Abstract

Precision oncology leverages real-world data, essential for identifying biomarkers and therapies. Large language models (LLMs) can aid at structuring unstructured data, overcoming current bottlenecks in precision oncology. We propose a framework for responsible LLM integration into precision oncology, co-developed by multidisciplinary experts and supported by Cancer Core Europe. Five thematic dimensions and ten principles for practice are outlined and illustrated through application to uterine carcinosarcoma in a thought experiment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Large Language Models (LLMs) have transformed human perception of artificial intelligence (AI) primarily due to their ability to respond and reason in human language. The development of user-friendly interfaces has made LLMs accessible to non-technical users. In medicine, these advancements open opportunities, as LLMs can support clinicians by providing quick access to information, assist in clinical decision-making, and can take over simple, repetitive tasks such as documentation, thereby freeing up valuable time for healthcare professionals1,2. The capacities of LLMs extend beyond classical AI approaches that primarily analyze or classify structured data, as they combine content generation with the analysis and classification of unstructured data. More recently, multimodal models, which can process images and text simultaneously, have shown impressive results in simulated diagnostic scenarios3,4.

However, a recent systematic review found that only 5% of researchers utilize real-world patient data to train and evaluate LLMs, instead, most rely on synthetic datasets, which are easier to access and avoid data privacy concerns. Due to the limited real-world implementation of LLMs in clinical routines, little real-world evidence has been generated to confirm the theoretical potential of LLMs in real-world healthcare settings5,6. This current lack of evidence hinders the adoption of LLMs in routine clinical care. To fully unlock their potential for everyday healthcare, validation studies using real-world patient data are crucial to advance both the field and its clinical applications. Navigating the responsible use of real-world patient data for LLMs in complex health contexts benefits from practice-oriented guidelines to avoid uncertainties and navigate the responsible use of such data for LLMs in complex healthcare contexts.

In oncology, the challenges associated with using real-world patient data are particularly complex. Oncology clinical decision-making often requires integrating multimodal data into a comprehensive and individualized treatment plan. Currently, physicians in precision oncology carry out a range of labor-intensive tasks, such as creating and interpreting medical reports, annotating molecular mutations, manually curating scientific evidence, and interpreting biomarker profiles. These time-intensive processes, e.g., of translating genomic data into clinically actionable treatment plans7, delay the timely initiation of targeted therapies8, and thereby adversely impact patient outcomes.

Clinical Decision Support Systems (CDSS) can leverage LLMs to overcome bottle necks in precision oncology: LLMs can extract structured information from unstructured patient data, enabling clinicians to make faster, more informed decisions (see Fig. 1). With this capability LLMs offer a range of applications across the diagnostic and therapeutic process in precision oncology, supporting tasks such as literature review, patient chart reviews, and biomarker interpretation, risk stratification, treatment recommendations and clinical trial matching (Fig. 1). These capabilities streamline workflows, enhance efficiency, and improve patient-centered care by minimizing delays in decision-making.

LLMs can assist clinicians and related professions in the field of precision oncology with various tasks to eventually develop actionable treatment plans for patients. These models can be tailored to support time-consuming tasks, thereby improving resource management and enhancing the quality of care.

As LLMs become more prevalent in this field, it is essential to address both the advantages and limitations of using real-world data – an issue increasingly acknowledged by clinicians, patients, and policymakers.

Responsible AI (RAI) frameworks consider the ethical, legal, scientific, and clinical aspects necessary for the ethically sound development and deployment of AI9,10. They are essential to ensure the trustworthy application of AI in clinical settings due to the sensitivity of identifying data and the vulnerability of patients. As AI cannot be held accountable for clinical decisions, human operators retain accountability and may be legally liable for acting on AI-generated recommendations, especially when those recommendations do not align with established standard procedures11. This is crucial in precision oncology, where off-label treatments are often the only option for rare and treatment-resistant conditions lacking established guidelines.

To provide practice-oriented guidance for the responsible use of real-world data in LLMs for precision oncology, we designed a framework of five overarching dimensions to serve as a foundation for practical recommendations. Building on this, we developed ten principles to guide the practical implementation of LLM-based CDSS in precision oncology. We extend this with an example use case of a patient with uterine carcinosarcoma, a rare disease lacking established guidelines, where time-intensive manual research can be significantly accelerated using LLMs to improve patient outcomes. By providing practice-oriented guidance grounded in multidisciplinary experience and research, we aim to ensure that LLM-based CDSS leveraging real-world patient data not only achieve high standards of clinical efficacy but also adhere to ethical and legal requirements, ultimately bridging the gap between AI’s theoretical potential and its practical application in healthcare.

Methods

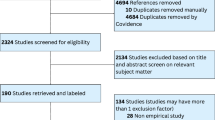

Our literature review identified the need for specific recommendations on using real-world patient data responsibly in generative AI applications for CDSS in precision oncology. We then conducted an explorative literature review to identify a framework of dimensions for the responsible use of LLMs in CDSS in precision oncology. We subsequently held group discussions with an interdisciplinary team of ten experts in clinical oncology, AI, digital health, policy, and ethics, which led to the refinement of the five dimensions. Next, we identified ten practice-oriented principles based on our practical experience and insights from the literature, which should guide practitioners to implement all five dimensions.

To develop the principles, the group allocated each of the principles to a team of two authors according to their expertise. The principles were developed between March 2024 and August 2024. Regular consensus meetings allowed the group to discuss and agree on the content of the text sections. In July 2024, author groups were reassembled to review and edit the manuscript in new teams, providing a second perspective. We contacted Cancer Core Europe for external validation of the manuscript through renowned experts from their network working at the intersection of AI and precision oncology. Cancer Core Europe is a consortium of seven leading cancer centers across Europe, aiming to advance cancer research and improve therapeutic outcomes through collaborative, cross-institutional efforts. After meeting consensus within the team of ten, an additional seven authors from Cancer Core Europe (CCE)12 reviewed the manuscript between November 2024 and January 2025, revising each section until consensus was reached within the extended international team. To evaluate consensus on the relevance of the thematic dimensions for each principle, eleven available experts from our extended author group participated in an online survey (Google Forms) conducted after the formulation of the ten user-oriented principles. Using a 5-point Likert scale, they rated the extent to which each principle reflected aspects of the five thematic dimensions. The importance of each dimension within the respective principles was evaluated and measured quantitatively and is illustrated as a spider-plot in Fig. 3. After final review of the finalized text, figures, and tables by all contributing authors, CCE was asked to endorse the manuscript. We provide a detailed overview of the writing process in Fig. 2.

Structured development of a position paper on the responsible use of LLMs in precision oncology based on expert discussions and iterative consensus-building. An interdisciplinary German team of experts drafted five dimensions, each representing a thematic complex of responsible LLM-use for precision oncology with real-world data. From these more abstract complexes, ten practice-oriented, actionable principles were developed deductively through group discussions and repeated manuscript reviews. The manuscript underwent two working processes: initial drafting, team-based revisions, and consensus formation, followed by validation through discussions with local center experts within Cancer Core Europe (CCE). Final approval was granted by the CCE Board to ensure alignment with institutional and scientific standards.

Five dimensions of responsible AI for using real-world data with LLM for Precision Oncology

Our five dimensions represent large thematic complexes concerning the responsible use of LLMs with real-world patient data in precision oncology. For each dimension, we briefly summarize relevant concepts and considerations regarding the responsible implementation of generative AI with real-world patient data. We outline the relevance and scope of each dimension and highlight important contextual factors, including applicable regulations, standards, and guidelines.

Dimension 1: Adherence to medical standards

Medical standards are striving to uphold a “standard of care”, as the established treatment that is beneficial for patients and subject to ongoing scientific evaluation13. Consensus on medical standards is, in part, summarized in medical guidelines. The constant evolution of medical standards is mirrored in the growing body of literature and the updating of medical guidelines. Generative AI in the form of LLMs holds the potential to contribute to the evolution of these standards by structuring previously inaccessible unstructured information, such as doctors’ letters, pathology reports, and clinical images for structured evaluation14 and facilitating the review of recent literature. There can be a bidirectional interaction between evolving medical standards and AI: On the one hand, principles of RAI can help ensure the implementation of medical standards in LLMs. On the other hand, LLMs can help advance medical standards, especially where they are undefined (e.g., in precision oncology). LLM systems must undergo critical evaluation of their adherence to medical standards, ensuring safety, efficacy, and relevance in real-world settings. This includes medical device certification, which ensures that LLMs in precision oncology comply with medical standards and safeguard patient safety.

Dimension 2: Balancing technological benefits and risks

LLMs are able to quickly and efficiently extract information from unstructured text, image, audio, and video files, and create new, human-like content. This makes them valuable for managing the exponentially growing volume of unstructured and unlabeled information generated in Electronic Health Records (EHR) each day15. This is especially relevant for precision oncology, where analysis of extensive data sources becomes essential for tailoring treatments when standard guidelines fail or are nonexistent.

Technical designs need to carefully balance the benefits and risks of new technologies. For LLMs, this includes weighing their ability to analyze unstructured textual data quickly and reliably against shortcomings such as ‘hallucinations’, which are factually incorrect statements, that are hard to detect as such16. When technology leads to risks, these risks must be acknowledged and addressed17, also involving structured assessments, such as context-specific technology impact evaluations18.

Dimension 3: Compliance with regulatory frameworks

Laws and regulations mandate medical standards and provide guidance on handling technology risk. Examples are the Medical Device Regulation (MDR) and the In Vitro Diagnostic Regulation (IVDR) in the European Union, and the Federal Drug Administration (FDA) and the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) in the United States19,20. Additionally, the newly published EU AI Act mandates implementation of controls for AI-products, based on the risk level of their application contexts21. Many LLM-based use cases in medicine fall under the “high risk” category as they support clinicians and patients to make healthcare decisions. Any modification or in-house operation of a general-purpose LLM can lead to clinics becoming AI system providers22. While the AI Act gradually comes into full effect by 2027, business and IT decision makers in healthcare institutions were required to become familiar with the obligations of AI system providers and implement relevant governance frameworks and controls already by August 202623.

Dimension 4: Respecting ethical considerations

Ethical considerations form another thematic complex, inherently relevant to the responsible use of LLMs in precision oncology. Ethical standards and guidelines in medicine give the highest priority to promoting patient well-being24,25,26,27,28. Historical examples underscore the importance of critical ethical guidance in research and development at this29. In AI for precision oncology, AI-specific novel ethical frameworks are increasingly established30,31,32,33, while a broad range of ethical principles has already been articulated in the existing literature31,34. New ethical considerations and principles add perspectives, while traditional perspectives remain valuable, e.g., reflecting the four principles of biomedical ethics by Beauchamp and Childress27,32. Novel near-term and long-term ethical concerns have been named, and including bias, fairness as important considerations, calling for responsible AI9. As a new concept developing ethical standards for the creation of responsible AI-systems, RAI has emerged from related scientific fields35. To ensure that algorithms comply with ethical requirements, embedding ethicists in development teams has been suggested36. In the context of precision oncology, the rapid technological evolution of LLMs continues to raise new ethical questions, especially as the race for advances in AI accelerates. Our team of authors proposes incorporating established ethical views alongside emerging ethical considerations when developing LLMs that utilize real-world patient data.

Dimension 5: Providing scientific and clinical benefit

The increase of precision in medicine is data-driven, continuously integrating insights from biomedical research and health information. By structuring, synthesizing, validating, and analyzing this abundance of information across fragmented data sources, AI can substantially contribute and thereby advance precision medicine across healthcare sectors37,38,39,40 and accelerate scientific innovation4,41. Aims to prevent risks of AI in research and clinical applications, like dual-use potentials and data-safety concerns, are mirrored in extensive governance frameworks, such as the GDPR42, EU AI Act21, or DSA/DMA, partially hindering technological advancement43. Additional considerations for clinical usability include social and financial factors, such as fostering public acceptance through explainability and education, and calculating the increasing costs of in-depth testing and refinement for adequate monitoring43. These factors are particularly relevant in the healthcare sector, where a substantial portion of funding comes from social systems. While the successful implementation of LLMs in science and clinical routine might eventually yield scientific and clinical benefits, including returns on investment, increased accessibility of precision oncology for patients44,45 and potentially incentivizing further LLM-centered research, these factors must be carefully weighed.

Ten principles as practical guidance for the responsible use of LLMs in precision oncology

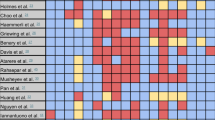

Drawing on the content identified as relevant within the thematic dimensions, we proceed to curate ten user-oriented principles for practical guidance. Each principle presents a concise collection of relevant aspects from the dimensions to aid at the actual application of generative AI with real-world patient data in precision oncology. The contribution of the overarching dimensions to each respective principle, as assessed by the experts in our author team, is mapped in Fig. 3. To provide relevant practice-oriented guidance, we contextualize collections of relevant aspects within current challenges related to the practical implementation of LLMs in precision oncology use cases involving real-world patient data. We intentionally permit individual aspects from the thematic dimensions to be addressed across different principles, as the thematic dimensions may offer different facets, depending on the principle’s narrower thematic focus, all of which can contribute to directive recommendations.

Evaluation of the ten user-oriented principles for applying LLMs in precision oncology based on their relevance across five thematic dimensions. Participating experts were asked to assess the contribution of each dimension to the respective principle: adherence to medical standards, technological benefits and risks, regulatory framework, ethical considerations, and scientific and clinical benefit, based on their professional experience. The mapping took place after the formulation of the principles was completed, to check for consensus on the relevance of the principle across thematic dimensions. For the mapping, the collection of aspects of each principle was rated dimension-wise for relevant overlap between principle and dimension by using a 5-point Likert scale.

Principle 1: Data provenance and quality

Data provenance is defined as “information about entities, activities, and people involved in producing a piece of data or thing, which can be used to form assessments about its quality, reliability or trustworthiness”46. Accordingly, LLMs, like other forms of ML systems, leveraging real-world patient data for precision oncology, require rigorous standards for reporting on data sources, data composition, training data, data collection, data quality metrics as well as bias and variability, including data sources and demographic information on patients (see Table 1 for detailed recommendations).

Collecting provenance and quality information of all data used as input for inference, e.g., from information systems or prompts, their pre-processing steps, like de-identification, normalization, or coding/annotation, and corresponding results, are minimal necessary requirements for inference audit trails.

Principle 2: Bias and fairness

Fairness in connection with avoidance of bias is are core value of medical ethics24,27 and therefore a critical concept to consider for responsible use of LLMs in precision oncology. Both aim to achieve increased transparency and equitable healthcare outcomes across diverse populations. At this, fairness also emphasizes health equity, implying fair access to health resources from the outset. In computational health, diverse definitions of fairness are used47, with many criteria for fairness being observational, such as examining the distribution of factors to decide about access to precision oncology47. Concepts of fairness are often conflicting, e.g., conflicts between individual and group fairness47 necessitating balancing principles of group fairness, like demographic parity (distribution of resources based on a singular criterion, e.g., gender), with fairness from the individual’s point of view. However, this approach of deliberate differentiation between groups can result in disadvantages for singular individuals, which can be addressed by mechanisms like equality of odds48. Apart from known group differentiators, subconscious discrimination in training data for models can lead to algorithmic bias, necessitating critical interpretation, evaluation, and monitoring, including limiting use to suitable application contexts and implementing regular, sample-based human reviews of AI suggestions49.

Principle 3: Explainability

Maximizing the explainability of generative AI enhances transparency and fosters trust among medical professionals. Many AI models, particularly deep learning architectures, are often criticized for their “black box” nature22, which is critical in the sensitive context of precision oncology, when the rationale behind their predictions cannot be tracked by the responsible clinicians.

To address this challenge at least partially, researchers have developed explainable AI (XAI) techniques helping users understand why an AI model came to a certain conclusion50,51.

A notable example is a study by Kuenzi et al., which demonstrated the potential of XAI in precision oncology by developing an interpretable deep learning model for predicting drug responses in cancer patients. This model achieved high accuracy and provided explanations traceable and consistent with existing biological knowledge, thereby enhancing its clinical utility52.

However, trade-offs between explainability and model performance should be acknowledged53,54. Inherently explainable models can be limited by their susceptibility to confounders, while post-hoc explainability techniques often fail to transparently reveal the reasoning behind a model’s decisions, potentially misleading users. These methods lack performance guarantees, frequently rely on approximations, and may even reduce model accuracy. Crucially, while XAI methods provide descriptive insights into model behavior, they do not offer normative evaluations of whether that behavior is justified or appropriate. Attempting to bridge this gap through intuition risks introducing additional biases. Moreover, explainability can paradoxically foster over-reliance on AI systems, potentially reducing user vigilance and critical evaluation. To ensure the safety, efficacy, and fairness of AI systems, thorough validation across diverse populations remains the most reliable approach. XAI should primarily serve as a tool for developers and auditors to probe and refine models, rather than as a justification for individual decisions55. Therefore, caution is warranted when interpreting explainability outputs as indicators of clinical or operational correctness. For generative AI models, XAI can involve citing the sources of their recommendations and enabling users to validate outcomes. Techniques like Retrieval Augmented Generation (RAG) technically provide relevant documents as lookup data for the model and plays a crucial role in advancing the explainability, reliability, and auditability of AI-assisted clinical decision-making1.

Principle 4: Auditability

Auditability is crucial for ensuring the accountability of AI systems in precision oncology. It is also a key requirement in much of the prevailing regulation governing the use of AI in medicine (see Regulatory Frameworks). This involves the ability to track and review the decision-making process of AI models, identify potential sources of error, and correct them promptly. To achieve auditability, AI systems should incorporate logging and monitoring mechanisms that systematically capture relevant data throughout the decision-making process, such as source document references, model outputs, and precise timestamps. This data can then be analyzed to assess the performance of the model, detect anomalies, and pinpoint areas for improvement56.

Principle 5: Patient consent, de-identification, and privacy

Since the latter half of the 20th century, patient consent and privacy considerations have been considered essential for respecting patient autonomy and physician beneficence57.

The clinical and scientific use of genetic data is especially sensitive due to its highly personal nature. Meaningful consent to use genetic data requires patients to understand associated privacy concerns and must enable them to make informed decisions58. To mitigate patient privacy concerns reasonably, anonymization and pseudonymization are common data protection methods from the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR)59. Pseudonymization, relying on cryptographic algorithms or lookup tables, renders patients theoretically still identifiable59. Anonymization, involving removing all personally identifiable information (PII), is preferred with respect to data protection for patients, as it theoretically renders re-identification impossible60. However, true anonymization is challenging, especially for mutational information, since indirect identifiers like age, location, and family and medical history can still enable reidentification61. Simply omitting these data points may lead to increased information loss62,63. Thorough selection of anonymization strategies may contribute to acceptable information loss, only mildly affecting data utility62,63. Anonymization methods should be evaluated across diverse data streams and demographic groups, with detailed documentation of the applied techniques.

Local operation of AI models and protected data storage may enhance data protection, even if full anonymization is not feasible54. Technological evolution may necessitate clarifications and adaptations of data protection regimes where appropriate, especially if they only add complexity without enhancing data security.

Principle 6: Infrastructure Robustness and Cyber Security

For the protection of patient data and patient well-being robust infrastructure is a key principle of applying generative AI to real-world patient data, necessitating cybersecurity safeguards and regular internal and external audits. These requirements are enforced by the current regulation21. In accordance with data minimization, only data that is strictly necessary for the given use case should be stored59. Practitioners need to ensure that they use tested and validated software and infrastructure and implement robust governance, risk, and compliance (GRC) frameworks. Operators of an AI system need control over stored data, and local data processing (without internet access) is therefore preferable. For good research practice, adherence to FAIR principles (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable) is beneficial64,65.

Principle 7: Continuous evaluation and monitoring

In the SARS-CoV2 pandemic, quickly emerging epidemiological changes in health data were seen, leading to dataset shifts. AI may struggle to recognize such deviations, requiring human supervision to ensure AIs work in situations that differ from their training situations66. Due to the highly sensitive applications of generative AI in precision oncology, continuous, multifaceted evaluation and monitoring are required, considering the specifics of the respective application context67.

Molecular Tumor Boards (MTB) are a key element of precision oncology68 and see benefits from integration of AI in the field, e.g., for literature search and synthesis69. Legal requirements such as the GDPR42 and EU AI Act21, regulate generative AI applications in precision oncology, mandating mechanisms for evaluation and monitoring for high-risk applications. These expectations, next to evaluating real-world performance, can be met by implementing technical measures for monitoring the performance of (generative) AI applications, leveraging established metrics such as Ragas70 or BERTScore71. Additionally, AI system recommendations should be reviewed by clinicians (human-in-the-loop), with comprehensive sample-based reviews34,72.

Principle 8: Validation, governance, regulatory compliance

AI has increasingly been focused on as a topic in jurisdiction, with growing regulations acknowledging this trend22. The EU AI Act is a landmark in international regulation, becoming mandatory in August 202621,73. Complexity of legal requirements, particularly in data protection74, complicate processes for researchers and may incentivize the development of lower-risk medical AI-devices rather than complex solutions22.

Thorough validation is essential before integrating LLMs into clinical workflows, as incorrect AI outputs may lead to considerable risks for individuals75. This has led to calls for transparency and accountability in AI prosecution76. Current literature on liability discusses factors influencing physicians’ accountability, such as increased responsibility when following more unconventional AI recommendations11. Edge cases like this may arise more naturally in precision oncology, where standard treatments are either exhausted or unavailable77. Researchers suggest resolving these issues by allowing for moral customization of AI settings by patients, returning autonomy to the individual78. Quick responses of legislators to trends and innovations may be crucial to protect patients, their families, clinicians, and researchers from uncertain legal situations.

Principle 9: Human AI collaboration

Humans and AI are projected to increasingly collaborate on clinical tasks79,80. As AI solutions become more advanced, it is crucial to ensure that these technologies respect human uniqueness and dignity, including awareness on the influences of AI on users31. This implies effective and secure integration of AI applications in clinical routine, enhancing, rather than replacing, the expertise of physicians and providing explainable and responsible AI applications for patients30,31,32,33. Currently established principles lack clarity in guiding Human AI Collaboration30. To achieve an appropriate balance between uncritical acceptance of AI proposals and overt distrust of beneficial AI applications81, AI outputs require human validation during model development and in every specific case of use.

Currently, AI validation and training rely heavily on human-annotated data and feedback, especially for LLMs as they generate non-reproducible, non-deterministic output82,83.

Risks can be mitigated with “human-in-the-loop” refinement69. In precision oncology, this implies ensuring alignment with clinical requirements and by integrating physician specialist domain knowledge. This requires fine-tuning, additional prompt engineering, or incorporating trusted (online-) data sources via RAG84 or In-Context Learning85.

Principle 10: Education and Awareness

Even though easy and comfortable to use86,87, AI applications in vulnerable patient groups, like in precision oncology, necessitate specific education for all stakeholders, rather than leaving their responsible use primarily to interested early adopters in the field, creating awareness for potential risks as well as opportunities. Education can leverage AI for teaching directly, enabling hands-on learning concepts, together with immersive learning methods, which have been shown to outperform established teaching concepts88. Education of patients, physicians, and researchers on AI is crucial for valuable and responsible integration of LLM in clinical applications, and physicians’ training should meet the standards of medical education89. This comprises learning on and through AI-tools in three primary ways: directly in the teaching process, as a supplementary tool for educators, and by empowering physicians in training90. Since interactions with AI may involve real-world data and personal information of all participants, effective measures for data and privacy protection are essential to ensure learners’ legal integrity91.

Thought experiment: Blueprint for LLMs in Clinical decision support systems for precision oncology

To validate the usability of the ten principles for the application of generative AI for precision oncology comprehensively, we have applied them to a Rare Gynecological Tumor (RGT) use case.

RGTs present a major challenge in oncology. In gynecology, they account for over 50% of all malignancies and include more than 30 distinct histologic subtypes for this specialty alone, with an estimated 80,000 new cases annually in Europe92. The rarity of RGTs, with an incidence of less than 6 per 100,000 women, due to limited patient numbers for each subtype, hinders the development of robust clinical practice guidelines. Consequently, treatment decisions often rely on less standardized approaches, such as retrospective studies, case reports, expert opinions, or extrapolating data from analogous tumors in other anatomical sites93.

Uterine carcinosarcoma (UCS) exemplifies the challenges in managing rare tumor entities. Despite established endometrial cancer treatment protocols, UCS remains a distinct, aggressive malignancy with limited therapeutic options. This RGT is frequently excluded from clinical trials, contributing to a poor prognosis characterized by low survival rates and high recurrence. Advanced UCS management is further complicated by treatment resistance, lack of standardized second-line therapies, and poor outcomes with subsequent treatment lines94. While the molecular characterization of UCS offers potential therapeutic targets, translating genomic data into effective clinical strategies remains challenging. Here, we want to introduce LLM-enabled CDSS applications with the potential to improve disease management in a UCS patient who has progressed on first-line therapy.

We provide a case-based workflow, especially underscoring the critical role of real-world patient data integration in the development and refinement of LLMs for precision oncology.

Thought experiment and Workflow for the responsible use of LLMs in Precision Oncology

Upon admission to an oncological care unit of a UCS-patient with progressive disease after first-line treatment, patient data would be collected from existing records and through a detailed anamnesis, ensuring adequate data provenance. Meaningful Informed Consent should be obtained from the UCS patient, ensuring understanding of the relevant risks and benefits of Molecular Profiling and LLM use.

Annotation of real-life data and thorough literature research, together with (AI-supported) diagnostic assessment, is necessary at this step. This process is time-consuming, resource-intensive, and prone to suboptimal patient care due to the absence of standardized treatment guidelines and the challenges associated with manual literature review. At this, a trained professional can leverage an LLM-enabled CDSS - respecting medical standards, data protection requirements, as well as ethical requirements to alleviate these tasks. By instantly analyzing vast amounts of real-world patient data, streamlining literature reviews, and aiding in the generation of treatment plans, a CDSS offers a potential solution to overcome the existing bottlenecks at this point and improve patient care.

The developed treatment suggestions from the annotation process facilitated through this approach form the basis for Shared Decision-Making (SDM) on identified treatment options. At this step, patients must be informed and educated about the use of CDSS and the therapeutic options. LLMs can support patient–trial matching, if trials are available, or, otherwise, can assist in reviewing current evidence to suggest treatments, including potential off-label options for rare diseases. The paucity of UCS-specific clinical trials usually necessitates off-label treatment decisions based on the available evidence. Therefore, inclusion into clinical trials/a Cost Coverage Request is issued, again with the help of an LLM-enabled CDSS, and finally, an actionable treatment plan is developed. The treatment plan is executed, and the documented results are analyzed with the support of LLMs that strictly adhere to legal and ethical requirements, avoid bias to the extent possible, and enable clinicians and researchers to interact in a responsible, efficient way with the AI. Clinical outcomes are documented using LLMs that strictly follow data protection and ethical requirements. The resulting multimodal data of a variety of patients is then analyzed and used to enhance LLM performance in supporting effective UCS treatment. This blueprint use case of a gynecological precision oncology patient with uterine carcinosarcoma serves to highlight a framework for the application of similar methodologies to refractory diseases for other fields of precision oncology. The exemplary workflow is illustrated in the flowchart in Fig. 4.

Structured framework (blueprint) to the responsible integration of LLMs in precision oncology workflows. LLMs are applied across data extraction, multi-modal data analysis, and clinical decision-making to process laboratory reports, unstructured clinical data, and literature, support data analysis and explainability, and assist in cancer risk stratification, quality, patient privacy, explainability, auditability, and regulatory compliance, reflects their contextual relevance across workflow components to ensure responsible LLM deployment in clinical and research settings.

With this thought experiment, we demonstrate how rigorously applying our design principles for RAI in CDSS ensures that an LLM will address all five dimensions of RAI in precision oncology with real-world data. The ensuing system adheres to medical standards, balances technology benefits and risks, complies with regulatory frameworks, respects ethical considerations, and ensures that the system will provide benefits to patients, clinicians, and the scientific community. A detailed checklist for the application of RAI in comparable Precision Oncology settings is provided in the Supplement (Supplement 1).

In our thought experiment, we propose a workflow that operationalizes our framework of five dimensions and ten practice-oriented principles for real-world applications. The UCS patient case can be readily replaced by anonymized real-world cases, such as those from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) UCS cohort established in the United States95,96.

While we highlighted the principal applicability of our framework in precision oncology contexts, we note the limitations of our framework. The thematic dimensions may be broadly transferable to other domains of precision medicine, such as neurology; the principles reflect context-specific guidance tailored to precision oncology. Further refinement and adaptation will be required to apply the principles to other medical fields. Also, given the continuous evolution of the field, critical engagement with ongoing developments within the context of this framework remains essential.

Conclusion

Generative AI in oncology holds potential for improving patient, scientific, and medical outcomes. Responsibly integrating real-world patient data is required to fully realize this potential. Recent advancements have made AI more accessible and user-friendly, but its responsible use in precision oncology requires comprehensive education for all stakeholders. This review explores five dimensions for AI implementation: adherence to medical standards, promotion of scientific and medical benefits, consideration of technological advantages and risks, regulatory frameworks, ethical considerations; as well as ten guiding principles for the application of generative AI in precision oncology: Data Provenance and Quality, Bias and Fairness, Explainability, Auditability, Patient Consent, De-identification and Privacy, Infrastructure Robustness and Cybersecurity, Continuous Evaluation and Monitoring, Validation, Governance and Regulatory Compliance, Human-AI Collaboration, Education and Awareness. These principles will assist practitioners in integrating generative AI within LLMs for precision oncology, using real-world patient data in alignment with RAI principles.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

References

Ferber, D. et al. GPT-4 for information retrieval and comparison of medical oncology guidelines. NEJM AI 1, AIcs2300235 (2024).

Zakka, C. et al. Almanac—retrieval-augmented language models for clinical medicine. NEJM AI 1, AIoa2300068 (2024).

Buckley, T., Diao, J. A., Rodman, A. & Manrai, A. K. Accuracy of a vision-language model on challenging medical cases. arXiv preprint arXiv:2311.05591 (2023).

Eriksen, A. V., Möller, S. & Ryg, J. Vol. 1 AIp2300031 (Massachusetts Medical Society, 2024).

Bedi, S. et al. A systematic review of testing and evaluation of healthcare applications of large language models (LLMs). medRxiv, 2024.2004. 2015.24305869 (2024).

Bedi, S. et al. Testing and evaluation of health care applications of large language models: a systematic review. JAMA 333, 319–328 (2025).

Good, B. M., Ainscough, B. J., McMichael, J. F., Su, A. I. & Griffith, O. L. Organizing knowledge to enable personalization of medicine in cancer. Genome Biol. 15, 1–9 (2014).

The Lancet Oncology Incorporating whole-genome sequencing into cancer care. Lancet Oncol. 25, 945 (2024).

Stahl, B. C. Embedding responsibility in intelligent systems: from AI ethics to responsible AI ecosystems. Sci. Rep 13, 7586 (2023).

Fleisher, L. A. & Economou-Zavlanos, N. J. in JAMA Health Forum. e241369-e241369 (American Medical Association).

Tobia, K., Nielsen, A. & Stremitzer, A. When does physician use of AI increase liability? J. Nucl. Med. 62, 17–21 (2021).

Carmona, J. et al. Cancer Core Europe: Leveraging institutional synergies to advance oncology research and care globally. Cancer Discov. 14, 1147–1153 (2024).

Moffett, P. & Moore, G. The standard of care: legal history and definitions: the bad and good news. West. J. Emerg. Med. 12, 109 (2011).

Meineke, F., Modersohn, L., Loeffler, M. & Boeker, M. in Caring is Sharing–Exploiting the Value in Data for Health and Innovation 835–836 (IOS Press, 2023).

Tayefi, M. et al. Challenges and opportunities beyond structured data in analysis of electronic health records. WIREs Comput. Stat. 13, e1549 (2021).

Martino, A., Iannelli, M. & Truong, C., In European Semantic Web Conference. 182–185 (Springer).

Balagurunathan, Y., Mitchell, R. & El Naqa, I. Requirements and reliability of AI in the medical context. Phys. Med. 83, 72–78 (2021).

Longhurst, C. A., Singh, K., Chopra, A., Atreja, A. & Brownstein, J. S. Vol. 1 AIp2400223 (Massachusetts Medical Society, 2024).

Department of Health and Human Services Office of the Secretary. HIPAA Privacy Rule to support reproductive health care privacy (Rule Document No. 2024-08503). Fed. Regist. 89, 32976–33066 (2024). accessed Nov 21, (2025).

European Parliament & Council of the European Union. Regulation (EU) 2017/745 on medical devices, amending Directive 2001/83/EC, Regulation (EC) No 178/2002 and Regulation (EC) No 1223/2009 and repealing Council Directives 90/385/EEC and 93/42/EEC. Official J Eur. Union, L 117, 1–175. (2017) accessed Nov 21, (2025).

European Parliament & Council of the European Union. Regulation (EU) 2024/1689 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 June 2024 laying down harmonised rules on artificial intelligence and amending Regulations (EC) No 300/2008, (EU) No 167/2013, (EU) No 168/2013, (EU) 2018/858, (EU) 2018/1139 and (EU) 2019/2144 and Directives 2014/90/EU, (EU) 2016/797 and (EU) 2020/1828 (Artificial Intelligence Act) https://data.europa.eu/eli/reg/2024/1689/oj. Official J Eur. Union, L 2024/1689 (2024).

Gottlieb, S. in JAMA Health Forum. e242691-e242691 (American Medical Association).

Busch, F. et al. Navigating the european union artificial intelligence act for healthcare. npj Digit. Med. 7, 210 (2024).

World Medical Association Declaration of Geneva. Afr Health Sci. 17, 1203, (2017).

ABIM, A.-A. & Charter, E. A. P. Project of the ABIM Foundation. ACP-ASIM Foundation, and European Federation of Internal Medicine: ABIM Foundation, ACP-ASIM Foundation, and European Federation of Internal Medicine (2002).

Pappworth, M. H. Modern Hippocratic Oath. Br. Med. J. 1, 668 (1971).

Beauchamp, T. & Childress, J. Vol. 19 9–12 (Taylor & Francis, (2019).

Beauchamp, T. L. & Childress, J. F. Principles of Biomedical Ethics. (Edicoes Loyola, 1994).

Wiesing, Urban. The Declaration of Helsinki—Its History and Its Future. World Medical Association, November 11. https://www.wma.net/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/Wiesing-DoH-Helsinki-20141111.pdf, (2014) accessed Nov 21, (2025).

Mittelstadt, B. Principles alone cannot guarantee ethical AI. Nat. Mach. Intell. 1, 501–507 (2019).

Jobin, A., Ienca, M. & Vayena, E. The global landscape of AI ethics guidelines. Nat. Mach. Intell. 1, 389–399 (2019).

Floridi, L. et al. AI4People—an ethical framework for a good AI society: opportunities, risks, principles, and recommendations. Minds Mach. 28, 689–707 (2018).

Rubeis, G. Ethics of medical AI. (Springer, 2024).

Buckley, R. P., Zetzsche, D. A., Arner, D. W. & Tang, B. W. Regulating artificial intelligence in finance: putting the human in the loop. Syd. Law Rev. 43, 43–81 (2021).

Peters, D., Vold, K., Robinson, D. & Calvo, R. A. Responsible AI—two frameworks for ethical design practice. IEEE Trans. Technol. Soc. 1, 34–47 (2020).

McLennan, S. et al. An embedded ethics approach for AI development. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2, 488–490 (2020).

Thirunavukarasu, A. J. et al. Large language models in medicine. Nat. Med. 29, 1930–1940 (2023).

Clusmann, J. et al. The future landscape of large language models in medicine. Commun. Med. 3, 141 (2023).

Uprety, D., Zhu, D. & West, H. ChatGPT—A promising generative AI tool and its implications for cancer care. Cancer 129, 2284–2289 (2023).

Chandak, P., Huang, K. & Zitnik, M. Building a knowledge graph to enable precision medicine. Sci. Data 10, 67 (2023).

From Einstein to AI: how 100 years have shaped science. Nature 624, 474, https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-023-04021-2 (2023).

European Parliament & Council of the European Union. Regulation (EU) 2016/679 on the protection of natural persons with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data, and repealing Directive 95/46/EC (General Data Protection Regulation). Official J Eur. Union, L 119, 1–88. (2016) accessed Nov 21, https://data.europa.eu/eli/reg/2016/679/oj (2025).

Yoshizawa, G. et al. Limiting open science? Three approaches to bottom-up governance of dual-use research of concern. Pathog. Glob. Health 118, 285–294 (2024).

Khanna, N. N. et al. Economics of artificial intelligence in healthcare: diagnosis vs. treatment. In Healthcare Vol. 10, 2493 (MDPI, 2022).

Mehta, M. C., Katz, I. T. & Jha, A. K. Transforming global health with AI. N. Engl. J. Med. 382, 791–793 (2020).

Moreau, L. & Missier, P. (eds) PROV-DM: The PROV Data Model (W3C Recommendation, 30 April 2013). World Wide Web Consortium (W3C). http://www.w3.org/TR/2013/REC-prov-dm-20130430/, (2013) accessed Nov 21, (2025).

Dwork, C., Hardt, M., Pitassi, T., Reingold, O. & Zemel, R. In Proceedings of the 3rd Innovations in Theoretical Computer Science Conference. 214-226.

Yang, Y., Zhang, H., Gichoya, J. W., Katabi, D. & Ghassemi, M. The limits of fair medical imaging AI in real-world generalization. Nat. Med. 30, 2838–2848 (2024).

Franklin, G. et al. The sociodemographic biases in machine learning algorithms: a biomedical informatics perspective. Life 14, 652 (2024).

Zafar, M. R. & Khan, N. M. DLIME: A deterministic local interpretable model-agnostic explanations approach for computer-aided diagnosis systems. arXiv preprint arXiv:1906.10263 (2019).

Nohara, Y., Matsumoto, K., Soejima, H. & Nakashima, N. Explanation of machine learning models using shapley additive explanation and application for real data in hospital. Comput. Methods Prog. Biomed. 214, 106584 (2022).

Kuenzi, B. M. et al. Predicting drug response and synergy using a deep learning model of human cancer cells. Cancer Cell 38, 672–684. e676 (2020).

Herm, L.-V., Heinrich, K., Wanner, J. & Janiesch, C. Stop ordering machine learning algorithms by their explainability! A user-centered investigation of performance and explainability. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 69, 102538 (2023).

Wiest, I. C. et al. Anonymizing medical documents with local, privacy preserving large language models: The LLM-Anonymizer. medRxiv, 2024.2006. 2011.24308355 (2024).

Ghassemi, M., Oakden-Rayner, L. & Beam, A. L. The false hope of current approaches to explainable artificial intelligence in health care. Lancet Digit. Health 3, e745–e750 (2021).

Brundage, M. et al. Toward trustworthy AI development: mechanisms for supporting verifiable claims. arXiv preprint arXiv:2004.07213 (2020).

Gostin, L. Health care information and the protection of personal privacy: ethical and legal considerations. Ann. Intern. Med. 127, 683–690 (1997).

Burgess, M. M. Beyond consent: ethical and social issues in genetic testing. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2, 147–151 (2001).

European, P. & Council. Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016 on the protection of natural persons with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data, and repealing Directive 95/46/EC (General Data Protection Regulation). 1-88 (2016).

Malin, B. & Sweeney, L. Re-identification of DNA through an automated linkage process. In Proc. of the AMIA Symposium 423 (2001).

El Emam, K. & Dankar, F. K. Protecting privacy using k-anonymity. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 15, 627–637 (2008).

Neubauer, T. & Heurix, J. A methodology for the pseudonymization of medical data. Int. J. Med. Inform. 80, 190–204 (2011).

Mehtälä, J. et al. Utilization of anonymization techniques to create an external control arm for clinical trial data. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 23, 258 (2023).

International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use. ICH harmonised guideline: Guideline for Good Clinical Practice E6(R3) (Final version, adopted 06 January 2025). https://database.ich.org/sites/default/files/ICH_E6%28R3%29_Step4_FinalGuideline_2025_0106.pdf, (2025) accessed Nov 21, (2025).

Lamprecht, A.-L. et al. Towards FAIR principles for research software. Data Sci. 3, 37–59 (2020).

Finlayson, S. G. et al. The clinician and dataset shift in artificial intelligence. N. Engl. J. Med. 385, 283–286 (2021).

van de Sande, D. et al. To warrant clinical adoption AI models require a multi-faceted implementation evaluation. NPJ Digit. Med. 7, 58 (2024).

Boos, L. & Wicki, A. The molecular tumor board—a key element of precision oncology. memo. -Mag. Eur. Med. Oncol. 17, 190–193 (2024).

Lammert, J. et al. Expert-guided large language models for clinical decision support in precision oncology. JCO Precis. Oncol. 8, e2400478 (2024).

Es, S., James, J., Anke, L. E. & Schockaert, S. in Proceedings of the 18th Conference of the European Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: System Demonstrations. 150–158.

Zhang, T., Kishore, V., Wu, F., Weinberger, K. Q. & Artzi, Y. Bertscore: Evaluating text generation with bert. arXiv Prepr. arXiv 1904, 09675 (2019).

Cohen, I. G. et al. How AI can learn from the law: putting humans in the loop only on appeal. npj Digit. Med. 6, 160 (2023).

Gilbert, S. The EU passes the AI Act and its implications for digital medicine are unclear. NPJ Digit. Med. 7, 135 (2024).

Li, H., Yu, L. & He, W. Vol. 22 1-6 (Taylor & Francis, (2019).

Computers make mistakes and AI will make things worse - the law must recognize that. Nature 625, 631, (2024).

Marshall, P. et al. Recommendations for the probity of computer evidence. Digit. Evid. Elec. Signat. L. Rev. 18, 18 (2021).

Rieke, D. T. et al. Feasibility and outcome of reproducible clinical interpretation of high-dimensional molecular data: a comparison of two molecular tumor boards. BMC Med. 20, 367 (2022).

Loh, E. Medicine and the rise of the robots: a qualitative review of recent advances of artificial intelligence in health. BMJ leader 2, 59–63 (2018).

Rajpurkar, P. & Lungren, M. P. The current and future state of AI interpretation of medical images. N. Engl. J. Med. 388, 1981–1990 (2023).

Scheetz, J. et al. A survey of clinicians on the use of artificial intelligence in ophthalmology, dermatology, radiology and radiation oncology. Sci. Rep. 11, 5193 (2021).

Messeri, L. & Crockett, M. Artificial intelligence and illusions of understanding in scientific research. Nature 627, 49–58 (2024).

Ouyang, L. et al. Training language models to follow instructions with human feedback. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 35, 27730–27744 (2022).

Shah, N. H., Entwistle, D. & Pfeffer, M. A. Creation and adoption of large language models in medicine. JAMA 330, 866–869 (2023).

Lewis, P. et al. Retrieval-augmented generation for knowledge-intensive NLP tasks. Adv. neural Inf. Process. Syst. 33, 9459–9474 (2020).

Brown, T. et al. Language models are few-shot learners. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 33, 1877–1901 (2020).

Toros, E., Asiksoy, G. & Sürücü, L. Refreshment students’ perceived usefulness and attitudes towards using technology: a moderated mediation model. Hum. Soc. Sci. Commun. 11, 1–10 (2024).

Mustafa, S., Zhang, W., Anwar, S., Jamil, K. & Rana, S. An integrated model of UTAUT2 to understand consumers’ 5G technology acceptance using SEM-ANN approach. Sci. Rep. 12, 20056 (2022).

Du Boulay, B. Artificial intelligence as an effective classroom assistant. IEEE Intell. Syst. 31, 76–81 (2016).

Schwill, S. et al. The WFME global standards for quality improvement of postgraduate medical education: Which standards are also applicable in Germany? Recommendations for physicians with a license for postgraduate training and training agents. GMS J. Med Educ. 39, Doc42 (2022).

Narayanan, S., Ramakrishnan, R., Durairaj, E. & Das, A. Artificial intelligence revolutionizing the field of medical education. Cureus 15 (2023).

Franco D’Souza, R., Mathew, M., Mishra, V. & Surapaneni, K. M. Twelve tips for addressing ethical concerns in the implementation of artificial intelligence in medical education. Med. Educ. Online 29, 2330250 (2024).

Gatta, G. et al. Rare cancers are not so rare: the rare cancer burden in Europe. Eur. J. Cancer 47, 2493–2511 (2011).

Lainé, A., Hanvic, B. & Ray-Coquard, I. Importance of guidelines and networking for the management of rare gynecological cancers. Curr. Opin. Oncol. 33, 442–446 (2021).

Bogani, G. et al. Endometrial carcinosarcoma. Int J. Gynecol. Cancer 33, 147–174 (2023).

National Cancer Institute. Uterine carcinosarcoma study (TCGA). National Cancer Institute Center for Cancer Genomics, https://www.cancer.gov/ccg/research/genome-sequencing/tcga/studied-cancers/uterine-carcinosarcoma-study accessed Sept 24, (2025).

Cherniack, A. D. et al. Integrated molecular characterization of uterine carcinosarcoma. Cancer Cell 31, 411–423 (2017).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Board of Directors of CCE for critically reading, revising, and approving this paper. This study received no funding.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.M. has made substantial contributions to the conception, drafting, writing, revising, and finalizing the manuscript and is the main author of this work. DF has made substantial contributions to drafting, writing the manuscript and has critically revised this work. TD has made substantial contributions to conceptualizing the manuscript and has substantially revised this work. K.B. has made substantial contributions to conceptualizing the manuscript and has substantially revised this work. L.M. has made substantial contributions to conceptualizing the manuscript and has substantially revised this work. T.W. has made substantial contributions to conceptualizing the manuscript and has substantially revised this work. R.D. has substantially revised this work. J.V. has substantially revised this work. S.K. has substantially revised this work. R.P.L. has made substantial contributions to designing this work and substantially revised the manuscript. AP has substantially revised this work. FS has substantially revised this work. R.D.B. has made substantial contributions to designing this work and substantially revised the manuscript. M.B. has made substantial contributions to conceptualizing the manuscript and has substantially revised this work. J.N.K. has made substantial contributions to conceptualizing the manuscript and has substantially revised this work. M.T. has contributed substantially to the conception and drafting of the manuscript and to the analysis of data and has critically revised this work. J.L. has made substantial contributions to the conception, drafting, writing, revising, and finalizing of the manuscript and has supervised this work. All authors have approved the final version of the manuscript. All authors agreed both to be personally accountable for the author's own contributions and to ensure that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work, even ones in which the author was not personally involved, are appropriately investigated, resolved, and the resolution documented in the literature.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

SM has received speaker honoraria and travel reimbursements from ALK-Abelló (Copenhagen, Denmark). DF has received an OpenAI research grant and holds shares and is an employee at Synagen GmbH, Germany. TD has no COI. KJB declares speaker honoraria from Accuray Inc. (Sunnyvale, California, United States), travel reimbursement from Zeiss group (Oberkochen, Baden-Württemberg, Germany), and consulting services for NEED Inc., Santa Monica, CA 90405, United States. LM has no COI. TW has no COI. FS has received speaker fees from Pfizer, Sweden, and speaker fees from Lunit, South Korea, and is a shareholder of ClearScanAI AB, Sweden; MB declares no COI. A.P. has a consulting/advisory role for BMS, AstraZeneca, Novartis, MSD, Lilly, Amgen, Pfizer, and Johnson & Johnson; travel, accommodations, or other expenses paid or reimbursed by Roche and Johnson & Johnson; and serves as the principal investigator for Spectrum Pharmaceuticals, BMS, Bayer, MSD, and Lilly outside the submitted work. RDB acknowledges support from Cancer Research UK, Cambridge Experimental Cancer Medicine Centre, and Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre (BRC-1215-20014). RDB declares: consulting services/honoraria (to institution) from AstraZeneca, Genentech/Roche, Molecular Partners, Novartis, Shionogi; and research grants from AstraZeneca, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Genentech/Roche. JNK declares consulting services for Bioptimus, France; Owkin, France; DoMore Diagnostics, Norway; Panakeia, UK; AstraZeneca, UK; Scailyte, Switzerland; Mindpeak, Germany; and MultiplexDx, Slovakia. Furthermore, he holds shares in StratifAI GmbH, Germany, Synagen GmbH, Germany, and has received a research grant from GSK, and has received honoraria from AstraZeneca, Bayer, Daiichi Sankyo, Eisai, Janssen, MSD, BMS, Roche, Pfizer, and Fresenius. MT has no COI. JL received speaker honoraria from the Forum for Continuing Medical Education (Germany), AstraZeneca (Germany), and Novartis (Germany).

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mathes, S., Ferber, D., Dreyer, T. et al. Collaborative framework on responsible AI in LLM-driven CDSS for precision oncology leveraging real-world patient data. npj Precis. Onc. 10, 15 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41698-025-01180-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41698-025-01180-5