Abstract

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) have transformed cancer care but are frequently associated with immune-related adverse events (irAEs), complicating treatment. This retrospective cohort study analyzed 9193 adult patients from the OneFlorida+ Clinical Research Network who received ICIs between 2018 and 2022, aiming to identify risk factors for irAEs and evaluate their incidence, severity, and clinical impact. Among the 6,526 patients included in the final analysis, 56.2% developed irAEs within 1 year, including 284 hospitalized cases. Multivariable logistic regression revealed that younger age (18–29), female sex, and comorbidities such as myocardial infarction, heart failure, and renal disease increased irAE risk, while dementia and recent chemotherapy were associated with lower risk. Patients receiving CTLA-4 + PD(L)1 combination therapy had a 35% higher risk of irAEs than those treated with PD-1 inhibitors alone. Breast and hematologic cancers conferred elevated risk, whereas brain cancer was linked to reduced risk. Kaplan–Meier and cumulative incidence analyses demonstrated that irAE severity significantly impacted time to onset (P = 0.038), and overall survival was worse in patients who developed irAEs (P < 0.0001). Treatment regimen influenced irAE-free survival in multi-site cancers and overall survival in kidney cancer, highlighting the need for tailored irAE risk stratification.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) have revolutionized cancer treatment, offering unprecedented improvements in patient outcomes across a wide range of malignancies1. In particular, ICIs have significantly enhanced survival outcomes, particularly for patients with previously incurable conditions such as advanced-stage non-small cell lung cancer, melanoma, and several other cancers2,3,4,5,6,7. Today, nearly half of all patients with metastatic cancer in high-income countries are treated with ICIs8. Currently approved ICIs by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) include those that target the programmed death (PD)-1, PD-L1, and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4) pathways, which are crucial in maintaining the immune system’s balance between attacking foreign pathogens and preserving normal tissue. PD-L1, a protein expressed on target cells, binds to PD-1 receptors on CD8 T cells to limit inflammation and protect healthy tissue9. However, many tumors express PD-L1 to inhibit T-cell function and evade immune surveillance. ICIs targeting PD-1 or PD-L1 disrupt this immune escape mechanism, allowing cytotoxic CD8 T cells to destroy tumor cells more effectively. CTLA-4, on the other hand, primarily functions during the early T-cell priming phase by competing with CD28 for binding to B7 molecules (CD80/CD86) on antigen-presenting cells (APCs)10. While CD28-B7 interaction promotes T-cell activation, CTLA-4 delivers inhibitory signals that suppress T-cell proliferation11. Blocking CTLA-4 shifts this balance toward activation, enhancing T-cell priming and clonal expansion in lymphoid tissues12,13,14. In contrast to PD-1/PD-L1 blockade, which acts at the effector phase in peripheral tissues, CTLA-4 inhibition boosts the initiation of the antitumor immune response.

While ICIs have brought transformative therapeutic benefits, their use has also introduced a new spectrum of side effects known as immune-related adverse events (irAEs), which pose significant challenges in clinical management15. Unlike conventional chemotherapy toxicities, irAEs are distinct in their resemblance to autoimmune conditions, yet they follow different natural courses than traditional autoimmune diseases16. These adverse events can affect almost any organ system, with the skin, gastrointestinal tract, liver, and endocrine glands being the most commonly involved17,18,19. The severity of irAEs can range considerably, from mild, self-resolving conditions to severe, potentially life-threatening complications20,21. The emergence of irAEs necessitates a paradigm shift in clinical practice, requiring oncologists to adopt a more nuanced approach to patient care. Given the complexity and unpredictability of irAEs, clinicians need to monitor these toxicities, ensuring early detection, and implementing timely interventions22. Failure to manage irAEs effectively can significantly compromise patients’ quality of life and diminish the overall benefits of ICI therapy23.

Despite the increasing use of ICIs across various cancer types, a significant gap remains in the literature regarding the systematic investigation of risk factors that predispose certain patients to develop irAEs, as well as the clinical outcomes associated with these events. Such a knowledge gap limits our ability to effectively predict, diagnose, and manage irAEs. Moreover, a lack of comprehensive studies examining the long-term impact of irAEs on treatment efficacy and patient survival further emphasizes the need for more in-depth research in this area. Several studies have explored different aspects of irAEs associated with ICI therapy, contributing insights while also highlighting the complexity of this emerging field. For instance, Remon et al. focused on irAEs in thoracic malignancies, particularly in non-small cell lung cancer, emphasizing the challenges in managing these events24. Valpione et al. identified clinical features and blood biomarkers, such as interleukin-6, as prognostic factors for autoimmune toxicity following anti-CTLA-4 therapy25. Eun et al. highlighted risk factors for irAEs associated with pembrolizumab, emphasizing the need for a deeper understanding of these factors26. Specific adverse events have also been documented, such as severe neutropenia induced by pembrolizumab, reported by Barbacki et al., which underscores the need to recognize rare but severe irAEs27. Delaunay et al. discussed the management of pulmonary toxicity associated with ICIs, underscoring the critical need for specialized approaches28. Chitturi et al. evaluated cardiovascular events linked to ICIs in lung cancer patients, highlighting the importance of understanding and managing cardiovascular risks associated with ICI therapy29.

While these studies have contributed to our understanding of the diversity of irAEs, they also have notable limitations that need further investigation. Those existing studies are mainly case reports or small cohort studies, which, while insightful, lack the robustness and generalizability to inform clinical practice on a larger scale. On the other hand, systematic reviews and meta-analyses30,31,32 often aggregate data from heterogeneous studies with varying methodologies, leading to conclusions that may lack precision and context. This issue is compounded by the fact that most studies focus on specific cancer types or ICI therapies, limiting their applicability across diverse patient populations. In this study, we aim to address these limitations by conducting a large-scale, systematic investigation of patients who develop irAEs during ICI therapy in a real-world data set. We included different irAE events and cancer types, providing a comprehensive analysis that is both clinically relevant and widely applicable. By identifying key risk factors associated with irAE, our study will contribute to the development of predictive models that can enhance personalized medicine approaches in oncology.

Results

Cohort collection

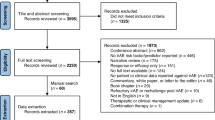

The study cohort was drawn from the OneFlorida+, comprising 16,936 patients undergoing ICI treatment. 7743 patients were excluded due to the presence of pre-existing immune-related conditions, resulting in a final eligible cohort of 9193 patients. Within this cohort, 3665 patients developed irAEs within 1 year of ICI treatment, while the remaining 5528 were classified as non-irAE patients. To ensure adequate follow-up, the non-irAE group was further restricted to individuals with a documented follow-up visit at least 1 year after ICI treatment, resulting in a refined non-irAE group of 2861 patients. Consequently, the final analysis included a total of 6526 patients, with an overall irAE incidence rate of 56.2% in the study population. The selection and exclusion process for the final cohort is detailed in Fig. 1.

This flowchart outlines the selection process for patients receiving immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) therapy in the OneFlorida+ database. Of 16,936 patients identified, 7743 were excluded due to having immune-related condition ICD codes prior to ICI initiation. Among the remaining patients, 5528 did not develop an immune-related adverse event (irAE) within 1 year of ICI treatment, and 3665 developed at least one irAE. An additional 2667 patients without irAEs were excluded due to the absence of encounter visits beyond 1 year following ICI initiation, resulting in 2861 patients in the final non-irAE cohort.

Basic characteristics

In this study cohort, we collected data on 6526 patients who received immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), of whom 3665 experienced irAEs, and 284 had serious irAEs (Table 1). Among the patients who developed irAEs, 58.3% were male, compared to 61.7% in the non-irAE group, indicating a slightly higher incidence of irAEs among females. The age distribution of the entire cohort was skewed towards older adults, with 88.3% of patients being over 50 years old. Regarding race, most patients were White (84.8%), followed by African Americans (12.4%). Hispanic ethnicity was less prevalent, with 5.6% of the irAE group identifying as Hispanic, compared to 7.1% in the non-irAE group. Individuals with a history of smoking had a higher incidence of irAEs (7.0%) and serious irAEs (6.3%) compared to those who never smoked (‘Never’), who had a lower incidence of irAEs (5.9%) and serious irAEs (2.1%), suggesting a potential link between smoking and the development of irAEs. 4.3% of irAE patients were classified as underweight, compared to 3.6% in the non-irAE group. The distribution of patients across other BMI categories (normal, overweight, obesity, morbid obesity) was comparable between the irAE and non-irAE groups.

In terms of comorbidities, myocardial infarction was observed in 7.7% of irAE patients compared to 3.5% in the non-irAE group, with a significant difference (P < 0.001). Congestive heart failure also showed a significant difference, with 9.4% in the irAE group versus 4.6% in the non-irAE group (P < 0.001). Liver disease was prevalent in 29.2% of irAE patients and 27.1% of non-irAE patients, with a P-value of 0.058, indicating a trend towards significance. Renal disease showed a significant difference, with 16.3% in the irAE group versus 12.0% in the non-irAE group (P < 0.001). Further analysis of cancer types revealed that, aside from multi-site cancers, melanoma was the most prevalent, occurring in 26.0% of patients who experienced irAEs, compared to 20.3% in those who did not. Among those 744 irAE melanoma patients, 557 patients received anti-PD-1 therapies while 149 were treated with anti-CTLA4-anti-PD(L)1. Less common cancer types have been grouped under ‘Other Cancers,’ with additional details provided in Supplementary Table 2.

We further explored the 3665 irAE patients based on the specific organs affected, as shown in Supplementary Table 3. Multi-site irAEs were the most common, affecting 1638 patients (44.7%), followed by gastrointestinal irAEs in 927 patients (25.3%) and neurologic irAEs in 258 patients (7.0%). Hematologic irAEs were observed in 192 patients (5.2%), while renal and respiratory irAEs affected 172 (4.7%) and 167 (4.6%) patients, respectively. Interestingly, over 70% of patients with cardiac, renal, and respiratory irAEs were male. Comorbidities played a significant role in the development of organ-specific irAEs. For instance, 25.3% of patients with cardiac irAEs had a history of myocardial infarction, and 25.3% also had liver disease, while 30.3% of these patients had diabetes. Patients with a history of liver disease accounted for 29.2% of those with hematologic irAEs and 42.2% of those with hepatic irAEs. Additionally, 42.3% of patients with reproductive irAEs had liver disease, highlighting its significant contribution to specific irAE types. Furthermore, 27.3% of patients with renal irAEs had diabetes, and chronic pulmonary disease was present in 45.5% of those with respiratory irAEs, suggesting that pre-existing conditions may predispose patients to organ-specific irAEs. Cancer type and the type of ICI therapy played crucial roles in determining the organ involvement in irAEs. In melanoma patients, endocrine irAEs were notably more common among those treated with PD-1 inhibitors (33.6%) compared to those receiving PD-L1 therapies (0.84%), with a statistically significant difference (p = 0.00739). Similarly, kidney cancer patients treated with PD-1 inhibitors exhibited a significantly higher incidence of multi-site irAEs (43.0%) than those treated with PD-L1 therapies (3.56%, p = 2.55e-26). Conversely, hematologic irAEs were more frequent in patients treated with anti-PD-L1 therapies, particularly among those with non-melanoma skin cancer, suggesting potential therapy-specific risks for blood-related irAEs in this population. These findings underscore the importance of considering both cancer type and ICI therapy when managing irAE risk, as different checkpoint inhibitors may provoke distinct immune responses that impact organ systems variably across cancer types.

We expanded the irAE data from an individual-level to an event-based format, as presented in Supplementary Table 4. In total, we observed 6288 discrete irAE events among the 3665 patients in the irAE group, with some patients experiencing up to nine different organ system toxicities. The most commonly systems were endocrine (2028 events; 32.2%), neurologic (743; 11.8%), renal (733; 11.7%), and hematologic (726; 11.6%). This is consistent with prior literature reporting endocrine toxicities in up to 30% of patients treated with ICIs33, neurologic irAEs in 3–12%34, renal dysfunction in 5–15%35, and hematologic abnormalities in 5–15%36. Beyond estimating incidence, we further explored the clinical context in which specific organ toxicities occurred. In the cardiac irAE group, pre-existing cardiovascular comorbidities were highly prevalent: 31.0% of patients had a history of myocardial infarction, 31.9% had congestive heart failure, and 22.3% had cerebrovascular disease. These findings reinforce the importance of comprehensive cardiovascular risk assessment and early cardiology involvement when initiating ICI therapy in patients with known cardiac conditions. In the renal irAE group, 40.4% of patients had a prior diagnosis of renal disease, and 30.6% had diabetes, both of which are established risk factors for immune-mediated nephritis. These rates were among the highest across all irAE subtypes, suggesting that impaired renal reserve and underlying metabolic dysfunction may increase vulnerability to renal immune toxicity. Among patients with hematologic irAEs, 40.4% had documented liver disease, a proportion notably high and closely comparable to the 51.6% observed in the hepatic irAE group. This shared enrichment suggests that underlying hepatic dysfunction, including cirrhosis, hepatic metastases, or other chronic liver conditions, may contribute to increased susceptibility to both hematologic and hepatic immune-related toxicities following ICI treatment. These findings indicate that the development of irAEs is influenced not only by immune activation but also by pre-existing organ pathology and limited physiological reserve, both of which may increase tissue vulnerability during immune checkpoint blockade. To further elucidate the complexity of systemic immune-related toxicity, we investigated patterns of co-occurring irAEs (1638 patients) in patients with multi-organ involvement. Notably, the most frequent combinations were endocrine plus neurologic (119 individuals), endocrine plus renal (110 individuals), and cardiac plus endocrine (91 individuals) irAEs. These patterns likely reflect shared immunopathogenic pathways. The clustering of cardiac and endocrine toxicities, in particular, has been highlighted in prior case series19,37,38 as a high-risk constellation associated with serious outcomes, including myocarditis and adrenal insufficiency. Understanding these co-occurrence patterns has important implications for clinical monitoring, as the appearance of one irAE may signal increased risk for others, warranting broader surveillance and coordinated care across specialties.

Risk factors for immune-related adverse events in ICI therapy

We first investigated associations between patient demographics and the development of irAEs within 1 year of receiving ICIs. As illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 2, female patients exhibited higher risks of developing irAEs compared to male patients (OR: 1.17, 95% CI: 1.06–1.30, P-value = 0.002). Age was also a significant factor; younger patients (18−29 years) demonstrated a markedly higher risk (OR: 2.04, 95% CI: 1.26–3.40, P-value = 0.005) relative to those aged 65 and above. Hispanic ethnicity was associated with a decreased risk of irAEs (OR: 0.88, 95% CI: 0.79–1.00, P-value = 0.043). Additionally, smoking status affected the incidence of irAEs, with ever smokers exhibiting a higher risk than never smokers (OR: 1.90, 95% CI: 1.42-2.54, P-value < 0.001). Patients classified as underweight had the highest risk of developing irAEs compared to the normal BMI group with an OR of 1.25 (95% CI: 0.96–1.64; P-value = 0.099). This was followed by patients with obesity, who had an OR of 1.05 (95% CI: 0.90–1.22; P-value = 0.537), and those who were overweight, with an OR of 1.02 (95% CI: 0.91–1.16; P-value = 0.696). In contrast, morbid obesity was associated with a reduced risk of irAEs (OR: 0.83; 95% CI: 0.69–1.01; P-value = 0.061).

We incorporated comorbidity data into the logistic regression analysis, to further explore health conditions on the risk of developing irAEs (Supplementary Fig. 3). Notably, patients with a history of myocardial infarction had a 73% increased risk of irAEs (OR: 1.73, 95% CI: 1.35–2.23, P-value < 0.001), while those with congestive heart failure showed a similarly elevated risk (OR: 1.74, 95% CI: 1.40–2.17, P-value < 0.001). Renal disease also emerged as a significant predictor, associated with a 35% higher risk of irAEs (OR: 1.35, 95% CI: 1.16–1.57, P-value < 0.001). Conversely, certain conditions were linked to a reduced risk of irAEs. For example, patients with dementia were found to have a 45% lower risk of developing irAEs (OR: 0.55, 95% CI: 0.36–0.84, P-value = 0.006). Additionally, the type of ICI treatment administered played a critical role in the development of irAEs (Supplementary Fig. 4). Patients treated with a combination of CTLA4 and PD-1 inhibitors exhibited a 35% higher risk of irAEs (OR: 1.35, 95% CI: 1.14–1.60, P-value < 0.001), compared to those treated with PD-1 inhibitors alone. Similarly, patients receiving PD-L1 inhibitors also showed an increased risk, with a 28% higher risk of irAEs (OR: 1.28, 95% CI: 1.09–1.50, P-value = 0.002).

As illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 5, cancer type significantly modulated the risk of developing irAEs among patients undergoing ICI therapy. Compared to melanoma, which served as the reference group, several cancer types were associated with a substantially higher risk of irAEs. Patients with breast cancer had more than double the risk (OR: 2.36, 95% CI: 1.57–3.60, P-value < 0.001), while those with secondary malignant neoplasms exhibited an even higher risk, with nearly a threefold increase (OR: 2.92, 95% CI: 1.69–5.27, P-value < 0.001). Similarly, hematological cancer was associated with a more than two-and-a-half-fold increase in risk (OR: 2.61, 95% CI: 1.40–5.14, P-value = 0.004). In contrast, patients with brain cancers demonstrated a significantly reduced risk of developing irAEs (OR: 0.55, 95% CI: 0.32–0.92, P-value = 0.025). This reduced risk may be explained by the high mortality rate in this population, potentially limiting the time for irAEs to manifest. However, other factors, such as differences in immune response or treatment protocols, may also contribute to this observation. To eliminate the potential impact of gender on specific irAEs, we excluded all patients who experienced reproductive irAEs (all of whom were female). We found that the results remained consistent with those obtained without this exclusion, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 6. In addition to cancer type, the timing of chemotherapy relative to ICI initiation also influenced irAE risk. Receipt of chemotherapy within 30 days before or after ICI initiation was independently associated with a significantly lower likelihood of developing irAEs (OR: 0.68; 95% CI: 0.60–0.76; P < 0.001), as illustrated in Fig. 2. This inverse association may reflect the immunosuppressive effects of cytotoxic chemotherapy, which could attenuate the immune activation necessary for irAE development.

This forest plot displays adjusted odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for factors associated with the development of irAEs within 1 year of ICI initiation. The analysis includes demographic characteristics (e.g., age, sex, race/ethnicity), comorbidities, ICI regimen types (anti-PD1, anti-PDL1, anti-CTLA4, and combination therapies), and primary cancer types. Significant associations (p < 0.05) are indicated, with odds ratios plotted on a logarithmic scale. The vertical line represents the null value (OR = 1.0). Asterisks denote statistical significance (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001).

Survival Analysis for irAE free and overall survival

We examined the time to irAE event and overall survival probabilities across different patient groups, stratified by irAE severity and treatment regimens (Anti-CTLA4 + Anti-PD(L)1, Anti-PD-1, and Anti-PDL1). As shown in Fig. 3A, irAE-free survival differed significantly between patients who experienced serious irAEs (n = 284) and those with non-serious irAEs (n = 3381), with a shorter median irAE-free duration in the serious irAE group (70 days) compared to the non-serious group (89 days; log-rank P = 0.038). In subgroup analysis of patients with multi-site cancer (Fig. 3B), irAE-free survival also varied significantly by ICI regimen (P = 0.02). Median time to irAE onset was shortest among those receiving combination Anti–CTLA-4 + Anti–PD(L)1 therapy (n = 185; 128 days), followed by Anti–PDL1 (n = 498; 136 days) and Anti–PD-1 (n = 2342; 163 days). In contrast, treatment regimen was not significantly associated with irAE-free survival among melanoma patients (P = 0.10; Supplementary Fig. 7A) or kidney cancer patients (P = 0.14; Supplementary Fig. 7B). For melanoma, median irAE-free durations ranged from 142 days for combination therapy (n = 252) to 217 days (Anti–PD1, n = 1168) and 203 days (Anti–PDL1, n = 69). Similarly, in kidney cancer, median irAE-free durations were 135 days (combination; n = 197), 147 days (Anti–PD1; n = 586), and 284 days (Anti–PDL1; n = 42). While trends favored longer irAE-free intervals with monotherapy, differences did not reach statistical significance, suggesting a more limited influence of regimen on irAE timing in these tumor types.

P-values were calculated using the log-rank test. A irAE-free survival curves comparing patients who developed non-serious vs. serious irAEs. Patients with serious irAEs experienced earlier onset and significantly reduced irAE-free survival (p = 0.038). B irAE-free survival among patients with multi-site cancer, stratified by ICI regimen: Anti-CTLA4 + Anti-PD(L)1, Anti-PD1, and Anti-PDL1. Patients receiving dual ICI therapy showed earlier irAE onset and lower irAE-free survival (p = 0.02). C Overall survival curves incorporating irAE status as a time-varying covariate over a 5 year follow-up. Patients who developed irAEs had significantly better overall survival compared to those who did not (p < 0.0001). D Overall survival in kidney cancer patients, stratified by ICI regimen. Dual ICI therapy was associated with significantly better survival compared to monotherapy (p = 0.0011).

Figure 3C displays overall survival curves stratified by irAE status using a time-varying covariate approach over a 5 year follow-up period. At baseline, 6383 patients were irAE-free, while 143 had already developed an irAE. Patients who developed an irAE over the course of follow-up experienced significantly worse overall survival compared to those who remained irAE-free, with early and persistent separation of the survival curves (log-rank P < 0.0001). To formally assess this association, we fit a Cox proportional hazards model with time-varying exposure to irAE status. The analysis revealed a substantially increased risk of death following irAE onset (HR = 19.28; 95% CI: 13.57–27.39; P < 2e–16), corresponding to a 19-fold elevation in mortality hazard among patients after experiencing an irAE. The model showed good discriminatory ability (concordance = 0.588), and the association was statistically significant across likelihood ratio, Wald, and score tests (all P < 2e–16). Finally, Fig. 3D illustrates overall survival among kidney cancer patients by ICI regimen. Here, a statistically significant difference was observed (log-rank P = 0.0011), with patients receiving combination therapy (n = 197) demonstrating inferior survival relative to those treated with Anti–PD-1 (n = 586) or Anti–PD-L1 (n = 42). The median survival time was notably shorter in the combination group, possibly reflecting higher baseline disease burden or increased toxicity-related mortality. These results underscore the need to balance efficacy and tolerability in regimen selection for renal cell carcinoma, particularly given the complexity of immune-related toxicity in this population.

To further understand the dynamics of irAE onset, we examined the cumulative incidence of irAEs stratified by cancer type and severity. Supplementary Fig. 7E shows that patients with serious irAEs had significantly higher cumulative incidence rates over time compared to those with mild irAEs (P = 0.0175). This supports the observation that serious irAEs occur earlier and at a higher rate during ICI therapy, underscoring the importance of proactive monitoring and early intervention for high-risk patients. Additionally, cumulative incidence curves stratified by cancer type (Supplementary Fig. 7F) provide insights into the role of cancer burden in irAE development. Patients with multi-site cancers demonstrated a notably higher cumulative incidence of irAEs compared to melanoma patients, with the difference being highly significant (P = 0.0000546). This suggests that patients with multi-site cancers are more susceptible to irAEs, potentially due to the broader immune activation associated with multiple tumor sites. The steeper rise in the cumulative incidence curve for multi-site cancer patients indicates that irAEs develop more rapidly and at a higher frequency in this group. These findings emphasize the need for closer clinical surveillance and tailored management strategies for patients with extensive cancer involvement to mitigate the risks of irAEs.

Discussion

This study provided a comprehensive analysis of irAE risk factors in patients receiving ICI therapy. Our analyses encompassed patient demographics, comorbidities, cancer types, and ICI treatment regimens. First, we identified that female patients were at higher risk for irAEs, possibly due to hormonal differences and genetic factors that enhance immune activation39,40. Similarly, younger patients also exhibited higher irAE rates, suggesting that immune anergy, or the reduction in immune reactivity, may develop with age, thereby lowering irAE susceptibility in older individuals. Our study further observed that certain comorbidities, such as cardiovascular conditions, significantly influence irAE risk. For instance, patients with a history of myocardial infarction or congestive heart failure were more likely to develop irAEs. This finding aligned with earlier research suggesting that pre-existing cardiovascular conditions can exacerbate immune responses during ICI treatment, potentially increasing inflammation and irAE risks41,42,43. In contrast, an intriguing finding from our study was the reduced risk of irAEs in patients with dementia. While the underlying mechanisms remained unclear, this observation may suggest chronic immunosuppression or altered immune signaling in dementia patients, reducing susceptibility to irAEs. Alternatively, it is possible that irAEs are underreported or masked in dementia patients due to overlapping symptoms with the disease itself or diagnostic challenges. Further research is needed to unravel the complex interplay between neuroinflammation, immune checkpoint inhibition, and irAE risk in this population. An additional finding of interest was the reduced likelihood of irAE development among patients who received chemotherapy within 30 days before or after ICI initiation. This inverse association may reflect the immunosuppressive properties of cytotoxic agents, which could dampen immune activation and reduce the likelihood of off-target immune effects that give rise to irAEs. This finding aligns with prior observations44 suggesting that chemotherapy may transiently mitigate immune-related toxicity, though the extent to which this represents a true biological effect versus ascertainment bias remains uncertain. Further prospective studies are warranted to investigate how treatment sequencing and timing influence immune tolerance and toxicity risk, with the goal of optimizing therapeutic strategies to balance efficacy and safety.

Our findings also revealed that the type of ICI therapy significantly influences irAE risk. Patients receiving combined CTLA4+PD(L)-1 inhibitors showed a higher incidence of irAEs compared to those treated with PD-1 or PD-L1 inhibitors alone. This finding aligned with existing literature16,45, which has consistently reported increased toxicity with combination therapies due to the synergistic effects of dual immune checkpoint blockade46. Additionally, cancer type significantly modulated the risk and type of irAEs. Specifically, patients with hematological cancers and breast cancers exhibited a substantially higher risk of irAEs compared to those with melanoma. Prior studies have suggested similar trends, particularly for hematological malignancies, where the immune system is inherently more involved, making these patients more susceptible to irAEs47,48. Furthermore, our study identified distinct associations between irAE status, cancer type, and ICI regimen. Patients who developed irAEs had significantly worse overall survival compared to those who remained irAE-free, suggesting that irAE onset, regardless of severity, may signal heightened vulnerability or disease progression. The time-varying survival analysis further confirmed this finding, showing a substantially increased mortality risk following irAE onset. In stratified analyses, the influence of ICI regimen on survival outcomes varied by cancer type. Among patients with multi-site cancers, ICI regimen significantly impacted irAE-free survival but did not affect overall survival. In contrast, for kidney cancer patients, ICI regimen influenced overall survival but had minimal impact on irAE-free survival. These findings underscore the context-dependent nature of ICI effects and irAE implications, highlighting the need for cancer-specific strategies to balance efficacy and toxicity in ICI therapies.

While our study provided valuable insights, several limitations must be acknowledged. A key limitation of this study is that irAEs were analyzed as binary outcomes, and we were unable to stratify by clinical severity grade (e.g., CTCAE grades 1–5) due to data constraints. Future studies incorporating unstructured clinical notes or clinician-adjudicated chart review would allow more precise grading of irAEs and may clarify the contribution of high-grade toxicities to overall mortality. In addition, our operational definition of “serious irAEs” was based on the occurrence of an irAE diagnosis followed by hospitalization within 30 days of ICI initiation. However, due to limitations in structured EHR data, we could not confirm whether these hospitalizations were directly attributable to irAEs. It is possible that some admissions were related to unrelated comorbidities, scheduled treatments, or cancer-related complications rather than immune toxicity. This limitation may have introduced misclassification and should be considered when interpreting the observed associations between serious irAEs and overall survival. Second, the observed associations may be influenced by unmeasured or residual confounding factors, which we could not fully control despite adjusting for several potential confounders such as age, sex, and comorbidities. However, genetic predispositions and lifestyle factors, including diet, physical activity, and environmental exposures, play a critical role in modulating the immune system’s response to ICIs but were not captured in our analysis. Future studies incorporating genetic profiling and detailed lifestyle data are necessary to comprehensively assess these influences. Additionally, the identification of irAEs relied on structured diagnosis codes within the EHR, which are inherently subject to misclassification and reporting bias. For example, mild irAEs such as skin toxicities are often managed in outpatient settings and may be underreported. In contrast, serious events like myocarditis or pneumonitis are more likely to be captured due to their clinical severity and frequent association with hospitalization. Although we restricted our analysis to diagnoses with a status of “Final” or “Discharge” to improve specificity and reduce inclusion of rule-out conditions, the potential for both underestimation and overestimation of certain irAE types remains. Future studies incorporating manual chart review or clinician adjudication would be valuable for enhancing diagnostic accuracy and validating algorithmic identification of irAEs. Finally, our study focused on irAEs occurring within the first year of ICI treatment, which may limit the generalizability of our findings to delayed or late-onset irAEs. While most irAEs emerge within the first few months of therapy, emerging evidence suggests that some clinically significant toxicities may occur beyond the first year. These late onset irAEs were not captured in our analysis due to our predefined follow-up window and may require longer-term surveillance studies to evaluate their incidence, risk factors, and impact on clinical outcomes.

Also, the relatively small sample size in certain subgroups, such as patients with less common cancer types and those receiving specific ICI regimens, may have limited the statistical power of our analyses. This could result in non-significant findings in some areas, such as the irAE-free survival analysis for patients with kidney and multi-site cancers, despite potentially meaningful clinical trends. Larger studies would allow for more robust subgroup analyses and greater confidence in the observed associations. Another important limitation is our inability to differentiate between varying severities of irAEs. Some irAEs are mild and self-limiting, while others are severe, requiring intervention or leading to life-threatening outcomes. Our study treats all irAEs as a homogeneous outcome, which overlooks the nuanced impact that irAE severity may have on patient prognosis and treatment continuation. Future research should focus on stratifying irAEs by severity to provide a more detailed understanding of how different grades of irAEs influence clinical outcomes, therapeutic decisions, and quality of life for patients undergoing ICI therapy.

Methods

Study design

This retrospective cohort study used real-world data from the OneFlorida+ Clinical Research Network49, covering ~17.2 million patients from Miami, Orlando, Tampa, Jacksonville, Tallahassee, Gainesville, and rural areas of Florida50. The OneFlorida+ data encompasses a broad spectrum of patient data, including diagnoses, procedures, observations (e.g., vital signs), prescriptions, and laboratory results. The study focused on adult patients (≥18 years old) who received at least one cycle of FDA-approved ICI therapy, including PD-1 inhibitors (Nivolumab, Pembrolizumab, and Cemiplimab), PD-L1 inhibitors (Atezolizumab, Durvalumab, and Avelumab), and the CTLA-4 inhibitor Ipilimumab. The study period spanned 5 years, from January 1, 2018, to December 31, 2022. To ensure data integrity, patients were excluded if they had missing treatment dates or if death occurred during the treatment period, preventing the completion of at least one ICI cycle. This retrospective multicenter study complied with the Helsinki Declaration and was approved by the Ethics Committees of the University of Florida Institutional Review Board (IRB# 202301615). Due to the retrospective design, informed consent was waived.

Indicator variables

We included data on age at the time of the first ICI treatment, sex, race and ethnicity, smoking status, and body mass index (BMI). BMI categories were defined according to standard thresholds. Participants were classified into five BMI groups: underweight \(({BMI} < 18.5)\), normal \((18.5\le {BMI} < 25)\), overweight \((25\le {BMI} < 30)\), obesity \((30\le {BMI} < 40)\), and morbid obesity \((40\le {BMI})\). Smoking status was defined based on patients’ history. Comorbidities were identified using International Classification of Diseases, Ninth/Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9/10-CM) codes. These comorbidities were recorded as binary variables, indicating the presence or absence of the condition prior to the initiation of ICI. This approach allowed us to standardize the assessment of comorbid conditions across the cohort, ensuring consistency in evaluating the potential impact of pre-existing health conditions on irAE. Primary cancer types were identified using our prior cancer diagnosis algorithms51,52,53. In cases where a patient had multiple cancer types, the diagnosis was categorized under multi-site malignancies51,52,53.

Outcomes

The primary outcome of interest was the occurrence of irAEs following the initiation of ICI therapy. Identification of irAEs was conducted using a predefined algorithm, as depicted in Supplementary Fig. 1. The comprehensive list of adverse events is provided in Supplementary Table 1, and validated against prior studies54. To improve diagnostic reliability, we restricted irAE diagnoses to those with a source classified as “Final” or “Discharge”, which are generally indicative of confirmed diagnoses in ambulatory or inpatient settings. We excluded diagnoses with source labels such as “Admitting,” “Interim,” or “Preliminary” to reduce the inclusion of rule-out or suspected conditions. Patients were categorized into two groups: the irAE group, consisting of those who developed irAEs within 1 year of initiating ICI therapy, and the non-irAE group, which included patients who did not experience irAEs. To minimize the risk of underreporting due to insufficient follow-up, the non-irAE group was further limited to individuals with a documented follow-up visit at least 1 year after their initial treatment. Serious irAEs were defined as cases where patients experienced irAEs and required hospitalization within 1 month of ICI therapy.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize baseline characteristics of the study population, with categorical variables reported as frequencies and percentages. Differences between patients who developed irAEs and those who did not were assessed using Fisher’s exact test, and p-values were calculated to identify statistically significant associations. To evaluate baseline predictors of irAE occurrence, multivariable logistic regression models were constructed. These models adjusted for key covariates, including age group at the initiation of ICI therapy, sex, race and ethnicity, smoking status, primary cancer type, type of ICI regimen, and baseline comorbidities. Adjusted odds ratios (ORs) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were reported to quantify the association between each covariate and irAE risk.

To assess the impact of irAE onset on overall survival, a time-varying Cox proportional hazards model was employed. In this model, irAE status was treated as a time-dependent covariate, switching from 0 to 1 at the time of irAE onset. This allowed patients to contribute person-time both before and after the development of an irAE, enabling a more accurate estimation of the association between irAE occurrence and mortality. Follow-up time was defined from the date of ICI initiation to the date of death or censoring, with administrative censoring at 5 years. Survival curves stratified by time-varying irAE status were estimated with time-split dataset. In parallel, Kaplan–Meier analysis was conducted to estimate irAE-free survival, defined as the duration from the initiation of ICI therapy to the earliest of the following events: onset of the first irAE, death, or last follow-up. Patients who did not develop an irAE were censored at the time of death or last clinical contact. Differences in irAE-free survival distributions across subgroups, such as cancer type, ICI regimen types, and irAE severity (non-serious vs. serious), were assessed using the log-rank test. Because standard Kaplan–Meier estimators treat deaths prior to irAE onset as non-informative censoring, they may overestimate the cumulative incidence of irAEs in the presence of competing risks. To address this limitation, a competing risks analysis was conducted using the Fine-Gray model, which treats death prior to irAE onset as a competing event. Cumulative incidence functions (CIFs) were estimated to describe the probability of irAE occurrence over time, and Gray’s test was used to compare CIFs between subgroups.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to the formal policies and procedures established by the OneFlorida Executive Committee but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Tan, S., Day, D., Nicholls, S. J. & Segelov, E. Immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy in oncology: current uses and future directions: JACC: cardiooncology state-of-the-art review. JACC Cardio Oncol. 4, 579–597 (2022).

Reck, M. et al. Updated analysis of KEYNOTE-024: pembrolizumab versus platinum-based chemotherapy for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer with PD-L1 tumor proportion score of 50% or greater. J. Clin. Oncol. 37, 537–546 (2019).

Hodi, F. S. et al. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab or nivolumab alone versus ipilimumab alone in advanced melanoma (CheckMate 067): 4-year outcomes of a multicentre, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 19, 1480–1492 (2018).

Choueiri, T. K. & Motzer, R. J. Systemic therapy for metastatic renal-cell carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 376, 354–366 (2017).

Vafaei, S. et al. Combination therapy with immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs); a new frontier. Cancer Cell Int. 22, 2 (2022).

Silk, AA-O. et al. Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer (SITC) clinical practice guideline on immunotherapy for the treatment of nonmelanoma skin cancer. J. Immunother Cancer. 10, e004434 (2022).

Pala, L. et al. Outcomes of patients with advanced solid tumors who discontinued immune-checkpoint inhibitors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. EClinicalMedicine. 73, 102681 (2024).

Haslam, A. & Prasad, V. Estimation of the percentage of US patients with cancer who are eligible for and respond to checkpoint inhibitor immunotherapy drugs. JAMA Netw. Open 2, e192535 (2019).

Alsaab, H. O. et al. PD-1 and PD-L1 checkpoint signaling inhibition for cancer immunotherapy: mechanism, combinations, and clinical outcome. Front Pharm. 8, 561 (2017).

Rowshanravan, B., Halliday, N. & Sansom, D. M. CTLA-4: a moving target in immunotherapy. Blood 131, 58–67 (2018).

Chikuma, S., Abbas, A. K. & Bluestone, J. A. B7-independent inhibition of T cells by CTLA-4. J. Immunol. 175, 177–181 (2005).

Owen, D. H. et al. Incidence, risk factors, and effect on survival of immune-related adverse events in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer. Clin. Lung Cancer 19, e893–e900 (2018).

Abu-Sbeih, H. et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitor-induced colitis as a predictor of survival in metastatic melanoma. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 68, 553–561 (2019).

Postow, M. A., Sidlow, R. & Hellmann, M. D. Immune-related adverse events associated with immune checkpoint blockade. N. Engl. J. Med. 378, 158–168 (2018).

von Itzstein, M. S., Gerber, D. E., Bermas, B. L. & Meara, A. Acknowledging and addressing real-world challenges to treating immune-related adverse events. J. Immunother. Cancer 12, e009540 (2024).

Yin, Q. et al. Immune-related adverse events of immune checkpoint inhibitors: a review. Front Immunol. 14, 1167975 (2023).

Connolly, C., Bambhania, K. & Naidoo, J. Immune-related adverse events: a case-based approach. Front Oncol. 9, 530 (2019).

Johnson, D. B., Nebhan, C. A., Moslehi, J. J. & Balko, J. M. Immune-checkpoint inhibitors: long-term implications of toxicity. Nature Reviews. Clin. Oncol. 19, 254–267 (2022).

Schneider, B. J. et al. Management of immune-related adverse events in patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy: asco guideline update. J. Clin. Oncol. 39, 4073–4126 (2021).

Liu, Y.-H. et al. Diagnosis and management of immune related adverse events (irAEs) in cancer immunotherapy. Biomed. Pharmacother. 120, 109437 (2019).

Johnson, D. B., Nebhan, C. A., Moslehi, J. J. & Balko, J. M. Immune-checkpoint inhibitors: long-term implications of toxicity. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 19, 254–267 (2022).

Brahmer, J. R., Lacchetti, C. & Thompson, J. A. Management of immune-related adverse events in patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy: American society of clinical oncology clinical practice guideline summary. J. Oncol. Pr. 14, 247–249 (2018).

Choi, J. & Lee, S. Y. Clinical characteristics and treatment of immune-related adverse events of immune checkpoint inhibitors. Immune Netw. 20, e9 (2020).

Remon, J. et al. Immune-related adverse events with immune checkpoint inhibitors in thoracic malignancies: focusing on non-small cell lung cancer patients. J. Thorac. Dis. 10, S1516–s1533 (2018).

Valpione, S. et al. Sex and interleukin-6 are prognostic factors for autoimmune toxicity following treatment with anti-CTLA4 blockade. J. Transl. Med. 16, 94 (2018).

Eun, Y. et al. Risk factors for immune-related adverse events associated with anti-PD-1 pembrolizumab. Sci. Rep. 9, 14039 (2019).

Barbacki, A., Maliha, P. G., Hudson, M. & Small, D. A case of severe Pembrolizumab-induced neutropenia. Anticancer Drugs 29, 817–819 (2018).

Delaunay, M. et al. Management of pulmonary toxicity associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. Eur. Respir. Rev. 28, 190012 (2019).

Chitturi, K. R. et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitor-related adverse cardiovascular events in patients with lung cancer. JACC CardioOncol 1, 182–192 (2019).

Komatsu, T. et al. Association between the occurrence of immune-related adverse events and survival outcomes in patients with cancer treated with perioperative immune checkpoint inhibitors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Oncol. 22, 102134 (2024).

Zhou, J., Du, Z., Fu, J., Yi, X.-X. Blood cell counts can predict adverse events of immune checkpoint inhibitors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Immunol. 14, 1117447 (2023).

Pasello, G. et al. Immune-related adverse events in patients treated with immunotherapy for locally advanced or metastatic NSCLC in real-world settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Oncol. 14, 1415470 (2024).

Wang, D. Y. et al. Fatal toxic effects associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol. 4, 1721–1728 (2018).

Cuzzubbo, S. et al. Neurological adverse events associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: review of the literature. Eur. J. Cancer 73, 1–8 (2017).

Cortazar, F. B. et al. Clinicopathological features of acute kidney injury associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. Kidney Int 90, 638–647 (2016).

Davis, E. J. et al. Hematologic complications of immune checkpoint inhibitors. Oncologist 24, 584–588 (2019).

Salem, J.-E. et al. Cardiovascular toxicities associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: an observational, retrospective, pharmacovigilance study. Lancet Oncol. 19, 1579–1589 (2018).

Barroso-Sousa, R. et al. Endocrine dysfunction induced by immune checkpoint inhibitors: Practical recommendations for diagnosis and clinical management. Cancer 124, 1111–1121 (2018).

Wang, S., Cowley, L. A., Liu, X. S. Sex differences in cancer immunotherapy efficacy, biomarkers, and therapeutic strategy. Molecules 24, 3214 (2019).

Chin, I. S. et al. Germline genetic variation and predicting immune checkpoint inhibitor induced toxicity. NPJ Genom. Med. 7, 73 (2022).

Li, X. et al. Advances in immune checkpoint inhibitors induced-cardiotoxicity. Front Immunol. 14, 1130438 (2023).

Lee, C. et al. Pre-existing autoimmune disease increases the risk of cardiovascular and noncardiovascular events after immunotherapy. JACC CardioOncol 4, 660–669 (2022).

Luo, L. et al. Risk factors for cardiovascular adverse events from immune checkpoint inhibitors. Front Oncol. 13, 1104888 (2023).

Sharma, A., Jasrotia, S. & Kumar, A. Effects of chemotherapy on the immune system: implications for cancer treatment and patient outcomes. Naunyn Schmiedeberg’s Arch. Pharmacol. 397, 2551–2566 (2024).

Nishino, M. et al. Incidence of programmed cell death 1 inhibitor–related pneumonitis in patients with advanced cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol. 2, 1607–1616 (2016).

Rached, L. et al. Toxicity of immunotherapy combinations with chemotherapy across tumor indications: Current knowledge and practical recommendations. Cancer Treat. Rev. 127, 102751 (2024).

Wang, J. et al. Predictive biomarkers for immune-related adverse events in cancer patients treated with immune-checkpoint inhibitors. BMC Immunol. 25, 8 (2024).

Hayashi-Tanner, Y. et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitor toxicity and associated outcomes in older patients with cancer. J Geriatr. Oncol 13, 1011–1016 (2022).

Shenkman, E. et al. OneFlorida clinical research consortium: linking a clinical and translational science institute with a community-based distributive medical education model. Academic Med. 93, 451–455 (2018).

Hogan, W. R. et al. The OneFlorida data trust: a centralized, translational research data infrastructure of statewide scope. J. Am. Med Inf. Assoc. 29, 686–693 (2022).

Song, Q. et al. Risk and outcome of breakthrough COVID-19 infections in vaccinated patients with cancer: real-world evidence from the national COVID cohort collaborative. J. Clin. Oncol. 40, 1414–1427 (2022).

Sharafeldin, N. et al. Outcomes of COVID-19 in patients with. Cancer.: Rep. Natl. COVID Cohort Collab. (N3C). J. Clin. Oncol. 39, 2232–2246 (2021).

Mitra, A. K. et al. Sample average treatment effect on the treated (SATT) analysis using counterfactual explanation identifies BMT and SARS-CoV-2 vaccination as protective risk factors associated with COVID-19 severity and survival in patients with multiple myeloma. Blood. Cancer J. 13, 180 (2023).

Cathcart-Rake, E. J. et al. A Population-based study of Immunotherapy-related toxicities in lung cancer. Clin. Lung Cancer 21, 421–427.e2 (2020).

Acknowledgements

Q.S. is supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (R35GM151089).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.B. and Q.S. were responsible for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. The study was conceived and designed by J.S., J.B., and Q.S. Y.W. led the acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data, performed the statistical analysis, and co-drafted the manuscript with Q.S. All authors contribute to the review and revision of the manuscript. Q.S. also supervised the study and secured funding.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Y., Guo, Y., Tan, A.C. et al. A real-world cohort study of immune-related adverse events in patients receiving immune checkpoint inhibitors. npj Precis. Onc. 9, 346 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41698-025-01123-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41698-025-01123-0

This article is cited by

-

Risk factors for ICI-induced irAEs

Reactions Weekly (2025)