Abstract

Gene expression profiling in precision oncology is increasing with uncertain validity across platforms. In this study, we examined the application of PurIST, a molecular subtyping algorithm for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), across different platforms. We compared PurIST calls between matched samples processed by whole transcriptome and commercial exome capture RNA-seq. In parallel, we compared subtypes between matched samples processed by NanoString and whole transcriptome RNA-seq from the PANCREAS trial (NCT04683315). Between whole transcriptome and exome capture, subtype agreement was 81% with significant increase in basal-like subtype with exome capture. Differences in overall survival in patients with basal-like tumors compared to classical tumors did not reach statistical significance using exome capture (log-rank P = 0.061), whereas with whole transcriptome it was significantly shorter (log-rank P < 0.0001). Subtype agreement between whole transcriptome RNA-seq and NanoString was higher at 95%. PurIST results should be interpreted with caution when using exome capture methods.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The utilization of molecular oncology assays to assist with diagnosis, classification, prediction of prognosis, and selection of therapy has become ubiquitous in recent years, especially in conjunction with the development and approval of numerous targeted therapies and immunotherapies1,2. Traditionally, molecular assays have examined DNA to identify actionable molecular alterations such as single-nucleotide variants, insertions and deletions, copy number variants, and gene rearrangements. This information has also been used to match cancer patients to clinical trials with the goal of improving survival. More recently, there has been an expanded use of RNA-based assays to identify targetable variants, such as gene fusions and splice alterations, and to apply gene expression signatures to generate diagnostic, prognostic, and predictive information to guide the care of patients with cancer. In addition, there has been a rapid increase in commercially available tests with important implications in cross-platform reproducibility and validity.

One such commercial assay in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) is PurISTSM from Tempus AI, Inc. (Chicago, IL, USA), which offers clinical genomics services including DNA sequencing and transcriptome profiling using exome capture3,4. PurIST (Purity Independent Subtyping of Tumors) is a single-sample classifier (SSC) algorithm developed to predict the molecular subtypes of PDAC based upon the relative expression of 8 pairs of genes5 and is being evaluated in clinical trials using the NanoString nCounter® technology6. PurIST, which uses tumor-intrinsic genes that characterize basal-like and classical subtype PDAC, was developed through the training and validation of gene expression data from microarray and RNA-seq platforms5. We and others have consistently found that patients with basal-like subtype tumors have significantly shorter overall survival (OS)5,7,8,9,10,11,12,13. In addition, basal-like tumors are more resistant to systemic FOLFIRINOX (folinic acid, 5-fluorouracil, irinotecan, oxaliplatin) therapy but may respond better to gemcitabine with nab-paclitaxel (GnP), whereas classical tumors are sensitive to FOLFIRINOX5,10,11,12,14. Preclinical evidence also suggests that the basal-like state renders tumor cells more sensitive to RAS inhibitors15,16, lending importance to the PurIST subtypes in light of ongoing RAS inhibitor trials. More recently, our group reported that basal-like tumors are enriched in receptor tyrosine kinases such as epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and that patients with basal-like but not classical tumors respond to EGFR inhibition17. Based on these observations, prospective clinical trials are underway using PurIST subtypes as integral biomarkers in the neoadjuvant (PANCREAS trial, NCT04683315) and metastatic settings (PANGEA trial, NCT06483555) to select therapies based on molecular subtype.

After reporting the compatibility of PurIST classifier with their sequencing platform both with survival and response to FOLFIRINOX therapy using an internal database4, Tempus began offering PurISTSM for clinical use in May 2023. While integrating cancer classifiers with commercial clinicogenomics platforms is attractive in improving workflow by allowing clinicians to perform additional tests on samples that are already being sequenced, such tests should be analytically validated in a head-to-head comparison with a gold standard prior to being used for clinical decision-making. In fact, there have already been reports of inconsistent biomarker test results that may affect treatment allocation. Friends of Cancer Research Homologous Recombination Deficiency (HRD) Harmonization Project found discordant HRD calling in ovarian cancer between 17 assays that were tested (83% positive percent agreement, 80% negative percent agreement for clinical samples)18, which could impact the decision to treat with PARP inhibitors. Assays measuring tumor mutational burden (TMB) have also come under scrutiny for inconsistent results19, which is used to determine whether a patient should receive immunotherapy. Given that there is currently no data directly comparing cancer classifiers on different sequencing platforms, we sought to compare the performance of PurIST on the whole transcriptome RNA-seq that it was developed on versus exome capture RNA-seq in a commercial assay. In addition, we compared the results of whole transcriptome RNA-seq to the NanoString PurIST assay that is being used in two ongoing clinical trials.

Results

PurIST using exome capture RNA-seq overestimates basal-like subtype prevalence compared to whole transcriptome RNA-seq

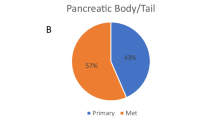

Seventy-nine patients had subtyping results available from whole transcriptome and exome capture RNA-seq (Fig. 1A). Using whole transcriptome, 7 tumors (8.9%) were basal-like and 72 (91.1%) were classical. Using exome capture, 22 tumors (27.8%) were basal-like and 57 (72.2%) were classical. All 15 non-concordant samples were predicted to be classical using whole transcriptome but were basal-like with exome capture. Overall accuracy of subtyping from exome capture using whole transcriptome RNA-seq as reference was 81.0% (64/79). This resulted in a Cohen’s kappa coefficient of 0.402 with 95% confidence interval (CI) between 0.130 and 0.675, indicating only moderate agreement20.

A Confusion matrix comparing classical and basal-like subtype prevalence by whole transcriptome and exome capture with Cohen’s kappa coefficient. B Paired boxplots of basal-like probabilities between whole transcriptome and exome capture. Points with connecting line represent the same sample. Line color is gray if there is no subtype switch and orange if there is a subtype switch between the two methods. One-tailed Wilcoxon Signed Rank test was used to determine whether there was a shift towards higher basal-like probability by exome capture RNA-seq. Small amount of random noise was added in x and y directions (maximum 0.05 in x direction and 0.02 in y direction) for visualization purposes only. C Scatter plot of basal-like probabilities between whole transcriptome and exome capture. D Plot of basal-like probability from whole transcriptome and probability discrepancy (basal-like probability using whole transcriptome minus basal-like probability using exome capture). Color of point outline is subtype by whole transcriptome and point fill is subtype by exome capture. EC-seq, exome capture RNA-seq; WT-seq, whole transcriptome RNA-seq.

As the pattern of non-concordance was significantly biased towards basal-like calling with exome capture (P = 9.08e-7, binomial test comparing basal-like proportions of exome capture to whole transcriptome RNA-seq), we leveraged the PurIST reporting of subtype as a continuous variable where the basal-like probability or the basal-ness of a sample can be evaluated5. Basal-like probabilities with exome capture were significantly higher than with whole transcriptome from the same samples (Paired Wilcoxon Signed Rank P = 1.491e-13, Fig. 1B), and overestimation of basal-like probabilities were more frequent at lower basal-like probabilities demonstrated by larger probability discrepancies (Fig. 1C, D). There was no significant correlation between inferred tumor purity and probability discrepancies (Pearson’s correlation r = −0.060 [95% CI, −0.277–0.163] for ESTIMATE and 0.144 [95% CI, −0.080–0.354] for DECODER; P = 0.600 for ESTIMATE and 0.206 for DECODER), indicating that the subtype mismatch was not due to low tumor purity (Fig. S1A, B). The range of inferred tumor purity by DECODER for non-concordant samples was between 39.4% and 56.4% (range 31.4–76.2% for all samples).

Exome capture RNA-seq leads to shifts in gene-pair expression ratios

We next examined why the exome capture method may have led to higher basal-like probabilities and higher prevalence of basal-like calls. PurIST relies on top scoring pair of genes (TSP) method, where ratios of eight gene pairs (one basal-like and one classical) are transformed into a basal-like probability. We found that the TSPs frequently switched from classical to basal-like with exome capture RNA-seq (Fig. 2A). The TSPs that were most frequently found to switch from classical to basal-like were KRT6A-ANXA10 (28/58 or 51% of cases; weight 1.031), BCAR-GATA6 (53/73 or 73% of cases; weight 0.618), and ITGA3-LGALS4 (46/60 or 77% of cases; weight = 0.059). Initially, we considered the possibility that exome capture might preferentially enhance detection of basal-like genes due to probe bias. However, when comparing the expression of PurIST genes between whole transcriptome and exome capture RNA-seq, we found that exome capture exhibited lower relative expression (see Methods) of 14 of 16 TSP genes spanning both classical and basal-like sets (Figs. 2B and S2), suggesting decreased global capture of PurIST genes. The three TSPs with frequent subtype switch from classical to basal-like demonstrated relatively similar ranked expression of the basal-like genes (KRT6A, BCAR3, ITGA3) between the two platforms but lower expression of the respective classical genes (ANXA10, GATA6, LGALS4).

A Sankey diagrams demonstrating whether each TSP is basal-like (gene A > gene B) or classical (gene A < gene B) in whole transcriptome (left bars) and exome capture (right bars). B Heatmap of gene expression by whole transcriptome (left) and exome capture (right) of the genes used in PurIST. Each column represents a sample, and columns are ordered by increasing basal-like probability from whole transcriptome RNA-seq. Genes (rows) are ordered by TSP weights. Gene expression was percentile rank normalized. EC-seq exome capture RNA-seq, TSP top scoring pairs of genes, WT-seq whole transcriptome RNA-seq.

PurIST subtypes from exome capture are less prognostic of overall survival compared to whole transcriptome

To examine whether the discordant subtype calls led to different clinical outcomes, we examined the OS of patients based on their tumor subtypes by both methods. Patients with basal-like subtype from whole transcriptome RNA-seq demonstrated significantly shorter median OS of 12 months (95% CI, 10–16 months) compared to 33 months (95% CI, 25–42 months) in patients with classical subtype (log-rank P < 0.0001) with increased mortality hazard ratio (HR) of 6.13 (95% CI, 2.52–14.9; Figs. 3A and S3A). With exome capture, patients who were classified as having basal-like tumors demonstrated numerically shorter median OS of 22 months (95% CI, 16–29 months) compared to 35 months (95% CI, 29–46 months) for those with classical tumors, but this did not reach statistical significance (log-rank P = 0.061, Fig. 3B). While HR for mortality was elevated with basal-like subtype (1.73, 95% CI, 0.98–3.08; Fig. S3A), this was also not statistically significant (P = 0.0604). Log likelihood value was higher with whole transcriptome than with exome capture (−212.75 versus −216.51, P < 2.2e-16), suggesting that subtypes from whole transcriptome RNA-seq can better explain OS than exome capture. Basal-like subtype was associated with shorter progression-free survival using both methods (whole transcriptome: 11 months [95% CI, 8–14 months] vs. 22 months [95% CI, 16–29 months] in classical, log-rank P = 0.00053; exome capture: 13 months [95% CI, 9–18 months] vs. 23 months [95% CI, 17–31 months] in classical; log-rank P = 0.034; Figs. 3C, D and S3B).

Higher concordance in subtypes with NanoString nCounter® platform

PurIST on NanoString platform in a CLIA-certified laboratory is currently being utilized for clinical trials. In this setting, the NanoString PurIST assay has been shown to be highly concordant with whole transcriptome RNA-seq results with 97% accuracy and calculated Cohen’s kappa coefficient of 0.819 (almost perfect agreement)6. Matched samples from the first 40 patients in the PANCREAS trial (NCT04683315) with NanoString PurIST results were processed using whole transcriptome RNA-seq. Of the 40 tumor samples, 4 were basal-like and 36 were classical using RNA-seq. On NanoString platform, 4 were basal-like and 36 were classical with one misclassification in each subtype category, resulting in overall accuracy of 95% (38/40) and Cohen’s kappa coefficient of 0.722 (95% CI, 0.347–1.097), indicating substantial agreement (Fig. 4A). There was no significant difference in paired basal-like probabilities between the two methods (Paired Wilcoxon Signed Rank P = 0.308; Fig. 4B). In addition, the switch between subtypes in the two discordant samples did not appear to be due to low tumor purity, as one of the samples had high proportion of malignant cells by pathology (approximately 50%) and most basal-like probabilities remained stable even at lower tumor purities (Fig. 4C). There was no significant correlation between percent malignancy and probability discrepancy (Pearson’s r = -0.066 [95% CI, −0.373–0.255], P = 0.692). The PANCREAS trial is still ongoing, and survival data are not yet available.

A Confusion matrix comparing classical and basal-like subtype prevalence by whole transcriptome RNA-seq and NanoString nCounter® assay with Cohen’s kappa coefficient. B Paired dot plots of basal-like probabilities between whole transcriptome RNA-seq and NanoString. Points with connecting line represent the same sample. Line color is gray if there is no subtype switch, orange if subtype switch is from classical to basal-like, and blue if subtype switch is from basal-like to classical. Red crossbars represent median basal-like probabilities. Two-tailed Wilcoxon Signed Rank test was used to determine whether there was a difference in basal-like probability between platforms. Small amount of random noise was added in x and y directions (maximum 0.05 in x direction and 0.025 in y direction) for visualization purposes only. C Plot of tumor purity and probability discrepancy (basal-like probability using whole transcriptome RNA-seq minus basal-like probability using NanoString). Color of point outline is subtype by RNA-seq and point fill is subtype by NanoString. WT-seq, whole transcriptome RNA-seq.

Discussion

The integration of laboratory developed tests (LDTs) to clinical practice provides unprecedented access to precision oncology with the potential to improve patient outcomes. However, these commercial tests often involve proprietary technologies and lack transparency that may be barriers to interlaboratory reproducibility. Inconsistent results in other measures that could determine the treatment allocation for cancer patients, such as HRD and TMB, have already been reported18,19. As PurIST was developed prior to the ubiquitous availability of many commercial assays, we sought to determine if PurIST is compatible with tests that are now offered commercially. We report head-to-head comparisons of matched samples between different platforms used to measure gene expression. We found that PurIST subtyping using a commercial exome capture method overestimates the basal-like probability and the prevalence of basal-like tumors relative to whole transcriptome RNA-seq. Given that PurIST was originally developed on microarray and whole transcriptome RNA-seq data, we hypothesize that the observed non-concordance may result from differential gene enrichment in exome capture, potentially due to varying capture efficiencies. Additional factors influencing exome capture efficiency may include gene length and GC content. This results in certain genes to be measured with artificially higher or lower baseline levels of expression relative to the other gene in a TSP and therefore biasing the overall subtype probability call. Lastly, differences in bioinformatic tools for transcript quantification may also contribute to the subtype discordance, as the commercial platform employs kallisto21 whereas our pipeline uses Salmon22. The overestimation of basal-like probability is clinically meaningful as patients with basal-like tumors from exome capture sequencing do not have significantly worse OS compared to those with classical tumors in this study.

Single cell RNA-seq, spatial transcriptomics, and multiplex immunofluorescence methods have demonstrated that PDAC tumors are heterogeneous, such that even when a bulk tumor is classified as one subtype, it may contain both classical and basal-like cells as well as co-expressor cells9,23,24,25. In addition, PDAC is characteristically stroma-rich, with neoplastic cells often comprising only a minority of the tumor volume26. These features may complicate reliable subtyping. To address this, PurIST was specifically designed using genes expressed in cancer cells to circumvent the need for experimental or bioinformatic tumor enrichment and has demonstrated consistency between surgical specimens and biopsies5. In addition, subtype calls are not affected by tissue processing5, and PurIST can be used on RNA from fresh frozen as well as FFPE samples, which is useful given that clinical samples are commonly stored as FFPE blocks. PurIST also computes a basal-like probability that likely represents the degree of tumor basal-ness, which has been shown to correlate with response to systemic therapies5,27. In our retrospective cohort, we did not observe an association between discordant subtype calls and imputed tumor purity, suggesting that the differential classification was not driven by low tumor purity. Similarly, in the trial population, basal-like probabilities remained stable between whole transcriptome RNA-seq and NanoString even at low tumor purities, further supporting the robustness of PurIST subtyping in low-cellularity samples.

PDAC molecular subtypes have been validated in multiple clinical studies to be prognostic and predictive of response to systemic therapies5,11,12,14. Therefore, it is critical to accurately classify tumors to match patients to appropriate therapies. Recently published final results from the COMPASS prospective trial and PASS-01 randomized phase II trial confirmed that basal-like tumors are more resistant to FOLFIRINOX28,29, validating the importance of molecular subtypes for treatment selection. PurIST was developed to be compatible across multiple platforms including whole transcriptome RNA-seq, microarrays, and NanoString assay with the goal of being translatable for clinical application, and its use on the NanoString platform has been tested against the gold standard whole transcriptome RNA-seq5,6. Discordant subtype calling on alternative platforms that have not been validated may have an impact on patient treatment decisions in the future. For example, 15/22 (68.2%) of patients predicted to have basal-like tumors would have mistakenly received GnP as part of the PANCREAS trial rather than the recommended FOLFIRINOX regimen11. In the setting of PANGEA trial, these patients would receive GnP plus erlotinib, a small molecule inhibitor of EGFR, which may be specifically effective against basal-like subtype but have no benefit for classical subtype tumors17.

Our study has several limitations. The sample size of our retrospective cohort is small with a low basal-like prevalence of 9%, which limits the reliability of statistical analyses of survival. Similarly, the small numbers preclude definitive conclusions regarding treatment response between subtypes, reflecting both the challenges of assembling a real-world cohort and the costs associated with running multiple transcriptomic assays for matched samples. Nevertheless, there is clear evidence of subtype shifts with exome capture that reduce observed survival differences between subtypes. The paired nature of our primary analysis, where we examine the difference between subtype calls within the same patient sample, also offers much greater power in detecting, characterizing, and generalizing differences between platforms from a statistical perspective, analogous to power gains typically seen from using paired designs for comparisons (i.e., paired t-tests) versus unpaired designs (i.e., unpaired two-sample t-tests). We also lack pathology-based estimates of malignant cell proportions in the retrospective cohort. To address this, we applied two independent bioinformatic pipelines for tumor purity estimation, demonstrating that differential subtype calls are not attributable to low cellularity. Finally, the PANCREAS trial is ongoing, and treatment outcomes as well as survival data based on NanoString subtypes are not yet available. Results from this trial will be critical for further validation of our findings as well as additional recommendations regarding how to incorporate molecular subtypes into clinical practice.

In summary, our results suggest that classifiers such as PurIST that are predicated on the comparison of expression between genes may generate different classifications depending on sequencing platforms, with misleading results impacting clinical decision making. For replicable and accurate application of classifiers dependent on gene expression comparisons, assays should be carefully evaluated between platforms prior to adoption. Given the widespread use of commercial sequencing assays in clinical practice, it may be necessary to identify alternative TSPs, retrain PurIST to improve concordance with whole transcriptome RNA-seq, and/or consider an alternative threshold of the basal-like probability that determines the subtype classification. Retrained models may need to be specific to each exome-capture platform, as there may be differences in probe biases and other sources of between-gene technical variations. Studies that apply multiple platforms to samples from the same patient may facilitate the identification of alternate gene pairs that are more consistent between modalities for retraining. Monitoring of the performance of retrained platform-specific models would be necessary to ensure that such classifiers remain relevant with future changes or updates to these platforms over time, adding another layer of complexity in their application. Based on our findings, we recommend that PurIST not be used on exome capture data for clinical decision making until cross-platform validation of a retrained model is completed. Our study highlights how technical differences between platforms can substantially alter subtype classification and its prognostic value, underscoring the need for rigorous clinical and analytical validation such as head-to-head cross-platform comparisons with matched samples before clinical adoption of any LDT.

Methods

Study design

Retrospective cohort

The retrospective cohort included PDAC patients treated at a single center. The study was approved by the institutional review board at Medical College of Wisconsin (Milwaukee, WI) and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients who had their tumors sequenced with Tempus xT/xR assay, which utilizes exome capture RNA-seq, were included. Whole transcriptome RNA-seq was performed from the same archival blocks except for one sample in which Tempus xT/xR assay was performed on a biopsy sample and RNA-seq was done on a surgical specimen with concordant subtype between platforms. Patient demographics, treatment information, and clinical outcomes were collected retrospectively with a cut-off date of September 2024.

Trial cohort

In an independent cohort from the PANCREAS trial (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT04683315), which was approved by the institutional review boards at both the Medical College of Wisconsin and HonorHealth Research Institute (Scottsdale, AZ) and also conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, the NanoString nCounter® assay was used in a Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA)-certified laboratory to measure PurIST gene transcripts and the remaining RNA samples were used in whole transcriptome RNA-seq. All patients provided informed consent prior to inclusion in the trial. NanoString assay directly quantifies RNA molecules and is the technology used for PAM50-based Prosigna® breast cancer classifier21,30.

Data acquisition and processing, PurIST subtyping

Raw sequencing data from Tempus xT/xR was obtained and processed as previously described22,23,31,32. NanoString assay was performed as previously described in a CLIA-certified laboratory at UNC Health6. Whole transcriptome RNA-seq was done as previously described5. Libraries from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tumors were prepared with KAPA RNA HyperPrep Kit with RiboErase (Roche) per manufacturer protocol. Libraries were sequenced on NextSeq 500 to obtain 60 million reads per sample. Tumor subtype was called using PurIST as described previously5. Normalized expression for Tempus xT/xR22,31 and RNA-seq5 or raw counts for NanoString were used. When comparing the relative expression of genes across platforms, the normalized expression values were adjusted using percentile ranking to ensure that the expression data were distributed on a constant scale.

Statistics

All analyses were performed in R (v4.4.2). Agreements between subtypes from different methods were examined using Cohen’s kappa (fmsb R package v0.7.6). Survival was analyzed using Kaplan–Meier estimator and Cox proportional hazards regression model (survival R package v3.7-0). Plots were generated with ggplot2 (v3.4.4), survminer (v0.4.9), and ggsankey (v0.0.99999) R packages. Heatmaps were generated with ComplexHeatmap (v2.20.0) R package. Tumor purity from RNA-seq data was inferred using ESTIMATE (Estimation of STromal and Immune cells in MAlignant Tumors using Expression data)24,33 using the tidyestimate (v1.1.1.9000) and DECODER25,27 using the decoderr (v0.0.0.9000) R packages.

Data availability

The sequencing data generated in this study have been deposited in the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) under accession number GSE313117.

Code availability

All custom codes used for analysis in this study are available at https://github.com/leejae-j/exome-capture-comparison.

References

Jorgensen, J. T. The current landscape of the FDA approved companion diagnostics. Transl. Oncol. 14, 101063 (2021).

The Pew Charitable Trusts. The Role of Lab-Developed Tests in the In Vitro Diagnostics Market. https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/reports/2021/10/the-role-of-lab-developed-tests-in-the-in-vitro-diagnostics-market (2021).

Beaubier, N. et al. Clinical validation of the tempus xT next-generation targeted oncology sequencing assay. Oncotarget 10, 2384–2396 (2019).

Wenric, S. et al. Real-world validation of the purity independent subtyping of tumors classifier for informing therapy selection in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. JCO Precis. Oncol. 9, e2500197 (2025).

Rashid, N. U. et al. Purity Independent Subtyping of Tumors (PurIST), a clinically robust, single-sample classifier for tumor subtyping in pancreatic cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 26, 82–92 (2020).

Li, Y. et al. Purity Independent Subtyping of Tumors (PurIST) Pancreatic Cancer Classifier: Analytic Validation of a 16-RNA Expression Signature Distinguishing Basal and Classical Subtypes. J. Mol. Diagn. 26, 962–970 (2024).

Moffitt, R. A. et al. Virtual microdissection identifies distinct tumor- and stroma-specific subtypes of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Nat. Genet. 47, 1168–1178 (2015).

Connor, A. A. et al. Integration of genomic and transcriptional features in pancreatic cancer reveals increased cell cycle progression in metastases. Cancer Cell 35, 267–282.e267 (2019).

Chan-Seng-Yue, M. et al. Transcription phenotypes of pancreatic cancer are driven by genomic events during tumor evolution. Nat. Genet. 52, 231–240 (2020).

Aung, K. L. et al. Genomics-driven precision medicine for advanced pancreatic cancer: early results from the COMPASS trial. Clin. Cancer Res. 24, 1344–1354 (2018).

O’Kane, G. M. et al. GATA6 expression distinguishes classical and basal-like subtypes in advanced pancreatic cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 26, 4901–4910 (2020).

Knox, J. J. et al. Early results of the PASS-01 trial: pancreatic adenocarcinoma signature stratification for treatment-01. J. Clin. Oncol. 42, LBA4004–LBA4004 (2024).

Singh, H. et al. Clinical and genomic features of classical and basal transcriptional subtypes in pancreatic cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 30, 4932–4942 (2024).

Nywening, T. M. et al. Targeting tumour-associated macrophages with CCR2 inhibition in combination with FOLFIRINOX in patients with borderline resectable and locally advanced pancreatic cancer: a single-centre, open-label, dose-finding, non-randomised, phase 1b trial. Lancet Oncol. 17, 651–662 (2016).

Dilly, J. et al. Mechanisms of resistance to oncogenic KRAS inhibition in pancreatic cancer. Cancer Discov. 14, 2135–2161 (2024).

Singhal, A. et al. A classical epithelial state drives acute resistance to kras inhibition in pancreatic cancer. Cancer Discov. 14, 2122–2134 (2024).

Xu, Y. et al. Tumor-intrinsic kinome landscape of pancreatic cancer reveals new therapeutic approaches. Cancer Discov. 15, 346–362 (2024).

Andrews, H. S. et al. Analysis of 20 independently performed assays to measure Homologous Recombination Deficiency (HRD) in ovarian cancer: findings from the friends’ HRD Harmonization Project. JCO Onco. Adv. 1, e2400042 (2024).

Furtado, L. V. et al. Recommendations for tumor mutational burden assay validation and reporting: a joint consensus recommendation of the Association for Molecular Pathology, College of American Pathologists, and Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer. J. Mol. Diagn. 26, 653–668 (2024).

Landis, J. R. & Koch, G. G. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 33, 159–174 (1977).

Bray, N. L., Pimentel, H., Melsted, P. & Pachter, L. Near-optimal probabilistic RNA-seq quantification. Nat. Biotechnol. 34, 525–527 (2016).

Patro, R., Duggal, G., Love, M. I., Irizarry, R. A. & Kingsford, C. Salmon provides fast and bias-aware quantification of transcript expression. Nat. Methods 14, 417–419 (2017).

Lee, J. J. et al. Elucidation of tumor-stromal heterogeneity and the ligand-receptor interactome by single-cell transcriptomics in real-world pancreatic cancer biopsies. Clin. Cancer Res. 27, 5912–5921 (2021).

Williams, H. L. et al. Spatially resolved single-cell assessment of pancreatic cancer expression subtypes reveals co-expressor phenotypes and extensive intratumoral heterogeneity. Cancer Res. 83, 441–455 (2023).

Pei, G. et al. Spatial mapping of transcriptomic plasticity in metastatic pancreatic cancer. Nature 642, 212–221 (2025).

Halbrook, C. J., Lyssiotis, C. A., Pasca di Magliano, M. & Maitra, A. Pancreatic cancer: advances and challenges. Cell 186, 1729–1754 (2023).

Peng, X. L., Moffitt, R. A., Torphy, R. J., Volmar, K. E. & Yeh, J. J. De novo compartment deconvolution and weight estimation of tumor samples using DECODER. Nat. Commun. 10, 4729 (2019).

Knox, J. J. et al. Whole genome and transcriptome profiling in advanced pancreatic cancer patients on the COMPASS trial. Nat. Commun. 16, 5919 (2025).

Knox, J. J. et al. PASS-01: randomized phase II trial of modified FOLFIRINOX versus gemcitabine/Nab-Paclitaxel and molecular correlatives for previously untreated metastatic pancreatic cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 43, 3355–3368 (2025).

Wallden, B. et al. Development and verification of the PAM50-based Prosigna breast cancer gene signature assay. BMC Med Genom. 8, 54 (2015).

Leibowitz, B. D. et al. Validation of genomic and transcriptomic models of homologous recombination deficiency in a real-world pan-cancer cohort. BMC Cancer 22, 587 (2022).

Michuda, J. et al. Validation of a transcriptome-based assay for classifying cancers of unknown primary origin. Mol. Diagn. Ther. 27, 499–511 (2023).

Yoshihara, K. et al. Inferring tumour purity and stromal and immune cell admixture from expression data. Nat. Commun. 4, 2612 (2013).

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the National Institutes of Health [R01 CA199064 to N.U.R. and J.J.Y.; U01 CA274298 to N.U.R., X.L.P., and J.J.Y.; P50 CA257911 to N.U.R., X.L.P., and J.J.Y.; and U24 CA211000 to X.L.P. and J.J.Y.]. NCT04683315 is funded by the Seena Magowitz Foundation. The funders played no role in study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of data, or the writing of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.J.L.: data acquisition, formal analysis, writing – initial draft, writing – review and editing. M.A.: data acquisition, formal analysis, writing—review and editing. A.B.M.: data acquisition, formal analysis, writing—review and editing. S.Z.T.: data acquisition, writing—review and editing. X.L.P.: data acquisition, formal analysis, writing—review and editing. Y.L.: data acquisition, writing—review and editing. M.L.G.: data acquisition, supervision, writing—review and editing. E.H.B.: data acquisition, supervision, writing—review and editing. S.T.: data acquisition, supervision, writing—review and editing. N.U.R.: conceptualization, formal analysis, supervision, project administration, writing—review and editing. J.J.Y.: conceptualization, formal analysis, supervision, project administration, writing—initial draft, writing—review and editing. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

PurIST was licensed to GeneCentric Therapeutics and subsequently licensed to Tempus AI. Neither GeneCentric nor Tempus was involved in the design of this study. J.J.Y. and N.U.R. are patent holders of PurIST (WO2020205993A1). E.H.B. has consulting or advisory roles at NanOlogy, BPGbio, ClearNote Health, Merus, VCN Biosciences, Corcept Therapeutics, and Arcus Biosciences, and HonorHealth Research Institute receives research funding from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Pharmacyclics, Idera, Daiichi Sankyo, Minneamrita Therapeutics, Lilly, Merck, Helix, BioNTech AG, Corcept Therapeutics, and Biosplice. Remaining authors declare no financial or non-financial competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, J.J., Aldakkak, M., Morrison, A.B. et al. Cross-platform comparison of gene expression-based cancer molecular subtyping reveals discrepancies with exome capture methods. npj Precis. Onc. 10, 37 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41698-025-01228-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41698-025-01228-6