Abstract

Climate models exhibit substantial inter-model spread in climate sensitivity, typically attributed to uncertainty in cloud feedbacks. In contrast, the influence of clear-sky shortwave absorption (SWA) remains underexplored, despite its substantial uncertainty. Using a single-model framework, we systematically perturb SWA and impose CO₂ quadrupling on distinct mean states that differ in SWA, allowing assessment of its impact on both the mean climate and the CO₂-driven response. Enhanced SWA reduces surface shortwave radiation, leading to Arctic cooling. Under higher SWA, CO₂ forcing drives increased advection of colder Arctic air into the subpolar North Atlantic, enhancing turbulent heat loss and facilitating AMOC recovery. This accelerated recovery amplifies warming in the subpolar North Atlantic, strengthens lapse rate and shortwave cloud feedbacks, and ultimately increases climate sensitivity over time. These findings reveal a previously overlooked pathway by which clear-sky SWA modulates long-term climate feedback, underscoring the need to better constrain SWA in climate models.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The fidelity of climate models in projecting the future climate hinges on their ability to accurately simulate the mean climate state1. However, achieving this fidelity is challenging due to uncertainties in the parameterizations of various physical processes, with the most prominent uncertainty often attributed to cloud-related mechanisms2,3. In contrast, clear-sky radiation processes are generally considered more certain. Nevertheless, the inter-model spread in shortwave radiation absorbed by the atmosphere primarily originates from the clear-sky rather than clouds. For example, 96.6% of the inter-model spread in global mean shortwave absorption, amounting to 8.6 W/m2, results from the clear-sky4. Much of this spread stems from the parameterization of shortwave absorption by water vapor, particularly in the degree of absorptivity for a given amount of water vapor5. In order to assess the effect of this uncertainty in isolation, a previous study5 employed a climate model experiment where the water vapor shortwave absorptivity was altered to mimic the range of the inter-model spread in global mean atmospheric shortwave absorption (SWA) in CMIP models. It is noted that this single model approach enables systematic isolation of the SWA bias. In contrast, a CMIP multi-model analysis would obscure this effect due to the confounding influence of numerous other inter-model differences. Enhanced SWA decreases the amount of shortwave radiation reaching the surface, leading to global mean surface cooling, with this effect being most amplified over the eastern tropical Pacific and the Arctic. Given the state-dependent nature of climate feedback6, the varying mean states due to SWA modifications are anticipated to influence climate projections. Hence, we aim to investigate the sensitivity of climate projections to SWA by increasing CO2 concentrations in control climates that differ in SWA within the range of CMIP uncertainty. Large inter-model SWA uncertainty, despite being well constrained by observations, underscores the need to assess its impact on climate projections4,5,7,8,9.

Modifications to SWA drive surface temperature changes that are amplified in the Arctic region5. Consequent changes in sea ice extent and freshwater fluxes potentially modulate the strength of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC)10,11,12. Indeed, enhanced SWA-induced Arctic cooling is concurrent with warming over the subpolar North Atlantic5, suggestive of a strengthened AMOC13. Meanwhile, the inter-model spread in AMOC strength is one of the factors contributing to uncertainty in climate feedback14. For example, models with stronger AMOC recovery tend to show larger warming in the northern hemisphere mid-latitudes, leading to more positive lapse rate and cloud feedbacks, thus projecting a larger increase in net climate feedback14. Taken together5,14, we hypothesize that biases in the present-day SWA can modulate net climate feedback and sensitivity through its influence on AMOC strength.

While uncertainty in SWA has been previously highlighted in the context of projected changes in hydrologic cycle7, here we identify its contribution to global climate feedback and sensitivity. First, we examine the impact of varying SWA on the mean state in the pre-industrial (hereafter “PI”) control climate, revealing a pronounced sensitivity of the climatological AMOC strength to SWA. We then assess whether the climate response to an abrupt quadrupling of CO2 concentrations (hereafter “4xCO2”) depends on SWA, and find that the evolution of the CO2-driven AMOC response differs markedly with SWA amplitude. Lastly, we show that differences in AMOC recovery modulate the evolution of climate feedback over time in the 4xCO2 experiments. While most studies have focused on cloud feedbacks as the primary source of uncertainty in climate feedback and sensitivity15,16,17, our results suggest that clear-sky SWA may also play a role.

Results

Impact of uncertainties in water vapor SW absorption on the mean AMOC strength

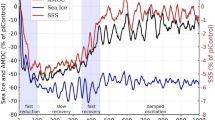

We perform the experiments where the water vapor SW absorptivity constant k is altered from 60% to 120% of the default value in the PI simulation of CESM1.2.2 model (Methods), which are respectively denoted as 0.6X, 0.8X, 1.0X, and 1.2X. The two extreme cases (i.e., 1.2X and 0.6X) show a difference in SW absorption of 7.6 W/m2 in the global mean, comparable to the inter-model range of 10.5 W/m2 in CMIP5/6 ensemble5. With enhanced atmospheric SW absorption for larger k values, the SW radiation reaching the surface decreases, thereby causing global surface cooling. For example, the global mean surface temperature decreases by 0.27 K as k is increased from 0.6X to 1.2X, with a more pronounced decrease of 1.40 K in the Arctic (Fig. 1a). The amplified surface cooling over the Arctic is due to enhanced sea ice fraction and consequential sea ice-albedo feedback (Fig. 1a)18. The resulting reduction in the ocean freshwater flux increases the surface salinity in the Arctic (Fig. 1b). The surface salt flux budget indicates that the decrease in freshwater flux from sea ice melting is the dominant cause for enhanced salt flux over the Arctic (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Difference between 1.2X and 0.6X of a surface temperature (Ts) and sea ice fraction (cyan contours outline regions where the sea ice fraction increases by more than 0.05 in 1.2X compared to 0.6X), b sea surface salinity, c sea surface density, and d boreal winter (December–March) MLD. The Irminger and Labrador Seas are defined by the regions where the March MLD exceeds 800 m, indicated respectively by black dashed and solid lines in (c) and (d). Hatching indicates the regions with the response insignificant at 95% confidence level based on the two-sided t test.

In contrast to the Arctic cooling due to increased water vapor SW absorptivity, the subpolar North Atlantic exhibits a significant surface warming (Fig. 1a), indicative of the strengthened AMOC13. Indeed, the AMOC strength increases with k in the PI condition (left panel of Fig. 2a). The strengthening of AMOC occurs consistently at all depths (Supplementary Fig. 2). The AMOC strengthens with larger k because the climatological deep convection regions, such as the Irminger Sea and Labrador Sea (black solid and dashed contours in Fig. 1c, d), become denser associated with surface cooling (Fig. 1a, c). Note that changes in salinity due to k alterations in the PI condition are not responsible for the density changes over these deep convection regions (Supplementary Fig. 3a). Colder denser water mass with larger k promotes deep convection, as evidenced by a deepening of the wintertime mixed layer depth (MLD; Fig. 1d) in both the Irminger Sea and Labrador Sea (left panels of Fig. 2b, c), thereby leading to a strengthening of the AMOC.

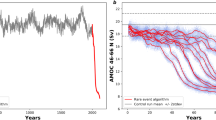

Timeseries of a AMOC strength (defined as the maximum stream function at 26°N below 500 m depth), b Irminger Sea MLD, and c Labrador Sea MLD. The left panels display the last 50-year average of the control PI simulations, with error bars indicating one standard deviation. The right panels show the annual timeseries (thin line) along with a 9-year moving average (thick line) after abrupt 4xCO2.

Put together, an increase in shortwave absorption by water vapor results in the surface cooling of the Irminger and Labrador Seas, raising the density of the near-surface water, which in turn enhances deep convection and strengthens the AMOC. This underscores that uncertainties in clear-sky SW absorption can extend to create uncertainties even in the AMOC. We now examine the sensitivity of the CO2-driven AMOC response to water vapor SW absorptivity k.

Impact on the CO2-forced AMOC and global atmospheric circulation changes

To assess the effect of the water vapor SW absorptivity on the CO2-forced changes, we abruptly quadruple CO2 concentrations (i.e., 4xCO2) to all PI simulations with varying k values. In response to 4xCO2, the AMOC weakens regardless of k values for about 30 years (Fig. 2a). However, beyond this initial weakening phase, the AMOC response diverges based on the k value. The AMOC recovery is delayed with smaller k, but the smallest k case (i.e., 0.6X) shows no recovery for additional 130 years (Supplementary Fig. 4). In contrast, the 1.0X and 1.2X cases converge by year 150 (Fig. 2a). This nonlinear behavior suggests that the AMOC response undergoes a regime shift modulated by SWA.

The different behavior of AMOC evolution for different k values can be understood from the varying degrees of deep convection recovery, quantified by changes in MLD and the near-surface water density. While both the Labrador Sea and the Irminger Sea are key deep convection sites, they exhibit distinct responses due to differing degrees of freshwater influence19. In the Labrador Sea, the MLD shoals markedly approximately two decades after 4xCO2 and remains shallow thereafter, regardless of k (Fig. 2c). This is because freshwater from Arctic sea ice melt and land runoff is transported directly along the western boundary current into the Labrador Sea19,20. In contrast, the Irminger Sea is affected more indirectly, via freshwater redistribution associated with subpolar gyre adjustments, and shows a recovery of MLD (Fig. 2b)20. Indeed, mixed layer shoaling speed is delayed more in the Irminger Sea (Fig. 2b, c). Hence, we proceed to understand the transient behavior of the CO2-induced MLD and near-surface density changes in the Irminger Sea.

In all cases, the Irminger Sea mixed layer contracts during the initial 30 years after 4xCO2 (Fig. 2b). The contraction during the first 10-15 years is primarily driven by a reduction in the density of near-surface water due to CO2-induced warming (blue lines in Fig. 3a, b)10. Lowering of the density thereafter is more dominantly caused by freshening (red lines in Fig. 3a, b). A reduction in near-surface water density (Fig. 3) and the contraction of the mixed layer (Fig. 2b) indicate suppressed deep convection, leading to a weakening of the AMOC (Fig. 2a). While the initial response is relatively insensitive to k values, it becomes increasingly sensitive after around four decades. The MLD begins to recover, with a more pronounced delay in cases with smaller k values – except for the 0.6X case, which shows no recovery. This behavior points to a potential tipping threshold in the AMOC response modulated by the k value (Fig. 2b).

Response of Irminger Sea upper 1000 m depth density to 4xCO2 (δρ; black solid), with contributions from salinity (red) and temperature (blue) changes, as well as their combined effect (black dashed) in a 0.6X and b 1.2X. c Difference between panels b and a. The plots include both the annual timeseries (thin line) and a 9-year moving average (thick line).

The evolution of near-surface density in the Irminger Sea, as well as its nonlinear sensitivity to k, is determined more by salinity changes than temperature changes (Fig. 3). The larger increase in salinity contribution in the higher k case (Fig. 3c) is mainly due to increased surface salt flux, particularly the evaporation minus precipitation, with a smaller contribution from salt advection (Supplementary Fig. 5). The larger increase in evaporation for higher k values results from the greater air-sea temperature contrast (Supplementary Fig. 6a, b), as colder Arctic air (Fig. 1a) is advected into the region by the climatological northerly winds (Supplementary Fig. 7a, c), enhancing turbulent heat loss over the subpolar North Atlantic. Similarly, increased surface heat loss due to the advection of cold, dry Arctic air has been shown to be instrumental in strengthening the AMOC in response to aerosol forcing21,22. The enhanced evaporation due to the larger air-sea temperature contrast makes the Irminger Sea saltier, creating favorable conditions for the recovery of AMOC deep convection. Hence, the initial freshening effect caused by sea ice melt in 1.2X is gradually overtaken by densification from enhanced evaporation, causing the salinity contribution to reverse around four decades after the onset of 4xCO2 (red line in Fig. 3b). This shift aligns with the timing of divergent AMOC response, with recovery in 1.2X and continued weakening in 0.6X (Fig. 2a). A stronger AMOC transports more energy northward (Supplementary Fig. 8), resulting in anomalously warmer Irminger Sea for larger k values (Supplementary Fig. 7b). This surface warming reinforces the effect of the increased air-sea temperature contrast, further amplifying evaporation (Supplementary Fig. 6c), which accelerates the recovery of deep convection in higher k cases and further broadens the gap between different k cases (Fig. 2a).

The distinct evolution of AMOC changes results in systematic differences in large-scale pattern of the CO2-driven climate changes based on the k value. Figure 4 (upper) illustrates the key features of CO2-driven climate change. An increase in CO2 leads to global surface warming, characterized by polar amplification and a North Atlantic warm hole (Fig. 4a)23,24,25. Tropical warming is amplified in the upper troposphere, following the moist adiabat, causing a poleward shift of extratropical jet (Fig. 4b)26. This shift is more prominent in the Southern Hemisphere, as the Northern Hemisphere shows reduced meridional temperature gradients in the lower troposphere due to near-surface warming amplification in the Arctic27,28. The Hadley circulation exhibits an intensification of the ascending branch and a weakening and widening of the subsiding branch (Fig. 4c)29,30. Figure 4 (lower) shows how these features are affected by SW water vapor absorptivity. With larger k, the AMOC recovers faster, thereby transporting more energy northward across the equator in 4xCO2 response (Supplementary Fig. 8). Consequently, surface warming is more amplified in the Northern Hemisphere and less pronounced in the Southern Hemisphere, particularly in the mid-latitudes (Fig. 4d). This temperature response extends to the tropopause, and the resultant changes in meridional temperature gradients induce easterly anomalies in the northern mid-latitudes and westerly anomalies in the southern mid-latitudes (Fig. 4e). A larger hemispheric asymmetry in the temperature response (Fig. 4d) necessitates southward cross-equatorial atmospheric energy transport, thereby inducing a northward shift of the Hadley circulation (Fig. 4f).

The response to 4xCO2 in the 1.0X case for a surface temperature (Ts), b zonal mean atmospheric temperature (Ta, shading) and zonal wind (U, westerly/easterly anomalies in solid/dashed lines, with the contour interval (CI) of 0.5 m s−1), and c zonal mean atmospheric meridional stream function (ψ, shading) and its climatology (clockwise/anti-clockwise in solid/dashed contours, with the CI of 2 ×1010 kg s−1). d–f Similar to (a–c), but for the difference between the two cases (1.2X–0.6X). The CI is 0.2 m s−1 in (e) and 2 ×1010 kg s−1 in (f). Hatching indicates the regions with the response insignificant at 95% confidence level based on the two-sided t test.

Impact on the global climate feedback and sensitivity

We discussed how uncertainties in SW water vapor absorptivity can affect the CO2-driven large-scale circulation changes through its impact on the AMOC recovery. Furthermore, uncertainties in AMOC recovery are previously shown to partly explain the inter-model spread in net climate feedback \(\lambda\) evolution14. Hence, we now move to examine the effect of SW water vapor absorptivity on the global climate feedback and sensitivity.

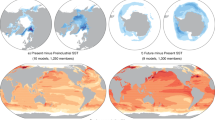

In general, net climate feedbacks \(\lambda\) become less negative, or weaken, over time under CO2 forcing in coupled climate models associated with the evolution of the pattern of SST response31,32,33. Decreasing climate feedbacks over time are also evident in our experiments, with the reduction being more pronounced in the larger k case (Fig. 5a and Supplementary Fig. 9). The changes over the course of the simulations (denoted as \(\Delta\)) are defined as the difference in responses between years 21–150 (hereafter “late period”) and years 1–20 (hereafter “early period”). The maps of SST trend in the early period are similar across different k cases, whereas those in the late period exhibit a strong sensitivity to k (Supplementary Fig. 10). The larger k case shows a relatively stronger warming trend in the North Atlantic during the late period (Fig. 4d and Supplementary Fig. 10f), associated with faster AMOC recovery (Fig. 2a).

a Net climate feedback evolution (Δλ) versus AMOC strength evolution (ΔAMOC). b Difference in Δλ from 0.6X case in 0.8X (blue), 1.0X (yellow), and 1.2X (red), with its decomposition into the contributions from lapse rate feedback (Δλlr), LW cloud feedback (Δλlw,cld), SW cloud feedback (Δλsw,cld), Planck radiative feedback (Δλplk), albedo feedback (Δλalb), SW non-cloud feedback (Δλsw,ncld), and LW water vapor feedback (Δλlw,q). The sum of individual contributions (Sum) well reproduces the actual Δλ. See Methods for details. Difference between 1.2X and 0.6X cases of c Δλlr, d ΔEIS (shading) and Δlow cloud fraction (positive in solid contours, negative in dashed contours, CI = 8%), e Δλcld, and f its zonal mean Δλcld (black) decomposed into shortwave (Δλsw,cld, blue) and longwave (Δλlw,cld, red) components.

To examine how differences in SST pattern changes influence the sensitivity of \(\Delta \lambda\) to k, we decompose \(\Delta \lambda\) into various components using the radiative kernel method and advanced partial radiative perturbation (APRP) method (Methods). The lapse rate feedback \(\Delta {\lambda }_{{\rm{lr}}}\) is the dominant contributor to the enhanced reduction of \(\lambda\) for larger k values (Fig. 5b). A more positive \(\Delta {\lambda }_{{\rm{lr}}}\) with larger k (Fig. 5c) results from stronger SST warming in the subpolar North Atlantic (Fig. 4d), driven by the divergence of the AMOC response between 0.6X and 1.2X cases during the later period (Fig. 2a). In contrast, SST trends during the early period remain similar between the two simulations (Supplementary Fig. 10), supporting the interpretation that the differential AMOC recovery over time is key to the difference in the lapse rate feedback changes \(\Delta {\lambda }_{{\rm{lr}}}\). The amplified warming is most pronounced near the surface (Fig. 4e), destabilizing the lower troposphere, indicated by a more negative \(\Delta {\rm{EIS}}\) (estimated inversion strength, defined as a difference in potential temperature between 700 hPa and the surface34) at higher k (Fig. 5d). A larger reduction in the North Atlantic \({\rm{EIS}}\) results in a larger decrease in low cloud cover14 (dashed line in Fig. 5d), thereby increasing shortwave cloud radiation reaching the surface and further reinforcing SST warming in the region (Fig. 5e, f). The shortwave and longwave components of cloud feedback tend to offset each other at most latitudes except between 30°N and 50°N, where the shortwave component predominates (Fig. 5f). Hence, the net cloud feedback evolution \(\Delta {\lambda }_{{\rm{cld}}}\) contributes only slightly to the total climate feedback evolution \(\Delta \lambda\) in the global mean (Fig. 5b). Nonetheless, the spatial co-location of the enhanced shortwave cloud feedback \(\Delta {\lambda }_{{\rm{sw}}}\) with the peak SST warming (Figs. 4d and 5e) points to the role of regional shortwave cloud feedbacks in amplifying the local SST response. The finding – that AMOC variability modulates lapse rate feedback and, to a lesser extent, cloud feedback, thereby shaping climate feedback and sensitivity – is consistent with an earlier study14.

In sum, the accelerated AMOC recovery, driven by stronger water vapor SW absorptivity, warms the North Atlantic, destabilizes the troposphere, and results in more positive lapse rate and shortwave cloud feedbacks, leading to a larger reduction in net climate feedback over long timescales. Hence, a larger k induces a greater increase in the effective climate sensitivity over time. For example, the effective climate sensitivity (i.e., the x-intercept of the regression lines in Supplementary Fig. 9) increases by 0.41 K in 0.6X from the early to late period, while this difference is amplified to 1.02 K in 1.2X.

Discussion

Here, we reveal how uncertainty in water vapor shortwave absorptivity ultimately impacts climate sensitivity through the intricate coupling between radiation, climate pattern, and the AMOC. Increased SWA reduces the shortwave radiation reaching the surface, leading to a global cooling effect. This cooling is most pronounced in the Arctic due to surface albedo feedback. As surface temperatures drop, the water in deep convection regions such as the Irminger Sea and Labrador Sea becomes denser, which in turn strengthens the AMOC. These differences in the mean state climate due to a varying SWA result in divergent climate responses to increased CO2.

In response to increased CO2, the AMOC weakens as a result of the warming and freshening of surface waters in the Irminger Sea. However, the denser mean-state Irminger Sea for the larger SWA cases creates more favorable conditions for the AMOC recovery, allowing it to recover faster. Conversely, in the case with the smallest SWA, the AMOC undergoes a full collapse with no sign of recovery throughout the entire 280-year 4xCO2 integration, highlighting its nonlinear sensitivity to SWA. The expedited AMOC recovery with enhanced SWA gives rise to an anomalously northward cross-equatorial ocean heat transport, increasing the inter-hemispheric warming contrast. The larger warming in the Northern Hemisphere than the Southern Hemisphere induces a northward shift of the Hadley circulation. Moreover, the faster AMOC recovery with larger SWA accompanies a stronger subpolar North Atlantic warming that promotes the shortwave low-cloud and lapse rate positive feedbacks, leading to a larger effective climate sensitivity. Our study provides an evidence that the current representation of shortwave radiative transfer is at least partially responsible for large discrepancies in climate projections other than global hydrological cycle7,9.

One might question whether the sensitivity of climate feedback to SWA can be explained directly by changes in SWA itself, without invoking differences in AMOC recovery. However, hemispheric warming patterns during the early adjustment period show no discernible contrast across different SWA amplitudes. In contrast, the divergence in hemispheric warming patterns, critical for shaping climate feedback, emerges only in the later phase (Supplementary Fig. 10), coinciding with differences in AMOC evolution across the SWA experiments. Given the atmosphere’s fast adjustment timescale, this temporal separation supports the conclusion that the modulation of climate feedback is primarily driven by differential AMOC recovery rather than the direct radiative effects of altered SWA.

We suggest a potential pathway through which SWA affects climate sensitivity evolution and underscores the need to constrain clear-sky radiative processes. It is suggested that the uncertainty in SWA largely originates from the clear-sky water vapor SW absorption, which is mainly due to the oversimplified and coarse spectral resolution in radiation schemes35. Since some models continue to use relatively coarser spectral resolution compared to other CMIP models7, improving their resolution could help narrow the inter-model spread of SWA and, as a result, reduce uncertainties in climate sensitivity.

It is worth noting that the influence of SWA on the AMOC response and climate sensitivity, as identified in this study, is not evident in the inter-model relationships across CMIP5/6. However, the absence of an inter-model correlation does not preclude a role for SWA, as its effect may be obscured by confounding factors. This highlights the value of a single-model framework, which enables systematic isolation of the SWA contribution. Our aim is not to fully account for the inter-model spread in climate sensitivity, which is likely governed by multiple processes, but rather to extract the specific impact of SWA bias.

Methods

Experiment design

We employ the Community Earth System Model version 1.2.2 (CESM 1.2.2)36, consisting of the Community Atmosphere Model version 4 (CAM4)37, the Community Land Model 4 (CLM4)38, the Parallel Ocean Program version 2 (POP2)39, and Community Ice Code version 4 (CICE4)40. The atmosphere model uses a finite volume grid system with nominal 2° horizontal resolution and 26 vertical layers. The ocean model uses a tripolar grid system with nominal 1° horizontal resolution and 60 vertical layers. We use this single model to assess the effect of atmospheric water vapor SW absorption in separation. This enables us to diagnose the potential effect of the CMIP5/6 inter-model spread in atmospheric water vapor SW absorption.

The inter-model spread of atmospheric water vapor SW absorption comes from the SW absorption sensitivity per unit water vapor in the atmosphere5. According to Collins et al.41, the atmospheric water vapor SW absorption amount is calculated according to the following equation42:

Here, T(u) is the transmission function where i denotes the number of pseudospectral bands that are used, wi is the weight constant for each wavelength, u is the water vapor path, and ki is the effective extinction, which defines the sensitivity of the downward SW absorption by the atmospheric water vapor. Altering the SW absorptivity constant k by 60, 80, 100, and 120% of the default k value enables us to span the inter-model spread of the atmospheric water vapor SW absorption across CMIP5/65. Each case is denoted as 0.6X, 0.8X, 1.0X, and 1.2X, respectively, which is integrated for 150 years under the pre-industrial (i.e., PI) condition, and for additional 150 years after abruptly quadrupling CO2 (i.e., 4xCO2).

Ocean density budget decomposition

The density of the ocean water mass can be expressed as a function of ocean temperature T and ocean salinity S43. The density difference between the two different mean states \({\rm{\delta }}\rho\) can be written as:

where ρ0 is the reference density, α is the thermal expansion coefficient, β is the haline contraction coefficient. Constant ρ0, α and β are calculated as a function of ocean depth using the international thermodynamic equation of seawater 2010 (TEOS-10) tool set44. Hence, the density difference can be decomposed into the contributions from the temperature difference (\(-\alpha {\rm{\delta }}T{\rho }_{0}\)) and the salinity difference (\(\beta {\rm{\delta }}S{\rho }_{0}\)).

Climate feedback analysis

We define the evolution of change in spatial pattern of any target variable X as follows:

where GMT is global mean TAS. Here, we calculate the ordinary least-squares regression at each grid point for the early period (1–20 years after an abrupt 4xCO2) and late period (21–150 years). The evolution of climate feedback over time, Δλ, is derived by setting X as the downward positive global mean net radiation at the top of the atmosphere N. We decompose the longwave component of Δλ using the radiative kernel technique from Soden and Held45, and the shortwave component using the advanced partial radiative perturbation (APRP) method46.

We decompose change in the longwave component of N (LW) using the radiative kernel data from Pendergrass et al.47 as follows:

where the term with subscript κ denotes radiative kernels, δ the response to 4xCO2, Tatm the atmospheric temperature, Tsfc the surface temperature, and q the atmospheric specific humidity. Each term on the RHS represents the radiative effect due to changes in uniform vertical warming (Planck radiative effect; LWplk), non-uniform vertical warming (lapse rate effect; LWlr), specific humidity (LWq), and cloud effect (LWcld). LWcld is calculated by subtracting the masking effect (i.e., \(\delta {{\rm{LW}}}_{{\rm{plk}}}+\delta {{\rm{LW}}}_{{\rm{lr}}}+\delta {{\rm{LW}}}_{{\rm{q}}}\) difference between all-sky and clear-sky) from the LW cloud radiative forcing (i.e., \(\delta\)LW difference between all-sky and clear-sky), following Soden et al.48. We use the APRP method to decompose the shortwave component of N (SW) into the terms due to changes in surface albedo (\(\delta {{\rm{SW}}}_{{\rm{alb}}}\)), cloud (\(\delta {{\rm{SW}}}_{{\rm{cld}}}\)), and noncloud effects (\(\delta {{\rm{SW}}}_{{\rm{ncld}}}\)).

By substituting both the longwave and shortwave components into Eq. (1), we can decompose the net climate feedback changes over time as follows:

Latent heat budget decomposition

Following Jia and Wu49, we decompose the latent heat flux changes (\({\rm{\delta }}{LH}\)) into the contributions from changes in surface temperature (\({\rm{\delta }}\)LHTs), air-surface temperature difference (\({\rm{\delta }}\)LHTd), surface wind speed (\({\rm{\delta }}\)LHwind), and relative humidity (\({\rm{\delta }}\)LHrh), which can be expressed as follows:

The overbar denotes the reference climatology (i.e., PI 50-year mean), δ indicates the change from the reference state. Ts denotes the surface temperature, W the surface wind speed, Tdiff the reference level air temperature minus Ts, RH the relative humidity at model reference level. α is \({L}_{v}/{(R}_{v}\bar{{T}_{{\rm{s}}}^{2}})\), with the latent heat of evaporation Lv = 2.5 ×106 J kg−1 and gas constant for moist air Rv = 461.5 J kg−1 K−1.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Shukla, J., DelSole, T., Fennessy, M., Kinter, J. & Paolino, D. Climate model fidelity and projections of climate change. Geophys. Res. Lett. 33, L07702 (2006).

Karlsson, J., Svensson, G. & Rodhe, H. Cloud radiative forcing of subtropical low level clouds in global models. Clim. Dyn. 30, 779–788 (2008).

Rio, C., Del Genio, A. D. & Hourdin, F. Ongoing breakthroughs in convective parameterization. Curr. Clim. Change Rep. 5, 95–111 (2019).

Wild, M. The global energy balance as represented in CMIP6 climate models. Clim. Dyn. 55, 553–577 (2020).

Kim, H., Pendergrass, A. G. & Kang, S. M. The dependence of mean climate state on shortwave absorption by water vapor. J. Clim. 35, 2189–2207 (2022).

Caballero, R. & Huber, M. State-dependent climate sensitivity in past warm climates and its implications for future climate projections. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 110, 14162–14167 (2013).

DeAngelis, A. M., Qu, X., Zelinka, M. D. & Hall, A. An observational radiative constraint on hydrologic cycle intensification. Nature 528, 249–253 (2015).

Kim, D. & Ramanathan, V. Solar radiation budget and radiative forcing due to aerosols and clouds. J. Geophys. Res. 113, D02203 (2008).

Takahashi, K. The global hydrological cycle and atmospheric shortwave absorption in climate models under CO2 forcing. J. Clim. 22, 5667–5675 (2009).

Levang, S. J. & Schmitt, R. W. What causes the AMOC to weaken in CMIP5?. J. Clim. 33, 1535–1545 (2020).

Liu, W. & Fedorov, A. V. Global impacts of Arctic sea ice loss mediated by the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation. Geophys. Res. Lett. 46, 944–952 (2019).

Li, H. & Fedorov, A. V. Persistent freshening of the Arctic Ocean and changes in the North Atlantic salinity caused by Arctic sea ice decline. Clim. Dyn. 57, 2995–3013 (2021).

McCarthy, G. D. & Caesar, L. Can we trust projections of AMOC weakening based on climate models that cannot reproduce the past?. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A 381, 20220193 (2023).

Lin, Y. J., Hwang, Y. T., Ceppi, P. & Gregory, J. M. Uncertainty in the evolution of climate feedback traced to the strength of the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation. Geophys. Res. Lett. 46, 12331–12339 (2019).

Ceppi, P., Brient, F., Zelinka, M. D. & Hartmann, D. L. Cloud feedback mechanisms and their representation in global climate models. WIREs Clim. Change 8, e465 (2017).

Ceppi, P. & Gregory, J. M. Relationship of tropospheric stability to climate sensitivity and Earth’s observed radiation budget. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 114, 13126–13131 (2017).

Myers, T. A. & Norris, J. R. Reducing the uncertainty in subtropical cloud feedback. Geophys. Res. Lett. 43, 2144–2148 (2016).

Curry, J. A., Schramm, J. L. & Ebert, E. E. Sea ice-albedo climate feedback mechanism. J. Clim. 8, 240–247 (1995).

Zhang, J. et al. Labrador Sea freshening linked to Beaufort Gyre freshwater release. Nat. Commun. 12, 1229 (2021).

Madan, G., Gjermundsen, A., Iversen, S. C. & LaCasce, J. H. The weakening AMOC under extreme climate change. Clim. Dyn. 62, 1291–1309 (2024).

Robson, J. et al. The role of anthropogenic aerosol forcing in the 1850–1985 strengthening of the AMOC in CMIP6 historical simulations. J. Clim. 35, 6843–6863 (2022).

Menary, M. B. et al. Aerosol-forced AMOC changes in CMIP6 historical simulations. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e2020GL088166 (2020).

Holland, M. M. & Bitz, C. M. Polar amplification of climate change in coupled models. Clim. Dyn. 21, 221–232 (2003).

Drijfhout, S., Van Oldenborgh, G. J. & Cimatoribus, A. Is a decline of AMOC causing the warming hole above the North Atlantic in observed and modeled warming patterns?. J. Clim. 25, 8373–8379 (2012).

Caesar, L., Rahmstorf, S., Robinson, A., Feulner, G. & Saba, V. Observed fingerprint of a weakening Atlantic Ocean overturning circulation. Nature 556, 191–196 (2018).

Lorenz, D. J. & DeWeaver, E. T. Tropopause height and zonal wind response to global warming in the IPCC scenario integrations. J. Geophys. Res. 112, D10119 (2007).

Simpson, I. R., Shaw, T. A. & Seager, R. A diagnosis of the seasonally and longitudinally varying midlatitude circulation response to global warming. J. Atmos. Sci. 71, 2489–2515 (2014).

Shaw, T. A. et al. Storm track processes and the opposing influences of climate change. Nat. Geosci. 9, 656–664 (2016).

Lu, J., Vecchi, G. A. & Reichler, T. Expansion of the Hadley cell under global warming. Geophys. Res. Lett. 34, L06805 (2007).

Lau, W. K. & Kim, K. M. Robust Hadley circulation changes and increasing global dryness due to CO2 warming from CMIP5 model projections. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 112, 3630–3635 (2015).

Senior, C. A. & Mitchell, J. F. The time-dependence of climate sensitivity. Geophys. Res. Lett. 27, 2685–2688 (2000).

Andrews, T., Gregory, J. M. & Webb, M. J. The dependence of radiative forcing and feedback on evolving patterns of surface temperature change in climate models. J. Clim. 28, 1630–1648 (2015).

Rugenstein, M. A., Caldeira, K. & Knutti, R. Dependence of global radiative feedbacks on evolving patterns of surface heat fluxes. Geophys. Res. Lett. 43, 9877–9885 (2016).

Wood, R. & Bretherton, C. S. On the relationship between stratiform low cloud cover and lower-tropospheric stability. J. Clim. 19, 6425–6432 (2006).

Fildier, B. & Collins, W. D. Origins of climate model discrepancies in atmospheric shortwave absorption and global precipitation changes. Geophys. Res. Lett. 42, 8749–8757 (2015).

Gent, P. R. et al. The community climate system model version 4. J. Clim. 24, 4973–4991 (2011).

Neale, R. B. et al. The mean climate of the Community Atmosphere Model (CAM4) in forced SST and fully coupled experiments. J. Clim. 26, 5150–5168 (2013).

Lawrence, D. M. et al. Parameterization improvements and functional and structural advances in version 4 of the Community Land Model. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 3, M03001 (2011).

Smith, R. et al. The Parallel Ocean Program (POP) reference manual Ocean Component of the Community Climate System Model (CCSM) and Community Earth System Model (CESM). Report LAUR-10-01853 (University Corporation for Atmospheric Research, 2010).

Hunke, E. C., & Lipscomb, W. H. CICE: the Los Alamos sea ice model user’s manual, version 4. Tech. Rep. LA-CC-06-012 (Los Alamos National Laboratory, 2008).

Collins, W. D., Lee-Taylor, J. M., Edwards, D. P. & Francis, G. L. Effects of increased near-infrared absorption by water vapor on the climate system. J. Geophys. Res. 111, D18109 (2006).

Wiscombe, W. J. & Evans, J. W. Exponential-sum fitting of radiative transmission functions. J. Comput. Phys. 24, 416–444 (1977).

Marshall, J., & Plumb, R. A. Atmosphere, ocean and climate dynamics: an introductory text, Ch. 9 (Academic Press, 2007).

IOC, SCOR, & IAPSO. The international thermodynamic equation of seawater – 2010: Calculation and use of thermodynamic properties (Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission, 2010).

Soden, B. J. & Held, I. M. An assessment of climate feedbacks in coupled ocean–atmosphere models. J. Clim. 19, 3354–3360 (2006).

Taylor, K. E. et al. Estimating shortwave radiative forcing and response in climate models. J. Clim. 20, 2530–2543 (2007).

Pendergrass, A. G., Conley, A. & Vitt, F. M. Surface and top-of-atmosphere radiative feedback kernels for CESM-CAM5. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 10, 317–324 (2018).

Soden, B. J. et al. Quantifying climate feedbacks using radiative kernels. J. Clim. 21, 3504–3520 (2008).

Jia, F. & Wu, L. A study of response of the equatorial Pacific SST to doubled-CO2 forcing in the coupled CAM–1.5-layer reduced-gravity ocean model. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 43, 1288–1300 (2013).

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge two anonymous reviewers whose valuable comments led to significant improvements to the manuscript. We are deeply grateful to Masahiro Watanabe, Robert Pincus, Aixue Hu, Wei Liu, Elizabeth Maroon, Doyeon Kim, and Yechul Shin for helpful discussions on early stage of the work.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.K. and H.K. designed the project. Model experiments are performed by H.K. and D.L., and data were analyzed by all authors. S.K. and D.L. contributed during the writing of the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, D., Kim, H. & Kang, S.M. Enhanced shortwave absorption by water vapor increases effective climate sensitivity via accelerated AMOC recovery. npj Clim Atmos Sci 8, 283 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-01169-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-01169-8