Abstract

Arctic amplification (AA), the disproportionate Arctic warming versus hemispheric or global averages, impacts mid-latitude climate. Prior studies reported a wide range of AA ratios from 1.0 to 12.5, based on 20th-century observations or climate model hindcasts. This study investigates the variability of the AA ratio within a long-term transient simulation encompassing the past glacial-interglacial period. We find a strong link between the AA phenomenon and North Atlantic sea ice changes driven by ice-albedo feedback, yielding a stable AA ratio of 2.5 ± 0.8 throughout the last 21,000 years. The current observed AA ratio, slightly lower than 2.5, indicates the combined effect of sea ice melt-induced AA added to the greenhouse gas-induced global warming. We hypothesize that as Arctic sea ice rapidly diminishes, or even disappears, the sea ice-induced AA phenomenon will weaken substantially, reflected in the AA ratio approaching 1.0 within the next 1–2 centuries, even as global warming persists.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Arctic Amplification (AA), a prominent feature of modern climate change, exhibits a much faster near-surface warming rate at high-latitude compared to the Northern Hemisphere (NH) or global average over the past century. Observations and model simulations consistently show this trend1,2,3. While AA’s influence on mid-latitude weather and climate extremes is well-established4,5,6,7, its underlying dynamics remain complex and the relative importance of each mechanism is still being explored through both established frameworks and newer analytic formulations1,8,9. Traditionally, Arctic sea ice-albedo feedback has been considered the primary driver of AA10,11,12. However, recent studies suggest that remote processes, like atmospheric and oceanic heat transport, can influence AA on Earth-like13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20 and even ice-free planets21. Additionally, local processes such as increased water vapor and low-cloud cover can further warm the Arctic22,23. Moreover, the lapse-rate constraint, affecting heating profiles through local and remote (tropical) processes, is another potential mechanism intensifying near-surface AA24,25,26. In summary, the relative contributions of various feedback mechanisms of AA are still debated in the current scientific community1,8,9, and numerical simulations also have significant uncertainties due to the various representations of these feedbacks among climate models1,27,28.

The AA index, or more precisely the AA ratio, defined as the ratio of Arctic to NH or global surface temperature change, quantifies the magnitude of AA. In the observations, estimates of the AA ratio over the past century vary widely, ranging from 1.3 to 12.529,30,31,32. Davy et al.29 investigated multiple datasets, including observations and reanalysis data, and suggested an AA index of 2.5–8.0. Similar studies using weather station data yielded broader ranges of 1.3–2.030 and 2.0–12.531. A recent study by Rantanen et al.33, utilizing updated observational and reanalysis datasets (1979–2021) with improved Arctic spatial coverage, re-estimated the AA ratio at approximately 4. Another recent study by Zhou et al.34 indicates that after removing the natural internal variability of the climate system, such as Interdecadal Pacific Oscillation and an Arctic mode, from the observations, the anthropogenically forced AA ratio is approximately 3. All these observation-based AA studies are limited by the length of the observational data. Specifically, the AA index is sensitive to the chosen time period, the so-called temporal window. Shorter periods, such as 30 years or less, usually lead to a greater AA range. In addition, the value range of the AA index can become very large when the NH or globally averaged temperature trend in the time window is very small (i.e., the denominator is very small). At this point, the internal variability of the climate system can significantly alter, overwhelm, or even reverse the AA phenomenon. The AA index will then exhibit behavior similar to a random walk, appearing large but essentially indicating that AA is much smaller than the internal climate variability.

Modern climate models estimate the AA ratio within a range of 1.0–4.5, narrower but still significant compared to observational estimates. Dai et al.10 analyzed 38 models from the Coupled Model Inter-comparison Project Phase 5 (CMIP5) under the Representative Concentration Pathway 8.5 scenario and found an AA ratio of 1.2–3.3. They also highlighted the role of sea ice loss in AA and suggested it may weaken considerably with sea ice melt. Similarly, Barnes et al.32 using 27 CMIP5 models estimated an AA ratio of 1.0–2.0. Sensitivity experiments exploring CO2 doubling and quadrupling scenarios also reveal greater variation in the AA ratio. For instance, Stuecker et al.26 found an AA ratio of around 2.0 in a 4xCO2 simulation with the CESM model. Earlier studies using similar CO2 forcing configurations reported AA ratio ranges of 1.9–2.035, 1.2–2.436, and 1.5–4.537. It should be noted that climate models generally struggle to simulate Arctic sea ice sensitivity to global warming38. This inherent bias within the models leads to two consequences: a persistently large spread among models from CMIP3 to CMIP6, although this spread has noticeably decreased in CMIP638; and a multi-model average of simulated AA is often slightly smaller than observed values33. Paleoclimate modeling and proxy studies estimate a range of 1.0–6.0 for the AA ratio. Park et al.39 investigated mid-Holocene (MH) vs. pre-industrial (PI) simulations in 13 models from the Paleoclimate Modelling Inter-comparison Project, Phase 3 (PMIP3), finding an AA ratio range of 1.3–6.0. This exceeds the range of 1.5–2.2 reported in proxy studies40,41,42. Similarly, Masson-Delmotte et al.43 estimated an AA ratio of 1.0–2.9 for Last Glacial Maximum (LGM) to PI changes in 6 PMIP2 models, which is slightly lower than the median value of 3.6 derived from proxy studies by Miller et al.44. Both paleoclimate modeling and proxy reconstructions have inherent uncertainties. Paleoclimate models using MH-to-PI or LGM-to-PI simulations reflect slow climate adjustments over millennia, contrasting with the faster responses observed on centennial timescales. Proxy data uncertainties arise from their limited spatial coverage, which may not accurately represent either Arctic or NH average conditions.

In this study, we analyze AA evolution using the simulations from the project of Simulation of Transient Climate Evolution over the last 21,000 years (TraCE-21ka)45,46,47,48,49 (details in “Methods”). This long-term transient simulation offers two advantages: (1) Comprehensive spatial coverage: the data covers the entire Arctic and NH, ensuring robust spatial representation; and (2) Consistent temporal coverage: the data’s consistent temporal resolution enables the calculation of 100-year AA ratios spanning the entire past 21,000 years. These advantages can effectively address uncertainties in previous studies. We aim to reveal the diversity of AA ratios and its underlying physical processes from paleoclimate modeling point of view.

Results

The definition of the AA ratio or AA index used in this paper is the ratio of the surface air temperature (SAT) trend in the Arctic region (60–90° N) to the SAT trend in the NH within a specific 100-year time window. The reason we chose the NH average as the denominator, rather than the global average, stems from the consideration that in orbital-scale climate studies, many factors related to temperature changes often exhibit opposite trends between the Northern and Southern Hemispheres. Moreover, we also explore uncertainties in the AA index calculation, specifically regarding the Arctic region’s latitudinal extent and the temporal window for SAT trend analysis. To assess the sensitivity of the Arctic region definition, we tested the critical latitudes from 45° N to 70° N (Supplementary Fig. 5a–f). Results indicate that the AA index distribution is relatively insensitive to this parameter. However, the AA index is highly sensitive to the temporal window, varying significantly across 8-, 16-, 32-, 64-, 128-, and 100-year intervals (Supplementary Fig. 7a–f). Considering the balance between index stability and data processing efficiency, we adopt a 100-year window for this study. For detailed information on AA ratio/index calculation, statistical methods, and some schematic diagrams, please refer to the Methods and Supplementary Information sections.

Variability of AA ratio in the last 21,000 years

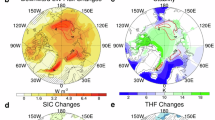

While directly observing AA, a prominent climate response in the NH high latitudes for the past century, is not easy, modeling results offer a clearer view of its behavior. The AA pattern for the period of 1901–2000 in 4 commonly-used datasets remains unclear due to limited data coverage in the early 20th century, particularly over the Arctic and oceans (Supplementary Fig. 1). However, multi-model simulations from the CMIP6 reveal a clear AA pattern for the 20th and 21st centuries (Fig. 1a, b). Interestingly, under even higher CO2 concentrations (1751 ppm to 2206 ppm), following the highest emission scenario SSP5-8.5 in extended CMIP6 projections (Fig. 1c), AA weakens significantly by 2151–2250. These modeling results suggest that the AA pattern might reflect the combined effects of global warming driven by anthropogenic forcing plus polar amplification acting as a form of internal natural variability. Thus, isolating the AA component as an independent climatic internal mode may be crucial for understanding future AA behavior. Paleoclimate modeling provides a better data foundation by excluding anthropogenic forcing and incorporating a wider range of natural climate forcings across long temporal scales.

a Ensemble mean in CMIP6 historical simulation (1901–2000). b Ensemble mean in CMIP6 under the SSP5-8.5 scenario (2001–2100). c Ensemble mean in CMIP6 under the extended SSP5-8.5 scenario (2151–2250). d A single 100-year sample for the Bølling-Allerød warming period in TraCE-21ka. White dots indicate regions with significant sea ice decline within the 100-year window (defined as a sea ice concentration difference of greater than 10% between the last and first 20 years). CO₂ changes over the corresponding period are plotted in the upper left corner of each panel.

In this context, paleoclimate modeling provides a better data foundation by excluding an- thropogenic forcing and incorporating a wider range of natural climate forcings across long temporal scales. Here, we investigate the variability of the AA ratio across the last 21,000 years using three datasets: TraCE-21ka (the past 20,000+ years), NOAA-NCEI/LMR (the past 2000+ years), and NOAA-CIRES/20CR (the past 100+ years) (Fig. 2). Each data point represents the AA ratio calculated within a 100-year window using Eq. 1 in the “Method” section. The reason for using paleoclimate simulations or reanalysis here is twofold: (1) Spatially, these datasets can provide complete Arctic coverage, whereas reliable observational data covering the Arctic typically spans no more than 50 years, and reconstructed proxy data faces even greater challenges in achieving spatial coverage of the Arctic, hemispheres, or the globe. (2) Temporally, these datasets can easily reach a 10-year resolution (a minimum temporal resolution enabling the analysis of AA trends within 100-year windows) and extend over several centuries, providing sufficient samples for addressing this issue, which is often unattainable with observational or reconstructed proxy data due to their limited temporal resolution. The TraCE-21ka outputs (Fig. 2a, navy blue, green, steel blue) exhibit a distinct pattern reflecting two climatic states. The first state (1654 samples, near the y-axis) represents periods of relative stability, with NH average temperature changes less than 0.2 °C/100a. This results in a small denominator in the AA ratio calculation, leading to high variability between −15 and +20. The second state (318 samples, 3 and 9 o’clock positions) encompasses periods with significant warming or cooling trends (>0.2 °C/100a), mostly during deglaciations. Here, the AA ratio stabilizes around 2.5 (see “Methods”, Supplementary Fig. 2). Similarly, the NOAA-CIRES/20CR value for the 20th century (2.43) aligns with this range (Fig. 2a, red cross). NOAA-NCEI/LMR data (Fig. 2a, orange dots) shows a wider range (0–5) due to the relatively stable NH temperatures (<0.4 °C/100a) during the last 2000 years, including both the Medieval Warm Period and the Little Ice Age. Notably, across all datasets, the majority of AA ratios cluster around 2.5 during both NH warming and cooling intervals (Fig. 2a).

a AA ratio (see “Methods”) and corresponding Northern Hemisphere (NH) 2 m air temperature trends in the last 21,000 years (TraCE-21ka, glacial = navy blue dots, deglaciation = green dots, and interglacial = steel blue dots), the last millennium (1–2000 CE, NOAA-NCEI/LMR, orange dots), the 20th century (NOAA-CIRES/20CR, red cross), and the 21st century (CMIP6 ensemble under SSP5-8.5, red square, multiplied by 10, approximately 0.7 °C/decade). The thick gray line represents the median AA ratio of 2.5. b Weighted frequency distribution of the AA ratio in TraCE-21ka (see “Methods”). The black line represents the sum of the glacial, deglaciation, and interglacial periods. c Zoomed-in view of (b) between −1 and 6 with a Gaussian fitting curve (red line). The red bar indicates the median of the Gaussian fit of 2.5. The gray shaded area represents the AA ratio spread accounting for 50% of its variance (25% percentile to 75% percentile).

We delve deeper into the uncertainty of AA ratios in the TraCE-21ka dataset by analyzing the weighted probability density functions (Fig. 2b, c). All 1972 AA ratio samples exhibit a Gaussian distribution centered around 2.5, with ±0.8 encompassing 50% of the total variance (from 25th to 75th percentiles). This narrow range of 2.5 ± 0.8 suggests that a robust AA phenomenon is an inherent mode of Earth’s fluctuating climate over the past 21,000 years. This implies that natural climate processes might play a more significant and persistent role in shaping AA compared to recent anthropogenic forcing.

Three AA modes

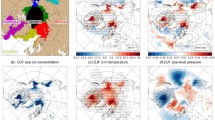

The distribution of AA ratios in Fig. 2a suggests distinct regimes. To explore these, we perform a composite analysis, grouping data points into three modes visualized in Fig. 3h. The Arctic Mode (AM, including AM+ and AM-) encompasses samples located at the 3 and 9 o’clock positions of the diamond shape scatters (Fig. 2a), representing intervals of significant warming or cooling in the Arctic (Fig. 3h, purple). The Warm-arctic-Cold-tropics Mode (WCM, including WCM+ and WCM-) groups points on the left and right wings of the 6 and 12 o’clock positions, respectively (Fig. 3h, green). The Cold-arctic-Warm-tropics Mode (CWM, including CWM+ and CWM-) mirrors the WCM modes on the y-axis (Fig. 3h, yellow). Positive and negative signs in the mode names, indicating the direction (warming or cooling) of NH average temperature change, are illustrated in Fig. 3g. The composite spatial patterns of SAT changes for each mode are shown in Fig. 3a–f. In the WCM+ mode, the warming in the Arctic is greater than the cooling in the Tropics, resulting in overall warming, while in the WCM- mode, the warming in the Arctic is lower than the cooling in the Tropics, leading to overall cooling (Fig. 3g). Similarly, in the CWM+ mode, the cooling in the Arctic is less than the warming in the Tropics, resulting in overall warming, while in the CWM- mode, the cooling in the Arctic exceeds the warming in the Tropics, causing overall cooling.

Composites of AM mode cases with NH temperature trends exceeding 0.2 °C/100a (a) or below −0.2 °C/100a (b). Composites of WCM mode cases with NH temperature trends of 0-to-0.2 °C/100a and AA ratio greater than 6 (c), or NH temperature trends of −0.2-to-0 °C/100a and AA ratio less than −4 (d). Composites of CWM mode cases with NH temperature trends of 0-to-0.2 °C/100a and AA ratio less than −4 (e), or NH temperature trends of −0.2-to-0 °C/100a and AA ratio greater than 6 (f). Red contours represent the NH average. Black dots indicate areas where trends pass the 95% significance test. Boxes to the right of the maps display zonal mean SAT trends. Vertical lines represent the NH average. Red horizontal lines denote the critical latitude in the simplified AA model assuming an AA ratio of 2.5 (see “Methods”). g Conceptual illustration of the three modes. h Corresponding regimes of the three modes in the diamond-shaped diagram as shown in Fig. 2.

The Arctic Mode (AM+ and AM-) stands out as the most representative one among the three AA modes, closely resembling the modern AA pattern. The 136 AM samples primarily occur during the last deglaciation (Fig. 3h, purple) and correspond to periods of abrupt climate change with NH average temperature changes exceeding ±0.2 °C within a century (Fig. 2). The composite Arctic Mode (Fig. 3a, b) reveals the most pronounced SAT changes at high latitudes, particularly around the North Atlantic, with minimal or negligible changes in the tropics. This highlights the dominant role of Arctic temperature variations in shaping NH average temperature changes during Arctic Mode events, with minimal tropical contributions (Fig. 3g). To further explore this pattern, we define a critical latitude separating strong high-latitude warming/cooling from weak tropical changes (Supplementary Fig. 3a). The likely critical latitude falls within the range of 37° N to 60° N (Supplementary Fig. 3a, from red line to blue line). The composite AM patterns (Fig. 3a, b) resemble conditions with a critical latitude near 37°N (Supplementary Fig. 3a, red line). This suggests that extensive sea ice cover during the last deglaciation (Supplementary Fig. 3a, red line) may have led to a more pronounced AA phenomenon with weaker tropical changes compared to the interglacial samples with reduced sea ice (Supplementary Fig. 3a, blue line). In summary, in the past 21,000 years, the Arctic Mode, characterized by distinct AA patterns during significant NH temperature shifts, primarily occurred during the last deglaciation (Fig. 2, green dots and lines) and some Holocene climate change events (Fig. 2, steel blue dots and lines), exhibiting a southward expansion of the Arctic warming/cooling pattern (Fig. 3a, b) particularly over North Atlantic and an AA ratio of 2.5 ± 0.8 (Fig. 2c).

The other two modes, WCM (WCM+ and WCM-, Fig. 3h, green) and CWM (CWM+ and CWM-, Fig. 3h, yellow), reflect periods of stable NH climate with minimal centennial temperature trends. These two modes can be considered atypical AA modes due to their exceptionally broad ranges of AA ratios. The underlying reason lies in the counterbalancing temperature changes between NH high and low latitudes (Fig. 3c, d for WCM; Fig. 3e, f for CWM), resulting in minimal NH temperature shifts, thus presenting the AA ratio like a wide-band noise.

Furthermore, we delve into the zonal structure of the three modes by performing a composite analysis of zonal mean temperature trends at various pressure levels (Fig. 4). The Arctic Mode (Fig. 4a, b) exhibits significant warming/cooling throughout the extratropics, extending from the surface to 500 hPa. Additionally, the tropics show notable warming/cooling in the upper troposphere (500–150 hPa), resembling the “tropical amplification” documented elsewhere50, albeit with a weaker amplitude compared to the Arctic surface changes. In contrast, the other two modes, WCM and CWM (Fig. 4c–f), lack statistically significant temperature trends in the troposphere, except for a slight near-surface warming/cooling at high latitudes with minimal statistical significance. Overall, the spatial maps (Fig. 3c–f) and cross-sections (Fig. 4c–f) of the WCM and CWM modes display statistically insignificant features, suggesting they can be interpreted as climatic noise rather than typical AA modes.

The figure layout follows the same structure as Fig. 3a–f, but displays zonally averaged temperature trends at multiple pressure levels. Black dots indicate areas where trends pass the 95% significance test.

The spatial pattern and vertical structure of the three modes indicate that the AA phenomenon, in nature, is closely linked to sea-ice-air coupling processes happening over the North Atlantic sector. The AM mode composite represents a typical changing climate (Fig. 3a, b) that some sea-ice-related large-scale low-frequency (close to or even longer than centennial timescale) forcing, such as the Atlantic Multi-decadal Oscillation (AMO) or the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation, trigger ice-albedo positive feedbacks, which further causes abundant sensible heat released from the upper ocean to the lower atmosphere. Figure 1d, as another example, gives a 100-year example in the Bølling-Allerød (BA) period (a warm interstadial that occurred near the end of the last glacial period, ~14000 years ago) showing that the fast warming (Fig. 1d, red shadings) area over the North Atlantic is essentially caused by the ocean’s heat release due to sea ice melting (Fig. 1d, white dots). The cases in the other 2 modes imply that the NH climate is overall stable with minor internal high-frequency climatic oscillation or disturbance, such as the Arctic Oscillation and/or the Pacific Decadal Oscillation, but without ice-albedo feedback triggered (Fig. 3c–f, no dots over North Atlantic or North Pacific). In the next section, we will discuss the contribution of sea-ice melt (or freeze) to AA’s formation.

Key sea-ice process in shaping AA

To investigate the physics underlying AA, we analyzed Arctic sea ice area and CO2 concentration variations within those abrupt climate change (ACC) snapshots, defined as 100-year periods with SAT trend exceeding ±0.5 °C/100a (Fig. 5a). Most ACC events occurred during the BA interstadial, aligning with the AM+ and AM- modes, while others fell within the Younger Dryas (YD) recovery, the 7.8 ka event, and other Holocene ACC periods (Fig. 5a, purple circles).

a NH (black) and Arctic (red) 2 m air temperature evolution over the past 21,000 years in TraCE-21ka. Purple circles highlight ACC samples with temperature trends exceeding ±0.5 °C/100a. b AA ratio and corresponding NH sea ice area trends. c AA ratio and corresponding NH CO2 concentration trends. Purple dots represent the same cases as purple circles in (a). Red crosses indicate the 20th century ensemble mean from CMIP6.

The AA index in relation to NH sea ice and CO2 trends (Fig. 5b, c) reveals a strong correlation between sea ice expansion/retreat and AA during ACC events (Fig. 5b, purple points at 3 and 9 o’clock positions). Conversely, the random distribution of purple points around the x-axis in Fig. 5c indicates that significant CO2 natural changes still cannot call for AA events, even in deglaciation years. These results suggest that rapid sea ice variations, rather than CO2 fluctuations, are the primary driver of AA.

Within these 100-year ACC samples, we examined the relationship between the AA index and Arctic sea ice (Fig. 5b) and CO2 (Fig. 5c). We found that during these ACC events, rapid changes in Arctic and NH temperatures occurred, with: (1) Arctic sea ice undergoing corresponding rapid expansion or retreat, coinciding with a stabilized AA index around 2.5 (Fig. 5b, purple points at 3 and 9 o’clock positions); (2) while CO2 exhibited a random walk pattern and showed no stable relationship with the AA index (Fig. 5c). It suggests that rapid sea ice variations, rather than CO2 fluctuations, are the primary driver of AA.

Centennial-scale sea ice fluctuations drive AA through a series of thermodynamic processes. During NH warming years, reduced sea ice exposes more low-albedo ocean, amplifying solar radiation absorption10,12. This leads to increased oceanic heat release into the lower atmosphere during autumn, delaying sea ice formation51,52. Consequently, thinner, more vulnerable ice forms, accelerating its melting in subsequent summers. This ice-albedo feedback rapidly amplifies surface temperatures in ice-retreat regions, creating the classic AA pattern (Fig. 1a, b, d). In the paleoclimate context, these processes can occur naturally due to low-frequency sea-ice-atmosphere interactions. Similarly, the current AA can be primarily attributed to sea ice loss in the North Atlantic and Barents/Kara Seas, rather than direct GHG impacts. Jenkins and Dai53 support this conclusion using a state-of-the-art climate model. Notably, a very weak AA signal is anticipated before sea ice onset or after complete melt, regardless of CO2 levels (Fig. 1c, Fig. 5c).

To discuss the diversity of AA patterns across past, present, and future climates, we go back to take a look at Fig. 1 again. The paleoclimate records exhibit NATURAL sea ice fluctuations without significant anthropogenic CO2 forcing. These fluctuations produced distinct AA, characterized by an AA index of approximately 2.5 ± 0.8 (Fig. 1d, Fig. 2c, Fig. 3a, b, Supplementary Fig. 3a). In contrast, over modern climate change years (Fig. 1a, b), anthropogenic CO2 has driven global warming, inducing subsequent sea ice loss and amplified Arctic warming. Thus, the observed warming pattern reflects a combination of CO2-induced global warming (Supplementary Fig. 3b, gray shading) and ice-induced AA pattern (Supplementary Fig. 3b, blue line). Mathematically speaking, the AA index in these periods will decrease to the range of 1–2.5 (Supplementary Fig. 3b), with true values of 2.36 and 1.76 for Fig. 1a and b, respectively.

Far-term future projections from CMIP6, specifically for the period 2151–2250, indicate a substantial weakening of AA, with an index of 1.14 (Fig. 1c). This reduction is attributed to the projected near-complete loss of summer sea ice, largely diminishing the ice-albedo feedback. Consequently, while anthropogenic GHGs continue to increase in the long-term future, the warming pattern becomes more globally uniform with just a minor land amplification signal (Fig. 1c). Under these conditions, a clear AA pattern is unlikely, and the AA index therefore is expected to approach 1 approximately.

Discussion

Our study reveals the diverse behavior of the AA index over the past 21,000 years in a transient simulation. The modeling results indicate that, from a paleoclimate perspective, the AA phenomenon is primarily linked to sea-ice-atmosphere coupling through the ice-albedo feedback mechanism, triggered by either natural climate variability (paleoclimate) or anthropogenic forcing (modern climate). In paleoclimate contexts, the AM mode exhibits a pronounced AA pattern with a robust and stable index/ratio of approximately 2.5 ± 0.8 during periods of rapid NH climate change, while the WCM and CWM modes display anomalous AA-like patterns with a highly variable index ranging from −15 to 20 during periods of relatively stable NH climate. In the present climate, the AA index is slightly below 2.5 due to a combination of sea-ice-induced AA and GHG-driven uniform warming. Future projections suggest a gradual decline in the AA index towards 1.0 as Arctic sea ice disappears, ultimately eliminating the AA phenomenon and leaving a GHG-dominated warming pattern in the NH.

Previous studies have demonstrated that the Trace-21ka transient simulation effectively captures the major climate features of the past 21,000 years46. However, the low-resolution version of the CCSM3 model used for this simulation has an Equilibrium Climate Sensitivity close to 2.3 °C49,54, which falls below the high-confidence range of 2.5–4.0 °C reported in the IPCC AR6 report55. This suggests that our results may slightly underestimate the magnitude of AA. In future work, the availability of additional transient simulations covering the past 21,000 years would provide an opportunity to assess AA across a broader range of models, improving our understanding of this phenomenon and its representation in climate models.

Several questions remain unanswered in this study. For example, why does the natural AA index range from 1.7 to 3.3, with such a stable median of 2.5? How does Antarctic amplification compare to AA on glacial-interglacial timescales? Is there a correlation between these two polar amplification signals56? Further research, incorporating both model simulations and proxy data, is expected to address these questions and enhance our understanding of polar amplification dynamics. Such knowledge will provide valuable insights into current and future climate projections.

Methods

Definition of AA index

The AA index or AA ratio in this article is defined as

where \({y}_{n}\) is the AA index at the nth time point, \({win}\) is the time window of 100 years used to calculate linear trends (sensitivity analysis discussed below), \(T\) represents 2 m air temperature, and the Arctic region is defined as 60° N–90° N (sensitivity analysis discussed below). Those \({y}_{n}\) with NH trends less than 0.02 °C/100a were excluded due to physically unrealistic results caused by a near-zero denominator. Consequently, there are 1972, 1901, and 1 valid sample(s) can be extracted from TraCE-21ka, NOAA-NCEI/LMR, and NOAA-CIRES/20CR, respectively.

The NH temperature trend, rather than the global mean, is employed as the denominator for the AA index. This choice is justified by the known out-of-phase relationship between NH and SH temperature variations evident in orbital timescale studies. Our definition of the AA index not only precisely quantifies AA but also effectively prevents near-zero denominator issues. Thus, our AA index is well-suited for paleoclimate investigations, particularly those focused on orbital timescales.

Sensitivity of AA index to Arctic region definition

The Arctic region for AA index calculation is defined as 60° N–90° N to align with previous studies. Given the fluctuating extent of North Atlantic sea ice over different climate epochs (Supplementary Fig. 4), we explored AA index distributions using alternative Arctic region definitions from 45° N–90° N to 70° N-90° N with 5° increments (Supplementary Fig. 5). Our results indicate no substantial differences in AA index patterns across these definitions, suggesting that the AA index is insensitive to Arctic region selection.

Sensitivity of AA index to temporal window

We also examined the sensitivity of the AA index to temporal window length using NOAA-CIRES/20CR data (Supplementary Figs. 7 and 8). Results indicate that temporal windows shorter than 64 years are significantly influenced by high-frequency internal climate variability. Conversely, windows exceeding 100 years produce super-stabilized AA indices within the 2–6 range, aligning with previous studies. Considering these findings and computational efficiency, a 100-year window was selected for AA index calculation, providing a suitable balance for capturing Arctic and NH temperature trends characteristic of typical AA events.

Robustness of the AA Index at 2.5

We assessed the robustness of the AA index using two approaches. First, we calculated the linear regression coefficient of Arctic temperature change relative to NH temperature change within the TraCE-21ka dataset, yielding a best-fit slope of 2.46 (Supplementary Fig. 2). Second, we determined the distribution of all AA indices in TraCE-21ka by weighting them according to their corresponding NH temperature changes, as shown in the main text. This approach emphasizes instances of effective AA, represented by the 9 and 3 o’clock positions of the diamond-shaped distribution (Fig. 2a). To optimize the distribution analysis, we experimented with different bin sizes and selected 0.05 as the optimal value to balance systematic and sampling errors in computing the AA’s statistics, like the median (Supplementary Fig. 6). Finally, a Gaussian fit applied to the weighted AA index distribution yielded a median of 2.5 with a ±0.8 spread encompassing 50% of the total variance (Fig. 2c). Hence, both approaches produce the same median AA index of 2.5.

Furthermore, we also compared AA indices from the TraCE-21ka simulation with those from PMIP3 snapshots (Supplementary Fig. 2b). The best-fit slope of eight PMIP3 model simulations is 2.33, close to the value 2.32 obtained from TraCE-21ka, suggesting that TraCE-21ka simulations are reliable and representative. It is important to note that the 2.33 (multi-model mean) and 2.32 (TraCE-21ka) values represent glacial-interglacial timescales (6ka minus 21ka), distinct from the previously mentioned 2.5 derived on centennial timescales. Therefore, it is strictly inappropriate to directly compare the AA index from PMIP3 (Supplementary Fig. 2b) with the AA index discussed in this paper (Supplementary Fig. 2a; Fig. 2).

A simplified model to quantify AA extent

To more precisely estimate the southern extent of high-latitude AA regions, hereafter referred to as the critical latitude, we developed a conceptual model (Supplementary Fig. 3). For the natural AA mode, a constant NH warming rate of 1 °C/100a is assumed, with a critical latitude dividing the Arctic (warming at 2.5 °C/100a) from the low latitudes (warming at X °C/100a) regions (Supplementary Fig. 3a). The basic assumption is that the AA index remains fixed at 2.5, while the critical latitude shifts with varying low-latitude warming rates (X). This framework encompasses all potential configurations of critical latitudes (black lines), ranging from the southernmost one (red line) to the northernmost one (blue line). Paleoclimate simulations align closely with the red line, indicating a critical latitude near 37°N (Fig. 3a, b), likely due to expanded sea ice compared to the present. In contrast, the anthropogenic AA mode superimposes uniform hemispheric warming (0.5 °C/100a, for example) on the natural AA mode (Supplementary Fig. 3b), resulting in an AA index below 2.5 slightly. Modern observations approximate the blue line in Supplementary Fig. 3b, with AA indices of 2.43 and 2.36 from NOAA-CIRES/20CR and CMIP6/C20C, respectively, during 1901–2000.

Data availability

All data used in the study is freely available online. Below is a brief description of each dataset. TraCE-21ka The project of Simulation of Transient Climate Evolution over the last 21,000 years (TraCE-21ka), led by NCAR/CGD, provides a key dataset spanning the period from the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM) to the present climate. This project utilizes the Community Climate System Model version 3 (CCSM3), which incorporates several coupled components: the Community Atmospheric Model 3 (CAM3), the Parallel Ocean Program (POP), and the Community Sea Ice Model (CSIM), and the dynamic vegetation model (DGVM). Notably, TraCE-21ka as NCAR’s longest publicly accessible transient experiment, successfully reproduces a series of paleoclimate events and key processes, including Heinrich Stadial 1 (H1), the Bølling-Allerød (BA) warming, and the Younger Dryas (YD) cold period. This project’s relevant documentation and data can be accessed through NCAR’s website: https://www.cgd.ucar.edu/ccr/TraCE/. and ESG website: https://www.earthsystemgrid.org/project/trace.html. This dataset is the core data of this paper, primarily used to analyze the scope and variability of the AA ratio over the past 21,000 years. PMIP3 This study leverages snapshot simulations from eight climate models participating in the Paleoclimate Modelling Intercomparison Project Phase 3 (PMIP3). PMIP3 is a collaborative effort that generates climate model simulations for specific time periods: 21,000 years before present (21ka), 6000 years before present (6ka), and the present day (0ka). The specific models employed in this work are: (1) GISS-E2-R, (2) MIROC-ESM, (3) FGOALS-g2, (4) MPI-ESM-P, (5) IPSL-CM5A-LR, (6) MRI-CGCM3, (7) CNRM-CM5, and (8) CCSM4. Detailed descriptions and data access information for these models can be found on the PMIP3 website: https://pmip3.lsce.ipsl.fr/. This dataset is primarily used to analyze the Arctic and NH temperature changes from 6ka compared to 21ka. The relevant discussion is concentrated in the ‘Robustness of the AA Index at 2.5’ section of the Method. NOAA-NCEI/LMR The project of Last Millennium Reanalysis (LMR) version 1, led by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI), provides a complete reanalysis dataset for the last two millennia. The dataset includes 20 Monte Carlo simulations for the period 1–2000 C.E. For further information on LMR, refer to Hakim et al.57 and see https://www.atmos.uw.edu/~hakim/LMR/. This dataset is primarily used for the diversity analysis of the AA index in Section “Variability of AA ratio in the last 21,000 years”. NOAA-CIRES/20CR The project of 20th Century Reanalysis Version 2c (20CR V2c), led by NOAA and the Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences (CIRES), offers monthly 2-m air temperature data spanning from 1851/01 to 2014/12. More details are available at https://psl.noaa.gov/data/gridded/data.20thC_ReanV2c.html. This dataset is primarily used for the diversity analysis of the AA index in Section “Variability of AA ratio in the last 21,000 years”. GISTEMP v4 The project of Surface Temperature Analysis from NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies version 4 (GISTEMP v4) provides combined ocean and land surface temperature data on a 2° × 2 °C grid for the period 1880-present. This dataset is well-known for its strength in the inclusion of satellite observations. More information can be found on the NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies website: http://data.giss.nasa.gov/gistemp/. This dataset is primarily used to calculate and display the centennial temperature change trends of the 20th century, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 1. CRU TS4 The project of Climatic Research Unit (CRU) Time-Series version 4 (TS4) offers high-resolution (0.5° × 0.5°) monthly land-only near-surface temperature data. It leverages observations from over 4000 weather stations worldwide, covering the period 1901-present. For further details, please refer to the CRU website: https://crudata.uea.ac.uk/cru/data/hrg/. This dataset is primarily used to calculate and display the centennial temperature change trends of the 20th century, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 1. ERA 20C The project of 20th Century Reanalysis from the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF/ERA 20C) provides monthly 2-m temperature data. It incorporates observations of surface pressure and surface marine winds to generate a reanalysis with a horizontal resolution of approximately 125 km (spectral truncation T159), covering the period 1900-present. Further information can be accessed on the ECMWF website https://ecmwf.int/en/forecasts/datasets/reanalysis-datasets/era-20c. This dataset is primarily used to calculate and display the centennial temperature change trends of the 20th century, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 1. CMIP6 This study utilizes eight models’ results from the Coupled Model Inter-comparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6) to estimate the AA ratio in historical climate (pre-industrial to present) and future projections under the Shared Socioeconomic Pathways 5-8.5 (SSP5-8.5) scenarios58. These 8 models include CESM2, CMCC-CM2-SR5, FGOALS-f3-L, CanESM5, FIO-ESM-2-0, UKESM1-0-LL, E3SM-1-1, and CIESM2. Due to data availability limitations, only four models (MRI-ESM2-0, IPSL-CM6A-LR, UKESM1-0-LL, and CanESM5) were employed to estimate long-term future climate for the extended SSP5-8.5 scenario over the period 2151–2250. It should be noted that SSP5-8.5 aligns closely with the Representative Concentration Pathway 8.5 (RCP8.5) scenario used in CMIP558. Further information on the CMIP6 project and data can be found on the website https://www.wcrp-climate.org/wgcm-cmip/wgcm-cmip6. This dataset is primarily used to calculate and compare surface air temperature trends for the past (1901–2000), near future (2001–2100), and far future (2151–2250), discussing the roles of CO2 and Arctic sea ice in different periods, as shown in Fig. 1.

References

Serreze, M. C. & Barry, R. G. Processes and impacts of Arctic amplification: a research synthesis. Glob. Planet. Chang. 77, 85–96 (2011).

Collins, M. et al. Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis: Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Ch.12 (Cambridge University Press, 2013).

Smith, D. M. et al. The Polar Amplification Model Intercomparison Project (PAMIP) contribution to CMIP6: investigating the causes and consequences of polar amplification. Geosci. Model Dev. 12, 1139–1164 (2019).

Francis, J. A. & Vavrus, S. J. Evidence linking Arctic amplification to extreme weather in mid-latitudes. Geophys. Res. Lett. 39, L06801 (2012).

Cohen, J. et al. Recent Arctic amplification and extreme mid-latitude weather. Nat. Geosci. 7, 627–637 (2014).

Barnes, E. A. & Screen, J. A. The impact of Arctic warming on the midlatitude jet-stream: can it? Has it? Will it?. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Chang. 6, 277–286 (2015).

Coumou, D., Capua, G. D., Vavrus, S., Wang, L. & Wang, S. The influence of Arctic amplification on mid-latitude summer circulation. Nat. Commun. 9, 2959 (2018).

Previdi, M., Smith, K. L. & Polvani, L. M. Arctic amplification of climate change: a review of underlying mechanisms. Environ. Res. Lett. 16, 093003 (2021).

Henderson, G. R. et al. Local and remote atmospheric circulation drivers of arctic change: a review. Front. Earth Sci. 9, 549 (2021).

Dai, A., Luo, D., Song, M. & Liu, J. Arctic amplification is caused by sea-ice loss under increasing CO2. Nat. Commun. 10, 1–13 (2019).

Blackport, R. & Kushner, P. J. The role of extratropical ocean warming in the coupled climate response to Arctic Sea ice loss. J. Clim. 31, 9193–9206 (2018).

Deser, C., Robert, A. T. & Sun, L. The role of ocean-atmosphere coupling in the zonal-mean atmospheric response to Arctic sea ice loss. J. Clim. 28, 2168–2186 (2015).

Cai, M. Dynamical greenhouse-plus feedback and polar warming amplification. Part I: a dry radiative-transportive climate model. Clim. Dynam. 26, 661–675 (2006).

Cai, M. & Lu, J. Dynamical greenhouse-plus feedback and polar warming amplification. Part II: meridional and vertical asymmetries of the global warming. Clim. Dynam. 29, 375–391 (2007).

Hwang, Y. T., Frierson, D. M. W. & Kay, J. E. Coupling between Arctic feedbacks and changes in poleward energy transport. Geophys. Res. Lett. 38, 17 (2011).

Yoo, C., Feldstein, S. & Lee, S. The impact of the Madden-Julian Oscillation trend on the Arctic amplification of surface air temperature during the 1979–2008 boreal winter. Geophys. Res. Lett. 38, 24 (2011).

Spielhagen, R. F. et al. Enhanced modern heat transfer to the Arctic by warm Atlantic water. Science 331, 450–453 (2011).

Screen, J. & Francis, J. A. Contribution of sea-ice loss to Arctic amplification is regulated by Pacific Ocean decadal variability. Nat. Clim. Chang. 6, 856–860 (2016).

Chemke, R., Polvani, L. M., Kay, J. E. & Orbe, C. Quantifying the role of ocean coupling in Arctic amplification and sea-ice loss over the 21st century. NPJ Clim. Atmos. Sci. 4, 1–9 (2021).

Zhou, W., Leung, L. R., Xie, S.-P. & Lu, J. An analytic theory for the degree of Arctic Amplification. Nat. Commun. 15, 5060 (2024).

Alexeev, V. A., Langen, P. L. & Bates, J. R. Polar amplification of surface warming on an aquaplanet in “ghost forcing” experiments without sea ice feedbacks. Clim. Dynam. 24, 655–666 (2005).

Cronin, T. W. & Tziperman, E. Low clouds suppress Arctic air formation and amplify high-latitude continental winter warming. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, 11490–11495 (2015).

Taylor, P. C. et al. A decomposition of feedback contributions to polar warming amplification. J. Clim. 26, 7023–7043 (2013).

Graversen, R. G., Langen, P. L. & Mauritsen, T. Polar amplification in CCSM4: contributions from the lapse rate and surface albedo feedbacks. J. Clim. 27, 4433–4450 (2014).

Pithan, F. & Mauritsen, T. Arctic amplification dominated by temperature feedbacks in contemporary climate models. Nat. Geosci. 7, 181–184 (2014).

Stuecker, M. F. et al. Polar amplification dominated by local forcing and feedbacks. Nat. Clim. Chang. 8, 1076–1081 (2018).

Hahn, L. C., Armour, K. C., Zelinka, M. D., Bitz, C. M. & Donohoe, A. Contributions to polar amplification in CMIP5 and CMIP6 models. Front. Earth Sci. 9, 725 (2021).

Latonin, M. M., Bashmachnikov, I. L., Bobylev, L. P. & Davy, R. Multi-model ensemble mean of global climate models fails to reproduce early twentieth century Arctic warming. Polar Sci. 30, 100677 (2021).

Davy, R., Chen, L. & Edward, H. Arctic amplification metrics. Int. J. Climatol. 38, 4384–4394 (2018).

Bekryaev, R. V., Polyakov, I. V. & Alexeev, V. A. Role of polar amplification in long-term surface air temperature variations and modern Arctic warming. J. Clim. 23, 3888–3906 (2010).

Chylek, P., Folland, C. K., Lesins, G., Dubey, M. K. & Wang, M. Arctic air temperature change amplification and the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation. Geophys. Res. Lett. 36, L14801 (2009).

Barnes, E. A. & Polvani, L. M. CMIP5 projections of Arctic amplification, of the North American/North Atlantic circulation, and of their relationship. J. Clim. 28, 5254–5271 (2015).

Rantanen, M. et al. The Arctic has warmed nearly four times faster than the globe since 1979. Commun. Earth Environ. 3, 168 (2022).

Zhou, W., Leung, L. R. & Lu, J. Steady threefold Arctic amplification of externally forced warming masked by natural variability. Nat. Geosci. 17, 508–515 (2024).

Yoshimori, M., Watanabe, M., Abe-Ouchi, A., Shiogama, H. & Ogura, T. Relative contribution of feedback processes to Arctic amplification of temperature change in MIROC GCM. Clim. Dynam. 42, 1613–1630 (2014).

Winton, M. Amplified Arctic climate change: what does surface albedo feedback have to do with it?. Geophys. Res. Lett. 33, L03701 (2006).

Holland, M. M. & Bitz, C. M. Polar amplification of climate change in coupled models. Clim. Dynam. 21, 221–232 (2003).

Notz, D. & SIMIP Community Arctic sea ice in CMIP6. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e2019GL086749 (2020).

Park, H. S., Kim, S. J., Stewart, A. L., Son, S. W. & Seo, K. H. Mid-holocene Northern Hemisphere warming driven by Arctic amplification. Sci. Adv. 5, eaax8203 (2019).

Marcott, S. A., Shakun, J. D., Clark, P. U. & Mix, A. C. A reconstruction of regional and global temperature for the past 11,300 years. Science 339, 1198–1201 (2013).

Sundqvist, H. S. et al. Arctic Holocene proxy climate database–new approaches to assessing geochronological accuracy and encoding climate variables. Clim. Past 10, 1605–1631 (2014).

Bartlein, P. J. et al. Pollen-based continental climate reconstructions at 6 and 21 ka: a global synthesis. Clim. Dynam. 37, 775–802 (2011).

Masson-Delmotte, V. et al. Past and future polar amplification of climate change: climate model intercomparisons and ice-core constraints. Clim. Dynam. 26, 513–529 (2006).

Miller, G. H. et al. Arctic amplification: can the past constrain the future?. Quat. Sci. Rev. 29, 1779–1790 (2010).

Liu, Z. et al. Transient Simulation of last deglaciation with a new mechanism for Bølling-Allerød warming. Science 325, 310–314 (2009).

He, F. Simulating Transient Climate Evolution of the Last Deglaciation with CCSM3. PhD thesis, University Wisconsin-Madison (2011).

Shakun, J. et al. Global warming preceded by increasing carbon dioxide concentrations during the last deglaciation. Nature 484, 49–54 (2012).

Otto-Bliesner, B. et al. Coherent changes of southeastern equatorial and northern African rainfall during the last deglaciation. Science 346, 1223–1227 (2014).

Collins, W. D. et al. The Community Climate System Model Version 3 (CCSM3). J. Clim. 19, 2122–2143 (2006).

Screen, J. A. et al. Consistency and discrepancy in the atmospheric response to Arctic sea-ice loss across climate models. Nat. Geosci. 11, 155–163 (2018).

Navarro, J. C. A. et al. Amplification of Arctic warming by past air pollution reductions in Europe. Nat. Geosci. 9, 277–281 (2016).

Beer, E., Eisenman, I. & Wagner, T. J. W. Polar amplification due to enhanced heat flux across the halocline. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, https://doi.org/10.1029/e2019GL086706 (2020).

Jenkins, M. & Dai, A. The impact of sea-ice loss on arctic climate feedbacks and their role for Arctic amplification. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48, https://doi.org/10.1029/e2021GL094599 (2021).

Kiehl, J. T., Shields, C. A., Hack, J. J. & Collins, W. D. The Climate Sensitivity of the Community Climate System Model Version 3 (CCSM3). J. Clim. 19, 2584–2596 (2006).

IPCC. Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change 1–2338 (Cambridge University Press, 2021).

Chylek, P. C., Folland, C. K., Lesins, G. & Dubey, M. K. Twentieth century bipolar seesaw of the Arctic and Antarctic surface air temperatures. Geophys. Res. Lett. 37, L08703 (2010).

Hakim, G. J. et al. The last millennium climate reanalysis project: framework and first results. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 121, 6745–6764 (2016).

O’Neill, B. C. et al. The scenario model intercomparison project (ScenarioMIP) for CMIP6. Geosci. Model Dev. 9, 3461–3482 (2016).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grants 41875088 and 42342017) and the Universidad Nacional de San Agustin of Peru (grant 20163646499).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.W. conceived the study; Y.Y. and X.W. designed the study approach; Y.Y. performed data analysis; Y.Y., X.W., J.M., and X.M.H. contributed to the manuscript writing. X.W. reviewed earlier versions of the manuscript but sadly passed away before its final submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yan, Y., Wen, X., Mei, J. et al. A stable Arctic amplification ratio in long-term transient simulation over the last 21,000 years. npj Clim Atmos Sci 8, 321 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-01212-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-01212-8