Abstract

The number of tropical cyclones (TCs) over the western North Pacific (WNP) dropped to a record low in 2023, with less than 40% forming during the boreal autumn. While a strong El Niño, positive Indian Ocean Dipole (pIOD), and strong tropical North Atlantic warming coexisted, their relative contributions to the suppressed TC genesis remain unclear. Through observational analyses and model experiments, we demonstrate that the tropical Atlantic and Pacific exerted minimal influence on TC genesis over the WNP. In contrast, the pIOD played a dominant role in suppressing TC activities over the central WNP, where the decline was most pronounced. Specifically, the pIOD induced easterly wind anomalies over the Indo-western Pacific, leading to descending anomalies over the WNP that inhibited TC genesis. Our findings highlight the importance of incorporating the IOD into future seasonal TC forecasts to improve its prediction skill.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Tropical cyclones (TCs) are one of the most destructive weather systems on Earth. Their genesis locations and frequency directly impact their trajectories and landfalling locations, leading to severe societal and economic influences. The western North Pacific (WNP; 105°E–180°E, 5°N–30°N) is the most active TC basin in the world, generating approximately 25 TCs annually on average. TC activities are particularly frequent from boreal summer (June–August, JJA) to autumn (September–November, SON), accounting for 85% of the annual TC occurrences. However, TC characteristics differ significantly between these two seasons1,2,3. During boreal autumn, intense TCs over the WNP occur more frequently3,4, and have exhibited increased frequency of passing through East Asia in recent years5, causing significant damage to the surrounding countries. Therefore, boreal autumn TCs demand great attention and effective disaster prevention measures due to their significant destructiveness.

TC activities over the WNP experienced an unprecedented decline in 20236, with the tropical cyclone genesis frequency (TCGF) over the WNP during June–November reaching its lowest level since 1980. Only 13 TCs formed in the WNP, amounting to approximately 60% of the climatological mean value (based on TC best-track data from the Joint Typhoon Warning Center (JTWC) during 1980–2022). Specifically, nine TCs occurred in the WNP during boreal summer, while only four TCs during boreal autumn. Although the summer TCGF was not a significant deviation from its climatological mean of 10.8, the autumn TCGF fell to its lowest value in the satellite era—significantly below the normal of 10.7. The dramatic reduction in autumn TCGF contributed to 80% of the total TCGF decline during June–November 2023, highlighting the need for a detailed seasonal analysis.

It is widely recognized that the sea surface temperature anomalies (SSTAs) across the three tropical oceans and their interactions significantly modulate WNP TCGF on the interannual time scale7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18. For instance, El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO) is the most dominant signal influencing year-to-year variations in the WNP TCGF16,19,20,21. Changes in oceanic and atmospheric conditions associated with El Niño typically lead to an eastward shift of TCGF, with increases in the southeastern WNP and decreases in the northwestern WNP15,17,19,22. The WNP TCGF also shows a significant negative correlation with tropical North Atlantic (TNA) SSTA. Warm TNA strengthens both the tropical Pacific easterly trade winds and upper-level westerlies, creating an unfavorable environment for TC genesis over the WNP, suppressing TC activities particularly over the eastern WNP11,13,14.

The Indian Ocean also plays a crucial role in modulating WNP TC activities. As the first mode of the tropical Indian Ocean SST variability, the basin-scale warming of the Indian Ocean induces prominent easterly wind anomalies over the equatorial western Pacific as atmospheric Kelvin waves, thereby suppressing TCGF over the WNP during its peak in summer7,23. The Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD) is the second mode of tropical Indian Ocean SST variability, which typically develops in summer and matures in autumn24. The IOD events are characterized by opposite SSTAs between the southeastern and western tropical Indian Ocean, which can induce local circulation changes and further influence regional and global climate through atmospheric teleconnections25,26. However, the IOD’s impact on WNP TC activity is often overlooked in forecasts, primarily due to its strong correlation with ENSO and a relatively weak statistical relationship with TCGF across the entire WNP region during the whole typhoon season6.

During June–November 2023, global SST reached an unprecedented high27. This period was characterized by the rare concurrence of a strong El Niño event, record-breaking warm SSTs over the TNA, and a strong positive Indian Ocean Dipole (pIOD) event. Recent studies suggest that the impact of the 2023 strong El Niño event on TC activities in the WNP was weaker than expected due to the interference of other climate modes6,28. Zhao et al.6 investigated the decline in TCGF during the entire typhoon season (June–November) and attributed it to the persistently warm TNA and negative phase of Pacific Meridional Mode. However, observational analyses indicate that the main decline of TC activities occurred in autumn (Fig. 1), when the TNA warming and the Pacific Meridional Mode became weaker compared to JJA (Fig. 2). Moreover, although Song et al.28 proposed that the strong positive North Pacific mode (NPM) suppressed TC activities over the WNP in autumn, a similar NPM was observed in 2023 summer when WNP TC activities were active. Therefore, the mechanisms behind the record-low WNP TCGF in autumn 2023 need to be further examined. Here, based on both our observational analysis and model experiments, we demonstrate that the Indian Ocean played a dominant role in suppressing TC activities over the WNP in SON 2023, with its influence surpassing that of the tropical Pacific and the North Atlantic during this period.

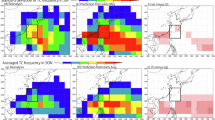

TC track (lines) and genesis density anomalies (shading) during June–August (JJA; a) and September–November (SON; b). Blue dots denote the genesis location of TCs. Black and red lines indicate TC tracks in JJA and SON, respectively. Red box (5°–25°N, 120°–165°E) represents the central WNP (CWNP), where a significant TC decline occurred during SON 2023. c, d Time series of TC genesis frequency (TCGF) anomalies in the CWNP (green bar), sea surface temperature (SST) index over the tropical North Atlantic (TNA; black line), dipole mode index (DMI; red line), and Niño 3.4 index (blue line) during JJA and SON. Green bars show TCGF anomalies for 1980–2022; red bars indicate 2023 values. e, f Anomalous dynamic genesis potential index (DGPI; shading) and horizontal wind at 850 hPa (vectors; m/s) in 2023. The wind anomaly less than 0.5 m/s is omitted. g Quantitative contributions to DGPI changes (relative to 1980–2022 climatology): relative DGPI change (DGPI’), sum of the relative changes in four dynamic factors (Sum’), including vertical wind shear (VWS’), meridional gradient of zonal wind at 500 hPa (dUdY’), 500-hPa vertical velocity (W’), and 850-hPa absolute vorticity (Vort’). Blue and red bars represent JJA and SON values, respectively.

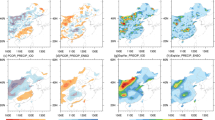

a–c The anomalous SST (shading; unit: °C) and horizontal wind (vector; unit: m/s) at 850 hPa from JJA to SON in 2023. d–f The anomalous velocity potential (contours; unit: m2/s) at 200 hPa and precipitation (shading; unit: mm). Brown and blue contours indicate high-level convergence and divergence, respectively. Thick brown (blue) contours represent 2 × 106 (−2 × 106) m2/s. Contour interval is 1 × 106 (−1 × 106) m2/s. The wind anomaly of less than 1 m/s is omitted. The red box indicates the main region of TC decline in SON 2023.

Results

Seasonal contrast of TC activities over the WNP in 2023

The WNP TCGF in 2023 exhibited distinct seasonal characteristics, with the most dramatic reduction occurring in SON and negligible changes in JJA (Fig. 1). During JJA, TC genesis locations concentrated within 10°–25°N, leading to positive genesis density anomalies in the region (Fig. 1a). During SON, the TC formation locations were far apart (Fig. 1b), resulting in pronounced negative TC genesis density anomalies over the WNP during SON, particularly in the region of 5°–25°N and 120°–165°E (hereafter referred to as central-western North Pacific, CWNP; Fig. 1b). As a result, TCGF over the CWNP in SON reached its lowest value (Fig. 1d). Overall, TC activities over the CWNP displayed prominent contrasting seasonal changes, showing slightly increased TCGF in JJA and a sharp decrease in SON (Fig. 1c, d).

TC genesis anomalies are closely linked to variations in large-scale environmental conditions29. While stronger vertical wind shear typically hinders TC formation, boreal summer and autumn in 2023 were characterized by enhanced and weakened vertical wind shear, respectively, contrasting with the slightly increased and then sharply reduced TCGF observed in these seasons. On the other hand, the ascending motion anomalies, enhanced mid-tropospheric moisture, and the anomalous low-level cyclonic circulation overall promoted TC genesis in JJA, whereas the opposite anomalies occurred in SON, effectively suppressing TC genesis in the region (Fig. S1).

Relative importance of these factors can be partially quantified using the dynamic genesis potential index (DGPI)30,31, which collectively represents the effects of large-scale circulation and moisture supply on TC genesis (see “Methods”). Distinct patterns emerge between JJA and SON (Fig. 1e, f), in agreement with the contrasting TCGF changes over the CWNP. In JJA, the distribution of the DGPI shows overall positive anomalies in the CWNP, coinciding with the observed increase in TCGF. By contrast, SON exhibits coherent negative DGPI, suggesting unfavorable conditions for TC development. Among the four factors consisting of the DGPI, negative vertical motion anomalies emerge as the dominant contributor to the decline of TC genesis in the CWNP during SON (Fig. 1g).

Relative roles of the three tropical oceans from observation analysis

To understand the mechanisms driving these contrasting seasonal changes, we examined the roles of concurrent strong climate modes across three tropical oceans in 2023. These included a strong El Niño ranked as the fourth strongest event since 1980, the second strongest pIOD in the 21st century, and unprecedented TNA warming in recent decades (Fig. 2).

Although a strong El Niño commonly dominates WNP TC activities, its influence in 2023 showed unique characteristics. In particular, the TCGF over the WNP during SON was unusually low—only 44% of other strong El Niño events (four TCs in 2023 versus nine TCs in other strong El Niño autumns). Typically, a strong El Niño corresponds to weakened Pacific Walker circulation and eastward shift of its ascending branch, resulting in anomalous low-level divergence over the western tropical Pacific and convergence over the eastern Pacific. Strong westerly wind anomalies usually prevail along the equatorial western-central Pacific, favoring TC development on their northern flank (Fig. S2). Consequently, the mean TC genesis location tends to shift eastward (Fig. S2a–c)15,19. However, these circulation patterns were substantially weaker in 2023 (Fig. 3b, c). Based on a Walker circulation index, the strength of Walker circulation anomalies in 2023 was only 16%–32% of those observed during the other strong El Niño events (Fig. 3b, c). Consequently, the westerly wind anomalies in 2023 were notably weaker than those observed during the strong El Niño (Figs. 2b and 4a), unfavoring TCs’ development over the CWNP, which contrasts with the conditions during other strong El Niño events (Fig. S2).

a Percentiles of SST anomalies in SON 2023 relative to autumn seasons of 1980–2023 (shading; unit: %). Gray contours represent the 99th percentile. b Composited velocity potential (contours) and geopotential height anomalies (shading; unit: m) at 200 hPa during SON for historical strong El Niño years (1982, 1997, 2015). c Same as (b), but for 2023. Brown and blue contours indicate high-level convergence and divergence, respectively. Thick brown (blue) contours represent 2 × 106 (−2 × 106) m2/s. Contour interval is 1 × 106 (−1 × 106) m2/s.

a Scatter plot of observed Pacific SST anomalies averaged over the tropical Pacific (160°E–80°W, 10°S–10°N) and 850-hPa zonal wind anomalies averaged over 140°E–140°W, 0°–10°N. b Simulated response of 850-hPa zonal wind anomalies to SST forcing in three tropical oceans, the Pacific, the Indian Ocean and the Atlantic experiments, respectively. Results from SST forcing experiments for: c Tropical Pacific Ocean (blue shading in Fig. S4); d Tropical Indian Ocean (green shading in Fig. S4). e Results from tropical Atlantic heat source anomaly experiment (shading in Fig. S6a). Vector and shading represent the anomalous 850-hPa horizontal wind (unit: m/s) and precipitation (unit: mm), respectively. Both are statistically significant at the 95% confidence level based on Student’s t-test. Brown and blue contours indicate high-level convergence and divergence, respectively. Thick brown (blue) contours represent 2 × 106 (−2 × 106) m2/s. Contour interval is 1 × 106 (−1 × 106) m2/s. The wind anomaly of less than 1 m/s is omitted.

SSTAs during 2023 SON in the TNA and western Indian Ocean ranked above the 99th percentile since 1980 (Fig. 3a), suggesting this warming was unprecedented in recent decades. The tropical Atlantic and Indian Ocean can modulate both the development of El Niño32 and the Walker circulation33,34,35 through interbasin interaction. Recent studies suggest that the warming over these two tropical Oceans can modify the large-scale circulation patterns typically associated with El Niño events36,37,38. Therefore, these warm tropical Oceans likely modulated the TC activities over the WNP during autumn 2023.

The TNA experienced significant warming in the summer and autumn of 2023 (Fig. 2a, b). The SSTA patterns were similar in these two seasons, but with overall weaker warming and a northward-shifted warming center during SON (Fig. 2a–c). The TNA warming pattern in autumn may favor negative precipitation anomalies across the equatorial Atlantic by weakening the Atlantic Hadley circulation (Figs. 2d–f and S3). As shown below, the equatorial drying anomalies can also be partly attributed to the tropical Pacific SSTAs (Fig. S5d). Previous studies suggest that negative rainfall anomalies in the equatorial Atlantic tend to partly offset the remote influences of the TNA warming on the tropical Pacific atmospheric circulation39. Consequently, the overall influence of the tropical Atlantic on the tropical Pacific atmospheric circulation may be weaker during SON.

Meanwhile, a strong pIOD event emerged in 2023, which ranked as the second strongest in the 21st century27. The anomalous zonal SST gradient associated with the strong pIOD induces pronounced easterly wind anomalies over the tropical Indian Ocean primarily during SON (Fig. 2b), resulting in anomalous low-level convergence extending from Africa to the western Indian Ocean, along with divergence anomalies that strengthened and expanded eastward to the WNP (100°–140°E; Fig. 2d, e). These changes corresponded to descending anomalies over the Indo-western Pacific region, providing unfavorable conditions for TCGF over the CWNP. Moreover, the western Indian Ocean SST during SON 2023 was the warmest in recent decades (Fig. 3a), inducing a strong zonal circulation change across the tropical Indian Ocean, and likely exerting stronger climate effects than other pIOD events.

These observational analyses suggest that while the equatorial Pacific westerly anomalies related to El Niño were unexpectedly weak, the strong pIOD event likely played a more prominent role in modulating WNP TCGF in 2023, with the tropical Atlantic SSTAs possibly exerting a limited influence in autumn. Next, we conducted a suite of sensitivity experiments using an Atmospheric General Circulation Model (AGCM) to quantify the contributions of the three tropical oceans to changes in TC activities over the CWNP in 2023.

Relative roles of the three tropical oceans from atmospheric model experiments

We first conducted an experiment incorporating SSTAs from June to December 2023 for all three tropical oceans in the model (Fig. S4). Subsequently, three AGCM experiments were conducted by excluding SSTAs from the tropical Indian Ocean, the tropical Atlantic Ocean, and both tropical oceans (details in “Methods” section). These simulations allow us to isolate and compare the roles of SSTAs in each basin in driving atmospheric changes over the WNP and identify the key region and physical processes influencing the WNP TCGF during SON (Fig. 4b–d). Model results show that the warming over the tropical Indian Ocean and Atlantic in 2023 can counteract the atmospheric response to El Niño over the tropical Pacific (Fig. 4b), particularly the equatorial westerly wind anomalies, consistent with previous studies36,37,38.

The Pacific-only experiment revealed that tropical Pacific warm SSTAs alone generated equatorial westerly wind anomalies and enhanced convection activities in the central equatorial Pacific (Fig. 4c), suggesting an eastward shift of the Walker circulation, consistent with typical El Niño patterns. In the western tropical Pacific, equatorial westerly anomalies correspond to anomalous positive vorticity to the north over the WNP, inducing enhanced rainfall in the region. This change is opposite to the descending motion anomalies observed in 2023, and thereby not contributing to the suppressed TCGF in the region.

In contrast, the Indian Ocean significantly contributed to subsidence anomalies over the WNP. The Indian Ocean experiment simulated a prominent zonal contrast in rainfall changes as well as pronounced easterly wind anomalies over the tropical Indian Ocean, driven by the strong pIOD SSTAs. The easterly anomalies extend to the western tropical Pacific, generating anticyclonic wind anomalies over the WNP (Fig. 4d), opposite to those induced by the Pacific SST changes. Consequently, anomalous subsidence and reduced rainfall occur over the WNP, creating unfavorable conditions for TC genesis.

The Atlantic warming also drives easterly anomalies over the Indo-western Pacific and reduced rainfall over the WNP in the model (Fig. S5a), consistent with previous findings40. However, these remote influences of Atlantic SSTAs primarily originate from the substantial rainfall changes over the Atlantic Ocean, yet the simulated rainfall anomalies in the Atlantic experiment exhibit evident differences from observations (Fig. S5b): While model simulated large-scale positive precipitation anomalies over the equatorial Atlantic with limited negative anomalies near eastern coast of America, observations showed pronounced negative precipitation anomalies in the equatorial North Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico during SON 2023 (Fig. 2e). This model bias is likely due to the overestimation of oceanic forcing on overlying atmosphere41.

Previous studies have shown that the dry anomalies over the equatorial Atlantic may counteract the effect of TNA warming-induced positive rainfall changes on Pacific winds39, leading to an overall weak impact on tropical Pacific circulation changes. These negative rainfall anomalies were partially driven by Pacific El Niño forcing (Fig. S5d). Additionally, the enhanced rainfall over the TNA region due to the local SST warming during SON 2023 may also contribute to the equatorial Atlantic drying anomalies through changes in the local Hadley circulation. However, it is worth noting that the TNA warming and equatorial Atlantic drying have not always occurred simultaneously in the past.

To more realistically represent the role of the tropical Atlantic in affecting Pacific circulation, we conducted an additional AGCM experiment by directly incorporating 2023 Atlantic heating anomalies from observations (Fig. S6; see “Methods”). There are negative heating anomalies over the equatorial Atlantic and positive heating anomalies over the northwest Atlantic in SON of 2023 (Fig. S6a). The experiment shows that these rainfall changes induce strong easterly wind anomalies over the equatorial eastern Pacific during SON, likely driven by the negative heating anomalies over the tropical Atlantic, which may hinder El Niño’s effect by offsetting the Pacific westerly anomalies (Fig. S5c). Moreover, in this heating anomalies experiment, the Atlantic exerts a weak direct influence on circulation anomalies over the western tropical Pacific during SON, suggesting a limited direct impact on WNP TC activities in SON 2023 (Fig. 4e).

Hence, these model results demonstrate that the decline in TCGF during SON 2023 primarily resulted from a combination of a strong pIOD influence and weakened El Niño-induced westerly anomalies. Although the TNA was extremely warm during autumn 2023, negative heating anomalies observed over the equatorial Atlantic played an opposite role and resulted in an overall negligible direct impact of the tropical Atlantic on TC genesis over the WNP. However, it may affect TC activities indirectly by suppressing atmospheric circulation anomalies associated with El Niño, through inducing easterly wind anomalies over the eastern tropical Pacific.

Discussion

Through observational analyses and model experiments, we examined the causes of the pronounced decline in TCGF over the WNP in 2023, particularly during the autumn season. Our findings indicate that the 2023 El Niño event exerted a significantly weaker influence compared to previous strong El Niño events, which is related to the muted atmospheric circulation response despite the prominent tropical Pacific warming resulting from ocean dynamics, as noted in a recent study37,38.

Meanwhile, despite the unprecedented warming of the TNA, its direct impact on WNP TC activities during September–November (SON) remained minimal due to offsetting effects from negative precipitation anomalies in the equatorial Atlantic. On the other hand, the tropical Atlantic Ocean likely suppressed the westerly wind anomalies over the eastern tropical Pacific related to the 2023 El Niño event, and thereby reduced El Niño’s effect on WNP TCs. In contrast, the strong pIOD played a pivotal role in suppressing TC formation by inducing easterly wind anomalies over the western equatorial Pacific and descending motion anomalies over the WNP, effectively reducing the TCGF (Fig. 5).

Blue arrows represent easterly wind related to the tropical Atlantic. Golden arrows represent easterly wind related to the Indian Ocean. Green and brown shading indicates positive and negative precipitation anomalies, respectively. Red and blue shading, respectively, indicates warm and cool SST anomalies.

Our findings highlight the distinct roles of the three tropical ocean basins in influencing WNP TC activities. Typically, the impacts of both ENSO and IOD are primarily associated with a zonal shift in the primary TC genesis location over the WNP (Fig. S7a, b), while the TNA warming predominantly suppresses TC activities over the eastern WNP (5°–30°N and 155°–180°E) (Fig. S7c). The opposite correlation between IOD and TCGF in the western and eastern WNP explains its overall weak association with TC activities when considering the region as a whole.

As the reduction in TC genesis during SON of 2023 primarily occurred over the CWNP, the tropical Indo-Pacific climate variability likely exerts a more dominant influence on the CWNP TC activity compared to the remote TNA forcing. Moreover, the similar impacts of ENSO and IOD partly arise from their close interconnection. Employing a partial correlation technique to exclude ENSO’s influence reveals that the IOD-TCGF relationship shows a significantly negative correlation over the main TC decline region (Fig. S7e), suggesting the independence of IOD’s influence on the CWNP TC genesis. After removing the IOD effect, the ENSO-TCGF correlation retains a zonal dipole pattern (Fig. S7d).

IOD and ENSO exhibit a strong positive correlation, with strong pIOD events typically in concurrence with El Niño, as evidenced in 1982, 1997, 2006, and 2015. The strongest pIOD event without El Niño conditions appeared in 2019. During this period, the warm central-western Pacific induced a cyclonic circulation in the WNP through the Gill response mechanism42, creating favorable conditions for TC genesis. The above evidence shows that the Pacific’s dominant influence had generally masked the pIOD’s effects over recent decades. In 2023, although the pIOD event was not the strongest in historical records, its concurrent occurrence with record-breaking Atlantic warming created a unique scenario that significantly modulated Pacific climate effects38 and unveiled its independence from ENSO.

The enhanced influence of the IOD and its independence from ENSO in 2023 may also be partially linked to the long-term SST trend pattern. Over recent decades, anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions have driven a significant increase in global mean SST. Notably, the warming trend in the tropical Indian Ocean has been much stronger compared to the equatorial Pacific Ocean43. This interbasin warming contrast is crucial, as local rainfall changes exhibit a nonlinear dependence on SST. The higher mean-state SST in the tropical Indian Ocean more effectively amplifies the influence of local SST variations on rainfall anomalies44,45,46, which in turn influence other regions through exciting atmospheric teleconnections43. As a result, the interbasin warming contrast across the tropical Indo-Pacific region has likely led to a more pronounced impact of the IOD on WNP TC activities.

On the other hand, changes in the relative importance of ENSO and IOD in modulating WNP TC activities may also be influenced by natural climate variability. For instance, Atlantic multidecadal variability can affect the ENSO-IOD connections, potentially altering their individual roles in driving tropical Indo-Pacific atmospheric variability and subsequently TC genesis. The underlying mechanisms causing the recent strengthening of IOD’s active influence warrant further investigation. Nonetheless, the growing significance of the IOD’s impact on WNP TCs highlights the need to incorporate this factor into future TC prediction models, which could substantially enhance prediction accuracy and reliability.

Methods

Observational data

Monthly atmospheric data with a horizontal resolution of 1° × 1° were downloaded from the official website of the fifth-generation European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts Reanalysis (ERA5)47,48, including horizontal wind, relative humidity, vertical velocity, geopotential height, temperature, and total precipitation. The anomalies of atmospheric and oceanic variables in this study were derived by removing the climatological mean (average during the period of 1980 to 2023) and long-term linear trend from the original data. The UK Met Office’s Hadley Centre Sea Ice and Sea Surface Temperature (HadISST) dataset49 was used to analyze the SST variation and its relationship with large-scale atmospheric circulation.

The TC activity

The best-track TC dataset from the International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship50,51 (IBTrACS; Version v04r01) was used in this study. From this multi-agency dataset, TC data from the JTWC were utilized. TCs with a 1-min maximum sustained wind above 34 knots (1 knot = 0.51 m/s) and formed over the WNP (bounded by 5°–30°N, 105°–180°E) since 1980 were considered in this study. The TC genesis location was defined when its sustained wind speed first exceeded 34 knots. The genesis density of TCs over the WNP was interpolated to a horizontal resolution of 5° × 5° and smoothed using the following method: D(x, y) = (D(x, y) + D(x−1, y) + D(x + 1, y) + D(x, y + 1) + D(x, y−1) + D(x−1, y−1) + D(x−1, y + 1) + D(x + 1, y−1) + D(x + 1, y + 1))/9, where x and y represent longitude and latitude, respectively.

Climate indices

The tropical SST indices are defined as follows: the TNA index is the normalized SST anomalies averaged over the TNA (0°–20°N, 10°–60°W). Niño 3.4 index is the normalized SST anomalies averaged over the equatorial Pacific (5°S–5°N, 120°–170°W), with ENSO events identified when this index exceeds one standard deviation. Dipole mode index (DMI) is defined as the difference in averaged SST anomalies between the western Indian Ocean (10°S–10°N, 50°–70°E) and the southeastern Indian Ocean (10°S–0°, 90°–110°E), following Saji et al.24 Following Wang et al.52, the Walker circulation index was defined as the difference in 500-hPa vertical velocity between two regions (5°S–5°N, 160°–120°W and 5°S–5°N, 120°–160°E).

DGPI

According to Murakami and Wang31, the DGPI is defined by the following equation:

where \({V}_{s}\) is the vertical wind shear between 200 and 850 hPa, \(\frac{d{u}_{500}}{{dy}}\) is the meridional shear vorticity of zonal wind at 500 hPa, \({\omega }_{500}\) indicates the vertical velocity at 500 hPa and \({\zeta }_{a850}\) represents the absolute vorticity at 850 hPa.

Here, we use the abbreviations of \({\rm{VWS}}\), \({\rm{dUdY}}\), \({\rm{W}}\), and \({\rm{Vort}}\) to represent the four terms in the above equation. Following Murakami and Wang31 and Huang et al.53, the equation of DGPI can be linearized as:

where the symbols of bar and delta represent the climatological mean and anomaly, respectively. Similarly, we define the relative change of DGPI as \({{DGPI}}^{{\prime} }=\frac{\Delta \text{DGPI}}{\overline{{DGPI}}}\), and Eq. (2) can be simplified as:

where the \({{VWS}}^{{\prime} }\), \({{dUdY}}^{{\prime} }\), \({W}^{{\prime} }\) and \({{Vort}}^{{\prime} }\) represent the relative changes of the four terms in Eq. (1), respectively. \({{Sum}}^{{\prime} }\) is the sum of the relative changes of the four terms.

AGCM experiments design

To evaluate the individual effects of tropical ocean warming in 2023, we performed four SST experiments using the Community Atmosphere Model version 5.0 (CAM5)54. CAM5 is the atmospheric component of the National Center for Atmospheric Research Community Earth System Model, which has a horizontal resolution of 1.25° × 0.9° and 30 vertical levels. We used the observational SST anomaly during June to December 2023 over the three tropical oceans (including the tropical Pacific, Atlantic, and Indian Ocean; Fig. S4) to drive the model. To ensure the stability of the model, half of the anomalous SST in June 2023 was added to the forcing SST field in May.

Besides the control run forced with climatological SST, we designed four sets of AGCM experiments with SST anomalies from the following regions: (1) all three tropical oceans (Pacific, Atlantic, Indian Ocean), (2) the tropical Indian Ocean and Pacific, (3) the tropical Atlantic and Pacific and (4) the tropical Pacific only. Through this experimental design, the individual contribution of the Atlantic and Indian Ocean can be isolated by comparing the three-ocean experiment with two-ocean experiments, while the Pacific’s impact is determined by comparing the Pacific-only experiment with the control run. Outside forced oceans, SST was set to the monthly climatology. Each experiment was integrated for 50 years, and the first 6 years were discarded, considering that it takes a few years to reach the model equilibrium state, yielding 44 years for analysis. The same SST forcing field was repeated in each simulated year. Each year can be treated as an independent realization, giving us an effective ensemble of 44 members. Thus, the ensemble mean represents the atmospheric response to the specified SST anomalies.

Furthermore, we conducted a separate experiment to investigate the impact of heat source anomalies over the tropical Atlantic by using the observational apparent heat source (Q1) during June–November 2023. This heat source experiment used 2.5° × 1.9° horizontal resolution with 30 vertical levels, incorporating heating rate (Q1/\({C}_{p}\)) anomalies from 1000 to 10 hPa (Fig. S6). Similarly, half magnitude of heating rate anomalies in June 2023 and December 2023 was applied in May and December in the first year for a smooth transition. The model was integrated for 30 years, with the first 6 years discarded as spin-up.

According to Yanai et al.55, the apparent heat source Q1 is defined by the following equation:

Where \(\theta\) is the potential temperature, \(V\) is the horizontal wind, \(\omega\) is the vertical velocity, \(p\) is the pressure, \({p}_{0}\) = 1000hPa, \({C}_{p}\) is the specific heat at a constant pressure of dry air, R is the gas constant, \(\kappa =R/{C}_{p}\), \(\nabla\) is the isobaric gradient operator and \(t\) is time.

Data availability

The authors acknowledge the following data providers: IBTrACS (https://doi.org/10.25921/82ty-9e16), (https:/www.ncei.noaa.gov/products/international-best-track-archive). ERA5 (https://doi.org/10.24381/cds.6860a573) and (https://doi.org/10.24381/cds.f17050d7), (https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/cdsapp#!/dataset/reanalysis-era5-pressure-levels?tab=overview). HadISST (https:/www.metoffice.gov.uk/hadobs/hadisst).

Code availability

The codes used for data analysis are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Zhou, X. & Lu, R. Interannual variability of the tropical cyclone landfall frequency over the southern and northern regions of East Asia in autumn. J. Clim. 32, 8677–8686 (2019).

Choi, Y., Ha, K.-J. & Jin, F.-F. Seasonality and El Niño diversity in the relationship between ENSO and Western North Pacific Tropical Cyclone Activity. J. Clim. 32, 8021–8045 (2019).

Singh, V. K., Kim, H.-J. & Moon, I.-J. Mechanism driving stronger tropical cyclones in cooler autumn than the hottest summer. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci 8, 132 (2025).

Shan, K., Lin, Y., Chu, P.-S., Yu, X. & Song, F. Seasonal advance of intense tropical cyclones in a warming climate. Nature 623, 83–89 (2023).

Basconcillo, J. & Moon, I.-J. Increasing activity of tropical cyclones in East Asia during the mature boreal autumn linked to long-term climate variability. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 5, 4 (2022).

Zhao, J. et al. Lapsed El Niño impact on Atlantic and Northwest Pacific tropical cyclone activity in 2023. Nat. Commun. 15, 6706 (2024).

Du, Y., Yang, L. & Xie, S.-P. Tropical Indian Ocean influence on Northwest Pacific Tropical cyclones in summer following strong El Niño. J. Clim. 24, 315–322 (2011).

Zhan, R., Wang, Y. & Wu, C.-C. Impact of SSTA in the East Indian Ocean on the frequency of Northwest Pacific tropical cyclones: a regional atmospheric model study. J. Clim. 24, 6227–6242 (2011).

Zhan, R., Wang, Y. & Lei, X. Contributions of ENSO and East Indian Ocean SSTA to the interannual variability of Northwest Pacific tropical cyclone frequency. J. Clim. 24, 509–521 (2011).

Li, R. C. Y. & Zhou, W. Interdecadal change in South China Sea tropical cyclone frequency in association with zonal sea surface temperature gradient. J. Clim. 27, 5468–5480 (2014).

Yu, J., Li, T., Tan, Z. & Zhu, Z. Effects of tropical North Atlantic SST on tropical cyclone genesis in the western North Pacific. Clim. Dyn. 46, 865–877 (2016).

Luo, X. et al. China coasts facing more tropical cyclone risks during the second decaying summer of double-year La Niña events. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 7, 198 (2024).

Zhang, W. et al. Dominant role of Atlantic multidecadal oscillation in the recent decadal changes in Western North Pacific tropical cyclone activity. Geophys. Res. Lett. 45, 354–362 (2017).

Zhang, W. et al. Modulation of western North Pacific tropical cyclone activity by the Atlantic Meridional Mode. Clim. Dyn. 48, 631–647 (2017).

Chan, J. C. L. Tropical cyclone activity over the Western North Pacific associated with El Niño and La Niña events. J. Clim. 13, 2960–2972 (2000).

Patricola, C. M., Camargo, S. J., Klotzbach, P. J., Saravanan, R. & Chang, P. The influence of ENSO flavors on Western North Pacific tropical cyclone activity. J. Clim. 31, 5395–5416 (2018).

Camargo, S. J., Emanuel, K. A. & Sobel, A. H. Use of a genesis potential index to diagnose ENSO effects on tropical cyclone genesis. J. Clim. 20, 4819–4834 (2007).

Li, S., Mei, W. & Xie, S.-P. Effects of tropical sea surface temperature variability on Northern Hemisphere tropical cyclone genesis. J. Clim. 35, 4719–4739 (2022).

Wang, B. & Chan, J. C. L. How strong ENSO events affect tropical storm activity over the Western North Pacific. J. Clim. 15, 1643–1658 (2002).

Wang, G., Su, J., Ding, Y. & Chen, D. Tropical cyclone genesis over the south China sea. J. Mar. Syst. 68, 318–326 (2007).

Wang, X., Zhou, W., Li, C. & Wang, D. Comparison of the impact of two types of El Niño on tropical cyclone genesis over the South China Sea. Int. J. Climatol. 34, 2651–2660 (2014).

Gao, C., Zhou, L., Wang, C., Lin, I.-I. & Murtugudde, R. Unexpected limitation of tropical cyclone genesis by subsurface tropical central-north Pacific during El Niño. Nat. Commun. 13, 7746 (2022).

Wang, C., Wu, K., Wu, L., Zhao, H. & Cao, J. What caused the unprecedented absence of Western North Pacific tropical cyclones in July 2020?. Geophys. Res. Lett 48, e2020GL092282 (2021).

Saji, N. H., Goswami, B. N., Vinayachandran, P. N. & Yamagata, T. A dipole mode in the tropical Indian Ocean. Nature 401, 360–363 (1999).

Cai, W., Van Rensch, P., Cowan, T. & Hendon, H. H. Teleconnection pathways of ENSO and the IOD and the mechanisms for impacts on Australian Rainfall. J. Clim. 24, 3910–3923 (2011).

Saji, N. & Yamagata, T. Possible impacts of Indian Ocean Dipole mode events on global climate. Clim. Res. 25, 151–169 (2003).

Blunden, J. & Boyer, T. State of the climate in 2023. Bull. Am. Meteor. Soc. 105, S1–S484 (2024).

Song, J., Klotzbach, P. J., Wei, N. & Duan, Y. What caused the record-low frequency of western North Pacific tropical cyclones in autumn 2023?. Geosci. Lett. 11, 34 (2024).

Gray, W. M. The formation of tropical cyclones. Meteor. Atmos. Phys. 67, 37–69 (1998).

Wang, B. & Murakami, H. Dynamic genesis potential index for diagnosing present-day and future global tropical cyclone genesis. Environ. Res. Lett. 15, 114008 (2020).

Murakami, H. & Wang, B. Patterns and frequency of projected future tropical cyclone genesis are governed by dynamic effects. Commun. Earth Environ. 3, 77 (2022).

Fan, H., Wang, C., Yang, S. & Zhang, G. Coupling is key for the tropical Indian and Atlantic oceans to boost super El Niño. Sci. Adv. 10, eadp2281 (2024).

Wang, C. An overlooked feature of tropical climate: Inter-Pacific-Atlantic variability. Geophys. Res. Lett. 33, GL026324 (2006).

Ding, H., Keenlyside, N. S. & Latif, M. Impact of the Equatorial Atlantic on the El Niño Southern Oscillation. Clim. Dyn. 38, 1965–1972 (2012).

Izumo, T. et al. Influence of the state of the Indian Ocean Dipole on the following year’s El Niño. Nat. Geosci. 3, 168–172 (2010).

Hu, R. et al. Predicting the 2023/24 El Niño from a multi-scale and global perspective. Commun. Earth Environ. 5, 675 (2024).

Peng, Q. Strong 2023-2024 El Niño generated by ocean dynamics. Nat. Geosci 18, 471–478 (2025).

Zhang, L. et al. The 2023/24 El Niño event exhibited unusually weak extratropical teleconnections. Commun. Earth Environ. 6, 595 (2025).

Jiang, L. & Li, T. Impacts of tropical North Atlantic and Equatorial Atlantic SST anomalies on ENSO. J. Clim. 34, 5635–5655 (2021).

Li, X., Xie, S.-P., Gille, S. T. & Yoo, C. Atlantic-induced pan-tropical climate change over the past three decades. Nat. Clim. Change 6, 275–279 (2016).

Trenberth, K. E. & Shea, D. J. Relationships between precipitation and surface temperature. Geophys. Res. Lett. 32, 2005GL022760 (2005).

Zhang, L., Han, W. & Hu, Z.-Z. Interbasin and multiple-time-scale interactions in generating the 2019 extreme Indian Ocean Dipole. J. Clim 34, 4553–4566 (2021).

Zhang, L. et al. Indian Ocean warming trend reduces Pacific warming response to anthropogenic greenhouse gases: an interbasin thermostat mechanism. Geophys. Res. Lett. 46, 10882–10890 (2019).

Gadgil, S., Joseph, P. V. & Joshi, N. V. Ocean–atmosphere coupling over monsoon regions. Nature 312, 141–143 (1984).

Waliser, D. E. & Graham, N. E. Convective cloud systems and warm-pool sea surface temperatures: coupled interactions and self-regulation. J. Geophys. Res. 98, 12881–12893 (1993).

Johnson, N. C. & Xie, S.-P. Changes in the sea surface temperature threshold for tropical convection. Nat. Geosci. 3, 842–845 (2010).

Hersbach, H. et al. ERA5 monthly averaged data on pressure levels from 1940 to present. Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) Climate Data Store (CDS) (2023).

Hersbach, H. et al. ERA5 monthly averaged data on single levels from 1940 to present. Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) Climate Data Store (CDS) (2023).

Rayner, N. A. et al. Global analyses of sea surface temperature, sea ice, and night marine air temperature since the late nineteenth century. J. Geophys. Res. 108, 2002JD002670 (2003).

Knapp, K. R., Kruk, M. C., Levinson, D. H., Diamond, H. J. & Neumann, C. J. The International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS): unifying tropical cyclone data. Bull. Am. Meteor. Soc. 91, 363–376 (2010).

Gahtan, J. et al. International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS) Project, Version 4r01. NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information (2024).

Wang, C. Atmospheric circulation cells associated with the El Niño–Southern oscillation. J. Clim. 15, 399–419 (2002).

Huang, X. et al. Understanding uncertainties in projections of western North Pacific tropical cyclogenesis. Environ. Res. Lett. 18, 114037 (2023).

Neale, R. B. et al. Description of the NCAR Community Atmosphere Model (CAM 5.0) (2012).

Yanai, M., Li, C. & Song, Z. Seasonal heating of the Tibetan Plateau and its effects on the evolution of the Asian summer monsoon. J. Meteorol. Soc. Jpn. 70, 319–351 (1992).

Acknowledgements

This work is suppported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42376021), the National Key R&D Program of China: Young Scientist Program (2023YFC3108800), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (W2441014), the GuangDong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (2024B1515040024), the Development fund (SCSIO202203) and Special fund (SCSIO2023QY01) of South China Sea Institute of Oceanology of the Chinese Academy of Sciences. The numerical simulations are supported by the High-Performance Computing Division in the South China Sea Institute of Oceanology.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.Z. conceived the study. X.L. and L.Z. wrote the initial manuscript. X.L. conducted the data analyses and prepared the figures. X.L. and Y.Y.C. conducted the numerical experiments. All authors participated in the discussion of results, contributed to manuscript revision, and read and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Luo, X., Zhang, L., Chan, J.C.L. et al. Unusual role of positive Indian Ocean Dipole in the record-low tropical cyclone genesis over the Western North Pacific in 2023. npj Clim Atmos Sci 8, 322 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-01206-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-01206-6