Abstract

Survival assessment for oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) remains a significant clinical challenge. This study develops novel artificial intelligence (AI) platforms for assessing overall survival in OSCC patients based on 240 whole-slide images from multicenter cohorts. A comprehensive evaluation is conducted on four convolutional neural network architectures under two distinct deep learning (DL) training paradigms: supervised DL with precise annotations (PathS model, c-index = 0.809), and weakly supervised DL using slide-level labels without manual annotations (c-index = 0.707). Gradient-weighted class activation mapping reveals novel AI-based prognostic insights to simultaneously identify tumor cells and tumor-infiltrating immune cells as key predictive features. Additionally, our platform achieved significantly improved accuracy compared to conventional clinical signatures (CS model, c-index = 0.721). Furthermore, the clinical potential is enhanced through the development of a multimodal nomogram combining PathS signatures with CS (c-index = 0.817), representing a substantial advancement in personalized survival assessment for OSCC patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) is among the most common head and neck malignancies worldwide1,2,3. Advances in technology have led to the development of various treatments for OSCC, including surgery, radiation, chemotherapy, and immunotherapy1. However, the 5-year overall survival (OS) rate remains relatively low, at 57.9%4,5. Accurate prognosis prediction is crucial for clinicians to ensure appropriate clinical management to balance the treatment efficacy and potential side effects for patients at different disease stages6. Currently, the Tumor, Lymph Node, Metastasis (TNM) staging system is the primary tool for prognostic assessment in clinical practice7. Molecular biomarkers have also been identified to aid in evaluating OSCC survival8,9,10,11. However, the substantial heterogeneity in phenotypes, genomes, and even living environments among OSCC patients limits their predictive accuracy, personalization, and clinical value12,13,14.

In this context, the emerging field of artificial intelligence (AI) technologies offers promising solutions to address these challenges15,16. AI has evolved significantly since its inception, with machine learning (ML) and its specialized subset deep learning (DL) now playing pivotal roles in transforming and innovating various industries17. DL employs artificial neural networks (ANNs), which are inspired by the human brain’s structure, consisting of interconnected processing nodes (neurons) that facilitate complex information transformation18,19. In biomedicine applications, these capabilities enable more accurate prognostic feature extraction from multimodal data sources, such as pathomics and radiomics datasets. Both data sources could be combined with AI technologies to provide novel methods for survival assessment for patients with cancer. However, while radiomics-based AI offers non-invasive and whole-body assessment capabilities, pathomics-based AI provides superior molecular and cellular resolution, including tumor cells and tumor-infiltrated immune cells (TIICs)20, by training novel AI algorithms with whole slide images (WSIs) scanned from a single digital hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained slide. This offers several practical advantages, including cost-effectiveness, routine clinical practice (as H&E staining represents the diagnostic ‘gold standard’), and reduced infrastructure requirements compared to radiomics approaches that depend on advanced imaging equipment like computed tomography scanners or MRI scanners, thereby facilitating its implementation in regions with varying levels of medical care. Previous studies have demonstrated the predictive efficacy of this AI approach for OS assessment in various cancer types21,22,23. However, in OSCC specifically, while radiomics-based AI has shown gradual development24, the applications of pathomics-based AI remain relatively limited25. Current studies predominantly focus on identifying prognostic markers rather than directly assessing patient outcomes26,27.

Additionally, diverse training paradigms, including supervised DL (SDL), unsupervised learning, weakly supervised DL (WSDL), etc., are widely employed in current biomedical AI development23,28,29,30. These approaches exhibit distinct characteristics and clinical applicability. SDL relies on precisely labeled datasets31. The clinician-annotated labels facilitate precise regions of interest (ROIs) identification, thereby enhancing model accuracy but concomitantly increasing annotation workload32. In contrast to SDL, unsupervised learning operates without labeled data to uncover latent patterns and relationships33, which is currently mostly used for clustering and dimensionality reduction. In clinical imaging, this paradigm has demonstrated utility in anomaly detection for identifying rare pathological features rather than prognosis prediction33. WSDL represents an intermediate solution, using partially or inaccurately labeled datasets, which provides a solution to reduce manual workload, without annotations, and decrease background noise34. However, whether WSDL could achieve the same level of accuracy as SDL remains a problem. Considering these differences revealed, however, reliable comparisons between SDL and WSDL in specific classification or prediction tasks remain limited.

Furthermore, despite the rapid advancement of AI in medical image analysis, the ‘black box’ remains a significant challenge, as the complex interlayer relationships within ANNs are often opaque. This lack of interpretability may introduce undetected biases, potentially influencing clinical decision-making. To address this limitation, explainable AI (XAI) methods, categorized into visual (most prevalent in medical imaging), textual, and example-based approaches, have been developed to enhance model interpretability35. Beyond conventional XAI techniques, recent innovations such as informed deep learning and case-based reasoning have emerged to improve interpretability in oncology applications for clinicians36,37. In this study, we employed Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping (Grad-CAM), a visual explanation technique, to decode the pathomics-based AI platform’s decision-making process. Grad-CAM not only improves model trustworthiness but also highlights the critical role of tumor cells and TIICs in patient outcomes from histopathological insights.

In this retrospective cohort study, we developed, for the first time to the best of our knowledge, a novel AI platform capable of predicting OS in OSCC patients directly from WSIs, with comparative evaluation of two deep learning algorithms. Additionally, the relationship between TIICs and prognosis was elucidated from the perspective of AI-based image analysis. Moreover, we integrated pathomics signatures with clinicopathological parameters (analyzed via Cox regression-based machine learning) into a multimodal prognostic platform, offering a more interpretable and comprehensive tool for OSCC survival assessment for clinicians.

Results

Baseline characteristics of cohorts

The baseline characteristics of the training and validation cohorts are presented in Table 1, including sex, age, lesion site, tobacco use, alcohol consumption, T stage, N stage, clinical stage, pathological grade, and peripheral blood cell counts/associated protein levels. Statistical analysis of these baseline characteristics revealed no significant differences between the two cohorts (P > 0.05), confirming the effectiveness of our randomization strategy in achieving comparable groups. The study workflow and participant inclusion process are illustrated in Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. 1, respectively.

A novel pathomics-based artificial intelligence (AI) platform was developed to assess cancer patient survival through a two-tiered predictive analytics approach, comprising patch-level deep learning (DL) and patient-level prediction. During patch-level DL, four convolutional neural networks were evaluated, and Visual Geometry Group19 (VGG19) was identified as the optimal algorithm according to the area under the curve (AUC) value. The features extracted by VGG19 were integrated into the whole slide image (WSI)-level pathomics signatures through Bag of Words (BoW) and Patch Likelihood Histogram (PLH) methods. These pathomics signatures were further selected by Correlation coefficients and Lasso-Cox regression to conduct the AI model. The Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping (Grad-CAM) was employed to highlight regions within the images that significantly influenced the model’s decision-making process. Two distinct DL algorithms were evaluated: weakly supervised DL (extensive labeling strategy, formed PathWS) and supervised DL (requiring annotations, formed PathS). PathS demonstrated better predictive efficacy according to Kaplan–Meier analysis in validation and external testing cohorts. Additionally, the clinical signature (CS) platform was developed based on clinicopathological parameters identified by Cox regression analysis. Furthermore, the integration of PathS with CS into a multimodal platform represented by a nomogram further enhanced predictive efficacy, suggesting strong potential for clinical application in oral squamous cell carcinoma management. AI artificial intelligence, WSI whole slide image, DenseNet Dense Convolutional Network, ResNet Residual Networks, VGG Visual Geometry Group, WSDL weakly supervised deep learning, SDL supervised deep learning, Grad-CAM Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping, BoW Bag of Words, PLH Patch Likelihood Histogram, PathWS pathomics-based AI platform developed through WSDL, PathS pathomics-based AI platform developed through SDL, c-index concordance index, CS clinical signatures, OS overall survival, AUC area under the curve, CI confidence interval.

Patch-level prediction performance

The prediction performance of the four convolutional neural networks (CNNs) at the patch level is presented in Table 2. Under the WSDL framework, the Visual Geometry Group 19 (VGG19) algorithm demonstrated the highest predictive efficacy in the training cohort [AUC = 0.963, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.963–0.964]. This result underscores its strong capacity to effectively differentiate between classes. However, this performance was not replicated in the validation cohort, where VGG19 exhibited a considerably lower AUC (0.565, 95% CI: 0.562–0.569). The substantial decline in AUC suggests overfitting to the training dataset. Despite this limitation, VGG19 demonstrated superiority in predictive accuracy among the employed algorithms. Given that the remaining three models also displayed substantial reductions in AUC from training to validation, VGG19 consistently demonstrated the highest AUC (Table 2). Based on the WSDL results, we implemented SDL and observed further improvements in predictive performance. VGG19 remained the best-performing model in both the training (AUC = 0.938, 95% CI: 0.937–0.940) and validation (AUC = 0.553, 95% CI: 0.548–0.559) datasets. Notably, when VGG19 was applied to an external testing dataset, the AUC for SDL (0.701, 95% CI: 0.691–0.711) was significantly better than that of WSDL (0.579, 95% CI: 0.570–0.588), highlighting the superior generalization ability of SDL in patch-level prediction (Table 2). According to the results, VGG19 was selected for subsequent multi-instance learning (MIL) feature aggregation. The features extracted by VGG19 were integrated into the WSI-level pathomics signature to enhance the predictive accuracy and robustness of the survival prediction model. The corresponding receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC) curves for VGG19 are presented in Fig. 2a.

a Patch-level ROC curves of VGG19 using both SDL and WSDL methodologies. Regions highlighted in the Grad-CAMs represent tumor cells (b) and tumor-infiltrating immune cells (c), which are annotated in the H&E-stained images with yellow dotted lines. ROC receiver operating characteristic curve, VGG Visual Geometry Group, WSDL weakly supervised deep learning, SDL supervised deep learning.

Furthermore, the Grad-CAM technique was utilized to explore the recognition capabilities of the DL models and regions that significantly influenced the model’s decision-making process, which enhanced the interpretability of the AI platform. Results highlighted that both tumor cells and TIICs were key regions that significantly related to survival prediction at the patch level (Fig. 2b, c).

WSI-level prediction performance

MIL extracted a comprehensive set of 206 features from WSIs. This feature set included 103 features, each from the BoW and PLH methods, along with two probability features and 101 label features. Rigorous feature selection was conducted using correlation coefficients and Lasso-Cox regression, yielding 15 pathomics features identified through SDL and three through WSDL, as illustrated in Fig. 3.

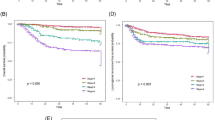

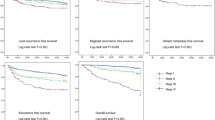

Correlation coefficients and Lasso-Cox regression were utilized for pathomics feature selection through both weakly supervised deep learning (PathWS, a) and supervised deep learning (PathS, e). Kaplan–Meier (KM) analyses were conducted for PathWS (b–d) and PathS (f–h). Based on the median of the expectation of overall survival predicted from the constructed AI platform, oral squamous cell carcinoma patients were stratified into high-risk (overall survival predicted below the median) and low-risk groups (overall survival predicted above the median). i Annotated H&E-stained images, probably maps, and prediction maps of the two AI platforms. Patients in the low-risk group were predominantly assigned a probability label of “0,” whereas those in the high-risk group were mostly assigned a probability label of “1.” H&E, hematoxylin and eosin; c-index, concordance index.

Analysis of c-index values revealed superior performance of SDL (PathS) compared with WSDL (PathWS). PathS achieved c-index values of 0.949, 0.809, and 0.757 in the training, validation, and testing cohorts, respectively (Fig. 3f–h). In contrast, PathWS demonstrated a c-index of 0.952 in the training cohort but exhibited substantial declines to 0.707 and 0.635 in the validation and testing cohorts (Fig. 3b–d). These results indicate that although both methods performed similarly during the training phase, PathS maintained its performance and demonstrated better generalization across internal validation and external testing datasets. The probably and prediction maps explained the findings partially by visualizing the differences in the decision-making processes between the two DL methods (Fig. 3i).

Clinical signature identification

18 clinical features were analyzed initially to develop a prognostic platform based on clinical parameters associated with OSCC patient survival. Univariate Cox regression analysis identified three significant prognostic factors: N stage, clinical stage, and pathological grade (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Table 1). Specifically, OSCC patients at the N2 stage had significantly worse OS relative to those at the N0 stage (HR = 2.846, 95% CI: 1.406–5.759, P = 0.004). Similarly, clinical stage IV was associated with worse outcomes relative to stage I (HR = 3.017, 95% CI: 1.204–7.559, P = 0.018). Pathological grades II (HR = 2.381, 95% CI: 1.200–4.726, P = 0.013) and III (HR = 3.659, 95% CI: 1.329–10.076, P = 0.012) were also associated with lower OS relative to grade I.

Univariate (a) and multivariate (b) Cox regression analyses were performed on clinicopathological parameters to evaluate overall survival in patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC). Kaplan–Meier (KM) analyses demonstrated moderate predictive accuracy for the CS in the training cohort (c) and validation cohort (d). Based on the median of the expectation of overall survival predicted from the constructed CS platform, OSCC patients were stratified into high-risk (overall survival predicted below the median) and low-risk groups (overall survival predicted above the median). F female, M male, FOM floor of mouth, T stage Tumor stage, N stage Lymph Node stage, Path grade pathological grade, WBC white blood cell, RBC red blood cell, NL neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio, AG albumin/globulin ratio, PL platelet/lymphocyte ratio, HR hazard ratio, CI confidence interval, c-index concordance index.

Moreover, multivariate Cox regression analysis, adjusted for potential confounding factors, determined that clinical stage and pathological grade were significant predictors, whereas N stage was excluded (Fig. 4b). Clinical stage IV continued to be associated with a worse prognosis relative to stage I (HR = 5.663, 95% CI: 1.305–24.584, P = 0.021), and pathological grade II (HR = 2.396, 95% CI: 1.123–5.113, P = 0.024) was significantly associated with lower OS relative to grade I. Comprehensive results from univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses are provided in Supplementary Table 1. These significant features were subsequently incorporated into the development of a clinical signature-based cancer prognosis prediction platform (CS), as shown in Fig. 4. The clinical modal platform demonstrated c-index values of 0.662 in the training dataset and 0.721 in the validation dataset, indicating moderate predictive accuracy. The improvement in CS from the training to the validation phase suggests calibration issues or overfitting in the initial model, which were partially addressed during validation. However, it is notable that the predictive efficacy of both PathS and PathWS was significantly higher than that of the CS across cohorts, as indicated by c-index values. These findings highlight the potential clinical value of the pathomics platforms.

Development of a multimodal platform for OSCC survival assessment

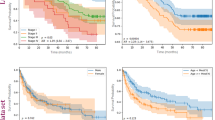

Recognizing the superior efficacy of PathS and the moderate predictive capacity of the CS in stratifying OSCC prognoses, along with evidence supporting the enhanced effectiveness of multimodal platforms in survival assessment for other diseases19,21,38,39, we sought to integrate these approaches into a multimodal prognostic platform. The multimodal platform was visualized using a nomogram and subjected to KM analysis (Fig. 5a, b, e).

a The multimodal platform, combining clinical parameters and pathomics signatures, was represented as a nomogram. The output results are the probability of survival for less than one year (1- ‘1-year OS probability’), three years (1- ‘3-year OS probability’), and five years (1- ‘5-year OS probability’), respectively. Kaplan–Meier analysis revealed the performance of the multimodal platform in the training (b) and validation (e) cohorts. Time-dependent ROC analysis evaluated the predictive accuracy of the multimodal platform for 1-year and 3-year OS in the training (c, d) and validation (f, g) cohorts. PathS pathomics-based AI platform developed through supervised deep learning, OS overall survival, c-index concordance index, ROC receiver operating characteristic curve, CS clinical signatures, AUC area under the curve, CI confidence interval.

In the training cohort, the multimodal platform achieved a c-index of 0.931 (slightly lower than PathS at 0.949), which highlighted its precision regarding prognostic prediction. In contrast, the CS showed a significantly lower c-index of 0.662, suggesting reduced reliability in the training cohort. In the validation cohort, the multimodal platform exhibited a slight decrease in performance, with a c-index of 0.817, but maintained high efficacy. PathS mirrored this trend with a minor reduction in c-index to 0.809; the CS improved to 0.721 but continued to underperform compared with the other platforms.

Considering the close predictive accuracies of PathS and the multimodal model, particularly for the c-index as a single indicator, we further conducted a time-dependent ROC analysis to evaluate their predictive accuracies at various time points (Fig. 5c, d, f, g). In the training cohort, the platforms exhibited strong performance in 1-year survival predictions, with AUCs of 0.844 (95% CI: 0.756–0.933) for the CS, and 0.935 (95% CI: 0.879–0.992) for both PathS and the multimodal platform. Predictions for 3-year survival were even more impressive for PathS and the multimodal platform, nearing perfect AUCs of 0.995 (95% CI: 0.987–1.000) and 0.993 (95% CI: 0.983–1.000), respectively; the CS achieved a significantly lower AUC of 0.744 (95% CI: 0.637–0.851). In the validation cohort, the 1-year survival predictions showed a decrease in AUC values; PathS and the multimodal platform performed well at 0.922 and 0.863, respectively, whereas the CS was significantly worse (AUC = 0.559). The 95% CI for 1-year survival predictions could not be calculated due to the limited number of patients in the validation cohort with overall survival less than one year. For 3-year predictions in the validation cohort, PathS maintained a relatively higher AUC of 0.826 (95% CI: 0.676–0.975) compared with the multimodal platform’s 0.800 (95% CI: 0.614–0.986); the AUC for the CS further declined to 0.721 (95% CI: 0.478–0.965). These results underscore the superior predictive accuracy and generalization ability of PathS and the multimodal platform relative to the CS.

The multimodal platform, which integrates features from pathomics and clinical signatures, demonstrated robustness in both the training and validation cohorts. This was particularly evident in comparison with the CS platform, which solely relies on individual clinical parameters as prognostic indicators. These findings underscore the enhanced predictive capacity achieved by integrating disparate data sources. However, the multimodal platform did not surpass PathS in predictive efficacy, suggesting that the pathomics-based platform already provides sufficient predictive power for cancer prognosis, and the inclusion of clinical parameters did not significantly enhance its accuracy. Overall, the integration of pathomics data substantially amplifies the model’s prognostic capabilities, emphasizing the critical role of such data in refining clinical predictive models.

Discussion

OSCC has become a significant health concern in recent years. With rising prevalence in many countries, it is now the leading cause of oral disease-related mortality40,41. Moreover, OSCC is characterized by a lack of early symptoms, which can result in delayed diagnosis, extensive lesions, and an increased risk of metastasis42. Patients with advanced or metastatic OSCC demonstrate substantially worse clinical outcomes, reflecting both the aggressive biological behavior and significantly reduced overall survival43. Therefore, to help clinicians accurately predict the OS of OSCC and thereby enhance the quality of life of patients, this study developed a novel digital pathology-based AI platform, PathS, which combined VGG19 with SDL (c-index = 0.809). PathS exhibited a higher level of predictive accuracy than the comparator platform based on WSDL. Additionally, the significance of TIICs in OSCC survival was revealed from a novel perspective of AI technology. Furthermore, the AI platform was integrated with CS (c-index = 0.721) into a multimodal survival assessment platform (c-index = 0.817).

Currently, the most widely used method for assessing the prognosis of tumor patients remains the clinical stage, based on the TNM staging system44. However, it still has several limitations, including challenges in measuring the depth of tumor invasion and inconsistencies in the thresholds for T and N stages45,46,47,48. Additionally, histopathological features are also important indicators that guide decisions regarding adjuvant treatments, such as radiotherapy, chemoradiotherapy, or immunotherapy44. However, the current pathological grading system has demonstrated a poor correlation with prognosis44. Our findings align with these observations. Only clinical stage and pathological grade were identified as significantly associated with patient survival during the development of CS. However, the CS platform achieved only moderate predictive accuracy, with c-index values of 0.662 in the training dataset and 0.721 in the validation dataset. These results indicated that additional prognostic indicators were needed to improve the efficacy of OS assessment for OSCC patients.

Pathomics-based AI technologies offer a promising solution15. They may fulfil a distinctive function in pathological image analysis by uncovering relationships or patterns from the huge information contained in H&E images, which is challenging to acquire through conventional methods. This technology has been utilized in several kinds of cancers, demonstrating high predictive efficacy. Wang X, et al. have developed a WSIs-based survival outcome prediction AI model for pan-cancer, such as brain, breast, bladder, and kidney49. Moreover, several AI platforms have been evaluated in clinical trials, indicating their potential clinical value16,38,50. However, the application of such platforms in OSCC remains limited. Previous studies mainly trained pathomics-based AI models to detect prognostic biomarkers for OSCC and assess survival indirectly. Esce et al.26 and Adachi et al.27 trained AI models based on WSIs of primary lesions of OSCC collected from a single hospital to predict occult nodal metastases and lymph node recurrence. Cai et al.51 further detected the presence of a molecular biomarker, chromosome 9p loss, which was found to be associated with poor survival of OSCC. Additionally, Lan et al.24 developed a radiomics-based AI model using MRI data to predict both lymph node metastasis and patient survival. However, to our knowledge, this is the first multicenter study to develop novel AI platforms (PathWS and PathS) that can assess dynamic patient survival directly from WSIs in OSCC. Using H&E images to directly assess tumor patients’ survival is a straightforward method due to its cost-effectiveness and accessibility. As the basis of clinical decision-making, histopathological examination is widely regarded as a fundamental component for cancer patients. Additionally, this approach does not depend on imaging equipment, thereby ensuring its accessibility even in regions characterized by limited medical resources. Furthermore, due to the high molecular resolution of pathomics, pathomics-based AI also demonstrates advantages in providing molecular information, and this topic will be discussed in detail later. In this study, KM analyses indicated that both PathWS and PathS achieved high c-index values and outperformed the CS platform (representing conventional methods in clinical practice), demonstrating their predictive accuracy. Furthermore, despite the observed performance decline in the testing dataset in this study, PathS maintained predictive accuracy (c-index = 0.757), demonstrating its potential robustness against institutional heterogeneity and justifying further development for broader clinical implementation. However, as a known challenge in AI model training, it is important to note that there are still potential factors that affect the generalizability of such AI models. The variation between the Northern China training/validation cohorts and the Southern China testing cohort may be attributed to inter-institutional differences in histopathological preparation protocols, population-specific lifestyle factors, and genomic heterogeneity. Thus, expanded sample sizes and standardized pathological processing protocols are important in future work to better capture population diversity.

Moreover, a comparative analysis was conducted to evaluate the efficacy of WSDL and SDL. Results showed that PathS offered superior generalization ability and less susceptibility to overfitting, relevant to PathWS. The difference may be partially caused by variations in the regions of WSIs that each algorithm analyzes to detect pathological features and make risk stratification decisions. The probability and prediction maps (Fig. 3) also clearly illustrate this distinction. The results indicated that PathS focused more precisely on the tumor and its surrounding infiltrating immune cells, as defined by clinicians’ annotations. This approach allowed a detailed analysis of the relationship between pathological features and prognostic risk within ROIs. In contrast, PathWS analyzed entire WSIs, including normal epithelium and lamina propria regions, which the algorithm frequently identified as low-risk areas for poor survival. This broader focus may affect the process of fusing patch-level features into WSI-level features and, ultimately, the patient-level predicted risk.

In this study, ROIs included the tumor cells and the surrounding TIICs. TIICs are identified as a population of lymphoid and myeloid cells, including lymphocytes, dendritic cells, and macrophages. These cells exit the vasculature and infiltrate the tumor, localizing in intraepithelial and stromal regions52. Two main factors motivated the inclusion of TIICs in the ROIs. First, the close spatial proximity of infiltrating immune cells to tumor cells made it challenging to exclude them from the ROIs during annotation. Second, TIICs are identified as a critical factor influencing survival outcomes in patients with OSCC53,54. The roles of TIICs in cancer progression vary depending on their specific types53. Previous studies have shown that myeloid-derived immune cells and regulatory T cells are associated with poor survival outcomes in patients with OSCC54,55,56,57, whereas tissue-resident marker CD103-positive T cells and dendritic cells have demonstrated anti-tumor effects58. Additionally, Troiano et al.59 classified the immune phenotype of OSCC into three categories, immune-inflamed, immune-excluded, and immune-desert, based on the level of TIICs infiltration, and further confirmed that the survival rate of immune-desert-type OSCC is significantly reduced through an assessment of WSIs from 211 patients. Moreover, these TIICs can also organize into tertiary lymphoid structures (aggregates of lymphocytes in non-lymphoid tissues during chronic inflammation)60, which play critical roles in antigen presentation and lymphocyte activation61, serving as key reservoirs of anti-tumor immunity61,62,63,64. Furthermore, a close relationship between infiltrating T cells and the effectiveness of immune checkpoint blockade therapy has been reported65, as anti-programmed cell death ligand 1 therapy has become an essential component of clinical management66. In our study, Grad-CAM analyses of patches identified both tumor cells and TIICs as key regions. Notably, this constitutes a novel approach. Prior studies mainly employed ML to screen for immune-related gene markers associated with prognosis, which relies on human-defined features to train and learn67,68. However, given DL’s capacity to automatically identify prognostic features from images, these features are not defined or understood easily by humans. Therefore, this finding supported the important role of TIICs in prognosis in OSCC patients from a novel AI aspect. At the same time, this XAI method highlighted the weight of TIICs in the decision-making process of the AI platform, which enhanced the interpretability of PathS.

Moreover, we developed a novel multimodal OSCC prognostic prediction platform. Multimodal models, which integrate diverse clinical features with multi-omics data, have the potential to improve the accuracy of cancer prognosis predictions, enabling more precise and personalized treatment strategies. In recent years, multimodal models have been successfully applied and validated in various diseases19,21,22,39. However, their applications in OSCC have remained limited. In the present study, the multimodal platform demonstrated robust and accurate prognostic prediction performance for OSCC patients, with c-index values of 0.931 and 0.817 in the training and validation datasets, respectively. However, time-dependent AUC analysis indicated that, although the multimodal platform outperformed the CS platform in predictive efficacy, it did not demonstrate a substantial improvement in predictive performance relative to PathS. This finding suggests that the PathS model is already highly effective for prognostic assessment; the incorporation of clinical modal data alone may not sufficiently enhance the predictive accuracy. Recent studies have proposed the integration of additional modalities, such as genomics22 and radiomics69,70. Given that tumors are multifactorial diseases, future investigations could refine the multimodal platform by combining these additional data types to improve its robustness and generalizability. On the other hand, the CS platform exhibited limited predictive capability, which may be due to the relatively small sample size used in this study. Expansion of the sample size could potentially enhance the platform’s accuracy. Additionally, the inclusion of other clinical indicators relevant to prognosis, such as areca nut chewing, chronic irritation, and poor oral hygiene, might improve the platform’s performance. The development of a more comprehensive and precise multimodal platform for predicting cancer patient prognosis remains a critical focus for future research.

In this study, both WSDL and SDL were utilized to develop a pathomics-based platform for clinicians to assess survival in patients with OSCC. Additionally, the pathomics platform was combined with a clinical platform to create a multimodal prognostic platform. This novel platform demonstrated high efficacy for clinical application. However, the study had some limitations. First, future research should incorporate larger sample sizes, more multicenter institutions, and prospective studies to improve predictive performance, particularly for the CS platform. Second, although the findings demonstrated that TIICs represent critical decision-making regions for the pathomics-based AI platform, and previous studies identified that the types of TIICs are significant for the prognosis of OSCC, this study did not differentiate among specific TIIC subtypes; further investigation is needed. Third, additional efforts are needed to develop novel multimodal models that achieve higher predictive accuracy. These efforts include expanding clinical datasets and integrating additional modal data. In the future, we also hope to implement a series of measures to facilitate the translation of AI platform towards clinical application to enhance patient survival and prognosis, including the incorporation of real-world studies, introduction innovative architectures or optimization strategies specifically tailored for OSCC, the promotion of interdisciplinary cooperation, the user training, and the integration of the AI platform with existing healthcare information systems from an ethical perspective.

Methods

Data collection

This retrospective cohort study utilized both WSDL and SDL methodologies to construct a pathomics-based AI platform to generate DL signatures for predicting OS in OSCC patients. Additionally, Cox regression analysis was performed to identify OS-associated clinical features (CS) for the development of a machine learning-based platform. These pathomics and clinical signatures were then integrated to create a comprehensive nomogram platform. Figure 1 presents the workflow of this study.

240 OSCC cases were incorporated in the study cohort. 189 cases were collected from the National Center of Stomatology in Northern China initially, involving patients who underwent radical surgery between January and December 2017. After applying inclusion and exclusion criteria, 174 cases were selected and randomly allocated into a training dataset (n = 122) and a validation dataset (n = 52) in a 7:3 ratio. To evaluate the generalizability of the algorithms, an additional 66 cases were collected from a hospital in southern China, forming an external testing cohort (initially, 70 cases were considered for inclusion). The inclusion criteria encompassed (i) histological confirmation of OSCC diagnosis by experienced pathologists; (ii) receipt of initial radical surgical intervention; and (iii) availability of comprehensive clinicopathological, laboratory, and follow-up data. Exclusion criteria were (i) a history of prior surgery or chemoradiotherapy at other institutions, and (ii) faded or unclear H&E slides due to various factors.

Each case included an H&E-stained slide, which was digitized into WSIs using the NanoZoomer whole slide scanner (NanoZoomer 2.0-HT, Hamamatsu Photonics). These images were subsequently exported in NDPI format using NDPView2 software (version 2.6.17). WSIs were captured at 20× magnification, with typical dimensions of 100,000 × 50,000 pixels, corresponding to a pixel resolution of ~0.5 μm per pixel. Moreover, clinical characteristics were collected only for the training and validation datasets due to their lack in the testing dataset. These characteristics comprised sex, age, lesion site, tobacco use, alcohol consumption, T stage, N stage, clinical stage, pathological grade, and peripheral blood cell counts/associated protein levels (white blood cell, red blood cell, hemoglobin, platelet, neutrophil, lymphocyte, monocyte, albumin, and globulin). The participant inclusion process is shown in Supplementary Fig. 1. Informed consent was obtained from all participants. The study protocol adhered to the ethical principles outlined in the Helsinki Declaration. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Peking University School and Hospital of Stomatology, Beijing, China (PKUSSIRB-202497028) and the Committees for Ethical Review of Research at Xiangya Stomatological Hospital of Central South University (20230024). The report was prepared in accordance with the TRIPOD + AI statement.

Data preprocessing

All WSIs underwent two distinct pre-processing patterns to accommodate the different requirements of SDL and WSDL training paradigms. For SDL, ROIs were carefully annotated on WSIs by experienced pathologists, including both tumor regions and infiltrated immune cells. Tumor-infiltrated immune cells (TIICs) were included due to their close spatial proximity to tumor cells, which hindered exclusion. Then, ROIs were segmented into smaller, uniform patches measuring 512 × 512 pixels, effectively removing all white background areas. Conversely, the WSDL utilized all patches segmented from the WSIs, applying a shared label per patient across all patches, and manual annotation was not required. This process yielded over 0.56 million distinct, non-overlapping tiles. Additionally, to reduce the risk of overfitting and improve model generalizability, we implemented real-time data augmentation during training, including random cropping, horizontal/vertical flipping. Z-score normalization was applied during both training and testing to normalize the intensity distribution across red, green, and blue channels of images, which served as the input for the model.

Patch-level prediction

The development of the AI model implemented a two-tiered approach, comprising patch-level and WSI-level predictions. The former referred to training DL algorithms on individual patches to capture critical OS-associated histopathological features, while WSI-level prediction was further performed with MIL.

In the patch-level prediction phase, we evaluated the performance of CNNs—Dense Convolutional Network 121 (DenseNet121), Residual Networks 101 (ResNet101), Inception_v3, and VGG19. For each case, we developed a patch-level, time-dependent, 5-year survival risk prediction platform. All patches within a given sample were assigned the same patient-specific 5-year OS label. To optimize the model’s performance across different datasets, transfer learning was utilized by initializing the model with weights pre-trained on the ImageNet database. A cosine decay learning rate strategy was adopted, expressed as follows:

In this equation, \({\eta }_{\min }^{i}=0\) is the minimum learning rate, \({\eta }_{\max }^{i}=0.01\) is the maximum learning rate, and \({T}_{i}=30\) indicates the number of epochs in the training cycle.

Furthermore, we trained these four DL models using both WSDL and SDL to evaluate the two training paradigms. Under the WSDL framework, an extensive labeling strategy was applied without annotations, while only annotated ROIs were segmented into patches and labeled when training the SDL models. The prediction accuracy and robustness of these algorithms were assessed using key metrics from the ImageNet competition, including area under the AUC, accuracy, negative predictive value, and positive predictive value.

Fusion of patch-level pathomics signatures into WSIs

MIL techniques were utilized to consolidate the patch-level corresponding probabilities to generate WSI-level predictions and enhance the predictive accuracy of our models. Two primary approaches, the Patch Likelihood Histogram (PLH) pipeline and the Bag of Words (BoW) pipeline, were utilized. These approaches synthesized patch-level predictions, probability histograms, and term frequency-inverse document frequency features to construct patient-level features. During patch-level prediction, probability distributions and classification labels were generated and denoted as \({Patc}{h}_{{prob}}\) and \({Patc}{h}_{{pred}}\), respectively. In the PLH pipeline, the occurrences of \({Patc}{h}_{{prob}}\) and \({Patc}{h}_{{pred}}\) within each bin (each unique value was categorized as a “bin”) were counted, and the resulting features were subjected to min-max normalization and yielded \({Hist}{o}_{{prob}}\) and \({Hist}{o}_{{pred}}\). In the BoW pipeline, a dictionary of unique elements identified in \({Patc}{h}_{{prob}}\) and \({Patc}{h}_{{pred}}\) was built, then vectorized each patch by counting feature frequencies. Term frequency-inverse document frequency weighting was applied to enhance discriminative power and generate \({Bo}{W}_{{prob}}\) and \({Bo}{W}_{{pred}}\). Subsequently, the previously derived features, \({Hist}{o}_{{prob}}\), \({Hist}{o}_{{pred}}\), \({Bo}{w}_{{prob}}\), and \({Bo}{w}_{{pred}}\) were synthesized into a unified and comprehensive feature vector through feature concatenation, represented by \(\oplus\). The concatenation formula is expressed as follows:

Feature selection was refined using the Pearson correlation coefficient, ensuring that only one feature from each highly correlated pair (correlation coefficient >0.9) was retained. This step was critical in determining the feature set. The Lasso-Cox method was then applied to identify and retain non-zero features with the greatest prognostic relevance. The selected features were subsequently incorporated into a Cox proportional hazards model to predict patient survival. Using this model, we calculated the expectation of overall survival for each patient, identifying the pathomics signatures for both PathS (using SDL) and PathWS (using WSDL). The key metric used to evaluate this model was the c-index values.

Clinical signature identification and development of a multimodal platform

Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses were conducted to identify clinical variables significantly associated with patients’ OS, and further develop an ML-based predictive platform (CS). Moreover, prediction results of the PathS model were obtained to form the PathS signature as a benign predictive indicator for OSCC patients, which represents the expectation values of overall survival for OSCC patients. Furthermore, we integrated CS with the PathS signature to create a comprehensive Cox-based multimodal platform, which we then translated into a nomogram. This visualization makes it more user-friendly for clinicians and simplifies the integration of the platform into clinical decision-making processes.

Statistical analysis

To address the complexities of medical image analysis, we utilized advanced statistical methodologies. Specifically, independent sample t-tests were used to assess continuous variables; chi-squared tests were used to evaluate categorical variables. For survival analysis, we implemented Cox proportional hazards models to adjust for multiple predictors and Kaplan–Meier (KM) analysis to estimate survival functions. To determine the prognostic significance of the platform, we stratified samples based on predicted hazard ratios (HRs) and conducted a multivariate log-rank test to evaluate the significance of group separation. Our analytical pipeline incorporated a diverse array of computational tools. Image analysis was conducted using ITK SNAP v3.8.0, whereas custom scripts in Python v3.7.12 were used to tailor our analysis to specific research questions. The Python packages we engaged included PyTorch v1.8.0 for DL model development, scikit-learn v1.0.2 for machine learning algorithms, PyRadiomics v3.0 for the extraction of radiomic features, and Lifelines v0.27.0 for survival analysis. High-performance computing hardware was leveraged, including an Intel 14900k CPU, 64 GB of RAM, and an NVIDIA RTX 4090 GPU, providing the computational power necessary to handle the complex computations required for our advanced image analysis and machine learning tasks.

Data availability

Restrictions are applied to the whole imaging and clinical data of the datasets, which are not publicly available due to patient privacy obligations. All data supporting the findings of this study are available on request for reasonable academic purposes from the corresponding author T.L.

Code availability

The code utilized in this research has not been disclosed publicly. However, it is available on request for reasonable academic purposes from the corresponding author T.L.

References

Chi, A. C., Day, T. A. & Neville, B. W. Oral cavity and oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma—an update. CA Cancer J. Clin. 65, 401–421 (2015).

Bray, F. et al. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 74, 229–263 (2024).

Warnakulasuriya, S. Global epidemiology of oral and oropharyngeal cancer. Oral. Oncol. 45, 309–316 (2009).

Cai, X. et al. Clinical and prognostic features of multiple primary cancers with oral squamous cell carcinoma. Arch. Oral. Biol. 149, 105661 (2023).

Sarode, G. et al. Epidemiologic aspects of oral cancer. Disease-a-Month 66, 100988 (2020).

Chamoli, A. et al. Overview of oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma: Risk factors, mechanisms, and diagnostics. Oral Oncol. 121, 105451 (2021).

Lydiatt, W. M. et al. Head and neck cancers—major changes in the American Joint Committee on cancer eighth edition cancer staging manual. CA Cancer J. Clin. 67, 122–137 (2017).

William, W. N. et al. Immune evasion in HPV−head and neck precancer–cancer transition is driven by an aneuploid switch involving chromosome 9p loss. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 118, e2022655118 (2021).

Wang, Z. et al. Single-cell profiling reveals heterogeneity of primary and lymph node metastatic tumors and immune cell populations and discovers important prognostic significance of CCDC43 in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Front. immunol. 13, 843322 (2022).

Ribeiro, I. P. et al. A seven-gene signature to predict the prognosis of oral squamous cell carcinoma. Oncogene 40, 3859–3869 (2021).

Zhu, M. et al. CircRNAs: a promising star for treatment and prognosis in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 14194 (2023).

Subramaniam, N. et al. Stage pN3a in oral cancer: a redundant entity?. Oral. Oncol. 110, 104815 (2020).

de Almeida, J. R. et al. Development and validation of a novel TNM staging N-classification of oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer 130, 410–420 (2024).

Fernandez-Valverde, S. L. et al. Histologically resolved multiomics enables precise molecular profiling of human intratumor heterogeneity. PLOS Biol. 20, e3001699 (2022).

Swanson, K., Wu, E., Zhang, A., Alizadeh, A. A. & Zou, J. From patterns to patients: Advances in clinical machine learning for cancer diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment. Cell 186, 1772–1791 (2023).

Han, R. et al. Randomised controlled trials evaluating artificial intelligence in clinical practice: a scoping review. Lancet Digital Health 6, e367–e373 (2024).

Razzaq, K. & Shah, M. Machine learning and deep learning paradigms: from techniques to practical applications and research frontiers. Computers 14, 93 (2025).

Shanmuganathan, S. in Artificial Neural Network Modelling (eds, Shanmuganathan, S & Samarasinghe, S.) 1–14 (Springer International Publishing, 2016).

Lipkova, J. et al. Artificial intelligence for multimodal data integration in oncology. Cancer Cell 40, 1095–1110 (2022).

Bhargava, R. & Madabhushi, A. Emerging themes in image informatics and molecular analysis for digital pathology. Annu Rev. Biomed. Eng. 18, 387–412 (2016).

Huang, K. B. et al. A multi-classifier system integrated by clinico-histology-genomic analysis for predicting recurrence of papillary renal cell carcinoma. Nat. Commun. 15, 6215 (2024).

Chen, R. J. et al. Pan-cancer integrative histology-genomic analysis via multimodal deep learning. Cancer Cell 40, 865–878.e866 (2022).

Cai, X. et al. Development of a pathomics-based model for the prediction of malignant transformation in oral leukoplakia. Laboratory Invest. 103, 100173 (2023).

Lan, T. et al. MRI-based deep learning and radiomics for prediction of occult cervical lymph node metastasis and prognosis in early-stage oral and oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma: a diagnostic study. Int. J. Surg. 110, 4648–4659 (2024).

Alabi, R. O. et al. Machine learning in oral squamous cell carcinoma: Current status, clinical concerns and prospects for future-A systematic review. Artif. Intell. Med. 115, 102060 (2021).

Esce, A. R. et al. Predicting nodal metastases in squamous cell carcinoma of the oral tongue using artificial intelligence. Am. J. Otolaryngol. 45, 104102 (2024).

Adachi, M. et al. Predicting lymph node recurrence in cT1-2N0 tongue squamous cell carcinoma: collaboration between artificial intelligence and pathologists. J. Pathol. Clin. Res. 10, e12392 (2024).

Campanella, G. et al. Clinical-grade computational pathology using weakly supervised deep learning on whole slide images. Nat. Med. 25, 1301–1309 (2019).

Tolkach, Y., Dohmgörgen, T., Toma, M. & Kristiansen, G. High-accuracy prostate cancer pathology using deep learning. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2, 411–418 (2020).

Vorontsov, E. et al. A foundation model for clinical-grade computational pathology and rare cancers detection. Nat. Med. 2924–2935 (2024).

Sarker, I. H. Machine learning: algorithms, real-world applications and research directions. SN Comput. Sci. 2, 160 (2021).

Chen, X. et al. Recent advances and clinical applications of deep learning in medical image analysis. Med. image Anal. 79, 102444 (2022).

Pantanowitz, L. et al. Nongenerative artificial intelligence in medicine: advancements and applications in supervised and unsupervised machine learning. Mod. Pathol. 38, 100680 (2025).

Tavolara, T. E., Su, Z., Gurcan, M. N. & Niazi, M. K. K. One label is all you need: Interpretable AI-enhanced histopathology for oncology. Semin. Cancer Biol. 97, 70–85 (2023).

Gunning, D. et al. XAI-Explainable artificial intelligence. Sci. Robot. 4, eaay7120 (2019).

Cimino, M. G. C. A. et al. Explainable screening of oral cancer via deep learning and case-based reasoning. Smart Health 35, 100538 (2025).

Parola, M. et al. Towards explainable oral cancer recognition: screening on imperfect images via Informed Deep Learning and Case-Based Reasoning. Computer. Med. Imaging Graph. 117, 102433 (2024).

Esteva, A. et al. Prostate cancer therapy personalization via multi-modal deep learning on randomized phase III clinical trials. NPJ Digital Med. 5, 71 (2022).

Volinsky-Fremond, S. et al. Prediction of recurrence risk in endometrial cancer with multimodal deep learning. Nat. Med. 30, 1962–1973 (2024).

Ng, J. H., Iyer, N. G., Tan, M. H. & Edgren, G. Changing epidemiology of oral squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue: a global study. Head. Neck 39, 297–304 (2017).

Du, M., Nair, R., Jamieson, L., Liu, Z. & Bi, P. Incidence trends of lip, oral cavity, and pharyngeal cancers: global burden of disease 1990-2017. J. Dent. Res. 99, 143–151 (2020).

Adrien, J., Bertolus, C., Gambotti, L., Mallet, A. & Baujat, B. Why are head and neck squamous cell carcinoma diagnosed so late? Influence of health care disparities and socio-economic factors. Oral. Oncol. 50, 90–97 (2014).

Cai, X. & Huang, J. Distant metastases in newly diagnosed tongue squamous cell carcinoma. Oral. Dis. 25, 1822–1828 (2019).

Almangush, A. et al. Staging and grading of oral squamous cell carcinoma: an update. Oral. Oncol. 107, 104799 (2020).

Almangush, A. et al. Small oral tongue cancers (≤4 cm in diameter) with clinically negative neck: from the 7th to the 8th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer. Virchows Arch. Int. J. Pathol. 473, 481–487 (2018).

Ho, A. S. et al. Metastatic lymph node burden and survival in oral cavity cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 35, 3601–3609 (2017).

Weimar, E. A. M. et al. Radiologic-pathologic correlation of tumor thickness and its prognostic importance in squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity: implications for the eighth edition tumor, node, metastasis classification. Am. J. Neuroradiol. 39, 1896–1902 (2018).

Dirven, R. et al. Tumor thickness versus depth of invasion - analysis of the 8th edition American Joint Committee on Cancer Staging for oral cancer. Oral. Oncol. 74, 30–33 (2017).

Wang, X. et al. A pathology foundation model for cancer diagnosis and prognosis prediction. Nature 634, 970–978 (2024).

Xu, H. et al. Artificial intelligence–assisted colonoscopy for colorectal cancer screening: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 21, 337–346.e333 (2023).

Cai, X. et al. Identification of genomic alteration and prognosis using pathomics-based artificial intelligence in oral leukoplakia and head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: a multicenter experimental study. Int. J. Surg. 111, 426–438 (2025).

Mao, X. et al. Crosstalk between cancer-associated fibroblasts and immune cells in the tumor microenvironment: new findings and future perspectives. Mol. Cancer 20, 131 (2021).

Huang, Z. et al. Prognostic value of tumor-infiltrating immune cells in clinical early-stage oral squamous cell carcinoma. J. Oral. Pathol. Med. 52, 372–380 (2023).

Cai, X. J. et al. Mast cell infiltration and subtype promote malignant transformation of oral precancer and progression of oral cancer. Cancer Res. Commun. 4, 2203–2214 (2024).

Song, J. J. et al. Foxp3 overexpression in tumor cells predicts poor survival in oral squamous cell carcinoma. BMC Cancer 16, 530 (2016).

He, K. F. et al. CD163+ tumor-associated macrophages correlated with poor prognosis and cancer stem cells in oral squamous cell carcinoma. BioMed. Res. Int. 2014, 838632 (2014).

Mao, L. et al. Selective blockade of B7-H3 enhances antitumour immune activity by reducing immature myeloid cells in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 21, 2199–2210 (2017).

Xiao, Y. et al. CD103(+) T and dendritic cells indicate a favorable prognosis in oral cancer. J. Dent. Res 98, 1480–1487 (2019).

Troiano, G. et al. The immune phenotype of tongue squamous cell carcinoma predicts early relapse and poor prognosis. Cancer Med. 9, 8333–8344 (2020).

Schumacher, T. N. & Thommen, D. S. Tertiary lymphoid structures in cancer. Science 375, eabf9419 (2022).

Sautès-Fridman, C., Petitprez, F., Calderaro, J. & Fridman, W. H. Tertiary lymphoid structures in the era of cancer immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer 19, 307–325 (2019).

Fridman, W. H. et al. B cells and tertiary lymphoid structures as determinants of tumour immune contexture and clinical outcome. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 19, 441–457 (2022).

Munoz-Erazo, L., Rhodes, J. L., Marion, V. C. & Kemp, R. A. Tertiary lymphoid structures in cancer - considerations for patient prognosis. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 17, 570–575 (2020).

Zhang, B. et al. Single-cell chemokine receptor profiles delineate the immune contexture of tertiary lymphoid structures in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Lett. 558, 216105 (2023).

Mei, Z., Huang, J., Qiao, B. & Lam, A. K. Immune checkpoint pathways in immunotherapy for head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Int. J. Oral. Sci. 12, 16 (2020).

Cai, X. J., Zhang, H. Y., Zhang, J. Y. & Li, T. J. Bibliometric analysis of immunotherapy for head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. J. Dent. Sci. 18, 872–882 (2023).

He, Y. et al. Machine learning-driven identification of exosome- related biomarkers in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Front. Immunol. 16, 1590331 (2025).

Yang, W. et al. Prognostic biomarkers and therapeutic targets in oral squamous cell carcinoma: a study based on cross-database analysis. Hereditas 158, 15 (2021).

Gao, R. et al. Deep learning for differential diagnosis of malignant hepatic tumors based on multi-phase contrast-enhanced CT and clinical data. J. Hematol. Oncol. 14, 154 (2021).

Khader, F. et al. Multimodal deep learning for integrating chest radiographs and clinical parameters: a case for transformers. Radiology 309, e230806 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Education Research Project of Peking University School and Hospital of Stomatology 2024-ZD-05, Postdoctoral Fellowship Program of China Postdoctoral Science Foundation GZB20240038, National Key RD Program of China 2021YFF1201100. The funder played no role in study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of data, or the writing of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.C. C.P. and C.D. contributed equally to this work. X.C., C.P., C.D., L.L., J.Z. and T.L.: conceptualization and design; X.C., C.P., C.D., Y.C., J.Z., L.G., Z.X., L.L. and T.L.: data curation; C.P., C.D., Y. C., L.L., J.Z., L.G., Z.X.: formal analysis and visualization; C.P., C.D. and X.C.: deep learning methods; X.C., C.P., and C.D.: original draft writing; L.L., J.Z. and T.L.: supervision. L.L., J.Z. and T.L.: manuscript review and edit. All authors read and approve the submission of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cai, XJ., Peng, CR., Ding, CY. et al. Tumor cell- and infiltrating immune cell-based supervised learning artificial intelligence multimodal platform for tumor prognosis. npj Precis. Onc. 9, 348 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41698-025-01125-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41698-025-01125-y