Abstract

The laboratory mouse has been the premier model organism for biomedical research owing to the availability of multiple well-characterized inbred strains, its mammalian physiology and its homozygous genome, and because experiments can be performed under conditions that control environmental variables. Moreover, its genome can be genetically modified to assess the impact of allelic variation on phenotype. Mouse models have been used to discover or test many therapies that are commonly used today. Mouse genetic discoveries are often made using genome-wide association study methods that compare allelic differences in panels of inbred mouse strains with their phenotypic responses. Here we examine changes in the methods used to analyze mouse genetic models of biomedical traits during the twenty-first century. To do this, we first examine where mouse genetics was before the first inflection point, which was just before the revolution in genome sequencing that occurred 20 years ago, and then describe the factors that have accelerated the pace of mouse genetic discovery. We focus on mouse genetic studies that have generated findings that either were translated to humans or could impact clinical medicine or drug development. We next explore how advances in computational capabilities and in DNA sequencing methodology during the past 20 years could enhance the ability of mouse genetics to produce solutions for twenty-first century public-health problems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Mouse models have been used to discover or test many therapies that are commonly used today1. However, before 2002, a mouse genetic discovery project was an arduous task that required 5–10 years to complete, and only a very small subset of the many genetic mapping projects undertaken in different laboratories resulted in the identification of causative genetic factors. The quantitative trait locus (QTL) era for mouse genetics began in 1989 following the publication of a seminal paper2 that described how the genetic basis for a biomedical phenotype of interest could be identified in mice (Fig. 1). At that time, 500 or more progeny from an intercross between high- and low-responder strains had to be generated to produce enough mice to identify genetic loci, and each mouse had to be phenotyped for the trait and genotyped using a set of genotyping markers3. Since meiotic recombination rarely occurs within a specified region after only one or two intercross generations, the initial analysis usually identified a rather large chromosomal region (that is, a QTL interval), which could encompass 25–50% of an entire chromosome4. Therefore, subsequent rounds of interval mapping required the generation and characterization of many hundreds of additional intercross progeny. Then, the chromosomal region had to be sequenced, which was followed by the identification of the candidate genes within the interval before any testing of candidate genes could be undertaken. It is not surprising that the road from phenotype to genetic mapping in mice was described as ‘long and bumpy’ at that time5.

The QTL era began in 1989 after the publication of a seminal publication2 describing how the genetic basis for biomedical phenotypes could be determined by analysis of intercross progeny. Mouse genome-wide transcriptomic profiling was enabled when gene expression microarrays became available in 199520. The pace of mouse genetic discovery increased after a mouse genome reference sequence became available in 20026 and with the development in 2004 of a computational genetic method for analyzing inbred strain GWAS data using available genomic sequence data7. Improvements in next-generation sequencing (200–300 bp; short-read sequencing) enabled the characterization of genomic sequences of multiple inbred strains14, while LRS methods enabled the characterization of strain-specific SVs85. CRISPR, which was first used to engineer the mouse genome in 201386, dramatically improved our ability to assess the impact of genetic changes on phenotype. In 2022, we introduced a GNN-based genetic mapping pipeline for automated GWAS data analysis69. NGS, next generation sequencing.

Factors accelerating genetic discovery

The first twenty-first century inflection point for mouse genetics occurred in 2002, with the release of the genomic sequence for a reference mouse strain (C57BL/6)6. This resource enhanced our ability to analyze mouse genetic models because it enabled the generation of more genotyping markers, allowing candidate genes within an identified chromosomal interval to be quickly inventoried. Nevertheless, since the requirement for generating and characterizing intercross progeny remained, analysis of a mouse genetic model was still a long-term undertaking. However, the mouse genomic sequence had a greater impact than expected because it catalyzed new approaches for analyzing mouse genetic models. For example, in 2004, we demonstrated that causative genetic factors for biomedical traits could be identified by computationally analyzing phenotypic data obtained from a panel of readily available inbred mouse strains along with their genomic sequence data7,8. To perform this type of genome-wide association study (GWAS) analysis, the pattern of physiological, experimentally induced or pathological differences among a selected set of inbred strains could be correlated with the pattern of genetic variation in defined chromosomal regions. Despite its limitations, which include reduced power for analyzing traits controlled by multiple loci that each have a small effect size9, this computational approach (Fig. 1) accelerated the pace of genetic discovery as shown by the publication of a series of papers within 6 years after 2005 where this method was used to identify genetic factors affecting drug metabolism and drug responses10,11,12, susceptibility to fungal13,14 and viral15 infections, and opioid addiction-16 and pain-related17,18,19 responses. Mouse genetic discovery was further facilitated when gene expression microarrays became available in 1995, enabling whole-transcriptome gene expression profiling20. For example, a study identified a murine genetic susceptibility factor for osteoporosis by searching for differentially expressed genes in a target tissue obtained from the two strains that were used to define a QTL interval for bone density21.

Another advance that accelerated mouse genetic discovery was the availability of panels of recombinant inbred (RI) strains, which eliminated the need to generate and analyze intercross progeny for genetic discovery. For example, Nadeau et al. produced a set of 19 chromosome substitution strains (CSSs) by intercrossing A/J and C57BL/6 mice. Each CSS has a single A/J chromosome on an otherwise C57BL/6 genetic background22; if A/J and C57BL/6 mice exhibit a biomedical trait difference, this CSS panel can be scanned to identify genetic susceptibility factors on any autosome. The underlying architecture of this panel (that is, where genetic changes are introduced on an otherwise common genetic background) increases an investigator’s ability to detect and characterize genetic factors23. We used this CSS panel to identify a pharmacogenetic factor that affects susceptibility to the Parkinsonian-like toxicity caused by an anti-psychotic agent; this finding led to the identification of a new approach for preventing this treatment-limiting toxicity24. Similarly, a panel of BXD RI mice (now with 150 lines) produced by intercrossing two strains (C57BL/6 and DBA2) has been used in many murine genetic studies performed over the past 50 years25,26. Over the past 15 years, additional strain panels have been produced by intercrossing multiple parental strains that include the Hybrid Mouse Diversity Panel (HMDP), generated by intercrossing 30 founder strains and RI lines27,28; the Diversity Outbred (DO) mice29, produced from a heterozygous multiway intercross population; and the Collaborative Cross (CC)30, which was produced from 8 founder strains that include 3 wild-derived strains (see refs. 23,31 for reviews). These panels have proven useful for genetic mapping, especially when multiple loci contribute to trait variation, which are the type of traits where conventional murine GWAS have low detection power. As examples of their utility, HMDP mice were used to analyze genetic factors affecting the risk for cocaine abuse32; DO mice were used to characterize genetic factors affecting chromatin structure and pluripotency33; and CC mice were used to map susceptibility to infectious diseases34, cardiovascular disease risk35 and diabetes36. However, these panels have two important limitations. First, the likelihood that a murine GWAS will successfully identify a genetic factor is markedly increased when a biomedical response is measured across a large number (preferably ≥15) of inbred strains. When a small number of strains is evaluated, the actual extent of the phenotypic variation in the mouse population is underestimated9,37. While >450 inbred strains are available38, only a few strains will exhibit an outlier phenotype in most cases. Given that we cannot know in advance which strains will exhibit outlier responses for future twenty-first century public-health problems, outlier responses may not be exhibited by the founder strains that were used to produce the existing RI panels. For example, type 2 diabetes mellitus and obesity are major twenty-first century public-health problems39. Although TallyHo mice provide a murine model for type 2 diabetes mellitus and obesity40,41, they are not among the founder strains for any of the current RI panels. Therefore, a genetic analysis of diabetes-related traits among inbred strains that do not include the TallyHo strain would therefore miss important disease-causing genetic variants. Second, the high cost of maintaining and analyzing the high number of mice in the CC, HMDP or DO panels may also limit their utility. For example, the CC panel includes ~65 strains, and it is recommended to use 200–800 mice from the DO panel to evaluate a genetic trait29.

Why analyze mouse genetic disease models?

It has been argued that most interventions that work in animal models do not replicate in human clinical trials42 and are rarely adopted into clinical practice43, and that data from animal studies cannot be relied upon to predict the results in humans44. However, these views ignore the incredibly high failure rate for compounds during preclinical testing. In addition, ~90% of the compounds in late-stage clinical trials fail for a variety of reasons that include lack of efficacy (57%), lack of funding for trial completion (22%), safety concerns (17%), a flawed study design or poorly chosen statistical endpoints or an underpowered trial45. Given the myriad causes for drug failures during development, it is myopic to blame it all on the animals. Rather than debating the utility of mouse genetic models based upon drug failure rates in clinical testing, we point to several translational successes that we have had with mouse genetic findings. To identify new targets for treating opioid addiction, we analyzed a mouse genetic model of opioid responses across an inbred strain panel. Based upon the genetic finding, we demonstrated that administration of a 5-hydroxytryptamine receptor 3A (5HT3A) antagonist ameliorated opioid responses in mice16, and this effect was confirmed in two human translational studies16,46. Moreover, a multicenter clinical trial demonstrated that a brief period of treatment with a 5HT3A antagonist reduced opioid withdrawal severity compared with placebo in neonates born to mothers that chronically consumed opioids47. As another example, we analyzed a murine genetic model for a drug (haloperidol)-induced parkinsonian-like toxicity and found that allelic variation within a gene encoding murine drug efflux transporter (Abcb5) caused higher brain haloperidol levels in susceptible strains48. A genetic association study in a haloperidol-treated human cohort identified human ABCB5 alleles as susceptibility determinants for this toxicity48. Similarly, we analyzed a murine genetic model for susceptibility to nerve injury-induced chronic pain and identified that the causative genetic factors were single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) alleles of the P2rx7 gene that altered the ability of a purinergic receptor to form pores19. Genetic association analyses performed using two independent human cohorts of patients with chronic pain (post-mastectomy pain and osteoarthritis pain) found SNP alleles in the human homolog (P2XR7, rs7958311), which also affected pore formation and were significantly associated with pain intensity19. An example of ‘reverse translational’ success is provided by our work focusing on a drug whose development was halted because it had an unexpectedly short half-life (10-fold below predicted) in humans during a clinical trial. Our analysis of data obtained from a murine pharmacogenetic model for the drug in vitro biotransformation indicated that allelic variation in the murine Aox1 gene affected the rate of drug biotransformation. We also demonstrated that the human gene homolog (AOX1) catalyzed the rapid metabolism of this drug12. In that case, a murine pharmacogenetic model was used to uncover why a drug that was metabolized by a pathway specifically used by humans, which was not used by other species, failed in a human clinical trial. While not all findings emerging from mouse genetic models will translate to humans, these examples indicate that some will.

An AI-based second inflection point for mouse genetic discovery

A GWAS utilizing inbred mouse strains will identify a true causative genetic variant along with multiple other false positive associations. Many genomic regions have allelic patterns that can correlate with any given response pattern, which can make it difficult to identify the region that contains the true causative genetic factor. This problem results from the fact that the genomes of the inbred strains are mosaics, as they are composed of ~40,000 segments, and each segment is inherited from one of approximately three ancestral founders49. Prior analyses have purported to demonstrate that murine GWAS cannot identify genetic factors for most biomedical traits of interest, due to low power and high false positive rate50,51,52,53. The need to control the false positive rate—by applying a very low cutoff for genetic association P values—leads to a high probability that a murine GWAS will produce a false negative result (that is, reject the true positive association), which explains why others have concluded that murine GWAS cannot work. However, when GWAS results are analyzed as part of an integrated analysis of a biomedical trait, less stringent genetic filtering criterion can be used. Although this approach increases the number of false positives, it ensures that true positives are retained. For example, we have selected causative genetic candidates from among the many genetically correlated genes identified in a murine GWAS by applying orthogonal criteria54,9 that include gene expression and metabolomic data55, curated biological information12 or the genomic regions delimited by prior QTL analyses56,57. This integrated approach seems to be a better method for murine genetic discovery than using a single highly stringent genetic criterion to identify candidate genes9. However, when an investigator is confronted with even a moderately sized list of candidate genes, the amount of effort required to comprehensively evaluate the available literature, and the information contained in multiple other data sources can be overwhelming. In silico prediction programs have been developed to prioritize candidate genetic variants using sequence-based features58,59; and machine learning (ML) methods have been used to assess variant pathogenicity60 or to prioritize causal genes on the basis of human Mendelian disease associations61. A neural network was used to produce a disease impact score for human coding or noncoding variants using epigenomic data62. However, mouse and human GWAS differ in several fundamental ways.

A typical human GWAS includes thousands of individuals with a heterozygous genome collected from a natural population. By contrast, murine GWAS usually analyze less than 30 inbred strains, which have a homozygous genome and do not interbreed; in addition, the environmental variables are tightly controlled in murine experiments. Because of these differences, the genetic effect sizes examined in murine GWAS are much larger than in human GWAS. Hence, the programs that were designed to facilitate the identification of human genetic disease associations have limited ability to identify causal genetic factors for mouse populations63.

Advances in artificial intelligence (AI) and ML are being incorporated into various aspects of human healthcare, including radiology64, cardiology65, oncology66,67 and dermatology68. However, very few AI advances have been used to analyze the model organism that has provided the foundation for many healthcare innovations. While looking for AI-based solutions to accelerate genetic discovery, we hypothesized that we would be able to identify causal genetic factors by assessing the relationship between candidate genes identified by a murine GWAS and a phenotype through the analysis of the biomedical literature and information from the protein–protein interaction (PPI) network and protein sequence. This information would help to determine if a candidate gene or structurally related proteins (for example, orthologs, paralogs or homologs) is within a pathway—or has an interaction partner—that is known to contribute to the phenotype. Based upon these considerations, we developed a graph neural network (GNN)-based fully automated pipeline (GNNHap) that could rapidly analyze mouse genetic model data and identify high-probability causal genetic factors for the analyzed trait69 (Fig. 2). After performing a genetic analysis to identify candidate genes, this pipeline can be used to analyze the information from 29 million published papers, a PPI network and protein sequence features to assess the relationship between the candidate genes and the analyzed phenotype. This pipeline was developed because of the vast amount of mouse phenotypic data that is now available, such as the Mouse Phenome Database (http://phenome.jax.org) that has 18,000 datasets covering a wide range of biomedical responses measured in panels of inbred strains70. We used GNNHap to analyze 1,200 of these datasets and identified known causative genetic factors for several of the phenotypes. Moreover, GNNHap identified novel causative genetic factors for the higher incidence of type 2 diabetes mellitus and obesity and cataract formation in specific strains. These candidate genetic factors were validated by the phenotypes of knockout (KO) mice that had been previously generated for these candidate genes69. Thus, an AI-based pipeline developed in 2022 could analyze mouse genetic data in an automated fashion and identify novel genetic factors. Text mining algorithms have been developed for analyzing biomedical literature (that is, Pubtator71 and Thalia72) for specific concepts and for gene candidate assessment for a specific disease using modified search parameters (that is, addiction73, autism74 and monogenic diseases61,75). However, none of these platforms is GNN-based, and they do not analyze the diverse types of information (such as protein structure and PPI) that are relevant for genetic discovery.

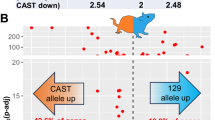

Left: computational genetic mapping identifies candidate genes whose allelic patterns correlate with a phenotypic response pattern exhibited by inbred strains (as determined by the genetic association P value). Middle: the relationship between identified candidate genes and the analyzed phenotype is assessed using a multimodal graph, which displays the relationships between the candidate genes and the analyzed phenotype (based upon analysis of 29 million published papers), and their relationship with other genes that are known to be associated with the phenotype (that is, known disease gene) based on analysis of protein–protein networks and protein structure features. Right: the results can also be displayed on a two-dimensional graph with axes that show the genetic association P value (x axis) and the GNNHap determination of the strength of the relationship between each candidate gene and the phenotype (y axis). Each candidate gene is indicated by a dot, and the red dot is the probable causative gene based upon the strength of its genetic association and relationship with the analyzed phenotype.

What barriers must be overcome to accelerate twenty-first century mouse genetic discovery?

The assembly of the mouse reference genomic sequence in 2002, enabled by advances in sequencing technology, has increased mouse genetic discovery capabilities. Similarly, advances in computational and sequencing capabilities during the past 10 years (Fig. 1) have expanded mouse genetic discovery capabilities. However, efforts must still be applied in three areas to further expand mouse genetic discovery capabilities. First, it is critical to expand the type of genetic variation that can be analyzed. GNNHap was able to identify allelic changes affecting biomedical trait responses among inbred strains69 because it could quickly identify those causing major changes in protein sequences. However, protein coding regions occupy only 1–2% of the genome and most alleles that affect biomedical traits are located within noncoding regions76. For example, all of the 170 human SNPs identified in alleles that were found by a GWAS to alter cardiac repolarization were located in noncoding regions77. Nevertheless, we have a much more limited ability to predict the impact of noncoding alleles than we have for coding SNPs. To obtain a more complete picture of the genetic variants affecting biomedical responses in mouse genetic models, we must be able to computationally assess the potential effect of noncoding alleles that are identified by GWAS analysis, without the need for experimental validation of allelic effects. AI could be used to do this, by employing a ‘transfer learning strategy’. This strategy would allow the development of ML models for evaluating mouse noncoding alleles using ML models that were originally trained on the many human epigenomic datasets that annotate enhancers, promoters and binding sites for transcription factors and RNA binding proteins. A transfer learning strategy would enable an ML model to be fine-tuned on a small scale using available murine datasets, and it could then be used analyze the impact that alleles in noncoding regions of the murine genome have on chromatin structure and gene expression. For example, one ML-based analysis algorithm (DeepSEA78) was trained using >2,000 human epigenomic datasets generated from >200 cell types. DeepSEA used the reference human genomic DNA sequence (without allelic variation) as the only input to predict with single-nucleotide sensitivity the effects of sequence alterations on chromatin structure. However, DeepSEA and all available ML methods have limitations that arise from their reliance upon the datasets used for training the model. Since the activity of regulatory elements is highly dependent upon the cellular context79,80 and it is not possible to analyze genome-wide profiles for all binding factors in all cell types and tissues, the training sets do not enable noncoding variant effects to be accurately predicted for all cell types or tissues. However, advanced ML models, which were trained by evaluation of large-scale epigenomic datasets, could improve our ability to do this81.

Second, we must expand the types of genetic variants that are analyzed; at present, mouse genetic analysis relies only on SNP alleles. Recently developed long-read sequencing (LRS) methods that can analyze >15 kb DNA segments82,83 have enabled the evaluation of previously uncharacterized structural variants (SVs), which are genomic alterations >50 bp in size. LRS has been used to characterize human genetic disease mechanisms that could not otherwise be identified82,83,84. We previously used short-range sequencing (200–300 bp segments) of whole-genome sequence data to produce a 22 million SNP database with alleles covering 53 mouse inbred strains. More recently, we used LRS to evaluate SVs in six mouse inbred strains and found that SVs are very abundant in their genomes (4.8 per gene), which indicates that SVs are likely to impact genetic traits85. We also found that we cannot accurately infer whether SVs are present using conventional short-range sequence, even when nearby SNP alleles are known. The SVs identified using short-range sequencing accounted for only 25% of those that were identified by LRS analysis85. Hence, LRS must be used to produce a more complete map of the genetic variation pattern among the inbred strains, which will enable the characterization of the genetic basis of phenotypes that are regulated by previously unrecognized genetic variants.

Third, since mouse genetic discovery is critically dependent upon the ability to rapidly assess whether a candidate gene impacts a phenotype, we must develop methods that accelerate candidate gene validation. Clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)-mediated mouse genome engineering, which was initially used in 201386, has improved our ability to assess the impact of genetic changes on mouse phenotypes. However, it is just not feasible (from a time or cost perspective) for a laboratory to produce mouse KO or knockin lines for every candidate gene. This limitation is especially true when candidate gene identification is facilitated by AI-based analysis of GWAS data. However, the merger of reverse genetics (that is, when analyzing the phenotypes that appear in response to specific genome alterations) with forward genetics (as occurs in a GWAS, when analyzing phenotypes to identify their genetic basis) could accelerate mouse genetic discovery. Merging these two approaches has been made possible by the efforts of the International Mouse Phenotyping Consortium (IMPC), an international research infrastructure that has the goal of generating KO lines for every mouse gene. The IMPC has already generated 8,200 gene KO lines (all on an isogenic C57BL/6N background) and has conducted large-scale screening for >500 biomedical phenotypes at 10 centers87,88,89. For example, IMPC has analyzed 3,894 single-gene KO lines for cardiac abnormalities90. They identified cardiac abnormalities in 705 KO lines, and 75% of those genes were not previously associated with cardiac disease91. Similarly, analysis of hearing in 3,006 KO mouse lines identified 67 genes that caused hearing loss, 78% (n = 52) of which had not been previously associated with hearing loss92. Therefore, as an example, an investigator who has identified a list of candidate genes from a murine GWAS examining a hearing or cardiac phenotype could examine the IMPC database to determine if a KO line for any of the candidate genes had hearing or cardiac abnormalities. As more and more KO lines and phenotypes are examined, the utility of the IMPC KO database for candidate gene validation will increase. An investigator must keep in mind the possibility that the effect of a gene KO may be different from that of an allelic effect, and the phenotype may be dependent upon the genetic background of the mouse. Another option is to determine whether alleles within the human homologs of mouse candidate genes were associated with a related phenotype in a human GWAS. The National Human Genome Research Institute–European Bioinformatics Institute (NHGRI-EBI) GWAS catalog could be used for this purpose because it is a rapidly growing and highly curated collection of the results obtained from >40,000 GWAS datasets presented in ∼600 peer-reviewed publications that cover 3,500 traits93. In this idyllic world (Fig. 3), the phenotypic data from a murine GWAS for a biomedical trait could be analyzed in an automated fashion using an AI-based program (such as GNNHap) that could also scan the IMPC phenotypic or human GWAS databases for candidate gene validation. Given the computational and DNA sequencing capabilities available, we are not far from having this approach become the standard method for analysis of mouse genetic models. This computational framework will greatly improve our mouse genetic discovery capabilities and might provide new solutions for twenty-first century public-health problems.

The pipeline analyzes GWAS data and identifies candidate genes whose allelic pattern correlates with the responses exhibited by the inbred strains. Then, it builds a knowledge graph for the candidate genes based upon analysis of gene–phenotype (φ) associations in the published literature, a PPI network and protein structural features. Analysis of this graph identifies the candidate genes that are most strongly related to the analyzed phenotype (φ). The effect of a KO of a prioritized candidate gene on the analyzed phenotype can then be assessed by examining the IMPC database. This database indicates if a phenotype was altered in an IMPC gene KO line through the P value determined by comparing the KO line’s phenotype with that of the wild-type strain.

References

Nadeau, J. H. & Auwerx, J. The virtuous cycle of human genetics and mouse models in drug discovery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 18, 255–272 (2019).

Lander, E. S. & Botstein, D. Mapping Mendelian factors underlying quantitative traits using RFLP linkage maps. Genetics 121, 185–199 (1989).

Rhodes, M. et al. High-throughput microsatellite analysis using fluorescent dUTPs for high-resolution genetic mapping of the mouse genome. Genome Res. 7, 81–85 (1997).

Darvasi, A. & Soller, M. A simple method to calculate resolving power and confidence interval of QTL map location. Behav. Genet. 27, 125–132 (1997).

Nadeau, J. H. & Frankel, W. N. The roads from phenotypic variation to gene discovery: mutagenesis versus QTLs. Nat. Genet. 25, 381–384 (2000).

Waterston, R. H. et al. Initial sequencing and comparative analysis of the mouse genome. Nature 420, 520–562 (2002).

Liao, G. et al. In silico genetics: identification of a functional element regulating H2-Ea gene expression. Science 306, 690–695 (2004).

Wang, J. & Peltz, G. in Computational Genetics and Genomics: New Tools for Understanding Disease (ed. Peltz, G.) 51–70 (Humana Press, 2005).

Zheng, M., Dill, D. & Peltz, G. A better prognosis for genetic association studies in mice. Trends Genet. 28, 62–69 (2012).

Guo, Y. Y. et al. In silico pharmacogenetics: warfarin metabolism. Nat. Biotechnol. 24, 531–536 (2006).

Guo, Y. Y. et al. In vitro and in silico pharmacogenetic analysis in mice. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 104, 17735–17740 (2007).

Zhang, X. et al. In silico and in vitro pharmacogenetics: aldehyde oxidase rapidly metabolizes a p38 kinase inhibitor. Pharmacogenomics J. 11, 15–24 (2011).

Zaas, A. K. et al. Plasminogen alleles influence susceptibility to invasive aspergillosis. PLoS Genet. 4, e1000101 (2008).

Peltz, G. et al. Next-generation computational genetic analysis: multiple complement alleles control survival after Candida albicans. Infect. Infect. Immun. 79, 4472–4479 (2011).

Tregoning, J. S. et al. Genetic susceptibility to the delayed sequelae of RSV infection is MHC-dependent, but modified by other genetic loci. J. Immunol. 185, 5384–5391 (2010).

Chu, L. F. et al. From mouse to man: the 5-HT3 receptor modulates physical dependence on opioid narcotics. Pharmacogenet. Genomics 19, 193–205 (2009).

Li, X. et al. Expression genetics identifies spinal mechanisms supporting formalin late phase behaviors. Mol. Pain 6, 11 (2010).

Hu, Y. et al. The role of IL-1 in wound biology part I: murine in silico and in vitro experimental analysis. Anesth. Analg. 111, 1525–1533 (2010).

Sorge, R. E. et al. Genetically determined P2X7 receptor pore formation regulates variability in chronic pain sensitivity. Nat. Med. 18, 595–599 (2012).

Schena, M., Shalon, D., Davis, R. W. & Brown, P. O. Quantitative monitoring of gene expression patterns with a complementary DNA microarray. Science 270, 467–470 (1995).

Klein, R. F. et al. Regulation of bone mass in mice by the lipoxygenase gene Alox15. Science 303, 229–232 (2004).

Nadeau, J. H., Singer, J. B., Matin, A. & Lander, E. S. Analysing complex genetic traits with chromosome substitution strains. Nat. Genet. 24, 221–225 (2000).

Buchner, D. A. & Nadeau, J. H. Contrasting genetic architectures in different mouse reference populations used for studying complex traits. Genome Res. 25, 775–791 (2015).

Zhang, H. et al. A pharmacogenetic discovery: cystamine protects against haloperidol-induced toxicity and ischemic brain injury. Genetics 203, 599–609 (2016).

Belknap, J. K. & Crabbe, J. C. Chromosome mapping of gene loci affecting morphine and amphetamine responses in BXD recombinant inbred mice. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 654, 311–323 (1992).

Taylor, B. A., Heiniger, H. J. & Meier, H. Genetic analysis of resistance to cadmium-induced testicular damage in mice. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 143, 629–633 (1973).

Bennett, B. J. et al. A high-resolution association mapping panel for the dissection of complex traits in mice. Genome Res. 20, 281–290 (2010).

Ghazalpour, A. et al. Hybrid Mouse Diversity Panel: a panel of inbred mouse strains suitable for analysis of complex genetic traits. Mamm. Genome 23, 680–692 (2012).

Churchill, G. A., Gatti, D. M., Munger, S. C. & Svenson, K. L. The Diversity Outbred mouse population. Mamm. Genome 23, 713–718 (2012).

Chesler, E. J. et al. The Collaborative Cross at Oak Ridge National Laboratory: developing a powerful resource for systems genetics. Mamm. Genome 19, 382–389 (2008).

Swanzey, E., O’Connor, C. & Reinholdt, L. G. Mouse genetic reference populations: cellular platforms for integrative systems genetics. Trends Genet. 37, 251–265 (2021).

Bagley, J. R., Khan, A. H., Smith, D. J. & Jentsch, J. D. Extreme phenotypic diversity in operant response to intravenous cocaine or saline infusion in the Hybrid Mouse Diversity Panel. Addict. Biol. 27, e13162 (2022).

Skelly, D. A. et al. Mapping the effects of genetic variation on chromatin state and gene expression reveals loci that control ground state pluripotency. Cell Stem Cell 27, 459–469 e458 (2020).

Abu Toamih Atamni, H., Nashef, A. & Iraqi, F. A. The Collaborative Cross mouse model for dissecting genetic susceptibility to infectious diseases. Mamm. Genome 29, 471–487 (2018).

Salimova, E. et al. Variable outcomes of human heart attack recapitulated in genetically diverse mice. NPJ Regen. Med. 4, 5 (2019).

Abu-Toamih-Atamni, H. J. et al. Mapping novel QTL and fine mapping of previously identified QTL associated with glucose tolerance using the collaborative cross mice. Mamm. Genome 35, 31–55 (2024).

Wang, J., Liao, G., Usuka, J. & Peltz, G. Computational genetics: from mouse to man? Trends Genet. 21, 526–532 (2005).

Beck, J. A. et al. Genealogies of mouse inbred strains. Nat. Genet. 24, 23–25 (2000).

Boles, A., Kandimalla, R. & Reddy, P. H. Dynamics of diabetes and obesity: epidemiological perspective. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 1863, 1026–1036 (2017).

Kim, J. H. et al. Genetic analysis of a new mouse model for non-insulin-dependent diabetes. Genomics 74, 273–286 (2001).

Kim, J. H. & Saxton, A. M. The TALLYHO mouse as a model of human type 2 diabetes. Methods Mol. Biol. 933, 75–87 (2012).

Hackam, D. G. & Redelmeier, D. A. Translation of research evidence from animals to humans. JAMA 296, 1731–1732 (2006).

Pound, P. & Bracken, M. B. Is animal research sufficiently evidence based to be a cornerstone of biomedical research? BMJ 348, g3387 (2014).

Ioannidis, J. P. Extrapolating from animals to humans. Sci. Transl. Med. 4, 151ps115 (2012).

Fogel, D. B. Factors associated with clinical trials that fail and opportunities for improving the likelihood of success: a review. Contemp. Clin. Trials Commun. 11, 156–164 (2018).

Erlendson, M. J. et al. Palonosetron and hydroxyzine pre-treatment reduces the objective signs of experimentally-induced acute opioid withdrawal in humans: a double-blinded, randomized, placebo-controlled crossover study. Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abuse 43, 78–86 (2017).

Peltz, G. et al. Ondansetron to reduce neonatal opioid withdrawal severity a randomized clinical trial. J. Perinatol. 43, 271–276 (2023).

Zheng, M. et al. The role of Abcb5 alleles in susceptibility to haloperidol-induced toxicity in mice and humans. PLoS Med. 12, e1001782 (2015).

Frazer, K. A. et al. A sequence-based variation map of 8.27 million SNPs in inbred mouse strains. Nature 448, 1050–1053 (2007).

Flint, J., Valdar, W., Shifman, S. & Mott, R. Strategies for mapping and cloning quantitative trait genes in rodents. Nat. Rev. Genet 6, 271–286 (2005).

Payseur, B. A. & Place, M. Prospects for association mapping in classical inbred mouse strains. Genetics 175, 1999–2008 (2007).

Su, W. L. et al. Assessing the prospects of genome-wide association studies performed in inbred mice. Mamm. Genome 21, 143–152 (2010).

Sul, J. H., Martin, L. S. & Eskin, E. Population structure in genetic studies: confounding factors and mixed models. PLoS Genet. 14, e1007309 (2018).

Zheng, M., Shafer, S. S., Liao, G., Liu, H.-H. & Peltz, G. Computational genetic mapping in mice: ‘the ship has sailed’. Sci. Transl. Med. 1, 3ps4 (2009).

Liu, H.-H. et al. An integrative genomic analysis identifies Bhmt2 as a diet-dependent genetic factor protecting against acetaminophen-induced liver toxicity. Genome Res. 20, 28–35 (2010).

Smith, S. B. et al. Quantitative trait locus and computational mapping identifies Kcnj9 (GIRK3) as a candidate gene affecting analgesia from multiple drug classes. Pharmacogenet. Genomics 18, 231–241 (2008).

LaCroix-Fralish, M. L. et al. The β3 subunit of the Na+,K+-ATPase affects pain sensitivity. Pain 144, 294–302 (2009).

Hu, J. & Ng, P. C. Predicting the effects of frameshifting indels. Genome Biol. 13, R9 (2012).

Rogers, M. F. et al. FATHMM-XF: accurate prediction of pathogenic point mutations via extended features. Bioinformatics 34, 511–513 (2018).

Jagadeesh, K. A. et al. M-CAP eliminates a majority of variants of uncertain significance in clinical exomes at high sensitivity. Nat. Genet. 48, 1581–1586 (2016).

Birgmeier, J. et al. AMELIE3: fully automated Mendelian patient reanalysis at under 1 alert per patient per year. Preprint at medRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.12.29.20248974 (2021).

Zhou, J. et al. Whole-genome deep-learning analysis identifies contribution of noncoding mutations to autism risk. Nat. Genet. 51, 973–980 (2019).

Wang, M., Fang, Z., Yoo, B., Bejerano, G. & Peltz, G. The effect of population structure on murine genome-wide association studies. Front. Genet. 12, 745361 (2021).

Lee, S. & Summers, R. M. Clinical artificial intelligence applications in radiology: chest and abdomen. Radiol. Clin. North Am. 59, 987–1002 (2021).

Kodera, S., Akazawa, H., Morita, H. & Komuro, I. Prospects for cardiovascular medicine using artificial intelligence. J. Cardiol. 79, 319–325 (2022).

Vobugari, N. et al. Advancements in oncology with artificial intelligence—a review article. Cancers 14, 1349 (2022).

Bera, K., Braman, N., Gupta, A., Velcheti, V. & Madabhushi, A. Predicting cancer outcomes with radiomics and artificial intelligence in radiology. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 19, 132–146 (2022).

Zakhem, G. A., Fakhoury, J. W., Motosko, C. C. & Ho, R. S. Characterizing the role of dermatologists in developing artificial intelligence for assessment of skin cancer. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 85, 1544–1556 (2021).

Fang, Z. & Peltz, G. An automated multi-modal graph-based pipeline for mouse genetic discovery. Bioinformatics 38, 3385–3394 (2022).

Grubb, S. C., Bult, C. J. & Bogue, M. A. Mouse phenome database. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, D825–834 (2014).

Wei, C. H., Allot, A., Leaman, R. & Lu, Z. PubTator central: automated concept annotation for biomedical full text articles. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, W587–W593 (2019).

Soto, A. J., Przybyla, P. & Ananiadou, S. Thalia: semantic search engine for biomedical abstracts. Bioinformatics 35, 1799–1801 (2019).

Gunturkun, M. H. et al. GeneCup: mining PubMed and GWAS catalog for gene–keyword relationships. G3 12, jkac059 (2022).

Li, S. et al. Text mining of gene–phenotype associations reveals new phenotypic profiles of autism-associated genes. Sci. Rep. 11, 15269 (2021).

Birgmeier, J. et al. AMELIE speeds Mendelian diagnosis by matching patient phenotype and genotype to primary literature. Sci. Transl. Med. 12, eaau9113 (2020).

Zhang, F. & Lupski, J. R. Non-coding genetic variants in human disease. Hum. Mol. Genet. 24, R102–110 (2015).

Kapoor, A. et al. An enhancer polymorphism at the cardiomyocyte intercalated disc protein NOS1AP locus is a major regulator of the QT interval. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 94, 854–869 (2014).

Zhou, J. & Troyanskaya, O. G. Predicting effects of noncoding variants with deep learning-based sequence model. Nat. Methods 12, 931–934 (2015).

Andersson, R. & Sandelin, A. Determinants of enhancer and promoter activities of regulatory elements. Nat. Rev. Genet. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41576-019-0173-8 (2019).

Shlyueva, D., Stampfel, G. & Stark, A. Transcriptional enhancers: from properties to genome-wide predictions. Nat. Rev. Genet. 15, 272–286 (2014).

Wong, A. K., Sealfon, R. S. G., Theesfeld, C. L. & Troyanskaya, O. G. Decoding disease: from genomes to networks to phenotypes. Nat. Rev. Genet. 22, 774–790 (2021).

van Dijk, E. L., Jaszczyszyn, Y., Naquin, D. & Thermes, C. The third revolution in sequencing technology. Trends Genet. 34, 666–681 (2018).

Logsdon, G. A., Vollger, M. R. & Eichler, E. E. Long-read human genome sequencing and its applications. Nat. Rev. Genet. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41576-020-0236-x (2020).

Mantere, T., Kersten, S. & Hoischen, A. Long-read sequencing emerging in medical genetics. Front. Genet. 10, 426 (2019).

Arslan, A. et al. Analysis of structural variation among inbred mouse strains. BMC Genomics 24, 97–109 (2023).

Yang, H. et al. One-step generation of mice carrying reporter and conditional alleles by CRISPR/Cas-mediated genome engineering. Cell 154, 1370–1379 (2013).

Peterson, K. A. & Murray, S. A. Progress towards completing the mutant mouse null resource. Mamm. Genome 33, 123–134 (2022).

Birling, M. C. et al. A resource of targeted mutant mouse lines for 5,061 genes. Nat. Genet. 53, 416–419 (2021).

Meehan, T. F. et al. Disease model discovery from 3,328 gene knockouts by The International Mouse Phenotyping Consortium. Nat. Genet. 49, 1231–1238 (2017).

Spielmann, N., Miller, G. & Oprea, T. I. Extensive identification of genes involved in congenital and structural heart disorders and cardiomyopathy. Nat. Cardiovasc. Res. 1, 157–173 (2022).

Swan, A. L. et al. Mouse mutant phenotyping at scale reveals novel genes controlling bone mineral density. PLoS Genet. 16, e1009190 (2020).

Bowl, M. R. et al. A large scale hearing loss screen reveals an extensive unexplored genetic landscape for auditory dysfunction. Nat. Commun. 8, 886 (2017).

Sollis, E. et al. The NHGRI-EBI GWAS catalog: knowledgebase and deposition resource. Nucleic Acids Res. 51, D977–D985 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH awards (1R01DC021133 and 1 R24 OD035408) to G.P. The funder had no role in the writing of this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Lab Animal thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fang, Z., Peltz, G. Twenty-first century mouse genetics is again at an inflection point. Lab Anim 54, 9–15 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41684-024-01491-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41684-024-01491-3