}_{o}\) and the horizontal Coriolis scale \({L}_{f}\) are derived:

where \({L}_{f}\) represents the horizontal transition scale from internal wave to stratified turbulence7, and the Ozmidov scale \({L}_{o}\) denotes the upper bound of isotropic turbulence, by taking the typical \({K}_{\rho }\) = 10−2‒10−1 m2/s from Eq. (1). The stratified turbulence is likely to occur within the range between \({L}_{f}\) and \({L}_{o}\) (Supplementary Table 1)10,63.

Geostrophic velocity and Rossby number

Geostrophic velocity \({U}_{g}\) is estimated using the thermal wind equation64,65, with a known frontal slope \({\rm{\alpha }}\):

Here, the density difference \(\Delta \rho\) between TWW and TBW from both WOD18 data and the paper by Sangrà et al.18 are used to derive the geostrophic velocity.

We also applied a mass conservation scheme to estimate the main current velocity \({U}_{m}\) across each seismic section by using the average velocity \(U\) of 0.35 m/s (Supplementary Table 1):

We assume that the volume transport of the Bransfield Current is unchangeable, i.e.,

where \({U}_{i}\) is the velocity on the \(i\) th section and \({A}_{i}\) is the cross-sectional area of the main current measured from the seismic images (Fig. 3). From Eqs. (4) and (5), we get

Then, the Rossby number \({R}_{o}\) is derived using

where \(L\) is the reflection-estimated width of the Bransfield Current on each section.

Vertical extent prediction of the Bransfield Front

The bottom depth \(h\) for the Bransfield coastal gravity current can be predicted from scaling theory66,67 as

where \(\rho =1027\,{\rm{kg}}/{{\rm{m}}}^{3}\) is the background density, \(U=0.35\,{\rm{m}}/{\rm{s}}\) is the mean current velocity, \(A=4.9\pm 0.3\,{\rm{k}}{{\rm{m}}}^{2}\) is the mean cross-sectional area from Lines C02‒C11, \(g\) is the gravitational acceleration, and \(\Delta \rho =0.09\,{\rm{kg}}/{{\rm{m}}}^{3}\) is the density difference from Sangrà et al.18. The estimated vertical extent \(h\) is 720 ± 26 m.

Vertical velocity estimation of the Bransfield Front

The first-order vertical velocity \(w\) of upwelling (−) or downwelling (+) is estimated based on the continuity equation, with a coordinate of the x axis aligned along the front (\(u\)) and the y axis oriented across the front (\(v\)):

If we assume the front is stable, i.e., \(\frac{{\partial }_{v}}{{\partial }_{y}}=0\), then Eq. (9) gives

where \(\Delta z=200\) m is the depth change, and \(\Delta x=87\) km is the length of the current between C09‒C0539, and \(u=U=0.35\) m/s is the mean current velocity. The second way is from the kinematic aspect that the base of the current ascends or descents \(\Delta z\) within the spatial range of \(\Delta x\). Since the time \(\frac{\Delta x}{u}\) for the horizontal current flow in distance \(\Delta x\) equals the time \(\frac{\Delta z}{w}\) for the vertical current motion, thus we get the same relation in Eq. (10).

Turbulent diffusivity spectral estimation

The turbulent diapycnal diffusivity \({K}_{\rho }\) can be derived from horizontal wavenumber spectra of isopycnal slope \({\zeta }_{x}\) using seismic data, under the following assumptions: (a) tracked seismic reflectors follow isopycnals; (b) the horizontal wavenumber spectra of isopycnal displacement exhibit a canonical shape in the stratified turbulence regime; and (c) stratified turbulence is in statistical equilibrium with the small-scale dissipation22,53. This approach was first introduced by Sheen et al.22 for quantifying turbulence from seismic data, following a similar oceanographic method developed by Klymak and Moum68 for analyzing horizontally towed vertical isopycnal displacement data. Here, a seismic reflection tracking scheme is applied to estimate \({K}_{\rho }\) by calculating the slope spectrum \({\varphi }_{{\zeta }_{x}}^{T}\) within the stratified turbulence regime from the tracked reflections, using the following the relation22,53,60,69:

where \({\varphi }_{{\zeta }_{x}i}^{T}\) is the \(i\) th slope spectrum value corresponding to wavenumber \({k}_{x}^{i}\) within the turbulence subrange, \(M\) is the number of \({k}_{x}^{i}\) in the selected turbulence subrange, \(b\) is the intercept of the linear fit on the spectrum energy axis, \({C}_{T}=0.4\) is the Obukhov–Corrsin constant70, \({\sigma }_{b}\) is the standard deviation of the residuals from the fit, representing the uncertainty in the linear fitting, \({\varepsilon }^{\pm }\) denote the upper and lower bounds of the dissipation rates corresponding to \({b\pm \sigma }_{b}\). In this study, the wavenumber extents of the turbulence subrange \({k}_{x}\in [0.006,0.025]{{\rm{m}}}^{-1}\) is determined from spectral shape changes (Supplementary Fig. 10).

Data availability

The full seismic data and hydrographic data are available at the Marine Geoscience Data System (MGDS) (EW9101; www.marine-geo.org/tools/entry/EW9101, https://doi.org/10.7284/901261) and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) (WOD18; www.ncei.noaa.gov/products/world-ocean-database). For inquiries related to data or code materials, please direct your request to J.L. or Q.T.

References

McWilliams, J. C. Submesoscale currents in the ocean. Proc. R. Soc. A-Math. Phys Eng. Sci. 472, 20160117 (2016).

Taylor, J. R. & Thompson, A. F. Submesoscale dynamics in the upper ocean. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 55, 103–127 (2023).

Buckingham, C. E. et al. The contribution of surface and submesoscale processes to turbulence in the open ocean surface boundary layer. J. Adv. Model Earth Syst. 11, 4066–4094 (2019).

D’Asaro, E., Lee, C., Rainville, L., Harcourt, R. & Thomas, L. Enhanced turbulence and energy dissipation at ocean fronts. Science 332, 318–322 (2011).

Zhang, Z. et al. Submesoscale inverse energy cascade enhances Southern Ocean eddy heat transport. Nat. Commun. 14, 1335 (2023).

Naveira et al. Kinetic energy transfers between mesoscale and submesoscale motions in the open ocean’s upper layers. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 52, 75–97 (2022).

Kunze, E. A unified model spectrum for anisotropic stratified and isotropic turbulence in the ocean and atmosphere. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 49, 385–407 (2019).

Riley, J. J. & Lindborg, E. Stratified turbulence: a possible interpretation of some geophysical turbulence measurements. J. Atmos. Sci. 65, 2416–2424 (2008).

Klymak, J. M. & Moum, J. N. Oceanic isopycnal slope spectra. Part II: turbulence. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 37, 1232–1245 (2007).

Falder, M., White, N. & Caulfield, C. Seismic imaging of rapid onset of stratified turbulence in the South Atlantic Ocean. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 46, 1023–1044 (2016).

Hofmann, E. E., Klinck, J. M., Lascara, C. M. & Smith, D. A. Water mass distribution and circulation west of the Antarctic Peninsula and including Bransfield Strait. In Foundations for Ecological Research West of the Antarctic Peninsula Ross (eds Hofmann, E. E. & Quetin, L. B.) 61–80 (American Geophysical Union, 1996).

Sangrà, P. et al. The Bransfield current system. Deep Sea Res. Part I 58, 390–402 (2011).

Huneke, W. G. C., Huhn, O. & Schröeder, M. Water masses in the Bransfield Strait and adjacent seas, austral summer 2013. Polar Biol. 39, 789–798 (2016).

Zhou, M., Niiler, P. P., Zhu, Y. & Dorland, R. D. The western boundary current in the Bransfield Strait, Antarctica. Deep Sea Res. Part I 53, 1244–1252 (2006).

Savidge, D. K. & Amft, J. A. Circulation on the West Antarctic Peninsula derived from 6 years of shipboard ADCP transects. Deep Sea Res. Part I 56, 1633–1655 (2009).

Amos, NiilerP. P. & Hu, A. J.H. Water masses and 200 M relative geostrophic circulation in the western Bransfield Strait region. Deep-Sea Res. Pt I 38, 943–959 (1991).

López, O. et al. Hydrographic and hydrodynamic characteristics of the eastern basin of the Bransfield Strait (Antarctica). Deep Sea Res. Part I 46, 1755–1778 (1999).

Sangrà, P. et al. The Bransfield gravity current. Deep Sea Res. Part I 119, 1–15 (2017).

Gunn, K. L., White, N. & Caulfield, C.-cP. Time-lapse seismic imaging of oceanic fronts and transient lenses within South Atlantic Ocean. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 125, e2020JC016293 (2020).

Holbrook, W. S., Paramo, P., Pearse, S. & Schmitt, R. W. Thermohaline fine structure in an oceanographic front from seismic reflection profiling. Science 301, 821–824 (2003).

Pinheiro, L. M. et al. Detailed 2-D imaging of the Mediterranean outflow and meddies off W Iberia from multichannel seismic data. J. Mar. Syst. 79, 89–100 (2010).

Sheen, K. L., White, N. J. & Hobbs, R. W. Estimating mixing rates from seismic images of oceanic structure. Geophys. Res. Lett. 36, L00D04 (2009).

Tang, Q. et al. Marine seismic observation of internal solitary wave packets in the northeast South China Sea. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 120, 8487–8503 (2015).

Tang, Q., Tong, V. C. H., Hobbs, R. W. & Morales Maqueda, M. Á. Detecting changes at the leading edge of an interface between oceanic water layers. Nat. Commun. 10, 4674 (2019).

Fer, I., Nandi, P., Holbrook, W. S., Schmitt, R. W. & Paramo, P. Seismic imaging of a thermohaline staircase in the western tropical North Atlantic. Ocean Sci. 6, 621–631 (2010).

Nakamura, Y. et al. Simultaneous seismic reflection and physical oceanographic observations of oceanic fine structure in the Kuroshio extension front. Geophys. Res. Lett. 33, L23605 (2006).

Yang, S., Song, H., Coakley, B., Zhang, K. & Fan, W. A mesoscale eddy with submesoscale spiral bands observed from seismic reflection sections in the Northwind Basin, Arctic Ocean. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 127, e2021JC017984 (2022).

Gunn, K. L., White, N. J., Larter, R. D. & Caulfield, C. P. Calibrated seismic imaging of eddy-dominated warm-water transport across the Bellingshausen Sea, Southern Ocean. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 123, 3072–3099 (2018).

García-Muñoz, C. et al. A mesoscale study of phytoplankton assemblages around the South Shetland Islands (Antarctica). Polar Biol. 36, 1107–1123 (2013).

Thompson, A. F., Heywood, K. J., Thorpe, S. E., Renner, A. H. H. & Trasviña, A. Surface circulation at the tip of the Antarctic Peninsula from drifters. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 39, 3–26 (2009).

Gordon, A. L., Mensch, M., Zhaoqian, D., Smethie, W. M. Jr & de Bettencourt, J. Deep and bottom water of the Bransfield Strait eastern and central basins. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 105, 11337–11346 (2000).

Capella, J. E., Ross, R. M., Quetin, L. B. & Hofmann, E. E. A note on the thermal structure of the upper ocean in the Bransfield Strait-South Shetland Islands region. Deep Sea Res. Part I 39, 1221–1229 (1992).

Thorpe, S. A. The Turbulent Ocean (Cambridge University Press, 2005).

Sheen, K. L., White, N. J., Caulfield, C. P. & Hobbs, R. W. Seismic imaging of a large horizontal vortex at abyssal depths beneath the Sub-Antarctic Front. Nat. Geosci. 5, 542–546 (2012).

Klaeschen, D., Hobbs, R. W., Krahmann, G., Papenberg, C. & Vsemirnova, E. Estimating movement of reflectors in the water column using seismic oceanography. Geophys. Res. Lett. 36, L00D03 (2009).

Tang, Q., Wang, C. X., Wang, D. X. & Pawlowicz, R. Seismic, satellite, and site observations of internal solitary waves in the NE South China Sea. Sci. Rep. 4, 5374 (2014).

Dickinson, A., White, N. J. & Caulfield, C. P. Spatial variation of diapycnal diffusivity estimated from seismic imaging of internal wave field, Gulf of Mexico. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 122, 9827–9854 (2017).

Tang, Q., Jing, Z., Lin, J. & Sun, J. Diapycnal mixing in the sub-thermocline at the Mariana Ridge from high-resolution seismic images. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 51, 1283–1300 (2021).

Lindborg, E. The energy cascade in a strongly stratified fluid. J. Fluid Mech. 550, 207–242 (2006).

Portwood, G. D., de Bruyn Kops, S. M., Taylor, J. R., Salehipour, H. & Caulfield, C. P. Robust identification of dynamically distinct regions in stratified turbulence. J. Fluid Mech. 807, R2 (2016).

Brethouwer, G., Billant, P., Lindborg, E. & Chomaz, J. M. Scaling analysis and simulation of strongly stratified turbulent flows. J. Fluid Mech. 585, 343–368 (2007).

Vladoiu, A., Lien, R.-C. & Kunze, E. Two-dimensional wavenumber spectra on the horizontal submesoscale and vertical finescale. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 52, 2009–2028 (2022).

Dragani, W. C., Drabble, M., D’Onofrio, E. & Mazio, C. A. Propagation and amplification of tide at the Bransfield and Gerlache Straits, northwestern Antarctic Peninsula. Polar Geosci. 17, 156–170 (2004).

Ruddick, B. & Kerr, O. Oceanic thermohaline intrusions: theory. Prog. Oceanogr. 56, 483–497 (2003).

Hebert, D. Intrusions: what drives them? J. Phys. Oceanogr. 29, 1382–1391 (1999).

Schmitt, R. W. Double-diffusive convection. In Encyclopedia of Ocean Sciences, 2 edn. (eds Steele, J. H. et al.) 162–170 (Academic Press, 2009).

Golovin, P. N., Antipov, N. N. & Klepikov, A. V. Intrusive layering of the Antarctic slope front. Oceanology 56, 470–482 (2016).

Toole, J. M. Intrusion characteristics in the Antarctic Polar Front. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 11, 780–793 (1981).

McDougall, T. J. & Krzysik, O. A. Spiciness. J. Mar. Res. 73, 141–152 (2015).

Shcherbina, A. Y., Gregg, M. C., Alford, M. H. & Harcourt, R. R. Characterizing thermohaline intrusions in the North Pacific subtropical frontal zone. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 39, 2735–2756 (2009).

Gregg, M. C., Sanford, T. B. & Winkel, D. P. Reduced mixing from the breaking of internal waves in equatorial waters. Nature 422, 513–515 (2003).

Naveira Garabato, A. C., Polzin, K. L., King, B. A., Heywood, K. J. & Visbeck, M. Widespread intense turbulent mixing in the Southern Ocean. Science 303, 210–213 (2004).

Holbrook, W. S. et al. Estimating oceanic turbulence dissipation from seismic images. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 30, 1767–1788 (2013).

Munk, W. & Wunsch, C. Abyssal recipes II: energetics of tidal and wind mixing. Deep-Sea Res. Pt I 45, 1977–2010 (1998).

Waterhouse, A. F. et al. Global patterns of diapycnal mixing from measurements of the turbulent dissipation rate. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 44, 1854–1872 (2014).

Adams, K. A. et al. Frontal circulation and submesoscale variability during the formation of a Southern Ocean mesoscale eddy. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 47, 1737–1753 (2017).

Barker, D. H. N. & Austin, J. A. Jr. Rift propagation, detachment faulting, and associated magmatism in Bransfield Strait, Antarctic Peninsula. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 103, 24017–24043 (1998).

Ruddick, B., Song, H. B., Dong, C. Z. & Pinheiro, L. Water column seismic images as maps of temperature gradient. Oceanography 22, 192–205 (2009).

Sallares, V. et al. Relative contribution of temperature and salinity to ocean acoustic reflectivity. Geophys. Res. Lett. 36, L00D06 (2009).

Osborn, T. R. Estimates of the local-rate of vertical diffusion from dissipation measurements. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 10, 83–89 (1980).

Yang, Q., Zhao, W., Li, M. & Tian, J. Spatial structure of turbulent mixing in the northwestern Pacific Ocean. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 44, 2235–2247 (2014).

Frants, M. et al. An assessment of density-based finescale methods for estimating diapycnal diffusivity in the Southern Ocean. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 30, 2647–2661 (2013).

Avsarkisov, V. On the buoyancy subrange in stratified turbulence. Atmosphere 11, 659 (2020).

Stewart, R. H. Introduction to Physical Oceanography (Department of Oceanography, Texas A & M University, 2008).

Sheen, K. L., White, N., Caulfield, C. P. & Hobbs, R. W. Estimating geostrophic shear from seismic images of oceanic structure. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 28, 1149–1154 (2011).

Lentz, S. J. & Helfrich, K. R. Buoyant gravity currents along a sloping bottom in a rotating fluid. J. Fluid Mech. 464, 251–278 (2002).

Yankovsky, A. E. & Chapman, D. C. A simple theory for the fate of buoyant coastal discharges. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 27, 1386–1401 (1997).

Klymak, J. M. & Moum, J. N. Oceanic isopycnal slope spectra. Part I: internal waves. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 37, 1215–1231 (2007).

Tang, Q., Jing, Z., Li, J. & Sun, J. Enhanced diapycnal mixing in the deep ocean around the island of Taiwan. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 127, e2021JC018034 (2022).

Sreenivasan, K. R. The passive scalar spectrum and the Obukhov–Corrsin constant. Phys. Fluids 8, 189–196 (1996).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the captain, crew, and science party of the R/V Maurice Ewing cruise EW9101 for acquiring the seismic data under such an extreme maritime environment in the polar region. We sincerely appreciate the constructive comments and detailed suggestions from two anonymous reviewers. We also thank the Marine Geoscience Data System (MGDS) and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) for sharing the seismic and hydrographic data. This study is supported by NSFC (42274067 and 42225602), Key Research and Development Program of Zhejiang (2025C02019), and Science Foundation of Donghai Laboratory (DH2022ZY0001).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors conceived and developed the scientific case. Q.T. and J.L. processed the seismic and hydrographic data. Q.T. wrote the manuscript with guidance from W.X., Z.J., and V.C.H.T.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tang, Q., Lin, J., Xu, W. et al. Intensifying stratified turbulence and mixing towards the oceanic submesoscale front. npj Clim Atmos Sci 8, 178 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-01069-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-01069-x