Abstract

By modifying precipitation and surface wind patterns, the edges of the tropical hydrological cycle set the boundaries between the dry subtropical and wet temperate zones on Earth. By the end of this century, climate models project a poleward shift of the tropical hydrological cycle edge, which will have large climate impacts in arid and semi-arid regions. Over recent decades, anthropogenic emissions have indeed been found to shift the Southern Hemisphere tropical edge poleward, but their role in the Northern Hemisphere is unclear. Here, using sea-level pressure measurements and atmospheric reanalyses, we constrain the poleward shift of the Northern Hemisphere hydrological cycle edge and show that during autumn it exceeded the bounds of internal variability. The emerged poleward shift is found to likely stem from anthropogenic emissions, specifically over the Pacific and Atlantic basins. The human-induced hydrological cycle changes suggest wider consequences for water availability in boreal subtropical regions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As global temperatures continue to warm, signatures of climate change, which have been predicted by global climate models for decades, are beginning to emerge in the observed climate system. Many of these features are direct consequences of increasing temperature and the associated increase in saturation vapor pressure in the atmosphere, such as increases in heat waves and extreme rainfall events1. However, there is increasing evidence that changes in large-scale atmospheric circulation features, which influence the location and intensity of weather patterns, are also beginning to be detectable in the observational record, despite the large variability in the circulation due to unforced natural climate oscillations2,3,4,5,6,7.

One of the notable circulation changes predicted by climate models in response to increasing greenhouse gases is a poleward shift in the subtropical edges of the tropical hydrological cycle (the Hadley circulation and dry zone edges), which are associated with some of the driest regions on Earth’s surface8. For nearly two decades, scientists have been concerned about this phenomenon and that it might already be occurring in the observational record, potentially at a rate faster than that predicted by global climate models9,10,11,12. However, accurately calculating the Hadley circulation and its trends is challenging using observations. Winds from observation-based reanalysis products can be subject to considerable bias13, particularly in older generation data sets, which likely led to inflated estimates of observed trends documented in earlier literature2,14. Relying on directly observable surface-based quantities, such as sea level pressure (SLP), to define observed Hadley cell trends generally produces more modest trends that are in greater alignment with those predicted by climate models2,5.

In the Southern Hemisphere (SH), a number of recent studies have come to the conclusion that the observed poleward shift in the Hadley cell edge in the late 20th and early 21st centuries is driven at least in part by anthropogenic forcing, and that this forced signal has already emerged from natural variability2,15,16. This is particularly true during summer months, as both stratospheric ozone depletion and increasing greenhouse gases acted to expand the circulation during this season in the late 20th century17,18. However, in the Northern Hemisphere (NH), there is lower confidence in the impact of anthropogenic emissions on the tropical hydrological cycle expansion, since internal variability has obscured the emergence of the annual mean expansion1. Moreover, the forced signal during winter and in the annual mean may not even emerge from internal variability until the end of the 21st century or beyond, even with very large increases in atmospheric greenhouse gas concentrations2,16,19.

It is important to note that most previous studies examining the detection and attribution of observed atmospheric flow trends have focused on the annual mean, or only the winter or summer seasons7. Interestingly, climate model runs forced with increasing greenhouse gases show a much larger poleward shift of the NH Hadley cell edge during the September–November (SON) season (Supplementary Fig. 1), which is of comparable magnitude to that projected for the SH throughout the year20,21. During this season, there is a strong poleward shift of the circulation over both the Atlantic and Pacific sectors, which is much more zonally symmetric compared to other seasons22. The cause of the uniquely large NH trends simulated in response to increasing greenhouse gases during the SON season is not fully understood, but could be related to larger warming in the NH subtropical and mid-latitude oceans21.

In this study, we examine the observed expansion of the NH edge of the tropical hydrological cycle over recent decades and determine whether it is uniquely emerging from internal variability during the SON season due to anthropogenic emissions. Prior studies on this issue have documented large observed trends in the NH Hadley cell edge during the SON season, but often in conjunction with trends of similar magnitude in other seasons23,24. These studies concluded that internal climate variability, and specifically the Pacific Decadal Oscillation, was likely responsible for most of the recent observed NH circulation trends. Here, we constrain the tropical hydrological cycle edge trends with formal detection and attribution techniques, and show that there is, in fact, strong evidence that the observed poleward shift during SON can be likely attributed to human activity.

Results

Constraining the tropical hydrological cycle expansion

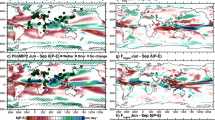

We start by examining the evolution of the Northern Hemisphere autumn (September-November, SON) zonal mean tropical hydrological cycle edge in both observation-based reanalyses and climate models from the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6; under the historical and SSP5-8.5 experiments) (Methods) (Fig. 1a, c). Specifically, to assess both the dynamical and thermodynamical changes in the tropical hydrological cycle, we focus on two metrics for its edge: the edge of the Hadley cell (ϕΨ500; estimated using the meridional mass streamfunction) and the dry zone (ϕP-E; estimated using surface precipitation-minus-evaporation) (Methods). First, CMIP6 models simulate a monotonic poleward shift in both metrics (red lines) with a ~2.2 ± 1. 7° shift by the end of this century (the difference between the last 20 years of the 21st and 20th centuries) in ϕΨ500, and ~1.6 ± 1.14° shift in ϕP-E (the ± represents the 5–95% range across the models, i.e., ±1.64 standard deviations). Second, reanalyses also show a poleward expansion in both metrics over recent decades (black lines). Quantitatively, over the 1979–2014 period, ϕΨ500 and ϕP-E have respectively expanded at a rate of ~0.04 ± 0.019 degrees yr−1 and ~0.04 ± 0.038 degrees yr−1 in reanalyses (black error bars in Fig. 1b, d), and at a rate of ~0.016 ± 0.037 degrees yr−1 and ~0.014 ± 0.027 degrees yr−1 in CMIP6 models (orange error bars in Fig. 1b, d). We note that while the mean expansion rates in reanalyses are larger than in most models, they are within the CMIP6 model distribution; approximately half of the models are within the reanalyses trends uncertainty (within the 5–95% range; compare black and orange error bars). Lastly, we focus here on the 1979–2014 period for two reasons: 1) the assimilation of global satellite data and thus most reanalyses start in 1979, and 2) 2014 is the last year of both the (non-preliminary) observed sea-level pressure data discussed below and the historical CMIP6 runs, which we use for the detection-attribution analysis.

The evolution of the SON a Hadley cell edge (ϕΨ500) and c dry zone edge (ϕP−E), relative to the 1980-1999 period, in reanalyses mean (black, through 2019) and CMIP6 mean (red, through 2099 under the SSP5-8.5 scenario). Thin lines show the evolution of individual reanalyses and shading the two standard deviations across models. The 1979–2014 trends in b ϕΨ500 and d ϕP−E plotted against the \({\phi }_{{{{\rm{PSL}}}}_{{{\rm{y}}}}}\) trends across CMIP6 models (red dots); their correlation appears in the upper left corners. Red line shows the linear regression and shading the two standard deviations (Methods). The blue square shows the observed \({\phi }_{{{{\rm{PSL}}}}_{{{\rm{y}}}}}\). The orange, black and purple squares respectively show the mean of the CMIP6, reanalyses and the constrained ϕΨ500 or ϕP−E. Errorbars show the 5–95% range (1.64 standard deviations).

Prior to using reanalyses to quantify the role of anthropogenic emissions in the tropical belt expansion, we recall that previous work found that biases in reanalyses likely result in artificial changes of the Hadley circulation in those products2,5,13,14. To ensure that the poleward expansion rates seen in reanalyses are not biased, it is crucial to compare the reanalyses trends to trends based on a directly observable quantity. Since observational measurements of ϕΨ500 and ϕP-E are unavailable, we next use emergent constraint analyses based on sea level pressure observations to constrain the historical expansion of the tropics. Emergent constraint analysis exploits an empirical physically-based relation across climate models between two climate variables, and uses observations of one variable to constrain the other25. While such analyses have been mostly used to constrain projected climate changes26, based on the historical climate, here an emergent constraint analysis is used to observationally constrain the historical shift of the edge of the hydrological cycle (Methods).

In particular, the edge of the tropics was argued to follow the latitudinal position of zero meridional gradient of sea level pressure27 (\({\phi }_{{{{\rm{PSL}}}}_{{{\rm{y}}}}}\)). This link was suggested to stem from both the momentum equations and from the understanding that subtropical highs (regions of maximum sea level pressure) are located at the edge of the tropical region where the air of the Hadley cell descends and the surface easterlies and westerlies diverge. If the above link between the edge of the tropics (i.e., ϕΨ500 and ϕP-E) and \({\phi }_{{{{\rm{PSL}}}}_{{{\rm{y}}}}}\) holds, the available measurements of sea-level pressure could thus allow one to constrain the historical expansion of ϕΨ500 and ϕP-E (Methods).

Indeed, across CMIP6 models, during SON, the 1979–2014 trends in \({\phi }_{{{{\rm{PSL}}}}_{{{\rm{y}}}}}\) are linearly related to the trends in ϕΨ500 (r = 0.73) and ϕP-E (r = 0.63) (red dots in Fig. 1b, d). To assess the observed trend in \({\phi }_{{{{\rm{PSL}}}}_{{{\rm{y}}}}}\) we use data from the International Comprehensive Ocean-Atmosphere Data Set (ICOADS), which provides oceanic measurements of sea-level pressure (Methods; using data from the Hadley Centre Sea Level Pressure dataset, HadSLP2, yields similar results, Supplementary Fig. 2). By conducting emergent constraint analyses (Fig. 1b, d, Methods) with the observed \({\phi }_{{{{\rm{PSL}}}}_{{{\rm{y}}}}}\) trend of 0.04 ± 0.06 degrees yr−1 (blue error bars in Fig. 1b, d), together with the linear relation between ϕΨ500 or ϕP-E and \({\phi }_{{{{\rm{PSL}}}}_{{{\rm{y}}}}}\), while accounting for the uncertainties in both the observed trend and the linear relation, we constrain the historical expansion of the tropical hydrological cycle (purple bars in Fig. 1b, d). In particular, the emergent constraint analyses suggest an expansion rate over the 1979–2014 period in ϕΨ500 and ϕP-E of ~0.045 ± 0.066 degrees yr−1 and ~0.034 ± 0.047 degrees yr−1, respectively; extending the emergent constraint analysis through 2024 using the preliminary ICOADS data yields similar results (Supplementary Fig. 3).

The constrained expansion rates show a similar value as the mean reanalysis expansion rates in both ϕΨ500 and ϕP-E (compare purple and black squares), and the reanalyses’ trends fall well within the constrained trends uncertainty. The consistency between the reanalyses and the observed SLP-based tropical expansion provides us confidence in the reanalyses’ expansion rates in both ϕΨ500 and ϕP-E. Models also capture the observationally constrained expansion rates: almost all of the models are within the constrained trends uncertainty (within the 5–95% range) (compare purple and orange error bars in Fig. 1b, d). This consistency between models and observations provides confidence in the projected tropical expansion by the end of this century (Fig. 1a, c).

Quantifying the role of human emissions

To what degree have anthropogenic emissions contributed to the observed expansion of the tropics during SON? To answer this question, we next conduct a formal detection-attribution analysis. The detection analysis allows us to determine whether the recent observed tropical expansion has emerged from internal climate variability. Specifically, we take a signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) approach4,5,6,28,29,30, where the signal is defined as the 1979–2014 trends in ϕΨ500 and ϕP-E (estimated from either the reanalyses or the emergent constraint), and the noise as the standard deviation of all 36-year trends in ϕΨ500 and ϕP-E that arise solely due to internal variability, estimated from the long preindustrial control runs of each CMIP6 model (Methods); estimating the noise using single model large-ensembles yields similar results (Methods, Supplementary Fig. 4).

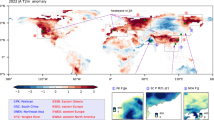

We find that the constrained ϕΨ500 and ϕP-E 1979–2014 trends during SON exhibit SNR values larger than 2 (red symbols in Fig. 2a). Specifically, the emergent constraint for the ϕΨ500 and ϕP-E trends shows SNR values of 2.5 ± 0.38 and 2.7 ± 0.23, respectively. In other words, the observationally constrained expansion exceeded two standard deviations of the internal variability. This analysis thus points to the important role of external forcing in driving the observed tropical expansion since it is very unlikely that internal variability alone could have driven the magnitude of the observed trends. Applying the SNR analysis to the reanalyses trends yields similar results of SNR values of 2.3 ± 0.3 and 3.4 ± 0.3 for the ϕΨ500 and ϕP-E trends, respectively (black symbols in Fig. 2a). We note that SON is the unique season when NH tropical expansion emerges from internal variability, while during other seasons the SNR remains below 2 (Supplementary Fig. 5).

a Signal-to-noise ratio and b Fractional Attributional Risks (FAR) analyses for the constrained (red) and reanalyses (black) 1979–2014 trends in the Hadley cell (ϕΨ500) and dry zone (ϕP−E) edges during SON. Errorbars show the 95% confidence intervals (Methods). The horizontal dashed line marks a signal-to-noise ratio value of 2 (where the signal exceeds 2 s.d. of the internal variability). c, d as in panels (a) and (b), respectively, only for ϕP−E in reanalyses over specific regions.

To determine whether it is anthropogenic or natural forcings that contribute to the poleward expanding tropics, we next apply a Fractional Attributable Risks (FAR) analysis5,6,31,32 (Methods) to the historical trends in ϕΨ500 and ϕP-E. FAR is estimated using the probability of exceeding the observed 1979–2014 trends across CMIP6 models with (PA) and without (PN) anthropogenic emissions. Specifically, FAR is defined as 1 − PN/PA, such that it provides the chance (between 0 and 1) that the observed trend can be attributed to anthropogenic emissions. In addition, PA/PN informs us on how much anthropogenic emissions increased the probability of having the observed trend.

Over the 1979-2014 period, the constrained ϕΨ500 and ϕP-E trends respectively show FAR values of 0.75 ± 0.08 and 0.85 ± 0.05 (red symbols in Fig. 2b) suggesting that there is ~75% and ~85% chance that the expansion in ϕΨ500 and ϕP-E can be attributed to anthropogenic emissions, respectively. In other words, human activity increased the probability of observing such an expansion in ϕΨ500 and ϕP-E by a factor of 4 and 6.6, respectively. We again note that applying the FAR analysis to the reanalysis trends yields similar results with FAR values of 0.71 ± 0.06 and 0.88 ± 0.04 for ϕΨ500 and ϕP-E, respectively (black symbols in Fig. 2a). The consistency in detection-attribution analysis between the observed SLP-based and reanalyses trends increases our confidence in the ability of the reanalyses to accurately capture the human influence on the historical expansion of the hydrological cycle.

We thus next use the reanalyses to unravel the regional impacts of anthropogenic emissions. Specifically, we aim to identify over which regions anthropogenic emissions acted to expand the dry zone edge in recent decades; we here use reanalyses and not the observed SLP-based dry zone edge from the emergent constraint since the observed sea-level pressure in ICOADS used in the emergent constraint is available only over ocean. To this end, we first repeat the detection analysis for ϕP-E averaged over four subtropical regions: Euro-Asia (0°–130°E), Pacific Ocean (130°E–120°W), North America (120°W–70°W), and Atlantic Ocean (70°W–0°). We find that, over the 1979-2014 period, the expansion of the dry zone edge emerged from internal variability over oceans, but not over land (Fig. 2c); similar results are evident by estimating the noise using single model large-ensembles (Methods, Supplementary Fig. 4). Specifically, SNR values of 2.7 ± 0.3 and 2.8 ± 0.3 are evident over the Pacific and Atlantic basins, respectively, while values of 0.7 ± 0.2 and 1.2 ± 0.14 are evident over Euro-Asia and North America, respectively. Note that while the signal is similar over the different regions (Supplementary Fig. 6), the larger internal variability (noise) over land relative to ocean reduces the land SNR values and obscures the signal’s detection.

Given that external forcing is playing an important role in the expansion of ϕP-E only over oceans, we next conduct the FAR analysis over the Pacific and Atlantic basins (note that similar to the zonal mean, also over ocean approximately half of the models are within the reanalyses ϕP-E trends uncertainty). We find that there is ~72% and ~85% chance that the ϕP-E expansion can be attributed to anthropogenic emissions, over the Pacific and Atlantic oceans, respectively (Fig. 2d). Anthropogenic emissions thus increased the probability of observing such an expansion in ϕP-E by a factor of 3.6 and 6.6 over the Pacific and Atlantic oceans, respectively. Lastly, we note that while the climatological position of the zonal mean hydrological cycle edge lies at ~40°N during SON, it varies across the different regions. Specifically, over the Atlantic basin, the position of the dry zone edge reaches ~45°N, whereas in the Pacific basin, it is mostly situated between 35° and 40°N (Fig. 3). Thus, the impacts of human emissions to shift the dry zone edge poleward have likely affected higher latitudes over the Atlantic and the adjacent land regions to the east (downstream) in Portugal and Spain, relative to the Pacific and the associated impacts over the southwest United States (Supplementary Fig. 7).

The physics underlying the human-induced tropical expansion

The expansion of the tropics, and specifically the expansion of the Hadley cell in response to future anthropogenic emissions, was found to follow a simple scaling for the Hadley cell edge (in radians)33,34, \({\phi }_{H00}={\left(\frac{NH}{\Omega a}\right)}^{0.5}\), where N is static stability, H is tropopause height averaged over the subtropics (here defined between 35°N–45°N) (Methods), and Ω and a are Earth’s rotation rate and radius, respectively. This scaling is derived by assuming that the edge of the circulation occurs at the latitude where the upper-level angular momentum conserving flow becomes baroclinically unstable35. Thus, to elucidate the mechanisms underlying the anthropogenically-induced tropical expansion, we next analyze the CMIP6 mean (i.e., the forced response) changes in ϕH00.

First, the CMIP6 mean 1979-2014 SON ϕH00 trends show similar magnitude as the ϕΨ500 trends of ~ 0.012 ± 2 × 10−3 degrees yr−1 (compare red and gray bars in Fig. 4a); we note that while ϕH00 captures the CMIP6 mean ϕΨ500 trends, it underestimates the CMIP6 model spread (black error bars). Second, further decomposing the ϕH00 trends into the relative contributions from static stability and tropopause height (δϕH00 = (Ωa)−0.5(δN 0.5[H 0.5] + δH 0.5[N 0.5]), where the square brackets represent the 1979-2014 mean and δ the deviation therefrom) reveals that the increase in tropopause height mostly contributes to the expansion in ϕH00, while static stability only has a minor contribution (Fig. 4b). This is consistent with the low correlations found in previous work between the changes in SON ϕΨ500 and static stability under an idealized increase in CO2 level21.

a The 1979-2014 trends in the Hadley cell edge (ϕΨ500, red) and in the edge’s scaling (ϕH00, gray). b The relative contribution of static stability (H00∣N, red) and tropopause height (H00∣H, blue) to the ϕH00 trends (gray). c Probability density plot of the 1979-2014 trends in ϕΨ500 plotted against the tropopause height (H) trends across CMIP6 models. The correlation appears in the upper left corner. d The relative contributions to tropopause height trends (gray) from surface temperature (H∣Tsur, red), tropospheric lapse rate (H∣Γ, blue) and stratospheric temperature (H∣Tstr, pink). Errorbars show the 95% confidence intervals.

The tropopause height increase over the 1979–2014 period indeed correlates with the ϕΨ500 trends across CMIP6 models (r = 0.66, Fig. 4c). To reveal the processes that could contribute to the increase in tropopause height, we next follow previous studies36,37,38,39 and analyze a simple diagnostic equation for changes in tropopause height (Methods). Specifically, by assuming a linear decrease in tropospheric temperature with height (i.e., constant lapse rate) and isothermal stratosphere, the changes in tropopause height (δH) can be written as, \(\delta H=-\frac{\delta {T}_{sur}}{\left[\Gamma \right]}-\frac{\left[H\right]\delta \Gamma }{\left[\Gamma \right]}+\frac{\delta {T}_{str}}{\left[\Gamma \right]}\), where Tsur is surface temperature, Γ is the tropospheric lapse rate, and Tstr is the stratospheric temperature. Examining the 1979-2014 trends in the different components of the tropopause height equation reveals that changes in surface temperature contribute the most to the increase in tropopause height, while changes in the tropospheric lapse rate and stratospheric temperature have minor impacts (Fig. 4d); we note that the tropopause height trend is ~ 90% of the sum of the individual contributions. Consistent with the larger CMIP6 mean Hadley cell expansion in SON relative to the other seasons, the increases in tropopause height and surface warming in the NH subtropics are also larger in SON in comparison to other seasons (Supplementary Fig. 8). The larger surface warming in SON was argued in previous work to be linked to seasonal variations in mixed layer depth in the mid-latitude oceans21. Lastly, previous work found it insightful to formulate the transition between moist and dry regions in the tropics as a free boundary problem40. Such an idealized approach could be also applied to the shift of the dry zone edge found here, to better understand, using simpler models, the underlying physics.

Discussion

The projected poleward shift of the tropical hydrological cycle edge holds large impacts in subtropical regions. Specifically, such a shift is expected to dry semi-arid regions, where water availability is already scarce. To date, the tropical expansion has been observed in the Southern Hemisphere, and attributed to anthropogenic emissions, while no clear signal has emerged in the Northern Hemisphere1. Yet, previous modeling studies showed that in response to greenhouse gas emissions the expansion during boreal autumn might be as large as in the Southern Hemisphere21.

Here we revisit whether forced tropical expansion has already been observed in the Northern Hemisphere by applying several new methodologies not used in previous studies on this topic. We use sea-level pressure measurements to constrain the boreal autumn historical expansion of the tropical hydrological cycle (the Hadley cell and the subtropical dry zone), and then use formal detection and attribution techniques to show that it has emerged from internal variability. Moreover, we find that there is ~80% chance that anthropogenic emissions have shifted the tropical hydrological cycle edge poleward during this season. In other words, human activity increased the probability of observing such an expansion by a factor of ~5. Similar trends are found in atmospheric reanalyses and in climate models—mostly those of high-end trends—which increases our confidence in their long-term trends of the tropical edge. We also stress the importance of extending the research on the impacts of human emissions on the large-scale flow to different seasons other than summer and winter or the annual mean (i.e., spring and autumn) to fully assess any human-induced climate changes.

Our analysis suggests that the human-induced subtropical surface warming during boreal autumn is playing a key role in shifting the tropical hydrological cycle edge poleward. More specifically, regionally, we find that the human-induced poleward shift of the dry zone edge is evident over the Atlantic and Pacific basins, but not over land, due to the larger internal variability over the continents, relative to the oceans. First, this could have large impacts for oceanic ecosystems. For example, while changes in the Hadley cell edge could affect surface wind stress, and thus the upwelling of nutrients from the deep ocean41, changes in the dry zone edge could impact ocean salinity, and hence both might impact marine organisms. Second, changes in the dry zone edge over ocean basins are associated with hydrological impacts on the adjacent land masses, particularly those to the east (downstream) of the oceans (Supplementary Fig. 7). Most notably, the recent poleward shift in the Atlantic dry zone edge could have contributed to drying in the western Mediterranean region.

Methods

Tropical hydrological cycle extent

To examine changes in the edge of the tropics, we analyze two different metrics that capture the dynamic and thermodynamic states of the hydrological cycle. The first, is the edge of the Hadley circulation defined using the meridional mass streamfunction,

where ϕ and p are the latitude and pressure, respectively, a is Earth’s radius, g is gravity, and \(\overline{v}\) is the meridional velocity averaged zonally and seasonally (denoted by an overbar). The Hadley cell edge (ϕΨ500) is the latitude where Ψ at 500 mb first changes sign between the subtropics and extra-tropics. The second metric, which accounts for the dry zone edge (ϕP−E), is defined as the latitude where surface precipitation (P) first exceeds surface evaporation (E) between the subtropics and extra-tropics, i.e., P − E > 0. We first apply a 0. 1° latitudinal cubic interpolation to Ψ and P − E prior to calculating each metric.

Reanalyses

To examine the historical changes in the extent of the tropical hydrological cycle, we here use monthly data from four different reanalyses products over the 1979-2019 period: ERA542, JRA-5543, MERRA244 and CFSR V245. Reanalyses assimilate atmospheric and surface measurements to general circulation models thus, aiming to provide one with the best assessment of the atmospheric state. We here focus on the post-1979 period since most of the reanalyses products have available data over this period and the reanalyses also assimilate satellite data.

CMIP6

To assess the role of anthropogenic emissions in the expansion of the tropics, we here examine 41 models from the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6; Supplementary Table 1). Specifically, we use the ’r1i1p1f1’ member from each model (to weigh all models equally) integrated under four experiments: historical (through 2014), hist-nat (historical with only natural forcings; through 2014), the Shared Socioeconomic Pathway 5-8.5 (SSP5-8.5; through 2100) and piControl (control runs with constant 1850 forcings). We examine the last 200 years of each model’s control run, which allows us to gather enough statistics to assess the internal variability of the tropical edge needed for the detection analysis. In addition, we also estimate the internal variability of tropical edge trends using four single model large ensembles: ACCESS-ESM5 (of 40 members), CanESM5 (of 25 members), MIROC6 (of 50 members) and MPI-ESM-LR (of 30 members).

Sea-level pressure

To ensure that the expansion rates seen in reanalyses are not artificial, and to have observation-based evidence for the expanding tropics, we make use of sea-level pressure measurements from the International Comprehensive Ocean-Atmosphere Data Set46 (ICOADS) over the 1979-2014 period. ICOADS collects millions of sea-level pressure measurements per year (from ships, buoys, coastal stations, etc.). ICOADS data beyond 2014 is considered preliminary and is subject to change, and is thus not used in the main analysis. Yet, extending our emergent constraint analysis to 2024 yields similar results (Supplementary Fig. 3). We further verify the results using ICOADS with sea-level pressure data from the Hadley Centre Sea Level Pressure dataset47 (HadSLP2; through 2004), which adds to the oceanic ICOADS data measurements the surface pressure over land. The edge of the tropics using sea-level pressure data is estimated, following previous work24,27, as the latitude where the meridional gradient of sea-level pressure first changes sign between the subtropics and extra-tropics (\({\phi }_{{{{\rm{PSL}}}}_{{{\rm{y}}}}}\)), with the same 0. 1° latitudinal cubic interpolation as the other metrics.

Emergent constraint

We here use emergent constraints to define observed SLP-based tropical hydrological cycle edge metrics. Emergent constraints exploit a mathematical relation, with a robust physical relation as well, between two climate variables, and use observations of one variable to constrain the other25. While emergent constraint analysis usually constrains projected climate changes by linking them to the historical climate, here, we aim to observationally constrain the historical shift of the edge of the hydrological cycle. To this end, we use the relation between the latitude of zero sea-level pressure gradient and the edge of the hydrological cycle. This link was suggested to stem from both the momentum equations and from the understanding that subtropical highs (regions of maximum sea level pressure) are located at the edge of the tropical region where the air of the Hadley cell descends and the surface easterlies and westerlies diverge27. Using measurements of sea-level pressure, we then constrain the edges of the Hadley cell and of the dry zone.

Specifically, we follow previous studies5,26,48,49,50, and estimate the linear relation, across models, between the 1979–2014 trends in ϕP−E or ϕΨ500 and \({\phi }_{{{{\rm{PSL}}}}_{{{\rm{y}}}}}\) using a total least square linear regression, where the uncertainties in the two variables are computed as the standard deviation across the CMIP6 models. A bootstrap replacement procedure of 100 iterations across the models is used to estimate the uncertainty in the linear regressions. Then, a regression analysis is conducted to each replacement, yielding 100 values of ϕP−E or ϕΨ500 for each \({\phi }_{{{{\rm{PSL}}}}_{{{\rm{y}}}}}\) value, and their standard deviation is used to assess the uncertainty in the regression (the P{x∣y} distribution). The constrained ϕP−E or ϕΨ500 probability distributions (P(y)) are estimated as \(P(y)=\int_{-\infty }^{\infty }P(x)P\{x| y\}dx\), where P(x) is the probability distribution of \({\phi }_{{{{\rm{PSL}}}}_{{{\rm{y}}}}}\) estimated using the mean \({\phi }_{{{{\rm{PSL}}}}_{{{\rm{y}}}}}\) trend and its standard error (which includes internal variability and inherent year-to-year observed \({\phi }_{{{{\rm{PSL}}}}_{{{\rm{y}}}}}\) biases).

Detection-attribution analysis

To quantify the role of anthropogenic emissions, we conduct a formal detection-attribution analysis. Specifically, for the detection analysis, we take a signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) approach where the 1979–2014 trends in the edge of the tropical hydrological cycle (the signal) are compared to the standard deviation of all 36-year trends (total of 165) in each model’s preindustrial control run (the noise, which accounts only for the internal variability of tropical edge trends). The SNR mean and uncertainty are, respectively, the mean and 95% confidence interval across the SNR values from all control runs (for the reanalyses, the SNR mean and uncertainty are shown for the mean reanalyses signal). We further verify the SNR analysis by assessing the noise using the four single model large ensembles. In particular, the noise is defined in each ensemble as the standard deviation of the 1979–2014 trends in the edge of the tropical hydrological cycle across all members, after removing the ensemble mean trend.

For the attribution analysis, we make use of a Fractional Attributable Risks (FAR) analysis5,6,31,32, where we estimate the probability of having the signal in CMIP6 models with (PA, under the historical forcing) and without (PN, under the hist-nat forcing) anthropogenic emissions. FAR is defined as 1 − PN/PA, thus providing the chance (between 0 and 1) of the signal being attributed to anthropogenic emissions. To ensure that the FAR analysis is not affected by the different number of models available in the historical and hist-nat experiments, which yields different distributions, we estimate the distribution in each experiment by centering all 36-year trends in each model’s preindustrial control run around the multi-model mean trend in each experiment. The FAR mean and uncertainty are respectively the mean and 95% confidence interval across the FAR values using all control runs.

Tropopause height

The tropopause height (H) is computed following the WMO definition as the lowest level where the vertical temperature gradient crosses the 2 K km−1 value, and stays on average below this value in higher levels within 2 km. To identify the different processes affecting the changes in tropopause height we follow previous work36,37,38,39 and by assuming constant tropospheric lapse rate (Γ, estimated using a linear regression over the tropospheric temperature) and isothermal stratosphere the temperature at the stratosphere (Tstr) can be written as Tstr = Tsur + ΓH, where Tsur is the surface temperature. Assessing the changes in Tstr leads to the following equation for tropopause changes \(\delta H=-\frac{\delta {T}_{sur}}{\left[\Gamma \right]}-\frac{\left[H\right]\delta \Gamma }{\left[\Gamma \right]}+\frac{\delta {T}_{str}}{\left[\Gamma \right]}\), where the square brackets represent the 1979-2014 mean.

Data availability

The data used in the manuscript is publicly available for CMIP6 data (https://esgf-node.llnl.gov/projects/cmip6/), JRA55, CFSR and MERRA2 (https://rda.ucar.edu/) and ERA5 (https://www.ecmwf.int).

Code availability

Codes used to calculate the meridional mass streamfunction and meridional gradient are available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7529584.

References

Masson-Delmotte, V. et al. Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2021).

Grise, K. M. et al. Recent tropical expansion: natural variability or forced response? J. Clim. 32, 1551–1571 (2019).

Dong, B., Sutton, R. T., Shaffrey, L. & Harvey, B. Recent decadal weakening of the summer Eurasian westerly jet attributable to anthropogenic aerosol emissions. Nat. Commun. 13, 1148 (2022).

Chemke, R., Ming, Y. & Yuval, J. The intensification of winter mid-latitude storm tracks in the Southern Hemisphere. Nat. Clim. Change 12, 553–557 (2022).

Chemke, R. & Yuval, J. Human induced weakening of the Northern Hemisphere tropical circulation. Nature 617, 529–532 (2023).

Chemke, R. & Coumou, D. Human influence on the recent weakening of storm tracks in boreal summer. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 7, 86 (2024).

Shaw, T. A. et al. Emerging climate change signals in atmospheric circulation. AGU Adv. 5, 2024AV001297 (2024).

Feng, S. & Fu, Q. Expansion of global drylands under a warming climate. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 13, 10081–10094 (2013).

Fu, Q., Johanson, C. M., Wallace, J. M. & Reichler, T. Enhanced mid-latitude tropospheric warming in satellite measurements. Science 312, 1179 (2006).

Seidel, D. J., Fu, Q., Randel, W. J. & Reichler, T. J. Widening of the tropical belt in a changing climate. Nat. Geosci. 1, 21–24 (2008).

Johanson, C. M. & Fu, Q. Hadley cell widening: model simulations versus observations. J. Clim. 22, 2713 (2009).

Allen, R. J., Sherwood, S. C., Norris, J. R. & Zender, C. S. Recent Northern Hemisphere tropical expansion primarily driven by black carbon and tropospheric ozone. Nature 485, 350–354 (2012).

Chemke, R. & Polvani, L. M. Opposite tropical circulation trends in climate models and in reanalyses. Nat. Geosci. 12, 528–532 (2019).

Davis, N. A. & Davis, S. M. Reconciling Hadley cell expansion trend estimates in reanalyses. Geophys. Res. Lett. 45, 11,439–11,446 (2018).

Amaya, D. J., Siler, N., Xie, S. & Miller, A. J. The interplay of internal and forced modes of Hadley Cell expansion: lessons from the global warming hiatus. Clim. Dyn. 51, 305–319 (2018).

Grise, K. M. & Davis, S. M. Hadley cell expansion in CMIP6 models. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 20, 5249–5268 (2020).

Son, S.-W., Tandon, N. F., Polvani, L. M. & Waugh, D. W. Ozone hole and Southern Hemisphere climate change. Geophys. Res. Lett. 36, L15705 (2009).

Polvani, L. M., Waugh, D. W., Correa, G. J. P. & Son, S. W. Stratospheric ozone depletion: the main driver of twentieth-century atmospheric circulation changes in the southern hemisphere. J. Clim. 24, 795–812 (2011).

D’Agostino, R., Scambiati, A. L., Jungclaus, J. & Lionello, P. Poleward shift of northern subtropics in winter: time of emergence of zonal versus regional signals. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e89325 (2020).

Grise, K. M. & Polvani, L. M. Is climate sensitivity related to dynamical sensitivity? J. Geophys. Res. 121, 5159–5176 (2016).

Watt-Meyer, O., Frierson, D. M. W. & Fu, Q. Hemispheric asymmetry of tropical expansion under CO2 forcing. Geophys. Res. Lett. 46, 9231–9240 (2019).

Grise, K. M. & Polvani, L. M. The response of midlatitude jets to increased CO2: distinguishing the roles of sea surface temperature and direct radiative forcing. Geophys. Res. Lett. 41, 6863–6871 (2014).

Allen, R. J. & Kovilakam, M. The role of natural climate variability in recent tropical expansion. J. Clim. 30, 6329–6350 (2017).

Grise, K. M., Davis, S. M., Staten, P. W. & Adam, O. Regional and seasonal characteristics of the recent expansion of the tropics. J. Clim. 31, 6839–6856 (2018).

Hall, A., Cox, P., Huntingford, C. & Klein, S. Progressing emergent constraints on future climate change. Nat. Clim. Change 9, 269–278 (2019).

Chemke, R. & Yuval, J. Atmospheric circulation to constrain subtropical precipitation projections. Nat. Clim. Change 15, 287–292 (2025).

Choi, J., Son, S., Lu, J. & Min, S. Further observational evidence of Hadley cell widening in the Southern Hemisphere. Geophys. Res. Lett. 41, 2590–2597 (2014).

Santer, B. D. et al. Identifying human influences on atmospheric temperature. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110, 26–33 (2013).

Hawkins, E. & Sutton, R. Time of emergence of climate signals. Geophys. Res. Lett. 39, L01702 (2012).

Hess, O. & Chemke, R. Anthropogenic forcings reverse a simulated multi-century naturally-forced Northern Hemisphere Hadley cell intensification. Nat. Commun. 15, 4001 (2024).

Stott, P. A., Stone, D. A. & Allen, M. R. Human contribution to the European heatwave of 2003. Nature 432, 610–614 (2004).

Stott, P. A. et al. Attribution of extreme weather and climate-related events. WIREs Clim. Change 7, 23–41 (2016).

Lu, J., Vecchi, G. A. & Reichler, T. Expansion of the Hadley cell under global warming. Geophys. Res. Lett. 34, L06805 (2007).

Chemke, R. & Polvani, L. M. Exploiting the abrupt 4xCO2 scenario to elucidate tropical expansion mechanisms. J. Clim. 32, 859–875 (2019).

Held, I. M. The general circulation of the atmosphere. Program in Geophysical Fluid Dynamics, Woods Hole, MA, Woods Hole (Oceanographic Institute, 2000). [Available online at http://www.whoi.edu].

Vallis, G. K., Zurita-Gotor, P., Cairns, C. & Kidston, J. Response of the large-scale structure of the atmosphere to global warming. Q.J.R. Meteorol. Soc. 141, 1479–1501 (2015).

Chemke, R. & Polvani, L. M. Ocean circulation reduces the Hadley cell response to increased greenhouse gases. Geophys. Res. Lett. 45, 9197–9205 (2018).

Chemke, R., Polvani, L. M. & Deser, C. The effect of Arctic Sea ice loss on the Hadley circulation. Geophys. Res. Lett. 46, 963–972 (2019).

Chemke, R. The future poleward shift of Southern Hemisphere summer mid-latitude storm tracks stems from ocean coupling. Nat. Commun. 13, 1730 (2022).

Khouider, B., Majda, A. J. & Stechmann, S. N. Climate science in the tropics: waves, vortices and PDEs. Nonlinearity 26, R1 (2013).

Schmidt, D. F., Amaya, D. J., Grise, K. M. & Miller, A. J. Impacts of shifting subtropical highs on the California current and canary current systems. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e88996 (2020).

Hersbach, H. et al. The ERA5 global reanalysis. Q.J.R. Meteorol. Soc. 146, 1999–2049 (2020).

Kobayashi, S. et al. The JRA-55 Reanalysis: general specifications and basic characteristics. J. Meteor. Soc. Japan 93, 5–48 (2015).

Gelaro, R. et al. The Modern-Era retrospective analysis for research and applications, Version 2 (MERRA-2). J. Clim. 30, 5419–5454 (2017).

Saha, S. et al. The NCEP climate forecast system version 2. J. Clim. 27, 2185–2208 (2014).

Freeman, E. et al. ICOADS release 3.0: a major update to the historical marine climate record. Int. J. Climatol. 37, 2211–2232 (2017).

Allan, R. & Ansell, T. A new globally complete monthly historical gridded mean sea level pressure dataset (HadSLP2): 1850 2004. J. Clim. 19, 5816 (2006).

Cox, P. M. et al. Sensitivity of tropical carbon to climate change constrained by carbon dioxide variability. Nature 494, 341–344 (2013).

Cox, P. M., Huntingford, C. & Williamson, M. S. Emergent constraint on equilibrium climate sensitivity from global temperature variability. Nature 553, 319–322 (2018).

Simpson, I. R. et al. Emergent constraints on the large-scale atmospheric circulation and regional hydroclimate: do they still work in cmip6 and how much can they actually constrain the future? J. Clim. 34, 6355–6377 (2021).

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgments: R.C. is grateful to the support by the Willner Family Leadership Institute for the Weizmann Institute of Science and the Zuckerman STEM Leadership Program. K.M.G. is supported in part by the National Science Foundation under Grant AGS-2330009.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.C. and K.M.G. equally contributed to this work. R.C. analyzed the data and together with K.M.G. discussed and wrote the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chemke, R., Grise, K.M. Seasonal emergence of human-caused expansion of the boreal tropical hydrological cycle. npj Clim Atmos Sci 8, 313 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-01203-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-01203-9