Abstract

Precise survival risk stratification is crucial for personalized therapy in bladder cancer (BCa). This study developed and validated an end-to-end deep learning system using histological slides to predict overall survival (OS) risk in BCa patients. We employed the BlaPaSeg tile classifier to generate tissue probability heatmaps and segmentation maps, trained two prognostic networks, MacroVisionNet and UniVisionNet, and explored six potential BCa prognostic biomarkers. Across all cohorts, the AUC for BlaPaSeg ranged from 0.9906 to 0.9945, while the C-index varied from 0.655 to 0.834 for MacroVisionNet and 0.661 to 0.853 for UniVisionNet. After covariate adjustment, the hazard ratio (HR) values for high-risk groups were 1.97 to 5.06 in MacroVisionNet and 2.13 to 4.01 in UniVisionNet. The high-risk Coloc (Tumor Co-localization score) and IMTS (Integrated Muscle Tumor Score) groups illustrated a higher death risk with HR values from 1.41 to 10.16. The system improves BCa survival prediction and supports refined patient management.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Bladder cancer (BCa) is one of the most common epithelial tumors in the urinary tract1,2. Despite advancements in the treatment for BCa through various therapeutic approaches like intravesical chemotherapy, immunotherapy, transurethral resection of bladder tumor (TURBT), and radical cystectomy, the five-year survival rates for BCa patients remain fairly low, with significant variations among individuals. For patients with non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC), the five-year survival rate is estimated to be around 90%3,4. Nevertheless, individuals diagnosed with muscle-invasive bladder cancer (MIBC) experience a significantly reduced five-year survival probability due to the deeper tumor infiltrating in the layers of bladder5,6.

The application of whole slide images (WSIs) is essential for accurate pathological evaluation in tumor categorization and staging. However, traditional prognostic methods like the TNM staging system, fall short in capturing the complex biological characteristics of bladder tumors, frequently leading to suboptimal therapeutic approaches7. Meanwhile, the variability and subjectivity inherent in manual pathological assessments, which rely on visible morphological features in WSIs, further complicate the accurate prognosis and treatment process8,9. This subjectivity can lead to inconsistencies in diagnosis and treatment decisions, which illustrates the necessity for more objective and standardized approaches10.

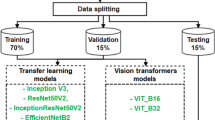

Recent advances in computational pathology have introduced promising alternatives to traditional methods. Deep learning algorithms have emerged as highly effective tools for improving the accuracy of diagnosis and prognosis prediction11,12,13. However, challenges in interpretability and generalizability often limit the application of these technologies in clinical practice, which are essential considerations for achieving widespread acceptability in the medical field14. Currently, numerous studies employ multiple-instance learning methods on WSIs to extract microscopic patch features for diagnosis and prognosis risk prediction15,16,17,18. Nevertheless, feature-based models sacrifice crucial tissue distribution information, which in turn limits the model’s interpretability19. Prior studies have demonstrated that macroscopic tissue spatial distributions not only enhance prognostic accuracy but also hold potential to find new tissue biomarkers20,21. Building upon this evidence, our study aimed to construct a novel deep learning system that integrates interpretable artificial intelligence (AI) technology with a comprehensive understanding of tissue distribution information in pathology slides. First, we employed the BlaPaSeg tile classification network based on the ResNeXt50 architecture to generate multi-class tissue probability heatmaps and segmentation maps from WSIs. After that, we developed two complementary prognostic networks: MacroVisionNet and UniVisionNet. MacroVisionNet focuses on analyzing broad tissue distribution patterns within the probability heatmaps to identify macro-level prognostic features essential for patient survival. In contrast, UniVisionNet was designed to integrate these macro-level prognostic features with micro-level tumor patch features generated by a self-supervised network, capturing both global and localized tissue characteristics. This deep learning-based prognostic framework was validated across multiple medical institutions and The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) cohort. In addition, we explored and validated several potential prognostic biomarkers based on the tissue segmentation maps and MacroVisionNet attribution heatmap. Finally, an integrated pathology-based prognostic AI system was created to enhance its application in clinical settings

Results

Baseline characteristics

In this retrospective, multicenter, prognostic study, 1108 patients with BCa were recruited from three major medical institutions: the First Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing Medical University [CMUFH], the Second Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing Medical University [CMUSH], and the Yongchuan Hospital of Chongqing Medical University [YCH]. Randomly selected by a 7:3 ratio, 621 patients from CMUFH were included in the training dataset, and 266 patients from CMUFH were incorporated in the validation dataset during the development of the prognostic system (1 December 2012 to 30 December 2023). The external validation datasets included 113 patients from CMUSH (1 May 2013 to 30 December 2023), 108 patients from YCH (2 January 2016 to 30 December 2023), and 375 patients from the TCGA-BLCA dataset. The median follow-up time with interquartile range (IQR) was 30.5 (12.7–66.4) months for the CMUFH training group, 29.5 (13.0–58.4) months for the CMUFH validation cohort, 15.3 (5.3–37.4) months for the CMUSH validation cohort, 23.1 (11.2–44.9) months for the YCH validation cohort, and 18.0 (11.1–31.5) months for the TCGA validation cohort (Table 1).

Performance of BlaPaSeg, MacroVisionNet, and UniVisionNet across enrolled cohorts

The Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve shows the AUC of the BlaPaSeg tile classification network varied from 0.9906 (95% CI: 0.9899–0.9913) to 0.9945 (0.9939–0.9950) in the training, validation, and external validation cohorts (Fig. 1A). The detailed tissue patch classification results for each cohort are displayed in the Supplementary Fig. 2. After training the BlaPaSeg network, we applied it to infer WSIs, generating tissue probability heatmaps and tissue segmentation maps. Building on these results, we trained and validated the MacroVisionNet and UniVisionNet. For the CMUFH training cohort, the C-index for MacroVisionNet reached 0.834 (0.782–0.879) and the C-index for UniVisionNet reached 0.853 (0.809–0.895). For the CMUFH validation cohort, the C-index for MacroVisionNet achieved 0.787 (0.717–0.855) and the C-index for UniVisionNet achieved 0.797 (0.730–0.862). To further explore the performance of MacroVisionNet and UniVisionNet, we conducted verification across three external validation cohorts. The CMUSH cohort achieved a C-index of 0.788 (0.693–0.881) for MacroVisionNet and a C-index of 0.811 (0.731–0.893) for UniVisionNet. For the YCH cohort, the C-index for MacroVisionNet reached 0.752 (0.557–0.944) and the C-index for UniVisionNet reached 0.820 (0.696–0.954). In the TCGA cohort, MacroVisionNet demonstrated moderate performance with a C-index of 0.655 (0.600–0.705), and UniVisionNet reached 0.661 (0.612–0.708). Figure 1B, C presents the time-dependent area under the curves for MacroVisionNet and UniVisionNet in each cohort.

Area under the receiver operator characteristic curve of BlaPaseg (A). Time-dependent area under the curves of MacroVisionNet (B) and UniVisionNet (C). AUC Area under the receiver operator characteristic curve, CMUFH The First Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing Medical University, CMUSH The Second Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing Medical University, YCH Yongchuan Hospital of Chongqing Medical University, TCGA The Cancer Genome Atlas set.

Risk score cutoffs and survival analysis in multiple cohorts

Based on the maximally selected rank statistic calculated in the CMUFH training cohort, the cutoff of the MacroVisionNet risk score is 1.93, and the cutoff of the UniVisionNet risk score is 3.34. In both MacroVisionNet and UniVisionNet, patients in the high-risk groups experienced poorer survival outcomes compared to those in the low-risk groups. Specifically, the hazard ratios (HR) value of the MacroVisionNet high-risk group for OS was 16.12 (95% CI 10.45–24.87; p < 0.001) in the CMUFH training cohort, 7.58 (4.16–13.81; p < 0.001) in the CMUFH validation cohort, 9.39 (4.04–21.84; p < 0.001) in the CMUSH cohort, 18.58 (6.08–56.79; p < 0.001) in the YCH cohort, and 2.18 (1.61–2.96; p < 0.001) in the TCGA cohort. The HR value of the UniVisionNet high-risk group for OS was 14.74 (95% CI 9.56–22.70; p < 0.001) in the CMUFH training cohort, 6.76 (3.83–11.91; p < 0.001) in the CMUFH validation cohort, 10.59 (4.50–24.93; p < 0.001) in the CMUSH cohort, 18.21(5.62–59.03; p < 0.001) in the YCH cohort, and 2.20(1.59–3.03; p < 0.001) in the TCGA cohort. In the Kaplan-Meier analysis, the deep-learning risk score effectively stratified the OS risk for BCa patients across all enrolled cohorts (Figs. 2, 3). Detailed HR risk results and Kaplan-Meier curve results for each subgroup within enrolled cohorts are displayed in Supplementary Figs. 7–16.

Kaplan-Meier curves for overall survival are presented in the training set (A) and validation set (B). Forest plot for multivariable Cox regression analysis in the training set (C) and validation set (D). CMUFH The First Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing Medical University. MacroVisionNet macro vision network. UniVisionNet=unified vision network.

Kaplan-Meier curves for overall survival are presented in the CMUSH cohort, (A) YCH cohort (B), and TCGA cohort (C). Forest plot for multivariable Cox regression analysis in the CMUSH-YCH cohort, (D) and TCGA cohort (E). CMUSH The Second Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing Medical University. YCH Yongchuan Hospital of Chongqing Medical University. TCGA The Cancer Genome Atlas set. MacroVisionNet macro vision network. UniVisionNet unified vision network.

Multivariable cox regression analysis for prognostic significance

We conducted a multivariable Cox regression analysis to evaluate the prognostic significance of the risk groups, adjusting for established prognostic variables (Figs. 2, 3). In the CMUFH cohort, after adjusting for covariates including age, gender, T stage, N stage, and tumor grade, the HR value of the MacroVisionNet risk group for OS was 5.06(2.44–10.49; p < 0.001) in the training set and 4.54(1.45–14.18; p = 0.009) in the validation set. Similarly, the HR value of the UniVisionNet risk group was 4.01(1.94–8.27; p < 0.001) in the training set and 3.40(1.14–10.12; p = 0.028) in the validation set. In the TCGA cohort, the adjusted HR value in the MacroVisionNet risk group was 1.97(1.41–2.76; p < 0.001), and the adjusted HR value in the UniVisionNet risk group was 2.13(1.49–3.04; p < 0.001). To incorporate additional covariates, we performed a multivariate analysis on the combined CMUSH and YCH cohort. After adjusting for age, gender, and T stage, the HR value for OS in the MacroVisionNet risk group was 3.69 (1.69–8.06; p = 0.001), while the UniVisionNet risk group was 4.26 (95% CI 1.96–9.27; p < 0.001). The deep learning-based risk score consistently demonstrated robustness across all cohorts (Table 2). Following the multivariable Cox regression analysis, we constructed two nomograms that integrated the prediction scores with clinical information. Detailed nomogram presentations, ROC plot, and calibration plot are displayed in Supplementary Figs. 19–22.

AI inspired prognostic biomarker exploration

To interpret and explore which areas largely contribute to the predicted risk score, we adopted the attribution method to identify the specific attention areas inside MacroVisionNet. We represented attribution information as a two-dimensional heatmap, overlaying it with the tissue segmentation map for enhanced visualization and comprehension. For the high-risk group (Supplementary Figs. 3, 4), the attribution heatmap showed that MacroVisionNet focused on the boundary areas between tumor and muscle tissues. In contrast, for the low-risk group, the attribution heatmap indicated that MacroVisionNet focused on areas enriched with lymphocytes. Inspired by attribution information in the segmentation map, we have proposed and validated six potential quantitative prognostic biomarkers for bladder tumors. The six potential tumor prognostic biomarkers are: Integrated Muscle Tumor Score (IMTS), Tumor Muscle Infiltration Fraction (TIM), Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs), Tumor Fraction Score (TFS), Inflammation Fraction Score (IFS), and Tumor Co-localization Score (Coloc). To quantify the distribution differences of tumors across tissues, we utilized TIM, Coloc, TFS, and IMTS, while IFS and TILs were employed to measure the distribution of lymphocytes within the tissues. The detailed definitions of these prognostic biomarkers are provided in “Methods“ section. To further validate whether the spatial distribution of tumors in specific tissues is associated with prognosis, we conducted Cox analysis and Kaplan-Meier analysis for each biomarker. The HR value of the Coloc high-risk group for OS was 5.42 (95% CI 3.42–8.58; p < 0.001) in the CMUFH training cohort, 5.92 (3.29–10.65; p < 0.001) in the CMUFH validation cohort, 5.09 (1.87–13.82; p = 0.001) in the CMUSH cohort, 3.37 (1.06–10.70; p = 0.039) in the YCH cohort, and 1.41 (1.04–1.92; p = 0.028) in the TCGA cohort. The HRs of the IMTS high-risk group for OS were 3.94 (95% CI 2.41–6.44; p < 0.001) in the CMUFH training cohort, 4.21 (2.04–8.69; p < 0.001) in the CMUFH validation cohort, 10.16 (1.29–80.33; p = 0.027) in the CMUSH cohort, 3.60 (1.14–11.38; p = 0.029) in the YCH cohort, and 1.46 (1.07–1.98; p = 0.016) in the TCGA cohort (Supplementary Fig. 5). Both IMTS and Coloc demonstrated statistical significance across all cohorts. After adjusting for age and gender covariates, the multivariate Cox analysis also confirmed that IMTS and Coloc remained statistically significant (Supplementary Table 1). This demonstrated that the infiltration distribution of tumors in muscle tissues on WSIs is related to BCa prognosis. The Kaplan-Meier curves, HR values, and the distribution differences between the high-risk and low-risk groups for each potential biomarker in MacroVisionNet are presented in Supplementary Figs. 5, 6.

Associations between biological markers, immune infiltration, and UniVisionNet risk scores

To further explore the biological associations in UniVisionNet groups, we utilized biomolecular information from the TCGA dataset. We identified a total of 1076 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between the high-risk and low-risk groups. The GO bubble chart revealed the top 10 associated significant differences in the molecular functions, cellular components, and biological processes. These differences included epidermis development, serine-type peptidase activity, and intermediate filament organization (Supplementary Fig. 17). Immune cell type-specific analysis revealed significant differences in fourteen immune cell types, including CD4 T cells (p = 0.043), CD8 T cells (p = 0.043), neutrophil cells (p = 0.006), and macrophage cells (p < 0.001). The heatmaps present the distribution differences of all immune cells between the high-risk and low-risk groups based on the CIBERSORT and TIMER algorithms (Supplementary Fig. 18). These findings indicate a relationship between the UniVisionNet risk scores and cellular tissue information, enhancing the model’s interpretability.

Discussion

Accurate prediction of OS risk is beneficial for risk stratification and treatment selection for BCa patients. In this study, we developed and validated a deep learning-based prognostic system for BCa risk stratification. The reliability and applicability of the prognostic system are determined by the following key factors: (1) It included more comprehensive data from 887 BCa patients in CMUFH for model training and internal validation; (2) It demonstrated robust predictive performance across multiple large medical institutions and TCGA-BLCA datasets originated from different countries and ethnicities; (3) It incorporated the macro vision and micro vision information in WSIs to enhance the accuracy of risk prediction for BCa patients; (4) It explored, quantified, and validated several potential BCa prognostic biomarkers in WSIs; (5) Based on the proposed prognostic models, an end-to-end pathology-based AI prognostic system was developed to enhance its utility in clinical practice.

To explore quantitatively interpretable AI biomarker predictions, we employed the attribution method in MacroVisionNet. For individuals with a negative prognosis, the attribution maps of MacroVisionNet focus more on the areas where the tumor invades the muscularis and adipose tissue. For individuals with a positive prognosis, the MacroVisionNet attribution maps focus more on areas where tumor-associated lymphoid tissues accumulate. Inspired by this information, we explored and validated six potential biomarkers and compared the differences between these biomarkers in the low-risk and high-risk groups of the MacroVisionNet. In the univariate Cox regression analysis, both IMTS and Coloc were identified as independent prognostic factors across all enrolled cohorts22. Similarly, the IMTS and Coloc distribution differences in the MacroVisionNet risk groups were also observed in the CMUFH training, CMUFH validation, and TCGA cohort, which suggests that IMTS and Coloc are potential prognostic biomarkers for bladder cancer. The lack of robust risk stratification performance by other prognostic markers may be due to variations in data distribution within the validation and training set and potential interactions among different biomarkers. Further validation with additional datasets is needed to confirm the prognostic utility of these markers. Attribution techniques employed in this study facilitated the identification and interpretation of crucial regions within the WSIs, including places with prominent immune activity and distinct tissue distribution characteristics, aiding urologists and pathologists in understanding the model’s decision-making process. The proposed prognostic risk scores generated by MacroVisionNet offered independent prognostic insights, which were integrated with tissue distribution information to enhance overall prognostic assessment. This integration facilitated an improved risk stratification performance, especially in deciding the need and intensity of additional medications in BCa patients. During the construction of UniVisionNet, we employed a pretrained self-supervised histopathology network to extract tumor features from image tiles. By integrating macro-level prognostic features with micro-level tumor characteristics, the TransMIL network demonstrated superior model performance, leading to enhanced prognostic assessment. Additionally, the attention score heatmaps revealed that the UniVisionNet also focuses on regions of tumor muscle invasion and immune cell presence.

Significant variations in immune infiltration distribution were detected between the high-risk and low-risk UniVisionNet groups in the TCGA cohort. Specifically, the high-risk score group showed a notably elevated level of immunological infiltration in CD8 T cells, CD4 T cells, and neutrophil cells. This suggests a potential connection between immune cell infiltration, disease severity, and prognosis for BCa patients. Further research could concentrate on elucidating the precise mechanisms by which immune cell infiltration impacts BCa progression and patient prognosis23. Additionally, integrating multi-omics data and deep learning models could further enhance the predictive accuracy and interpretability of potential pathological biomarkers24,25.

Our study has some limitations. First, all slides used in our study were collected and analyzed retrospectively, which could introduce a degree of selection bias. Despite this, the favorable performance of the prognostic system in consecutive external validation cohorts suggests that the bias is not significant. Second, considering that some subgroups had a limited number of cases, there is still room for improvement in the sample size, and further external cohort verification with larger participants is necessary. Third, the high-resolution WSI inference demands high memory and powerful computer devices, whereas digital portable devices are more commonly used in resource-limited regions of developing countries. Therefore, exploring the development of lightweight AI networks for more affordable and accessible devices is essential. Lastly, the lack of a unified framework integrating histopathology, radiomics, and genomics for BCa prognosis restricts the development of multimodality-based AI prognostic systems. Hence, the development of multimodal-based AI prognostic diagnostic system is to be explored26,27.

In summary, we developed and validated a deep learning system, integrating macroscopic tissue distribution information with microscopic tumor information, to accurately predict the survival risks of bladder cancer. The output risk scores are an independent prognostic indicator that urologists and pathologists can use to stratify the OS risk in BCa patients.

Methods

Patient cohorts

This study adhered to the Transparent Reporting of a Multivariable Prediction Model for Individual Prognosis or Diagnosis, and Reporting recommendation for tumor marker prognostic studies28,29. In this retrospective, multicenter, prognostic study conducted in China, we enrolled consecutive patients with bladder cancer who underwent surgery, including radical cystectomy or TURBT, at three medical institutions. Additionally, we incorporated bladder diagnostic slides from the TCGA public database as an international validation cohort. From the medical record files of the three participating hospitals, the authors retrieved baseline participant characteristics, including clinical information, preoperative imaging reports, postoperative care records, cystoscopy follow-up documentation, and postoperative pathology reports. Patients who underwent treatment between 1 December 2012 and 30 December 2023 were enrolled in this retrospective study. The last follow-up was conducted on 28 February 2024. The records omitted ethnicity data. The follow-up data collation and verification period ranged from November 2023 to February 2024. Patients enrolled in CMUFH were randomly divided into the training set and the validation set, in a ratio of 7:3. Patients from CMUSH and YCH were allocated into two separate external validation cohorts. We designated the Cancer Genome Atlas Urothelial Bladder Carcinoma (TCGA-BLCA) set as an extra external validation cohort to enhance the generalizability of the findings. We excluded patients with a postoperative diagnosis of non-urothelial carcinoma due to the heterogeneous nature and small number of these tumors. We excluded low-quality WSIs, such as those with extreme fading, low resolution, or improper scanning. Detailed inclusion and exclusion criteria are displayed in Fig. 4.

Ethics statement

This retrospective study received approval from the research ethics committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing Medical University, the research ethics committee of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing Medical University, and the research ethics committee of Yongchuan Hospital of Chongqing Medical University. The committees waived the need for informed consent since the study solely relied on existing medical data. The study has been registered on ClinicalTrials.gov (registration number: NCT06389019).

Image acquisition

We collected hematoxylin and eosin-stained slides from the three participating hospitals. Subsequently, these slides were then scanned by digital slide scanners to get the WSIs file (40x magnification). The non-TCGA WSIs were generated using three digital slide scanners: KF-PRO-020 (Jiangfeng Bio-Information Technology Co, Ningbo, China) with a specimen-level pixel size of 0.246 μm × 0.246 μm, KF-PRO-005-EX (Jiangfeng Bio-Information Technology Co, Ningbo, China) with a specimen-level pixel size of 0.252 μm × 0.252 μm, and SQS-600P (Shengqiang Technology, Shenzhen, China) with a specimen-level pixel size of 0.206 μm × 0.206 μm. The three types of scanners were performed using 40-times objective lenses. All WSIs in the TCGA cohort were scanned with Leica Aperio scanners. Comprehensive diagnostic whole-slide data and related scanning information can be accessed from the National Institutes of Health Genomic Data Commons (GDC).

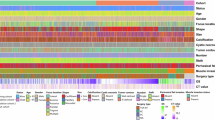

WSI annotation method and deep learning procedures

In the tissue segmentation procedure, tiles in WSIs are classified into eight classes: tumor area, connective tissue area, muscular tissue area, lymphovascular area, non-relevant areas (non-ROI), adipose tissue area, empty area, and lymphocyte area. The WSI annotation method utilizes the pre-trained Segment Anything Model (SAM) to assist pathologists in delineating various regions within the QuPath software. For precise annotation of lymphovascular and lymphocyte regions, pathologists leverage the SAM to rapidly outline the contours, followed by minor adjustments30. Pathologists efficiently outline larger regions like muscularis and connective tissue areas by drawing rectangular contours. The corresponding patch label is assigned based on the component that occupies more than fifty percent of the area. After completing the annotations, we used the DeepZoomGenerator function from the OpenSlide package to extract the corresponding patches based on the annotated coordinates. Each tile annotation is independently performed by two experienced pathologists (BL and YWT, senior expertise in clinical diagnostic pathology). In case of any disagreements, a third pathologist (YDC, chief physician with over 30 years of experience in clinical diagnostic pathology) is consulted to resolve any disputed annotations. Figure 5 depicts the workflow of the AI prognostic system comprising three primary components: tissue segmentation procedure, prognostic network construction, and model explanation compared with AI-inspired biomarker exploration. A visual representation of the application of the AI prognostic system is available in the Fig. 6.

The AI prognostication prediction system consists of three main components: the tissue segmentation part (BlaPaSeg inference process), the MacroVisionNet part, and the UniVisionNet part. In the PDF version of this article, please click anywhere on the figure or caption to play the video in a separate window.

BlaPaSeg network augmentation method and training strategy

We employed the ResNeXt50 as the backbone of BlaPaSeg network31. To improve the BlaPaSeg network generalization performance, common augmentation methods, including random gamma adjustment, random nineteen-degree rotation, RGB shifting, random brightness, and contrast adjustment, were applied during the training phase. Given the scarcity of lymphovascular area samples relative to other categories, dynamic augmentation was specifically applied to lymphovascular patches during the training process to mitigate the effects of data imbalance. Specifically, we introduced random initial coordinate offsets during lymphovascular patch extraction, maximizing the number of patches containing lymphovascular content. Meanwhile, we tripled the number of lymphovascular patches by duplication and further applied dynamic transformations in the training process. Additionally, to avoid overfitting, we implemented a two-stage based training process focused on identifying and labeling hard samples—patches that the BlaPaSeg model found challenging to classify. Initially, pathologists marked typical regions and areas, followed by an inference step using the initial BlaPaSeg model to identify and annotate areas where the model made errors. These hard samples were subsequently used to retrain the BlaPaSeg network. This iterative strategy was applied twice to generate additional hard samples, ultimately refining the final model.

BlaPaSeg inference procedure

In the BlaPaSeg network inference phase, WSIs were divided into patch images. Initially, we applied the OTSU technique to eliminate the background in the thumbnail image of the tissue. We generate patch images (256*256 pixels) by utilizing the coordinates of the non-blank region retrieved from the thumbnail image of WSI file (20x magnified). To mitigate information loss caused by the patch size, each patch generated by corresponding coordinates overlaps with its neighboring patches by half of its own size. Through continuous patch inference by the BlaPaSeg network and coordinate arrangement, multi-class tissue probability heatmaps and multi-class tissue segmentation maps will ultimately be generated. In other word, we modified the last output feature of fully connected layers (\({f}_{fc}\)) of ResNeXt50 into 8, \(p(i,j)\) is the probability of each patch. The \(I(i,j)\) is the input patch with corresponding coordinates. The \(p(i,j)\) is defined as follows:

To capture information at both macroscopic and microscopic levels from WSIs, we employed multi-class tissue probability heatmaps created by BlaPaSeg as the macroscopic component, complemented by microscopic tissue patch images as the microscopic component.

MacroVisionNet construction

To predict survival outcomes from the probability heatmaps created by BlaPaSeg, we developed the MacroVisionNet by building upon the ResNeXt50 network. The MacroVisionNet is designed to focus on the broader view of WSIs, learning to identify and represent key features that are important for predicting patient survival. It works by analyzing probability heatmaps, which indicate different tissue types within the WSIs. Unlike the original ResNeXt50 network, we modified the initial convolutional layer to accept eight input channels. This adjustment aligns the MacroVisionNet with the multi-class tissue probability heatmaps. To make the model more efficient, we reduced the output dimension of the final fully connected layer by incorporating a fully connected layer followed by batch normalization and a ReLU activation function. Finally, a linear layer translates these feature vectors into the final survival risk scores.

UniVisionNet construction

The UniVisionNet network was developed to integrate and leverage both macro and micro-level information in WSIs. Firstly, the trained MacroVisionNet generates the macroscopic prognostic features (2048 one-dimensional features). Simultaneously, micro-level prognostic features are extracted from tumor patches identified by the BlaPaSeg network. Specifically, we selected the top 200 patches with the highest tumor probabilities, each sized at 1024×1024 pixels. In cases where fewer than 200 patches are available, the highest-probability patches are used, with zero-padding applied if necessary to maintain the required number of patches. All selected patches were subsequently color normalized using the Macenko method. Subsequently, each patch is processed through a pretrained self-supervised histopathology network to extract microscopic features. We then replicate the macroscopic feature for each selected patch and concatenate it with the corresponding microscopic feature, resulting in a comprehensive feature representation for each patch. To determine the most effective architecture for these multi-level features, we evaluated several models from previous research, including AttMIL, Patch-GCN, Perceiver, Multi-perceiver and TransMIL. Meanwhile, we compared several self-supervised histopathology networks on the downstream task of Bca prognosis, including CTransPath, Virchow, Uni, and Prov-Gigapath32,33,34,35. Among these, the combination of TransMIL with self-supervised features extracted by the Uni network demonstrated slightly more stable performance across all validation cohorts, which contributed to its selection as the backbone of UniVisionNet. By combining macro and micro-level information within the TransMIL framework, UniVisionNet effectively captures both broad and detailed patterns in WSIs, leading to improved survival predictions. Detailed ablation experiment results are presented in Supplementary Table 2.

Attribution methods and attention score visualization

To explore the relationship between MacroVisionNet and prognosis, we used saliency maps, which were generated by calculating the gradient of the loss function for risk score with respect to the input pixels, combined with tissue segmentation maps to achieve interpretation. To enhance visualization, we increased the first 30% of the saliency map values and overlaid it with the corresponding segmentation map. Similarly, to investigate the relationship between UniVisionNet and prognosis, we extracted the attention scores generated by the UniVisionNet network. These attention scores were mapped to the corresponding patch coordinates within the WSI images and overlaid on the WSI thumbnail images. This approach allowed us to visualize the specific patch regions that the UniVisionNet network focused on.

Quantification of AI inspired prognostic biomarker

Tissue fraction calculation: Utilizing the segmentation map S, the tissue fraction for each class among the six tissue classes (excluding empty areas and non-ROI areas) can be expressed as:

\({N}_{t}\) represents the number of pixels belonging to class t in set S, \({N}_{empty}\) represents the number of empty pixels in set S, and \({N}_{non-ROI}\) indicate the number of pixels corresponding to area to be ignored in set S. N indicates the total number of pixels in set S. The segmentation map (S) is calculated by applying an argmax function to tissue probability heatmap (\(Mp\)).

TFS: Tumor fraction score (TFS) represents the tumor tissue fraction in the segmentation map (S). The TFS is defined as follows:

\({N}_{TUM}\) denote the number of pixels corresponding to tumor area.

\(IFS\): Infiltrating lymphocytes score (\(IFS\)) represents the infiltrating lymphocytes fraction in the segmentation map (S). The \(IFS\) is defined as follows:

\({N}_{INF}\) denote the number of pixels corresponding to lymphocytes.

\(TILs\): Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (\(TILs\)) have been identified as a significant prognostic indicator for various cancers. In our study, we assessed \(TILs\) based on the segmentation map \(S\) created by BlaPaSeg and TIL abundance (TILAb) score. To quantify TILs, we partitioned the segmentation map S into m × n grids of equal size, with each grid having a dimension of ten pixels. Subsequently, we defined the lymphocytes co-localization score M using the Morisita–Horn index. The M is defined as follows:

\({p}_{ij}^{INF}\) and \({p}_{ij}^{TUM}\) denote the percentage of inflammation and tumor regions in the grid-cell (i, j). Recognizing inflammatory proliferation within the tumor as a favorable prognostic factor for patient survival, the quantified TILs can be expressed as:

\(TIM\) and \(Coloc\): Inspired by \(TILs\), we defined and verified a novel prognostic biomarker called Tumor Muscle Infiltration Fraction (\(TIM\)) and tumor Co-localization score (\(Coloc\)). \(TILs\) quantified the spatial distribution and interaction between tumor and inflammation to characterize tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes. Similarly, \(TIM\) and \(Coloc\) are employed to quantify the spatial overlap of tumor boundaries and muscularis boundaries, representing the interaction and spatial distribution between tumor and muscularis. Recognizing muscularis tissues within the tumor as a negative prognostic factor for patient survival. A higher \(TIM\) value and \(Coloc\) value reflect a more extensive infiltration of muscle tissue by the tumor, indicating a potentially more aggressive or advanced stage of the disease3. The quantified \(TIM\) and \(Coloc\) can be expressed as:

\({p}_{ij}^{MUS}\) and \({p}_{ij}^{TUM}\) denote the percentage of muscularis and tumor regions in the grid-cell (\(i,j\)).

\(IMTS\): Integrated Muscle Tumor Score (\(IMTS\)) is a novel prognostic biomarker developed to assess the extent and severity of tumor infiltration within muscle tissues, alongside the quantification of overall tumor burden within bladder cancer. The \(IMTS\) is calculated using the formula: \(IMTS=TIM\times TFS\). A higher \(IMTS\) indicates a greater extent of muscle infiltration by the tumor and a larger overall tumor presence, suggesting a potentially more aggressive or advanced disease state. The quantified IMTS can be expressed as:

Statistical analyses

The concordance index (C-index) and the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) were employed to assess the predictive performance for overall survival (OS).OS is defined as the duration from the time of surgery to death from any cause or until the date of the final follow-up. Using the threshold determined by the maximally selected rank statistic in the training set, risk scores across all cohorts were divided into two categories: high-risk and low-risk. High-risk group refers to a situation where the level is equal to or greater than the threshold, while low-risk group refers to a situation where the level is lower than the threshold. The survival differences between the groups were compared using a Kaplan-Meier analysis and log-rank test. A Cox proportional hazards model was subsequently applied for these groups. Multivariable analyses were conducted using a Cox proportional hazards model from the survival package. The cutoff values for potential biomarkers were similarly based on the maximally selected rank statistic in the training set. The edgeR package was utilized to identify differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between the low- and high-risk groups in UniVisionNet36. The Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis was done for these DEGs. To further explore the correlation between risk score and immune infiltration, the CIBERSORT algorithm and TIMER algorithm were utilized to compute the proportions of tumor-infiltrating immune cells in the TCGA cohort37,38. All statistical tests were two-sided, and a p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Computational hardware and software

In Python (version3.9.12) environment, several specialized packages were incorporated: PyTorch (version2.0.0) for deep learning model construction, Lifelines (version 0.27.8) for survival analyses, NumPy (version 1.24.1) and Pandas (version 2.1.2) for data handling, Albumentations (version 1.3.1) and OpenCV (version 4.8.1) for image transformations, and OpenSlide (version 1.1.2) for handling WSIs. Models were trained on a dual-GPU (Nvidia RTX 4090) workstation.

Data availability

TCGA-BLCA set is publicly available at https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/projects/TCGA-BLCA. The data from three medical institutions can be obtained from the corresponding author upon reasonable request, subject to approval by the institutional review board of all registered centers. This is due to the sensitive nature of the raw images and follow-up data, which could compromise patient privacy.

Code availability

The source code is openly available in the GitHub repository (https://github.com/jacobhqh1997/BCa_os_framework).

References

Sung, H. et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA: A Cancer J. Clin. 71, 209–249 (2021).

Compérat, E. et al. Current best practice for bladder cancer: a narrative review of diagnostics and treatments. Lancet (Lond., Engl.) 400, 1712–1721 (2022).

Babjuk, M. et al. European association of urology guidelines on non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer (Ta, T1, and carcinoma in situ). Eur. Urol. 81, 75–94 (2022).

Laukhtina, E. et al. Diagnostic accuracy of novel urinary biomarker tests in non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Eur. Urol. Oncol. 4, 927–942 (2021).

Alfred Witjes, J. et al. European association of urology guidelines on muscle-invasive and metastatic bladder cancer: Summary of the 2023 guidelines. Eur. Urol. 85, 17–31 (2024).

Klaassen, Z. et al. Treatment strategy for newly diagnosed T1 high-grade bladder urothelial carcinoma: New insights and updated recommendations. Eur. Urol. 74, 597–608 (2018).

Holzbeierlein, J. M. et al. Diagnosis and treatment of non-muscle invasive bladder cancer: AUA/SUO guideline: 2024 amendment. J. Urol. 211, 533–538 (2024).

Perez-Lopez, R. et al. A guide to artificial intelligence for cancer researchers. Nat. Rev. Cancer 24, 427–441 (2024).

Vittone, J., Gill, D., Goldsmith, A., Klein, E. A. & Karlitz, J. J. A multi-cancer early detection blood test using machine learning detects early-stage cancers lacking USPSTF-recommended screening. NPJ Precis. Oncol. 8, 91 (2024).

Gui, C. P. et al. Multimodal recurrence scoring system for prediction of clear cell renal cell carcinoma outcome: a discovery and validation study. Lancet Digital health 5, e515–e524 (2023).

Jiang, L. et al. Autosurv: interpretable deep learning framework for cancer survival analysis incorporating clinical and multi-omics data. NPJ Precis. Oncol. 8, 4 (2024).

Shephard, A. J. et al. A fully automated and explainable algorithm for predicting malignant transformation in oral epithelial dysplasia. NPJ Precis. Oncol. 8, 137 (2024).

Claudio Quiros, A. et al. Mapping the landscape of histomorphological cancer phenotypes using self-supervised learning on unannotated pathology slides. Nat. Commun. 15, 4596 (2024).

Courtiol, P. et al. Deep learning-based classification of mesothelioma improves prediction of patient outcome. Nat. Med. 25, 1519–1525 (2019).

Lu, M. Y. et al. Data-efficient and weakly supervised computational pathology on whole-slide images. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 5, 555–570 (2021).

Lafarge, M. W. et al. Image-based consensus molecular subtyping in rectal cancer biopsies and response to neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy. NPJ Precis. Oncol. 8, 89 (2024).

Wang, Q. et al. Tertiary lymphoid structures predict survival and response to neoadjuvant therapy in locally advanced rectal cancer. NPJ Precis. Oncol. 8, 61 (2024).

Neto, P. C. et al. An interpretable machine learning system for colorectal cancer diagnosis from pathology slides. NPJ Precis. Oncol. 8, 56 (2024).

Lu, M. Y. et al. AI-based pathology predicts origins for cancers of unknown primary. Nature 594, 106–110 (2021).

Liang, J. et al. Deep learning supported discovery of biomarkers for clinical prognosis of liver cancer. Nat. Mach. Intell. 5, 408–420 (2023).

Nyman, J. et al. Spatially aware deep learning reveals tumor heterogeneity patterns that encode distinct kidney cancer states. Cell Rep. Med. 4, 101189 (2023).

Shaban, M. et al. A novel digital score for abundance of tumor infiltrating lymphocytes predicts disease free survival in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Sci. Rep. 9, 13341 (2019).

Martinez Chanza, N. et al. Tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (TIL) assessment in muscle invasive bladder cancer (MIBC) patients treated with cisplatin-based neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC) and surgery. J. Clin. Oncol. 38, 547–547 (2020).

Wang, H. et al. Deep learning signature based on multiphase enhanced CT for bladder cancer recurrence prediction: A multi-center study. EClinicalMedicine 66, 102352 (2023).

Chen, R. J. et al. Pathomic fusion: An integrated framework for fusing histopathology and genomic features for cancer diagnosis and prognosis. IEEE Trans. Med. imaging 41, 757–770 (2022).

Paverd, H., Zormpas-Petridis, K., Clayton, H., Burge, S. & Crispin-Ortuzar, M. Radiology and multi-scale data integration for precision oncology. NPJ Precis. Oncol. 8, 158 (2024).

Song, H. et al. Development and interpretation of a multimodal predictive model for prognosis of gastrointestinal stromal tumor. NPJ Precis. Oncol. 8, 157 (2024).

Collins, G. S., Reitsma, J. B., Altman, D. G. & Moons, K. G. Transparent reporting of a multivariable prediction model for individual prognosis or diagnosis (TRIPOD): the TRIPOD statement. BMJ (Clin. Res. ed.) 350, g7594 (2015).

Sauerbrei, W., Taube, S. E., McShane, L. M., Cavenagh, M. M. & Altman, D. G. Reporting recommendations for tumor marker prognostic studies (REMARK): An abridged explanation and elaboration. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 110, 803–811 (2018).

Kirillov, A. et al. Segment anything. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision 4015-4026 (2023).

Xie, S., Girshick, R., Dollár, P., Tu, Z. & He, K. Aggregated residual transformations for deep neural networks. In 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) 5987-5995 (2017).

Chen, R. J. et al. Towards a general-purpose foundation model for computational pathology. Nat. Med. 30, 850–862 (2024).

Xu, H. et al. A whole-slide foundation model for digital pathology from real-world data. Nature 630, 181–188 (2024).

Vorontsov, E. et al. A foundation model for clinical-grade computational pathology and rare cancers detection. Nat. Med. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-024-03141-0 (2024).

Wang, X. et al. Transformer-based unsupervised contrastive learning for histopathological image classification. Med. image Anal. 81, 102559 (2022).

Robinson, M. D., McCarthy, D. J. & Smyth, G. K. edgeR: A Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinforma. (Oxf., Engl.) 26, 139–140 (2010).

Li, T. et al. TIMER: A web server for comprehensive analysis of tumor-infiltrating immune cells. Cancer Res. 77, e108–e110 (2017).

Chen, B., Khodadoust, M. S., Liu, C. L., Newman, A. M. & Alizadeh, A. A. Profiling tumor infiltrating immune cells with CIBERSORT. Methods Mol. Biol. (Clifton, N. J.) 1711, 243–259 (2018).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by Yingcai Master Teacher Program of Chongqing (No. CQYC202003), Chongqing Municipal Education Commission’s l4th Five-Year Key Discipline Support Project (No.20240101), Natural Science Foundation of Chongqing (Grant Nos. CSTB2022NSCQ-MSX0109 and CSTB2023NSCQ-MSX0185). We appreciate all pathologists and related staff in each enrolled institution for their assistance in data collection. The computing work in this paper was partly supported by the Supercomputing Center of Chongqing Medical University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Q.H.H., B.X.X., Y.W.T., J.W., B.L., Y.D.C. and M.Z.X. conceived and designed the study; H.T., B.X.X., C.J.P., Y.W.T., J.W. and Q.H.H. collected the data. Q.H.H., B.X.X., H.T. and C.J.P. evaluated images. B.L., Y.W.T., and D.Y.C. labeled the pathological slide images. Q.H.H. and B.X.X. trained and developed the AI system. Q.H.H., B.X.X., J.W., and Y.W.T. analyzed and interpreted the data and wrote the original draft of the manuscript. Q.H.H., Y.W.T., and B.X.X. revised and completed the comparative experiments, while B.L., Y.D.C., and M.Z.X. supervised and directed the study.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

He, Q., Xiao, B., Tan, Y. et al. Integrated multicenter deep learning system for prognostic prediction in bladder cancer. npj Precis. Onc. 8, 233 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41698-024-00731-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41698-024-00731-6

This article is cited by

-

Deep learning feature-based model for predicting lymphovascular invasion in urothelial carcinoma of bladder using CT images

Insights into Imaging (2025)

-

Prior knowledge-guided multimodal deep learning system for biomarker exploration and prognosis prediction of urothelial carcinoma

npj Digital Medicine (2025)

-

Accelerating and protective effects toward cancer growth in cGAS and FcgRIIb deficient mice, respectively, an impact of macrophage polarization

Inflammation Research (2025)