Abstract

A whole pathology section contains approximately 1,000,000 cells of various types, this large-scale heterogeneity of cells and non-cellular constituents constructs a mutually competitive community. Conventional pixel-based visual processing techniques are insufficient to accurately capture the complexities inherent with cell-entity deployment and formation strategy. Here, we conquered segmentation and classification of all cells on the whole pathology sections from 387 hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) patients across six cohorts with 57 pathologists assisted. Further, an AI system called Hybrid Graph Neural Network-Transformer system (HGTs) was proposed. It precisely predicted local recurrence of postoperative HCC by analyzing cell interactions across multiple scales, from cell-to-cell, cell-community, to tissue-level interactions. The proposed HGTs outperformed existing SOTA methods, with the C-index improving by 23.1% to reach 0.823, by further integrating multimodal data, including clinical information and immunohistochemical markers. A set of spatial relational biomarkers influencing tumor prognosis was discovered and quantitatively validated. They include the frequency of tumor-lymphocyte and tumor-tumor interactions, the distribution and sparsity of key cellular communities, and the degree of fibrosis in adjacent peritumoral tissues. Utilizing the anti-tumor potential of this marker set, we’re developing therapies to enhance the immune system’s fight against cancer. All cell semantic segmentation datasets and code are publicly available: https://github.com/Yuan1z0825/HGTs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Delving into the tumor microenvironment (TME) can yield significant prognostic information in cancer studies. The TME, a complicated ecosystem, integrates a plethora of cellular and non-cellular constituents including cancer cells, immune cells, stromal cells, the extracellular matrix, and signaling molecules1. This assemblage collaboratively orchestrates tumor development, invasion, metastasis, and treatment responses1. Despite recent breakthroughs illuminating certain interaction mechanisms within the TME, such as intratumor tertiary lymphoid structures2, vessels encapsulating tumor clusters3,4, and tumor immune barrier structures5, the intricate configurations of the TME and their ramifications on the efficacy of immunotherapies and chemoradiation remain largely elusive. Specifically, regarding HCC, the TME presents itself to be exceptionally complex, accommodating a wide range of cellular elements which constitute various functional units or cellular neighborhoods6. This provides motivation delve deeper into the subtle heterogeneity and spatial distribution of cells within the TME, to better understand the mechanisms of their interactions.

With the advancement of scanning technologies and the popularity of whole-slide images (WSIs), digital pathology has become a crucial field, providing computer-assisted diagnosis7 that delves into the intricacies of the TME. For WSI, a straightforward analysis can be conducted by having pathologists visually assess the proportion and morphological distribution of various cells. Subtle histological features that may strongly correlate with patient prognosis can be overlooked when relying solely on visual examination of pathologists. Alternatively, deep learning can be utilized by treating the pathological slides as images8,9, segmenting them into multiple small patches, and using pixel-based visual methods for analysis10,11,12,13,14. Nevertheless, the spatial relationships between cells also play a crucial role. A WSI is a hyper-scale community network composed of millions of specific multi-class cell entities. Quantitatively exploring these spatial relationships is of significant importance in understanding factors that influence cancer prognosis, but the researches in this area are still scarce. Based on cells as the fundamental unit, key attributes of these community networks—such as homophily, collective behavior, community cohesion, centrality, clustering coefficient, assortativity, and interconnectedness—can be characterized through cell-level (Ego) networks, group-level community networks, community metric networks, clique networks, intergroup networks, coalitional networks, and collective intelligence networks15,16,17,18,19,20. Furthermore, developing targeted Graph neural network (GNN) and Transformer architectures can enable cancer subtyping and prognosis prediction based on WSI. The Transformer uses self-attention mechanisms to model connections in a graph-like manner.

To emphasize biological entities, cell graphs have been employed, in which cells and their interactions are depicted as nodes and edges, respectively21. Classical graph learning techniques, such as GNNs, have been used to decipher the structure-function relationship through cell graphs22. For instance, the Cell Graph Convolutional Network (CGC-Net) introduced by Zhou et al. 23 offers an innovative approach for classifying colorectal cancer histology images. This entity-based method aims to capture detailed cell-level information, outperforming traditional patch-based analysis. Nevertheless, relying on cell sampling in CGC-Net could oversimplify the rich biological complexity inherent in local tissues. Furthermore, the study by Wu Z et al. 24 demonstrates the utility of GNNs in capturing unique cellular interactions using spatial protein profiles. Despite its success, this method only considers cell type as node features, potentially neglecting the heterogeneity present within the same cells. A shared limitation across these cell graph methods is the insufficient incorporation of contextual information from the wider tissue architecture, which is essential for a comprehensive histopathological representation. To overcome these limitations, recent methodologies25,26 have introduced a hierarchical tissue model that navigates from the cellular level to the tissue landscape, providing a detailed and integrative perspective. However, these methods do not adequately consider the diverse cell types within the WSI. This oversight is crucial because the strong heterogeneity among different cell types is essential for understanding their roles in the TME. Addressing this gap could significantly enhance the accuracy of tumor prognosis prediction and promote the discovery of spatial relational biomarkers.

To make deep-learning-based pathology models clinically useful, they ought to be interpretable. As a result, researchers are actively exploring interpretable GNN methods to enhance model transparency at the cell-graph level27,28. These strategies facilitate the construction of interpretable features that are understandable to pathologists. Recent studies on the interpretability of attention distributions have introduced concepts of faithful and plausible explanations for model predictions. Attention distributions are ‘faithful’ when higher weights directly influence predictions and ‘plausible’ when they provide an understandable rationale for those predictions29,30. Therefore, it is possible to utilize attention mechanisms to quantify and interpret the distinct roles of different cell types during cellular interactions, providing pathologists with intuitive, interpretable features that incorporate context from the WSI. Such an approach would allow for multi-level discovery of prognostic biomarkers, marking a significant advance in the field of computational pathology.

To address these challenges, we focus on cell interactions within the TME across multiple scales, from cell-to-cell, cell-community, to tissue-level interactions. To this end, our study involves detailed full-cell segmentation and classification of each WSI by professional pathologists. Over the course of two years, the world’s first large-scale dataset has been developed by our groups, consisting of 387 annotated WSIs, capable of both multi-class full-cell segmentation and classification. The WSIs were categorized into seven prevalent cell types: tumor cells, vascular endothelial cells, lymphocytes, fibroblasts, biliary epithelial cells, and hepatocytes with any remaining cell types grouped together as ‘other’. This dataset will be made publicly available alongside this project. Furthermore, an AI system called the Hybrid Graph Neural Network-Transformer system (HGTs) was proposed to acquire comprehensive insights into the interactions both intra- and inter-cellularly communities. HGTs seamlessly integrates a GNN, a gated attention module, and a Transformer encoder into an end-to-end system. Specifically, in the first stage of HGTs, traditional GNNs are enhanced by introducing a heterogeneous message-passing function31. Each cell is assigned a type-specific message-passing function represented by identity matrices, enriching the category information beyond simple categorical values. This approach allows for a richer representation of cell-specific information and interactions. It enables cells within the cell community to recognize their identities, interact with distant cells, and better represent their behaviors and interactions within the TME. The gated attention module quantifies the attention scores of cells in prognosis prediction, offering a nuanced assessment of their impact on patient outcomes and enhancing interpretability. In the second stage, inspired by Vision Transformer32,33,34,35 (ViT), we incorporated the Transformer encoder into a weakly supervised MIL framework to integrate the interactions between cellular communities. This integration leverages self-attention mechanisms32,33,34,35,36 by treating local cell-constructed graphs as tokens and effectively captures complex inter-community relationships in WSIs.

In the prognosis prediction for HCC across six cohorts, the proposed HGTs, which integrated clinical information, the risk score’s C-index yielded 0.823. This represents a significant enhancement of 23.1% when compared to these state-of-the-art models: DeepGraphSurv37, PatchGCN38, and TEA-graph39. In predicting local recurrence of HCC at 1, 3, and 5 years, the proposed system shows enhanced sensitivity to the more challenging 1-year recurrence, achieving an AUC of 0.817. Ultimately, a typical marker set of spatial relationships that influence local recurrence of HCC was identified at multiple scales, including the frequency of tumor-lymphocyte and tumor-tumor interactions, the distribution and sparsity of key cellular communities, immune infiltration, and the degree of fibrosis in adjacent peritumoral tissues, etc. By leveraging the natural anti-tumor activity of this marker set, we are working to develop effective cancer treatments that boost the immune system’s ability to fight cancer.

Our work makes four key contributions:

The world’s first large-scale dataset of 387 annotated WSIs featuring multi-class full-cell segmentation and classification is presented. This dataset covers seven prevalent tumor microenvironment cell types and will be released publicly.

A multi-scale AI model (HGTs) is proposed to enable cross-scale modeling from single-cell, cell-community to tissue level with interpretable cell-interaction analysis by integrating graph neural networks with Transformer.

A C-index of 0.823 in predicting HCC prognosis is achieved by the HGTs model, which is 23.1% higher than the state-of-the-art vision-based method.

Multi-scale biomarkers associated with HCC recurrence are identified by the approach, and these findings could both improve prognosis and provide potential therapeutic targets for enhancing anti-tumor immunity.

Results

Collection and preprocessing of the patient cohorts

In this study, multidimensional data, including age, gender, and the degree of tumor cell differentiation, were collected from 337 hepatocellular carcinoma patients who underwent surgical treatment across five clinical institutions. Survival follow-up data were obtained, spanning from December 2012 to October 2017. The dataset delineates tumor differentiation as follows: 34 patients with well-differentiated (Grade 1) tumors, 214 with moderately differentiated (Grade 2) tumors, 86 with poorly differentiated (Grade 3) tumors, and 3 with undifferentiated (Grade 4) tumors. The patients’ age distribution ranged from 24 to 83 years, with the median age being 58 years. All of this information can be found in Table S1. Additionally, to validate the proposed method, an external validation was performed on 50 randomly selected patients from TCGA-LIHC, with relevant details provided in Table S2.

Workflow overview

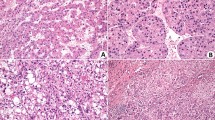

As shown in Fig. 1A, the pipeline from data preprocessing to prognostic prediction and interpretability analysis is outlined. Specifically, H&E-stained HCC pathology slides from the existing dataset are digitized. This project involved 57 pathologists with varying levels of experience, including 27 junior doctors, 16 mid-level doctors, and 14 senior doctors. Senior doctors performed additional annotation and correction on the initial WSI labels, enhancing the accuracy of full-cell segmentation and classification. Over more than two years, they used a semi-automated approach to accurately segment and classify multiple cell types across the WSIs, completing 387 cases. These cells included tumor cells, vascular endothelial cells, lymphocytes, fibroblasts, biliary epithelial cells, and hepatocytes. Any remaining cell types were grouped together as ‘other’. Annotations on the WSI were made using QuPath software40 (for more details, see METHOD DETAILS). After obtaining the full-cell segmentation and classification results from the WSI, we selected non-overlapping regions with the greatest diversity of cell types. These regions, enriched with diverse cell types, were considered as key cellular communities. In each key cellular community, cell graphs were constructed based on cell centroids using the Minimum Spanning Tree algorithm. The edges in the cell graph were considered indicative of interactions between cells. Furthermore, Transformer-based or graph-based methods were applied to model interactions between cellular communities, ultimately yielding a recurrence risk score. The recurrence risk score was then used to construct Kaplan-Meier curves for recurrence-free interval analysis, as well as to predict 1-year, 3-year, and 5-year recurrence outcomes. A multiscale interpretability analysis was performed to provide insights at the cellular level, cell community level, and tissue level.

A Overview of cell segmentation and classification, the construction of cellular networks for intercellular communication, and the subsequent prediction of patient risk scores based on communication between cell communities, which are then used for downstream tasks. B Initial full-cell segmentation and classification on WSIs are performed by junior pathologists and refined by senior experts. Cellular communities are then selected based on the diversity of cell types. The cell graphs are constructed by combining the centroids of cells with the minimum spanning tree (MST) algorithm. A GNN with a heterogeneous message-passing function and an interpretable gated attention module extracts local features from cell graphs constructed based on cellular communities. Then, a Transformer encoder processes interactions between cellular communities. Finally, a fully connected layer calculates the risk score for HCC recurrence, which is utilized for Kaplan-Meier curve analysis and time-dependent receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis. Spatial biomarker discovery is conducted through the interpretable gated attention module along with cell graph and cellular community distribution. C In the innovative HeteroMessage Graph Neural Network module, the local cell graph is used as input. The heterogeneous message passing function’s identity matrix explicitly represents cell types to facilitate communication between cells. The interpretable gated attention module quantifies the attention scores of each cell.

For detailed prognostic prediction and multi-scale interpretability analysis, as shown in Fig. 1B, the Hybrid Graph Neural Network-Transformer system (HGTs) uses multiple cell graphs to generate patient-level features. A fully connected layer calculates a risk score for local recurrence in HCC. This score is used to generate Kaplan-Meier curves and perform time-dependent ROC analysis for evaluating disease progression. By balancing local pathological structures and integrating global signatures across the WSI, this system facilitates multi-scale biomarker discovery. As shown in Fig. 1C, HGTs innovatively incorporates a heterogeneous message-passing function within the GNN, enabling each cell to recognize its own type during interactions with surrounding cells. An interpretable gated attention module quantifies the attention scores of cells in prognostic prediction. While HGTs is applied here to HCC, it can be directly applied to other organ histology, given organ-specific training data.

Subsequently, a cohort of 337 HCC patients from five clinical institutions was stratified based on recurrence status, with censored and uncensored groups handled separately. For both the censored and uncensored patients, the data were randomly divided into three parts: 64% for training (215 patients), 16% for internal validation (53 patients), and the remaining 20% (69 patients) served as internal testing and biomarker discovery. Additionally, 50 cases were randomly selected from the TCGA-LIHC cohort to serve as an independent external validation dataset.

Comprehensive evaluation of external test cohort: model comparison and component analysis

HGTs employed a dual-stage, end-to-end approach that first leverages the local context extraction capabilities of GNNs, and then incorporates the global contextual insights provided by the Transformer. To quantitatively assess the performance of HGTs and compare it with other contextual models, we used the C-index as our primary metric of assessment. Additionally, to thoroughly validate HGTs’ effectiveness and the contribution of each component, we conducted studies on model architecture and parameter settings. These studies clarified the impact of each component on the HGTs’ overall performance.

Performance comparison with other contextual models

We conducted comparative analyses with leading models such as DeepGraphSurv37, Patch-GCN38, and TEA-graph39, each renowned for their proficiency in enhancing patient-level predictive analytics. In these models, a CNN first extracts information from image patches. Then, a graph network is constructed based on spatial relationships to further explore these local perspectives. As shown in Fig. 2A, the standalone HGTs demonstrates superior performance, achieving a C-index of 0.672. This represents a statistically significant improvement of 5.1% (p < 0.0001) over the best-performing alternative, TEA-graph (C-index of 0.621). Compared to other models, the HGTs shows an 11.0% improvement over DeepGraphSurv (C-index of 0.562) and a 7.8% improvement over Patch-GCN (C-index of 0.594). Overall, the HGTs outperforms these alternatives by an average of 8.0%, highlighting the limitations of relying solely on pixel-level features in the initial processing stage.

A A comparison of HGTs with other state-of-the-art models, including DeepGraphSurv, Patch-GCN, and TEA-graph. B An analysis of the impact of various node features within HGTs, encompassing the Nucleus/Cell area ratio (Nucleus/Cell), Coordinates (Coord), a combination of Coordinates and Morphological Features (Coord + Morph Features), and a fusion of Coordinates with the Nucleus/Cell area ratio (Coord + Nucleus/Cell). C A study exploring the effects of varying the number of GNN layers in HGTs and their impact on model performance. D Comparison of the effects of incorporating PairNorm and Residual Connections into HGTs, evaluating their impact on model performance. E An analysis of different graph construction methods used in HGTs and their respective impacts on the model’s effectiveness. F Experiments evaluating different feature fusion strategies in the second stage, specifically comparing GAT, HyperGraph, and Transformer.

Exploration of HGTs in the first stage

As shown in Fig. 2B, using spatial coordinates combined with the ratio of nuclear area to cell area achieved the highest C-index, outperforming other cellular features. Spatial coordinates alone capture the spatial relationships within the TME, yielding a C-index of 0.599. However, when combined with all morphological features, the C-index drops to 0.579, indicating potential complexity in feature interaction and the risk of overfitting, which diminishes the model’s effectiveness. Considering only the ratio of nuclear area to cell area, which highlights cellular heterogeneity but lacks spatial information, the C-index is 0.506. In the TME, focusing solely on neighboring cells might not fully capture the entire scenario, especially when neighboring cells are predominantly of the same type. Our studies on the number of layers revealed that increasing the number of layers can enhance the model’s performance to some extent, as depicted in Fig. 2C. Nonetheless, considering the limited number of cells within a patch, excessive layers in the GNN are unnecessary. In our research, we further integrated PairNorm41 and skip connections8 into the GNN. Although these methods are theoretically effective in deeper GNN architectures, as demonstrated in Fig. 2D, they did not improve the performance of HGTs and even resulted in a decline. Additionally, we explored different graph construction methods like K-Nearest Neighbors, Delaunay triangulation and Minimum Spanning Tree, analyzing their impact on the model’s performance. As shown in Fig. 2E, our experimental results indicate that the Minimum Spanning Tree achieved the best performance, with a 5% improvement over the second-place Delaunay triangulation method. A preference for sparse graphs may yield better performance.

The Transformer for interaction among cellular communities enhances the C-index

As a two-stage model, the HGTs not only leverages the strengths of end-to-end modeling but also accommodates flexible integration strategies, such as incorporating Transformer, HyperGraph42,43 and Graph Attention Network44 (GAT) for contextual analysis of WSI. Among the HGTs variants, the HyperGraph variant, with a C-index of 0.650, outperforms the GAT variant, which has a C-index of 0.634, showing a 1.6% improvement, as detailed in Fig. 2F. Both GAT and HyperGraph strategies are effective in analyzing WSIs using explicit graph structures. However, they are surpassed by the Transformer strategy, which achieves the highest C-index of 0.672, marking a 2.2% improvement over HyperGraph and a 3.8% improvement over GAT (both p < 0.0001).

Visualizing spatial features and heterogeneous message passing function in deep GNN layers

As shown in Fig. 2B, cell spatial coordinates are critical for accurately representing the spatial relationships within the TME. Traditional graphs inherently possess permutation invariance45. While they can depict inter-cellular relationships, cell graphs lacking spatial coordinates may inaccurately represent cellular spatial arrangement, as demonstrated in Fig. 3A.

A The sequence of images includes: (1) a patch image from a WSI depicting a cellular community; (2) a cell graph constructed based on cellular coordinates; (3) a cell graph with randomly altered cellular coordinates; and (4) a cell graph without cellular coordinates. B Depiction of node feature transformations at each layer of GNN processing, visualized using t-SNE. C Similarity matrices of cell identity matrices across seven cell types, illustrating changes through GNN layers, were computed using cosine similarity.

In various tasks, such as node/graph classification and link prediction, standard GNN models like Graph Convolutional Network46 (GCN), Graph Isomorphism Network47 (GIN), and GAT typically yield strong results with only 2 to 4 layers. However, increasing the number of layers often leads to diminished performance, primarily due to the over-smoothing phenomenon48. To better illustrate the efficacy of the heterogeneous message-passing function in deeper GNN layers, a pivotal finding from our research is shown in Fig. 3B. It demonstrates that our chosen method fosters diverse spatial distributions for different cell types. In t-SNE visualizations, the features of different cell types remain somewhat sparse and separated. Further analysis through a visualization of this function’s parameters, as seen in Fig. 3C, reveals that the identity matrices of different cell types exhibit distinct specificity. In each layer, the absolute similarity scores between different cell types are generally below 0.3, indicating the strong heterogeneity among different cell types. This pattern underscores the critical role of heterogeneous message passing function and the inadequacies of homogeneous function to fully capture the intricate nuances of cellular communication. To underscore this, we conducted experiments with a deep-layered HGTs. In these experiments, the heterogeneous message-passing function was replaced with a homogeneous variant, and cell types were represented using either a single numerical value or one-hot encoding. As detailed in Fig. S1, the model struggled with convergence even on the training set. In contrast, when using the heterogeneous message passing function with a 10-layer GNN network on the training set, the loss converged normally, and the C-index improved significantly by more than 20%.

Independent prediction of recurrence

In the analysis of local recurrence among 69 HCC patients from the external test set, patients were categorized into high-risk and low-risk groups based on tumor risk scores12. As shown in Fig. 4A, DeepGraphSurv yielded an HR of 1.57 (CI: 0.72 to 3.43, p-value: 2.54e−1), while Patch-GCN reported an HR of 2.40 (CI: 1.18 to 4.88, p-value: 1.35e−2), and TEA-graph had an HR of 2.63 (CI: 1.27 to 5.45, p-value: 5.3e−3). The HGTs identified a high-risk group showing a HR of 3.77 (CI: 1.80 to 7.90) and a significant p-value of 1.8e−4. Comparatively, the GAT variant of HGTs had an HR of 3.21 (CI: 1.24 to 8.30, p-value: 1.11e−2), and its HyperGraph variant recorded an HR of 3.15 (CI: 0.96 to 10.34, p-value: 4.13e−3). Among these models, the HGTs demonstrated the highest HR and the lowest p-value, highlighting its effectiveness in risk stratification for local recurrence of HCC.

As shown in Fig. 4B, during the critical first year, a period often recognized as challenging for predictions, the HGTs achieved an impressive AUC of 0.817 (CI: 0.682 to 0.943), compared to DeepGraphSurv (0.677 (CI: 0.507 to 0.817)), Patch-GCN (0.718 (CI: 0.560 to 0.861)), TEA-graph (0.657 (CI:0.437 to 0.873)), HGTs (GAT) (0.729 (CI: 0.576 to 0.865)), and HGTs (HyperGraph) (0.669 (CI: 0.509 to 0.803)), demonstrating its robustness in early detection. Moving to the 3-year interval, HGTs exhibited a slight decrease in performance with an AUC of 0.726 (CI: 0.592 to 0.849), while surpassing DeepGraphSurv (0.557 (CI: 0.409 to 0.706)), Patch-GCN (0.650 (CI: 0.499 to 0.794)), TEA-graph (0.659 (CI: 0.481 to 0.820)), HGTs (GAT) (0.622 (CI: 0.476 to 0.760)), and HGTs (HyperGraph) (0.596 (CI: 0.450 to 0.726)). This trend continued into the 5-year mark, where HGTs maintained a competitive AUC of 0.687 (CI: 0.552 to 0.820), outperforming DeepGraphSurv (0.579 (CI: 0.428 to 0.727)), Patch-GCN (0.680 (CI: 0.538 to 0.805)), TEA-graph (0.559 (CI: 0.407 to 0.717)), HGTs (GAT) (0.651 (CI: 0.500 to 0.795)), though it was slightly outdone by HGTs (HyperGraph) (0.724 (CI: 0.591 to 0.838)). These results collectively underscore the efficacy of HGTs in delivering accurate prognoses, particularly in the critical first year, and maintaining a consistent performance over extended periods, thereby affirming its utility in clinical applications for cancer prognosis.

Integrating risk scores with clinical factors and immunohistochemistry for predicting HCC recurrence

In addition to the recurrence risk scores predicted by HGTs, clinical multimodal information such as age, gender, and tumor differentiation has also been integrated. In univariate analysis, tumor differentiation alone did not significantly predict recurrence (C-index=0.502, CI: 0.421 to 0.591, P = 0.76). Multivariate analysis revealed that a combined model incorporating clinical factors and the recurrence risk score markedly improved predictive performance (C-index=0.702, CI: 0.618 to 0.782). Furthermore, the inclusion of the immunohistochemical marker Ki-6749 achieved a C-index of 0.823 (CI: 0.752 to 0.886).

Validation of HGTs on TCGA-LIHC

The HGTs underwent independent external testing on a random subset of the TCGA-LIHC dataset, consisting of 50 cases, with results shown in Fig. S2. Note that the LIHC cohort does not have information on local recurrence time, only on survival time. However, when we directly applied the model trained on the Qingdao University dataset to the LIHC cohort, it still showed a certain degree of generalizability, achieving a C-index of 0.649. In the division of high and low-risk groups, there was a significant risk difference, with an HR of 3.13 (CI: 1.15 to 8.49, p-value: 1.82e−2). For 1-year, 3-year, and 5-year survival predictions, the time-dependent ROC achieved AUC values of 0.685 (CI: 0.381 to 0.944), 0.659 (CI: 0.437 to 0.844), and 0.613 (CI: 0.343 to 0.833), respectively. These results indicate that HGTs has a good generalization capability and can effectively predict survival outcomes even when applied to an independent cohort.

Multi-scale interpretability analysis at the cellular, cellular community, and tissue levels

To interpret why HGTs can achieve high-performance prognosis and explore which features largely contribute to risk scores, we performed multi-scale interpretability analysis. As shown in Fig. 1C, the HGTs incorporates a mechanism termed interpretable gated attention module, allowing for nuanced measurement of the influence of cells on HCC recurrence prediction. Furthermore, by integrating the local cellular community perspective and the global WSI perspective, a multi-scale interpretability analysis can be conducted.

Quantitative analysis of cell-level impact on prognosis

As depicted in Fig. 5A, the distribution of attention scores for each cell type is quantified using density-normalized KDE plots, revealing significant differences in attention score distributions across different cell types. Using 0.5 as the threshold, cells with attention scores greater than 0.5 are considered to have a significant impact on HCC prognosis prediction. Most of the attention scores for tumor cells, lymphocytes, and hepatocytes fall within the range of 0.5–1. As shown in Fig. S3A, the mean and variance of the attention scores for seven cell types are elucidated, with the mean values being 0.669, 0.482, 0.655, 0.265, 0.144, 0.536, and 0.750, respectively. Our analysis indicates that tumor cells contribute more significantly to the patient’s risk score compared to normal hepatocytes, as a previous study has reported50. Although cells categorized as ‘Other’ also receive significant attention from the model, we do not consider them due to the inability to pinpoint exact cell types. The experimental results reveal that the model actively focuses on tumor cells and lymphocytes, attributing substantial attention scores to these cell types, which reflects their critical roles in HCC local recurrence prediction. Further quantification of the proportion of each cell type in the WSIs of patients from both risk groups reveals that patients in the high-risk group tend to have more tumor cells (p < 0.05) and fewer lymphocytes (p < 0.05), as illustrated in Fig. 5B and Fig. S3B. This suggests the increased presence of tumor cells and reduced immune response in contributing to higher recurrence risks51.

A The figure displays Density-Normalized Kernel Density Estimate (KDE) plots of attention scores for different cell types, showing the distribution of attention scores across various cell types. Attention scores from 0 to 1 represent the model’s level of attention to cells from low to high. B Boxplots show the distribution of ‘Tumor cells’ and ‘Lymphocytes’ proportions in high and low recurrence risk groups. KDE curves illustrate the normalized density distribution of these cell proportions for each risk group, providing a detailed view of their distributions. C Boxplots compare the distribution of ‘Interaction Frequency’ for tumor-tumor and tumor-lymphocyte interactions between high and low recurrence risk groups. KDE curves depict the normalized density distribution of these interactions for each risk group. D A localized interpretability heatmap illustrating the model’s detailed focus on three characteristics of cancer cells. E Comparing two-dimensional entropy and spatial visualization of key cellular communities in low- (mid) and high-risk (bottom) cases. The green squares denote the spatial locations of key cell communities. In a low-risk (mid) case, these areas exhibit localized clustering, while in a high-risk (bottom) case, they display a more dispersed distribution. F Exemplar lymphocyte aggregation areas from low- (top) and high-risk (bottom) cases. G Exemplar the degree of fibrosis from low- (top) and high-risk (bottom) cases.

Key cellular communities and interaction patterns

Building on the previous observation, it becomes clear that numerical quantification or viewing individual cells without their contextual environment may offer an incomplete perspective. Based on the established cell graphs, it is hypothesized that interconnected cells engage in intercellular communication, as illustrated in Fig. 3A. By analyzing the interaction frequencies between tumor cells and lymphocytes, as shown in Fig. 5C, it was observed that in the low-risk group, tumor cells exhibited closer interactions with lymphocytes (p < 0.0001) and lower frequencies of interaction with other tumor cells of the same type (p < 0.0001). This indicates that in cellular communities with diverse cell types, higher interaction frequencies between tumor cells and lymphocytes may contribute to a better prognosis. As shown in Fig. 5D, analysis of key cellular communities revealed that the HGTs specifically focused on tumor cells exhibiting a high nucleus-to-cytoplasm (N/C) ratio, nuclear division, and stronger heterogeneity—traits commonly associated with poor differentiation52. In addition, the spatial distribution of key cellular communities in high- and low-risk patients was quantified using two-dimensional entropy, as shown in Fig. 5E. The higher entropy observed in the high-risk group (p = 0.0103) indicates a more dispersed distribution of key cellular communities, in contrast to the low-risk group, where communities display localized clustering. This reflects greater spatial heterogeneity and more complex cellular interaction patterns within the TME, which are associated with poorer prognosis.

The tissue-level analysis of immune infiltration and fibrosis in adjacent peritumoral tissues

By embedding the interpretable gated attention module that accounts for diverse cell types and complex interaction patterns within local cell graph networks, this approach can be generalized to all cell graphs in WSI. This enables comprehensive interpretative analysis of WSI, revealing key tissue structure features. Combined with the explainable heatmaps from HGTs, expert pathologists can explore tissue-level biomarkers. As shown in Fig. 5F, from a global interpretability perspective, patients in the low-risk group exhibit more extensive immune infiltration in tumor tissues, while in the high-risk group, immune cells are primarily clustered around the periphery of the tumor tissues. Furthermore, analysis of local cell communities reveals that, in low-risk patients, there is a higher degree of intermingling between lymphocytes and tumor cells. In contrast, in high-risk patients, fibrous tissue isolates lymphocytes from tumor cells, supporting the conclusion shown in Fig. 5C. To further validate the impact of immune infiltration on local recurrence of HCC, we grouped 337 patients from five clinical institutions based on the presence of significant immune infiltration—177 patients with and 160 without. The analysis revealed a significant difference (p = 0.003) with an HR of 1.60 (1.17–2.18), as shown in Fig. S5. Moreover, as shown in Fig. 5G, in patients with either mild or severe pseudolobules, the HGTs consistently focuses on the fibrous septa within the adjacent peritumoral tissues. From a global perspective, fibrosis in this region is often more severe in high-risk patients, suggesting that the extent of fibrosis in adjacent peritumoral tissues may influence the risk of local recurrence in HCC.

Discussion

Considering the definite cell types within the TME and their interactions is crucial for improving prognosis prediction, risk stratification, and the discovery of spatial relational biomarkers. Our study accomplishes a pioneering dataset of 387 annotated WSIs for full-cell segmentation and classification, created by professional pathologists over two years. Based on this, we present an interpretable, weakly supervised system called HGTs, designed to predict local recurrence of HCC. HGTs consists of two gradual stages: first, a GNN with heterogeneous message passing extracts detailed information from local cellular communities, enriching cell-specific interactions within the TME. The gated attention module quantifies the prognostic impact of cells, enabling multi-scale interpretability by integrating both local cellular community and global WSI perspectives. In the second stage, a Transformer encoder integrates contextual information across the WSI, capturing complex inter-community relationships. HGTs significantly improves the accuracy of HCC prognosis prediction. Ultimately, a set of spatial relationship markers that influence local recurrence of HCC was discovered at multiple scales.

Against renowned models such as DeepGraphSurv37, Patch-GCN38, and TEA-graph39, the HGTs demonstrates superior performance. It achieves a C-index of 0.672, which represents an 8% improvement over the other leading methods on the same dataset. While pixel-based image methods efficiently process all pixel points within an image patch, they lack a refined concept of entities (cells or cellular communities), often failing to discern relevant from irrelevant information. Moreover, these methods heavily rely on the ability of pre-trained models to extract local features, making it difficult to effectively optimize feature extraction in an end-to-end manner. The HGTs leverages the GNN’s ability to effectively capture inter-cellular communication, combined with the Transformer’s capability to model inter-community interactions. This combination allows for end-to-end training, setting HGTs apart from the aforementioned approaches.

In the first stage of the HGTs, we integrated spatial coordinates as essential node features to counteract potential misrepresentation of cellular spatial arrangements. By further incorporating a heterogeneous message-passing function within the GNN, HGTs ensure that each cell and its surrounding cells are aware of the cell’s type during their interactions. This is tailored to holistically scrutinize both spatial relationships and cellular heterogeneity. In shallow GNN methods, information propagation and aggregation are typically limited to adjacent cells, which may result in overlooking interactions between distant cells. In contrast, HGTs, with its unique heterogeneous message passing, propagates and integrates information through deep layers. This approach captures dependencies between distant cells more effectively, leading to a more precise understanding of their complex interactions and relationships. Additionally, exploring cell graph construction reveals that using the MST effectively eliminates redundant edges and reduces data noise. This approach highlights critical cell interactions and preserves essential structural information. In the second stage of the HGTs, in the WSI, we compared three different methods: HyperGraph, GAT, and Transformer (ours). The experimental results demonstrate that utilizing the self-attention mechanism in Transformers can achieve higher performance, with the C-index being 2.2% higher than the HyperGraph. The utilization of the self-attention mechanism in Transformers enabled the unsupervised and adaptive extraction of relationships among arbitrary cell communities.

Additionally, HGTs can more distinctly stratify patients into low- and high-risk groups, yielding a higher hazard ratio. This stratification facilitates the exploration of interpretable feature differences between the groups, potentially uncovering key biomarkers associated with local recurrence of HCC. In predicting local recurrence of HCC at 1, 3, and 5 years, the proposed system shows enhanced sensitivity to the more challenging 1-year recurrence. The integration of risk scores with clinical factors and immunohistochemical markers significantly improves the prediction of HCC recurrence, thereby supporting more personalized and effective post-treatment surveillance strategies. Furthermore, the external validation on the TCGA-LIHC dataset confirmed the robust generalizability of the HGTs model.

To address the challenge of limited interpretability of DL-based risk scores, different methods like post-hoc interpretability are employed. The HGTs, with its interpretable gated attention module, combines the local cellular community perspective with the global WSI perspective, offering multi-scale interpretability that spans from cells, through cellular communities, to the tissue level. Specially, high-risk patients exhibit a higher number of tumor cells and fewer lymphocytes, suggesting that increased tumor cell density and a reduced immune response are associated with elevated recurrence risks53. Analysis of localized key cell communities shows that higher interaction frequencies between tumor cells and lymphocytes suggest a better prognosis, whereas higher interaction frequencies between tumor cells themselves are associated with poorer outcomes. This indicates that patients with a rich infiltration of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) tend to have a more favorable outcome. TILs have already been applied as biomarkers in clinical practice54. Additionally, it shows that tumor cells with high nucleus-to-cytoplasm ratios, nuclear division, and stronger heterogeneity are particularly critical in influencing prognosis. These features are associated with poorly differentiated cancer cells. Furthermore, high-risk patients exhibit more dispersed distributions of key cellular communities. This complexity may render the thorough removal of the tumor’s potential impacts more challenging and cause worse postoperative outcomes, thereby exacerbating the risk of local recurrence of the HCC. In addition, analysis at the tissue level revealed that the patients with abundant immune infiltration tend to have better prognoses. The fibrous septa between the pseudolobules in the cirrhotic regions are key areas55, possibly because the degree of cirrhosis affects the recurrence of HCC. Cirrhosis is clinically recognized as a risk factor for HCC50. The mortality of HCC associated with cirrhosis is increasing in some developed countries56. For patients with sparse lymphocyte infiltration around tumor cells and pronounced immune evasion features, immunotherapeutic approaches, such as immune checkpoint inhibitors, may be more effective treatment options. More frequent imaging and tumor marker monitoring may be required for these high-risk patients. Additionally, for patients with significant fibrous septa impact in cirrhotic areas on recurrence risk, antifibrotic treatment can be considered, and liver function should be closely monitored to prevent liver failure.

In summary, the HGTs approaches the biological entity from the cellular perspective, effectively extracting prognostically relevant, interpretable, high-resolution features from WSIs through end-to-end training of both local and global models. It supports cell-type awareness and provides multi-level interpretability across the cellular, cellular community, and tissue levels. To facilitate further research, we plan to gradually release the largest dataset to date, comprising precise seg-mentation and classification of up to seven primary cell types. This will enable more researchers to focus on exploring the relationship between relational features in digital pathology and patient prognosis. However, our current work focuses on H&E-stained slides, which provides a foundational benchmark for single-modal analysis. H&E staining provides only basic morphological features (nuclear/plasmic staining, tissue structure) and fails to capture key molecular markers (e.g. PD-L1, HER2, Ki-67) in the tumor microenvironment. This leads to the omission of biological pathway information relevant to the response to targeted therapy. In addition, current methods lack interpretable quantitative intercellular as well as intercellular community interactions on prognosis. Future research hinges on integrating multi-center, large-scale, multi-dimensional patient datasets. Specifically, incorporating spatial transcriptomics data will enhance the model’s ability to characterize molecular-morphological associations and develop a quantifiable, interpretable framework for cellular interactions.

Methods

Data description

This clinical dataset of HCC patients collected from five clinical institutions, and covered the period from December 2012 to October 2017. Relevant information is detailed in Table S1. This dataset includes patients who underwent curative hepatectomy for HCC and presented no distant metastasis at surgery. Post exclusion of cases lost to follow-up, the dataset was refined to 337 HCC patients who were then thoroughly analyzed. The cohort consisted of 285 male and 52 female patients. A total of 166 patients experienced recurrence, whereas 171 did not. Recurrence rates at 1 year, 3 years, and 5 years were observed to be 17.5%, 37.7%, and 64.4%, respectively. Informed consent was obtained from all participants. The tumor samples were consistently processed, entailing fixation in 4 neutral-buffered formalin, paraffin embedding, sectioning at 3 µm thickness, and hematoxylin-eosin (H&E) staining. For detailed histological examination, all 337 slides were converted into high-resolution WSIs using the NanoZoomer-XR C12000 system from Hamamatsu. We randomly selected 50 cases from TCGA-LIHC as an additional independent external validation, with the specific cases detailed in Table S2. A total of 17 patients died, while 33 remained alive. The mortality rates were 40% at 1 year, 30.77% at 3 years, and 30% at 5 years.

Full-cell segmentation and classification

These slides of tissues were digitized using NanoZoomer-XRC12000, Hamamatsu. The digitization process was carefully monitored for consistency. Following digitization, the images underwent a standardized preprocessing routine to correct any artifacts, adjust for brightness and contrast discrepancies, and ensure optimal clarity. All digitized images were further subjected to a quality control protocol, wherein any images with blur, artifacts, or staining inconsistencies were flagged for re-scanning. employed a semi-automated approach for multi-type cell segmentation and classification The project involved 57 pathologists with varying levels of experience, including 27 junior doctors and 16 mid-level doctors who performed the initial annotations. Their work was then reviewed and corrected by 14 senior doctors, resulting in a highly accurate dataset for full-cell segmentation and classification. Over more than two years, they employed a semi-automated approach to precisely segment and classify multiple cell types across the WSIs, ultimately completing 387 cases. These cells included: tumor cells, vascular endothelial cells, lymphocytes, fibroblasts, biliary epithelial cells, and hepatocytes. Any remaining cell types were grouped together as ‘other’.

Automated algorithms initially identified cell boundaries and classified them according to predefined morphological characteristics. However, due to the inherent heterogeneity of cellular structures, certain segments required manual intervention by specialized pathologists. Pathologists underwent training sessions that emphasized annotation consistency, particularly focusing on the unique challenges posed by heterogeneous cells. This dual approach, which combined automated precision with human expertise, ensured a thorough and accurate representation of cell types and their boundaries. A select elite group of pathologists reviewed the initial annotations. Their criteria followed a predefined set of guidelines that emphasized accuracy, consistency, and the clinical relevance of each annotation. A continuous feedback loop was established between the initial annotators and the review team. Any discrepancies were flagged, discussed, and reconciled, ensuring the final annotations met the highest standards of accuracy.

QuPath40 was chosen due to its robustness, user-friendly interface, and extensible scripting capabilities. Its ability to handle large-scale annotations and provide real-time feedback made it particularly suitable for our study. Cells that couldn’t be classified with a confidence level above a certain threshold were flagged for manual review by the pathologists. Following the annotation process, QuPath’s extensive data extraction tools were utilized. We extracted both optical and morphological characteristics of the cells. Optical features, like intensity and texture, and morphological features, such as cell size, shape, and boundary irregularities, were recorded. However, variations in staining across different WSIs were observed, and the optical features extracted using QuPath introduced noise into the cell feature analysis. As a result, these optical features were excluded, and only morphological information was considered. Extracted data was then subjected to normalization processes to account for variances across different slides or scanning sessions. The resulting CSV files contained detailed records for each cell, facilitating subsequent deep learning analysis, with node features detailed in Table S3.

Patch sampling based on cell diversity

The direct analysis of data from WSIs presents significant challenges due to the vast amount of cellular information they encompass. To address this challenge, our initial step is to determine the patch size for the curation process. We selected a target region size of 1024×1024 pixels at the maximum magnification for its computational efficiency and effectiveness. With these parameters established, we employ a sliding window approach to partition the WSI into non-overlapping regions. Let W represent patches extracted from the WSI, and C donate the number of distinct cell types within each region. We then selected the top k patches with the highest number of cell types, a process donated as \(S={{Top}}_{k}\,(C\left(W\right))\). In this experiment, k = 32 is chosen to balance computational feasibility and the need to capturing representative cell communities S, thereby reducing the likelihood of missing critical cellular heterogeneities.

Cell-graph construction

When constructing the graph structure, we adopt a method based on the MST. The MST is typically used to connect all nodes \(V\) in a graph \(G\left(V,E\right)\) where \(V\) is the set of vertices (nodes) and \(E\) is the set of edges, while ensuring the total weight \(W\) is minimized and that there are no cycles in the graph. Mathematically, the problem can be defined as:

where \(w\left(u,v\right)\) represents the weight of the edge between nodes \(u\) and \(v\). In our application, the weight \(w\left(u,v\right)\) is determined by the Euclidean distance between cell centroids. The initial step involves calculating the Euclidean distance between each pair of cell centroids, resulting in a complete graph. The Euclidean distance between two points \(p\left({x}_{1},{y}_{1}\right)\) and \(q\left({x}_{2},{y}_{2}\right)\) in a 2D space is calculated as:

In this context, the edge weight \(w\left(u,v\right)\) for each pair of nodes \(u\) and \(v\) in the graph corresponds to their Euclidean distance. Applying the MST algorithm to this weighted graph connects all nodes with the minimum possible total weight, effectively capturing the spatial relationships among the cell centroids.

In addition to the MST approach, other graph construction strategies include:

-

1.

KNN Graph Construction: In the KNN method, each cell is treated as a node, and edges are established based on the Euclidean distance between cells. For each node, the 5 nearest neighbors (K = 5) are selected, and edges are created to connect these neighboring nodes, effectively capturing local cell interactions.

-

2.

Delaunay Triangulation Graph Construction: Delaunay triangulation is a spatial geometric method that connects cells by forming a set of non-overlapping triangles. This method ensures that the circumcircle of any triangle does not contain any other cells.

Calculation of 2D entropy

To quantify the spatial distribution of 2D coordinates, we compute the entropy of the distribution using the following approach:

-

1.

Coordinate Data Preparation: Begin with a set of 2D coordinates, organized as an N×2 array, where N represents the number of data points.

-

2.

Histogram Calculation: Compute a 2D histogram of the coordinates using 4 bins in each dimension. This histogram captures the spatial distribution of the coordinates.

-

3.

Normalization: Normalize the histogram by dividing each bin count by the total number of points, converting the histogram into a probability distribution where the sum of all bin probabilities equals 1.

-

4.

Entropy Computation: Calculate the entropy H of the 2D distribution using the formula:

where \(P\left(i,j\right)\) denotes the normalized probability of each histogram bin, and ϵ is a small constant (1e-10) to avoid taking the logarithm of zero.

Hybrid Graph Neural Network-Transformer system

The HGTs is an end-to-end system consisting of two stages. In the first stage, the GNN with heterogeneous message passing function was proposed to gain insights into the information exchange between cells. The interpretable gated attention module quantifies the attention scores of each cell. In the second stage, the Transformer was employed to integrate the interactions between cellular communities.

HeteroMessage Graph Neural Network. Specifically, as illustrated in Fig. 1B, each cell type is associated with a distinct message-passing function, denoted as \(M{P}_{\text{c}}\), which allows cells to transmit information to neighboring cells.

The message-passing process involves three key steps:

-

1.

Message Passing: For each cell u, a message is generated and sent to its neighboring cells v through the message-passing function \(M{P}_{{c}_{u}}\), which is specific to the cell type \({c}_{u}\). The message passed from cell u to its neighbors is formulated as \({m}_{u\to v}=M{P}_{{c}_{u}}\left({h}_{u}\right)\), where \({h}_{u}\) is the current feature representation of cell u.

-

2.

Aggregation: Each cell v aggregates the incoming messages from its neighbors \(u\in N\left(v\right)\) by summation, which has a higher expressive power compared to methods like mean or max aggregation: \({a}_{v}=\sum _{{u}\in N\left(v\right)}{m}_{u\to v}\)

-

3.

Update: The cell v then updates its state by combining its original features with the aggregated messages:

where\(\,{W}_{{c}_{v}}\) is the weight matrix corresponding to the class \({c}_{v}\) of node v. \(\sigma\) is the activation function. \(N\left(v\right)\) is the set of neighbor nodes of node v. After extensive cellular information exchange, we further explore the relationships between directly and indirectly interacting cells through the interpretable gated attention module, defined as:

Here, \({h}_{{cells}}\) \(\in\) \({R}^{N\times D}\) is the input matrix of cell features, where N is the number of cells and D is the feature dimension. \({W}_{a}\), \({W}_{b}\), and \({W}_{c}\) are weight matrices of the linear layers. \({b}_{a}\), \({b}_{b}\), and \({b}_{c}\) are bias terms. \(\tanh\) is the hyperbolic tangent activation function. This method allows for obtaining the importance scores of cells: \({{AtteScore}}_{{cells}}\in\) \({R}^{N\times 1}\). Subsequently, \({h}_{{CellCommunity}}\) refers to the features representing local cellular interactions are obtained through the Global Mean Pooling method, represented as:

where \(\left|V\right|\) is the total number of cells in the cellular community.

Integrating cellular community interactions with the Transformer

To capture interactions among key cellular communities in WSIs, we use a Transformer architecture. The core is utilizes multi-head self-attention mechanisms to process sequences of embedded cellular community features extracted from the first stage of HGTs. Unlike approaches that construct explicit graph-based representations to model interactions between patches, it leverages self-attention mechanisms to implicitly capture cellular community interactions. The attention mechanism is formalized as follows:

where \({Q}_{i}\) (query) is a projection that represents the focus or intent of the model when processing interactions between cell communities. \({K}_{i}\) (key) is another projection that works with the query to measure the relevance of different cell communities. \({V}_{i}\) (value) contains the actual cellular community features which are weighted according to the attention scores, derived from the query-key interaction to generate the final output. \({d}_{{Cellcommunity}}\) represents the feature dimension of \({f}_{{CellCommunity}}\). Additionally, multi-head attention allows the model to jointly attend to information from different representation subspaces.

where \({W}^{O}\) is a weight matrix used to combine the outputs from each attention head. By leveraging the Transformer, our model effectively integrates and processes the spatial context of cell communities across the WSI. This enables accurate and comprehensive pathological analysis.

Interpretable analysis and visualization

In our analysis, we investigated the interpretable gated attention module within HGTs, which provides attention scores for each cell. These scores are normalized to a range of 0-1, with higher values indicating greater attention and impact on prognostic predictions, establishing cell-level interpretability. The importance of each cell can be visualized using a jet color bar, where colors closer to red signifies higher importance. By combining this with the pathological images of key cell communities and the spatial positions of cells, we can further identify significant cells from the local context. Additionally, leveraging the graph networks constructed from cell communities and their spatial distribution, we can uncover community-level interpretability, providing deeper insights into the prognostic predictions. Since each cell community can serve as the input for the first stage of HGTs to obtain attention scores, we used all local cell communities within the WSI as inputs for a global interpretability analysis. This approach allows us to identify significant tissue-level interpretability across the entire WSI.

The training configuration of HGTs

In our study, we employed a two-stage architecture comprising a GNN and a Transformer Encoder Network. Graph Neural Network Configuration: The GNN was structured with 1 pre-message passing layer, 10 message passing layers, and 1 post-message passing layer. Batch normalization was enabled to stabilize and accelerate the learning process. The aggregation method used was addition, and L2 normalizations were applied to ensure consistent and stable training. Transformer Encoder Network Configuration: The Transformer encoder was configured with 2 layers and utilized a multi-head self-attention mechanism with 4 heads. The feedforward network size was set to 512, and a dropout rate of 0.1 was applied to mitigate overfitting. All other parameters were set to the default values provided by PyTorch’s Transformer encoder implementation. Hardware Configuration: Our experiments were conducted on a hardware setup equipped with two NVIDIA V100 GPUs, boasting 32GB of memory. The loss function can be expressed as:

where \(n\) is the number of samples in a batch. \(\theta\) is the predicted hazard value from the model. \(\delta\) is censoring indicator, represented by censor. It is 1 if the event has occurred, 0 otherwise. \(R\) is risk set matrix. Each element \({R}_{{ij}}\) is 1 if the recurrence time of the \({j}^{{th}}\) sample is greater than or equal to that of the \({i}^{{th}}\) sample, and 0 otherwise. The Adam optimizer was employed with a base learning rate of 0.001. The maximum number of training epochs was set to 1000 to ensure convergence.

Quantification and statistical analysis

To plot the Kaplan-Meier curves, we aggregated out-of-sample risk predictions from the external test dataset and plotted them. In Kaplan-Meier analysis, we use the log-rank test to determine if the differences in survival time and recurrence time between two distributions are statistically significant (P-value < 0.05). One of our evaluation metrics is the C-index, which assesses the accuracy of the predicted risk scores’ ordering. A perfect C-index of 1.0 signifies that all predicted risk values align correctly with the recurrence or survival times, whereas a score of 0.5 indicates randomness in predictions. Based on the external independent test set, we performed 1000 bootstraps to calculate the median and confidence interval of the C-index. In addition to C-Index, we also report Cumulative/Dynamic AUC, a time-dependent measure of model performance that evaluates how well the model stratifies patient risk across various time points, and additionally corrects for optimistic bias from censorship via computing an inverse probability of censoring weighting. To assess differences in cell counts between high and low-risk groups, differences in intercellular interaction frequency, and variations in cellular community distribution, use the Mann-Whitney U test. Significance levels in this figure are denoted as follows: **** (p < 0.0001) indicates highly significant, *** (p < 0.001) indicates very significant, ** (p < 0.01) indicates significant, * (p < 0.05) indicates marginally significant, and ns indicates not significant. For all boxplots, boxes indicate the 1st, median, and 3rd quartile values of the data distribution, and whiskers extend to data points within 1.5 × the interquartile range. To further illustrate the true distribution of the data, we use a KDE plot to display the density-normalized distribution.

Data availability

The TCGA diagnostic whole-slide images and corresponding clinical data used in this study are publicly available from the NIH Genomic Data Commons (GDC) portal at https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/projects/TCGA-LIHC. Our comprehensive full-cell segmentation and classification dataset for WSIs is accessible at https://github.com/Yuan1z0825/HGTs.

Code availability

The source code for the HGTs algorithm is openly available on GitHub under the GNU General Public License at https://github.com/Yuan1z0825/HGTs. All analysis scripts and implementation details are maintained in this repository.

References

Arneth, B. Tumor microenvironment. Medicina 56, 15 (2019).

Calderaro, J. et al. Intra-tumoral tertiary lymphoid structures are associated with a low risk of early recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Hepatol. 70, 58–65 (2019).

Renne, S. L. et al. Vessels encapsulating tumor clusters (VETC) is a powerful predictor of aggressive hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 71, 183–195 (2020).

Feng, Z. et al. Preoperative CT for characterization of aggressive macrotrabecular-massive subtype and vessels that encapsulate tumor clusters pattern in hepatocellular carcinoma. Radiology 300, 219–229 (2021).

Liu, Y. et al. Identification of a tumour immune barrier in the HCC microenvironment that determines the efficacy of immunotherapy. J. Hepatol. 78, 770–782 (2023).

Sheng, J. et al. Topological analysis of hepatocellular carcinoma tumour microenvironment based on imaging mass cytometry reveals cellular neighbourhood regulated reversely by macrophages with different ontogeny. Gut 71, 1176–1191 (2022).

Campanella, G. et al. Clinical-grade computational pathology using weakly supervised deep learning on whole slide images. Nat. Med. 25, 1301–1309 (2019).

He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S. & Sun, J. In Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition 770–778 (2016).

Ronneberger, O., Fischer, P. & Brox, T. In Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention–MICCAI 2015: 18th International Conference, Munich, Germany, October 5-9, 2015, Proceedings, Part III 18 234–241 (Springer, 2015).

Shi, J.-Y. et al. Exploring prognostic indicators in the pathological images of hepatocellular carcinoma based on deep learning. Gut 70, 951–961 (2021).

Saillard, C. et al. Predicting survival after hepatocellular carcinoma resection using deep learning on histological slides. Hepatology 72, 2000–2013 (2020).

Huang, Z., Bianchi, F., Yuksekgonul, M., Montine, T. J. & Zou, J. A visual–language foundation model for pathology image analysis using medical twitter. Nat. Med. 29, 2307–2316 (2023).

Lu, M. Y. et al. A visual-language foundation model for computational pathology. Nat. Med. 30, 863–874 (2024).

Chen, R. J. et al. Towards a general-purpose foundation model for computational pathology. Nat. Med. 30, 850–862 (2024).

Zhang, H., Zhao, T., King, I. & Lyu, M. R. In IJCAI 3938-3944 (New York, NY, USA, 2016).

Liu, S. & Wu, X. Research on Emergence of Collective Behavior for Information Dissemination in Complex Networks. IEEE Transactions on Computational Social Systems (2024).

Wang, S. & Lee, D. Community cohesion looseness in gene networks reveals individualized drug targets and resistance. Brief. Bioinforma. 25, bbae175 (2024).

Wen, X.-Z., Zheng, Y., Du, W.-L. & Ren, Z.-M. Regulating clustering and assortativity affects node centrality in complex networks. Chaos, Solitons Fractals 166, 112880 (2023).

Liu, J., Zhu, F. & Wei, J. Network constraint and online group innovation: a dual perspective of inter-community group network and intra-community group network. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 124, 1902–1939 (2024).

Chakraborty, T., Dalmia, A., Mukherjee, A. & Ganguly, N. Metrics for community analysis: A survey. ACM Comput. Surv. (CSUR) 50, 1–37 (2017).

Gunduz, C., Yener, B. & Gultekin, S. H. The cell graphs of cancer. Bioinformatics 20, i145–i151 (2004).

Sharma, H. et al. In Medical Imaging 2016: Digital Pathology, Vol. 9791 238–256 (SPIE, 2016).

Zhou, Y. et al. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision workshops 0-0 (2019).

Wu, Z. et al. Graph deep learning for the characterization of tumour microenvironments from spatial protein profiles in tissue specimens. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 6, 1435–1448 (2022).

Pati, P. et al. in Uncertainty for Safe Utilization of Machine Learning in Medical Imaging, and Graphs in Biomedical Image Analysis: Second International Workshop, UNSURE 2020, and Third International Workshop, GRAIL 2020, Held in Conjunction with MICCAI 2020, Lima, Peru, October 8, 2020, Proceedings 2 208–219 (Springer, 2020).

Pati, P. et al. Hierarchical graph representations in digital pathology. Med. Image Anal. 75, 102264 (2022).

Jaume, G. et al. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition 8106–8116 (2021).

Jaume, G. et al. In ICML 2020 Workshop on Computational Biology 1–5 (2020).

Li, K., Wu, Z., Peng, K.-C., Ernst, J. & Fu, Y. In Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition 9215–9223 (2018).

Mohankumar, A. K. et al. In Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics 4206–4216 (2020).

You, J., Gomes-Selman, J. M., Ying, R. & Leskovec, J. In Proceedings of the AAAI conference on artificial intelligence, Vol. 35 10737–10745 (2021).

Chen, R. J. et al. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 16144–16155 (2022).

Ranftl, R., Bochkovskiy, A. & Koltun, V. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision 12179–12188 (2021).

Shen, Y. et al. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Vol. 36 2207–2215 (2022).

Xu, H. et al. Vision transformers for computational histopathology. IEEE Reviews in Biomedical Engineering (2023).

Liu, B., Yuan, Y., Pan, X., Shen, H.-B. & Jin, C. AttSiOff: a self-attention-based approach on siRNA design with inhibition and off-target effect prediction. Med-X 2, 5 (2024).

Li, R., Yao, J., Zhu, X., Li, Y. & Huang, J. In International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention 174–182 (Springer, 2018).

Chen, R. J. et al. In Medical Image Computing and Computer Assisted Intervention–MICCAI 2021: 24th International Conference, Strasbourg, France, September 27–October 1, 2021, Proceedings, Part VIII 24 339–349 (Springer, 2021).

Lee, Y. et al. Derivation of prognostic contextual histopathological features from whole-slide images of tumours via graph deep learning. Nature Biomedical Engineering, 1–15 (2022).

Bankhead, P. et al. QuPath: Open source software for digital pathology image analysis. Sci. Rep. 7, 1–7 (2017).

Zhao, L. & Akoglu, L. In International Conference on Learning Representations (2020).

Di, D. et al. Generating hypergraph-based high-order representations of whole-slide histopathological images for survival prediction. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 45, 5800–5815 (2022).

Feng, Y., You, H., Zhang, Z., Ji, R. & Gao, Y. In Proceedings of the AAAI conference on artificial intelligence, Vol. 33 3558-3565 (2019).

Velickovic, P. et al. Graph attention networks. Stat 1050, 10–48550 (2017).

Winter, R., Noé, F. & Clevert, D.-A. Permutation-invariant variational autoencoder for graph-level representation learning. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 34, 9559–9573 (2021).

Kipf, T. N. & Welling, M. In International Conference on Learning Representations (2017).

Xu, K., Hu, W., Leskovec, J. & Jegelka, S. In International Conference on Learning Representations (2019).

Liu, M., Gao, H. & Ji, S. In Proceedings of the 26th ACM SIGKDD international conference on knowledge discovery & data mining 338–348 (2020).

Scholzen, T. & Gerdes, J. The Ki‐67 protein: from the known and the unknown. J. Cell. Physiol. 182, 311–322 (2000).

Garrido, A. & Djouder, N. Cirrhosis: a questioned risk factor for hepatocellular carcinoma. Trends Cancer 7, 29–36 (2021).

Chen, C., Wang, Z., Ding, Y. & Qin, Y. Tumor microenvironment-mediated immune evasion in hepatocellular carcinoma. Front. Immunol. 14, 1133308 (2023).

Zeng, Y. et al. Guiding irregular nuclear morphology on nanopillar arrays for malignancy differentiation in tumor cells. Nano Lett. 22, 7724–7733 (2022).

Murai, H. et al. Multiomics identifies the link between intratumor steatosis and the exhausted tumor immune microenvironment in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 77, 77–91 (2023).

Zheng, C. et al. Landscape of infiltrating T cells in liver cancer revealed by single-cell sequencing. Cell 169, 1342–1356. e1316 (2017).

Suh, S. W. & Choi, Y. S. Influence of liver fibrosis on prognosis after surgical resection for resectable single hepatocellular carcinoma. ANZ J. Surg. 89, 211–215 (2019).

Fattovich, G., Stroffolini, T., Zagni, I. & Donato, F. Hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhosis: incidence and risk factors. Gastroenterology 127, S35–S50 (2004).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China [grant number 2022YFB4702702], the Science and Technology Program of Shinan District of Qingdao City [grant number 2022-4-006-YY], Qingdao Excellent Medical and Health Discipline Leader Training Program (2022), and the Joint Guidance Project of the Qiqihar City Science and Technology Program [grant number LHYD-202016]. Thanks to five clinical institutions: Shinan, Laoshan, West Coast, Shibei, and Pingdu in Qingdao, China, for providing data and annotations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: Y.Y., Z.Z., and C.J.; Methodology: Y.Y., X.F., H.Y., W.Z., M.X.; Software: Y.Y., and X.F.; Validation, Y.Y., Z.Z., S.L., W.Z., B.X., and Y.C.; Formal Analysis, Y.Z., Y.Y., Z.Z., M.X., and Q.G.; Resources, M.L., B.H., and C.J.; Data Curation, M.L., Q.G., Y.Y., X.F., C.W., and Q.Z.; Writing – Original Draft, Y.Y., Z.Z.; Writing – Review & Editing, X.F., R.J., H.Y., C.J.; Supervision, M.L., B.H., and C.J.; Project Administration, M.L., B.H., and C.J.; Funding Acquisition, M.L., B.H., and C.J.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yuan, Y., Zhao, Z., Fang, X. et al. Cell graph analysis in hepatocellular carcinoma: predicting local recurrence and identifying spatial relationship biomarkers. npj Precis. Onc. 9, 261 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41698-025-01042-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41698-025-01042-0