Abstract

CIC::DUX4 sarcoma (CDS) is a rare and aggressive subtype of soft tissue sarcoma with poor prognosis and limited treatment options. Immunotherapy has not been studied in this disease. To our knowledge, response to immune checkpoint blockade (ICB) has not been previously reported. Here, we present the first case of a patient with CDS responding to dual ICB with nivolumab and relatlimab. Immunohistochemical (IHC) analysis of pre-treatment samples revealed minimal immune cell infiltration, with scarce CD3+, CD8+, and FOXP3+ T-cells and negligible expression of PD-L1 and PD-1 markers. Post-treatment tumor samples revealed a significant shift in the immune microenvironment, with increased CD8 + T-cell infiltration and co-expression of exhaustion markers PD-1 and LAG-3 following treatment. These findings suggest that doublet ICB can activate an antitumor immune response in CDS, overcoming the immune cold phenotype typically associated with this sarcoma. This case provides the first evidence of dual PD-1/LAG-3 blockade inducing an immune response in CDS. The favorable response and tolerability observed in this patient highlight the potential of dual ICB as a therapeutic option in CDS that merits further investigation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Soft tissue sarcomas (STS) encompass a highly diverse group of malignancies arising from mesenchymal tissues, with more than 80 distinct subtypes identified1. This heterogeneity poses considerable challenges for both biological insight and therapeutic development.

Advances in the molecular characterization of sarcoma have led to the identification of novel sarcoma subtypes, including a group of undifferentiated round cell sarcomas lacking Ewing sarcoma (EWS)-specific translocations2,3,4. Among these, CIC-rearranged sarcomas, particularly those with CIC-double homeobox 4 gene (DUX4) fusions (CIC::DUX4 sarcomas or CDS), represent a rare, aggressive subtype with a dismal prognosis5,6.

Although CDS comprises less than 1% of all sarcomas, it typically affects children and young adults. These tumors primarily arise in the soft tissues, especially in the extremities, trunk, and head and neck regions6,7,8. Furthermore, approximately 40% of cases exhibit early metastatic spread, frequently involving the lungs, bones, liver, and brain, complicating clinical management6.

Historically, CDS has been managed following the treatment paradigm for Ewing sarcoma, with limited success9. No standardized or effective therapy has emerged for CDS, and to date, immunotherapy has not been explored prospectively in this sarcoma subtype8.

In this report, we describe the first documented case of a CIC::DUX4 fusion-positive sarcoma responding to dual immune checkpoint blockade (ICB) with nivolumab and relatlimab in a 67-year-old woman. This case offers new insights into the immunologic landscape of CDS and represents a pivotal step in exploring immunotherapy for this rare and aggressive sarcoma. To our knowledge, this is the first instance of a CDS demonstrating clinical and radiologic response to immunotherapy, supported by immunologic correlates on baseline and post-treatment tissue analysis.

Results

Case report

A 67-year-old Caucasian woman presented with a right thigh mass (Fig. 1). On examination, there was a visible, focally ulcerated lesion approximately 2 cm in maximal diameter, located on the anterior aspect of the right thigh (Fig. 2a). The lesion was primarily subcutaneous with signs of ulceration, and no residual nevus or pigmented precursor lesion was identified. Additionally, two subcutaneous lesions, consistent with in-transit/satellite disease, were noted along with palpable right inguinal adenopathy.

a Clinical image of the baseline superficial CDS lesion on the right anterior thigh, measuring approximately 2 cm in diameter with focal ulceration. b Clinical image of the CDS tumor at Cycle 1, Day 21 of treatment, showing surrounding erythema and persistent ulceration. c Baseline PET scan of the right thigh and pelvis, showing multiple hypermetabolic soft tissue masses in the anterior right thigh subcutaneous fat, the largest measuring 2.8 × 2.1 cm. FDG-avid disease is also present in the right femur. Frontal (left) and lateral (right) views. d PET scan at 4 months of treatment demonstrating a reduction in FDG-avid masses in both the right thigh and right femur. Frontal (left) and lateral (right) views.

A PET-CT scan revealed at least four hypermetabolic soft tissue masses involving the anterior right thigh subcutaneous fat. The largest mass measured 2.8 ×2.1 cm with a maximum SUV of 13.1 (Fig. 2c). There was also right inguinal lymphadenopathy measuring 3.1 x 2.4 cm with a maximum SUV of 11.3. Fine needle aspiration of the mass was performed, and the initial histologic examination was equivocal, suggesting a poorly differentiated malignant neoplasm. The differential diagnosis included both sarcoma and melanoma.

Subsequently, a punch biopsy of the anterior right thigh mass was performed. Histologic evaluation demonstrated a poorly differentiated malignant round cell neoplasm with immunoreactivity for ERG. The tumor cells were negative for epithelial markers, as well as lymphoid and myeloid markers. Immunohistochemistry showed negativity for S100P, SOX10, CD34, and partial positivity for CD31. Melan-A showed focal positivity, and the tumor expressed PRAME. Testing for BRAFV600E and RASQ61R was negative.

The focal positivity for Melan-A and PRAME expression raised suspicion for dedifferentiated/undifferentiated melanoma, although the ERG positivity was unusual. Clinically, the disease presentation with nodal and satellite lesions was also suggestive of melanoma. Based on this, systemic therapy with nivolumab and relatlimab was initiated. Notably, a PET scan performed before treatment initiation showed metastatic progression, with new hypermetabolic lung and osseous lesions in L3 and the right femur (Fig. 2c).

For further diagnostic clarification and treatment planning, the tumor was subjected to molecular testing with MSK-IMPACT DNA Sequencing, which analyzes 505 cancer-associated genes at an average tumor coverage depth of 589x. This identified CIC gene amplification (19q13.2) (Fig. 3). Consistent with the genomic landscape of most STS, the baseline sample had a tumor mutation burden (TMB) score of 0 and was microsatellite stable (MSS). No somatic alterations were identified. Given the histologic ambiguity, Archer RNA sequencing was subsequently performed, confirming the presence of a CIC::DUX4 fusion, thereby establishing the diagnosis of CDS.

Normalized log2 coverage fold changes (log-ratios) of baseline tumor versus normal sample for all captured regions in the MSK-IMPACT assay illustrating copy number alterations (CNA. Circular binary segmentation algorithm was used to segment the data; red lines denote the resulting segmented regions. Each dot represents probe set. CIC amplification is clearly detectable (fold change (FC) ≥ 2.0), whereas other potential CNA should be interpreted with caution due to low molecular purity (0.25). Notably, MYC exhibits copy number gain (FC ≥ 1.5 but <2), but does not meet the amplification threshold.

By the time the diagnosis was revised to CDS, the patient had already been on nivolumab and relatlimab for three weeks. Interestingly, the patient reported noticeable improvement in the dominant right thigh mass, with a reduction in size and clinical confirmation of the inability to palpate the previously noted satellite lesions (Fig. 2b). Based on this favorable response, immunotherapy was continued. PET imaging after two cycles of treatment revealed a near-complete response at the primary right thigh site, significant metabolic improvement in the right inguinal nodes, and reduced systemic lesions (Fig. 2d).

Approximately five months after starting treatment, the solitary cutaneous right thigh lesion remained FDG avid. As such, the patient underwent excision of the residual right thigh tumor, which measured 2.6 × 1.7 × 1.5 cm and involved the dermis and subcutaneous tissue. Surgical margins were positive for tumor. The mitotic rate was 1/10 per 10 high-power fields (HPF), and treatment-related effects, including fibrosis and histiocytic aggregates, were observed in ~25% of the tumor (Fig. 4i). Pathology also revealed metastatic round cell sarcoma in two lymph nodes, with extranodal extension (2/8).

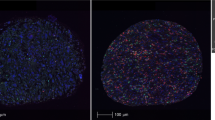

a Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stain of the anterior right thigh mass showing a poorly differentiated malignant round cell neoplasm (20x).b ERG immunostain, commonly seen in vascular endothelial tumors and round cell neoplasms (20x). c Ki-67 immunostain indicating high proliferative activity of tumor cells (40x). d–f Pre-treatment immunostains showing a lack of immune cell infiltration: CD3 + T cells (d), CD8+ cytotoxic T cells (e), and FOXP3+ regulatory T cells (f) (40x). g–h Pre-treatment immunostains showing low expression of immune markers: PD-L1 (g) and PD-1 (h) (40x). i Post-treatment H&E stain of the residual anterior right thigh mass, showing treatment-related changes, including fibrosis and histiocytic aggregates, affecting ~25% of the tumor (20x). j–l Post-treatment immunostains demonstrating increased immune cell infiltration: CD3 + T cells (j), CD8+ cytotoxic T cells (k), and FOXP3+ regulatory T cells (l) (20x). m–o Immunostains showing high expression of immune markers post-treatment: PD-L1 (m), PD-1 (n), and LAG-3(o) (20x).

The patient experienced a local recurrence at the surgical bed after 7 months of treatment, necessitating further resection. Tumor margins were negative following re-excision, but tumor extended to within 0.8 mm of the medial margin. Radiation therapy to the surgical bed was administered postoperatively. Notably, distant disease involving lung and bone remained treated on PET. She continued on nivolumab and relatlimab for a total of 12 months before further progression was noted on imaging.

Upon progression, the patient declined chemotherapy, and treatment was switched to doublet ICB with nivolumab and ipilimumab, resulting in mixed clinical and radiographic response. Ater two cycles, she experienced a substantial decrease or resolution in many thoracic and mediastinal lymph nodes, as well as a reduction in pulmonary parenchymal lesions by up to 1 cm. However, new areas of increased FDG avidity were observed in the right iliac region and lumbar spine. She remained on nivolumab and ipilimumab for a total of 3 months before discontinuing treatment due to immune-mediated colitis.

Immunohistochemistry analysis

To investigate the underlying mechanisms of the remarkable response to ICB, we analyzed tumor tissues obtained throughout the patient’s clinical course using immunohistochemistry (IHC) (Fig. 4).

Prior to treatment with nivolumab and relatlimab, immune staining was negative for all immune markers (CD3+, CD8+, FOXP3+, PD-L1, PD1), except for Ki-67, which indicated a high proliferative rate of the tumor cells (Fig. 4c–h). Additionally, there were no tertiary lymphoid structures detected on light microscopy. Following treatment with nivolumab and relatlimab, there was a striking increase in inflammatory cell infiltration (Fig. 4j–l).

In residual post-treatment tumor material, a significant proportion of cells express checkpoint markers, including LAG-3 (Fig. 4m–o). The increase in T cells, along with a shift toward a more proliferative cell population expressing checkpoint markers, suggests a profound alteration in the tumor’s immune environment. These findings are consistent with the activation of an antitumor immune response, followed by the emergence of CD8 + T-cell exhaustion, as evidenced by the expression of inhibitory checkpoint markers. This is the first documented case in CDS where ICB has demonstrated a sustained antitumor immune response, ultimately leading to T-cell exhaustion.

Furthermore, the detection of PD-L1+ cells within the resected tissue (Fig. 4m) suggests active involvement of the immune checkpoint, potentially contributing to recurrence by suppressing the antitumor response.

Discussions

This report presents evidence that dual ICB with nivolumab and relatlimab can induce a robust antitumor immune response in CDS. The patient described here remains alive more than 24 months following diagnosis with metastatic disease, with a partial response to doublet ICB in the first- and second-line settings—a remarkable outcome in an otherwise highly aggressive and lethal disease.

Immunotherapy has transformed the treatment landscape of many cancers, but its application in sarcomas has been limited to a few subtypes10,11,12,13. To date, the FDA has approved atezolizumab in alveolar soft part sarcoma, a translocation-associated sarcomas14. However, the precise mechanism behind this response remains unclear15. Similarly, the recent approval of T-cell-based therapy (afamitresgene autoleucel) in HLA-restricted, MAGE-A4-expressing synovial sarcoma, another fusion-driven sarcoma, marks a significant advance16,17. Beyond these examples, immune checkpoint blockade has shown only modest activity in other sarcoma subtypes, such as undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma, myxofibrosarcoma, and angiosarcoma10,16,18,19. Importantly, ICB has not demonstrated activity in Ewing sarcoma, which has traditionally informed the treatment approach for managing CDS10.

Despite the increasing identification of CIC::DUX4 rearrangements, their functional role in tumor biology, and particularly in the context of immune response, remains poorly understood. CIC, a developmental transcriptional repressor, is implicated in the regulation of MAPK effector genes and is highly conserved across species20,21. In addition to its involvement in sarcomas, CIC alterations have been identified in various malignancies, including prostate, lung, and gastric cancers22,23,24,25. In these contexts, loss of CIC function leads to dysregulation of pathways related to extracellular matrix remodeling, cell cycle progression, and tumor proliferation22. However, studies in glioma models indicate that CIC knockout enhances proliferation without triggering overt tumor formation, suggesting that the full oncogenic potential of CIC alterations may require additional factors23,24,25.

DUX4, typically expressed during embryogenesis and silenced in adult tissues, plays a distinct role when fused with CIC26,27,28. Unlike CIC alone, the CIC::DUX4 fusion has been shown to drive the formation of small round cell sarcomas in experimental models, providing direct evidence of its oncogenic potential25. Yet, the specific role of DUX4 in tumor progression, and especially in shaping the immune landscape, remains largely speculative.

Recent studies suggest that DUX4 may play a role in immune evasion by creating an immunologically “cold” tumor environment, characterized by low infiltration of cytotoxic CD8 + T cells, reduced natural killer cell markers, and decreased expression of critical cytolytic factors such as GZMA and PRF129. This aligns with our own findings, where the baseline CDS tumor demonstrated an absence of immune cells, underscoring the immune cold phenotype of these tumors.

The dramatic shift in the tumor microenvironment following nivolumab and relatlimab treatment in this case underscores the potential for ICB to overcome the immune resistance posed by CDS. Post-treatment, we observed substantial infiltration of proliferative CD8 + T cells, indicative of an activated immune response. Previous studies have shown that increased intratumoral lymphocyte density, particularly of CD8 + T cells, is associated with improved survival in several cancer types, reinforcing the importance of immune activation in achieving therapeutic benefit30,31,32.

The unique contribution to response of LAG-3 inhibition in this case remain unclear. LAG-3 has been shown to promote regulatory T cell activity and negatively regulate T-cell activation and proliferation, mechanisms that could contribute to immune evasion in this disease33. The combination of anti-PD-1 and anti-LAG-3 therapy has been validated in advanced melanoma, including in patients who had previously progressed on PD-1/PD-L1 blockade, regardless of PD-L1 or LAG-3 expression status34. However, few prospective studies have explored LAG-3 inhibition in sarcomas. A phase II basket trial evaluating spartalizumab with LAG525 (anti-LAG-3) in sarcoma patients reported a disease control rate of 40% at 24 weeks, though the specific histologic subtypes were not detailed35. These findings suggest that LAG-3 inhibition may have activity in select sarcomas.

Furthermore, evidence of T-cell exhaustion, marked by upregulation of inhibitory checkpoint receptors such as PD-1 and LAG-3, suggests prolonged engagement with tumor antigens, leading to T-cell dysfunction over time36. The co-expression of multiple inhibitory receptors is a well-established indicator of advanced T-cell exhaustion, typically observed in chronic antigen exposure37. This finding provides further support for the effectiveness of dual ICB in this case, as it highlights the transition from an initial immune activation phase to a state of T-cell exhaustion. Combination ipilimumab and nivolumab in the second-line setting was able to partially rescue the patient and overcome this T cell exhaustion.

This study has some limitations. First, while the case demonstrates a notable response to doublet ICB, it represents a single-patient observation, and broader conclusions about the efficacy of ICB in CDS cannot be drawn without further clinical investigation. Additionally, IHC analysis of the tumor microenvironment was limited by tissue availability, particularly in pre-treatment samples, which were subject to tissue depletion from serial sectioning for IHC processing. As a result, larger, lower-power views were not available for all immune biomarkers, which may have affected the assessment of immune cell distribution.

In conclusion, this is the first documented case demonstrating that dual PD-1/LAG-3 blockade can induce a meaningful antitumor immune response in CDS, leading to an exceptional clinical outcome. Whether this response represents an isolated case or whether a subset of CDS may benefit from ICB remains to be determined. However, these findings pave the way for further investigation into the specific contributions of PD-1/LAG-3 blockade to tumor microenvironment remodeling. Given the favorable safety and tolerability profile observed, nivolumab and relatlimab are promising candidates for future combination strategies in clinical studies of CDS and other immune-resistant tumors.

Methods

Patient consent

The patient provided written informed consent for her de-identified health information to be used in this report and for publication. She further consented to an Institutional Review Board approved protocol to perform tumor sequencing at Memorial Sloan Kettering. All physicians involved in this report complied with all relevant ethical regulations in patient interactions, in line with ethical norms and standards in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Immunohistochemical stain

Standard IHC was performed on 5-µm-thick sections from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue utilizing antibodies for ERG, CD3, CD8, FOXP3, PD-L1, PD1, LAG-3, and Ki67. All baseline and on-treatment slides were reviewed by a pathologist. The antibodies, clones, sources, and staining conditions were as follows:

-

ERG (Clone EPR 3864, Ventana) – 1:5 dilution from ready-to-use formulation

-

CD3 (Clone LN10, Leica Biosystems) – 1:300 dilution

-

CD8 (Clone CD/144B, DAKO) – 1:1000 dilution

-

FOXP3 (Clone 236 A/E7, Abcam) – 1:500 dilution

-

PD-L1 (Clone E1L3N, Cell Signaling) – 1:200 dilution

-

PD-1 (Clone NAT 105, Abcam) – 1:100 dilution

-

LAG-3 (Clone 17B4, GeneTex) – 1:1000 dilution

-

Ki-67 (Clone MIB-1, DAKO) – 1:1000 dilution

All antibodies underwent 30-minute incubation at room temperature. Staining was conducted using a DAB detection kit (Leica Biosystems) following heat-induced epitope retrieval for 30 minutes in ER2 buffer.

Next generation sequencing

Targeted next generation sequencing on 505 cancer-related genes (MSK-IMPACT version 505) was performed on FFPE tissue blocks of the tumor and matched peripheral blood as previously described38,39. MSK- IMPACT505 is a hybridization capture-based next-generation sequencing platform of 505 exons and select introns, depending on the assay version. Genomic alterations were annotated using the OncoKB precision oncology knowledge base to identify functionally relevant variants. Variants of unknown significance (variants without annotation of predicted, likely, or known oncogenic relevance) were excluded from the analysis unless a gene was altered in the patient population at a high frequency (>15% of patients). Although not annotated as functionally relevant previously, we hypothesized that such genes may be relevant in this population of patients with a rare sarcoma. TMB was computed as total number of nonsynonymous mutations divided by total number of base pairs sequenced. Detection of copy number alterations was performed as previously described40. The following criteria were used to determine significance of whole-gene gain: fold change (FC) ≥ 2.0 (amplification), FC ≥ 1.5 but <2 (copy number gain/borderline amplification), with P < 0.05. Copy number gains are interpreted along with overall copy number profile and tumor purity.

RNA sequencing

Baseline tumor sample were tested for RNA-level fusions using the MSK-Fusion panel, an RNA sequencing panel via a next generation sequencing platform that uses anchored multiplex PCR (via the Archer platform) as previously described41.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

Sbaraglia, M., Bellan, E. & Dei Tos, A. P. The 2020 WHO Classification of Soft Tissue Tumours: news and perspectives. Pathologica 113, 70–84 (2021).

Mancarella, C., Carrabotta, M., Toracchio, L. & Scotlandi, K. CIC-Rearranged Sarcomas: An Intriguing Entity That May Lead the Way to the Comprehension of More Common Cancers. Cancers (Basel);14 (In eng). https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14215411. (2022).

Grünewald, T. G. P. et al. Ewing sarcoma. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 4, 5 (2018).

Antonescu, C. Round cell sarcomas beyond Ewing: emerging entities. Histopathology 64, 26–37 (2014).

Palmerini, E. et al. A global collaboRAtive study of CIC-rearranged, BCOR::CCNB3-rearranged and other ultra-rare unclassified undifferentiated small round cell sarcomas (GRACefUl). Eur. J. Cancer 183, 11–23 (2023).

Antonescu, C. R. et al. Sarcomas With CIC-rearrangements Are a Distinct Pathologic Entity With Aggressive Outcome: A Clinicopathologic and Molecular Study of 115 Cases. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 41, 941–949 (2017).

Yoshida, A. et al. CIC-rearranged Sarcomas: A Study of 20 Cases and Comparisons With Ewing Sarcomas. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 40, 313–323 (2016).

Connolly, E. A. et al. Systemic treatments and outcomes in CIC-rearranged Sarcoma: A national multi-centre clinicopathological series and literature review. Cancer Med 11, 1805–1816 (2022).

Murphy, J. et al. Clinical outcomes of patients with CIC-rearranged sarcoma: a single institution retrospective analysis. J. Cancer Res Clin. Oncol. 150, 112 (2024).

Tawbi, H. A. et al. Pembrolizumab in advanced soft-tissue sarcoma and bone sarcoma (SARC028): a multicentre, two-cohort, single-arm, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 18, 1493–1501 (2017).

Boye, K. et al. Pembrolizumab in advanced osteosarcoma: results of a single-arm, open-label, phase 2 trial. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 70, 2617–2624 (2021).

Blay, J. Y. et al. Pembrolizumab in patients with rare and ultra-rare sarcomas (AcSé Pembrolizumab): analysis of a subgroup from a non-randomised, open-label, phase 2, basket trial. Lancet Oncol. 24, 892–902 (2023).

Chen, J. L. et al. A multicenter phase II study of nivolumab +/- ipilimumab for patients with metastatic sarcoma (Alliance A091401): Results of expansion cohorts. J. Clin. Oncol. 38, 11511–11511 (2024).

NCI clinical trial leads to atezolizumab approval for advanced alveolar soft part sarcoma. National Cancer Institute. (https://www.cancer.gov/news-events/press-releases/2022/nci-trial-atezolizumab-approval-alveolar-soft-part-sarcoma).

Hindi, N. et al. Efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors in alveolar soft-part sarcoma: results from a retrospective worldwide registry. ESMO Open 8, 102045 (2023).

D’Angelo, S. P. et al. Afamitresgene autoleucel for advanced synovial sarcoma and myxoid round cell liposarcoma (SPEARHEAD-1): an international, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet 403, 1460–1471 (2024).

FDA Approves First Gene Therapy to Treat Adults with Metastatic Synovial Sarcoma. FDA. 8/2/24 (https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-first-gene-therapy-treat-adults-metastatic-synovial-sarcoma).

D’Angelo, S. P. et al. Nivolumab with or without ipilimumab treatment for metastatic sarcoma (Alliance A091401): two open-label, non-comparative, randomised, phase 2 trials. Lancet Oncol. 19, 416–426 (2018).

D’Angelo, S. P. et al. Pilot study of bempegaldesleukin in combination with nivolumab in patients with metastatic sarcoma. Nat. Commun. 13, 3477 (2022).

Wong, D. & Yip, S. Making heads or tails – the emergence of capicua (CIC) as an important multifunctional tumour suppressor. J. Pathol. 250, 532–540 (2020).

Simón-Carrasco, L., Jiménez, G., Barbacid, M. & Drosten, M. The Capicua tumor suppressor: a gatekeeper of Ras signaling in development and cancer. Cell Cycle 17, 702–711 (2018).

Kim, J. W., Ponce, R. K. & Okimoto, R. A. Capicua in Human Cancer. Trends Cancer 7, 77–86 (2021).

Ahmad, S. T. et al. Capicua regulates neural stem cell proliferation and lineage specification through control of Ets factors. Nat. Commun. 10, 2000 (2019).

Yang, R. et al. Cic Loss Promotes Gliomagenesis via Aberrant Neural Stem Cell Proliferation and Differentiation. Cancer Res. 77, 6097–6108 (2017).

Hendrickson, P. G. et al. Spontaneous expression of the CIC::DUX4 fusion oncoprotein from a conditional allele potently drives sarcoma formation in genetically engineered mice. Oncogene 43, 1223–1230 (2024).

Mocciaro, E., Runfola, V., Ghezzi, P., Pannese, M. & Gabellini, D. DUX4 Role in Normal Physiology and in FSHD Muscular Dystrophy. Cells 10, 3322 (2021).

Xu, H. et al. Dux4 induces cell cycle arrest at G1 phase through upregulation of p21 expression. Biochem Biophys. Res Commun. 446, 235–240 (2014).

Shadle, S. C. et al. DUX4-induced dsRNA and MYC mRNA stabilization activate apoptotic pathways in human cell models of facioscapulohumeral dystrophy. PLoS Genet 13, e1006658 (2017).

Chew, G. L. et al. DUX4 Suppresses MHC Class I to Promote Cancer Immune Evasion and Resistance to Checkpoint Blockade. Dev. Cell 50, 658–671.e7 (2019).

Mauldin, I. S. et al. Proliferating CD8(+) T Cell Infiltrates Are Associated with Improved Survival in Glioblastoma. Cells 10, 3378 (2021).

Nakano, O. et al. Proliferative activity of intratumoral CD8(+) T-lymphocytes as a prognostic factor in human renal cell carcinoma: clinicopathologic demonstration of antitumor immunity. Cancer Res 61, 5132–5136 (2001).

St Paul, M. & Ohashi, P. S. The Roles of CD8(+) T Cell Subsets in Antitumor Immunity. Trends Cell Biol. 30, 695–704 (2020).

Workman, C. J. & Vignali, D. A. Negative regulation of T cell homeostasis by lymphocyte activation gene-3 (CD223). J. Immunol. 174, 688–695 (2005).

Ascierto, P. A. et al. Nivolumab and Relatlimab in Patients With Advanced Melanoma That Had Progressed on Anti-Programmed Death-1/Programmed Death Ligand 1 Therapy: Results From the Phase I/IIa RELATIVITY-020 Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 41, 2724–2735 (2023).

Uboha, N. V. et al. Phase II study of spartalizumab (PDR001) and LAG525 in advanced solid tumors and hematologic malignancies. J. Clin. Oncol. 37, 2553–2553 (2019).

Thommen, D. S. & Schumacher, T. N. T Cell Dysfunction in Cancer. Cancer Cell 33, 547–562 (2018).

Zarour, H. M. Reversing T-cell Dysfunction and Exhaustion in Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res 22, 1856–1864 (2016).

Cheng, D. T. et al. Memorial Sloan Kettering-Integrated Mutation Profiling of Actionable Cancer Targets (MSK-IMPACT): A Hybridization Capture-Based Next-Generation Sequencing Clinical Assay for Solid Tumor Molecular Oncology. J. Mol. Diagn. 17, 251–264 (2015).

Zehir, A. et al. Mutational landscape of metastatic cancer revealed from prospective clinical sequencing of 10,000 patients. Nat. Med 23, 703–713 (2017).

Ross, D. S. et al. Next-Generation Assessment of Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2 (ERBB2) Amplification Status: Clinical Validation in the Context of a Hybrid Capture-Based, Comprehensive Solid Tumor Genomic Profiling Assay. J. Mol. Diagn. 19, 244–254 (2017).

Zheng, Z. et al. Anchored multiplex PCR for targeted next-generation sequencing. Nat. Med 20, 1479–1484 (2014).

Acknowledgements

This research was funded in part through the NIH/NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA008748.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

O.B.- Conceptualization, formal analysis, writing-original draft, visualization, project administration, writing-review and editing. S.C. - visualization, writing-original draft, writing-review and editing. C.A. - Data curation, formal analysis, writing-review and editing. M.B. - Visualization, formal analysis, writing-review and editing. B.O. - Visualization, formal analysis, writing-review and editing. I.K. - Formal analysis. E.B., P.M., K.A., M.G., E.R. - writing-review and editing. W.T., S.D. - supervision, writing-review and editing. C.K. - Conceptualization, supervision, writing-original draft, writing-review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Babatunde, O.O., Coca Membribes, S., Anthonescu, C. et al. Immunologic correlates in a CIC::DUX4 fusion-positive sarcoma responsive to dual immune checkpoint blockade. npj Precis. Onc. 9, 85 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41698-025-00878-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41698-025-00878-w

This article is cited by

-

Modeling CIC::DUX4 sarcoma reveals oncogene-mediated MHCI-dependent immune evasion

Molecular Cancer (2025)