Abstract

This single-arm phase II trial (ACTRN12620000918921) evaluated the clinical activity of tremelimumab (10 mg/kg intravenously every 4 weeks for 6 cycles) in advanced cancers with a high tumour mutational burden (TMB), defined as TMB > 10 mutations/megabase (mut/Mb) on standard platforms (TSO500 panel, F1CDx), or >20 mut/Mb on the TST170 panel. The primary objective was 6-month progression-free survival rate (PFS6) by iRECIST. Secondary objectives included objective response; the ratio of time to progression (TTP) on study to TTP on prior therapy (TTP2:TTP1); overall survival (OS); and safety. After minimum followup of 12 months, the PFS6 was 6% (95% CI 0–24%), with a median PFS and OS of 1.9 (95% CI 1.4–2.8) and 6.3 (2.8–10.3) months, respectively. Amongst 19 evaluable patients, two partial responses occurred in an endometrial adenocarcinoma and an undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma, maintained for 3.8 and 15.9 months respectively, both with TMB >20 mut/Mb. Adverse events were experienced by 19 patients (90%), with 15 patients (72%) experiencing grade 3–5 adverse events. Seven tremelimumab-related serious adverse events (grade 2–3) occurred in 5 patients. While the primary PFS6 endpoint was not met, there were two durable objective responses in rare cancers and a favourable change in disease trajectory for an additional five patients based on TTP ratio \(\ge\)1.3.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Immune responses directed against tumours are one of the body’s natural defences against the growth and proliferation of cancer cells1. However, tumours can evade immune-detection, bypassing this natural defence2,3.

The T-cell response against tumours is regulated by immune checkpoints, including cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 (CTLA-4), and programmed cell death 1 (PD-1)4,5. CTLA-4 delivers a negative regulatory signal to T cells upon binding of CD80 or CD86 ligands on antigen-presenting cells6. In animal models, blockade of CTLA-4 binding to CD80/86 results in markedly enhanced T-cell activation and anti-tumour activity, including killing of established murine solid tumours and induction of protective anti-tumour immunity7.

Tremelimumab is a humanised immunoglobulin (Ig)G2 monoclonal antibody directed against CTLA-4. Ipilumumab, a CTLA-4 directed therapy, improved survival outcomes for patients with metastatic melanoma, despite low objective response rates (10.9%)8. Across clinical studies of tremelimumab monotherapy, a pattern of efficacy similar to ipilimumab has emerged. In a large single-arm phase II study of tremelimumab (15 mg/kg given every 90 days), patients with advanced refractory and/or relapsed melanoma had an objective response rate of 9%9. Each case with response was durable (maintained for at least 6 months), with a median overall survival (OS) of 10.1 months, and 41% of patients remaining alive at 1 year9. Another randomised phase II study of tremelimumab in patients with stage IV lung cancer yielded a 3-month progression-free survival (PFS) of 21% (n = 9/44) compared to 14% (n = 6/43) for patients receiving best supportive care10.

While objective tumour responses with anti-CTLA-4 antibodies are infrequent, the responses may be durable, and translate to a meaningful OS gain11. This needs to be weighed up against the potential toxicities of this treatment, with the latter not previously characterised for this treatment schedule in a pan-cancer setting. Here, we report the findings of our trial of tremeliumumab within the Australian Molecular Screening and Therapeutics (MoST) program12. We leveraged high tumour mutational burden (TMB) to molecularly enrich a pan-cancer population, aiming to increase the proportion of patients with an objective tumour response (OTR) and survival benefit. While TMB has demonstrated utility as a biomarker for predicting OS following PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor therapy amongst several cancer types13, its effectiveness in predicting benefit from CTLA-4 inhibition remains unclear.

Results

Patient disposition and baseline characteristics

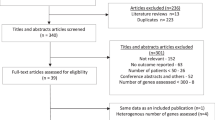

Twenty-two eligible patients were enroled over a 30-month period (October 2020 – March 2023), with 21 patients commencing study treatment. One patient deteriorated after enrolment and did not receive study drug. While initially planned to recruit 24 patients, the trial was closed early due to slow accrual and low response rates. As the sample size calculations used the Mehta-Cain method, the impact of early closure is negligible. The study comprised of 16 patients with carcinomas, 4 with sarcomas and one oligodendroglioma. The median age was 66 (range 38–82) years, 57% were male and 76% had an ECOG PS of 1 or 2 (Table 1). Sequencing was performed on the TSO500 assay for 15 patients, 2 on the FMI assay and 4 by whole exome sequencing.

Clinical activity

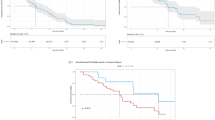

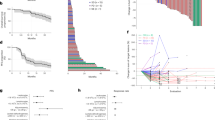

One of 21 patients (6%) achieved PFS6 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 0–24%). Best responses by iRECIST included two partial responses (10%, 95% CI: 3–29%), a further 6 (29%) patients experienced stable disease, while 11 patients (52%) had progressive disease as best response. The partial responses were seen in two patients, one with a mismatch repair deficient, microsatellite unstable endometrial adenocarcinoma and another with undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma, with a TMB of 44.1 mutations/megabase (TSO500) and 49 mutations/megabase (FMI), respectively. The patient with the pleomorphic sarcoma was the only one to remain progression-free at 6 months. There were an additional 5 patients who demonstrated a TTP2:TTP1 ratio \(\ge\)1.3 across a range of cancer types (Fig. 1). The median PFS was 1.9 (95% CI: 1.4–2.8) months and median OS was 6.3 (95% CI: 2.8–10.3) months. One of the patients achieving an OTR had an OS of 20.5 months, while the other patient was censored at 12.3 (95% CI, NE to NE) months, compared with an OS of 5.8 (95% CI, 2.4–8.0) months for patients without an OTR. No difference in median OS was observed based on TTP ratio. When grouped together, patients with an OTR or TTP ratio \(\ge\)1.3 had a median OS of 6.9 (95% CI, 2.8–20.5) months compared with 5.4 (95% CI, 1.4–10.3) months for those without (log-rank P = 0.450).

Safety and tolerability

A median of two cycles (interquartile range 2–3; range 1–9) of tremelimumab was received by study patients. Two of 21 patients (9.5%) received all 6 cycles, while 16 patients (76.2%) ceased treatment due to disease progression or death, two due to unacceptable toxicity, and one due to the development of an exclusion criterion. The two unacceptable toxicities leading to treatment cessation included a patient who experienced grade 2 rash, and lower limb oedema grade 1; and another patient with a urinary tract infection, dyspepsia, pruritis and fatigue (all individually grade 1 or 2). The acquired exclusion criteria was a prolonged QTc interval over 470 ms. One patient was re-treated, with 3 additional doses of tremelimumab received (Fig. 2).

Nineteen of 21 (90%) patients experienced at least one AE, the worst grade reached per patient being 1–2 for 4 (19%) patients and ≥grade 3 for the remaining 15 (72%) patients. The most common AEs occurring in over 20% of patients across grades were fatigue and diarrhoea (n = 8 patients each, 38%), abdominal pain and colitis (n = 5 patients each, 24%). AEs of special interest for tremelimumab occurred in 12 of 21 (57.1%) of patients. These reached a maximal severity of grade 3 and occurred in 5 patients (23.8%); comprising of diarrhoea (n = 3), and colitis (n = 2) (Table 2). Similarly there were 7 tremelimumab-related serious AEs that occurred amongst five patients; all instances involving either grade 2 or grade 3 diarrhoea and/or colitis. There were 31 serious AEs among 10 patients, adjudicated to not be tremelimumab-related. Two were grade 1 in severity (vertigo and fever), 22 were grade 3, five were grade 4 (oesophageal perforation, upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage, urinary tract obstruction, acute kidney injury, and arterial thromboembolism) and two were grade 5 (clostridium difficile-related colitis and myocardial infarction following stent thrombosis) (Table 2).

Quality of life

We compared baseline, to average on study QLQ-C30 global health status scores, with a negative score indicating a deterioration in QoL. Compared to visit 1 (n = 21), a non-significant decrease was observed in mean on-study (n = 16) global health status, −5.2 (interquartile range [IQR], −22.2 to +9.7)14. The only other subscale showing a small reduction from baseline was cognition, −4.2 (IQR, −12.5 to +5.6). On the other hand, the fatigue subscale showed a small improvement, +5.6 (IQR, −4.6 to +19.4) and the diarrhoea and emotional subscales showed a medium improvement on-study compared with baseline, +11.1 (IQR −16.7 to +33.3) and +9.9 (−3.1 to +16.7), respectively15. The change in QoL did no differ between patients with an OTR and/or TTP ratio ≥1.3 compared to those without.

The BPI revealed that 9 (42.9%), 3 (14.3%), and 2 (9.5%) patients had mild (score 0–3), moderate4,5,6 and severe7,8,9,10 pain at baseline, respectively; 7 (33.3%) did not complete the form. With regards to change in pain categorisation on study, 6 (28.6%), 2 (9.5%), 1 (4.8%) had no-change, a deterioration, or an improvement, respectively; 12 (57.1%) had not completed the necessary form(s). The median baseline BPI score (n = 14) was 3.6 (range 0.5–8.5) and the median on-study BPI score (n = 12) was 2.5 (range 1.5–6.3) with a median change of −0.8 (range −7 to +1.5). With regards to interference, categorically 7 (33.3%), 5 (23.8%), and 2 (9.5%) reported mild, moderate and severe interference in activities due to pain; 7 (33.3%) did not complete the form at baseline. On study, no-change, a deterioration, or an improvement, occurred in 4 (19.0%), 4 (19.0%), and 1 (4.8%) patient respectively; 12 (57.1%) did not complete the necessary form(s). The median baseline BPI inference score (n = 14) was 4 (range 0.1–7.7) and the median on-study BPI score (n = 13) was 3.6 (range 0.4–7) with a median change (n = 9) of −0.4 (range −4.1 to +2.0) Fig. 3.

Tertiary exploratory endpoints – outcome by TMB

Our study cohort comprised 13 patients with a TMB between 10 and 20 mut/Mb (intermediate) and 8 patients with TMB \(\ge\)20 mut/Mb (high). Amongst the tumours with an intermediate TMB, median PFS was 1.8 (95% CI, 1.1–2.6) months with none of these patients remaining progression-free at 6 months. Amongst the tumours with high TMB (\(\ge\)20 mut/Mb), median PFS was 2.4 months (95% CI, 1.2–15.9) with 25% (95% CI 4–56%) remaining progression-free at 6 months (log-rank P-value = 0.22). Other exploratory analyses included OS by TMB and indicated a significantly longer OS amongst patients with high TMB, 11.9 (2.0–22.5) months compared with intermediate TMB, 5.2 months (1.4–8.0) (log-rank P-value = 0.04). At 12 months, 50% (95% CI 15–77%) compared with 8% (95% CI 0–29%) of patients with high versus intermediate TMB respectively, remained alive. Post-hoc TMB harmonisation revealed a median harmonised TMB of 10.1 mut/ Mb (range 5.4–133.5), with 10 of 21 (48%) patients yielding a FoundationOne CDx equivalent TMB of <10 mut/Mb.

Outcome by cancer origin

There were nine patients with cancers originating from the gastrointestinal tract (GIT) and 12 with other origins. Median PFS was shorter amongst the cancers with a GIT origin, 1.7 months (95% CI, 0.79–2.1) compared with non-GIT cancers, 2.9 months (95% CI, 1.2–4.3) (log-rank P-value = 0.017). Amongst the GIT cancers, median OS was 4.5 months (95% CI, 0.79–10.3), with 11% (95% CI, 1–39%) of patients alive at 12 months, compared with a median OS of 7.5 months (95% CI, 1.4–16), with 33% (95% CI, 10–59%) of patients alive at 12 months for patients with non-GIT cancers (log-rank P-value = 0.37). In a multivariable analysis of TMB and cancer origin, TMB remained an important predictor of OS, HR 0.31 (95% CI, 0.10–0.98), P-value = 0.046.

Outcome by presence of co-occurring ARID1A and other SWI/SNF complex alterations

Three of 21 patients (14.2%) had tumours harbouring SWI/SNF alterations (comprising ARID1A, ARID1B, PBRM1, SETD2, SMARCA4 and SMARCB1). Stable disease was seen in one colorectal cancer patient harbouring SMARCA4 E920K, whilst two patients (one each with cholangiocarcinoma and glioma) had progressive disease as their best response, both harbouring ARID1A mutations.

Discussion

This signal-seeking trial did not meet its primary endpoint, with a PFS6 rate of only 6% (95% CI 0-24%). Despite this, responses were observed in two patients with TMB \(\ge\)20 mut/Mb in MSI-H endometrial adenocarcinoma and undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma, suggesting that CTLA-4 inhibition has activities in solid tumours with a high TMB in a small proportion of patients. Due to the onset of AEs, the patient with an endometrial adenocarcinoma ceased treatment after 3.8 months. However, both of these patients remained progression-free for at least 6 months. An additional five patients achieved a TTP2:TTP1 ratio \(\ge\)1.3, but neither OTR and/or TTP ratio \(\ge\)1.3 were associated with longer OS. The overall median PFS was 1.9 months (95% CI 1.4-2.8) and median OS was 6.3 months (95% CI 2.8–10.3). This modest efficacy needs to be weighed up against the high toxicity rates experienced by 90% of patients, the majority (72%) \(\ge\) grade 3, albeit only 18% of SAEs were adjudicated as tremelimumab-related and reached a maximum severity of grade 3. There was a small reduction in the mean global health status, but most patients did not report a worse BPI or inference in daily activities.

The MoST program provided a platform for applying high TMB as a predictive biomarker to select patients for tremelimumab in a pan-cancer cohort. Although the study did not meet its endpoint, we have observed responses among patients with high TMB who were treated with CTLA-4 inhibitors in a pan-cancer cohort. This may support the relationship between neoantigen load and response rate extending beyond PD-L1 inhibition. While high TMB is generally associated with improved survival outcomes after PD-L1/ PD-1 therapy alone, or in combination with CTLA-4 inhibitors across a range of cancer types13,16,17, its role as a biomarker for CTLA-4 monotherapy has not been characterised. Despite a small cohort size, PFS was numerically longer for patients with a TMB \(\ge\) 20 mut/Mb compared with TMB between 10–20 mut/Mb and OS was significantly improved. While two patients with a TMB \(\ge\) 20 mut/Mb achieved a partial response, six other patients with similarly high TMB did not. The OS for the patient with a pleomorphic sarcoma achieving an OTR was 20.5 months, while the mismatch repair deficient endometrial carcinoma with an OTR was censored at 12.3 months. In contrast, patients with a high TMB and no OTR reached a median OS of only 5.8 (95% CI, 2.4–8.0) months. A notable limitation of our study was the use of multiple sequencing assays with post hoc TMB harmonisation revealing that in fact the FMI-equivalent TMB was <10 mut/ Mb for half our study cohort. Future studies investigating TMB as a predictive biomarker should implement harmonisation prospectively across all sequencing platforms utilised18. Also, it is essential to move beyond a simple quantification of TMB at a single timepoint, to assessing neoantigen quality and clonality contemporaneously to optimise its predictive value for immunotherapy-related outcomes19.

Cancer histotype introduces an additional variable with respect to responsiveness to CTLA-4 inhibitors as well as survival outcomes in the refractory setting. While rare cancer types such as the pleomorphic sarcomas have limited access and unproven benefits from immunotherapy agents, a combination approach using a PD-1 inhibitor alongside a multikinase targeted agent (lenvatinib) demonstrated PFS and OS gains in endometrial cancers compared to physician’s choice chemotherapy, even amongst mismatch repair proficient tumours20. Whilst the patient with an endometrial adenocarcinoma ceased study treatment early due to toxicity and did not demonstrate a durable PFS, the OTR may have contributed to improving OS, with the patient remaining alive at last followup. There were two patients with pleomorphic sarcomas in our study cohort with a comparable TTP1 of 1.4 and 1.8 months, indicating a similar disease trajectory prior to enroling on this trial. Interestingly, the patient with a TMB of 44 mut/Mb achieved a durable partial response of over 15.9 months, and an OS of 20.5 months while the tumour with a TMB of only 10 mut/Mb progressed on study within 4 months and had an OS of only 11 months. In contrast, high TMB appears associated with poorer survival outcomes amongst patients with gliomas13,14. In our patient with oligodendroglioma, despite a TMB of 187.8 mut/Mb, their PFS was only 1.9 months, and OS was 3 months. The underlying mechanism is proposed to be an acquired mismatch repair deficiency and hypermutation induced by temozolomide19. This appears to generate only poor quality neoantigens that are insufficient to overcome the immune evasive microenvironment of these glial tumours14. An exploratory analysis by cancer type – separating out the gastrointestinal tumours from other cancer types demonstrated a shorter PFS, without a significant difference in OS; however small numbers by individual cancer types precluded analysis within other subsets. A favourable TTP on study, compared with a prior line of therapy occurred in 5 patients without an objective tumour response, none of whom achieved a PFS of 6 months. This indicates a poor prognosis cohort overall. While the addition of CTLA-4 directed therapy to PD-L1/PD-1 therapy is an accepted approach in select cancer types, use of single agent CTLA-4 inhibition is limited8. In cutaneous melanoma, pooled analyses of phase 2b and 3 trials showed a positive correlation between exposure and OS, with higher tremelimumab exposure showing better survival and pharmacokinetic modelling suggesting higher exposures with a dosing schedule of 10 mg/kg q4 weekly8,21. In our cohort, the few patients with an objective response, and/ or favourable TTP ratio had a median OS of 6.9 months, while the remaining patients had a median OS of 5.4 months. This does not support a meaningful clinical benefit from tremelimumab monotherapy, particularly when the drug’s safety profile is considered. Pooled analyses of tremelimumab in melanoma and mesothelioma cohorts have demonstrated differing toxicity rates by cancer type treated, but a consistent pattern of G3 or worse toxicities accounting for the majority of adverse events8,9,21,22. Our study adds to the toxicity profile of single-agent CTLA-4 across different cancer types; demonstrating similarly high rates of adverse events, again with a preponderance for grade 3 or higher toxicities. The strengths of this signal-seeking study are its inclusion of less common cancer types, and an incorporation of TTP1 to understand each individual patient’s preceding disease course to be able to comprehensively capture the relative effects on disease trajectory following tremelimumab.

In sum, this study demonstrates no meaningful clinical benefit for single-agent tremelimumab in a diverse cancer population selected for high TMB. These results may relate to the specific drug, the use of CTLA-4 as a single agent, or the range of cancer types selected. A single patient with an advanced pleomorphic sarcoma with a TMB of 49 mut/Mb however demonstrated a durable OTR and an OS of 20.5 months. These study results do not negate the use of other immunotherapy strategies which are still being tested.

Methods

Study design and participants

This was a phase II, open-label non-randomised trial conducted at 8 Australian centres within the framework of the Molecular Screening and Therapeutics (MoST) program12. MoST is a national platform that offers comprehensive genomic profiling of advanced tumours, alongside molecularly enriched, signal-seeking clinical trials. This trial was registered with Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry, anzctr.org.au (Trial ID: ACTRN12620000918921) on the 17 September 2020. Molecular eligibility was determined by the molecular tumour board (MTB) and this trial planned to enrol 24 patients with high TMB, defined as \(\ge\)10mutations/mb on standard sequencing platforms such as TSO500 panel, FoundationOne®CDx (FMI), or whole exome sequencing and \(\ge\)20 mut/Mb for the TST170 panel. This is based on the FDA approval of pembrolizumab in a pan-cancer setting using 10 mut/Mb FMI equivalent as the threshold for high TMB23. The TST170 panel with a 533 kb footprint is below the 667 kb recommendation for calling TMB high18, but with an elevated threshold of 20 mut/Mb the likelihood of the true TMB being below 10 mut/Mb is low. Only post-hoc TMB harmonisation was undertaken across the assays based on the international efforts underway18,24 [Supplementary Table SI1)]. Eligible patients were aged at least 18 years, with advanced solid cancers of any histological type. Additional eligibility criteria included measurable disease by immune response evaluation criteria in solid tumours (iRECIST) or Response Assessment in Neuro-Oncology Criteria (RANO)25,26, ECOG performance status 0–2, and adequate cardiac (mean corrected QTc <470 ms over 3 ECGs), hepatic, renal, and bone marrow function. All patients were required to have failed (or be unsuitable for) standard therapies for their tumour type, if they existed, and to not have previously received treatment with PD-1/PD-L1 or CTLA-4 inhibitors.

Study procedures

All eligible patients enroled on trial received tremelimumab, which was administered intravenously at a dose of 10 mg/kg every 28 days for a total of 6 cycles, unless there was prior development of disease progression, unmanageable toxicity, or a decision by the patient, or clinician to cease. No dose reductions and/or dose escalations of tremelimumab were permitted. Drug dose were to be adjusted if the weight of the patient changed by ≥10% from baseline. A patient receiving tremelimumab and deemed to be clinically benefiting despite unconfirmed progression (iUPD per iRECIST)25 was permitted to continue tremelimumab at the discretion of the treating investigator, to account for possible pseudoprogression. A confirmatory follow-up scan no later than the next imaging visit (8 weeks) was however mandated to reassess disease status by iRECIST.

Patients who achieved and maintained disease control (complete response, partial response or stable disease) through to the end of the 6-month treatment period were permitted to restart treatment upon evidence of progressive disease (PD), with or without confirmation according to RECIST 1.1, during follow-up. Before restarting treatment, the investigator was required to ensure that the patient did not have any irreversible toxicities that would outweigh benefit from treatment, still fulfilled study criteria, and not have received any intervening systemic anticancer therapy.

Endpoints

The primary endpoint was the progression-free survival rate at 6 months (PFS6) by iRECIST25. Secondary endpoints included OTR; PFS; the ratio of time to progression (TTP) on study treatment (TTP2) to TTP on a prior treatment (TTP1); OS; adverse events (AEs) using National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria, version 5.027; and quality of life (QoL) measured by the EORTC QLQ-C3028, and the Brief Pain Inventory (BPI) assessment29. PFS6 was the proportion of patients who were free of progression and alive at 6 months from the date of registration. PFS was defined as the interval between date of registration and the date of first evidence of disease progression, or death from any cause, whichever occurred first. A TTP2:TTP1 ratio \(\ge\)1.3 was set as the threshold for clinical activity30. Data relating to prior lines of therapy and their duration were provided by the referring clinician at the time of study enrolment. Adjudication of TTP1 data was done centrally at the conclusion of the trial, but without direct knowledge of any of the other study endpoints [Supplementary Table SI2]. OS was defined as the interval from date of registration to date of death from any cause. The BPI short form further characterises pain severity (0 indicating no pain, and 10 indicating ‘pain as bad as you can imagine’ and interference (0 indicating no interference, and 10 indicating complete interference) in activities of daily living.

Exploratory analysis was conducted with prespecified tertiary correlates that included an evaluation of clinical outcomes for tumours with TMB between 10 and 20 mut/Mb compared with tumours having a TMB \({\ge }\)20 mut/Mb; and tumour type, gastrointestinal cancers compared with all other cancer types. Based on emerging preclinical data in a range of cancer types31, and our earlier works32, an exploratory analysis evaluating additional genomic biomarkers, particularly ARID1A and genomic alterations in the Switch/Sucrose Non-Fermentable (SWI/SNF) complex was undertaken. Specifically, we explored whether the presence of these alterations could unify our pan cancer cohort prognostically, and predict better outcomes after tremelumumab.

Statistical considerations

These were based on a similarly heterogeneous, high TMB patient cohort treated on the KEYNOTE-158 trial with single agent pembrolizumab, achieving a PFS6 of 38%33. As tremelimumab monotherapy is not approved in any setting, we applied the 38% threshold for PFS6 to demonstrate comparable activity for tremelimumab to single-agent PD-1 in patients with heterogenous cancer types, enriched for high TMB. Using the method of Metha-Cain, boundaries for declaring activity was determined based on a one-sided 95% confidence interval for PFS6 which would include the hypothesized rate of 38%. Based on a sample size of 24 patients, we required 5 or more patients to be alive and progression-free at 6 months, for tremelimumab to be considered a promising treatment for further evaluation.

Study ethics and consent

The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, with central/institutional ethics and local research governance approval. The MoST program has been approved by the St Vincent’s Hospital Sydney Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC/16/SVH/23). All sites participating in this trial were also covered by St Vincent’s Hospital Sydney HREC (2020/ETH01274), except for Royal Darwin Hospital, which required its own ethics approval from the Human Research Ethics Committee of the Northern Territory Department of Health and Menzies School of Health Research (reference 2019-3465). All participants provided written informed consent to partake in this trial. An independent data and safety monitoring committee provided independent assessments of patient safety.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The molecular data on which molecular tumour board (MTB) recommendations are based can be made available upon reasonable request. The authors declare that data supporting the trial findings are available within the manuscript and its Supplementary Information.

References

Vinay, D. S. et al. Immune evasion in cancer: mechanistic basis and therapeutic strategies. Semin. Cancer Biol. 35, S185–S198 (2015).

Hanahan, D. & Weinberg, R. A. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell 144, 646–674 (2011).

Mantovani, A., Allavena, P., Marchesi, F. & Garlanda, C. Macrophages as tools and targets in cancer therapy. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 21, 799–820 (2022).

Dunn, G. P., Old, L. J. & Schreiber, R. D. The three Es of cancer immunoediting. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 22, 329–360 (2004).

Kresowik, T. P. & Griffith, T. S. Bacillus Calmette-Guerin immunotherapy for urothelial carcinoma of the bladder. Immunotherapy 1, 281–288 (2009).

Nakano, O. et al. Proliferative activity of intratumoral CD8(+) T-lymphocytes as a prognostic factor in human renal cell carcinoma: clinicopathologic demonstration of antitumor immunity. Cancer Res. 61, 5132–5136 (2001).

Peggs, K. S., Quezada, S. A., Chambers, C. A., Korman, A. J. & Allison, J. P. Blockade of CTLA-4 on both effector and regulatory T cell compartments contributes to the antitumor activity of anti-CTLA-4 antibodies. J. Exp. Med. 206, 1717–1725 (2009).

Hodi, F. S. et al. Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 363, 711–723 (2010).

Kirkwood, J. M. et al. Phase II trial of tremelimumab (CP-675,206) in patients with advanced refractory or relapsed melanoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 16, 1042–1048 (2010).

Zatloukal, P. et al. Randomized phase II clinical trial comparing tremelimumab (CP-675,206) with best supportive care (BSC) following first-line platinum-based therapy in patients (pts) with advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). J. Clin. Oncol. 27, 8071–8071 (2009).

Ribas, A. et al. Safety profile and pharmacokinetic analyses of the anti-CTLA4 antibody tremelimumab administered as a one hour infusion. J. Transl. Med. 10, 236 (2012).

Thavaneswaran, S. et al. Cancer Molecular Screening and Therapeutics (MoST): a framework for multiple, parallel signal-seeking studies of targeted therapies for rare and neglected cancers. Med. J. Aust. 209, 354–355 (2018).

Samstein, R. M. et al. Tumor mutational load predicts survival after immunotherapy across multiple cancer types. Nat. Genet. 51, 202–206 (2019).

Touat, M. et al. Mechanisms and therapeutic implications of hypermutation in gliomas. Nature 580, 517–523 (2020).

Cocks, K. et al. Evidence-based guidelines for interpreting change scores for the European Organisation for the Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 30. Eur. J. Cancer 48, 1713–1721 (2012).

Hellmann, M. D. et al. Nivolumab plus Ipilimumab in Lung Cancer with a High Tumor Mutational Burden. N. Engl. J. Med. 378, 2093–2104 (2018).

Wildsmith, S. et al. Tumor mutational burden as a predictor of survival with durvalumab and/or tremelimumab treatment in recurrent or metastatic head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 29, 2066–2074 (2023).

Vega, D. M. et al. TMB Consortium. Aligning tumor mutational burden (TMB) quantification across diagnostic platforms: phase II of the Friends of Cancer Research TMB Harmonization Project. Ann. Oncol. 32, 1626–1636 (2021).

McGranahan, N. & Swanton, C. Clonal heterogeneity and tumor evolution: past, present, and the future. Cell 168, 613–628 (2017).

Makker, V. et al. Study 309–KEYNOTE-775 Investigators. Lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab for advanced endometrial cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 386, 437–448 (2022).

Ribas, A. et al. Phase III randomized clinical trial comparing tremelimumab with standard-of-care chemotherapy in patients with advanced melanoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 31, 616–622 (2013).

Maio, M. et al. Tremelimumab as second-line or third-line treatment in relapsed malignant mesothelioma (DETERMINE): a multicentre, international, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2b trial. Lancet Oncol. 18, 1261–1273 (2017).

Marcus, L. et al. FDA approval summary: pembrolizumab for the treatment of tumor mutational burden-high solid tumors. Clin. Cancer Res. 27, 4685–4689 (2021).

Endris, V. et al. Measurement of tumor mutational burden (TMB) in routine molecular diagnostics: in silico and real-life analysis of three larger gene panels. Int. J. Cancer 144, 2303–2312 (2019).

Wolchok, J. D. et al. Guidelines for the evaluation of immune therapy activity in solid tumors: immune-related response criteria. Clin. Cancer Res. 15, 7412–7420 (2009).

Wen, P. Y. et al. Updated response assessment criteria for high-grade gliomas: response assessment in neuro-oncology working group. J. Clin. Oncol. 28, 1963–1972 (2010).

National Cancer Institute, US Department of Health and Human Services. Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) version 5, https://ctep.cancer.gov/ (2017).

Aaronson, N. K. et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 85, 365–376 (1993).

Cleeland, C. S. & Ryan, K. M. Pain assessment: global use of the Brief Pain Inventory. Acad. Med 23, 129–138 (1994).

Von Hoff, D. D. et al. Pilot study using molecular profiling of patients’ tumors to find potential targets and select treatments for their refractory cancers. J. Clin. Oncol. 28, 4877–4883 (2010).

Shen, J. et al. ARID1A deficiency promotes mutability and potentiates therapeutic antitumor immunity unleashed by immune checkpoint blockade. Nat. Med. 24, 556–562 (2018).

Kansara, M. et al. Genomic alterations associated with response to immune checkpoint inhibitors in rare cancers: a biomarker exploration study from the Australian Molecular Screening and Therapeutics (MoST) Program. J. Clin. Oncol 41, 16 (2023).

Marabelle, A. et al. Association of tumour mutational burden with outcomes in patients with advanced solid tumours treated with pembrolizumab: prospective biomarker analysis of the multicohort, open-label, phase 2 KEYNOTE-158 study. Lancet Oncol. 21, 1353–1365 (2010).

Acknowledgements

The Molecular Screening and Therapeutics (MoST) Program is funded by the Commonwealth and the NSW governments through the Office of Health and Medical Research, NSW. The authors thank all study participants and their families. We kindly acknowledge Astra Zeneca for funding support and provision of study medication for this MoST clinical trial.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.T., F.L., P.S.K., and D.T. contributed to the conceptualisation and development of the trial. S.T., F.L., D.E., J.G., M.K., and D.T. contributed to the tertiary correlatives within this manuscript. S.T., F.L., D.E., J.G., P.S.K., S.C., J.S., and D.T. contributed to the implementation, investigation, and clinical trial analysis. J.G., F.L., S.T., M.K., and D.T. played a key role in the bioinformatics and genomics analysis of patients screened and enroled on the trial. All authors were involved in writing, reviewing, and editing the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

D.T. as CEO of Omico, a non-profit organisation has received grants, consultancies or research support from Roche, Astra Zeneca, Pfizer, Eisai, Illumina, Beigene, Elevation Oncology, RedX Pharmaceuticals, Sun-Pharma, Bayer, Abbvie, George Clinical, Janssen, Merck, Kinnate, Microba, BioTessellate, Australian Unity, Foundation Medicine, Guardant, Intervenn, Amgen, Seattle Genetics and Eli Lilly. D.T. also serves on the advisory boards or committees for Canteen, UNSW SPHERE and NSW government in respect to genomics and translational medicine. The authors otherwise declare no competing financial or non-financial interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Thavaneswaran, S., Lin, F., Espinoza, D. et al. A signal-seeking phase 2 study of tremelimumab in advanced cancers with high tumour mutational burden. npj Precis. Onc. 9, 372 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41698-025-01156-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41698-025-01156-5