Abstract

Pancreatic solid pseudopapillary neoplasms (SPNs) are uncommon tumors that rarely exhibit aggressive behavior. Given disease rarity, comprehensive studies to understand tumor biology, clinical course, and optimal management are limited. We describe an unusual case of a 55-year-old man with metastatic pancreatic SPN, where whole-genome and transcriptome analyses of the primary tumor and a metastatic liver lesion revealed a shared homozygous non-canonical mutation in APC. The patient received upfront modified FOLFIRINOX (infusional 5-fluorouracil, irinotecan, and oxaliplatin) chemotherapy due to rapidly progressive symptoms, demonstrating an early and sustained treatment response. Therefore, we identified potential genetic determinants of tumorigenesis and progression in a pathologically and clinically aggressive SPN, which may have important prognostic and treatment implications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Solid pseudopapillary neoplasm (SPN) is a rare type of pancreatic tumor that predominantly occurs in females of reproductive age, typically characterized by an indolent clinical course, minimally symptomatic presentation, and a highly favorable prognosis when complete resection is feasible1,2. However, up to 10–15% of cases are considered aggressive and can invade locoregional structures or metastasize to distant organs, most commonly the liver2. Due to disease rarity and consequent paucity of reported data, clinicopathological and molecular characteristics, as well as optimal management of SPNs, particularly in aggressive cases, are not well defined.

At British Columbia (BC) Cancer, the Personalized OncoGenomics (POG) program is a research initiative that uses whole-genome and transcriptome sequencing to study tumor biology. For eligible patients with advanced cancers, comprehensive genomic data is analyzed to identify potential drivers or clinically actionable mutations that may inform diagnostics or treatments3. Here, we describe a patient with pancreatic SPN presenting with highly symptomatic metastatic disease that was treated using upfront modified (m) FOLFIRINOX (infusional 5-fluorouracil, irinotecan, and oxaliplatin) chemotherapy. Whole-genome sequencing was performed on both the pancreatic primary and liver metastasis, revealing a non-canonical loss-of-function mutation in APC as the driver of tumorigenesis.

Results

Case presentation

A 55-year-old male presented with several months of progressive abdominal discomfort. Blood work showed cholestatic liver enzyme elevation and abdominal ultrasound demonstrated scattered heterogenous isoechoic hepatic nodules. Magnetic resonance imaging of the liver followed by multiphasic computed tomography (CT) of the pancreas identified a 4.5 cm pancreatic tail mass with peripancreatic and portal hepatic lymphadenopathy, and disseminated multifocal solid hepatic masses, the largest measuring 6.5 cm (Fig. 1A), in keeping with metastatic disease. There was no vascular involvement. CT chest showed no thoracic metastasis.

Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle biopsy of the pancreatic mass was performed for pathologic evaluation, revealing solid nests and sheets of uniform cells with round to oval nuclei and eosinophilic cytoplasm consistent with SPN, and tumor cells were seen infiltrating into the adjacent pancreatic parenchyma (Fig. 2A–C). Immunohistochemical staining was positive for beta-catenin (nuclear and cytoplasmic; Fig. 2D) and CAM5.2, with patchy positivity for cytokeratin (CK) 20 and CDX-2. Negative stains included CK7, synaptophysin, and chromogranin. Ki-67 index was 30% (Fig. 2E). One of the liver lesions was biopsied and showed the same tumor morphology, confirming metastatic involvement from the primary pancreatic SPN. The immunohistochemical profile of the metastatic tumor was similar, with immuno-expression positive for beta-catenin, membranous E-cadherin, CK cocktail, CD99 (dot-like), and negative for the progesterone receptor, synaptophysin, and p40. Ki-67 index was also 30%.

A Low power view showing the solid sheets of monomorphic cells; 100x. B Infiltrative small nests of tumor cells into the adjacent pancreatic parenchyma with desmoplastic stroma; 200x. C High-power view demonstrating the monomorphic cells with round to oval nuclei; 400x. D Beta-catenin (nuclear and cytoplasmic) staining of tumor cells. E Ki-67 proliferation staining.

Due to extensive involvement and highly symptomatic presentation, the patient began mFOLFIRINOX chemotherapy in 2-week cycles. Serial CT chest abdomen pelvis revealed stable disease in the pancreatic primary and regional lymph nodes, with improvement in the liver lesions after 8 cycles of chemotherapy (Fig. 1B). Five target lesions were measured at baseline and cycle 8 timepoints, with a sum of the longest diameter change from 24.6 to 20.7 cm (−15.9%; stable disease). At the time of manuscript writing, the patient had remained on treatment for 34 weeks (17 cycles). Treatment-related toxicities experienced during the course of chemotherapy include grade 2 (moderate) fatigue, nausea, and dysgeusia as defined by the National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria for Adverse Events4, which led to oxaliplatin omission from cycle 9 to improve tolerance. Oxaliplatin was reintroduced in cycle 16, and side effects have been well controlled with supportive medications since.

Genomic analysis

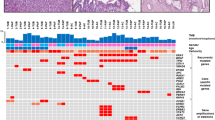

To characterize the mutational landscape and identify mutations that may contribute to disease aggressiveness, whole-genome and transcriptome (RNA-seq) sequencing data were individually generated from one primary (pancreas) and one metastatic (liver) tumor biopsy sample. Primary and metastatic samples were both diploid, with computationally estimated tumor contents of 74% and 73%, respectively. Exonic tumor mutation burden (TMB) was measured at 1.1 mut/Mb in the primary and 0.69 mut/Mb in the metastasis, consistent with the notion that the metastatic lesion underwent clonal selection (Fig. 3A). Across both samples, only a single 0.58 mb segment of the genome was amplified (four copies) on chromosome 14 of the metastasis, which affects a V region of the variable domain of T cell receptor alpha chain. No oncogenic fusions were identified. A frameshift deletion (chr5 position 112839210; AGTAAAAC > A) affecting APC was identified in both primary (variant allele frequency (VAF) = 63.0%) and metastatic (VAF = 65.7%) samples and is likely the primary driver of disease (Fig. 3B). Of additional note was a nonsense mutation affecting TLR7 (chrX position 12886064; C > T; p.Arg186*) which showed high VAF in both primary (56.2%) and metastatic (80.0%) samples. Overall, 2699 variants (SNV/indels) were shared by both primary and metastatic samples, while 2538 variants were unique to the primary and 1421 variants were unique to the metastatic sample (Fig. 3C). Overall, VAF values were lower for variants identified in the primary tumor compared to those in the metastasis (median 15.8% versus 35.1% (respectively); p < 2.2e-16), providing further evidence for clonal selection in the metastatic tumor. Variants unique to the metastatic sample included those affecting CLEC4M (two variants; missense), a C-type lectin with roles in cell adhesion, and cell wall biogenesis gene CWH43 (chr4 position 48994628; G > T; Cys174Phe; missense; Fig. 3D). To provide insight into differences in mutational signatures, the trinucleotide context (flanking nucleotides) was assessed for SNVs unique to the primary, the metastasis, or identified in both. The distribution of trinucleotide sequences was highly similar for each group of SNVs, suggesting that mutational process(es) that may have given rise to variants were not different between the primary and metastatic samples (Fig. 3E).

A Circos diagram depicting the overall somatic mutation (SNV/indel and CNV) landscape of the primary (left) and metastatic (right) tumor lesions. B Scatter plot comparing variant allele frequency (VAF; %) of all variants identified in either the primary or metastatic tumors. C Pie charts depicting the distribution of variant type for mutations unique to the primary or metastatic tumor, or found in both tumors. Genes affected by likely loss-of-function variants (missense, frameshift, nonsense) are listed. D Dot map showing representative variants unique to the primary or metastatic tumor or found in both tumors. CNV status is represented by the outer box, while variant type and VAF are reflected by dot color and size, respectively. E Distribution of trinucleotide context for all SNVs detected in both the primary and metastatic tumors or unique to one tumor.

Discussion

SPNs comprise 1–3% of all pancreatic tumors, and aggressive cases are even more rare, making comprehensive studies to understand tumor biology and clinical behavior challenging. Here, we report a 55-year-old man with a highly proliferative pancreatic SPN with regional lymphadenopathy and biopsy-proven multifocal liver metastases. Whole-genome analyses of the primary tumor and metastatic lesion revealed a shared homozygous loss-of-function mutation in APC. The patient experienced rapidly progressive symptoms and demonstrated an early response to mFOLFIRINOX chemotherapy.

Pathologic correlates of clinical aggressiveness in SPNs have been evaluated across many studies, though findings have been inconsistent, likely due to small sample sizes in most analyses. Ki-67 index is a widely used pathologic marker for tumor cell proliferation and growth, and in a prior systematic review of 163 patients from 26 studies of SPN, Ki-67 index ≥4%, seen in 15 cases, was associated with worse recurrence-free and disease-specific survival5. In another single institution analysis, Chen et al.6 similarly identified Ki-67 index ≥5% as a predictor of decreased survival and an independent risk factor for aggressive behavior. However, a retrospective review of 31 patients with SPNs found no correlation between clinically malignant behavior and conventionally aggressive microscopic characteristics, including angioinvasion, perineural invasion, mitosis in 10 high-power fields, and moderate nuclear pleomorphism7. Therefore, although our patient’s manifestation of metastatic SPN with a high Ki-67 index supports an association between pathologic and clinical aggressiveness, additional studies with larger sample sizes are necessary to validate this correlation.

Dysregulation of the Wnt-signaling pathway, normally involved in cell proliferation and differentiation, has been implicated in the development of SPNs with beta-catenin, a key activating protein controlling the transcription of downstream targets, consistently overexpressed in the cytoplasm and nuclei of tumor cells7,8. Accordingly, gain-of-function mutations in CTNNB1, which encodes beta-catenin, have been reported in over 90% of pancreatic SPNs9,10. In our patient with wildtype CTNNB1, a non-canonical homozygous APC loss-of-function mutation was instead observed along with positive beta-catenin immuno-expression. Prior case studies have reported APC dysfunction as the driver of SPN in patients with Familial Adenomatous Polyposis, and it has been postulated that loss of APC, a primary protein in the beta-catenin destruction complex, results in impaired degradation and intracellular accumulation of beta-catenin, leading to dysregulated Wnt-signaling similar to that seen with oncogenic CTNNB1 mutations11,12. Therefore, the current case substantiates the proposed mechanism of APC-driven Wnt-activation in SPN tumorigenesis, which may be investigated in future studies as a target for molecular-directed therapies, such as tankyrase inhibitors.

Beyond the genetic determinants of tumor initiation, drivers of progression and metastasis in SPNs remain poorly understood. A prior study used high-coverage targeted sequencing of 409 genes to compare the primaries and metastases of five patients with SPNs and found that, similar to our case, the majority of genetic mutations were shared among the matched samples, suggesting that the inciting genetic events occurred before systemic spread13. Interestingly, they also reported that the most commonly identified mutations in metastatic SPNs occurred in tumor suppressor genes involved in epigenetic regulation of transcription, including KDM6A, TET1, and BAP1, which are often inactivated in aggressive cancers13. For our patient, one notable finding was a TLR7 loss-of-function mutation with high clonality and persistence in the matched genomic profiles. However, data on the role of TLR7 in pancreatic cancer remains conflicting, with some studies reporting TLR7 loss associated with poorer outcomes14 and others suggesting a benefit15. Additionally, a variant in CWH43, a tumor suppressor gene associated with epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and metastasis in colorectal cancer models16, was found uniquely in the liver metastasis. Therefore, while no actionable differences were identified in our case, the noted findings may provide insight into the molecular basis of SPN progression and dissemination.

Given the rarity of aggressive SPNs, there are no prospective studies to guide the most appropriate treatment. Surgical resection is preferred whenever feasible but in cases with disseminated or unresectable disease where systemic therapy is considered, there is no consensus on the standard regimen17,18. In an early review, Soloni et al19. reported cisplatin, 5-fluorouracil, and gemcitabine as the most common chemotherapy agents used in unresectable SPN, though only some patients derived clinical benefit and the impact of chemotherapy was unclear given the expected indolent nature of SPNs. In the current report, our patient was treated with mFOLFIRINOX chemotherapy akin to those with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, with a reduction in the size of liver lesions and stabilization of the pancreatic primary after only eight cycles. A previous case report also described a favorable response to neoadjuvant FOLFIRINOX, which facilitated a curative resection in an initially unresectable SPN after nine cycles17. However, the patient recurred shortly after with progressive liver metastases and was then treated with everolimus based on genomic testing of the primary tumor revealing a pathogenic PTEN mutation alongside a canonical CTNNB1 mutation, resulting in marked response and sustained partial remission. Overall, the reasonable tolerability and rapid treatment response in our patient further support the effectiveness of FOLFIRINOX chemotherapy in aggressive SPNs, though longer follow-up is needed to determine the durability of responses and long-term outcomes.

In summary, we present a case study of metastatic SPN where, in addition to pathologic and radiographic evaluation, whole-genome analysis of both primary and metastatic tumor lesions was used to identify potential genetic determinants of tumorigenesis and progression. Our patient had a pathologically and clinically aggressive SPN that was genomically characterized by a non-canonical homozygous loss-of-function mutation in APC and demonstrated early response to upfront mFOLFIRINOX chemotherapy. Longer follow-up is required to determine the long-term treatment benefit, while additional studies with larger sample sizes are needed to further characterize the clinicopathologic and molecular features that may predict differentially aggressive subtypes of SPN.

Methods

POG study enrollment

The patient was enrolled in the Personalized OncoGenomics (POG; NCT02155621) clinical trial. Core-needle biopsy samples (fresh-frozen) were concurrently taken from pancreas and liver tumors and used for sequencing. The POG trial was approved by the University of British Columbia Research Ethics Committee (REB# H12-00137) and was conducted in accordance with international ethical guidelines. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient prior to molecular profiling. All sequencing data were housed in a secure computing environment.

Genome sequencing and analysis

Tumor samples and their matched blood sample received whole-genome sequencing (WGS) with depths of 142x and 52x respectively for the primary sample, and 116X and 53X for the metastatic sample. RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) was performed on tumor samples to 532 million reads for the primary and 317 million reads for the metastatic sample. Sequencing libraries were aligned (hg38) and processed as previously described20.

Somatic mutation calling

Somatic SNV/indels, copy number variants, and RNA-based fusions were called using tumor and the matched normal sequencing libraries and filtered as previously described21. Genome version hg38 was used for all analyses.

Tumor mutational burden

TMB calculation was performed for exon regions of the genome, with standardized filtering criteria and calculation as previously described22.

Statistical analysis

Wilcoxon mean rank-sum tests were used for two-group comparison of continuous variables. All comparison tests were two-tailed. All analyses were performed using R v3.6.3.

Data availability

Genomic data generated within the POG study is available for download through the European Genome-phenome Archive (EGA) under accession number #EGAS00001001159.

References

Shuja, A. & Alkimawi, K. A. Solid pseudopapillary tumor: a rare neoplasm of the pancreas. Gastroenterol. Rep. 2, 145–149 (2014).

Tanoue, K. et al. Multidisciplinary treatment of advanced or recurrent solid pseudopapillary neoplasm of the pancreas: three case reports. Surg. Case Rep. 8, 7 (2022).

Pleasance, E. et al. Whole-genome and transcriptome analysis enhances precision cancer treatment options. Ann. Oncol. 33, 939–949 (2022).

National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, US Department of Health and Human Services. Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE), Version 5.0. Published November 27, 2017. https://ctep.cancer.gov/protocoldevelopment/electronic_applications/docs/CTCAE_v5_Quick_Reference_5x7.pdf (2017).

Yang, F. et al. Prognostic value of Ki-67 in solid pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas: Huashan experience and systematic review of the literature. Surgery 159, 1023–31 (2016).

Chen, H. et al. Solid-pseudopapillary neoplasm of the pancreas: a 63-case analysis of clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical features and risk factors of malignancy. Cancer Manag. Res. 13, 3335–3343 (2021).

Kim, J. H. & Lee, J. M. Clinicopathologic review of 31 cases of solid pseudopapillary pancreatic tumors: can we use the scoring system of microscopic features for suggesting clinically malignant potential? Am. Surg. 82, 308–313 (2016).

Selenica, P. et al. Solid pseudopapillary neoplasms of the pancreas are dependent on the Wnt pathway. Mol. Oncol. 13, 1684–1692 (2019).

Rodriguez-Matta, E. et al. Molecular genetic changes in solid pseudopapillary neoplasms (SPN) of the pancreas. Acta Oncologica 59, 1024–1027 (2020).

Abraham, S. C. et al. Solid-pseudopapillary tumors of the pancreas are genetically distinct from pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas and almost always harbor beta-catenin mutations. Am. J. Pathol. 160, 1361–1369 (2002).

Naoi, D. et al. Solid-pseudopapillary neoplasm of the pancreas in a patient with familial adenomatous polyposis: a case report. Surg. Case Rep. 7, 35 (2021).

Farahmand, F. et al. Pancreatic pseudopapillary tumor in association with colonic polyposis. J. Med. Med. Sci. 3, 447–451 (2021).

Amato, E. et al. Molecular alterations associated with metastases of solid pseudopapillary neoplasms of the pancreas. J. Pathol. 47, 123–134 (2019).

Lanki, M., Seppänen, H., Mustonen, H., Hagström, J. & Haglund, C. Toll-like receptor 1 predicts favorable prognosis in pancreatic cancer. PLoS ONE 14, e0219245 (2019).

Stark, M. et al. Dissecting the role of toll-like receptor 7 in pancreatic cancer. Cancer Med. 12, 8542–8556 (2023).

Lee, C. C. et al. CWH43 is a novel tumor suppressor gene with negative regulation of TTK in colorectal cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 15262 (2023).

Jorgensen, M. S., Velez-Velez, L. M., Asbun, H. & Colon-Otero, G. Everolimus is effective against metastatic solid pseudopapillary neoplasm of the pancreas: a case report and literature review. JCO Precis. Oncol. 3, 1–6 (2019).

Kim, C. W. et al. Solid pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas: can malignancy be predicted? Surgery 149, 625–634 (2011).

Soloni, P. et al. Management of unresectable solid papillary cystic tumor of the pancreas. A case report and literature review. J. Pediatr. Surg. 45, e1–6 (2010).

Pleasance, E. et al. Pan-cancer analysis of advanced patient tumors reveals interactions between therapy and genomic landscapes. Nat. Cancer 1, 452–468 (2020).

Topham, J. T. et al. Integrative analysis of KRAS wildtype metastatic pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma reveals mutation and expression-based similarities to cholangiocarcinoma. Nat. Commun. 13, 5941 (2022).

Topham, J. T. et al. Circulating tumor DNA identifies diverse landscape of acquired resistance to anti-epidermal growth factor receptor therapy in metastatic colorectal cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 41, 485–496 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This work would not be possible without the participation of our patients and families, the POG team, the Genome Science Center platform, and the generous support of the BC Cancer Foundation, Genome British Columbia (project B20POG, MOH001, MOH002), and the Terry Fox Research Institute Marathon of Hope Cancer Centers Network. We also acknowledge contributions towards equipment and infrastructure from Genome Canada and Genome BC (projects 202SEQ, 212SEQ, 262SEQ, 12002), Canada Foundation for Innovation (projects 20070, 30981, 30198, 33408, 35444, 42362, and 40104) and the BC Knowledge Development Fund. Other contributors include Roche Pharma.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.T.M.C. wrote the main manuscript text and provided clinical care to the patient. J.T.T. contributed to the genomic analysis and prepared figures 1 and 3. A.A. conducted a pathology review and prepared Figure 2. G.A.T., E.P., and M.K.M. contributed to genomic analysis. D.J.R. provided clinical care to the patient and conceptualized the study. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient prior to molecular profiling. The patient further provided consent to having their data, including genomic results generated through POG, anonymously shared in publication form.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cheng, P.T.M., Topham, J.T., Aldeheshi, A. et al. Whole-genome analysis of an aggressive metastatic pancreatic solid pseudopapillary neoplasm. npj Precis. Onc. 9, 59 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41698-025-00843-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41698-025-00843-7