Abstract

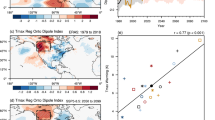

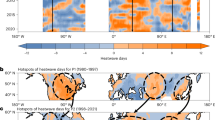

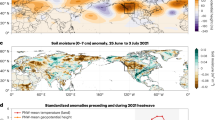

Western North America (WNA) is a regional hotspot for summer heat extremes. However, our understanding of the atmospheric processes driving WNA heatwaves remains largely based on a few case studies. In this study, we investigate the general characteristics of atmospheric pathways associated with WNA heatwaves using a 30-member high-resolution coupled model simulation. Synthesizing the WNA heatwave events across the large ensemble, we reinforce the view that WNA heatwaves are systematically driven by: (1) a Rossby wave train originating from the western North Pacific, (2) poleward moisture transport toward the Gulf of Alaska, occasionally via atmospheric rivers, and (3) downstream ridge amplification over WNA. Although these features also appear in the late twenty-first-century projections, notable changes include farther poleward moisture transport and broader ridge development in the future. Under the anomaly-based heatwave definition used in this study, which removes the influence of mean temperature change, the frequency of WNA heatwaves is projected to decrease. Our findings suggest that mechanisms identified in case studies, including upstream Rossby wave packets and subsequent moist processes, are broadly applicable to understanding WNA heatwaves over recent decades and their projected changes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

All data used in this study are publicly available. NOAA-CPC global daily maximum/minimum temperature and precipitation data can be downloaded from https://psl.noaa.gov/data/gridded/index.html. SPEAR Large ensemble data can be downloaded from https://www.gfdl.noaa.gov/spear_large_ensembles/. The CMIP6 model output used in this study is available at https://aims2.llnl.gov/search/cmip6/. The ERA5 reanalysis hourly data used in the Supplementary Information can be downloaded from https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/datasets/reanalysis-era5-pressure-levels?tab=overview for pressure levels.

Code availability

The feature tracking algorithm code used in this study is a Python open-source package, CONTRACK, which is accessible from https://github.com/steidani/ConTrack52. Other custom scripts directly implement the statistical methods and techniques described in the “Methods” section.

References

World Meteorological Organization. State of the Global Climate 2024 (World Meteorological Organization, 2025).

Meehl, G. A. & Tebaldi, C. More intense, more frequent, and longer lasting heat waves in the 21st century. Science 305, 994–997 (2004).

Donat, M. G., L. V. Alexander, N. Herold, & A. J. Dittus. Temperature and precipitation extremes in century-long gridded observations, reanalyses, and atmospheric model simulations. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 121, 11,174–11,189 (2016).

Seneviratne, S. I. et al. in Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (eds Masson-Delmotte, V. et al.) 1513–1766 (Cambridge University Press, 2021).

Rahmstorf, S. & Coumou, D. Increase of extreme events in a warming world. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108, 17905–17909 (2011).

Fischer, E. M., Sippel, S. & Knutti, R. Increasing probability of record-shattering climate extremes. Nat. Clim. Chang. 11, 689–695 (2021).

McHugh, C. E., Delworth, T. L., Cooke, W. & Jia, L. Using large ensembles to examine historical and projected changes in record-breaking summertime temperatures over the Contiguous United States. Earths Future 11 https://doi.org/10.1029/2023ef003954 (2023).

Matthews, T. et al. Humid heat exceeds human tolerance limits and causes mass mortality. Nat. Clim. Change 15, 4–6 (2024).

Ting, M. et al. Contrasting impacts of dry versus humid heat on US corn and soybean yields. Sci. Rep. 13, 710 (2023).

Richardson, D. et al. Global increase in wildfire potential from compound fire weather and drought. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 5, 23 (2022).

Tian, Y. et al. Characterizing heatwaves based on land surface energy budget. Commun. Earth Environ. 5 https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-024-01784-y (2024).

Barriopedro, D., Fischer, E. M., Luterbacher, J., Trigo, R. M. & García-Herrera, R. The hot summer of 2010: redrawing the temperature record map of Europe. Science 332, 220–224 (2011).

McKinnon, K. A., Rhines, A., Tingley, M. P. & Huybers, P. The changing shape of Northern Hemisphere summer temperature distributions. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 121, 8849–8868 (2016).

Seneviratne, S. I., Donat, M. G., Pitman, A. J., Knutti, R. & Wilby, R. L. Allowable CO2 emissions based on regional and impact-related climate targets. Nature 529, 477–483 (2016).

White, R. H. et al. The unprecedented Pacific Northwest heatwave of June 2021. Nat. Commun. 14, 727 (2023).

Thompson, V. et al. The 2021 western North America heat wave among the most extreme events ever recorded globally. Sci. Adv. 8, eabm6860 (2022).

Zhang, Y. & Boos, W. R. An upper bound for extreme temperatures over midlatitude land. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2215278120 (2023).

Schumacher, D. L., Hauser, M. & Seneviratne, S. I. Drivers and mechanisms of the 2021 Pacific Northwest heatwave. Earths Future 10 https://doi.org/10.1029/2022ef002967 (2022).

Neal, E., Huang, C. S. Y. & Nakamura, N. The 2021 Pacific Northwest heat wave and associated blocking: meteorology and the role of an upstream cyclone as a diabatic source of wave activity. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49 https://doi.org/10.1029/2021gl097699 (2022).

Yu, B., Lin, H., Mo, R. & Li, G. A physical analysis of summertime North American heatwaves. Clim. Dyn. 61, 1551–1565 (2023).

Röthlisberger, M. & Papritz, L. Quantifying the physical processes leading to atmospheric hot extremes at a global scale. Nat. Geosci. 16, 210–216 (2023).

Li, X. et al. Role of atmospheric resonance and land-atmosphere feedbacks as a precursor to the June 2021 Pacific Northwest Heat Dome event. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 121, e2315330121 (2024).

Mo, R., Lin, H. & Vitart, F. An anomalous warm-season trans-Pacific atmospheric river linked to the 2021 western North America heatwave. Commun. Earth Environ. 3 https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-022-00459-w (2022).

Lin, H., Mo, R. & Vitart, F. The 2021 Western North American heatwave and its subseasonal predictions. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49 https://doi.org/10.1029/2021gl097036 (2022).

Qian, Y. et al. Effects of subseasonal variation in the East Asian monsoon system on the summertime heat wave in Western North America in 2021. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49 https://doi.org/10.1029/2021gl097659 (2022).

Domeisen, D. I. V. et al. Prediction and projection of heatwaves. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 4, 36–50 (2022).

Barriopedro, D., García-Herrera, R., Ordóñez, C., Miralles, D. G. & Salcedo-Sanz, S. Heat waves: physical understanding and scientific challenges. Rev. Geophys. 61 https://doi.org/10.1029/2022rg000780 (2023).

Loikith, P. C., Lintner, B. R. & Sweeney, A. Characterizing large-scale meteorological patterns and associated temperature and precipitation extremes over the Northwestern United States using self-organizing maps. J. Clim. 30, 2829–2847 (2017).

Steinfeld, D. & Pfahl, S. The role of latent heating in atmospheric blocking dynamics: a global climatology. Clim. Dyn. 53, 6159–6180 (2019).

Lee, H.-I. & Nakamura, N. Imprint of diabatic processes in the waviness of the jet stream: an analysis of local wave activity budget. J. Clim. 37, 5703–5719 (2024).

Brunner, L., Schaller, N., Anstey, J., Sillmann, J. & Steiner, A. K. Dependence of present and future European temperature extremes on the location of atmospheric blocking. Geophys. Res. Lett. 45, 6311–6320 (2018).

Wehner, M. et al. Changes in extremely hot days under stabilized 1.5 and 2.0 °C global warming scenarios as simulated by the HAPPI multi-model ensemble. Earth Syst. Dyn. 9, 299–311 (2018).

Jia, L. et al. Skillful seasonal prediction of North American summertime heat extremes. J. Clim. 35, 4331–4345 (2022).

Labe, Z. M., Johnson, N. C. & Delworth, T. L. Changes in United States summer temperatures revealed by explainable neural networks. Earths Future 12 https://doi.org/10.1029/2023ef003981 (2024).

Nabizadeh, E., Lubis, S. W. & Hassanzadeh, P. The 3D structure of Northern Hemisphere blocking events: climatology, role of moisture, and response to climate change. J. Clim. 34, 9837–9860 (2021).

Tseng, K. C. et al. When will humanity notice its influence on atmospheric rivers? J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 127 https://doi.org/10.1029/2021jd036044 (2022).

Park, M., Johnson, N. C. & Delworth, T. L. The driving of North American climate extremes by North Pacific stationary-transient wave interference. Nat. Commun. 15, 7318 (2024).

Held, I. M. & Soden, B. J. Robust responses of the hydrological cycle to global warming. J. Clim. 19, 5686–5699 (2006).

Pfahl, S., O’Gorman, P. A. & Fischer, E. M. Understanding the regional pattern of projected future changes in extreme precipitation. Nat. Clim. Change 7, 423–427 (2017).

Eyring, V. et al. Overview of the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6) experimental design and organization. Geosci. Model Dev. 9, 1937–1958 (2016).

Di Luca, A., de Elía, R., Bador, M. & Argüeso, D. Contribution of mean climate to hot temperature extremes for present and future climates. Weather Clim. Extrem. 28, 100255 (2020).

Marin, M., Feng, M., Phillips, H. E. & Bindoff, N. L. A global, multiproduct analysis of coastal marine heatwaves: distribution, characteristics, and long-term trends. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 126 https://doi.org/10.1029/2020jc016708 (2021).

Duan, S. Q., Findell, K. L. & Wright, J. S. Three regimes of temperature distribution change over dry land, moist land, and oceanic surfaces. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47 https://doi.org/10.1029/2020gl090997 (2020).

Srivastava, A. K., Wehner, M., Bonfils, C., Ullrich, P. A. & Risser, M. Local hydroclimate drives differential warming rates between regular summer days and extreme hot days in the Northern Hemisphere. Weather Clim. Extrem. 45, 100709 (2024).

Chan, P. W., Catto, J. L. & Collins, M. Heatwave–blocking relation change likely dominates over decrease in blocking frequency under global warming. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 5, 68 (2022).

Shepherd, T. G. Atmospheric circulation as a source of uncertainty in climate change projections. Nat. Geosci. 7, 703–708 (2014).

Tamarin-Brodsky, T., Hodges, K., Hoskins, B. J. & Shepherd, T. G. Changes in Northern Hemisphere temperature variability shaped by regional warming patterns. Nat. Geosci. 13, 414–421 (2020).

Loikith, P. C. & Broccoli, A. J. Characteristics of observed atmospheric circulation patterns associated with temperature extremes over North America. J. Clim. 25, 7266–7281 (2012).

Byrne, M. P. & O’Gorman, P. A. Trends in continental temperature and humidity directly linked to ocean warming. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 115, 4863–4868 (2018).

Miralles, D. G., Teuling, A. J., van Heerwaarden, C. C. & Vilà-Guerau de Arellano, J. Mega-heatwave temperatures due to combined soil desiccation and atmospheric heat accumulation. Nat. Geosci. 7, 345–349 (2014).

Prodhomme, C. et al. Seasonal prediction of European summer heatwaves. Clim. Dyn. 58, 2149–2166 (2021).

Steinfeld, D., ConTrack - Contour Tracking. GitHub, https://github.com/steidani/ConTrack (2020).

Maddison, J. W., Gray, S. L., Martínez-Alvarado, O. & Williams, K. D. Impact of model upgrades on diabatic processes in extratropical cyclones and downstream forecast evolution. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 146, 1322–1350 (2020).

Kautz, L.-A. et al. Atmospheric blocking and weather extremes over the Euro-Atlantic sector—a review. Weather Clim. Dyn. 3, 305–336 (2022).

Wandel, J., Büeler, D., Knippertz, P., Quinting, J. F. & Grams, C. M. Why moist dynamic processes matter for the sub-seasonal prediction of atmospheric blocking over Europe. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 129 https://doi.org/10.1029/2023jd039791 (2024).

Hauser, S., Teubler, F., Riemer, M., Knippertz, P. & Grams, C. M. Life cycle dynamics of Greenland blocking from a potential vorticity perspective. Weather Clim. Dyn. 5, 633–658 (2024).

Chan, P. W., Hassanzadeh, P. & Kuang, Z. Evaluating indices of blocking anticyclones in terms of their linear relations with surface hot extremes. Geophys. Res. Lett. 46, 4904–4912 (2019).

Loikith, P. C., Singh, D. & Taylor, G. P. Projected changes in atmospheric ridges over the Pacific–North American region using CMIP6 models. J. Clim. 35, 5151–5171 (2022).

Steinfeld, D., Sprenger, M., Beyerle, U. & Pfahl, S. Response of moist and dry processes in atmospheric blocking to climate change. Environ. Res. Lett. 17, 084020 (2022).

Scholz, S. R. & Lora, J. M. Atmospheric rivers cause warm winters and extreme heat events. Nature 636, 640–646 (2024).

Alexander, L. V. et al. Global observed changes in daily climate extremes of temperature and precipitation. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 111 https://doi.org/10.1029/2005jd006290 (2006).

Seneviratne, S. I. et al. Investigating soil moisture–climate interactions in a changing climate: a review. Earth Sci. Rev. 99, 125–161 (2010).

Hsu, H. & Dirmeyer, P. A. Soil moisture-evaporation coupling shifts into new gears under increasing CO(2). Nat. Commun. 14, 1162 (2023).

Fischer, E. M., Seneviratne, S. I., Vidale, P. L., Lüthi, D. & Schär, C. Soil moisture–atmosphere interactions during the 2003 European summer heat wave. J. Clim. 20, 5081–5099 (2007).

Liu, P., Reed, K. A., Garner, S. T., Zhao, M. & Zhu, Y. Blocking simulations in GFDL GCMs for CMIP5 and CMIP6. J. Clim. 35, 5053–5070 (2022).

Coumou, D., Di Capua, G., Vavrus, S., Wang, L. & Wang, S. The influence of Arctic amplification on mid-latitude summer circulation. Nat. Commun. 9, 2959 (2018).

Lehmann, J., Coumou, D., Frieler, K., Eliseev, A. V. & Levermann, A. Future changes in extratropical storm tracks and baroclinicity under climate change. Environ. Res. Lett. 9, 084002 (2014).

Harvey, B. J., Shaffrey, L. C. & Woollings, T. J. Equator-to-pole temperature differences and the extra-tropical storm track responses of the CMIP5 climate models. Clim. Dyn. 43, 1171–1182 (2014).

Chang, E. K. M., Ma, C. G., Zheng, C. & Yau, A. M. W. Observed and projected decrease in Northern Hemisphere extratropical cyclone activity in summer and its impacts on maximum temperature. Geophys. Res. Lett. 43, 2200–2208 (2016).

Priestley, M. D. K. & Catto, J. L. Future changes in the extratropical storm tracks and cyclone intensity, wind speed, and structure. Weather Clim. Dyn. 3, 337–360 (2022).

Lackmann, G. M., Miller, R. L., Robinson, W. A. & Michaelis, A. C. Persistent anomaly changes in high-resolution climate simulations. J. Clim. 34, 5425–5442 (2021).

Goss, M., Feldstein, S. B. & Lee, S. Stationary wave interference and its relation to tropical convection and Arctic warming. J. Clim. 29, 1369–1389 (2016).

Chemke, R. & Ming, Y. Large atmospheric waves will get stronger, while small waves will get weaker by the end of the 21st century. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47 https://doi.org/10.1029/2020gl090441 (2020).

Woollings, T., Drouard, M., O’Reilly, C. H., Sexton, D. M. H. & McSweeney, C. Trends in the atmospheric jet streams are emerging in observations and could be linked to tropical warming. Commun. Earth Environ. 4 https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-023-00792-8 (2023).

Vallis, G. K., Zurita-Gotor, P., Cairns, C. & Kidston, J. Response of the large-scale structure of the atmosphere to global warming. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 141, 1479–1501 (2015).

Mann, H. B. Nonparametric tests against trend. Econometrica 13, 245–259 (1945).

Hoskins, B. J. & Ambrizzi, T. Rossby wave propagation on a realistic longitudinally varying flow. J. Atmos. Sci. 50, 1661–1671 (1993).

White, R. H., Kornhuber, K., Martius, O. & Wirth, V. From atmospheric waves to heatwaves: a waveguide perspective for understanding and predicting concurrent, persistent, and extreme extratropical weather. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 103, E923–E935 (2022).

Holton, J. R. & Hakim, G. J. An Introduction to Dynamic Meteorology, Vol. 88 (Academic Press, 2013).

Simpson, I. R. et al. An evaluation of the large-scale atmospheric circulation and its variability in CESM2 and other CMIP models. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 125 https://doi.org/10.1029/2020jd032835 (2020).

Zhang, Y. et al. Disagreement in detected heatwave trends resulting from diagnostic methods. Geophys. Res. Lett. 52 https://doi.org/10.1029/2024gl114398 (2025).

Li, Z. & Ding, Q. A global poleward shift of atmospheric rivers. Sci. Adv. 10, eadq0604 (2024).

Priestley, M. D. K. et al. An overview of the extratropical storm tracks in CMIP6 historical simulations. J. Clim. 33, 6315–6343 (2020).

Delworth, T. L. et al. SPEAR: the next generation GFDL modeling system for seasonal to multidecadal prediction and projection. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 12 https://doi.org/10.1029/2019ms001895 (2020).

Shevliakova, E. et al. The land component LM4.1 of the GFDL earth system model ESM4.1: model description and characteristics of land surface climate and carbon cycling in the historical simulation. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 16 https://doi.org/10.1029/2023ms003922 (2024).

Lubis, S. W. et al. Enhanced Pacific Northwest heat extremes and wildfire risks induced by the boreal summer intraseasonal oscillation. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 7, 232 (2024).

Xiang, B., Wang, B., Chen, G. & Delworth, T. L. Prediction of diverse boreal summer intraseasonal oscillation in the GFDL SPEAR model. J. Clim. 37, 2217–2230 (2024).

Woollings, T. et al. Blocking and its response to climate change. Curr. Clim. Change Rep. 4, 287–300 (2018).

Raymond, C., Matthews, T. & Horton, R. M. The emergence of heat and humidity too severe for human tolerance. Sci. Adv. 6, eaaw1838 (2020).

Harnik, N., Messori, G., Caballero, R. & Feldstein, S. B. The Circumglobal North American wave pattern and its relation to cold events in eastern North America. Geophys. Res. Lett. 43 https://doi.org/10.1002/2016gl070760 (2016).

Riboldi, J., Leeding, R., Segalini, A. & Messori, G. MultiplE Large-scale Dynamical Pathways For Pan–Atlantic compound cold and windy extremes. Geophys. Res. Lett. 50 https://doi.org/10.1029/2022gl102528 (2023).

Lu, F. et al. GFDL’s SPEAR seasonal prediction system: initialization and ocean tendency adjustment (OTA) for coupled model predictions. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 12 https://doi.org/10.1029/2020ms002149 (2020).

Chen, M. et al. Assessing objective techniques for gauge-based analyses of global daily precipitation. J. Geophys. Res. 113 https://doi.org/10.1029/2007jd009132 (2008).

Guan, B. & Waliser, D. E. Detection of atmospheric rivers: evaluation and application of an algorithm for global studies. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 120, 12514–12535 (2015).

Tseng, K. C. et al. Are multiseasonal forecasts of atmospheric rivers possible? Geophys. Res. Lett. 48 https://doi.org/10.1029/2021gl094000 (2021).

Clark, J. P., Johnson, N. C., Park, M., Bernardez, M. & Delworth, T. L. Predictable patterns of seasonal atmospheric river variability over North America during winter. Geophys. Res. Lett. 52 https://doi.org/10.1029/2024gl112411 (2025).

Mundhenk, B. D., Barnes, E. A. & Maloney, E. D. All-season climatology and variability of atmospheric river frequencies over the North Pacific. J. Clim. 29, 4885–4903 (2016).

Park, M., Johnson, N. C., Hwang, J. & Jia, L. A hybrid approach for skillful multiseasonal prediction of winter North Pacific blocking. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 7 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-024-00767-2 (2024).

Sousa, P. M., Barriopedro, D., García-Herrera, R., Woollings, T. & Trigo, R. M. A new combined detection algorithm for blocking and subtropical ridges. J. Clim. 34, 7735–7758 (2021).

McKenna, M. & Karamperidou, C. The impacts of El Niño diversity on Northern Hemisphere atmospheric blocking. Geophys. Res. Lett. 50 https://doi.org/10.1029/2023gl104284 (2023).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Drs. Liwei Jia and Donghyuck Yoon for helpful comments on an earlier version of the manuscript. M.P. acknowledges funding under award NA18OAR4320123 and NA22OAR4050663D from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, U.S. Department of Commerce. The statements, findings, conclusions, and recommendations are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration or the U.S. Department of Commerce.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.P. conceived the study, conducted the analysis, and drafted the manuscript. N.C.J. contributed to the interpretation of the results, provided critical feedback throughout the development of the project, and participated in writing the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Park, M., Johnson, N.C. Projected changes in atmospheric pathways of Western North American heatwaves simulated from high-resolution coupled model simulations. npj Clim Atmos Sci (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-01319-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-01319-y