Abstract

The Great Lakes region has a unique climatology due to its large water bodies. Dynamic seasonal wind speeds are an important component in this climate that requires further study. Using 10-m wind data from ERA5-Land, this study employs remote teleconnection indices and local climate features to predict low-level wind speeds using Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) machine learning. The model for monthly winds achieves high accuracy, with an R² of 0.96 and a Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) of 0.12 m/s−1. The Shapley Additive Values (SHAP) analysis reveals that local climate variables, including the proximity to the nearest Great Lake, surface roughness, and surface temperature, are the most influential predictors and are most important in the model. Teleconnections such as the El Niño-Southern Oscillation and the Arctic Oscillation play minor roles. This study provides a new multiscale perspective on wind speed characteristics, drivers, and insights into the region’s wind energy potential.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

While fossil fuels have historically supplied energy, their combustion leads to elevated carbon dioxide (CO2) concentrations and warmer climates, now widely known as an unsustainable practice1. Renewable energy is gaining appeal due to its decreased material costs, technological advancements, favorable government policies, and adherence to the overall Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)2. Wind energy is clean, reproducible, and free from carbon emissions, and the global wind energy resource greatly exceeds the current global energy demand3,4.

Surface wind speeds significantly influence current and future energy yields from wind turbines5. Surface wind speeds are challenging to interpret and predict due to their sensitivity to measurement methods and station surroundings, as they exhibit strong spatial and temporal heterogeneity. For wind energy to continue gaining favor, the scientific community to understand the drivers of wind speed better and improve its predictability, providing a reference for the availability and viability of wind energy.

Teleconnections are relationships between local weather and atmospheric or oceanic variability in remote parts of the world. For example, El Niño/Southern Oscillation (ENSO) is a very important teleconnection that measures sea surface temperature anomalies in the tropical Pacific Ocean and significantly influences weather and climate patterns on both sides of the basin. Previous climatological works have found associations between ENSO and North American precipitation and temperature6. Bjerknes et al. 7 discovered a robust link between Northern Hemisphere winter wind patterns and the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO), laying the groundwork for many contemporary studies. El Niño events have stronger influences on spring and winter seasonal mean winds, while La Niña events have a stronger impact on summer season mean winds, with a smaller effect on spring winds8. In the Great Lakes region, major El Niño events are characterized by lower mean wind speeds and more frequent calm winds8.

Many climatological studies have investigated teleconnections, primarily focusing on their impacts on temperature and precipitation9,10. Fewer are focused on the relationships between climate and wind speed, particularly at regional or local scales. For example, a statewide study in Minnesota11 finds wind speeds follow a seasonal cycle, with wind speed peaks in both February and April and a second maximum occurrence in October or November. The Great Lakes region (40°N –50°N; 94°W –75°W) has a large seasonal variability with peaks in November through January and lows in both July and August8. At a larger spatial scale, wind speeds are highest in the winter and spring and lowest in the summer across the continental United States12.

While the patterns and trends of wind speeds have been investigated at different spatial scales, limited studies have comprehensively analyzed the multiscale relationships between teleconnection indices, local climate and environmental factors, and regional wind speeds, despite their complex interactions. The Great Lakes region is an ideal location for wind power generation, owing to its abundant wind resources and proximity to major economic and population centers with high electricity demand. It is generally agreed upon that large waterbodies impact land surface wind speeds and their variability13. Understanding the importance and factors controlling surface wind variability is crucial information for generating wind energy14,15,16. Challenges exist in disentangling the relationships between teleconnections and wind variability at the regional scale, particularly when these relationships are not linear or lagged17. In addition, the lake breeze is a local-scale wind system dependent on the gradient difference between the lake and land temperatures18 and could have important impacts on wind variability in the Great Lakes.

Climate change may also play a role. Winkler et al. find that winds in the Midwest increased up to 15% for 2041–2062 vs. 1979–2000 based on ensemble regional climate model simulations, though the reasons for this increase remain unclear19. Given the above discussions, more research is necessary to elucidate each factor’s contribution and their interactions with the surface winds, which may help explain the historical variability and project possible future winds over the Great Lakes19.

As a state-of-the-art technology, machine learning is uniquely suited to analyze and compare climatological phenomena for a comprehensive understanding of multiscale processes. It will help explain the wind variabilities in the Great Lakes region, including both remote and local factors at different spatial and temporal scales. Therefore, the study aims to 1) analyze the spatial and temporal patterns and changes of surface winds in Michigan; 2) develop a machine learning model that can accurately predict wind variabilities in Michigan based on multiscale climate and environmental factors; and 3) elucidate each factor’s contribution and their interactions with the surface wind by using the explainable machine learning approach. Additionally, it can provide essential knowledge about the factors controlling Michigan’s wind speeds, which will serve as a model for the Great Lakes region. This knowledge will be essential for designing and planning wind farms in this region, as well as for developing strategies to mitigate wind-related hazards.

Results

Wind speed characteristics

The monthly mean wind speeds across Michigan range from 2.01 m/s−1 to 4.30 m/s−1 (Fig. 1a). Generally, more intense winds are in coastal areas, while lower speeds are typically located inland. The highest wind speeds are found near the tips of the peninsulas, such as Huron County on the coast of Lake Huron and Saginaw Bay on the state’s east side. The northwest tip of the Lower Peninsula and the southern tip of the Upper Peninsula are also categorized into the highest class (3.15–4.30 m/s−1). Seasonally, the lowest wind speeds occur in summer, while the highest are observed in fall and winter (Fig. 1b), which agrees with past findings across the United States12. The inland counties have a seasonal variance of 0.48 m/s−1, while the coastal counties have a variance of 0.71 m/s−1. This difference suggests that coastal counties experience more wind fluctuations, possibly due to being more frequently influenced by Great Lakes weather than inland counties.

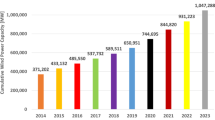

a Spatial distribution of mean wind speeds (m/s−1) from 1950 to 2020. Wind speeds are gathered on an hourly basis and are averaged monthly for each county. b A bar plot displaying three calculations of wind speeds. In red is the overall mean wind speed in the State of Michigan. The mean wind speeds in blue correspond to locations where the county’s centroid is within 0.4 km of the nearest Great Lake. The mean wind speeds in green correspond to areas where the county’s centroid is more than 0.4 km from the nearest Great Lake. c The time series of the mean wind speeds per year across Michigan. The green line represents a 4-year moving average fit to smooth the time series.

Figure 1c shows the annual mean wind speeds had their highest values in 1950 and remained high in various years throughout the 1970s and 1980s, at ~2.7 m/s. On the other hand, 1972 had the lowest wind speed at 2.52 m/s−1, which is 0.35 m/s−1 (12%) lower than the maximum value in 1950. Larger fluctuations in annual wind speed are exhibited before the year 2000, whereas more recent years show less interannual variability. The 4-year moving average smooths the data variation and makes longer-term trends more apparent. A Mann-Kendall test finds no statistically significant trend through the time series. However, there is a wider range of variation in the graph earlier in the time series compared to more modern times. The standard deviation for the first 25 years of the time series (1950–1974) is 0.089 m/s−1, whereas the standard deviation for the final 25 years (1996–2020) is 0.057. Levene’s test for equal variances finds that the difference in the deviations is statistically significant at the 0.03 level. Likewise, the variance for the beginning of the time series is 0.008, while the end value is 0.003; both are statistically significant at 0.01 based on the F-test.

Spectral analysis reveals that the most significant peak frequencies for wind speeds are at six and 12-month intervals (Fig. S2). Other peaks are at approximately the 4-year and 2-year mark, although those periods are not statistically significant. The Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation (AMO) exhibits the highest number of substantial matching frequencies with wind speeds among all teleconnections and local climate variables, followed by the Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO). The domination of inter- and intra-annual to decadal and multidecadal cycles may explain the lack of a statistically significant temporal trend from the Mann-Kendall test across the time series of the wind speed. Moreover, the length of our dataset and the complexity of multi-scale physical forcings of the wind speed may limit our ability to accurately resolve low-frequency variabilities through spectral analysis, which may elucidate the need for machine learning approaches as an alternative to analyzing the same data.

Following the spatial and temporal analysis, we developed XGBoost models to assess monthly wind speeds for every county in Michigan based on local climate variables, including surface roughness, temperature, and pressure, as well as remote teleconnection indices from around the world. The XGBoost algorithm is a non-parametric Machine Learning model, making it highly flexible for the types and scales of feature variables and powerful in predicting wind speeds20,21. The full list of 25 feature variables used in the model is presented in SI Table 1.

XGBoost performance

The XGBoost-predicted monthly wind speeds agree well with the observations when using an 80/20% training-to-testing split (Fig. 2a, b). The R2 value is 0.96, with a root mean squared error (RMSE) of 0.12 m/s−1, for the all-season model, indicating excellent out-of-sample prediction performance for the XGBoost model. The area with the highest density (~400 data points per hexagon bin) suggests a positively skewed distribution towards the lower ranges of wind speeds between 2 and 3 m/s−1. Seasonal density models also demonstrate high R² values, ranging from 0.94 to 0.97 (2b), based on the 20% testing data. All RMSEs exhibit low values with slight seasonal variations, ranging from 0.11 m/s−1 to 0.12 m/s−1. These results exhibit seasonal sensitivity, yet the overall stability of the XGBoost model’s excellent performance remains consistent across all seasons. Summer wind speeds have the lowest RMSE value, possibly attributed to the relatively lower summer wind speeds compared to other seasons, as reflected by the greatest density of dots below ~3 m/s-1 in Fig. 2b–Summer. Winter and fall host the highest wind speeds, while displaying the highest R² value, indicating our model’s ability to capture cold-season wind variability particularly well.

The coloration represents the density of the points based on equal-size hexagons, and the density of the scatter points represents how the data is clustered in the observation/prediction space. a Density Scatter Plot of Predicted vs. Observed Wind Speeds for all seasons. b Density scatter plots of observed vs predicted values by season.

SHAP feature analysis

We applied SHAP analysis to better understand the variable importance and interactions with wind speed in the XGBoost model. The SHAP value quantifies how changes in individual feature variables influence the model’s prediction22,23. Specifically, a positive SHAP value indicates that the feature contributes positively to the mean predicted outcome (in this case, higher wind speed), while a negative value suggests the opposite. Additionally, the magnitude of the SHAP values provides insight into the sensitivity of wind speed to changes in individual features, indicating the importance of each feature. We calculated the feature importance of the XGBoost model based on all data using the ‘shap’ package in Python (Fig. 3) and listed the top 15 most important features24. Topping the list are Dist (distance from nearest Great Lake), fsr (forecasted surface roughness), and MST (Michigan Skin Temperature), which are all local and regional environmental variables. The most important teleconnection variable in the model is the ENSO Climate Adjusted Index (ENSO_CAI), ranked the 6th most important. The Western Pacific (WP) ranked 9th, while another ENSO-related index, Niño 4, ranked 10th. We also included the complete feature importance plot as Fig. S5, which demonstrates that all feature variables have some control over the wind speed with variations in sensitivity.

The SHAP value represents how the model’s prediction changes in response to changes in individual features relative to the average prediction. Each number to the left of the variable name corresponds to the feature’s importance, calculated as the absolute mean of all SHAP values for that feature. This value indicates the sensitivity of monthly wind speed to variations in each feature.

We also analyzed interactions between individual features and the wind SHAP value24. Figure 4 displays the SHAP interaction plots for the most important features in the model, ranging from local and regional to teleconnection factors. Figs. S5 and S6 include SHAP plots for additional features. The nearest distance to the coast (Dist) ranks highest in terms of SHAP importance (Fig. 3) and exhibits a nonlinear, negative relationship with the wind speed SHAP values (Fig. 4a). The SHAP values decrease exponentially when the Dist increases from 0 to ~ 0.3 km. With Dist ~0.3 km or greater, the SHAP values remain relatively constant at negative values of small magnitude near zero. Therefore, the XGBoost model accurately captured the decreasing gradient of wind speed from coastal counties to inland counties, possibly due to changes in lake breeze intensity and surface roughness from coastal to inland areas. Surface roughness (fsr) is the second most important feature in the model, and the SHAP value exhibits a linearly decreasing pattern with increases in fsr (Fig. 4b). The fsr has a positive contribution to the mean wind speed (SHAP > 0) when it is under 1.0 m and a negative contribution (SHAP < 0) when it is >1.0 m. Thus, the smoother the surface, the faster the winds. The coastal regions near the Great Lakes normally have less surface roughness than the inland areas, creating a more favorable environment for stronger winds.

The SHAP value plots for a Distance to the coast (Dist), b forecasted surface roughness (fsr), c Michigan Skin Temperature (MST), and d difference of surface pressure between lake and land (DiffSP). The gray bars along the x-axis display the histogram, which shows the distribution of each feature. The color of the dots indicates variations of another feature that covariates most with each specific feature.

The relationship between MST and SHAP also shows a nonlinear pattern: cooler temperatures are associated with wind speeds that are higher than average (Fig. 4c). At ~285 K, the estimated wind speeds dramatically decrease and continue to decline as MST falls. Interestingly, the fsr is the dampening factor for the wind speed sensitivity to MST: high fsr values (red) mostly correspond to low MST SHAP ranges (ranging from −0.4 to 0.2) and vice versa. Larger SHAP sensitivity (many dots below −0.4 in Fig. 4c) corresponds to higher MST (>285 K) as compared to the lower range, indicating a seasonal difference in wind speed response to surface temperature, together with surface roughness. For example, the Great Lakes region is more likely to have fully grown vegetation during the warm season (May to October), which will substantially increase surface roughness and decrease wind speed (resulting in negative SHAP values). This pattern also corroborates previous studies’ findings on winter seasonality associated with stronger wind speeds8,12.

Besides seasonal variations, differences in temperature between the land and lake surface (L-L) create pressure gradients that may induce the lake-land breeze. The difference in surface pressure between land and the Great Lakes (DiffSP, calculated as lake surface pressure—land surface pressure) ranked fourth and is higher than the L-L’s rank (7th) because the pressure difference more directly controls synoptic-scale winds or local winds, such as the lake-land breeze. Our data indicate that the Great Lakes always have higher pressure than the surrounding land area in Michigan, and the DiffSP values are all positive. We can observe that positive SHAP contributions occur in both warmer and colder seasons (blue and red in GSLT), while negative contributions are predominantly observed in colder seasons (blue GSLT). The cold season pattern can be attributed to a local high-to-low pressure gradient from land to lakes (east to west) that opposes the large-scale pressure gradient, which normally causes the prevailing winds in this region to blow from the northwest. However, the westerly prevailing wind could be strengthened by the lake wind from warmer seasons since they are in the same direction. Interestingly, the SHAP plot indicates that lower DiffSP values (<1075 Pa) generally correspond to positive SHAP contributions and vice versa (Fig. 4d). The reason for this pattern is not clear, possibly due to the averaging of wind magnitudes without accounting for wind directions and possible major controlling of the prevailing winds over the local winds (lake and land breeze due to the pressure difference between lake and land) as well as more detailed interactions between prevailing winds and local winds.

Teleconnection variables also show their importance in controlling the monthly wind speed in Michigan, which include ENSO_CAI (6th), WP (9th), Niño 4 (10th), NAO (11th), and AO (12th). These indices play a lesser role than regional and local features, but they still impact wind speeds. ENSO_CAI (Fig. 5a) ranks as the most important teleconnection variable, indicating that cooler Tropical Pacific Sea surface temperatures (SSTs) correspond with higher Michigan wind speeds, suggesting that La Niña episodes are generally more responsible for increased wind speeds than El Niño phases. A previous study also identified that La Niña events correspond to cooler and stormier conditions in the northern United States and have a greater influence on summer wind speeds, with lesser effects on spring wind speeds8. Most other ENSO indices (Fig. S7) exhibit a similar pattern, except for Niño 4, which displays a non-monotonic relationship with the SHAP value. The Niño 4 measures the westernmost part of the Niño region, and its remote control on climate in North America could be complex. The Western Pacific (WP) can impact North American surface air temperature, having even greater influence over wintertime surface air temperatures than the Pacific North American (PNA) or ENSO25. Some studies have also mentioned that a positive WP phase can lead to colder and drier conditions in the central and eastern US25,26, contributing to stronger winds in the Great Lakes Regions. Our SHAP analysis revealed that WP with values between 1 and 2 makes a positive contribution to wind speeds in Michigan. The North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO) and Arctic Oscillation (AO) are two indices correlated with each other27,28,29. Our result indicates that more abnormal NAOs (< −1 or >1) generally have negative contributions to Michigan wind speed, while stronger phases of AO (>1) majorly positively contribute to wind speed. The positive phase of the AO usually works in tandem with the negative phase of the NAO and ultimately strengthens midlatitude westerlies, which has some effect on surface wind speeds30,31.

Discussion

This study provides insight into the relationship between Michigan’s wind speeds, local climate features, and teleconnections. The overall wind speed spatial and temporal patterns in Michigan are similar to those in previous works8,12, showing highs in winter and lows in summer, with the greatest variability occurring in fall and winter8. The XGBoost machine learning algorithm, combined with SHAP analysis, successfully models monthly wind speeds, achieving an R² value of 0.96 and an RMSE of 0.12 m/s−1. Previous studies have identified a stilling trend in surface wind speed over land globally before 201032, and the stilling trend was attributed to the increase of surface roughness introduced by more biomass and changes in global circulation32,33. However, this stilling trend was reversed around 2010 and could be explained by multidecadal variabilities, such as the PDO and NAO34,35. We found that the ERA5-Land data do not yield a statistically significant trend in annual wind speeds over the state of Michigan over 70 years, but there is a reduction in variability. This reduced wind variability partially agrees with the stilling trends discovered from contemporary global and regional studies8,32,33,36,37,38. Michigan is surrounded by the Great Lakes and therefore has a unique spatial distribution of surface roughness and varied thermodynamic forcings of winds from the surface. We identified different temporal trends between the coastal and inland counties, with inland counties demonstrating the stilling and more pronounced reduction in variability of the surface winds (Fig. S4). The patterns of reduction in wind variability and inland/coastal difference are controlled by the interplay of changes in both surface roughness and large-scale circulation environment in the study area. Previous global-scale studies also demonstrated differences in trends between ocean and land, while the ocean demonstrated increasing surface wind speed33,39, the land showed stilling winds over the same period32,34,35,38. The trend could also be influenced by the uncertainties existing in the data assimilation system used by the ERA5 reanalysis, such as the land surface process parameterization, as multiple studies have reported the discrepancies in surface wind between the in-situ observations and reanalysis products, including ERA534,38,40,41,42. Our explainable Machine Learning model first identifies those local environmental variables, including the distance to the lakeshore and surface roughness, that play primary roles in controlling surface winds in Michigan. The regional surface temperature is closely related to the seasonality of surface roughness and prevailing winds, ranking as the third most important variable in the model. Surface pressure differences between the Great Lakes and land all have positive values, possibly due to the latitudinal gradient in air pressure, and more Great Lakes areas are located at higher latitudes than the State of Michigan. Another explanation for this is the lower elevations of the Great Lakes compared to the land. However, pressure differences correspond to positive and negative contributions to Michigan wind speed at different ranges, possibly reflecting both synoptic and local controls of surface winds in Michigan, which also vary by season.

The machine learning model also demonstrates interesting relationships between teleconnection variables and Michigan wind speed from the Pacific and Atlantic oceans. ENSO events are connected to wind speeds in Michigan, where the ENSO Climate Adjusted Index is the top-performing index in the model. This finding aligns with past research, which suggests that lower mean wind speeds characterize El Niño periods and have a strong influence over cooler seasons, while stronger winds are associated with La Niña phases8,14. Most ENSO indices included in this study found lower wind speeds correlated with El Niño events and greater speeds during La Niña events. While ENSO_CAI (30-year moving average of the Niño 3.4 SST) was not considered in previous studies and only PDO was mentioned to have close relationship to surface winds in Asia34, the ENSO_CAI has a greater feature importance than other teleconnections (Fig. 3) in our ML model, suggesting the importance of multidecadal variabilities in teleconnections in controlling regional surface winds in Michigan.

Multiple previous studies also demonstrated a positive relationship between the NAO and surface wind in North America43,44,45. Shadbolt also discovered stronger winds over the Lower Peninsula of Michigan in the spring during a positive NAO phase. At the same time, there are increased winds from the North and decreased winds in the South during negative NAO phases14. The general theory is that the NAO modulates the large-scale atmospheric pressure field and the location of the Jet Stream43,44,45, thereby changing the weather regime, such as the Arctic High44, with significant implications for surface wind in North America. However, no linear correlation is evident between the NAO and mean monthly wind across Michigan (Fig. S3). The machine learning model indicates higher sensitivities of wind speed responses (negative) when NAO is in either a negative or positive phase (Fig. 5c), and strong negative SHAP contributions to wind are observed at negative NAO values (<−1). These nonlinear wind responses to NAO can be attributed to compounding factors, including the local wind forcing factors, surface roughness, and other teleconnection factors such as ENSO (which highly covariates with the NAO in our model) and PNA.

Our study demonstrates that the XGBoost-SHAP values successfully model and explain the multiscale physical processes governing surface wind speed in Michigan, providing essential information for renewable energy generation. Future studies need to combine the analysis with the variability of wind direction changes at a more granular temporal and spatial scale, which could help to explain some of the interesting patterns (e.g., the pattern that a smaller range of pressure difference between lake and land has a positive contribution to wind SHAP values) we discovered from the monthly wind data analysis. The polar vortex is an important winter climate phenomenon in the Great Lakes region, and its strength and location are heavily influenced by El Niño and La Niña46. How the polar vortex influences the wind variability in Michigan could also be better elucidated when accounting for wind direction. Winds at different altitudes, such as 100 m, could be modeled to provide a more comprehensive reference for wind electricity generation. Finally, we could set up idealized physical model experiments (e.g., the Weather Research and Forecasting Model, WRF) to isolate factors and test novel relationships identified from the machine learning framework.

Methods

Datasets

We obtained a long-term 70-year hourly wind climatology from the ERA5-Land reanalysis within a boundary of (40°N–50°N; 94°W–75°W). ERA5-Land is created from ERA5 by forcing the land surface component with the atmospheric model without coupling them47. ERA5-Land provides hourly data and offers a high spatial resolution of 0.1° (~9 km) from 1950 to the present. We obtained ‘u10’ and ‘v10’, which are wind vectors at 10-m heights above the Earth’s surface. These variables were used to calculate the wind speed magnitudes, which were then averaged at a monthly resolution.

The ERA5-Land is chosen as the main data source for this study because it improves the original ERA5 product by including the state-of-the-art land surface modeling47, and it provides a combination of higher spatial/temporal resolution (0.1°/hourly) and longer duration (>70 years) as compared with other reanalysis products such as NCAR/NCEP Reanalysis, MERRA-2, NARR, and CFSR48. Other studies have found ERA5 superiority over MERRA2 when assessing wind power49. It was also discovered that ERA5-Land performs best for lower wind speeds when compared with the ERA-Interim and ERA550.

We also derived the following features from the ERA5 single-level monthly-averaged reanalysis dataset51 for the machine learning model, including surface roughness, skin temperature, and surface pressure, as the source data for local and regional predictors of wind speed. The local climate features are averaged over the Great Lakes and Michigan land areas to quantify their impact on wind speeds in the model. A list of all acronyms and their descriptions can be found in Supplementary Information Table 1 (Table S1).

Next, monthly teleconnection indices were retrieved from the Physical Sciences Laboratory of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration52. These indices include Niño 1 + 2, Niño 3, Niño 3.4, Niño 4, and the Oceanic Niño Index, which are related to ENSO. We also included the long-term climate adjustment of the ENSO index, ENSO_CAI, defined as the 30-year moving average value of the Ocean Nino Index (ONI, measured as the SST of the Niño 3.4 region) centered at the current month. The ENSO_ANOM represents the departure of the observed SST values from the ENSO_CAI53 for the current month. Other indices include the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO), Arctic Oscillation (AO), Pacific North American (PNA), Western Pacific (WP), East Atlantic Western Russia (EA_WR), Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO), North Pacific Pattern (NPP), Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation (AMO), and the Atlantic Meridional Mode (AMM). More details about teleconnection variables can be found in Table S1.

In total, eight physiographic variables were acquired directly from or calculated from ERA5 and ERA5-Land datasets, while 16 teleconnection indices were retrieved as inputs into the machine learning model. Hourly ERA-Land wind and the ERA5 Data were averaged for each county in Michigan by month. The monthly wind data were combined with the monthly teleconnection data for statistical analysis and training of the machine learning model. The study period spans from January 1950 to June 2020, yielding 846 monthly observations. There are 83 counties within Michigan; 846 × 83 = 70,218 rows of data for each variable in the dataset. We have applied the 4-year moving average and Mann-Kendall test (‘pymannkendall’ python package) to analyze the annual wind speed time series for Michigan54. Next, a spectral analysis is conducted for the monthly Michigan wind speed and selected teleconnection index using Python and Jupyter Notebook. Spectral analysis transforms data via the Fourier transform to find matching periodicities between climate phenomena55. The logarithmic y-axis displays the signal’s power, where a higher amplitude connotes a higher significance. A Pearson’s correlation matrix was developed for all variables in the study (Fig. S3) to examine linear relationships between wind speed and various feature variables.

Machine learning

The data was input into a machine learning model to capture complex relationships between the variables in the data, including non-linearity. The eXtreme Gradient BOOSTing (XGBoost) was employed in this study for its ease of use and scalability56. Compared with other learning models like linear regression and neural networks, XGBoost has shown more accurate forecasting of wind speeds20. XGBoost is a model-agnostic, non-parametric algorithm that can handle non-stationary spatial and temporal data. This state-of-the-art tree boosting algorithm easily extracts information that is difficult to detect through traditional methods56. Shapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) analysis uses the XGBoost algorithm to interpret and visualize the machine learning output.

XGBoost is a tree-based algorithm that improves the original gradient-boosting decision tree algorithm56. XGBoost combines the outputs of weak learners in a sequence to perform better, integrating many classification and regression trees using gradient boosting, which has effectively solved regression problems. The data fed into XGBoost uses an 80/20% split ratio for this study’s training and testing data. The regression tree was iterated 1623 times to yield the final model, which was the optimal iteration with the lowest root mean squared error (RMSE) value. The model was validated using 5-fold cross-validation, a technique that is more accurate than other validation models (holdout) due to its reduction of variance and overfitting57. We used the K-folds method to monitor the RMSE values during the iterations of the trees and the training/testing split, where the values incrementally increased until the RMSE stopped decreasing, informing us which split and number of trees were most appropriate. The final model was validated using RMSE and R2 based on the 20% testing sample.

SHAP analysis can be applied to machine learning models to interpret and visualize their output. The SHAP analysis, rooted in game theory, assigns values to each ‘player’ (feature variable) in the ‘game’ (model) to evaluate their impact23. This technique can effectively visualize XGBoost models and enhance their interpretability22. This study used the ‘shap’ package, employing Python programming to create graphs and plots from the XGBoost model24. The beeswarm plot orders the features in terms of their importance from greatest to least impact on the model.

The SHAP scatter plot further contextualizes this, providing an individual scatter plot for each feature variable in the model. Along the x-axis are the values from the data in their native units, as denoted by the plot title. We also include the histogram showing the distribution of each feature variable along each x-axis. The y-axis represents the impact these values have on wind speed, where values above zero positively affect wind speeds (faster) and values below zero negatively impact wind speeds (slower), all compared to the mean prediction. The coloration in these graphs is derived from the variable with the greatest interaction effect with the x-axis feature variable. These visualizations are crucial in interpreting the modeling results and fostering a deeper understanding of the complex relationships within the model and data.

Data availability

A core section of the data and code relevant to this manuscript has been shared as part of this work: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15226084.

References

Soeder, D. J. Fossil Fuels and Climate Change. In Proc. Fracking and the Environment: A scientific assessment of the environmental risks from hydraulic fracturing and fossil fuels (ed. Soeder, D. J.) 155–185 https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-59121-2_9. (Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2021).

Kumar, R. & Bansal, H. O. Shunt active power filter: current status of control techniques and its integration to renewable energy sources. Sustain. Cities Soc. 42, 574–592 (2018).

Pryor, S. C., Barthelmie, R. J., Bukovsky, M. S., Leung, L. R. & Sakaguchi, K. Climate change impacts on wind power generation. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 1, 627–643 (2020).

Pryor, S. C. & Barthelmie, R. J. Assessing climate change impacts on the near-term stability of the wind energy resource over the United States. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108, 8167–8171 (2011).

Haslett, J. & Raftery, A. E. Space-time modelling with long-memory dependence: assessing Ireland’s wind power resource. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. C. 38, 1–21 (1989).

Ropelewski, C. F. & Halpert, M. S. North American Precipitation and Temperature Patterns Associated with the El Niño/Southern Oscillation (ENSO). Month. Weather Rev. 114, 2352–2362 (1986).

Bjerknes, J. Atmospheric teleconnections from the equitorial Pacific. Month. Weather Rev. 97, 163–172 (1969).

Li, X., Zhong, S., Bian, X. & Heilman, W. E. Climate and climate variability of the wind power resources in the Great Lakes region of the United States. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos 115, 1–15 (2010).

Diaz, H. F., Hoerling, M. P. & Eischeid, J. K. ENSO variability, teleconnections and climate change. Int. J. Climatol. 21, 1845–1862 (2001).

Fraedrich, K. An ENSO impact on Europe? - A review. Tellus A Dyn. Meteorol. Oceanogr. 46, 541 (1994).

Klink, K. Atmospheric circulation effects on wind speed variability at turbine height. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 46, 445–456 (2007).

Klink, K. Climatological mean and interannual variance of United States surface wind speed, direction and velocity. Int. J. Climatol. 19, 471–488 (1999).

Eichenlaub, V. L. Lakes, effects on climate. in Climatology 534–539 https://doi.org/10.1007/0-387-30749-4_103. (Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, 1987).

Shadbolt, R. P. Associating Michigan climate with low-level airflow trajectories and atmospheric teleconnections. Clim. Res. 55, 135–151 (2012).

Rodionov, S. N. Association between Winter Precipitation and Water Level Fluctuations in the Great Lakes and Atmospheric Circulation Patterns. J. Clim. 7, 1693–1706 (1994).

Meng, L. & Zhu, L. Statistical modeling of monthly and seasonal Michigan snowfall based on machine learning: a multiscale approach. Artif. Intell. Earth Syst. 2, e230016 (2023).

Liu, Y.-C. et al. Climatology of Diablo winds in Northern California and their relationships with large-scale climate variabilities. Clim. Dyn. 56, 1335–1356 (2021).

Lyons, W. A. The climatology and prediction of the Chicago lake breeze. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 11, 1259–1270 (1972).

Winkler, J. A., Arritt, R. W. & Pryor, S. C. Climate Projections For The Midwest: Availability, Interpretation and Synthesis (Island Press, 2012).

Cai, R. et al. Wind speed forecasting based on extreme gradient boosting. IEEE Access 8, 175063–175069 (2020).

Xiong, X., Guo, X., Zeng, P., Zou, R. & Wang, X. A short-term wind power forecast method via XGBoost hyperparameter optimization. Front. Energy Res. 10, 905155 (2022).

Zhu, L., Wang, Y., Chavas, D., Johncox, M. & Yung, Y. L. Leading role of Saharan dust on tropical cyclone rainfall in the Atlantic Basin. Sci. Adv. 10, 30 (2024).

Shapley, L. S. Notes on the N-Person Game — II: The Value of an N-Person Game. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_memoranda/RM0670.html (1951).

Lundberg, S. M. et al. From local explanations to global understanding with explainable AI for trees. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2, 56–67 (2020).

Linkin, M. E. & Nigam, S. The North Pacific oscillation–west pacific teleconnection pattern: mature-phase structure and winter impacts. J. Clim. 21, 1979–1997 (2008).

Dai, Y. & Tan, B. Two types of the Western Pacific pattern, their climate impacts, and the ENSO modulations. J. Clim. 32, 823–841 (2019).

Hamouda, M. E., Pasquero, C. & Tziperman, E. Decoupling of the Arctic Oscillation and North Atlantic Oscillation in a warmer climate. Nat. Clim. Chang. 11, 137–142 (2021).

Kriesche, P. & Schlosser, C. A. The Association of the North Atlantic and the Arctic Oscillation on Wind Energy Resource over Europe and its Intermittency. Energy Procedia 59, 270–277 (2014).

Budikova, D. Northern hemisphere climate variability: character, forcing mechanisms, and significance of the North/Arctic oscillation. Geogr. Compass 6, 401–422 (2012).

Zhou, S., Miller, A. J., Wang, J. & Angell, J. K. Downward-propagating temperature anomalies in the preconditioned polar stratosphere. J. Clim. 15, 781–792 (2002).

Ambaum, M. H. P., Hoskins, B. J. & Stephenson, D. B. Arctic oscillation or North Atlantic oscillation? J. Clim. 14, 3495–3507 (2001).

Vautard, R., Cattiaux, J., Yiou, P., Thépaut, J.-N. & Ciais, P. Northern Hemisphere atmospheric stilling partly attributed to an increase in surface roughness. Nat. Geosci. 3, 756–761 (2010).

Young, I. R., Zieger, S. & Babanin, A. V. Global trends in wind speed and wave height. Science 332, 451–455 (2011).

Zeng, Z. et al. A reversal in global terrestrial stilling and its implications for wind energy production. Nat. Clim. Chang. 9, 979–985 (2019).

Zeng, Z. et al. Global terrestrial stilling: Does Earth’s greening play a role? Environ. Res. Lett. 13, 124013 (2018).

Wallin, A., Conroy, J. L., Ford, T., Atkins, J. & Karamperidou, C. Recent wind stilling across Illinois. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 2023, A11M–2178 (2023).

Wu, J., Zha, J., Zhao, D. & Yang, Q. Changes in terrestrial near-surface wind speed and their possible causes: an overview. Clim. Dyn. 51, 2039–2078 (2018).

Rahman, S. S. Testing “Global Stilling” with ERA-5 Reanalysis Data (Texas Tech University, 2023).

Zheng, C. W., Pan, J. & Li, C. Y. Global oceanic wind speed trends. Ocean Coast. Manag. 129, 15–24 (2016).

Draeger, C., Radić, V., White, R. H. & Tessema, M. A. Evaluation of reanalysis data and dynamical downscaling for surface energy balance modeling at mountain glaciers in western Canada. Cryosphere 18, 17–42 (2024).

Fan, W. et al. Evaluation of global reanalysis land surface wind speed trends to support wind energy development using in situ observations. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 60, 35–50 (2021).

Molina, M. O., Gutiérrez, C. & Sánchez, E. Comparison of ERA5 surface wind speed climatologies over Europe with observations from the HadISD dataset. Int. J. Climatol. 41, 4864–4878 (2021).

Laurila, T. K., Sinclair, V. A. & Gregow, H. Climatology, variability, and trends in near-surface wind speeds over the North Atlantic and Europe during 1979–2018 based on ERA5. Int. J. Climatol. 41, 2253–2278 (2021).

Liu, Y., Feng, S., Qian, Y., Huang, H. & Berg, L. K. How do North American weather regimes drive wind energy at the sub-seasonal to seasonal timescales? npj. Clim. Atmos. Sci. 6, 100 (2023).

Manthos, Z. H., Pegion, K. V., Dirmeyer, P. A. & Stan, C. The relationship between surface weather over North America and the Mid-Latitude Seasonal Oscillation. Dyn. Atmos. Oceans 99, 101314 (2022).

Garfinkel, C. I. & Hartmann, D. L. Different ENSO teleconnections and their effects on the stratospheric polar vortex. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos 113, 1–14 (2008).

Muñoz-Sabater, J. et al. ERA5-Land: a state-of-the-art global reanalysis dataset for land applications. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 13, 4349–4383 (2021).

Gualtieri, G. Analysing the uncertainties of reanalysis data used for wind resource assessment: a critical review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 167, 112741 (2022).

Olauson, J. ERA5: the new champion of wind power modelling? Renew. Energy 126, 322–331 (2018).

Clelland, A. A., Marshall, G. J. & Baxter, R. Evaluating the performance of key ERA-Interim, ERA5 and ERA5-Land climate variables across Siberia. Int. J. Climatol. 44, 2318–2342 (2024).

Copernicus Climate Change Service. ERA5 monthly averaged data on single levels from 1940 to the present. Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) Climate Data Store (CDS) https://doi.org/10.24381/CDS.F17050D7 (2019).

Monthly Climate/Ocean Indices (Time-Series): NOAA Physical Sciences Laboratory. https://psl.noaa.gov/data/timeseries/month/.

Climate Prediction Center - Monitoring & Data: Ocean Niño Index Changes Description. https://origin.cpc.ncep.noaa.gov/products/analysis_monitoring/ensostuff/ONI_change.shtml.

Hussain, M. M. & Mahmud, I. pyMannKendall: a Python package for non-parametric Mann-Kendall family of trend tests. J. Open Source Softw. 4, 1556 (2019).

Epstein, E. S. A spectral climatology. J. Clim. 1, 88–107 (1988).

Chen, T. & Guestrin, C. XGBoost: a scalable tree boosting system. In Proc. 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining 785–794 https://doi.org/10.1145/2939672.2939785. (ACM, San Francisco, 2016).

Natras, R., Soja, B. & Schmidt, M. Ensemble machine learning of random forest, AdaBoost and XGBoost for vertical total electron content forecasting. Remote Sens. 14, 3547 (2022).

Acknowledgements

C.E. acknowledges the support from the Harrison Endowment, funded by the School of Environment, Geography, and Sustainability at Western Michigan University. L.Z. acknowledges the support from the NSF grant #2432625.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: C.E. and L.Z. Methodology: C.E. and L.Z. Data analysis: C.E. Visualization: C.E. Writing—original draft: C.E., L.Z. Writing—review and editing: C.E., L.Z., K.B. and L.M.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Evans, C., Zhu, L., Baker, K. et al. Unveiling multiscale drivers of wind speed in Michigan using machine learning. npj Clim Atmos Sci 8, 286 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-01166-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-01166-x