Abstract

Resistance to CDK4/6 inhibitors (CDK4/6i) is a major challenge in treating hormone receptor-positive, HER2-negative metastatic breast cancer. This study aimed to identify a biomarker predictive of resistance that could also serve as a therapeutic target. Circulating IL-6 levels in 166 patients significantly increased at progression, making IL-6 a non-invasive biomarker to predict CDK4/6i resistance. Knockdown of IL-6 re-sensitized resistant cells to palbociclib and endocrine therapy, underscoring IL-6’s critical role in maintaining resistance. Patient-derived xenograft models from patients who progressed within 3 months versus ≥6 months of palbociclib therapy revealed distinct transcriptomic profiles, with later progressors exhibiting IL-6/STAT3 activation, epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition, and immune evasion signatures. Treatment with TTI-101, a STAT3 inhibitor, significantly reduced tumor growth and improved survival in these models, providing preclinical validation for targeting the IL-6/STAT3 axis. These findings support using IL-6 to guide personalized treatment and combining STAT3 inhibitors with CDK4/6i as a transformative strategy to overcome resistance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

CDK4/6 inhibitors (CDK4/6i) such as palbociclib, ribociclib, and abemaciclib are now standard of care treatment for patients with advanced estrogen receptor (ER)-positive (ER + ) breast cancer. CKD4/6is are used in combination with aromatase inhibitors as first-line treatment or with fulvestrant as first- or second-line therapy1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9. Extended follow-up data have shown an overall survival benefit with ribociclib and abemaciclib, whereas results for palbociclib have been less consistent10,11,12,13,14. Although initial responses and disease control are commonly seen with CDK4/6is, the eventual development of resistance limits their long-term efficacy. Dissecting the associated mechanisms of resistance is a critical unmet need. Moreover, identification of biomarkers that are predictive of which tumors will respond to CDK4/6i, as well as targetable biomarkers that can be readily measured in real-time, will be instrumental in advancing treatment regimens for patients with breast cancer presenting with metastatic disease.

There has been tremendous effort focused on determining genetic drivers of resistance to CDK4/6is that could be used as predictive markers15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23. However, none of these mutations can differentiate responders from those patients who progress on treatment. This was further exemplified in the recent exploratory biomarker analysis of the postMONARCH trial showing that neither of the most common mutations in HR + /HER2-negative (HER2-) breast cancer patients, ESR1 or PIK3CA, could differentiate response to abemaciclib17. It is an unavoidable challenge that all patients with this common form of advanced breast cancer will eventually develop resistance to treatment, underscoring the urgent need to identify biomarkers that can predict treatment response. Liquid biopsy of blood provides the advantages of ease of sampling, which can be carried out longitudinally providing information about when to intervene, and potentially represents the heterogeneity of the tumor. Therefore, a targetable biomarker in blood provides information about when to intervene and a potential intervention strategy.

A key feature of CDK4/6 inhibition is the cell cycle inhibitory response it elicits through induction of senescence, from which cells can escape and thus readily re-enter the cell cycle as soon as the drug is withdrawn24,25. Senescent cells secrete interleukins, inflammatory cytokines, and growth factors, which comprise the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP), which affects surrounding cells and promotes tumor growth. The most prominent SASP cytokine is interleukin-6 (IL-6), which is associated with metastasis, tumor aggressiveness, and decreased survival26. IL-6 exerts its effects through the activation of downstream signaling cascades, notably the signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) pathway. IL-6, a pleiotropic cytokine primarily produced by immune cells, acts through a classic signaling pathway involving the IL-6 receptor (IL-6R) and glycoprotein 130 (gp130). Upon ligand binding, the IL-6/IL-6R complex triggers the dimerization of gp130 and subsequent activation of Janus kinases (JAKs), leading to phosphorylation of STAT3 on tyrosine (Y) 704. Tyrosine phosphorylated STAT3 (pYSTAT3) forms homodimers or heterodimers and translocates to the nucleus, where it modulates the transcription of genes implicated in cell proliferation, survival, and immune evasion27,28. This canonical IL-6/STAT3 signaling axis has been implicated in the pathogenesis of various malignancies, including breast cancer, by promoting tumor cell proliferation, epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), angiogenesis, and immune evasion28. Moreover, aberrant activation of STAT3 has been associated with poor prognosis and resistance to conventional therapies in patients with breast cancer28.

Recently, we reported that the IL-6/STAT3 pathway is induced in in vitro models of acquired palbociclib resistance in ER + /HER2- breast cancer29. Multi-omic analyses of the resistant cells revealed significant downregulation of estrogen response and upregulation of EMT and stem-like pathways (IL-6/STAT3, Notch, Wnt). We also showed that exogenous treatment with IL-6 in otherwise sensitive parental cells increased resistance to tamoxifen, fulvestrant, and palbociclib, suggesting a direct role of IL-6 in these resistance mechanisms. Our findings suggest that IL-6/STAT3 pathway activation mediates palbociclib resistance that could be targeted by STAT3 inhibitors29 and could serve as a biomarker.

In the present study, we investigated the utility of circulating IL-6 as a predictive biomarker for identifying patients who are most likely to benefit from CDK4/6i treatments. Additionally, we evaluated the efficacy of TTI-101, an investigational STAT3 inhibitor, in blocking IL-6–induced STAT3 activation and tumor growth in several patient-derived xenograft models of metastatic ER+ breast cancer from patients whose tumors progressed on treatment with CDK4/6i. We tested the hypothesis that TTI-101 sensitizes CDK4/6i-resistant breast cancer cells by disrupting IL-6–mediated STAT3 signaling pathways crucial for tumor cell survival and proliferation. Additionally, we evaluated the utility of IL-6 as a predictive biomarker for identifying patients most likely to benefit from. By establishing IL-6 as a potential biomarker, we aim to promote personalized treatment strategies, including combination therapy with CDK4/6i and TTI-101, to improve clinical outcomes and overcome therapeutic resistance in patients with breast cancer.

Results

Plasma IL-6 as a marker of disease progression in patients with HR + /HER2- metastatic breast cancer treated with palbociclib and endocrine therapy

To evaluate dynamic biomarker changes during disease progression, we prospectively collected blood samples from 166 patients with HR + /HER2− metastatic breast cancer. Of these, 85 samples were collected at baseline, prior to CDK4/6i therapy, and 65 were collected at the time of radiographic disease progression while still on therapy (Figure. S1A, Table 1). A small control cohort of 16 patients with treatment-naïve early-stage (stage I–II) HR + /HER2− breast cancer provided additional baseline comparison, with samples collected at surgical resection. Plasma IL-6 levels were quantified using the Human IL-6 Quantikine ELISA Kit (R&D Systems).

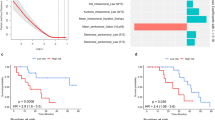

Mean IL-6 levels at baseline were 4.4 pg/mL (range 0–17.7), which rose significantly at progression (mean 10 pg/mL, range 1.15–54.02; p = 0.0004; Table 1, Fig. 1A). In the early-stage cohort, IL-6 levels were lower than that of the patients with newly diagnosed metastatic disease and baseline samples, with a mean value of 1.49 pg/mL (range 0.40–3.52 pg/mL; Fig. 1A). Using a 5 pg/mL threshold—representative of upper-normal IL-6 levels in healthy adults30, —we compared subsets of baseline (n = 29) and progression (n = 36) samples exceeding this cutoff. IL-6 levels were significantly higher at progression (mean 17.16 pg/mL, range 6.65–54.06) than at baseline (mean 7.91 pg/mL, range 5.08–17.0; p = 0.001; Fig. 1B).

A Plasma IL-6 levels measured by ELISA from patients with HR + /HER2- metastatic breast cancer (MBC) just prior to treatment with CDK4/6 inhibitors (CDK4/6i; pre, n = 85) or at the time of progression while receiving CDK4/6i (post, n = 65), and in plasma samples from patients with early-stage (stage I-II) treatment (Rx)-naïve HR + /HER2- breast cancer (n = 16). Dashed line represents the concentration (conc) 5 pg/mL; the normal range for IL-6 levels in healthy adults is less than 5 pg/mL. B Distribution of plasma IL-6 levels shown in A for a subset pre (n = 28) and post (n = 36) CDK4/6i samples in which IL-6 levels were above 5 pg/mL. C IL-6 levels in matched plasma collected before and after CDK4/6i. Time to progression indicated in months next to the patient ID. D Range of plasma IL-6 levels in patients with clinically stable HR + MBC during treatment with CDK4/6i at the indicated time intervals (in months). E Plasma levels of CA153 in matched samples collected before and after CDK4/6i therapy. Time to progression indicated in months next to the patient ID. F CA153 plasma levels in samples from pre (n = 32) and post (n = 27) CDK4/6i. G Quantification (left panel) and representative images (right panel) of pSTAT3 (Y705) immunohistochemical staining at the start of treatment (pre CDK4/6i) or at the time of progression (post CDK4/6i). One patient (PA139) had a matched pre and post biopsy. H Levels of IP-10 (CXCL10), MCP-1 (CCL2), and MCP-2 (CCL8) as measured by Luminex assay of plasma samples collected before CDK4/6i (n = 53) or after CDK4/6i (n = 35) or with treatment naïve early-stage breast cancer (n = 16). I Results from H for matched samples collected before and after CDK4/6i therapy. Time to progression is indicated in months next to the patient ID. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

Among 11 patients with matched pre- and post-treatment samples, IL-6 rose significantly in all but one case at progression (baseline range: 1.57–6.45 pg/mL; progression range: 2.5–45.44 pg/mL; p = 0.005; Fig. 1C). In a smaller longitudinal subset (n = 4), IL-6 levels steadily increased during treatment, peaking prior to radiographic progression (Figure. S1B). These findings suggest that IL-6 upregulation precedes overt clinical relapse and may serve as an early biomarker of resistance onset. In contrast, IL-6 levels remained stable in patients with prolonged disease control on CDK4/6i (n = 43; mean ~5 pg/mL, range 0–19.75; Fig. 1D). These data suggest IL-6 elevation may precede overt progression and serve as an early biomarker of emerging resistance.

To examine causality, we previously showed that exogenous IL-6 induces hallmark features of resistance in palbociclib-sensitive HR+ breast cancer cells, including ERα loss, stem-like phenotype enrichment, migration, and FOXA1 upregulation29. These cells developed resistance to both palbociclib and fulvestrant, which was reversible with the STAT3 inhibitor TTI-101, implicating IL-6/STAT3 signaling as mechanistically critical.

To define the timing of IL-6 induction during resistance development, we used a previously published stepwise resistance model31 involving escalating palbociclib exposure (0.3–5 µM). IL-6 secretion progressively increased with drug dose, and p-STAT3 became detectable at 1.2 µM, remaining elevated even after drug withdrawal in cells exposed to ≥2.4 µM palbociclib (Figure. S3D), indicating stable pathway activation independent of continued treatment.

Together, our patient-based longitudinal data, mechanistic in vitro models, and stepwise resistance studies support a framework in which IL-6 acts as an early and essential driver of CDK4/6i resistance through activation of STAT3, providing a strong rationale for therapeutic targeting of this axis in HR + /HER2–metastatic breast cancer.

We next compared clinical and pathologic characteristics between the baseline and disease progression cohorts and found no significant differences in race, age, menopausal status, or receptor status (Table 1). The only factor significantly different at progression was IL-6, both in continuous values and when categorized as high ( > 5 pg/mL) or low ( ≤ 5 pg/mL; Table 1). Within the progression cohort, clinical features did not differ significantly between patients with high versus low IL-6 levels (Data S1).

To assess whether other serum biomarkers could reflect progression, we measured CA15.3 in 12 patients with matched samples. CA15.3 increased in 6 and decreased in 6, with no statistical significance (Fig. 1E). Expanding the analysis (pre-CDK4/6i, n = 43; post-CDK4/6i, n = 37) confirmed no significant difference (pre-treatment mean: 232.5 U/mL; post-treatment mean: 240.1 U/mL; Fig. 1F), indicating CA15.3 is not a reliable progression marker during CDK4/6i therapy.

We next examined functional evidence of IL-6 activity by assessing STAT3 phosphorylation in pre- and post-treatment tumor biopsies. In a previous study, we observed increased pY-STAT3 in post-treatment biopsy samples compared with pre-treatment samples in a small retrospective cohort (n = 25)29. To validate these findings prospectively, we collected 70 pre- and 21 post-CDK4/6i treatment tumor biopsies (Fig. 1G). The percentage of pY-STAT3–positive cells was significantly higher at disease progression (mean 8.3%, range 0–50%) compared with baseline (mean 3.6%, range 0–20%; p = 0.02), as shown by representative immunohistochemistry images (Fig. 1G). In one representative patient (PA139), who received palbociclib plus letrozole for 8.5 months, pY-STAT3 levels markedly increased at disease progression (Fig. 1G).

To further evaluate the relationship between IL-6 levels and STAT3 activation in patients, we performed a correlation analysis using matched tumor biopsies and serum samples from patients before and after CDK4/6i therapy. As shown in Figure. S1C, post-treatment biopsies taken at the time of progression exhibited a statistically significant positive correlation between circulating IL-6 and tumor pSTAT3 levels (p = 0.04), suggesting engagement of the IL-6/STAT3 axis in the resistant setting. In contrast, no correlation was observed in the pre-treatment biopsies (p = 0.57), indicating that this signaling pathway is not active prior to therapy. These findings support our proposed model in which IL-6 upregulation during CDK4/6 inhibitor treatment promotes STAT3 activation, contributing to the emergence of resistance.

To expand our understanding of cytokine changes at progression, we used the ProcartaPlex Human Immune Monitoring 65-plex Panel to profile plasma from 53 pre-treatment, 35 post-treatment, and 16 early-stage patients. Five cytokines—CXCL10 (IP-10), CCL2 (MCP-1), CCL8 (MCP-2), IL-18, and HGF—were significantly elevated at progression (Fig. 1H & Figure S1D).

IP-10 (CXCL10)

IP-10 is known to promote tumor cell proliferation and invasion32; its mean levels were significantly lower in the early-stage cohort (36.57 pg/mL) and pre-CDK4/6i cohort (27.6 pg/mL) than in the cohort with disease progression on CDK4/6i treatment (45.57 pg/mL, p = 0.0001; Fig. 1H). Among eight matched samples between before and after treatment, six showed an increase (Fig. 1I).

MCP-1 (CCL2)

MCP-1 is involved in STAT3-mediated cancer stem-like features33; its mean levels were lower in the early-stage cohort (108.6 pg/mL) and pre-CDK4/6i cohort (112.7 pg/mL) than in the cohort with disease progression on CDK4/6i treatment (167.4 pg/mL; pre vs post p = 0.002), with six of eight matched samples showing an increase (Fig. 1H, I).

MCP-2 (CCL8)

MCP-2 is associated with driving breast cancer metastasis34; its mean levels were lower in the early-stage cohort (8.03 pg/mL) and pre-CDK4/6i cohort (7.99 pg/mL) than in the cohort with disease progression on CDK4/6i treatment (11.21 pg/mL; pre vs post p = 0.0007), with seven of eight matched samples showing an increase (Fig. 1H, I).

IL-18

IL-18 is a pro-inflammatory cytokine linked to breast cancer cell migration35; its mean levels were lower in the early-stage cohort (24.02 pg/mL) and pre-CDK4/6i cohort (24.69 pg/mL) than in the cohort with disease progression on CDK4/6i treatment (33.74 pg/mL; pre vs post p = 0.0005; Figure. S1D & E).

HGF

HGF is known to affect tumor progression36; its mean levels were lower in the early-stage cohort (71.5 pg/mL) and pre-CDK4/6i cohort (75.9 pg/mL) than in the cohort with disease progression on CDK4/6i treatment (104.8 pg/mL; pre vs post p = 0.005; Figure. S1D & E).

All five cytokines showed positive correlations with IL-6 levels (Figure. S1F), indicating that IL-6 upregulation is part of a broader, co-activated inflammatory network that promotes tumor progression and contributes to disease progression in patients with CDK4/6i resistance breast cancer.

Genomic alterations are heterogeneous at progression in patients with HR + /HER2- metastatic breast cancer receiving palbociclib and endocrine therapy

Given that current treatment strategies after progression on CDK4/6 inhibitors often depend on identifying actionable genomic alterations, we examined the mutational landscape in 39 of 53 patients who progressed while receiving palbociclib plus endocrine therapy (ET). Mutation data were visualized using an oncoprint, with genes ranked from most to least frequently mutated. The percentage of patients harboring each alteration is shown on the right side of the plot (Fig. 2A).

A Oncoprint based on the mutation data. Genes are sorted by mutation frequency from high to low with the percentage of samples with that alteration indicated on the right side of the plot and grouped based on if plasma IL-6 levels were high (greater than 5 pg/mL) or low (less than 5 pg/mL) at the time of disease progression. B Total number of alterations between IL-6 high (greater than 5 pg/mL) and low (less than 5 pg/mL) groups using the t test (p = 0.13) and Wilcoxon rank-sum test (p = 0.37). C Correlation of plasma IL-6 levels at the time of disease progression to total number of alterations. Pearson and Spearman correlation coefficients were not significant (p = 0.11 and p = 0.19, respectively).

Our analysis revealed that PIK3CA was the most commonly mutated gene, with missense mutations detected in 51% of patients. ESR1 and TP53 mutations were also prevalent, found in 44% and 36% of patients, respectively. To explore the relationship between genomic alterations and IL-6 levels at progression, we ordered samples based on IL-6 levels and compared mutation profiles between patients with high IL-6 levels (greater than 5 pg/mL) and low IL-6 levels (less than 5 pg/mL). Notably, we did not observe any consistent pattern of genomic alterations that correlated with elevated IL-6 levels at disease progression (Fig. 2A).

Additionally, statistical analysis showed that the total number of genomic alterations did not significantly differ between the IL-6 high and low groups, as indicated by both the t test (p = 0.13) and the Wilcoxon rank-sum test (p = 0.37; Fig. 2B). To further investigate, we assessed whether there was a correlation between IL-6 levels at disease progression and the total number of mutations. Neither Pearson nor Spearman correlation coefficients were significant (p = 0.11 and p = 0.19, respectively; Fig. 2C).

These findings underscore the heterogeneous nature of genomic alterations at disease progression, which appear to be highly patient-specific rather than driven by common mutational events associated with IL-6 elevation. Since all mutational data were derived from baseline tumor samples collected prior to CDK4/6i therapy, our analysis specifically examined whether pre-existing genomic features could predict the emergence of high IL-6 levels at progression. The absence of such associations suggests that IL-6 upregulation likely arises through non-genomic mechanisms activated during therapy, such as inflammatory signaling, transcriptional reprogramming, or microenvironmental remodeling. Taken together, these data suggest that mutational profiling alone may be insufficient to identify patients at risk for inflammatory, IL-6–driven resistance. Instead, incorporating dynamic non-genomic biomarkers like IL-6 may offer a more informative strategy for therapeutic stratification following progression on CDK4/6is.

Downregulation of IL-6 re-sensitizes palbociclib-resistant HR+ breast cancer cells to palbociclib and endocrine therapy

To investigate the role of IL-6 and pY-STAT3 as functional predictive biomarkers—and to provide a preclinical rationale for targeting STAT3 in patients with CDK4/6i resistance—we knocked down IL-6 using two distinct shRNA constructs (shIL-6 #1 and shIL-6 #2) in both parental (Par) and palbociclib-resistant (Res) MCF7 and T47D hormone receptor–positive breast cancer cells. Knockdown efficiency was confirmed at the mRNA level (Fig. 3A &Figure S2A) and via analysis of its downstream target, STAT3 (Fig. 3B &Figure S2B). In parental cells, which exhibited already low baseline IL-6 expression, shRNA knockdown produced only a modest mRNA reduction (Fig. 3A &Figure S2A). In contrast, resistant cells, which displayed elevated IL-6 expression, showed marked reductions in both IL-6 and STAT3 mRNA levels following knockdown (Fig. 3B &Figure S2B).

A Relative gene expression of IL-6 by quantitative (q)RT-PCR analysis in MCF7 parental (Par) and resistant (Res) cell lines after shRNA knockdown of IL-6 by one of two clones (shIL-6 #1 and shIL-6 #2) or control scrambled shRNA (shSCR). Cells were grown in culture for 3 days. B Relative gene expression of STAT3 by qRT-PCR analysis. C Secreted IL-6 levels measured by ELISA and normalized based on the number of cells (relative concentration [conc]). D Western blot analysis of pSTAT3 (Y705) and total STAT3 after 3 days in culture. E Dose-response curves of treatment with 0.01–12 μM palbociclib for 6 days followed by 6 days of recovery compared with MCF7 Par shSCR. Number of cells/growth was assessed using the crystal violet assay. Data were normalized to DMSO (100%), plotted, and analyzed using nonlinear regression on GraphPad Prism 9. Dashed line and bar graphs depict half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) values. F Dose-response curves after 24 h of estrogen deprivation followed by re-addition of 10 nM beta-estradiol and treatment with varying concentrations (0.01–12 μM) of fulvestrant for 2 days compared with MCF7 Par shSCR. Number of cells/growth was assessed using the crystal violet assay as in panel E. G Dose-response curves with 0.01–12 μM TTI-101 for 3 days followed by 9 days of recovery. Number of cells/growth was assessed using the crystal violet assay as in panel (E). H qRT-PCR analysis of estrogen responsive genes—ER and PgR. I qRT-PCR analysis of epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) markers N-cadherin and Vimentin. J qRT-PCR analysis of transcription factors related to breast cancer stem cell-like markers CD44 and ALDH1. K Western blot analysis of estrogen receptor (ERa), PgR, EMT markers, and G1/S transition proteins. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001.

ELISA analysis further confirmed a significant reduction in IL-6 protein secretion in both parental and resistant cells (Fig. 3C &Figure S2C), and immunoblotting demonstrated a decrease in pSTAT3/STAT3 protein levels in resistant cells (Fig. 3D &Figure S2D). The apparent disconnect between IL-6 mRNA and protein changes in parental cells reflects the extremely low baseline transcript levels, which are near the detection threshold of qPCR. Thus, functional suppression was more clearly captured at the protein level, aligning with prior studies showing that IL-6 expression is tightly regulated post-transcriptionally, and protein levels may better reflect biological activity than mRNA alone37.

Next, we assessed whether IL-6 knockdown influenced cell proliferation. Doubling times in IL-6 knockdown–resistant cells were not significantly different from scrambled shRNA (shSCR) controls—2.6 vs. 2.3 days for MCF7 and 2.7 vs. 2.5 days for T47D cells, respectively (Figure. S3E). However, despite unchanged proliferation rates, dose-response analyses showed that IL-6 knockdown re-sensitized resistant cells to both palbociclib and ET. Specifically, the IC50 for palbociclib decreased 2- to 4-fold (Res shSCR = 7.2–7.8 µM; Res shIL-6 #1 = 2.5–3.3 µM; Res shIL-6 #2 = 2.3–2.7 µM; Fig. 3E &Figure S2F), while fulvestrant IC50s were reduced 2- to 3-fold (Res shSCR = 4.8–6.1 µM; Res shIL-6 #1 = 1.2–2.1 µM; Res shIL-6 #2 = 1.2–2.4 µM; Fig. 3F &Figure S2G). Nonetheless, full sensitivity was not restored to the level of parental cells (palbociclib IC50 = 0.75 µM; fulvestrant IC50 = 0.3 µM).

Interestingly, IL-6 knockdown caused an 8- to 12-fold increase in resistance to the STAT3 inhibitor TTI-101 (Res shSCR = 0.59–1.04 µM; Res shIL-6 #1 = 3.3–7.2 µM; Res shIL-6 #2 = 3.4–8.3 µM; Fig. 3G &Figure S2H), suggesting a direct causal link between IL-6 suppression and reduced STAT3 dependency.

Given previous findings that IL-6 promotes EMT and downregulates ERα expression29, we further examined ER pathway signaling, EMT markers (N-cadherin, vimentin), and cancer stem-like cell markers (CD44, ALDH1) at the mRNA level. While ER mRNA remained unchanged, IL-6 knockdown significantly increased progesterone receptor (PgR) expression in both resistant cell lines (Fig. 3H &Figure S2I). Additionally, mRNA levels of EMT and stem-like markers were consistently reduced in IL-6 knockdown cells (Fig. 3I–J & Figure S2J–K), a finding supported by immunoblot analyses showing increased PgR protein and decreased N-cadherin and vimentin (Fig. 3K). However, IL-6 knockdown had no effect on G1/S transition regulators such as p27, Cyclin D1, Rb, and CDK2, which remained unchanged in both parental and resistant cells (Fig. 3K).

Together, these findings highlight IL-6 as a key mediator of CDK4/6i resistance through activation of STAT3 and induction of stem-like and EMT phenotypes. Downregulation of IL-6 restores sensitivity to both palbociclib and ET and modulates downstream resistance pathways, supporting the therapeutic targeting of the IL-6/STAT3 axis in resistant HR+ breast cancer.

Suppression of IL-6 in palbociclib-sensitive HR+ breast cancer cells delays resistance

CDK4/6is primarily exert their therapeutic effect by arresting cells in the G1 phase of the cell cycle, often triggering a senescence-like state. Senescent cells secrete a suite of cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors collectively termed the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP), which can modulate the tumor microenvironment in both pro- and anti-tumorigenic ways38. Among SASP components, IL-6 is a well-known inflammatory cytokine and established driver of tumor progression.

To explore the temporal dynamics of IL-6 induction during CDK4/6i therapy, we treated palbociclib-sensitive MCF7 parental cells with 1 µM palbociclib continuously for 21 days. Peak β-galactosidase activity, a classical marker of senescence, was observed around days 6–9 (Figure. S3A–C), whereas IL-6 mRNA expression and secretion increased later, continuing to rise through day 16 and reaching a > 20-fold elevation. These findings suggest that IL-6 is a delayed and sustained output of the senescence response, persisting after initial senescence markers decline.

To determine whether IL-6 contributes functionally to therapeutic escape, we generated IL-6 knockdown lines in MCF7 and T47D cells. IL-6 suppression significantly enhanced sensitivity to palbociclib, reducing the IC50 by 50–75% compared to control (Fig. 4A, C), while having no effect on fulvestrant response (Fig. 4B, D) or basal proliferation in the absence of therapy (Fig. 4E, F). Cell doubling times were unchanged over the 21-day period, indicating that IL-6 knockdown did not impair intrinsic growth but specifically enhanced sensitivity to CDK4/6 inhibition.

A, B Dose-response curves in MCF7 and T47D parental (Par) control scrambled shRNA (shSCR), shIL-6 #1, and shIL-6 #2 cells, depicting the effect of treatment with 0.01–12 μM palbociclib for 6 days followed by 6 days of recovery (A) and after 24 h of estrogen deprivation followed by re-addition of 10 nM beta-estradiol and treatment with varying concentrations (0.01–12 μM) of fulvestrant for 2 days (B). Dashed line depicts half-maximal inhibitor concentration (IC50) values. C, D Bar graphs depicting the average IC50 values in MCF7 and T47D parental shSCR, shIL-6 #1, and shIL-6 #2 cells treated with palbociclib (C) and fulvestrant (D) as indicated in A, B. E, F Doubling time every 3 days for 21 days showing the effect of shRNA knockdown of IL-6 on the proliferation of MCF7 and T47D parental cell lines. G, H MCF7 parental (G) and T47D (H) shSCR, shIL-6 #1, and shIL-6 #2 cells were treated with 1 μM palbociclib every 3 days for 21 days with measurements taken every 3 days as indicated in G for cell growth and IL-6 secreted protein levels (ELISA). I Representative images of senescence-associated ß-galactosidase (SA-βgal) staining in MCF7 parental shSCR, shIL-6 #1, and shIL-6 #2 cells treated with or without 1 μM palbociclib every 3 days for 21 days. Quantification of SA-βgal+ cells was calculated every 3 days relative to number of cells. J Representative images of SA-βgal staining in MCF7 resistant (Res) and T47D Res shSCR, shIL-6 #1, and shIL-6 #2 cells treated with or without 1 μM palbociclib every 3 days for 6 days. Quantification of SA-βgal+ cells was calculated at day 6 relative to number of cells. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

We next asked whether IL-6 suppression could delay or prevent resistance. When shIL-6 parental cells were continuously exposed to 1 µM palbociclib, they displayed durable growth suppression throughout the treatment period, while control shSCR cells showed a proliferative rebound after 15 days, consistent with acquired resistance (Fig. 4G, H). IL-6 levels remained low in shIL-6 cells but were elevated in control cells, reinforcing IL-6’s role in facilitating escape from CDK4/6i-induced arrest. However, closer inspection revealed that in 3 out of 4 IL-6 knockdown lines, a minor rebound in growth occurred between days 12–15, indicating that IL-6 suppression delays but does not completely prevent resistance.

To further validate this observation, we tested the effect of pharmacologic STAT3 inhibition, reasoning that IL-6’s resistance effects are mediated via STAT3 activation. Co-treatment of MCF7 and T47D parental cells with palbociclib and the STAT3 inhibitor TTI-101 resulted in sustained growth suppression with no evidence of rebound across the same time course (Figure. S3E-F). These results highlight the early and functional role of IL-6/STAT3 signaling in resistance onset and suggest that co-targeting this pathway can durably suppress proliferation under CDK4/6 inhibition.

We next examined whether IL-6 influences the senescence response directly. In parental MCF7 cells, IL-6 knockdown did not affect the initial senescence program, as β-galactosidase activity was comparable between shSCR and shIL-6 cells following palbociclib treatment (Fig. 4I). In contrast, resistant cells typically show attenuated β-galactosidase staining; however, IL-6 knockdown in this context restored β-galactosidase activity (Fig. 4J), suggesting that IL-6 actively suppresses re-induction of senescence in resistant cells.

These data support a model in which IL-6 is both a downstream product of therapy-induced senescence and a promoter of resistance. In early treatment phases, senescence triggers IL-6 expression, but as resistance emerges, IL-6 expression persists even after the senescent program subsides. This decoupling was evident in our stepwise resistance model31, in which IL-6 levels progressively rose with increasing palbociclib concentrations and remained elevated even after drug withdrawal (Figure. S3D).

Finally, although β-galactosidase activity is not a definitive marker of classical senescence, its restoration in IL-6–depleted resistant cells aligns with broader phenotypic reversion—including ERα re-expression and reversal of EMT markers (Figs. 3H–K and 4A–H)—consistent with a shift back to a drug-sensitive state. Together, these results position IL-6 as a central node in resistance, facilitating escape from CDK4/6i-induced senescence and promoting tumor persistence. Our findings also raise the possibility that a subpopulation of senescent-like cells may persist and secrete IL-6, driving resistance through paracrine, non–cell-autonomous mechanisms—an area warranting future investigation.

In summary, palbociclib resistance appears to emerge through a cascade of events initiated by therapy-induced senescence, followed by sustained IL-6 upregulation—characteristic of the SASP—which facilitates escape from cell cycle arrest and promotes cross-resistance to ET. These findings provide strong rationale for exploring IL-6 both as a predictive biomarker and as a therapeutic target in HR + /HER2− breast cancer patients receiving CDK4/6i-based regimens.

Transcriptomic signatures differ between PDX models derived from patients who progressed within 3 months versus after ≥ 6 months of palbociclib therapy

To translate our mechanistic findings to in vivo models, we employed four patient-derived xenograft (PDX) models of palbociclib resistance (PR-1 through PR-4), each representing distinct clinical timelines of resistance. PR-1 and PR-2 were generated from HR + , HER2-negative breast cancer patients who progressed after 6–16 months of palbociclib plus ET, while PR-3 and PR-4 were derived from patients who progressed within 2–4 months of therapy (Figure. S3A). Tumor growth kinetics across passages (P3 and P4; Fig. 5A–D) demonstrated that PR-1 and PR-2 grew more slowly than PR-3 and PR-4, requiring nearly twice as long to reach passage 4 (300 vs. 150–175 days; Fig. 5A, C). Average tumor doubling times further reflected this pattern, ranging from 8 to 22 days in PR-1 and PR-2 versus 4–11 days in PR-3 and PR-4 (Fig. 5B, D). These growth dynamics were mirrored by Ki67 immunohistochemistry (IHC), which confirmed reduced proliferative indices in PR-1 and PR-2 (Fig. 5E).

A Timeline and volume growth curves of tumor establishment in PDX models derived from patients who progressed after ≥6 months of CDK4/6 inhibitor therapy (PR-1 and PR-2). Tumors were passaged through transplantation to generate Passage 2 (P2),P3 and P4 tumors. B Doubling time of PR-1 and PR-2 tumors from P2 (n = 2), P3 (n = 3), and P4 (n = 3). C Timeline and volume growth curves of tumor establishment in the PDX models from patients who progressed within 3 months of CDK4/6i therapy (PR-3 and PR-4). D Doubling time of PR-3 and PR-4 tumors from P2 (n = 4), P3 (n = 3), and P4 (n = 4). E Representative images of hematoxylin and eosin (H and E) staining; immunohistochemical staining of hormone receptor status: ER, PgR, and HER2; and Ki67. F Total number of mutations in each PDX model identified by whole exome sequencing. G Venn diagram of the type of mutations shown in panel (F). H Hierarchical clustering heat map of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between PDX models derived from patients who progressed within 3 months of CDK4/6i therapy (yellow bar) and those who progressed after ≥6 months (green bar). RNA sequencing carried out on six tumors from each PR PDX model collected at P3 and P4. Red denotes genes with increased expression levels and blue indicates genes with decreased expression levels. I Volcano plot revealing 3386 upregulated (red) and 2829 downregulated (blue) significant DEGs in PDX models from patients who progressed after ≥6 months compared with those who progressed within 3 months. J Gene set enrichment analysis comparing PDX models from patients who progressed after ≥6 months vs. those who progressed within 3 months. Starred pathways overlap with those found in our previously published PR cell line models. K Average Spearman Correlation of PR PDX Models to the acquired resistance cell line signature (corresponding to ≥6-month progression). L Ward clustering heat map of the 50-gene signature for PAM50 subtyping of each PDX model or cell line. M Western blot analysis with the indicated antibodies from each PR PDX model collected at P3 and P4.

Immunoblotting and IHC validated the retention of original clinical pathology markers (ER, PgR, HER2) across all four models (Fig. 5E &Figure S3A–B). Whole exome sequencing (WES) revealed an ESR1 mutation in PR-1 but no PIK3CA mutations across the cohort (Data S2). Mutation burden was similar across all models (Fig. 5F), with only a single shared mutation between any two models (Fig. 5G), reinforcing the conclusion from our patient cohort (Fig. 2C) that genomic alterations alone are insufficient to account for resistance and cannot reliably inform treatment selection following CDK4/6i progression.

RNA-seq–based transcriptomic profiling uncovered distinct gene expression signatures between models derived from patients who progressed after ≥6 months of therapy (PR-1 and PR-2) and those who progressed within 3 months (PR-3 and PR-4). Principal component analysis (PCA) and unsupervised clustering segregated PR-1 and PR-2 from PR-3 and PR-4 (Fig. 5H & Figure S3C). Differential gene expression analysis identified 3,386 genes upregulated and 2829 downregulated in PR-1 and PR-2 compared to PR-3 and PR-4 (Fig. 5I, Data S3). Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) highlighted enrichment of IL-6/STAT3, EMT, and other inflammatory signaling pathways in the ≥6-month progression models (PR-1 and PR-2), whereas the <3-month progression models (PR-3 and PR-4) exhibited enrichment for cell cycle and DNA damage response programs, including G2/M checkpoint, E2F targets, and AURKA signaling (Fig. 5J). Several of these pathway alterations mirrored findings from our earlier in vitro models of palbociclib resistance (indicated with stars in Fig. 5J)29,31. Specifically, we observed upregulation of IL-6/STAT3 signaling and EMT in models derived from patients who progressed after at least 6 months of CDK4/6i treatment (Figure. S4D). Spearman correlation analysis further aligned PR-1 most closely with our in vitro palbociclib-resistant cells (Fig. 5K & Figure S3F).

To evaluate whether resistance-associated transcriptional features observed in cell lines were recapitulated in vivo, we compared global gene expression profiles of the four PDX models with T47D parental and resistant cells using Spearman correlation analysis (Fig. 5K). As expected, all models showed strong overall correlation (Spearman > 0.7) with both T47D states, reflecting their shared luminal identity and baseline similarity as HR + /HER2– tumors. However, relative differences in correlation offered meaningful insights: PR-1, derived from a patient with acquired resistance after prolonged therapy, aligned most closely with T47D-resistant cells. In contrast, PR-3—an early-progression model—was more divergent from the resistant profile, consistent with its enrichment for DNA replication and mitotic pathways. This was further supported by PAM50 analysis (Fig. 5L), which classified PR-1 and T47D-resistant cells as luminal B, reinforcing their molecular similarity. These data underscore that while global transcriptomic profiles are similar among luminal tumors, distinct pathway activation patterns—particularly those related to IL-6/STAT3 signaling—can differentiate mechanisms of resistance by clinical timing.

Immunoblotting confirmed activation of STAT3 and EMT markers (pY-STAT3, N-cadherin, vimentin) in PR-1, PR-2 and BCX94 corroborating transcriptomic findings (Fig. 5M, Figure. S5S). Conversely, PR-3 and PR-4 showed elevated Cyclin E, phosphorylated CDK2, and AURKA—hallmarks of heightened G2/M and E2F activity—supporting a non-inflammatory, proliferation-driven resistance program in early progressors.

Collectively, these data reveal biologically and clinically distinct resistance mechanisms between tumors that progressed within 3 months of CDK4/6i therapy and those that progressed after ≥6 months. Models derived from patients with ≥6-month progression (PR-1 and PR-2) exhibit inflammation- and senescence-associated signaling, particularly IL-6/STAT3 activation and EMT) In contrast, models from patients with <3-month progression (PR-3 and PR-4) display enhanced proliferative signaling. These divergent resistance states provide a rationale for distinct therapeutic strategies and support prioritization of IL-6/STAT3 pathway inhibitors in patients with acquired resistance emerging after extended CDK4/6i exposure.

Targeting pY-STAT3 enhances efficacy of palbociclib in PDX models with acquired resistance

Our previous studies demonstrated that inhibition of the IL-6/STAT3 pathway using TTI-101—a small-molecule STAT3 inhibitor currently under evaluation in phase IB/II trials for breast and hepatocellular cancers (NCT05384119, NCT05440708)—reduced cell viability in palbociclib-resistant breast cancer cells29,39,40. Building on this rationale and the mechanistic data in Figs. 3–5, we evaluate TTI-101 as monotherapy and in combination with palbociclib across four distinct palbociclib-refractory PDX models (PR-1 to PR-4). Mice were randomized into four treatment arms: (1) vehicle, (2) palbociclib (50–75 mg/kg daily, 21 days on/7 days off), (3) TTI-101 (50 mg/kg twice daily), and (4) palbociclib + TTI-101. Treatment continued until tumors in the control group reached 1000 mm³.

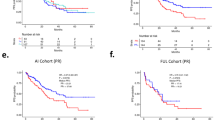

In PDX models derived from patients who progressed after ≥6 months of palbociclib therapy (PR-1 and PR-2), TTI-101 significantly inhibited tumor growth (Fig. 6A, C; Figure S5A, C). In contrast, no response was observed in PR-3 and PR-4, which were derived from patients who progressed within 3 months (Fig. 6B, D; Figure S5B, D). Combination treatment in PR-1 and PR-2 further suppressed tumor growth and extended survival relative to either monotherapy (Fig. 6E; Figure S5E). In PR-1, TTI-101 extended median survival to 35 days (vs. 9 days in controls), while the combination significantly improved survival (p = 0.001; median not reached). Similar trends were observed in PR-2 (vehicle: 17.5 days; TTI-101: 28 days; combination: 35 days). No survival benefit was observed in PR-3 or PR-4 (Fig. 6F; Figure S5F).

A, B Fold change in the tumor volume in female nude mice bearing either PR-1 (A) or PR-4 (B) after treatment with combination of palbociclib (palbo) with TTI-101, and vehicle up to 74 days (PR-1) and 52 days (PR-4). The Tukey multiple comparisons test determined p values. C, D Relative change in tumor volume at the treatment endpoint for PR-1 (C) and PR-4 (D) for each individual mouse. E, F Event-free survival analysis of PR-1 (E) and PR-4 (F) PDX models treated as described in A-B, calculated based on the days on treatment when fold change in tumor volume reached 1.5 (PR-1) or 7 (PR-4). The Mantel-Cox log-rank test determined p values. G, H Quantification (left panel) and representative images (right panel) of Ki67 immunohistochemical staining at the treatment endpoint. The Tukey multiple comparisons test determined p values. I, J White blood cell count (WBC), red blood cell count (RBC), and neutrophils measured from blood collected at the treatment endpoint. Gray area indicates normal ranges for non–tumor-bearing female nude mice. K, L Change in body weight at the indicated days over the course of treatment. M, N Level of TTI-101 accumulation (ng/g) evaluated by LC-MS/MS in tumor lysates collected 4 h after the last drug was administered at the treatment endpoint in PR-1 and PR-4. ND=not detected. O. Quantification (left panel) and representative images (right panel) of pSTAT3 (Y705) immunohistochemical staining at treatment end point with the indicated treatments. Tukey’s multiple comparisons test determined p-values. *p < 0.05. P, Q Luminex analysis of tumor lysates for pSTAT3 and STAT3 at treatment end point with the indicated treatments in PR-1 (P) and PR-4 (Q). MFI = Mean Fluorescent Intensity, *p < 0.05, tumor lysates were normalized to 1ug/uL. R Tumor human IL-21 (hIL-21) levels as measured by the ProcartaPlex Human Immune Monitoring 65-plex Luminex analysis of PR-1 and PR-4 PDX tumor lysate samples collected at the treatment endpoint. S Hierarchical clustering heat map with the z-scores of significant differentially expressed proteins with adjusted p < 0.3 between combination (Palbo+TTI-101) and vehicle from reverse-phase protein array analysis of PR-1 PDX tumor lysates collected at the treatment endpoint. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

Immunohistochemical analysis of Ki67 confirmed reduced proliferation in PR-1 and PR-2 following combination therapy (Fig. 6G; Figure S5G), consistent with tumor regression. In PR-3 and PR-4, Ki67 levels remained unchanged, corroborating treatment resistance (Fig. 6H; Figure S5H).

TTI-101 was well tolerated across all models, with no significant changes in weight or hematologic parameters (WBC, RBC, neutrophils; Fig. 6I–K; Figure S5I–K). Tumor pharmacokinetics confirmed adequate intratumoral accumulation of TTI-101 (200–1500 ng/g) in PR-1, PR-2, and PR-4 (Fig. 6M–N; Figure S5L), and co-treatment with palbociclib did not alter drug distribution. In PR-3, TTI-101 was undetectable (Fig. 6K), indicating poor drug delivery or retention.

To further evaluate the therapeutic relevance of TTI-101 in models derived from patients who progressed after ≥6 months of CDK4/6 inhibitor therapy, we compared the transcriptomic profiles of our in vitro palbociclib-resistant HR+ breast cancer cell lines29,31 with those of PDX models to identify additional cases that recapitulate this resistance signature. RNA sequencing of six PDX models revealed that the triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) PDX model BCX-094 strongly correlated with the acquired palbociclib resistance signature (Figure. S5R-S). BCX-094 displayed sensitivity to STAT3 inhibition, as evidenced by delayed tumor growth, significant TTI-101 accumulation, decreased pSTAT3 levels, and reduced plasma human IL-6 levels upon treatment with TTI-101 (Figure. S5T-Z). Human IL-6 was undetectable in plasma from PR-1–4.

To assess treatment-induced cytokine changes, we analyzed endpoint tumor lysates using a 65-plex Luminex assay. The analysis identified IL-21 as significantly downregulated in PR-1 and PR-2 after combination treatment (Fig. 6R; Figure S5M). As both a STAT3 activator and transcriptional target, IL-21 may form an autocrine loop similar to IL-641. In PR-1, which showed the strongest response, reverse-phase protein array analysis further revealed suppression of STAT3 targets CD44 and HIF-1α at the protein level following combination treatment (Fig. 6S).

To confirm direct STAT3 inhibition within tumor cells, we conducted IHC for phosphorylated STAT3 (Y705) on FFPE tumor sections from PDX models treated with vehicle, palbociclib, TTI-101, or the combination. In the TTI-101–responsive BCX-094 model, high baseline pSTAT3 was observed in tumor epithelial cells, which was markedly reduced following TTI-101 treatment (Figure. S5X), confirming in vivo target engagement. In contrast, PR-4, which showed no response to TTI-101, exhibited low baseline pSTAT3 (<5%) that did not change across treatment arms (Fig. 6O). These data indicate that STAT3 pathway activation in tumor cells—not stromal elements—is required for therapeutic efficacy and that baseline pSTAT3 may serve as a predictive biomarker.

To further validate on-target STAT3 inhibition, we integrated complementary analyses using Luminex and Western blotting. Luminex profiling of tumor lysates from PR-1 demonstrated reduced pSTAT3 (Y705) following TTI-101 treatment (Fig. 6P), whereas PR-4 maintained low, unchanged pSTAT3 levels (Fig. 6Q), consistent with the IHC findings. Figure. S5L shows a similar pattern: pSTAT3 levels declined in the responsive PR-2 model but remained stable in non-responsive PR-3 tumors. Western blots of BCX-094 tumors confirmed pSTAT3 suppression without altering total STAT3 (Figure. S5V–W). Together, IHC, Luminex, and immunoblotting provide converging evidence of robust on-target STAT3 inhibition by TTI-101.

In addition to effects on proliferation, we explored the role of IL-6/STAT3 in metastasis. Prior work demonstrated that palbociclib-resistant cells with elevated IL-6/pSTAT3 exhibited EMT-like features and increased metastatic potential. Specifically, in Kettner et al.29, we showed that intravenous injection of resistant MCF7 cells led to significantly increased lung colonization compared to parental controls, consistent with EMT-driven dissemination.

Lastly, we directly tested IL-6 as a therapeutic target in vivo. PR-2 tumor-bearing mice were treated with the IL-6 receptor–blocking antibody tocilizumab. Anti-IL-6R significantly slowed tumor growth, reduced endpoint tumor volumes (p = 0.01), and prolonged event-free survival (p = 0.039; Figures. S5N–P). IHC analysis revealed decreased Ki67 in anti-IL-6R–treated tumors (Figure. S5Q), confirming suppressed proliferation. These findings provide direct evidence that pharmacologic inhibition of IL-6 alone is sufficient to suppress tumor growth, reduce proliferation, and delay progression in a CDK4/6i-resistant model.

In summary, these data establish the IL-6/STAT3 axis as a viable and druggable target in HR + /HER2− metastatic breast cancers progressing after ≥6 months of CDK4/6i therapy. The observed therapeutic efficacy, favorable safety profile, and correlation with pSTAT3 and IL-6 biomarkers support integrating IL-6/STAT3 inhibition into treatment strategies for CDK4/6i-resistant disease.

Discussion

This study delineates mechanisms of resistance to CDK4/6 inhibitors (CDK4/6i) in HR + /HER2- metastatic breast cancer, with a focus on the IL-6/STAT3 axis as a key driver of resistance. By analyzing PDX models from tumors that progressed early ( < 3 months) versus late ( ≥ 6 months) during CDK4/6i therapy, we identified distinct transcriptomic programs underlying resistance. Early-progressing tumors exhibited enrichment of cell cycle and DNA damage response pathways, whereas late-progressing tumors showed upregulation of inflammatory, cytokine, and immune-modulatory signatures, reflecting mechanistic heterogeneity in resistance evolution.

Functional studies revealed that IL-6 is not merely a byproduct of resistance but actively sustains it. Silencing IL-6 in resistant cells restored sensitivity to CDK4/6i, reinforcing its role as a mechanistic contributor. In patient samples, elevated plasma IL-6 at progression correlated with poorer outcomes and was more consistently associated with resistance than mutational profiles, which were highly heterogeneous and lacked predictive value. These findings support the potential of IL-6 as a dynamic biomarker of acquired resistance.

IL-6 is a pleiotropic cytokine that plays essential roles in inflammation, immune responses, and cellular senescence—a stress-induced, stable cell cycle arrest42. As a key component of the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP), IL-6 is secreted alongside other cytokines, chemokines, and proteases, modulating both autocrine and paracrine signaling43,44,45. Initially tumor-suppressive, chronic SASP activity fosters an inflammatory microenvironment conducive to cancer progression. Prolonged IL-6 signaling can promote angiogenesis, suppress apoptosis, evade immune surveillance, and facilitate EMT, ultimately driving metastasis42,46.

Our previous work29 demonstrated that palbociclib-resistant ER+ breast cancer cells exhibit elevated IL-6 and phosphorylated STAT3, features accompanied by EMT induction, loss of ERα, acquisition of stem-like traits, and increased invasiveness. Treating sensitive parental cells with exogenous IL-6 recapitulated these changes, highlighting its causal role in driving phenotypic shifts linked to resistance.

Interestingly, IL-6 knockdown restored responsiveness to fulvestrant and palbociclib in MCF7-resistant cells, despite near-complete loss of ERα and RB expression. This suggests alternative mechanisms of drug sensitivity. Fulvestrant may retain activity through ER-independent pathways, such as activation of the G protein–coupled estrogen receptor (GPER), which can mediate apoptosis even in the absence of classical ERα signaling47,48,49. In addition, residual or truncated ER isoforms not detectable by immunoblotting may persist and confer some hormonal vulnerability. Regarding palbociclib, CDK2-cyclin E activity provides a known bypass route in RB-deficient cells50,51,52. Our data show that IL-6 knockdown reduces cyclin E levels, which may impair CDK2 function and thus restore sensitivity to CDK4/6i. These observations suggest that IL-6 sustains resistance by maintaining multiple bypass circuits and that its inhibition indirectly reactivates drug sensitivity through non-canonical mechanisms.

In addition to IL-6, analysis of patient serum at the time of progression revealed significant elevations in the chemokines CXCL10, CCL2, and CCL8, all of which correlated strongly with IL-6 levels (Fig. 1H, Figure. S1C). While these chemokines are best known for their canonical roles in immune cell recruitment—particularly T cells (CXCL10), monocytes (CCL2), and diverse leukocyte subsets (CCL8)—their function can become reprogrammed in the context of chronic inflammation and sustained IL-6/STAT3 signaling. Under these conditions, chemokines may contribute to immune evasion, tumor progression, or metastatic dissemination rather than immune activation. Indeed, CCL2 and CCL8 have been shown to facilitate the formation of pre-metastatic niches and promote metastatic seeding in both breast and pancreatic cancers34,53,54 while CXCL10, although generally associated with T cell trafficking and anti-tumor immunity, has paradoxically been linked to tumor cell survival, proliferation, and metastasis in certain inflammatory and tumorigenic contexts55,56. These context-dependent, tumor-promoting effects—although not reflective of their primary biological function—highlight the plasticity of chemokine activity within an inflamed tumor microenvironment. In our study, the functional relevance of this chemokine reprogramming is further supported by the observed reduction in lung metastases29 following STAT3 knockdown in resistant cells, underscoring a model in which IL-6/STAT3-driven inflammation reshapes chemokine networks to support metastatic progression.

Targeting this axis represents a compelling therapeutic strategy. Clinical-grade agents that block IL-6, IL-6R, or JAK-STAT signaling—including siltuximab, tocilizumab, and ruxolitinib—have been evaluated in inflammatory and oncologic settings57. More recently, selective STAT3 inhibitors such as TTI-101, which targets the STAT3 SH2 domain essential for its activation, dimerization and function, have shown promising preclinical efficacy in various cancers, including ER+ breast cancers resistant to CDK4/6i28,29,58,59,60. In our study, TTI-101 suppressed tumor growth in CDK4/6i-resistant PDXs with IL-6/STAT3 activation, underscoring its translational relevance.

Importantly, not all patients exhibited elevated IL-6 at progression. Longitudinal analysis revealed that IL-6 increased progressively over time in a subset of patients, culminating in peak levels at radiographic progression. This temporal association supports the use of IL-6 as a dynamic biomarker of emergent resistance, rather than a static predictor. Its role may be particularly relevant in patients whose tumors acquire inflammatory features over time, distinguishing them from those with resistance driven by cell cycle deregulation or other mechanisms.

Several limitations should be noted. Although our cohort of 166 patients is among the largest to examine circulating IL-6 in this context, validation in independent prospective datasets is essential. Mechanistic insights were primarily derived from ER+ cell lines and PDX models, which do not fully encompass the diversity of resistance phenotypes observed in the clinic. Our PDXs, while informative, represent a limited sample set and would benefit from deeper stratification by prior ET and mutational profiles. Furthermore, although TTI-101 demonstrated robust activity in selected models, additional agents targeting this pathway should be evaluated to confirm generalizability and on-target effects.

While genomic profiling offers valuable insights, our data emphasize that mutation-based strategies alone may be insufficient to capture the complexity of acquired resistance. In contrast, IL-6 emerges as a biologically relevant, actionable, and temporally responsive biomarker. Its integration into clinical workflows could enable early detection of resistance and guide implementation of targeted therapies, such as STAT3 inhibitors, to improve outcomes for patients with advanced HR + /HER2- breast cancer.

Methods

Patient sample collection

Blood and breast tumor biopsy samples were collected from patients with ER + /HER2- metastatic breast cancer treated at MD Anderson under the Institutional Review Board–approved protocol (PA19-00047) and in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants provided written informed consent. Eligible patients included those aged 18 years or older, diagnosed with HR+ (ER or progesterone receptor ≥1% staining in primary or recurrent tumors) breast cancer between January 1, 1997, and December 31, 2023 and either screened for metastatic breast cancer or suspected but not yet diagnosed. Blood samples were obtained from patients before initiating CDK4/6i therapy, every 2–3 months during treatment, and again at the time of disease progression. Clinical data, including serum CA15-3 ELISA values, were sourced from electronic medical records (OneConnect and Care Everywhere) and a prospectively maintained Breast Cancer Management System, managed by the Breast Medical Oncology Department at MD Anderson. Human plasma was isolated from EDTA-treated tubes from each sample and subjected to IL-6 ELISA or Luminex Assay.

A total of 11 patients had matched pre-treatment and progression serum samples available for analysis. Differences in sample numbers across Fig. 1C, E, I reflect clinical variability and logistical sequencing of assays rather than selective inclusion or exclusion. Specifically, ELISA-based IL-6 measurements (Fig. 1C) were performed on all 11 matched pairs. CA15-3 levels (Fig. 1E) were available in only 6 of the 11 patients due to inconsistent clinical ordering practices, as these values were extracted retrospectively from medical records. Luminex multiplex cytokine profiling (Fig. 1I) was conducted on 8 matched samples processed earlier in the study; the remaining 3 matched samples became available after this analysis had been completed. No samples were excluded for analytical reasons, and all assays used all available matched samples at the time of analysis.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) of patient samples

IHC was performed on paraffin-embedded, formalin-fixed human tumor tissue sections in our clinical immunohistochemistry laboratory, which is certified under the provisions of the United States Clinical Laboratory Improvement Act and accredited by the College of American Pathologists. The protocol has been validated for use on 4-µm paraffin-embedded, formalin-fixed tissue sections. This protocol includes de-paraffinization (30 min at 72 °C) and rehydration with antigen retrieval performed at 100 °C for 30 min with citrate buffer, pH 6.0. Endogenous peroxidase was blocked with 3% peroxide for 5 min before incubation with the primary antibody, pY-STAT3 (clone Tyr705, Cell Signaling; 1:100 dilution). Post-primary antibody detection was carried out using a commercial polymer system (Bond Polymer Refine Detection, Leica), and stain development was achieved by incubation with DAB and DAB Enhancer (Leica). A positive batch control was added to every immunohistochemistry run and on-control to each slide. Evaluation of ER was interpreted as positive for any nuclear staining ≥1% of tumor cells. For pY-STAT3, percentage positivity of nuclear staining was evaluated.

IL-6 ELISA

The Quantikine Human IL-6 ELISA kit (R&D Systems) was used to measure IL-6 in cell culture supernatants and human plasma isolated from EDTA-treated tubes following the manufacturer’s protocol. Cell culture supernatant IL-6 levels were normalized based on number of cells.

Luminex assay

PDX tumor tissues were dissected and cut into smaller pieces. Dissected tissues were snap-frozen immediately and stored at -80 °C. For tissue lysate preparation, T-PER Tissue Protein Extraction Buffer Reagent (Thermo Fisher, Cat. No. 78510) was added into the frozen tissue in cryovial directly and homogenized by TissueLyser II (Qiagen, Cat. No. 85300). Tissue and cell debris were removed by 10 min of centrifugation at 18 × g at 4 °C. Protein concentrations were measured using the Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher, Cat No. 23227) and read on a Synergy LX multi-mode plate reader (BioTek, Cat No. BTSLXFA). Total proteins were normalized to 1 mg/mL in T-PER buffer and stored at -80 °C until the cytokine levels were measured by the Luminex analysis.

APRIL, BAFF, BLC, CD30, CD40L, ENA-78, Eotaxin, Eotaxin-2, Eotaxin-3, FGF-2, Fractalkine, G-CSF, GM-CSF, GRO-α, HGF, IFN-α, IFN-γ, IL-10, IL-12p70, IL-13, IL-15, IL-16, IL-17A, IL-18, IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-2, IL-20, IL-21, IL-22, IL-23, IL-27, IL-2R, IL-3, IL-31, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-7, IL-8, IL-9, IP-10, I-TAC, LIF, MCP-1, MCP-2, MCP-3, M-CSF, MDC, MIF, MIG, MIP-1α, MIP-1β, MIP-3α, MMP-1, NGFβ, SCF, SDF-1α, TNF-β, TNF-α, TNF-R2, TRAIL, TSLP, TWEAK, and VEGF-A concentrations from human plasma isolated from EDTA-treated tubes and normalized PDX tumor lysates were assayed using the ProcartaPlex Human Immune Monitoring 65-plex Panel (Thermo Fisher Scientific Cat. No. EPX650-10065-901) at the ORION Core at MD Anderson. Human plasma samples were assessed in triplicate and normalized. PDX tumor lysate samples were assessed in duplicate according to the manufacturer’s guidelines and measured using the Luminex 200. Acquisition was performed using the xPONENT version 4.2 software and analysis was performed using the Bio-Plex Manager version 6.1 software.

pSTAT3 Luminex Assay was performed as previously described61. Briefly, total protein was plated in a 96 well filter plate pre-loaded with beads (Millipore, Danvers, MA) coupled to antibody against the indicated analytes. Bead-bound analytes were measured using biotinylated detection antibody specific for a different epitope and streptavidin-phycoerythrin (streptavidin-PE) 58, 59. Data were collected and analyzed using the Bio-Plex suspension array system (Luminex 100 system, Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA).

Genomic testing on patient samples

Tumor next-generation sequencing was either performed on tumor tissue, using one of five CLIA (Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendment) platforms with a range of 50–400 cancer-related genes assessed, or circulating tumor DNA, using Guardant360. Genomic testing results were retrieved from a prospectively maintained database. This data are accessible through a protocol that is approved by the Institutional Review Board, with a waiver of informed consent62,63,64,65. Genomic alterations presented represent alterations that were determined to be of somatic origin by the clinical laboratory performing the testing. The germline variants were excluded based on matched tumor-normal analysis in some laboratories and by using database-driven computation approaches in others. Both publicly available and locally curated knowledgebases were used to determine clinical actionability of somatic variants using laboratory-specific practices.

Cell lines and culture conditions

All cell lines used in the present study were obtained from American Type Culture Collection. MCF7 and T47D were maintained in minimum essential medium Eagle alpha modification (alpha MEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 10 mM HEPES, nonessential amino acids, sodium pyruvate, 2mM L-glutamine, insulin, EGF, and hydrocortisone. 293 T cells were cultured in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. Palbociclib-resistant cell lines were generated as previously described29. All cells were free of mycoplasma contamination and were authenticated regularly (every 6 months) by karyotype and short-term repeat analysis at the MD Anderson Characterized Cell Line Core Facility.

shRNA knockdown of IL-6

Stable shRNA knockdown cells were generated using the following Dharmacon pGIPZ-shRNA for IL-6: V3LHS_390095 (shIL-6 #1) and V2LHS_111640 (shIL-6 #2) purchased from the shRNA and ORFeome core facility at MD Anderson. For generating lentivirus-expressing shRNA, HEK 293 T cells were transfected with pCMVdeltaR8.2, pMD2.G (produced by the Didier Trono laboratory and made available through the Addgene repository), and pGIPZ vector (scrambled shRNA or shRNA against gene of interest) using polyethylenimine transfection reagent according to the manufacturer’s protocol. After 48 h of transfection, the virus-containing medium was collected, filtered through a 0.45-μm filter, and added to the cells of interest in the presence of 8 μg/mL polybrene (Millipore). GFP expression was confirmed by microscopy, and the lentivirus-infected cells were sorted for GFP-high population.

Cell proliferation assays

For determining doubling time, cells were plated in 6-well plates at different seeding concentrations for each time point collection over 21 days. The seeding values below are based on previous doubling time data in which the cells would reach about 1.5 × 106 cells at each time point collection:

At each time point, the cell culture supernatants (media) were collected and stored at -20 °C, and then the cells were harvested. The number of cells was determined using the BioRad TC20 Automated Cell Counter. Doubling time was calculated using the formula doubling time = ([t2 – t1] × log10 2)/(log10 q2 – log10 q1), where t is time and q is the cell growth at each specific time point, q1 at time t1 and q2 at time t2.

High-throughput dose response survival assay

Cells were seeded at a density of 1000 cells/well in a 96-well plate and treated with palbociclib and TTI-101 (kindly provided by Drs Tweardy and Tvardi) at the indicated concentrations. Palbociclib was administered for 6 consecutive days and TTI-101 for 72 h. At completion of drug treatment, cultures were continued in drug-free medium (also replaced every other day) until day 12. For treatment with the anti-estrogen, fulvestrant (Sigma), cells were seeded at a density of 3000 cells/well in a 96-well plate and cultured in estrogen-free media, which is composed of phenol red-free improved minimum essential medium supplemented with 10% charcoal/dextran-treated fetal bovine serum for 24 h. Cells were then treated with 10 nM beta-estradiol (E2) and 0.1-12 µM fulvestrant for 48 h. For assessment of cell viability at the end of treatment, plates were stained with 0.5% crystal violet solution and solubilized with a solution of 0.1% sodium citrate in 50% ethanol. Absorbance was measured at 570 nm using the Epoch Microplate Spectrophotometer (BioTek Instruments, Inc, Winooski, VT). Values were normalized to those of their no-treatment controls and analyzed in GraphPad Prism by nonlinear regression to obtain the half-maximal inhibitory concentrations.

Senescence analysis

Senescence was measured using the senescence β-galactosidase staining kit (#9860; Cell Signaling Technology) following the manufacture’s protocol. For quantification, the cells were imaged using the Evos XL Core cell imaging system, and β-galactosidase–positive cells were quantified by counting ~100 total cells in three different fields.

Western blot analysis

Protein expression was analyzed by Western blot using whole cell or tumor lysates lysed in RIPA buffer and the following antibodies: ERα (clone 6F11; Vector Laboratories VP-E613), progesterone receptor (clone 1E2, Ventana), HER2 (Millipore #OP15), Cyclin E (HE12; Santa Cruz Biotechnology sc-247), Rb (4H1; Cell Signaling Technology #9309), phospho-Rb (Ser807/811; Cell Signaling Technology #9308), CDK6 (C-21; Santa Cruz Biotechnology sc-177), E-cadherin (24E10; Cell Signaling Technology #3195), N-cadherin (Cell Signaling Technology #4061), Vimentin (R28; Cell Signaling Technology #3932), STAT3 (D3Z2G; Cell Signaling Technology #12640), phospho-STAT3 (Tyr705; Cell Signaling Technology #9145), Cyclin D1 (H-295; Santa Cruz Biotechnology sc-753), CDK2 (D-12; Santa Cruz Biotechnology sc-6248), phospho-CDK2 (Thr160; Cell Signaling Technology #2561), Aurora Kinase A (1G4; Cell Signaling Technology #4718), p27 (C-19; Santa Cruz sc-528), Vinculin (Sigma-Aldrich V9131), and β-actin (C4; Millipore MAB1501) following standard procedures.

Quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated from cell cultures with TRIzol reagent according to the manufacture’s protocol (Invitrogen). Two micrograms of the RNA samples were reverse-transcribed using a cDNA Synthesis Kit (Applied Biosystems). RT-PCR was done with aliquots of cDNA samples mixed with SYBR Green Master Mix (Sigma). Reactions were carried out in triplicate. The fold difference in transcripts was calculated using the ΔΔCt method with GAPDH as a control. The following primers were used:

IL-6: forward 5’GATGGCTGAAAAAGATGGATGC-3’, reverse 5’TGGTTGGGTCAGGGGTGGTT-3’

STAT3: forward 5’AAAGCAGCAAAGAAGGAGGC-3’, reverse 5’CTGGCCGACAATACTTTCCG-3’

ESR1: forward 5’TGAAAGTGGGATACGAAAAGAC-3’, reverse 5’CAGGATCTCTAGCCAGGCACAT-3’

PgR: forward 5’ACCCGCCCTATCTCAACTACC-3’, reverse 5’AGGACACCATAATGACAGCCT-3’

N-cadherin: forward 5’ACAGTGGCCACCTACAAGG-3’, reverse 5’CCGAGATGGGGTTGATAATG-3’

Vimentin: forward 5’GAGAACTTTGCCGTTGAAGC-3’, reverse 5’GCTTCCTGTAGGCAATC-3’

CD44: forward 5’CGGACACCATGGACAAGTTT-3’, reverse 5’GAAAGCCTTGCAGAGGTCAG-3’

ALDH1: forward 5’CTGTGTTCCAGGAGCCGAAT-3’, reverse 5’AGCATCCATAGTACGCCACG-3’

RNA sequencing and gene set enrichment analysis

Total RNA was isolated from PDX tumor tissue with TRIzol reagent according to the manufacture’s protocol (Invitrogen). RNA samples were submitted to Novogene Corporation, Inc. Total RNA samples were purified using poly-T oligo-attached magnetic beads. After fragmentation, the first-strand cDNA was synthesized using random hexamer primers, and then the second-strand cDNA was synthesized dTTP for nondirectional library. The library was checked with Qubit and real-time PCR for quantification and bioanalyzer for size distribution detection. Quantified libraries were pooled and sequenced on Illumina platforms, according to effective library concentration and data amount. The clustering of the index-coded samples was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After cluster generation, the library preparations were sequenced on an Illumina platform, and paired-end reads were generated. FASTQ sequence files were checked for read quality using FastQC 0.11.8 and then aligned to the combined reference genome (GENCODE human GRCh38 and mouse GRCm38 concatenated) using tophat2 2.1.1. FeatureCounts (Subread 1.6.3) was used to count reads that are mapped to each feature66,67. Features were annotated using the combined gene transfer format (GTF) file from GENCODE human and mouse reference. The human gene count matrix was retrieved for downstream analysis. The read count data was normalized using the trimmed mean of M (TMM) method implemented in the Bioconductor package edgeR (3). The limma package with its voom method, linear modeling and empirical Bayes moderation was applied for differential gene expression analysis68. The group of interest was treated as a fixed effect, while the sample batch variable was treated as a random effect. Benjamini-Hochberg (BH) correction was applied to the p-values for multiple testing. Functional analysis of the differentially expressed gene sets or pathways was performed using gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA)69,70. The Hallmarks and KEGG gene sets from the Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDB) were analyzed.

PAM50 analysis

The cell line RNA-seq data was processed similarly to the PDX tumor RNA-seq data except that only human GRCh38 was used for cell line data alignment and feature annotation. Again, the read count data for the cell line RNA-seq samples were normalized using the and then transformed to log2 counts per million values71. The average gene expression was calculated for each cell. We then used the R package genefu72 to identify tumor subtype for each cell. The pam50 analysis in the genefu package involves robust standardization of gene expression (re-scales the expression values based on quantiles, and therefore robust to outliers), using centroid data, calculating Spearman rank correlation between each sample and each subtype centroid, and assigning the class of the most highly correlated centroid to each sample. Consistently, we repeated the same steps described above on the PDX RNA sequencing data. Next, we obtained standardized gene expression values from each data set and combined them for generating a heatmap based on the pam50 gene signature. Spearman distance and the Ward method were applied for gene/sample clustering on the heatmaps.

Expansion and treatment of PDX models

All animal studies were approved by The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

PDX models PR-1, PR-2, and PR-3, originally named CTG-3277, CTG-3266, and CTG-2308, respectively, were obtained from Champions Oncology, Inc., through a Material Transfer Agreement with MD Anderson. PDX model PR-4 (originally named T141-004) and BCX-094 were kindly provided by Dr Funda Meric-Bernstam at MD Anderson and were generated as previously described73,74. PDX models were re-established from passage 2 (P2) liquid nitrogen tumor stocks and transplanted into the fourth (T4) mammary fat pad of 8-week-old anesthetized (2.5-4% isoflurane) female NSG mice given drinking water supplemented with 8 µg/mL estradiol, except for PR-4, which was not grown in the presence of estradiol. Tumors were allowed to reach a tumor volume of 1000-1500 mm3 and then harvested and used for further PDX expansion to establish each PDX model to at least passage 3 (P3) prior to use for drug treatment experiments.

For each PDX model, 30- to 50-mm3 tumor fragments from P3 were transplanted into the T4 mammary fat pad of 8-week-old anesthetized (2.5-4% isoflurane) female nude mice. Tumors were allowed to grow until they reached 150–200 mm3 in the presence of drinking water supplemented with estradiol (8 µg/mL), except for PR-4 and BCX-094. Mice were randomly allocated to the indicated treatment arms and orally dosed with vehicle (daily), palbociclib (50–75 mg/kg daily for 21 days, 7 days off), TTI-101 (50 mg/kg twice daily by oral gavage), or the combination of palbociclib+TTI-101 (kindly provided by Tvardi Therapeutics, Inc.). Once treatments were started, the estradiol supplementation was removed, mimicking the effect of ET. The length and width of tumor xenografts were measured by caliper 2 to 3 times per week, and tumor volume was calculated by the formula volume = (length × width2)/2. The mice were euthanized when average tumor volume in the vehicle-treatment arm reached 1000-1300 mm3. Euthanasia was carried out using an euthanex system for delivery of C02 followed by cervical dislocation. Following euthanasia, all tumors were harvested, random fragments were frozen and stored at -80 °C for RNA/protein isolation, and one random piece was fixed in formalin for histopathologic and immunohistochemistry analysis. Palbociclib isethionate (MedChemExpress) was diluted in 0.5 W/V% methyl cellulose 400 (FUJIFILM Wako Chemicals), TTI-101 was diluted in 60:40 Labrasol:PEG400 with brief sonication for about 2 min, and vehicle was a 50:50 mixture of 0.5 W/V% methyl cellulose 400 and 60:40 Labrasol:PEG400.

Drug toxicity analysis

Complete blood cell count analysis was performed after completion of treatment for patient-derived xenograft (PDX) models PR-1, PR-2, and PR-4. Blood was collected via cardiac puncture through the left ventricle at the time of euthanasia and 0.25-0.5 mL was placed into EDTA-treated collection tubes. Blood cell counts were measured on the Siemens Adiva 120 Hematology System (Erlangen, Germany) in the Department of Veterinary Medicine and Surgery and Department of Pathology at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center. Change in body weight was determined in all PDX models by subtracting the body weight at the indicated days during treatment from the starting body weight just prior to the first day of treatment

Pharmacokinetic analysis of TTI-101

Tissue lysis media was prepared by mixing stabilizer containing 20 mg/mL NaF, 25 mg/mL Na2SO3, and 25 mg/mL L-ascorbic acid in diH2O with 1× phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at a 1:1 ratio. Tumor tissues were excised, weighed, and transferred into Rino bead lysis kits (Next Advance gold, Averill Park, USA). Then, 20 µL of lysis media (1:1 PBS/stabilizer mix)/1 mg of tissue was added to each sample. The samples were then homogenized in a Bullet Blender (Next Advance gold, Averill Park, USA) for 5 min.

Aliquots of 100 µL of the homogenized PDX sample tissues were spiked with 5 µL of deuterated TTI-101(D7) as the internal standard to a final concentration of 5 µM. Calibration standards and quality control samples of TTI-101 were prepared by spiking 5 μL of the working solutions of TTI-101 and internal standard into 100 μL of blank tissue homogenates. The mixtures were mixed thoroughly and placed on ice.

TTI-101 and internal standards were extracted by addition of 600 μL of methyl tert-butyl ether followed by 1 min of vortex-mixing. The mixture was centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 5 min. The extracted top layer was transferred to another disposable glass tube and evaporated to complete dryness in a water bath at 40 °C under a stream of nitrogen. The dried sample was reconstituted with 100 μL of methanol followed by vortex-mixing for 1 min and sonication for 5 min. The reconstituted sample was spun down and transferred to a liquid chromatography vial prior to liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) analysis.