Abstract

Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) is resistant to radiotherapy due to tumor hypoxia and abnormal angiogenesis, necessitating strategies to enhance therapeutic outcomes. This study evaluates the use of minibeam radiation therapy (MBRT), delivered through a novel 3D-printed collimator made of polylactic acid (PLA) and tungsten, to modulate the TNBC microenvironment and potentially overcome radioresistance. Three collimator configurations (400, 600, 800 μm beam widths) were tested. Mice received MBRT (150 Gy) or conventional radiotherapy (CRT, 7 or 15 Gy), with tumor responses assessed using histology, RNA sequencing, and immunohistochemistry. The measured beam FWHM values for the MBRT 0.4, 0.6, and 0.8 groups were 419 ± 23 μm, 575 ± 31 μm, and 798 ± 50 μm, respectively, while the CTC distances were 832 ± 25 μm, 1296 ± 21 μm, and 1651 ± 49 μm. MBRT generated stable, spatially fractionated dose distributions with high peak-to-valley ratios. Compared to CRT at equivalent valley doses, MBRT significantly reduced tumor growth, proliferation, and hypoxia while increasing necrosis. Mechanistically, MBRT downregulated HIF-1α/VEGFR signaling, alleviating hypoxia and angiogenesis, and enhanced vascular normalization via increased pericyte coverage. These findings suggest MBRT reprograms the TNBC microenvironment, supporting its potential as a radiosensitizing strategy for clinical translation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) is the most aggressive subtype of breast cancer, characterized by high heterogeneity, lack of molecular targets, and poor clinical outcomes1,2. Despite advances in systemic therapy, TNBC remains associated with high rates of recurrence and resistance to conventional treatments3. One of the major contributors to this resistance is the unique tumor microenvironment (TME), where pathological angiogenesis and persistent hypoxia form a self-reinforcing cycle that promotes tumor progression and therapy resistance4.

Hypoxia plays a central role in this process by stabilizing hypoxia-inducible factor 1-alpha (HIF-1α), which in turn activates the transcription of pro-angiogenic genes such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and angiopoietins5. These factors lead to aberrant vascular structures that further impair oxygen delivery, establishing a vicious cycle of hypoxia and abnormal vasculature. Compared to other breast cancer subtypes, TNBC exhibits a more pronounced hypoxic phenotype, with significantly higher levels of HIF-1α and VEGF expression, thereby presenting a substantial barrier to effective therapy6,7.

Radiotherapy plays a pivotal role in the management of TNBC. However, conventional radiotherapy (CRT) faces two critical limitations: the need to spare normal tissues restricts dose escalation, and uniform high-dose delivery may exacerbate vascular damage and hypoxia, potentially enabling the adaptive survival of residual tumor cells and ultimately compromising treatment efficacy8. These challenges underscore the need for novel strategies that not only deliver effective tumoricidal doses but also reprogram the TME.

Spatially fractionated radiation therapy (SFRT), which delivers a non-uniform spatial dose distribution, has shown promise in overcoming radiation resistance9. Among SFRT modalities, minibeam radiation therapy (MBRT) utilizes submillimeter beamlets to generate alternating regions of high (peak) and low (valley) doses. Preclinical studies have demonstrated that MBRT can achieve superior normal tissue sparing while maintaining tumor control10,11. Nevertheless, the clinical translation of MBRT faces two main challenges: (i) Current methods for generating ultra-narrow beamlets rely on complex synchrotron facilities, limiting accessibility for preclinical research12, (ii) The antitumor mechanisms are still poorly understood, particularly regarding their dynamic modulation of key TME components, such as vasculature, hypoxia, and immune infiltration.

To address these barriers, we developed a novel, self-assembled collimator using 3D printing technology, enabling the generation of clinically relevant MBRT beam profiles with adjustable widths using conventional X-ray sources13. This innovation significantly reduces fabrication costs and facilitates scalable implementation for preclinical research.

In this study, we hypothesize that MBRT and CRT exert distinct effects on the TME, particularly in terms of vascular modulation and oxygen dynamics. To test our hypothesis, we integrated histological habitat analysis with transcriptomic profiling to systematically investigate the impact of MBRT on the TNBC microenvironment, focusing on microvessel density, hypoxic regions, and tumor cell proliferation. Our results demonstrated that MBRT induces vascular normalization and alleviates radiation-associated hypoxia by suppressing the HIF-1α/VEGFR signaling pathway, thereby overcoming a key mechanism of radioresistance. This study mechanistically elucidates the TME reprogramming effect of MBRT and provides a theoretical foundation for the clinical translation of precision radiotherapy strategies in TNBC.

Results

Dosimetric parameters characterization of minibeam collimators

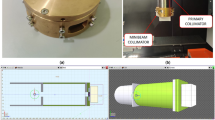

The dosimetric characteristics of the collimator are shown in Table 1. For the MBRT 0.4 group, the measured center-to-center (CTC) distance was 832 ± 25 μm and the beam FWHM was 419 ± 23 μm; for the MBRT 0.6 group, the CTC distance was 1296 ± 21 μm and the beam FWHM was 575 ± 31 μm; for the MBRT 0.8 group, the CTC distance was 1651 ± 49 μm and the beam FWHM was 798 ± 50 μm. The photo of the self-assembled minibeam collimators is shown in Supplementary Fig. S1. The calibration curves for EBT4 and HD-V2 in the three-color channels are presented in Supplementary Fig. S2.

To evaluate the dose depth effects of the system, the beam profiles and dose maps for the entrance plane of a polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) phantom were analyzed using the three collimators (Fig. 1A). These figures demonstrated how MBRT with varying beam widths created blocked and unblocked regions in the film. The trends in peak and valley dose for the three MBRT groups were consistent, with peak dose gradually decreasing due to attenuation at greater depths. Figure 1B visualizes the dose distribution at the entrance plane, as well as at depths of 10 mm and 20 mm. The variations in peak and valley doses with depth are shown in Fig. 1C. At 10 mm depth, the peak dose attenuated by 22.98% for the MBRT 0.4 group, 21.01% for the MBRT 0.6 group, and 25.14% for the MBRT 0.8 group. The valley doses were minimal at the surface and increased with depth, reaching a maximum of approximately 7 Gy around 10 mm. Beyond 10 mm depth, the valley doses gradually decreased as the peak doses were reduced. The main contributor to the valley dose was the dose scattering from adjacent peak dose regions14. Near the surface, scatter from the peak dose regions initially increased with depth but eventually decreased as the peak dose attenuated. After a certain depth, as the peak dose decreased, the valley dose gradually decreased with increasing depth.

A The beam profile at the entrance of the PMMA phantom. The normalized beam profile shows peak-to-valley distributions. Gafchromic film and visualized dose maps display parallel beam patterns, with beam spacings set at 0.4, 0.6, and 0.8 mm from top to bottom. The measured beam FWHM values were 419 ± 23 μm (CTC: 832 ± 25 μm) for the MBRT 0.4 group, 575 ± 31 μm (CTC: 1296 ± 21 μm) for the MBRT 0.6 group, and 798 ± 50 μm (CTC: 1651 ± 49 μm) for the MBRT 0.8 group. B Visualized dose maps of minibeams at different depths (0 mm, 10 mm, 20 mm) in the PMMA phantom. C Variations in peak and valley doses at different depths. D Variation of PVDR values at different depths.

The peak-to-valley dose ratio (PVDR) values showed a consistent trend across the three MBRT groups. PVDRs peaked at the surface, attaining a value of 28. As dispersion in the valley doses increased, PVDR decreased rapidly within the first 10 mm and then declined more gradually. The PVDR values at depths of 10 mm and 20 mm were as follows: 15 and 13 for MBRT 0.4, 15 and 12 for MBRT 0.6, and 16 and 13 for MBRT 0.8 (Fig. 1D). The beam profiles and dose maps for the CRT groups were shown in Supplementary Fig. S3.

Spatial resolution and safety profile of MBRT

The application of MBRT using a small animal irradiator raised two primary concerns: loss of spatial resolution in deeper tissues and potential damage to normal tissues. To assess the beam’s spatial resolution in vivo, mouse brains were irradiated with a total dose of 100 Gy, and the mice were euthanized 6 h post-irradiation. To assess DNA double-strand breaks, brain sections were stained with γ-H2AX. Figure 2A demonstrates a distinct striped pattern of γ-H2AX staining within the irradiated regions, corresponding to the alignment of the MBRT beams. Negligible γ-H2AX signal appeared in the interbeam regions, confirming that these areas were spared from irradiation. The γ-H2AX stripes persisted at deeper tissue levels, indicating that the spatial resolution of the minibeams was preserved at depth in vivo.

A Immunofluorescence staining of mouse brain tissue post-MBRT treatment in three groups. DAPI (blue) stains cell nuclei, while γ-H2AX (purple) highlights DNA double-strand breaks. Green triangles demarcate irradiated regions, and white triangles identify non-irradiated areas; scale bar, 2000 μm; n = 3. B Representative photographs and histopathological analysis of skin 1 month following the MBRT and CRT groups. α-SMA positive signals (green) were sparse, and no evidence of significant fibrosis was detected; scale bar, 500 μm; n = 3. C, D Representative X-ray images and H&E sections of the hind limbs in the MBRT and CRT groups 1 month post-radiotherapy. The bone cortex remained continuous across all groups (black arrows), the bone marrow cavity was normal with preserved cellularity and structure (purple arrows), and the knee joint cartilage surface was smooth (asterisk); scale bar, 500 μm, n = 3. E Masson’s trichrome staining results of muscle tissues 1 month post-radiotherapy across groups. Collagen fibers were stained blue; scale bar, 100 µm; n = 3.

To evaluate the dermatological effects of MBRT compared to CRT, the right hind limbs of mice were irradiated (MBRT dose = 150 Gy, CRT dose = 15 Gy or 7 Gy), and their skin responses were longitudinally monitored. One week post-irradiation, no acute skin toxicity, including ulceration, hemorrhage, or necrosis, was observed in any group (Supplementary Fig. S4). One month post-irradiation, localized radiation-induced alopecia was observed along the beam paths in the MBRT group (Fig. 2B). Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining showed that at both 1 week and 1 month post-irradiation, the tissue architecture in the MBRT groups remained well-preserved, with clear demarcation of epidermal and dermal layers and no observable abnormalities or damage compared to the self-control group. The alpha-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA)-positive signals showed sparse distribution, with no significant fibrosis detected, similar to the CRT 7 Gy group.

For bone damage, X-ray imaging and H&E staining were used to examine the bone structure. X-ray imaging revealed intact and continuous cortical bone in the MBRT groups, as well as in the CRT 7 Gy and CRT 15 Gy groups, with no signs of fractures, bone resorption, or noticeable cortical thinning, and no evident structural damage (Fig. 2C). H&E staining confirmed these observations, demonstrating well-preserved cortical bone integrity and uniform, dense bone matrix across all groups. No signs of osteonecrosis or inflammatory infiltration were observed in the femur and tibia, and the knee joint cartilage surface was smooth and intact with normal thickness (Fig. 2D, Supplementary Fig. S5).

Muscle tissue damage was assessed using Masson’s trichrome staining to evaluate irradiated muscle fibers and collagen deposition. Collagen deposition increased in all radiotherapy groups after radiotherapy, but no significant difference was observed in collagen deposition in the MBRT groups compared with the Control group (P < 0.05). However, collagen fiber deposition was significantly higher in the CRT 7 Gy group compared to the MBRT 0.6 group at 1 month post-irradiation (3.17 ± 0.46% vs. 0.54 ± 0.12%; P = 0.0021), while no significant increase was noted in the MBRT groups (Fig. 2E, Supplementary Fig. S6).

Overall treatment response

Tumor-bearing mice were divided into six groups on day 7 (Fig. 3A). The MBRT groups received a peak dose of 150 Gy, with a valley dose of approximately 7 Gy; while the CRT groups were administered doses of 7 Gy and 15 Gy. All endpoints in this study were subject to ethical euthanasia due to tumor burden exceeding the approved animal protocol limits. Figure 3B illustrates the survival curves, showing significant benefits in the MBRT treatment groups compared to the control group. The log-rank test revealed statistically significant differences in survival rates among the groups (P < 0.0001). Cox proportional hazards regression analysis further confirmed a significant reduction in survival risk for the MBRT groups relative to the CRT 7 Gy group (Fig. 3C). The control group had a median survival time of 25 days, significantly shorter than all treatment groups (Fig. 3D). One-way ANOVA showed that the median survival time in the CRT 15 Gy group was longer than in the CRT 7 Gy group (44 days versus 29 days, P < 0.0001). Furthermore, the survival times for the MBRT groups were significantly longer than those for the CRT 7 Gy group. Specifically, the median survival time was 35 days for the MBRT 0.4 group (P = 0.034), 39 days for the MBRT 0.6 group (P = 0.002), and 38 days for the MBRT 0.8 group (P = 0.013). Mice treated with CRT or MBRT showed no significant weight loss or adverse effects on major organs, hematological parameters, or biochemical profiles (Fig. 3E, Supplementary Figs. S7–S9).

A Experimental procedure and study design for MBRT and CRT. B Survival curves for mice subjected to different treatments as indicated; n = 8. Statistical significance was assessed using the log-rank (Mantel–Cox) test. C Hazard ratios (HR) for the various radiation treatment groups, relative to the CRT 7 Gy group. Error bars represent the 95% confidence intervals (CI) for the hazard ratios. D Median survival times for all treatment groups, value = mean ± SD, n = 8. E Body weights change of mice following different treatments, value = mean ± SD, n = 8. F, G Tumor growth curves for all treatment groups; value = mean ± SD; n = 8. Statistical significance for multiple comparisons was determined using one-way ANOVA (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001).

Tumor volume data indicated that, compared to the untreated control group, mice treated with MBRT exhibited delayed tumor growth dynamics, although tumors continued to grow over time (Fig. 3F). Notably, on day 30 post-tumor inoculation, tumor growth was significantly delayed in the MBRT treatment groups compared to the CRT 7 Gy group (P < 0.001). Figure 3G shows the tumor volume change curves for each group.

Histological tumor habitat response of MBRT versus CRT

The image processing steps for histological data are shown in Supplementary Fig. S10. The optimal silhouette width for 2–10 clusters was indicated by k = 3 (Fig. 4A). The silhouette width measures how close each observation is to the objects in its cluster compared to the objects in other clusters15. Supplementary Table S1 presents the characteristics of the three clusters. Cluster one contained relatively few vessels and Ki-67+ nuclei, with lower nuclei pixel counts but a larger necrosis pixel count. This cluster was defined as a low-vascularity low-cellularity (LV-LC) habitat, indicating a necrotic region. Cluster two had fewer vessels but a significant increase in Ki-67+ nuclei, higher nuclear pixel counts, and a lower necrosis pixel count. This cluster was defined as a low-vascularity high-cellularity (LV-HC) habitat, indicating active cell proliferation despite low blood vessels, suggesting a hypoxic region. Cluster three exhibited the highest number of vessels and Ki-67+ nuclei, with higher nuclear pixel counts and the lowest necrosis pixel counts. This cluster was defined as a high-vascularity high-cellularity (HV-HC) habitat, indicating abundant blood vessels and active cell proliferation, defining it as the proliferative region. Differences in the four characteristics of the three clusters and the visualization of clustering are shown in Fig. 4B, C.

A Silhouette analysis revealed the optimal number of tumor imaging phenotypes was three. B The mean parameter values for each of the identified habitats, value = mean ± SD, n = 8. C The representative parameter maps and a corresponding habitat map for an example tumor, where the HV-HC habitat was shown in red, LV-HC in green, and LV-LC in blue; scale bar, 2 mm. D–F One-way ANOVA of the percentage area occupied by HV-HC habitat, LV-HC habitat, and LV-LC habitat for all groups; value = mean ± SD; n = 8. Statistical significance for multiple comparisons was determined using one-way ANOVA (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001). G Representative tumor histological habitats from the six groups on day 10.

To analyze the effects of different treatments on histological habitats, we calculated the percentage of the area occupied by the three clusters in each group (Fig. 4D–F). The area of HV-HC habitats decreased after CRT 15 Gy or MBRT treatment. The difference between the CRT 15 Gy group and the CRT 7 Gy group was significant (15.81 ± 8.76% vs. 33.34 ± 9.18%, P = 0.0086), indicating that a single high-dose radiation had a more significant effect on the proliferative region. The proportion of HV-HC habitats in the MBRT 0.4, 0.6, and 0.8 groups was also lower than that in the CRT 7 Gy group (P < 0.05), which were 27.53 ± 9.54%, 19.17 ± 10.85%, and 18.22 ± 7.47%, respectively. There was no significant difference between the MBRT group and the CRT 15 Gy group (P > 0.05). Interestingly, the LV-HC habitat area increased significantly in the CRT 15 Gy group, while the MBRT groups showed little change. The LV-HC area in the control group was 43.13 ± 4.90%, in the CRT 7 Gy group was 44.96 ± 8.40%, and in the CRT 15 Gy group it increased to 68.59 ± 8.26%. The LV-HC area in the MBRT 0.4, 0.6, and 0.8 groups was 40.69 ± 6.26%, 48.64 ± 5.16%, and 50.03 ± 7.47%, respectively. There was a significant difference between the MBRT groups and CRT 15 Gy groups (P < 0.0001), indicating that high-dose uniform irradiation had a significant enhancement effect on the hypoxia region compared with the MBRT group. Compared with the CRT group, the LV-LC habitat area increased in all MBRT groups, especially in the MBRT 0.6 group (32.18 ± 7.38%), indicating that MBRT had a more pronounced effect on the necrotic region. Figure 4G shows the representative tumor histological habitats of the six groups on day 10.

MBRT regulates tumor angiogenesis and improves hypoxia by inhibiting the HIF-1α/VEGFR signaling axis

To systematically verify the results of habitat clustering analysis and clarify its molecular mechanism, this study conducted RNA-seq analysis on six groups of experimental samples. MBRT subgroups formed distinct clusters from both the CRT 7 Gy and control groups (Supplementary Figs. S11 and S12). At the genomic level, the MBRT 0.6 group and the CRT 7 Gy group showed an inverse expression pattern (Supplementary Fig. S13A), and a total of 1,530 significantly differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified (988 upregulated and 542 downregulated) (Fig. 5A). Based on GSEA analysis, the angiogenesis-related gene set in the MBRT 0.6 group was significantly downregulated (ES = −0.275, P < 0.001), and GO and KEGG analysis identified DEGs involved in vascular regulation processes (e.g., angiogenesis, positive regulation of angiogenesis) and the synergistic inhibitory effects of the HIF-1α signaling pathway and the VEGFR signaling pathway (Supplementary Fig. S13B, Fig. 5B–D).

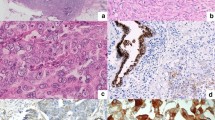

RNA-seq analysis results (n = 3): A The volcano plot shows the distribution of gene expression between the MBRT 0.6 group and the CRT 7 Gy group. B, C GSEA enrichment and heat map of angiogenesis-related gene sets showed that the MBRT 0.6 group negatively regulated tumor angiogenesis. D KEGG pathway analysis of downregulated genes (signal transduction related) in the MBRT 0.6 group compared with the CRT 7 Gy group. E, F HIF-1α immunohistochemical analysis revealed differential responses to radiotherapy regimens; scale bars: 50 μm, 63×, value = mean ± SD, n = 3. G–I CD31/α-SMA double immunofluorescence staining showed that the vascular structure of the MBRT group was significantly improved. The white dotted line outlines the vascular lumen, the CD31 positive signal defines the endothelial cell layer, and the white arrow indicates α-SMA positive pericytes; Scale: 100 μm, 40×; 20 μm, 150×; value = mean ± SD, n = 3, MFI (Mean fluorescence intensity). J The transmission electron microscope images show the effects of treatment groups on tumor vessels. EC endothelial cells, P pericytes, BM basement membrane, RBC red blood cells, LYM lymphocytes, L lumen, J tight junctions, AJ abnormal tight junctions, M mitochondria, SM swollen mitochondria, ELP endothelial luminal projections. TEM magnification: 3000×; scale bar: 5 μm for full view, 1 μm for inset. K Western blot assay of HIF-1α, VEGFR2, eNOS3, Erk, and pErk expression in different groups. Statistical significance for multiple comparisons was determined using one-way ANOVA (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001).

Histopathology showed that MBRT treatment significantly improved the tumor hypoxic microenvironment. Compared with the CRT 7 Gy group, the proportion of HIF-1α positive cells in the MBRT 0.6 group decreased by 83.5% (1.09 ± 0.37 vs 6.67 ± 1.23, P = 0.03) (Fig. 5E, F). The fluorescence intensity of the vascular endothelial marker CD31 decreased by 28.5% (67.66 ± 8.77 vs 94.67 ± 6.83, P < 0.01), while the intensity of the α-SMA increased by 1.93 times (131.71 ± 7.27 vs 68.23 ± 5.85, P < 0.0001) (Fig. 5G–I).

Transmission electron microscopy revealed ultrastructural changes in the endothelial cells across the different treatment groups. Endothelial cells in the control group, CRT 7 Gy group, and CRT 15 Gy group thickened due to hypoxia, and endothelial cells in the CRT 15 Gy group proliferated significantly, with increased swelling of mitochondria in the endothelium (purple arrows pointing to mitochondria), narrowing of the lumen, irregular slit-like lumens, partial rupture of tight junctions between endothelial cells (blue arrows pointing to tight junctions), irregular basement membranes. Endothelial luminal projections were also visible (indicated by green arrows). In contrast, endothelial cells in the MBRT group were slightly thinner, and tight junctions between the cells effectively closed the intercellular gaps. Pericyte processes were observed near the endothelium (Fig. 5J, Supplementary Fig. S14). These changes were accompanied by a significant improvement in vascular permeability (Supplementary Fig. S15).

At the molecular mechanism level, MBRT can synchronously downregulate the expression of HIF-1α and VEGFR2 proteins, inhibit downstream signaling molecules eNOS, Erk, and pErk (Fig. 5K, Supplementary Fig. S16), and RT-qPCR validated the systemic downregulation of angiogenesis-related core regulatory genes (Supplementary Fig. S17). These multimodal evidences indicated that MBRT reshapes the normalized tumor vascular microenvironment by precisely regulating the HIF-1α/VEGFR signaling network. Our results illustrate the implementation of MBRT and its regulatory effects on hypoxia and vascular normalization in TNBC (Fig. 6).

The upper left section illustrates the manufacturing process of the 3D-printed components, including the PLA sheet, slide groove, and clip. These components are then assembled with tungsten plates. The middle shows the assembled microbeam collimator, the main body of which is a sandwich structure. The upper right section illustrates the radiotherapy process using the collimator in small animal models. The lower section presents a schematic representation of how MBRT influences the tumor microenvironment, highlighting its mechanism of reducing tumor angiogenesis and alleviating hypoxia by inhibiting the HIF-1α/VEGFR signaling axis.

Discussion

This study developed an efficient collimator assembly method based on 3D printing technology, establishing an accurate radiotherapy platform suitable for preclinical MBRT research. Our results demonstrated that MBRT significantly delayed tumor growth when the valley dose was comparable to CRT. Moreover, tumor habitat analysis based on cell-vascular density showed that MBRT reshaped the proliferation, hypoxia, and necrotic region of TNBC. Mechanistic studies further supported these findings, revealing that while CRT exacerbated hypoxia in a dose-dependent manner, MBRT exhibited distinct biological advantages. Mechanistic studies further support these findings. Specifically, MBRT inhibited the HIF-1α/VEGFR signaling pathway, reduced tumor vascular density, and improved the hypoxic microenvironment.

Our findings indicated that MBRT achieved improved tumor control and extended survival in preclinical models compared to CRT when equivalent valley doses were maintained. This observation aligns with the seminal work by Nakayama16, which investigated microbeam parameters using fixed 25-μm peak widths with interpeak spacings of 100, 200, and 300 μm. Despite achieving remarkably high 50% tumor control doses (244, 533, and 792 Gy for respective configurations), their study demonstrated no correlation between peak dose magnitude and therapeutic outcome. Crucially, experimental groups with consistent valley doses (13–14 Gy) exhibited equivalent survival rates, establishing valley dose as the critical dosimetric determinant. This conclusion receives further validation from the comprehensive dosimetric analysis conducted by Rivera, who performed systematic comparisons across eight radiation parameters. Multivariate regression analysis further validated valley dose as the primary therapeutic predictor (R² = 0.7636)17.

These findings underscore the critical role of valley dose optimization in future MBRT protocol design. Although clinical SFRT regimens predominantly prescribe peak doses18,19,20, preclinical evidence consistently fails to demonstrate a direct peak dose-therapeutic efficacy correlation. This discrepancy may stem from fundamental differences in the cellular response mechanisms between clinical and preclinical models, which also explains why treatment outcomes may differ even if patients receive the same peak SFRT dose. One limitation of employing peak dose to delineate SFRT efficacy lies in the saturation effect on cell death at doses surpassing approximately 20 Gy. At such high peak doses, cell killing may reach a plateau, where further increases in dose yield diminishing returns in lethality due to maximal DNA damage or other saturated repair pathways21,22,23. This phenomenon has been observed in hypofractionated radiotherapy, such as stereotactic body radiation therapy for lung tumors, where dose-response curves show reduced relative effectiveness at high doses per fraction24,25. This is consistent with radiobiological models incorporating damage saturation, such as the linear-quadratic-linear model, which posits that at ultra-high doses, additional radiation does not proportionally increase cell lethality beyond a certain threshold26,27,28. Therefore, the assessment of valley doses is of critical importance in MBRT.

MBRT demonstrates distinct advantages in remodeling the tumor vascular microenvironment and alleviating hypoxia, whereas conventional CRT exacerbates hypoxic conditions through vascular endothelial damage, ultimately fostering tumor progression via the establishment of a “chronic hypoxia trap.” This phenomenon is characterized in preclinical studies investigating CRT-induced vascular alterations29,30. Preclinical evidence indicates single-dose CRT (5–10 Gy) induces moderate vascular injury, while doses ≥10 Gy provoke severe vasculopathy with marked tumor perfusion reduction31,32,33. Tsai further validated these findings in K1735 melanoma models, comparing single high-dose (12 Gy) versus fractionated (3.4 Gy × 5) irradiation34,35. Their data revealed sustained 50% blood flow reduction and concomitant HIF-1α/VEGFR upregulation at 14 days post-irradiation, suggesting hypofractionated CRT converts transient hypoxia into chronic states. These findings suggest that hypofractionated radiation-induced vascular damage may shift hypoxia from a transient to a chronic state, and the resulting hypoxia-angiogenesis positive feedback loop may further drive tumor progression36. Therefore, endothelial injury and abnormal vascular remodeling induced by CRT are considered key mechanisms underlying the worsening of tumor hypoxia.

Unlike CRT, MBRT demonstrated distinct advantages in transcriptomic and histopathological profiles. Despite delivering ultra-high peak doses, MBRT downregulated HIF-1α expression, disrupting the hypoxia-driven feedforward loop. This suppression reduced VEGF levels and inhibited downstream eNOS/ERK signaling, effectively preventing pathological angiogenesis while improving tissue oxygenation. Notably, MBRT also enhanced vascular integrity and stability, primarily by increasing pericyte coverage, as evidenced by upregulated α-SMA expression, and stabilizing endothelial cell junctions. These changes optimized the vascular ultrastructure. Griffin R. J provided strong evidence supporting this mechanism, reporting a fourfold increase in pericyte density in murine tumors following MBRT37. Given the critical role of pericytes in maintaining vascular stability and function, this increase likely helps preserve blood flow within the tumor, preventing chronic hypoxia. These changes directly affect the characteristics of the TME, which was also confirmed by our habitat analysis from another perspective. After MBRT treatment, proliferation-associated HV-HC habitats were significantly reduced, while hypoxia-associated LV-HC habitats did not show a notable increase. This suggests that MBRT effectively suppresses tumor regions with high proliferative activity while avoiding a substantial exacerbation of hypoxia. Moreover, the proportion of necrotic areas was markedly increased. A study by Annaig Bertho further supports this observation, demonstrating that widespread necrosis occurred in tumors seven days after MBRT, whereas necrosis in the CRT group was limited to small focal areas38. This disparity indicates a fundamental difference in the mechanisms by which MBRT and CRT induce tumor cell death. Collectively, these findings suggest that MBRT may shift the TME from a pro-tumorigenic “favorable niche” to one that is more conducive to antitumor effects by enhancing vascular stability and mitigating hypoxia-driven tumor progression39. These insights not only underscore the potential of MBRT in modulating the tumor vascular microenvironment and refining SFRT strategies but also provide new directions for future clinical applications.

Most collimator designs described in the literature are relatively fixed, limiting the flexibility to adjust beam width and spacing40,41. In contrast, the 3D-printed collimator used in this study significantly enhances experimental flexibility and operational efficiency, enabling a broader range of researchers to utilize minibeam irradiation technology. Compared to other SFRT techniques such as GRID and Lattice SFRT, MBRT has a higher therapeutic index, allowing for dose escalation while enhancing normal tissue tolerance, thereby reducing treatment-related toxicity while ensuring tumor control. Moreover, MBRT permits precise control of minibeam size and spacing, whereas in GRID therapy, these parameters are typically constrained by fixed structures. The dosimetric characteristics of our method are highly consistent with those reported in previous studies. The percent depth dose (PDD) patterns, including peaks, valleys, and the PVDR, align closely with those previously measured and reported in MBRT dosimetry evaluations42. Furthermore, we used radiochromic films with two different sensitivity ranges to accurately measure both peak and valley doses, achieving greater precision compared to earlier studies43. The key advantage of our method lies in the time and cost efficiency brought by 3D printing technology. Unlike traditional collimators, which require complex custom machining, 3D-printed collimators, based on a modular design, can be rapidly iterated and optimized, adjusting beam width to accommodate various tumor morphologies, significantly reducing manufacturing time and costs. This high adaptability not only accelerates preclinical research but also enhances the feasibility of clinical translation. Although this method is currently applied primarily in mouse models, its simplicity and cost-effectiveness present promising potential for future clinical applications. This innovation could drive radiation oncology toward more personalized treatment approaches, combining advanced dosimetric techniques with optimized treatment plans to better meet the individual treatment needs of patients.

While this study provides evidence for the efficacy of MBRT in remodeling the TME and overcoming radioresistance in TNBC, several limitations exist. First, the lack of non-invasive imaging methods, such as diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging, dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging, and super-resolution microvascular ultrasound contrast imaging, limited our ability to dynamically monitor TME changes during MBRT treatment. These techniques could provide longitudinal insights into tissue microstructure, vascular perfusion, and permeability, which are critical for fully evaluating MBRT efficacy44,45,46. Second, human TNBC exhibits greater heterogeneity, more aggressive metastatic potential, and complex interactions with the immune system. The study was conducted in mouse models of TNBC, which may not fully replicate the biological characteristics of human tumors. Third, although our 3D-printed collimator provides design flexibility, the study examined only specific beam widths and spacings, further research is required to optimize these parameters for diverse tumor types. Finally, the study primarily assessed tumor control and survival outcomes, while long-term effects, such as potential late toxicities and tumor recurrence, remain unaddressed.

In summary, this study indicates that MBRT offers potential benefits in treating TNBC in preclinical models, particularly by enhancing tumor vascularization, reducing hypoxia, and delaying tumor progression. The cost-effectiveness and design flexibility of 3D-printed collimators enhance the accessibility of MBRT and enable rapid optimization of dose distribution, with potential applicability to various tumor types. These technical attributes offer a promising foundation for future clinical translation.

Methods

Design and specifications of the assembled minibeam collimators

To create a spatially fractionated radiation field, a self-assembled collimator was developed that transforms a uniform radiation field into multiple minibeams. The self-assembled collimator consists mainly of polylactic acid (PLA) sheets and tungsten plates. The PLA sheets were fabricated using 3D printing technology (Bambu Lab X1-Carbon 3D Printer), with dimensions of 40 mm in length, 10 mm in width, and thicknesses of 0.4 mm, 0.6 mm, and 0.8 mm. The tungsten plates were cut using wire-cutting technology and possessed identical dimensions to the PLA sheets. The PLA and tungsten sheets of the same thickness were subsequently stacked to form a sandwich-like structure, resulting in a 50% ratio of blocked to unblocked regions47. The collimators were designed to theoretically produce beam widths of 400 μm, 600 μm, and 800 μm, with corresponding CTC distances of 800 μm, 1200 μm, and 1600 μm, respectively. The collimator design also included fixing models on both sides, incorporating slide grooves and clips to ensure a secure fit for the sandwich structure. Finally, the model files were imported into Bambu Studio for printing with PLA material.

Irradiation

An industrial small animal irradiator (X-RAD 320, Precision X-Ray Inc.) was used as the radiation source. All experiments were conducted with tubes operating at 310 kV and 12 mA, with a dose rate of 3 Gy/min. The beam was filtered using an additional 2 mm of aluminum, and the target was positioned at a source-to-surface distance of 50 cm. A uniform irradiation field was established using a beam collimator with a field dimension of 15 mm.

Dosimetry measurements

Dose measurement and dose distribution analysis were conducted using GAFCHROMICTM HD-V2 (peak) and EBT4 (valley) radiochromic films (Ashland Advanced Materials, Bridgewater, NJ, USA)48,49. Calibration curves were established using known dosages to determine the doses delivered to the high- and low-dose areas of the MBRT. After irradiation, the films were stored in dark envelopes for 24 h to allow for full development. The application of radiochromic films adhered to the protocols established in the AAPM Task Group 235 radiochromic film dosimetry report50. The films were scanned at 300 dpi resolution in 48-bit Red-Green-Blue (RGB) mode using an Epson 12000 XL scanner (Epson America Inc., CA), and the files were saved in Tagged Image File Format (TIFF). The scanned films were imported and analyzed using ImageJ and MATLAB R2021 software, with analysis conducted exclusively on red channel data. To calculate the PDD reduction, PVDR, FWHM, and output factor of the beams generated by the collimator, films were positioned at various depths within a PMMA phantom composed of 10 slabs, each measuring 30 × 30 × 2 mm51.

In vivo feasibility assessment

BALB/c mice (6 weeks; female) were purchased from Huafukang Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). Animal experiments obtained ethical approval from the Ethics Committee for Medical Research and New Medical Technology of Sichuan Cancer Hospital (Approval No.: SCCHEC-04-2024-014). Animal experiments were conducted in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines for animal research (Supplementary information)52. All animal procedures, including anesthesia and euthanasia, were conducted with the aim of minimizing animal suffering and ensuring their welfare. The mice were housed in a specific pathogen-free environment with the temperature maintained between 22 °C and 26 °C and relative humidity between 40 and 70%. For anesthesia induction, all mice in each group were placed in an anesthesia chamber and administered 4.0% isoflurane with 100% oxygen at an initial flow rate of 2.0 L/min. To maintain anesthesia, the flow rate was reduced to 0.6 L/min. Isoflurane was used for rapid induction, followed by intraperitoneal injection of a ketamine (80 mg/kg) and xylazine (5 mg/kg) combination to ensure deep anesthesia during the irradiation process, keeping the animals unconscious and pain-free. The depth of anesthesia was monitored by assessing respiratory rate, heart rate, toe pinch reflex, and righting reflex. Irradiation was performed once the righting reflex was lost. To shield the mice, a 1 cm-thick lead shield was applied to all body areas not within the irradiation field. Euthanasia was carried out using carbon dioxide (CO2) by placing the mice in a dedicated CO2 chamber, which was progressively filled at a rate of 30–70% of the chamber volume per minute until the animals ceased breathing, with death confirmed (no heartbeat or respiration for at least 3 min). This method was chosen for its speed, humaneness, and ability to minimize animal suffering.

To examine the spatial resolution of the beam in vivo, the mid-posterior region of the mouse brain was irradiated with collimators delivering 100 Gy beams. Brain tissue was harvested 6 h post-irradiation. Whole mouse brains were fixed in formalin for 48 h, embedded in paraffin, and serially sectioned at a thickness of 5 µm. Slides were subjected to γ-H2AX immunofluorescence (IF) staining, a marker for DNA damage and repair.

To assess normal tissue effects, the right hind limbs of mice were irradiated with MBRT (150 Gy) or CRT (7 Gy or 15 Gy), with the left hind limbs serving as the internal controls. Skin samples were collected at 1 week and 1 month post-irradiation for H&E staining, α-SMA staining, and photography to evaluate skin toxicity. Muscle tissues from the irradiated hind limbs were assessed using Masson’s trichrome staining to detect fibrosis. Bone tissues were evaluated using X-ray imaging (Bikang Tiancheng Information Technology Co., Ltd., China) and H&E staining to assess structural integrity. For skin H&E staining, skin samples were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde at 4 °C for 24 h, then dehydrated through a graded ethanol series, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned at 5 µm. Sections were deparaffinized, rehydrated, stained with hematoxylin for 4 min, and counterstained with eosin for 20 s. For α-SMA immunofluorescence, skin sections underwent antigen retrieval in 10 mM sodium citrate buffer (pH 6.0), were blocked with 10% bovine serum albumin (BSA), and incubated overnight with an anti-α-SMA antibody at 4 °C. Alexa Fluor-conjugated secondary antibodies were applied for 1 h at room temperature, followed by DAPI counterstaining for nuclear visualization. Muscle tissues were stained with Masson’s Trichrome Stain kit (Solarbio, G1340). Bones were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 24 h, decalcified in 10% nitric acid aqueous solution for 24 h, and then processed for sectioning and H&E staining.

The primary antibodies used in this study included phospho-histone H2A.X rabbit mAb (Cell Signaling Technology, dilution 1:250, 9718) and anti-alpha-smooth muscle actin antibody (Abcam, dilution 1:1000, ab124964). All histological analyses followed standard protocols, and images were quantified using ImageJ software.

Treatment effects and follow-up

The breast cancer subcutaneous tumor mouse model was established by subcutaneously injecting 10 × 105 4T1 cells into the right hind limb of mice. Once the tumor volume reached 150–200 mm3, the mice were randomly divided into six groups: (i) Control group, (ii) CRT 7 Gy group, (iii) CRT 15 Gy group, (iv) MBRT 0.4 group, (v) MBRT 0.6 group, and (vi) MBRT 0.8 group. The radiation dose for the MBRT groups was 150 Gy53. Survival time was calculated from the date of tumor cell injection to the time of death. Tumor diameter was measured every other day, and tumor volume was calculated using the formula: volume = L × W2 × 0.52, where L is the longest dimension and W is the shortest dimension (mm). Animals were humanely euthanized via CO2 inhalation when tumor volume surpassed 1.5 cm3. Comprehensive systemic safety was evaluated through blood counts, biochemical profiles, and histological analysis of major organs (heart, liver, spleen, lung, and kidney).

Discovery of histological tumor habitats

H&E staining of the tumor was performed according to the manufacturer’s guidelines. The expression of CD31 and Ki-67 was evaluated using an immunohistochemical (IHC) method. Primary antibodies used included: CD31 rabbit mAb (Cell Signaling Technology, dilution 1:200, 77699) and Ki-67 polyclonal antibody (Proteintech, dilution 1:2000, 28074-1-AP).

The slices were digitally scanned using NZAcquire software (version 3.1.30, Hamamatsu Photonics, Japan) with high-resolution (40×) brightfield microscopy. Image processing was performed using Python and custom MATLAB scripts. The whole slide images (WSIs) for CD31 and Ki-67 were initially spatially registered with the corresponding H&E staining of each tumor sample. The registration process employed the VALIS package, which provides a fully automated pipeline for registering WSIs using both rigid and non-rigid transformations54. Subsequently, a senior pathologist manually segmented the H&E histological images to generate staining-positive masks for the entire tumor slide. To distinguish between nuclei and necrosis masks, the K-means clustering algorithm was applied for the automatic segmentation of the H&E-stained slides. The IHC images were converted to the LAB color space. Using the manually drawn masks, Otsu’s method was then applied to segment Ki-67+ and CD31+ components, producing Ki-67+ nuclei masks and CD31+ vascular masks.

Neighborhood analysis was used to quantify both vessel density and the density of proliferating tumor cells55. A neighborhood size of 150 × 150 µm was defined for each pixel in the IHC slides; individual connected components within a 150 × 150 µm neighborhood were counted. These counts were assigned as the density values for vessels (CD31+ vessel density) or proliferation cell nuclei (Ki-67+ nuclei density), producing a staining density map. For cell nuclei and necrosis masks clustered from H&E staining, pixel values within each 150 × 150 µm neighborhood were calculated, creating staining density maps for nuclei and necrosis. Staining density maps were presented as counts per unit, where the “unit” refers to the 150 × 150 µm neighborhood surrounding each pixel56. Multi-parameter pixel data were extracted from the spatially aligned staining density maps for each tumor tissue mask, creating a four-dimensional vector for each pixel, including nuclei, necrosis, Ki-67+ nuclei, and vessel density. The data were normalized to ensure equal contributions of all parameters during clustering. K-means clustering was then performed with k values ranging from 1 to 10. The silhouette coefficient was calculated to assess clustering performance. For each cluster, the average counts of vessels, Ki-67+ nuclei, nuclei pixels, and necrosis pixels were computed.

RNA sequencing

Tumor tissue samples were collected on day 10 post-radiotherapy for RNA sequencing. RNA-Seq was performed by OE Biotech Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). The clean reads were aligned to the mouse genome GRCm39 using HISAT257. DEGs were identified using DESeq258. RNA sequencing data were analyzed using the TCC package (v1.46.0) for differential expression analysis59. Bioinformatics analysis was conducted using the OECloud platform (https://cloud.oebiotech.com/task/).

Immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence analysis

Deparaffinized tumor sections were subjected to antigen retrieval in 10 mM sodium citrate buffer, followed by blocking with 5% BSA. The slides were incubated overnight at 4 °C with anti-HIF-1 alpha antibody, then probed with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies and visualized using a DAB substrate kit with hematoxylin counterstaining. Excised tumors were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight, cryoprotected in 30% sucrose solution for 72 h, and embedded in OCT compound (4583, Maokang Biotechnology Co., Ltd, China). Cryosections (6-μm thickness) were stained overnight at 4 °C with anti-αSMA and anti-CD31 antibodies, followed by incubation with Alexa Fluor-conjugated secondary antibodies and DAPI for nuclear labeling. Digitally scanned slides were analyzed by counting three representative fields per slide using ImageJ software. Primary antibodies used were as follows: Anti-HIF-1 alpha rabbit polyclonal antibody (Cell Signaling Technology, dilution 1:100, 48085S), CD31 rabbit mAb (Cell Signaling Technology, dilution 1:200, 77699), and anti-alpha-smooth muscle actin antibody (Abcam, dilution 1:1000, ab124964).

Transmission electron microscopy analysis

Tumor tissues were dissected into fragments (~30 mm3) and fixed in 3% glutaraldehyde at 4 °C for 1 h. The fragments were embedded in EPON resin, and ultrathin sections (70–90 nm thickness) were prepared using a Leica EM UC7 ultramicrotome. The sections were stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate. The grids were examined using a Hitachi HT7800 transmission electron microscope.

Vascular permeability assay

Tumor vascular leakage was assessed using Evans blue (EB; 2% in PBS; Yeasen, 60528ES08) dye. EB dye was injected via the tail vein 1 h prior to tumor tissue collection. EB leakage was quantified in tumor tissue after homogenization and incubation in formamide (24 h, 55 °C). The absorbance of the supernatant at 620 nm was measured to quantify EB leakage. Results were calculated using a standard curve of EB in formamide and expressed as μg/mg tissue.

RNA isolation, quantitative reverse transcription, and RT-qPCR

Total RNA was extracted from tumor tissues using the SteadyPure Universal RNA Extraction Kit (AG21017, Accurate Biotechnology Co., Ltd., China). Reverse transcription was performed with 1 μg total RNA and the ExonScript® RT SuperMix with dsDNase Kit (A502-02, Exongen Co., Ltd, China). qPCR analysis was conducted on a CFX96 Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad, USA) with an UltraStart SYBR Green qPCR Master Mix Kit (A403-02, Exongen Co., Ltd., China). All experiments were independently repeated three times. The primers used are listed in Supplementary Table S2.

Western blot analysis

Tumor tissues were homogenized in RIPA lysis buffer (Yeasen, 20101ES60, China) containing protease inhibitors (Yeasen, 20124ES10, China) and phosphatase inhibitors (Yeasen, 20109ES20, China). Protein concentrations were determined using a bicinchoninic acid assay kit (PC0020, Solarbio® Life Sciences Co., Ltd., Beijing, China). Equal protein aliquots (100 μg) were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes (0.45 μm pore size; Merck Millipore Ltd, USA) at 4 °C for 2 h (constant current 300 mA) using a wet transfer system. Prior to transfer, PVDF membranes were activated in 100% methanol for 1 min. Membranes were blocked with 5% BSA for phosphorylated protein detection or 5% non-fat milk for other targets (room temperature, 2 h), followed by overnight incubation with primary antibodies at 4 °C. After washing with Tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween-20 (TBST), membranes were incubated with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (room temperature, 1 h). Protein bands were visualized using a chemiluminescence detection kit (SQ201, Shanghai Epizyme Biomedical Technology Co., Ltd, China). Antibody details are provided in Supplementary Table S3.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using GraphPad Prism (version 9.3.1, San Diego, CA). Kaplan–Meier survival analysis was performed using the log-rank (Mantel–Cox) test, and the Cox proportional hazards model was used to analyze differences in hazard ratios (HR) between treatment groups. Multiple comparisons were performed using one-way ANOVA or the Kruskal–Wallis test. Statistical significance was determined as follows: ns, non-significant; ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗P < 0.0001.

Data availability

The datasets used or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code availability

All relevant codes are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

References

Bianchini, G., De Angelis, C., Licata, L. & Gianni, L. Treatment landscape of triple-negative breast cancer—expanded options, evolving needs. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 19, 91–113 (2022).

Zheng, S. et al. Long non-coding RNA HUMT hypomethylation promotes lymphangiogenesis and metastasis via activating FOXK1 transcription in triple-negative breast cancer. J. Hematol. Oncol. 13, 1–15 (2020).

Kumar, H. et al. A review of biological targets and therapeutic approaches in the management of triple-negative breast cancer. J. Adv. Res. 54, 271–292 (2023).

Carmeliet, P. & Jain, R. K. Principles and mechanisms of vessel normalization for cancer and other angiogenic diseases. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 10, 417–427 (2011).

Rodriguez, D. et al. Hypoxia pathway proteins and their impact on the blood vasculature. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 9191 (2021).

Jiang, X. et al. The role of microenvironment in tumor angiogenesis. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 39, 1–19 (2020).

Tutzauer, J. et al. Breast cancer hypoxia in relation to prognosis and benefit from radiotherapy after breast-conserving surgery in a large, randomised trial with long-term follow-up. Br. J. Cancer 126, 1145–1156 (2022).

Wang, K. & Tepper, J. E. Radiation therapy-associated toxicity: etiology, management, and prevention. CA Cancer J. Clin. 71, 437–454 (2021).

Prezado, Y. et al. Spatially fractionated radiation therapy: a critical review on current status of clinical and preclinical studies and knowledge gaps. Phys. Med. Biol. 69, 10TR02 (2024).

Potiron, S. et al. The significance of dose heterogeneity on the anti-tumor response of minibeam radiation therapy. Radiother. Oncol. 201, 110577 (2024).

Tubin, S. et al. Novel unconventional radiotherapy techniques: Current status and future perspectives—report from the 2nd international radiation oncology online seminar. Clin. Transl. Radiat. Oncol. 40, 100605 (2023).

Trappetti, V. et al. Synchrotron microbeam radiation therapy for the treatment of lung carcinoma: a preclinical study. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 111, 1276–1288 (2021).

Grams, M. P. et al. Minibeam radiation therapy treatment (MBRT): commissioning and first clinical implementation. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 120, 1423–1434 (2024).

McMillan, M. T. et al. Spatially fractionated radiotherapy in the era of immunotherapy. Semin. Radiat. Oncol. 34, 276–283 (2024).

Shutaywi, M. & Kachouie, N. N. Silhouette analysis for performance evaluation in machine learning with applications to clustering. Entropy 23, 759 (2021).

Nakayama, M. et al. Dose estimation of normal brain tissue tolerance for microbeam radiation therapy. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 90, S804 (2014).

Rivera, J. N. et al. Conventional dose rate spatially-fractionated radiation therapy (SFRT) treatment response and its association with dosimetric parameters—a preclinical study in a Fischer 344 rat model. PLoS ONE 15, e0229053 (2020).

Larrea, L. et al. Lattice radiotherapy (LRT)-spatially fractionated radiotherapy (SFRT) in advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): early experience. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 111, e443 (2021).

Xu, P. et al. Spatially fractionated radiotherapy (Lattice SFRT) in the palliative treatment of locally advanced bulky unresectable head and neck cancer. Clin. Transl. Radiat. Oncol. 48, 100830 (2024).

Li, H. et al. Overview and recommendations for prospective multi-institutional spatially fractionated radiation therapy clinical trials. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 119, 737–749 (2024).

Moustacchi, E. DNA damage and repair: consequences on dose-responses. Mutat. Res. 464, 35–40 (2000).

Hu, S. et al. The dose-related plateau effect of surviving fraction in normal tissue during the ultra-high-dose-rate radiotherapy. Phys. Med. Biol. 68, 185004 (2023).

Twyman-Saint Victor, C. et al. Radiation and dual checkpoint blockade activate non-redundant immune mechanisms in cancer. Nature 520, 373–377 (2015).

Gago-Arias, A. et al. Evaluation of indirect damage and damage saturation effects in dose–response curves of hypofractionated radiotherapy of early-stage NSCLC and brain metastases. Radiother. Oncol. 161, 1–8 (2021).

Ruggieri, R. et al. Optimal dose and fraction number in SBRT of lung tumours: a radiobiological analysis. Phys. Med. 44, 188–195 (2017).

Guerrero, M. & Carlone, M. Mechanistic formulation of a lineal-quadratic-linear (LQL) model: split-dose experiments and exponentially decaying sources. Med. Phys. 37, 4173–4181 (2010).

Guerrero, M. & Li, X. A. Extending the linear-quadratic model for large fraction doses pertinent to stereotactic radiotherapy. Phys. Med. Biol. 49, 4825–4835 (2004).

Song, C. W. et al. Indirect tumor cell death after high-dose hypofractionated irradiation: implications for stereotactic body radiation therapy and stereotactic radiation surgery. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 93, 166–172 (2015).

Song, C. W. et al. Biological principles of stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) and stereotactic radiation surgery (SRS): indirect cell death. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 110, 21–34 (2021).

Park, H. J. et al. Radiation-induced vascular damage in tumors: implications of vascular damage in ablative hypofractionated radiotherapy (SBRT and SRS). Radiat. Res. 177, 311–327 (2012).

Gao, H. Q. et al. How to deal with the relationship between hypoxia and radiotherapy in the hypofractionated radiotherapy era?. Int. J. Radiat. Res. 19, 759–769 (2021).

Song, C. W. et al. Preferential tumor vascular damage is the common antitumor mechanism of high-dose hypofractionated radiation therapy: SABR, spatially fractionated radiation therapy, and FLASH radiation therapy. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 117, 701–704 (2023).

Whitaker, J., Mak, R. H. & Zei, P. C. Non-invasive ablation of arrhythmias with stereotactic ablative radiotherapy. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 32, 287–296 (2022).

Tsai, J. H. et al. Ionizing radiation inhibits tumor neovascularization by inducing ineffective angiogenesis. Cancer Biol. Ther. 4, 1395–1400 (2005).

Chen, F.-H. et al. Radiotherapy decreases vascular density and causes hypoxia with macrophage aggregation in TRAMP-C1 prostate tumors. Clin. Cancer Res. 15, 1721–1729 (2009).

Meijer, T. W. H. et al. Targeting hypoxia, HIF-1, and tumor glucose metabolism to improve radiotherapy efficacy. Clin. Cancer Res. 18, 5585–5594 (2012).

Griffin, R. J. et al. Microbeam radiation therapy alters vascular architecture and tumor oxygenation and is enhanced by a galectin-1 targeted anti-angiogenic peptide. Radiat. Res. 177, 804–812 (2012).

Bertho, A. et al. Evaluation of the role of the immune system response after minibeam radiation therapy. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 115, 426–439 (2023).

Han, Y. J. et al. The VEGF-Hypoxia signature is upregulated in basal-like breast tumors from women of African ancestry and associated with poor outcomes in breast cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 30, 2609–2618 (2024).

Babcock, K. et al. Collimator design for experimental minibeam radiation therapy. Med. Phys. 38, 2192–2197 (2011).

Kundapur, V., Torlakovic, E. & Auer, R. N. The story behind the first mini-beam photon radiation treatment: What is the mini-beam and why is it such an advance?. Semin. Radiat. Oncol. 34, 337–343 (2024).

Deman, P. et al. Monochromatic minibeam radiotherapy: theoretical and experimental dosimetry for preclinical treatment plans. Phys. Med. Biol. 56, 4465 (2011).

Large, M. J. et al. Hydrogenated amorphous silicon high flux x-ray detectors for synchrotron microbeam radiation therapy. Phys. Med. Biol. 68, 135010 (2023).

Suo, S. et al. Diffusion-weighted MRI for predicting pathologic response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer: evaluation with mono-, bi-, and stretched-exponential models. J. Transl. Med. 19, 236 (2021).

Jarrett, A. M. et al. Quantitative magnetic resonance imaging and tumor forecasting of breast cancer patients in the community setting. Nat. Protoc. 16, 5309–5338 (2021).

Yin, J. et al. Pattern recognition of microcirculation with super-resolution ultrasound imaging provides markers for early tumor response to anti-angiogenic therapy. Theranostics 14, 1312 (2024).

Fisk, M. et al. Development and optimisation of grid inserts for a preclinical radiotherapy system and corresponding Monte Carlo beam simulations. Phys. Med. Biol. 69, 055010 (2024).

Johnstone, C. D. & Bazalova-Carter, M. A review of small animal dosimetry techniques: image-guided and spatially fractionated therapy. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2630, 012013 (2023).

Chan, M. F. et al. Energy dependence of the Gafchromic EBT4 film: dose-response curves for 70 kV, 6 MV, 6 MV FFF, 10 MV FFF, and 15 MV x-ray beams. Med. Phys. 50, 3738–3745 (2023).

Niroomand-Rad, A. et al. Report of AAPM Task Group 235 radiochromic film dosimetry: an update to TG-55. Med. Phys. 47, 5986–6025 (2020).

Bazyar, S. et al. Minibeam radiotherapy with small animal irradiators; in vitro and in vivo feasibility studies. Phys. Med. Biol. 62, 8924 (2017).

Percie du Sert, N. et al. The ARRIVE guidelines 2.0: updated guidelines for reporting animal research. J. Cereb. Blood Flow. Metab. 40, 1769–1777 (2020).

Bazyar, S. et al. Immune-mediated effects of microplanar radiotherapy with a small animal irradiator. Cancers 14, 155 (2021).

Gatenbee, C. D. et al. Virtual alignment of pathology image series for multi-gigapixel whole slide images. Nat. Commun. 14, 4502 (2023).

Wu, J. et al. Radiological tumour classification across imaging modality and histology. Nat. Mach. Intell. 3, 787–798 (2021).

Syed, A. K. et al. Multiparametric analysis of longitudinal quantitative MRI data to identify distinct tumor habitats in preclinical models of breast cancer. Cancers 12, 1682 (2020).

Kim, D., Langmead, B. & Salzberg, S. L. HISAT: a fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat. Methods 12, 357–360 (2015).

Love, M. I., Huber, W. & Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 15, 1–21 (2014).

Sun, J., Nishiyama, T., Shimizu, K. & Kadota, K. TCC: an R package for comparing tag count data with robust normalization strategies. BMC Bioinform. 14, 1–14 (2013).

Acknowledgements

This project received funding from the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (ZYGX2021YGCX001); the Health Commission of Sichuan Province (ZH2023–801, 24QNMP038); the Chengdu Technology Bureau (2024-YF05-02230-SN); and the Scientific Research Project of Sichuan Medical Association (2024HR15).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.C., J.L., S.Z., and Z.F. designed this study. Z.F., X.Z., P.Z., J.C., and X.C. performed all the experiments; Z.F., C.G., L.Q., N.H., T.J., and Y.M. analyzed and interpreted the data. Z.F. drafted the manuscript; M.C., J.L., S.Z., and Z.F. revised the manuscript. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fang, Z., Zhou, X., Zou, P. et al. Minibeam radiation therapy remodels tumor microenvironment and suppresses HIF-1α/VEGFR axis to overcome radioresistance in triple-negative breast cancer. npj Precis. Onc. 9, 401 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41698-025-01178-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41698-025-01178-z