Abstract

Spaceborne synthetic aperture radar (SAR) is a microwave sensor that captures tropical cyclones (TCs) with high spatial resolution. Based on three idealized TC parametric wind models, we provide a comprehensive perspective on TC studies using SAR observations, including surface winds, morphology, eye shape, asymmetry, inflow angle, steering flow, secondary eyewalls, vortex Rossby waves, spatial rain bands, and other small-scale dynamics, contributing to a better understanding of TC movement and intensification.

Similar content being viewed by others

Advances in spaceborne SAR for tropical cyclone monitoring

The main advantages of SAR TC monitoring are the high spatial resolution and direct estimation of surface winds1,2,3,4,5 (Supplementary Fig. 1). Early spaceborne SAR systems, such as ERS-1, ERS-2, and RADARSAT-1, were limited to providing single-polarized SAR images using either HH or VV polarization. These images allowed for TC center locating, size measurements6, and intensity estimation7. However, due to the tendency for HH and VV signals to saturate under TC conditions, they have limited use in TC wind retrievals. Since the launch of RADARSAT-2 in 2008, multi-polarization SAR including four linear polarizations of co-polarizations (VV or HH) and cross-polarizations (VH or HV) has been available. Compared to the co-polarizations, the cross-polarized SAR images are expected to remain unsaturated, suitable for capturing TC winds8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15. In the last decade, two Sentinel-1 (2014/2016), three Gaofen-3 (2016/2021/2022), and three RCM (RADARSAT Constellation Mission, 2019) satellites were launched, all having C-band cross-polarized SAR imaging ability. The relationship between sea surface wind speed and the C-band cross-polarized SAR signal of NRCS (Normalized Radar Cross-Section) has been investigated, and sea surface wind retrieval methods or models have been developed8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15 (Table 1). Recently, NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration) STAR (Center for satellite applications and Research) has worked with Joint Typhoon Warning Center (JTWC), Naval Research Laboratory, and National Hurricane Center to provide the retrieved wind products, radial wind profiles, maximum wind speed, radius of maximum winds, and the wind radii of the 34, 50, and 64 kt covering SAR satellites of RADARSAT-2, Sentinel-1, and RCM16,17,18,19,20. Spaceborne SAR has also been used by JTWC for both post-storm best-track (BT) adjustments and real-time analysis and forecasting in conjunction with radiometers20. SAR operational use is still limited to basic measurements. A notable range of studies have attempted to explore the diverse information contained in high spatial resolution wind structures1,5,21,22,23,24,25,26,27. However, there is still a need for a comprehensive integration of such high-resolution parameters into a consistent system suited for operational use.

Remote sensing is the primary method for monitoring TCs over the open ocean, utilizing cloud images from geostationary satellites in the visible (Vis) and infrared (IR) bands, aircraft reconnaissance with Stepped-Frequency Microwave Radiometer (SFMR), and satellite microwave sensors, including SAR, scatterometers, and radiometers for sea surface wind retrieval. Vis and IR satellite images remain the primary source of information for estimating TC intensity in operational forecasting using the Dvorak and similar techniques28,29,30,31,32,33 and exhibit a negligible bias of 0.33 hPa and a root-mean-square error (RMSE) of 8.34 hPa (by central pressure)30. In the North Atlantic and East Pacific basins, aircraft are flown into TCs to obtain measurements, with each profile of the TC vortex typically taking several hours to collect. These airborne measurements, such as those obtained with SFMR and GPS dropwindsondes, provide valuable insights into hurricane structure and small-scale processes along the airplane flight track34,35, including parametric model development36,37 and convective updraft studies38,39,40. These SFMR winds have been validated by measurements from GPS dropsonde with a bias and RMSE of 2.3 m/s and 3.3 m/s, respectively41,42,43,44, while the dropsonde/SFMR wind comparisons are significantly affected by the layer altitude and thickness42. Spaceborne scatterometers and radiometers are effective tools for monitoring, measuring, and studying TCs over the open ocean. These sensors have about 1000 km of swath width with spatial resolutions between 12.5 km to 25 km with a bias and RMSE of 0.8 m/s and 7.8 m/s, respectively45. Previous studies45,46,47,48,49 have demonstrated their usefulness in this regard. Spaceborne SAR can directly retrieve the surface winds with high spatial resolution about 1 km (Supplementary Fig. 2). Here, we present a range of algorithms designed to extract features from SAR-estimated surface wind fields, including signatures related to TC movement and intensification. These features encompass environmental parameters (steering flow speed and direction), internal processes (vortex Rossby waves), and structural vortex properties (size, inflow angle, and wind direction).

In the past decade, research on SAR for TC research and forecasting has had noteworthy advances in two key areas. First, studies utilizing composite Bragg theory and non-Bragg scattering mechanisms have explored semi-empirical models for sea surface winds50, currents51, waves52, and rain53 from multi-polarized SAR images54. While these studies provide valuable insights, achieving simultaneous retrieval of all these meteorological parameters remains a future prospect. Hwang et al.50 investigated multi-polarized (VV/HH/HV/VH) radar signals (NRCS) backscattered from sea surface waves under various wind conditions and concluded that wave breaking significantly influences SAR wind monitoring. Kudryavtsev et al.51 analyzed VV and HH polarizations using RADARSAT-2 SAR images, demonstrating that sea surface current signatures are predominantly related to non-Bragg backscatter. Hwang (2016)52 proposed an empirical formula, the wind-wave triplets, linking sea surface winds, significant wave height, and dominant wave period. Zhang et al.53 investigated five mechanisms for rain’s impact on C-band dual-polarized (VV/VH) SAR channels and suggested that rain-induced effects on sea surface wind waves are critical for SAR hurricane monitoring. Zhang et al.54 developed a semi-empirical model incorporating winds, rain, internal waves, and currents for compact-polarimetry (CP) SAR, concluding that CV (circular transmit and vertical receive) polarization is better suited for TC monitoring than CH (circular transmit and horizontal receive) polarization. The transmitter of a general CP mode is in either circular mode or orientated at 45° (π/4), and receivers at both H (horizontal) and V (vertical) polarizations55. Rain rate estimation from SAR imagery using AI methods have also been quantified by Mu et al.56 and Colin & Husson (2025)57. Additionally, the noise floor (or noise-level equivalent) does not exhibit a functional dependence on sea surface wind conditions and therefore demonstrates no quantitative impact on the uncertainty of sea surface wind retrieval. Three critical aspects require clarification: (1) The noise floor parameters are incorporated as intrinsic components within SAR data products, exhibiting spatial variability across the image grid with distinct values assigned to individual pixels. (2) Wind retrieval validity depends on the comparative relationship between normalized radar cross-section (NRCS) and noise floor measurements: NRCS values exceeding the noise floor threshold permit reliable wind retrieval, whereas instances where the noise floor surpasses the NRCS render the data unsuitable for wind estimation. (3) Systematic accounting for noise floor effects commenced in 2010 following the seminal discovery by Vachon and Wolfe (2010)8, who first identified the quasi-linear relationship between cross-polarized NRCS measurements and wind speed parameters. Secondly, by utilizing data from multiple satellites and various SAR images, researchers have conducted in-depth studies on the structure and evolution of tropical cyclones1,2,5,23,24,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69. Katsaros et al.58 detected TC rain bands coupled with possible boundary layer rolls from Radarsat-1 SAR images. Based on 83 SAR images covering TC core area from RADARSAT-1 and ENVISAT, Li et al.1 studied TC morphology of eye structure, meso-vortices, rainbands, and winds. Zhang and colleagues (2014; 2018)2,59 proposed SAR TC parameter estimation methods for double-eye structure and identified a pathway in the secondary eyewall that explained the dynamic processes of the abnormal eyewall replacement cycle (ERC). Zhang et al.5,60,61 developed SAR TC parametric models for elliptical eyewall, asymmetry and inflow angle structures to study the relationship between TC structural main properties and their intensity. Recently, new approaches, methods, and parameters have been developed to explore the potential of SAR images for TC intensity studies23,24,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69. Foster et al.62 proposed a method to determine TC surface pressures from SAR images. Vinour et al.23,63 analyzed TC vortex parameters, including Vmax, radius of maximum wind (RMW), radial profiles, and eye and RMW shapes, as well as newly designed parameters for characterizing TC contraction and asymmetry from high-resolution SAR data. These studies further assess the relationship between SAR-derived features and TC intensity evolution. Moore Torres et al.64 analyzed the morphologies of TC eye structures and gathered intensity information. Avenas et al. (2023) re-estimated TC RMW by more information than wind speed structure directly from SAR65. Avenas et al.66 compared the TC energy from SAR to structure parameters of Holland Bs and RMW and concluded a good relationship between SAR-derived structure parameters and TC intensity66. SAR-derived TC wind speeds have been compared with conventional Best Track (BT) data67, and RMWs derived from SAR and IR images have been compared68. Yurchak24. developed a new method to estimate TC intensity associated with spiral signatures from SAR24. Zheng et al.69 investigated the probability of rainbands in SAR images and found it would be related to morning/evening and TC intensity69,70. Using spaceborne SAR has opened a new avenue for studying TCs over the open ocean. Our perspective details the measurements taken by SAR for TC remote sensing over ocean, including asymmetric vortex structures, and TC dynamics in small-scale. These measurements are vital for comprehending and predicting TC movement and intensity evolution.

Asymmetric vortex and TC movement

TC movement understanding and forecasting is a foundation, because a perfect forecast of intensity and size is meaningless when the location of the TC is inaccurate. The most important factor to ‘steer’ TC is supposed to be the large-scale flow surrounding the TC vortex, which is also denoted as ‘steering flow’71,72,73,74,75,76,77. The wind asymmetry induced by steering flow related to movement has been investigated and modeled61,72,73. In parametric wind models73,78,79,80,81,82,83, the surrounded large-scale flow is assumed as a unified background wind vector and linearly related to the TC movement. This unified background vector is used as an important parameter in storm surge modeling and is referred to as the TC’s forward velocity at the surface.

Following the above studies, a SHEW-2 model has been proposed to derive the unified background wind vector (unified steering flow) associated with the inflow angle asymmetry61. This model for background wind vector determination from SAR TC winds has been developed by using a dataset of 130 SAR TC images across various hurricane categories from RADARSAT-2 and SENTINEL-1. The composed results of 130 SAR-winds show the asymmetrical vortex induced by a unified background vector represents the major part of TC asymmetry61. The details of SHEW-2 model are presented in the Method section.

As an example, the procedure is illustrated using a SAR wind field over Hurricane Teddy in Fig. 1. The ocean surface wind speeds retrieved from C-band VH-polarized SAR images of RADARSAT-2 are shown in Fig. 1b. The reconstructed TC surface winds by using the SHEW-2 model are fitted to the SAR-derived ocean wind field using the least square method, resulting in the asymmetric wind field and associated wind vectors displayed in Fig. 1c, and the surface background wind vector and symmetrical wind field shown in Fig. 1d. Here, TC movement information is estimated from SAR observations directly. Therefore, we get the best-fitted inflow angle asymmetry and TC movement information (the surface background wind vector) from SAR observations. We want to denote that only the wind speed field estimated by SHEW-2 model is used during the fitting process. SHEW-2 model simulates a wind vector field, which includes wind speed field, wind direction and inflow angle fields. When the wind speed field is fixed, the other two fields of wind direction and inflow angle will also be fixed. In other words, the inflow angles are detected by SHEW-2 model associated with the wind speed fitting process. The obtained surface background wind vector is also compared to the BT data, revealing that the SAR-derived background wind direction is similar to the movement of the TC from the BT database with a bias of 27.9o. The discrepancies between SAR estimates and BT data primarily arise from two factors: (1) SAR captures surface wind dynamics influenced by planetary boundary layer friction, while BT data represent free-tropospheric flow patterns, and (2) asynchronous observation timing between the two datasets. In reality, the ‘steering flow’ is more complicated than just a unified background wind vector. For example, the movement of the long-lived Cyclone Freddy in 2023 lasted 35 days, one of the most remarkable storms in history, was poorly predicted, likely due to factors such as the influence of the subtropical high, TC size, and interactions between two TCs84. Figure 2 presents a synergistic analysis of Cyclone Freddy’s surface wind structure derived from SAR and the associated steering flow vectors (background wind vectors) from the SHEW-2 model. The steering flow around Freddy likely did not remain static as the Mascarene High (subtropical high) strengthened or weakened84. This highlights the importance of real-time observations by SAR, which can capture critical movement-related factors such as steering flow, inflow angle asymmetry, and TC size. These observations remain vital for advancing the understanding and forecasting of TC behavior. Furthermore, in complex scenarios, multiple steering flows may better explain TC movement than a single unified flow. Therefore, in the future, the high spatial resolution SAR-winds have the potential to study the relationships between the complicated steering flows and TC movement.

a best track and the respective position of SAR winds acquired at 10:05 UTC on September, 2020 over Hurricane Teddy (2020), (b) high spatial resolution winds derived from SAR image, (c) the reconstructed asymmetric wind field and associated wind vectors at the surface level and (d) the estimated background wind vector (white arrows) related to TC movement and the symmetric vortex.

Small-scale patterns and TC intensification

Vortex Rossby-waves (VRWs) often play an important role in upscaling energy transfer from the TC asymmetrical structure to the TC vortex mean flow85,86,87,88. Analogous to the dynamics of rotating fluid systems observed in Earth’s atmosphere or ocean that are capable of impacting planetary-scale atmospheric and/or oceanic processes89, a TC is also a rotating fluid system. Therefore, wave patterns like the Rossby waves have been detected in TCs, which are denoted as ‘Rossby-like waves’90 or ‘vortex Rossby waves’ (VRWs)85,91. VRWs have been detected in typhoon spiral rainbands90, but have been simulated numerically in wind fields85. The radial wavelengths of the possible VRW bands are suggested on the order of 10 km to 20 km92. By comparison, the boundary layer rolls may have some similarity to VRWs but are sub-kilometer scale93,94,95.

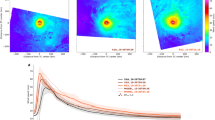

Here, we take Hurricane Vance (2014) as an example (Fig. 3), the spiral rainbands in the upper level of the troposphere suggest the presence of VRWs (Fig. 3i). The VRWs are analyzed in the azimuth-radial distribution of residual winds (Fig. 3f), which are computed by removing the symmetric mean vortex (Fig. 3c) by using the SHEW model detailed in the Method. The wave features in the residual wind field are indicated by the black dashed line in Fig. 3f, as well as similar features along the radius. We apply a fast Fourier transform (FFT) to the residual wind speed along the black dashed line. The peak FFT powers are associated with wave features that have horizontal scales of 12.22 km, 15.71 km and 18.33 km, which are consistent with the model results (Fig. 3h). In order to understand the radially outward-propagating waves in spiral bands, A ‘simplest’ dynamic model has been chosen for simulating VRWs excited by the azimuthal wind asymmetry85. Using the TC vortex parameters of intensity and RMW extracted from SAR-derived winds; while retaining values for the other parameters that are the same as ref. 85, we simulate the perturbation azimuthal wind speeds of the VRWs along the radius for Hurricane Vance (Fig. 3g).

a TC intensity from best track (BT), (b) storm-centered SAR-derived wind field within 150 km from RADARSAT-2 VH-polarized ScanSAR image acquired at 01:12 UTC on 2 November, (c) reconstructed symmetric mean flow of (b), (d) & (e) same as (b) & (c) but acquired at 13:11 UTC on 3 November, 2014, (f) Azimuth-radius plot of the residual wind speed obtained by removing Fig. 3c from Fig. 3b and azimuth-radius distribution of the residual wind speed with horizontal resolution of 1 km and azimuthal resolution of 2 degrees, (g) Radial wind profiles of SAR detection along the dash line in Fig. 3e and theoretical vortex Rossby wave model with RMW of 16.0 km and TC intensities of 23.3 m/s estimated by SHEW model, (h) FFT (fast Fourier transform) results of the theory simulation and SAR detection, and (i) spiral rain band features indicating VRWs (Vortex Rossby waves) shown by GOES (Provided/NOAA) taken at 16:00 UTC on Nov, 2, 2014 between the two SAR images.

Then we apply the FFT to the simulated perturbation wind speed. The scale of the peak FFT power of the simulated perturbation winds is 15.9 km (Fig. 3h). This estimated scale of the VRWs is close to the SAR observation, which is in the range 10-20 km. One caveat is that the above simulation is based on a simple dynamic model which assumes a frictionless boundary. However, the 10-m winds in real TCs experience surface friction. Differences between observed and modeled scales of VRWs are thus expected. Additionally, four extended evidences of the possible VRW patterns in the SAR-derived wind fields in north Atlantic basin in 2023 are presented (Fig. 4). The symmetrical intensities and RMWs (Supplementary Table 1) are determined by the SHEW model. By removing the symmetrical wind field from the SAR-derived winds (Supplementary Fig. 3), the azimuth-radius plots of the residual winds are shown in Fig. 4. The FFT results are from 16.7 km to 25 km (Supplementary Table 1), which are similar to Hurricane Vance (2014) as well as theory results. Additionally, SAR can monitor spiral rainbands (Supplementary Fig. 4), which represent the ‘troughs’ of vortex Rossby waves. While the exact impact of rain on C-band radar remains an active research topic4,18, several mechanisms have been proposed: (1) splash products from raindrop impact96, (2) wind downbursts increasing surface winds97, and (3) volume backscattering from the melting layer where ice particles transition into raindrops98. The dual-polarization (VV/VH) mode of SAR enables simultaneous monitoring of wind wave patterns (VH-polarization) and spiral rainbands (VV-polarization), enhancing our ability to study these features.

Four cases in north Atlantic for 2023 hurricane season and SAR observations over: (a) Hurricane Idalia acquired at 11:26 UTC on 28 August, 2023, onboard RCM-1, (b) Hurricane Franklin acquired at 10:21 UTC on 26 August, 2023, onboard Sentinel-1A, (c) Hurricane Lee acquired at 09:03 UTC on 7 September, 2023, onboard RCM-2, and (d) Hurricane Margot acquired at 08:28 UTC on 11 September, 2023, onboard RCM-1. The FFT (fast Fourier transform) peak results along the black lines are 20.0 km, 25.0 km, 20.0 km and 16.7 km respectively.

Through a process known as ‘axisymmetrization’, VRWs have the ability to transfer energy from TC asymmetries to the vortex mean flow85. As shown in Fig. 3, intensification occurs between the two SAR images, while possible VRW patterns are observed in the SAR-derived winds at the onset of the intensification. Using numerical models, previous studies85,86,87,88,99 have simulated radially propagating waves in TC-like vortices. And ref. 100. demonstrated that VRWs may play an important role in regulating TC intensity change due to the process of asymmetric heating, controlled by environmental shear flow or internal dynamics. We acknowledge that rainband dynamics extend beyond VRW processes and at least two types of rainbands exist—inner rainbands (within ~3×RMW) and outer rainbands—with various studies exploring their roles in TC development. VRWs represent just one of many possible contributing factors101. Thus, we do not suggest that the presence of a strong rainband pattern necessarily indicates impending TC intensification. Instead, we highlight ‘axisymmetrization’ as one potential process among many. In this study, we aim to present observations of possible VRWs in the wind field and their association with TC intensification.

Zhang et al.102 used RADARSAT-1 SAR imagery during the hurricane watch project to confirm the boundary layer rolls detected from aircraft observations, with roll wavelengths of around 900 m. Huang et al.103 analyzed 16 SAR images covering the core area of a TC to investigate marine atmospheric boundary layer rolls, revealing asymmetrically distributed wavelengths of 0.6 to 1.6 km in eyewall and rainbands. Measuring the size of boundary layer rolls provides insights into momentum exchange, sensible heat, and moisture transport within the TC boundary layer, processes that are closely linked to storm development and intensification. Additionally, it aids in estimating potential TC-induced damage during landfall. Therefore, the small-scale structure monitoring would be important for TC intensification understanding and forecasting, and spaceborne SAR can be a viable tool for the TC multi-scale structure monitoring.

Summary

As an imaging radar, spaceborne SAR can simultaneously observe sea surface roughness and capture high spatial resolution images. The roughness of the sea surface can be analyzed to directly determine the surface wind of a TC, in addition to other parameters such as sea surface wave and rainfall. While SAR images are snapshots, they offer a high spatial resolution of the ocean surface, which is unattainable with other -monitoring methods. A unified steering flow (unified background wind vector) and the associated inflow angle can be estimated using the SHEW-2 model, which is based on a simplified conceptual approach that performs well under specific conditions. However, in more complex situations, multiple steering flows may be needed to better explain TC movement. The high spatial resolution of SAR enables the development of multiple steering flow detection methods that better reflects real conditions. Meanwhile, TC intensity prediction persists as a significant challenge, stemming from insufficient understandings and observations of high-resolution TC inner-core vortex dynamics104,105,106,107,108. Using the FFT method, the estimated horizontal scales of these waves range from 10 to 20 km, aligning with results from theoretical models, suggesting that these signatures may reflect ongoing VRW activity.

Figure 5 provides an overview of key SAR satellites, an example of SAR imaging modes of RCM satellites, and potential TC dynamic processes observable with SAR. Through SAR-based identification of TC vortex features (e.g., eye shape, center location, RMW, intensity, and possible double-eye structures) by SHEW models, TC movement factors of inflow angle, steering flows, size information in four- quadrant and possible two TC conditions, as well as intensification factors with smaller-scale including vortex Rossby waves, boundary layer rolls, rain bands (Supplementary Fig. 4), and sub-scale or tornado-scale vortices can be analyzed. Consequently, further exploration of these processes and their representation in high-resolution SAR observations is necessary to achieve a deeper understanding of TC movement and intensification. Spaceborne SAR applications in TC monitoring face three primary constraints: (1) non-real-time operational characteristics necessitating about 3 day advance scheduling for configuration of acquisition positioning and operational mode selection, (2) TCs, characterized by strong winds and heavy rains, remain a critical research focus for declining retrieval uncertainty of winds and rains, and (3) limited temporal resolution from orbital cycle constraints.

Traditionally, wind and rain rate retrievals from SAR rely on physically based algorithms that use NRCS in the VV and VH polarization channels to estimate surface wind speed. While effective, these models are limited to interpreting only the physical signal response. In contrast, SAR imagery also contains rich spatial information, such as texture features derived from the Gray-Level Co-occurrence Matrix (GLCM) and storm-scale morphological structures, which are typically overlooked by physical models. Machine learning methods offer a powerful alternative by integrating both the physical backscatter signals and these higher-order spatial features, enabling a more comprehensive, data-driven approach to retrieval. Recent studies, such as Mu et al.56, have demonstrated that machine learning models can significantly decline the uncertainty and enhance the robustness of wind speed and rain rate estimations from SAR, surpassing the capabilities of conventional physics-based methods.

A critical challenge hindering SAR-based TC monitoring is its inadequate temporal resolution. Its inadequate temporal resolution limits its integration into operational Numerical Weather Prediction (NWP) models, which universally require data inputs suitable for 6 h assimilation cycles to maintain forecast accuracy. As a result, SAR data is not directly assimilated into NWP systems globally. Nevertheless, agencies such as NOAA/NESDIS and JTWC routinely disseminate SAR imagery and derived products, such as surface wind speed, storm center location, and maximum wind radius, in near-real-time. These products are instrumental for forecasters in analyzing storm structure and intensity, thereby enhancing situational awareness despite the current limitations in model assimilation. Upcoming missions such as the Meteorological Operational Satellite Programme Second Generation (MetOp-SG) aim to deploy enhanced C-band scatterometers with SAR-like resolution (5 km), offering 12-h global coverage. These systems, coupled with planned SAR constellations (e.g., NASA-ISRO SAR Mission), could provide overlapping swaths to achieve sub-daily TC monitoring. Future efforts should prioritize the systematic integration of SAR data into operational TC forecasting systems through three sequential phases: (1) identification of critical movement or intensification factor derived from SAR-based TC monitoring, (2) comprehensive utilization of SAR-derived factor to advance fundamental understanding of TC dynamics, and (3) operational implementation of these improved dynamic insights through numerical assimilation frameworks. The latter two phases will be conducted in close collaboration with TC dynamic specialists to ensure rigorous physical interpretation and effective translation of SAR observations into predictive model enhancements.

Three idealized models for SAR TC monitoring

SAR TC monitoring has been discussed, and idealized models can provide additional information beyond SAR-derived sea surface winds. Although SAR images only cover a portion of the wind speed field over the sea surface, morphology models can provide valuable information. Based on the SAR-derived ocean wind field, various mean flow has been estimated by the idealized SHEW (Symmetric Hurricane Estimates for Winds) model2,60, ASHEW (Asymmetric Hurricane Estimates for Winds) model5, and SHEW-2 (Surface Hurricane Estimates for Wind speed and Wind direction) model61. The SHEW model is for elliptical mean flow, the ASHEW model is for Fourier wavenumber-1 asymmetry, and the SHEW-2 model is for inflow angle asymmetry. The idealized models have been developed over the past 10 years to detect the TC center, intensity, radius of maximum wind (RMW) and various asymmetrical TC structures of asymmetrical amplitude, inflow angle, elliptical eyewall, and secondary eyewall from SAR-derived winds directly, automatically and independently. The general approach of the three idealized models is as follows: (1) give an initial TC center, (2) detect the maximum wind and location in each azimuth of the 360 degrees with a window of 10 degrees, (3) find the reference ellipse closest to the locations of maximum wind in each direction, (4) compute the TC center as the center of reference ellipse, (5) fit the parametric TC model (Rankine vortex or Holland vortex model) to the SAR-derived winds using the detected center, and (6) extract the TC parameters of various TC vortexes and structures.

The surface background wind related to TC movements discussed in “Asymmetric vortex and TC movement” can be detected by the SHEW-2 model. This model is a feasible method for identifying inflow angle and approximating wind direction using SAR-derived sea surface wind fields. When the wind speeds in the estimated SHEW-2 vectors are fitted to SAR-retrieved wind speed field, the wind directions are estimated associated with the best-fitted wind speed field in the estimated SHEW-2 vector field. For the small-scale features discussed in “Small-scale patterns and TC intensification”, the idealized models can be used to reconstruct the complete TC surface wind field, which provides the baseline for TC dynamic studies. Additionally, TC center identified from SAR data independently is crucial for determining the structure and size from SAR data (Supplementary Fig. 5). There are two methods to locate the hurricane center: directly from the derived SAR wind field or from the SAR image. The SHEW models are belonging to the first method. Regarding the second method, we acknowledge Du’s work6. Furthermore, Jin and colleagues have explored various approaches for this task109,110,111.

Data availability

The RADARSAT-2 data were provided by the Canadian Space Agency under the Hurricane Watch project, which can be acquired from Earth Observation Data Management System (https://www.eodms-sgdot.nrcan-rncan.gc.ca). The Sentinel-1 data were provided by the European Space Agency (https://eoda.cls.fr/client/oceano/#Sentinel). The SFMR and dropsonde data were provided by NOAA (https://www.aoml.noaa.gov/hrd/data_sub/hurr.html). The best track data are from Schreck, Carl & National Center for Atmospheric Research Staff (Eds). Last modified 2022-09-09 “The Climate Data Guide: IBTrACS: Tropical cyclone best track data.” Retrieved from https://climatedataguide.ucar.edu/climate-data/ibtracs-tropical-cyclone-best-track-data. The spiral rain band features indicating VRWs in hurricane Vance (2014) shown by GOES is Provided by NOAA (https://www.ctvnews.ca/world/hurricane-vance-forms-in-pacific-no-immediate-threat-to-land-1.2083274).

Code availability

The codes that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on request. And we can provide colorblind-friendly figures upon request.

References

Li, X. et al. Tropical cyclone morphology from spaceborne synthetic aperture radar. Bull. Am. Meteor. Soc. 94, 215–230 (2013).

Zhang, G., Zhang, B., Perrie, W., Xu, Q. & He, Y. A hurricane tangential wind profile estimation method for C-band cross-polarization SAR. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 52, 7186–7194 (2014).

Li, X. Hurricane Monitoring with Spaceborne Synthetic Aperture Radar 1st edn, Vol. 398 (Springer Nature, 2017)

Mouche, A. et al. Co-polarized and cross-polarized SAR measurements for high-resolution description of major hurricane wind structures: application to Irma category 5 hurricane. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 124, 3905–3922 (2019).

Zhang, G., Perrie, W., Zhang, B., Yang, J. & He, Y. Monitoring of tropical cyclone structures in ten years of RADARSAT-2 SAR images. Remote Sens. Environ. 236, 111449 (2020).

Du, Y. & Vachon, P. W. Characterization of hurricane eyes in RADARSAT-1 images with wavelet analysis. Can. J. Remote. Sens. 29, 491–498 (2003).

Reppucci, A., Lehner, S., Schulz-Stellenfleth, J. & Brusch, S. Tropical cyclone intensity estimated from wide-swath SAR images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 48, 1639–1649 (2010).

Vachon, P. W. & Wolfe, J. C-band cross-polarization wind speed retrieval. IEEE Geosci. Remote. Sens. Lett. 8, 456–459 (2010).

Zhang, B. & Perrie, W. Cross-polarized synthetic aperture radar: a new potential measurement technique for hurricanes. Bull. Am. Meteor. Soc. 93, 531–541 (2012).

Zadelhoff, G. J. et al. Retrieving hurricane wind speeds using cross-polarization C-band measurements. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 7, 437–449 (2014).

Hwang, P. A. et al. Cross-polarization geophysical model function for C-band radar backscattering from the ocean surface and wind speed retrieval. J. Geophys. Res. 120, 893–909 (2015).

Mouche, A., Chapron, B., Zhang, B. & Husson, R. Combined co- and cross- polarized SAR measurements under extreme wind conditions. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 55, 6746e6755 (2017).

Zhang, G. et al. A hurricane wind speed retrieval model for C-band RADARSAT-2 cross-polarization ScanSAR images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 55, 4766–4774 (2017).

Zhang, G. et al. C-band right-circular polarization ocean wind retrieval. IEEE Geosci. Remote. Sens. Lett. 16, 1398–1401 (2019).

Mu, S., Li, X. & Wang, H. The fusion of physical, textural, and morphological information in SAR imagery for hurricane wind speed retrieval based on deep learning. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 60, 1–13 (2022).

Combot, C. et al. Extensive high-resolution synthetic aperture radar (SAR) data analysis of tropical cyclones: comparisons with SFMR flights and best track. Mon. Wea. Rev. 148, 4545–4563 (2020).

Jackson, C. R., Ruff, T. W., Knaff, J. A., Mouche, A., Sampson, C. R. Chasing Cyclones From Space. https://eos.org/features/chasing-cyclones-from-space (2021).

Knaff, J. A. & Coauthors Estimating tropical cyclone surface winds: current status, emerging technologies, historical evolution, and a look to the future. Trop. Cyclone Res. Rev. 10, 125–150 (2021).

Hauser, D. et al. Satellite remote sensing of surface winds, waves, and currents: where are we now? Surv Geophys. 44, 1357–1446 (2023).

Howell, B., Egan, S. & Fine, C. Application of microwave space-based environmental monitoring (SBEM) data for operational tropical cyclone intensity estimation at the Joint typhoon warning center. Bull. Am. Meteor. Soc. 103, E2315–E2322 (2022).

Reppucci, A., Lehner, S., and Schulz-Stellenfleth, J. Tropical Cyclone Parameters Derived from Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) Images. In 2006 IEEE International Symposium on Geoscience and Remote Sensing, 2220−2223 (2006).

Corcione, V., Nunziata, F. & Migliaccio, M. Megi typhoon monitoring by x-band synthetic aperture radar measurements. In IEEE Journal of Oceanic Engineering, 184−194 (IEEE, 2018).

Vinour, L., Jullien, S., Mouche, A., Combot, C. & Mangeas, M. Observations of tropical cyclone inner-core fine-scale structure, and its link to intensity variations. J. Atmos. Sci. 78, 3651–3671 (2021).

Yurchak, B. S. Estimating the intensity of tropical cyclones from spiral signatures acquired by spaceborne SAR. Remote Sens. 16, 1750 (2024).

Avenas, A. et al. Revealing short-term dynamics of tropical cyclone wind speeds from satellite synthetic aperture radar. Sci. Rep. 14, 12808 (2024).

Foster, R. C. Why rolls are prevalent in the Hurricane boundary layer. J. Atmos. Sci. 62, 2647–2661 (2005).

Du, R., Zhang, G. & Huang, B. Observed surface wind field structure of severe tropical cyclones and associated precipitation. Remote Sens. 15, 2808 (2023).

Dvorak, V. F. Tropical cyclone intensity analysis and forecasting from satellite imagery. Mon. Wea. Rev. 103, 420–430 (1975).

Dvorak, V. F. Tropical Cyclone Intensity Analysis Using Satellite Data. https://repository.library.noaa.gov/view/noaa/19322 (1984).

Velden, C. S., Olander, T. L. & Zehr, R. M. Development of an objective scheme to estimate tropical cyclone intensity from digital geostationary satellite infrared imagery. Weather Forecast. 13, 172–186 (1998).

Velden, C. & Coauthors The dvorak tropical cyclone intensity estimation technique: a satellite-based method that has endured for over 30 years. Bull. Am. Meteor. Soc. 87, 1195–1210 (2006).

Olander, T. L. & Velden, C. S. The advanced Dvorak technique: Continued development of an objective scheme to estimate tropical cyclone intensity using geostationary infrared satellite imagery. Weather Forecast 22, 287–298 (2007).

Zhang, J. et al. Relationship between near-surface winds due to tropical cyclones and infrared brightness temperature obtained from geostationary satellite. Atmosphere 12, 493 (2021).

Zhang, J. A. & Uhlhorn, E. W. Hurricane sea surface inflow angle and an observation-based parametric model. Mon. Weather Rev. 140, 3587–3605 (2012).

Uhlhorn, E. W., Klotz, B. W., Vukicevic, T., Reasor, P. D. & Rogers, R. F. Observed hurricane wind speed asymmetries and relationships to motion and environmental shear. Mon. Weather Rev. 142, 1290–1311 (2014).

Willoughby, H. E. & Rahn, M. E. Parametric representation of the primary hurricane vortex. Part I: observations and evaluation of the Holland (1980) model. Mon. Weather Rev. 132, 3033–3048 (2004).

Holland, G. J., Belanger, J. I. & Fritz, A. A revised model for radial profiles of Hurricane winds. Mon. Wea. Rev. 138, 4393–4401 (2010).

Rogers, R., Reasor, P. & Lorsolo, S. Airborne doppler observations of the inner-core structural differences between intensifying and steady-state tropical cyclones. Mon. Weather. Rev. 141, 2970–2991 (2013).

Rogers, R. F. Recent advances in our understanding of tropical cyclone intensity change processes from airborne observations. Atmosphere 12, 650 (2021).

Barron, N. R., Didlake, A. C. Jr & Reasor, P. D. Statistical analysis of convective updrafts in tropical cyclone rainbands observed by airborne Doppler radar. J. Geophys. Res. 127, e2021JD035718 (2022).

Uhlhorn, E. W. & Black, P. G. Verification of remotely sensed sea surface winds in hurricanes. J. Atmos. Ocean. Tech. 20, 99–116 (2003).

Uhlhorn, E. W. et al. Hurricane surface wind measurements from an operational stepped frequency microwave radiometer. Monthly Weather Rev. 135, 3070–3085 (2007).

Klotz, B. W. & Uhlhorn, E. W. Improved stepped frequency microwave radiometer tropical cyclone surface winds in heavy precipitation. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 31, 2392–2408 (2014).

Polverari, F. et al. On dropsonde surface-adjusted winds and their use for the stepped frequency microwave radiometer wind speed calibration. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 60, 1–8 (2022).

Klotz, B. W. & Jiang, H. Global composites of surface wind speeds in tropical cyclones based on a 12 year scatterometer database. Geophys. Res. Lett. 43, 10–480 (2016).

Liu, K. S. & Chan, J. C. Size of tropical cyclones as inferred from ERS-1 and ERS-2 data. Mon. Wea. Rev. 127, 2992–3001 (1999).

Brennan, M. J., Hennon, C. C. & Knabb, R. D. The operational use of QuikSCAT ocean surface vector winds at the National Hurricane Center. Weather Forecast 24, 621–645 (2009).

Chavas, D. R. & Emanuel, K. A. A QuikSCAT climatology of tropical cyclone size. Geophys. Res. Lett. 37, L18816 (2010).

Reul, N. et al. A new generation of tropical cyclone size measurements from space. Bull. Am. Meteor. Soc. 98, 2367–2385 (2017).

Hwang, P. A., Zhang, B., Toporkov, J. V., Perrie, W., Comparison of composite Bragg theory and quad-polarization radar backscatter from RADARSAT-2: With applications to wave breaking and high wind retrieval. J. Geophys. Res. https://doi.org/10.1029/2009JC005995 (2010).

Kudryavtsev, V., Kozlov, I., Chapron, B. & Johannessen, J. A. Quad-polarization SAR features of ocean currents. J. Geophys. Res. 119, 6046–6065 (2014).

Hwang, P. A. Fetch-and duration-limited nature of surface wave growth inside tropical cyclones: with applications to air–sea exchange and remote sensing. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 46, 41–56 (2016).

Zhang, G., Li, X., Perrie, W., Zhang, B. & Wang, L. Rain effects on the hurricane observations over the ocean by C-band synthetic aperture radar. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 121, 14–26 (2016).

Zhang, G., Perrie, W., Zhang, B., Khurshid, S. & Warner, K. Semi-empirical ocean surface model for compact-polarimetry mode SAR of RADARSAT constellation mission. Remote Sens. Environ. 217, 52–60 (2018).

Souyris, J. C., Imbo, P., Fjortoft, R., Mingot, S. & Lee, J. S. Compact polarimetry based on symmetry properties of geophysical media: the π/4 mode. IEEE T. Geosci. Remote Sens. 43, 634–646 (2005).

Mu, S. et al. High-resolution tropical cyclone rainfall detection from C-band SAR imagery with deep learning, In IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing, 1-15 (IEEE, 2024).

Colin, A. & Husson, R. Rainfall regression from C-band synthetic aperture radar using multitask generative adversarial networks. Artif. Intell. Earth Syst. 4, e240007 (2025).

Katsaros, K., P. W., Vachon, P., Black, P., Dodge & Uhlhorn, E. Wind Fields from SAR: Could They Improve Our Understanding of Storm Dynamics? https://doi.org/10.4095/219617 (2000).

Zhang, G. & Perrie, W. Effects of asymmetric secondary eyewall on tropical cyclone evolution in Hurricane Ike (2008). Geophys. Res. Lett. 45, 1676–1683 (2018).

Zhang, G., Perrie, W., Li, X. & Zhang, J. A. A hurricane morphology and sea surface wind vector estimation model based on C-band cross-polarization SAR imagery. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 55, 1743–1751 (2016).

Zhang, G., Li, X., Perrie, W. & Zhang, J. A. Tropical cyclone winds and inflow angle asymmetry from SAR imagery. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48, e2021GL095699 (2021).

Foster, R. Wind fields from SAR: could they improve our understanding of storm dynamics. In Hurricane Monitoring With Spaceborne Synthetic Aperture Radar, (ed. X. Li, X.) 398 (Springer Natural Hazards, 2017).

Vinour, L., Jullien, S. & Mouche, A. Diagnosing tropical cyclone intensity variations from the surface wind field evolution. J. Atmos. Sci. 80, 2459–2479 (2023).

Moore Torres, J. C., Jackson, C. R., Ruff, T. W., Helfrich, S. R. & Romeiser, R. Observing tropical cyclone morphology using RADARSAT-2 and sentinel-1 synthetic aperture radar images. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 40, 789–801 (2023).

Avenas, A. et al. Reexamining the estimation of tropical cyclone radius of maximum wind from outer size with an extensive synthetic aperture radar dataset. Mon. Wea. Rev. 151, 3169–3189 (2023).

Avenas, A., Mouche, A., Knaff, J., Carton, X. & Chapron, B. On the tropical cyclone integrated kinetic energy balance. Geophys. Res. Lett. 51, e2024GL108327 (2024).

Shimada, U., Hayashi, M. & Mouche, A. A comparison between sar wind speeds and western North Pacific tropical cyclone best track estimates. J. Meteorol. Soc. Jpn. Ser. II 102, 575–593 (2024).

Tsukada, T. & Horinouchi, T. Strong relationship between eye radius and radius of maximum wind of tropical cyclones. Monthly Weather Rev. 151, 569–588 (2023).

Zheng, G. et al. Rainbandoccurrence probability in Northern Hemisphere tropical cyclones by synthetic aperture radar imagery. Geophys. Res. Lett. 51, e2023GL107555 (2024).

Jiang, H. et al. Tropical cyclone rainbands in SAR images. In 2022 3rd International Conference on Geology, Mapping and Remote Sensing (ICGMRS), 15–19 (IEEE, 2022).

Chan, J. C. L. & Gray, W. M. Tropical cyclone movement and surrounding flow relationships. Mon. Wea. Rev. 110, 1354–1374 (1982).

Chan, J. C. The physics of tropical cyclone motion. Annu Rev. Fluid Mech. 37, 99–128 (2005).

Lin, N. & Chavas, D. On hurricane parametric wind and applications in storm surge modeling. J. Geophys. Res. 117, D09120 (2012).

Kossin, J. P. A global slowdown of tropical-cyclone translation speed. Nature 558, 104–107 (2018).

Chu, P.-S., Kim, J.-H. & Chen, Y. R. Have steering flows in the western North Pacific and the South China Sea changed over the last 50 years?. Geophys. Res. Lett. 39, L10704 (2012).

Hassanzadeh, P. et al. Effects of climate change on the movement of future landfalling Texas tropical cyclones. Nat. Commun. 11, 3319 (2020).

Wang, S. & Toumi, R. Recent migration of tropical cyclones toward coasts. Science 371, 514–517 (2021).

Phadke, A. C., Martino, C. D., Cheung, K. F. & Houston, S. H. Modeling of tropical cyclone winds and waves for emergency management. Ocean Eng. 30, 553–578 (2003).

Emanuel, K., Ravela, S., Vivant, E. & Risi, C. A statistical deterministic approach to hurricane risk assessment. Bull. Am. Meteor. Soc. 87, 299–314 (2006).

Lin, N., Emanuel, K., Oppenheimer, M. & Vanmarcke, E. Physically based assessment of hurricane surge threat under climate change. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2, 462–467 (2012).

Mei, W., Pasquero, C. & Primeau, F. The effect of translation speed upon the intensity of tropical cyclones over the tropical ocean. Geophys. Res. Lett. 39, L07801 (2012).

Mei, W. & Xie, S. P. Intensification of landfalling typhoons over the northwest Pacific since the late 1970s. Nat. Geosci. 9, 753–757 (2016).

Hlywiak, J. & Nolan, D. S. The evolution of asymmetries in the tropical cyclone boundary layer wind field during landfall. Mon. Wea. Rev. 150, 529–549 (2022).

Liu, H.-Y. et al. Predictability of the most long-lived tropical cyclone Freddy (2023) during its westward journey through the southern tropical Indian Ocean. Geophys. Res. Lett. 50, e2023GL105729 (2023).

Montgomery, M. T. & Kallenbach, R. J. A theory for vortex rossby-waves and its application to spiral bands and intensity changes in hurricanes. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 123, 435–465 (1997).

Qiu, X., Tan, Z. & Xiao, Q. The roles of vortex rossby waves in hurricane secondary eyewall formation. Monthly Weather Rev. 138, 2092–2109 (2010).

Peng, M. S., Peng, J., Li, T. & Hendricks, E. Effect of baroclinicity on vortex axisymmetrization. Part I: barotropic basic vortex. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 31, 1256–1266 (2014).

Gao, C. & Zhu, P. Vortex Rossby wave propagation in baroclinic tropical cyclone-like vortices. Geophys. Res. Lett. 43, 12,578−12,589 (2016).

Chelton, D. B. & Schlax, M. G. Global observations of oceanic Rossby waves. Science 272, 234–238 (1996).

Macdonald, N. J. The evidence for the existence of Rossby-like waves in the hurricane vortex. Tellus 20, 138–150 (1968).

McWilliams, J. C., Graves, L. P. & Montgomery, M. T. A formal theory for vortex Rossby waves and vortex evolution. Geophys. Astrophys. Fluid Dyn. 97, 275–309 (2003).

Gall, R., Tuttle, J. & Hildebrand, P. Small-scale spiral bands observed in hurricanes Andrew, Hugo, and Erin. Mon. Weather Rev. 126, 749–766 (1998).

Wurman, J. & Winslow, J. Intense sub-kilometer-scale boundary layer rolls observed in Hurricane Fran. Science 280, 555–557 (1998).

Morrison, I., Businger, S., Marks, F., Dodge, P. & Businger, J. A. An observational case for the prevalence of roll vortices in the hurricane boundary layer. J. Atmos. Sci. 62, 2662–2673 (2005).

Lorsolo, S., Schroeder, J. L., Dodge, P. & Marks, F. An observational study of hurricane boundary layer small-scale coherent structures. Mon. Wea. Rev. 136, 2871–2893 (2008).

Liu, X., Zheng, Q., Liu, R., Sletten, M. A. & Duncan, J. H. A model of radar backscatter of rain-generated stalks on the ocean surface. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 55, 767–776 (2016).

King, G. P., Marcos P., Lin W. & Stoffelen A. Correlating extremes in wind divergence with extremes in rain over the Tropical Atlantic. Remote Sens. 14, 1147 (2022)

Alpers, W., Yuan, Z., Mouche, A. & Chan, P. W. A note on radar signatures of hydrometeors in the melting layer as inferred from Sentinel-1 SAR data acquired over the ocean. Remote. Sens. Environ. 253, 112177 (2021).

Möller, J. D. & Montgomery, M. T. Tropical cyclone evolution via potential vorticity anomalies in a three-dimensional balance model. J. Atmos. Sci. 57, 3366–3387 (2000).

Willoughby, H. E., Rappaport, E. N. & Marks, F. D. Hurricane forecasting: the state of the art. Nat. Hazards Rev. 8, 45–49 (2007).

Yu, C. K., Lin, C. Y. & Pun, C. H. Origin of outer tropical cyclone rainbands. Nat. Commun. 14, 7061 (2023).

Zhang, J. A. et al. Effects of roll vortices on turbulent fluxes in the hurricane boundary layer. Bound-Layer. Meteor 128, 173–189 (2008).

Huang, L. et al. Tropical cyclone boundary layer rolls in synthetic aperture radar imagery. J. Geophys. Res. 123, 2981–2996 (2018).

Zhang F. et al. Performance of convection-permitting hurricane initialization and prediction during 2008-2010 with ensemble data assimilation of inner-core airborne Doppler radar observations. Geophys. Res. Lett. https://doi.org/10.1029/2011GL048469 (2011).

Aksoy, A. et al. The HWRF Hurricane ensemble data assimilation system (HEDAS) for high-resolution data: the impact of airborne Doppler radar observations in an OSSE [J]. Monthly weather Rev. 140, 1843–1862 (2012).

Gopalakrishnan, S. G. et al. A study of the impacts of vertical diffusion on the structure and intensity of the tropical cyclones using the high resolution HWRF system [J]. J. Atmos. Sci. 70, 524–541 (2013).

Zhang, S. & Pu, Z. Numerical simulation of rapid weakening of Hurricane Joaquin with assimilation of high-Definition sounding system dropsondes during the tropical cyclone intensity experiment: comparison of three-and four-dimensional ensemble–variational data assimilation [J]. Weather Forecast. 34, 521–538 (2019).

Li, X. et al. Combined assimilation of doppler wind lidar and tail doppler radar data over a hurricane inner core for improved hurricane prediction with the NCEP regional HWRT system [J]. Remote Sens. 14, 2367 (2022).

Jin, S., Li, X., Yang, X., Zhang, J. & Shen, D. Identification of tropical cyclone centers in SAR imagery based on template matching and particle swarm optimization algorithms. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 57, 598–608 (2019).

Jin, S. et al. Center location of tropical cyclones without eyes in SAR images based on salient region detection and pattern matching. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 55, 280–291 (2017).

Jin, S., Wang, S. & Li, X. Typhoon eye extraction with an automatic SAR image segmentation method. Int. J. Remote Sens. 35, 3978–3993 (2014).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Canadian Space Agency for providing RADARSAT-2 data, the NOAA STAR SAROPS Tropical Cyclone System for providing SAR-derived wind fields last modified 2025-03-18, the NOAA International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS) for providing tropical cyclone best track data, and the NOAA Hurricane Research Division, NOAA Aircraft Operations Center, and the U.S. Air Force Reserve for collecting and maintaining the SFMR data. This work was supported by the Major Science and Technology Plan Project of Yazhou Bay Innovation ResearchInstitute of Hainan Tropical Ocean College (2022CXYZD003) and National Natural Science Foundation of China (41706193).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.Z. conceived and designed the experiments, performed the experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the paper. X.L. conceived and designed the experiments, contributed materials, and wrote the paper. P.W.C. analyzed the data and wrote the paper. H.S. wrote the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, G., Li, X., Chan, P. et al. Potential tropical cyclone movement and intensification factors imaged by spaceborne SAR. npj Clim Atmos Sci 8, 264 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-01162-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-01162-1