Abstract

Urban aerosol pollution is evolving rapidly with global change and poses significant risks to public health. Measurements and machine learning-enabled chemical analysis of aerosol from a suburb of New York City in 2023 reveal emerging sources and drivers in a modern megacity. Regional wildfire smoke averaged 25% of organic aerosol (OA) mass and drove variability via enhancements of biogenic OA formation within smoke plumes. This biogenic OA contributed 40% of aerosol mass. Urban heatwaves enhanced both biogenic and anthropogenic sources, with ~20% of OA mass exhibiting significant heatwave sensitivity. For the first time, volatile chemical product (VCP) compounds were directly observed, speciated, and characterized in urban aerosol. Contributions to total OA averaged 15%, double the contribution from traffic. Together, this work identifies wildfire smoke, biogenic emissions, heat, and emerging anthropogenic emissions as critical global change vulnerabilities for North American urban aerosol pollution that pose unique challenges for control strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Urban aerosol pollution drives excess morbidity and mortality globally, with elevated exposure associated with ailments including heart disease, lung cancer, and dementia1,2. Health impacts from exposure to PM2.5 (fine aerosol material less than 2.5 µm in diameter) occur at levels below current regulatory guidelines3. As regulations, engineering controls, human activity patterns, and background regional dynamics evolve, so too do the relative importance of different source classes to urban air pollution formation and fate. This dynamic has demonstrably occurred in North America, where legislation and engineering controls have significantly curbed traditionally considered anthropogenic sources of urban PM2.5 from industry and traffic over the past century4,5. Recent studies have identified that these decreases are so significant that nontraditional anthropogenic pollution sources, such as volatile chemical products (VCPs) including solvents, coatings, and consumer products, may now be more important contributors to aerosol pollution than traditionally considered industrial and mobile sources combined6,7. Evolving sources require evolving strategies for control; understanding current and future anthropogenic sources of urban particulate pollution is critical for informing interventions to improve public health.

As human emissions have changed, so too have climate conditions, impacting both local and global air pollution. Wildfires have increased in both frequency and magnitude8,9, potentially tripling summer PM2.5 in the Western USA over the coming century10 and degrading air quality across the country11. This was particularly evident in the summer of 2023, when massive, climate change-driven fires across multiple expanses of Canadian forests impacted air quality across North America12,13,14,15. This smoke influence challenges traditional source apportionment techniques for aerosol16. Climate change also impacts biogenic volatile organic compound (BVOC) emissions and the resulting secondary aerosol material (biogenic secondary organic aerosol; BSOA). BVOC emissions are temperature sensitive, increasing significantly during heat waves17,18, and are also subject to indirect climate effects such as insect infestations19. Temperature-dependent VOC sources are now thought to dominate aerosol concentrations in Los Angeles20, with organic aerosol in multiple cities showing sensitivity to summer temperatures21,22. Oxidants, aerosol precursors, and aerosol seed availability work together to impact secondary organic aerosol formation23, meaning that global change may impact PM2.5 mass and composition in complex ways that are challenging to predict.

Observational source apportionment of emerging anthropogenic and climate change-associated sources of urban air pollution has thus far been held back by the complexities within and similarities between sources. Aged wildfire smoke haze from far-distant fires becomes almost indistinguishable from generalized oxidized organic aerosol16. Volatile chemical products are incompletely characterized, incredibly chemically complex, and share secondary organic aerosol precursor emissions, such as monoterpenes, with biogenic sources7,24,25,26. In this work, a unique combination of molecular-level speciated and bulk aerosol composition analysis techniques is leveraged in concert with complementary gas-phase measurements and airmass history analyses to embrace these challenges in a novel source and sensitivity apportionment approach.

We present a quantitative analysis of fine aerosol sources in a residential suburban region downwind of New York City in the summer of 2023 – allowing us to disentangle factors controlling this emerging regime of megacity aerosol pollution. This urban aerosol is sensitive to climate change via multiple mechanisms and is thereby vulnerable to increase, which will impact public health. Our work estimates and quantifies these sensitivities, identifying transported wildfire smoke and temperature-dependent emissions of both biogenic and anthropogenic aerosol precursors as key contributors to aerosol pollution in the modern megacity.

Results

Aerosol mass dynamics and bulk attribution

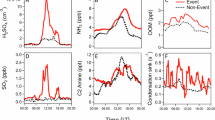

The Fluxes of Reactive Organic Gases over New York (FROG-NY) campaign took place during the summer of 2023 in Mineola, NY, on Long Island. Submicron aerosol (PM1) ranged from 1.0 to 39.3 (average and standard deviation: 9.9 ± 5.5) µg/m3. PM1 rarely (<20% of the time) dropped below the WHO fine aerosol guideline of 5 µg/m3, and was predominantly organic (average 86%), with less sulfate (9%), nitrate (3%), and ammonium (2%). These findings are similar to summer 2022 results from nearby Queens, NY (80% organic, 10% sulfate, 5% nitrate, and 5% ammonium)21. Three periods of sustained elevated PM occurred in summer 2023 (Fig. 1A): two coincided with wildfire smoke (July 19–21, August 5–7) and the third with a regional heat index advisory (July 27-29). The latter involved a mean heat index of 31°C and daily maxima of 37–41°C, compared to a mean heat index of 26 °C and no consecutive days with maximum heat indices > 36 °C during the rest of the project.

A Concentrations and bulk composition of submicron aerosol observed in Mineola, NY during summer 2023. Pie charts illustrate the average distribution of aerosol mass between the inorganic-containing and factorized organic components. Orange shading denotes periods of significant long-range wildfire influence. Red shading denotes the heat advisory period. B-E Average carbon oxidation state vs carbon number for speciated aerosol compound measurements colored by source attribution. B All consistently observed compounds; central markers and error bars indicate unweighted average and standard deviations of each source cluster property space. Inset pie charts describe number distributions of all consistently observed compounds by source cluster (L); the smaller pie chart (R) summarizes the number distribution of VCP classes. C–E Speciation, source attribution, and relative mass (size) of speciated aerosol marker observations during focus periods. Inset pie charts indicate the average bulk PMF factor contributions coinciding with the speciated measurement collection period. Eleven compounds, including siloxanes, are excluded due to heteroatoms that are poorly represented in this parameter space.

Organic aerosol (OA) was attributed to six chemically and temporally distinct bulk factors (Figs. 1; S1; Table 1; Section SI.3). Three of these factors can be directly tied to specific sources: hydrocarbon OA from vehicle emissions (HOA; average 5.8% of OA), aged biomass burning OA from Canadian wildfires (Aged BBOA; 25.5%), and Cooking OA predominantly from restaurants (8.7%). Consistent with previous work16, Aged BBOA was more chemically similar to typically Oxidized Organic Aerosol (OOA) than to fresh BBOA, and its attribution was thus based on mass spectral features (Fig. S2) and correlation with gas- and aerosol tracers (Table S1, Figs. S3 and S4). This factor was also temporally and chemically similar to the Med Ox OOA factor (described below), and its separation therefore required validation by aerosol-phase molecular tracers and in-depth comparisons to gas-phase tracers (SI.3.1). Simultaneous measurements at a nearby rural site rule out local biomass burning sources and potential artifacts in gas-phase biomass burning tracers27, and confirm that wildfire smoke influence was both ubiquitous and atypical in 2023. For example, median acetonitrile concentrations were twice as high in 2023 compared to 2022 (SI Section SI.4, Fig. S5).

The remaining three oxidized organic aerosol (OOA) factors were not attributable to distinct sources, but instead reflect regional SOA formed under various atmospheric conditions: less oxidized OA (Less Ox OOA; 7.2% of OA), moderately oxidized OA (Med Ox OOA; 34.7%), and highly oxidized OA (High Ox OOA 18.1%). While most urban studies report total organic mass to organic carbon mass ratios (OM/OC) < 2, with 1.6 a typical value28,29,30, the High Ox OOA at FROG-NY had an average O/C of 1.2 ± 0.1, contributing to an overall bulk OM/OC of 2.7 ± 0.2. A tracer-based source attribution approach identifies the OOA material as predominantly biogenic SOA with a moderate contribution from VCPs (SI.3).

Volatile Chemical product observations and dynamics in urban aerosol

Off-line aerosol filter analysis identified 909 unique organic compounds, 404 of which were consistently observed (i.e., present above detection limit in >30% of samples) and had diverse molecular properties (Fig. 1B–D). These 404 compounds were attributed (SI.1.3, Figs. S6 and S7) to the following source groups based on statistically optimized patterns of shared time varying behavior and literature review of identifiable tracer species within each group: biogenic secondary organic aerosol (21% of compounds), biomass burning (15%), cooking (0.5%), hydrocarbons and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs, 13%), and VCPs (40%). An additional 10% of the compounds were not attributed to a major source group. For compounds that could not be identified through mass spectral matches to the NIST 2020 mass spectral database or comparison to authentic standards, the Ch3MS-RF model was used to estimate their molecular properties31. Structural characterization and literature review of the 106 identifiable VCPs (Table S2) revealed the following sources or use classes: (i) glycols and glycol ethers (e.g., diethylene glycol monobutyl ether - DEG MbE, tripropylene glycol monomethyl ether - TPM, propylene glycol methyl ether acetate - PGMEA, butylene glycol); (ii) fragrances (e.g., hedione, galaxolide); (iii) phthalates (e.g., diethyl phthalate - DEP, dimethyl phthalate - DMP); (iv) siloxanes (e.g., Cyclomethicone-7, tetradecamethyl-hexasiloxane - hereafter abbreviated Siloxane*); (v) pesticides including diethyltoluamide (DEET); and (vi) plasticizers (e.g., 2,2,4- trimethyl-1,3-pentanediol diisobutyrate - TXIB).

During the heatwave (Fig. 1C), both the Less Ox OOA factor and biogenic SOA tracers become prominent. Key among these tracers are 2-methyl tetrol, 2-methylglyceric acid, and C5-alkene triol (Fig. S6 and S9), all of which are indicators of isoprene oxidation chemistry. In contrast, oxidation products from biogenic monoterpenes such as MBTCA (methyl-butyl-tricarboxylic acid32 were not detectable, despite the high sensitivity of the measurement technique33. While twelve of the consistently observed compounds have been detected in monoterpene chamber oxidation experiments, molecular structures have only been identified for a few of these compounds, and none are well-characterized biogenic SOA tracers. Two consistently observed VCP-grouped compounds include monoterpene SOA products, including pinonaldehyde; these compounds were not correlated with the biogenic SOA tracer group (r = 0.09). These results point to the potential impacts from both biogenic and anthropogenic monoterpenes on urban aerosol, but further studies are required to confidently apportion biogenic vs anthropogenic monoterpene SOA in the Northeast US.

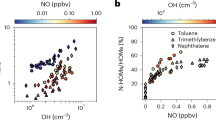

Wildfire events (Fig. 1D) coincided with increased concentrations of speciated biomass burning tracers. These tracers were dominated by sugars (levoglucosan, arabinofuranose, and D-erythronolactone), plus furans, acids, and monoterpene oxidation products (Figure S4). Sugars were more prominent during the second burning period, consistent with slightly less aged smoke. During the least smoke-influenced “background” periods (Fig. 1E), VCP species were particularly prominent. In contrast to the biogenic and biomass burning sources, VCPs did not exhibit a coherent temporal pattern (SI.5, Fig. S7). However, some VCPs correlate with airmass and meteorological variables (Table S3), pointing to mechanistic drivers behind their concentrations in the aerosol phase (Fig. 2). While concentrations for most observed compounds do not vary with relative humidity (averaged over the 6-hour airmass history for each filter sample), a subset of glycols and glycol ethers are strongly anticorrelated with airmass humidity. This relationship is stronger than their correlation with airmass temperature, and may be driven by humidity-dependent evaporation/partitioning of these species in dry airmasses34, or because they are typically used in aqueous mixtures that evaporate more rapidly under dry conditions. Other VCPs exhibit statistically significant (p < 0.05) anticorrelations with site windspeed (Fig. 2). This relationship is consistent with local VCP sources accumulating as air masses move slowly over the densely populated community around the site. Figure 2 provides additional evidence for this population source of VCPs; most such compounds correlate well with airmass population density (Table S3). This finding corroborates previously observed correlations between gas-phase VCPs and population density25 and provides direct evidence that population-dependent emissions contribute to secondary aerosol in urban regions6. However, we find here that none of the bulk aerosol mass features were sensitive to upwind population density. This indicates that VCP contributions to aerosol mass may have more moderate effects on downwind aerosol mass than previously predicted, possibly implying a relatively local sphere of influence.

Wildfires and cooking emissions drove mass variability

Although Aged BBOA and Cooking OA accounted for, on average, <35% of submicron aerosol, their dynamics drove variability in PM1 – even during periods of relatively low BBOA influence. Biomass burning was more strongly correlated (r = 0.86) with PM1 than was any other factor (Fig. 3). Speciated biogenic SOA tracers were also well correlated (r = 0.7) with speciated biomass burning tracers (Fig. S8). We find that biomass burning sets a remarkably consistent baseline for total aerosol mass, with total mass consistently greater than 3.2 × Aged BBOA. No other source group shows this behavior. While acknowledging the potential artifacts of PMF bulk aerosol analysis (SI.1.2) and external covariates that can impact all aerosol source groups (such as precipitation and number of hours spent over land), the observations nevertheless suggest that biomass burning aerosol influences aerosol mass from other source groups.

Speciated tracer dynamics indicate that Biogenic SOA contributes substantially to the Med Ox and High Ox OOA factors, the two factors most consistently covarying with burning influence (r = 0.88 and 0.77 with Aged BBOA, respectively) – meaning that biomass burning aerosol is associated with enhanced Biogenic SOA (Fig. S8 and S9, SI.3.2). This could in theory result from geographically shared emissions regions. However, the dominance of isoprene oxidation tracer species within the Biogenic SOA tracer population and geographical emissions patterns render this unlikely. The regions of Canada where the smoke originated are dominantly monoterpene-producing, with very low isoprene emissions13,35. Isoprene emissions become more significant within a relatively small regional radius of New York, and are particularly important emissions of urban tree cover in the New York City region35,36. Meteorology could also contribute to shared variability from regional sources; however, this effect is not supported by a partial correlation analysis of Biogenic SOA and Biomass Burning tracers controlling for airmass history windspeed, and rainfall, the two meteorological parameters that are most strongly associated with the shared Biogenic SOA Biomass Burning tracer variability pattern. The partial correlation remains >0.7, with a p ≪0.0001. Random co-occurrence may occur, but is unlikely given the high statistical significance and strength of the partial correlation controlling for meteorological covariance. Given these lines of evidence, we hypothesize that the covariance between Biogenic SOA and Biomass Burning OA is at least partially due to a mechanistic relationship between the two variables. Previous studies have shown that urban plumes increase biogenic SOA formation23,35,36; here, we find possible evidence for similar effect from smoke plumes rather than urban plumes. Two mechanisms could explain this observation: (i) transported smoke increases the condensational sink and thereby promotes particle-phase partitioning, and (ii) smoke brings oxidants and nitrogen oxides into the region and enhances SOA production. Both mechanisms rely on bringing smoke into a VOC-rich airmass, which is clearly present from biogenic and anthropogenic precursors in the New York region. Although smoke plumes have been previously characterized as oxidant-depleted due to their highly reactive VOC mixture37, the extreme ageing of the smoke plumes experienced by the New York region in summer 2023 may have shifted these dynamics. Wildland fires are established sources of peroxyacetyl nitrate, which decomposes to produce NOx upon descent into warmer environments38; NOx could potentially contribute to higher aerosol yields. NOx concentrations observed during FROG-NY do correlate moderately, but significantly, with biomass burning aerosol over 12-hour averaging periods (r = 0.54, p < 0.005). However, we hypothesize that the increased biogenic SOA is more likely due to heightened aerosol surface area and aerosol mass within smoke plumes, given the strong sensitivity of secondary organic aerosol formation yields to organic aerosol mass concentration due to equilibrium partitioning dynamics39,40. Thus, much like urban plumes in a biogenic VOC-rich environment, biomass burning may also accelerate biogenic SOA formation.

Whereas biomass burning sets baseline PM levels, cooking OA drove significant deviations above this baseline (Fig. 3). While cooking contributed little to average OA ( < 10%), sporadic extremes meant that it was important at particular times: accounting for >30% of OA mass 3% of the time, with a maximum contribution of 53% OA. Cooking aerosol may thus be a small contributor to average urban aerosol, but due to its strong spatial and temporal heterogeneity it can produce hyper-local PM hotspots and be a potential source of acute aerosol exposure within communities.

Sensitivity of aerosol mass to temperature, oxidants, and airmass history

While wildfire smoke and cooking dominated submicron organic aerosol mass dynamics, other meteorological and environmental variables also played important roles. We assessed the sensitivity of each bulk aerosol source factor to atmospheric and airmass parameters using a multivariate linear regression analysis – acknowledging that this analysis reveals correlations with drivers that are not necessarily causal relationships (SI.3). First, we investigated how well the variance in PM1 was described by six potential predictors: population density (6-hour airmass back trajectory, people/mi2), rainfall (24-hour airmass back trajectory, mm/hr), windspeed (12-hour airmass back trajectory, m/s), vegetation (12-hour airmass back trajectory normalized difference vegetation index or NDVI, unitless), site temperature (°C), and site ozone (ppb) (results in Fig. S10). HOA, Med Ox OA, and Less Ox OA were all significantly enhanced with increased temperatures. HOA and all three OOA factors were significantly associated with back trajectory population densities. However, this population density effect is small, constituting a maximum effect of 2.6 µg/m3 when summed across all four factors and scaled by the range of observed airmass histories (Table S5). HOA mass dynamics are generally explained by the combined effects of temperature and NO2 (as a proxy for traffic influence; SI.3.4), with temperature accounting for 35% of the observed HOA variability (Fig. S11). After accounting for indirect biomass burning effects based on the Aged BBOA factor (Fig. S9A–C), we find that High Ox OOA increases with ozone, while Med Ox OOA and Less Ox OOA do not. Overall, elevated temperatures explain 29% of summed OOA mass variability, while biomass burning explains 62%. Despite clear population effects for a subset of individual VCP tracers (Table S3), population density was only a minor (<4%) – albeit statistically significant – driver of Less Ox OOA and Med Ox OOA (Fig. S9). These observations suggest that the chemical diversity of VCPs prevents the formation of a single bulk VCP factor and thus hinders traditional bulk source apportionment techniques (SI.5). That said, while gas-phase observations have suggested that VCPs are important contributors to urban air pollution25 and we see evidence for consistent local contributions, we do not observe evidence for a substantial VCP role in downwind urban SOA.

Biogenic versus VCP contributions to SOA

To quantify the relative contribution of biogenic versus VCP precursors to urban OA at the FROG-NY site, we employ a linear modeling approach using speciated tracer clusters (or in the case of Less Ox OA, the single isoprene oxidation tracer C5 alkene triol) as predictors of OOA mass (Fig. S9D–F). The dynamics of OOA mass are remarkably well represented by a combination of VCPs and biogenic SOA. On average, the VCPs contribute a relatively consistent background, while biogenic SOA contributes to OOA mass variability. This analysis suggests that, on average, 11% of the observed OA comes from VCPs and 40% from biogenic sources. These results, quantifying direct sources from bulk analysis and the unresolved Ox OA sources from tracer-based source apportionment, are illustrated in Fig. 4. As the bulk speciation residuals are consistently low (Fig. S17D), the discrepancy between total observed and source-estimated organic aerosol is primarily attributable to either anomalously high or low fractional contributions of tracer species to underlying source groups or to underlying variability from an Ox OA source not accounted for in this analysis. We compare this analysis to a separate cluster tracer approach using only speciated clusters as predictors of all organic mass (Figs. S12, SI.3.6), which finds that biogenic sources contribute on average 45%, VCPs 18%, cooking 13%, and biomass burning 12% of total OA. The two methods agree across all sectors except hydrocarbon organic aerosol, which was not well represented by available speciated tracers, and biomass burning (12% from the speciated method, 25% from the bulk method). This is likely due to significant aging of the transported wildfire smoke, which lowers the proportion of sugars in the July event – and would cause a biomass burning underestimate when using the tracer-based approach. In all, we find that biogenic SOA contributed ~40% of observed aerosol mass, while VCPs contributed ~15%, during summer 2023 in Mineola, NY (Fig. 5, SI.3).

Aged biomass burning, cooking, and hydrocarbon OA estimates are based on PMF analysis, while biogenic OOA and VCP OOA estimates are based on tracer-based source apportionment of the PMF Ox OA factors. The inset pie chart indicates the average contributions of the different source groups. The grey pie sector represents the discrepancy between bulk observed and tracer-based apportioned Ox OA (the prediction residual).

Fractional contributions indicate the average proportions of bulk aerosol organic mass which demonstrated significant sensitivities to continental biomass burning dynamics (orange), biogenic secondary organic aerosol formation dynamics (green), VCPs (pink) and urban temperatures (red). Maroon indicates the fraction of aerosol mass sensitive to a single driver of vulnerability or any combination thereof.

Discussion

Aerosol pollution in the NY region is consistently above the WHO guidelines, with many of the key contributors being sensitive to global change. Although summer 2023 was anomalously influenced by wildfire smoke, wildfires are increasingly affecting urban regions around the world that historically have not been significantly impacted by smoke, including New York. At the same time, increased temperatures enhance biogenic and evaporative anthropogenic emissions of aerosol precursors. Increasing population density and industrial activity will likely increase VCP emissions further. Together, we find that approximately 90% of aerosol mass in summer 2023 was sensitive to at least one aspect of global change (SI.3.7): ~60% of aerosol mass was sensitive to biomass burning, ~20% was sensitive to heat, ~40% was sensitive to biogenic emissions, and ~15% could be attributed to VCPs (Fig. 5). This VCP influence represents more than double the estimated contribution from mobile anthropogenic sources. Traffic and cooking aerosols are only minor components of the total average aerosol load, but have substantial spatial heterogeneity and thereby contribute to environmental health inequality. While regulatory controls of vehicle emissions have been successful, other sources of particulate pollution are becoming increasingly serious threats to public health. The emerging challenge for air quality in the modern megacity is that improvements will require addressing both point sources, such as commercial cooking operations that impact local communities, along with the underlying drivers of global change that enhance wildfires and heat waves.

Methods

Site and sampling design

FROG-NY involved continuous VOC, aerosol, and oxidant measurements in Mineola on Long Island from 9 July – 14 August 2023. A site map with local sources annotated is illustrated in Fig. S14. The site was in a mixed-use commercial and residential region, and occasionally downwind of New York City. Heated Teflon VOC inlets were 32.5 m a.g.l. (above ground level); aerosol and oxidant inlets (copper and Teflon, respectively) were 4 m a.g.l.

Aerosol, VOC, oxidant, and meteorology measurements

Two online instruments measured VOCs at the tower site: a Proton Transfer Reaction-Time of Flight Mass Spectrometer (PTR-QiTOF, Ionicon Analytik) measured alkenes and OVOCs, while an Iodide Chemical Ionization Mass Spectrometer (Aerodyne Research, Inc.) measured highly oxygenated and halogenated species. Measurement details for these two instruments are described in Vermeuel et al.41. Complementary measurements of VOCs were conducted at Flax Pond Marine Laboratory from 24 June-31 August 2022 and 1 June – 19 August 2023, (PTR-ToF-MS 8000, measurements described in Coggon et al.42). A Time-of-Flight Aerosol Chemical Speciation Monitor (Aerodyne Research, Inc43.) measured bulk aerosol composition, enabling a Positive Matrix Factorization (PMF44) analysis of the organic fraction for source attribution and characterization. Relevant properties of the organic PMF factors including O:C, H:C, and average carbon oxidation state were approximated following established methods45. ACSM calibration and PMF optimization results are illustrated in Fig. S16, with supplementary discussion in SI.1 and SI.2. A Scanning Mobility Particle Sizer (TSI, Electrostatic Classifier 3082, DMA 3083, and CPC 3750) measured aerosol size distribution between 13.3 and 723.4 nm, which was converted to mass concentration based on composition as indicated by the ACSM by established methods46,47. A comparison of aerosol mass concentration as measured by ACSM, SMPS, and filter-based analyses is illustrated in Fig. S15. Submicron aerosol filters were collected over 12-hour intervals with changeovers occurring daily at 6:00 and 18:00 local time, except for five intensives during which filters were collected in 4-hour increments. These filters were immediately frozen and, within 30 days of campaign conclusion, analyzed for speciated organic composition using two techniques. The first technique, Thermal Desorption Two-Dimensional Gas Chromatography coupled with High Resolution Time-of-Flight Mass Spectrometer (TD-GCxGC-HR-ToF-MS), provides isomer-specific separation and characterization of analytes in a volatility range of C14 to C36 n-alkane equivalents. This technique separated and traced 909 unique aerosol-phase species and employs online derivatization to enable characterization of oxidized organics, with a strong previous methodological emphasis on biogenic secondary organic aerosol tracers33. Column and analysis details and filter collection specifics are identical to those described in Franklin et al. 48. GCxGC data were analyzed in GC image™. A subset of filter samples were also analyzed offline by Filter Inlet for Gases and AEROsols Chemical Ionization Mass Spec (FIGAERO-I-CIMS)49. The offline FIGAERO analytical protocol included a 35-minute temperature ramp from 25 °C to 200 °C followed by a 290-minute desorption cycle at the maximum temperature setting. All filters were also analyzed for organic carbon and elemental carbon concentrations50. NOx measurements were made via a trace level analyzer with 1 minute resolution (Thermo Fisher Scientific 42i-TL). Ozone measurements were made with a 2B-Tech 202 O3 monitor calibrated in the field. Local meteorological data was collected by an Ambient Weather WE-2902 Home Wifi Weather installed above and adjacent to the aerosol inlets.

Tracer analysis and machine learning-based modeling

The library of traced compounds from the GCxGC analysis was sourced from 10 template samples representing a wide range of conditions, with an additional 21 compounds added based on repeated identification in non-template samples. Quantification methods for GCxGC, including for unidentifiable compounds, are described in Franklin et al.31. The library of traced compounds was compared to the NIST 2021 mass spectral database, custom libraries of compounds observed at other field sites33,51, and samples generated by oxidation of single precursor monoterpene and isoprene oxidation experiments, as described in Franklin et al. 2023 and Chen et al. 52,53. These combined methods were used to identify and categorize species to the extent possible. In addition to mass spectral characterization, compounds were grouped into statistically optimized clusters of similar temporal variability via dynamic time warping hierarchical clustering. Resulting time series profiles were labeled as biogenic, biomass burning, cooking, hydrocarbon/PAH, or VCP based on the presence of well-characterized tracers. This method has been described in detail in Franklin et al. 2022 and 202352,54. In cases of a similar match to multiple clusters and identifiable species, cluster assignment was additionally informed by literature review and chemical similarity to tracer species. Key tracers were levoglucosan for biomass burning, 2-methyl tetrols for biogenic species, palmitic acid for cooking, and siloxanes, fragrances, phthalates, and plasticizers for VCPs. Compounds that did not demonstrate a Pearson correlation coefficient >0.4 with any of the cluster profiles, and that could not be unambiguously assigned to a cluster grouping based on identity, were defined as ‘unclustered’. For unidentifiable compounds, properties including carbon number, average carbon oxidation state, O:C, and H:C were predicted using the Ch3MS-RF model31. The tracer clustering optimization analysis results are detailed in SI.1.3.

Airmass history characteristic analysis

The NOAA Hysplit model51, initialized at 50 meters agl with GDAS-1 meteorology, provided hourly 48-hour airmass back trajectories for the site (Fig. S20). At each hour, the latitude, longitude, and meteorological metadata generated by HYSPLIT were cross-referenced with 2022 US county-based census population density estimates and satellite-based observations of normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI) to generate airmass histories that reflected the meteorological history of the airmass and approximated its exposure to vegetation and human activity. These airmass histories were then trimmed to the 6-,12-, 24-, or 48-hours preceding arrival at the site and averaged to produce average airmass histories. An example full day of 48-hour trajectories are illustrated in Fig. S20. NDVI was sourced from the VIIRS satellite, accessed from the midpoint of the campaign (31 July 2023), and is illustrated in Fig. S2155.

Source contribution and source sensitivity analysis

Multivariate linear modeling estimated the relative contributions of various environmental predictors and potential source groups according to the following equation:

Ci denotes hourly average mass concentration of aerosol bulk source factor or total organic mass i in µg/m3, Xn the predictor variables, βn, i the regression coefficients, and εi the error (i.e., difference between true and modeled abundance of factor Ci). Tracer abundances are summed from internal standard-normalized peak areas, a quasi-quantitative metric inclusive of unquantifiable species (see Tracer Analysis and Machine Learning above). Although many of the meteorological and airmass history effects explored within this work are nonlinear, this analysis provides a conservative approach for interpolative attribution. More realistic representations of effects, such as exponential sensitivities to temperature, overfit the available data, likely leading to overestimates of correlations. Predictors included meteorological conditions and average population densities along the airmass back trajectories, and site characteristics such as temperature and oxidant concentrations. Speciated tracers attributed to biomass burning, biogenic SOA, VCP, hydrocarbon-like organic aerosol, and cooking are summed across each group and used as predictors of organic aerosol mass. Assuming that these species are relatively consistent tracers of their source classes and broadly representative of the variability of co-emitted or produced compounds to which the speciated technique is not sensitive, this method yields a tracer-based source apportionment for estimating aerosol mass. The validity of this assumption is supported by the broad agreement between the entirely tracer-based source apportionment analysis of total organic aerosol mass and PMF analysis. The models upon which our findings herein are based include fifteen unique models of total OA mass or bulk OA factor mass as estimated by PMF. These models are broken into six categories, as follows: Model SM1, PMF factors vs meteorology and airmass history; Model SM2: OOA factors vs Aged BBOA and Airmass History Characteristics, Model SM3: OOA factors vs Selected Grouped Speciated Aerosol Tracers, Model SM4: Hydrocarbon OA vs Expanded Site Characteristics, Model SM5: Total Organic Aerosol vs Acetonitrile and Airmass History Characteristics, Model SM6: Total Organic Aerosol vs Grouped Speciated Aerosol Tracers. These analyses, including combined PMF- multivariate approaches to estimate biogenic and VCP contributions to total organic aerosol and global change vulnerabilities, are summarized in Table S4, with supplementary results discussed in details in SI.3.

Data availability

All data needed to evaluate the conclusions of this paper are present in the paper, the Supplementary Materials, or publicly accessible databases. Aerosol bulk composition, trace gas, local meteorology, and aerosol size distribution measurements are available through the NOAA CSL Database (https://csl.noaa.gov/groups/csl7/measurements/2023aeromma/frogny/DataDownload/). GCxGC mass spectra, variability, and associated metadata are available at https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.xpnvx0krd.

References

Cohen, A. J. et al. Estimates and 25-year trends of the global burden of disease attributable to ambient air pollution: an analysis of data from the Global Burden of Diseases Study 2015. Lancet 389, 1907–1918 (2017).

J. Li. et al. Long-term effects of PM 2.5 components on incident dementia in the northeastern United States. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xinn.2022.100208 (2022).

Di, Q. et al. Air pollution and mortality in the medicare population. N. Engl. J. Med. 376, 2513–2522 (2017).

McDonald, B. C., Gentner, D. R., Goldstein, A. H. & Harley, R. A. Long-term trends in motor vehicle emissions in U.S. urban areas. Environ. Sci. Technol. 47, 10022–10031 (2013).

Krupnick, A. J. & Portney, P. R. Controlling urban air pollution: A benefit-cost assessment. Science (1979) 252, 522–528 (1991).

McDonald, B. C. et al. Volatile chemical products emerging as largest petrochemical source of urban organic emissions. Science (1979) 359, 760–764 (2018).

Pennington, E. A. et al. Modeling secondary organic aerosol formation from volatile chemical products. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 21, 18247–18261 (2021).

Westerling, A. L., Hidalgo, H. G., Cayan, D. R. & Swetnam, T. W. Warming and earlier spring increase Western U.S. forest wildfire activity. Science (1979) 313, 940–943 (2006).

Marlon, J. R. et al. Long-term perspective on wildfires in the western USA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109, E535–E543 (2012).

Xie, Y. et al. Tripling of western US particulate pollution from wildfires in a warming climate. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2111372119 (2022).

Lee, H. & Jaffe, D. A. Wildfire impacts on O3 in the Continental United States Using PM2.5 and a Generalized Additive Model (2018-2023). Environ. Sci. Technol. 58, 14764–14774 (2024).

Kirchmeier-Young, M. C. et al. Human driven climate change increased the likelihood of the 2023 record area burned in Canada. NPJ Clim. Atmos. Sci. 7, 1–12 (2024).

Jain, P. et al. Drivers and impacts of the record-breaking 2023 wildfire season in Canada. Nat. Commun. 15, 1–14 (2024).

Yu, M., Zhang, S., Ning, H., Li, Z. & Zhang, K. Assessing the 2023 Canadian wildfire smoke impact in Northeastern US: Air quality, exposure and environmental justice. Sci. Total Environ. 926, 171853 (2024).

Hu, Y., Yue, X. & Tian, C. Climatic drivers of the Canadian wildfire episode in 2023. Atmos. Ocean. Sci. Lett. 17, 100483 (2024).

T. Joo. et al. Aged and Obscured Wildfire Smoke Associated with Downwind Health Risks. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. https://doi.org/10.1021/ACS.ESTLETT.4C00785 (2024).

Churkina, G. et al. Effect of VOC emissions from vegetation on air quality in Berlin during a heatwave. Environ. Sci. Technol. 51, 6120–6130 (2017).

Guenther, A. B., Zimmerman, P. R., Harley, P. C., Monson, R. K. & Fall, R. Isoprene and monoterpene emission rate variability: Model evaluations and sensitivity analyses. J. Geophys. Res.: Atmos. 98, 12609–12617 (1993).

Joutsensaari, J. et al. Biotic stress accelerates formation of climate-relevant aerosols in boreal forests. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 15, 12139–12157 (2015).

Pfannerstill, E. Y. et al. Temperature-dependent emissions dominate aerosol and ozone formation in Los Angeles. Science (1979) 384, 1324–1329 (2024).

Hass-Mitchell, T. et al. Increasing contributions of temperature-dependent oxygenated organic aerosol to summertime particulate matter in New York City. ACS EST Air 1, 113–128 (2024).

Nussbaumer, C. M. & Cohen, R. C. Impact of OA on the temperature dependence of PM 2.5 in the Los Angeles basin. Environ. Sci. Technol. 55, 3549–3558 (2021).

Shrivastava, M. et al. Urban pollution greatly enhances formation of natural aerosols over the Amazon rainforest. Nat. Commun. 2019 10:1 10, 1–12 (2019).

Jo, O., Han, J. Q., Askari, A., Abbatt, J. P. D. & Chan, A. W. H. Investigation of anthropogenic monoterpenes in Canadian Cities. ACS Earth Space Chem. 7, 2252–2262 (2023).

Gkatzelis, G. I. et al. Identifying volatile chemical product tracer compounds in U.S. cities. Environ. Sci. Technol. 55, 188–199 (2021).

Nematollahi, N., Kolev, S. D. & Steinemann, A. Volatile chemical emissions from 134 common consumer products. Air Qual. Atmos. Health 12, 1259–1265 (2019).

Huangfu, Y. et al. Revisiting Acetonitrile as tracer of biomass burning in anthropogenic-influenced environments. Geophys Res Lett. 48, e2020GL092322 (2021).

He, L.-Y. et al. Submicron aerosol analysis and organic source apportionment in an urban atmosphere in Pearl River Delta of China using high-resolution aerosol mass spectrometry. J. Geophys. Res.: Atmos. 116, 12304 (2011).

Bae, M., Schauer, J. & J. T.-A. S. and Technology, undefined 2006 Estimation of the monthly average ratios of organic mass to organic carbon for fine particulate matter at an urban site. Taylor Francis 40, 1123–1139 (2006).

Sun, Y.-L. et al. Characterization of the sources and processes of organic and inorganic aerosols in New York city with a high-resolution time-of-flight aerosol mass apectrometer. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 11, 1581–1602 (2011).

Franklin, E. B. et al. Ch3MS-RF: A random forest model for chemical characterization and improved quantification of unidentified atmospheric organics detected by chromatography-mass spectrometry techniques. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 15, 3779–3803 (2022).

De Sá, S. S. et al. Urban influence on the concentration and composition of submicron particulate matter in central Amazonia. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 18, 12185–12206 (2018).

Zhang, H. et al. Monoterpenes are the largest source of summertime organic aerosol in the southeastern United States. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 115, 2038–2043 (2018).

Pankow, J. F., Storey, J. M. E. & Yamasaki, H. Effects of relative humidity on gas/particie partitioning of semivolatile organic compounds to urban particulate matter. Environ. Sci. Technol. 27, 2220–2226 (1993).

Zheng, Y. et al. Anthropogenic amplification of biogenic secondary organic aerosol production. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 23, 8993–9007 (2023).

Xu, L. et al. Effects of anthropogenic emissions on aerosol formation from isoprene and monoterpenes in the southeastern United States. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 112, 37–42 (2015).

L. Xu. et al. Ozone chemistry in western U.S. wildfire plumes. Sci. Adv. 7 (2021).

Juncosa Calahorrano, J. F. et al. Daytime Oxidized Reactive Nitrogen Partitioning in Western U.S. Wildfire Smoke Plumes. J. Geophys. Res.: Atmos. 126, e2020JD033484 (2021).

Zhang, X. et al. Influence of vapor wall loss in laboratory chambers on yields of secondary organic aerosol. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 111, 5802–5807 (2014).

Jay R. Odum. et al. Gas/particle partitioning and secondary organic aerosol yields. Environ. Sci. Technol. https://doi.org/10.1021/ES950943 (1996).

Vermeuel, M. P. et al. Closing the reactive carbon flux budget: observations from dual mass spectrometers over a coniferous forest. J. Geophys. Res.: Atmos. 128, e2023JD038753 (2023).

Coggon, M. M. et al. Identifying and correcting interferences to PTR-ToF-MS measurements of isoprene and other urban volatile organic compounds. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 17, 801–825 (2024).

Ng, N. L. et al. An Aerosol Chemical Speciation Monitor (ACSM) for routine monitoring of the composition and mass concentrations of ambient aerosol. Aerosol Sci. Technol. 45, 780–794 (2011).

Ulbrich, I. M., Canagaratna, M. R., Zhang, Q., Worsnop, D. R. & Jimenez, J. L. Interpretation of organic components from Positive Matrix Factorization of aerosol mass spectrometric data. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 9, 2891–2918 (2009).

Canagaratna, M. R. et al. Elemental ratio measurements of organic compounds using aerosol mass spectrometry: Characterization, improved calibration, and implications. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 15, 253–272 (2015).

Wu, T. & Boor, B. E. Urban aerosol size distributions: A global perspective. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 21, 8883–8914 (2021).

D. K. Farmer, M. Pothier, J. M. Mattila, Analytical Tools in Indoor Chemistry 32. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-7680-2_35 (2022).

Franklin, E. B. et al. Atmospheric Benzothiazoles in a coastal marine environment. Environ. Sci. Technol. 55, 15705–15714 (2021).

Lopez-Hilfiker, F. D. et al. A novel method for online analysis of gas and particle composition: Description and evaluation of a filter inlet for gases and AEROsols (FIGAERO). Atmos. Meas. Tech. 7, 983–1001 (2014).

Garland, C. et al. Black carbon cookstove emissions: A field assessment of 19 stove/fuel combinations. Atmos. Environ. 169, 140–149 (2017).

A. Goldstein, L. Yee, UCB-GLOBES (Goldstein Library of Biogenic and Environmental Spectra). Available at: https://nature.berkeley.edu/ahg/resources/#site-navigation [Accessed 3 July 2024].

Franklin, E. B. et al. Chemical signatures of seasonally unique anthropogenic influences on organic aerosol composition in the Central Amazon. Environ. Sci. Technol. 57, 6263–6272 (2023).

Chen, Y. et al. Nonequilibrium behavior in isoprene secondary organic aerosol. Environ. Sci. Technol. 57, 14182–14193 (2023).

Franklin, E. B. et al. Anthropogenic and biogenic contributions to the organic composition of coastal submicron sea spray aerosol. Environ. Sci. Technol. 56, 16633–16642 (2022).

Vermote, E. NOAA Climate Data Record (CDR) of VIIRS Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI), Version 1. NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information. https://doi.org/10.25921/gakh-st76 [Accessed 1 February 2024] (2022).

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Katheryn J. Mayer for her support in initiating measurements at the FROG-NY site, Mr. Bill Davies for logistical support, and the Center for Energy Development and Health at Colorado State University for support with OC/EC analysis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: D.K.F., D.B.M., EBF. Methodology: E.B.F., D.K.F., D.B.M., J.E.M., R.C. Investigation: E.B.F., R.K.R., K.R., M.V., T.M., R.O., C.O., A.H.G., J.E.M., J.M., A.D.G., R.C. Data Curation: E.B.F., A.D.G., J.M., M.V. Visualization: E.B.F. Funding acquisition: E.B.F., D.K.F., D.B.M., R.C. Project administration: E.B.F., D.K.F., D.B.M., R.C. Supervision: D.K.F., D.B.M., A.H.G., J.E.M. Resources: D.K.F., D.B.M., E.B.F., R.O., A.H.G., L.D.Y., J.E.M. Writing – original draft: E.B.F. Writing – review & editing: E.B.F., D.K.F., D.B.M., A.H.G., R.K.R., K.R., M.V., R.C., L.D.Y., J.M., A.D.G.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Franklin, E.B., Rossell, R.K., Vermeuel, M.P. et al. Emerging drivers of urban aerosol increase global change vulnerability in a US megacity. npj Clim Atmos Sci 8, 333 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-01202-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-01202-w