Abstract

Leptomeningeal metastasis (LM) is a severe neurological complication in patients with lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD), typically indicating terminal stage and poor survival. Optimal treatments for patients with LM-LUAD rely on accurately predicting treatment efficacy and dynamically adjusting regimens. Here, we collected 301 cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) samples from 125 patients with LM-LUAD via the Ommaya reservoir at baseline and during the treatment course to systematically explore the clinical significance of CSF circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA). At baseline, the positive detection rate of CSF ctDNA (99.2%) was significantly higher than that of plasma ctDNA (57.6%). By evaluating the association between varying magnitudes of ctDNA dynamic changes and clinical responses at each time interval during the treatment, we discovered that when the change in ctDNA reached 20%, the consistency with clinical assessment could exceed 90%. Moreover, we further analyzed the significance of different values of CSF ctDNA mutation frequencies at baseline and various time points, as well as the trends of ctDNA changes relative to the baseline levels, in predicting patient prognosis. Accordingly, we constructed a CSF ctDNA-based prognostic map and developed a multi-feature model that exhibited outstanding performance in predicting and assessing the clinical responses of patients. To the best of our knowledge, this work represents the most systematic large-scale study on CSF ctDNA-based dynamic monitoring of patients with LM-LUAD, which is of great significance for guiding clinical treatments to extend patient lives.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Leptomeningeal metastasis (LM) represents a formidable neurological complications for patients with lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD), usually indicating terminal stage of tumor progression and extremely short survival1,2,3. The incidence rate of brain metastases and median survival in patients with LUAD is approximately 20–65% and 4.8–19.2 months, respectively2,4,5. The most effective treatment options for patients with LM-LUAD rely heavily on the accurate prediction of clinical efficacy and dynamic adjustment of treatment regimens based on response status. Since LM may be different from the primary lung tumors, investigating the molecular characteristics of LM may assist in guiding the diagnosis and treatment6,7,8,9. However, in clinical practice, obtaining LM samples from patients is almost impossible. In addition, due to blood–brain barrier blockage, the penetration of circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) released by LM into the blood circulation is limited10,11,12. The ctDNA detected in peripheral blood may be mainly derived from primary lung tumors or other extracranial metastases, which enhances noise and reduces the signal capture efficiency of LM. Alternatively, detecting ctDNA in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) that is in close contact with LM is proposed to overcome these limitations, clearly representing the molecular landscape and heterogeneity of LM.

The significance of CSF ctDNA in representing the genomic atlas of LM has been widely verified13,14. Meanwhile, the quantification and dynamic analysis of genetic profiles of CSF ctDNA can assist the evaluation of treatment efficacy, response monitoring, and prognosis prediction15. However, most studies have been limited by small cohorts, lack of sufficient samples at different time-points during treatment, and variable ctDNA detection methods. Furthermore, in terms of drug administration and CSF acquisition, implementing intrathecal chemotherapy and obtaining CSF based on Ommaya reservoir is more convenient and safe than based on of repeated lumbar puncture16,17.

Here, we obtained 301 CSF samples via the Ommaya reservoir and corresponding blood samples from 125 patients, focusing on the systematic analysis of the potential value of CSF ctDNA in clinical applications. We hypothesized that the CSF ctDNA level at baseline and different time points during treatment as well as the ctDNA changes in different time intervals may reflect treatment efficacy and patient prognosis. Our findings could help optimize the dynamic treatment strategies of CSF ctDNA-based testing in patients with LM-LUAD.

Results

Patient and sample characteristics

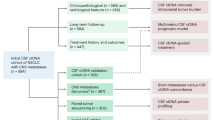

In total, 125 patients with LM-LUAD registered at Nanjing Chest Hospital between September 23, 2022, and June 1, 2024, were enrolled (Supplementary Table S1). All patients were fitted with the Ommaya reservoir for intracranial drug administration and CSF extraction. All patients received at least one cycle of treatment. By the time of manuscript submission, the duration of treatment and CSF ctDNA monitoring had lasted for maximum five times (Fig. 1a). For each ctDNA monitoring time point, the overall clinical response was evaluated according to the response assessment in neuro-oncology (RANO) working group on LM criteria18,19. A total of 125 CSF and blood samples were obtained at baseline, and 176 CSF samples were collected during treatment. All samples were processed for targeted next-generation sequencing. The carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) levels in CSF and blood samples from baseline and at different time points were also measured.

a Research flowchart. b The somatic mutations detected in paired baseline CSF (left) and plasma (right) samples are illustrated by OncoPrint plots. The top 10 most frequent mutations are shown. c The positive detection rates of somatic mutations in CSF and plasma samples at baseline (left), along with the distribution of the maxVAF (right). P-values were calculated using the t-test. ****p < 0.0001. d The distribution of maxVAF for EGFR (left) and TP53 (right) mutations across CSF and plasma samples. e The proportional distribution of different categories of somatic mutations detected in CSF and plasma samples. f The bar chart displays the number of patients (bottom) and positive detection rates (top) for different categories of somatic mutations at baseline. g The bar chart shows the number of patients in whom the most frequently detected somatic mutations were identified in CSF and plasma samples at baseline. h The distribution of maxVAF for mutations at different categories in both CSF (left) and plasma (right) samples. Abbreviation: CSF cerebrospinal fluid, maxVAF max variant allele frequency.

CSF ctDNA showed a higher detection rate and mutation frequency than plasma ctDNA

By comparing the mutational profiles of the matched white blood cells for each patient, we first constructed the genetic landscape of CSF and plasma at baseline, which contained 662 and 155 mutational types, respectively (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Data S1). We detected at least one somatic mutation in 99.2% CSF samples and 57.6% plasma samples (Fig. 1c). Moreover, the max variant allele frequency (maxVAF) of detectable mutations at baseline in CSF (mean: 40.93%) was significantly higher than that in plasma samples (mean: 2.12%), demonstrating greater sensitivity of CSF in somatic mutation detection (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Table S2). Consistent with the results of previous studies and the TCGA cohort, the most frequent mutations detected in CSF and plasma ctDNA at baseline occurred on EGFR and TP53. The detection rate of these two genes in CSF samples (78% and 64% for EGFR and TP53, respectively) was twice that in plasma samples (29% and 30%, respectively) (Fig. 1b). Meanwhile, the maxVAF of the two genes detected in CSF samples was also significantly higher than that in blood samples (Fig. 1d).

We further classified all mutation variants into three categories according to their clinical relevance: Tier 1 (variants with known clinical significance), Tier 2 (variants with potential clinical significance), and Tier 3 (variants with unknown clinical significance) (Fig. 1e). We found that 86.4% (108), 36.8% (46), and 91.2% (114) baseline CSF samples carried Tier 1, Tier 2, and Tier 3 mutations, respectively. Comparatively, only 39.2% (49), 20.8% (26), and 24% (30) of the corresponding genomic alterations were detected in plasma (Fig. 1f). We then examined the detection rates of frequent mutation sites across different Tiers and found that L858, A750del, and T790M mutations of EGFR had the highest mutational frequency in CSF and the first two mutations also had the highest detection rates in plasma (Fig. 1g). The maxVAF of Tier 1 and Tier 3 variants was the highest in the CSF and plasma samples, respectively (Fig. 1h). These results indicated that CSF exhibits superior performance to plasma in terms of ctDNA detection capability.

Next, we evaluated the concordance of mutation detection in CSF and plasma samples at baseline. Shared somatic mutations represented 12.24% (81/662) and 52.26% (81/155) variants detected in CSF and plasma samples, respectively (Supplementary Fig. S1a). Further comparisons were performed in a subgroup of patients with paired primary tumor tissue/pleural effusion (T/P) as well as CSF and plasma samples. The results showed that 61.6% and 60.1% mutation variants from T/P were detected in paired CSF samples and paired plasma samples, respectively (Supplementary Fig. S1b). Representative cases showed mutations shared among different tissues at baseline and mutations unique to CSF ctDNA (Supplementary Fig. S1c). Multiple mutations unique to CSF ctDNA were continuously detected during subsequent treatment. For shared mutations, we assessed the correlation of maxVAF detected by different tissue types and found that CSF had a higher correlation (r = 0.74) with T/P than plasma (r = 0.55) (Supplementary Fig. S1d).

The dynamic changes in CSF ctDNA exhibited higher clinical response predictive ability

We next evaluated whether the dynamic changes in maxVAF of CSF ctDNA were predictive of clinical responses. We analyzed the CSF ctDNA levels at each time interval from baseline to the last detection time point for each patient (Fig. 2). A total of 39 patients were excluded from the subsequent study due to lack of ctDNA detection data after baseline. We analyzed the concordance between the relative changes in CSF ctDNA maxVAF (∆CSF-ctDNA-maxVAF) and clinical response, and simultaneously analyzed CEA changes in CSF (∆CSF-CEA) and plasma (∆Plasma-CEA) as a comparison for the remaining 86 patients (Fig. 3a, b, Supplementary Fig. S2a, b and Supplementary Data S2–S3). We defined the concordance rates as the proportion of patients whose ctDNA dynamic trends were consistent with their clinical response, that is, the proportion of patients with decreased ctDNA maxVAF that respond to clinical treatment or the proportion of patients with elevated ctDNA maxVAF that do not respond to clinical treatment. Meanwhile, we examined the concordance rates corresponding to 0–30% ∆CSF-ctDNA-maxVAF for each time interval (Fig. 3c and Supplementary Fig. S2c). We found that in the first time interval (T0–T1), the concordance rate was more than 90% when the change amplitude of CSF ctDNA maxVAF was 20% or more (∆CSF-ctDNA-maxVAF > 20%) (Fig. 3c). Focusing on mutations in TP53 and EGFR, as well as EGFR L858R variant, comparable concordance rates were observed. Similar results were also obtained for T1–T2 and T2–T3 intervals (Fig. 3c and Supplementary Fig. S2c). Accordingly, we defined a “ctDNA response” as the negative ∆CSF-ctDNA-maxVAF achieved 20% (20% decrease in ctDNA maxVAF) and a “ctDNA progression” as the positive ∆CSF-ctDNA-maxVAF achieved 20% (20% increase in ctDNA maxVAF). Among the 20 patients with CSF ctDNA response and 15 with ctDNA progression in the first time interval, 90% (18) were clinically responsive (PR) and 93.33% (14) were unresponsive [progressive disease (PD) and stable disease (SD)], respectively (Fig. 3d). Further assessments of response and progression based on ∆CSF-ctDNA-EGFR demonstrated higher clinical consistency. (90–100%) (Fig. 3e). However, when we defined CEA response or progression as a 20% decrease or increase in plasma or CSF CEA levels, we observed relatively low concordance rates (Fig. 3f), indicating that CSF ctDNA has a higher predictive ability of clinical response than CEA.

The swimmer plot displays the changes in CSF ctDNA maxVAF from baseline to the last detection time point, as well as the corresponding treatment status (RE/Non-RE) of patients who received at least one treatment (n = 86), during the intervals. Each bar length represents the duration from baseline to the last follow-up. The line segments are color-coded according to the results of the RANO assessment, up to the study endpoint. The triangles in the plot indicate whether CSF ctDNA was increased or decreased compared to baseline. Abbreviation: CSF cerebrospinal fluid, ctDNA circulating tumor DNA, maxVAF max variant allele frequency, RANO response assessment in neuro-oncology.

Line plots showing the changes in CSF ctDNA maxVAF (a) and CSF CEA (b) in patients (n = 86) who received at least one treatment. c Heatmap showing the concordance rates of ctDNA and CEA between two time intervals (T0–T1 and T1–T2) at different thresholds (0–30%). The upward and downward arrows indicate an increase and decrease in the maxVAF/VAF of ctDNA or the value of CEA, respectively. The boxed values highlight the concordance rates when the magnitude of CSF ctDNA changes (across all mutations) reached 20%. d The line graph (left) illustrates changes in the maxVAF of all mutations in CSF ctDNA from baseline (T0) to time point T1. Each line corresponds to an individual patient, with line color indicating treatment response: green for RE, red for NRE(PD), and blue for NRE(SD). The bar chart (right) shows the proportional distribution of different clinical responses between two groups: ctDNA response and ctDNA progression, as identified based on all mutations in CSF ctDNA. Bar color corresponds to treatment response: green for RE, red for NRE (SD), and yellow for NRE (PD). As observed, RE patients accounted for 90% in the ctDNA response group, indicating a concordance rate of 90%; similarly, NRE patients accounted for 93.3% in the ctDNA progression group, corresponding to a concordance rate of 93.3%. e The figure presents results corresponding to those in d, derived from EGFR mutations in CSF ctDNA. f The figure displays results corresponding to those in d, obtained from changes in CEA levels in plasma and CSF. Specifically, CEA response or progression was defined as a 20% decrease or increase in plasma or CSF CEA levels, respectively. Abbreviation: CEA carcinoembryonic antigen, CSF cerebrospinal fluid, ctDNA circulating tumor DNA, maxVAF max variant allele frequency, PD progressive disease, NRE non-responses, RE responses, SD stable disease.

Two representative cases are shown in Fig. 4. Patient P9 (Fig. 4a) and patient P77 (Fig. 4b) received 2 and 3 cycles of paclitaxel combined with cisplatin Vumetimab. Evaluations based on contrast-enhanced brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and CSF cytology revealed different clinical treatment responses for the two patients. We observed that patient P9, with continuous negative ∆CSF-ctDNA-maxVAF compared to baseline, showed sustained clinical benefit, while patient P77 with continuous positive ∆CSF-ctDNA-maxVAF did not derive clinical benefit. Furthermore, changes in the mutation sites of TP53, EGFR, and L858R, as well as changes in CEA, were also consistent with the clinical response.

At baseline, both MRI assessment and cytopathological observation indicated intracranial metastasis in patients P9 (a) and P77 (b). After 2–3 cycles of treatment, MRI assessment and cytopathological observation showed partial response in the lesion of patient P9, and correspondingly, the CSF ctDNA and CEA values gradually decreased compared to the baseline values. In contrast, MRI assessment and cytopathological observation in patient P77 revealed intracranial lesion progression and the corresponding CSF ctDNA and CEA values increased gradually. Abbreviation: CEA carcinoembryonic antigen, CSF cerebrospinal fluid, ctDNA circulating tumor DNA, maxVAF max variant allele frequency, MRI magnetic resonance imaging.

Analysis of associations between CSF ctDNA and clinical outcomes by establishing CSF ctDNA-based clinical prognostic maps

After establishing the concordance between ∆CSF-ctDNA and clinical responses, we investigated whether CSF ctDNA levels at specific time points or their dynamic changes during the treatment could predict clinical outcomes. First, for each time point, we classified patients based on the CSF ctDNA maxVAF levels at different values and assessed the ability to discriminate clinical outcomes (Fig. 5a, b and Supplementary Data S4). We found that patients with baseline CSF ctDNA maxVAF above 0.5 were associated with poor survival (Fig. 5b). At T2 and T3 time points, a lower CSF ctDNA maxVAF (0.4) can significantly distinguish the patients with different survival periods (Fig. 5b). Positive results were also obtained by focusing on mutations in the EGFR and TP53 genes as well as the L858R mutation site, while these were not observed in blood-based ctDNA tests (Fig. 5a). Based on the values of CSF ctDNA maxVAF detected at specific time points, we also distinguished patients with different intracranial progression-free survival (iPFS). For example, patients with CSF ctDNA maxVAF exceeding 0.4 at T1 or greater than 0 at T2 had a significantly shorter iPFS (Fig. 5a, b).

a Bubble plot represents the degree of correlation between different values of the maxVAF of ctDNA detected at various time points and clinical prognosis. The bubble size and color represent the magnitude of the p-values. Bubbles with p-values ≤ 0.05 are marked with a red star. P-values were calculated using the log-rank test. The connected circles on the left represent the time points at which CSF ctDNA maxVAF was measured, with solid black circles indicating that maxVAF values were detected at the corresponding time points. All plasma ctDNA maxVAF values were derived from measurements at the baseline time point. The bubbles enclosed by colored dashed boxes correspond to the Kaplan-Meier (KM) curves presented in (b). b Kaplan–Meier curves of OS or iPFS corresponding to the representative points in (a). c Bubble plot represents the degree of correlation between the different change magnitudes of CSF ctDNA maxVAF at various time intervals and clinical prognosis. d Kaplan–Meier curves of OS or iPFS corresponding to the representative points in (c). Abbreviation: CSF cerebrospinal fluid, ctDNA circulating tumor DNA, iPFS intracranial progression-free survival, maxVAF max variant allele frequency, OS overall survival.

By further analyzing the dynamic changes of ctDNA in CSF, we found that the patients whose ctDNA maxVAF detected at each time point during the treatment were 10% lower than the baseline levels had a long iPFS (Fig. 5c, d). In contrast, patients with an upward trend compared to the baseline had a short iPFS. Similarly, significant results under different thresholds could be obtained based on the mutation sites located on the TP53 and EGFR genes, as well as the L858R site. However, although the dynamic changes of CSF ctDNA were associated with patient survival, such as patients with ctDNA levels all increased compared to the baseline, having a shorter OS, no statistically significant differences were observed (Fig. 5c).

Assessment of patient clinical responses based on a multi-feature model

Owing to the associations between changes in CSF ctDNA and CSF/plasma CEA with clinical responses, we aimed to construct a multi-feature model and evaluate its potential for clinical application. Based on the changes in above indicators (∆CSF-ctDNA, ∆CSF-CEA, and ∆plasma-CEA) at different treatment time points compared to the baseline for each patient and the corresponding clinical treatment responses (Fig. 6a), we first employed the Random Forest (RF) method to build the model. During this process, we trained candidate models using the independent assessment results of different indicators as well as the evaluation results of various indicator combinations. To optimize model parameters and prevent overfitting, we utilized 5-fold cross-validation, repeating it five times. We found that the accuracy of all combinations exceeded 0.6 (Fig. 6b). Notably, the ∆CSF-ctDNA + ∆plasma-CEA and ∆CSF-ctDNA + ∆CSF-CEA + ∆plasma-CEA combinations demonstrated significantly higher area under the curve (AUC) values in predicting patient clinical responses (Fig. 6c). Moreover, the ∆CSF-ctDNA + ∆plasma-CEA model exhibited the most stable performance in the confusion matrix, making it the preferred choice for the multi-feature model (Fig. 6d). Subsequently, we further validated the evaluation performance of this combination using a Feed-Forward Neural Network (FNN) model. Analyses of relevant metrics, including the F1 score, accuracy, AUC, and precision–recall curve (PR curve), consistently indicated the accuracy of the model with this combination in predicting patient clinical responses (Fig. 6e–h). In conclusion, the multi-feature model constructed based on the ∆CSF-ctDNA and Δplasma-CEA successfully predicted patient clinical response, highlighting its potential for clinical guidance.

a Workflow of constructing the multi-feature model. b Comparative analysis of model accuracy using different feature combinations trained with the RF algorithm. c ROC curve of the RF model trained with all feature combinations in the validation cohort. d Confusion matrix of the RF model trained with the optimal feature combination in the validation cohort. Performance comparison of the optimal feature combination using the FNN algorithm: accuracy and F1 score (e), ROC curve (f), confusion matrix (g), and PR curve (h) for the feature combinations model in the validation cohort. Abbreviations: DFCs different feature combinations, FNN feed-forward Neural Network, NRE non-responses (SD/PD), PR curve, precision–recall curve, RE responses, RF random forest.

Discussion

In this study, we used many CSF samples from patients with LM-LUAD to systematically investigate the significance of CSF ctDNA in clinical applications. We compared the concordance of mutation detection in baseline CSF and plasma samples as well as matched tissue specimens, and evaluated the performance of CSF ctDNA for response monitoring and prognosis assessment. To the best of our knowledge, this is the largest and the most systematic work exploring the clinical association of CSF ctDNA for patients with LM-LUAD. This is also the first study to suggest the best reference thresholds for clinical guidance in terms of the frequency of CSF ctDNA mutations and the magnitude of their dynamic changes, both at baseline and during treatment.

In comparison of CSF- and plasma-derived ctDNA mutation profiles, we found that almost all patients (99.2%) had detectable somatic mutations in CSF, while ctDNA was detected in 57.6% plasma samples. The mutation detection rate in the CSF was four times higher than in the plasma. Meanwhile, the frequency of ctDNA mutations in CSF was significantly higher than that in plasma. We initially suspected that this discrepancy was due to the differences in sequencing depth between the CSF and plasma; a careful review of the sequencing data dismissed this possibility. We believe that the signal of LM mutations detected in the blood was limited by the blood–brain barrier, which could be effectively captured by CSF ctDNA detection.

Wu et al.20 have demonstrated that the mutation frequency of CSF ctDNA was higher than that of plasma ctDNA, which is consistent with our result. Meanwhile, most previous studies employed lumbar puncture for sampling16,21, which is not ideal for repeated sampling. In comparison, we utilized the Ommaya reservoir for sampling, allowing for direct access to the CSF within the ventricles and providing a targeted, controlled, and repeated process to collect CSF samples. At present, the Ommaya reservoir is indicated for all LM-LUAD patients in need of intrathecal chemotherapy. In our cohort, 42.4% patients provided three or more CSF samples, which facilitated an accurate analysis of ctDNA-based monitoring.

This study investigated the importance of ctDNA mutation frequency and its dynamic changes in evaluating response and prognosis on a large scale. Although previous studies have demonstrated the validity and accuracy of CSF ctDNA in evaluating clinical efficacy, they were based on limited sample sizes and retrospective analyses22,23. Based on the longitudinal sampling of patients during intracranial treatment, we analyzed the efficacy of different ctDNA thresholds in assessing therapeutic efficacy and predicting prognosis. We found that >20% ctDNA mutation frequency has a high consistency with the clinical evaluation results. Therefore, this threshold was defined as the ctDNA response or progression threshold. We further constructed prognostic maps obtained from different ctDNA maxVAF values, which were of great significance for evaluating the survival and disease progression of patients at different time points. It is worth mentioning that this study used a mature commercial product to adopt a unified experimental and analytical approach for all the CSF samples, avoiding the deviations caused by technical differences and facilitating the clinical translation of the research.

Our study also had some limitations. First, due to the clinical infeasibility of obtaining LM from patients, we could not conduct a comparative analysis of the mutational profiles of CSF and LM tissues. Although several mutations in the CSF were not detectable in the plasma, we could not confirm whether these mutations were LM-specific. However, recurrent mutations in a single patient at different time points infer their presence in LM. In addition, owing to the diverse disease conditions among patients, the clinical treatment strategies and dosages differed. These factors might have introduced biases in the evaluation of treatment response and prognosis.

In summary, the results of this large-scale study suggest that CSF ctDNA-based monitoring has a wide range of clinical applications in the treatment of patients with LM-LUAD. This is an effective strategy for predicting clinical therapeutic efficacy and patient survival, and disease progression. To further validate the clinical utility of our findings, we further aim to apply them in larger cohorts and persistently optimize the CSF ctDNA-centered clinical guidance strategy.

Methods

Study design and sample collection

The study was conducted on patients with LM-LUAD who were registered at Nanjing Chest Hospital between September 23, 2022, and June 1, 2024. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) newly diagnosed non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) confirmed by histopathological examination, with patients aged between 18 and 80 years; (2) LM was diagnosed based on the EANO-ESMO criteria through CSF cytology and/or enhanced brain MRI; (3) patients who had undergone subcutaneous implantation of an Ommaya device and received at least one dose of the drug (pemetrexed); and (4) normal liver, kidney, and blood function indicators. The exclusion criteria were: (1) patients who did not undergo corresponding clinical tests after drug treatment; (2) patients with incomplete or lost follow-up information; (3) patients who died unexpectedly due to SARS-CoV-2; and (4) patients who developed severe complications during treatment (including severe infections, allergies, heart failure, and severe liver or kidney dysfunction). A total of 125 patients with LM were included in the study. Paired CSF and blood samples were collected from each patient within one week prior to the administration of the drug (baseline) and one week prior to each subsequent drug treatment (administered via the Ommaya device to the brain) and imaging evaluation (enhanced CT scan for extracephalic lesions and enhanced MRI for intracranial lesions). Imaging assessments were conducted approximately every 12 weeks until the end of the study. We collected CSF samples from patients at different time points during their treatment cycles. For all patients, the baseline (T0) uniformly refers to the timepoint when patients had been fitted with the Ommaya reservoir but had not yet received intracranial drug administration. T1 denotes the timepoint after patients completed one cycle of treatment, while T2-T4 correspond to the timepoints after patients finished 2-4 cycles of treatment, respectively. CEA levels in the blood and CSF of each patient were measured using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). The study was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of Nanjing Chest Hospital (Approval No: 2023-KL011-02), and all patients provided written informed consent prior to participation. The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Clinical endpoints

OS was defined as the time from hospital admission to patient death or the last follow-up. iPFS was defined as the time from hospital admission to the occurrence of disease progression in the brain or the last follow-up, with the earliest event considered as the reference. The clinical response was assessed through neurological symptom improvement, CSF analysis, radiographic assessment, and clinical symptom evaluation, according to the RANO Working Group on LM criteria. Treatment responses were classified as LM response, SD, or PD. The LM overall response rate was defined as the proportion of patients who achieved an LM response. The LM disease control rate was defined as the proportion of patients who achieved LM response or SD as the best response.

Plasma collection, cell-free DNA extraction, and sequencing

All CSF and whole blood samples were collected into Cell-Free DNA Collection Tubes (Roche) and processed within 24 h using a standard two-step centrifugation method to remove cellular components from the fluid. The extracted CSF, plasma, and paired white blood cells (WBC) were subsequently stored at −80 °C. Cell-free DNA (cfDNA) was extracted from the CSF, plasma, and WBC using the QIAamp Circulating Nucleic Acid Kit (QIAGEN) and the Mag-Bind® Blood & Tissue DNA HDQ 96 Kit (Omega). The cfDNA libraries were prepared using the NadPrep cfDNA Library Preparation Kit (Nanodigmbio). Hybridization enrichment was performed using targeted probes covering 1012 genes, YuceOne Plus (ctDNA), synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT). The enriched DNA fragments were then sequenced on the MGISEQ platform. The DNA input amount is in the range of 20–50 ng.

CtDNA analysis

Data analysis was performed as previously described24. Briefly, the sequencing data were processed using SOAPnuke 19 for adapter trimming and removal of low-quality reads. GeneCore 20 was utilized for data normalization based on unique molecule index. After removing PCR duplicates, the median coverage depth was >1507× for CSF samples and > 4644× for plasma samples. Reads were aligned to the human reference genome (hg19) using BWA, and duplicate reads were subsequently removed using Samtools. The resulting BAM files were then used for downstream analysis. Somatic mutations, including single nucleotide variants and small insertions/deletions (Indels), were identified using the mutation caller Vardict with default parameters. The caller was also run against dbSNP (version 147), the 1000 G (Phase3 v5 reference), CLINVAR (version 151 ClinVar (nih.gov)), and COSMIC (version 81) databases to filter known polymorphic sites. Mutations were filtered based on the following criteria: (1) low variant allele frequency (VAF < 0.0005); (2) variants supported by multiple reads in paired germline samples; and (3) mutations present in the genomic databases. The final filtered mutations were annotated based on snpEff (version 4.3) and NCBI RefSeq data (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/refseq/). The ctDNA level was calculated as previously described, where maxVAF represents the maximum variant allele frequency.

False positive mutations and clonal hematopoiesis (CHIP) filtering

To account for artifacts in variants caused by different specimen types, we used each patient’s white blood cells (WBC) as a control (the range of the coverage depth is 500–1000×) to filter out technical artifacts and germline variants, ensuring that only somatic mutations were retained for subsequent analyses. Further filtering was applied using an in-house database of CSF ctDNA background noise, and the use of Unique Molecular Identifier (UMI) sequencing also helped eliminate artifacts. Regarding clonal hematopoiesis (CHIP) in plasma, two filtering methods were adopted: (1) Filtering using a CHIP variant database, which included both the external public database Intogen and an internal retrospective historical database containing CHIP variants from WBC controls and ctDNA datasets; (2) Manual review of low-abundance mutations, where variants with fewer than 10 supporting reads in ctDNA were reviewed, and those with at least three supporting reads in WBC controls were identified as CHIP mutations and excluded from further analysis.

Concordance rates

We defined the concordance rates as the proportion of patients whose ctDNA or CEA dynamic trends were consistent with their clinical response. The specific calculation formula is as follows:

Construction of multi-feature predictive models for clinical response

Data were filtered using predefined thresholds: |∆CSF-ctDNA| ≤ 100%, |∆CSF-CEA| ≤ 200%, and |∆plasma-CEA| ≤ 200%. The final dataset, which included three key biomarkers across 97 time points, was used for model development. The input features for the RF model included seven feature combinations, namely the relative change in cerebrospinal fluid circulating tumor DNA (∆CSF-ctDNA), the relative change in cerebrospinal fluid carcinoembryonic antigen (∆CSF-CEA), the relative change in plasma carcinoembryonic antigen (∆plasma-CEA), the combination of ∆CSF-ctDNA and ∆CSF-CEA, the combination of ∆CSF-ctDNA and ∆plasma-CEA, the combination of ∆CSF-CEA and ∆plasma-CEA, and the combination of ∆CSF-ctDNA, ∆CSF-CEA, and ∆plasma-CEA. Then the feature selection was performed using the RF algorithm, implemented in the caret package (version 6.0.94). The dataset was divided into training (n = 49) and validation (n = 48) sets via 5-fold cross-validation, with standardization using the scale function. The RF models were trained with repeated 5-fold cross-validation, and the optimal feature set was selected based on accuracy, ROC curves, and confusion matrix analysis. A Multi-layer Perceptron model was constructed using the torch package (version 2.6.0+cpu). The dataset was standardized using the sklearn package (version 1.6.1), and training was performed using repeated 5-fold cross-validation (n = 49 for training, n = 48 for validation). Model training was repeated 50 times to optimize parameters. For the FNN model, we used the optimal feature combination screened by the RF model—i.e., the combination of ∆CSF-ctDNA and ∆plasma-CEA—as its input feature, which was validated to have the most stable and accurate predictive performance for patient clinical responses.

Statistical analysis

No statistical methods were employed to pre-determine the sample size, and randomization was not applied in the study design. No data were excluded during the analysis. The somatic mutations identified were classified into three tiers based on the joint guidelines published by ASCO, AMP, and CAP in the “Cancer Variant Interpretation and Reporting” (2017 edition): Tier 1 (mutations with clear clinical significance), Tier 2 (mutations with potential clinical significance), and Tier 3 (mutations with uncertain clinical significance). The effectiveness of drug treatment and changes in ∆ctDNA for each patient were visualized using swimmer plots. Survival analysis was conducted using the Kaplan–Meier method, and P-values along with their corresponding 95% confidence intervals were calculated. All p-values were two-sided, with P < 0.05 considered statistically significant. The relationships between variables were analyzed using the t-test, with P ≤ 0.05 considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses and graph generation were performed using GraphPad Prism (version 9.0) and R (version 4.4.2).

Data availability

Sequencing data in this study have been deposited at National Genomics Data Center (NGDC) with the accession number PRJCA034895 and are publicly available as of the date of publication.

Code availability

This study did not develop new algorithms or programming; all analysis code was sourced from published research or public databases. The code used in this study is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Chen, M. et al. Identification of RAC1 in promoting brain metastasis of lung adenocarcinoma using single-cell transcriptome sequencing. Cell Death Dis. 14, 330 (2023).

Wang, F. et al. The Chinese Society of Clinical Oncology (CSCO): clinical guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of gastric cancer, 2021. Cancer Commun. 41, 747–795 (2021).

Hendriks, L. E. L. et al. Survival of patients with non-small cell lung cancer having leptomeningeal metastases treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. Eur. J. Cancer 116, 182–189 (2019).

Hubbs, J. L. et al. Factors associated with the development of brain metastases: analysis of 975 patients with early stage nonsmall cell lung cancer. Cancer 116, 5038–5046 (2010).

Zuccato, J. A. et al. Prediction of brain metastasis development with DNA methylation signatures. Nat. Med. 31, 116–125 (2025).

Preusser, M. et al. Brain metastases: pathobiology and emerging targeted therapies. Acta Neuropathol. 123, 205–222 (2012).

Riihimäki, M. et al. Metastatic sites and survival in lung cancer. Lung Cancer 86, 78–84 (2014).

Ozcan, G., Singh, M. & Vredenburgh, J. J. Leptomeningeal metastasis from non–small cell lung cancer and current landscape of treatments. Clin. Cancer Res. 29, 11–29 (2023).

Wang, Y., Yang, X., Li, N.-J. & Xue, J.-X. Leptomeningeal metastases in non-small cell lung cancer: diagnosis and treatment. Lung Cancer 174, 1–13 (2022).

Li, Y. S. et al. Unique genetic profiles from cerebrospinal fluid cell-free DNA in leptomeningeal metastases of EGFR-mutant non-small-cell lung cancer: a new medium of liquid biopsy. Ann. Oncol. 29, 945–952 (2018).

Sindeeva, O. A. et al. New frontiers in diagnosis and therapy of circulating tumor markers in cerebrospinal fluid in vitro and in vivo. Cells 8, 1195 (2019).

Zhao, J. et al. EGFR mutation status of paired cerebrospinal fluid and plasma samples in EGFR mutant non-small cell lung cancer with leptomeningeal metastases. Cancer Chemother. Pharm. 78, 1305–1310 (2016).

Bai, K. et al. Cerebrospinal fluid circulating tumour DNA genotyping and survival analysis in lung adenocarcinoma with leptomeningeal metastases. J. Neurooncol. 165, 149–160 (2023).

LI, Y. & LI, X. Advances in clinical application of cerebrospinal fluid circulating tumor DNA in leptomeningeal metastasis of non-small cell lung cancer. Zhongguo Fei Ai Za Zhi = Chin. J. Lung Cancer 27, 376–382 (2024).

Wang, Y. et al. Unique genomic alterations of cerebrospinal fluid cell-free DNA are critical for targeted therapy of non-small cell lung cancer with leptomeningeal metastasis. Front Oncol. 11, 701171 (2021).

Li, M. et al. Dynamic monitoring of cerebrospinal fluid circulating tumor DNA to identify unique genetic profiles of brain metastatic tumors and better predict intracranial tumor responses in non-small cell lung cancer patients with brain metastases: a prospective cohort study (GASTO 1028). BMC Med. 20, 398 (2022).

Montes De Oca Delgado, M. et al. The comparative treatment of intraventricular chemotherapy by Ommaya reservoir vs. lumbar puncture in patients with leptomeningeal carcinomatosis. Front. Oncol. 8, 509 (2018).

Le Rhun, E. et al. Leptomeningeal metastasis from solid tumours: EANO–ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. ESMO Open 8, 101624 (2023).

Chamberlain, M. et al. Leptomeningeal metastases: a RANO proposal for response criteria. Neuro Oncol. 14, 484–492 (2016).

Wu, J. et al. Cerebrospinal fluid circulating tumor DNA depicts profiling of brain metastasis in NSCLC. Mol. Oncol. 17, 810–824 (2022).

Liang, J. et al. Clinical implications of CSF-Ctdna positivity in newly diagnosed diffuse large B cell lymphoma in a large cohort. Blood 144, 576 (2024).

Chai, R. et al. Sequencing of cerebrospinal fluid cell-free DNA facilitated early differential diagnosis of intramedullary spinal cord tumors. npj Precis. Oncol. 8, 1–9 (2024).

Li, J. et al. Reliable tumor detection by whole-genome methylation sequencing of cell-free DNA in cerebrospinal fluid of pediatric medulloblastoma. Sci. Adv. 6, eabb5427 (2020).

Liang, C. et al. Low-dose chemotherapy combined with delayed immunotherapy in the neoadjuvant treatment of non-small cell lung cancer and dynamic monitoring of the drug response in peripheral blood. elife 13, RP99720 (2024).

Acknowledgements

We sincerely appreciate the invaluable assistance provided by Nanjing Chest Hospital and the Shenzhen Engineering Center for Translational Medicine of Precision Cancer Immunodiagnosis and Therapy in data collection, data analysis, and other aspects of this study. This work was supported by the ‘Six one projects’ in Jiangsu Province (LGY2019006); Special Fund for the Construction of High level Hospitals in Jiangsu Province.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, H.L. and S.F.; Methodology, H.L. and S.L.; Writing, H.L.; Review and editing, H.L., N.Y., S.L., H.F., S.F., S.X., N.L., X.W., T.X., W.C., Y.L. and C.Y.; Funding acquisition, S.F.; Resources, H.F. and S.F.; Supervision, H.F., H.L., S.F.; All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Consent for publication

All authors have agreed to the publication of the manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fang, H., Luo, H., Li, S. et al. Serial monitoring of cerebrospinal fluid in patients with leptomeningeal metastases in lung cancer via the Ommaya reservoir as a predictive indicator of therapeutic efficacy and clinical prognosis. npj Precis. Onc. 10, 21 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41698-025-01218-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41698-025-01218-8